Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup

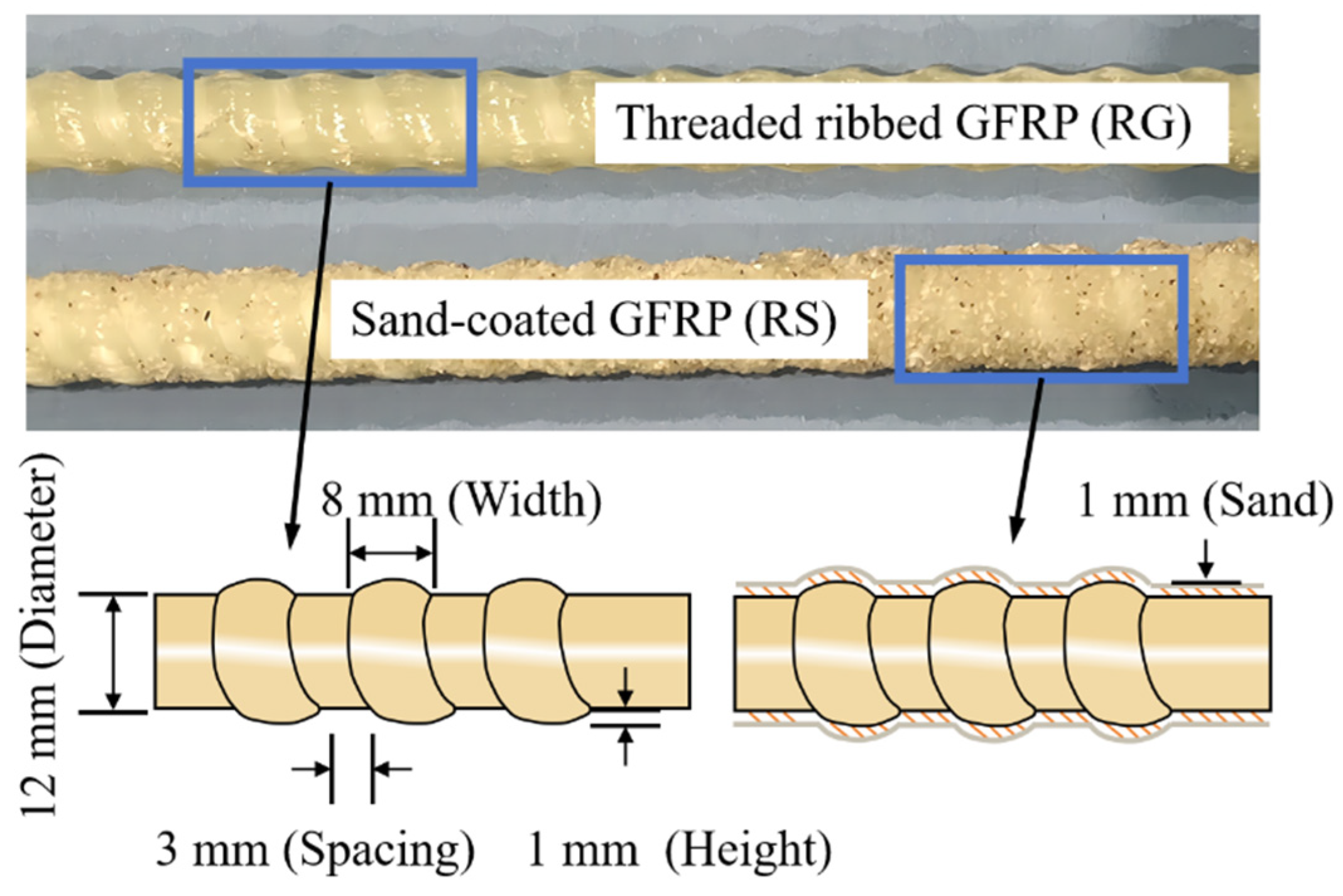

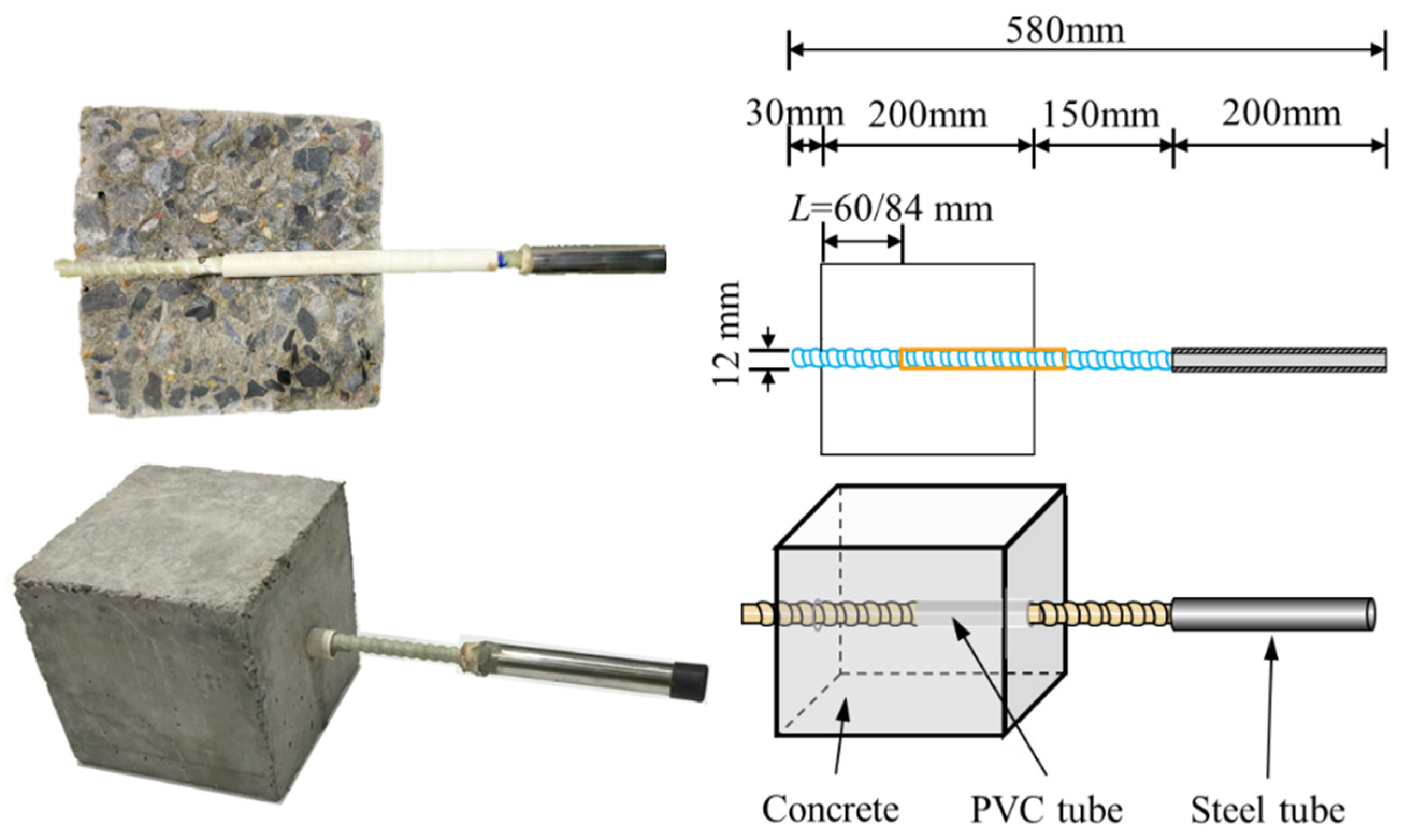

2.1. Design of Pull-Out Specimen

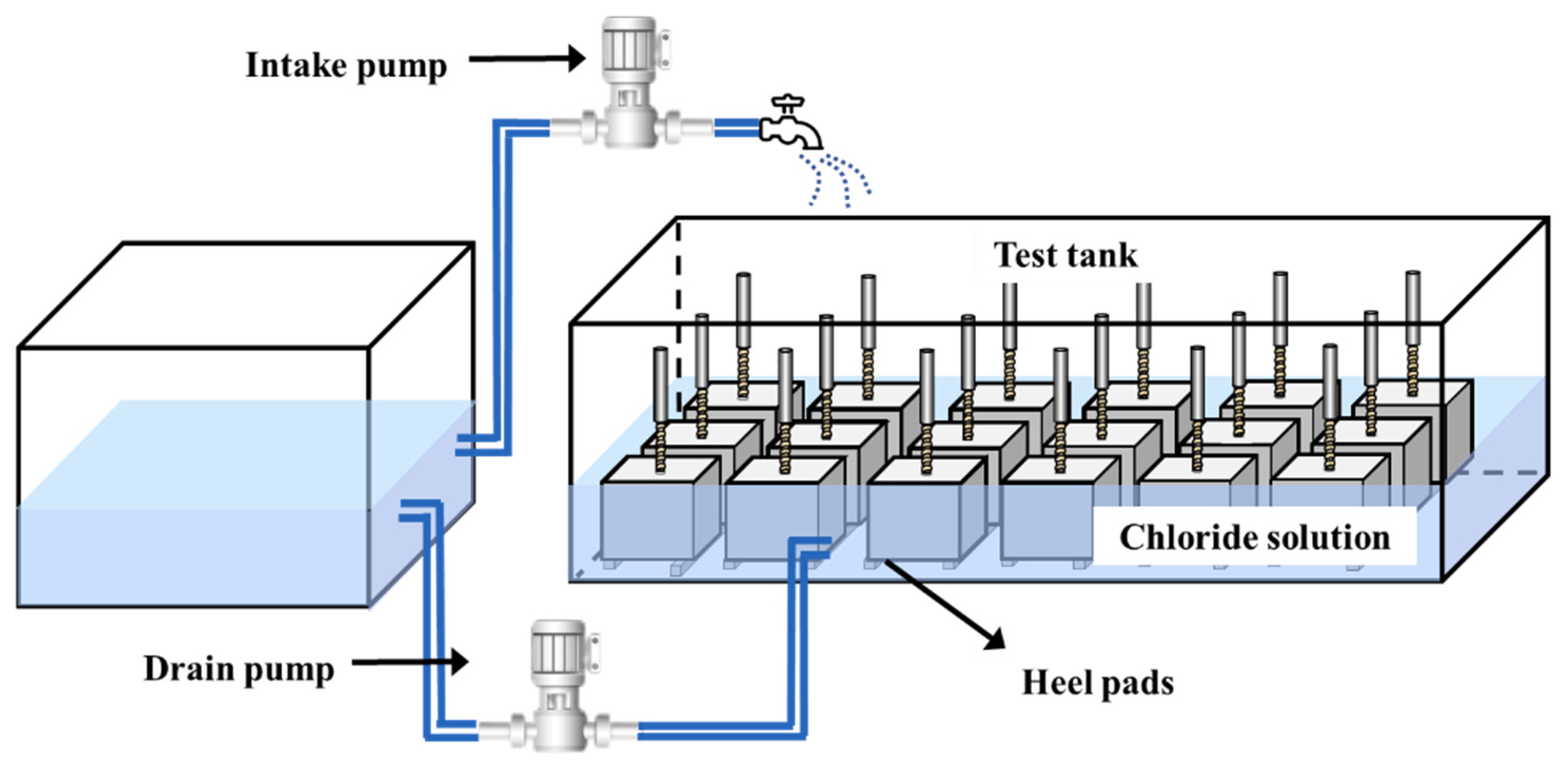

2.2. Chloride Dry-Wet Exposure Program

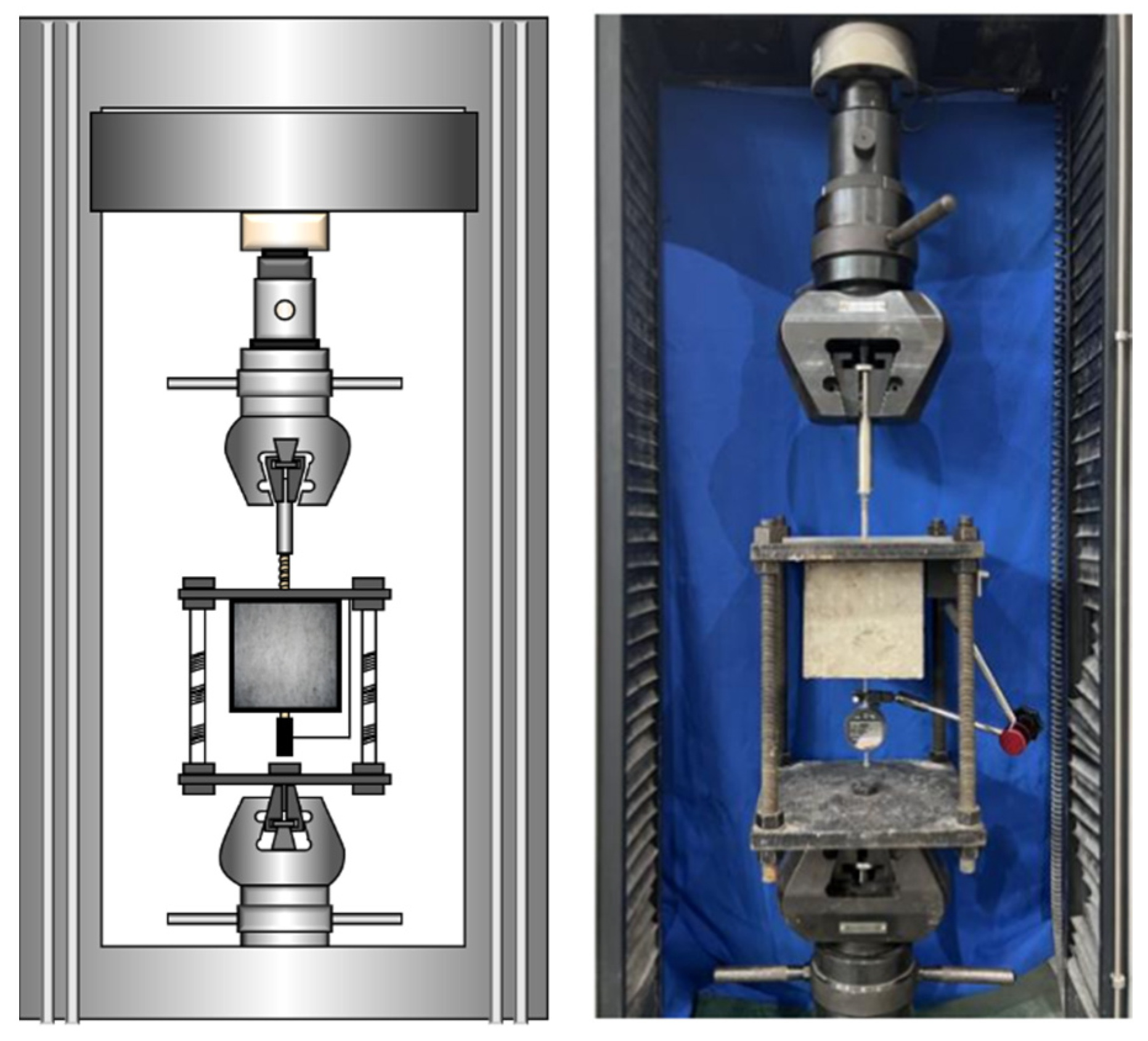

