1. Introduction

The deterioration of durability in concrete structures has become a significant challenge for the sustainable growth of the concrete industry.

Enhancing the durability and structural integrity of infrastructure, especially reinforced concrete structures is of utmost importance due to the substantial expenses associated with their maintenance and replacement (Cheng et al., 2020a; Bertolini et al., 2004; Broomfield, 2002). In this context, various studies have investigated the effectiveness of cement-based construction materials as a strengthening material for existing concrete structures. As a part of such efforts, ultra-high performance fiber reinforced concrete (UHPFRC) was developed. The UHPFRC stands out due to its outstanding mechanical properties (compressive strength over 150 MPa, tensile strength over 8 MPa), energy absorption capacity, material ductility, fatigue, and resistance to cracking (Wu et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2017; Reddy & P. Ramadoss, 2017; Abbas et al., 2017; Kusumawardaningsih et al., 2015). These remarkable properties of UHPFRC were shown to enhance the durability of reinforced concrete structures when used as a strengthening material, making UHPFRC suitable for repair applications (Alaee & Karihaloo, 2003; Farhat et al., 2007; Habel et al., 2006; Martinola et al., 2010; Beschi et al., 2011; Noshiravani et al., 2014; Bastien-Masse & Brühwiler, 2016; Lampropoulos et al., 2016; Hussein, 2015).

However, the use of epoxy adhesive material to strengthen or retrofit damaged reinforced concrete (RC) beams with UHPFRC strips is an area of concern due to its cost (Alaee & Karihaloo, 2003; Farhat et al., 2007). To address this, Hussein (2015) and Hussein and Amleh (2015) introduced a novel approach for enhancing the mechanical strength and durability of reinforced concrete structures while concurrently lowering industrial costs. This approach involves the integration of normal strength concrete (NSC) and UHPFRC materials within Composite Concrete Systems (CCS). In this system, UHPFRC is used in the part of the structure that requires high mechanical loading and/or is exposed to harsh environmental conditions, while NSC is applied elsewhere. More recently, various investigations have been conducted to examine the flexural and cracking behaviour of the bonded UHPFRC/NSC system (Khan and Abbas (2016); Liu et al. (2022), Yalcinkaya (2021)). Despite the promise of CCS, limited research has been conducted on the durability of the bond between NSC and UHPFRC, especially in aggressive environments (Hussein et al., 2020; Baloch et al., 2021). A clear gap of knowledge was noticed in the literature regarding the magnesium sulfate resistance of the bonding area between the NSC and UHPFRC materials, especially since magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) is known to cause the quickest and most aggressive deterioration for cementitious materials (Siad et al., 2015). As noted by Golop and Taylor (1995), magnesium sulfate exhibits a greater corrosive effect compared to sodium sulfate. These aggressive agents are commonly found in a wide range of sources, such as underground water, soil, seawater, or industrial wastewater, with high potential presence around infrastructures.

The deterioration of concrete in sulfate-rich environments, particularly those containing magnesium sulfate, poses significant challenges to structural integrity and durability. The impact of magnesium sulfate on concrete composites is influenced by chemical reactions, physical crystallization, and environmental factors, leading to degradation phenomena such as cracking, spalling, and strength reduction. Magnesium sulfate is particularly detrimental due to its ability to replace calcium ions in hydration products, leading to the formation of brucite and gypsum, which weaken the concrete matrix (Zhang et al., 2024). High sulfate concentrations exacerbate this degradation process through combined chemical attack and physical crystallization, as observed in studies on infrastructure exposed to aggressive environments. For instance, Zhang et al. (2024) examined sulfate-rich conditions in the Jinyan Bridge case study and highlighted the importance of hydrophobic and densification technologies in enhancing concrete resistance to sulfate-induced deterioration. The use of anti-sulfate erosion inhibitors was found to be effective in reducing water absorption and mitigating corrosive reactions, thereby improving long-term durability.

To counteract the adverse effects of sulfate attack, researchers have explored the role of high-performance concrete (HPC) and supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) in enhancing durability. Shannag and Shaia (2003) demonstrated that HPC, due to its lower permeability and denser microstructure, exhibited greater resistance to sulfate attack, with reduced expansion and cracking. Mousavinezhad et al. (2024) proposed accelerated testing methods to assess sulfate resistance, showing that metakaolin significantly improves sulfate resistance, whereas silica fume and natural pozzolan had limited impact. Their findings suggest that using Type I/II cement with 15% metakaolin provides optimal resistance to sulfate degradation. In environments where chloride exposure is also a concern, Jee and Pradhan (2023) studied the effect of magnesium sulfate in chloride solutions on concrete microstructure and chloride diffusion. Their study revealed that while magnesium sulfate reduces chloride diffusion by filling pores with expansive compounds like ettringite and brucite, it simultaneously decreases chloride-binding capacity by transforming calcium hydroxide into brucite, leading to lower pore solution pH.

The impact of magnesium sulfate on self-compacting and composite concrete systems has been widely studied. Hassan et al. (2013) found that incorporating supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) such as rice husk ash (RHA) enhanced sulfate resistance by refining the microstructure and reducing permeability. Zhu et al. (2024) examined ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) in composite systems under chloride-sulfate attack, revealing significant bond zone degradation due to microcracking and interfacial deterioration, though UHPC layers maintained their dense microstructure and superior durability. Mostofinejad et al. (2016) further demonstrated that a 5% magnesium sulfate solution caused the most damage, while mixtures with 15% limestone powder and 20% slag exhibited the highest resistance, highlighting the importance of optimizing cement replacement materials to improve sulfate durability.

While UHPFRC has been widely recognized for enhancing the structural performance of infrastructure composed of normal or high-strength concrete, the effect of aggressive environments on the bond between these materials remains underexplored—particularly in magnesium sulfate conditions. A significant knowledge gap exists in understanding how sulfate exposure affects the mechanical resistance of the bonding layer in composite concrete systems (CCS). This study addresses this issue by evaluating the flexural performance of CCS subjected to severe MgSO₄ exposure, involving cycles of immersion in a concentrated magnesium sulfate solution followed by oven drying at elevated temperatures.

Specifically, this research investigates the bond integrity between UHPFRC and NSC layers under sulfate attack, assessing the role of steel fiber content in enhancing durability. The study examines fiber concentrations of 0%, 1%, 1.5%, and 2% over a 180-day exposure period to determine their effect on flexural behavior. By providing insights into the performance of these hybrid systems in harsh conditions, the findings will contribute to the development of more resilient concrete composites for sulfate-rich environments.

