Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

20 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Experimental Program

2.2. Materials

- Sporosarcina pasteurii is a Gram-positive aerobic bacterium. It was provided by Moji Technology Co., Ltd.

- Calcium lactate was used as a nutrient source for pasteurii. It was purchased from Huacheng Industrial Raw Materials Co., Ltd.

- Yeast extract (YE) is the concentrated content of yeast cells. It can be used as a nutritional supplement. It contains a large amount of protein, amino acids, and the vitamin B group. It was purchased from Huacheng Industrial Raw Materials Co., Ltd.

- Calcium acetate was used as a supplementary source of external calcium ions during the maintenance of the specimens. It was purchased from Huacheng Industrial Raw Materials Co., Ltd.

- Urea is an organic compound composed of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen, and was purchased from Huacheng Industrial Raw Materials Co., Ltd.

- The cement was a locally produced Type I Portland cement with a specific gravity of 3.15 and a fineness of 3550 cm2/g; its chemical composition is shown in Table 3.

- The water was general tap water, which is in line with the general quality requirements of concrete mixing water.

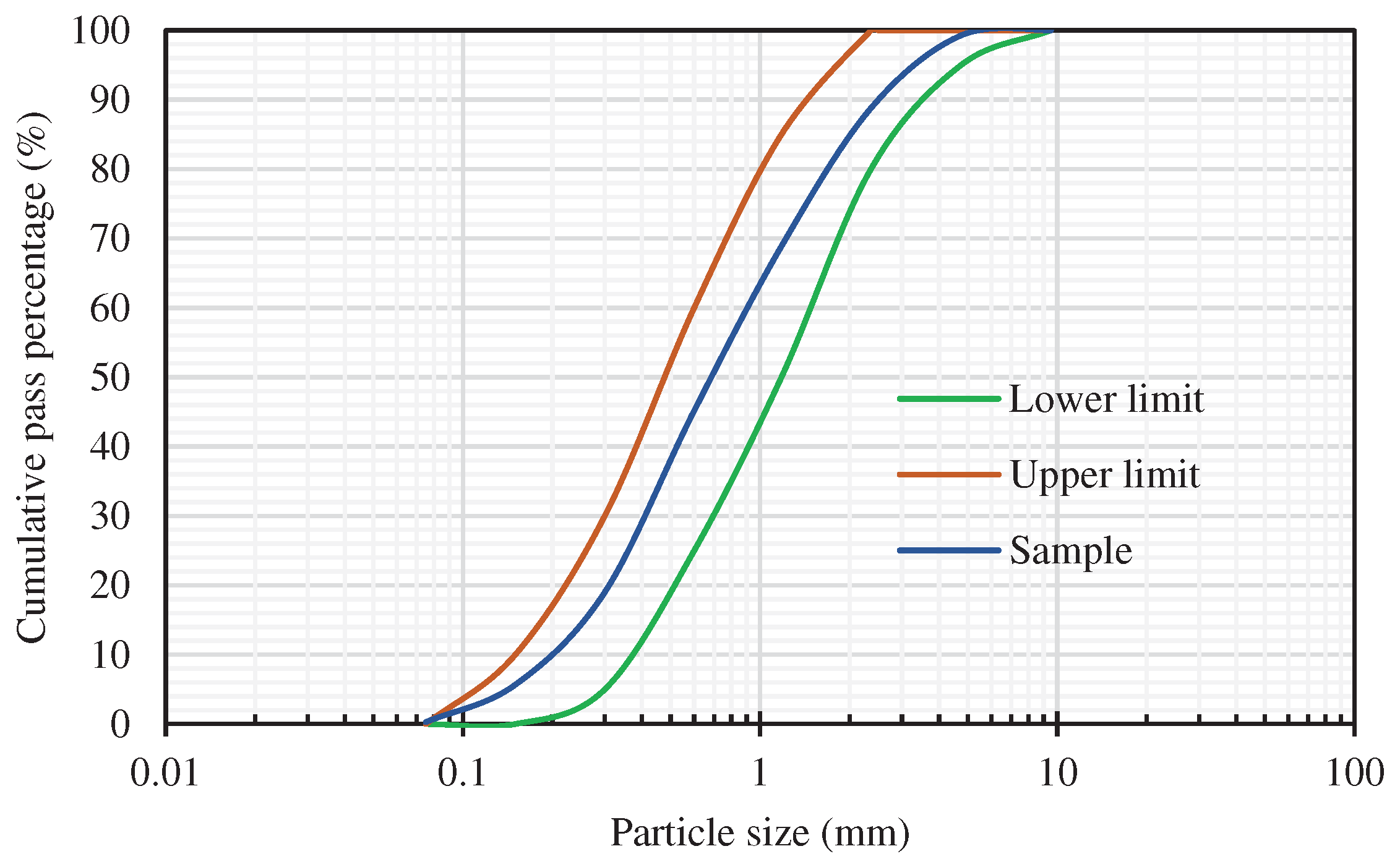

- The fine aggregate was a natural river sand with an FM value of 2.7 and a 24-hour water absorption rate of 1.15%. Its particle size distribution curve is shown in Figure 3.

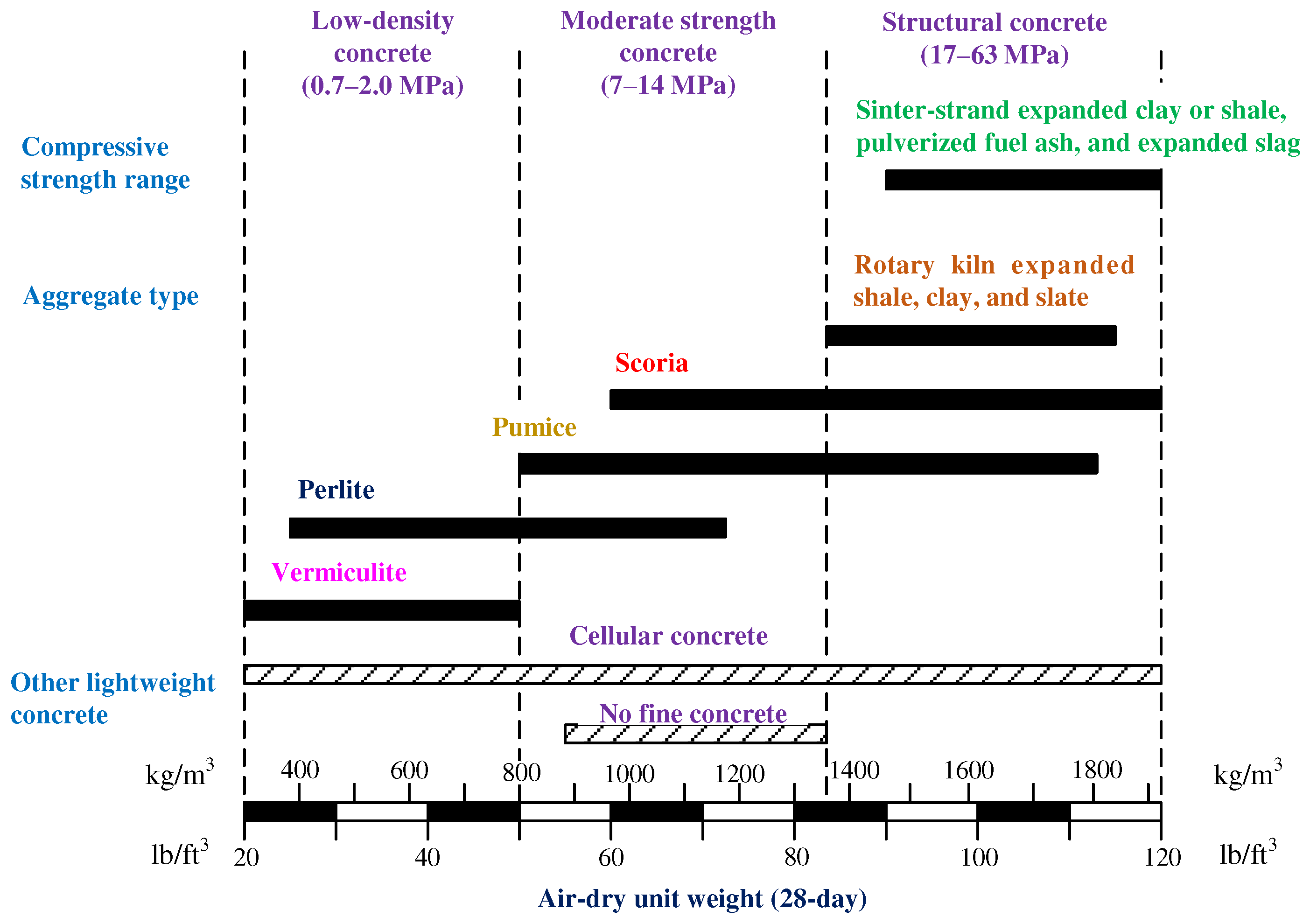

- The original maximum particle size of the LWA was 3/4 inches; the crushed maximum particle size of the LWA was 3/8 inches; the particle density was 1.57 g/cm3; the dry unit weight was 927 kg/m3; the specific gravity was 2.65; the water absorption was 6%; and the crushing strength was 12.67 MPa.

- The superplasticizer was a product of the Taiwan Sika Company; its chemical composition was water-modified polycarboxylate, and it met the requirements of C494/C494M-17 [50] Type F.

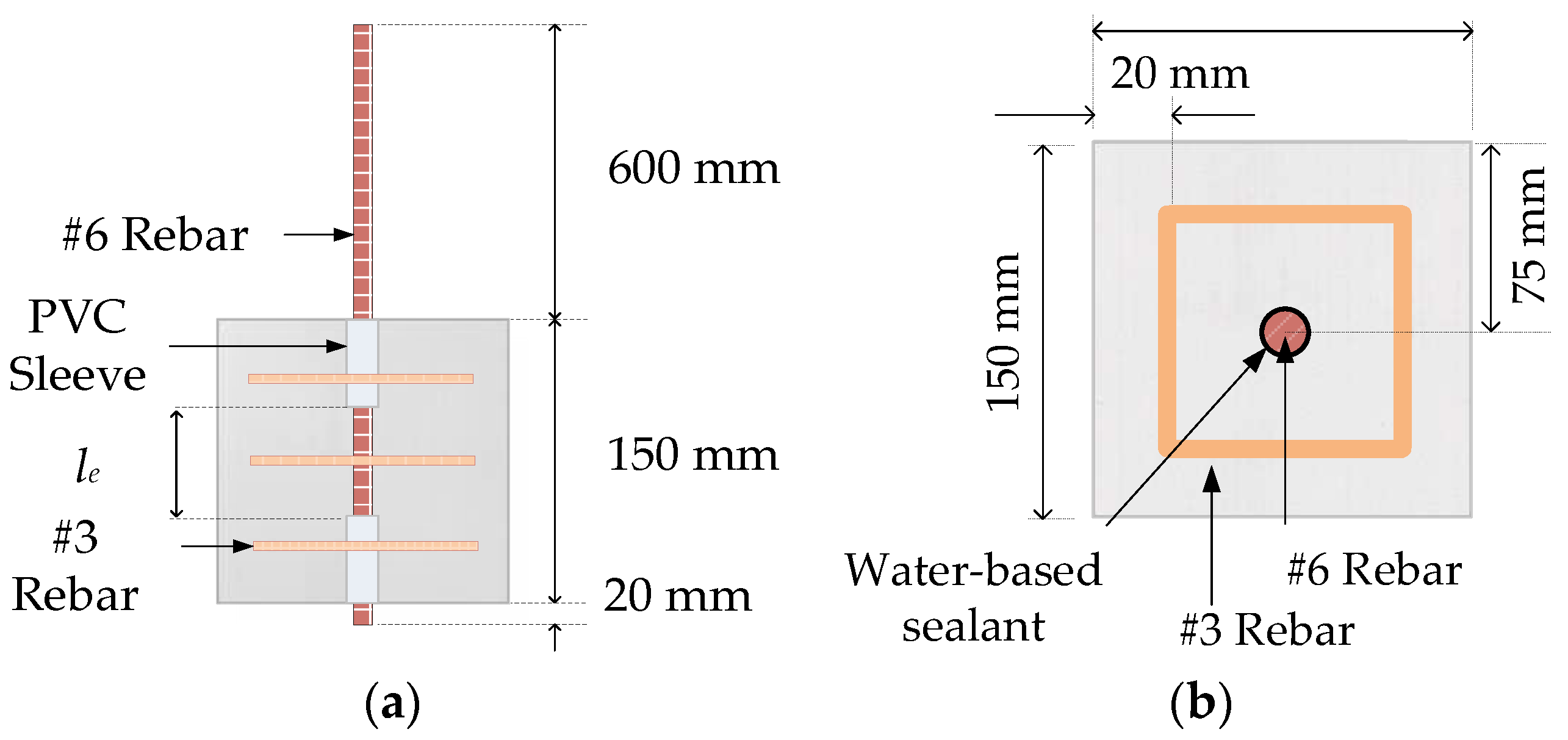

- For the longitudinal main reinforcement of the pull-out, #6 rebar was used. Its physical and mechanical properties are shown in Table 6.