2.3. Pull-Out Loading Scheme

3. Experimental Results and Discussions

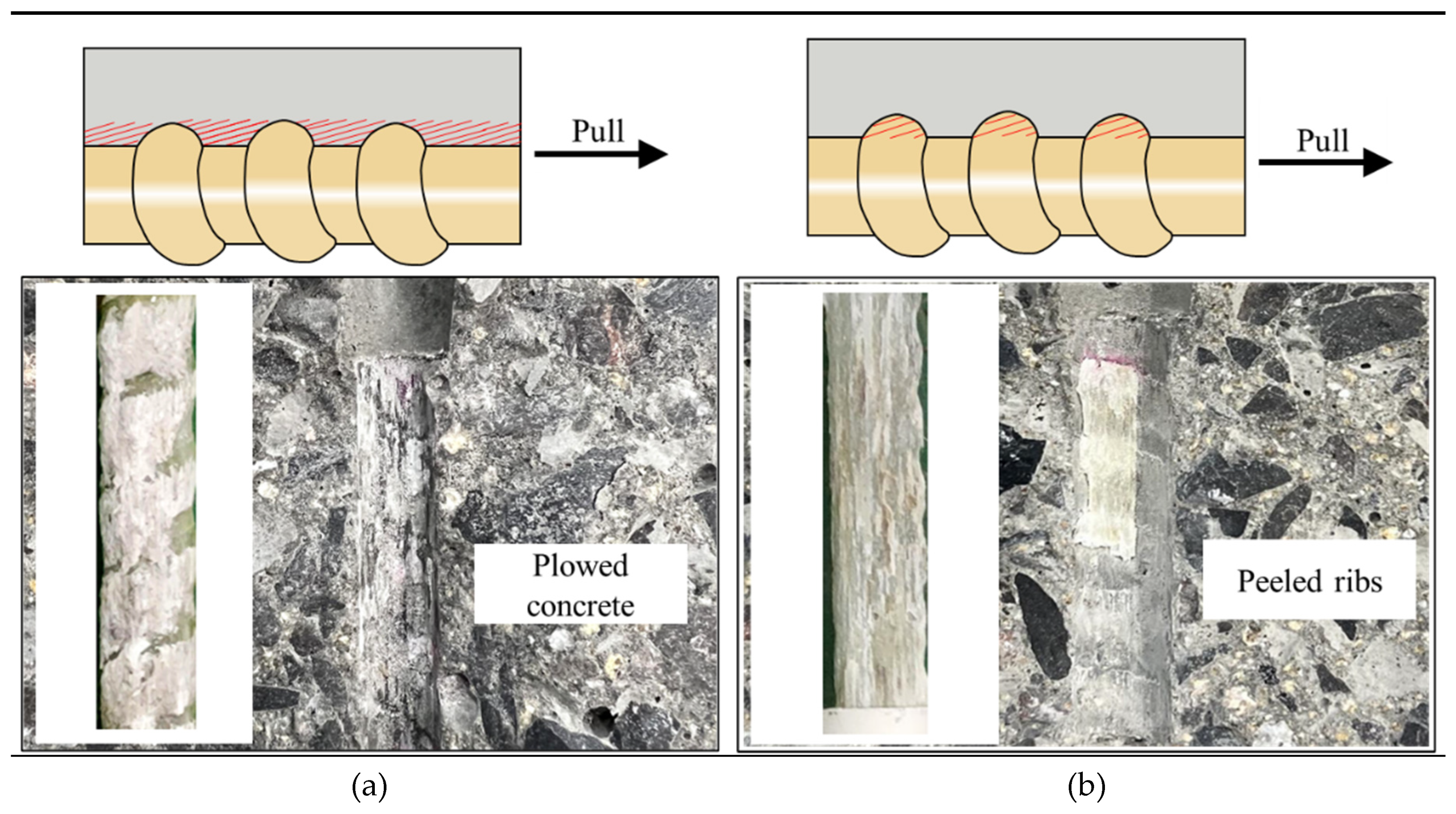

3.1. Failure Patterns and Test Results

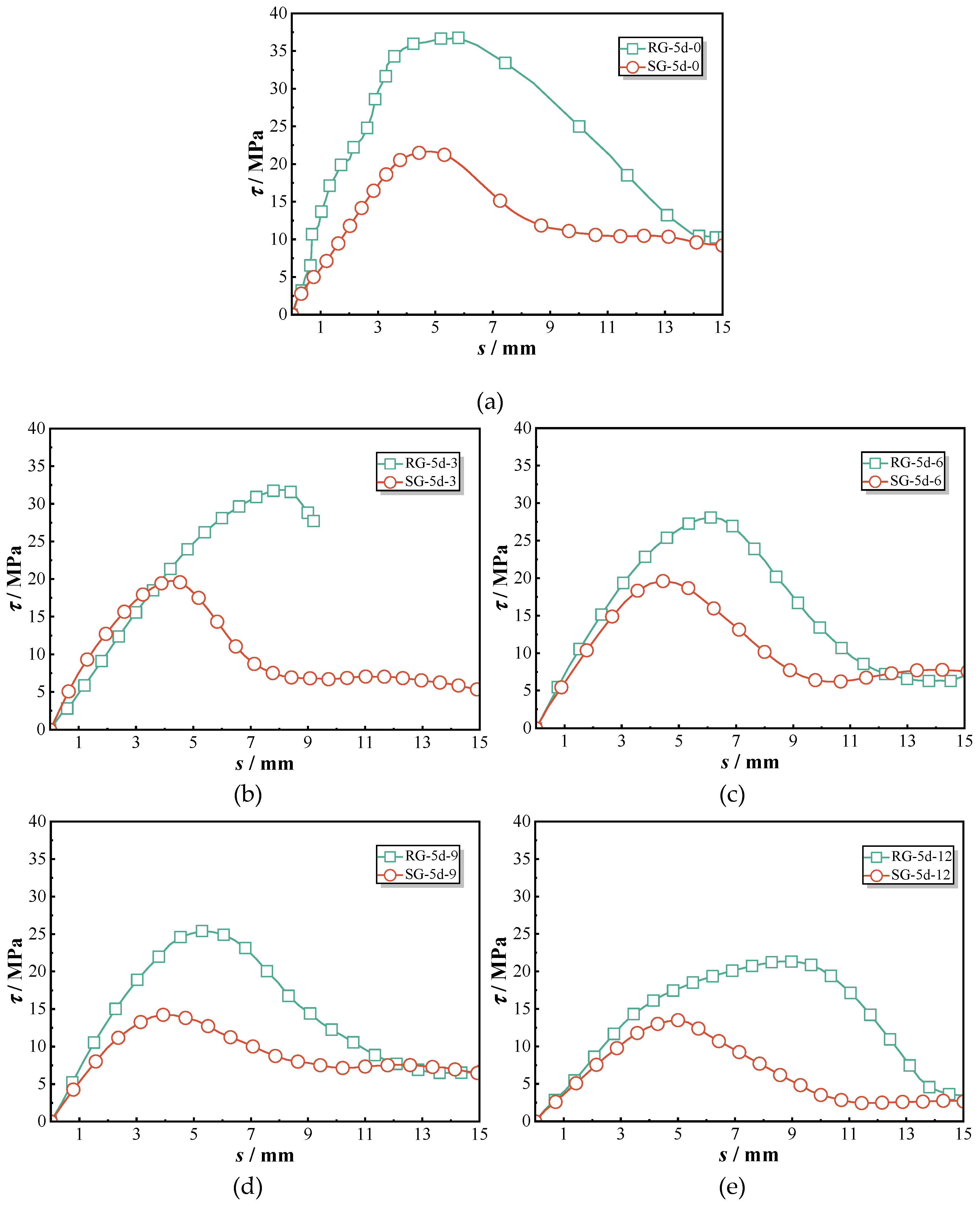

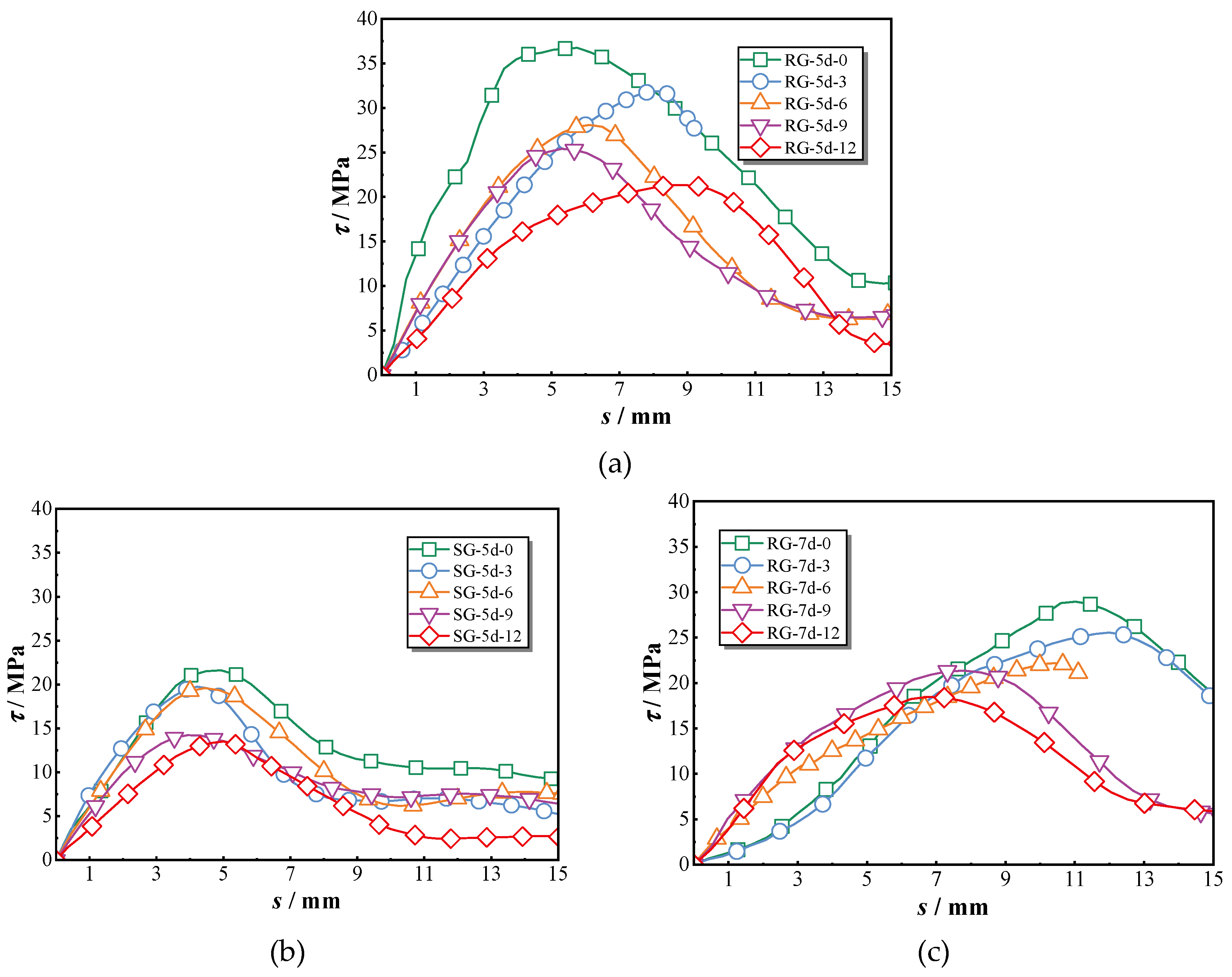

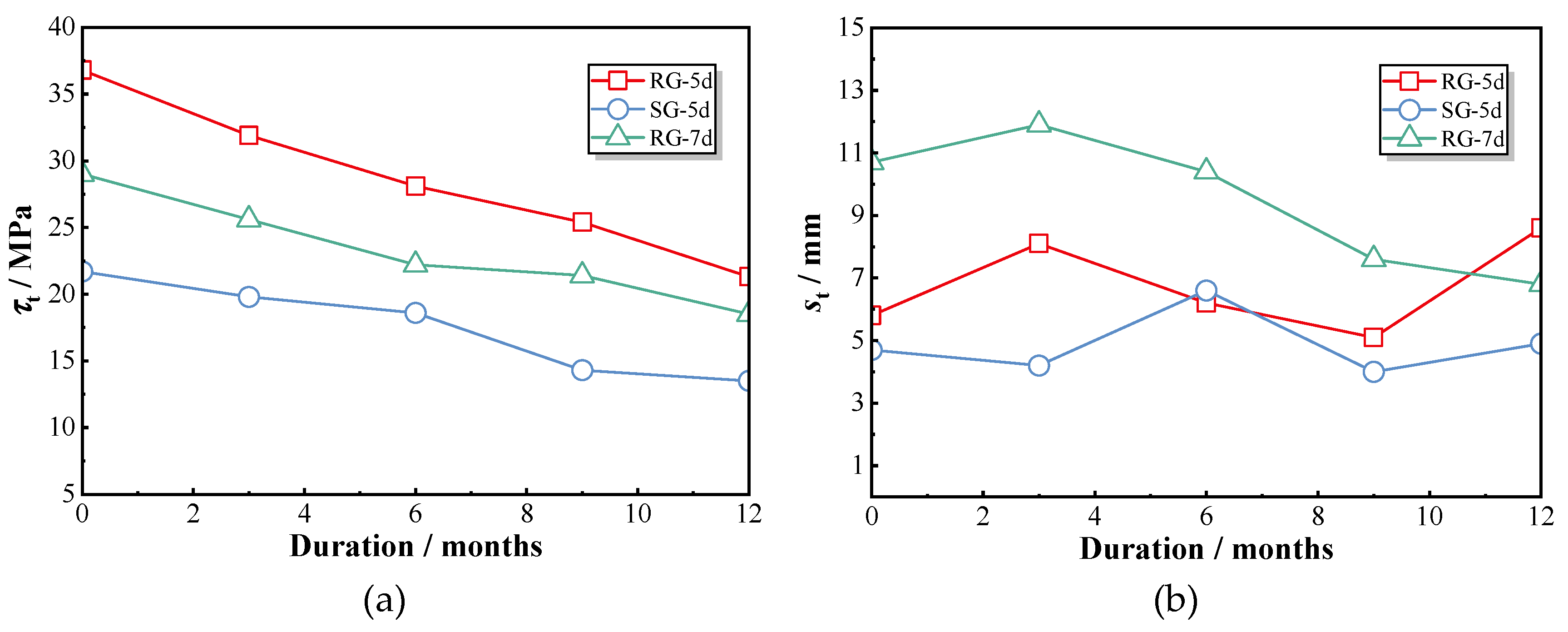

