1. Introduction

Ground-based planetary radars play a fundamental role in enhancing our knowledge of near-Earth Objects (NEOs) by refining their orbits and characterizing their physical properties, shape and size. Radar observations of NEOs are crucial, not only from a scientific point of view, but also in the field of planetary defense and as support to space missions. Asteroid radar astronomy began in the late 1960s with the observation of 1566 Icarus [

1] and radars still remain one of the most powerful tools for studying this type of object. The technique consists of transmitting radio signals toward the asteroid and receiving the reflected wave (echo). The signal is typically transmitted coherently with polarization state and time/frequency structure perfectly known and fully controlled. The modifications of these characteristics measured in the received echo provide accurate information about the dynamical and structural properties of the target. By exploiting radar echoes time delay and/or Doppler shift measurements, it is possible to estimate range and radial velocity (range-rate) with accuracy as small as 10 m in range and 1 mm/s in range-rate [

2], allowing to significantly improve the orbits of objects observed with optical systems only. In some cases, from radar observations, it is possible to determine subtle non-gravitational perturbations as for the Yarkovsky effect [

3]. Moreover, ground-based radars can obtain Delay-Doppler images of NEOs surfaces with a few meter range resolution, discover asteroid satellites [

4], and provide other important information. Details on the capabilities of the planetary radar facilities and techniques can be found in many reviews on radar observations of both NEOs and Main Belt asteroids (e.g. [

5,

6,

7]).

After the Arecibo radio telescope collapse in December 2020, the largest operational ground-based planetary radar for observing NEOs is the Goldstone Solar System Radar (GSSR) facility (California) implemented on the 70-m DSS-14 antenna. Planetary radar experiments have occasionally been carried out with other transmitting antennas of the Deep Space Network (DSN) such as the DSS-13 (34-m diameter) at Goldstone and the 70-m DSS-43 dish at the Canberra Deep Space Communications Complex (e.g. [

8,

9]). These transmitters have also been used in bistatic configurations with receiving antennas, such as the Green Bank radio telescope and the Very Large Array (VLA) (e.g. [

10]). Among these, there are the antennas with which we conducted the observations we are presenting and which we will describe later.

In 2019 the European Space Agency issued a call for tenders (SSA P3-NEO-XXII, "NEO Observation Concepts for Radar Systems"), which has successfully concluded in 2022, proposing a study on the requirements that a radar system must meet for NEO observations, both for scientific and planetary defense purposes, with specific attention to an evaluation of the European assets that might be employed/upgraded for such activities - also taking into account the tools and expertise that are needed in the post-observation phases. Test observations were an important part of this project, in view of the constitution of a possible future NEO European radar network led by ESA. The collaboration was conducted by SpaceDyS company and included the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) and the University of Helsinki, with the kind contribution granted by the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Madrid Deep Space Communications Complex (MDSCC) for the execution of radar observations.

This paper presents the preliminary results of experiments conducted during and after the mentioned ESA project.

Section 2 provides a summary of the outcomes from the performance analysis conducted in the first part of the project. In

Section 3, the facilities used in the test observations are described.

Section 4 outlines the observation planning and selection criteria for targets.

Section 5 is dedicated to presenting the results of some selected observations and is divided into three Subsections, each focusing on a specific target (2021 AF8, (4660) Nereus and 2005 LW3). Finally, conclusions are provided in

Section 6.

2. Highlights from the study on general requirements and performance analysis

The first part of the study was aimed at deriving the general functional requirements for a radar system dedicated to NEO observation for both astrometry and imaging. This general analysis covered many aspects, such as transmitted and received frequency, bandwidth, pointing and tracking accuracy, signal waveform, polarization, sensitivity, measurement resolution, and accuracy. The following phase consisted of surveying the existing European facilities that might contribute to the constitution of a NEO radar system or network. Several medium-to-large diameter radio telescopes, though heavily scheduled with astrophysical activities, could be employed for a limited number of experiments as receiving components in bistatic or multistatic observations. Moreover, Europe already hosts transmitting antennas (e.g. Cebreros [

11], TIRA [

12], DSS-63 [

13]) whose potential, both considering the presently available transmitters and their possible upgrades, was analyzed in our study.

To evaluate the expected performance of a NEO radar system, we produced custom code in Matlab [

14] programming language. We considered different frequency bands, including the historically employed ones (L at TIRA, S at Arecibo and X at Goldstone), and the possibility of operating at higher frequencies, particularly in the Ka-band (∼34 GHz), which has been hypothesized for the Green Bank Telescope (GBT) [

15]. We estimated the number of detectable NEOs per year - whose echo would exceed a given Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) value - as a function of the transmitted power, for four different transmitted frequencies: L (1.333 GHz), S (2.38 GHz), X (8.56 GHz) and Ka (34.0 GHz), corresponding to existing radar systems or taken into account for the possible design of future planetary radar instruments. The technical parameters were inspired by the ones characterizing real antennas, when such examples were available in the various bands, otherwise plausible values were derived/rescaled according to literature. In

Table 1 are listed the main parameters of the sensors used in the simulations: radio frequency band with the operating frequency, antenna size, the noise temperature

due to the antenna and its microwave components (without atmosphere noise temperature) and the antenna gain. Here the antenna gain is expressed in dBi:

, where

is the antenna aperture efficiency,

is the geometric area of the antenna and

is the radar wavelength.

A standard atmospheric model [

16] was applied to estimate the atmospheric attenuation and noise temperature at the considered frequencies in four weather scenarios. Such weather profiles were derived from statistics measured at the MDSCC [

17]. As potential targets, we used the list of NEOs that had a close approach to Earth in the solar year 2020 at a distance ≤0.2 astronomical unit (au) (divided into 3 size categories: all, ≥25 m, ≥140 m) and that were in the visibility window (target elevation

) of a radar located at the Madrid DSN site.

The SNR of the radar echo was estimated at the time of close approach (TCA), i.e. when the object was at its minimum distance from Earth, using the Equation

1. It was derived from the radar equation for a bistatic configuration, with the assumption that the mean level of receiver noise power is stable and removed as background, and the data frequency resolution is equal to the intrinsic echo bandwidth in the case of the equatorial view of the target [

18].

where

is the transmitted power,

and

the gain of the transmitting and the receiving antennas respectively,

the signal wavelength,

the target radar albedo,

D the target diameter (which is assumed to have a spherical shape),

P target rotational period,

the signal integration time,

k the Boltzmann constant,

the receiver system temperature, and

and

the range from target to transmitter and from target to receiver, respectively. In the specific case of monostatic observations, since the receiving and the transmitting antennas are the same, we have

and

. In our simulations, when a target parameter was unknown we assumed: a typical radar albedo value

[

19], a target spin period

hr if

m and

hr for smaller objects [

9] and, finally, a target diameter

D derived from its absolute magnitude (H) assuming an optical albedo of 0.14 as in the ESA Near-Earth Object Coordination Center (NEOCC) database [

20].

An SNR threshold value of ≥30/track was adopted, as above this SNR threshold the rate of successful detection is close to 100% and accurate astrometry measurements can be performed [

9]. A "readiness threshold" was also applied, to take into account a real-world scenario: targets with a discovery date closer than 5 days to their visibility window were discarded.

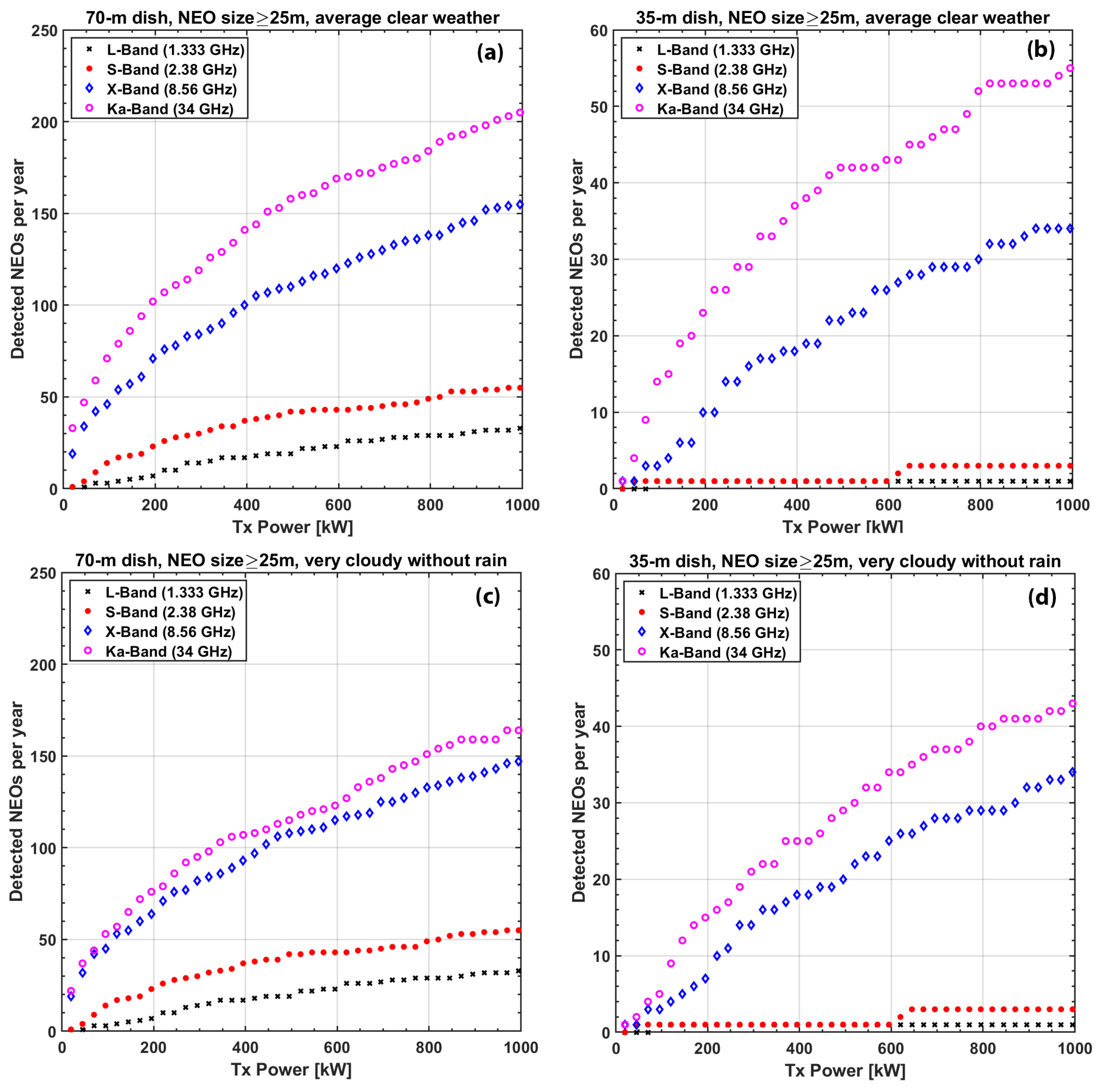

Figure 1 shows the expected yearly detections with SNR≥30 of asteroids larger than 25 m, if employing a 70-m and a 35-m dish both in monostatic radar configuration under weather conditions defined as "average clear weather" (CD=0.25) and "very cloudy without rain" (CD=0.90). The CD value represents the statistics cumulative distribution of the described atmospheric conditions. For example, CD=0.90 means that 90% of the days (on a yearly basis) have atmospheric attenuation and noise temperature equal to or better (i.e. lower) than the ones associated with the descriptive label. It must be stressed that monostatic systems, though more easily manageable, reduce the observation efficiency by about 50%, as transmission and reception take place alternatively. This means that, when longer integration times are needed, multistatic observations are more effective. These results clearly show how, given a certain transmitted power, a transmitter in Ka-band is more productive than lower-frequency ones, even under a usually cloudy sky. Ka-band transmitters roughly need half the power required to reach a given performance in the X band. Conversely, it must be noticed that, at such high power levels, X-band transmitters are presently the most used and better characterized, while Ka-band ones suffer from limitations - such as significant losses in the waveguides, not considered in our simulations. In comparison, the L band and S band choices - though weather-invariant - grant a much lower rate of successful observations, especially for dishes in the 35-m class, as their lower sensitivity further significantly reduces the number of possible detections. A comprehensive description and detailed results of these simulations will be presented in a forthcoming publication.

