Submitted:

04 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

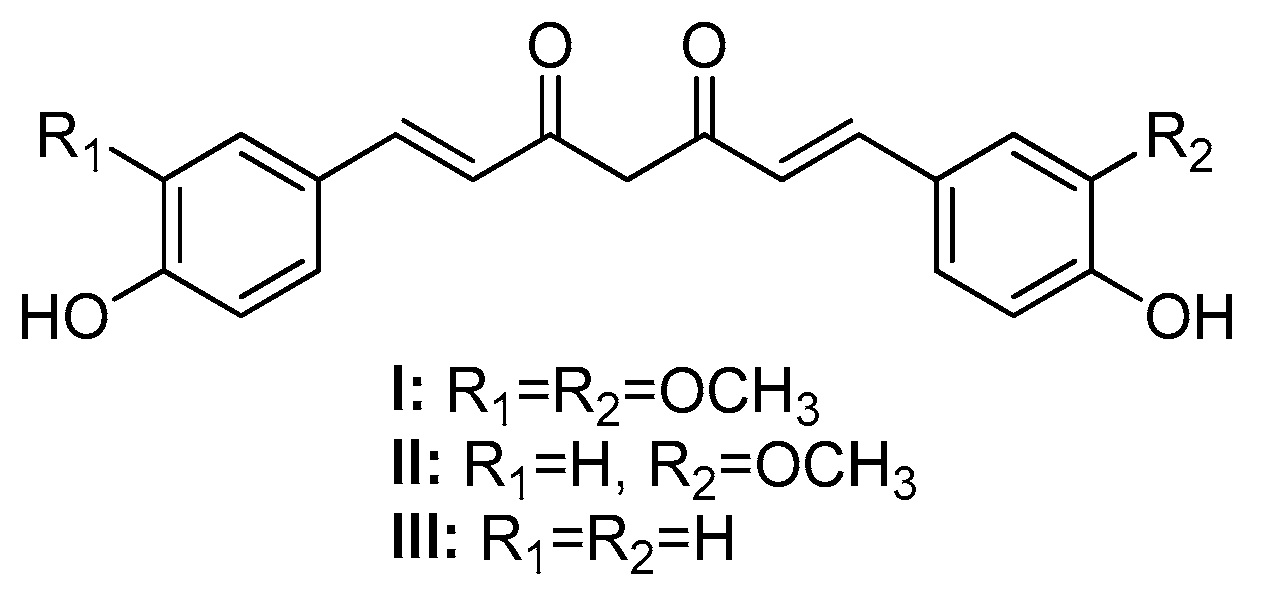

1. Introduction

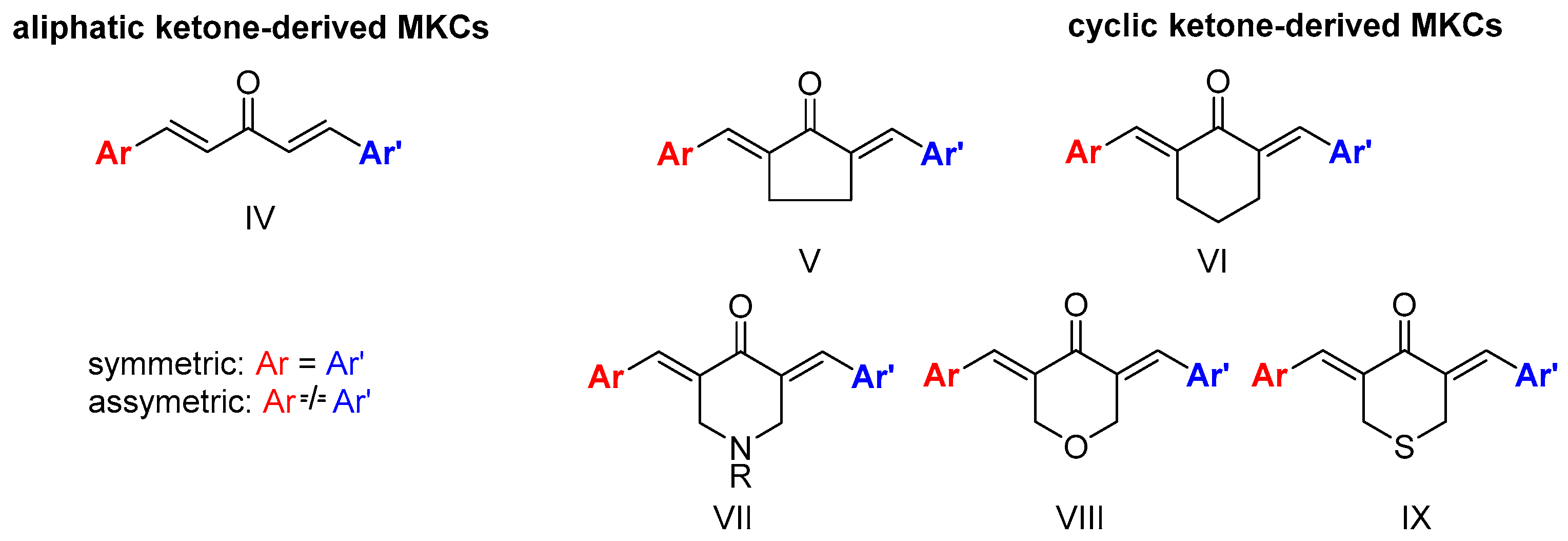

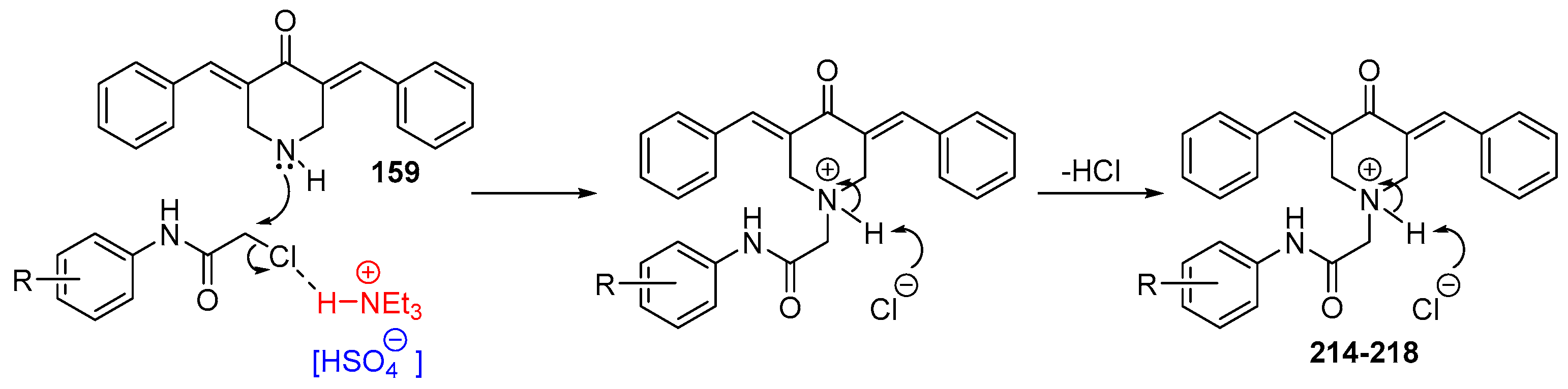

2. Synthesis of Monoketone Curcuminoids (MKCs)

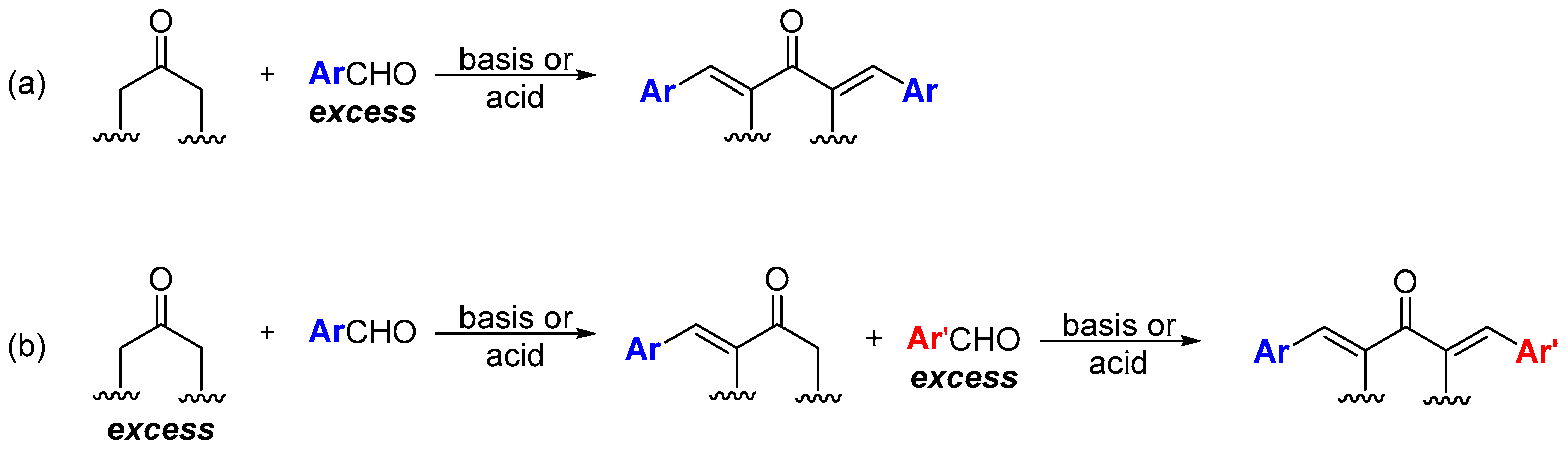

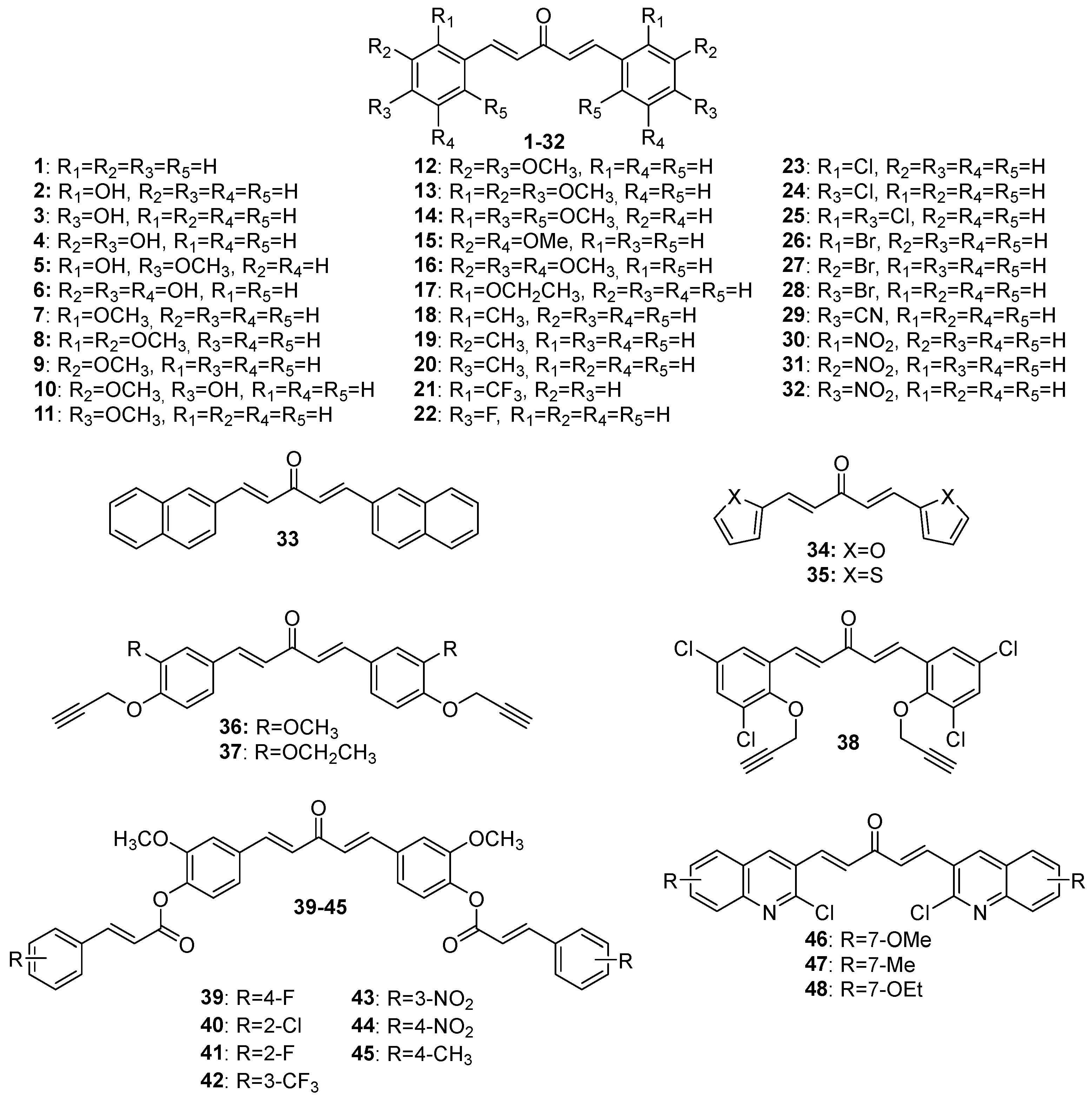

