Submitted:

18 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

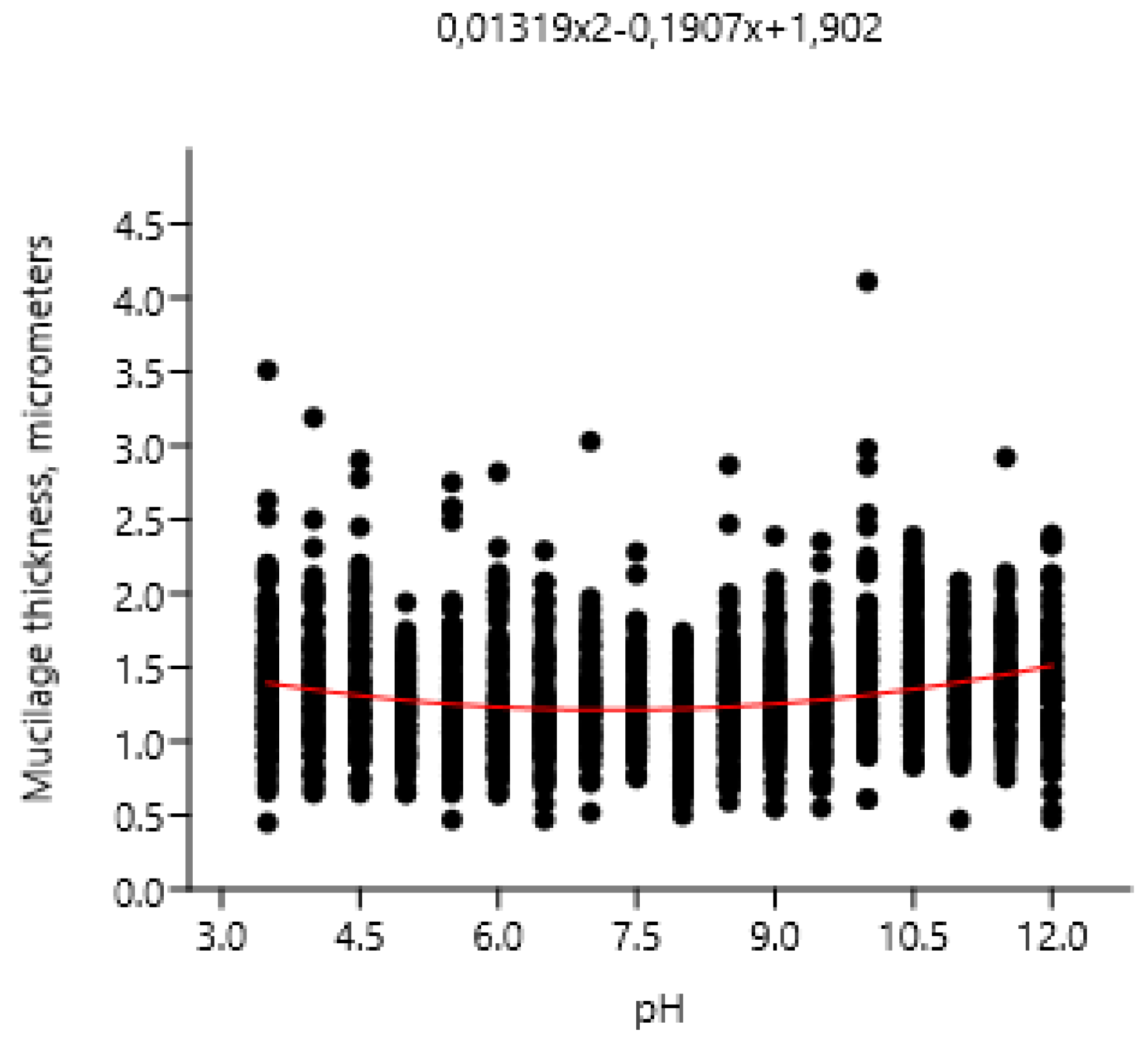

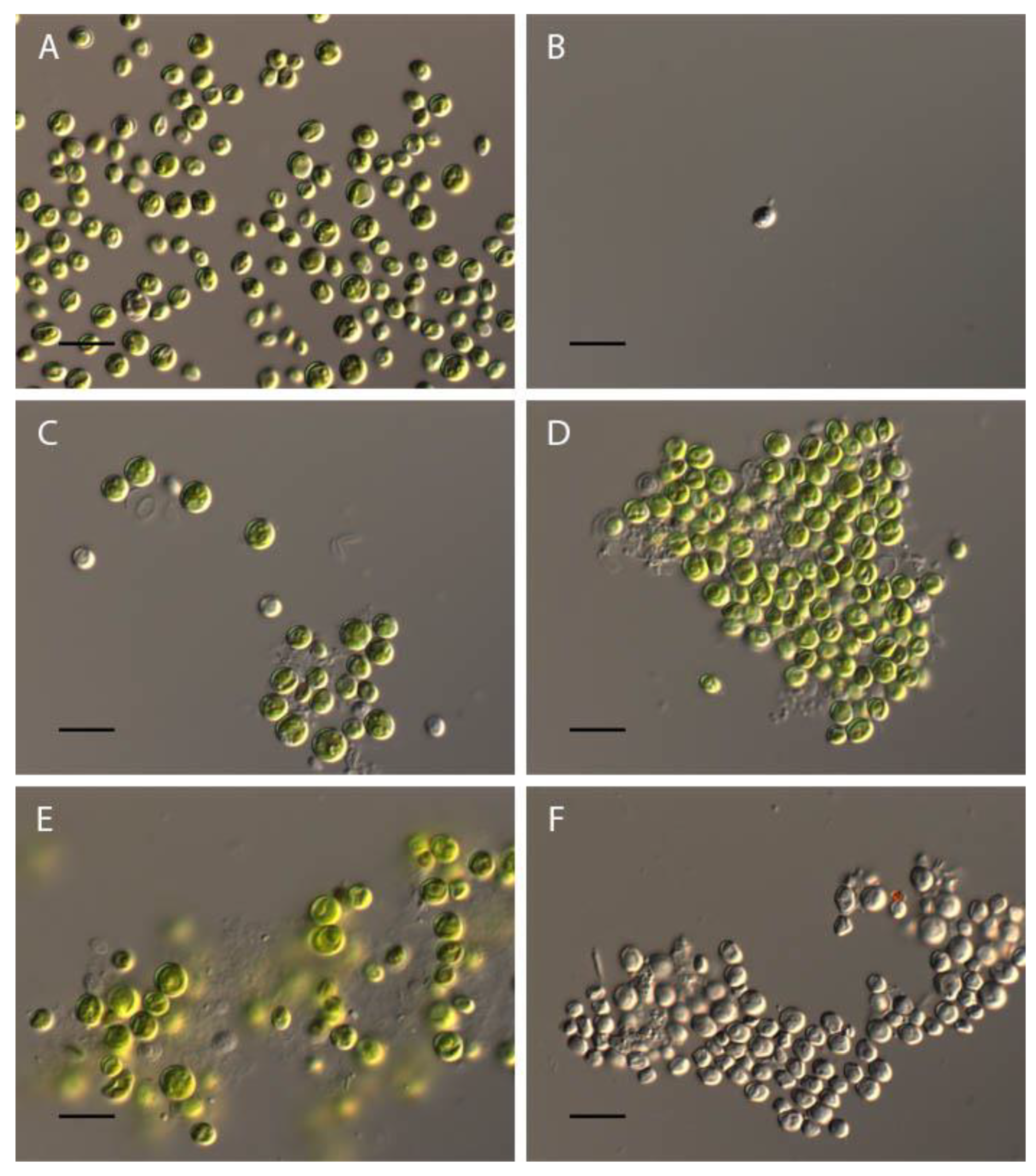

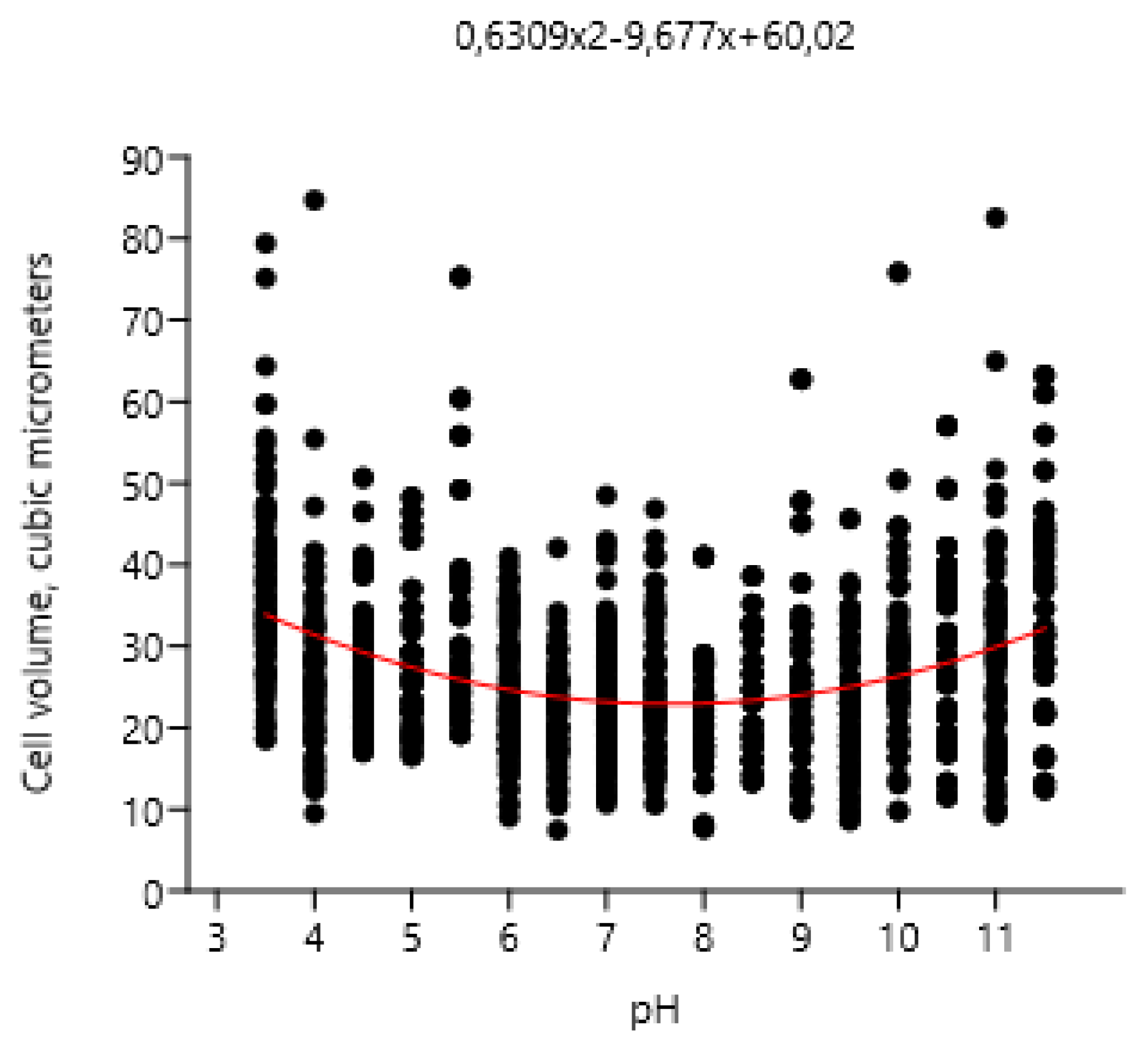

2.1. Bracteacoccus minor

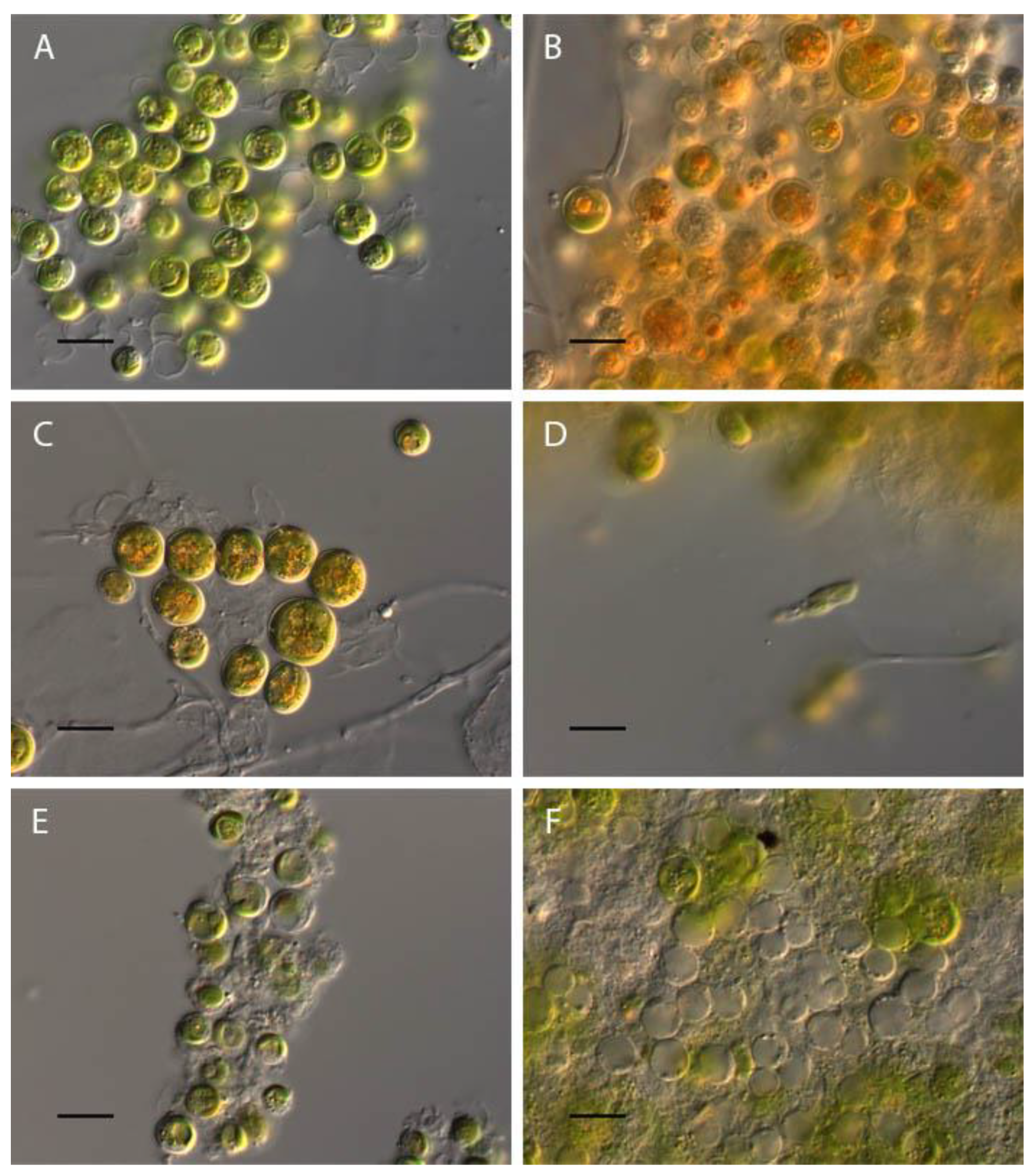

2.2. Chlorococcum infusionum

2.3. Chlorella vulgaris

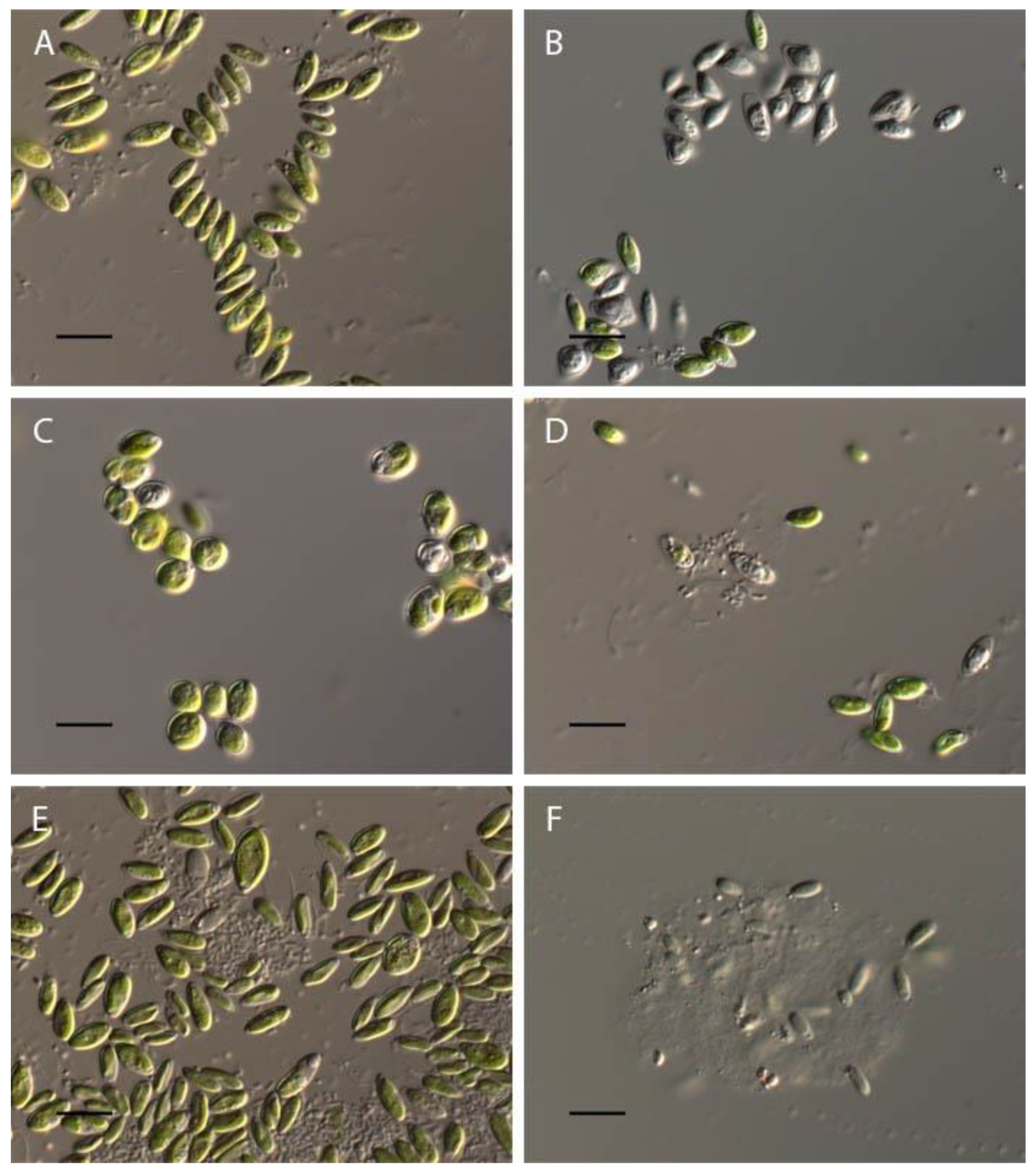

2.4. Pseudococcomyxa simplex

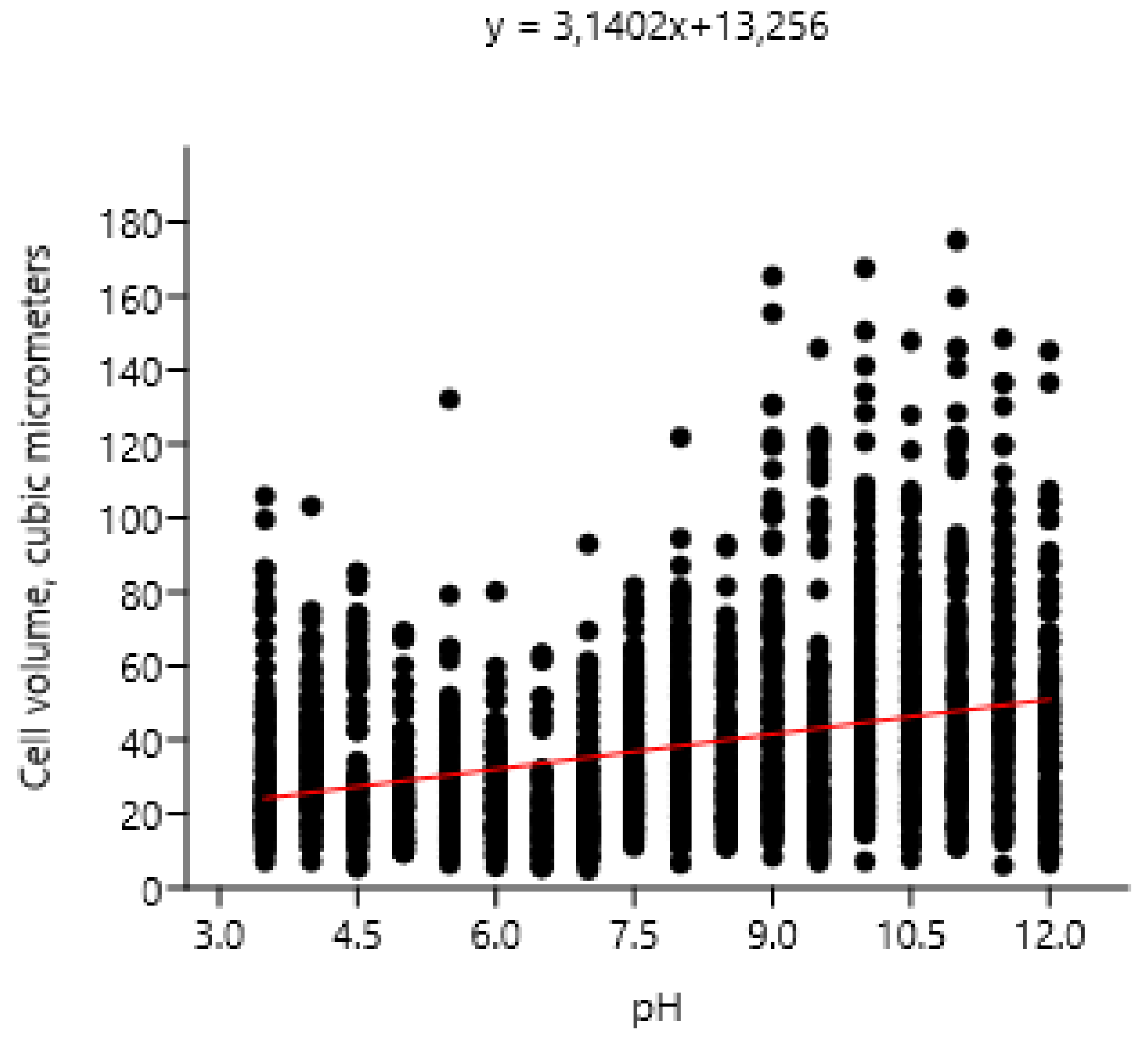

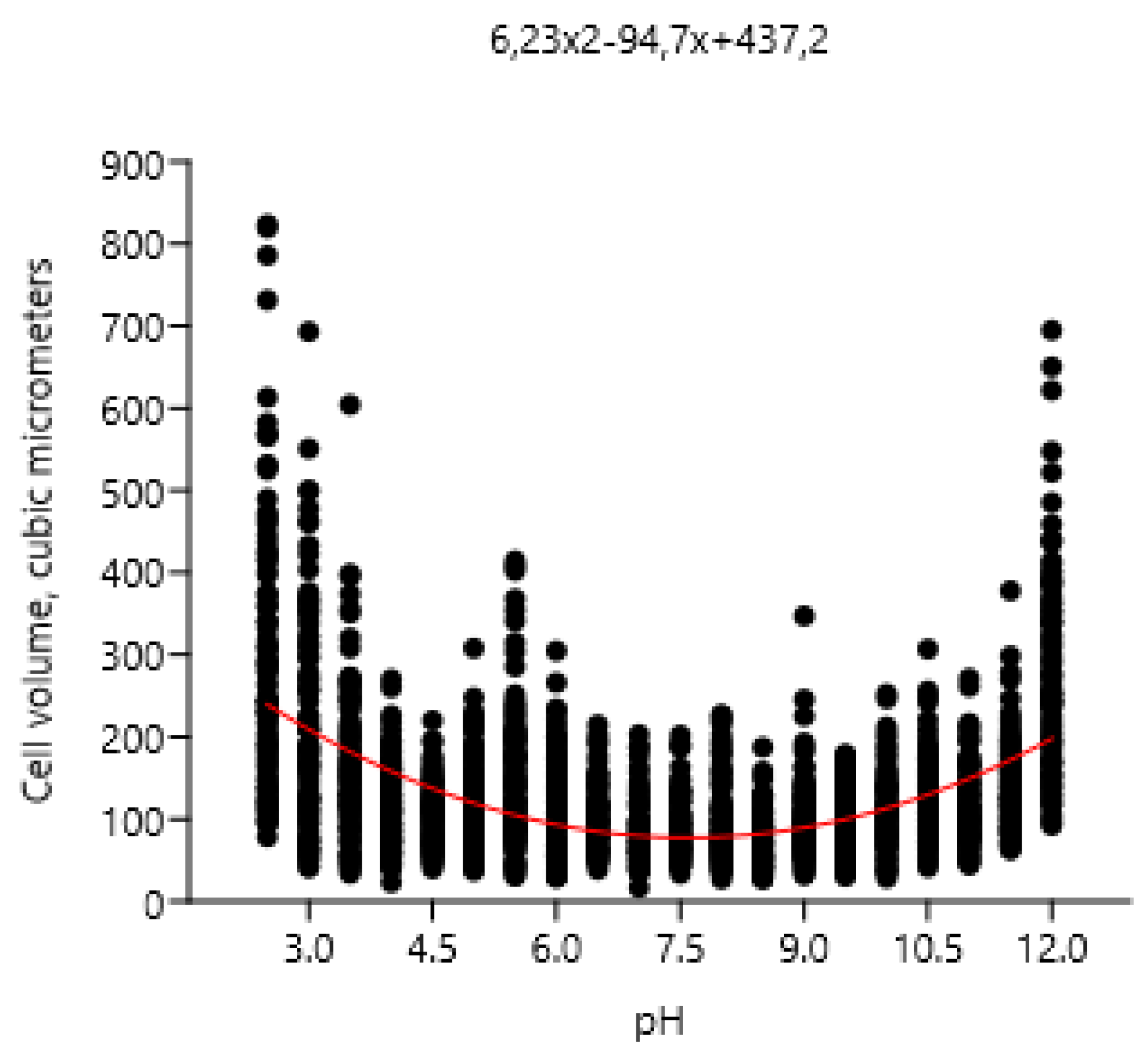

2.5. Vischeria magna

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains cultivation and methodic of experiments

4.2. Statistical analysis

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kushner, D.J. Microbial life in extreme conditions; Mir: Moscow, Russia, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Odum, Yu. Fundamentals of Ecology; Mir: Moscow, Russia, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.R.; Colman, B. Effect of external pH on carbon accumulation and CO2 fixation in blue-green alga. Proceedings of 5th Int. Congr. Photosynth. Malkidik, 89–90. 