2.1.1. Circuit Component 1 (Power Source)

The energy-circuit begins with a power supply. For safety and stability, a direct current (DC) power supply with a fixed voltage is commonly used. However, this paper explores the flexibility of the system by considering alternative power sources, such as variable DC supplies and those with different voltage ratings. To accurately model the energy-circuit’s behavior, it is essential to understand the initial current provided by the power supply, as well as the resistance and material properties of the connecting wires. This knowledge allows for a more realistic representation of real-world conditions,

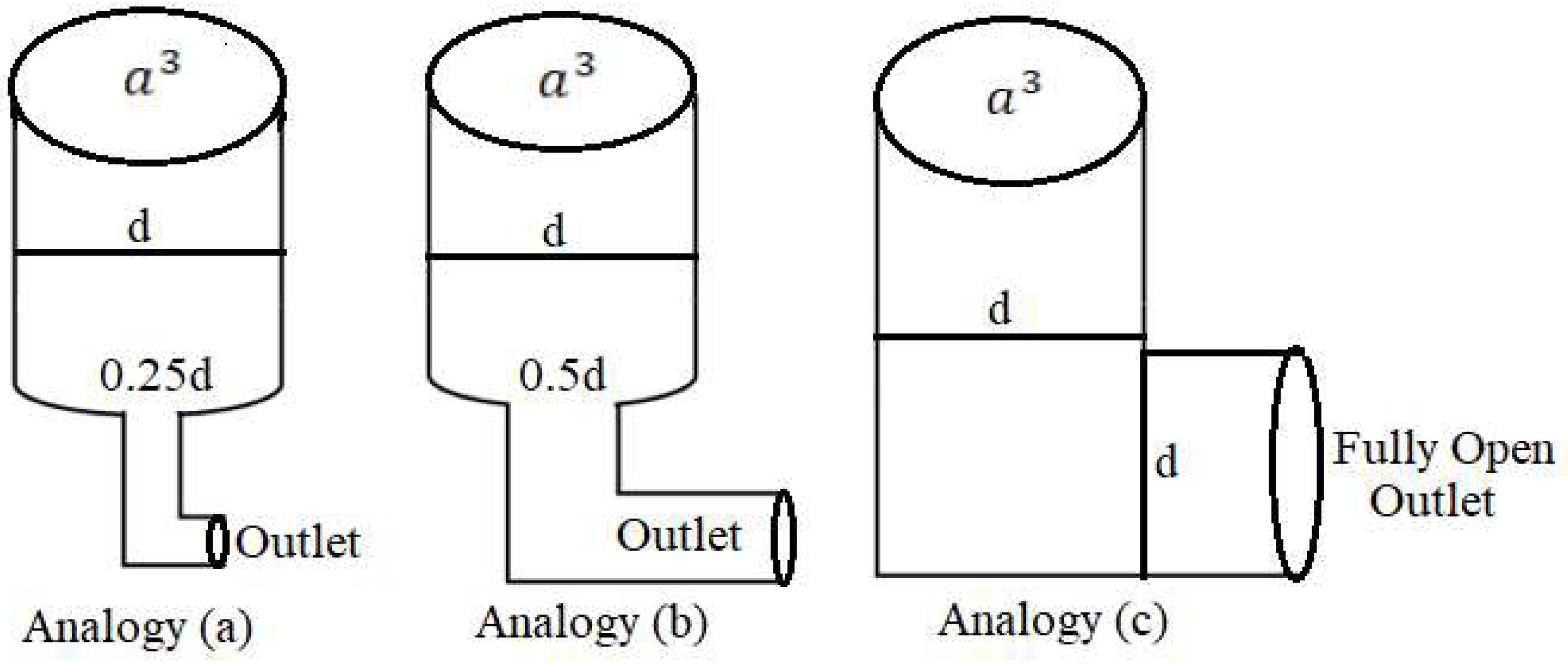

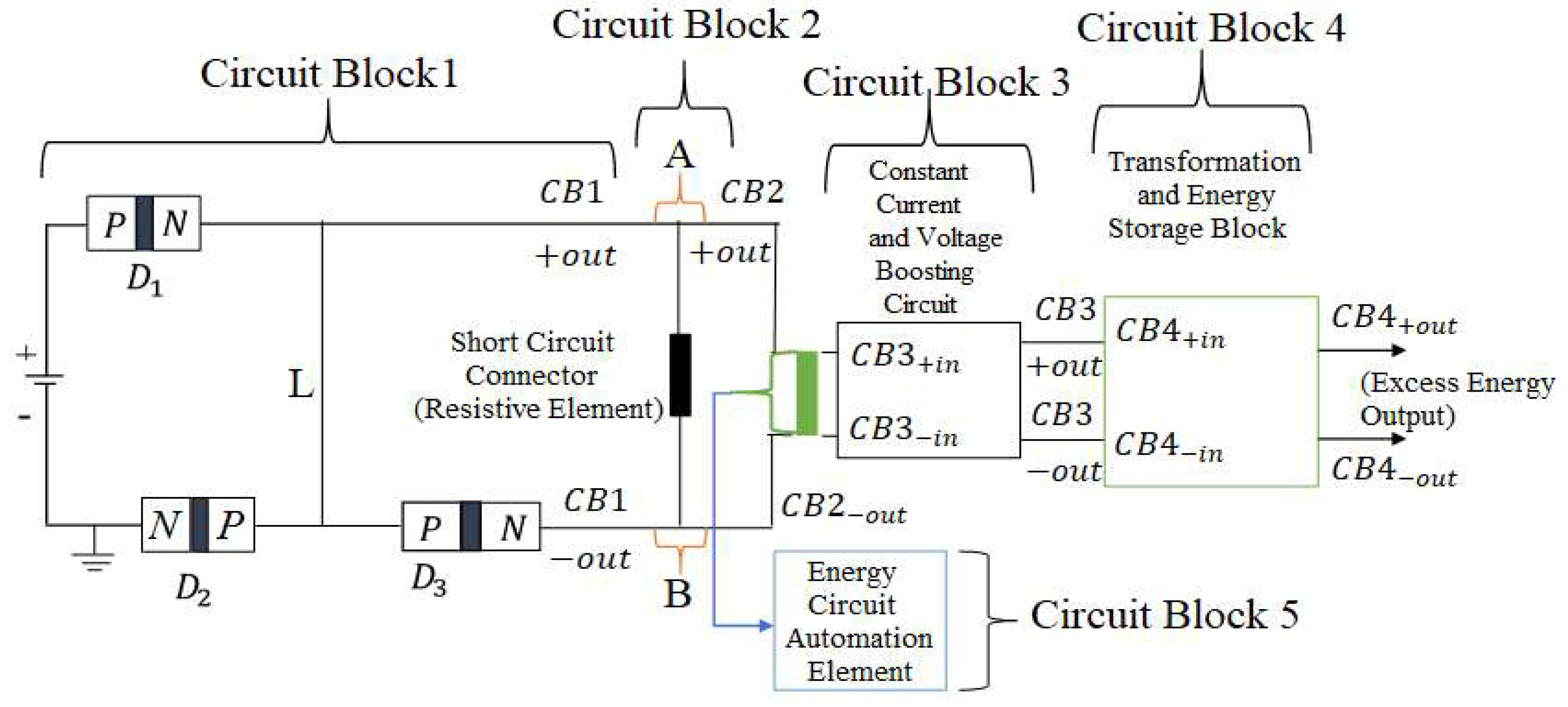

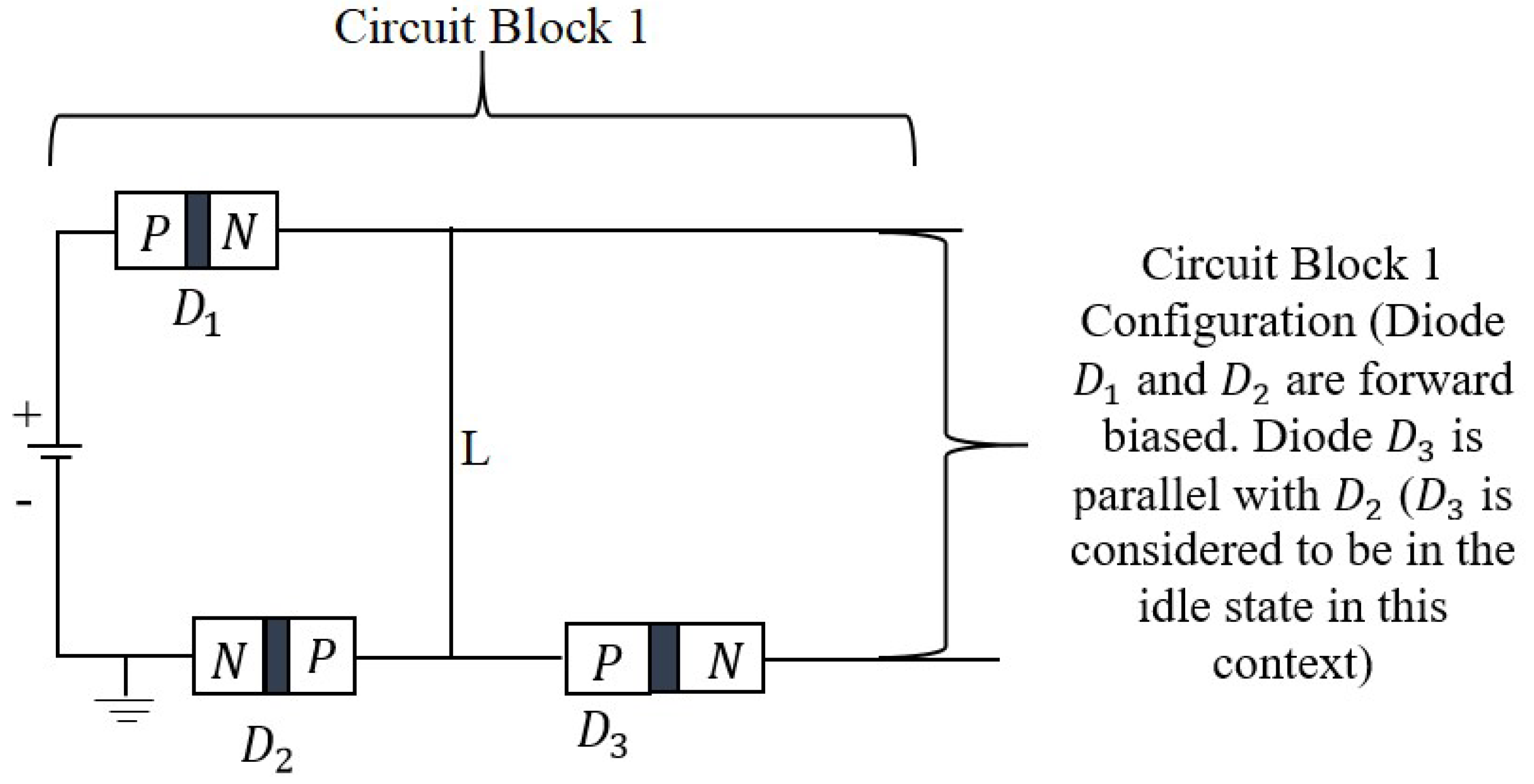

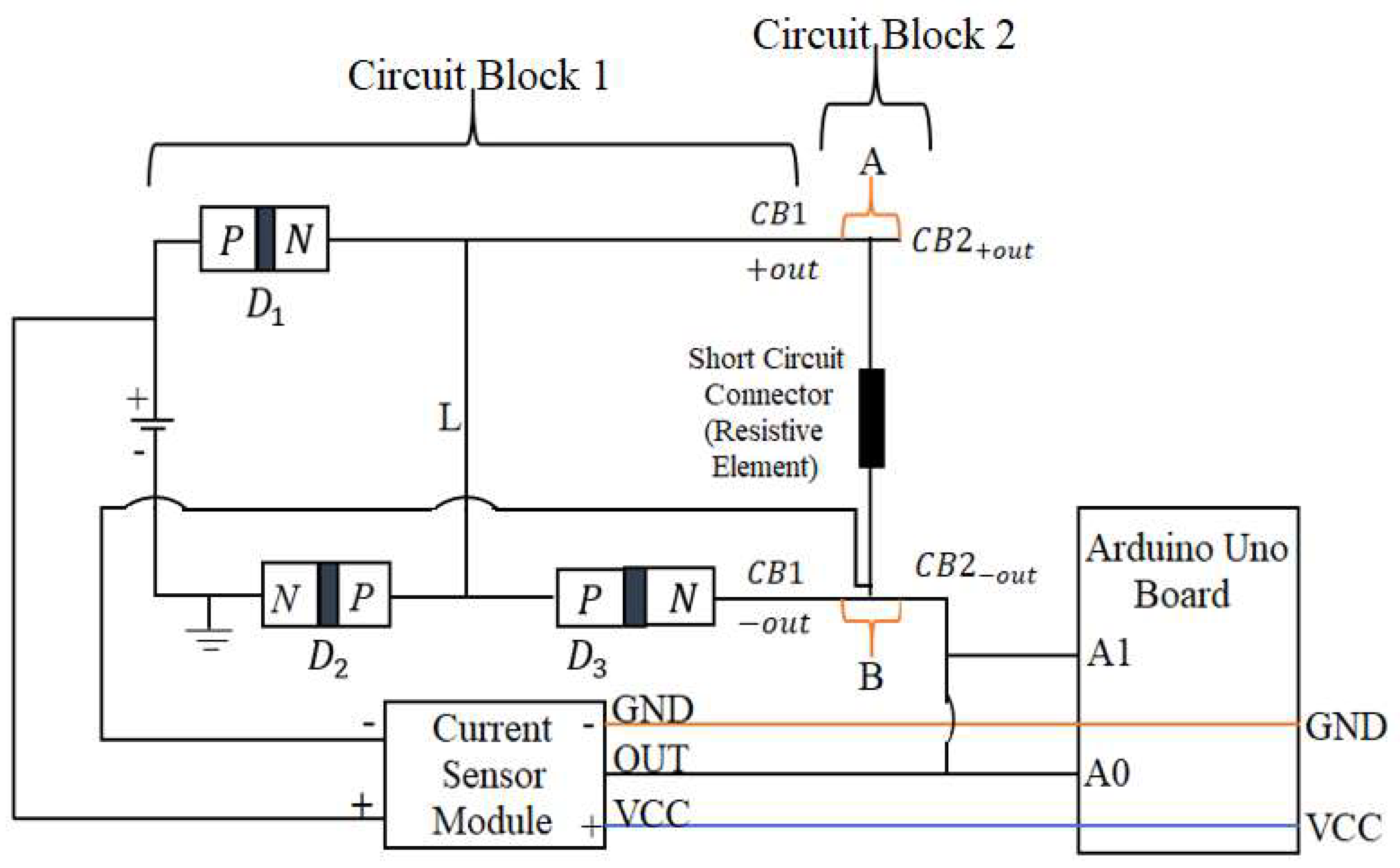

2.1.2“. Circuit Block 1” (Initial Exploration of Ohm’s Law)

This initial section of the energy-circuit diverges from the traditional demonstration of Ohm’s Law

, which is typically characterized by a linear relationship between voltage, current, and resistance in conventional electrical circuits. In “Circuit Block 1” the focus shifts to exploring an innovative configuration involving three identical diodes: Diode 1 (

), Diode 2 (

), and Diode 3 (

), as illustrated in

Figure 3. In this uncommon parallel circuit configuration, the positive terminal of the power supply (

) is connected to the anode of

. The cathode of

branches into two paths, one leading to the anode of

and the other to the anode of

. The cathode of

is connected to the negative terminal of the power source through a ground node, while the cathode of

is connected to the input of the next circuit block. Although

and

share a common anode (from

), they are not in a conventional parallel configuration, as their cathodes are connected to different nodes. Throughout the subsequent sections of the paper, this new circuit configuration will be named as the “

short-parallel connection”. This “

short-parallel connection” creates distinct operational behavior:

, connected to the negative terminal of the power supply (

), provides a forward-biased connection loop that completes part of “Circuit Block 1” through the ground, while

continues the energy-circuit to the next sections, introducing the parallelism aspect. The primary role of

and

is to prevent unwanted current backflow, especially when

is subjected to an electrical short circuit (Definition 1). This configuration effectively mitigates undesired feedback, a common issue in standard circuits during short circuits. To understand the behavior of “Circuit Block 1”, this section establishes the operational framework using the diode equation, (Equation 1) as applied in [

40,

41]. This equation describes the current-voltage (I-V) relationship for a diode, essentially establishing how current flow through the diode changes with applied voltage.

In which;

is the diode current,

is the reverse saturation current,

is the voltage across the diode,

is the ideality factor (typically around

for ideal diodes) and

is the thermal voltage, approximately

at room temperature. For the simulated experiments, this paper will use

for the voltage across

,

for the voltage across

and

for the voltage across

. The supply voltage will be denoted by

and the forward voltage drop for

as

. These notations leads to computing the voltages in “Circuit Block 1” as;

for the forward voltage drop of the diode

. Since

is connected to ground at the cathode, the voltage across

, denoted

, is the same as the voltage at the cathode of

:

. The voltage across

, denoted

, will be similar to

since they share the same anode:

. Again, for the described circuit configuration, the total current output from “Circuit Block 1” to the next Circuit Block (denoted as

) is the sum of the currents through

and

because both currents contribute to the input of the next circuit. The current through

, denoted

, is given by the diode equation:

. The current through

, denoted

, is similarly given by:

. Lastly, the current through

, denoted

, follows the same form:

. Therefore, for two diodes (

and

as depicted in

Figure 3 we have;

and