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Material Properties

The mix proportions of UHPFRC and NSC used in this study are detailed in

Table 1. For UHPFRC, portland cement and silica fume were the primary cementitious materials. Fine sand with particle size smaller than 0.5 mm served as the fine aggregate. Ground quarts with a particle size smaller than 0.2 mm were incorporated as a filler. Water and superplasticizer were added during the mix. As for NSC, the mix consists of Portland cement, sand with a 5 mm maximum particle size, coarse aggregate with a 19 mm maximum particle size, and water. To investigate the effect of the fiber content on flexural performance, steel fibers were added at volumes of 0, 1, 1.5, and 2% of the total volume of UHPFRC. The fibers consisted of straight steel fibers with a length of 13 mm, a diameter of 0.2 mm, and a tensile strength of 2500 MPa.

For the mechanical properties, the compressive strength (

f’c) and the split tensile strength (

fsp) for both UHPFRC and NSC were measured according to ASTM C39 and ASTM C496 standards, respectively. Tests were conducted on cylinders with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 200 mm. The reported values are the average of at least three specimens for each mechanical property, as summarized in

Table 2. The composite members' flexural strength was determined using a four-point un-notched bending test, as per ASTM C1609. Tests were performed on beams with a cross-section of 100 × 100 mm and a length of 355 mm. The beams were loaded at a rate of 0.05 mm/min through displacement control.

2.2. Preparation of Test Specimens

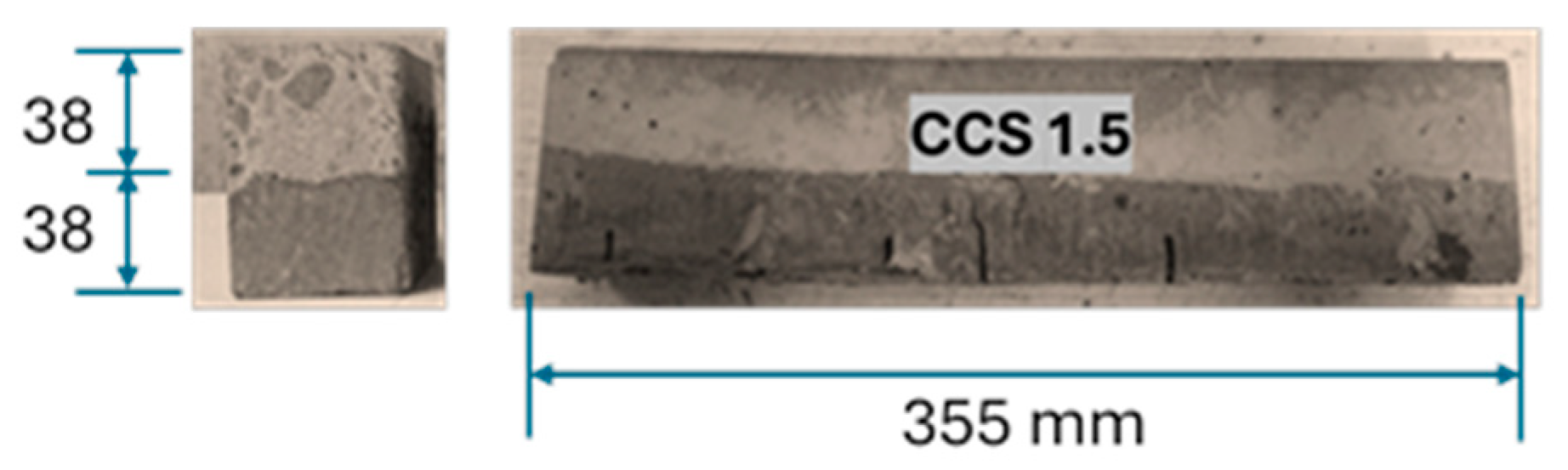

The CSS specimens were categorized into four series, differentiated by the fiber content in the UHPFRC layer. A total of sixty beam specimens, each measuring 50 × 76 × 355 mm with a clear span of 304 mm, were prepared. Each composite beam consisted of two layers: a 38 mm NSC layer on top and a 38 mm UHPFRC layer on the bottom, as shown in

Figure 1.

To assess changes in compressive strength, 70 mm cube specimens were also prepared, each consisting of a 35 mm NSC layer on top and a 35 mm UHPFRC layer on the bottom. The composite members were cast upside down to accommodate the longer setting time of the UHPFRC material compared to NSC, without any surface preparation between the two layers.

The CCS beams were cast from one end of the mold to the other without vibration to ensure uniform fiber alignment and dispersion. After casting, the specimens were sprayed with water, covered with plastic sheets, and stored at room temperature (22 ± 2°C) for 28 days. The specimens were classified into four CCS series based on the fiber volume content in the UHPFRC layer.

After the 28-day curing period, three samples from each CCS series were tested to determine mass, compressive strength, and flexural strength before initiating the drying-wetting cycles. In each series, six prisms and cubes were stored in freshwater tanks at room temperature (22 ± 2°C) as control specimens. Another six CCS samples were subjected to multiple immersion-drying cycles:

These cycles were repeated for 180 days, with the sulfate solution renewed every two weeks to maintain a high concentration of magnesium sulfate ions. After each immersion phase, the specimens were rinsed with water to remove altered products without affecting their physical integrity. After oven drying, specimens were left at room temperature for 2 hours to cool before starting the next immersion-drying cycle.

The specimens were labeled as follows:

The CCS composite prisms were designated as CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2, corresponding to the fiber volume percentage in the UHPFRC layer. All specimens were tested after 28 days of casting.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mass Change

The mass of each specimen was measured using a high-precision electronic scale with an accuracy of 0.1 g. The average mass of three specimens was recorded, and the mass-loss rate (MC) for each group was determined using the following Equation:

where m

0 represents the initial mass before any dry–wet cycles, and mn denotes the mass after n dry–wet cycles.