1980. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, H.; Balasubramanian, A.; Shantaram, M.V. Influence of pH on growth (14 C)-carbon metabolism and nitrogen fixation by two blue-green algae. Phycos 1980, 1980. 19, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin, J.; Grosso, A. The effects of pH on the growth of Chlorella vulgaris and its interactions with cadmium toxicity. Arch. Environ. Contam. And Toxicol 1991, 1991. 20, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.W. The effect of the pH on the division rate of the coccolithophonid Cricoshaera elongate. Journal of Phycology 1966, 2, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, R. J.; Trainor, F. R. Fasciculochloris, a new chlorosphaeracean alga from Connecticut soil. Phycologia 1965, 4, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, E.F.; Wann, F.B. Relation of hydrogen-ion concentration to growth of Chlorella and to the availability of iron. Bot. Gaz. 1926, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciasr, F. M. Effect of pH of the medium on the availability of chelated iron for Chlamydomonas mundane. The Journal of Protozoology 1965, 12, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, D.W.; Park, K. Bicarbonate utilization by marine phytoplankton in photosynthesis. Physiologia Plantarium 1962, 15, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.V.N. Determination of optimum pH range for the growth of Oocystis marssonii Lemm. in the three media differing in nitrogen source. Indian Journal of Plant Physiology 1963, 6, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, C.P. Theoretical aspects of the control of pH in natural sea water and synthetic culture media for marine algae. Botanica Marina 1966, 9, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikemori, M. , Noshida, K. Inorganic carbon sourse and the inhibitory effect of diamox on the photosynthesis of marine algae, Ulva pertusa. Ann. Rept. Noto Mar. Lab. 1967, 7, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E.A.; Tregunna, E.B. Bicarbonate ion assimilation in photosynthesis by Sargassum