3.1. Cultivars Showed Differences in Precocity, Nutrient Concentrations, LMA and Physiological Performance

Cobrançosa started bearing fruit earlier but did not yield more total biomass than Arbequina. Cobrançosa is a larger-sized cultivar than Arbequina, the latter being frequently grown in hedgerow systems, with precocity being an important trait of the cultivar given the high financial input involved [

24,

25]. However, Cobrançosa passed the juvenile period even more quickly than Arbequina, having started producing fruit in the second year of growth, which seems to be an important characteristic of this cultivar to highlight.

Cobrançosa tended to show lower concentrations of some macronutrients in the leaves (N, P and Mg) and higher concentrations in the roots than Arbequina. This may be a result of the remobilization of nutrients to the fruits, which occurs mainly from the leaves [

26]. Moreover, the higher degree of sclerophylly of Cobrançosa leaves expressed by the superior LMA (+ 36.3%) may also be involved in these responses, as LMA values generally show an inverse correlation with the mineral’s concentrations [

27,

28,

29]. As pointed out by Bussoti et al. [

27], a lower nutrient concentration in sclerophyllous leaves may not indicate poor nutrient status, suggesting that minerals are simply more diluted as higher sclerophylly implies a greater metabolic activity in producing structural carbon compounds, generally to overcome stress conditions. Confirming this premise, previous studies demonstrated that Cobrançosa is a cultivar better adapted to drought stress [

30,

31]. On the other hand, Cobrançosa is very popular in marginally cultivated regions, well adapted to rainfed agriculture and acidic, P-poor soils, often presenting low levels of macronutrients in the leaves without this apparently affecting its productivity [

14,

16,

23]. In the Cobrançosa cultivar, a tendency towards the accumulation of nutrients in the roots, when available in the soil, mainly P, was observed, with the roots appearing to function as a buffer for the concentration of nutrients in the leaves [

32].

Regarding micronutrients, perhaps the most relevant was the observation in Cobrançosa of lower Fe and higher Mn levels than in Arbequina, found consistently in all tissues. Arbequina cultivation is common in arid and semi-arid regions of Southern Europe [

24], where neutral to alkaline soils predominate, a condition that reduces the availability of Fe in the soil [

4,

5]. Perhaps this is why Arbequina is efficient at absorbing Fe, as is the case of many other calcicolous species and cultivars adapted to alkaline soils [

33]. For its part, Cobrançosa is commonly grown in acidic soils, with high levels of available Mn. High levels of Mn were also observed in the leaves of other acidophilic species in the region [

12,

13,

20] and, perhaps for this reason, nutrient concentrations in Cobrançosa were higher than in Arbequina.

In terms of functional leaf characteristics, expressed by leaf gas exchange variables, Cobrançosa showed higher net photosynthesis due to superior stomatal conductance, probably as a result of lower leaf area per plant which provides more water per unit of leaf area. In fact, considering the values of leaf dry weight and LMA presented in

Figure 1 and

Table 6, respectively, we estimate that the mean leaf area per plant was 8.16 dm

2 in Cobrançosa and 10.45 dm

2 in Arbequina. Furthermore, our results suggest that the variations in leaf mineral concentrations between cultivars did not have a significant effect on the photosynthetic rate and that in the present growing conditions the integration of all leaf gas exchange data allows us to infer that Arbequina leaves did not present more biochemical limitations to the photosynthetic process than Cobrançosa.