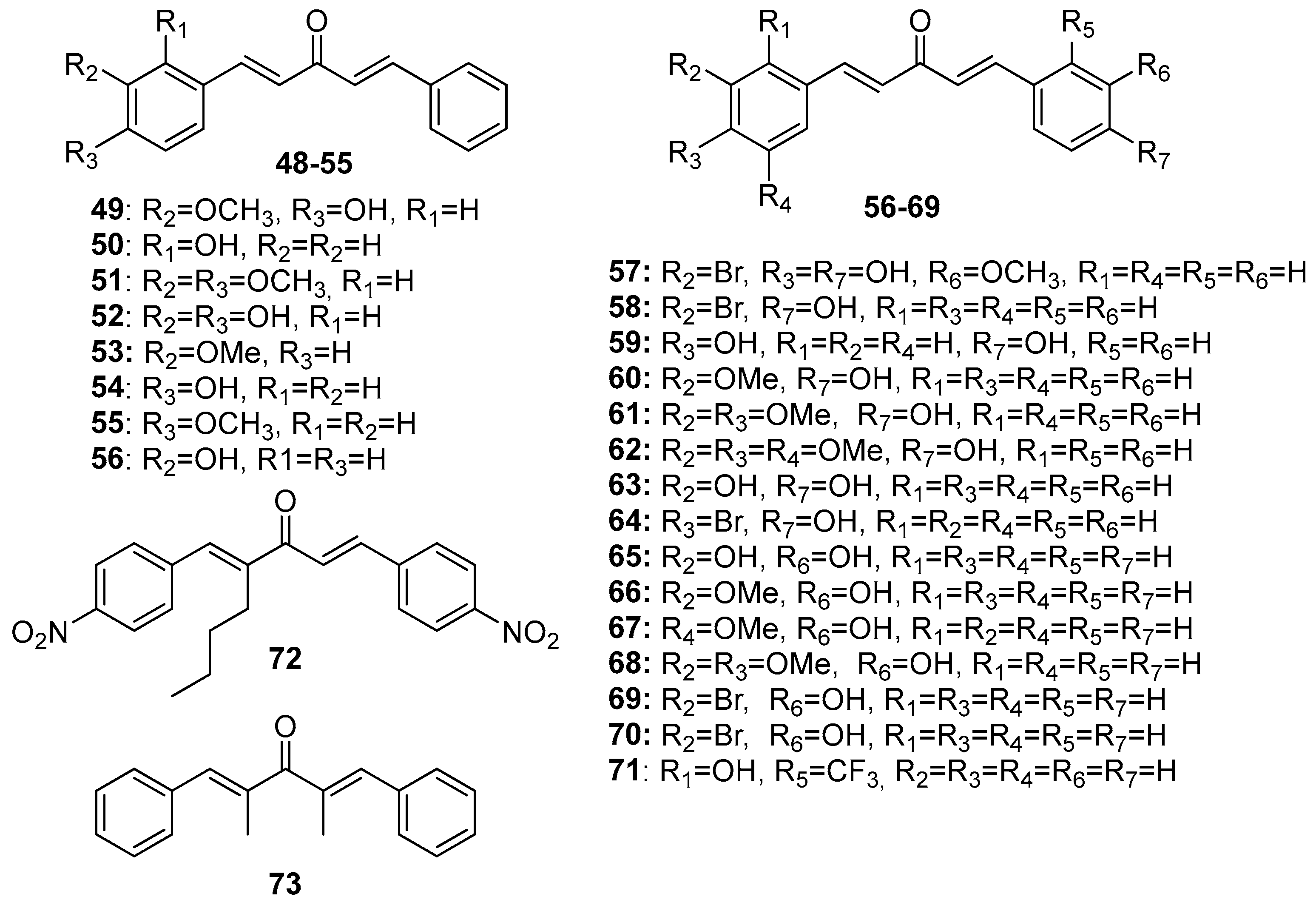

2.1. The Claisen-Schmidt Condensation (CSC) as a Source of MKCs

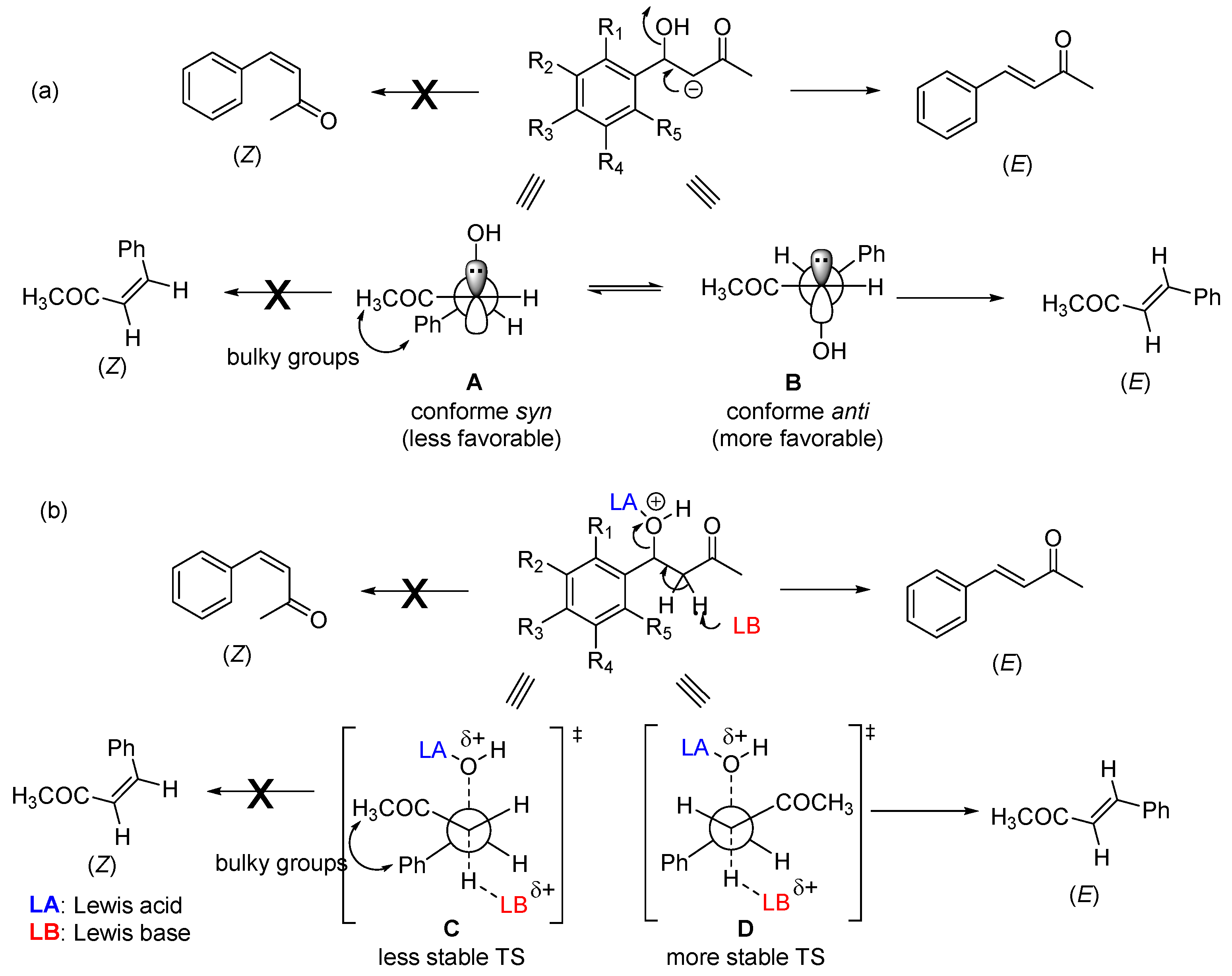

2.1.1. General Aspects and Stereoselectivity

2.1.2. Base-Catalyzed Claisen-Schmidt Condensation

2.1.3. Acid-Catalyzed CSCs

2.2. Synthesis of MKCs through Oxidative Catalysis

2.3. Using Ionic Liquids and Apolar Solvents in the Synthesis of MKCs

