Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

24 November 2023

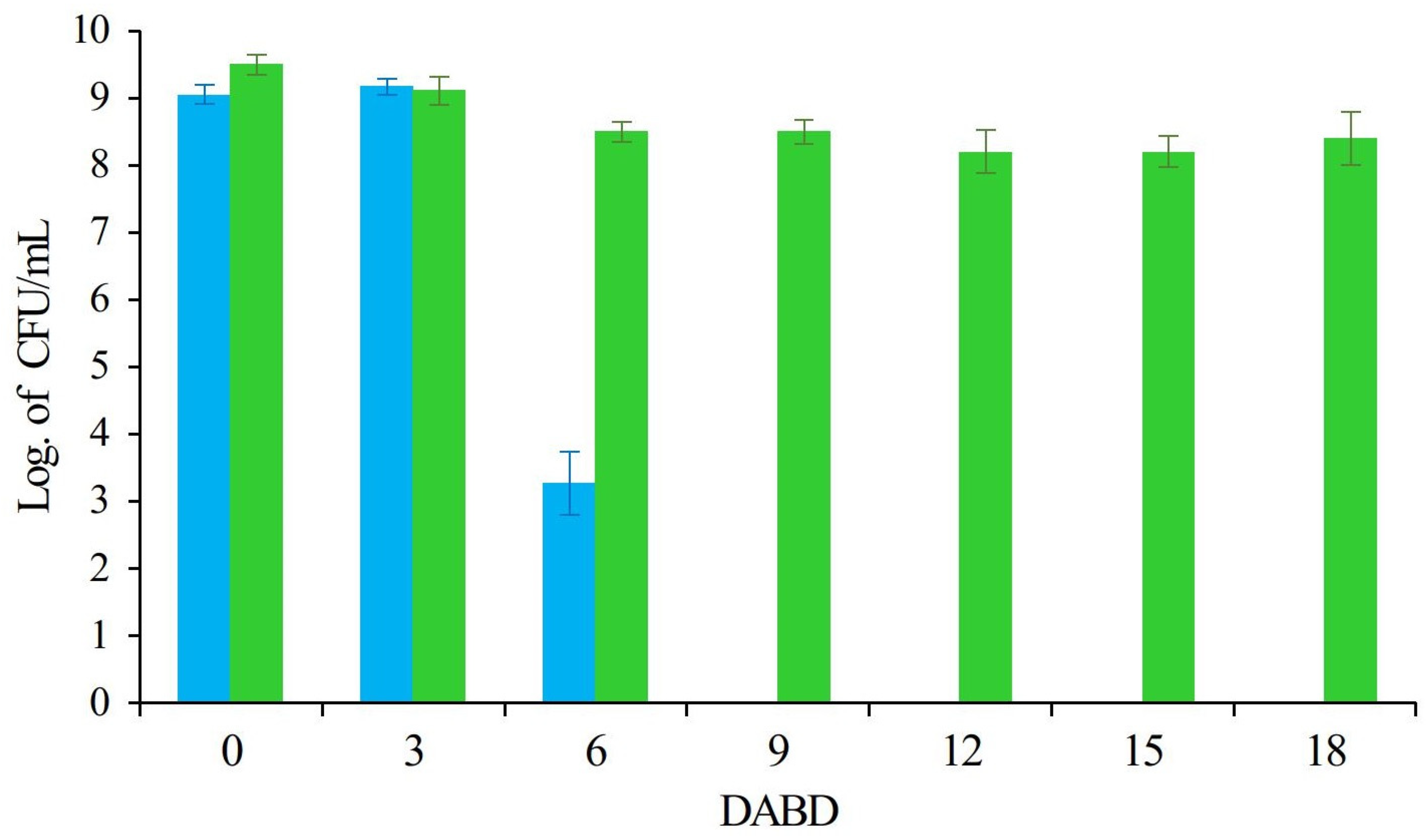

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Conditions that induce VBNC state