3. Facilities

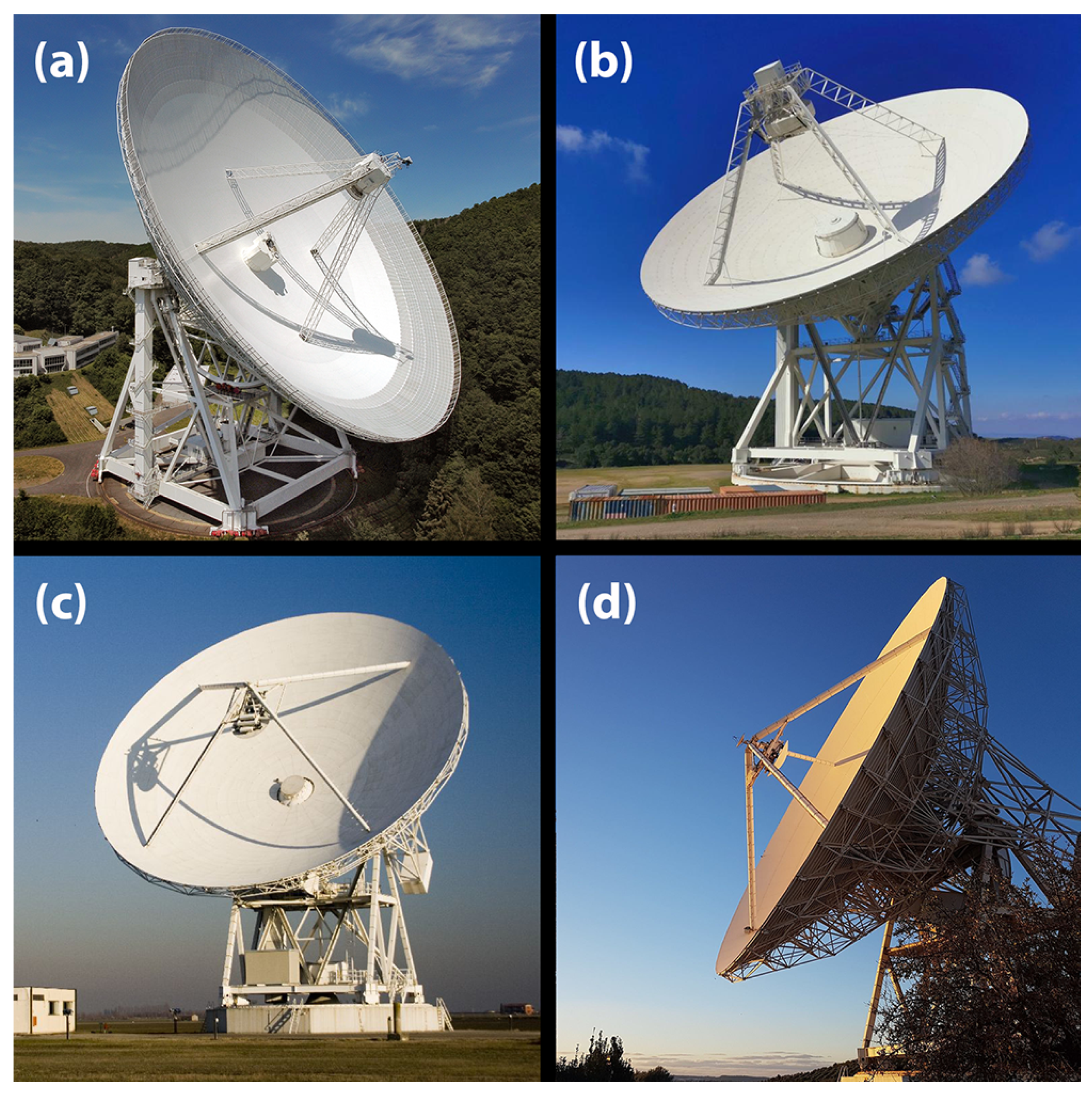

Considering both the availability and the compatibility of receivers with the transmitted frequencies, for the radar observations the Effelsberg, Medicina, Noto and Sardinia Radio Telescope (SRT) radio telescopes (see

Figure 2) were selected as receivers.

The Effelsberg radio telescope is a 100-m dish operated by the Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie (MPIfR) and is located in a valley, for protection against Radio Frequency Interferences (RFIs), near Bad Münstereifel-Effelsberg, Germany. It is one of the two largest fully steerable single-dish radio telescopes in the world and a unique high-frequency radio telescope in Europe. The telescope can be used to observe radio emissions from celestial objects in a wavelength range from 90 cm (300 MHz) down to 3.5 mm (90 GHz).

The Medicina, Noto and SRT radio telescopes are facilities managed by INAF. The one in Medicina (Grueff Radio Telescope) is a 32 m parabolic dish located inside the Medicina radio observatory, 30 km away from Bologna, Italy. The antenna is provided by several receivers in the 1.4-26.5 GHz range and is employed for both interferometric and single-dish observations. In the very near future, its primary mirror will be upgraded to an active surface, allowing it to increase the overall efficiency at higher frequencies and perform observations with stable gain at all elevations. The Noto radio telescope located in the southern part of Sicily Island (Italy) is a 32-m antenna with an active surface, mainly focused on geodynamical, galactic and extragalactic research. Finally, the SRT, located in the Southern part of the island of Sardinia (Italy), is the largest Italian parabolic dish with 64 m of diameter and one of the most advanced radio telescopes in the world. The SRT is co-managed by the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and also named Sardinia Deep Space Antenna (SDSA), equipped with an X-band receiver for deep space and near-Earth activities [

21]. In 2024, all three Italian radio telescopes will be equipped with new tri-band K-Q-W receivers capable of acquiring simultaneously the frequency bands 18–26, 33–50, and 80–116 GHz [

22].

Table 2 summarises the main general features of the receiving antennas. Technical details for the Effelsberg and the INAF antennas can be found in [

23] and [

24], respectively.

Since all those radio telescopes are elements of the Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) network, they are equipped with atomic clocks for synchronization and employ the same Digital Baseband Converter (DBBC) backend for data acquisition [

25]. Having the DBBC installed on multiple antennas offers the advantage of standardizing the observation procedure and generating uniform data formats as output. This facilitates the development and use of common software for data processing.

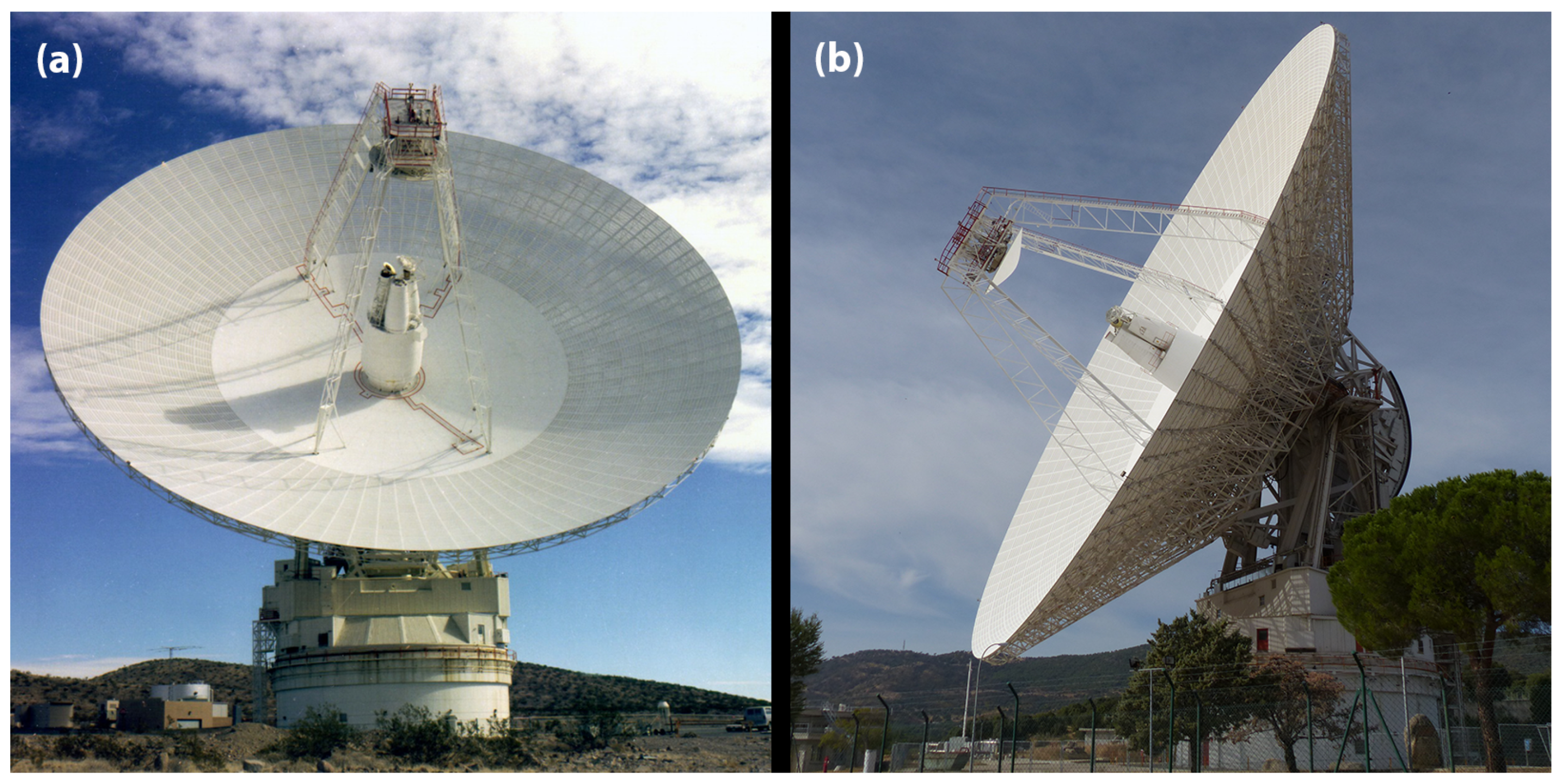

For the transmitting part, after the collapse of Arecibo, the choice fell necessarily on the 70-m DSS-14 and DSS-63 antennas (see

Figure 3) belonging to the DSN.

The DSS-14 is operated by NASA/JPL and is located near Barstow, in the Mojave Desert, California. In addition to the DSN communication system, DSS-14 is also equipped with a planetary radar, capable of transmitting power of 450 kW at 3.5 cm wavelength (X-band). The DSS-14 is currently the main operational ground-based planetary radar, named Goldstone Solar System Radar (GSSR), significantly employed for the observation of NEOs [

26,

27] - it observes NEOs for about 20% of its operational time. Also, the DSS-43 in Canberra has been performing, since 2015, planetary radar activities [

28]. The DSS-63 is located at the Madrid Deep Space Communications Complex owned by NASA/JPL, just outside of Madrid (Spain), in Robledo de Chavela. It currently has installed the standard 20 kW DSN transmitters operating in S and X-band. DSS-63 took part, as a receiver, in the radar observations of Golevka in June 1999 [

29], when Arecibo was the transmitting antenna. The DSS-63 was first employed for transmission in a NEO experiment during our observations of 2005 LW3, making it the first full-European NEO radar campaign after the Evpatoria dish became unavailable.

Table 3.

Main features of the transmitting antennas.

Table 3.