3. Biological Activities of MKCs

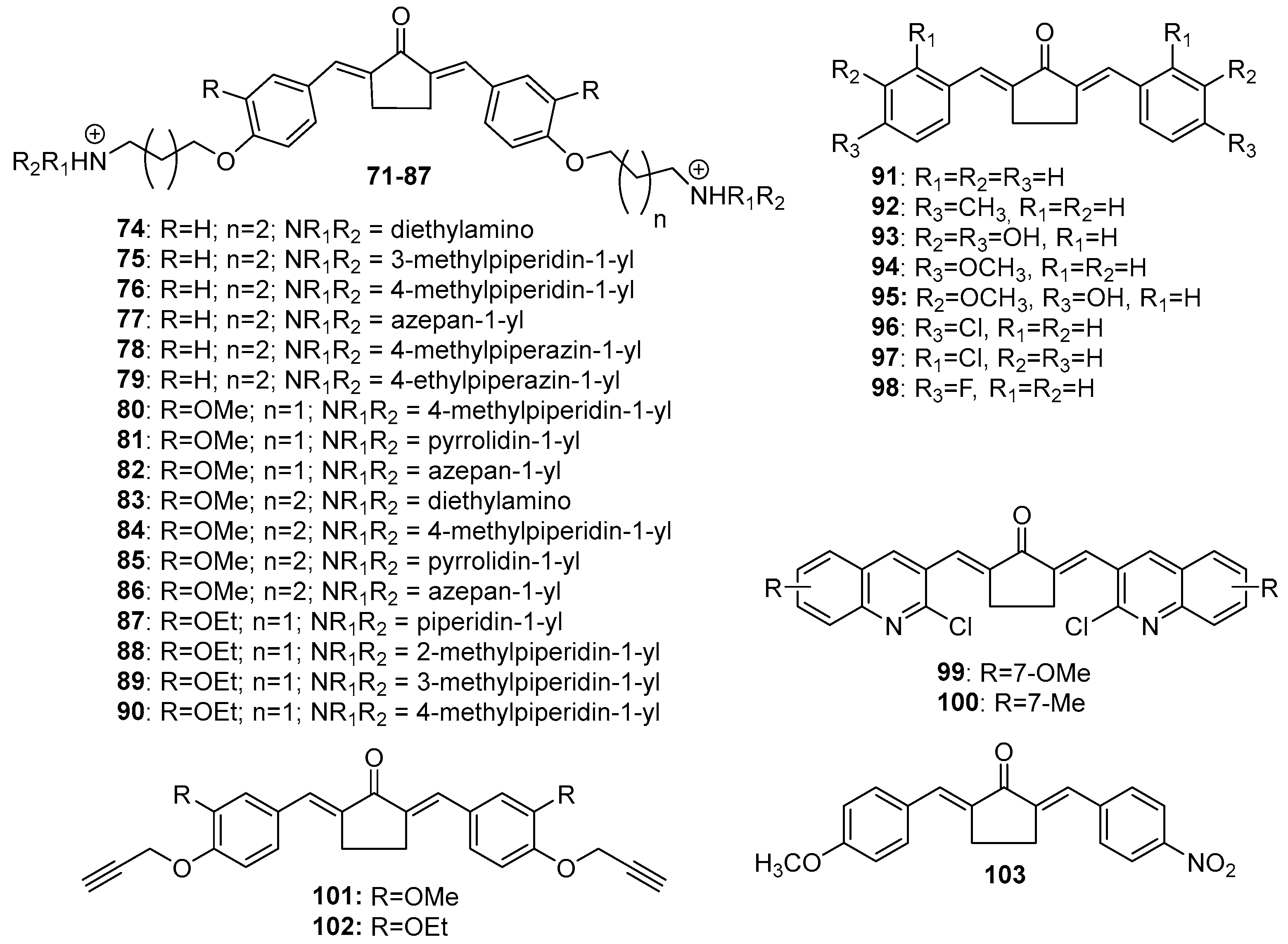

3.1. An Overview of the Biological Activities of MKCs

3.2. Anticancer Activity

3.3. Antimicrobial Activity

3.3.1. Antibacterial Activity

3.3.2. Antifungal Activity

2.3.3. Antiviral Activity

3.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.5. Antiparasitic Activity