2.3. Strain Implantation

- (a)

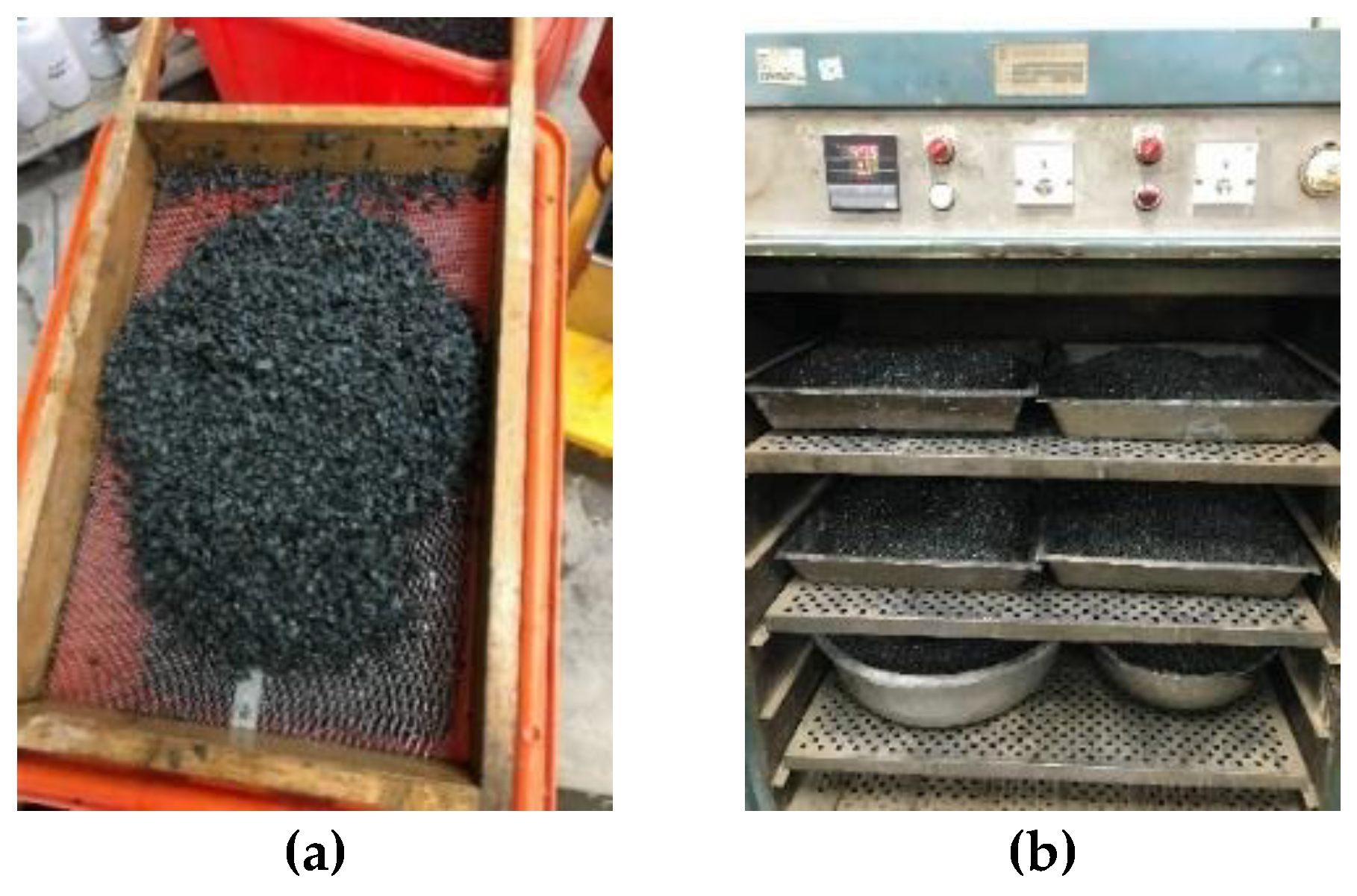

- The LWAs were washed with clean water. Afterwards, the LWAs were dried to a dry state. Then, the LWAs were immersed in a nutrient source solution containing calcium lactate (80 g/L) and yeast extract (1 g/L) for 60 min. The samples were stirred every 10 minutes, as shown in Figure 6.

- (b)

- The soaked LWA was taken out and drained. Then, the drained LWA was evenly spread on the iron plate and placed in an oven at a constant temperature of 37 °C to dry for 5 days, as shown in Figure 7.

- (c)

- The previous two steps were repeated once.

- (d)

- The nutrient-containing LWAs were immersed in the bacterial spore solution for 60 minutes, during which the pump continued to run and stir every 10 minutes, as shown in Figure 8.

- (e)

- After the LWAs were soaked, they were taken out and drained, spread on an iron plate, and then placed in an oven at 37 °C to dry for five days.

