1. Introduction

Child-to-parent violence (CPV) is defined as any physical, psychological, or economic violence repeatedly used by adolescents against their parents (or those acting as such) [1–3]. In recent years, the number of recorded cases of CPV in developed countries has risen exponentially, generating major social concern. The prevalence of CPV in Spain shows differentiated data depending on the type of violence. The rate ranges from 4.6% to 22% in the case of physical violence, between 45% and 95% in verbal violence [4–6]. In Canada and the United States, the CPV rate stands at 12% and 34% for physical violence, respectively, and 60% and 64% for psychological violence [7,8]. These figures reflect a growing socio-educational problem and in recent years, it has led a wide range of professionals –across legal, educational, health, psychotherapeutic, etc. disciplines– to study the causes of CPV, the main factors involved, and the possible means of prevention and intervention in families.

In the field of psychosocial research, several authors have lately focused on the factors involved in the genesis and development of CPV [9–11]. In the present study, we chose to approach CPV based on the ecological model of Bronfenbrenner (1994). This latter paradigm suggests analysing psychosocial variables according to an adolescent’s various socialisation contexts [13]. In schools, previous studies have found a relationship between CPV and problems of adaptation and school performance [14] , absenteeism, learning difficulties, and school violence [15,16].

In the family context, several studies have observed that parental socialisation styles are related to CPV. Among these styles, the authoritarian style is the style that is the most strongly associated with greater psychosocial adjustment problems in adolescents, and specifically with CPV [2]. A relevant factor in the family sphere is communication between parents and children, which is regarded as an indicator of family climate quality (Hereyah & Purwanti, 2021; Jiménez, Murgui, & Musitu, 2007) . When family communication is positive, cohesion in the family is strengthened because it fosters empathy, active listening, and support for children [18]. Conversely, offensive family communication, characterised by disrespect and offensive language reflects negative family functioning that is harmful to adolescents’ psychosocial development [19].. Recent works have highlighted the direct relationship between offensive family communication and CPV(Jiménez et al., 2019; López-Martínez et al., 2019). However, there is scarce research on other relevant individual psychosocial variables that are assumed to be involved in this relationship -such as those examined in this work.

At the individual level, several authors have observed that certain personal risk factors directly affect CPV such as low self-concept, narcissism, low empathy, and loneliness [22,23]. A factor that we consider relevant here and is today among the most widespread disorders in adolescent and young populations is psychological distress. The psychological distress construct encompasses depressive symptomatology, stress, and generalised anxiety disorder [24,25]. . Several authors have indicated that family communication problems are associated with psychological distress in children [26,27]. Moreover, other studies have equally observed that adolescents suffering from psychological distress are more likely to manifest violent behaviours towards their peers, e.g., violence towards their partners and cyberbullying [28,29]. In the case of CPV, Ibabe & Jaureguizar (2011) found that children who assault their parents present high anxiety levels and, in a subsequent work, they encountered a significant relationship between CPV and depressive symptoms (Ibabe et al. 2014). One possible explanation for the relationship between CPV and psychological distress is the fact that emotional and mental health problems are a risk factor in the development of problematic externalising behaviours such as violence (Morelli et al., 2016; Romero-Abrio et al., 2019).

Another major individual variable recently analysed in recent work on adolescent peer violence is attitude towards institutional authority. The latter is divided into two dimensions: positive attitude towards institutional authority; and positive attitude towards social norm transgression [32]. The factors of family relationship quality and family communication are associated with attitude towards authority in adolescence [19,33]. More specifically, several studies have observed that problematic communication between parents and children enhances the development of adolescents’ transgressive attitude towards rules [31,34]. Moreover, studies on the role of transgressive behaviour in violent, disruptive, and criminal behaviours in adolescence have produced significant results [35,36]. Studies on CPV have also identified positive attitudes towards social norm transgression in adolescents as a CPV risk [37,38]. A further subject of interest in this study was to understand whether any gender differences existed in the relationships between the variables analysed. Previous studies on CPV have found that girls use verbal violence towards their parents more frequently than boys, who, for their part, resort more frequently to physical violence [37]. Differences in family communication have also been observed in other studies, girls showing higher scores on offensive communication with their mothers than boys (Buelga, Martínez-Ferrer, & Musitu, 2015; Sofía Buelga et al., 2017). In addition, according to several studies, adolescent girls suffer more psychological distress than boys, which could be explained by girls’ greater emotional complexity in the face of relational problems [42–46]. However, boys have scored higher on positive attitude towards social norm transgression, and girls show a greater positive attitude towards institutional authority [34,47,48].