3.2. Effects of Surface Textures

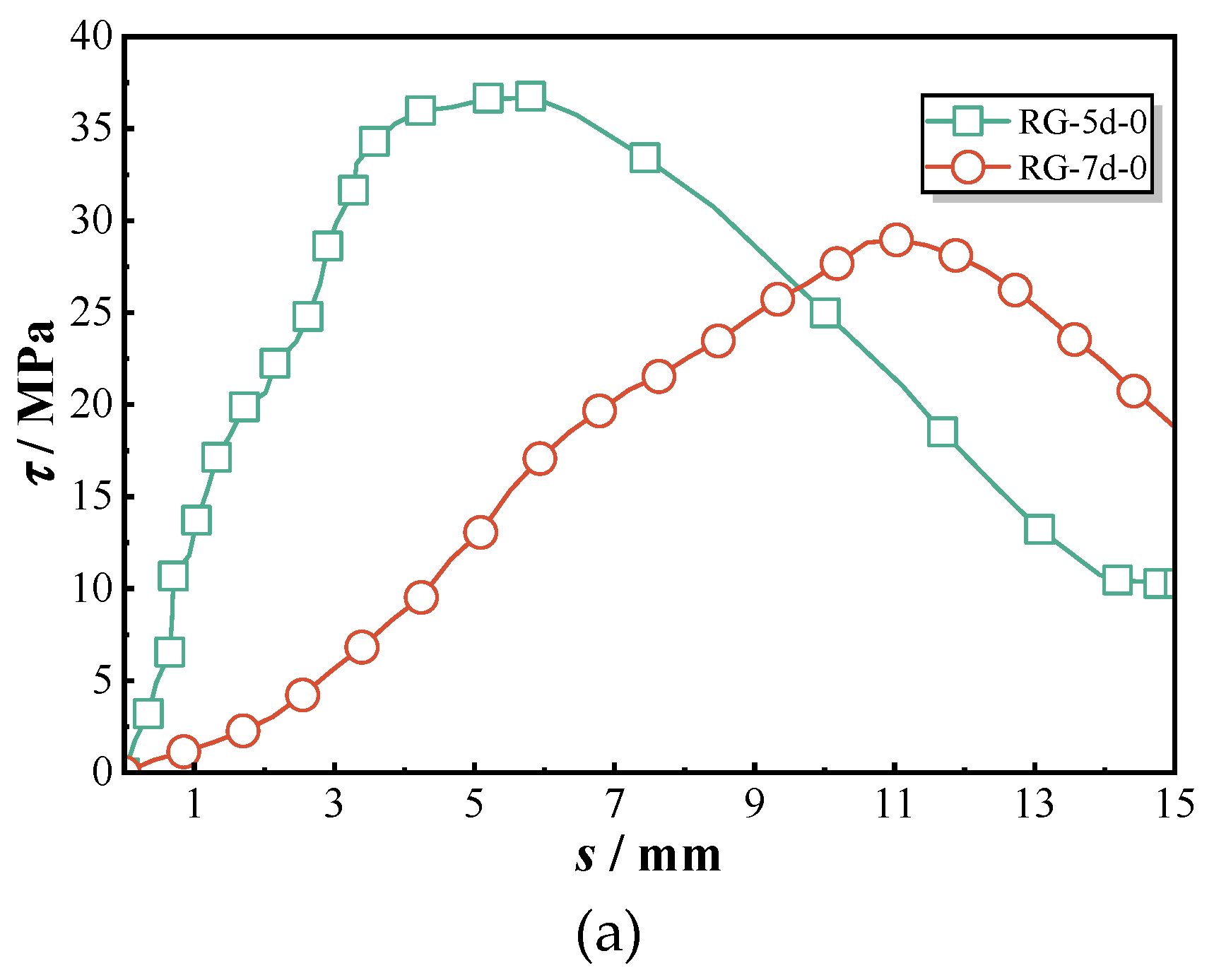

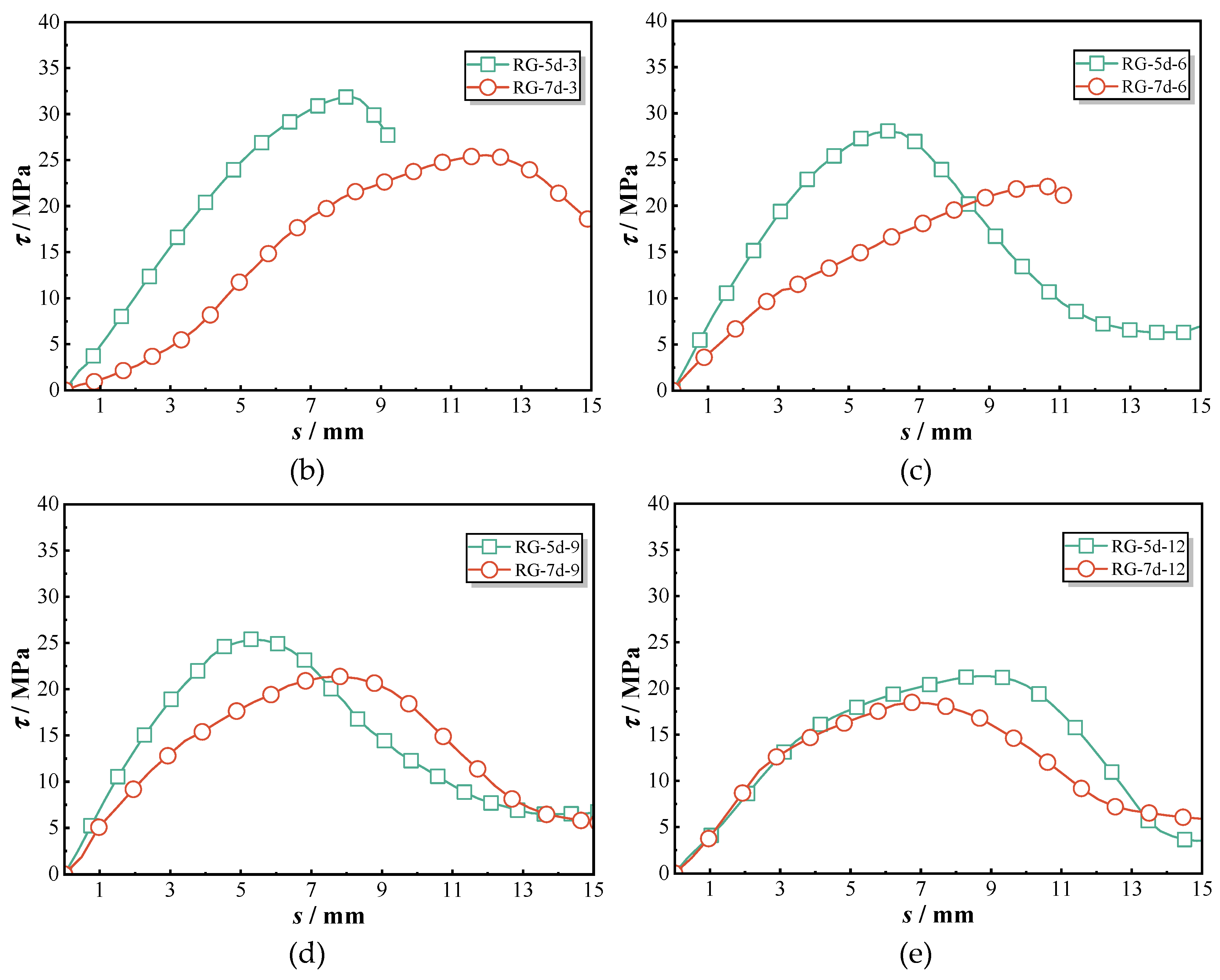

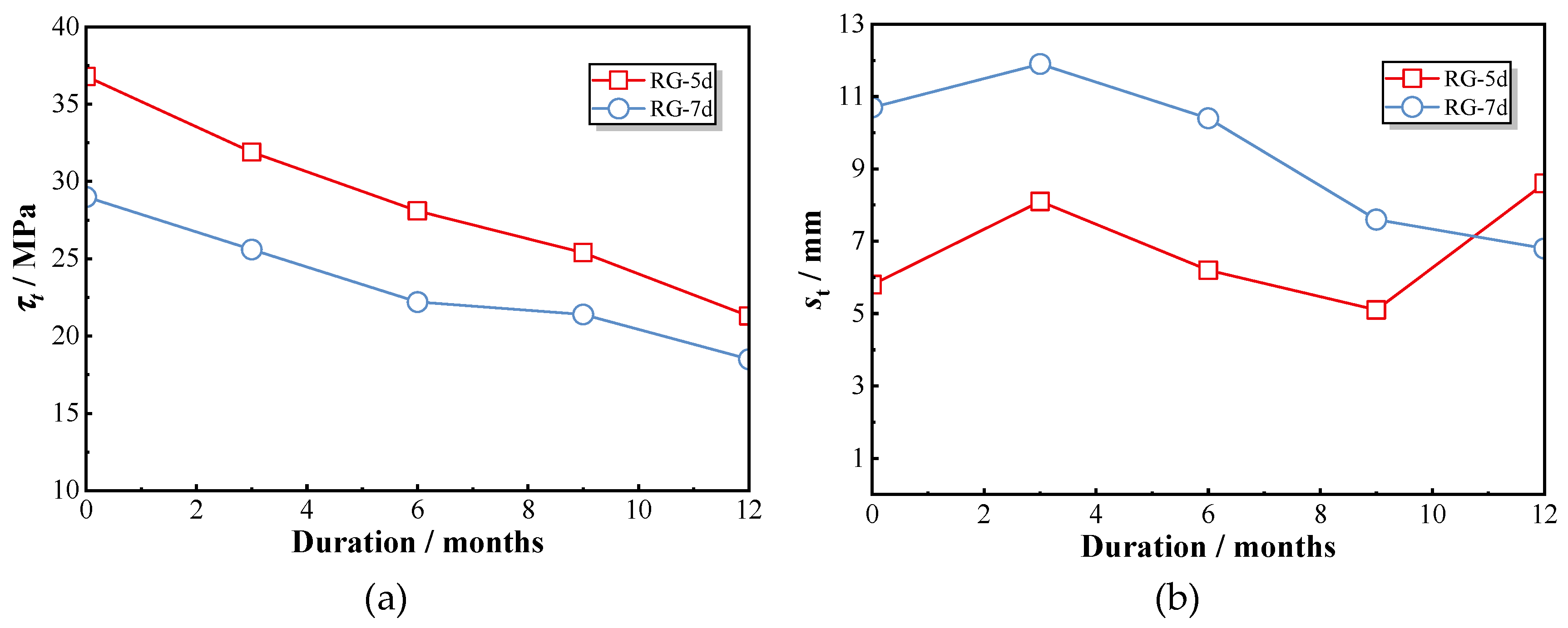

3.3. Effects of Bond Length

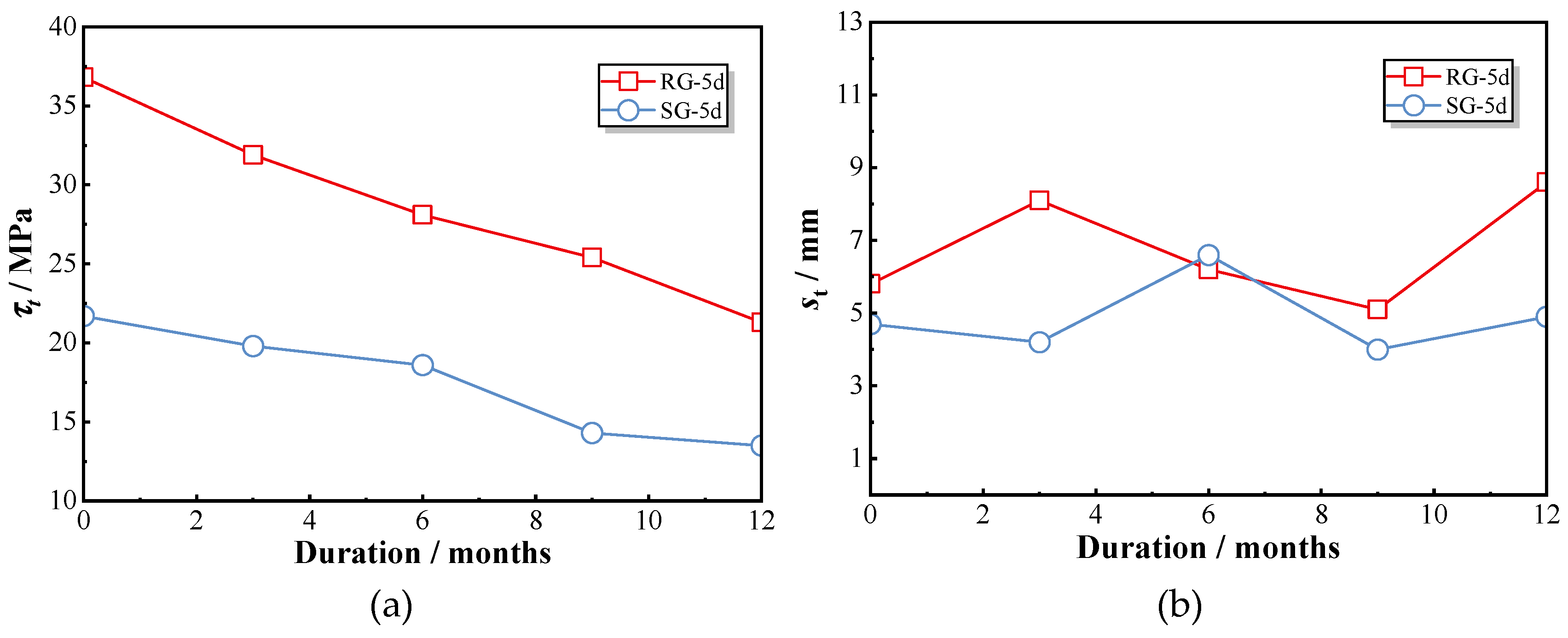

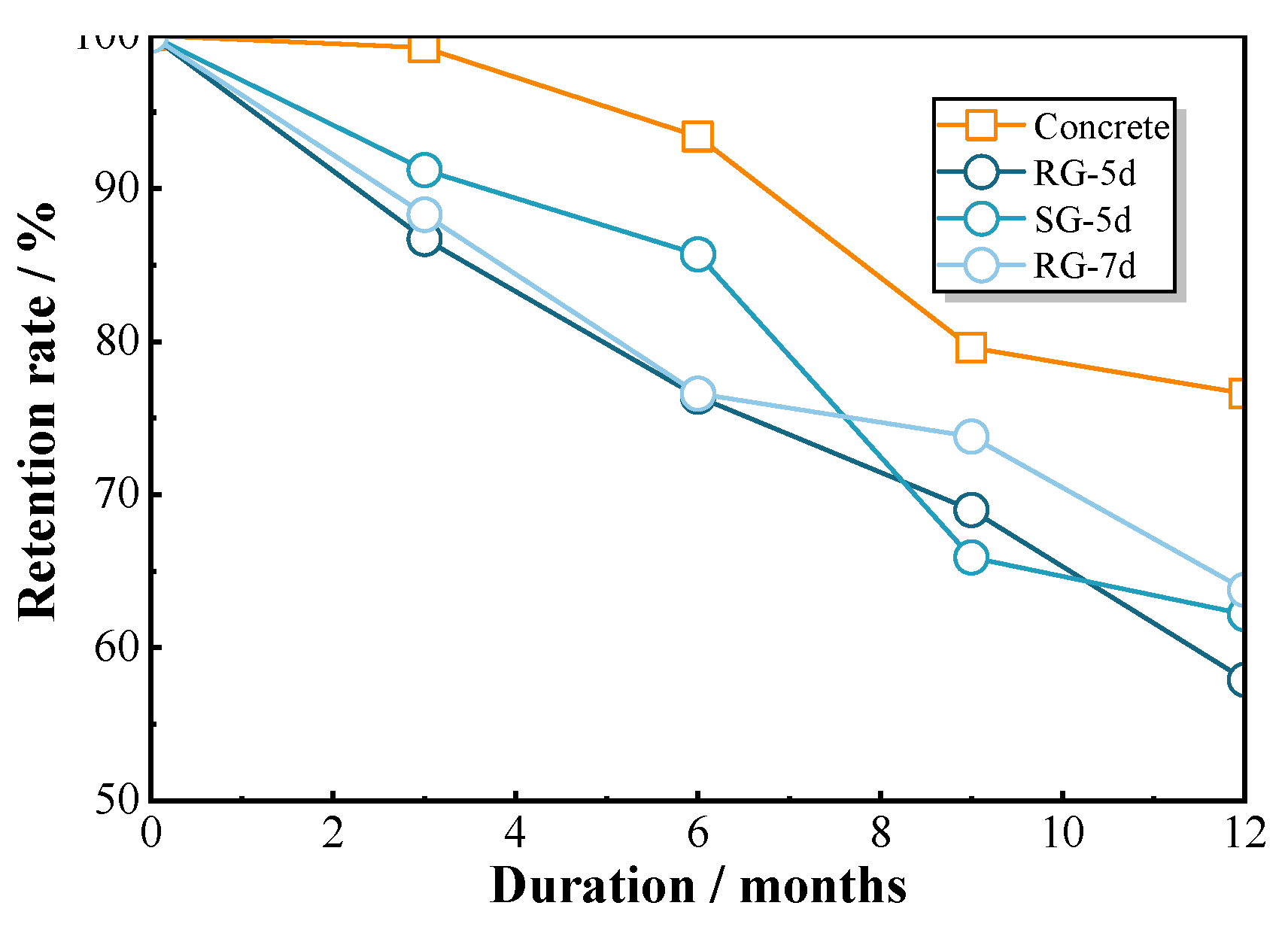

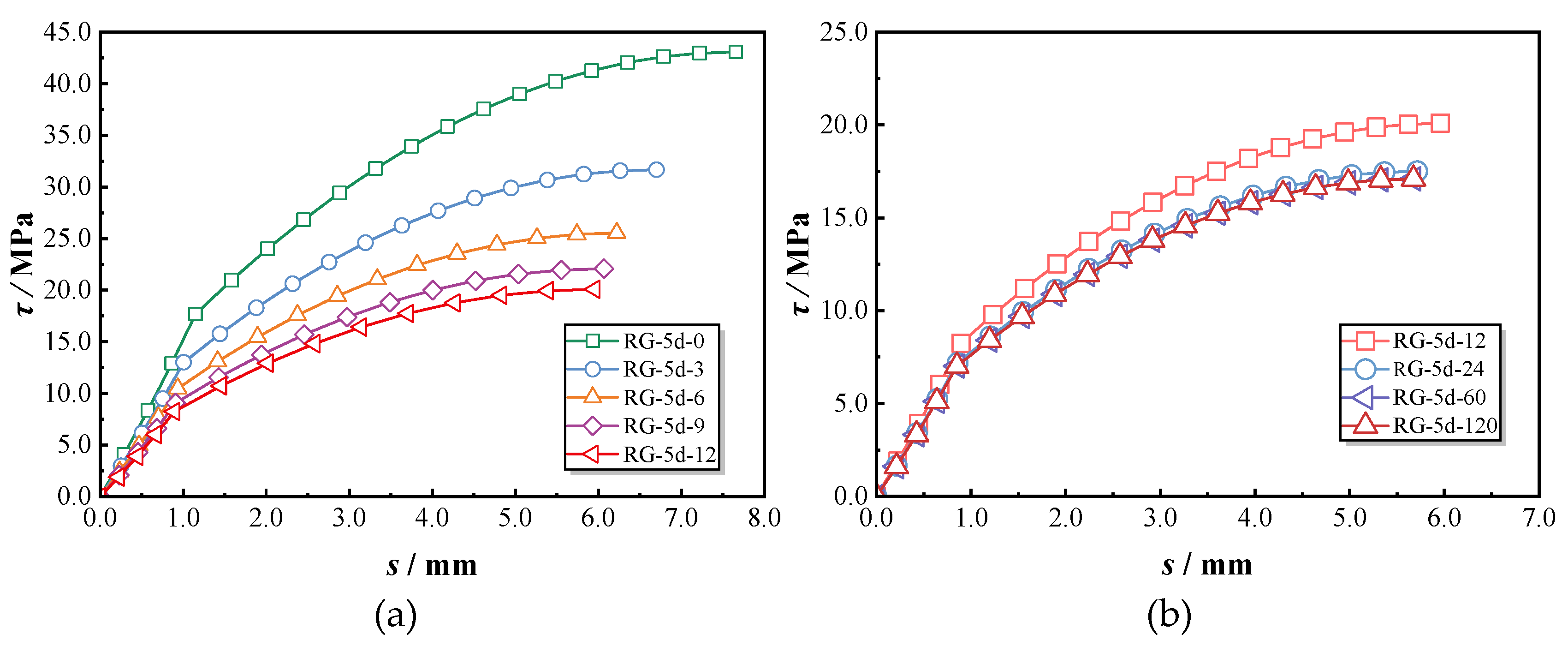

