Submitted:

26 November 2023

Posted:

27 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

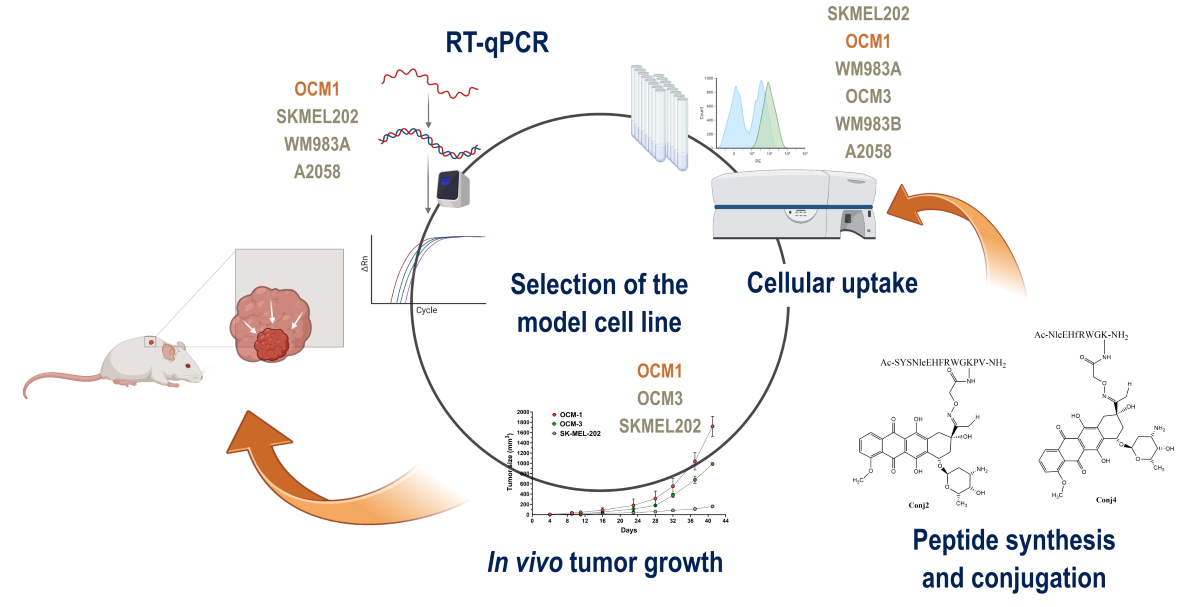

2. Results

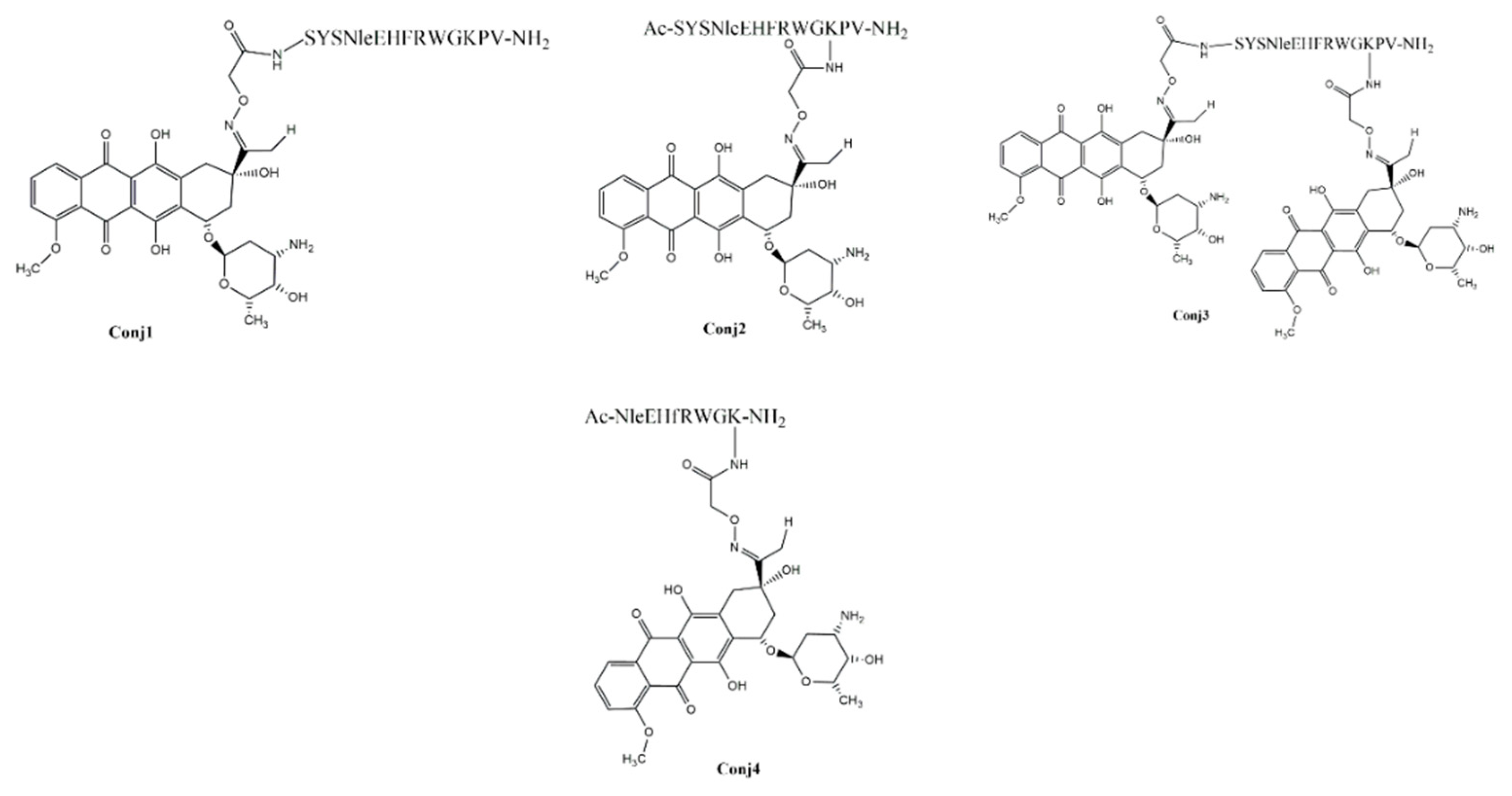

2.1. Synthetic Procedures and Chemical Characterization

2.2. Biological Characterization of the Full Length α-MSH Drug Conjugates

2.2.1. In Vitro Antiproliferative Activity of Full Length α-MSH Drug Conjugates

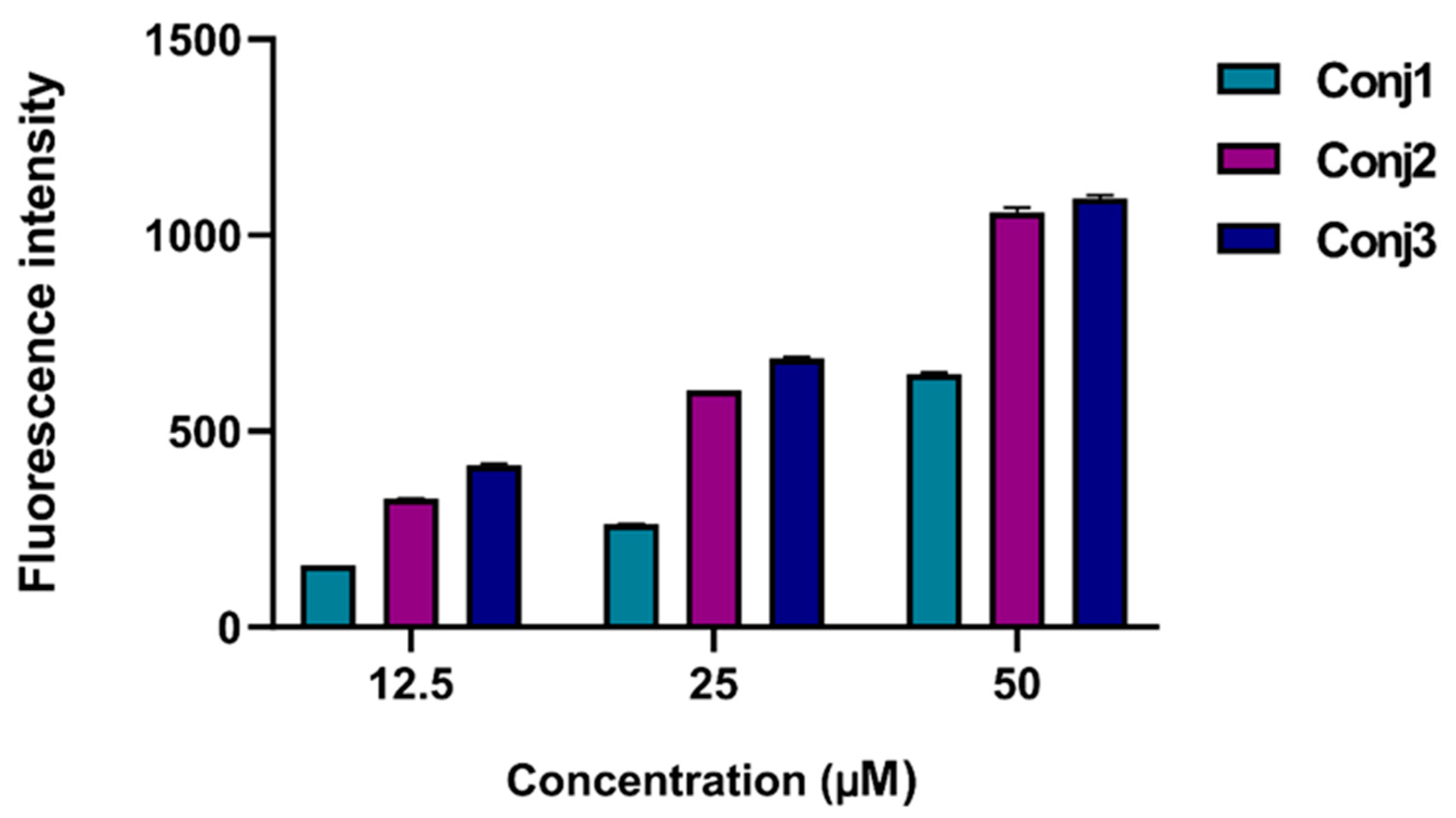

2.2.2. In Vitro Flow Cytometry Evaluation of Full Length α-MSH Drug Conjugates

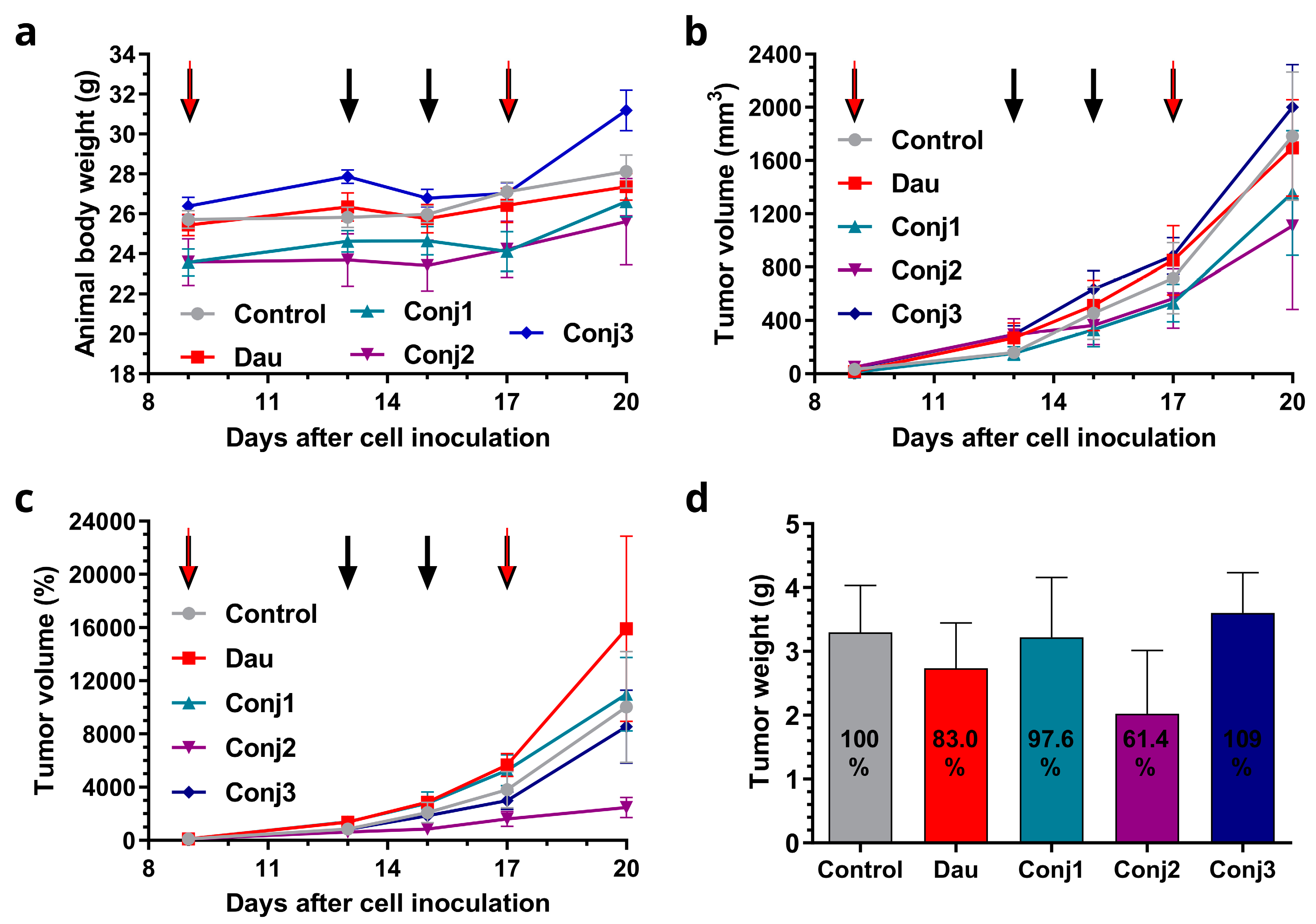

2.2.3. In Vivo Antitumor Effect of Full Length α-MSH Drug Conjugates on B16 Melanoma Model