1.1. The current study

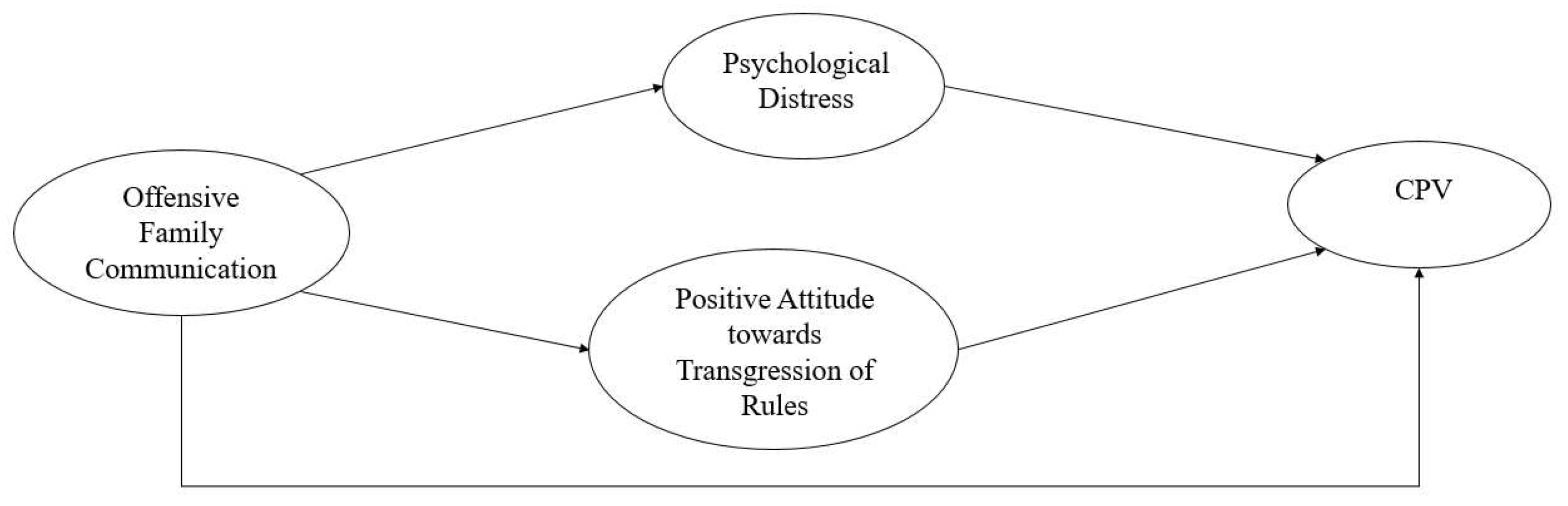

Previous work has analysed the relationship of offensive family communication with other forms of violence in adolescence [20,39,49]. In a recent study by Romero-Abrio et al. [50] it was observed that offensive family communication is associated with cyberbulllying, and that, in addition, there is also an indirect relationship between both factors moderated by psychological distress and positive attitude towards transgression of rules. The interest of the present study lies in examining how offensive family communication affects CPV, which differs from cyberbullying in that it is not a type of violence between peers but rather from children towards parents. We consider of interest to know the influence of the family environment in the genesis and development of the different manifestations of violent behavior in adolescence. Therefore, the study objective was to analyse the relationship between family communication problems and CPV in adolescence, as well as the moderating role of psychological distress and positive attitude towards social norm transgression in this relationship. The hypotheses were as follow (

Figure 1): (1) Offensive family communication is directly and significantly related to CPV; (2) Offensive family communication is indirectly related to CPV, via psychological distress and positive attitude towards transgression of rules; and (3), These relationships present variations according to gender.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 7787 adolescents (51.5% boys and 48.5% girls) between 12 and 16 years of age (M= 13.37 and SD= 1.34) enrolled in secondary schools in the State of Nuevo León (Mexico), distributed in different age groups: 53.9% between 12 and 13 years of age, and 46.1% between 14 and 16 years of age. Participants were selected by proportional stratified sampling, and geographic area was used as sampling units, resulting in 62.5% of adolescents from urban schools and 37.5% from rural schools. Missing scale or subscale data were treated using the multiple linear imputation model [51], always below 15%. Standardised scores were explored to identify univariate outliers [52,53].