Main features of the transmitting antennas.

| |

DSS-14 (Goldstone)1

|

DSS-63 (Madrid) |

| Longitude |

E |

E |

| Latitude |

N |

N |

| Diameter |

70 m |

70 m |

| Tx bands |

X |

S, X |

| Tx Power |

450 kW |

20 kW |

| Decl. range |

to

|

to

|

| Min. elev. |

|

|

| Max. elev. |

|

|

| Max. speed |

|

|

| Pointing accuracy (rms) |

|

|

4. Definition of observing campaigns: selection of targets and facilities

The definition of the observing campaign started by consulting the list of known close approaches, considering those foreseen in the time frame of interest. The source for this information was the NEODyS database [

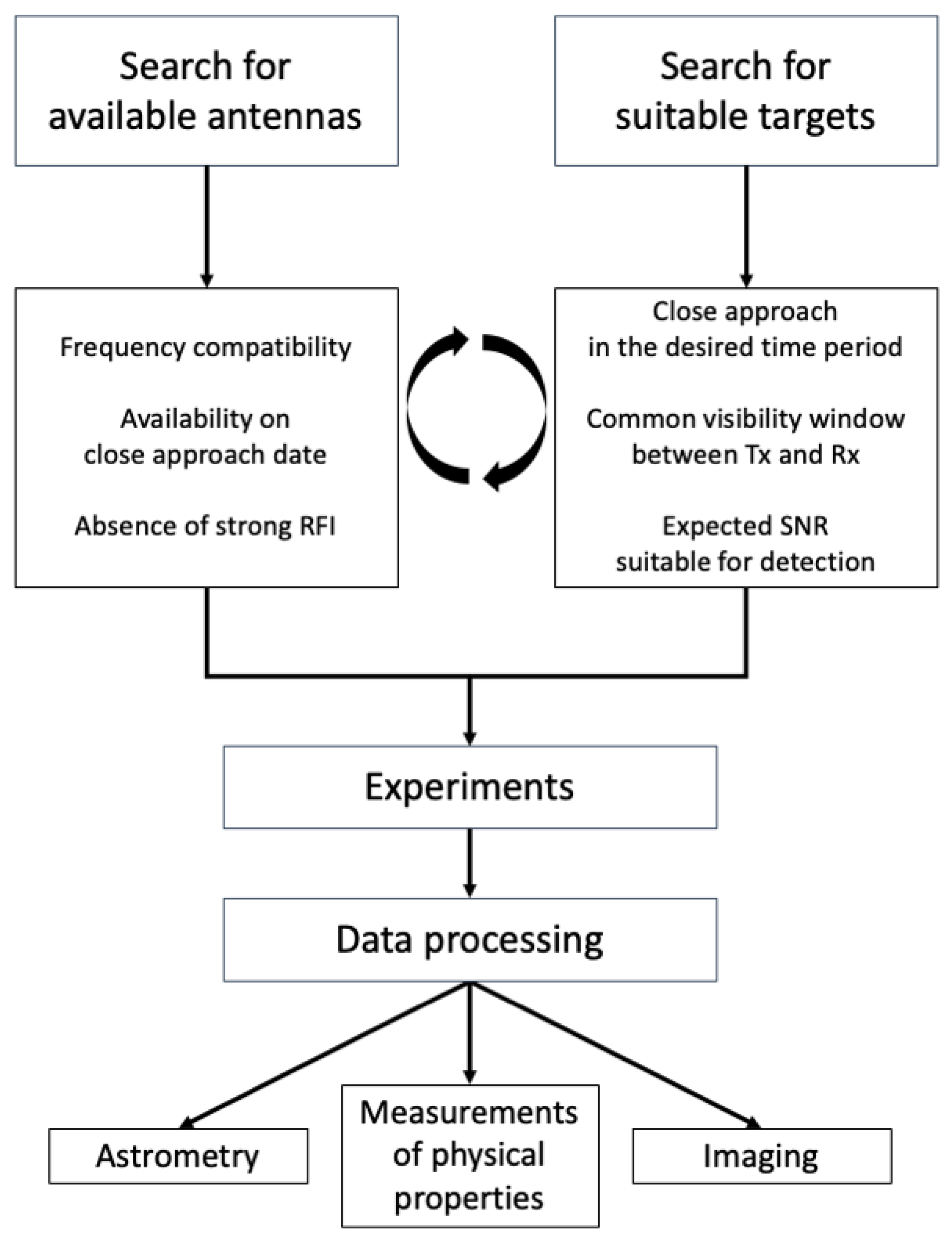

30]. The total number of known NEOs as of 2021 January 1, with a close approach to Earth during the same year at a distance <0.2 au, was 1066. This list has been continuously updated with close approach events of the new objects discovered after 2021 January 1. In parallel, and iteratively, the suitability and availability of the transmitting and receiving antennas were ascertained, to identify the actual exploitable combinations and check the performance they could achieve on the different potential targets. We searched for asteroids for which a common Tx-Rx visibility window was available and whose SNR estimates, obtained using the software tools we developed, were suitable at least for detection. As the actual feasibility of an experiment also depends on the absence of strong RFI in the observed band, it was necessary to verify that no major issues were present at the Rx facility. The overall scheme of the activities, from the initial campaign definition to the results produced after data processing, is presented in

Figure 4.

A comprehensive list of the actually-executed experiments is provided in

Table 4, which also includes observations carried out in 2018, years before the ESA project. It is worth noticing that the Italian radio telescopes have successfully taken part in radar experiments on NEOs since 2001 [

31].

5. Observations

In this section, we describe three radar experiments conducted during and after the ESA project. These experiments were chosen as representative examples of observations carried out using different radar systems and data processing techniques. Data reduction and analysis were performed using software tools we specifically developed in Python and Matlab.

5.1. 2021 AF8

Asteroid 2021 AF8 was discovered by the Mt. Lemmon Survey, part of the Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) Program, on 2021 January 14 [

32]. The object (see

Table 5) is classified as a Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (PHA) by the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center. Before radar observations, neither the size nor rotation period of this target was known. The size was estimated from its absolute magnitude, assuming a mean optical albedo of 0.14 [

20].

Our radar observations devoted to 2021 AF8 were carried out on 2021 May 3. They produced interesting results, thanks to the high sensitivity of the employed system, which involved DSS-14 (Goldstone) for transmission and SRT/SDSA on the receiving side.

Table 6 summarizes the main system parameters.

The DSS-14 scheduled radar observation of 2021 AF8 in the monostatic configuration on 2021 May 3 from 15:05 UT to about 17:05 UT. JPL agreed to allow the recording of the echo signal ("eavesdropping") during their observations and provided details on the transmission configuration timing (start/stop) and type. Since this DSS-14 campaign was designed for a monostatic radar configuration:

The frequency of the transmitted signal was modified in order to compensate for the Doppler variations - due to the known motion of the target (from ephemerides, dynamic compensation) - relative to the transmitting antenna DSS-14 only. A signal received at any other location would show a frequency drift;

The observation needed to be divided into transmission/reception cycles (runs). Each run consisted of signal transmission for a duration close to the round-trip light time (RTT) between the radar and the target, followed by a reception for a similar duration. Additional 5 s, due to the transmission-reception switch time, contributed to the overall run duration [

9].

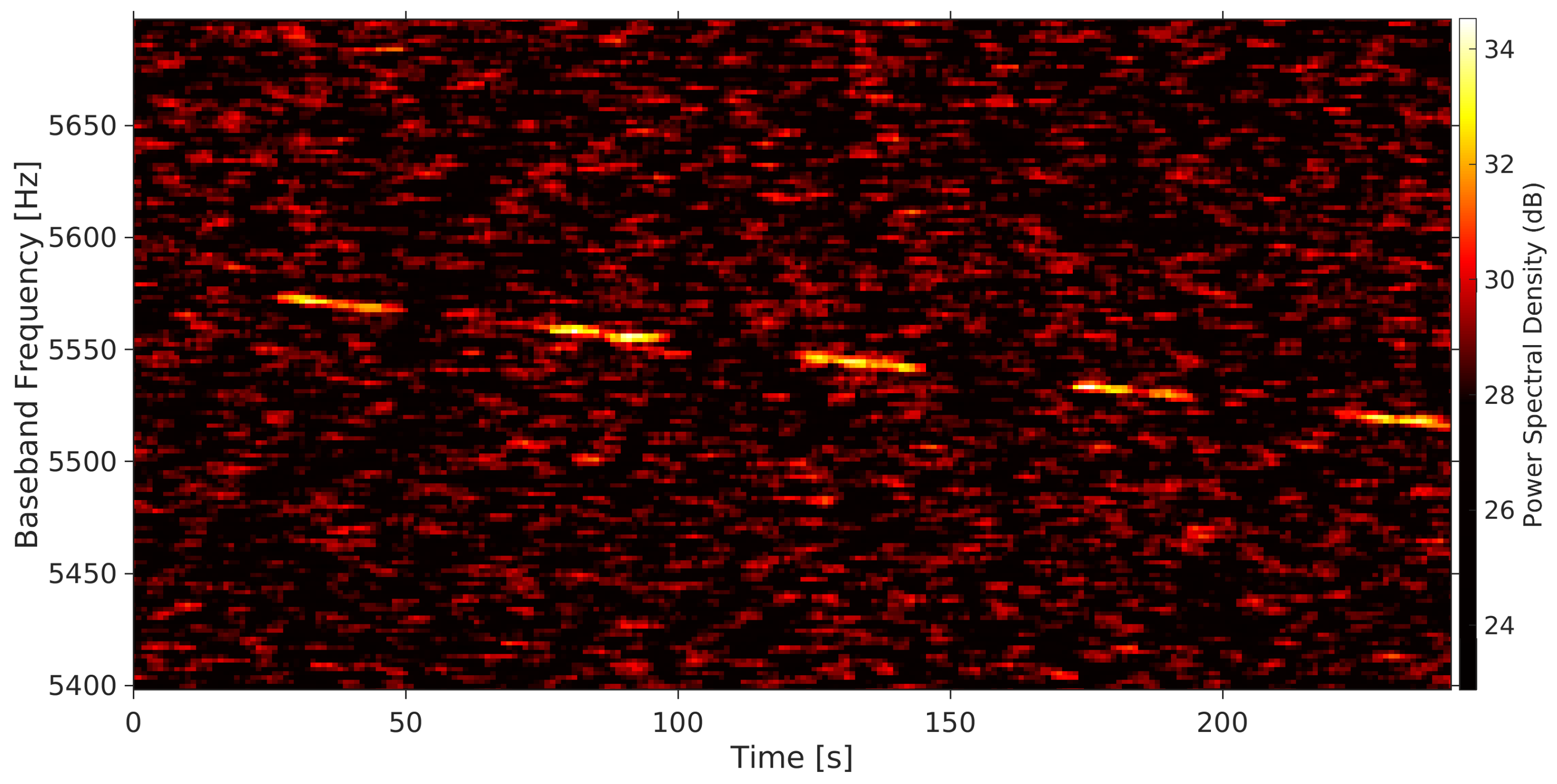

Both residual Doppler frequency drift and transmission On/Off runs of about 28 s duration are evident in the spectrogram of the received signal recorded at SRT/SDSA without Doppler compensation (

Figure 5).

The spectral smearing due to the frequency drift limits the maximum spectral resolution that can be achieved in the Doppler analysis and reduces the SNR. To remove the frequency drift, a Doppler compensation was thus performed by using a phase-stopping technique described in [

33] and [

34]. The frequency variation was modeled using a third-order weighted least mean squares (WLMS) polynomial fit of those spectrum peaks exceeding SNR=10. The weights are the SNR values.

The successful removal of the frequency drift is evident in the spectrogram of the 2021 AF8 signal (

Figure 6) obtained from the time domain data after the Doppler compensation.