2.4. Mix Proportions of LWAC

2.5. Casting and Curing of Specimens

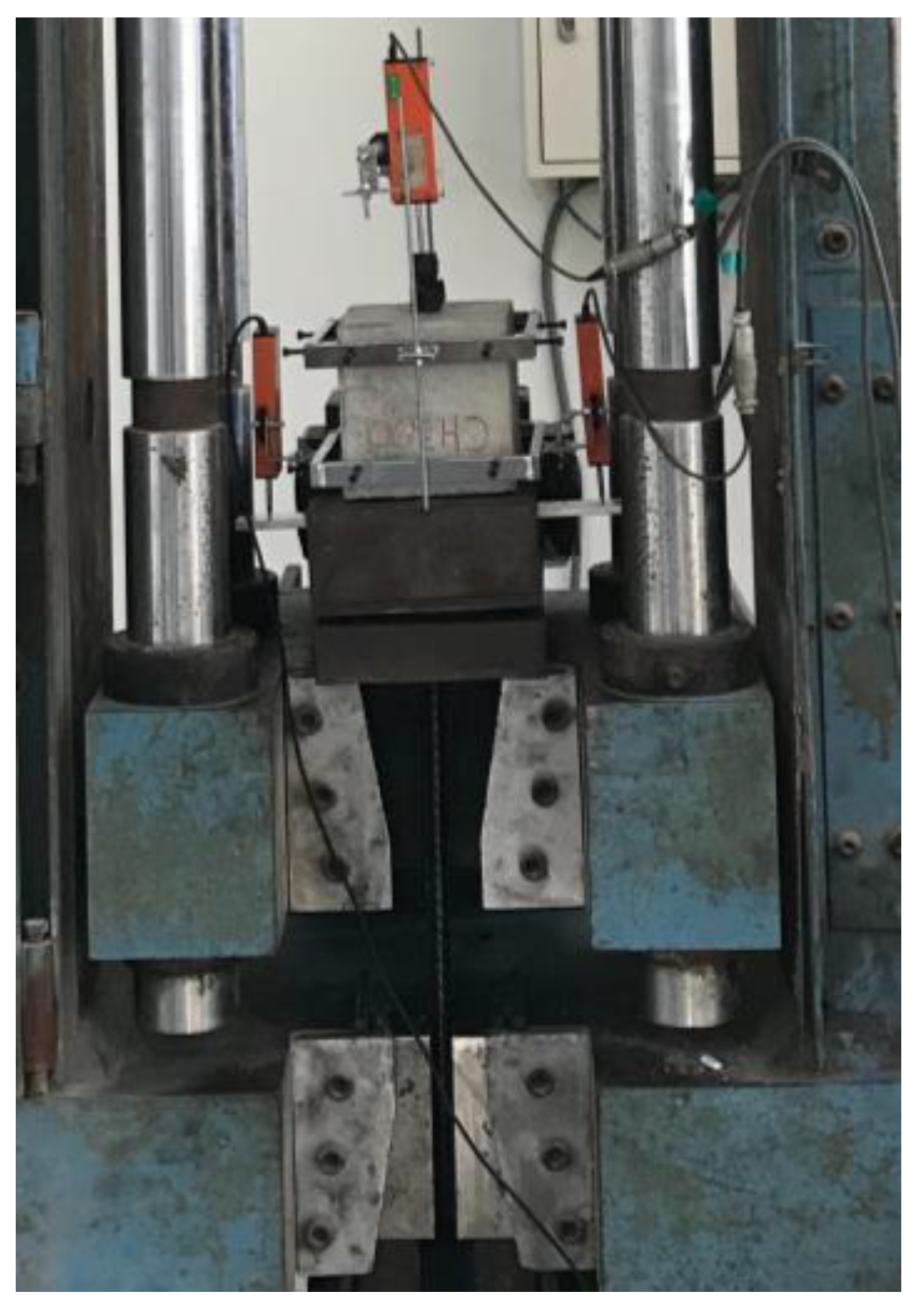

2.6. Test Methods and Data Analysis

3. Experimental Results and Discussions

3.1. Results of the Fresh Properties Test

3.2. Results of the Compression Test

3.2.1. Compressive Strength and Elastic Modulus of First Compression Test

3.2.2. Compressive Strength of Secondary Compression Test

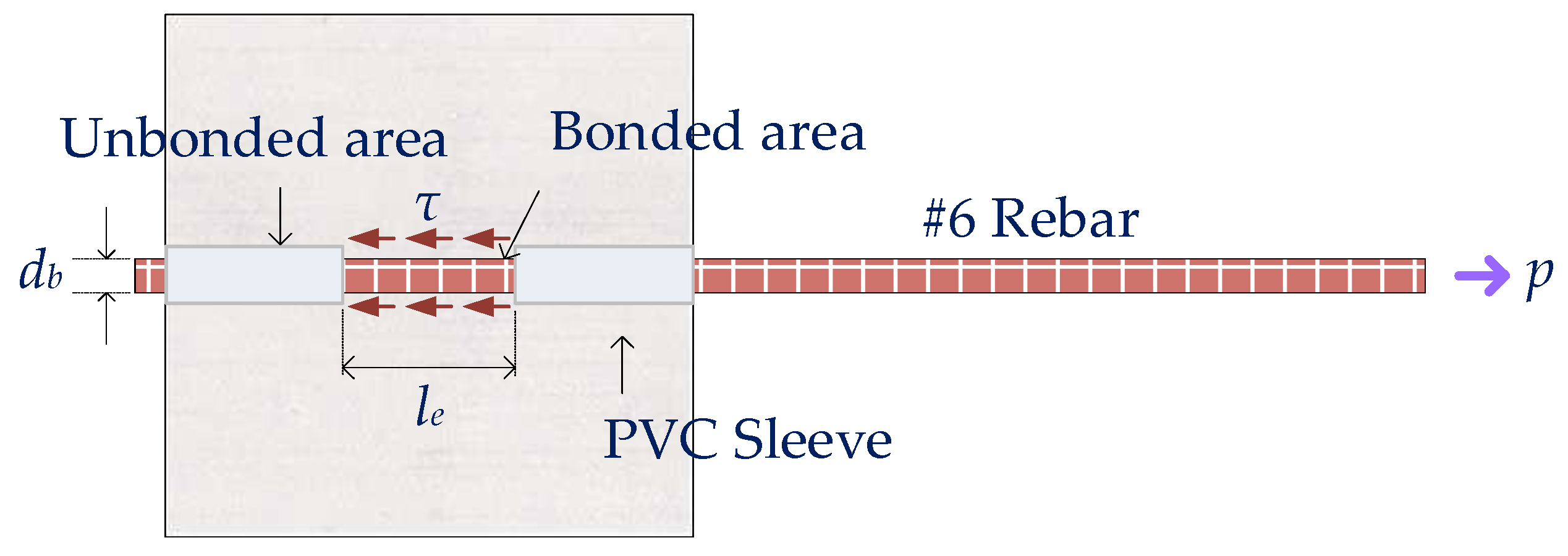

3.3. Results of the Pull-Out Test

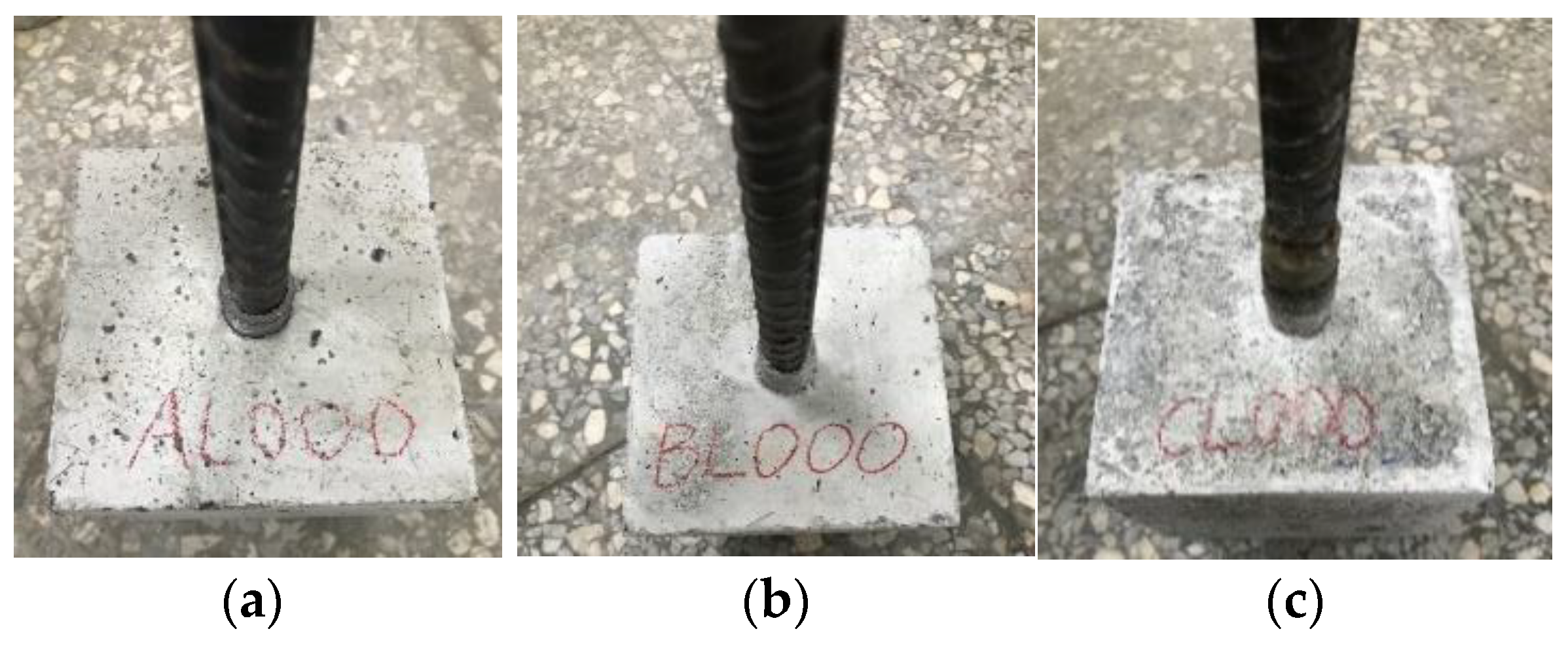

3.3.1. Bond Strength of First Pull-Out Test

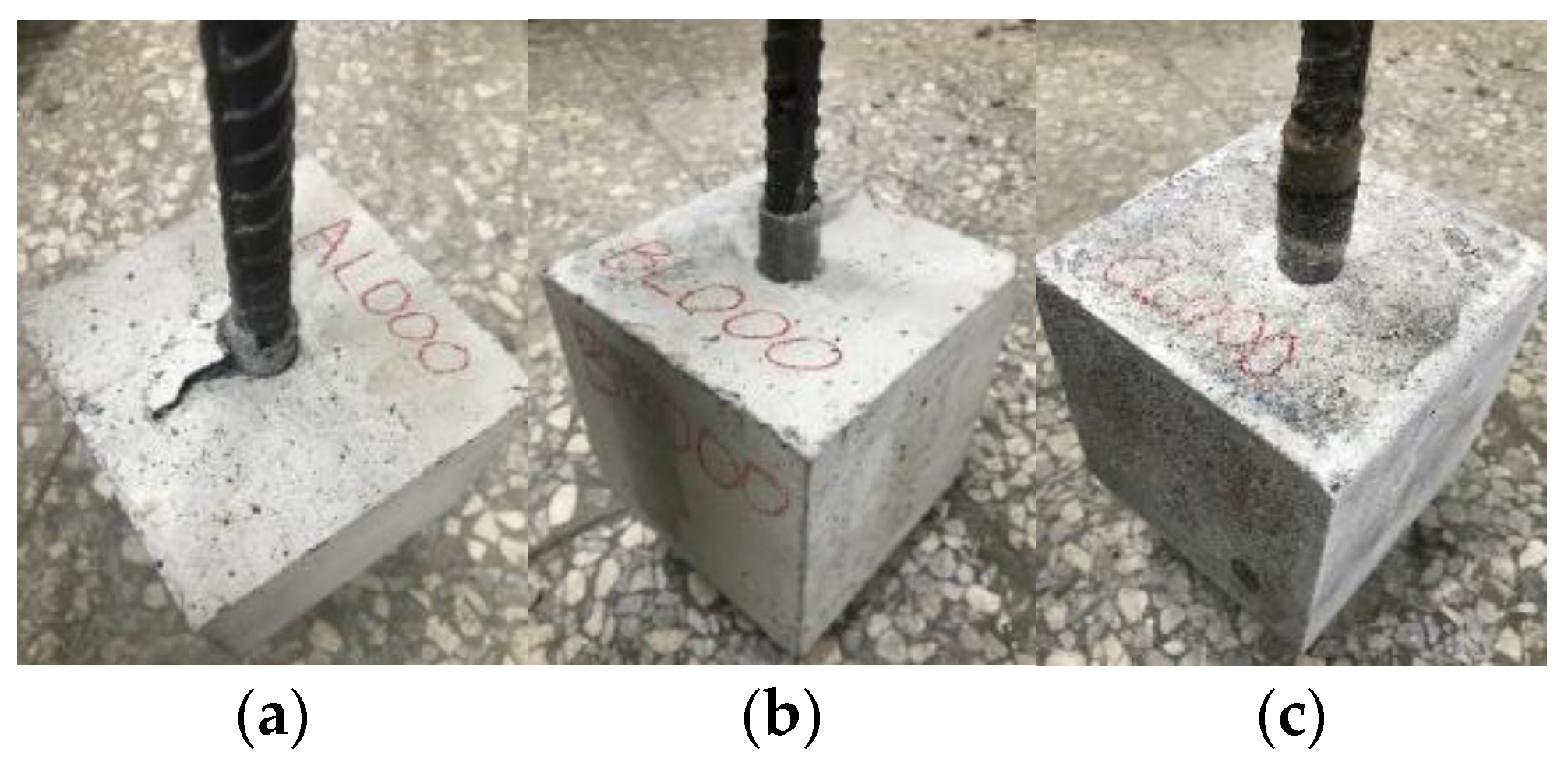

3.3.2. Bond Strength of Secondary Pull-Out Test

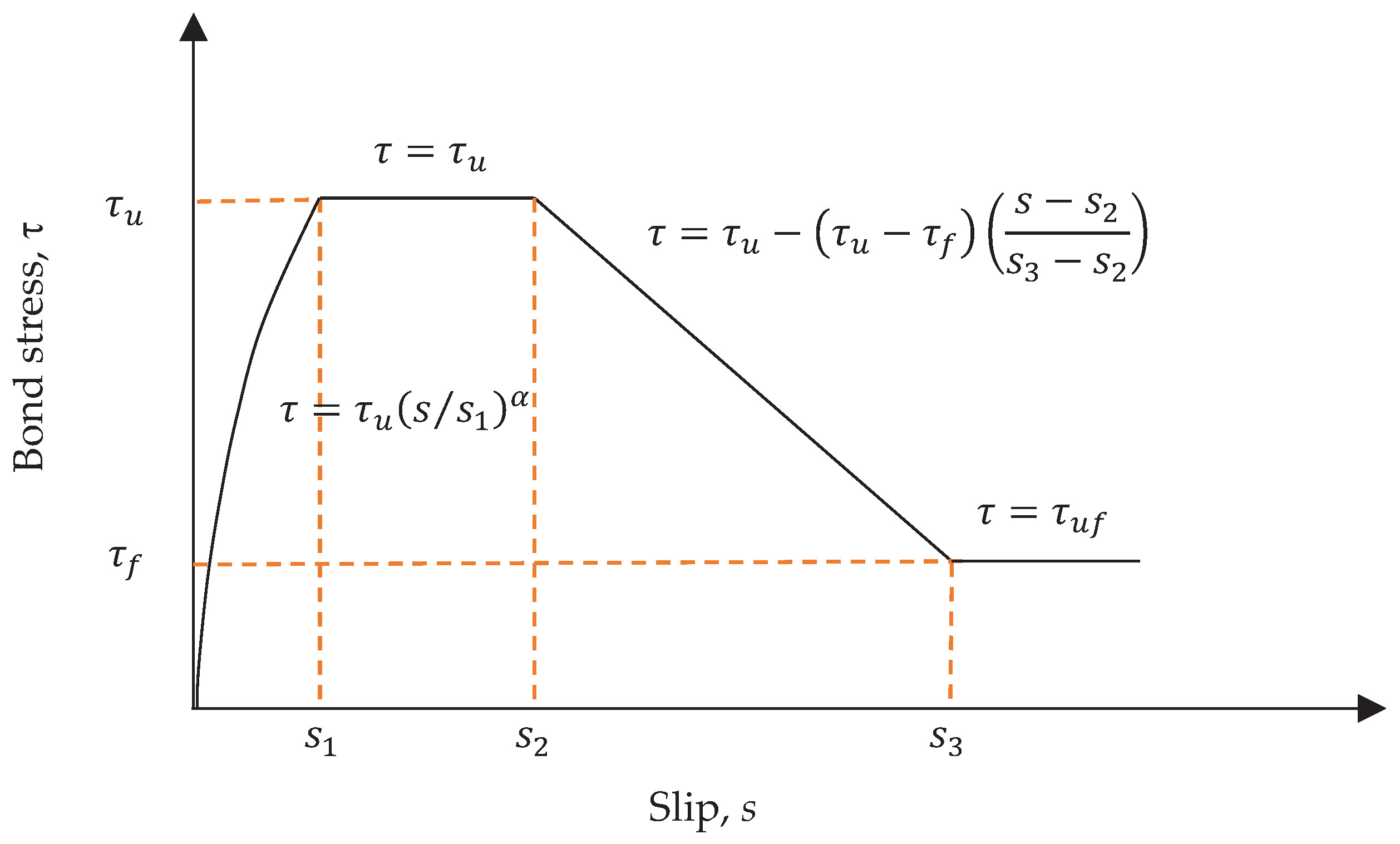

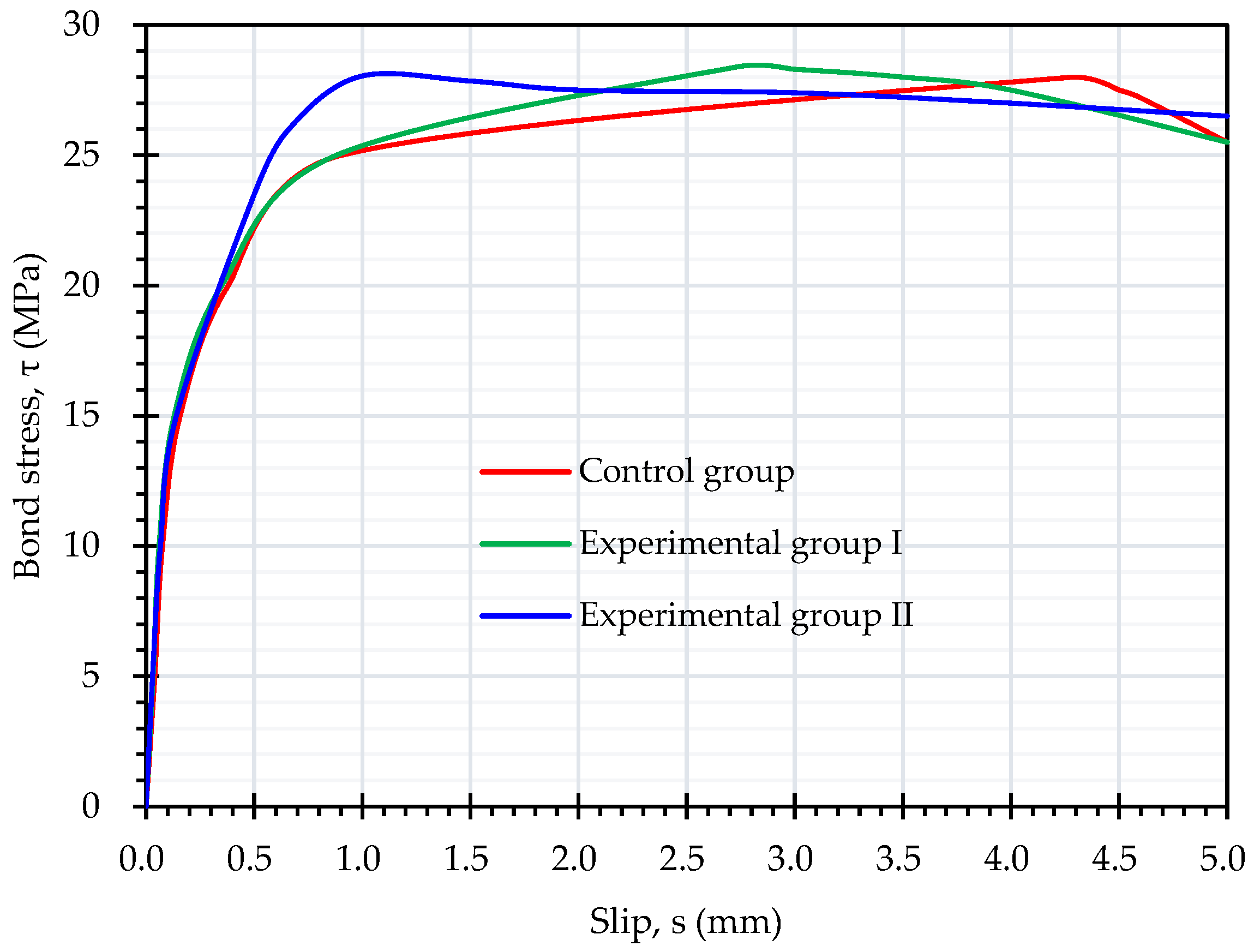

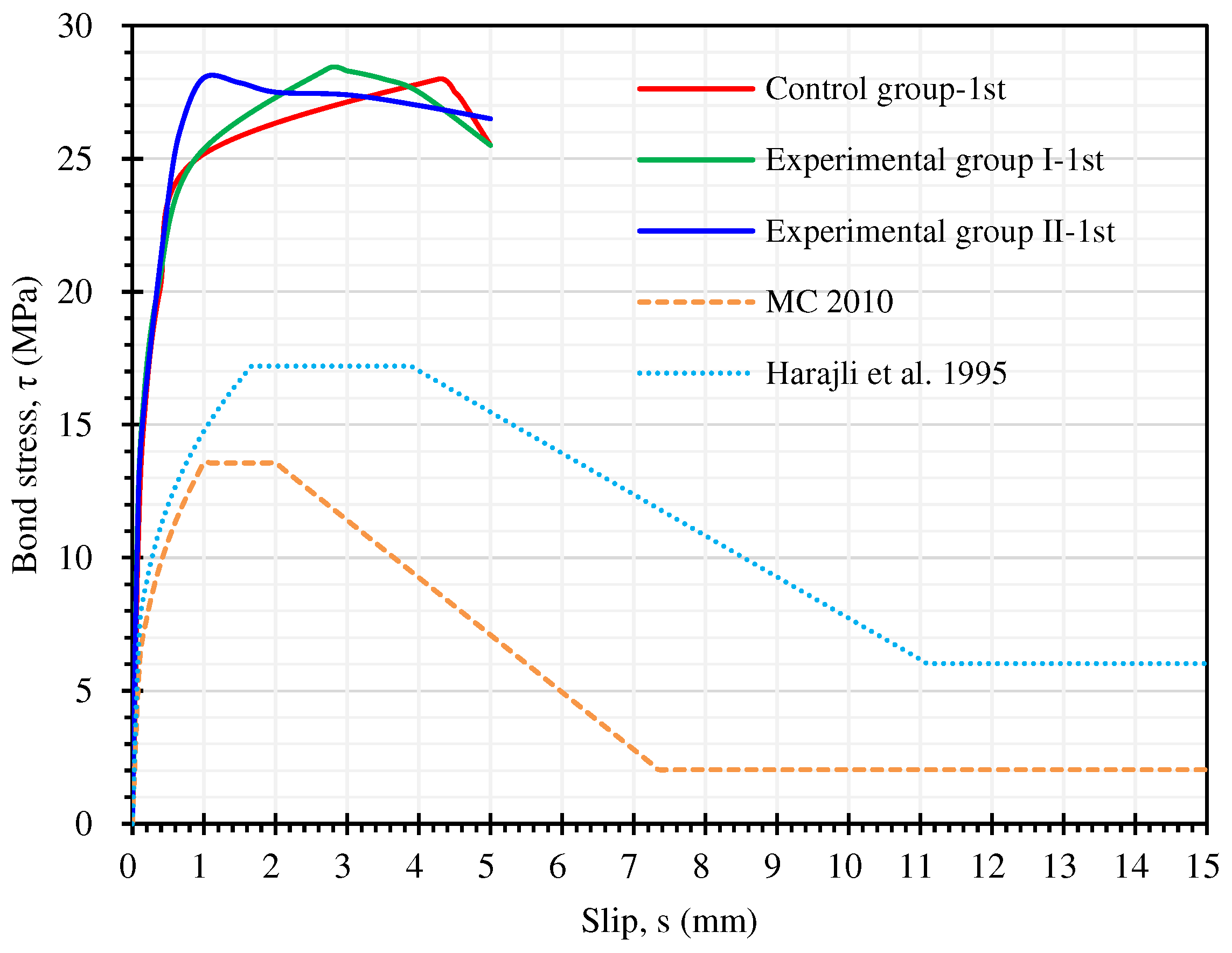

3.4. Local Bond Stress–Slip Relationship of Steel Bars in LWAC

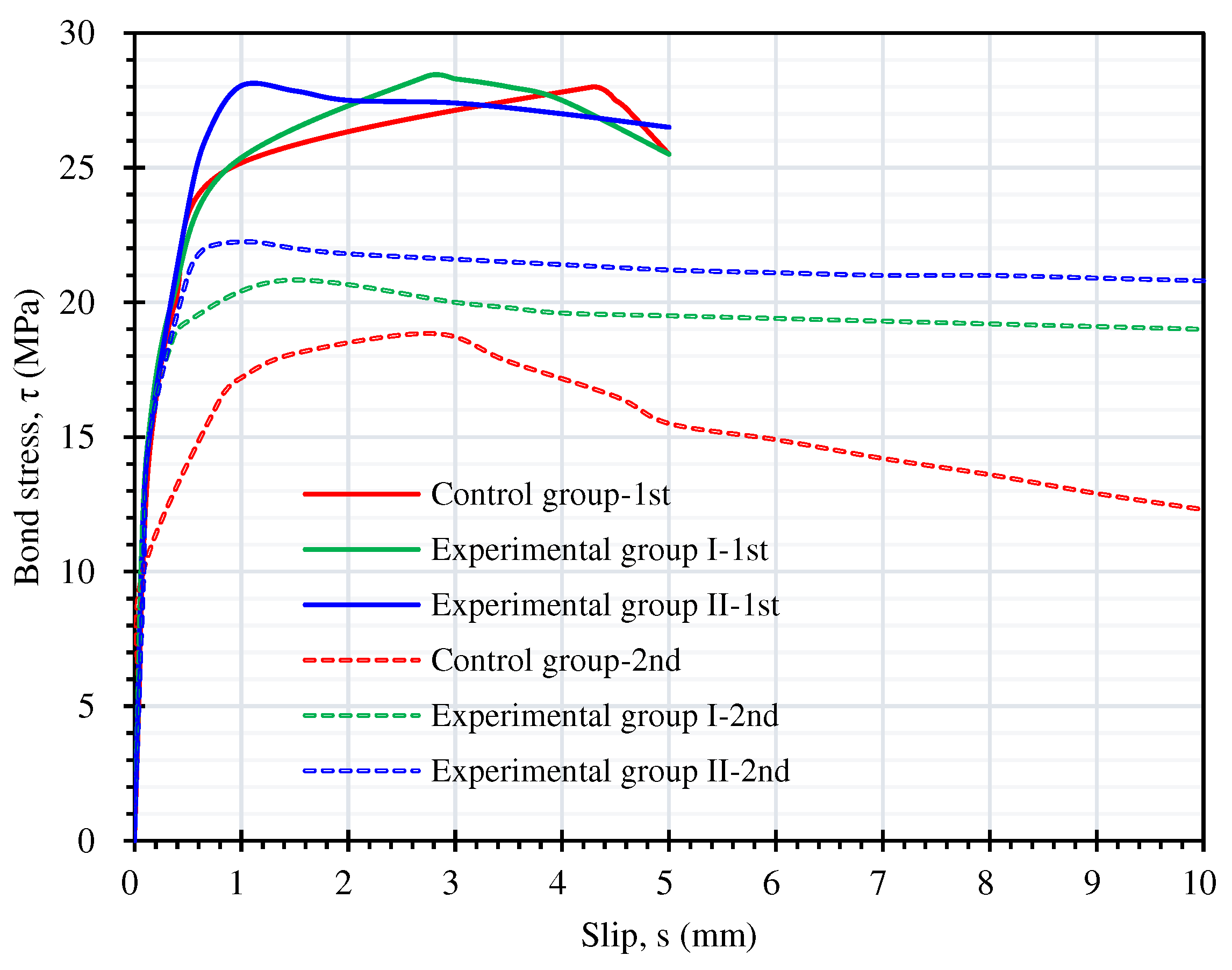

3.4.1. Bond Stress–Slip Relationship in the First Pull-Out Test of Steel Bars in LWAC

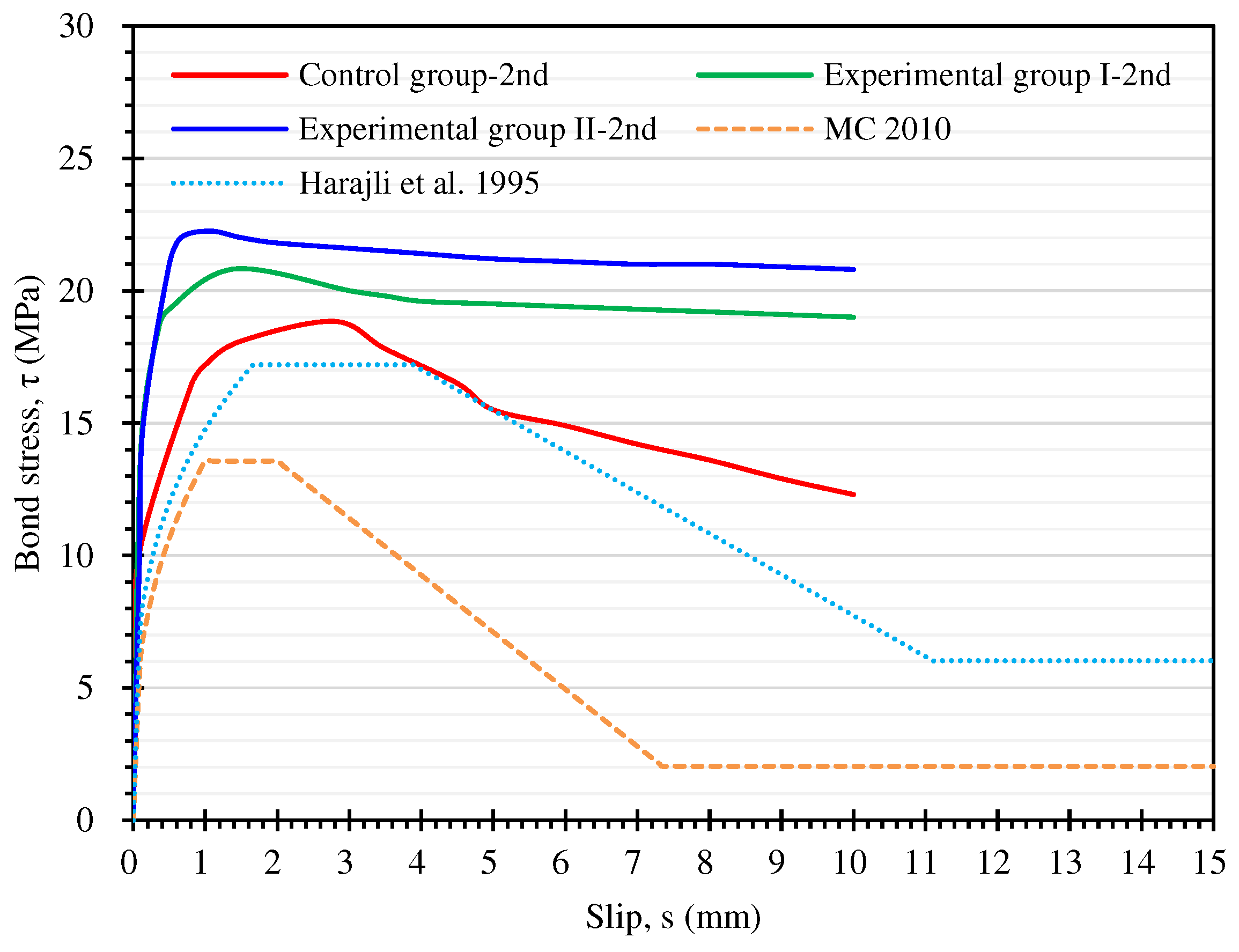

3.4.2. Bond Stress–Slip Relationship in the Secondary Pull-Out Test of Steel Bars in LWAC

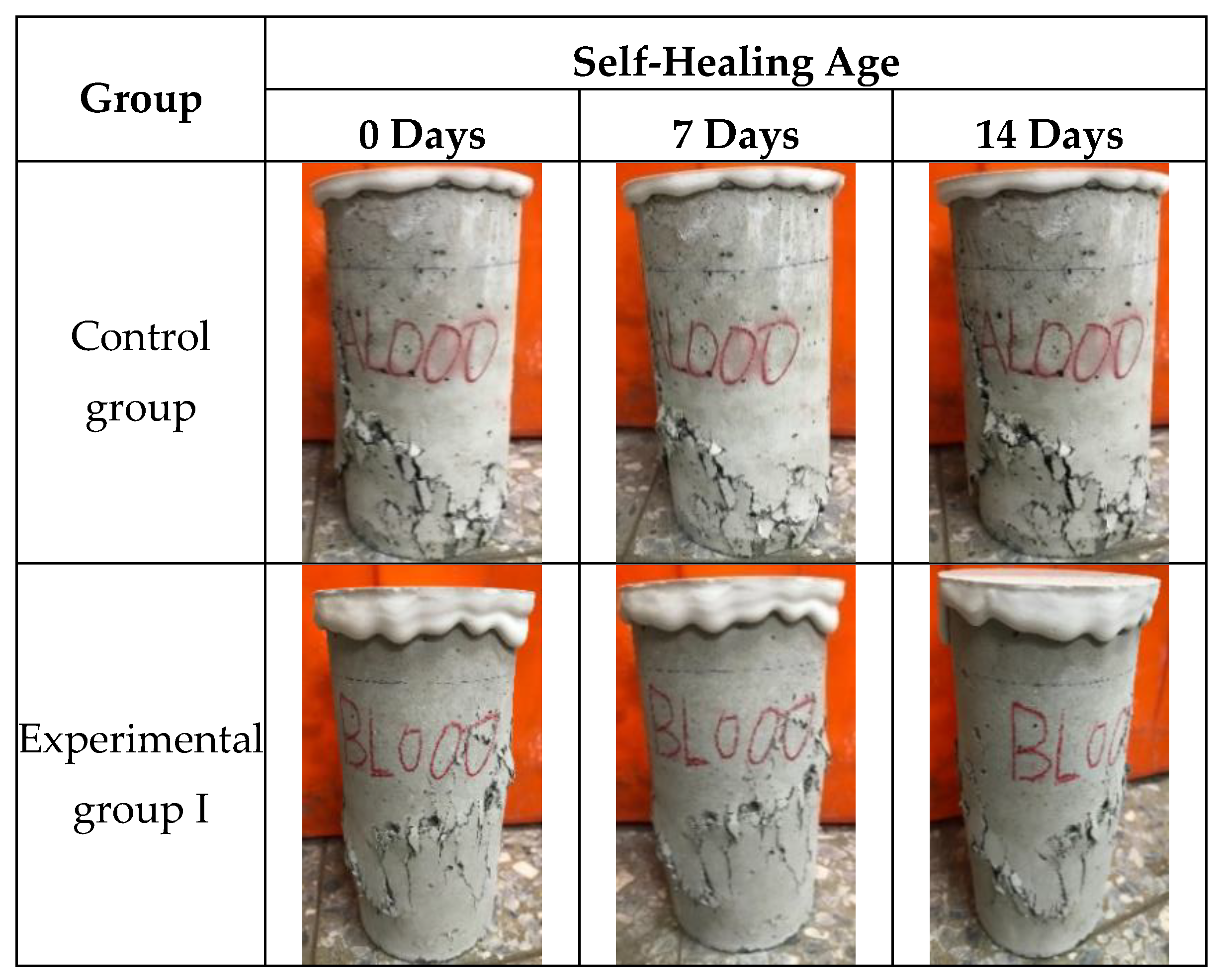

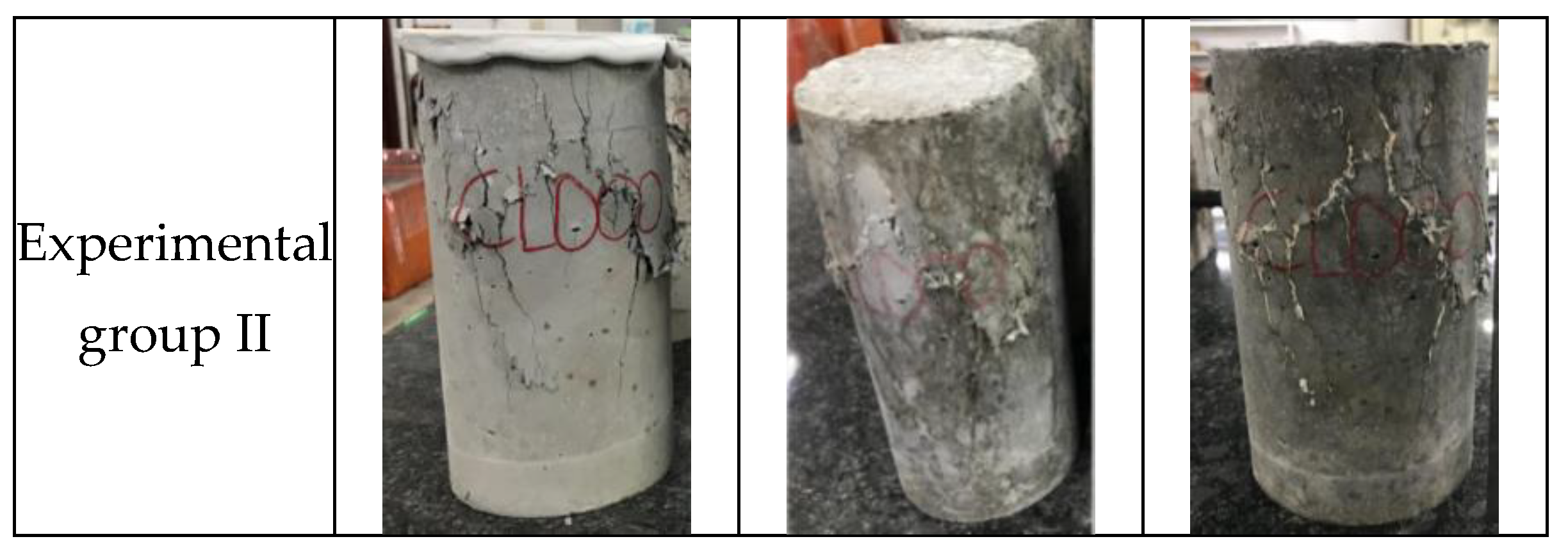

3.5. Result of the Concrete Crack Healing Observation

3.6. Results of FESEM Images, EDS Analysis, and XRD Analysis

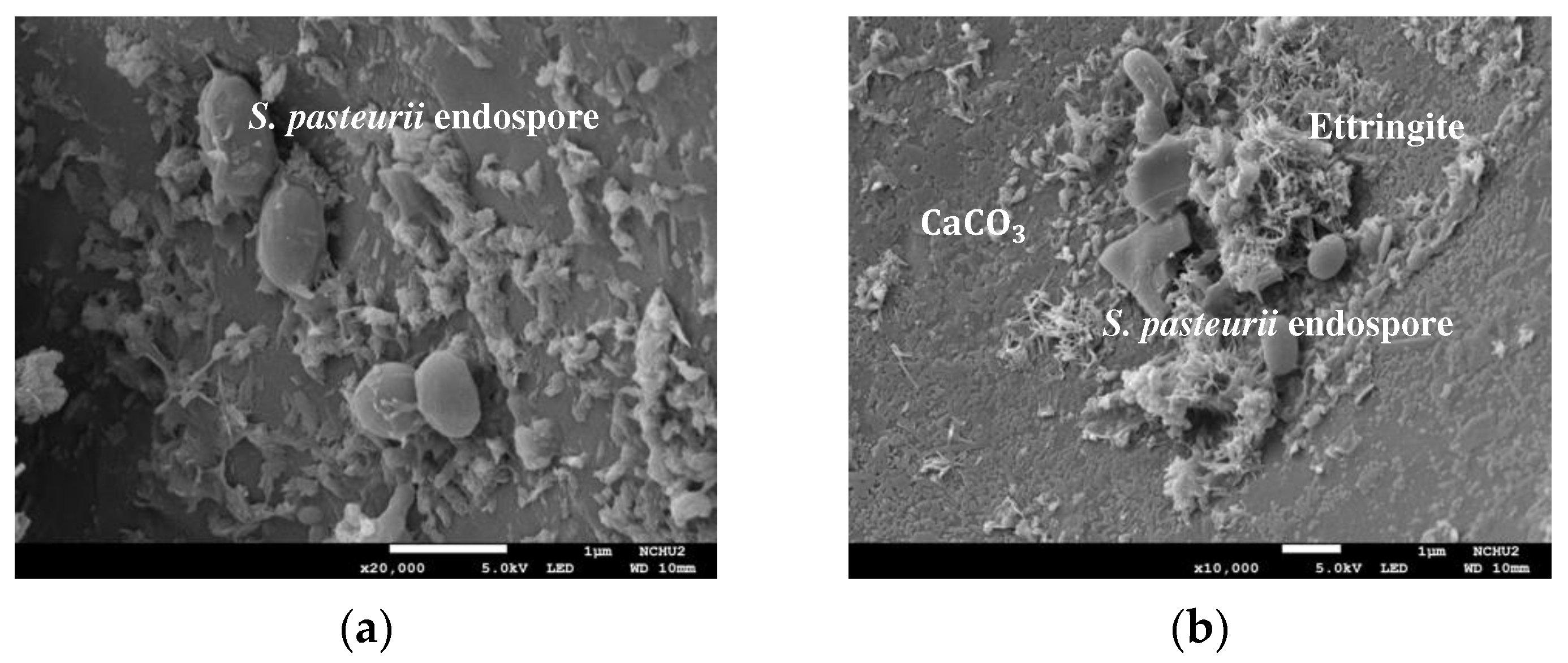

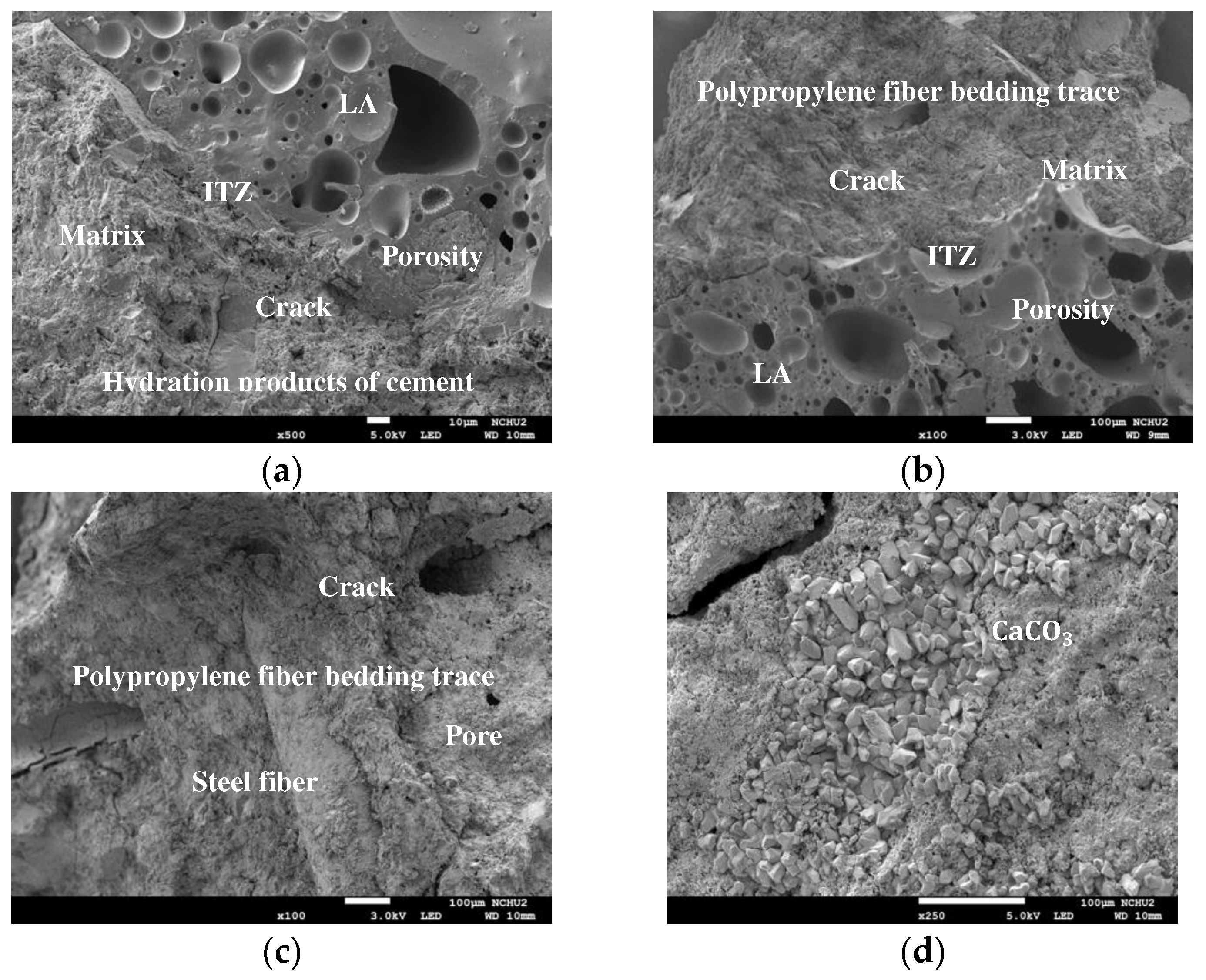

3.6.1. Results of FESEM Images

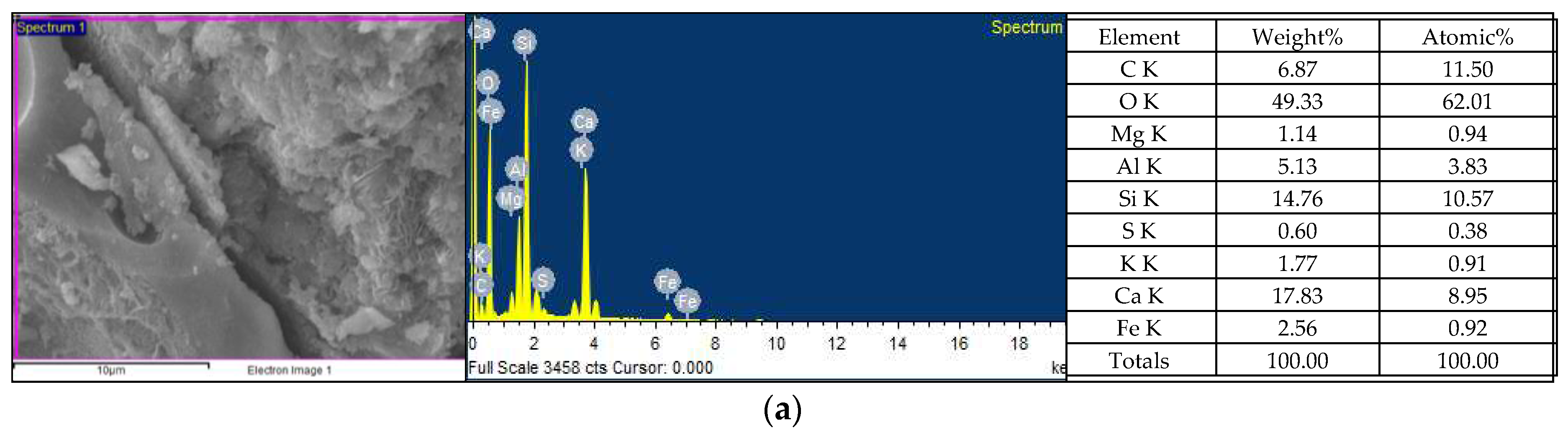

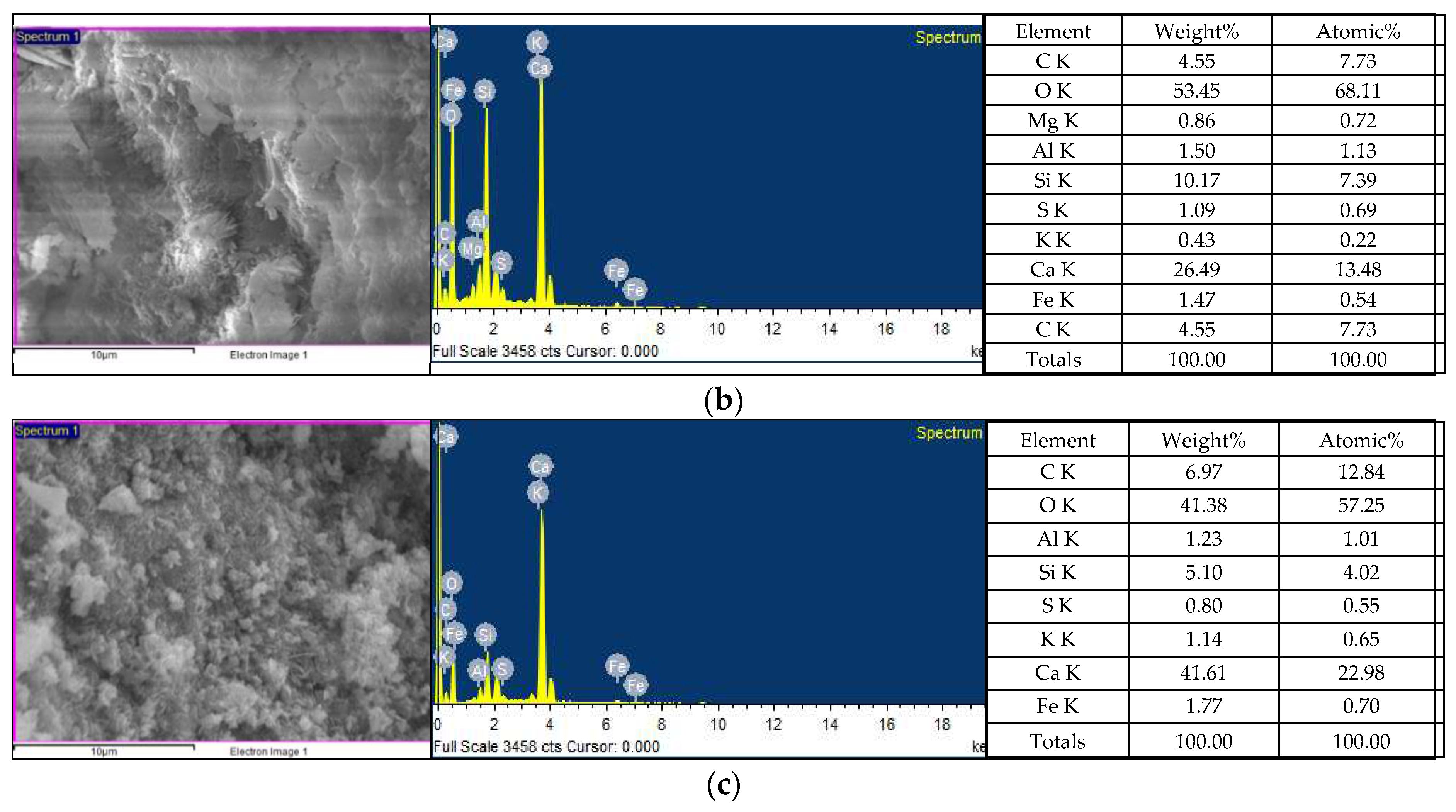

3.6.2. Results of EDS Analysis

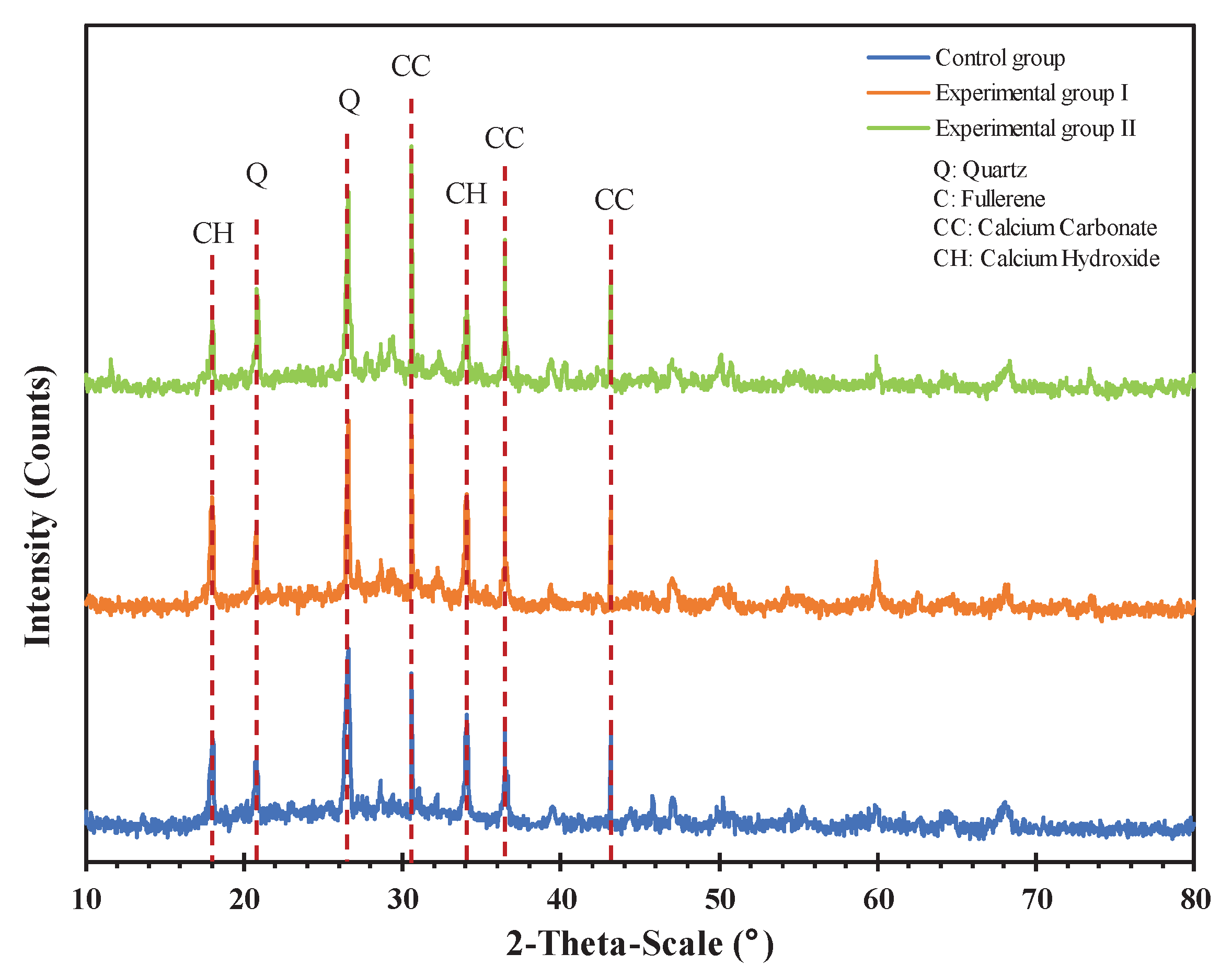

3.6.3. Results of XRD Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Somayaji, S. Civil engineering materials, 3rd ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2001.

- ACI Committee 213. ACI 213R-03; Guide for Structural Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2003.

- Chandra, S. and Berntsson, L. Lightweight Aggregate Concrete, Noyes Publications, New York, USA, 2002.

- Tang, C.-W. Local bond stress-slip behavior of reinforcing bars embedded in lightweight aggregate concrete. Computers & Concrete 2015, 16, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-W. Uniaxial bond stress-slip behavior of reinforcing bars embedded in lightweight aggregate concrete. Structural Engineering and Mechanics 2017, 62, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Suqa, W.; Morino, K. Mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced, high-strength, lightweight concrete. Cem Concr Compos. 