Submitted:

10 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

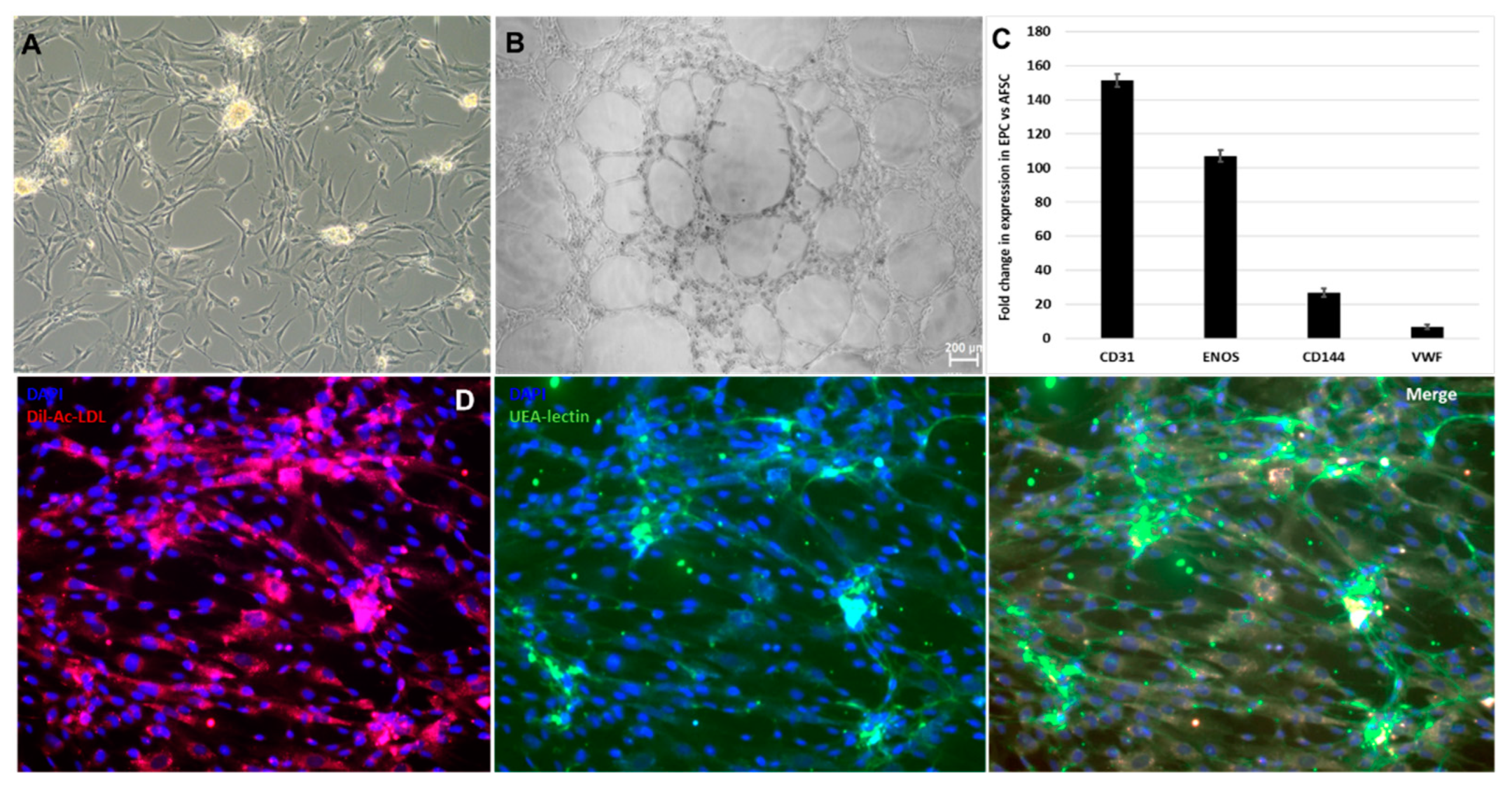

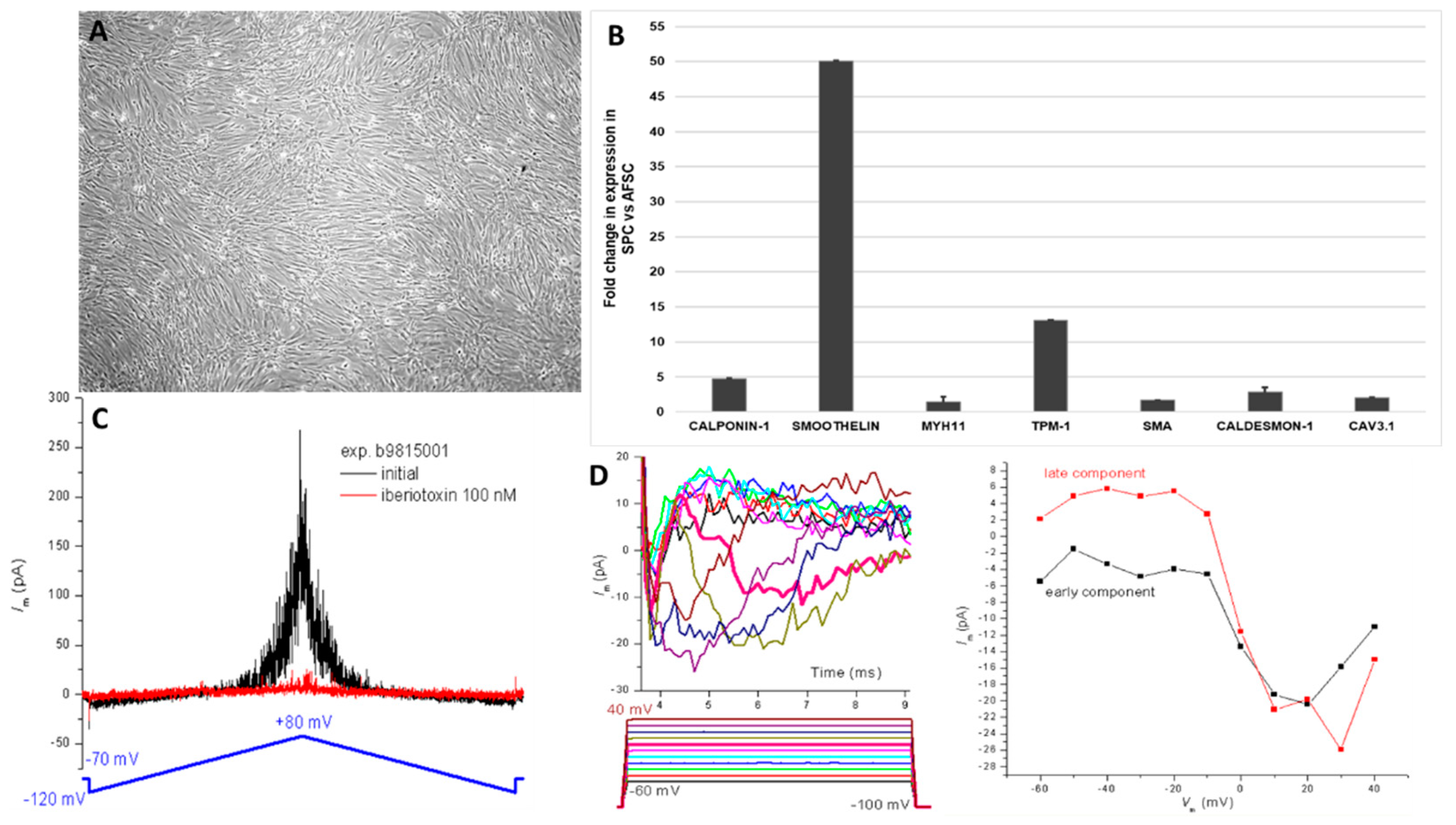

