1. Introduction

The Sarcidano Horse is an autochthonous semi-feral breed of small horses native to Sarcidano, a region in the hearth of Sardinia (Italy). It belongs to the 26 minor Italian breeds of limited diffusion collected in the Stud Book managed, since 2018, by ANAREAI, the national association for the local horse and donkey breeds [

1]. These horses are locally known for their sturdy build and were traditionally used for rural work and riding. They live in conditions of geographical isolation, due to insularity and to the wild living environment, and are recognized for their endurance and adaptability to the local terrain. According to the breed standard, Sarcidano horses typically come only in basic coat colors, Chestnut, Bay, Black and sometimes Gray, without spotting or color dilution. Only two loci are involved in that hair coloration:

Extension locus, coding melanocortin-1-receptor (

MC1R) gene, and

Agouti locus, coding the agouti-signaling-protein (

ASIP) gene, that is

MC1R gene antagonist. The correct functioning of the

MC1R gene produces the MC1R protein, driving the eumelanin (black pigment) synthesis by melanocytes, producing Black coats [

2,

3]. Contrarily, alteration in the

MC1R gene Exon 1, produced by a C to a T transition, leads to phaeomelanin (reddish pigment) synthesis, producing Chestnut coats [

4]. The

ASIP gene produces the ASIP protein, which has the power to antagonize

MC1R gene functioning in the melanocytes located in the body but not in the extremities, thus producing Bay coats, resulting in reddish-brown body color with a black point coloration on the mane, tail, ear edges and lower legs [

5]. Antagonism of

MC1R by

ASIP gene is efficient only in dominant/non-mutant variant of the MC1R gene, whereas when the receptor is already defective, because of the C>T mutation explained above, the antagonism cannot occur, still producing a Chestnut coat [

2].

In a previous study on this breed, we focused on the genetic distribution of the coat color [

6]. Just thanks to that investigation, carried out on 70 horses and aimed to contributing to the general knowledge of this breed, we became aware of a certain inconsistency in the color assigned thorough visual evaluation compared to that detected by the genetic investigation. Since the genetic color is the only one that can be transmitted to offspring, the correct assignment of the parental coat color is essential to ensure both correct individual identification and the prediction of foal color, as stated in other studies conducted on other local breeds [

7,

8,

9]. In a wild population coat color provides camouflage and protection in natural environments, helping horses to blend into their surroundings and evade predators. Domestication and human selection introduced a variety of coat colors and patterns, that currently are typical of specific breeds [

10]. Diluted or spotted coats, for example, allowed easier recognition of domestic from wild animals, and were therefore probably sought in the early stages of domestication [

11]. Thus, the study of the coat color distribution could be also suggestive of possible crossing with domestic breeds, so contributing to the observation of the genetic isolation of local breeds. The correct coat color registration in individual documents avoids recognition errors, allows appropriate archiving of data, therefore granting to correctly assign relationships, to recognize family units and to predict the offspring’s coat color. Therefore, the aim of the present research was to compare visual and genetic coat color registration in a larger number of Sarcidano horses to develop an effective and low-cost system for correctly recording individual phenotypes.

3. Results and Discussion

Genotyping results showed the genetic coat color distribution in the examined population. The sequencing of the randomly chosen samples confirmed the assigned genotypes, assuring that the used PCR/RFLP methods were reliable and could be therefore used in genetic coat color assignment in horses for faster and cheaper analysis compared to sequencing.

MC1R gene genotyping started by amplification of the 320-bp fragment, corresponding to position 36,979,377 – 36,979,697 of the latest horse genome version EquCab3.0 (GCF_002863925.1). Digestion by

TaqI endonuclease detected the C>T transition (rs68458866), that allow to distinguish the wildtype dominant C from the mutant recessive T allele. The resulting genotype set was homozygous wild dominant C/C, heterozygous C/T and homozygous mutant recessive T/T. The main part of the analyzed Sarcidano horses carried the double recessive T/T genotype (58 heads, corresponding to 64% of the total studied population), 27 horses (30%) carried heterozygous genotype C/T, and only 5 horses carried the homozygous wild dominant genotype C/C, equivalent to 6% of the studied population. The resulting allele frequency was 79% for the T and 21% for the C allele (

Table 1).

The causative mutation falls at position chr:3: 36,979,560 producing TCC or TTC as possible codons at position 83 of the protein chain (NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_001108006.1), resulting in a Serine being replaced with a Phenylalanine [

6,

12]. This single mutation in the proteins’ primary structure is expected to alter the alpha-helix structure, thus producing a defective functioning of the MC1 receptor, which becomes unable to be activated by the melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH). This failure to function, leads to pheomelanin in place of eumelanin production within melanocytes. Thereby, a Black horse exhibits at least a wildtype C allele, while a Chestnut one carries only T/T genotype. Consequently,

Agouti locus determines whether a horse carrying at least a C allele will be Bay (if it exhibits at least one recessive type 91 allele) or Black (if it carries homozygous 91/91 genotype); there is no effect of

ASIP gene genotype on chestnut-based horses.