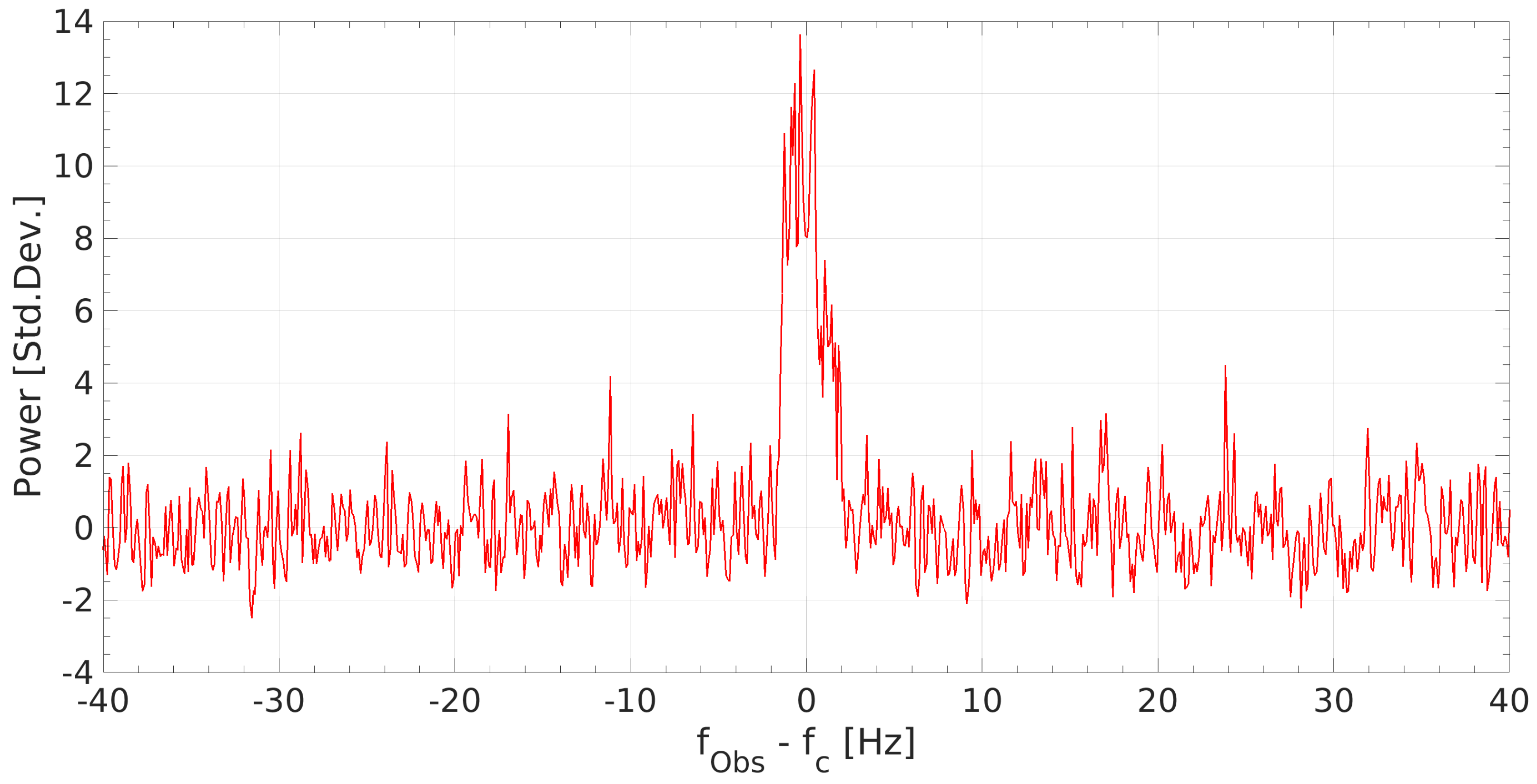

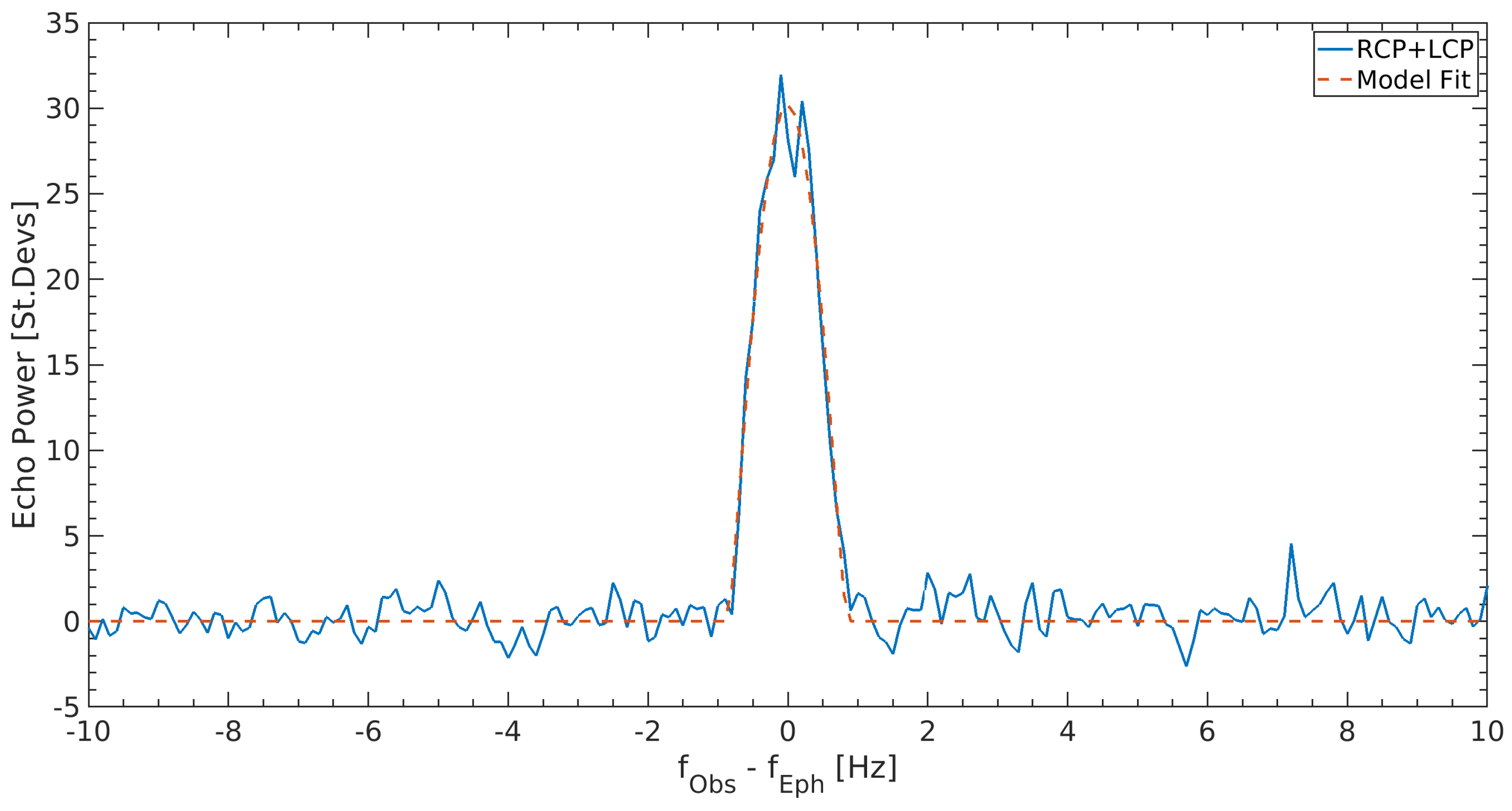

Data corrected for Doppler drift allowed the production of high-resolution (sub-Hz) integrated power spectra (see

Figure 7) because they were no longer affected by frequency smearing. The integration was performed only on the 5 time intervals containing the signal for a total of ∼100 s integration time.

In each integrated spectrum, the mean noise background (baseline) was estimated with a five-grade polynomial fit considering two spectral regions adjacent to the radar echo. This baseline was subtracted from the spectrum and the residual was divided by the noise standard deviation of the baseline. This standard post-processing procedure was employed for all targets.

Figure 7.

High-resolution (0.1 Hz) integrated echo power spectrum of 2021 AF8. Echo power, in units of noise standard deviations, is plotted versus the Doppler frequency (Hz) relative to that of the echo spectral centroid.

Figure 7.

High-resolution (0.1 Hz) integrated echo power spectrum of 2021 AF8. Echo power, in units of noise standard deviations, is plotted versus the Doppler frequency (Hz) relative to that of the echo spectral centroid.

In this plot, the frequencies are expressed as the difference between the received frequency

and that of the echo spectral centroid

Hz, estimated from:

where and are the number of the frequency bin corresponding to the left and right edge of the echo, respectively. is the central frequency of the i-th frequency bin and the echo power in that bin.

The echo of the asteroid is well-resolved in the high-resolution spectra. This allowed us to exploit the inverse of the formula of the echo Doppler broadening [

5] to estimate the asteroid rotation period:

in which P is the target’s rotation period, is the signal wavelength, B is the echo bandwidth, D target’s projected diameter and is the subradar latitude (angle between the radar line-of-sight and the object’s rotational equator).

Measurements of the Doppler broadening yielded an estimate of 2021 AF8 rotation period ∼ 8.5 hours, considering an equatorial view (). The subradar latitude is unknown, therefore under our assumption, the value obtained is an upper limit of the effective target rotation period.

Since the SDSA receiver was capable of acquiring only one circular polarization at a time, it was not possible to perform a polarization analysis of the signal in this experiment.

5.2. (4660) Nereus

Asteroid (4660) Nereus was discovered in February 1982 by E. F. Helin using the 18" Schmidt telescope at Palomar Mountain Observatory [

35]. Some of its physical properties were studied during the close approach in 2002. This object is elongated with an effective diameter of 330 meters and is a member of the optically-bright E spectral class asteroids. Nereus approached within 0.0263 au on 2021 December 11 and it was a strong radar target for several weeks.

Table 7.

Orbital and physical properties of (4660) Nereus.

Table 7.

Orbital and physical properties of (4660) Nereus.

| Target |

(4660) Nereus |

| Epoch (MJD) |

60200.0 |

| Orbit type |

Apollo |

| Eccentricity |

0.359 |

| Inclination (deg) |

1.5 |

| Perihelion distance (au) |

0.953 |

| Aphelion distance (au) |

2.018 |

| Orbital period (days) |

661.1 |

| Close approach distance (au) |

0.026 |

| Close approach date (UT) |

2021-Dec-11 13:50 |

| Earth MOID (au) |

0.00426 |

| Absolute magnitude (H) |

18.7 |

| Diameter (m) |

510 x 330 x 240 |

| Rotation period (hr) |

15.16 |

| Optical albedo |

0.39 |

| Radar albedo |

0.44 |

| Spectral class |

X |

During the period 2021 December 10–15, Goldstone DSS-14 scheduled observation of Nereus in Speckle interferometry mode [

36], in which the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) was the receiving part. In agreement with L. Benner and M. Brozovic at JPL, Medicina joined the experiment in eavesdropping, in the following time intervals:

2021 December 10, 12:44:25 - 13:05:15 UT

2021 December 15, 12:20:00 - 12:40:00 UT

The main system parameters for the observation of Nereus with DSS-14 and Medicina are provided in

Table 8.