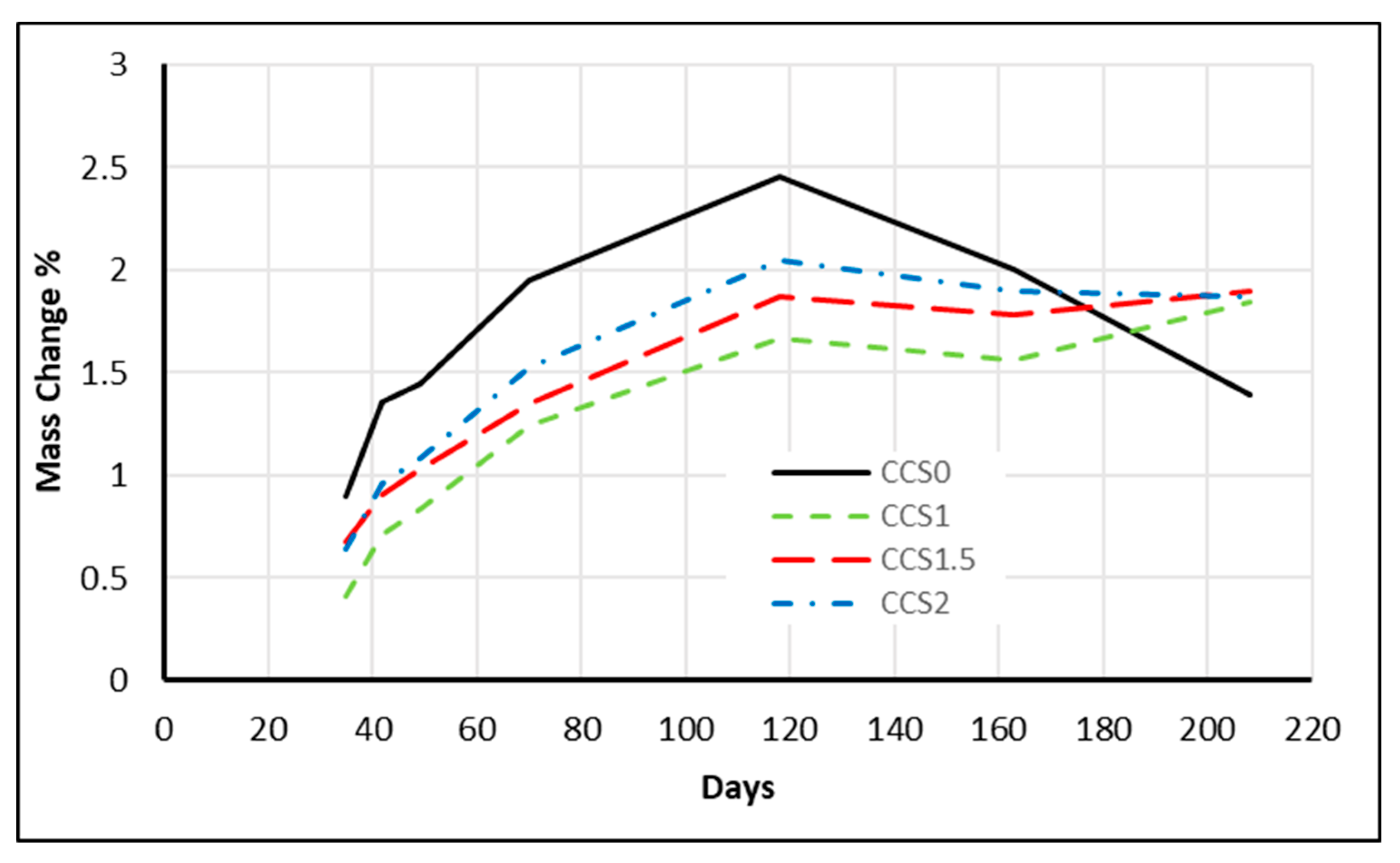

The mass variations in concrete specimens subjected to magnesium sulfate attack through drying-wetting cycles are shown in

Figure 2. The trend of mass change over time exhibits two distinct phases:

the increased stage and the decreased stage. In the increased stage, the mass of all specimens increased progressively during the first 120 days of exposure.. This initial gain can be attributed to sulfate-induced reaction products, which enhanced the compactness of the NSC layer. For the mass decrease phase after 120 days, a gradual decline in mass was observed. The CCS0 specimen (without fibers) exhibited a significant decrease, after 120 days, while specimens incorporating steel fibres showed only minor reductions in mass. The net mass gains after 120 days of exposure were around 2.45%, 1.66%, 1.87%, and 2.05% for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2, respectively. At the end of the immersion period (180 days), all specimen masses retained higher final masses compared to their initial values before sulfate exposure. The final mass increase percentages were around 1.39%, 1.84%, 1.90%, and 1.87% for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2, respectively.

The underlying mechanisms of the observed mass changes in concrete specimens can be explained by the following:

The initial stage of mass gains due to the reaction between sulfate ions and hydration products leads to the formation of ettringite and gypsum, which increase the compactness of the NSC layer. This densification temporarily improves the resistance to sulfate penetration.

However, with continuous exposure to sulfate attack, the expansion of these reaction products forms more microcracks within the concrete, which accelerate the penetration of sulfate solution into the specimens. Subsequent reactions with existing hydration products either lead to the formation of non-cementitious magnesium silicate hydrate or cause the crystallization of salts during the drying-wetting cycles (Siad et al., 2015; Jiang & Niu, 2016).