3.4. Effects of Chlorine Salt Erosion

4. Theoretical Modeling

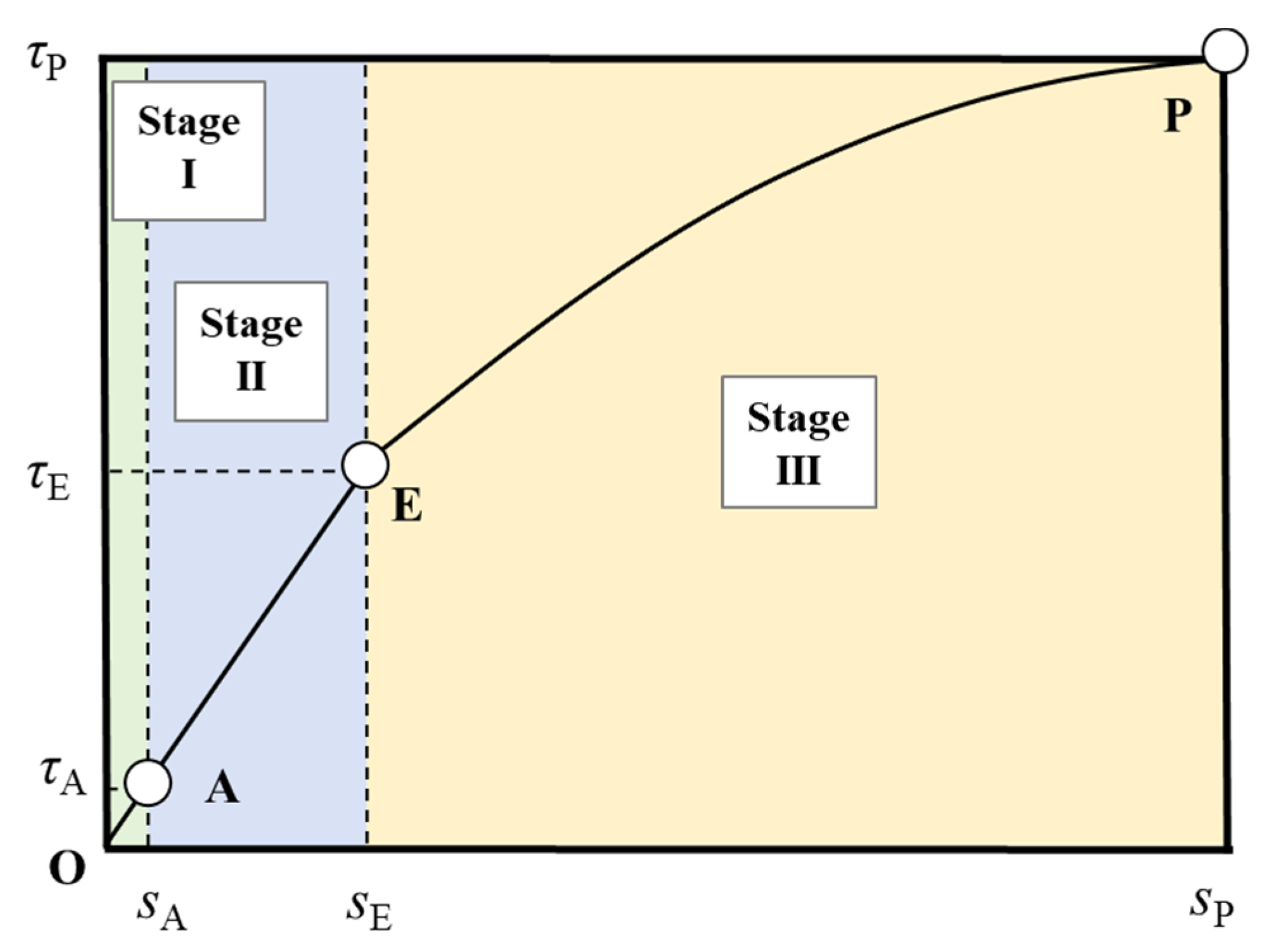

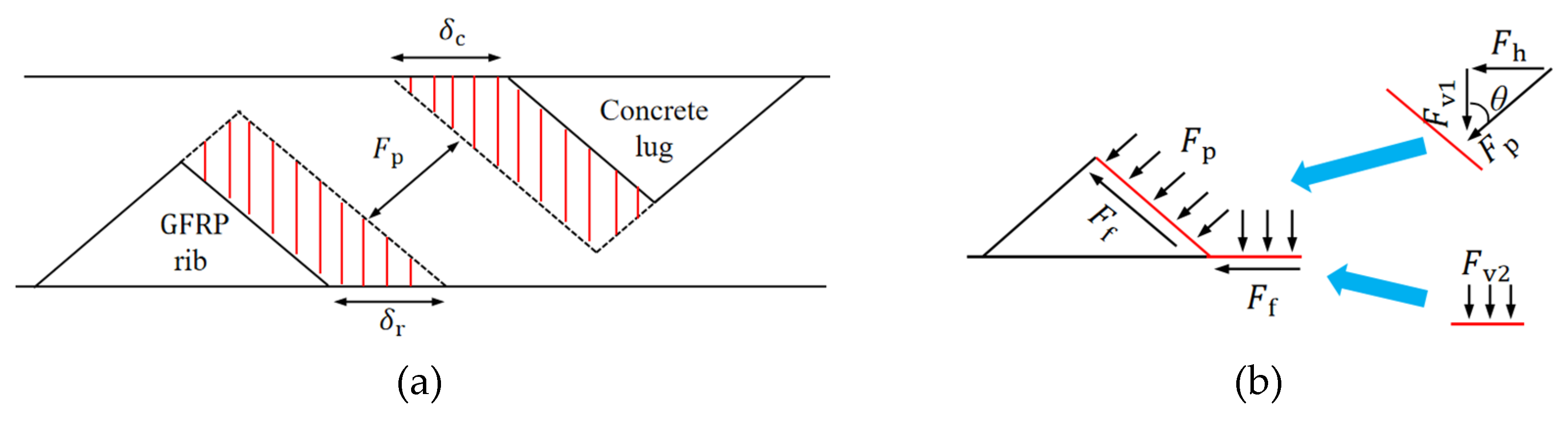

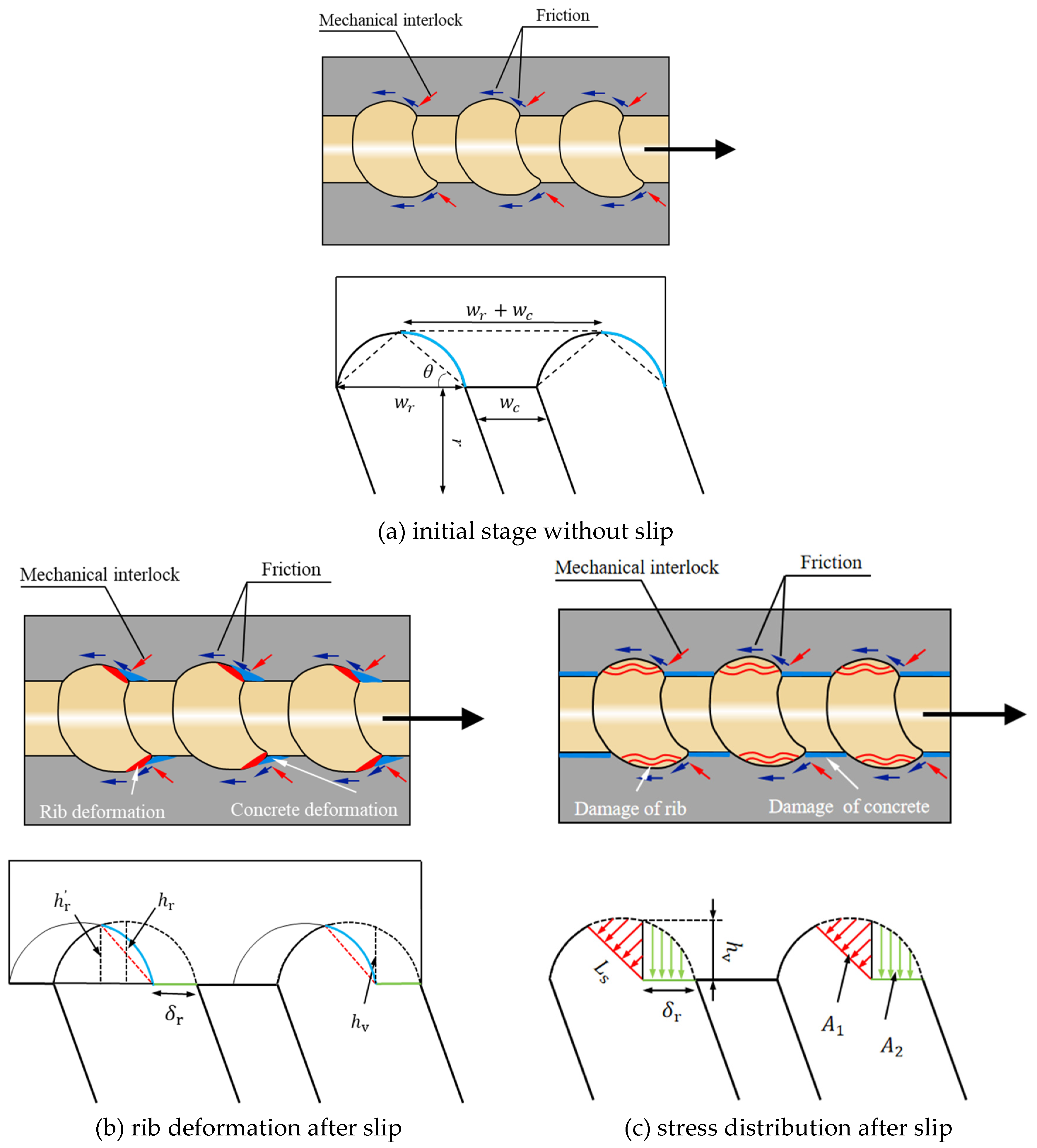

4.1. Analytical Model for Bond Stress and Slip Behavior

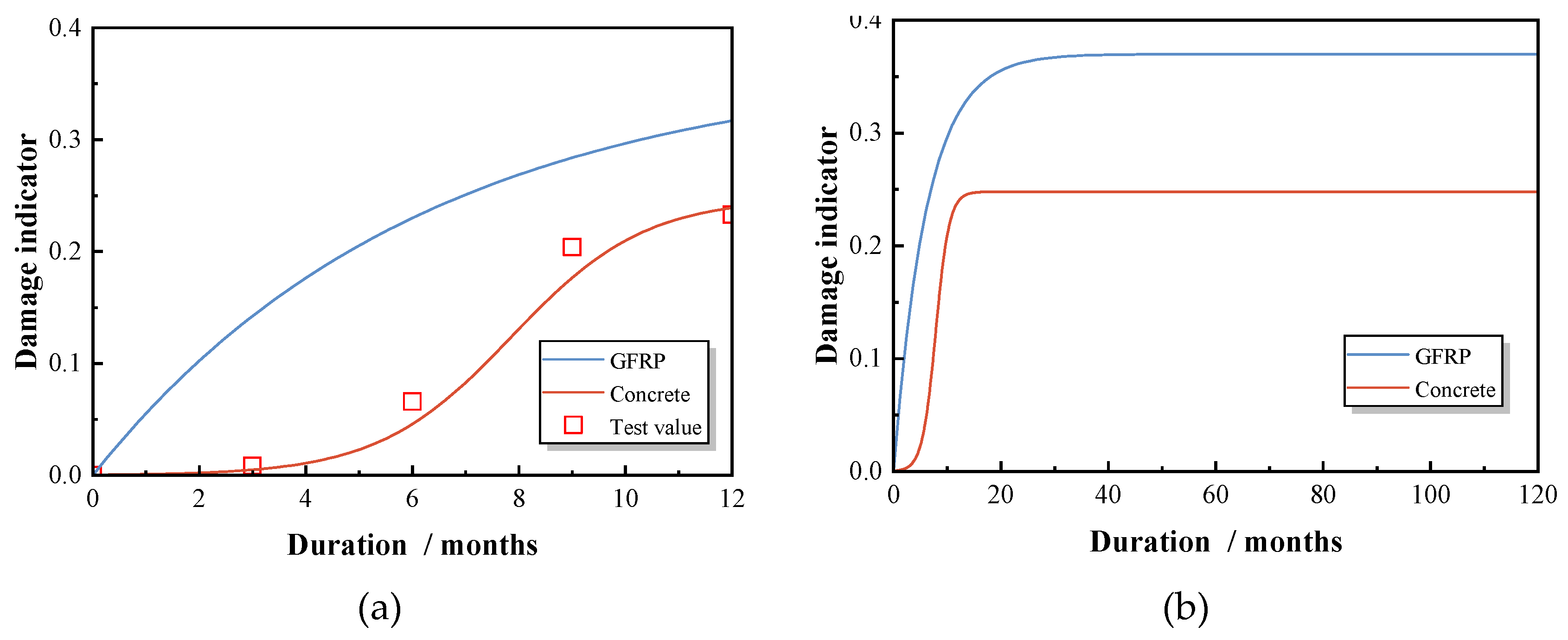