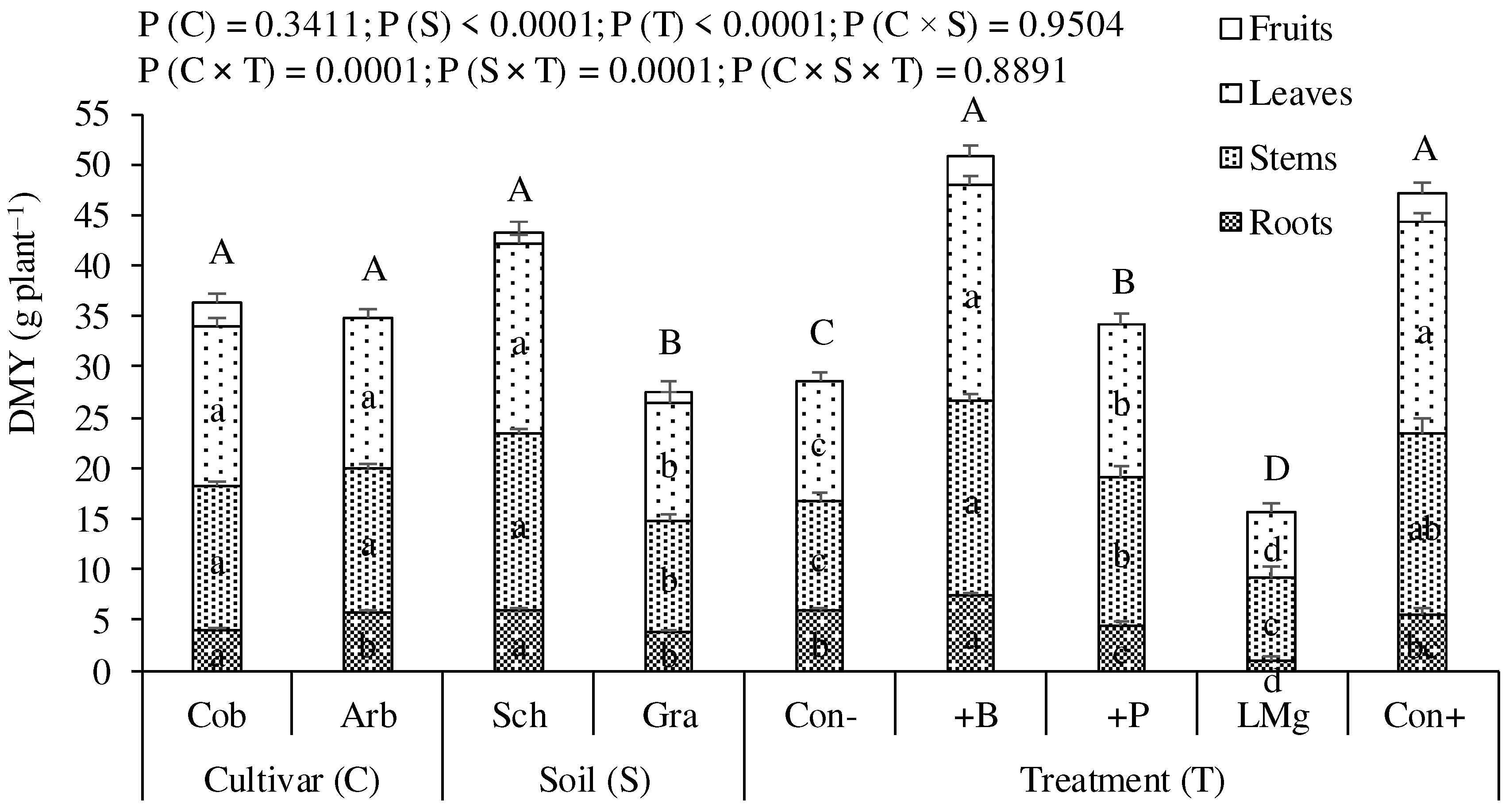

3.2. Schist and Granite Soils Showed Different Nutrient Bioavailability and Photosynthetic Activity

Plants grown in schist soil recorded higher total DMY and individually in each plant parts, roots, stems, leaves and fruits, the latter being absent in Arbequina, being these responses associated with the significant larger leaf area per plant (+62.7%), estimated as 11.27 and 6.93 dm

2 by the methodology described in 4.1 section, and net photosynthesis (+21.1%). Plants grown in schist showed higher N concentrations in all tissues than those grown in granite soil. The schist soil had a higher organic matter content than the granite soil at the beginning of the experiment. Soil aeration, increased temperature and water availability are the main factors that activate soil microbiology and stimulate the mineralization of organic matter [

5,

34,

35]. In this experiment, soil sampling and sieving, greenhouse cultivation and regular irrigation will have contributed to enhancing the mineralization of organic matter, with the increase in N supply being the most likely cause for the significant effect of schist soil to the observed increase in DMY. At the same time, plants grown in schist soil had higher Mn levels in all tissues than plants grown in granite soil. Acidic soils can present large amounts of Mn in solution, especially for pH below 5 [

4,

33]. In this region, due to the usually very low pH of the soils, very high levels of Mn have been observed in the tissues of cultivated plants [

12,

13,

20]. As the initial pH was slightly lower and Mn levels were higher in schist soil (

Table 7), this seems to be the most obvious reason to justify the higher Mn values in the tissues of plants grown in schist soil. With the range of Mn values found in this study, especially in leaves, we believe that the higher Mn concentrations will also have contributed to the improvement of photosynthetic activity and productivity. Mn plays a role in diverse processes of a plant’s life cycle such as the water-splitting reaction in photosystem II, the first step of photosynthesis, as well in respiration, scavenging of reactive oxygen species and hormone signaling [

36]. The superior concentration of Mg and Zn in the leaves of plants that grew in the schist soil also deserve to be highlighted in the performance of olive trees. Magnesium is required for chlorophyll formation, playing a key role in the structure and photochemical activities of photosystems, photosynthetic electron transport and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity, being also involved in carbohydrate transport from source-to-sink organs [

37]. In turn, zinc plays fundamental roles in various physiological and molecular mechanisms such as plant water relations, cell membrane stability, osmolyte accumulation, stomatal regulation, water use efficiency, photosynthesis, hormonal balance and antioxidant system, thus resulting in significantly better plant performance [

38].