2. Bacterial species entering the VBNC state

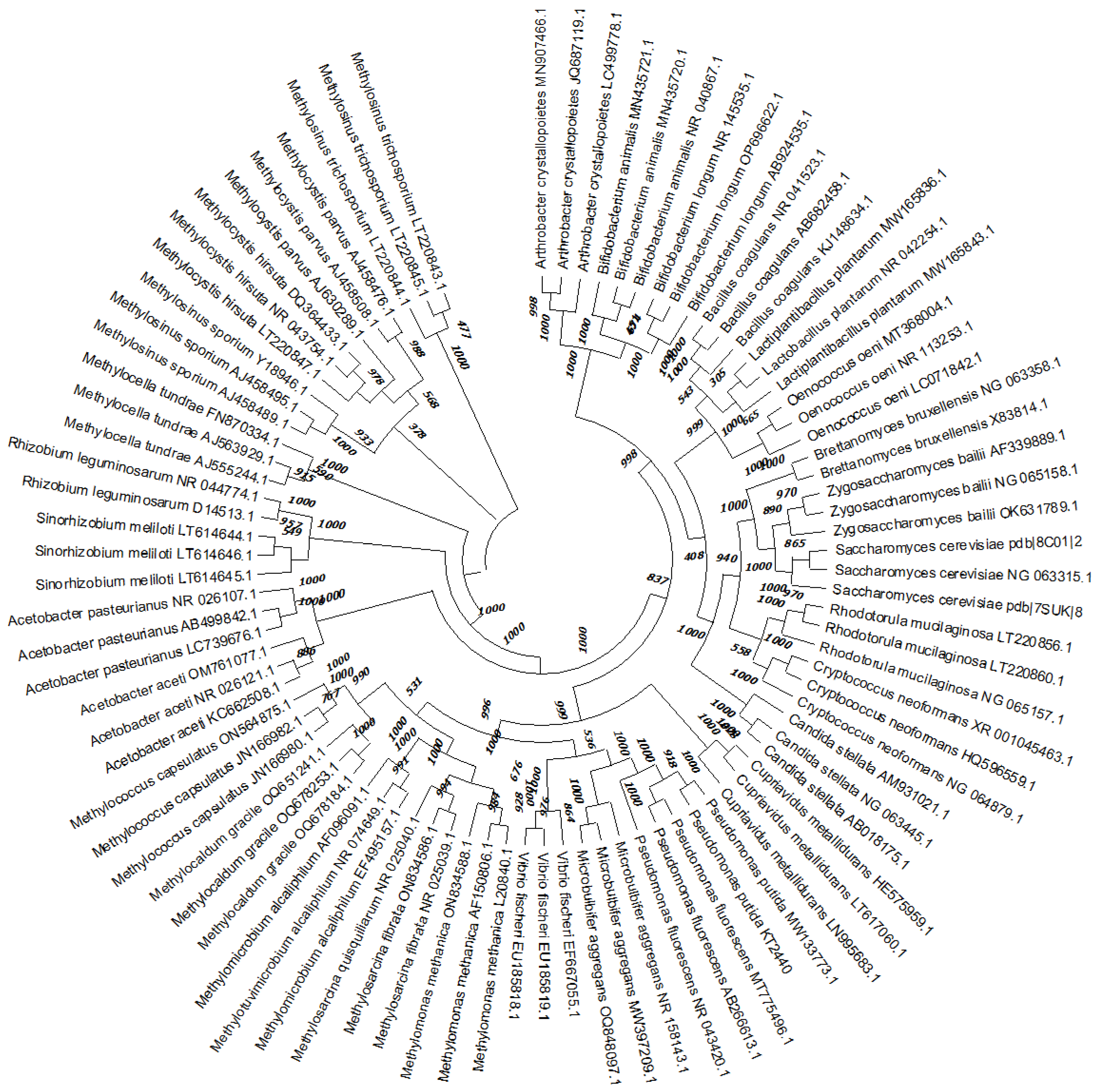

3. The VBNC state in beneficial bacteria

| Group of bacteria | Species | Conditions that induce VBNC state | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteobecteria | Alfaproteobacteria | Acetobacter aceti | Treatment with SO2 at a concentration of 30 and 50 mg/L | [57] |

| Acetobacter pasteurianus | High acid stress during fermentation | [58] | ||

| Methylosinus sporium | Freeze drying and Cryopreservation (liquid nitrogen) |

[36,41] | ||

| Methylosinus trichosporium | ||||

| Methylocystis hirsuta | ||||

| Methylocystis parvus | ||||

| Methylocella tundrae | ||||

| Rhizobium leguminosarum | Cupric sulfate to a concentration of 60 ppm | [59] | ||

| Sinorhizobium meliloti | Incubating at 25°C in tap water from The University of North Carolina at Charlote and tap water from The University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, Center of Marine Biotechnology. Incubating under anoxic conditions in liquid microcosms Incubation in nitrocellulose filters at a relative humidity of 22% for three days at 20°C in the dark. |

[12,60,61] | ||

| Betaproteobacteria | Cupriavidus metallidurans | Incubation into the artificial soil at 30 °C for 12 days, without any C source or H2O | [60] | |

| Gamaproteobacteria | Methylomonas methanica | Lyophilization and Cryopreservation (liquid nitrogen) |

[36,41] | |

| Methylosarcina fibrata | ||||

| Methylocaldum gracile | ||||

| Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum | ||||

| Methylococcus capsulatus | ||||

| Microbulbifer aggregans | Incubation in modified artificial seawater (ASW) by 4 h at 30°C | [61] | ||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Incubation in saline solution (NaCl 0.9% w/v) at 37°C | [62] | ||

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | Desiccation at 30°C and 50% relative humidity | [4] | ||

| Vibrio fischeri | Incubation at 22°C in nutrient-limited artificial seawater (ASW) |

[63] | ||

| Terrabacteria | Actinobacteria | Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis | Storage in fermented foods Refrigerated storage of butter for 4 weeks Microcapsules with full-fat goat milk and inulin-type fructans |

[64,65,66] |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Storage in fermented foods | [64] | ||

|

Arthrobacter albidus. reclassified as Sinomonas albida |

absence of proteins Rpf (resuscitation promoting factor) in the culture medium |

[65,66] | ||

| Firmicutes | Bacillus coagulans | Incubation at pH 2 for 24 hours and subsequent incubation at 140°C for 5 min | [67] | |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Treatment for 30 min at 100 °C or with 1 mol/L HCl Incubation in beer at 0°C temperature |

[31] | ||

| Oenococcus oeni | Sulfur dioxide and histidine decarboxylase activity in wines | [57] | ||