4.2. Model Modification Under Chloride Exposure

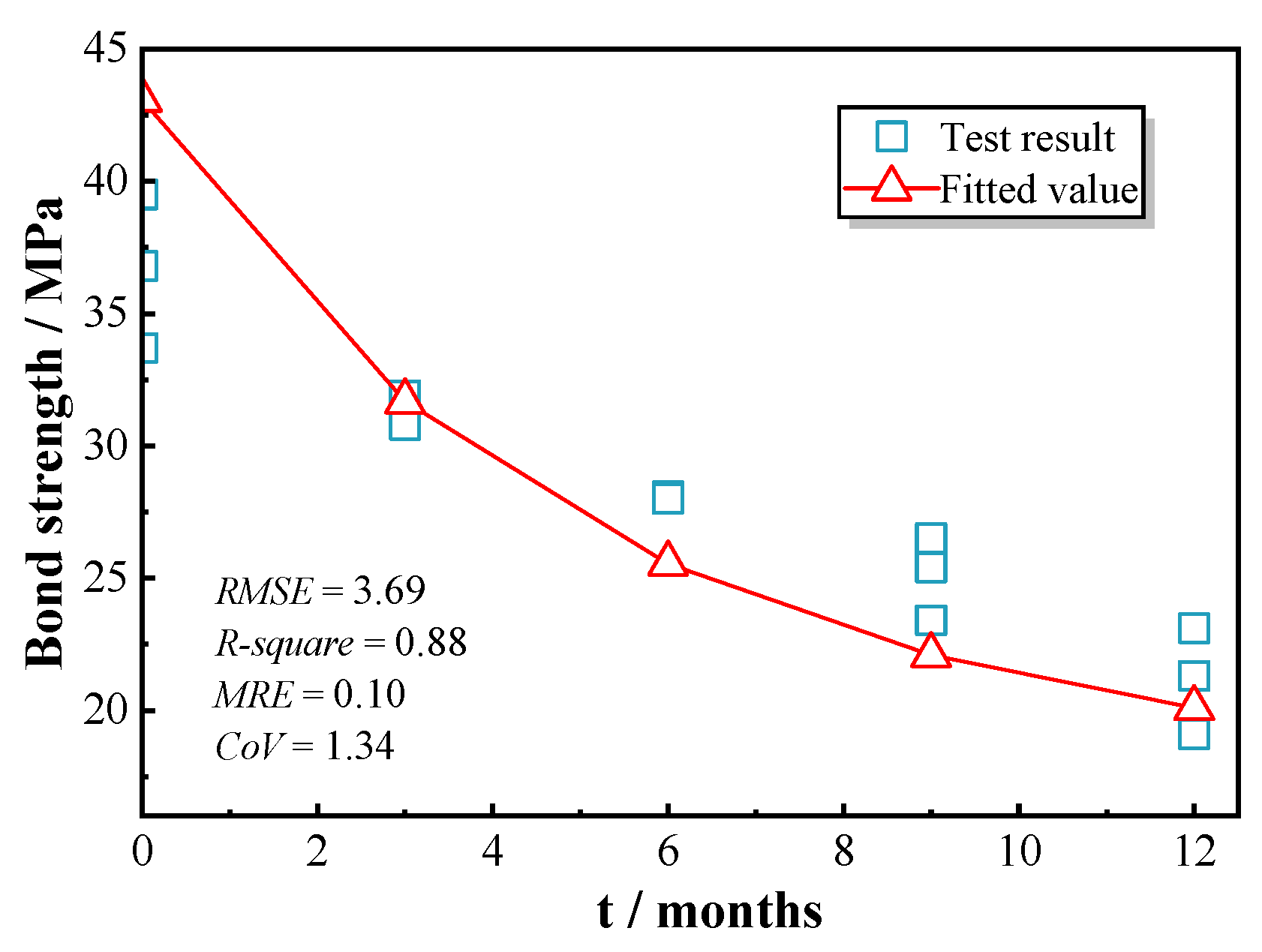

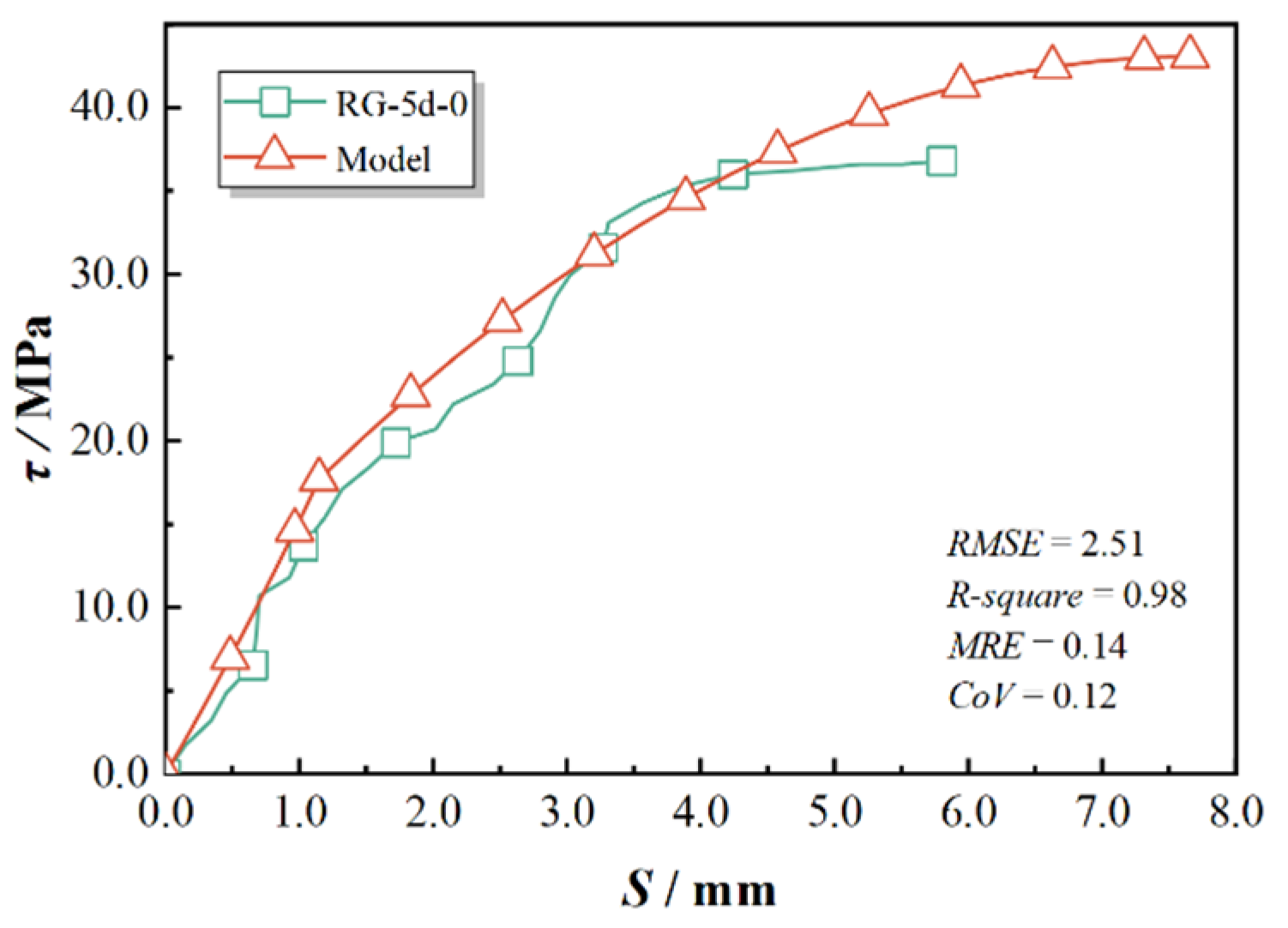

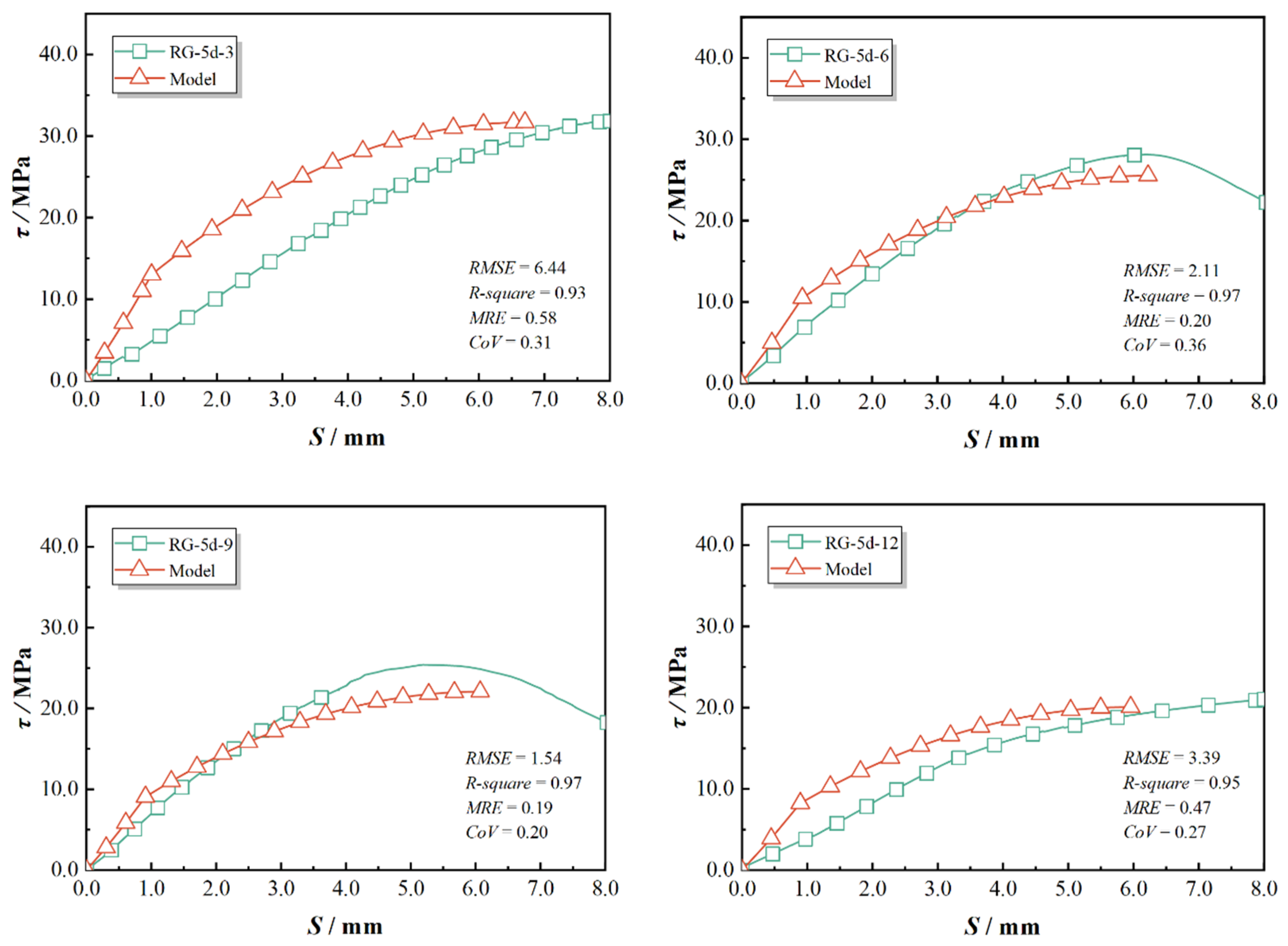

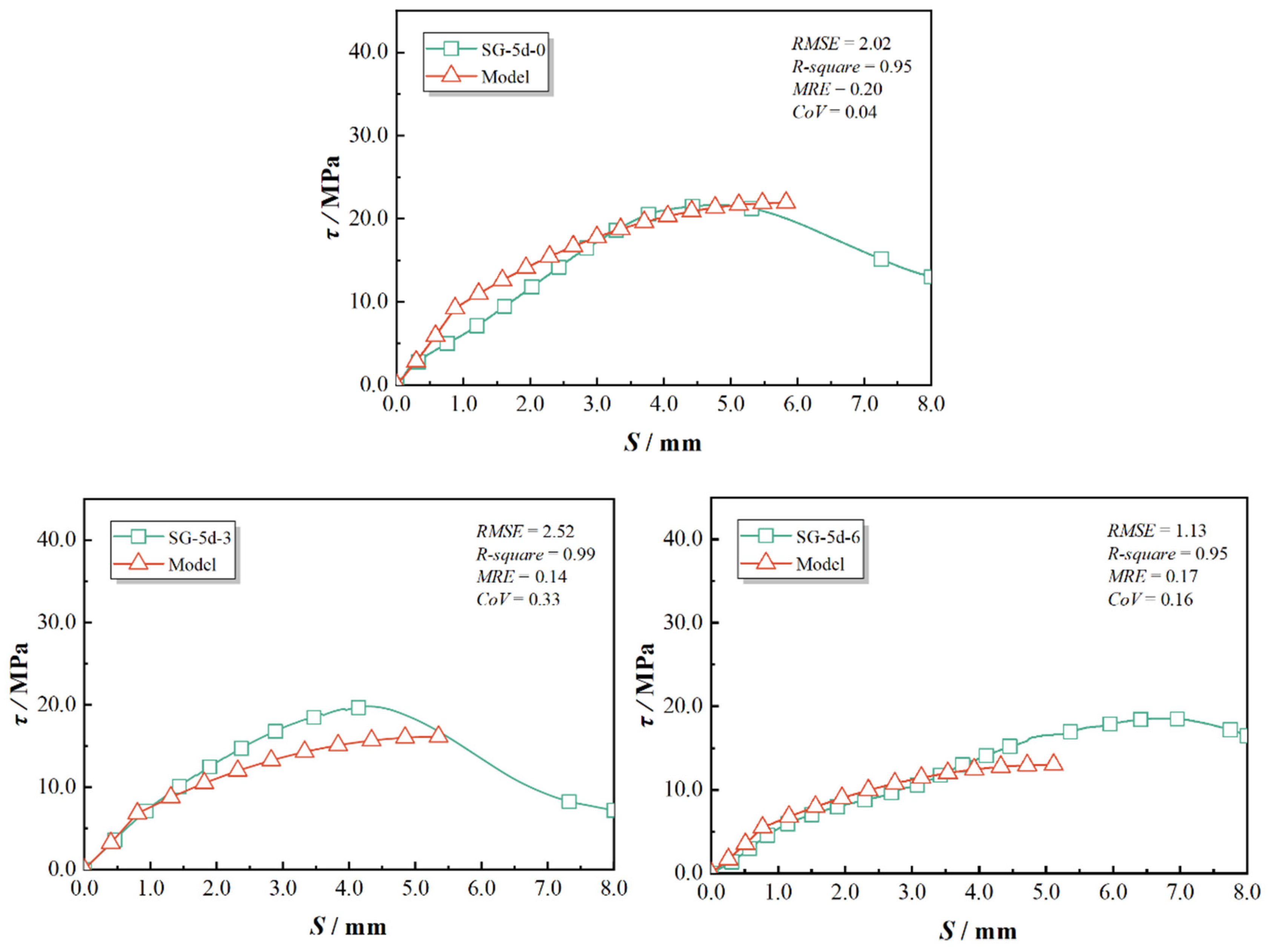

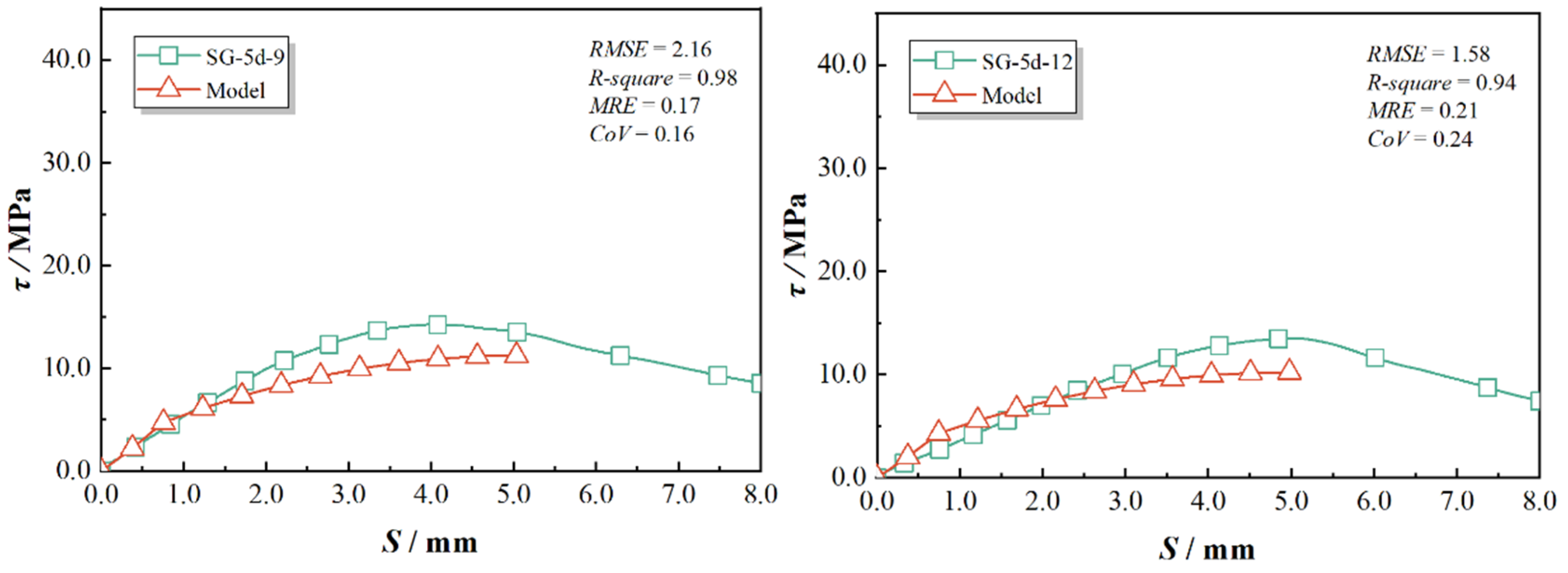

4.3. Model Validation