2.2. Mesures

Conflic Tactics Scale [54]. In this study we used the adaptation made by [55], which consists of two subscales, one of violence towards the father and the other of violence towards the mother. Each contains six items referring to physical violence (e.g., "I hit, punched, or slapped my parents") and verbal violence (e.g., "I insult or have insulted or sworn at my parents"). Items numbers 8 and 9 referring to economic violence were excluded in this study. Each item has seven response options (from 0 = never to 7 = more than twenty times). The psychometric properties of the scale showed a good fit to the data: SBχ2 = 11.1246, gl = 7, p = .13328, CFI = 0.956, RMSEA = 0.017 (90% CI [0.000, 0.036]), NNFI = 0.912. The factor loadings varied. Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale was .71. For the subscale of violence toward the mother it was .73, and .77 (physical violence) and .72 (verbal violence) and for the subscale of violence toward the father it was .76, and .89 (physical violence) and .73 (verbal violence).

Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale [56], later adapted by (Jiménez et al., 2009, 2019) was used. In the present study we chose to use only the offensive communication subscale (e.g. "My father/mother tries to offend me when he/she gets angry with me"). In turn, this is divided into communication mother-adolescent, and communication father-adolescent. The subscale consists of ten items with five response options (0 = never, 5 = always). The subscale showed a good fit to the data (mother (SB χ2 = 2594.5748, gl = 128, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.953, RMSEA = 0.049 (0.047, 0.051)); father (SB χ2 = 2885.3985, gl = 120, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.947, RMSEA = 0.053 (0.052, 0.055)). Cronbach's alpha was 0.77 (father) and 0.73 (mother).

Psychological Distress Scale K10 [58]. The scale consists of ten items (e.g., “How often did you feel restless or fidgety”) and offers an overall score of psychological distress, with five response options (none of the time, a little of the time, some of the time, most of the time, and all of the time). The scale has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties: (SBχ2 = 504.7299, gl = 29, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.981, RMSEA = 0.045 (0.042, 0.049)). Factor loadings ranged between 0.68 and 0.74.

Attitudes towards institutional authority in adolescents Scale (AAI-A) [47]. In the present study we opted for the subscale of positive attitude towards the transgression of rules (e.g., “It doesn't matter if you break school rules if there are no punishments afterwards”), which consists of four items with four response options (1 = totally disagree, 4 = totally agree). The scale showed a good fit to the data in the confirmatory scale analysis (CFA) (SB χ2 = 317.9209, gl = 23, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.976, RMSEA = 0.040 (0.036, 0.044)). Cronbach's alpha was .75.

2.3. Procedure

The research was carried out within the framework of a collaboration between the Universidad Pablo de Olavide (Spain) and the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (Mexico). Once the appropriate permissions had been obtained, the research staff went to the centers to administer the instruments, offering support to the students who needed it, and adequately informing them of the voluntary nature of the study, as well as the guarantee of anonymity. The study complied with the ethical values required in human research [59].

2.4. Data analysis

Firstly, the Pearson correlations were calculated between all the variables studied and the t-test was performed. Then, an EQS 6.1 structural equations model [60] was calculated to analyse the relationship between the latent factors. Robust estimators were used to calculate the goodness-of-fit of the model and the statistical significance of the coefficients. IFC, IFI, and NNFI indices with values equal to or greater than 0.95 were considered acceptable, and for the RMSEA index values equal to or less than 0.08. Once the model had been calculated with the general sample of adolescents, a multi-group analysis was carried out to examine the differences in the relationships obtained according to the sex of the adolescents. Two groups were established according to the sex of the subjects: boys (N = 4102) and girls (N = 3375). Two models were calculated for the group of boys and girls, respectively. In the calculation of the first model (restricted model), all relationships between the variables had to be equivalent. By contrast, the second model (non-restricted model) was calculated without restrictions in the estimated parameters; hence, the relationships between the variables could differ in the different groups. Subsequently, the chi-square coefficient of the restricted and unrestricted models was compared; if this coefficient was significantly greater in the restricted model, invariance between the groups could be assumed.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Pearsons Correlation

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, correlations between the variables studied. The correlation analysis showed significant relationships between the variables studied.