2.3. Biological Characterization of the Sequentially Optimized α-MSH Drug Conjugate, Conj4

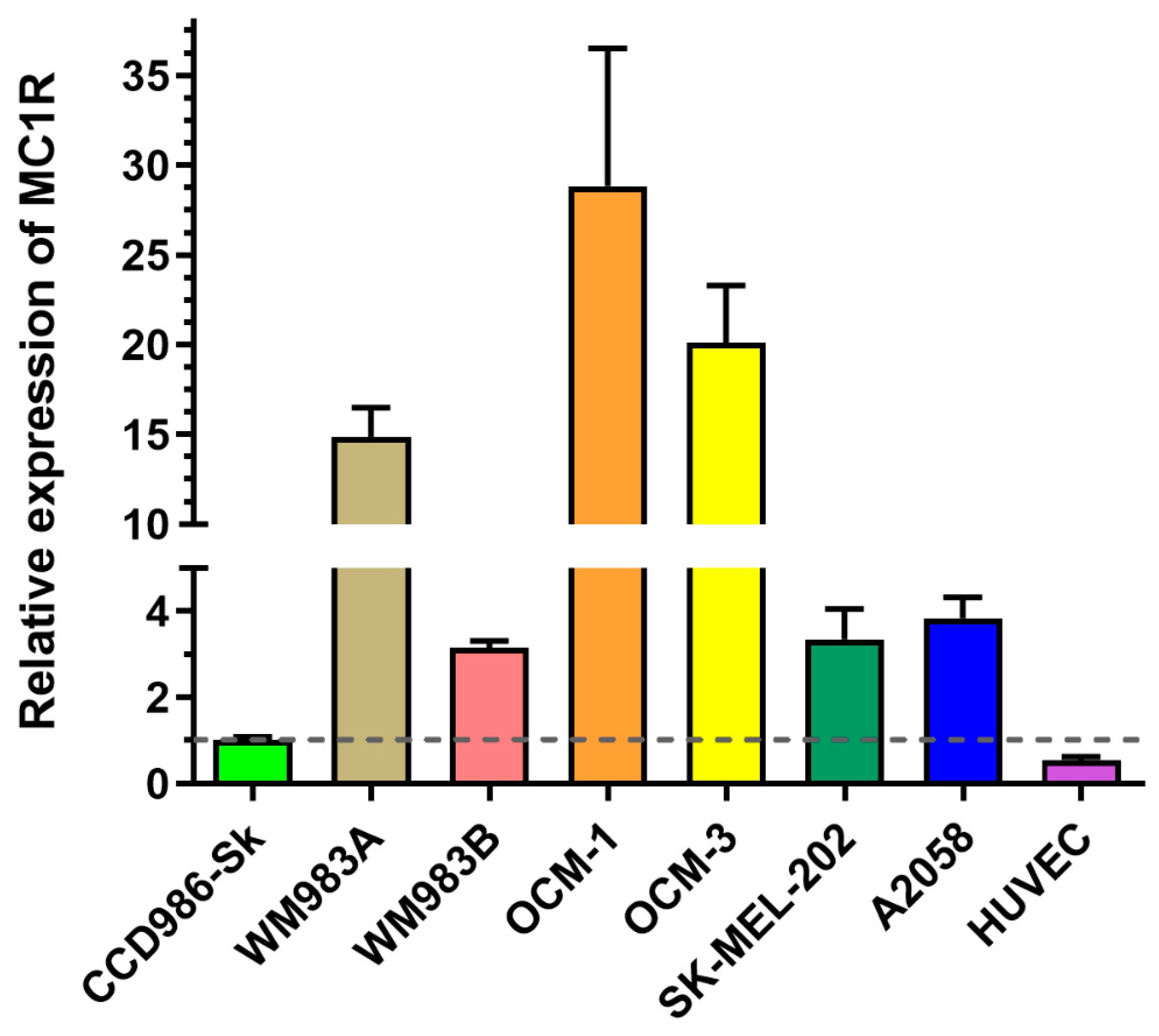

2.3.1. Experimental Model Selection Based on MC1R Expression

2.3.2. In Vitro Cytostatic Effect of the Conj4 Compared to the Conj2

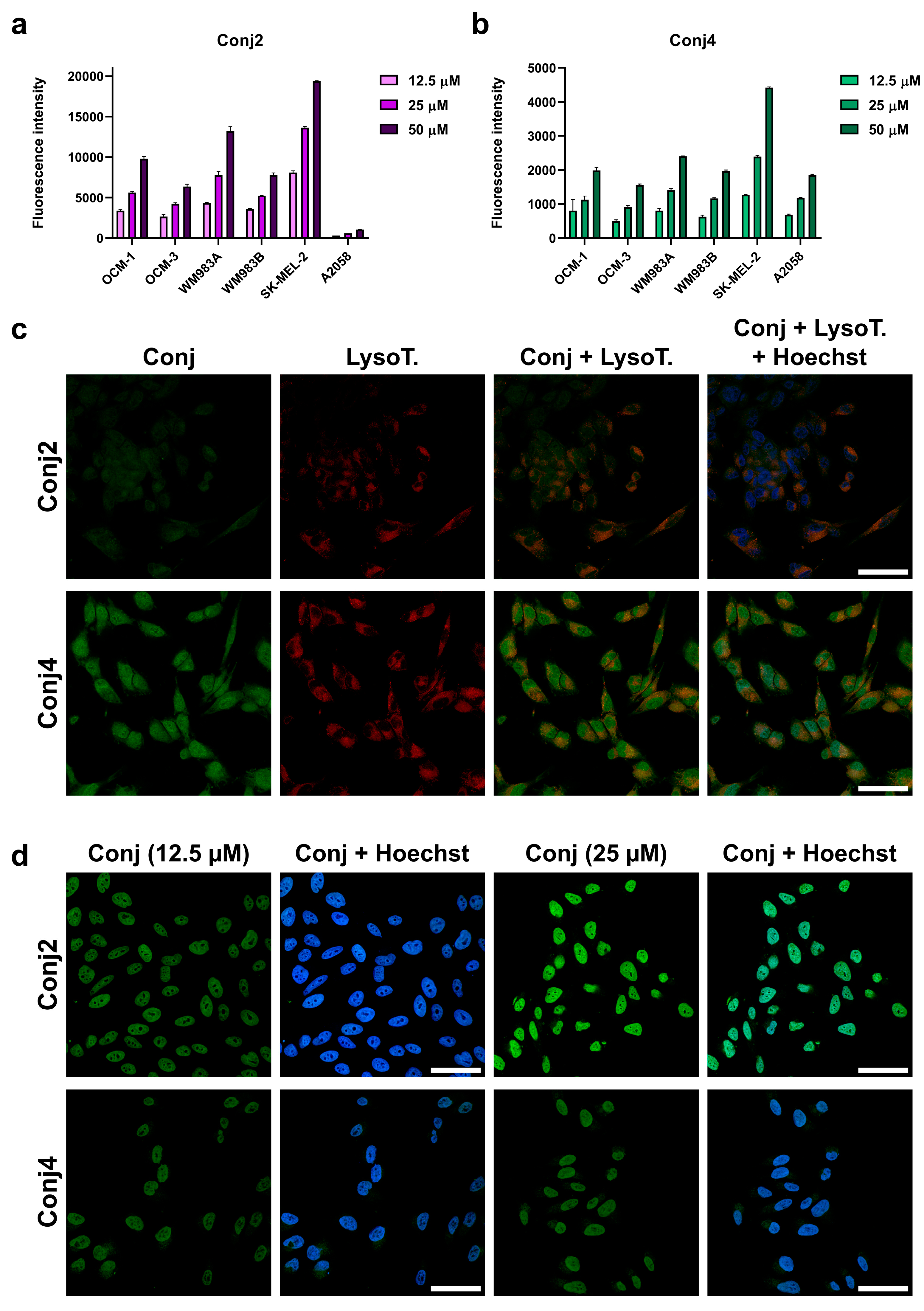

2.3.3. In Vitro Flow Cytometry and Confocal Microscopy Evaluation

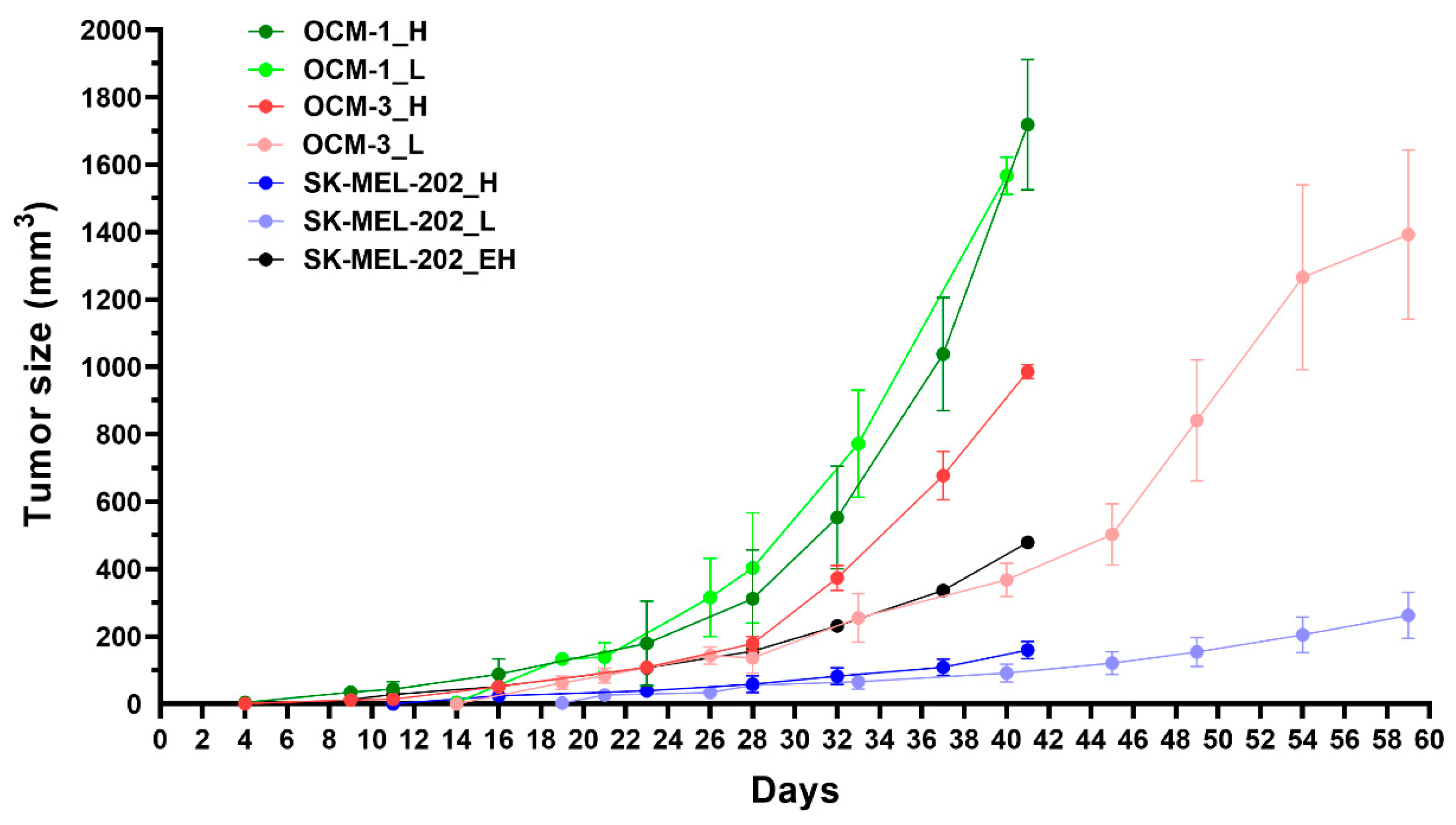

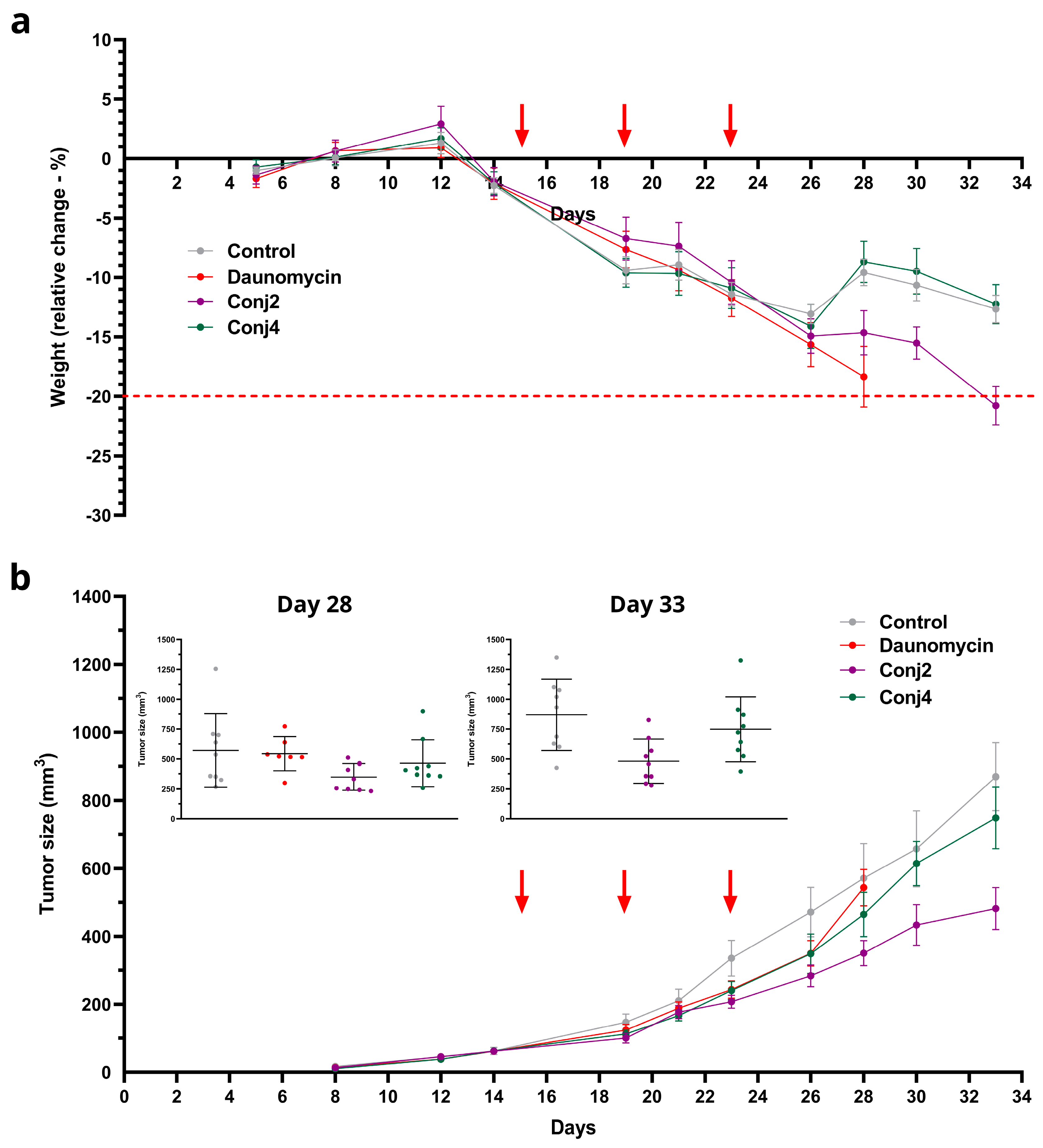

2.3.4. In Vivo Experiments

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthetic Procedures and Chemical Characterization