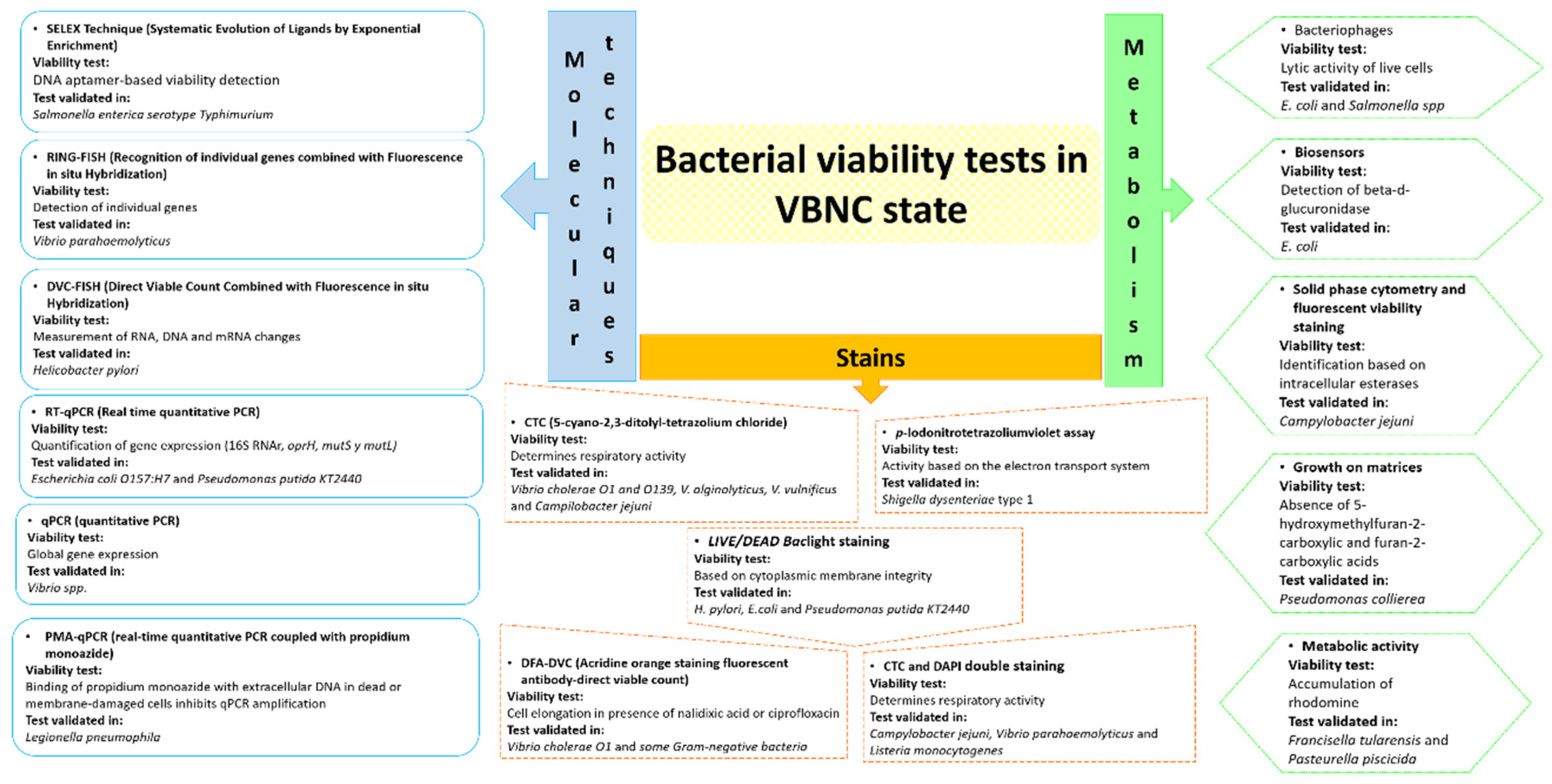

4. Techniques to evaluate bacterial viability in the VBNC state

5. What happens during the VBNC state?

6. Proteomics and transcriptomics of bacterial cells in VBNC state

7. Resuscitation of bacteria under VBNC state

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oliver, J.D. The Viable but Nonculturable State and cellular resuscitation. Microbial biosystems: New frontiers 2000, 723–730.

- Oliver, J.D. The Viable but Nonculturable State in Bacteria. Journal of Microbiology 2005, 43, 93–100.

- Trevors, J.T. Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) Bacteria: Gene expression in planktonic and biofilm cells. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2011, 86, 266–273. [CrossRef]

- Pazos-Rojas, L.A.; Muñoz-Arenas, L.C.; Rodríguez-Andrade, O.; López-Cruz, L.E.; López-Ortega, O.; Lopes-Olivares, F.; Luna-Suarez, S.; Baez, A.; Morales-García, Y.E.; Quintero-Hernández, V.; et al. Desiccation-Induced Viable but Nonculturable state in Pseudomonas putida KT2440, a survival strategy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219554. [CrossRef]

- Gunasekera, T.S.; Sørensen, A.; Attfield, P.V.; Sørensen, S.J.; Veal, D.A. Inducible gene expression by nonculturable bacteria in milk after pasteurization. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68, 1988–1993. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, E.; O’Byrne, C.; Oliver, J.D. Effect of weak acids on Listeria monocytogenes survival: Evidence for a Viable but Nonculturable state in response to low pH. Food Control 2009, 20, 1141–1144. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-S.; Roberts, N.; Singleton, F.L.; Attwell, R.W.; Grimes, D.J.; Colwell, R.R. Survival and viability of nonculturable Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae in the estuarine and marine environment. Microb Ecol 1982, 8, 313–323. [CrossRef]

- Barcina, I.; González, J.M.; Iriberri, J.; Egea, L. Effect of visible light on progressive dormancy of Escherichia coli cells during the survival process in natural fresh water. Appl Environ Microbiol 1989, 55, 246–251. [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.M.; Evison, L.M. Sunlight and the survival of enteric bacteria in natural waters. Journal of Applied Bacteriology 1991, 70, 265–274. [CrossRef]

- Trainor, V.C.; Udy, R.K.; Bremer, P.J.; Cook, G.M. Survival of Streptococcus pyogenes under stress and starvation. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1999, 176, 421–428. [CrossRef]

- Rollins, D.M.; Colwell, R.R. Viable but Nonculturable Stage of Campylobacter jejuni and its role in survival in the natural aquatic environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 1986, 52, 531–538. [CrossRef]

- Vriezen, J.A.; De Bruijn, F.J.; Nüsslein, K.R. Desiccation induces Viable but non-culturable cells in Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. AMB Expr 2012, 2, 6. [CrossRef]

- Bej, A.K.; Mahbubani, M.H.; Atlas, R.M. Detection of viable Legionella pneumophila in water by Polymerase Chain Reaction and gene probe methods. Appl Environ Microbiol 1991, 57, 597–600. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Yeager, R.; McFeters, G.A. Assessment of in vivo revival, growth, and pathogenicity of Escherichia coli strains after copper-and chlorine-induced injury. Appl Environ Microbiol 1986, 52, 832–837. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.; Huq, A.; Xu, B.; Madeira, F.J.; Colwell, R.R. Effect of alum on free-living and copepod-associated Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997, 63, 3323–3326. [CrossRef]

- Mason, D.J.; Power, E.G.; Talsania, H.; Phillips, I.; Gant, V.A. Antibacterial action of ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1995, 39, 2752–2758. [CrossRef]

- Fakruddin, Md.; Mannan, K.S.B.; Andrews, S. Viable but Nonculturable Bacteria: Food Safety and Public Health Perspective. ISRN Microbiology 2013, 2013, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Shleeva, M.; Mukamolova, G.V.; Young, M.; Williams, H.D.; Kaprelyants, A.S. Formation of ‘Non-Culturable’ cells of Mycobacterium smegmatis in stationary phase in response to growth under suboptimal conditions and their Rpf-mediated resuscitation. Microbiology 2004, 150, 1687–1697. [CrossRef]

- Young, D.B.; Gideon, H.P.; Wilkinson, R.J. Eliminating latent tuberculosis. Trends in Microbiology 2009, 17, 183–188. [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.R.; Actor, J.K.; Sepulveda, E.; Hunter, R.L.; Jagannath, C. Identification of Viable and Non-Viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mouse organs by directed RT-PCR for antigen 85B mRNA. Microbial Pathogenesis 2000, 28, 335–342. [CrossRef]

- Magariños, B.; Romalde, J.L.; Barja, J.L.; Toranzo, A.E. Evidence of a dormant but infective state of the fish pathogen Pasteurella piscicida in seawater and sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994, 60, 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Biosca, E.G.; Amaro, C.; Marco-Noales, E.; Oliver, J.D. Effect of low temperature on starvation-survival of the Eel pathogen Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996, 62, 450–455. [CrossRef]

- Banin, E.; Israely, T.; Kushmaro, A.; Loya, Y.; Orr, E.; Rosenberg, E. Penetration of the coral-bleaching bacterium Vibrio shiloi into Oculina patagonica. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000, 66, 3031–3036. [CrossRef]