implying:

Substituting Equation 1 (the diode equation) in Equation 2 for the “

short-parallel connection” diodes configuration;

Combining the like terms in Equation 3 and factoring out

we get;

Equation 4 represents the total current flowing through the diodes in the uncommon “

short-parallel connection” circuit configuration, (“Circuit Block 1”). Further, the total voltage fed into the next Circuit Block from both

and

(denoted as

) can be approximated according to Equation 5:

As depicted in

Figure 3, the diodes

,

, and

are configured in unique “

short-parallel connection” designed to prevent undesired backflow of short circuit current from “Circuit Block 2”, when the energy-circuit is implemented. When a short circuit occurs, the excess current attempts to flow in reverse, causing all diodes to transition into a reverse-biased mode. In this mode, the depletion region within each diode widens, increasing resistance and effectively acting as a barrier to reverse current flow. In this circuit configuration,

plays a crucial role in ensuring that the connection (L) from

to the junction between

and

does not provide a path for the excess short circuit current to flow back to the negative terminal of the power supply. During a short circuit,

’s connection to a more negative terminal of the power supply prevents any reverse current from returning to the power source, thereby safeguarding the circuit. Therefore, as the short circuit affects the circuit,

,

, and

all become reverse-biased.

’s reverse bias prevents current from flowing back into the positive terminal, while

and

, despite sharing a common anode, act as barriers at their respective nodes-

to the negative of the power source and

facilitating the excess short circuit current to the next circuit block-effectively preventing any unwanted current backflow and maintaining circuit stability.

Figure 3 illustrates this “

short-parallel connection” circuit configuration model, where the coordinated action of all three diodes is meant to ensure a robust protection against short circuit conditions, as demonstrated in

Table 1 and Figure 5.

Definition 1 (Model of Diode Idle State or Inactive Mode). In the context of “Circuit Block 1” (

Figure 3), a diode’s idle state occurs when it is reverse-biased but not actively conducting. In this mode, the diode behaves as a passive element, essentially a closed switch, until a load is applied. Diode

in

Figure 3 demonstrates this idle state. During a short circuit, the diodes effectively function as a barrier with infinite resistance, preventing reverse current flow

In practice, utilizing Equation 4 requires specific parameters for each diode in the energy-circuit, including forward voltage configurations ( and ), ideality factor (), and reverse saturation current (). Considering the foundational principles for “Circuit Block 1”, does not contribute to the forward voltage of the next block circuit. Therefore, the subsequent analysis will be based on the forward voltages and , over the expression: . This observation preserves conformity with theoretical foundations, reserving as “Circuit Block 1” protection component during the electrical short circuit. Therefore, within this context, “Circuit Block 1” plays a critical role. It employs these diodes to prevent current from flowing back to the power source, safeguarding the integrity of subsequent stages. In contrast, “Circuit Block 2” introduces a controlled electrical short circuit, a design that anomalously results to an excess current. If this short circuit current were allowed to return to the power source, it could cause damage to the energy-circuit. The overall effectiveness of “Circuit Block 1” in preventing this backflow relies heavily on the initial power supplied by the types of diodes applied in the circuit. Consequently, the specific one-directional current components chosen for “Circuit Block 1” can vary based on the specific application’s power demands. Further, the components including; typically the diodes, are not characteristically fixed but can be tailored to the unique characteristics of each application, enhancing the overall versatility of the energy-circuit.