1997, 19, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, M.; Shafigh, P.; Mahmud, H.B. Lightweight aggregate concrete fiber reinforcement—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Kusterle, W. Compressive stress–strain relationship of steel fibre reinforced concrete at early age. Cem Concr Res 2000, 30, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C. Large volume high performance applications of fibers in civil engineering. J Appl Polym Sci 2002, 83, 660–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metha, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties and Materials, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Zhao, M.; Chen, M.; Li, J.; Law, D. An experimental study on strength and toughness of steel fiber reinforced expanded-shale lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 183, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhu, E.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, C. Bond-slip behaviour of lightweight aggregate concrete based on virtual crack model with exponential softening characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 345, 128349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chi, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, P.; Zhang, A. Local bond performance of rebar embedded in steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber reinforced concrete under monotonic and cyclic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 103, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.M.; Shi, C.J.; Khayat, K.H. Multi-scale investigation of microstructure, fiber pullout behavior, and mechanical properties of ultra-high performance concrete with nano-CaCO3 particles. Cem Concr Compos 2018, 86, 255–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, G.; Cucchiara, C.; La Mendola, L.; Papia, M. Steel–concrete bond in lightweight fiber reinforced concrete under monotonic and cyclic actions. Eng. Struct. 2005, 27, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI Committee. 408. Bond and development of straight reinforcing bars in tension (ACI 408R–03). Farmington Hills, MI: American Concrete Institute; 2003.

- ACI Committee 318-19, Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary, American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills (2019).