- Israely, T.; Banin, E.; Rosenberg, E. Growth, differentiation and death of Vibrio shiloi in coral tissue as a function of seawater temperature. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2001, 24, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Grey, B.E.; Steck, T.R. The Viable But Nonculturable State of Ralstonia solanacearum may be involved in long-term survival and plant infection. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001, 67, 3866–3872. [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, R.; Russi, P.; Mara, P.; Mara, H.; Peyrou, M.; De León, I.P.; Gaggero, C. Xanthomonas axonopodis Pv. citri enters the VBNC state after copper treatment and retains its virulence. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2009, 298, 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Ordax, M.; Biosca, E.G.; Wimalajeewa, S.C.; López, M.M.; Marco-Noales, E. Survival of Erwinia amylovora in mature apple fruit calyces through the Viable but Nonculturable (VBNC) state. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2009, 107, 106–116. [CrossRef]

- Kan, Y.; Jiang, N.; Xu, X.; Lyu, Q.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Walcott, R.; Burdman, S.; Li, J.; Luo, L. Induction and Resuscitation of the Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) state in Acidovorax citrulli, the causal agent of bacterial fruit blotch of cucurbitaceous Crops. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1081. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Santos, M.A.; Chambel, L. Thirty years of Viable but Nonculturable state Research: Unsolved Molecular Mechanisms. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 2015, 41, 61–76. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Deng, Y.; Peters, B.M.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Shirtliff, M.E. Transcriptomic analysis on the formation of the viable putative non-culturable state of beer-spoilage Lactobacillus acetotolerans. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 36753. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Peters, B.M.; Deng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shirtliff, M.E. Study on spoilage capability and VBNC state formation and recovery of Lactobacillus plantarum. Microbial Pathogenesis 2017, 110, 257–261. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Shirtliff, M.E.; Xu, Z.; Peters, B.M. Discovery and control of culturable and Viable but Non-Culturable cells of a distinctive Lactobacillus harbinensis strain from spoiled beer. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 11446. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Fu, J.; Yan, M.; Chen, D.; Zhang, L. The novel loop-mediated isothermal amplification based confirmation methodology on thebacteria in Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) state. Microbial Pathogenesis 2017, 111, 280–284. [CrossRef]

- Daranas, N.; Bonaterra, A.; Francés, J.; Cabrefiga, J.; Montesinos, E.; Badosa, E. Monitoring viable cells of the biological control agent Lactobacillus plantarum PM411 in aerial plant surfaces by means of a strain-specific viability quantitative PCRmethod. Appl Environ Microbiol 2018, 84, e00107-18. [CrossRef]

- Santander, R.D.; Figàs-Segura, À.; Biosca, E.G. Erwinia amylovora catalases KatA and KatG are virulence factors and delay the starvation-induced Viable but Non-culturable (VBNC) response. Molecular Plant Pathology 2018, 19, 922–934. [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Pan, H.; Yang, D.; Rao, L.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X. Induction, detection, formation, and esuscitation of Viable but Non-culturable state microorganisms. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2020, 19, 149–183. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-H.; Ahmad, W.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Chen, J.; Austin, B. Viable but Nonculturable bacteria and their resuscitation: Implications for cultivating uncultured marine microorganisms. Mar Life Sci Technol 2021, 3, 189–203. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.D. Recent findings on the Viable but Nonculturable state in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2010, 34, 415–425. [CrossRef]

- Dobereiner, J.; Urquiaga, S. Alternatives for Nitrogen nutrition of crops in Tropical agriculture. Nitrogen Economy in Tropical Soils: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Nitrogen Economy in Tropical Soils, held in Trinidad, W.I., January 9–14, 1994.

- Crowley, D.E.; Wang, Y.C.; Reid, C.P.P.; Szaniszlo, P.J. Mechanisms of iron acquisition from siderophores by microorganisms and plants. In Developments in Plant and Soil Sciences; Srpinger, 1991; pp. 179–198 ISBN 978-94-010-5455-3.

- Hoefman, S.; Van Hoorde, K.; Boon, N.; Vandamme, P.; De Vos, P.; Heylen, K. Survival or revival:long-term preservation induces a reversible Viable but Non-Culturable state in methane-oxidizing bacteria. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34196. [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.O. Beneficial bacteria of agricultural importance. Biotechnol Lett 2010, 32, 1559–1570. [CrossRef]

- Lugtenberg, B.; Kamilova, F. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 63, 541–556. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, R.; Ali, S.; Amara, U.; Khalid, R.; Ahmed, I. Soil Beneficial bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion: a review. Ann Microbiol 2010, 60, 579–598. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Induced Systemic Resistance by beneficial microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 347–375. [CrossRef]

- Fira, D.; Dimkić, I.; Berić, T.; Lozo, J.; Stanković, S. Biologicalcontrol of plant pathogens by Bacillus species. Journal of Biotechnology 2018, 285, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Brierley, C.L. Microbiological mining. Sci Am 1982, 247, 44–53. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.; Usmani, S.; Singh, B.R.; Musarrat, J. Significance of Bacillus subtilis strain SJ-101 as a bioinoculant for concurrent plant growth promotion and Nickel accumulation in Brassica juncea. Chemosphere 2006, 64, 991–997. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Chen, J.; Shim, H.; Bai, Z. New advances in Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria for bioremediation. Environment International 2007, 33, 406–413. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Lactic acid bacteria as functional starter cultures for the food fermentation industry. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2004, 15, 67–78. [CrossRef]

- Chemier, J.A.; Fowler, Z.L.; Koffas, M.A.G. Trends in microbial synthesis of natural products and biofuels. In Advances in Enzymology - and Related Areas of Molecular Biology; Toone, E.J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Vol. 76, pp. 151–217 ISBN 978-0-470-39288-1.

- Tejero-Sariñena, S.; Barlow, J.; Costabile, A.; Gibson, G.R.; Rowland, I. In vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of a range of probiotics against pathogens: evidence for the effects of organic acids. Anaerobe 2012, 18, 530–538. [CrossRef]

- Liévin-Le Moal, V.; Servin, A.L. The front line of enteric host defense against unwelcome intrusion of harmful microorganisms: mucins, antimicrobial peptides, and microbiota. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006, 19, 315–337. [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, C.; Saeed, R.; Bamias, G.; Arseneau, K.O.; Pizarro, T.T.; Cominelli, F. Probiotics promote gut health through stimulation of epithelial innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 454–459. [CrossRef]

- Lonvaud-Funel, A. Lactic Acid Bacteria in the quality improvement and depreciation of wine. In Lactic Acid Bacteria: Genetics, Metabolism and Applications; Konings, W.N., Kuipers, O.P., In ’T Veld, J.H.J.H., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1999; pp. 317–331 ISBN 978-90-481-5312-1.