3.6. Other Activities

3.6.1. Anti-Angiogenic Activity

3.6.2. Anticoagulant Activity

3.6.3. Antidiabetic Activity

3.6.4. Insecticidal Activity

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; Lu, H.-F.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chen, J.-C.; Chou, W.-H.; Huang, H.-C. Curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin induced caspase-dependent and –independent apoptosis via Smad or Akt signaling pathways in HOS cells. BMC Complement. Med. Therap. 2020, 20, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, M.; Yuan, Y. The potential of curcumin-based co-delivery systems for applications in the food industry: Food preservation, freshness monitoring, and functional food. Food Res. Int. 2023, 171, 113070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bērziņa, L.; Mieriņa, I. Antiradical and antioxidant activity of compounds containing 1,3-dicarbonyl moiety: an overview. Molecules 2023, 28, 6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Qu, Y.; Li, Z.; Fan, B.; Xu, H.; Tang, J. In vitro permeability and bioavailability enhancement of curcumin by nanoemulsion via pulmonary administration. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, H.J.; Schwikkard, S.L.; Khoder, M.; Kelly, A.F. The chemistry, toxicity and antibacterial activity of curcumin and its analogues. Planta Med. 2023. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Verma, S.; Fátima, K.; Luqman, S.; Srivastava, S.K.; Khan, F. Pharmacophore & QSAR guided design, synthesis, pharmacokinetics and in vitro evaluation of curcumin analogs for anticancer activity. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 620–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Ingle, A.P.; Pandit, R.; Paralikar, P.; Anasane, N.; Dos Santos, C.A. Curcumin and curcumin-loaded nanoparticles: antipathogenic and antiparasitic activities. Exp. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Wilson, R.L.; Chowdhury, S.D. Enhancing therapeutic efficacy of curcumin: advances in delivery systems and clinical applications. Gels 2023, 9, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagandeep; Kumar, P. ; Kandi, S.K.; Mukhopadhyay, K.; Rawat, D.S. Synthesis of novel monocarbonyl curcuminoids, evaluation of their efficacy against MRSA, including ex vivo infection model and their mechanistic studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 195, 112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, S.; Dhar, G.; Dwivedi, V.; Das, A.; Poddar, A.; Chakraborti, G.; Basu, G.; Chakrabarti, P.; Surolia, A.; Bhattacharyya, B. Stable and potent analogues derived from the modification of the dicarbonyl moiety of curcumin. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 7449–7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureddin, S.A.; El-Shishtawy, R.M.; Al-Footy, K.O. Curcumin analogues and their hybrid molecules as multifunctional drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 182, 111631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagargoje, A.A.; Akolkar, S.V.; Siddiqui, M.M.; Subhedar, D.D.; Sangshetti, J.N.; Khedkar, V.M.; Shingate, B.B. Quinoline based monocarbonyl curcumin analogs as potential antifungal and antioxidant agents: synthesis, bioevaluation and molecular docking study. Chem. Biodiv. 2020, 17, e1900624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.; Saraiva, L.; Pinto, M.M.; Cidade, H. Diarylpentanoids with antitumor activity: a critical review of structure-activity relationship studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 192, 112177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.; Faudzi, S.M.M.; Nasir, N.M. A review on biological properties and synthetic methodologies of diarylpentadienones. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Singh, V.; Shankar, R.; Kumar, K.; Rawal, R.K. Synthetic and medicinal prospective of structurally modified curcumins. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivedha, J.; Kanimozhi, K.; Olikkavi, S.; Vidhyasagar, T.; Vijayakumar, N.; Uma, C.; Rajeswari, K.; Vennila, L. In vitro screening for antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of 3,5-bis(e-thienylmethylene) piperidin-4-one, a curcumin analogue. Pharmacogn. Res. 2022, 14, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawbecker, B.L.; Kurtz, D.W.; Putnam, T.D.; Ahlers, P.A.; Gerber, G.D. The aldol condensation: a simple teaching model for organic laboratory. J. Chem. Ed. 1978, 55, 540–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.D.; Wagh, D.P. Claisen-Schmidt condensation using green catalytic processes: a critical review. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 9059–9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhedar, D.D.; Shaikh, M.H.; Nagargoje, A.A.; Akolkar, S.V.; Bhansali, S.G.; Sarkar, D.; Shingate, B.B. Amide-linked monocarbonyl curcumin analogues: efficient synthesis, antitubercular activity and molecular docking study. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2020, 42, 2655–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrig, J.R.; Beyer, B.G.; Fleischhacker, A.S.; Ruthenburg, A.J.; John, S.G.; Snyder, D.A.; Nyffeler, P.T.; Noll, R.J.; Penner, N.D.; Phillips, L.A.; et al. Does activation of the anti proton, rather than concertedness, determine the stereochemistry of base-catalyzed 1,2-elimination reactions? Anti stereospecificity in E1cb eliminations of β-3-trifluoromethylphenoxy esters, thioesters, and ketones. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 2819–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clariano, M.; Marques, V.; Vaz, J.; Awam, S.; Afonso, M.B.; Perry, M.J.; Rodrigues, C.M.P. Monocarbonyl analogs of curcumin with potential to treat colorectal cancer. Chem. Biodiv. 2023, 20, e2023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, H.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Schobert, R.; Dandawate, P.; Biersack, B. Fluorinated and N-acryloyl-modified 3,5-di[(E)-benzylidene]piperidin-4-one curcuminoids for the treatment of pancreatic carcinoma. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Cao, W.; Zhao, L.; Han, Q.; Yang, S.; Yang, K.; Pan, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y. Design, synthesis, and antitumor evaluation of novel mono-carbonyl curcumin analogs in hepatocellular carcinoma cell. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.C.; Pacheco, B.S.; Nascimentos das Neves, R.; Dié Alves, M.S.; Sena-Lopes, Â.; Moura, S.; Borsuk, S.; Pereira, C.M. Antiparasitic activity of synthetic curcumin monocarbonyl analogues against Trichomonas vaginalis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, M.; Yang, C.; Yu, L.; Xu, Q. Gram-scale preparation of dialkylideneacetones through Ca(OH)2 - catalyzed Claisen-Schmidt condensation in dilute aqueous EtOH. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureddin, S.A.; El-Shishtawy, R.M.; Al-Footy, K.O. Synthesis of new symmetric cyclic and acyclic halocurcumin analogues typical precursors for hybridization. Rev. Chem. Intermed. 2020, 46, 5307–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, I.; Zupkó, I.; Gyovai, A.; Horváth, P.; Kiss, E.; Gulyás-Fekete, G.; Schmidt, J.; Perjési, P. A novel cluster of C5-curcuminoids: design, synthesis, in vitro antiproliferative activity and DNA binding of bis(arylidene)-4-cyclanone derivatives based on 4-hydroxycyclohexanone scaffold. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 4711–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, C.; Cao, E.; Cattaneo, S.; Brett, G.L.; Miedziak, P.J.; Wu, G.; Sankar, M.; Hutchings, G.J.; Gavriilidis, A. Three step synthesis of benzylacetone and 4-(4-methoxyphenyl)butan-2-one in flow using micropacked bed reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 377, 119976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.C.; Kumar, N.V.A.; Thakur, G. Developments in the anticancer activity of structurally modified curcumin: an up-to-date review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 177, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauinoglou, E.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. Curcumin analogues and derivatives with anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory activity: Structural characteristics and molecular targets. Ex. Opin. Drug Discov. 2019, 14, 821–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeri, A.; Ward, N.; Panahi, Y.; Sahebkar, A. Anti-angiogenic activity of curcumin in cancer therapy: a narrative review. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2019, 17, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Yadav, V.R.; Ravindran, J.; Aggarwal, B.B. ROS and CHOP are critical for dibenzylideneacetone to sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL through induction of death receptors and downregulation of cell survival proteins. Cancer Res. 2019, 71, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zheng, P.; Shen, X.; Shao, R.; Wang, B.; Shen, H.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zou, P. Curcuminoid WZ26, a TrxR1 inhibitor, effectively inhibits colon cancer cell growth and enhances cisplatin-induced cell death through the induction of ROS. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 14, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Cao, P.; Rajamanickam, V.; Wu, C.; Zhou, H.; Cai, Y.; Liang, G.; et al. Curcuminoid B63 induces ROS-mediated paraptosis-like cell death by targeting TrxR1 in gastric cells. Redox Biol. 2019, 21, 101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.Q.; Rajadurai, P.; Abas, F.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Proteomic analysis on anti-proliferative and apoptosis effects of curcumin analog, 1,5-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methyoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadiene-3-one-treated human glioblastoma and neuroblastoma cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 645856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, N.A.A.; Abas, F.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Diarylpentanoid (1,5-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadiene-3-one) (MS13) exhibits anti-proliferative, apoptosis induction and anti-migration properties on androgen-independent human prostate cancer by targeting cell cycle–apoptosis and PI3K signalling pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 707335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajuddin, W.N.B.W.M.; Abas, F.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Molecular mechanisms of antiproliferative and apoptosis activity by 1,5-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)1,4-pentadiene-3-one (MS13) on human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroe, J.D.; Hodzic, D.; Millay, M.H.; G., P.B.; Smith, M.E. Anti-cancer and ototoxicity characteristics of the curcuminoids, CLEFMA and EF24, in combination with cisplatin. Molecules 2019, 24, 3889. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, J.; Almeida, J.; Loureiro, J.B.; Ramos, H.; Palmeira, A.; Pinto, M.M.; Saraiva, L.; Cidade, H. A diarylpentanoid with potential activation of the p53 pathway: combination of in silico screening studies, synthesis, and biological activity evaluation. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 2969–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, P.; Silva, P.M.A.; Moreira, J.; Palmeira, A.; Amorim, I.; Pinto, M.; Cidade, H.; Bousbaa, H. BP-M345, a new diarylpentanoid with promising antimitotic activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, S.A.A.; Sobh, R.A.; Mourad, R.M. Investigating the Effect of loading curcuminoids using PCL-PU-βCD nano-composites on physico-chemical properties, in-vitro release, and ex-vivo breast cancer cell-line. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 12, 4074–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.S.C.; Lam, K.W.; Rajab, N.F.; Jamal, A.R.A.; Kamaluddin, N.F.; Chan, K.M. Curcumin piperidone derivatives induce anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effects in LN-18 human glioblastoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, T.; Khan, A.; Abbass, M.; Filho, E.R.; Din, Z.U.; Khan, A. Synthesis, characterization, molecular docking, analgesic, antiplatelet and anticoagulant effects of dibenzylidene ketone derivatives. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.W.; Awin, T.; Faudzi, S.M.M.; Maulidiani, M.; Shaari, K.; Abas, F. Synthesis and biological evaluation of asymmetrical diarylpentanoids as antiinflammatory, anti-α-glucosidase, and antioxidant agents. Med. Chem. Res. 2019, 28, 2002–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondhare, D.; Deshmukh, S.; Lade, H. Curcumin Analogues with aldose reductase inhibitory activity: synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking. Processes 2019, 7, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, C.L.; Yeoh, S.Y.; Harith, H.H.; Israf, D.A. A synthetic curcuminoid analogue, 2,6-bis-4-(hydroxyl-3-methoxybenzylidine)-cyclohexanone (BHMC) ameliorates acute airway inflammation of allergic asthma in ovalbuminsensitized mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 9725903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, A.; Pilankatta, R.; Teramoto, T.; Sajith, A.M.; Nwulia, E.; Kulkarni, A.; Padmanabhan, R. Inhibition of dengue virus by curcuminoids. Antivir. Res. 2019, 162, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagargoje, A.A.; Akolkar, S.V.; Subhedar, D.D.; Shaikh, M.H.; Sangshetti, J.N.; khedari, V.M.; Shingate, B.B. Propargylated monocarbonyl curcumin analogues: synthesis, bioevaluation and molecular docking study. Med. Chem. Res. 2020, 29, 1902–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaquini, C.R.; Marques, B.C.; Ayusso, G.M.; Morão, L.G.; Sardi, J.C.O.; Campos, D.L.; Silva, I.C.; Cavalca, L.B.; Scheffers, D.-J.; Rosalen, P.L.; et al. Antibacterial activity of a new monocarbonyl analog of curcumin MAC 4 is associated with divisome disruption. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 109, 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, D.R.; Thendral, E.D.; Priya, M.K.; Shirmila, D.A.; Fathima, A.A.; Yuvashri, R.; Usha, G. Investigations on 3D-structure, properties and antibacterial activity of two new curcumin derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1292, 136063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, I.S.; Rao, G.S.; Shankar, J.; Chauhan, L.K.S.; Kapadia, G.J.; Singh, N. Chemoprevention of leishmaniasis: in-vitro antiparasitic activity of dibenzalacetone, a synthetic curcumin analog leads to apoptotic cell death in Leishmania donovani. Parasitol. Int. 2018, 67, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Chauhan, I.S. MicroRNA expression profiling of dibenzalacetone (DBA) treated intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania donovani. Exp. Parasitol. 2018, 193, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, I.S.; Rao, G.S.; Subba, G.; Singh, N. Enhancing the copy number of Ldrab6 gene in Leishmania donovani parasites mediates drug resistance through drug-thiol conjugate dependent multidrug resistance protein A (MRPA). Acta Trop. 2019, 199, 105158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, I.S.; Marwa, S.; Rao, G.S.; Singh, N. Antiparasitic dibenzalacetone inhibits the GTPase activity of Rab6 protein of Leishmania donovani (LdRab6), a potential target for its antileishmanial effect. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 2991–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.M.; Vieira, T.M.; Cândido, A.C.B.B.; Tezuka, D.Y.; Rao, G.S.; Albuquerque, S.; Crotti, A.E.M.; Siqueira-Neto, J.L.; Magalhães, L.G. In vitro anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity enhancement of curcumin by its monoketone tetramethoxy analog diveratralacetone. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2021, 1, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, K.R.; Monti, L.; Yang, W.; Park, H.; Liu, L.J.; Watkins, K.; Amarasinghe, D.K.; Nalli, M.; Polaquini, C.R.; Regasini, L.O.; et al. Structure-activity relationship of dibenzylideneacetone analogs against the neglected disease pathogen, Trypanosoma brucei. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 81, 129123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, A.; Jain, S.; Gautam, R.D. Investigation of insecticidal activity of some α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds and their synergistic combination with natural products against Phenacoccus solenopsis tinsley. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2012, 52, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstrom, D.M.; Zhou, X.; Kalk, C.N.; Song, B.; Lan, Q. Mosquitocidal properties of natural product compounds isolated from chinese herbs and synthetic analogs of curcumin. J. Med. Entomol. 2012, 49, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiadis, D.; Liggri, P.G.V.; Kritsi, E.; Tzioumaki, N.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Papachristos, D.P.; Balatsos, G.; Sagnou, M.; Michaelakis, A. Curcumin derivatives as potential mosquito larvicidal agents against two mosquito vectors, Culex pipiens and Aedes albopictus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debela, D.T.; Muzazu, S.G.Y.; Heraro, K.D.; Ndalama, M.T.; Mesele, B.W.; Haile, D.C.; Kitui, S.K.; Manyazewal, T. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211034366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Peng, J.; guo, L.; Hu, J.; Cao, M.; zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; et al. A synthetic compound, 1,5-bis(2-methoxyphenyl)penta- 1,4-dien-3-one (B63), induces apoptosis and activates endoplasmic reticulum stress in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 131, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, K.; Dozmorov, M.G.; Anant, S.; Awasthi, V. The curcuminoid CLEFMA selectively induces cell death in H441 lung adenocarcinoma cells via oxidative stress. Invest. New Drugs 2012, 30, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Sidell, N.; Mancini, A.; Huang, R.-P.; Wang, S.; Horowitz, I.R.; Liotta, D.C.; Taylor, R.N.; Wieser, F. Multiple anticancer activities of EF24, a novel curcumin analog, on human ovarian carcinoma cells. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 17, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Xia, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W.; Chen, M.; Kanchana, K.; Yang, S.; Liang, G. Selective killing of gastric cancer cells by a small molecule targeting ROS-mediated ER stress activation. Mol. Carcinog. 2016, 55, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citalingam, K.; Abas, F.; Lajis, N.H.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Antiproliferative effect and induction of apoptosis in androgen-independent human prostate cancer cells by 1,5-bis(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadiene-3-one. Molecules 2015, 20, 3406–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulraj, F.; Abas, F.; Lajis, N.H.; Othman, I.; Hassan, S.S.; Naidu, R. The curcumin analogue 1, 5-bis(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadiene-3-one induces apoptosis and downregulates E6 and E7 oncogene expression in HPV16 and HPV18-infected cervical cancer cells. Molecules 2015, 20, 11830–11860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Maruyama, T.; Miura, M.; Inoue, M.; Fukuda, K.; Shimazu, K.; Taguchi, D.; Kanda, H.; Oshima, M.; Iwabuchi, Y.; et al. Dietary intake of pyrolyzed deketene curcumin inhibits gastric carcinogenesis. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 50, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, L.; Hutzen, B.; Ball, S.; DeAngelis, S.; chen, C.L.; Fuchs, J.R.; Li, C.; Li, P.-K.; Lin, J. New structural analogues of curcumin exhibit potent growth suppressive activity in human colorectal carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagandeep; Singh, M.; Kidawi, S.; Das, U.S.; Velpandian, T.; Singh, R.; Rawat, D.S. Monocarbonyl curcuminoids as antituberculosis agents with their moderate in-vitro metabolic stability on human liver microsomes. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2021, 2021, e22754. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.R.; Parks, R.J. Curcumin as an antiviral agent. Viruses 2020, 12, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardebili, A.; Pouriayevali, M.H.; Aleshikh, S.; Zahani, M.; Ajorloo, M.; Izanloo, A.; Siyadapanah, A.; Nikoo, H.R.; Wilairatana, P.; Coutinho, H.D.M. Antiviral therapeutic potential of curcumin: an update. Molecules 2021, 26, 6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Kulkami, A.A.; Lin, X.; McLean, C.; Ammosova, T.; Ivanov, A.; Hipolito, M.; Nekhai, S.; Nwilia, E. Inhibition of hiV-1 by curcumin a, a novel curcumin analog. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015, 9, 5051–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, N.; Rani, A.N.A.; Mahmud, R.; Yin, K.B. Antioxidant and cytotoxic effect of Barringtonia racemosa and Hibiscus sabdariffa fruit extracts in MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Pharmacogn. Res. 2020, 8, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Shah, D.; Khan, I.; Ahmad, S.; Ali, U.; Rahman, A.U. Synthesis and antioxidant activities of schiff bases and their complexes: an updated review. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2020, 10, 6936–6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohutia, C.; Chetia, D.; Gogoi, K.; Sarma, K. Design, in silico and in vitro evaluation of curcumin analogues against Plasmodium falciparum. Exp. Parasitol. 2017, 175, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, E.; Varela, J.; Birriel, E.; Serna, E.; Torres, S.; Yaluff, G.; Bilbao, N.V.; Aguirre-López, B.; Cabrera, N.; Mazariegos, S.D.; et al. Potent and selective inhibitors of Trypanosoma cruzi triosephosphate isomerase with concomitant inhibition of cruzipain: inhibition of parasite growth through multitarget activity. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, T.M.; Santos, I.A.; Silva, T.S.; Martins, C.H.G.; Crotti, A.E.M. Antimicrobial activity of monoketone curcuminoids against cariogenic bacteria. Chem. Biodiv. 2018, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, T.M.; Ambrosio, M.A.L.V.; Martins, C.H.G.; Crotti, A.E.M. Structure-antimicrobial activity relationships of monoketone curcuminoids. Int. J. Complement. Alt. Med. 2018, 11, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Du, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Jin, Y. Transdermal delivery of the in situ hydrogels of curcumin and its inclusion complexes of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin for melanoma treatment. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 469, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