- Lutz, L.A.; Gergely, P. Mechanics of Bond and Slip of Deformed Reinforcement. ACI J. 1967, 64, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond stress-slip relationship of oil palm shell lightweight concrete. Eng Struct 2016, 127, 319–30. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, K.M.A. Bond characteristics of plain and deformed bars in lightweight pumice concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1491–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, K.H.; Alengaram, U.J.; Visintin, P.; Goh, S.H.; Jumaat, M.Z. Influence of lightweight aggregate on the bond properties of concrete with various strength grades. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 84, 377–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, T.; Luo, X.; Feng, W. Bond-slip behavior between corroded rebar and lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. Bond-slip relationship of rebar in lightweight aggregate concrete. Structures 2022, 45, 2198–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEB-FIP. Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures 2010; Comité Euro international du Béton/Federation Internationale de la Precontrainte: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shima, H.; Chou, L.L.; Okamura, H. Micro and macro models for bond in reinforced concrete. J. Fac. Eng. 1987, 39, 133–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kankam, C.K. Relationship of bond stress, steel stress, and slip in reinforced concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1997, 123, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eligehausen, R.; Popov, E.P.; Bertero, V.V. Local bond stress-slip relationships of deformed bars under generalized excitations. 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Filippou, F.C.; Popov, E.P.; Bertero, V.V. Modeling of R/C joints under cyclic excitations. J. Struct. Eng. 1983, 109, 2666–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.N. Internal measurement of bond stress slip relationship in reinforced concrete. ACI J. 1979, 76, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Pauletta, M.; Rovere, N.; Randl, N.; Russo, G. Bond-Slip Behavior between Stainless Steel Rebars and Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CEB (1992), CEB-FIP Model. Code 90, Thomas Telford, London, UK, 1992.