- Virdis, C.; Sumby, K.; Bartowsky, E.; Jiranek, V. Lactic Acid Bacteria in wine: technological advances and evaluation of their functional role. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 612118. [CrossRef]

- Millet, V.; Lonvaud-Funel, A. The Viable but Non-Culturable state of wine microorganisms during storage. Lett Appl Microbiol 2000, 30, 136–141. [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Han, C.; Xu, J.; Liang, X. Toxin-antitoxin HicAB regulates the formation of persister cells responsible for the acid stress resistance in Acetobacter pasteurianus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105, 725–739. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.; Pham, D.; Steck, T.R. The Viable-but-Nonculturable condition is induced by copper in Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Rhizobium leguminosarum. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999, 65, 3754–3756. [CrossRef]

- Giagnoni, L.; Arenella, M.; Galardi, E.; Nannipieri, P.; Renella, G. Bacterial culturability and the Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) state studied by a proteomic approach using an artificial soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2018, 118, 51–58. [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, G.; Diyana, T.; Lau, N.-S. Metabolic strategies of dormancy of a marine bacterium Microbulbifer aggregans CCB-MM1: its alternative electron transfer chain and sulfate-reducing Pathway. Genomics 2022, 114, 443–455. [CrossRef]

- Arana, I.; Muela, A.; Orruño, M.; Seco, C.; Garaizabal, I.; Barcina, I. Effect of temperature and starvation upon survival strategies of Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0: comparison with Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2010, 74, 500–509. [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, N.; Ravel, J.; Straube, W.L.; Hill, R.T.; Colwell, R.R. Entry of Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio fischeri into the Viable but Nonculturable state. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2002, 93, 108–116. [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, S.J.; Ahokoski, H.; Reinikainen, J.P.; Gueimonde, M.; Nurmi, J.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Salminen, S.J. Degradation of 16S rRNA and attributes of viability of Viable but Nonculturable probiotic bacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol 2008, 46, 693–698. [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Shen, X.; Ding, L.; Yokota, A. Study on the flocculability of the Arthrobacter sp., an actinomycete resuscitated from the VBNC state. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 28, 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Xu, J. Description of Sinomonas soli sp. nov., reclassification of Arthrobacter echigonensis and Arthrobacter albidus (Ding et al. 2009) as Sinomonas echigonensis comb. nov. and Sinomonas albida comb. nov., respectively, and emended description of the Genus Sinomonas. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2012, 62, 764–769. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Majeed, S.; Nagabhushanam, K.; Punnapuzha, A.; Philip, S.; Mundkur, L. Rapid assessment of Viable but Non-Culturable Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 in commercial formulations using flow cytometry. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192836. [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1987. [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Phylogenies and the comparative method. The American Society of Naturalists 1985, 125, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Barrao, C.; Saad, M.M.; Chappuis, M.-L.; Boffa, M.; Perret, X.; Ortega Pérez, R.; Barja, F. Proteome analysis of Acetobacter pasteurianus during acetic acid fermentation. Journal of Proteomics 2012, 75, 1701–1717. [CrossRef]

- Semrau, J.D.; DiSpirito, A.A.; Yoon, S. Methanotrophs and copper. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2010, 34, 496–531. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, C.; Smith, T.J.; Murrell, J.C.; Xing, X.-H. Methanotrophs: multifunctional bacteria with promising applications in environmental bioengineering. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2010, 49, 277–288. [CrossRef]

- Wendlandt, K.-D.; Stottmeister, U.; Helm, J.; Soltmann, B.; Jechorek, M.; Beck, M. The potential of methane-oxidizing bacteria for applications in environmental Biotechnology. Eng. Life Sci. 2010, NA-NA. [CrossRef]

- Coba De La Peña, T.; Fedorova, E.; Pueyo, J.J.; Lucas, M.M. The symbiosome: legume and rhizobia co-evolution toward a Nitrogen-Fixing organelle? Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 8, 2229. [CrossRef]

- Moawad, H.; Abd el-Rahim, W.M.; Abd el-Aleem, D.; Abo Sedera, S.A. Persistence of two Rhizobium etli inoculant strains in clay and silty loam soils. J. Basic Microbiol. 2005, 45, 438–446. [CrossRef]

- Abdelkhalek, A.; Yassin, Y.; Abdel-Megeed, A.; Abd-Elsalam, K.; Moawad, H.; Behiry, S. Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae-mediated silver nanoparticles for controlling bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV) infection in faba bean plants. Plants 2022, 12, 45. [CrossRef]

- Mergeay, M.; Monchy, S.; Vallaeys, T.; Auquier, V.; Benotmane, A.; Bertin, P.; Taghavi, S.; Dunn, J.; Van Der Lelie, D.; Wattiez, R. Ralstonia metallidurans, a bacterium specifically adapted to toxic metals: towards a catalogue of metal-responsive genes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2003, 27, 385–410. [CrossRef]

- Diels, L.; Van Roy, S.; Taghavi, S.; Van Houdt, R. From industrial sites to environmental applications with Cupriavidus metallidurans. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2009, 96, 247–258. [CrossRef]

- Lal, D.; Nayyar, N.; Kohli, P.; Lal, R. Cupriavidus metallidurans: a modern alchemist. Indian J Microbiol 2013, 53, 114–115. [CrossRef]

- Reith, F.; Etschmann, B.; Grosse, C.; Moors, H.; Benotmane, M.A.; Monsieurs, P.; Grass, G.; Doonan, C.; Vogt, S.; Lai, B.; et al. Mechanisms of gold biomineralization in the bacterium Cupriavidus metallidurans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 17757–17762. [CrossRef]

- Iguchi, H.; Yurimoto, H.; Sakai, Y. Interactions of methylotrophs with plants and other heterotrophic bacteria. Microorganisms 2015, 3, 137–151. [CrossRef]

- Semrau, J.D.; DiSpirito, A.A.; Vuilleumier, S. Facultative methanotrophy: false leads, true results, and suggestions for future research: facultative methanotrophy. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2011, 323, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.; Hoefman, S.; Kerckhof, F.-M.; Boon, N.; De Vos, P.; De Baets, B.; Heylen, K.; Waegeman, W. Exploration and prediction of interactions between methanotrophs and heterotrophs. Research in Microbiology 2013, 164, 1045–1054. [CrossRef]

- Liebner, S.; Zeyer, J.; Wagner, D.; Schubert, C.; Pfeiffer, E.-M.; Knoblauch, C. Methane oxidation associated with submerged brown mosses reduces methane emissions from siberian polygonal tundra: Moss-associated methane oxidation. Journal of Ecology 2011, 99, 914–922. [CrossRef]