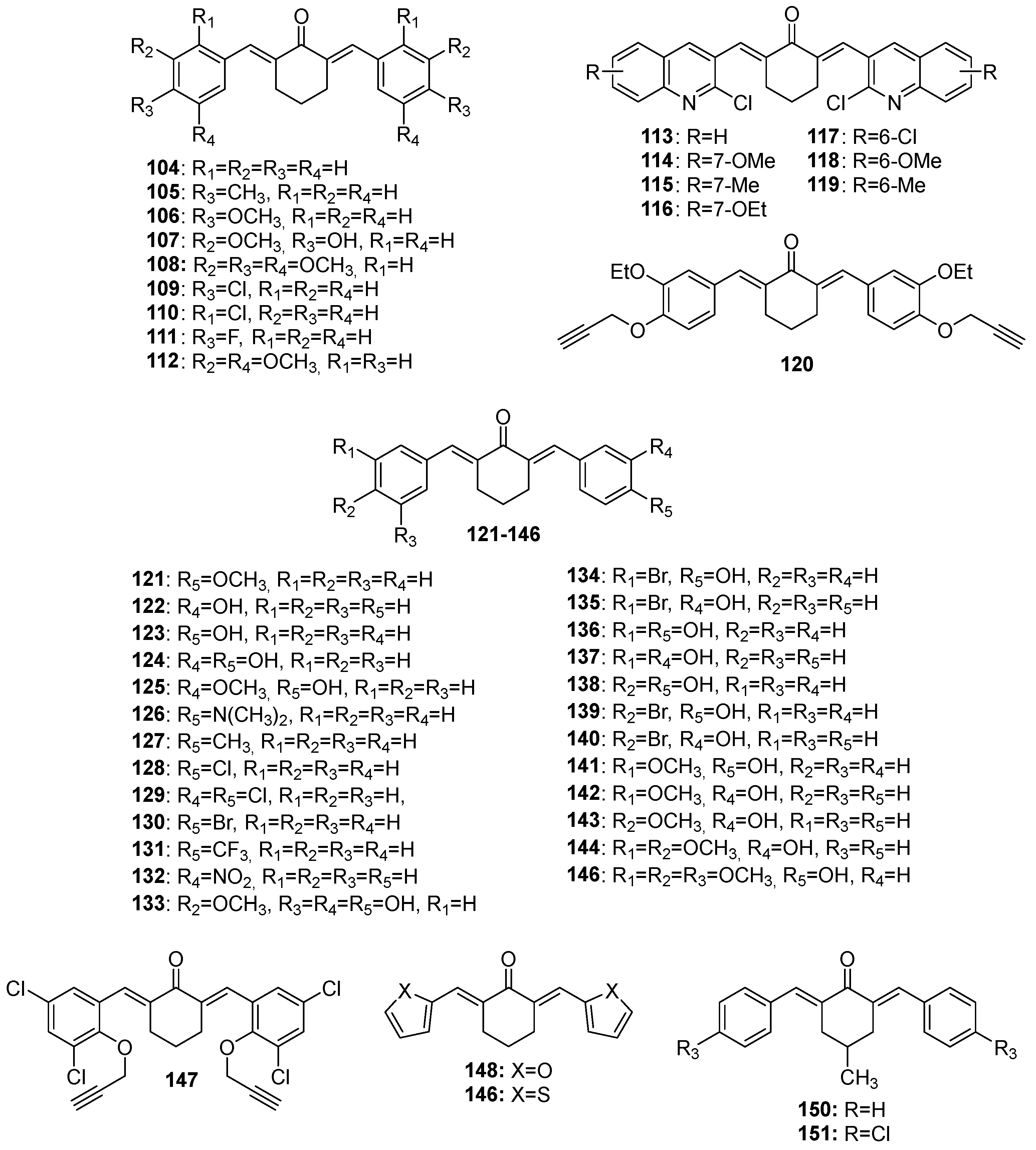

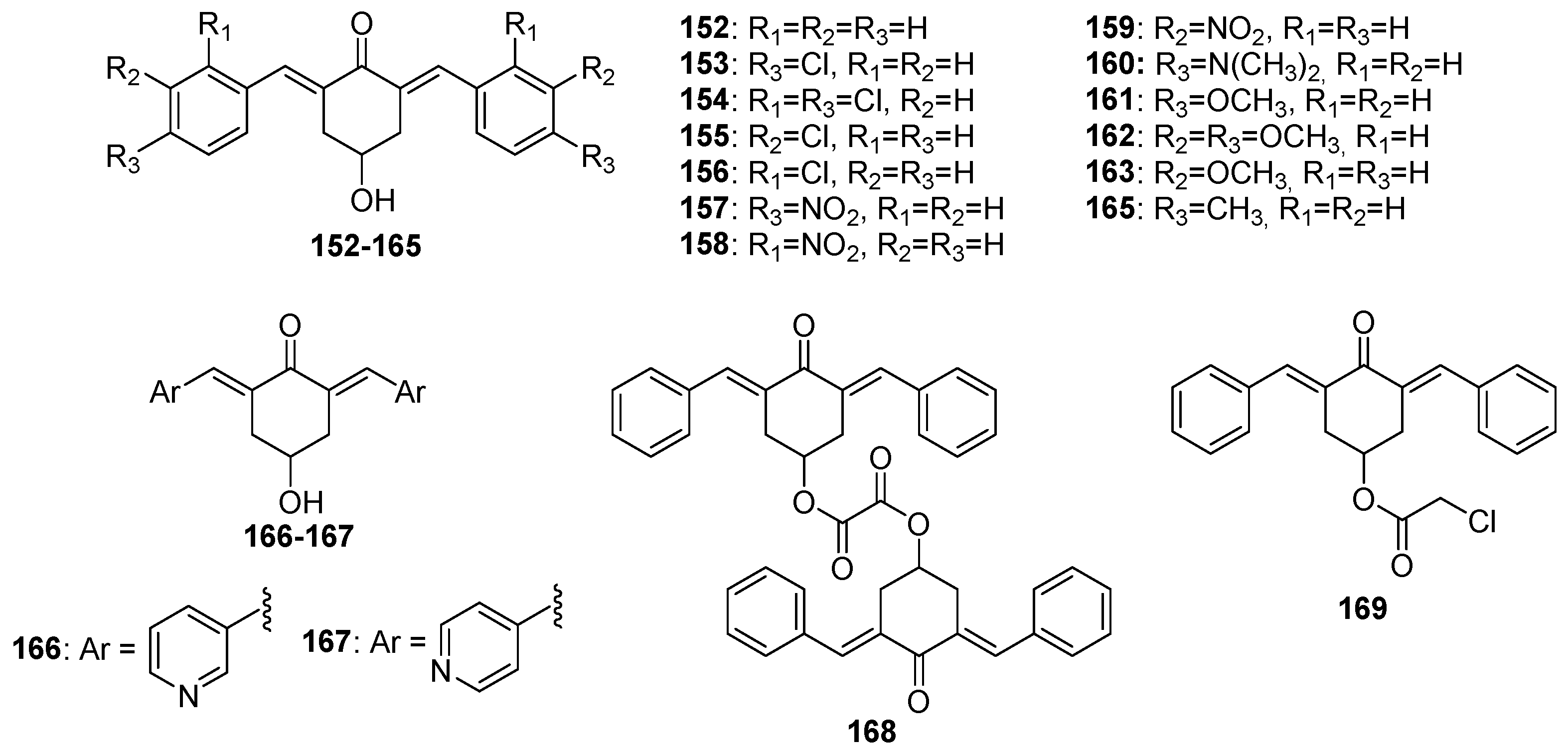

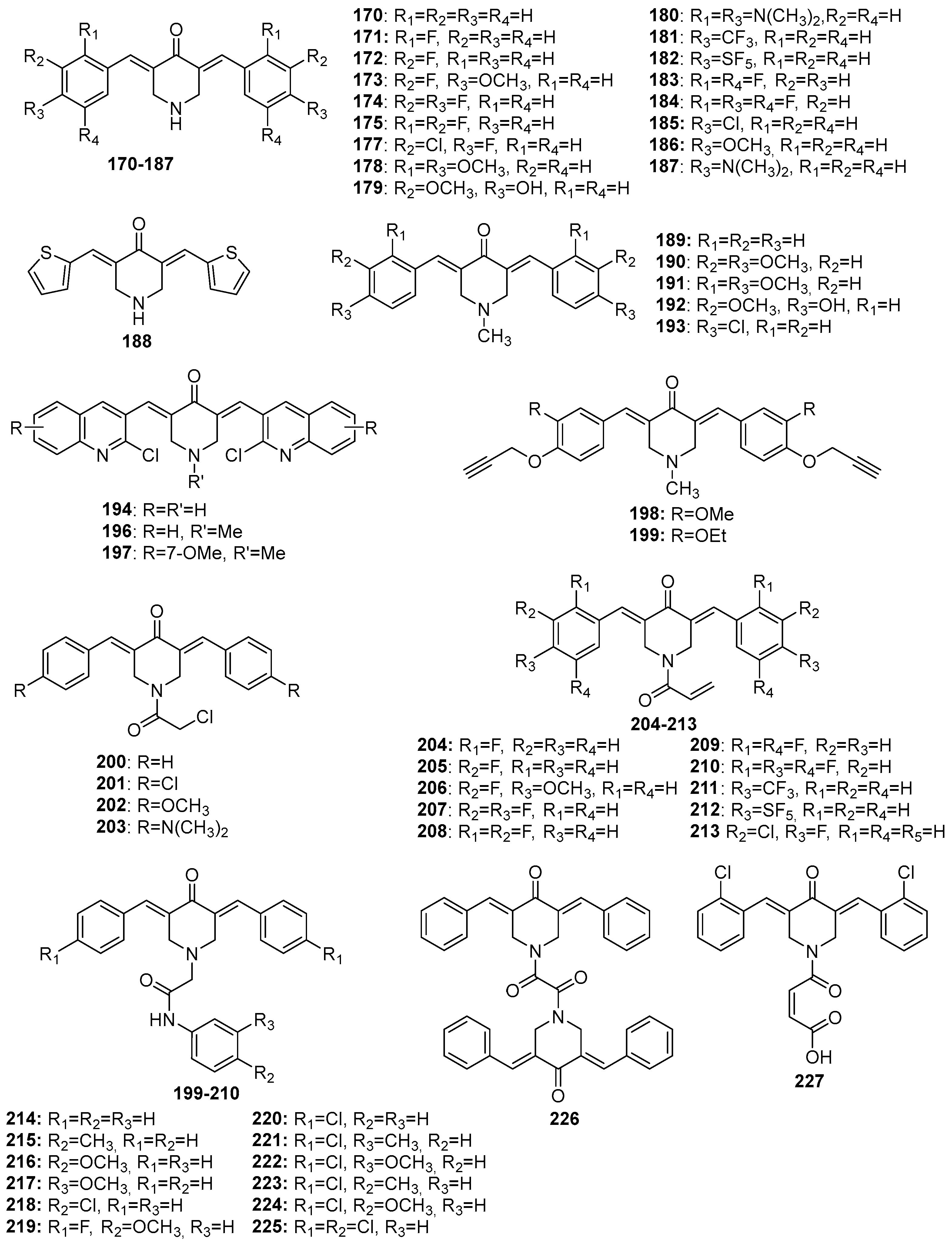

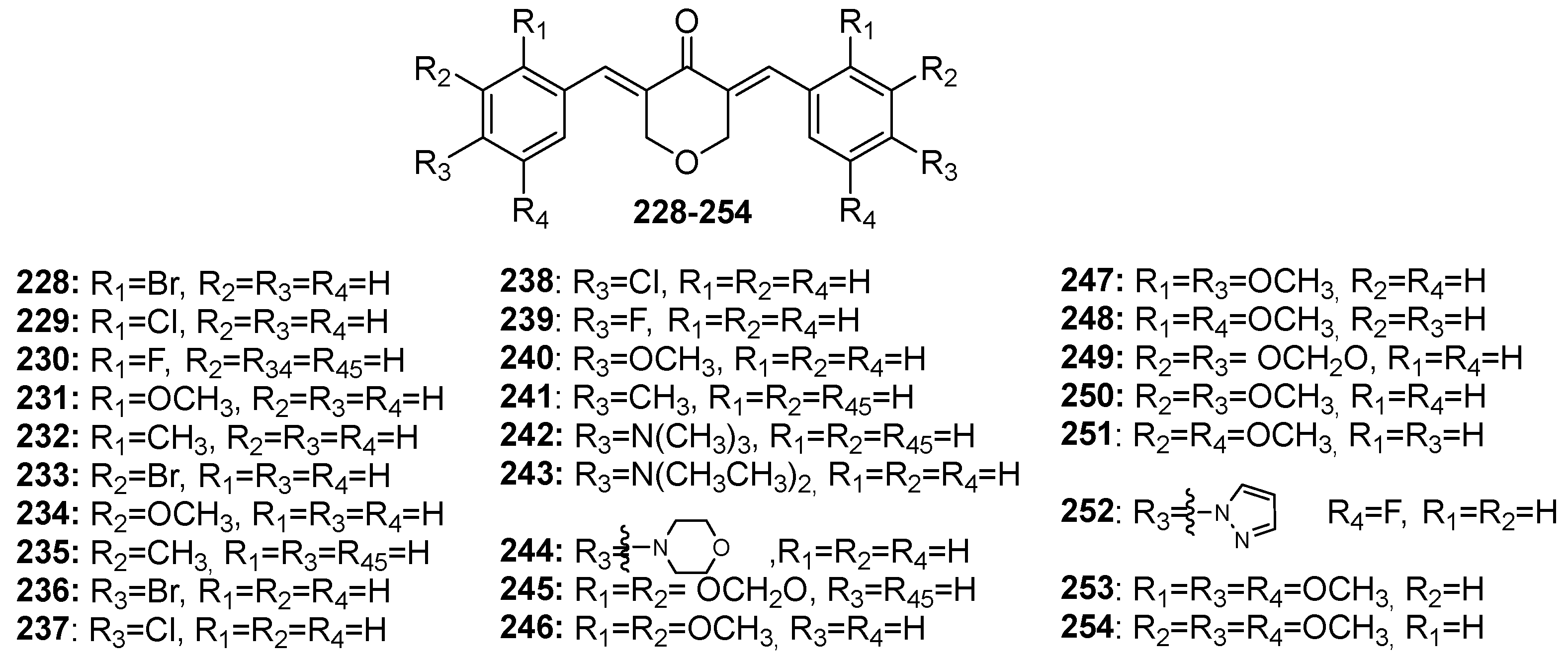

| Activity | Compounds | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Antiangiogenic | 8 | [31] |

| Anticancer | 1 | [32] |

| 57 | [33] | |

| 7 | [34] | |

| 10 | [35,36,37] | |

| 171, 227 | [38] | |

| 10, 73, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 185, 186, 187, 189, 193, 200, 201, 202, 203, 226 | [27] | |

| 228, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237*, 238, 239, 240, 241, 242, 243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 2487, 249, 250, 251, 252, 253, 254* | [39] | |

| 254 | [40] | |

| 1, 35 | [41] | |

| 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 | [23] | |

| 179, 192 | [42] | |

| 171, 172*, 173, 174, 175, 177, 181, 182, 183, 184, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213 | [22] | |

| 1, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 18, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | [21] | |

| Anti-coagulant | 72, 103 | [43] |

| Anti-diabetic | 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 | [44] |

| 1, 8*, 11*, 16, 19, 20, 24, 25, 28, 31, 33 | [45] | |