4.3. Reverse Phase High-Performance Liquid Chomatography (RP-HPLC)

4.4. Electrospray Ionization-High-Resolution Mass Spectromerty (ESI-HRMS)

4.5. Cell Culturing

4.6. Determination of mRNA Expression Level of Melanoma Cells by qPCR

4.7. Determination of the In Vitro Antiproliferative Activity

4.8. In Vitro Flow Cytometry Evaluation

4.9. Immunostaining and Confocal Microscopy

4.10. Experimental Animals

4.11. Acute Toxicity Study of Drug, Conj2 and Conj4

4.12. In Vivo Antitumor effect of Drug, Conj2 and Conj4

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71. [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A.M.; Spatz, A.; Robert, C. Cutaneous Melanoma. The Lancet 2014, 383, 816–827. [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.H.; From, L.; Bernardino, E.A.; Mihm, M.C. The Histogenesis and Biologic Behavior of Primary Human Malignant Melanomas of the Skin. Cancer Res 1969, 29, 705–727.

- Helmbach, H.; Rossmann, E.; Kern, M.A.; Schadendorf, D. Drug-Resistance in Human Melanoma. Int J Cancer 2001, 93, 617–622. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.S.; Chapman, P.B. The History and Future of Chemotherapy for Melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009, 23, 583–597. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, H.; Mishra, P.K.; Ekielski, A.; Jaggi, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Talegaonkar, S. Melanoma Treatment: From Conventional to Nanotechnology. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2018, 144, 2283–2302. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.M.; Suciu, S.; Mortier, L.; Kruit, W.H.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Trefzer, U.; Punt, C.J.A.; Dummer, R.; Davidson, N.; et al. Extended Schedule, Escalated Dose Temozolomide versus Dacarbazine in Stage IV Melanoma: Final Results of a Randomised Phase III Study (EORTC 18032). Eur J Cancer 2011, 47, 1476–1483. [CrossRef]

- Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Guida, M.; Ridolfi, R.; Romanini, A.; Brugnara, S.; Del Bianco, P.; Perfetti, E.; Cavallo, R.; Pigozzo, J.; Donati, D.; et al. Temozolomide (TMZ) as Prophylaxis for Melanoma Brain Metastases (BrM): Results from a Phase III, Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008, 26, 20014–20014. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.J.; Rigel, D.S.; Kopf, A.W. Early Detection of Malignant Melanoma: The Role of Physician Examination and Self-Examination of the Skin. CA Cancer J Clin 1985, 35, 130–151. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Collichio, F.; Ollila, D.; Moschos, S. Historical Review of Melanoma Treatment and Outcomes. Clin Dermatol 2013, 31, 141–147. [CrossRef]

- Rebecca, V.W.; Sondak, V.K.; Smalley, K.S.M. A Brief History of Melanoma. Melanoma Res 2012, 22, 114–122. [CrossRef]

- Gerstenblith, M.R.; Goldstein, A.M.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Peris, K.; Landi, M.T. Comprehensive Evaluation of Allele Frequency Differences of MC1R Variants across Populations. Hum Mutat 2007, 28, 495–505. [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, K.A.; Shekar, S.L.; Newton, R.A.; James, M.R.; Stow, J.L.; Duffy, D.L.; Sturm, R.A. Receptor Function, Dominant Negative Activity and Phenotype Correlations for MC1R Variant Alleles. Hum Mol Genet 2007, 16, 2249–2260. [CrossRef]

- Schiöth, H.B.; Phillips, S.R.; Rudzish, R.; Birch-Machin, M.A.; Wikberg, J.E.S.; Rees, J.L. Loss of Function Mutations of the Human Melanocortin 1 Receptor Are Common and Are Associated with Red Hair. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999, 260, 488–491. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, L.; Milne, R.; Bravo, J.; Lopez, J.; Avilés, J.; Longo, M.; Benítez, J.; Lázaro, P.; Ribas, G. MC1R: Three Novel Variants Identified in a Malignant Melanoma Association Study in the Spanish Population. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 1659–1664. [CrossRef]

- Ichii-Jones, F.; Yengi, L.; Bath, J.; Fryer, A.A.; Strange, R.C.; Lear, J.T.; Heagerty, A.H.M.; Smith, A.G.; Hutchinson, P.E.; Osborne, J.; et al. Susceptibility to Melanoma: Influence of Skin Type and Polymorphism in the Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone Receptor Gene. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 1998, 111, 218–221. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.; ter Huurne, J.; Berkhout, M.; Gruis, N.; Bastiaens, M.; Bergman, W.; Willemze, R.; Bouwes Bavinck, J.N. Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) Gene Variants Are Associated with an Increased Risk for Cutaneous Melanoma Which Is Largely Independent of Skin Type and Hair Color. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2001, 117, 294–300. [CrossRef]

- Landi, M.T.; Kanetsky, P.A.; Tsang, S.; Gold, B.; Munroe, D.; Rebbeck, T.; Swoyer, J.; Ter-Minassian, M.; Hedayati, M.; Grossman, L.; et al. MC1R, ASIP, and DNA Repair in Sporadic and Familial Melanoma in a Mediterranean Population. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2005, 97, 998–1007. [CrossRef]

- Matichard, E. Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) Gene Variants May Increase the Risk of Melanoma in France Independently of Clinical Risk Factors and UV Exposure. J Med Genet 2004, 41, 13e–113. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.S.; Duffy, D.L.; Box, N.F.; Aitken, J.F.; O’Gorman, L.E.; Green, A.C.; Hayward, N.K.; Martin, N.G.; Sturm, R.A. Melanocortin-1 Receptor Polymorphisms and Risk of Melanoma: Is the Association Explained Solely by Pigmentation Phenotype? The American Journal of Human Genetics 2000, 66, 176–186. [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, S.; Sera, F.; Gandini, S.; Iodice, S.; Caini, S.; Maisonneuve, P.; Fargnoli, M.C. MC1R Variants, Melanoma and Red Hair Color Phenotype: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Cancer 2008, 122, 2753–2760. [CrossRef]

- Stratigos, A.J.; Dimisianos, G.; Nikolaou, V.; Poulou, M.; Sypsa, V.; Stefanaki, I.; Papadopoulos, O.; Polydorou, D.; Plaka, M.; Christofidou, E.; et al. Melanocortin Receptor-1 Gene Polymorphisms and the Risk of Cutaneous Melanoma in a Low-Risk Southern European Population. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2006, 126, 1842–1849. [CrossRef]

- Valverde, P. The Asp84Glu Variant of the Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) Is Associated with Melanoma. Hum Mol Genet 1996, 5, 1663–1666. [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, P.A.; Sandkuijl, L.A.; Bergman, W.; Pavel, S.; van Mourik, L.; Frants, R.R.; Gruis, N.A. Melanocortin-1 Receptor Variant R151C Modifies Melanoma Risk in Dutch Families with Melanoma. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2001, 69, 774–779. [CrossRef]

- Eberle, A.N.; Rout, B.; Bigliardi Qi, M.; L. Bigliardi, P. Synthetic Peptide Drugs for Targeting Skin Cancer: Malignant Melanoma and Melanotic Lesions. Curr Med Chem 2017, 24, 1797–1826. [CrossRef]

- Eberle, A.N.; Siegrist, W.; Bagutti, C.; Tapia, J.C.-D.; Solca, F.; Wikberg, J.E.S.; Chhajlani, V. Receptors for Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone on Melanoma Cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993, 680, 320–341. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Sharma, S.D.; Fink, J.L.; Hadley, M.E.; Hruby, V.J. Melanotropic Peptide Receptors: Membrane Markers of Human Melanoma Cells. Exp Dermatol 1996, 5, 325–333. [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Onfray, F.; López, M.; Lundqvist, A.; Aguirre, A.; Escobar, A.; Serrano, A.; Korenblit, C.; Petersson, M.; Chhajlani, V.; Larsson, O.; et al. Tissue Distribution and Differential Expression of Melanocortin 1 Receptor, a Malignant Melanoma Marker. Br J Cancer 2002, 87, 414–422. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, W.; Stutz, S.; Eberle, A.N. Homologous and Heterologous Regulation of Alpha-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone Receptors in Human and Mouse Melanoma Cell Lines. Cancer Res 1994, 54, 2604–2610.

- Hruby, V.J.; Sharma, S.D.; Toth, K.; Jaw, J.Y.; Al-Obeidi, F.; Sawyer, T.K.; Hadley, M.E. Design, Synthesis, and Conformation of Superpotent and Prolonged Acting Melanotropins. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993, 680, 51–63. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, W.; Solca, F.; Stutz, S.; Giuffrè, L.; Carrel, S.; Girard, J.; Eberle, A.N. Characterization of Receptors for Alpha-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone on Human Melanoma Cells. Cancer Res 1989, 49, 6352–6358.