- Moh, T.H.; Furusawa, G.; Amirul, A.A.-A. Microbulbifer aggregans sp. nov., isolated from estuarine sediment from a mangrove forest. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2017, 67, 4089–4094. [CrossRef]

- Komarnisky, L.A.; Christopherson, R.J.; Basu, T.K. Sulfur: its clinical and toxicologic aspects. Nutrition 2003, 19, 54–61. [CrossRef]

- Spiers, A.J.; Buckling, A.; Rainey, P.B. The Causes of Pseudomonas diversity. Microbiology 2000, 146, 2345–2350. [CrossRef]

- Preston, G.M. Plant perceptions of plant growth-promoting Pseudomonas. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2004, 359, 907–918. [CrossRef]

- Bunker, S.T.; Bates, T.C.; Oliver, J.D. Effects of temperature on detection of plasmid or chromosomally encoded Gfp -and Lux-labeled Pseudomonas fluorescens in Soil. Environ. Biosafety Res. 2004, 3, 83–90. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.L.; Hirkala, D.L.; Nelson, L.M. Efficacy of Pseudomonas fluorescens for control of mucor rot of apple during commercial storage and potential modes of action. Can. J. Microbiol. 2018, 64, 420–431. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Ent, S.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Jasmonate signaling in plant interactions with resistance-inducing beneficial microbes. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1581–1588. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhong, T.; Chen, K.; Du, M.; Chen, G.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Zalán, Z.; Takács, K.; Kan, J. Antifungal activity of volatile organic compounds produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens ZX and potential biocontrol of blue mold decay on postharvest citrus. Food Control 2021, 120, 107499. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-González, M.I.; Ramos-Díaz, M.A.; Ramos, J.L. Chromosomal gene capture mediated by the Pseudomonas putida TOL catabolic plasmid. J Bacteriol 1994, 176, 4635–4641. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Urgel, M..; Kolter, R..; Ramos, J.-L.. Root colonization by Pseudomonas putida: love at first sight. Microbiology 2002, 148, 341–343. [CrossRef]

- Matilla, M.A.; Ramos, J.L.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Doornbos, R.; Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M.; Ramos-González, M.I. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 causes induced systemic resistance and changes in Arabidopsis root exudation. Environ Microbiol Rep 2010, 2, 381–388. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Romero, D.; Morales-García, Y.-E.; Hernández-Tenorio, A.-L.; Netzahuatl-Muñoz, A.-R. Pseudomonas putida estimula el crecimiento de maíz en función de la temperatura. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias 2017, 4,80-88.

- Morales-García; Baez A; Quintero-Hernández V; Molina-Romero D; Rivera-Urbalejo A.P.; Pazos-Rojas L.A., L.A.; Muñoz-Rojas J. Bacterial mixtures, the future generation of inoculants for sustainable crop production. In Field Crops: Sustainable Management by PGPR, Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2019; Vol. 23, pp. 11–44 ISBN 978-3-030-30925-1.

- Pazos-Rojas, L.A.; Marín-Cevada, V.; García, Y.E.M.; Baez, A.; Villalobos-López, M.A.; Pérez-Santos, M. Uso de microorganismos benéficos para reducir los daños causados por la revolución verde. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias 2016, 3, 72–85.

- Meighen, E.A. Molecular biology of bacterial bioluminescence. MICROBIOL. REV. 1991, 55.

- Jones, B.W.; Nishiguchi, M.K. Counterillumination in the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes berry (Mollusca: Cephalopoda). Marine Biology 2004, 144, 1151–1155. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Ruby, E.G. Effect of the Squid Host on the Abundance and Distribution of symbiotic Vibrio fischeri in nature. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994, 60, 1565–1571. [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Hirose, T.; Yokota, A. Four novel Arthrobacter species isolated from filtration substrate. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SYSTEMATIC AND EVOLUTIONARY MICROBIOLOGY 2009, 59, 856–862. [CrossRef]

- Soomro, A.H.; Masud, T.; Anwaar, K. Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) in food preservation and human health–a review. Pakistan J. of Nutrition 2001, 1, 20–24. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Abhari, K.; Eş, I.; Soares, M.B.; Oliveira, R.B.A.; Hosseini, H.; Rezaei, M.; Balthazar, C.F.; Silva, R.; Cruz, A.G.; et al. Interactions between probiotics and pathogenic microorganisms in hosts and foods: a review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2020, 95, 205–218. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Nagabhushanam, K.; Natarajan, S.; Sivakumar, A.; Eshuis-de Ruiter, T.; Booij-Veurink, J.; De Vries, Y.P.; Ali, F. Evaluation of genetic and phenotypic consistency of Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856: a commercial probiotic strain. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 32, 60. [CrossRef]

- Saw, C.-Y.; Chang, T.-J.; Chen, P.-Y.; Dai, F.-J.; Lau, Y.-Q.; Chen, T.-Y.; Chau, C.-F. Presence of Bacillus coagulans spores and vegetative cells in rat intestine and feces and their physiological effects. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2019, 83, 2327–2333. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.Kr.; Srivastava, R. Resuscitation promoting factors: a family of microbial proteins in survival and resuscitation of dormant Mycobacteria. Indian J Microbiol 2012, 52, 114–121. [CrossRef]

- Seddik, H.A.; Bendali, F.; Gancel, F.; Fliss, I.; Spano, G.; Drider, D. Lactobacillus plantarum and its probiotic and food potentialities. Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot. 2017, 9, 111–122. [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S.D.; Franco, B.D.G.D.M. Lactobacillus plantarum: characterization of the species and application in food production. Food Reviews International 2010, 26, 205–229. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.S.; Todorov, S.D.; Ivanova, I.V.; Belguesmia, Y.; Choiset, Y.; Rabesona, H.; Chobert, J.-M.; Haertlé, T.; Franco, B.D.G.M. Characterization of a two-peptide plantaricin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum MBSa4 isolated from brazilian salami. Food Control 2016, 60, 103–112. [CrossRef]

- Surono, I.S.; Collado, M.C.; Salminen, S.; Meriluoto, J. Effect of glucose and incubation temperature on metabolically active Lactobacillus plantarum from dadih in removing microcystin-LR. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2008, 46, 502–507. [CrossRef]

- Tonon, T.; Lonvaud-Funel, A. Metabolism of arginine and its positive effect on growth and revival of Oenococcus oeni: degradation of arginine by Oenococcus oeni. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2000, 89, 526–531. [CrossRef]

- Bech-Terkilsen, S.; Westman, J.O.; Swiegers, J.H.; Siegumfeldt, H. Oenococcus oeni , a species born and moulded in wine: a critical review of the stress impacts of wine and the physiological responses. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2020, 26, 188–206. [CrossRef]