Plants grown in schist soil had lower P levels in all tissues. At the beginning of the experiment (

Table 7), both soils had low P content, a common characteristic of these soils in the region [

12,

14]. Perhaps the result is due to a dilution effect, resulting from an equivalent availability of P in both soils and a greater production of biomass in the schist soil. The nutrient dilution/concentration effect is a common phenomenon that occurs when any agro-environmental factor other than the availability of a nutrient in the soil causes some change in DMY [

35,

39,

40]. It could also be hypothesized that granite soil has greater P bioavailability than schist soil. However, as far as we know, there is no previous experimental evidence comparing these soils that proves this second hypothesis.

Plants grown in schist soil had lower B concentrations in leaves and roots than those grown in granite soil. In this region, both schist and granite soils provide little B to plants [

12,

18,

19,

41]. As schist soils gave rise to greater DMY, perhaps there was some dilution effect, as mentioned for P. However, the schist soil had not been cultivated for some time and the granite soil was taken from a vineyard, which is one of the crops where farmers most regularly apply B as a fertilizer [

34,

42]. Thus, initial B contents were, unsurprisingly, higher in the granite soil (

Table 7) and this contributed to the higher tissue B concentrations in plants grown in this soil.

Most of the soil properties determined at the end of the study showed the trend observed in the determinations of the initial soil samples, with a higher content of organic matter, extractable K and exchangeable Ca and Mg, for example, in schist soil and a higher content of B, for example, in granite soil. Thus, cultivation will not have influenced much on the properties of the soil. However, the evolution of P levels in the soil deserves some attention. The initial P content in the soils were low and not very different in the two soils (

Table 7). At the end of the experiment, P levels appeared higher in the granite soil. Although the schist soil resulted in a higher DMY, which could have led to a greater P uptake, the observed difference suggests that there may be other causes. Most plants, especially trees and shrubs, are known to develop mutualistic associations with mycorrhizal fungi [

32,

43]. Although mycorrhizal fungi can be associated with numerous benefits for plants, the most abundantly documented is the increase in P bioavailability [

32,

33,454]. It is expected that aspects associated with plant mycorrhization have promoted P solubility in the less acidic granite soil and help to justify the differences observed in P levels in the two soils. Root colonization with mycorrhizae is an important aspect in the adaptation of plants to acidic mineral soils with low P availability and high Al content [

33,

45].

The joint analysis of all leaf gas exchange data revealed that plants that grew in the schist soil showed greater photosynthetic performance due to lower non-stomatal limitations, largely determined by better nutritional status, as previously mentioned, namely the higher N, Mg, Mn and Zn levels in leaves, but also due to inferior stomatal limitations, an indication of foremost water status. The last reason is interesting, given that the leaf area per plant was significantly higher in the plants that grew in the schist soil, as mentioned before. The higher organic matter, clay and silt levels and the lower sand content contributed to greater water holding capacity of the schist soil, while the greater biomass of the root system allows the enhancement of water absorption.

3.3. LMg Treatment Drastically Reduced Plant Growth by Preventing B Uptake

The +B and Con+ treatments gave rise to higher DMY than the other treatments and were the only treatments bearing fruit. These two treatments have in common the application of B, which made possible to increase the leaf area per plant to 12.59 and 12.93 dm

2, respectively, while in the other treatments the values were 9.48, 6.89 and 3.75 dm

2 in +P, Con- and LMg, respectively. In addition, the less productive treatments also presented lower net photosyntetic rate and, in general, higher LMA. The lack of nutrients will decrease growth more than photosynthesis, leading to accumulation of total nonstructural carbohydrates, which may increase LMA [

28]. Taking into account that in the treatments that did not receive B, the average levels of the nutrient in the leaves were low (12.6 to 17.2 mg kg

–1), when compared with the values of the sufficiency range for mature olive trees (20-75 mg kg