3.2. Compressive Strength

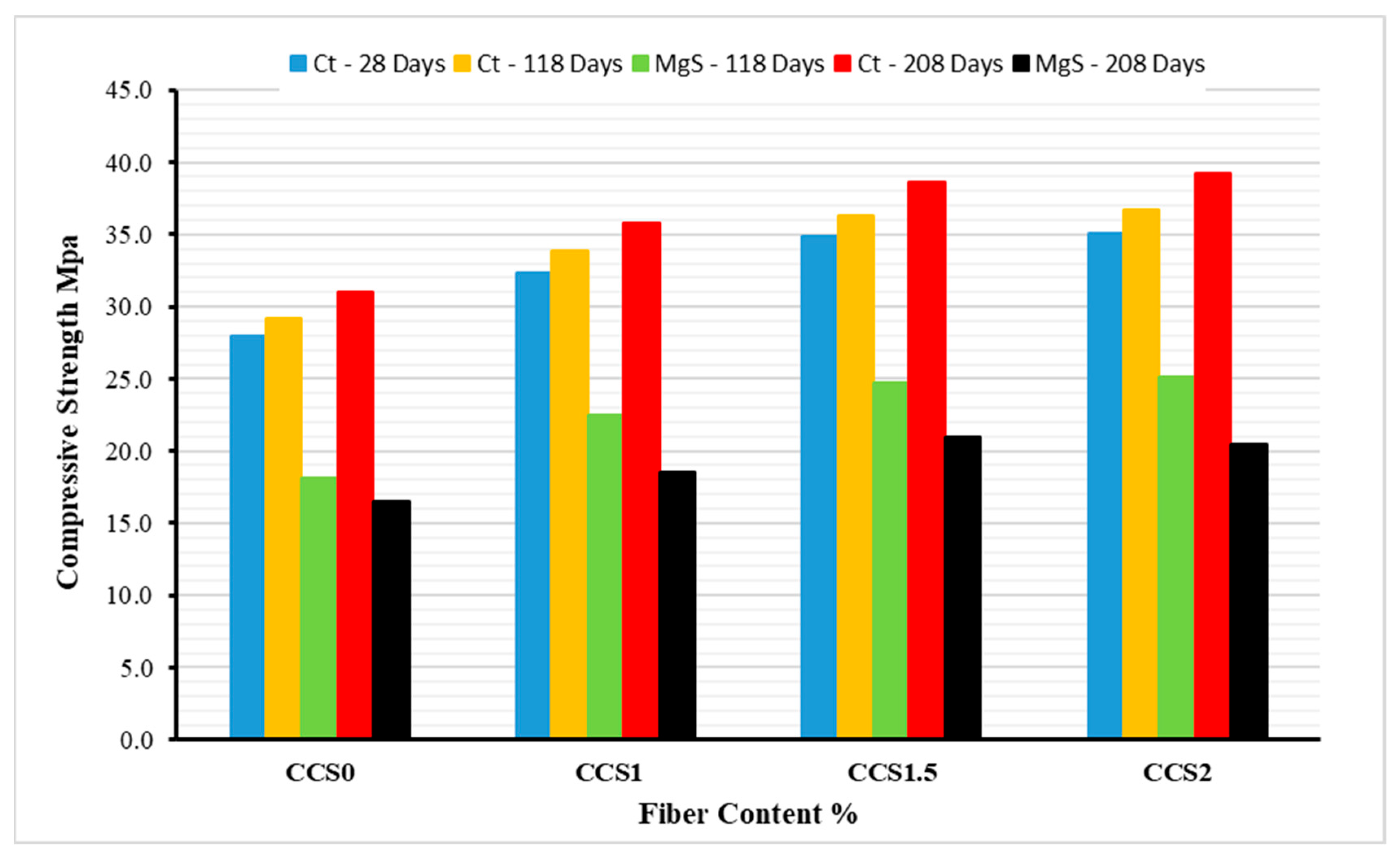

To assess the compressive strength of CCS, three cubic specimens for each mix were tested at different ages (28, 118, and 208 days). The average compressive strength of the CCS cubes is shown in

Figure 3. From

Figure 3, the compressive strength of CCS specimens after 90 days of severe sulfate exposure ranged from 18 MPa to 25 MPa, and 16 MPa to 20 MPa after 180 days of exposure. Compared to the compressive strength at 28 days, the strength of the CCS specimens exhibited a decline of 35%, 30%, 29%, and 28% for CCS0-S, CCS1-S, CCS1.5-S, and CCS2-S respectively, after 3 months of exposure to severe magnesium sulfate attack. These results suggest that the addition of fibers slightly improved compressive strength due to their role in enhancing the bond between the UHPFRC and NSC layers. However, after 6 months of sulfate exposure, this beneficial effect diminished, likely due to the formation of deleterious reaction products that weakened the interface between the two concrete layers, as previously reported by Balouch et al. (2010). The reductions in compressive strength after 6 months of exposure to severe magnesium sulfate attack were 41%, 42%, 40%, and 41% for CCS0-S, CCS1-S, CCS1.5-S, and CCS2-S, respectively. These results indicate that fiber content had minimal impact on mitigating compressive strength loss, as the reductions were comparable across all specimens.

Comparing the outcomes between the control medium (freshwater) and magnesium sulfate for the same age bracket, the compressive strength displayed declines of 37.8 %, 33.4%, 31.7%, and 31.6% at 118 days, and 46.9%, 48.1%, 45.7%, and 47.9% at 208 days, for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2 respectively.

These results demonstrate that the severe sulfate attack significantly compromised compressive strength after approximately 3 months of exposure, even in specimens containing UHPFRC layers. The primary cause of this strength deterioration is likely the progressive degradation of the NSC layer, as the continued formation of sulfate-induced reaction products resulted in internal damage within the NSC matrix, loss of mechanical integrity at the interface between NSC and UHPFRC, and weakened bond strength due to microstructural disruption.

The data suggests that while UHPFRC enhances the initial strength and bond properties, it does not entirely prevent compressive strength deterioration under prolonged sulfate exposure. The NSC layer remains vulnerable, and its degradation significantly influences the overall performance of the CCS composite members.

Figure 1. This is a figure.

Schemes follow the same formatting.