muticum. Canadian Journal of Botany 1968, 46, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J. The mechanism of photosynthetic use of bicarbonate by Hydrodictyon africanum. Exp. Bot. 1968, 46, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaili, Z. , Asker M.S., El-Sayed S., Kobbia I.A. Responces of Dunaliella bardawil and Chlorella ellipsoidea to pH stress. Acta Bot. Hung. 2010, 52, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabir, T.F.; Noor Abbood, H.A.; Salman, F.S.; Hafit, A.Y. Influence of pH, pesticide and radiation interactions on the chemical composition of Chlorella vulgaris algae. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 722, 012046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollerbach, M.M.; Shtina, E.A. Soil Algae; Nauka: Leningrad, Russia, 1969; p. 228. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.C.; Kahlert, M.; Kelly, M.G. Interactions between pH and nutrients on benthic algae in streams and consequences for ecological status assessment and species richness patterns. Science of The Total Environment 2013, 444, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, B.T.; Rajan, R.; Saranyamol, S. T.; Bhagya, M. V. influence of pH on the diversity of soil algae. Journal of Global Biosciences 2017, 6, 5088–5094. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie, M.; Le Faucheur, S.; Boullemant, A.; Fortin, C.; Campbell, P.G.C. The influence of pH on algal cell membrane permeability and its implications for the uptake of lipophilic metal complexes. Journal of Phycology, 48. [CrossRef]

- Černá, K.; Neustupa, J. The pH-related morphological variations of two acidophilic species of Desmidiales (Viridiplantae) isolated from a lowland peat bog, Czech Republic. Aquatic Ecology 2010, 44, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtina, E.A.; Gollerbach, M.M. Ecology of the soil algae; M.: Nauka, 1976. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, V.M. Soil and aerophilic green algae (Chlorophyta: Tetrasporales, Chlorococcales, Chlorosarcinales); Nauka, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1998; 351 p.