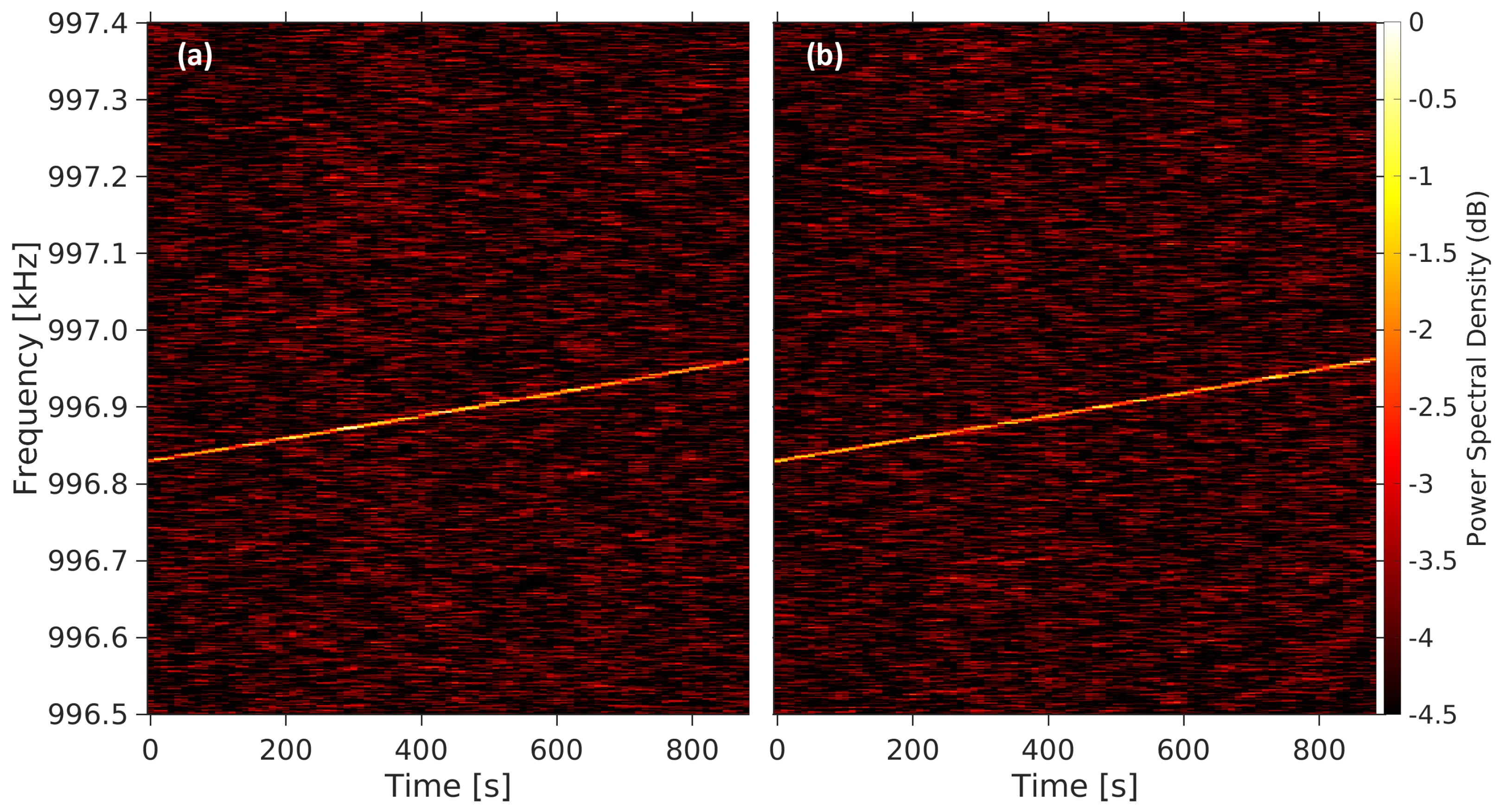

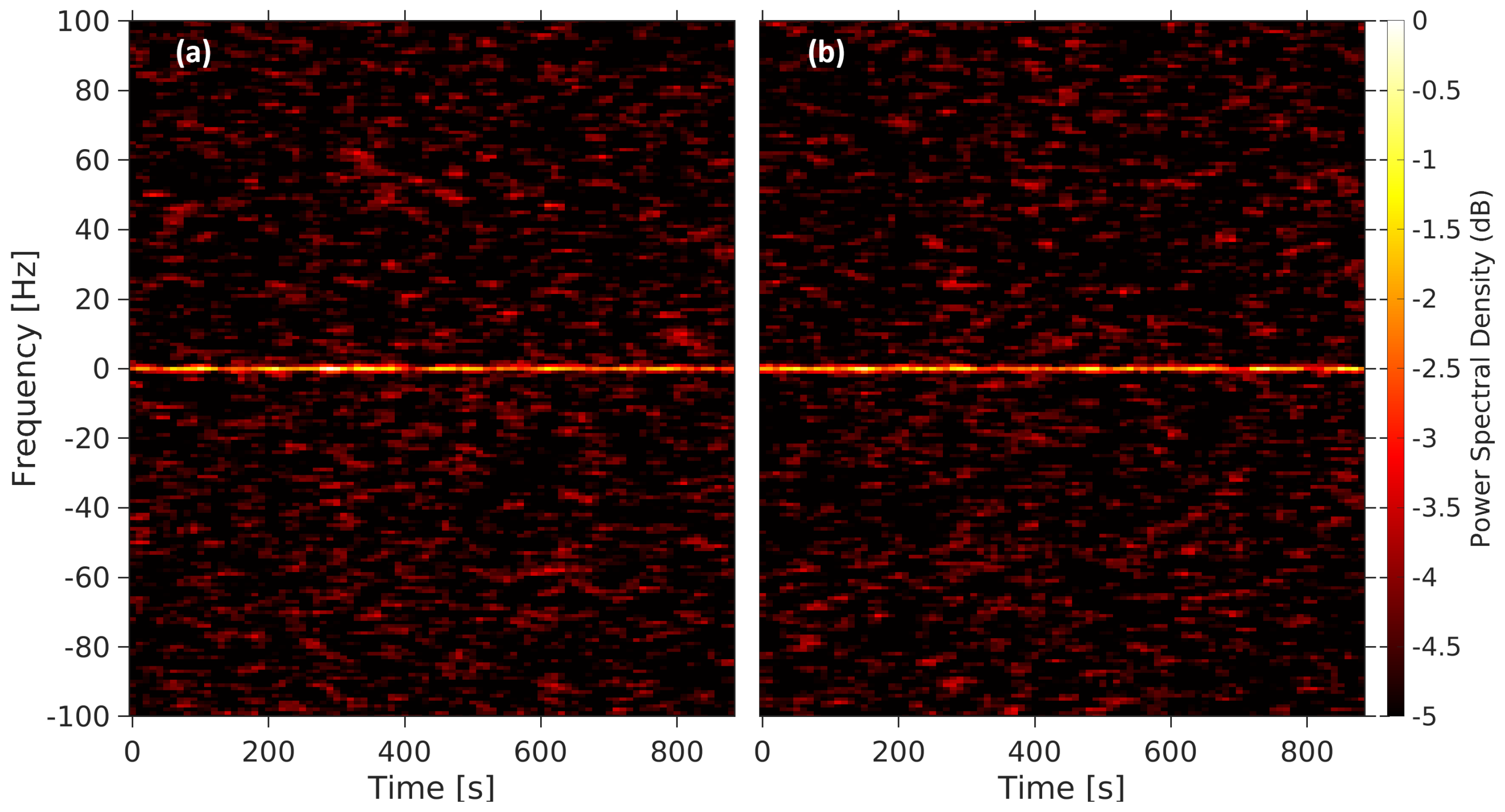

In the radar Speckle experiments, similarly to a standard bistatic observation, CW transmission is employed without interruptions, but the Doppler is compensated for the Earth center - and not for a specific antenna. This leads to a residual Doppler shift in the received signal that we removed in post-processing through the phase-stopping method. Unlike the case of 2021 AF8, here the phase polynomial coefficients were calculated from the ephemeris-based predictions provided by SpaceDyS. Spectrograms of the Nereus echo in both Right Circular Polarization (RCP) and Left Circular Polarization (LCP), obtained from data (recorded on December 10) with and without the Doppler compensation are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, respectively.

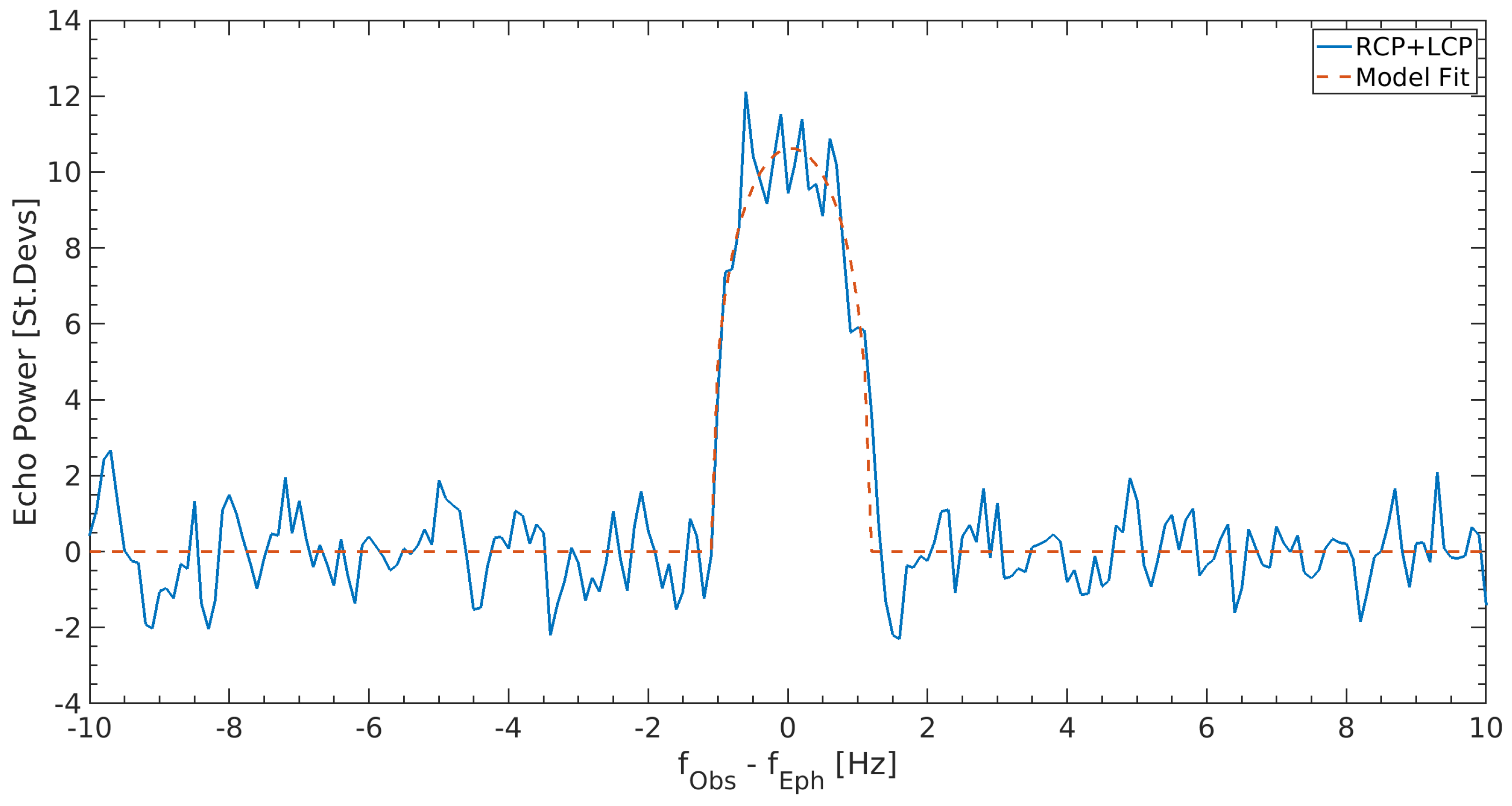

High-resolution power spectra at 0.1 Hz (see

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) allowed us to measure both the frequency at the center of mass (COM) for astrometry computations and the asteroid rotation period. To increase the SNR further, each integrated spectrum is the combination of the power spectra acquired in RCP and LCP. In the estimate of the echo broadening, besides the usual limb-to-limb Doppler bandwidth method, we employed also a multi-parametric fitting with a simple echo profile model [

37]. Both estimation methods gave similar results.

In both days of observation, the measurements give a practically nil difference (within the measurement uncertainties) between the observed COM frequency and that predicted by the ephemeris, testifying to the goodness of both the used ephemeris solutions and the Doppler compensation procedure performed in the time domain data. As concerns the echo bandwidth, measurements yielded: Hz for December 10 and Hz for December 15. The associated uncertainty is calculated as the maximum between the spectral resolution and the standard error in the model fit.

Nereus is an asteroid already well characterized through radar observations carried out at Goldstone and Arecibo during the previous close approach in 2002 [

38]. They measured the rotation period

hr with high accuracy and located approximately the pole direction at

,

ecliptic coordinates, albeit with an uncertainty of

.

From the pole direction coordinates we calculated the subradar latitude

at the time of the observation. Since the rotation period of Nereus is known, we exploit the inverse of Equation

3 to derive the breadth

D of the asteroid’s polar silhouette projected on the plane-of-sky from our instantaneous echo bandwidth measurements. The obtained values of the projected size

D of Nereus at the time of observation are listed in the last column of

Table 9.

These measurements are consistent with the principal axis dimensions of Nereus (510 m x 330 m x 241 m) derived from the delay-Doppler images acquired at Goldstone and Arecibo during the 2002 radar campaigns [

38].

In observations such as those of Nereus, in which the echo is detected in both circular polarizations, it is possible to calculate the circular-polarization ratio

defined as:

where SC is the received echo power in the same polarization sense as transmitted (here RPC) and OC that in the opposite sense (here LCP). The polarization ratio is one of the most important physical observables in the NEO radar technique, as it provides information about the asteroid surface and sub-surface roughness/complexity at the wavelength scale [

39].

A preliminary analysis of our spectra indicates a high value of polarization ratio, typical of the E-class spectral type asteroids such as Nereus, in agreement with the previous measurements [

38]. A quantitative and accurate evaluation of this ratio from our measurements will be possible once the polarization instrumental calibration procedure is implemented.

5.3. 2005 LW3

The asteroid 2005 LW3 was discovered on 2005 June 5 with the 0.5-meter Uppsala Southern Schmidt Telescope (Australia) in the framework of the Siding Spring Survey (SSS) [

40], which is the counterpart in the Southern Hemisphere of the CSS. This asteroid has an absolute magnitude (H) of 21.7 which suggested, before the radar observations, a diameter of about 160 meters (see

Table 10). Nothing else was known about the asteroid’s physical properties.

Thanks to JPL/DSN, we carried out the observation of this object on 2022 November 23, using the DSS-63 antenna in Madrid as the transmitter in a multistatic radar configuration with Effelsberg and Medicina antennas as receivers.

Table 11 shows the main parameters of the radar system employed in our experiment. Despite the limited power available at the DSS-63 facility (20 kW), the possibility to exploit the large Effelsberg radio telescope on the receiving side, together with the Medicina 32-m antenna, permitted us to achieve higher SNR and accuracy in the measurements.

Transmission at a fixed frequency of 7167 MHz was agreed with JPL so that the echoes were received at Medicina in a spectral region free from impacting RFIs. The DSS-63 transmitted the CW signal for approximately 3.17 hr, starting from 15:50 to 19:00 UT on 2022 November 23, with some short interruptions for satellite avoidance.

Note that the signal transmitted by DSS-63 was in RCP, whereas the used Effelsberg’s receiver acquired Linear Vertical Polarization (LVP) and Linear Horizontal Polarization (LHP) signals. Consequently, half of the power of the incoming signal was recorded in each received linear polarization. In this case, the measurement of the polarimetric properties of the radar echo, such as the circular polarization ratio, cannot be directly obtained by analyzing the powers received on the two linear polarization channels. A record of the phase difference between the linear polarizations is needed. We are currently considering the development of these advanced techniques to be integrated into our post-processing software tools.