- Conway, T.; K., G. Microarray expression profiling: capturing a genome-wide portrait of the transcriptome: genome-wide portrait. Molecular Microbiology 2003, 47, 879–889. [CrossRef]

- Laalami, S.; Zig, L.; Putzer, H. Initiation of mRNA decay in bacteria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 1799–1828. [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.S.; Oliver, J.D. Induction of carbon starvation-induced proteins in Vibrio vulnificus. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994, 60, 3653–3659. [CrossRef]

- McGovern, V.P.; Oliver, J.D. Induction of cold-responsive proteins in Vibrio vulnificus. J Bacteriol 1995, 177, 4131–4133. [CrossRef]

- Federighi, M.; Tholozan, J.L.; Cappelier, J.M.; Tissier, J.P.; Jouve, J.L. Evidence of non-coccoid Viable but Non-culturable Campylobacter jejuni cells in microcosm water by direct viable count, CTC-DAPI double staining, and scanning electron microscopy. Food Microbiology 1998, 15, 539–550. [CrossRef]

- Yaron, S.; Matthews, K.R. A Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction assay for detection of Viable Escherichia coli O157:H7: investigation of specific target genes. J Appl Microbiol 2002, 92, 633–640. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Le Saux, M.; Hervio-Heath, D.; Loaec, S.; Colwell, R.R.; Pommepuy, M. Detection of cytotoxin-hemolysin mRNA in Nonculturable populations of environmental and clinical Vibrio vulnificus strains in artificial seawater. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68, 5641–5646. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Shahamat, M.; Kirchman, P.A.; Russek-Cohen, E.; Colwell, R.R. Methionine uptake and cytopathogenicity of Viable but Nonculturable Shigella dysenteriae type 1. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994, 60, 3573–3578. [CrossRef]

- Day, A.P.; Oliver, J.D. Changes in membane fatty acid composition during entry of Vibrio vulnificus into the Viable But Non Culturable state. 2004, 42, 69–73.

- Signoretto, C.; Lleò, M.D.M.; Canepari, P. Modification of the Peptidoglycan of Escherichia coli in the Viable But Nonculturable State. Current Microbiology 2002, 44, 125–131. [CrossRef]

- Signoretto, C.; Del Mar Lleò, M.; Tafi, M.C.; Canepari, P. Cell wall chemical composition of Enterococcus faecalis in the Viable but Nonculturable state. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000, 66, 1953–1959. [CrossRef]

- Mascher, T.; Helmann, J.D.; Unden, G. Stimulus perception in bacterial signal-transducing histidine kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2006, 70, 910–938. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, T.; Scheide, D. The respiratory complex I of bacteria, archaea and eukarya and its module common with membrane-bound multisubunit hydrogenases. FEBS Letters 2000, 479, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Postnikova, O.A.; Shao, J.; Mock, N.M.; Baker, C.J.; Nemchinov, L.G. Gene expression profiling in Viable but Nonculturable (VBNC) cells of Pseudomonas syringae pv. Syringae. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Hua J.; Ho B. Is the coccoid form of Helicobacter pylori Viable? Microbios 1996, 87, 103–112.

- Tsugawa, H.; Suzuki, H.; Nakagawa, I.; Nishizawa, T.; Saito, Y.; Suematsu, M.; Hibi, T. Alpha-kKetoglutarate oxidoreductase, an essential salvage enzyme of energy metabolism, in coccoid form of Helicobacter pylori. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2008, 376, 46–51. [CrossRef]

- Asakura, H.; Panutdaporn, N.; Kawamoto, K.; Igimi, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Makino, S. Proteomic characterization of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the oxidation-induced Viable but Non-Culturable state. Microbiology and Immunology 2007, 51, 875–881. [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.; Ohashi, E.; Ren, H.; Hayashi, T.; Endo, H. Isolation and characterization of a cold-induced nonculturable suppression mutant of Vibrio vulnificus. Microbiological Research 2007, 162, 130–138. [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, T.; Ghosh, A.; Pazhani, G.P.; Shinoda, S. Current perspectives on Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) pathogenic bacteria. Front. Public Health 2014, 2. [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-J.; Chen, S.-Y.; Lin, I.-H.; Chang, C.-H.; Wong, H. Change of protein profiles in the induction of the Viable but Nonculturable State of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2009, 135, 118–124. [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.; Jane, W.-N.; Wong, H. Association of a d-alanyl- d-alanine carboxypeptidase gene with the formation of aberrantly shaped cells during the induction of Viable but Nonculturable Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79, 7305–7312. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-W.; Chung, C.-H.; Ma, T.-Y.; Wong, H. Roles of alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C (AhpC) in Viable but Nonculturable Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79, 3734–3743. [CrossRef]

- Mongkolsuk, S.; Whangsuk, W.; Vattanaviboon, P.; Loprasert, S.; Fuangthong, M. A Xanthomonas alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C (ahpC) mutant showed an altered peroxide stress response and complex regulation of the compensatory response of peroxide detoxification enzymes. J Bacteriol 2000, 182, 6845–6849. [CrossRef]

- Asakura, H.; Ishiwa, A.; Arakawa, E.; Makino, S.; Okada, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Igimi, S. Gene expression profile of Vibrio cholerae in the cold stress-induced Viable but Non-culturable state. Environmental Microbiology 2007, 9, 869–879. [CrossRef]

- Krebs, S.J.; Taylor, R.K. Nutrient-dependent, rapid transition of Vibrio cholerae to coccoid morphology and expression of the toxin co-regulated pilus in this form. Microbiology 2011, 157, 2942–2953. [CrossRef]

- Patrone, V.; Campana, R.; Vallorani, L.; Dominici, S.; Federici, S.; Casadei, L.; Gioacchini, A.M.; Stocchi, V.; Baffone, W. CadF expression in Campylobacter jejuni strains incubated under low-temperature water microcosm conditions which induce the Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) state. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 103, 979–988. [CrossRef]

- Boaretti, M.; Del Mar Lleo, M.; Bonato, B.; Signoretto, C.; Canepari, P. Involvement of rpoS in the survival of Escherichia coli in the Viable but Non-Culturable state. Environ Microbiol 2003, 5, 986–996. [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, S.E.; Oyston, P.C.F. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 2008, 154, 3609–3623. [CrossRef]

- Grove, A. MarR family transcription factors. Current Biology 2013, 23, R142–R143. [CrossRef]

- López-Lara, L.I.; Pazos-Rojas, L.A.; López-Cruz, L.E.; Morales-García, Y.E.; Quintero-Hernández, V.; De La Torre, J.; Van Dillewijn, P.; Muñoz-Rojas, J.; Baez, A. Influence of rehydration on transcriptome during resuscitation of desiccated Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Ann Microbiol 2020, 70, 54. [CrossRef]

- Gupte, A.R.; De Rezende, C.L.E.; Joseph, S.W. Induction and resuscitation of Viable but Nonculturable Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium DT104. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69, 6669–6675. [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, A.; Li, Y. Characterization and resuscitation of Viable but Nonculturable Vibrio alginolyticus VIB283. Arch Microbiol 2007, 188, 283–288. [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.-C.; Liu, S.-H. Characterization of the low-salinity stress in Vibrio vulnificus. Journal of Food Protection 2008, 71, 416–419. [CrossRef]

- Bates, T.C.; Oliver, J.D. The Viable but Non Culturable state of Kanagawa positive and negative strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Microbiol 2004, 42, 74–79.