- Harajli, M.H.; Hout, M.; Jalkh, W. Local bond stress-slip behaviour of reinforcing bars embedded in plain and fibre concrete. ACI Mater. J. 1995, 92, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harajli, M.H.; Hamad, B.; Karam, K. Bond-slip Response of Reinforcing Bars Embedded in Plain and Fiber Concrete. J. Mater. Civil Eng. 2002, 14, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harajli, M.H. Numerical bond analysis using experimentally derived local bond laws: A powerful method for evaluating the bond strength of steel bars. J. Struct. Eng. 2007, 133, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, H.; Wiktor, V.; Gruyaert, E.; Serna, P. Experimental investigation on the bond behaviour of steel reinforcement in self-healing concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 383, 131378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Beltran, M.G.; Jonkers, H.M.; Schlangen, E. Characterization of sustainable bio-based mortar for concrete repair. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 67, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dry, C.M. Three designs for the internal release of sealants, adhesives, and waterproofing chemicals into concrete to reduce permeability. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1969–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheanyichukwu, C.G.; Umar, S.A.; Ekwueme, P.C. A Review on Self-Healing Concrete Using Bacteria. Sustain. Struct. Mater. Int. J. 2018, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Tang, C.S.; Jiang, N.J.; Pan, X.H.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.J.; Shi, B. Microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) technology: a review on the fundamentals and engineering applications. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaszek-Tomal, E. Bacterial Concrete as a Sustainable Building Material? Sustainability 2020, 12, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Zuo, J.; Liu, X. Self-healing of concrete cracks by ceramsite-loaded microorganisms. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 5153041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zong, X.; Cui, B.; Guo, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, J. Application of Carrier Materials in Self-Healing Cement-Based Materials Based on Microbial-Induced Mineralization. Crystals 2022, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkers, H.M.; Thijssen, A.; Muyzer, G.; Copuroglu, O.; Schlangen, E. Application of bacteria as self-healing agent for the development of sustainable concrete. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Chang, H.-L.; Tang, C.-W.; Yang, T.-Y. Application of biomineralization technology to self-healing of fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete after high temperatures. Materials 2022, 15, 7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, R.R.; Luo, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, N.; Jin, C. Screening of fungi for potential application of self-healing concrete. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Jia, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Optimization of Sporulation and Germination Conditions of Functional Bacteria for Concrete Crack-Healing and Evaluation of their Repair Capacity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 10938–10948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeksting, B.J.; Hoffmann, T.D.; Tan, L.; Paine, K.; Gebhard, S. In-depth profiling of calcite precipitation by environmental bacteria reveals fundamental mechanistic differences with relevance to application. Appl Environ. Microbiol 2020, 86, e02739-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, H.; Minne, P.; Serna, P.; Gruyaert, E. Understanding the Impacts of Healing Agents on the Properties of Fresh and Hardened Self-Healing Concrete: A Review. Processes 2021, 9, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Peng, C.-F.; Tang, C.-W.; Chen, Y.-T. Self-Healing Concrete by Biological Substrate. Materials 2019, 12, 4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C494/C494M-17; Standard and Specification for Chemical Admixtures for Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ASTM A820/A820M-06; Standard Specification for Steel Fibers for Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C143/C143M-15a; Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C138/C138M-17a; Standard Test Method for Density (Unit Weight), Yield, and Air Content (Gravimetric) of Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C39/C39M-18; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C469/C469M-14; Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C234; Standard Test Method for Comparing Concretes on the Basis of the Bond Developed with Reinforcing Steel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1991.