Similarly to what was done for Nereus, the Doppler compensation of the received signal was performed through the ephemeris-based phase-stopping technique. Both the receiving dishes detected the radar echo from 2005 LW3, well resolving it in the frequency domain. The limb-to-limb broadening of the echo, allowed us to measure a rotation period of about 4.0 hr (assuming an equatorial view), consistent with that obtained from the Goldstone radar observations. Moreover, Goldstone’s delay-Doppler images revealed that 2005 LW3 is a binary system. The primary body is about 400 m in size, much larger than expected from its absolute magnitude, and the satellite, orbiting at a distance of about 4000 m, is elongated in shape with an equatorial diameter between 50 and 100 m [

41].

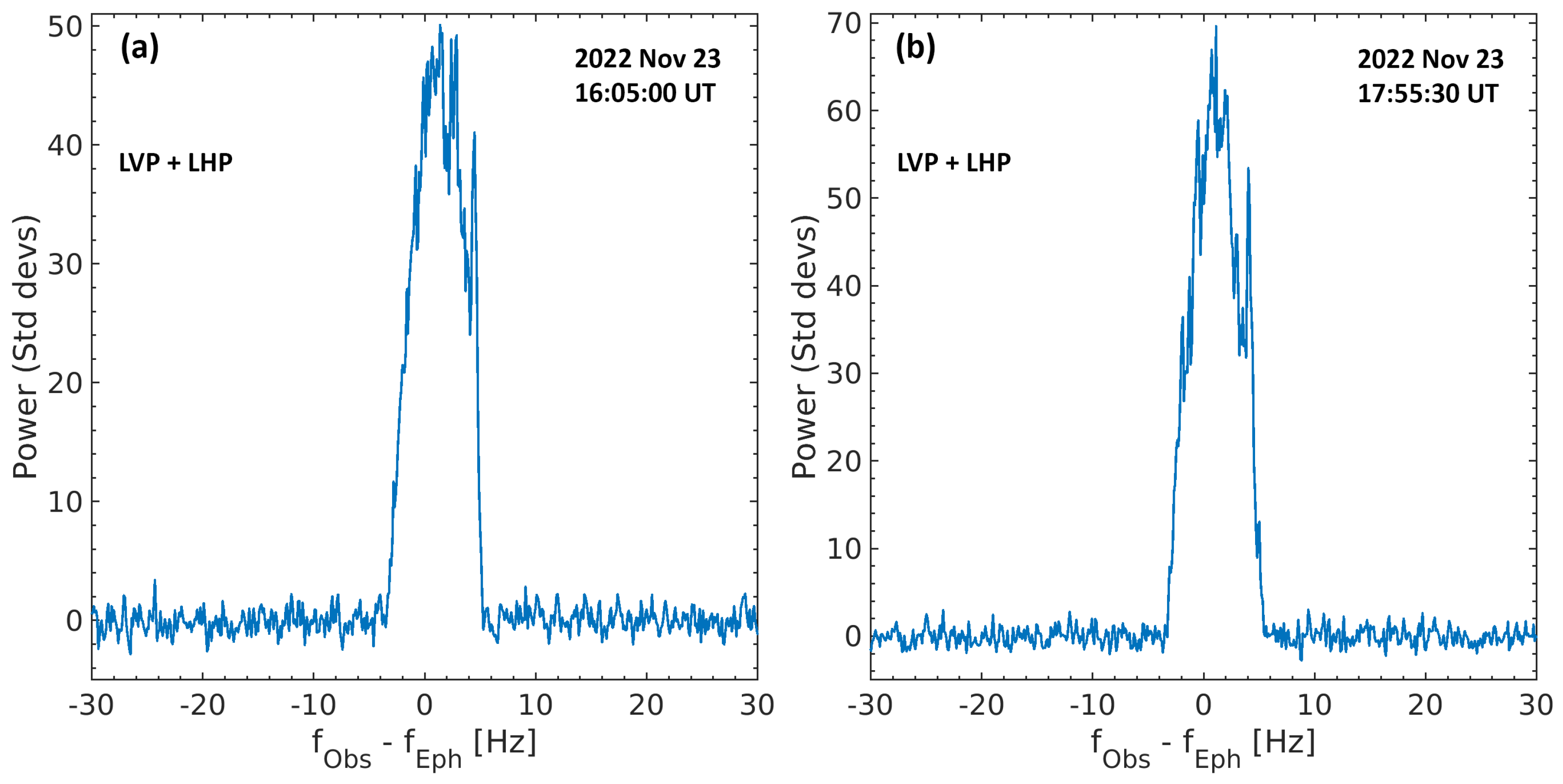

One of the most important achievements of our experiment was the successful detection of the asteroid’s satellite. The high sensitivity of Effelsberg made it possible to obtain high-resolution spectra with high SNR even with a relatively short integration time. They exhibit a narrow peak of the satellite echo superimposed on the broader echo of the primary body. The secondary peak is common to all the spectra, which covered a large portion of the asteroid’s rotation (), confirming that the satellite echo is real and not an artifact due to the internal noise.

As an example, we show in

Figure 12 two high-resolution (0.1 Hz) power spectra of the radar echoes acquired (a) at 16:05 UT and (b) at 17:55 UT, so approximately 1.8 hr apart. This time interval corresponds to half the rotation period of the asteroid, i.e. at

of phase angle difference. Although the two echoes refer to opposite sides of the asteroid, the spike due to the signal reflected by the secondary body is visible in both echo profiles at a frequency of

Hz. To enhance the SNR further, each spectrum is the combination of the power spectra acquired in the two linear polarization states LVP and LHP.

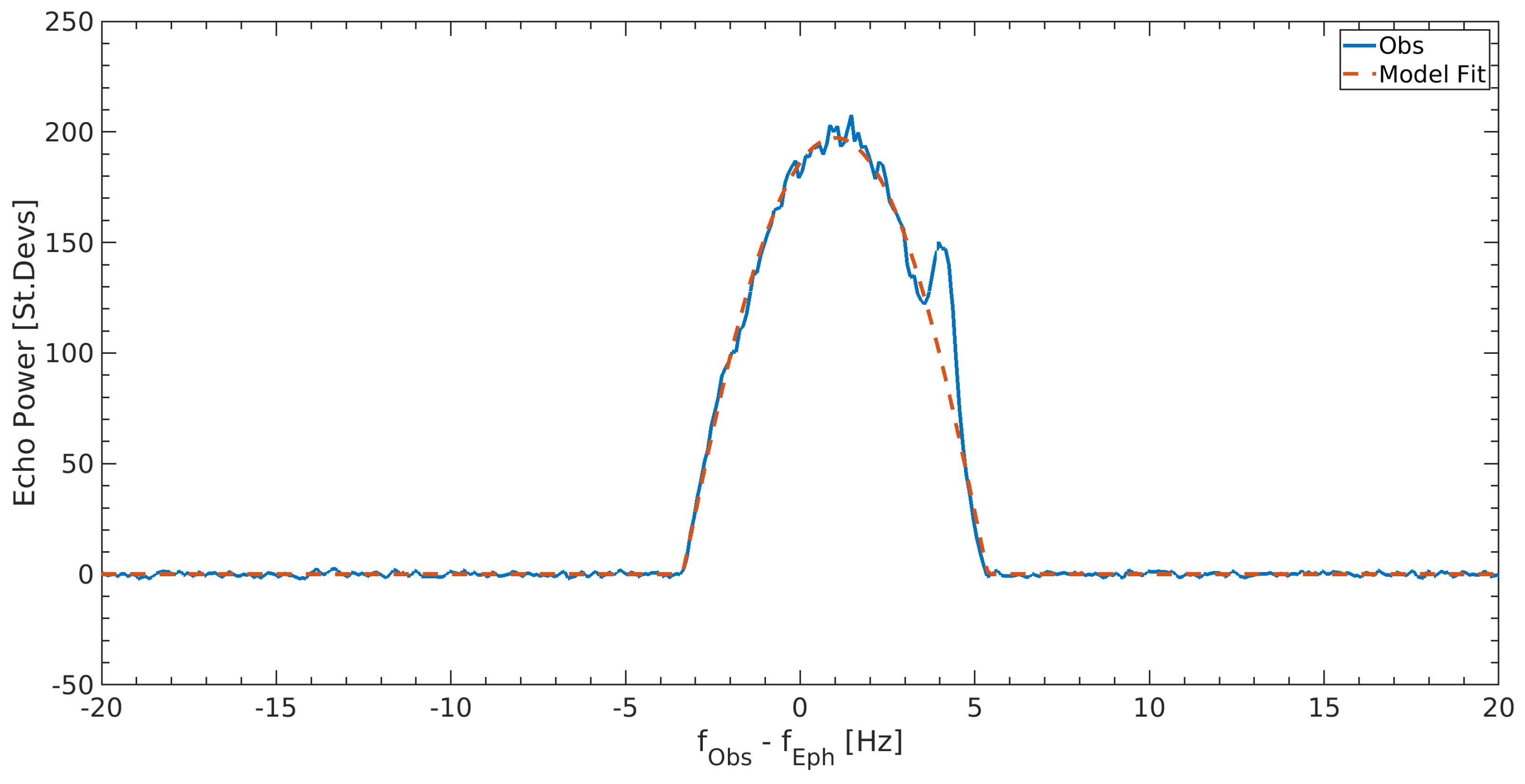

Figure 13 displays the full-track integrated spectrum obtained by summing incoherently all the power spectra acquired during the entire experiment. Such a long integration time almost completely covers the rotation of the asteroid, so many of the spectral features connected to the surface structure of the asteroid are averaged and smeared. Instead, the secondary peak due to the presence of the satellite is still evident. The echo spectrum is superimposed on the echo profile model [

37] calculated through the multi-parametric fitting procedure.

Finally, all the echo profiles showed a displacement of the COM frequency of about Hz with respect to ephemeris prediction. The measurement of the frequency offset is extremely useful from an astrometric point of view, offering information to significantly improve the knowledge of the asteroid orbit.

6. Conclusions

We presented examples of successful radar observations of near-Earth asteroids carried out with European radio telescopes in collaboration with NASA/JPL. They confirm the potential of the European assets with respect to the opportunity of constituting a network for NEO observations. Even if radio telescopes are heavily scheduled with other astrophysical programs, they can be involved in a selected number of radar experiments, especially when high sensitivity and high efficiency are required. These instruments are already equipped with receivers in typically-employed bands, such as the C and X bands, but they are also provided with receivers at higher frequencies (e.g. Ka-band) that, even though they have never been used for planetary radar before, offer interesting opportunities for new solutions. Suitable back-ends are also available. Furthermore, the staff working at these facilities already possesses valuable know-how in radar observations and the development of post-processing software. Even though, at present, no suitable transmitting facility is available in Europe, there is significant interest in the constitution of a European network for NEO radar observations, working in synergy with USA-based facilities so as to increase the observation opportunities and provide additional contributions in the characterization of targets orbits and physical properties. A possible plan for its realization will be investigated in the near future, as monitoring the NEO population is of strategic interest for the European Union in the framework of Space Situational Awareness (SSA) activities [

42] and ESA’s planetary defense activities in their Space Safety program [

43].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P., S.C.; software, A.M., A.T., G.P., M.M.; validation, R.O., S.R.; formal analysis, A.M., A.T., G.P., M.M., R.G.; investigation, A.K., C.B., G.M., G.P., G.V., L.S., M.N.I., M.R., R.G., S.R., T.P., U.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P., R.O., S.R.; writing—review and editing, A.K., A.K.V., A.M., A.P., A.T., C.B., D.K., G.M., G.S., G.V., J.H., L.S., M.M., M.N.I., M.R., R.G., R.M., S.C., T.P., U.B.; visualization, G.P., S.R.; supervision, G.P.; project administration, S.C.; funding acquisition, J.H., G.P., S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

ESA funded this research in the framework of the project "NEO Observation Concepts for Radar Systems" (SSA P3-NEO-XXII). ESA Contract No. 4000130252/20/D/CT.

Acknowledgments

These observations would not have been possible without the collaboration of JPL and MDSCC; We thank in particular Lance Benner, Marina Brozovic, Joseph Lazio, Nereida Rodriguez-Alvarez and Shantanu Naidu. The Sardinia Radio Telescope is funded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR), Italian Space Agency (ASI), and the Autonomous Region of Sardinia (RAS) and is operated as National Facility by the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). The Medicina and Noto radio telescopes are funded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR) and are operated as National Facilities by the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). This work is partly based on data obtained with the 100-m telescope of the Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie at Effelsberg.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goldstein, R.M. Radar observations of Icarus. Science 1968, 162, 903–904. [CrossRef]

- Ostro, S.J. Radar Contributions to Asteroid Astrometry and Dynamics. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 1996, 66, 87–96.