- Miao, Y.; Hylarides, M.; Fisher, D.R.; Shelton, T.; Moore, H.; Wester, D.W.; Fritzberg, A.R.; Winkelmann, C.T.; Hoffman, T.; Quinn, T.P. Melanoma Therapy via Peptide-Targeted α-Radiation. Clinical Cancer Research 2005, 11, 5616–5621. [CrossRef]

- Michael F. Giblin; Nannan Wang; Timothy J. Hoffman; Silvia S. Jurisson; Thomas P. Quinn Design and Characterization of α-Melanotropin Peptide Analogs Cyclized through Rhenium and Technetium Metal Coordination. PNAS 1998, 95, 12814–12818. [CrossRef]

- Cone, R.D.; Mountjoy, K.G.; Robbins, L.S.; Nadeau, J.H.; Johnson, K.R.; Roselli-Rehfuss, L.; Mortrud, M.T. Cloning and Functional Characterization of a Family of Receptors for the Melanotropic Peptides. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993, 680, 342–363. [CrossRef]

- Morandini, R.; Suli-Vargha, H.; Libert, A.; Loir, B.; Botyánszki, J.; Medzihradszky, K.; Ghanem, G. Receptor-Mediated Cyotoxicity of a-MSH Fragments Containing Melphalan in a Human Melanoma Cell Line. Int J Cancer 1994, 56, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, T.K.; Sanfilippo, P.J.; Hruby, V.J.; Engel, M.H.; Heward, C.B.; Burnett, J.B.; Hadley, M.E. 4-Norleucine, 7-D-Phenylalanine-Alpha-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone: A Highly Potent Alpha-Melanotropin with Ultralong Biological Activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1980, 77, 5754–5758. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yang, J.; Gallazzi, F.; Miao, Y. Effects of the Amino Acid Linkers on the Melanoma-Targeting and Pharmacokinetic Properties of 111 In-Labeled Lactam Bridge–Cyclized α-MSH Peptides. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2011, 52, 608–616. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xie, J.; Niu, G.; Zhang, F.; Gao, H.; Yang, M.; Quan, Q.; Aronova, M.A.; Zhang, G.; Lee, S.; et al. Chimeric Ferritin Nanocages for Multiple Function Loading and Multimodal Imaging. Nano Lett 2011, 11, 814–819. [CrossRef]

- Süli-Vargha, H.; Botyánszki, J.; Medzihradszky-Schweiger, H.; Medzihradszky, K. Synthesis of α-MSH Fragments Containing Phenylalanine Mustard for Receptor Studies. Int J Pept Protein Res 1990, 36, 308–315. [CrossRef]

- Sylvie Froidevaux; Martine Calame-Christe; Heidi Tanner; Alex N. Eberle Melanoma Targeting with DOTA-α-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone Analogs: Structural Parameters Affecting Tumor Uptake and Kidney Uptake. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2005, 46, 887–895.

- Uchida, M.; Flenniken, M.L.; Allen, M.; Willits, D.A.; Crowley, B.E.; Brumfield, S.; Willis, A.F.; Jackiw, L.; Jutila, M.; Young, M.J.; et al. Targeting of Cancer Cells with Ferrimagnetic Ferritin Cage Nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc 2006, 128, 16626–16633. [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, L.; Falvo, E.; Fornara, M.; Di Micco, P.; Benada, O.; Krizan, J.; Svoboda, J.; Hulikova-Capkova, K.; Morea, V.; Boffi, A.; et al. Selective Targeting of Melanoma by PEG-Masked Protein-Based Multifunctional Nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 1489–1509. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yang, J.; Miao, Y. Dual Receptor-Targeting 99mTc-Labeled Arg-Gly-Asp-Conjugated Alpha-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone Hybrid Peptides for Human Melanoma Imaging. Nucl Med Biol 2015, 42, 369–374. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, H.; Padilla, R.S.; Berwick, M.; Miao, Y. Replacement of the Lys Linker with an Arg Linker Resulting in Improved Melanoma Uptake and Reduced Renal Uptake of Tc-99m-Labeled Arg-Gly-Asp-Conjugated Alpha-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone Hybrid Peptide. Bioorg Med Chem 2010, 18, 6695–6700. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Mowlazadeh Haghighi, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Hruby, V.J.; Cai, M. Development of Ligand-Drug Conjugates Targeting Melanoma through the Overexpressed Melanocortin 1 Receptor. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2020, 3, 921–930. [CrossRef]

- Varga, J.M.; Asato, N.; Lande, S.; Lerner, A.B. Melanotropin–Daunomycin Conjugate Shows Receptor-Mediated Cytotoxicity in Cultured Murine Melanoma Cells. Nature 1977, 267, 56–58. [CrossRef]

- Süli-Vargha, H.; Jeney, A.; Kopper, L.; Oláh, J.; Lapis, K.; Botyánszki, J.; Csukas, I.; Györvári, B.; Medzihradszky, K. Investigations on the Antitumor Effect and Mutagenicity of α-MSH Fragments Containing Melphalan. Cancer Lett 1990, 54, 157–162. [CrossRef]

- Chhajlani, V.; Xu, X.; Blauw, J.; Sudarshi, S. Identification of Ligand Binding Residues in Extracellular Loops of the Melanocortin 1 Receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996, 219, 521–525. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Borron, J.C.; Sanchez-Laorden, B.L.; Jimenez-Cervantes, C. Melanocortin-1 Receptor Structure and Functional Regulation. Pigment Cell Res 2005, 0, 051103015727002. [CrossRef]

- Wallin, E.; Heijne, G. Von Genome-Wide Analysis of Integral Membrane Proteins from Eubacterial, Archaean, and Eukaryotic Organisms. Protein Science 1998, 7, 1029–1038. [CrossRef]

- Frändberg, P.-A.; Doufexis, M.; Kapas, S.; Chhajlani, V. Cysteine Residues Are Involved in Structure and Function of Melanocortin 1 Receptor: Substitution of a Cysteine Residue in Transmembrane Segment Two Converts an Agonist to Antagonist. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001, 281, 851–857. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Laorden, B.L.; Sánchez-Más, J.; Turpín, M.C.; García-Borrón, J.C.; Jiménez-Cervantes, C. Variant Amino Acids in Different Domains of the Human Melanocortin 1 Receptor Impair Cell Surface Expression. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2006, 52, 39–46.