3.2. Direct and indirect effects

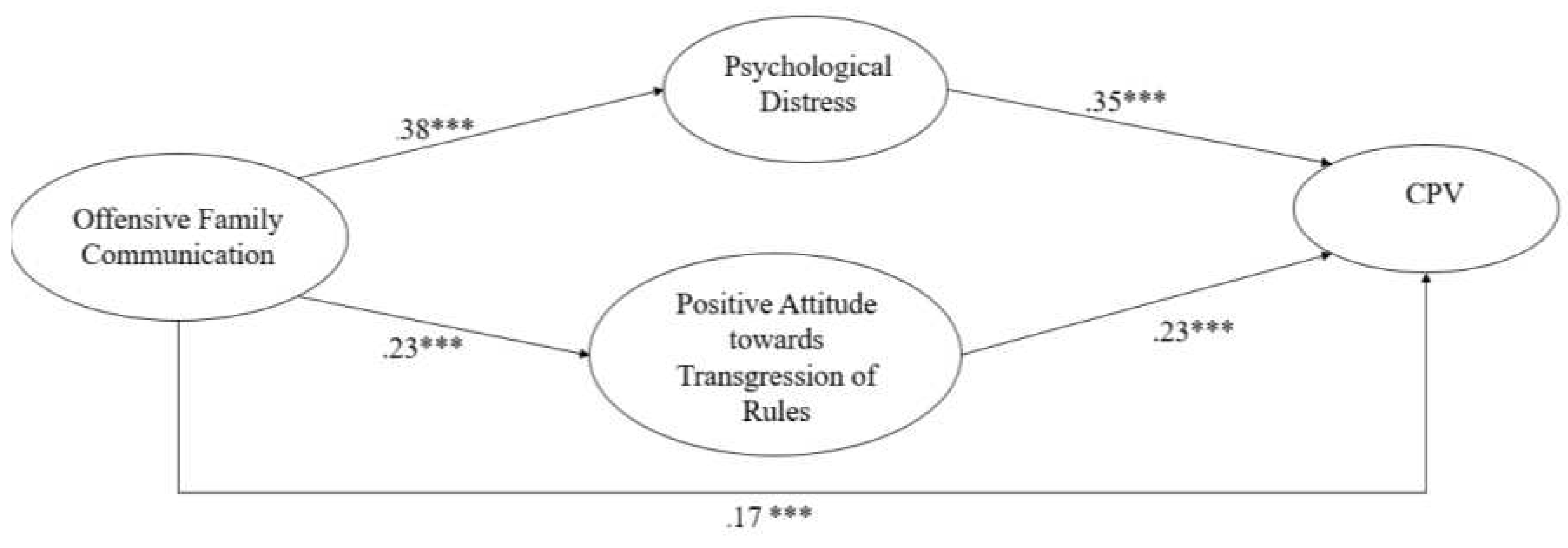

A structural equations model was then calculated with the EQS 6.0 program [53] (

Table 2) shows the latent variables included in the model, their respective indicators, the standard error, and the associated probability for each indicator in the corresponding latent variable. Regarding the calculated equation model, the maximum likelihood method was used, with robust estimators (Mardia coefficient = 154.5272; Normalized estimator = 394.5511). The model showed an adequate fit to the data [S-B χ

2 = 370.3650; gl = 39, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.034 (0.031, 0.037)] and explained 28% of the variance of the CPV. As shown in

Figure 2, the results indicated that family communication problems were directly and positively related to CPV (β = .07, p < .001), to psychological distress (β = .38, p < .001) and to positive attitude toward transgression of rules (β = .23, p < .001). On the other hand, psychological distress was directly and positively related to CPV (β = .35, p < .001). Similarly, positive attitude toward transgression of rules was directly and positively related to CPV (β = .23, p < .001).

Regarding indirect effects (see

Table 3), it was observed that family communication problems were related to CPV through psychological distress (β =.131, CI [.113 - .150], p < .001). Similarly, family communication problems were related to CPV through positive attitude toward transgression of rules (β =.052, CI [.041 - .063], p < .001).

3.3. Moderating effect of gender

In order to examine the existence of significant differences in the paths obtained, a multigroup analysis was performed. First, two groups were created according to the sex of the individuals: boys (N = 4012) and girls (N = 3775). Next, two models were calculated, in which the first one imposes restrictions so that all the relationships between variables are the same; whereas, in the second model no restrictions are imposed, so that differences in the relationships between variables can be found in boys and girls. Finally, the Chi-Square coefficient of both models was contrasted to see if invariance between the groups can be assumed. The results show significant differences in the model between adolescent boys and girls (Δχ2 (16,N = 7787) = 222.58; p < .001). After examining the restricted model, it was decided to release 8 restrictions that decreased the χ2 coefficient. Five restrictions refer to differences in the errors of the variables that make up the model, meaning that there is no substantial change in the relationships obtained in the general model. The other three relate to the relationship between the observable factors. It was found that the relationship between family communication problems and psychological distress is significant in the group of boys (b = .254; p < .001), but greater in the group of girls (b = .533; p < . 001), while the relationships between family communication problems and child-parent violence and between family communication problems and positive attitudes toward violating rules are significant and greater for girls (b = .245, p < .001; b = .276, p < .001) than for boys (b = .100, p < .001; b = .222, p < .001). When the restrictions were removed, both models were shown to be equivalent for boys and girls (Δχ2 (8,N = 7787) = 13.38; p > .05).