–1 in the summer season) [

46], it is likely that B availability had a major influence on the difference in DMY, plant leaf area and leaf gas exchange traits observed in the different treatments. B is a nutrient of particular importance for dicotyledonous, being required in greater amounts than any other micronutrient, playing an important role in the cell wall biosynthesis and in several metabolic pathways such as amino acid and protein metabolism [

47,

48]. B deficiency also results in a decrease in the reproductive success because of poor flower production and pollen viability. The reproductive failure can be observed even without deficiency symptoms in the foliage, suggesting that the B requirement for the reproductive process is greater than for vegetative tissues [

48]. Therefore, it seems unequivocal that B played a determining role in the presence of fruits on plants. The results of biomass production and reproductive success of B treatments are in line with those of many other studies that highlighted the importance of B for the cultivation of dicots in the region [

12,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The LMg treatment resulted in lower DMY, leaf area and net photosynthesis than Con-. This result is unexpected, considering that increasing pH and supplying Ca and Mg to acidic soils are the main aspects of liming that normally justify an increase in DMY [

6,

10]. In the LMg treatment, all growth tips died, and chlorosis appeared in the apical part of the basal leaves, typical symptoms of severe B deficiency [

16,

49]. In this treatment, the biomass in the root system was particularly low, response that compromises the absorption of water and minerals. In terms of leaf gas exchange traits, LMg trees registered the lowest values of A, g

s and A/g

s and the highest of Ci/Ca, which means that, apart the stomatal limitations, several non-stomatal components negatively influenced net photosynthetic productivity and consequently all plant growth and development [

50]. The negative influence of B deficiency on A and g

s was reported from previous studies [

51,

52,

53,

54]. B availability is related to soil pH. The element is more available in acidic soils, with deficiency being common at high pH levels in sandy soils due to their low B content [

5,

48]. At high pH, B is quite tightly bound, especially between pH 7 and 9, which is the range of lowest availability of the element [

5,

21]. In addition, plants tend to have a greater need for B if Ca is abundant [

5]. Furthermore, at alkaline pH levels, B is adsorbed by organic colloids with a binding strength even greater than that of inorganic colloids [

5]. In the LMg treatment the pH reached 7.36, which constitutes a situation of overliming, and was the cause of the severe B deficiency. However, in the Con+ treatment the pH reached an even higher value (7.48), and this treatment was associated with high DMY. The B applied in this treatment appears to have been sufficient to counterbalance the strong reduction in nutrient availability caused by the increase in pH and Ca supply.

The Con- treatment resulted in lower DMY than the other treatments, excluding LMg. Con- was the only treatment that did not receive N. When the effect of the soils was compared, it became clear that it was the difference in N availability that led to greater DMY in the schist soil. On the other hand, it can be observed that in the Con- treatment the N levels in the tissues were very low, and in the case of leaves, well below the sufficiency range established for mature trees [

46]. Therefore, it seems clear that it was the lower availability of N in the soil that led to the low DMY in this treatment. N is an ecological factor determining agricultural productivity, and it is also common to observe a response to the application of the nutrient in field and pot experiments carried out on olive [

16,

55,

56]. It should be noted that Con- treatment did not present stomatal limitations to photosynthesis, a fact that is associated with the low size of the leaf area and the large accumulation of biomass in root system, the second in absolute terms, right after the +B treatment. However, Con- treatment showed lower intrinsic water use efficiency than the more productive treatments, aspect associated with non-stomatal limitations for photosynthesis, probably related with the low N and Zn concentrations in the leaves.

The +P treatment resulted in plants with a lower concentration of B in the leaves than the LMg treatment itself, without such a sharp drop in DMY. This phenomenon has been called the Piper-Steenbjerg effect in the literature and represents situations in which the supply of a nutrient, previously in a situation of severe deficiency, stimulates plant growth at a rate higher than the uptake of the nutrient, leading to its dilution in the tissues [

39,

57]. As far as we know, for B the effect has only been described for sugar beet [

58]. The result observed in this experiment may have the following explanation. In the LMg treatment, all new shoots dried due to a lack of B, leaving old leaves, some already present on the cuttings, with B concentrations that were not so low, as a result of reduced B mobility in the plant. B is a unique nutrient with regard to its mobility in plants. It appears to have restricted mobility in several species due to restricted mobility in the phloem, while being quite mobile in others [

48,

59]. In olive trees, a study with the Manzanillo cultivar showed some B mobility in plant tissues [

60], while in other studies it appears that B mobility depends on the cultivar [

17]. This study seems to show that for the cultivars Cobrançosa and Arbequina the mobility of B is quite low.