| Anti-inflammatory | 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65*, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 | [44] |

| 107 | [46] | |

| Antimicrobial | 10, 95*, 107 | [47] |

| 46, 47, 48, 99, 100*, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 194, 195, 196, 197* | [12] | |

| 36, 37, 38, 101, 102, 120*, 147, 198, 199 | [48] | |

| 1, 49, 50, 51, 52*, 53, 54, 55 | [49] | |

| 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89*, 90 | [9] | |

| 188 | [16] | |

| 190*, 191 | [50] | |

| Antioxidant | 46, 47, 48, 99, 100*, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 194, 195, 196, 197* | [12] |

| 36, 37, 38, 101, 102, 120*, 147, 198, 199 | [48] | |

| 188 | [16] | |

| Antiparasitic | 1 | [51,52,53,54] |

| 1, 11, 20, 22, 23, 24, 91, 92, 94, 96, 97, 98, 104, 105, 106, 109, 110, 111 | [24] | |

| 1, 11, 12*, 14, 24 | [55] | |

| 1, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 20, 22, 23, 27, 112, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 171 | [56] | |

| Insecticidal | 1, 2, 5, 34 | [57] |

| 3, 16, 50, 71, 108, 148 | [58] | |

| 4, 6, 10, 11, 12*, 16, 93, 148, 149 | [59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).