- Kostikov, I.; Romanenko, P.; Demchenko, P.; Darienko, T.M.; Mikhayljuk, T.I.; Rybchinskiy, O.V.; Solonenko, A.M. Soil Algae of Ukraine; Phytosotsiologichniy Center: Kiev, Ukraine, 2001; p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- Büdel, B.; Darienko, T; Deutschewitz, K. ; Dojani, S.; Friedl, T.; Mohr, K.I.; Salisch, M.; Reisser, W.; Weber, B. Southern African biological soil crusts are ubiquitous and highly diverse in drylands, being restricted by rainfall frequency. Microbial Ecology 2009, 57, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Škaloud, P. Species composition and diversity of aero-terrestrial algae and cyanobacteria of the Boreč Hill ventaroles. Fottea 2009, 9, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettl, H. , Gärtner G. Syllabus der Boden-, Luft- und Flechtenalgen, S: Fischer Verlag, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lukešová, A.; Hoffmann, L. Soil algae flora from acid rain impacted forest areas of the Krušne hory Mts. 1. Algal communities. Vegatatio 1996, 125, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.M.; Witton, B.A.; Brook, A.J. The freshwater algal flora of the British Isles: an identification guide to freshwater and terrestrial algae; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2005; 702 p.

- Johansen, J.R.; Rushfort, S.R.; Brotherson, J.D. The algal flora of Navajo National Monumant, Arizona, U.S.A. Nova Hedwigia 1983, 38, 501–553. [Google Scholar]

- Broady, P.A. Diversity, distribution and dispersal of Antarctic terrestrial algae. Biodiversity and Conservation 1996, 5, 1307–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukešova, A. Soil algae in brown coal and lignite post-mining areas in Central Europe (Czech Republic and Germany). Restoration Ecology. 2001, 9, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flechtner, V.R.; Johansen, J.R. , Belnap, J. The biological soil crusts of the San Nicolas Island: enigmatic algae from a geographically isolated ecosystems. Western North American Naturalist 2008, 68, 405–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskvich, N.P. The experience of using algae in the study of the sanitary state of the soil. Botanical Journal 1973, 58, 412–416. [Google Scholar]

- Novakovskaya, I.V.; Patova, E.N. Soil algae of spruce forests and their changes in conditions of aerotechnogenic pollution. Komi Scientific Center: Syktyvkar, Russia, 2012. 128 p.

- Novichkova-Ivanova, L.N. Changes of synusions of soil algae of Franz Josef Land. Botanical Journal 1963, 47, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Shtina, E.A. Soil algae as pioneers of the overgrowth of technogenic substrates and indicators of the state of disturbed lands. Journal of General Biology 1985, 46, 435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Neganova, L.B.; Shilova, I.I.; Shtina, E.A. Algoflora of technogenic sands of oil and gas producing areas of the Middle Ob region and the impact of oil pollution on it. Ecology 1978, 3, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. . AlgaeBase. https://www.algaebase. 22 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaštovska, K.; Elster, J.; Stibal, M.; Šantrůčkova, H. Microbial assemblages in soil microbial succession after glacial retreat in Svalbard (High Arctic). Microbial Ecology 2005, 50, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, Sh.R.; Johansen, J.R.; Lowe, R.L. Epilithic aerial algae of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Biologia, Bratislava.

- Johansen, J.R.; Lowe, R.; Gomez, Sh.R.; Kociolek, J.P.; Makosky, S.A. New algal records for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, U.S.A., with an annotated checklist of all reported algal species for the park. Algological Studies. [CrossRef]

- Shtina, E.L.; Bolyshev, N.I. Algae communities in soils of dry and desert steppes. Botanical Journal 1963, 48, 670–680. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, J.; Whitton, B. Effect of pH on growth of acid stream algae. Eur. J. Phycol. 1976, 11, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuppini, A.; Gerotto, C.; Baldan, B. Programmed cell death and adaptation: two different types of abiotic stress response in a unicellular chlorophyte. Plant and Cell Physiology 2010, 51, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastien, C.; Côté, R. Effects du cuirve sur l’ultrastructure de Scenedesmus quadricauda et Chlorella vulgaris. Inf. Rev. Gesamt. Hydrobiol. 1989, 74, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, S.C. Effects of different factors on the akinete germination in Pithophora oedogonia (Mont.) Wittrock. J.Basic Microbiol. 1986, 26, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, S.; Schumann, R.; Karsten, U. Effect of temperature and photon influence rate on growth rates of two epiphytic diatom species from Kongsfjorden. Ber.Polar- und Meeresforsch. 2004, 492, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.G.; Jin, X.C.; Sun, L.; Zhong, Y.; Dai, S.G.; Zhuang, Y.Y. Influence of рН on growth and species composition of algae in freshwater ecosystems. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2005, 24, 294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Y.-J.; Wang, X.-L.; Yang, R.-J.; Zhang, Y.-Y. Influence of Cu (II) on growth of 8 species of marine microalgae. Environ.Sci. 2006, 27, 720–726. [Google Scholar]

- Middelboe, A.L.; Hansen, P.J. Direct effects of pH and inorganic carbon on macrolalgal photosynthesis and growth. Mar. Biol. Res. 2007, 3, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, S.M.; Hitchcock, J.N.; Davie, A.W.; Ryan, D.A. Growth responses of Cyclotella meneghiniana (Bacillariophyceae) to various temperatures. J. Plankton Res. 2010, 32, 1217–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigova, L.; Ivanova, N.; Gacheva, G.; Andreeva, R.; Furnadzhieva, S. Response of Trachydiscus minutes (Xanthophyceae) to temperature and light. Journal of Phycology.