3.3. Flexural Behavior

3.3.1. Crack and Failure Mode

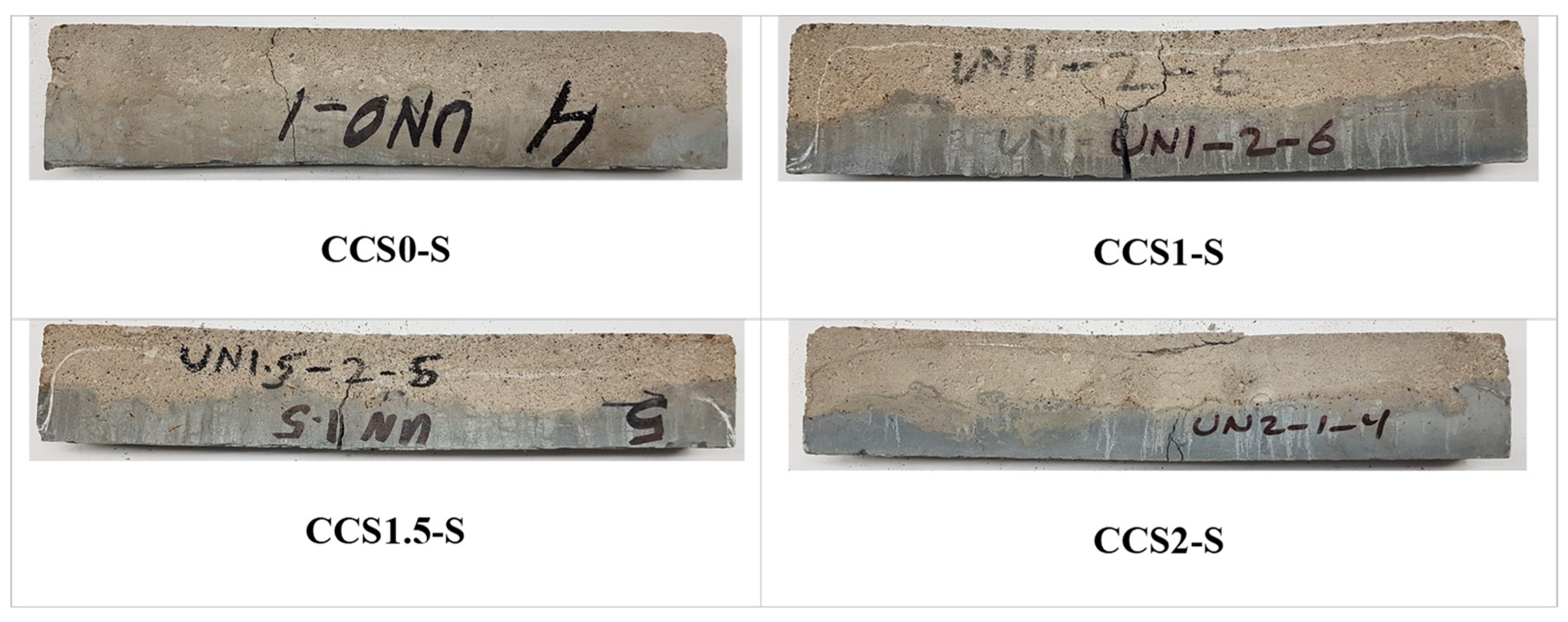

The crack patterns of the CCS members are illustrated in

Figure 4. All the CCS specimens failed in flexure, exhibiting a dominant crack near the center of the beam, except for the CCS0-S specimen, where the primary crack deviated away from the center. The failure mode varied depending on the fiber content; specimen CCS0 exhibited brittle failure, with the specimen fracturing soon after the initial crack formed, while the other specimens incorporating fibers (CCS1-S, CCS1.5-S, and CCS2-S) displayed more ductile behavior, indicating enhanced resistance to crack propagation and improved energy absorption. An additional observation from

Figure 4 is the contrast in surface texture between the two layers, the NSC layer developed a rough porous surface, suggesting increased degradation due to sulfate exposure. In contrast, the UHPC layer retained a smoother surface, indicating higher resistance to sulfate-induced deterioration.

These findings suggest that fiber reinforcement in the UHPFRC layer is crucial in enhancing ductility and mitigating premature failure under flexural loading.

3.3.2. Flexural strength

The peak load (

Pp) and corresponding deflection (Δ

p) for CCS specimens at 28, 118, and 208 days are summarized in

Table 3. At 118 days, when comparing specimens exposed to severe magnesium sulfate attack with their respective control specimen, the peak load decreased by 15%, 12%, 9%, and 8% for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2, respectively. After 180 days of sulfate exposure, these reductions increased to 29%, 17%, 13%, and 11% for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2, respectively. These results demonstrate that higher fiber content mitigated the reduction in flexural strength, as fibers:

The impact of prolonged sulfate exposure was more pronounced in CCS0 specimens (without fibers), where the flexural capacity decreased by 17% from 90 days to 180 days. In contrast, CCS2 specimens exhibited only a 3% reduction, indicating that a fiber volume content of at least 1.5% is necessary to counteract sulfate-induced degradation significantly.

Comparing specimens exposed to severe sulfate attack with their freshwater control counterparts at the same age, the peak load reductions were observed. At 118 dayes, showed decrements of 20%, 19%, 11%, and 9%, and at 208 days 35%, 25%, 21%, and 18% for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2, respectively. These results highlight the significant deterioration in the NSC layer due to sulfate-induced reaction product formation, which weakened the mechanical bond between NSC and UHPFRC layers. Despite this degradation, specimens containing steel fibers maintained load-carrying capacity after crack initiation, demonstrating the resilience of the composite system under flexural loading.

In terms of ductility and deformation characteristics, the CCS composite system retained ductile behavior even after prolonged sulfate exposure. However, sulfate attack had a greater impact on deformation than on peak load capacity. The deflection reductions after 90 days were 30%, 24%, 18%, and 17%, and deflection reductions after 180 days were 29%, 25%, 19%, and 17% for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CSS2, respectively. This suggests that sulfate attacks have a more pronounced impact on deformation than on peak load. For example, at 90 days, peak load reductions for CCS0 and CCS2 specimens were 20% and 9%, while deflection reductions were more significant, at 30% and 17%, respectively. This aligns with findings from Liu et al. (2012), which suggest that sulfate attack has a more pronounced effect on deformation behavior than peak load capacity. Also, it can be noted that with exposure time increased from 90 days to 180 days, the peak load further decreased to 35% for CCS0-S and 18% for CCS2-S, whereas deflection remained stable, indicating that the structural integrity of fiber-reinforced specimens was maintained despite sulfate exposure.

These results confirm that fiber-reinforced CCS specimens exhibited superior performance in maintaining flexural strength and ductility under sulfate attack. While low fiber content (1%) provided limited protection, higher fiber contents (≥1.5%) effectively offset sulfate-induced degradation by improving tensile strength and enhancing the mechanical interaction between NSC and UHPFRC layers.