4. Discussion

The study objective was to analyse the relationship between family communication problems and CPV, as well as the moderating role of psychological distress and positive attitude regarding social norm transgression in this relationship.

First, was a direct and significant relationship was found between offensivefamily communication and CPV, confirming the first hypothesis. These data are consistent with those found in previous studies and emphasize, once again, the key role of positive family communication as a protective factor against violent behaviour in adolescents (Jiménez et al., 2019; López-Martínez et al., 2019). In addition, in the multigroup analysis, girls obtained higher scores on this relationship than boys, thus also partially confirming the third hypothesis. This result supports that of other studies in which this difference was specifically highlighted to be more widespread in mother-daughter communication. In addition, girls use more verbal violence against their mothers than physical violence (Buelga et al., 2015, Martinez-Ferrer et al., 2018). In this sense, our results provide empirical evidence of the fact that the mother-child relationship is a very significant factor in the regulation of violent child behaviour, especially that of daughters, and in particular in the case of CPV. Adolescent girls engage in more verbal CPV towards their mothers than boys. The most likely explanation is that it consists of a response to the negative family climate in which they are immersed and in which they constantly perceive a lack of empathy and support from their parents [61]. They also find their mother figure to be a permanent source of conflict. This line of research should be explored more deeply in future works, delving into specific communication problems with mothers.

Second, an indirect relationship was observed between offensive family communication and CPV through its relationships with psychological distress. This result partially confirms the second hypothesis and provides empirical evidence of the fact that, as observed in recent studies, offensive child-parent communication directly affects child psychological distress (Clements-Nolle & Waddington, 2019; Romero-Abrio et al., 2019). Perceptions of lack of parental support as well as offensive and disrespectful language towards children fosters negative feelings and emotions in adolescents. The latter then increases the possibility of anxiety and depressive symptoms. This psychological discomfort generated by family communication problems enhances, in turn, the appearance of CPV. The reason is probably a reaction against the hostile family climate and the need to achieve some degree of peace and harmony through behaviours such as verbal or physical force to reduce their levels of discomfort [63–65]. In addition, as hypothesised, results showed that girls obtained higher scores on the relationship between offensive family communication and psychological distress than boys. This finding is of great interest and consistent with that of recent studies according to which girls suffer more anxiety and show more depressive symptoms during adolescence [28,65]. We can infer from our results that adolescent girls are more sensitive to the negative family climate and suffer more psychological problems than boys, probably because they also perceive and experience poor parental support as well as family relational and communication problems more intensely. The gender differences observed for these variables are highly relevant today and call for a more thorough analysis in future studies.

Finally, an indirect relationship was found between offensive family communication and CPV through positive attitude towards social norm transgression, confirming the second hypothesis. These results are compatible with that of previous studies according to which family communication problems are associated with children’s attitude towards institutional authority [19,66]. In families where family functioning is negative and parent-child communication is thus offensive and disrespectful, adolescents tend to transgress rules imposed both inside and outside the home [38]. Thus, children manifest their response to negative family functioning by adopting a defiant attitude towards their parents when they feel poorly understood and receive little affection [33,34,67]. This positive attitude towards norm transgression imposed on the family is, in turn, a risk factor for CPV, as reflected in the results of our study, confirming recent observations by various researchers [37,38]. Our work shows that adolescents are more likely to use violence against their parents when they adopt transgressive behaviours towards social and family norms as a reaction to the deficiencies, especially of a communicative nature, that they perceive in their family functioning. One possible explanation is that children who are raised in hostile homes feel the need to defy established norms and figures of authority – in this case, their parents – and to engage in a visible power struggle with their parents (Mazzone & Camodeca, 2019; Nuñez-Fadda et al., 2020). In this situation, they use violence to measure their strength, lacking other more adaptive psychological and behavioural mechanisms that allow them to face family difficulties in a functional way. The multigroup analysis led to another significant result regarding gender: girls obtained higher scores than boys on the relationship between family communication problems and positive attitude towards social norm transgression. We believe that this result is novel since it contrasts with the findings of other studies according to which adolescent boys are more likely to show positive attitudes towards social norm transgression than girls, who usually show a more positive attitude towards institutional authority (Jiménez et al., 2014; Ortega-Baron et al., 2017). Again, we observed that during their adolescence, girls are more sensitive to communication problems with their parents than boys and have few emotional resources to cope with a negative family climate. They adopt transgressive and rebellious behaviours towards their parents more often than boys do when they feel humiliated and disrespected by them, probably to minimise the negative feelings generated by the situation [45]. We consider it of great interest to pursue this subject in future studies.