- Chesley, S.R.; Ostro, S.J.; Vokrouhlicky, D.; Capek, D.; Giorgini, J.D.; Nolan, M.C.; Margot, J.L.; Hine, A.A.; Benner, L.A.M.; Chamberlin, A.B. Direct Detection of the Yarkovsky Effect by Radar Ranging to Asteroid 6489 Golevka. Science 2003, 302, 1739–1742. [CrossRef]

- Margot, J.L.; Nolan, M.C.; Benner, L.A.M.; Ostro, S.J.; Jurgens R.F.; Giorgini, J.D.; Slade, M.A.; Campbell D.B. Binary Asteroids in the Near-Earth Object Population. Science 2002, 296, 1445–1448. [CrossRef]

- Ostro, S.J.; Hudson, R.S.; Benner, L.A.M.; Giorgini, J.D.; Magri, C.; Margot, J.L.; Nolan, M.C. Asteroid Radar Astronomy. In Asteroids III; Bottke Jr. W.F., Cellino, A., Paolicchi, P., Binzel, R.P., Eds.; Publishing House: University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 2002; pp. 151–168.

- Benner, L.A.M.; Busch, M.W.; Giorgini, J.D.; Taylor, P.A.; Margot, J.L. Radar Observations of Near-Earth and Main-Belt Asteroids. In Asteroids IV; Michel P., DeMeo F.E., Bottke W.F. Eds.; Publishing House: University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 2015; pp. 165–182.

- Virkki, A.K.; Marshall, S.E.; Venditti, F.C.F.; Zambrano-Marín, L.F.; Hickson, D.C.; McGilvray, A.; Taylor, P.A.; Rivera-Valentín, E.G.; Devogèle, M.; Franco Díaz, E.; Bhiravarasu, S.S.; Aponte Hernández, B.; Rodriguez Sánchez-Vahamonde, C.; Nolan, M.C.; Perillat, P.; Cabrera, I.; González, E.; Padilla, D.; Negrón, V.; Marrero, J.; Lebrón, J.; Bagué, A.; Jiménez, F.; López-Oquendo, A.; Repp, D.; McGlasson, R.A.; Presler-Marshall, B.; Howell, E.S.; Margot, J.L.; Prabhu Desai, S. Arecibo Planetary Radar Observations of Near-Earth Asteroids: 2017 December–2019 December. PSJ 2022, 3, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, S.; Molyneux, B.; Stevens, J.B.; Baines, G.; Benson, C.; Abu-Shaban, Z.; Giorgini, J.D.; Benner, L.A.M.; Naidu, S.P.; Phillips, C.J.; Edwards, P.G.; Kruzins, E.; Stacy, N.J.S.; Slade, M.A.; Reynolds, J.E.; Lazio, J. Bistatic radar observations of near-earth asteroid (163899) 2003 SD220 from the southern hemisphere. Icarus 2021, 357, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Naidu, S.P.; Benner, L.A.M.; Margot, J.L.; Busch, M.W.; Taylor, P.A. Capabilities of Earth-based radar facilities for near-Earth asteroid observations. AJ 2016, 152, 1–9.

- de Pater, I.; Palmer, P.; Mitchell, D.L.; Ostro, S.J.; Yeomans, D. Radar Aperture Synthesis Observations of Asteroids. Icarus 1994, 152, 489–502.

- Plemel, R.A.; Warhaut, M.; Martin, R. ESA Station Tracking Network (ESTRACK) Augmented by the Second Deep Space Antenna at Cebreros/Spain. In Proceeding of SpaceOps 2006 Conference, Rome, Italy, 19-23 June 2006. Available online: https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/epdf/10.2514/6.2006-5788 (accessed on 30 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Leushacke, L. FGAN Contribution to the MIR Deorbiting Campaign 2001. In Proceeding of The International Workshop ’Mir Deorbit’, ESOC, Darmstadt, Germany, 14 May 2001. Available online: https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/2002ESASP.498...67L (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Slobin, S. 70-m Subnet Telecommunications Interfaces. DSN No. 810-005, 101, Rev. E, NASA/JPL, California Institute of Technology, 18 September 13. Available online: https://deepspace.jpl.nasa.gov/dsndocs/810-005/101/101E.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- The Mathworks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, MATLAB version: 9.11.0 (R2021b)Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/ (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Wilkinson, S.R.; Hansen, C.; Alexia, B.; Shamee, B.; Lloyd, B.; Beasley, A.; Brisken, W.; Paganelli, F.; Watts, G.; O’Neil, K.; Courtney, P. A planetary radar system for detection and high-resolution imaging of nearby celestial bodies. Microw. J. 2022, 65, 1–7.

- Shambayati, S. Atmosphere Attenuation and Noise Temperature at Microwave Frequencies. Chapter 6 in Low-Noise Systems in the Deep Space Network; Macgregor, S.R., Eds.; Publishing House: John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2008; pp. 255–281.

- Kantak, A.V.; Slobin, S.D. Atmosphere Attenuation and Noise Temperature Models at DSN Antenna Locations for 1–45 GHz, JPL Technical Report 09-14, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, March 2009.

- Ostro, S.J. Planetary Radar Astronomy. Rev.Mod.Phys. 1993, 65, 1235–1279. [CrossRef]

- Ostro, S.J. Radar observations of asteroids and comets. PASP 1985, 97, 877–884. [CrossRef]

- ESA NEOCC Database. Available online: https://neo.ssa.esa.int/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Valente, G.; Iacolina, M.N.; Ghiani, R.; Saba, A.; Serra, G.; Urru, E.; Montisci, G.; Mulas, S.; Asmar, S.W.; Pham, T.T.; De Vincente, J.; Viviano, S. The Sardinia Space Communication Asset: Performance of the Sardinia Deep Space Antenna X-Band Downlink Capability. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64525-64534.

- Govoni, F; Bolli, P.; Buffa, F.; Caito, L.; Carretti, E.; Comoretto, G.; Fierro, D.; Melis, A.; Murgia, M.; Navarrini, A.; Orfei, A.; Orlato, A.; Pisanu, T.; Poppi, S.; Possenti, A.; Attoli, A.; Becciani, U.; Belli, C.; Carboni, G.; Caria, M.T.; Cattani, A.; Concu, R.; Cresci, L.; Fara, A.; Fiocchi, F.; Gaudiomonte, F.; Ladu, A.; Maccaferri, A.; Mariotti, S.; Marongiu, P.; Migoni, C.; Molinari, E.; Morsiani, M.; Nesti, R.; Olmi, L.; Porceddu, I.; Righini, S.; Ortu, P.; Palmas, S.; Pili, M.; Poddighe, A.; Poloni, M.; Roda, J.; Scalambra, A.; Schirru, L.; Serra, G.; Smareglia, R.; Vargiu, G.P.; Vitello, F. The high-frequency upgrade of the Sardinia Radio Telescope. In Proceeding of 2021 XXXIVth General Assembly and Scientific Symposium of the International Union of Radio Science (URSI GASS), Rome, Italy, 28 August 2021 - 04 September 2021. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9560570 (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Effelsberg Radio Telescope User Guide.Available online: https://eff100mwiki.mpifr-bonn.mpg.de/doku.php?id=information_for_astronomers:user_guide:index (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- INAF Radio Telescopes User Guide.Available online: https://www.radiotelescopes.inaf.it/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Tuccari, G.; Bezrukovs, V.; Nechaeva, M. Digital Base Band Converter As Radar VLBI Backend. Latv.J.Phys.Tech.Sci. 2012, 49, 18–29. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Alvarez, N.; Jao, J.S.; Lee, C.G.; Slade, M.A.; Lazio, J.; Oudrhiri, K.; Andrews, K.S.; Snedeker, L.G.; Liou, R.R.; Stanchfield, K.A. The Improved Capabilities of the Goldstone Solar System Radar Observatory. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Alvarez, N.; Slade, M.A.; Jao, J.; Lee, C., Oudrhiri, K., Lazio, J. Goldstone Solar System Radar (GSSR) Learning Manual; Publisher: NASA/JPL, California Institute of Technology, October 2019. Available online: https://deepspace.jpl.nasa.gov/files/GSSR_learning_manual.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Benson, G.; Reynolds, J.; Stacy, N.J.S.; Benner, L.A.M.; Edwards, P.G.; Baines, G.; Boyce, R.; Giorgini, J.D.; Jao, J.S.; Martinez, G.; Slade, M.A.; Teitelbaum, L.P.; Anabtawi, A.; Kahan, D.; Oudrhiri, K.; Philips, C.J.; Stevens, J.B.; Kruzins, E.; Lazio, T.J.W. First Detection of Two Near-Earth Asteroids With a SouthernHemisphere Planetary Radar System. Radio Sci. 2017, 52, 1344–1351.

- Margot, J.L. A Data-Taking System for Planetary Radar Applications. J. Astron. Instrum. 2021, 10, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- NEODyS Database. Available online: https://newton.spacedys.com/neodys/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Di Martino, M.; Montenugnoli, S.; Cevolani, G.; Ostro, S.J.; Zaitsev, A.; Righini, S.; Saba, L.; Poppi, S.; Delbò, M.; Orlati, A.; Maccaferri, G.; Bortolotti, C.; Gavrik, A.; Gavrik, Y. Results of the first Italian planetary radar experiment. Planet. Space Sci. 2004, 52, 325–330.

- Tomatic, A.U., IAU Minor Planet Electronic Circular No. 2021-B127, 2021 January 24. Available online: https://www.minorplanetcenter.net/mpec/K21/K21BC7.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Molera Calvès, G. Radio spectroscopy and space science with VLBI radio telescopes for Solar System research. Ph.D. Thesis, Aalto University, Sweden, 27 April 2012, Available online: http://lib.tkk.fi/Diss/2012/isbn9789526045818.

- Molera Calvès, G.; Pogrebenko, S.V.; Cimò, G.; Duev, D.A.; Bocanegra-Bahamòn, T.M.; Wagner, J.F.; Kallunki, J.; de Vincente, P.; Kronschnabl, G.; Haas, R.; Quick, J.; Maccaferri, G.; Colucci, G.; Wang, W.H.; Yang, W.J.; Hao, L.F. Observations and analysis of phase scintillation of spacecraft signal on the interplanetary plasma. A&A 2014, 564, 1–7.

- Marsden, G.B., IAU Circular No. 3675, 1982 March 5. Available online: http://www.cbat.eps.harvard.edu/iauc/03600/03675.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Busch, M.W.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Brisken, W; Ostro, S.J.; Benner, L.A.M.; Giorgini J.D.; Nolan, M.C. Determining asteroid spin states using radar speckles. Icarus 2010, 209, 535–541.

- Jurgens, R.F.; Goldstein, R.M. Radar observations at 3.5 and 12.6 cm Wavelength of Asteroid 433 Eros. Icarus 1976, 28, 1–15.

- Brozovic, M.; Ostro, S.J.; Benner, L.A.M.; Giorgini, J.D.; Jurgens, R.F.; Rosea, R.; Nolan, M.C.; Hineb, A.A.; Magri, C.; Scheeres, D.J.; Margot, J.L. Radar observations and a physical model of Asteroid 4660 Nereus, a prime space mission target. Icarus 2009, 201, 153–166.

- Virkki, A.; Muinonen, K. Radar scattering by planetary surfaces modeled with laboratory-characterized particles. Icarus 2016, 269, 38–49.

- Spahr, T.B., IAU Minor Planet Electronic Circular No. 2005-L19, 2005 June 6.Available online: https://minorplanetcenter.net/mpec/K05/K05L19.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Green, D.W.E., IAU Circular No. 5198, 2022 December 10.Available online: http://www.cbat.eps.harvard.edu/iau/cbet/005100/CBET005198.txt (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Polkowska, M. Space Situational Awareness (SSA) for Providing Safety and Security in Outer Space: Implementation Challenges for Europe. Space Policy 2020, 51.

- ESA - Space Safety. Available online: https://www.esa.int/Space_Safety (accessed on 30 October 2023).

Figure 1.

Number of expected yearly detections of NEOs greater than 25 m in size by a monostatic radar system as a function of frequency and power if employing (a) 70-m antenna in average clear weather, (b) 35-m antenna in average clear weather, (c) 70-m antenna in very cloudy weather without rain, and (d) 35-m antenna in very cloudy weather without rain.

Figure 1.

Number of expected yearly detections of NEOs greater than 25 m in size by a monostatic radar system as a function of frequency and power if employing (a) 70-m antenna in average clear weather, (b) 35-m antenna in average clear weather, (c) 70-m antenna in very cloudy weather without rain, and (d) 35-m antenna in very cloudy weather without rain.