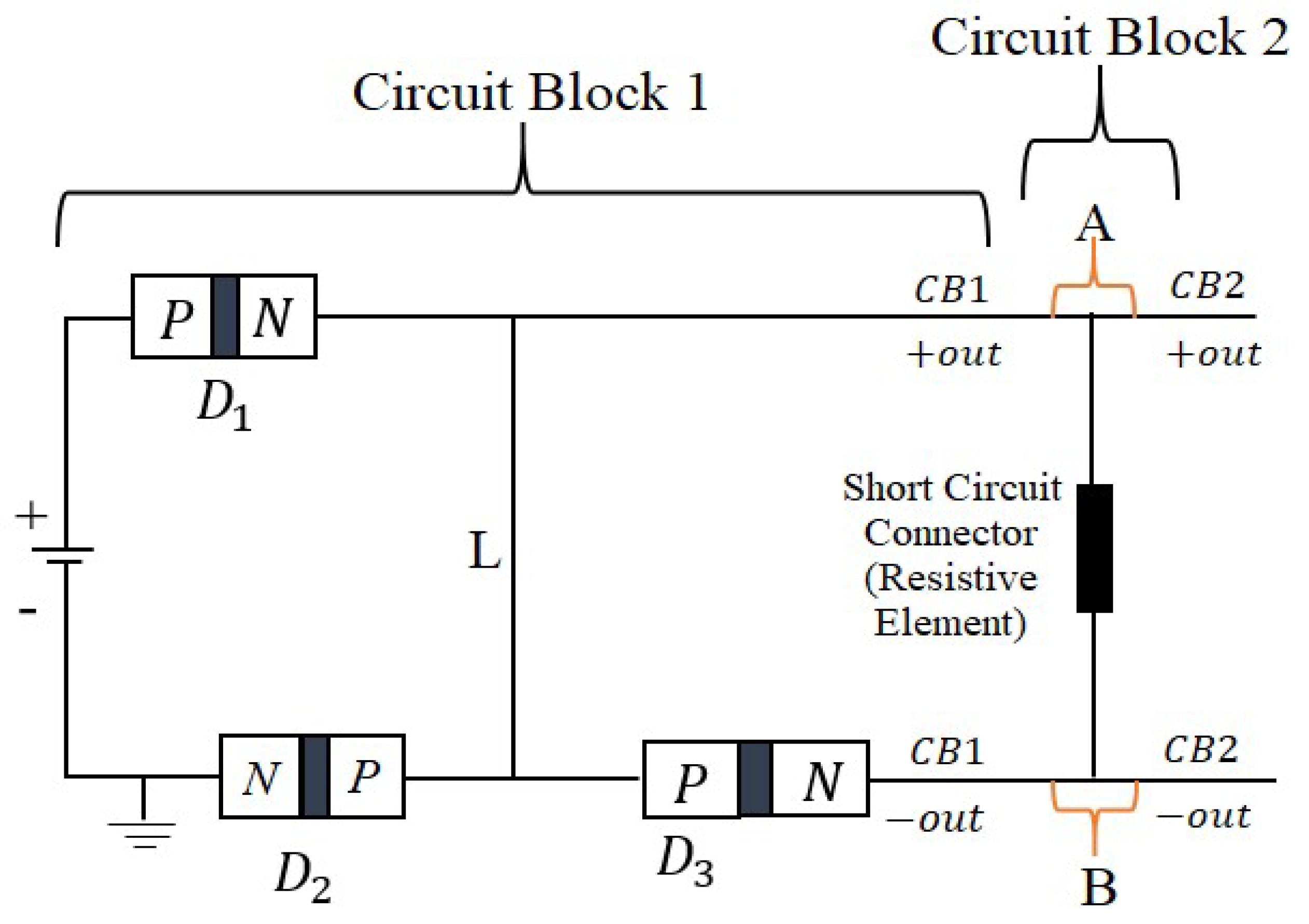

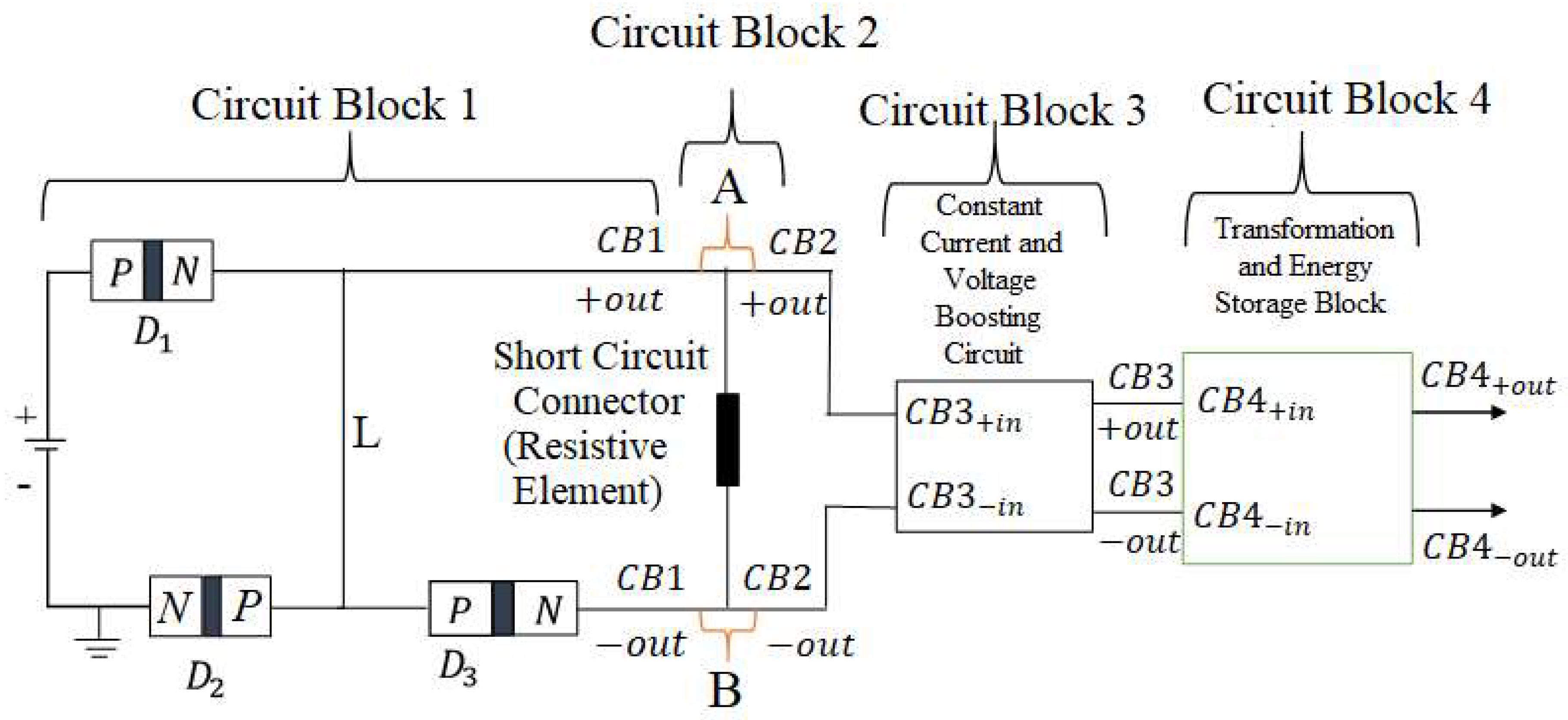

2.3.4. Short Circuit (“Circuit Block 2”)-Experiment Design

Three distinct experimental configurations were employed: a short circuit control experiment, an induced short circuit experiment (replicating natural electrical short circuits), and a simulated short circuit experiment. All experiments utilized a standardized apparatus consisting of a

DC power supply, an ACS712T 20A current sensor module, three

1N5408 power diodes, and an Arduino Uno, carefully selected for safety and simplicity. Notably, for the control and the induced short circuit experiments, the power supply selection was informed by a simulation approach based on a Modified Ohm’s Law equation [

19].

The Modified Ohm’s Law. The Modified Ohm’s Law, as presented in [

19], provides a more accurate model for predicting and quantifying short circuit currents and voltages in both ideal and experimental conditions, particularly for low-resistance applications. This model proved invaluable in determining the appropriate initial power supply input for various diode types during the experiments. The short circuit current, denoted as (

), was initially simulated and calculated using the Modified Ohm’s Law current formula (Equation 6). Unlike the Standard Ohm’s Law, which would be inaccurate for the low-resistance conditions of a short circuit, the Modified Ohm’s Law is specifically designed to handle nonlinear circuit behavior. Equation 6 served as a crucial tool and experimental resource for accurately predicting the electrical short circuit current and circuit materials requirements within our energy-circuit.

Where:

, is current scaling factor.

is the reference resistance.

is the source or supply voltage.

is the change in resistance from its reference value .

In this context,

, where the standard circuit resistance (

) is considered to be a function of the parameter (

) as established by [

19]. Theoretically, using Equations 5 and 6, the power input to “Circuit Block 2” can be calculated using Equation 7.

As previously noted, one of the primary objectives of “Circuit Block 2” is to generate excessive short circuit current and efficiently direct this high current to the subsequent stages of the energy-circuit. The short circuit connector (the resistive element shown in

Figure 4), often termed the resistive element, plays a pivotal role in achieving this goal. It not only establishes the short circuit in tandem with “Circuit Block 1” but also contributes in ensuring that the high short circuit current flows forward in the energy-circuit without causing damage. In the essence, this resistive element becomes the first path of low resistance after the electrical short circuit, preventing the excess current from finding its way back. Therefore, the consideration “

resistive element” is a practical signature to ensure that in an experiment, this conductor is relatively within the same resistance to other conductors (connection codes) in the circuit. The circuits dual role is crucial, as the resistor, in collaboration with “Circuit Block 1”, prevents undesired backflow, while its high resistance directs the abundant short circuit current toward the next stages. To validate the operation of “Circuit Block 2” in this paper, the resistive element will be assumed to have the same resistance as the other connecting cables used in the described experiment. Importantly, “Circuit Block 1” current and voltage outputs transition to become the inputs for “Circuit Block 2”, maintaining the uninterrupted flow of power and energy throughout the energy-circuit’s progression. Further, we take into account the effective resistance in the “Circuit Block 2”. This resistance will include the overall resistance in “Circuit Block 1”, and it can be computed following Equation 8.

It will then be considered that the combined resistance (named subsequently as

) between

and the resistance of the high resistive component facilitating the short circuit also contributes to ensuring the forward flow of current, from “Circuit Block 2”. For practical purposes, this resistance can be expressed following Equation 9.

The focus then shifts to understanding the practical significance of the resistance (). Through the experiment, the physical significance of the quantity will be understood based on the overall power output from “Circuit Block 2”.

A Practical Relation between the Experiment and the Modified Ohm’s Law. Again, to verify the functionality of “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2”, the value of

, which is in a direct proportion with the

has to be determined either based on experiment materials or through simulated experiments. As provided by [

19], several factors including: material properties and experimental conditions affect the choice for the parameters

and

. This section will consider only the experimental conditions (temperature and low resistance circuit type). The verification experiment was conducted within room temperature at

, using 1N5408

type power diodes. For an ideal circuit, Equation 6 demonstrates that the magnitude of the short-circuit current depends on the initial power supply voltage. For example, with a simulated supply voltage of

and a reference resistance of

the output short-circuit current will be;

. This calculated current must not exceed the minimum current rating of the diode. The chosen 1N5408 power diode has a current range of

. For simplicity, we will operate at the minimum current of

. The power supply selection followed the criterion established in case 1.