Lastly, this study presented some limitations. On the one hand, its cross-sectional design did not allow establishing causal relationships between variables, so it would be relevant to expand the study with longitudinal research. On the other, the study is based solely on self-reported data: it did not consider any information of interest that could have been provided by parents and other significant agents of teenager socialisation, such as peers or teachers. Broader sources of information should be incorporated in future studies on CPV to pursue the same line of analysis and reflection.

5. Conclusions

From a psychosocial perspective, child-to-parent violence is a complex subject to study. Many social, family, and individual factors are involved in the genesis and development of child-to-parent violence. This type of violence takes place within the family sphere and many parent narratives contain biases or conceal information, making it therefore difficult to collect objective data. In addition, novel forms of child-to-parent violence are emerging today in our changing society, such as the use of technological means to exercise violence (child-to-parent cyberviolence) [6]. We are also witnessing new family models (single-parent, reconstituted or homoparental families, etc.) which are essential to study to better understand CPV. In short, we must pursue our study of child-to-parent violence in order to generate new approaches and to further our understanding of the phenomenon. As in the case of the present work, such studies could provide keys to improving psychoeducational interventions with families and adolescents and, naturally, their health and well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and G.M.; methodology, G.M., A.R. and J.C.S.; formal analysis, J.E.C. and G.M.; investigation, A.R. and G.M..; resources, J.C.S.; data curation, J.E.C. and G.M..; writing—original draft preparation, A.R. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, A.R., J.C.S. and G.M.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, G.M.; project administration, G.M.; funding acquisition, G.M. and J.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Pablo de Olavide University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all adolescents involved in the study and their parents.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available under request.

Acknowledgments

This research has been made in collaboration with the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon (México) in the framework of the collaboration RIEVA (Iberoamerican Network for the Study of Violence in Adolescence).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pereira, R.; Loinaz Calvo, I.; Bilbao, H.; Arrospide, J.; Bertino, L.; Calvo, A.; Gutiérrez, M.M. Propuesta de definición de violencia filio-parental: Consenso de la Sociedad Española para el estudio de la Violencia filio-parental (SEVIFIP). Papeles del Psicólogo - Psychol. Pap. 2017, 38, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Relinque, C.; Arroyo, G. del M.; León-Moreno, C.; Jerónimo, J.E.C. Child-to-parent violence: which parenting style is more protective? A study with spanish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, B. Parent abuse: The abuse of parents by their teenage children. Natl. Clear. Fam. Violence 2003, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Rivera, S.; García, V.H. Theoretical framework and explanatory factors for child-to-parent violence. A scoping review. An. Psicol. 2020, 36, 220–231. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, L.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J.; Cano-Lozano, M.C. Prevalence and reasons for child-to-parent violence in Spanish adolescents: gender differences in victims and aggressors. Colección Psicol. y Ley 2020, 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez Relinque, C.; Moral-Arroyo, G. del Child-to-parent cyber violence: what is the next step? J. Fam. violence, 2023, 38, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.; Bell, T.; Fréchette, S.; Romano, E. Child-to-Parent Violence: Frequency and Family Correlates. J. Fam. Violence 2015, 30, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, R.; Novoa, M.; Fariña, F.; Arcea, R. Child-to-parent Violence and Parent-to-child Violence: A Meta-analytic Review. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. to Leg. Context 2019, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Fernández-González, L.; Chang, R.; Little, T.D. Longitudinal Trajectories of Child-to-Parent Violence through Adolescence. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 35, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, I. Adolescent-to-parent violence and family environment: The perceptions of same reality? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, E.; Rosado, J.; Cantón-Cortés, D. Impulsiveness and Child-to-Parent Violence: The Role of Aggressor’s Sex. Span. J. Psychol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Edducation; 1994. ISBN 0716728605.