Figure 2.

The radio telescopes used as receivers in the NEO radar experiments: (a) Effelsberg, (b) SRT/SDSA, (c) Medicina and (d) Noto.

Figure 2.

The radio telescopes used as receivers in the NEO radar experiments: (a) Effelsberg, (b) SRT/SDSA, (c) Medicina and (d) Noto.

Figure 3.

The Deep Space Network antennas used as transmitters in the NEO radar experiments: (a) DSS-14 (Goldstone) and (b) DSS-63 (Madrid).

Figure 3.

The Deep Space Network antennas used as transmitters in the NEO radar experiments: (a) DSS-14 (Goldstone) and (b) DSS-63 (Madrid).

Figure 4.

Diagram illustrating the phases of the overall activity.

Figure 4.

Diagram illustrating the phases of the overall activity.

Figure 5.

Spectrogram with 1.9 Hz resolution, 5 s integration time - with an overlap fraction of 0.75, zoomed on the baseband frequency interval around the echo. The start frequency of the baseband is 8559.9765525 MHz. Color scale represents the normalized power spectral density in dB.

Figure 5.

Spectrogram with 1.9 Hz resolution, 5 s integration time - with an overlap fraction of 0.75, zoomed on the baseband frequency interval around the echo. The start frequency of the baseband is 8559.9765525 MHz. Color scale represents the normalized power spectral density in dB.

Figure 6.

Spectrogram with 1.9 Hz resolution, 5 s integration time - with an overlap fraction of 0.75, zoomed on the baseband frequency interval around the echo, showing the Doppler-corrected data. The start frequency of the baseband is 8559.9765525 MHz. Color scale represents the normalized power spectral density in dB.

Figure 6.

Spectrogram with 1.9 Hz resolution, 5 s integration time - with an overlap fraction of 0.75, zoomed on the baseband frequency interval around the echo, showing the Doppler-corrected data. The start frequency of the baseband is 8559.9765525 MHz. Color scale represents the normalized power spectral density in dB.

Figure 8.

Spectrograms of Nereus echo acquired in (a) RCP and (b) LCP, without Doppler compensation. The color scale is the normalized power spectral density in dB. Spectral resolution: 1 Hz, integration time: 30 s - with an overlap fraction of 0.75.

Figure 8.

Spectrograms of Nereus echo acquired in (a) RCP and (b) LCP, without Doppler compensation. The color scale is the normalized power spectral density in dB. Spectral resolution: 1 Hz, integration time: 30 s - with an overlap fraction of 0.75.

Figure 9.

Spectrograms of Nereus echo acquired in (a) RCP and (b) LCP, with Doppler corrected frequency. The color scale is the normalized power spectral density in dB. Spectral resolution: 1 Hz, integration time: 30 s - with an overlap fraction of 0.75.

Figure 9.

Spectrograms of Nereus echo acquired in (a) RCP and (b) LCP, with Doppler corrected frequency. The color scale is the normalized power spectral density in dB. Spectral resolution: 1 Hz, integration time: 30 s - with an overlap fraction of 0.75.

Figure 10.

Integrated power spectrum at 0.1 Hz frequency resolution of the Nereus radar echo recorded at Medicina on 2021 December 10 (blue curve). Echo power is plotted in standard deviations of the background noise versus the estimated frequency of the echo from the asteroid’s COM. The echo model fit is superimposed on the spectrum (dashed red curve).

Figure 10.

Integrated power spectrum at 0.1 Hz frequency resolution of the Nereus radar echo recorded at Medicina on 2021 December 10 (blue curve). Echo power is plotted in standard deviations of the background noise versus the estimated frequency of the echo from the asteroid’s COM. The echo model fit is superimposed on the spectrum (dashed red curve).

Figure 11.

Integrated power spectrum at 0.1 Hz frequency resolution of the Nereus radar echo recorded at Medicina on 2021 December 15 (blue curve). Echo power is plotted in standard deviations of the background noise versus the estimated frequency of the echo from the asteroid’s COM. The echo model fit is superimposed on the spectrum (dashed red curve).

Figure 11.

Integrated power spectrum at 0.1 Hz frequency resolution of the Nereus radar echo recorded at Medicina on 2021 December 15 (blue curve). Echo power is plotted in standard deviations of the background noise versus the estimated frequency of the echo from the asteroid’s COM. The echo model fit is superimposed on the spectrum (dashed red curve).

Figure 12.

Integrated power spectra at 0.1 Hz frequency resolution, 10 min integration time, of 2005 LW3 echo recorded at Effelsberg on 2022 Nov 23 at (a) 16:05:00 UT and (b) 18:55:30 UT. Echo power on the vertical axis is plotted in standard deviations of the background noise. The Doppler frequency on the horizontal axis is relative to the ephemeris-based estimate frequency of echo from the asteroid’s COM. The spike at Hz in both spectra is the echo from the satellite.

Figure 12.

Integrated power spectra at 0.1 Hz frequency resolution, 10 min integration time, of 2005 LW3 echo recorded at Effelsberg on 2022 Nov 23 at (a) 16:05:00 UT and (b) 18:55:30 UT. Echo power on the vertical axis is plotted in standard deviations of the background noise. The Doppler frequency on the horizontal axis is relative to the ephemeris-based estimate frequency of echo from the asteroid’s COM. The spike at Hz in both spectra is the echo from the satellite.

Figure 13.

Full-track integrated echo power spectrum of 2005 LW3 (blue curve) at 0.1 Hz frequency resolution. The spectrum is the combination of both polarizations LVP and LHP, with a hr integration time for each of them. Echo power is plotted in standard deviations of the background noise versus the estimated frequency of the echo from the asteroid’s COM. The echo model fit is superimposed on the spectrum (dashed red curve).

Figure 13.

Full-track integrated echo power spectrum of 2005 LW3 (blue curve) at 0.1 Hz frequency resolution. The spectrum is the combination of both polarizations LVP and LHP, with a hr integration time for each of them. Echo power is plotted in standard deviations of the background noise versus the estimated frequency of the echo from the asteroid’s COM. The echo model fit is superimposed on the spectrum (dashed red curve).

Table 1.

Key parameters for simulated sensors.

Table 1.

Key parameters for simulated sensors.

| Tx band and frequency |

Antenna diameter |

|

Gain |

| (GHz) |

(m) |

(K) |

(dBi) |

| L (1.333) |

35 |

26.68 |

53.08 |

| S (2.38) |

35 |

18.27 |

57.90 |

| X (8.56) |

35 |

11.46 |

68.00 |

| Ka (34.0) |

35 |

19.57 |

79.77 |

| L (1.333) |

70 |

26.68 |

59.10 |

| S (2.38) |

70 |

18.27 |

63.92 |

| X (8.56) |

70 |

11.46 |

74.02 |

| Ka (34.0) |

70 |

19.57 |

85.79 |

Table 2.

Main features of the receiving antennas.

Table 2.

Main features of the receiving antennas.

| |

Effelsberg |

SRT/SDSA |

Medicina |

Noto |

| Longitude |

E |

E |

E |

E |

| Latitude |

N |

N |

N |

N |

| Diameter |

100 m |

64 m |

32 m |

32 m |

| Rx bands |

L,C,X,Ku,K,Ka |

P,L,C,X,K |

L,S,C,X,K |

L,S,C,X,K |

| Decl. range |

to

|

to

|

to

|

to

|

| Min. elev. |

|

|

|

|

| Max. elev. |

|

|

|

|

| Max. speed |

Az.; El. |

Az.; El. |

Az.; El. |

Az.; El. |

| Pointing accuracy (rms) |

|

|

|

|

| Active mirror |

yes |

yes |

imminent |

yes |

Table 4.

List of the executed experiments. MC=Medicina, NT=Noto, SDSA=Sardinia Deep Space Antenna, EF=Effelsberg

Table 4.

List of the executed experiments. MC=Medicina, NT=Noto, SDSA=Sardinia Deep Space Antenna, EF=Effelsberg

| Date |

Target |

Tx |

Rx |

Result |

| 17, 20, 22.12.2018 |

2003 SD220 |

DSS-14 |

SDSA, MC |

Detected MC |

| 03.05.2021 |

2021 AF8 |

DSS-14 |

SDSA, MC |

Detected SDSA |

| 23.08.2021 |

2016 AJ193 |

DSS-14 |

MC |

Detected |

| 10, 15.12.2021 |

(4660) Nereus |

DSS-14 |

MC |

Detected |

| 28.04.2022 |

2008 AG33 |

DSS-63 |

EF |

Not detected |

| 25.05.2022 |

1989 JA |

DSS-63 |

EF |

Not detected |

| 23.11.2022 |

2005 LW3 |

DSS-63 |

MC, EF |

Detected at both |

| 15.12.2022 |

2015 RN35 |

DSS-63 |

MC, NT, EF |

Not detected |

| 27.12.2022 |

2010 XC15 |

DSS-63 |

MC |

Detected |

Table 5.

Orbital and physical properties of 2021 AF8, as they were known before radar observations.

Table 5.

Orbital and physical properties of 2021 AF8, as they were known before radar observations.

| Target |

2021 AF8 |

| Epoch (MJD) |

60200.0 |

| Orbit type |

Apollo |

| Eccentricity |

0.517 |

| Inclination (deg) |

9.7 |

| Perihelion distance (au) |

0.973 |

| Aphelion distance (au) |

3.058 |

| Orbital period (days) |

1045.3 |

| Close approach distance (au) |

0.022 |

| Close approach date (UT) |

2021-May-04 12:12 |

| Earth MOID (au) |

0.02783 |

| Absolute magnitude (H) |

20.2 |

| Diameter (m) |

∼300 |

| Rotation period (hr) |

unknown |

| Optical albedo |

unknown |

| Radar albedo |

unknown |

| Spectral class |

unknown |

Table 6.

System parameters for the observation of 2021 AF8.

Table 6.

System parameters for the observation of 2021 AF8.

| |

Transmitter |

Receiver |

| |

DSS-14 |

SRT/SDSA |

| Diameter |

70 m |

64 m |

| Aperture efficiency |

0.64 |

0.54 |

| Tx Frequency |

8560 MHz |

- |

| Tx Power |

450 kW |

- |

| Tx Waveform |

CW |

- |

| System Temperature |

- |

42 K |

| Polarization |

RCP |

LCP |

Table 8.

System parameters for the observation of (4660) Nereus.

Table 8.

System parameters for the observation of (4660) Nereus.

| |

Transmitter |

Receiver |

| |

DSS-14 |

Medicina |

| Diameter |

70 m |

32 m |

| Aperture efficiency |

0.64 |

0.48 |

| Tx Frequency |

8560 MHz |

- |

| Tx Power |

450 kW |

- |

| Tx Waveform |

CW |

- |

| System Temperature |

- |

38 K |

| Polarization |

RCP |

RCP, LCP |

Table 9.

Measurements of the Nereus projected diameter.

Table 9.

Measurements of the Nereus projected diameter.

| Observation Date |

|

B |

D |

| (UT) |

(deg) |

(Hz) |

(m) |

| 2021 December 10.538 |

|

|

|

| 2021 December 15.521 |

|

|

|

Table 10.

Orbital and physical properties of 2005 LW3, as they were known pre-radar observations.

Table 10.

Orbital and physical properties of 2005 LW3, as they were known pre-radar observations.

| Target |

2005 LW3 |

| Epoch (MJD) |

60200.0 |

| Orbit type |

Apollo |

| Eccentricity |

0.464 |

| Inclination (deg) |

6.0 |

| Perihelion distance (au) |

0.772 |

| Aphelion distance (au) |

2.106 |

| Orbital period (days) |

630.3 |

| Close approach distance (au) |

0.0076 |

| Close approach date (UT) |

2022-Nov-23 10:05 |

| Earth MOID (au) |

0.00134 |

| Absolute magnitude (H) |

21.6 |

| Diameter (m) |

∼170 |

| Rotation period (hr) |

unknown |

| Optical albedo |

unknown |

| Radar albedo |

unknown |

| Spectral class |

unknown |

Table 11.

System parameters for the observation of 2005 LW3.

Table 11.

System parameters for the observation of 2005 LW3.

| |

Transmitter |

Receiver 1 |

Receiver 2 |

| |

DSS-63 |

Effelsberg |

Medicina |

| Diameter |

70 m |

100 m |

32 m |

| Aperture efficiency |

0.70 |

0.55 |

0.52 |

| Tx Frequency |

7167 MHz |

- |

| Tx Power |

20 kW |

- |

- |

| Tx Waveform |

CW |

- |

- |

| System Temperature |

- |

30–40 K |

90 K |

| Polarization |

RCP |

LVP, LHP |

RCP, LCP |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).