Case 1 (Determining Minimum Supply Voltage). To determine the minimum experimental supply voltage, we set the diode’s minimum operating current to approximately using Equation 6.

Where:

.

, is current scaling factor.

.

is the change in resistance from its reference value .

Since , we can substitute this into the equation: .

We then proceed in an assumption that does not distort the genetic design of Equation 6, by considering the case of a pure electrical short circuit hence the , and the exponential term becomes , so the equation simplifies to: . Therefore, . Substitute known values; . Simulated analysis of this power output results is provided in the supplementary materials.

This calculation justifies the experimental framework depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 4 shows the “Circuit Block 2” configuration, which was automated based on the circuit design in Figure 7.

Investigation 1. Automated measurement of the short circuit current. The energy-circuit verification experiment involved connecting a

DC power supply to a circuit containing three power diodes (1N5408) and an ACS712T

range current sensor module, all integrated with an Arduino Uno. The goal was to observe the behavior of the proposed energy-circuit under different short circuit conditions. To verify the creation of excess power, the experiment involved analyzing the response of the diodes during a short circuit introduced between two specific nodes (

and

) in the circuit. The excess generated current from the short circuit configuration was used to assess whether excess power was being created. The setup started with the positive

terminal of the power supply connected to the positive pin of the current sensor, while the negative of the power supply was connected to the negative pin of the sensor. Diode

was connected from the positive supply to its anode, and its cathode branched out into two paths: one leading to the positive terminal of the next circuit, and the second path running through the anode of diode

. The cathode of

was connected to ground, completing the path to the negative terminal of the power supply. Diode

was also introduced, with its anode connecting to the same point as

’s anode. However, its cathode was routed to the negative terminal of another circuit. To measure the current and voltage during the short circuit event, a connection was made between

and

(nodes

and

) using a short circuit connector, forming what was labeled as “Circuit Block 2” as depicted in

Figure 5. To measure the short circuit current, a connector was routed between the current sensor's (

) pin to pin (

) of the Arduino to measure the current, and voltage readings were taken by connecting node

to pin (

) of the Arduino via the current sensor’s (

) pin. The experiment provided an assessment of how the circuit’s ability to withstand short circuit conditions while protecting the power supply and to demonstrate the potential for excess power generation. First, current and voltage readings were recorded at

-second intervals for

seconds, both before and during the short circuit event. The experimental results are summarized in

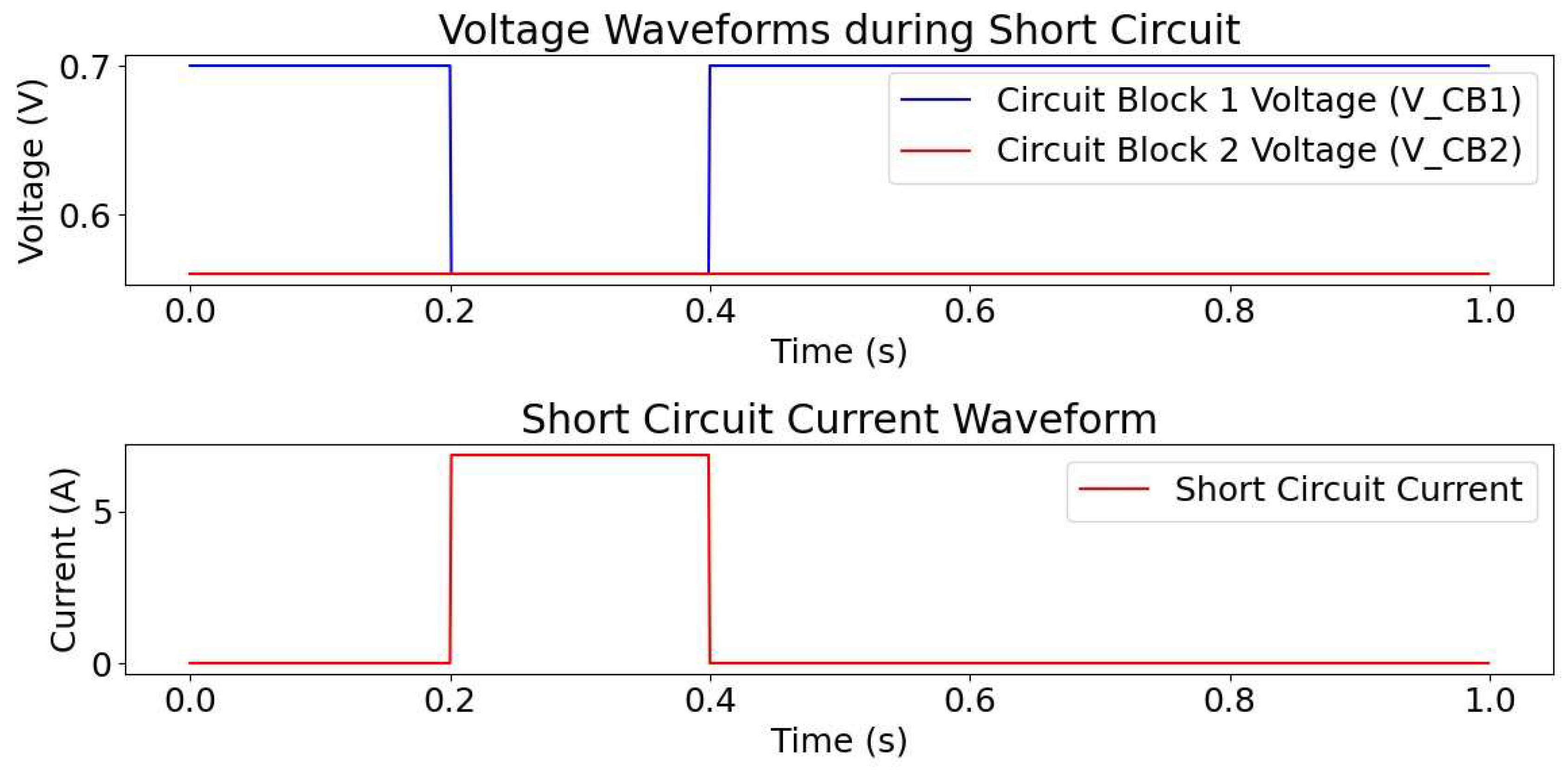

Table 1.

Figure 5 provides a block diagram of the circuit used in the experiment.

Upon creating a short circuit by connecting nodes

and

, a sudden surge of current flows through the short circuit, causing a momentary voltage drop across both diodes. This observation is consistent with recent research findings [

42]. For example, electrical short circuit currents have been experimentally determined to occur within very short time durations, typically in the range of milliseconds, with accompanying short circuit events characterized by current surges and voltage drops. During this transient phase,

, initially forward-biased, experiences a reversal of voltage polarity. When the voltage at point

falls below the cathode potential of

, the diode enters reverse bias. This causes the depletion layer to widen as electrons migrate away from the junction. Simultaneously,

also transitions to reverse bias. The voltage at node

remains higher than the anode potential of

, maintaining the widened depletion layer in

. The widened depletion layers in both diodes play a crucial role in controlling the flow of charge carriers, influencing the energy-circuit’s behavior during transient events. The operational mechanism of this diode configuration was experimentally verified, following the procedure outlined in

Figure 5. Three experiments were conducted, each yielding slightly different pre-short circuit voltage and current values due to potential sensor drifts from repeated experiments. The average pre-short circuit values were

,

, and

for voltage, and

,

, and

for current. During the short circuit event, at comparable time durations and intervals, the voltage and current values were recorded, ranging from

to

and

to

, respectively. These measurements, while influenced by sensor drifts, clearly demonstrate a significant increase in current, over

times the pre-short circuit levels. This substantial current surge is consistent with the characteristic decrease in resistance during a short circuit event. For this analysis, the lowest values of the readings before the short circuit event experiment are considered to establish a baseline. The corresponding voltage and current measurements are also considered for comparative analysis in the subsequent sections. Following this criterion, the voltage and current readings of the baseline chosen experiment before and during the electrical short circuit are provided in

Table 1, which will be referred to as the “baseline-experiment” in the subsequent analysis.

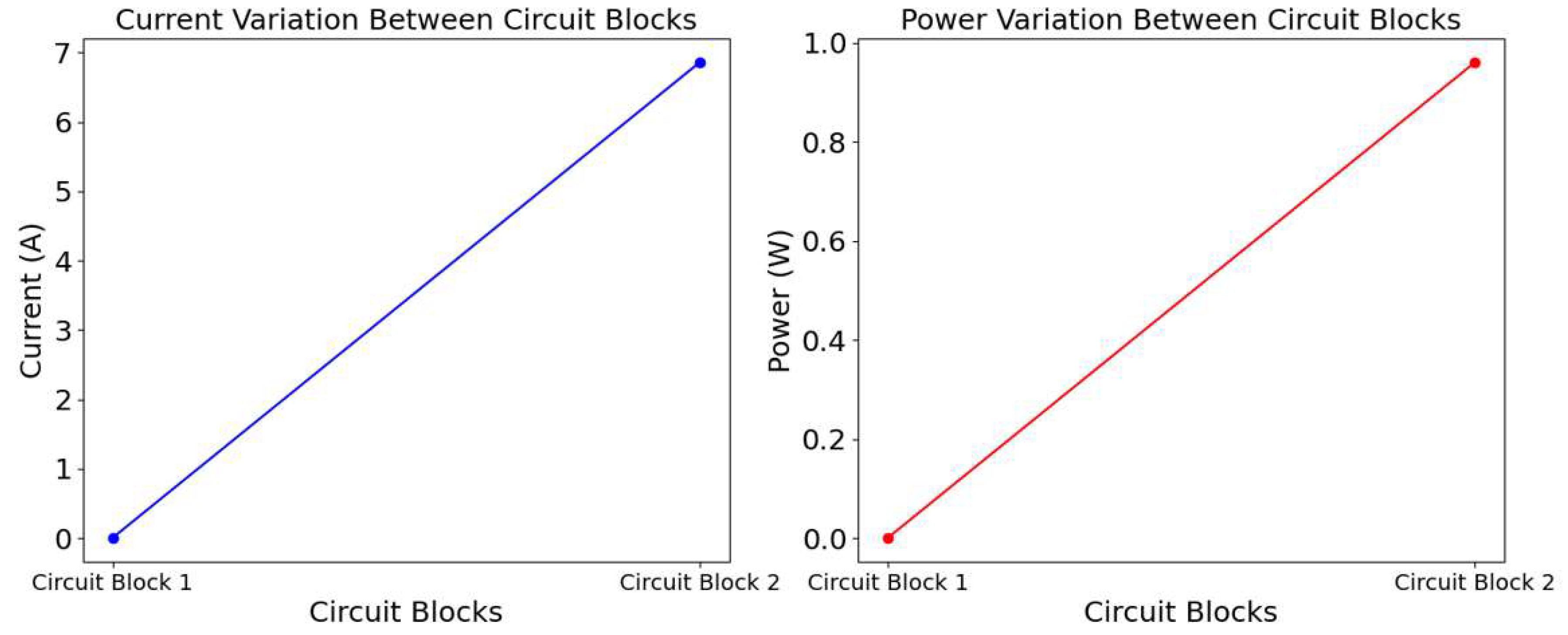

The baseline measurements in

Table 1, taken between nodes

and

of “Circuit Block 2”, demonstrate significant differences in voltage and current values before and after the short circuit event. Before the short circuit, the voltage output remained relatively stable, with minor fluctuations between

and

, while the current fluctuates slightly but remains close to

. This represents the normal operation of the circuit under low resistance conditions, where the 1N5408 power diode operates within its nominal forward voltage drop of approximately

and a forward current of around

, as specified in the diode’s datasheet. Once the short circuit is introduced, a significant change is observed. The voltage output jumps to approximately