- Sanchez-Meca, J.; Botella, J.; Vázquez, C.; Nieto, M.; Chunga, L.S.; Luengo Rodríguez, T.; Román Sánchez, J.M.; Sanchez, J.R.; Anton, L.M.; Carbonero, M.-. ángel; et al. Una Comprensión Ecológica de la Violencia Filio-Parental. An. Psicol. 2016, 31, 397. [Google Scholar]

- Ibabe, I. Predictores familiares de la violencia filio-parental: El papel de la disciplina familiar. An. Psicol. 2015, 31, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Arroyo, G.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Suárez-Relinque, C.; Ávila-Guerrero, M.E.; Vera-Jiménez, J.A. Teorías sobre el inicio de la violencia filio-parental desde la perspectiva parental: un estudio exploratorio. Pensam. psicológico 2015, 13, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erostarbe, I.I. Perfil de los hijos adolescentes que agreden a sus padres. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, T.; Murgui, S.; Musitu, G. Comunicación familiar y ánimo depresivo: el papel mediador de los recursos psicosociales del adolescente. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2007, 24, 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.H. Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Sytems. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Castañeda, R.; Núñez-Fadda, S.M.; Musitu, G.; Callejas-Jerónimo, J.E. Comunicación con los padres, malestar psicológico y actitud hacia la autoridad en adolescentes mexicanos: su influencia en la victimización escolar. Estud. Sobre Educ. 2019, 36, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, T.I.; Estévez, E.; Velilla, C.M.; Martín-Albo, J.; Martínez, M.L. Family Communication and Verbal Child-to-Parent Violence among Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. public Heal. 2019, 16, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, P.; Montero-Montero, D.; Moreno-Ruiz, D.; Martínez-Ferrer, B. The Role of Parental Communication and Emotional Intelligence in Child-to-Parent Violence. Behav. Sci. (Basel). 2019, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, H.; Martín, A.M. The behavioral specificity of child-to-parent violence. An. Psicol. 2020, 36, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, M.; Morán Rodríguez, N.; García-Vera, M.P. Violencia de hijos a padres: Revisión teórica de las variables clínicas descriptoras de los menores agresores. Psicopatología Clin. Leg. y Forense 2011, 11, 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, C.M.; Caporino, N.E.; Kendall, P.C. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychol. Bull. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020. [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.; Allen, J. Family Communication Patterns, Self-Esteem, and Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Direct Personalization of Conflict. Commun. Reports 2017, 30, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrodt, P.; Ledbetter, A.M. Communication processes that mediate family communication patterns and mental well-being: A mean and covariance structures analysis of young adults from divorced and nondivorced families. Hum. Commun. Res. 2007, 33, 330–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Hébert, M.; Blais, M.; Lavoie, F.; Guerrier, M.; Derivois, D. Cyberbullying, psychological distress and self-esteem among youth in Quebec schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 169, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, M.; Bianchi, D.; Baiocco, R.; Pezzuti, L.; Chirumbolo, A. Sexting, psychological distress and dating violence among adolescents and young adults. Psicothema 2016, 28, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibabe, I.; Arnoso, A.; Elgorriaga, E. Behavioral problems and depressive symptomatology as predictors of child-to-parent violence. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. to Leg. Context 2014, 6, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Abrio, A.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Sánchez-Sosa, J.C.; Musitu, G. A psychosocial analysis of relational aggression in Mexican adolescents based on sex and age. Psicothema 2019, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Emler, N.; Reicher, S. Adolescence and delinquency: The collective management of reputation; 1995; Vol. xiv. ISBN 978-0-631-13802-0 978-0-631-16823-2.

- Estévez, E.; Murgui, S.; Moreno, D.; Musitu, G. Estilos de comunicación familiar, actitud hacia la autoridad institucional y conducta violenta del adolescente en la escuela [Family communication styles, attitude towards institutional authority and violent behavior of adolescents in school]. Psicothema 2007, 19, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Carrascosa, L.; Cava, M.J.; Buelga, S. Actitudes hacia la autoridad y violencia entre adolescentes: diferencias en función del sexo [Attitudes towards authority and violence among adolescents: differences according to sex]. Suma Psicológica 2015, 22, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emler, N.; Reicher, S. Delinquency: Cause or consequence of social exclusion. In The social psychology of inclusion and exclusion; 2005; pp. 211–241. ISBN 0203496175.

- Ortega-Barón, J.; Buelga, S.; Caballero, M.J.C.; Torralba, E. School violence and attitude toward authority of student perpetrators of cyberbullying. Rev. Psicodidact. 2017, 22, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Romero-Abrio, A.; Moreno-Ruiz, D.; Musitu, G. Child-to-parent violence and parenting styles: Its relations to problematic use of social networking sites, alexithymia, and attitude towards institutional authority in adolescence. Psychosoc. Interv. 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral, G.; Suárez-Relinque, C.; Callejas, J.E.; Musitu, G. Child-to-parent violence: attitude towards authority, social reputation and school climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.J.; Buelga, S.; Musitu, G. Parental communication and life satisfaction in adolescence. Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buelga, S.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Musitu, G. Family relationships and cyberbullying. In Cyberbullying Across the Globe: Gender, Family, and Mental Health; 2015; pp. 99–114. ISBN 9783319255521.