3.3.3. Load-Deflection Response

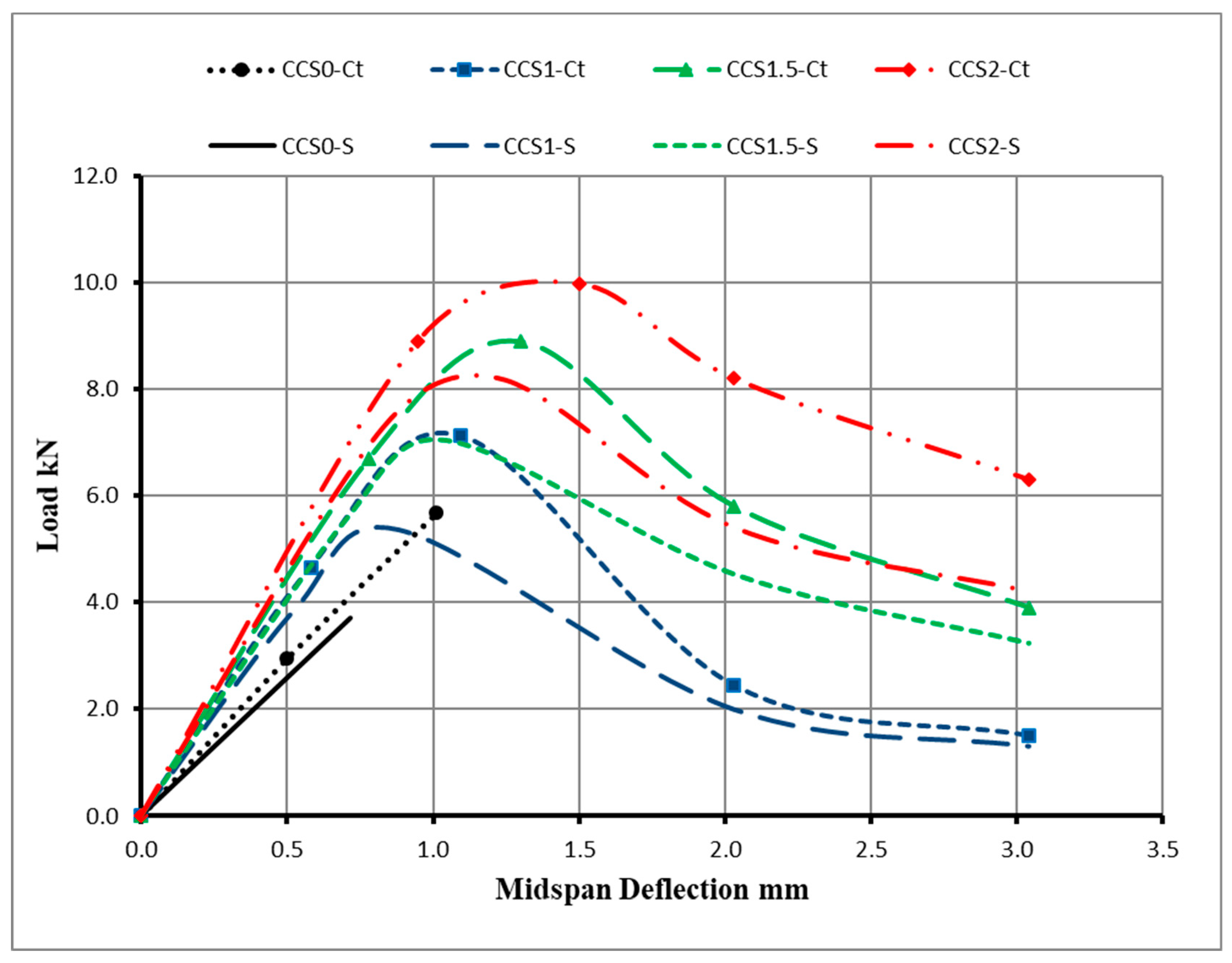

The load-deflection behavior of CCS specimens exposed to a very severe sulfate environment for 208 days is shown in

Figure 5. The curves represent the average response of three tested specimens and can be divided into three distinct phases. In the elastic phase (pre-cracking stage), before the formation of the first visible crack, the load-deflection curves exhibit a linear relationship, where the deflection is proportional to the applied load. This linearity was observed across all fiber contents, regardless of sulfate exposure, as shown in

Figure 5. In the nonlinear phase (post-cracking load redistribution), upon crack initiation, the response becomes nonlinear, and fiber-reinforced specimens (CCS1-S, CCS1.5-S, and CCS2-S) continued to carry the applied load, the steel fibers transfered the stresses across the crack width, enhancing post-cracking load capacity. In the final softening phase (failure stage), the applied load decreases while the deflection continues to increase. At this stage, fibers were pulled out from the matrix, loosing their ability to bridge the cracks. The severe sulfate attack significantly impacted this phase, particularly in specimens with higher fiber content, leading to a reduction in residual strength.

In terms of the first cracking load and initial stiffness, the first cracking load (

Pcr), corresponding deflection (Δ

cr), and initial stiffness (K

ini) at 28, 118, and 208 days are summarized in

Table 4. The initial stiffness was determined from the slop of the load – mid-span deflections curve in the pre-cracking stage. Results indicate that all CCS specimens exhibited deflection-hardening behavior, except for CCS0, which failed in a brittle mode. It can be noticed from

Table 3 and

Table 4 that it was higher than

Pcr for all CCS specimens except CCS0, where the member failed in a brittle mode which indicates deflection hardening behavior. Compared to control specimens, the reductions

Pcr were 22.7%, 18.2%, 17.1%, and 16.3% for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CC2. These results suggest that the presence of fibers significantly delayed the crack propagation and improved the resistance to severe sulfate attack

Pcr when the fiber volume content increased from 0% to 1%; however, increasing the fiber content from 1% to 2% slightly improved the resistance to sever sulfate attack at

Pcr.

Effect of Sulfate Attack on Initial Stiffness: The initial stiffness of control specimens (CCS-Ct) slightly increases with time, whereas sulfate-exposed specimens exhibited a gradual reduction. Reduction in initial stiffness after 90 days of sulfate exposure (compared to 28-day control specimens) were 8.1%, 3.3%, 1.9%, and 1.5 % for specimens with 0%, 1%, 1.5%, and 2% fiber content, as shown in

Table 4. Reduction in initial stiffness after 180 days of sulfate exposure (compared to 28-day control specimens): were 10.5%, 8.4%, 6.7%, and 5.2 % for specimens with 0%, 1%, 1.5%, and 2% fiber content. It is evident that immersion in sulfate solution slightly reduced initial stiffness, likely due to the formation and propagation of microcracks at the bond interface caused by sulfate-induced reaction products. However, the reduction in stiffness was mitigated by higher fiber content, as steel fibers helped retard microcrack initiation and propagation.

Comparing the results of initial stiffness with those of control medium at the same age, the initial stiffness showed a decrement of 8.4%, 4.5%, 3.1%, and 2.1% after 90 days of exposure to magnesium sulfate attack, and 12.2%, 10.1%, 7.6% and 5.3% after 180 days of exposure to magnesium sulfate attack for CCS0, CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2 respectively.

These results indicate that sulfate exposure had a more pronounced impact on stiffness at early ages, likely due to ettringite and calcium sulfate formation, which temporarily filled microcracks and pores, slowing degradation. However, as exposure time increased, the continued expansion of reaction products led to the growth of microcracks, causing a substantial decline in stiffness.

These findings are consistent with Liu et al. (2012), who also reported that sulfate attack influences both static and dynamic properties of concrete over time.