, indicating a slight drop in the forward voltage across the diodes, which is characteristic of the diodes entering their surge current state. The current output experiences an extreme increase, consistently hovering around

after the short circuit event. This is far above the diodes' average forward current rating of

but well within their maximum non-repetitive surge current capacity of

. The dramatic rise in current after the short circuit is attributed to the low resistance path created by the short circuit, which significantly reduces the overall resistance in the circuit and allows a higher flow of current. The Modified Ohm’s Law, as employed in this experiment, effectively predicted this behavior. The exponential nature of the short circuit current, derived from Equation 6, becomes evident, with the current escalating as the resistance approaches near-zero values. The 1N5408 power diodes, with their ability to handle up to

of non-repetitive forward current, play a crucial role in safely managing this sudden surge. These results highlight the robustness of the circuit design and the reliability of the 1N5408 power diodes in handling short circuit conditions without damage. The 1N5408 power diode’s exceptional efficiency in maintaining current flow under extreme conditions is further evidenced by its low forward voltage drop of approximately

, observed post-short circuit. During short circuit events, the power output would have surged dramatically. In this experiment, the Standard Ohm’s Law (

) was employed to approximate this power, given the significant short circuit output voltage. The computed average power output during the short circuit was approximately

. While the Standard Ohm's Law may not be strictly applicable to non-ohmic scenarios, it provides a reasonable estimate in this context. However, simulated results (provided in the supplementary materials) indicate that the short circuit output current is influenced by the input voltage. As the input voltage increases, the short circuit voltage and resistance significantly decrease, converging towards non-zero but distinct values. A more sophisticated model is necessary to accurately compute power in such scenarios. To adapt the power output from “Circuit Block 2” for conventional ohmic systems, an additional circuit will be implemented and simulated to develop an ideal model operating under lower voltages, such as the approximate

short circuit output voltage. The Modified Ohm's Law (Equation 6) and its associated power model (Equation 7) are well-suited for theoretical predictions in this low-resistance regime, providing valuable insights into expected practical outcomes. This experiment demonstrates the potential for energy creation and generation in near-zero resistance scenarios. The robustness of the circuit design and the efficiency of the 1N5408 power diodes highlight the feasibility of such applications.

Remark 2 (Power Supply Considerations). The decision to utilize a external power supply was informed by several factors, including the voltage drop across diodes and . This voltage drop, calculated according to Equation 5 as , significantly influences the circuit's overall performance. Additionally, a power supply provides a suitable output voltage for approximate analysis using the Standard Ohm's Law, as demonstrated in the previous power calculations. Given that the energy-circuit’s output voltage from “Circuit Block 2” is limited to , even with an external power input of , the circuit is expected to operate as intended. This theoretical expectation is further explored in a separate paper, while the current paper maintains its focus on the power source application.

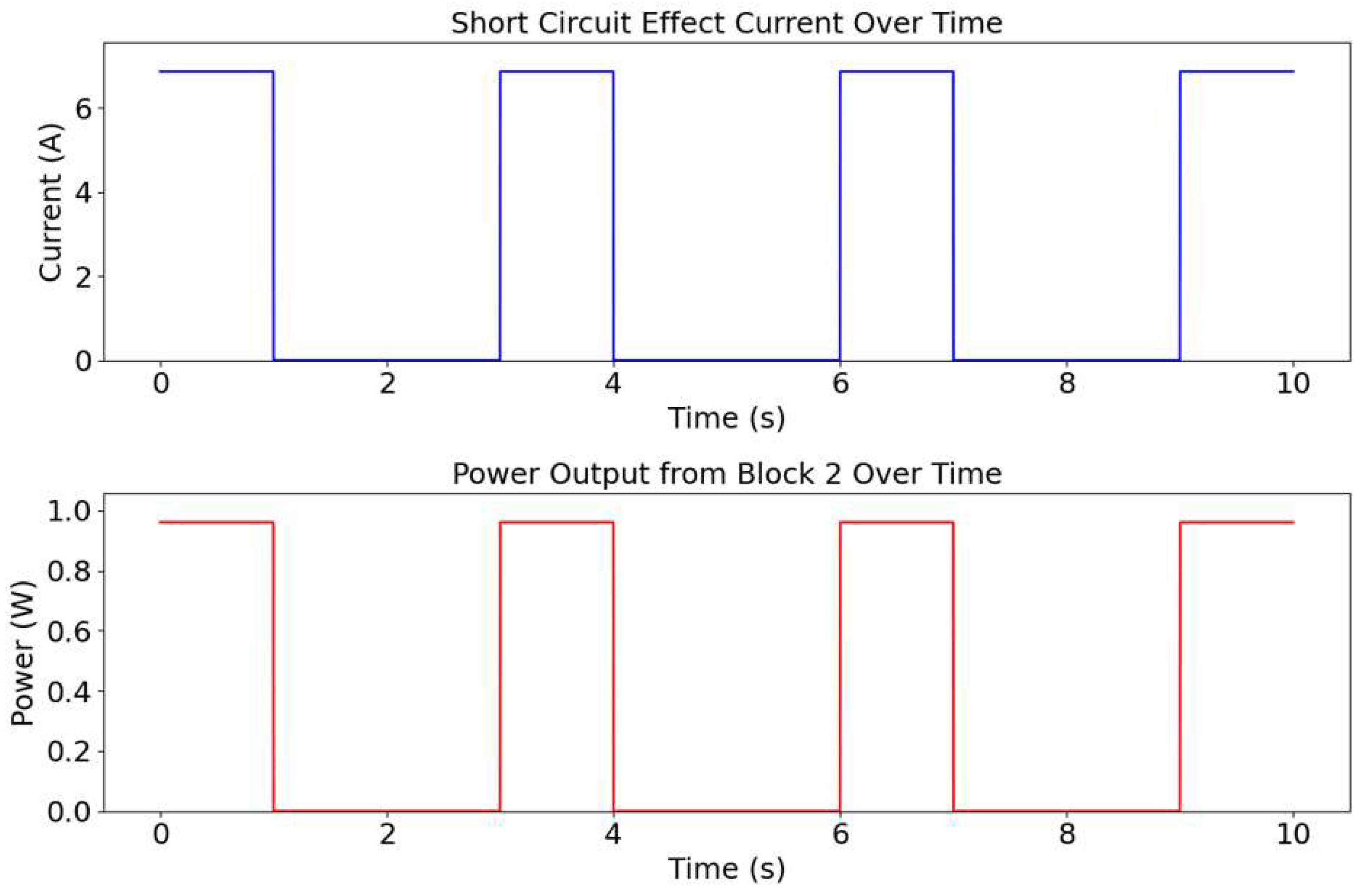

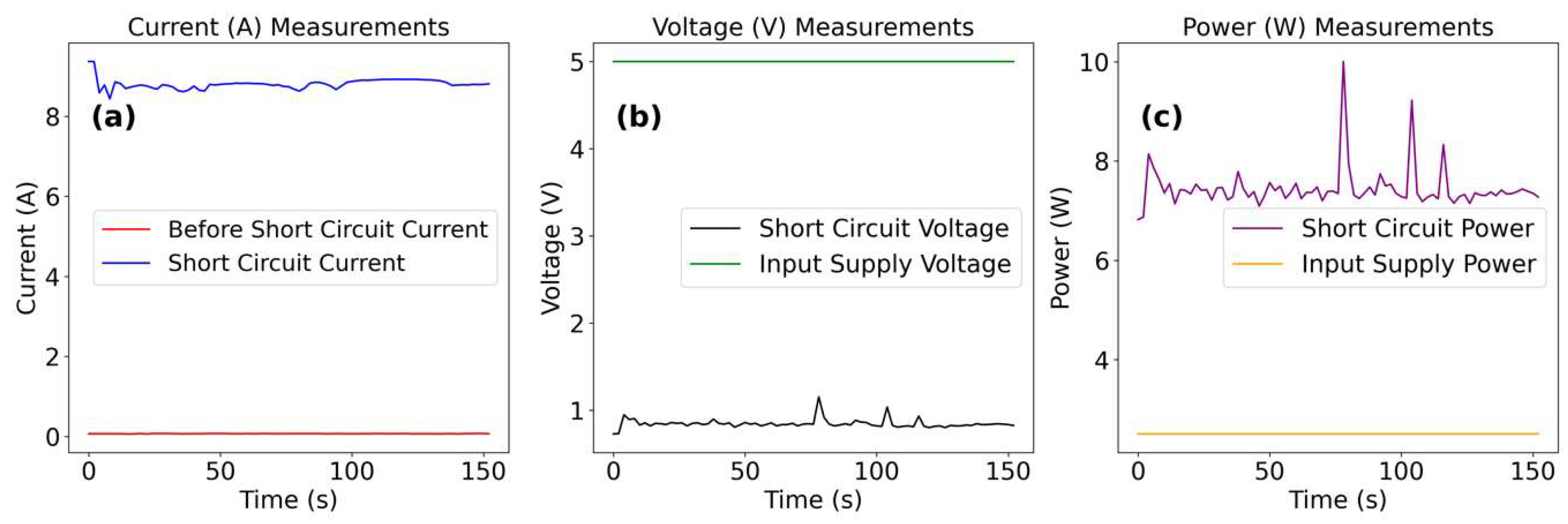

Investigation 2. Investigation of Voltage, Current, and Power Fluctuations in Circuit Block 2 Under Short Circuit Conditions. The short circuit current measurement experiment was repeated to investigate the electrical characteristics of “Circuit Block 2”, particularly the behavior of the diode connection under short circuit conditions. Over a three-minute period, measurements were taken every two seconds to observe fluctuations in voltage, current, and power outputs before and during the short circuit event. Three diodes (

,

, and

) were connected in an uncommon parallel configuration to assess their collective performance. Key metrics recorded included voltage drops to approximately

, current surges relatively exceeding

, and power outputs fluctuating between

and

. As shown in

Figure 6, the results indicate that the circuit was not only capable of enduring a sustained short circuit but also generating excess power while effectively protecting the power source from damage.