- Steinert, M.; Emödy, L.; Amann, R.; Hacker, J. Resuscitation of Viable but Nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997, 63, 2047–2053. [CrossRef]

- García, M.T.; Jones, S.; Pelaz, C.; Millar, R.D.; Abu Kwaik, Y. Acanthamoeba polyphaga Resuscitates Viable Non-culturable Legionella pneumophila after disinfection. Environmental Microbiology 2007, 9, 1267–1277. [CrossRef]

- Sussman, M.; Loya, Y.; Fine, M.; Rosenberg, E. The marine fireworm Hermodice carunculata as a winter reservoir and spring-summer vector for the coral-bleaching pathogen Vibrio shiloi. Environ Microbiol 2003, 5, 250–255. [CrossRef]

- Cappelier, J.M.; Besnard, V.; Roche, S.M.; Velge, P.; Federighi, M. Avirulent Viable But Non Culturable cells of Listeria monocytogenes need the presence of an embryo to be recovered in egg yolk and regain virulence after recovery. Vet. Res. 2007, 38, 573–583. [CrossRef]

- Mukamolova, G.V.; Kaprelyants, A.S.; Kell, D.B. Secretion of an antibacterial factor during resuscitation of dormant cells in Micrococcus luteus cultures held in an extended stationary phase. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1995, 67, 289–295. [CrossRef]

- Mukamolova, G.V.; Kaprelyants, A.S.; Young, D.I.; Young, M.; Kell, D.B. A bacterial cytokine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 8916–8921. [CrossRef]

- Nikitushkin, V.D.; Demina, G.R.; Shleeva, M.O.; Guryanova, S.V.; Ruggiero, A.; Berisio, R.; Kaprelyants, A.S. A product of RpfB and RipA joint enzymatic action promotes the resuscitation of dormant mycobacteria. The FEBS Journal 2015, 282, 2500–2511. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Kong, X.; Han, Y. Proteolytic activity of Vibrio harveyi YeaZ is related with resuscitation on the Viable but Non-Culturable State. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2020, 71, 126–133. [CrossRef]

- Mukamolova, G.V.; Turapov, O.A.; Young, D.I.; Kaprelyants, A.S.; Kell, D.B.; Young, M. A family of autocrine growth factors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: autocrine growth factors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecular Microbiology 2002, 46, 623–635. [CrossRef]

- Freestone, P.P.E.; Haigh, R.D.; Williams, P.H.; Lyte, M. Stimulation of bacterial growth by heat-stable, norepinephrine-induced autoinducers. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1999, 172, 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Woolf, P.D. The catecholamine response to multisystem trauma. Arch Surg 1992, 127, 899. [CrossRef]

- Reissbrodt, R.; Rienaecker, I.; Romanova, J.M.; Freestone, P.P.E.; Haigh, R.D.; Lyte, M.; Tschäpe, H.; Williams, P.H. Resuscitation of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli from the Viable but Nonculturable state by heat-stable enterobacterial autoinducer. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68, 4788–4794. [CrossRef]

- Imazaki, I.; Nakaho, K. Temperature-upshift-mediated revival from the sodium-pyruvate-recoverable Viable but Nonculturable state induced by low temperature in Ralstonia solanacearum: linear regression analysis. J Gen Plant Pathol 2009, 75, 213–226. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Bi, X.; Hao, Y.; Liao, X. Induction of Viable but Nonculturable Escherichia coli O157:H7 by high pressure CO2 and its characteristics. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62388. [CrossRef]

- Abisado, R.G.; Benomar, S.; Klaus, J.R.; Dandekar, A.A.; Chandler, J.R. Bacterial quorum sensing and microbial community interactions. mBio 2018, 9, e02331-17. [CrossRef]

- Hassett, D.J.; Ma, J.; Elkins, J.G.; McDermott, T.R.; Ochsner, U.A.; West, S.E.H.; Huang, C.; Fredericks, J.; Burnett, S.; Stewart, P.S.; et al. Quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls expression of catalase and superoxide dismutase genes and mediates biofilm susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide. Molecular Microbiology 1999, 34, 1082–1093. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Zhong, X.; Xu, L.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Guo, X. Research in Microbiology 2019, 170, 65–73. [CrossRef]

| Type of stress | Example of microorganism | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical parameters | Temperature | Vibrio cholerae incubated in a range of 4 to 6°C | [7] |

| Visible solar and UV radiation | Escherichia coli in microcosm of river water under visible light irradiation | [8] | |

| Osmolarity | E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium in freshwater and seawater | [9] | |

| Chemical parameters | Organic matter | ||

| Nutritional effects. | Streptococcus pyogenes carbon and phosphorus limitation in culture during stationary phase | [10] | |

| Humic acids | E. coli in presence of humic acids significantly decreases the entrance to VBNC status in fresh water but not in seawater | [9] | |

| Aeration | Campylobacter jejuni enters faster into the VBNC state in microcosmos incubated under agitation (3 days), compared to immobile microcosmos (10 days) | [11] | |

| Drying | Sinorhizobium meliloti part of the population enters into the VBNC state with 22% humidity | [12] | |

| P. putida KT2440 enters into the VBNC state under desiccation conditions at 30°C and 50% relative humidity | [4] | ||

| Biocidal agents | Hypochlorite (100ppm) | Legionella pneumophila was detected in culture medium treated with hypochlorite for 10 minutes | [13] |

| Cupper (0.6-1mg/mL) | E. coli ETEC in buffered water at 4 °C produced VBNC cells that maintained their enterotoxigenic activity when reactivated. | [14] | |

| Alum KAI(S04)2 | V. cholerae O1 in artificial seawater with alum, a significant number of cells lost their culturable capacity while keeping viability | [15] | |

| Quinolone and ciprofloxacin | E. coli, exposed to 10-100 times minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), lost the culturable capacity | [16] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).