ASIP gene genotyping was conducted directly through amplification by PCR of the Exon 3, producing a 102/91-bp fragment. Indeed, a polymorphic 11-bp deletion (rs396813234) allowed to identify the three available genotype set based on the resulting fragments size. The entire (102-bp) nucleotide sequence corresponds to the dominant wildtype allele, here named as “102”, while the 11-bp deletion identifies the mutant recessive allele, here named as “91”. Consequently, the corresponding genotype set for the ASIP gene was 102/102 for the wildtype homozygous dominant, 102/91 for the heterozygous and 91/91 for the homozygous mutant recessive genotypes.

The

ASIP gene genotype distribution exhibited only two horses carrying the wildtype dominant 102/102 genotype (corresponding to 2% of the studied population), while the main part of the population exhibited the recessive 91/91 genotype (62 horses, corresponding to 69% of the analyzed Sarcidano horses) and 26 subjects (29%) resulted heterozygous 102/91. Allele frequency resulted 83% for the recessive 91 allele and 17% for the wildtype 102 allele. Both the loci showed a very low frequency of the wild dominant allele and a very high rate of the mutant recessive type (

Table 1).

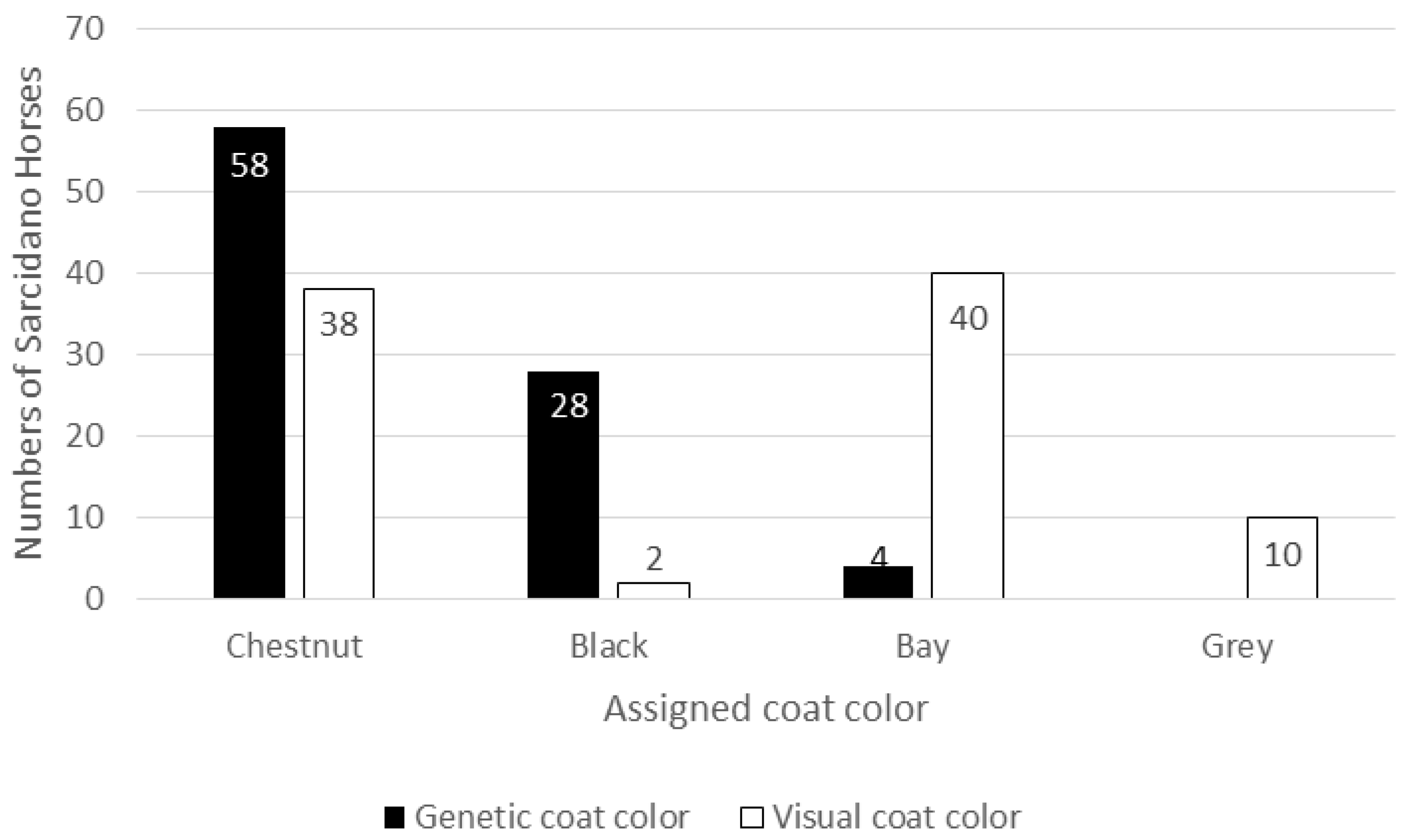

From a genetic point of view more than half the analyzed population resulted Chestnut, well over a quarter were Blacks and a very small portion were Bays. Inconsistencies in visual coat color registration emerged when these results were matched with the phenotypically recorded data, producing an altered distribution of coat colors in the studied population. Indeed, from a phenotypic point of view, the 90 Sarcidano horses were registered as 38 Chestnuts, 40 Bays, only 2 Blacks, and 10 Greys. Grey horses were recorded simply as “grey”, without indication of the possible true color they carried (

Figure 1).