3.3.4. Energy absorption capacity

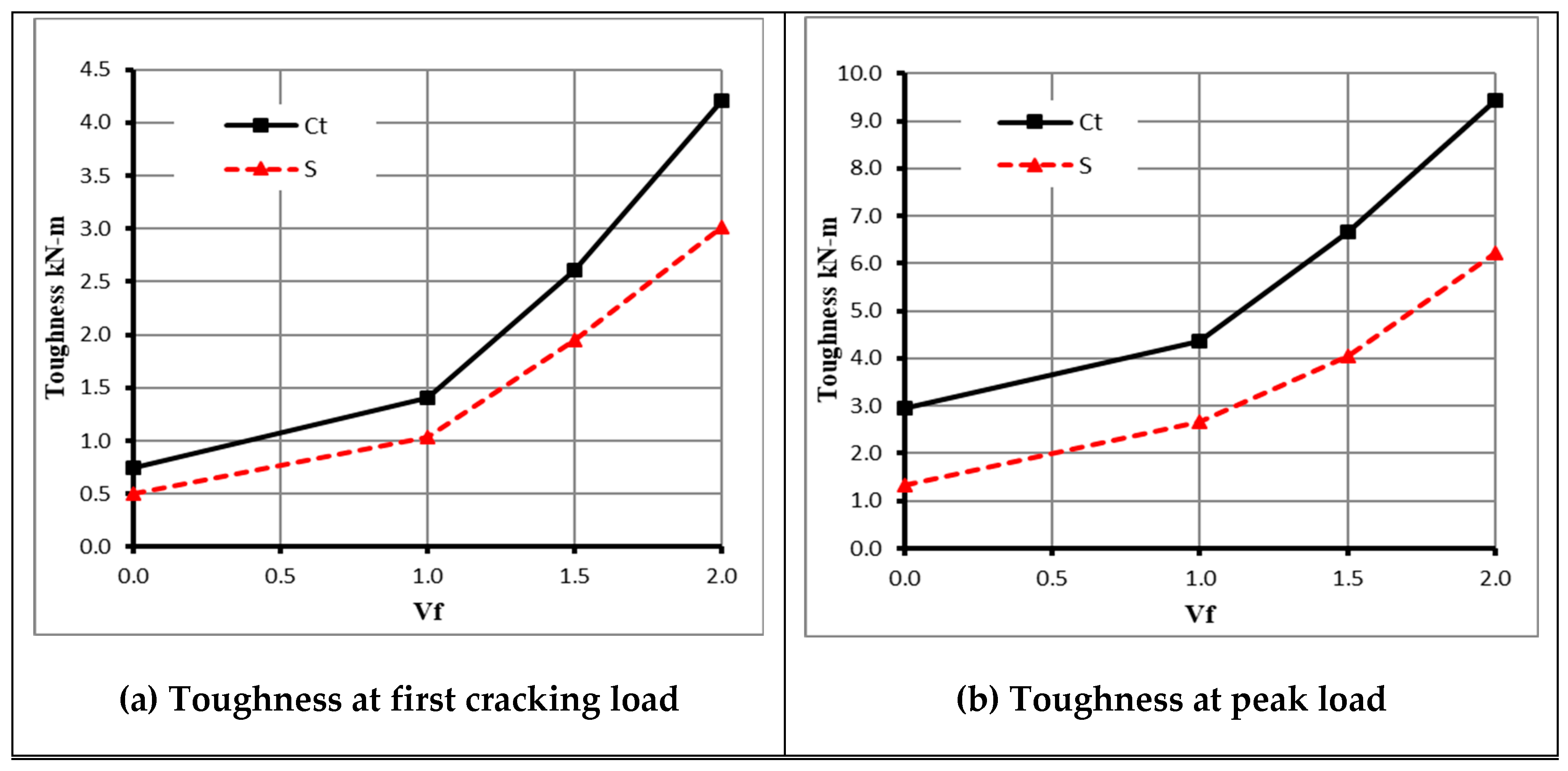

The energy absorption capacity of concrete prisms was determined by calculating the area under the load-deflection curves presented in

Figure 5.

Figure 6 shows the impact of sulfate attack and fiber reinforcement on the energy absorption capacity calculated at first cracking and peak load points. At the first cracking load, the energy absorption capacity of the CCS0 specimen decreased by 32.4% due to severe sulfate attack. This reduction was mitigated in fiber-reinforced specimens, with decrements of: 28.3%, 26.4%, 25.2% for CCS1, CCS1.5 and CCS2 specimens, respectively. Adding 1% of steel fibers slightly improved the toughness, while increasing the fiber content to 2% resulted in a negligible effect on energy absorption capacity. At the peak load point, the energy absorption capacity decreased by 54.8% for the CCS0 specimen compared to the control specimen. However, this reduction was significantly reduced for fiber-reinforced specimens to 39.1%, 38.9%, and 33.9% for CCS1, CCS1.5, and CCS2 specimens, respectively.

These results highlight that fiber reinforcement enhances energy absorption capacity, particularly at higher load levels, by improving post-cracking performance and delaying failure under sulfate exposure. However, increasing fiber content beyond 1.5% provided only marginal benefits, suggesting that optimal fiber dosage should be considered to balance mechanical performance and material efficiency.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the effects of a severe sulfate attack (10% magnesium sulfate solution) combined with drying-wetting cycles on the mechanical and microstructural behavior of composite concrete systems (CCS) consisting of UHPFRC and NSC layers. Based on the experimental findings, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Mass Loss Behavior: Sulfate attack significantly affected specimen mass. Over the first 120 days, the mass of all specimens increased progressively. However, after 120 days, the mass of CCS0 (without fibers) declined sharply, while fiber-reinforced specimens exhibited only slight reductions, demonstrating the stabilizing effect of fibers in mitigating sulfate-induced degradation.

Compressive Strength Reduction: After six months of sulfate exposure, the compressive strength decreased by approximately 40%, regardless of fiber volume content, indicating that fiber reinforcement had no significant impact on compressive strength retention under prolonged sulfate attack.

Flexural Strength Reduction: The flexural strength of CCS specimens decreased by 17% and 11% after 180 days of sulfate exposure for specimens containing 1% and 2% fibers, respectively. This confirms that fibers play a critical role in maintaining flexural capacity under aggressive sulfate conditions.

Energy Absorption and Toughness: The presence of fibers mitigated the effects of sulfate attack, particularly after crack initiation. While adding 1% fibers improved toughness, further increasing the fiber content to 2% had a negligible additional effect on energy absorption capacity, suggesting a threshold beyond which additional fibers provide minimal benefit.

These findings highlight the importance of fiber reinforcement in enhancing sulfate resistance, particularly in flexural and post-cracking performance. However, their impact on compressive strength was limited, and excessive fiber content did not significantly improve durability under sulfate exposure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A. and L.H.; methodology, L.H.; experimental design, LH; formal analysis, L.H.; investigation, L.A.; resources, L.A. and L.H.; data curation, L.H, and L.A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A., and L.H.; writing—review and editing, L.A.; visualization, L.A.; supervision, L.A.; project administration, L.A.; funding acquisition, L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the TMU Dean’s Research Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. However, additional data can be provided upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbas, S.; Nehdi, M.L.; Saleem, M.A. Ultrahigh-performance concrete: Mechanical performance, durability, sustainability, and implementation challenges. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2017, 10, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaee, F.J.; Karihaloo, B.L. Retrofitting of reinforced concrete beams with CARDIFRC. J. Compos. Constr. 2003, 7, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, W.L.; Siad, H.; Lachemi, M.; Sahmaran, M. A review on the durability of concrete-to-concrete bond in recent rehabilitated structures. J. Build. Eng. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouch, S.U.; Forth, J.P.; Granju, J.L. Surface corrosion of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien-Masse, M.; Brühwiler, E. Experimental investigation on punching resistance of R-UHPFRC–RC composite slabs. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L.; Elsener, B.; Pedeferri, P.; Polder, R. Corrosion of Steel in Concrete, Prevention, Diagnosis, Repair; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2004.