Figure 6 illustrates the experimental results obtained from “Circuit Block 2” during the short circuit event. It presents the baseline and post-short-circuit experimental results at Node

, providing insight into how voltage, current, and power output transform under short circuit conditions. Prior to the short circuit, the voltage remains relatively stable, averaging around

, indicating a consistent operating state. However, once the short circuit is initiated, the voltage output drops dramatically, averaging

within a narrow range from

to

. This marked reduction in voltage is consistent with short circuit behavior, where the minimal resistance in the short circuit path leads to most of the supply voltage dissipating. Such a drop demonstrates that the circuit is designed to effectively handle high-current conditions without compromising its structural integrity or protective mechanisms, reflecting its efficiency and stability under stress. In terms of current response, the output at Node

initially averages

under standard conditions but undergoes a significant surge to an average of

following the short circuit event. This sharp increase aligns with Ohm’s Law, where a reduction in resistance enables substantially higher current flow. The current remains elevated, ranging between

and

, indicating the circuit’s capability to manage extreme current inflows during a short circuit without displaying erratic behavior or fluctuations. This consistency is crucial for maintaining operational safety, ensuring the power source remains functional without overheating or risking immediate circuit failure, even under extreme conditions. The power output, approximated using the Standard Ohm’s Law as the product of post-short-circuit voltage and current, averages

, representing a notable increase compared to baseline conditions. This elevated power level reflects the transient dynamics between voltage and current, which interact to sustain the high power output. Importantly, the power remains steady, without significant dips, showing that the circuit channels the increased current into useful power output rather than succumbing to energy waste or performance degradation during high-stress events. This efficient conversion and sustained power level demonstrate the circuit’s innovative design, as it effectively manages a potentially destructive short circuit scenario by stabilizing power flow and mitigating risks to the power source. Overall, the ability to sustain elevated current and power output under short circuit conditions underscores the circuit’s advanced design and its capacity to leverage short circuits constructively, maintaining reliable performance across variable conditions.

Implications of the Proposed Energy-Circuit Design. The proposed energy-circuit experimental research has significant implications. The circuit design presented between “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2” is the first known experiment to demonstrate how electrical short circuit current can be measured over an extended period within a classical framework. Traditionally, short circuits are considered destructive and often lead to immediate system failure or activation of protection mechanisms [

35,

36]. However, this experiment not only sustains short circuit conditions for a prolonged duration but also enables accurate measurement and analysis of the current flow without destabilizing the power source. This achievement opens up new possibilities for studying high-current, low-voltage phenomena and designing circuits that can withstand extreme electrical conditions. Another significant implication is the violation of the classical law of energy conservation observed in this experiment. The proposed circuit successfully generated excess energy under short circuit conditions, challenging the foundational principle that all power input into an electrical circuit must be consumed or dissipated [

43,

44]. By leveraging an unconventional non-ohmic circuit design, the experiment demonstrated that the circuit could generate power levels far exceeding the input, refuting the notion that electrical systems inherently lose energy during operation. This breakthrough suggests that the energy produced can be harnessed and transformed into a more conventional ohmic output, making it compatible with current electronic and electrical designs. The ability to create excess energy in this way introduces new potential applications in energy systems, where efficiency and power generation are paramount. The higher power output observed during the experiment directly contradicts the traditional view in electric circuit theory that all input power is inevitably consumed or dissipated within the circuit [

45]. Instead, the results suggest that the proposed energy-circuit design can manage and exploit short circuit conditions to generate power that exceeds the input. This has profound implications for the development of energy-efficient circuits that not only protect the power source but also capitalize on what would otherwise be considered destructive electrical events. Lastly, the experimental results highlight the critical role of the combined resistance, as expressed in Equation 9, in contributing to ensuring the forward flow of current. The overall resistance in Equation 9 has also not impeded the circuit from generating excess power output, further refuting the notion of power losses within any circuit aimed at breaking the law of energy conservation. The practical significance of this resistance lies in its contribution to the overall power performance, underscoring the importance of precise resistance management in designing circuits capable of excess energy generation. This advancement demonstrates how innovative circuitry, like the one presented between “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2”, can redefine the understanding of energy conservation and power generation in electrical engineering.

Remark 3 (Circuit Protection Mechanism-Power Source). The protective function of “Circuit Block 1” is primarily due to both diodes, and , becoming reverse-biased following a short circuit. This reverse biasing prevents current from flowing in the opposite direction, effectively shielding the power source from potential damage. The depletion layers in and act as barriers, inhibiting the movement of charge carriers and isolating the energy-circuit from any harmful effects induced by the short circuit. This protective mechanism was verified through experimentation with the energy circuit's behavior when “Circuit Block 2” was introduced. Initial results, using a 1N5408 power diode with a input, demonstrated a nearly drop in , the voltage output from “Circuit Block 2”. This significant voltage drop not only confirmed the protective capability of “Circuit Block 1” but also highlighted its effectiveness in managing and analyzing an electrical short circuit.

Remark 4. The proposed energy-circuit configuration (

Figure 4) although uncommon, while innovative in its application of diode characteristics to create a protective mechanism during short circuits, aligns seamlessly with established principles of semiconductor physics and diode behavior [

40,

41]. It adheres to the well-established properties of diodes in forward and reverse bias states, demonstrating a clear understanding of their depletion layer dynamics and the consequent influence on current flow.

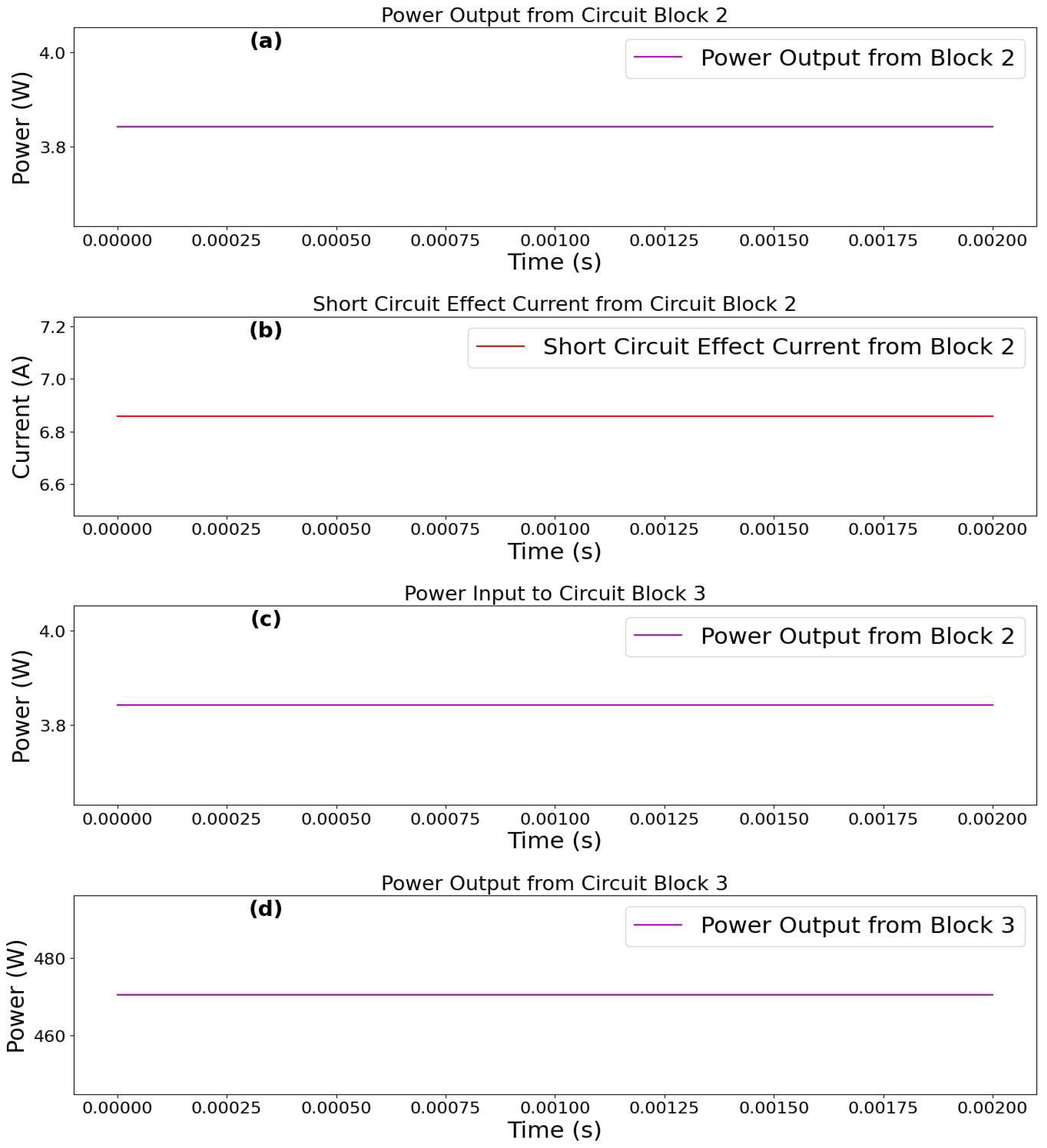

2.3.5. Adapting the Energy-Circuit Experimental Results for Ohmic Simulation

The experimental results from the energy-circuit framework, as illustrated in

Figure 5, indicate that significant excess energy was produced compared to the initial energy input. However, these results are incompatible with conventional electronics and engineering circuits that operate at higher voltages than the circuit’s operating currents. The non-ohmic nature of the energy-circuit’s components is the root cause of this discrepancy. To align the generated power with current power systems, the non-ohmic sections must be transformed to produce an ohmic output. The power output from “Circuit Block 2” can be harnessed and converted to an ohmic form while maintaining a relatively constant current. This approach allows for achieving higher power levels through voltage boosting, which is necessary due to the considerable voltage drop during the short circuit. It is also crucial to monitor the power trends between the intended loads and the energy-circuit power generation system developed in

Figure 4. Depending on the power source, some systems may not require prolonged short circuit durations. Therefore, an automated circuit is recommended to control the on-off durations during power creation events (“Circuit Block 5”). In previous experiments, an Arduino-based sensor system was integrated into the energy-circuit to measure the output current. A similar sensing system can be repurposed here to perform the time management task and facilitate seamless power generation. To complete these operations and considering the lower output voltages from “Circuit Block 2”, this section and the subsequent analysis will employ a simulated ideal system based on the Modified Ohm’s Law. Experimental variables will be carefully chosen to mimic real-world scenarios similar to the previously conducted experiments. For instance, consider that after the short circuit happens (this event should be time depended as described in “Circuit Block 5”) the input voltage into “Circuit Block 2” is expected to drop suddenly (as earlier established), to some value by some factor (let this factor be named

and for computational and simulation purposes here, it is set to a lower value;

). The

means that the voltage drop after the short circuit is

of the initial input voltage before the short circuit. So now applying the Standard Ohms Law (

) in this scenario, the voltage across “Circuit Block 2” (referred as

) can be computed as”

. This voltage can be compared with the simulated voltage derived as follows, following the baseline-experiment results in

Table 1.