5. Model’s Application

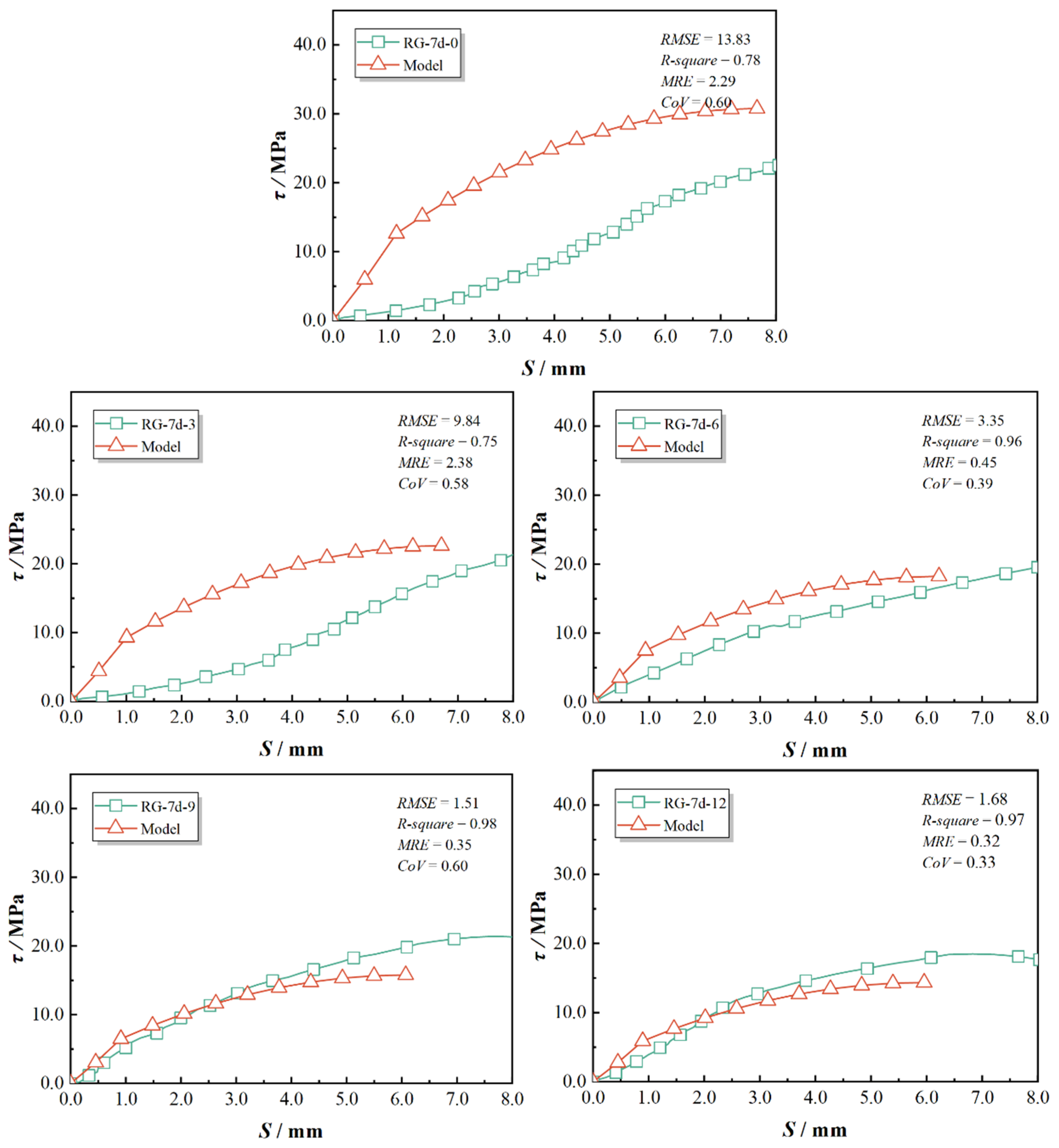

5.1. Analysis of Parametric Sensitivity

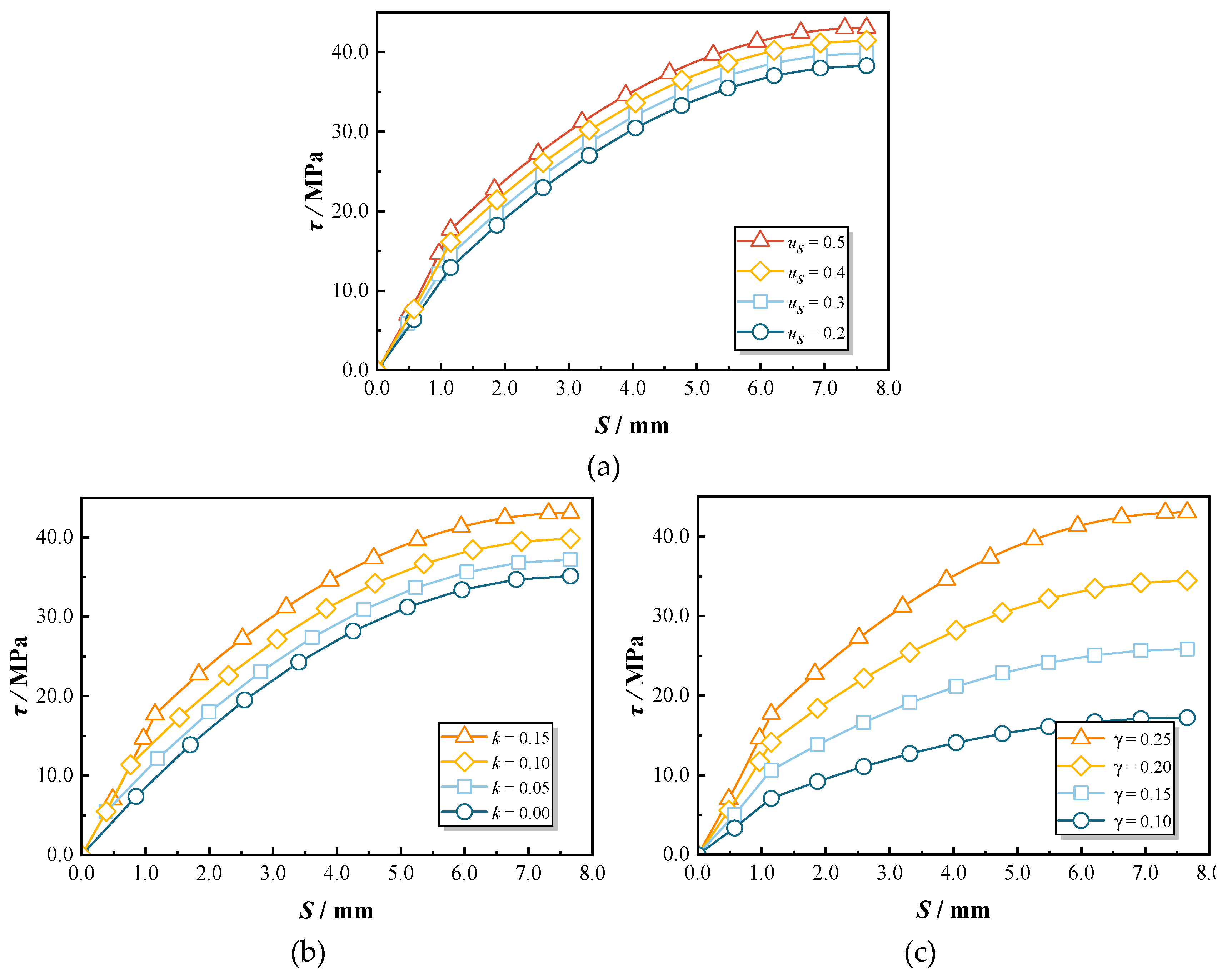

5.2. Long-Term Bond Performance Prediction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

References

- Li, J.; Mai, Z.; Xie, J. Durability of components of FRP-concrete bonded reinforcement systems exposed to chloride environments. Compos Struct 2022, 279, 114697. [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Lin, Z.; Yang, M. Bond mechanism and bond strength of GFRP bars to concrete: A review. Compos Part B-Eng 2016, 98, 56-69.