- Meng, L.; Zhang, C.; Wei, J.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Ding, Y. Mechanical properties and microstructure of ultra-high strength concrete with lightweight aggregate. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, T.W.; Holm, T.A. Elastic compatibility and the behavior of concrete. ACI J. 1986, 83, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.X. Recent advances in high strength lightweight concrete: From development strategies to practical applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevinly, C.; Du, P.; Tan, K.H. Local bond-slip behaviour of reinforcing bars in fibre reinforced lightweight aggregate concrete at ambient and elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 377, 131010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, K.H.; Visintin, P.; Alengaram, U.J.; Jumaat, M.Z. Bond stress-slip relationship of oil palm shell lightweight concrete. Eng Struct 2016, 127, 319–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, J.; Jones, K. An evaluation of the bond-splitting action of ribbed bars. ACI Mater J 1996, 93, 10–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishami, H.H.; Mitchell, D. Influence of splitting cracks on tension stiffening. ACI Struct J 1996, 93, 703–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadapure, S.A.; Deshannavar, U.B. Bio-smart material in self-healing of concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 49, 1498–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.J.; Gerlach, R.; Lauchnor, E.; Mitchell, A.C.; Cunningham, A.B.; Spangler, L. Engineered applications of ureolytic biomineralization: a review. Biofouling 2013, 29, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Park, S.J.; Han, J.I.; Lee, H.K. Microbially mediated calcium carbonate precipitation on normal and lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, P.; Dabbagh, H.; Ashengroph, M. Effects of microbial strains on the mechanical and durability properties of lightweight concrete reinforced with polypropylene fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 322, 126519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Model Code 2010 (2010) | Harajli et al. (1995) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confined NWC | Confined LWAC | Concrete | |

| 1.0 mm | 1.0 mm | 0.15 Distance bet. ribs | |

| 3.0 mm | 2.0 mm | 0.35 Distance bet. ribs | |

| Clear rib spacing | Clear rib spacing | Distance bet. ribs | |

| α | 0.4 | 0.35 | 0.3 |

| 0.60.82 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.15 | ||

| Test Items | Test Parameters | |

| Curing method | Self-healing age (day) | |

| Compressive strength test | Incubator, cyclical treatment | 0 |

| Pull-out test | Incubator, cyclical treatment | 0 |

| Secondary compressive strength test | Incubator, cyclical treatment | 28 |

| Secondary pull-out test | Incubator, cyclical treatment | 28 |

| Observation of crack repair | Incubator, cyclical treatment | 0, 7, 14 |

| FESEM, EDS, and XRD analysis | Incubator, cyclical treatment | 0, 28 |

| Chemical Composition (%) | Cement |

|---|---|

| Silicon dioxide, SiO2 | 20.48 |

| Aluminum oxide, Al2O3 | 5.93 |

| Iron oxide, Fe2O3 | 3.39 |

| Calcium oxide, CaO | 65.50 |

| Magnesium oxide, MgO | 2.06 |

| Sulfur trioxide, SO3 | 2.39 |

| Free calcium oxide, f-CaO | 0.78 |

| Loss on ignition, LOI | 0.76 |

| Tricalcium silicate, C3S | 59.50 |

| Dicalcium silicate, C2S | 13.83 |

| Tricalcium aluminate, C3A | 9.98 |

| Items | State of LWAs | |

|---|---|---|

| With Bacterial Spores | Without Bacterial Spores | |

| Dry unit weight (kg/m3) | 622.1 | 618.8 |

| Porosity (%) | 47.53 | 45.22 |

| Bulk specific gravity | 1.188 | 1.172 |

| Apparent gravity | 1.246 | 1.233 |

| 1-hour water absorption rate (%) | 8.6 | 11.4 |

| 24-hour water absorption rate (%) | 10.3 | 13.3 |

| Crushing strength (MPa) | 4.3 | 4.4 |

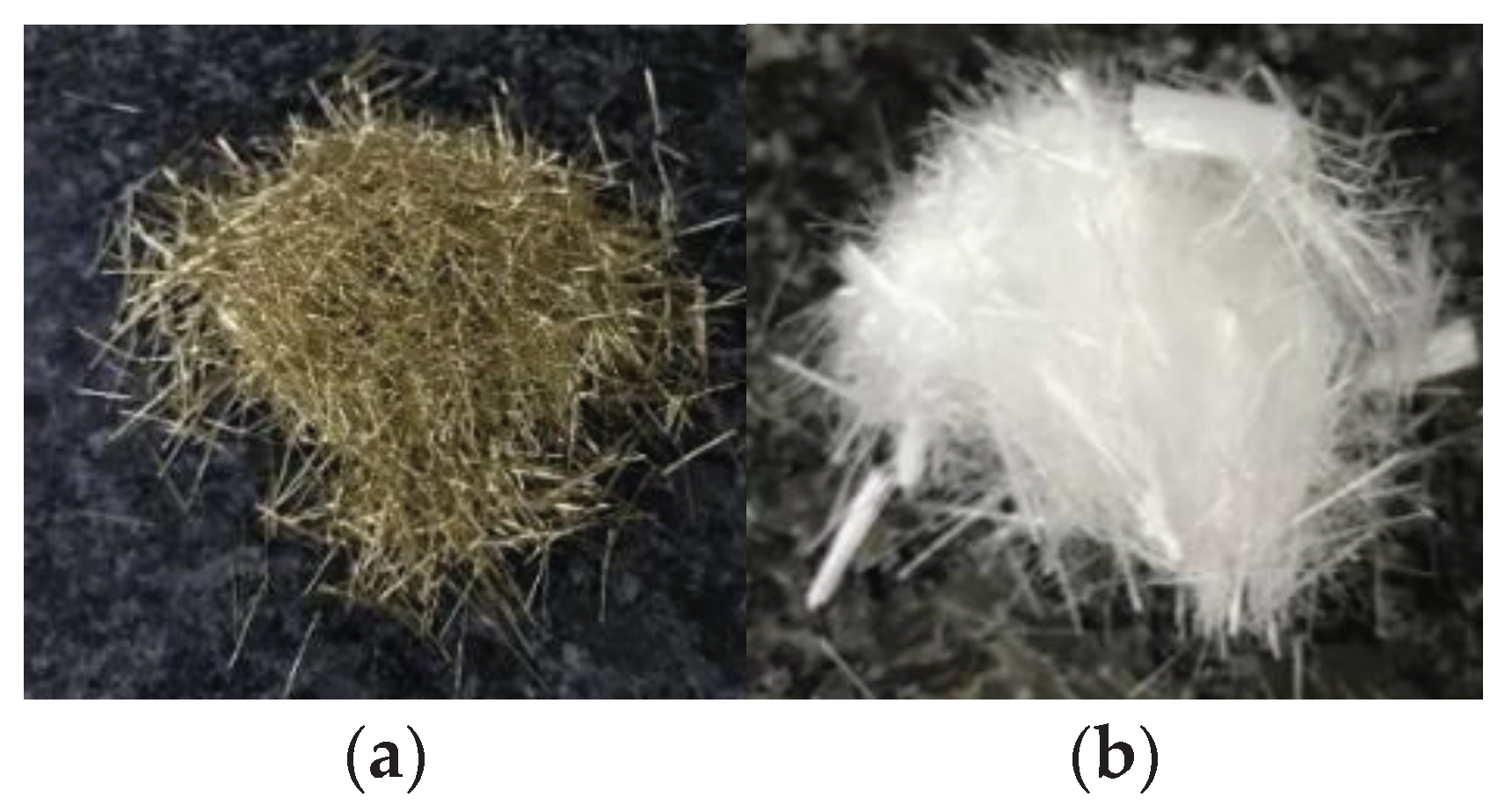

| Fiber Type | Length (mm) |

Diameter (mm) |

Density (g/cm3) |

Elastic Modulus (GPa) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Melting Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel fibers | 13 | 0.2 | 7.8 | 200 | 2000 | - |

| Polypropylene fibers | 12 | 0.05 | 0.9 | - | 300 | 165 |

| Nominal Dia. (mm) |

Rib Distance (mm) |

Rib Width (mm) |

Rib Height (mm) |

Yield Strength (MPa) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.1 | 11.1 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 457 | 658 |

| Group | W/B | W (kg/m3) |

C (kg/m3) |

LWA (kg/m3) |

FA (kg/m3) |

SF (kg/m3) |

PP (kg/m3) |

SP (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | 0.45 | 220 | 489 | 345 | 734 | 58.5 | 1.17 | 0.978 |

| Experimental group | 0.45 | 220 | 489 | 345 | 734 | 58.5 | 1.17 | 0.978 |

| Item | Experiment Method |

|---|---|

| Slump | ASTM C143 [52] |

| Unit weight and air content | ASTM C138 [53] |

| Compressive strength | ASTM C39 [54] |

| Static modulus of elasticity | ASTM C469 [55] |

| Bond strength | ASTM C234 [56] |

| Test Item | Test Sequence |

|---|---|

| Compression test after 28 days of curing | Curing→loading |

| Secondary compression test after self-healing of compressive failure specimen | Curing→loading→self-healing→reloading |

| Pull-out test after 28 days of curing | Curing→loading |

| Secondary pull-out test after self-healing of pull-out failure specimen | Curing→loading→self-healing→reloading |

| Group | Slump (cm) | Unit Weight (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | 13 | 1849 |

| Experimental group | 13 | 1849 |

| Group | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | 44.59 | 18.75 |

| Experimental group I | 44.81 | 19.09 |

| Experimental group II | 45.88 | 19.26 |

| Group | Compressive Strength (MPa) |

Residual Compressive Strength after Self-Healing (MPa) | Relative Compressive Strength Ratio after Self-Healing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | 44.59 | 13.83 | 0.31 |

| Experimental group I | 44.81 | 14.37 | 0.32 |

| Experimental group II | 45.88 | 15.61 | 0.34 |

| Group | Bond Strength (MPa) | Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | 27.99 | Pull-out |

| Experimental group I | 28.38 | Pull-out |

| Experimental group II | 28.02 | Pull-out |

| Group | Bond Strength (MPa) | Residual Bond Strength (MPa) | Relative Bond Strength Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | 27.99 | 18.84 | 0.67 |

| Experimental group I | 28.38 | 20.82 | 0.73 |

| Experimental group II | 28.02 | 22.25 | 0.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).