- Medzihradszky K Synthesis and Biological Activity of Adrenocorticotropic and Melanotropic Hormones. In Recent Developments in the Chemistry of Natural Carbon Compounds; Bogner, R., Bruckner, R., Szantay, C., Eds.; Hungarian Academy of Science: Budapest, 1976; pp. 207–250.

- Bregman, M.D.; Sawyer, T.K.; Hadley, M.E.; Hruby, V.J. Adenosine and Divalent Cation Effects on S-91 Melanoma Adenylate Cyclase. Arch Biochem Biophys 1980, 201, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Heward, C.B.; Yang, Y.C.S.; Ormberg, J.F.; Hadley, M.E.; Hruby, V.J. Effects of Chloramine T and Lodination on the Biological Activity of Melanotropin. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem 1979, 360, 1851–1860. [CrossRef]

- Heward, C.B.; Yang, Y.C.S.; Sawyer, T.K.; Bregman, M.D.; Fuller, B.B.; Hruby, V.J.; Hadley, M.E. Iodination Associated Inactivation of β-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1979, 88, 266–273. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, W.; Solca, F.; Stutz, S.; Giuffrè, L.; Carrel, S.; Girard, J.; Eberle, A.N. Characterization of Receptors for Alpha-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone on Human Melanoma Cells. Cancer Res 1989, 49, 6352–6358.

- Siegfried, J.M.; Burke, T.G.; Tritton, T.R. Cellular Transport of Anthracyclines by Passive Diffusion. Biochem Pharmacol 1985, 34, 593–598. [CrossRef]

- Willingham, M.C.; Cornwell, M.M.; Cardarelli, C.O.; Gottesman, M.M.; Pastan, I. Single Cell Analysis of Daunomycin Uptake and Efflux in Multidrug-Resistant and -Sensitive KB Cells: Effects of Verapamil and Other Drugs. Cancer Res 1986, 46, 5941–5946.

- Soliman, N.; Mamdouh, D.; Elkordi, A. Choroidal Melanoma: A Mini Review. Medicines 2023, 10, 11. [CrossRef]

- Denizot, F.; Lang, R. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cell Growth and Survival. J Immunol Methods 1986, 89, 271–277. [CrossRef]

- Altman, F.P. Tetrazolium Salts and Formazans. Prog Histochem Cytochem 1976, 9, III–51. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Peterson, D.A.; Kimura, H.; Schubert, D. Mechanism of Cellular 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Reduction. J Neurochem 1997, 69, 581–593. [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J Immunol Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Slater, T.F.; Sawyer, B.; Sträuli, U. Studies on Succinate-Tetrazolium Reductase Systems. Biochim Biophys Acta 1963, 77, 383–393. [CrossRef]

- Istivan, T.S.; Pirogova, E.; Gan, E.; Almansour, N.M.; Coloe, P.J.; Cosic, I. Biological Effects of a De Novo Designed Myxoma Virus Peptide Analogue: Evaluation of Cytotoxicity on Tumor Cells. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24809. [CrossRef]

- Kühn, J.; Shaffer, E.; Mena, J.; Breton, B.; Parent, J.; Rappaz, B.; Chambon, M.; Emery, Y.; Magistretti, P.; Depeursinge, C.; et al. Label-Free Cytotoxicity Screening Assay by Digital Holographic Microscopy. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2013, 11, 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Ward, K.M.; Prendergast, G.C.; Ayene, I.S. Hydroxyethyl Disulfide as an Efficient Metabolic Assay for Cell Viability in Vitro. Toxicology in Vitro 2012, 26, 603–612. [CrossRef]

- Paulus, J.; Nachtigall, B.; Meyer, P.; Sewald, N. RGD Peptidomimetic MMAE-Conjugate Addressing Integrin AVβ3-Expressing Cells with High Targeting Index**. Chemistry – A European Journal 2023, 29. [CrossRef]

- Overwijk, W.W.; Restifo, N.P. B16 as a Mouse Model for Human Melanoma. Curr Protoc Immunol 2000, 39. [CrossRef]

- Teicher B.A. Tumor Models in Cancer Research; Teicher, B.A., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; ISBN 978-1-60761-967-3.

| Code | Sequence | tR (min)1 | Mmo (Da)2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| calc | meas | differences (ppm) | |||

| Conj1 | Dau=Aoa-SYSNleEHFRWGKPV-NH2 | 12.6 | 2187.0266 | 2187.0080 | 18.56 |

| Conj2 | Ac-SYSNleEHFRWGK(Dau=Aoa)PV-NH2 | 13.0 | 2229.0371 | 2229.0214 | 15.66 |

| Conj3 | Dau=Aoa-SYSNleEHFRWGK(Dau=Aoa)PV-NH2 | 12.8 | 2769.2272 | 2769.6050 | 32.76 |

| Conj4 | Ac-NleEHfRWGK(Dau=Aoa)-NH2 | 12.9 | 1694.7876 | 1694.7692 | 18.36 |

| Cell line | IC501 | Relative potency2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conj1 (µM) | Conj2 (µM) | Conj3 (µM) | Dau (nM) | Conj1 | Conj2 | Conj3 | |

| B16 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 26.0 ± 8.0 | 0.0090 | 0.0093 | 0.0130 |

| A2058 | 9.8 ± 5.4 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 40.0 ± 6.5 | 0.0041 | 0.0125 | 0.0133 |

| M24 | 12.8 ± 1.6 | 11.5 ± 0.4 | 11.0 ± 0.8 | 118.8 ± 25.0 | 0.0093 | 0.0103 | 0.0108 |

| WM983B | 9.9 ± 1.5 | 7.9 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 49.8 ± 22.9 | 0.0050 | 0.0063 | 0.0138 |

| Code | IC50 (µM)1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCM-1 | OCM-3 | SK-MEL-202 | WM983A | WM983B | A2058 | |

| Free Dau | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.045 ± 0.12 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.33 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.07 |

| Conj2 | 2.51 ± 0.06 | 2.39 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.09 | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.95 ± 0.12 |

| Conj4 | 29.68 ± 0.06 | 25.47 ± 0.08 | 2.06 ± 0.10 | 13.50 ± 0.06 | 10.18 ± 0.06 | 7.15 ± 0.07 |

| Targeting Index (TI)2 | ||||||

| Conj2 | 2.30 | 1.85 | 2.74 | 1.90 | 2.61 | 1.00 |

| Conj4 | 1.47 | 1.31 | 1.30 | 0.84 | 1.93 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).