- Karandashova, I.V.; Elanskaya, I.V. Genetic control and mechanisms of cyanobacteria resistance to salt and hyperosmotic stress. Genetics 2005, 41, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backor, M.; Fahselt, D.; Davidson, R.D.; Wu, C.T. Effects of copper on wild and tolerant strains of the lichen photobiont Trebouxia erici (Chlorophyta) and possible tolerance mechanism. Arch. Environ. Contam. And Toxicol. 2003, 45, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovár, J.; Stavrou, E.; Kimákova, T.; Kadukova, J. , Bačkor, M. Influence of long-term exposure to copper on the lichen photobiont Trebouxia erici and free-living algae Scenedesmus quadricauda. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 63, 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Messerli, M.A.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A.; Zettler, E.; Jung, S.-K.; Smith, P.J.S.; Sogin, M.L. Life in acidic pH imposes as increased energetic cost for a eukaryotic acidophile. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, A. W.; & Toulibah, H. E.; & Toulibah, H. E. Effect of salinity and pH on fatty acid profile of the Green Algae Tetraselmis suecica. Journal of Petroleum & Environmental Biotechnology 2017, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.W.; McLaughlin, F.; Lovejoy, C.; Carmack, E.C. Smallest algae thrive as the Arctic Ocean freshens. Science 2009, 326, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratbak, G. Bacterial biovolume and biomass estimation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1985, 49, 1488–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunda, W.G. , Huntsman, S.A. Interrelated influence of iron, light and cell size on marine phytoplankton growth. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Weisse, T.; Scheffel, U.; Stadler, P.; Foissner, W. Local adaptation among geographically distant clones of the cosmopolitan freshwater ciliate Meseres corlissi. II. Response to pH. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 2007, 47, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, H.; Dürselen, C.-D.; Kirschtel, D.; Pollingher, U.; Zohary, T. Biovolume calculation for pelagic and benthic microalgae. Journal of Phycology 1999, 35, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, D. Geometric models for calculating cell biovolume and surface area for phytoplankton. Journal of Plankton Research 2003, 25, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borics, G.; Lerf, V.; Enikő, T.; Stanković, I.; Pickó, L.; Béres, V.; Várbíró, G. Biovolume and surface area calculations for microalgae, using realistic 3D models. The Science of the Total Environment 2021, 773, 145538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, Z. V. Light absorption and size scaling of the lightlimited metabolism in marine diatoms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2001, 46, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.A.; Kubler, J. E. New light on the scaling of metabolic rate with the size of algae. Journal of Phycology 2002, 38, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.P.Y. The allelometry of algal growth rates. Journal of Plankton Research 1995, 17, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.P.Y. , Peters, R.H. The allelometry of algal respiration. Journal of Plankton Research 1995, 17, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarthou, G.; Timmermans, K.R.; Blain, S.; Treguer, P. Growth physiology and fate of diatoms in the ocean: a review. Journal of Sea Research 2005, 53, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, F.E.; Crawford, R.M.; Mann, D.G. The Diatom: Biology and Morphology of the Genera. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK; 1990. 747 p.

- Irwin, A.J.; Finkel, Z.V.; Schofield, O.M.E.; Falkowski, P.G. Scaling-up from nutrient physiology to the size-structure of phytoplankton communities. Journal of Plankton Research 2006, 28, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agusti, S. Allometric scaling of light absorption and scattering by phytoplankton cells. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1991, 48, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint, I.; Pomroy, A. Allometric estimation of the productivity of phytoplankton assemblages. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1988, 47, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.A.; Oliver, M.J.; Beaulieu, J.M.; Knight, C.A.; Tomanek, L.; Moline, M.A. Correlated evolution of genome size and cella volume in diatoms (Bacillariophyceae). Journal of Phycology 2008, 44, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, M. , Pedersen, M.F., Sand-Jensen, K. Size-dependent nitrogen uptake in micro- and macroalgae. Marine Ecology Progress Series 1995, 118, 247–253. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S. Life's Devices: The Physical World of Animals and Plants. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA, 1988; 369 p.

- Borics, G.; Várbíró, G.; Falucskai, J.; Végvári, Z.; T-Krasznai, E.; Görgényi, J.; B-Béres, V.; Lerf, V. A two-dimensional morphospace for cyanobacteria and microalgae: Morphological diversity, evolutionary relatedness, and size constraints. Freshw. Biol. 2023, 68, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polishuk,V. ; Kostikov, I.Yu.; Taran, N.Yu.; Voitsitsky, V.M.; Budzanivska, I.; Khyzhnyak, S.; Trokhymets, V.M. The complex studying of Antarctic biota. Ukr. Antarct. J. 2009, 8, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neustupa, J.; Skaloud, P. Diversity of subaerial algae and cyanobacteria on tree bark in tropical mountain habitats. Biologia 2008, 63, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E.; Kramer, H. Physiologische untersuchungen an einer ungewöhnlich saureresistenten Chlorella. Arch. Mikrobiol. 1960, 37, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimmler, H.; Weis, U. Dunaliella acidophila – life at pH 1.0. In Dunaliella, physiology, biochemistry and biotechnology. M. Avron, A. Ben Amotz. CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 1992; 99–133.

- Gross, W. Ecophysiology of algae living in highly acidic environments. Hydrobiologia 2000, 433, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, M.; Díaz, I.; Dominguez, A.; González Sánchez, A.; Muñoz, R. Microalgal biotechnology as a platform for an integral biogas upgrading and nutrient removal from anaerobic effluents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 2014. 48, 573–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sánchez, A.; Revah, S.; Deshusses, M.A. Alkaline biofiltration of H2S odors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 7398–7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Sánchez, A.; Revah, S. The effect of chemical oxidation on the biological 396 sulfide oxidation by an alkaliphilic sulfoxidizing bacterial consortium. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2007, 40, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Vandamme, D.; Muylaert, K. Microalgal and cyanobacterial cultivation: The supply of nutrients. Water Res. 2014, 65, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Morgado, M.; Alcántara, C.; Noyola, A.; Muñoz, R.; González-Sánchez, A. A study of photosynthetic biogas upgrading based on a high rate algal pond under alkaline conditions: Influence of the illumination regime. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 592, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaveson, M. M.; Stokes, P. M. 1989: Responses of the acidophilic Euglena mutabilis (Euglenophyceae) to carbon enrichment at pH 3. Journal of Phycology.