The error rate (calculated as number of incorrectly classified color phenotype on the total number of genetically assigned coat colors) was 54%, including also the Grey horses. This large discrepancy between phenotypic and genetic data highlighted how visual observation can greatly alter the coat color assignment, leading to incorrect registration of the individual data.

Different genotype combinations were found for each coat color, as reported in

Table 2.

These combinations produced some differences in the color shades varying from light to dark within the basic color set, that could be responsible for the inconsistencies in visual color recognition. Chestnuts resulted in the following combinations: T/T+91/91 (59% of the total chestnuts), T/T+102/91 (38%) and T/T+102/102 (3%). The most represent-ed genotype combination in the studied Sarcidano Horses resulted T/T+91/91, producing a liver Chestnut, 7 of which were visually identified and recorded as Bay. Of the 22 horses carrying T/T+102/91 combination, producing a phenotypic lighter-sorrel Chestnuts, 5 were visually registered as Bays. In Black horses too, different genotype combinations were found: 23 were C/T+91/91 (82% of the Blacks), 21 of which were visually registered as Dark Bays, while 5 were C/C+91/91, of which 4 were visually recognized as Bays. This important discrepancy in recognizing the black coat color has different possible explanations. The non-black areas of a Bay horse can range from a light brown to near-black, whereas Black horses can range from a sun-faded brown to jet black. This range of possible shades can make it difficult to pinpoint the exact coat color and create confusion when recording [

13]. Much of the confusion arising because solid black is quite a rare coat color in most horse breeds, therefore many breed standards do not recognize this coat color. Consequently, a very dark horse is always registered as Dark Bay, and many people who fill out individual forms apply this rule to all breeds. However, the genetics of a Bay coat is different from that of a Black one, thus preventing the coat color from being correctly assigned.

In this study only 4 horses were found to be genetically Bays, while visually as many as 40 heads were registered with this coat. All the 4 Bays carried the heterozygous genotype at both the loci, C/T+102/91. The other possible allele combinations for a Bay coat color are C/C+102/102, C/C+102/91 and C/T+102/102, but none of them were found in the studied Sarcidano horses. All these results are summarized in

Table 3.

The found inconsistencies in some visual vs genetic coat color recognition means that a subjective perception of shadings can alter the correct identification, so making visual evaluation not completely reliable, as the same horse could be identified differently by different evaluators. Instead, it is crucial to identify coat colors accurately and to correctly re-port them in the Stud Book, for legal and medical certification, and for the correct prediction of the inheritable coat colors, that can only be achieved with genetic investigation of the MC1R and ASIP loci genotypes.

Another source of confusion concerns Grey horses, as they are born Black, Chestnut or Bay but gradually lose color in their coat as they age [

14]. This means that an adult Grey horse masks its true color and it is not clear what color its off-spring will inherit. However, since Grey locus is epistatic to the above base coat color genes, if a horse is grey, one can be assured that it has at least one Gray parent, but it is impossible to know what color its foals will be, without knowing what genetic color they carry [

15]. The same can be said also for Chestnuts and Bays. In-deed, Chestnuts horses, although are surely carriers of the T/T genotype at the MC1R locus, do not externally show which genotype they have at the ASIP locus; therefore, they can generate offspring of any coat color base, depending on the partner’s genotype.

Even Bay horses do not display the genotype they carry at the ASIP locus and are consequently able to transmit different variants of ASIP alleles: a homozygous 102/102 horse will necessarily pass on the 102-allele to its offspring, while a heterozygous horse (102/91) will have a 50% chance of pass on the 102 allele.

Therefore, when the individual coat color is genetically identified, it is possible to know without any doubt, and already from birth, what type of foal each horse will be able to generate, in absence of other color modifiers, as it is in the Sarcidano Horse. From homozygous MC1R and ASIP loci parents (C/C+102/102) all offspring will be Bay. From C/C+102/91 parents, all offspring will be Dark based, but could be both Dark Bay and true Black. From C/T+102/102 parents, offspring will be Bay as they receive homozygous wild type ASIP alleles, diluting black body color, so that they can be visually appear more red or more black depending on coat color tone and different external and individual factors, such as age, environmental conditions, and nutritional status. Finally, from heterozygous C/T+102/91 parents, any color offspring are possible.