Voltage Simulation Algorithm. As observed in

Table 1 (baseline experiment results), this simulation algorithm models a scenario where an external small voltage variable DC power supply initializes the voltage at “Circuit Block 1” (

) to approximately

. When the system transitions into a short circuit condition, the voltage output then drops to around

, reflecting the output from “Circuit Block 2” (

) under these circumstances. This simulation algorithm is designed to represent the observed voltage behavior, capturing the significant drop associated with short circuit events.

To establish this framework, we define two transformation variables, and , based on the observed voltage changes:

This variable represents the proportional decrease from the initial at to the short-circuit voltage output of approximately at .

Next, applying this transformation to the input voltage

, we define the function

for the output voltage at

according to Equation 10:

Equation 10 provides a straightforward computation of during simulation, directly scaling the initial input voltage by ccc to simulate the short-circuit output. Here, the algorithm begins with the external DC supply voltage, modulates it through with an output of , and applies the scaling factor to achieve the simulated output of during a short circuit. In implementing Equation 10 within simulation experiments, this approach effectively captures the drastic voltage reduction in response to a short circuit, offering a model that aligns with observed experimental data.

Equation 10 is then applied to compute during the simulation experiemnts.

To this far, we have all the necessary requirements for working out the power output form “Circuit Block 2”. Consider Equation 11.

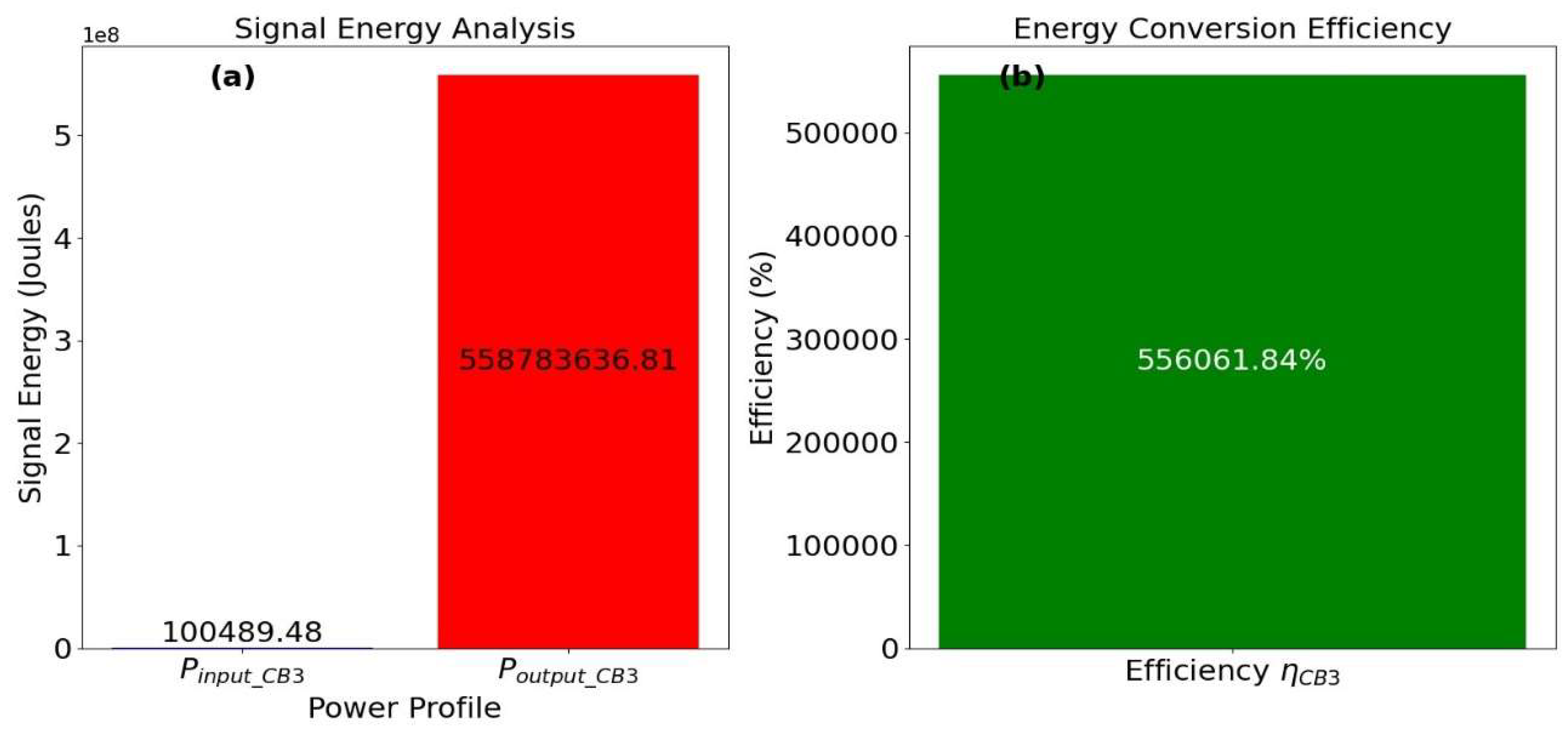

Equation 11 provides a model for computing the simulated power input to “Circuit Block 3”, which is discussed in the next section.