- Graham, J. M.; Arancibia-Avila, P.; Graham, L. E. Effects of pH and selected metals on growth of the filamentous green alga Mougeotia under acidic conditions. Journal of Limnology and Oceanography 1996, 41, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerloff-Elias, A.; Spijkerman, E.; Pröschold, T. Effect of external pH on the growth, photosynthesis and photosynthetic electron transport of Chlamydomonas acidophila Negoro, isolated from an extremely acidic lake (pH 2.6). Plant, Cell and Environment, 1218. [Google Scholar]

- Hoham, R.W.; Filbin, R.W.; Frey, F.M.; Pusack, T.J.; Ryba, J.B.; Mcdermott, P.D.; Fields, R.A. The optimum pH of the green snow algae, Chloromonas tughillensis and Chloromonas chenangoensis, from upstate New York. Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research. [CrossRef]

- Spijkerman, E.; Barua, D.; Gerloff-Elias, A.; Kern, J.; Gaedke, U.; Heckathorn, S.A. Stress responses and metal tolerance of Chlamydomonas acidophila in metalenriched lake water and artificial medium. Extremophiles 2007, 11, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ňancucheo, I.; Johnson, B.D. Acidophilic algae isolated from mine-impacted environments and their roles in sustaining heterotrophic acidophiles. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, M.R.; Senhorinho, G.N.A.; Scott, J.A. Microalgae under Environmental Stress as a Source of Antioxidants. Algal Res. 2020, 52, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B. The influence of environmental factors on the distribution of freshwater algae: An experimental study: II. The role of pH and the carbon dioxide-bicarbonate system. J. Ecol. [CrossRef]

- Novis, P. Taxonomy of Klebsormidium (Klebsormidales, Chlorophyceae) in New Zealand streams, and the significance of low pH habitats. Phycologia.

- Xing, R.; Ma, W.; Shao, Y.; Cao, X.; Chen, L.; Jiang, A. Factors that affect the growth and photosynthesis of the filamentous green algae, Chaetomorpha valida, in static sea cucumber aquaculture ponds with high salinity and high pH. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, A.W. Effects of temperature and pH on the kinetic growth of unialga Chlorella vulgaris cultures containing bacteria. Water Environment Research 1997, 69, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Gao, S.; Lopez, P.A.; Ogden, K.L. Effects of pH on cell growth, lipid production and CO2 addition of microalgae Chlorella sorokiniana. Algal Res. 2017, 28, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karemore, A.; Pal, R.; Sen, R. Strategic enhancement of algal biomass and lipid in Chlorococcum infusionum as bioenergy feedstock. Algal Res. 2013, 2, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.-Z.; Wu, H.-L.; Xie, K.; He, H.; Xiao, W. Extreme features of Chlorococcum sp. and rapid induction of ataxantin. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2007, 26, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shubert, E.; Rusu, L.E. ; Bartok, A-M.; Moncrieff, C.B. Distribution and abundance of edaphic algae adopted to higly acidic, metal rich soils. In Algae and Extreme Environments. J. Elster, O. Lhotsky. Nova Hedwigia 123. J. Cramer, Stuttgart, Germany, 2001; pp. 411–425.

- Agrawal, S.C. Factors affecting spore germination in algae — review. Folia Microbiologica 2009, 2009. 54, 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinetova, M.A.; Sidorov, R.A.; Medvedeva, A.A.; Starikov, A.Y.; Markelova, A.G.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Los, D.A. Effect of salt stress on physiological parameters of microalgae Vischeria punctata strain IPPAS H-242, a superproducer of eicosapentaenoic acid. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 331, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, Y.; Gao, X.; Jing, X.; Wang, J.; Dong, Y.; Cui, J.; Xue, H.; Li, Z.; Zhu, D. Effects of nitrogen source and NaCl stress on oil production in Vischeria sp. WL1 (Eustigmatophyceae) isolated from dryland biological soil crusts in China. J. Appl. Phycol, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukavský, J.; Kopecký, J.; Kubácˇ, D.; Kvíderová, J.; Procházková, L.; Řezanka, T. The alga Bracteacoccus bullatus (Chlorophyceae) isolated from snow, as a source of oil comprising essential unsaturated fatty acids and carotenoids. J. Appl. Phycol. [CrossRef]

- Remis, D.; Treffny, B.; Gimmler, H. Light-induced H+ transport across the plasma membrane of the acid-resistant green alga Dunaliella acidophila. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1994, 1994. 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gimmler, H. Acidophilic and acidotolerant algae. In Algal adaptations to environmental stresses. L.C. Rai, J.P. Gaur. Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; 259–290.

- Nixdorf, B.; Fyson, A.; Krumbeck, H. Review: plant life in extremely acidic water. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2001, 46, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzmil, B.; Wronkowski, J. Removal of phosphates and fluorides from industrial wastewater. Desalination 2006, 189, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenpour, S.F.; Hennige, S.; Willoughby, N.; Adeloye, A.; Gutierrez, T. Integrating micro-algae into wastewater treatment: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishoff, H.; Bold, H. Phycological Studies. IV. Some algae from enchanted rock and related algae species. Univ. Texas. Publ.: Texas, USA, 1963; 6318: 91–95.

- Jongman, R.H.G.; Ter Braak, C.J.F.; Van Tongeren, O.F.R. Data Analysis in Community and Landscape Ecology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; 29–50.

- Sun, J.; Liu, D. Geometric models for calculating cell biovolume and surface area for phytoplankton. Journal of Plankton Research 2003, 25, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Past: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. 2001. Palaeontol. Electron, 1–9. 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.05. [CrossRef]

| Taxa | pH limits | Morphological and physiological features changes at pH< 4 | Morphological and physiological features at pH>10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bracteacoccus minor | 4-10 | Complete discoloration and destruction of cells, appearance of orange granules | Discoloration and destruction of cells |

| Chlorococcum infusionum | 4-9,5 | Discoloration and destruction of cells, increase of mucilage production, appearance of large granules in cytoplasm | Discoloration and destruction of cells, increase of mucilage production, appearance of large granules in cytoplasm |

| Chlorella vulgaris | 4-11,5 | Discoloration of cells | Discoloration of cells |

| Pseudococcomyxa simplex | 4-11,5 | Discoloration and "wrinkling" of cells, appearance of the almost round cells | Discoloration of cells |

| Vischeria magna | 3,5-11 | Discoloration and appearance of the orange granules in cells, maximal zoospores production at pH 3.5, increasing of cell volume | Discoloration of cells |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).