- Beschi, C.; Meda, A.; Riva, P. Beam-column joint retrofitting with high-performance fiber reinforced concrete jacketing. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2011, 82, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broomfield, J. Corrosion of Steel in Concrete: Understanding, Investigation, and Repair; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Shui, Z.; Gao, X.; Lu, J.; Sun, T.; Yu, R. Degradation progress of Portland cement mortar under the coupled effects of multiple corrosive ions and drying-wetting cycles. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 111, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Shui, Z.; Gao, X.; Yu, R.; Sun, T.; Guo, C.; Huang, Y. Degradation mechanisms of Portland cement mortar under seawater attack and drying-wetting cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 116934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunxiang, Q.; Patnaikuni, I. Properties of high-strength steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams in bending. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1999, 21, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancygier, A.N.; Savir, Z. Flexural behavior of HSFRC with low reinforcement ratios. Eng. Struct. 2006, 28, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Larrard, F.; Sedran, T. Optimization of ultrahigh-performance concrete using a packing model. Cem. Concr. Res. 1994, 24, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.M.; Elyamany, H.E.; Abd Elmoaty, A.E.M. Effect of nanomaterials additives on performance of concrete resistance against magnesium sulfate and acids. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 210, 210–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, F.A.; Nicolaides, D.; Kanelopoulos, A.; Karihaloo, B.L. High-performance fiber reinforced cementitious composite (CARDIFRC) – Performance and application to retrofitting. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2007, 74, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollop, R.S.; Taylor, H.F.W. Microstructural and microanalytical studies of sulfate attack III. Sulfate-resisting Portland cement: Reactions with sodium and magnesium sulfate solutions. Cem. Concr. Res. 1995, 25, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golop, P.; Taylor, H.F.W. The resistance of cement products to magnesium salts. Cem. Concr. Res. 1995, 25, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Graybeal, B.A.; Tanesi, J. Durability of an ultra-high-performance concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2007, 19, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, K.; Denarié, E.; Brühwiler, E. Structural response of elements combining ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concretes and reinforced concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 2006, 132, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, K.; Viviani, M.; Denarié, E.; Brühwiler, E. Development of the mechanical properties of an ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete (UHPFRC). Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Mahmud, H.B.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Alsubari, B. Effect of magnesium sulfate on self-compacting concrete containing supplementary cementitious materials. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.M.T.; Jones, S.W.; Mahmud, G.H. Experimental test methods to determine the uniaxial tensile and compressive behavior of ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete (UHPFRC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, L. Structural Behavior of Ultrahigh Performance Fiber Reinforced Composite Members; Ph.D. Thesis, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, L.; Amleh, L. Assessment of ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete–normal-strength concrete or high-strength concrete composite members in chloride environment. CSCE Int. Conf. Resilient Infrastruct. 2016, MAT-763-1–8.

- Hussein, L.; Amleh, L. Structural behavior of ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete–normal-strength concrete or high-strength concrete composite members. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, L.; Amleh, L.; Siad, H.; Lachemi, M. Effect of severe chloride environment on the flexural behavior of hybrid concrete systems. Mag. Concr. Res. 2020, 72, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, A.A.; Pradhan, B. Effect of magnesium sulfate in chloride solution on variation in microstructure, chloride diffusion, and chloride-binding behavior of concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Niu, D. Study of deterioration of concrete exposed to different types of sulfate solutions under drying-wetting cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 117, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-T.; Lee, Y.; Park, Y.-D.; Kim, J.-K. Tensile fracture properties of an ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete (UHPFRC) with steel fiber. Compos. Struct. 2010, 92, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Abbass, W. Flexural behavior of high-strength concrete beams reinforced with a strain-hardening cement-based composite layer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawardaningsih, Y.; Fehling, E.; Ismail, M.; Aboubakr, A.A.M. Tensile strength behavior of UHPC and UHPFRC. Procedia Eng. 2015, 125, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, A.; Paschalis, S.; Tsioulou, O.; Dritsos, S. Strengthening of reinforced concrete beams using ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete (UHPFRC). Eng. Struct. 2016, 106, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, Z.; Hu, L. Interfacial microstructure between ultrahigh-performance concrete–normal concrete in fresh-on-fresh casting. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zou, D.; Teng, J.; Yan, G. The influence of sulfate attack on the dynamic properties of the concrete column. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinola, G.; Meda, A.; Plizzari, G.A.; Rinaldi, Z. Strengthening and repair of RC beams with fiber-reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofinejad, D.; Nosouhian, F.; Nazari-Monfared, H. Influence of magnesium sulphate concentration on durability of concrete containing micro-silica, slag, and limestone powder using durability index. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 117, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavinezhad, S.; Toledo, W.K.; Newtson, C.M.; Aguayo, F. Rapid assessment of sulfate resistance in mortar and concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noshiravani, T.; Brühwiler, E. Analytical model for predicting response and flexure-shear resistance of composite beams combining reinforced ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete and reinforced concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 2014, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kim, D.J.; Ryu, G.S.; Koh, K.T. Tensile behavior of ultrahigh-performance hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, S.; El-Tawil, S.; Naaman, A.E. Direct tensile behavior of ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete (UHP-FRC) at high strain rates. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 88, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.G.K.; Ramadoss, P. Flexural behavior of ultrahigh-performance steel fiber-reinforced concrete: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. Res. 2017, 4, 2394–3386. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, G.M.; Wu, H.; Fang, Q.; Liu, J.Z. Effects of steel fiber content and type on static mechanical properties of UHPCC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 163, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Arca, A.; Parant, E.; Fakhri, P. Bending and compressive behaviors of a new cement composite. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannag, M.J.M.; Shaia, H. Sulfate resistance of high-performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Siad, H.; Lachemi, M.; Bernard, S.K.; Sahmaran, M.; Hossain, A. Assessment of the long-term performance of SCC incorporating different mineral admixtures in a magnesium sulfate environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 80, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sheikh, A.H.; Mohamed Ali, M.S.; Visintin, P.; Griffith, M.C. Experimental and numerical study of the flexural behavior of ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 138, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Shi, C.; He, W.; Wu, L. Effects of steel fiber content and shape on mechanical properties of ultrahigh-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 103, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, Ç. A preliminary study on the development of the normal concrete-UHPC composite beam via wet casting. J. Struct. Eng. Appl. Mech. 2021, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.H.; Joh, C.; Bui, T.Q. Estimating the tensile strength of ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete beams. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5128029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Yu, M.; Lu, Y.; Liu, S. Mechanism and performance control methods of sulfate attack on concrete: A review. Materials 2024, 17, 4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; He, W.; Zhou, X. Study on the resistance of concrete to high-concentration sulfate attack: A case study in Jinyan Bridge. Materials 2024, 17, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Al-Samawi, M.; Al-Shakhdha, N.A.; Farouk, A.I.B.; Liu, Z. Experimental investigation on compressive and flexural behavior of composite concrete systems incorporating UHPC under chloride-sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).