- Tafsirojjaman, T.; Fawzia, S.; Thambiratnam, D.P. Performance of FRP strengthened full-scale simply-supported circular hollow steel members under monotonic and large-displacement cyclic loading. Eng Struct 2021, 242, 112522. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Hao, Z.; Liang, Q. Durability assessment of GFRP bars exposed to combined accelerated aging in alkaline solution and a constant load. Eng Struct 2023, 297, 116990. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wei, Y.; Shen, C. Compression performance of FRP-steel composite tube-confined ultrahigh-performance concrete (UHPC) columns. Thin Wall Struct 2023, 192, 111152. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Wei, W.; Liu, F. Bond behaviour of recycled aggregate concrete with basalt fibre-reinforced polymer bars. Compos Struct 2021, 256, 113078. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Z. Mechanical behavior and durability of coral aggregate concrete and bonding performance with fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) bars: A critical review. J Clean Prod 2021, 289, 125652. [CrossRef]

- Machello, C.; Bazli, M.; Rajabipour, A. FRP bar and concrete bond durability in seawater: A meta-analysis review on degradation process, effective parameters, and predictive models. Structures 2024, 62, 106231. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamrani, A.; Alnahhal, W. Bond durability of sand coated and ribbed basalt FRP bars embedded in high-strength concrete. Constr Build Mater 2023, 406, 133385. [CrossRef]

- Gravina, R.J.; Li, J.; Smith, S.T. Environmental durability of FRP bar-to-concrete bond: Critical review. J Compos Constr 2020, 24(4), 03120001. [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Ma, K.; Chen, Z. Bond-slip and bond strength models for FRP bars embedded in ultra-high-performance concrete: A critical review. Structures 2024, 64, 106551. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhou, Y. Xing, F. Bond behavior and failure mechanism of fiber-reinforced polymer bar–engineered cementitious composite interface. Eng Struct 2021, 243, 112520.

- Wang, Y.L.; Guo, X.Y.; Shu, S.Y.H. Effect of salt solution wet-dry cycling on the bond behavior of FRP-concrete interface. Constr Build Mater 2020, 254, 119317. [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Yin, S.; Lin, F. Study on bond performance between seawater sea-sand concrete and BFRP bars under chloride corrosion. Constr Build Mater 2023, 371, 130718.

- Solyom, S.; Balázs, G.L. Bond of FRP bars with different surface characteristics. Constr Build Mater 2020, 264, 119839. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X. Bond of steel-FRP composite bar embedded in FRP-confined concrete: Behavior, mechanism, and strength model. Eng Struct 2024, 318, 118693. [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Zeng, J.; Huang, B. Bond performance of FRP bars in plain and fiber-reinforced geopolymer under pull-out loading. J Build Eng 2022, 57, 104893. [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Ai, Z.; Feng, Z. Interfacial bond behavior between ribbed CFRP bars and UHPFRC: effects of anchorage length and cover thickness. Eng Struct 2023, 286, 116140. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Mao, W.; Wei, W. Bond behavior and anchorage length of deformed bars in steel-polyethylene hybrid fiber engineered cementitious composites. Eng Struct 2022, 252, 113675. [CrossRef]

- Machello, C.; Bazli, M.; Rajabipour, A. FRP bar and concrete bond durability in seawater: A meta-analysis review on degradation process, effective parameters, and predictive models. Structures 2024, 62, 106231. [CrossRef]

- El-Nemr, A.; Ahmed, E.A.; Barris, C. Bond performance of fiber reinforced polymer bars in normal-and high-strength concrete. Constr Build Mater 2023, 393, 131957. [CrossRef]

- Nepomuceno, E.; Sena-Cruz, J.; Correia, L. Review on the bond behavior and durability of FRP bars to concrete. Constr Build Mater 2021, 287, 123042. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gravina, R.J.; Smith, S.T. Bond strength and bond stress-slip analysis of FRP bar to concrete incorporating environmental durability. Constr Build Mater 2020, 261, 119860. [CrossRef]

- Corres, E.; Muttoni, A. Local bond-slip model based on mechanical considerations. Eng Struct 2024, 314, 118190. [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Chen, L.; Shan, Z. Experimental and theoretical study on bond behavior of helically wound FRP bars with different rib geometry embedded in ultra-high-performance concrete. Eng Struct 2023, 281, 115769. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Cox, J.V. Radial Elastic Modulus for the Interface between FRP Reinforcing Bars and Concrete. J Reinf Plastl Comp 2002, 21, 14. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, L.; Lin, J. Bond performance between ribbed BFRP bar and seawater sea-sand concrete: Influences of rib geometry. Structures 2024, 65, 106660. [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Chen, L.; Shan, Z. Experimental and theoretical study on bond behavior of helically wound FRP bars with different rib geometry embedded in ultra-high-performance concrete. Eng Struct 2023, 281, 115769. [CrossRef]

- Karagöl, F.; Yegin, Y.; Polat, R. The influence of lightweight aggregate, freezing–thawing procedure and air entraining agent on freezing–thawing damage. Struct Concrete 2018, 19(5), 1328-1340. [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Singh, B.; Bhardwaj, B. Strength performance of recycled aggregate concretes containing mineral admixtures and their performance prediction through various modeling techniques. J Build Eng 2019, 24, 100741. [CrossRef]

- Choi, P.; Yeon, J. H.; Yun, K.K. Air-void structure, strength, and permeability of wet-mix shotcrete before and after shotcreting operation: The influences of silica fume and air-entraining agent. Cement Concrete Comp 2016, 70, 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Xian, G. Long-term durability of basalt- and glass-fibre reinforced polymer (BFRP/GFRP) bars in seawater and sea sand concrete environment. Constr Build Mater 2017, 139, 467-489. [CrossRef]

- Iwama, K.; Kai, M.; Dai, J. Physicochemical-mechanical simulation of the short-and long-term performance of FRP reinforced concrete beams under marine environments. Eng Struct 2024, 308, 118051. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Hadi, M.N.S. Friction coefficient between FRP pultruded profiles and concrete. Mater Struct 2018, 51(5), 120. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Cox, J.V. Radial Elastic Modulus for the Interface between FRP Reinforcing Bars and Concrete. J Reinf Plastl Comp 2002, 21, 14. [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z. Developing a model for chloride transport through concrete considering the key factors. Case Stud Constr Mat 2022, 17, e01168. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; A new analytical model for stress distribution in the rock bolt under axial loading. Int J Rock Mech Min 2024, 176, 105690. [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.F.M.; Ahmed, S.E.A.S.; Wu, Z. Bar surface treatment effect on the bond-slip behavior and mechanism of basalt FRP bars embedded in concrete. Constr Build Mater 2021, 289, 122844. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Xian, G. Long-term durability of basalt- and glass-fibre reinforced polymer (BFRP/GFRP) bars in seawater and sea sand concrete environment. Constr Build Mater 2017, 139, 467-489. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Chloride environment | FRP bar |

Prediction model |

||

| Environment | Duration (day) | Bond length | Surface texture | ||

| Nelson et al. (2024) | / | / | / | / | Mathematical |

| Wang et al. (2024) | / | / | 5d | RB | / |

| Shi et al. (2024) | / | / | 5d /10d/15d | SM | Mathematical |

| Zhou et al. (2024) | / | / | 5d | SC / RB | Mathematical |

| Zhang et al. (2024) | Dry–wet cycles | 360 | 5d | RB | |

| El-Nemr et al. (2023) | / | / | 5d | SC / RB | Mathematical |

| Lu et al. (2023) | Emersion | 180 | 5d | RB | Mathematical |

| Al-Hamrani et al. (2023) | Emersion | 270 | 5d | SC / RB | Mathematical |

| Chen et al. (2023) | / | / | 5d | RB | / |

| Hussain et al. (2022) | Emersion | 90 | 5d /10d/15d | RB | / |

| Yang et al. (2022) | / | / | 3d /5d | RB | Mechanical |

| Huang et al. (2020) | / | / | 5d | SC / RB | Mathematical |

| Taha et al. (2020) | Emersion | 90 | 5d | RB | / |

| Strength grade | Water-cement ratio | Water | Cement | Sand | Stones |

| C40 | 0.49 | 220 | 449 | 615 | 1116 |

| Group | Specimen | Surface texture | Diameter | Bond length | Chloride duration |

| RG-5d | RG-5d-0 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 5 d | 0 months |

| RG-5d-3 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 5 d | 3 months | |

| RG-5d-6 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 5 d | 6 months | |

| RG-5d-9 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 5 d | 9 months | |

| RG-5d-12 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 5 d | 12 months | |

| SG-5d | SG-5d-0 | Sand-coated | 12 mm | 5 d | 0 months |

| SG -5d-3 | Sand-coated | 12 mm | 5 d | 3 months | |

| SG -5d-6 | Sand-coated | 12 mm | 5 d | 6 months | |

| SG -5d-9 | Sand-coated | 12 mm | 5 d | 9 months | |

| SG -5d-12 | Sand-coated | 12 mm | 5 d | 12 months | |

| RG-7d | RG-7d-0 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 7 d | 0 months |

| RG-7d-3 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 7 d | 3 months | |

| RG-7d -6 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 7 d | 6 months | |

| RG-7d-9 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 7 d | 9 months | |

| RG-7d-12 | Threaded ribbed | 12 mm | 7 d | 12 months |

| Specimen | Failure patterns | ||||

| Value / MPa | Rate / % | Value / mm | Rate / % | ||

| RG-5d-0 | A | 36.8 | 100.0 | 5.8 | 100.0 |

| RG-5d-3 | B | 31.9 | 86.7 | 8.1 | 139.7 |

| RG-5d-6 | B | 28.1 | 76.4 | 6.2 | 106.9 |

| RG-5d-9 | B | 25.4 | 69.0 | 5.1 | 87.9 |

| RG-5d-12 | B | 21.3 | 57.9 | 8.6 | 148.3 |

| SG-5d-0 | B | 21.7 | 100.0 | 4.7 | 100.0 |

| SG -5d-3 | B | 19.8 | 91.2 | 4.2 | 89.4 |

| SG -5d-6 | B | 18.6 | 85.7 | 6.6 | 140.4 |

| SG -5d-9 | B | 14.3 | 65.9 | 4.0 | 85.1 |

| SG -5d-12 | B | 13.5 | 62.2 | 4.9 | 104.3 |

| RG-7d-0 | A | 29.0 | 100.0 | 10.7 | 100.0 |

| RG-7d-3 | A | 25.6 | 88.3 | 11.9 | 111.2 |

| RG-7d -6 | A | 22.2 | 76.6 | 10.4 | 97.2 |

| RG-7d-9 | B | 21.4 | 73.8 | 7.6 | 71.0 |

| RG-7d-12 | B | 18.5 | 63.8 | 6.8 | 63.6 |

| Specimen | Failure patterns | ||||||

| Rate | Average | Rate | Average | ||||

| RG-5d-0 | A | 43.08 | 1.17 | 0.98 | 7.66 | 1.32 | 1.01 |

| RG-5d-3 | B | 31.68 | 0.99 | 6.70 | 0.83 | ||

| RG-5d-6 | B | 25.54 | 0.91 | 6.22 | 1.00 | ||

| RG-5d-9 | B | 22.09 | 0.87 | 6.07 | 1.19 | ||

| RG-5d-12 | B | 20.09 | 0.94 | 5.96 | 0.69 | ||

| SG-5d-0 | B | 21.94 | 1.01 | 0.81 | 5.83 | 1.24 | 1.11 |

| SG-5d-3 | B | 16.13 | 0.81 | 5.35 | 1.27 | ||

| SG-5d-6 | B | 13.01 | 0.70 | 5.11 | 0.77 | ||

| SG-5d-9 | B | 11.25 | 0.79 | 5.04 | 1.26 | ||

| SG-5d-12 | B | 10.23 | 0.76 | 4.98 | 1.02 | ||

| RG-7d-0 | A | 30.77 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 7.66 | 0.72 | 0.73 |

| RG-7d-3 | A | 22.63 | 0.88 | 6.70 | 0.56 | ||

| RG-7d-6 | A | 18.24 | 0.82 | 6.22 | 0.60 | ||

| RG-7d-9 | B | 15.78 | 0.74 | 6.07 | 0.80 | ||

| RG-7d-12 | B | 21.2 | 1.15 | 6.43 | 0.95 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).