- Buelga, S.; Martínez–Ferrer, B.; Cava, M.J. Differences in family climate and family communication among cyberbullies, cybervictims, and cyber bully–victims in adolescents. Comput. Human Behav. 2017, 76, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M. A comparative analysis of empathy in childhood and adolescence: Gender differences and associated socio-emotional variables. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2009, 9, 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, G.; Kerslake, J. Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Comput. Human Behav. 2015, 48, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Martinez-Valderrey, V.; Aliri, J. Autoestima, empatía y conducta agresiva en adolescentes víctimas de bullying presencial. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2013, 3, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ferrer, B.; Romero-Abrio, A.; Moreno-Ruiz, D.; Musitu, G. Child-to-parent violence and parenting styles: its relationships with the problematic use of virtual social networks, alexithymia and the attitude towards institutional authority in adolescence. Psychosoc. Interv. 2018, 27, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, R.F.; Hall, R.J.; Williams, C.M.; Hasan, N.T. Gender Differences in Alexithymia. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2009, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.J.; Estévez, E.; Buelga, S.; Musitu, G. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de actitudes hacia la autoridad institucional en adolescentes (AAI-A). An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L. Ecological Theory: Preventing Youth Bullying, Aggression, and Victimization. Theory Pract. 2014, 53, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.E.; Olaizola, J.H.; Ferrer, B.M.; Ochoa, G.M. Aggressive and non-aggressive rejected students: An analysis of their differences. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Abrio, A.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Musitu-Ferrer, D.; León-Moreno, C.; Villarreal-González, M.E.; Callejas-Jerónimo, J.E. Family communication problems, psychosocial adjustment and cyberbullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; 2017; pp. 1–40. ISBN 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128.

- Batista-Foguet, J.M.; Coenders, G. Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales: Modelos para el análisis de relaciones causales; 2000.

- Bentler, P.M. EQS 6 structural equations program manual; 2006. ISBN 1885898037.

- Straus, M.A.; Douglas, E.M. A Short Form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and Typologies for Severity and Mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004, 19, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J.; Orue, I.; Gámez-Guadixb, M.; Calvete, E. Multivariate models of child-to-mother violence and child-to-father violence among adolescents. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. to Leg. Context 2020, 12, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.; Olson, D. Parent adolescent communication scale. In Family Inventories; D.H. Olson, Ed.; SSt. Paul: Family Social Sciences, University of Minnesota, 1982; pp. 145–182. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, T.I.; Musitu, G.; Ramos, M.J.; Murgui, S. Community involvement and victimization at school: an analysis through family, personal and social adjustment. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 37, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.; Mroczek, D. Final version of our non-specific psychological distress scale.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013.

- Hair, J.F.J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Structural Equation Modeling Basics. In Multivariate Data Analysis; 2009; pp. 1–35.

- Buelga, S.; Iranzo, B.; Postigo, J.; Carrascosa, L.; Ortega Barón, J. Parental Communication and Feelings of Affiliation in Adolescent Aggressors and Victims of Cyberbullying. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Nolle, K.; Waddington, R. Adverse childhood experiences and psychological distress in juvenile offenders: The protective influence of resilience and youth assets. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2019, 64, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P. Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2013, 53, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranzo, B.; Buelga, S.; Cava, M.J.; Ortega-Barón, J. Cyberbullying, psychosocial adjustment, and suicidal ideation in adolescence. Psychosoc. Interv. 2019, 25, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B.; Keppens, G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: Results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Baron, J.; Buelga, S.; Cava, M.-J.; Torralba, E. School Violence and Attitude Toward Authority of Students Perpetrators of Cyberbullying. Rev. Psicodidact. (English ed.) 2017, 22, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Musitu, G.; Estévez, E.; Emler, N. Adjustment problems in the family and school contexts, attitude towards authority, and violent behavior at school in adolescence. Adolescence 2007, 42, 779–794. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone, A.; Camodeca, M. Bullying and Moral Disengagement in Early Adolescence: Do Personality and Family Functioning Matter? J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 2120–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Fadda, S.M.; Castro-Castañeda, R.; Vargas-Jiménez, E.; Musitu-Ochoa, G.; Callejas-Jerónimo, J.E. Victimization among Mexican Adolescents: Psychosocial Differences from an Ecological Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, T.I.; Estévez, E.; Murgui, S. Ambiente comunitario y actitud hacia la autoridad: Relaciones con la calidad de las relaciones familiares y con la agresión hacia los iguales en adolescentes. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).