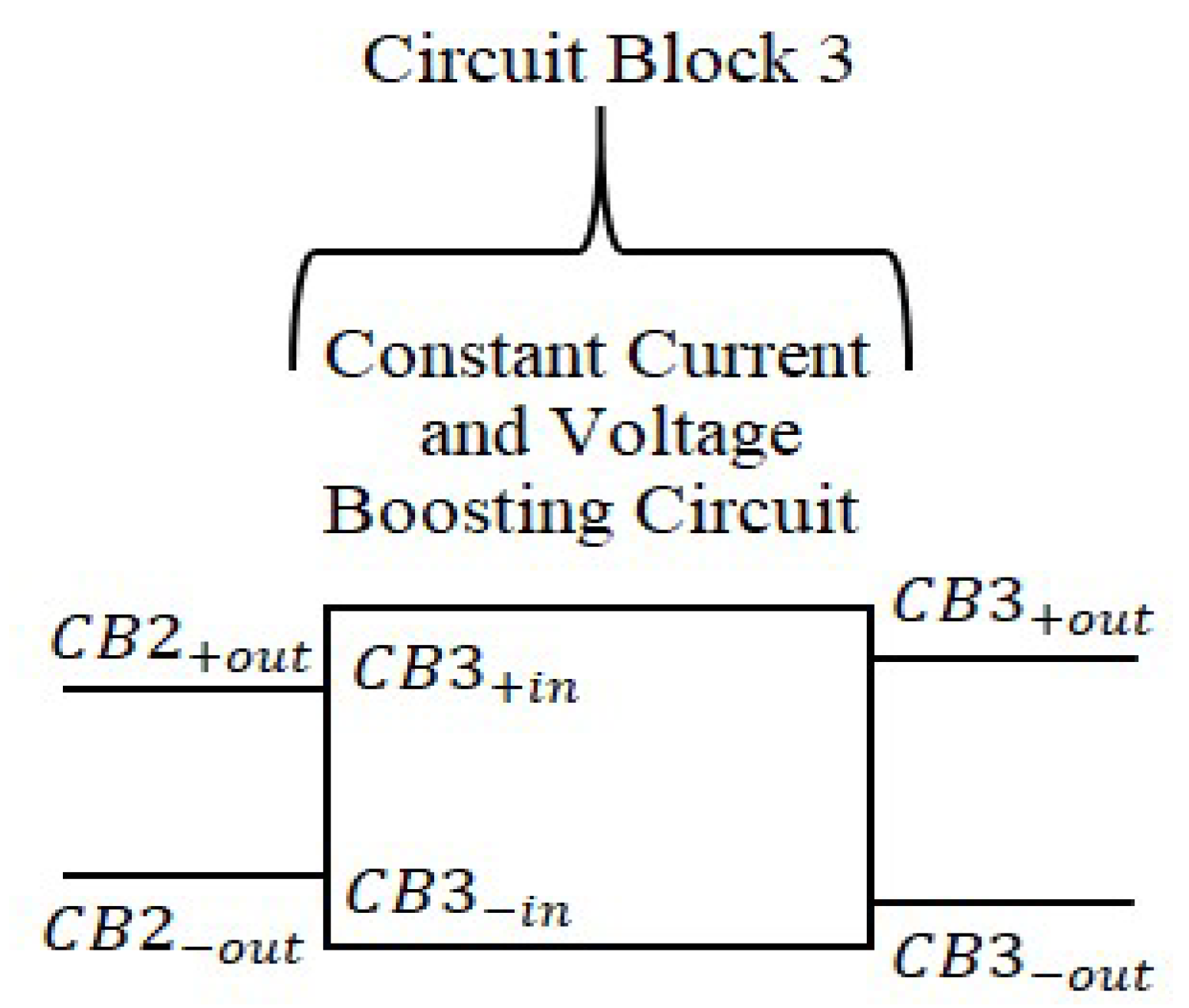

2.3.6. Circuit Block 3 (Advancing Energy Transformation)

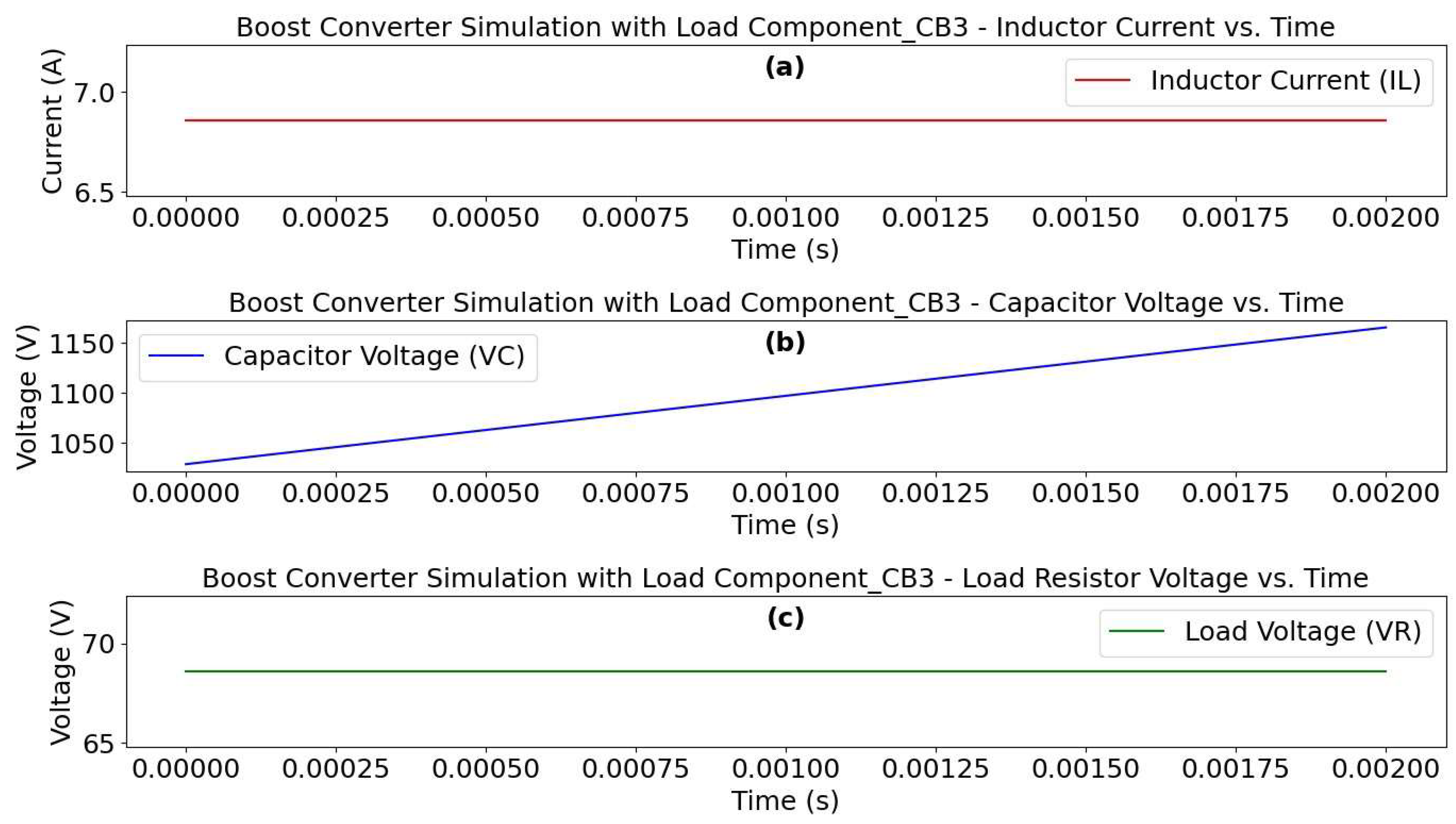

This section introduces “Circuit Block 3”, a crucial component designed to transform the non-ohmic output from “Circuit Block 2” into an ohmic format suitable for standard circuit applications. Building upon the energy transformation process, “Circuit Block 3” introduces the “load component_CB3”, also known as a constant current boost converter. Unlike “Circuit Block 1” and “Circuit Block 2”, which operate in a non-ohmic state, “Circuit Block 3” aims for an ohmic state while maintaining a high and consistent current. To achieve this transition, “Circuit Block 3” leverages the existing resistance from “Circuit Block 1”, denoted as (Equation 8), rather than introducing additional resistive elements (a simplification for simulation purposes). This effective resistance is then incorporated into the analysis of energy conservation to investigate the energy-circuit’s behavior. Within “Circuit Block 3”, the “load component_CB3” plays a key role in achieving the Ohmic state while maintaining consistent short-circuit current. Its primary function is to boost the voltage to its highest achievable level while keeping the current constant. Ideally, this component would be a boost converter circuit. This section explores a simplified design for the “load component_CB3” based on mathematical formulas describing the dynamics of the inductor current () and capacitor voltage () over time. These equations, focusing on the inductor and capacitor as the main components of “Circuit Block 3”, will later be used in simulations to analyze the component’s behavior within the energy-circuit.

The Inductor Current (). The basic formula for the voltage across an inductor is given by;

In Equation 12,

represents the voltage across the inductor,

is the inductance itself, and

signifies the rate of change of the inductor current over time. Equation 12 is a fundamental relationship used in boost converter applications, and it has been adapted for various purposes by [

46,

47]. In the boost converter circuit, during the on-time (

) of the switch, the voltage across the inductor is the difference between the input voltage (

) and the output voltage (

). This is because the inductor is effectively connected to the input during this time. Further, during the on-time (

) of the switching element, the inductor current (

) increases, and during the off-time (

), the inductor discharges through the load. In this case, we consider the scenarios; due to the on-time (

) and due to the off-time (

).

During ON time (). The voltage across the inductor (

) is equal to the difference between the input voltage (

) and the output voltage (

) according to Equation 13.

Now, relating Equation 13 to Equation 12 we obtain Equation 14, which is to be further reduced.

.

During OFF time (). The voltage across the inductor (

) is equal to the output voltage (

), a situation expressible according to Equation 15.

Applying Equation 15 to Equation 12 we obtain;

which on rearranging becomes Equation 16.

Next, we express the duty cycle (

) in terms of time. The duty cycle is defined as the ratio of the on-time (

) of the switch to the total time period (

), as expressed in Equation 17.

The total period is the sum of the ON and OFF times and can be expressible according to Equation 18.

Using Equation 17 in Equation 18 we get;

Solving for

and

we have;

Now, we can express the rate of change of inductor current

during the entire period as;

Simplifying Equation 21 further, we obtain Equation 22 as follows.

Equation 22 which is a first-order linear differential equation provides the final expression for the rate of change of inductor current with respect to during the entire switching period within the “Circuit Block 3”. If we integrate this equation over time, we can obtain the actual expression for as worked out in the subsequent section.

Remark 5 (On Energy-circuit Simulation). The on-time () event in “load component_CB3” can be related to the switching frequency () as . Substituting this into the duty cycle definition (Equation 17), we get . This duty cycle definition will later be used for simulating real-world scenarios of the proposed energy-circuit.

Solution for the Constancy of . Proceeding from Equation 22, the goal of this workflow is to find the actual expression for

, by integrate both sides of the equation with respect to time

.

Solving Equation 23 gives;

Where is the constant of integration.

Equation 24 can be rewritten to give the following relationship;

.

The integration of

with respect to time results in

, and the integration of

with respect to time results in

, and the operation can be expressed according to Equation 25.

Equation 25 further simplifies to Equation 26 as follows.

Here, is a constant of integration.

Determining the integration constant . To determine

, we need an initial condition. This can be achieved by setting

, the inductor current

is equal to the short circuit effect current (

), which is the initial condition to be used in the energy-circuit simulation.

Substituting and Equation 27 into Equation 26, we then solve for as follows;

, which reduces to Equation 28.

Now, substituting Equation 28 back into Equation 26 we obtain;

, which simplifies to:

Equation 29 provides the actual expression for the inductor current () as a function of time in the boost converter circuit for “Circuit Block 3”.

Capacitor Voltage (). To complete the mathematical representation of the capacitor voltage (

) equation, this section uses the fundamental relationship in circuit analysis, which relates the current (

), capacitance (

), and voltage (

) for a capacitor according to Equation 30.

In this case, the current

is the inductor current (

), and the voltage

is the capacitor voltage (

) [

46,

47]. Therefore, Equation 30 becomes.

Now, the next task is to solve the differential Equation 31 for , since the inductor current () is known from the boost converter equations through Equation 28.

Rearranging Equation 31 we get;

We then integrate Equation 32 with respect to time to obtain Equation 33.

Where

is the constant of integration. Substituting for

from Equation 30:

Solving Equation 34 reduces the problem to:

This equation represents the voltage across the capacitor as a function of time. The integration constant would be determined by the initial voltage condition across the capacitor, typically provided in the problem statement or the energy-circuit's initial state.

Determining the integration constant . The constant

is determined using the initial condition for the capacitor voltage, typically

. Assume at

, the capacitor voltage is known:

Substituting

into the expression for

(Equation 35) we obtain:

, which simplifies to:

Thus, the expression for the capacitor voltage becomes:

Equation 38 gives the expression for the capacitor voltage () in terms of the inductor current () and other circuit parameters constituting the “load component_CB3”. The equation suggests that the voltage across the capacitor changes over time due to the combined effects of the inductance , the difference between the input and output voltages , and a short circuit current effect . The equation is quadratic in time , indicating that the voltage may increase non-linearly over time due to the inductive effects, and also linearly due to the short circuit effect. The term involving suggests that the inductive component contributes to a parabolic increase in voltage over time, while the term involving suggests a linear contribution from the short circuit effect. The mathematical formulations through “Circuit Block 3” will be highly relied on, through simulating the provided energy-circuit.

“Load Component_CB3” Major Simulation Elements-An Overview. “Load Component_CB3” is a specialized circuit designed to efficiently convert excess energy from “Circuit Block 2” into a usable DC voltage. This voltage boost is essential for integrating the energy circuit into conventional electrical systems. The circuit's ability to handle low input voltages, as shown in

Table 1, makes it a valuable component for exploring potential applications that challenge traditional energy conservation paradigms.

Inductor (L). The inductor value (

) in the “load component CB3” significantly influences energy storage and transfer. Its selection is based on factors including desired output voltage, input voltage, duty cycle, switching frequency, and ripple current. The inductor must be capable of handling the required current and operating within the specified input voltage range. For simulation purposes, the inductor value will be fixed.

The equation considers;

is the inductor value.

is the desired output voltage.

is the input voltage.

is the duty cycle of the converter.

is the switching frequency.

is the peak-to-peak inductor ripple current.

Switching Element. In practical settings, the objective here is to choose a switching element (such as MOSFET) capable of handling the desired voltage and current while minimizing ON resistance (). The procedure involves considering the voltage rating, ensuring the switching element in this context can handle maximum current, and selecting a switching element with low ON resistance to reduce power losses.

Diode (D). In this step, a diode can be selected with a voltage rating higher than the desired output voltage. The diode is crucial for allowing current flow and maintaining the desired output voltage.

Output Capacitor (C). In designing the “Load Component_CB3”, the output capacitor should be capable to handle the output current and maintain the required output voltage. This component assists in smoothing out voltage variations and ensuring stability in the output.

The choice for “load component_CB3” contributes to the overall efficiency of the energy-circuit and its capacity to challenge the established laws of energy conservation by generating excess energy. In “Circuit Block 3”, the central objective is to investigate how the inputs derived from “Circuit Block 2”, can be effectively transformed into an Ohmic format suitable for standard circuit applications. This transformation is a pivotal step towards harnessing the innovative potential of the block and challenging the established laws of energy conservation.

Figure 7 is a block diagram depicting the developed energy-circuit, so far.

Remark 6 (Clarity on Energy Transformation in “Circuit Block 3”). The “Circuit Block 3” transforms the energy-circuit from a non-Ohmic to an Ohmic state, not aiming for excess power generation. It acts as a bridge to align the energy-circuit with conventional electrical systems, ensuring compatibility. With intentional higher power input than “Circuit Block 1”, as shown in

Table 2, it facilitates smooth integration into existing infrastructure, utilizing excess power for voltage boost. This design emphasizes practicality and adaptability to contemporary electrical and electronic technologies.