2.1. AFSC differentiated in endothelial and smooth muscle progenitor cells

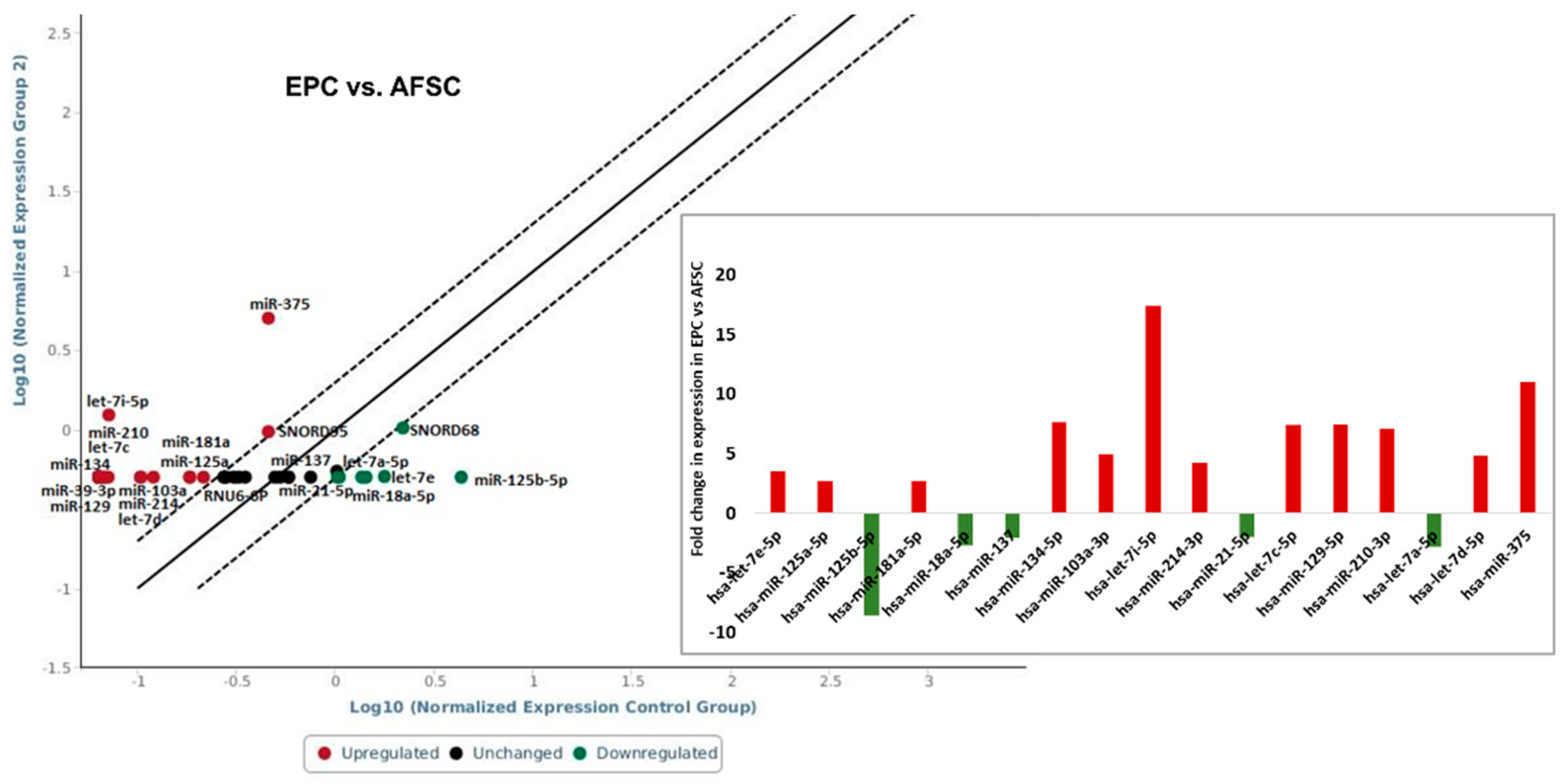

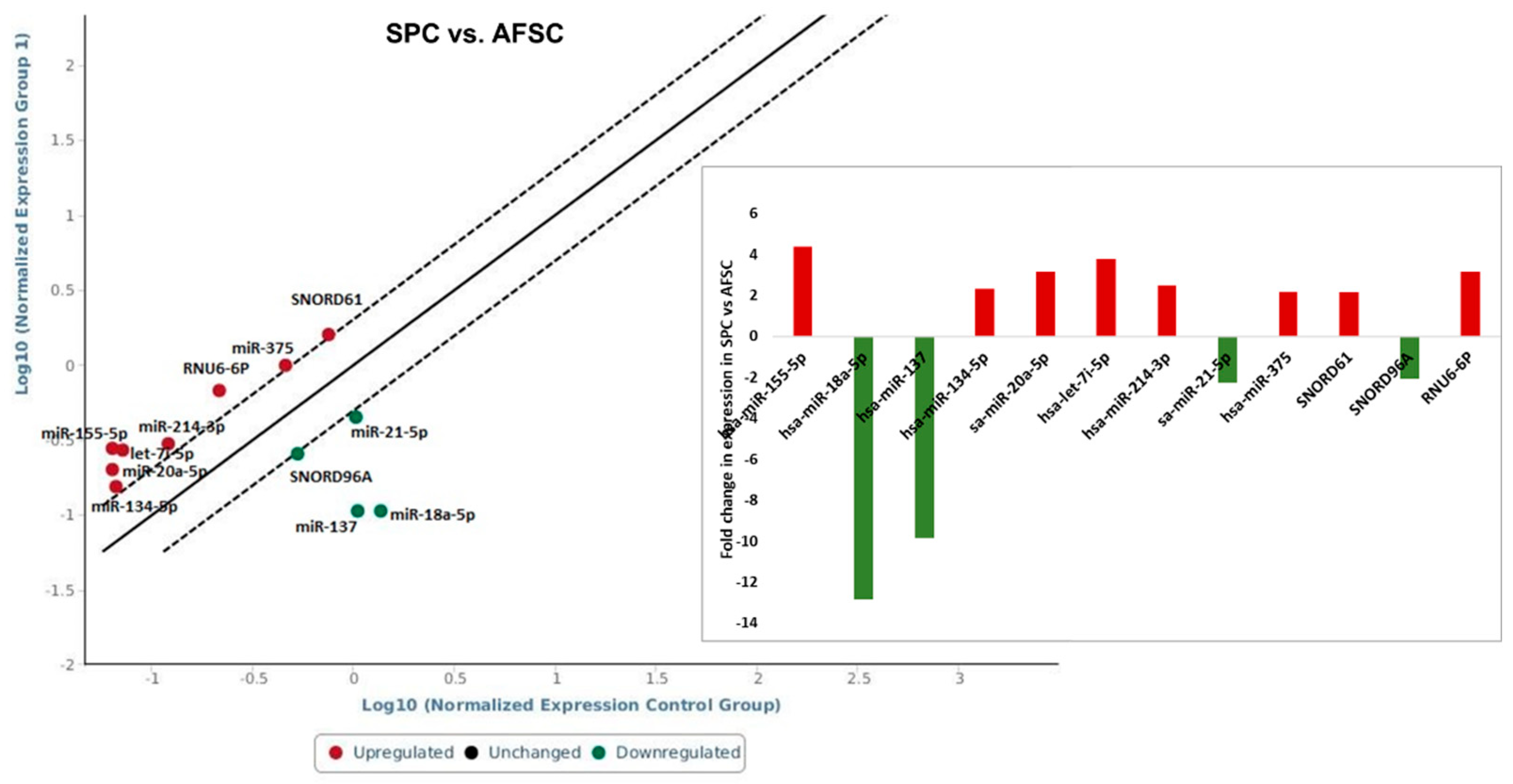

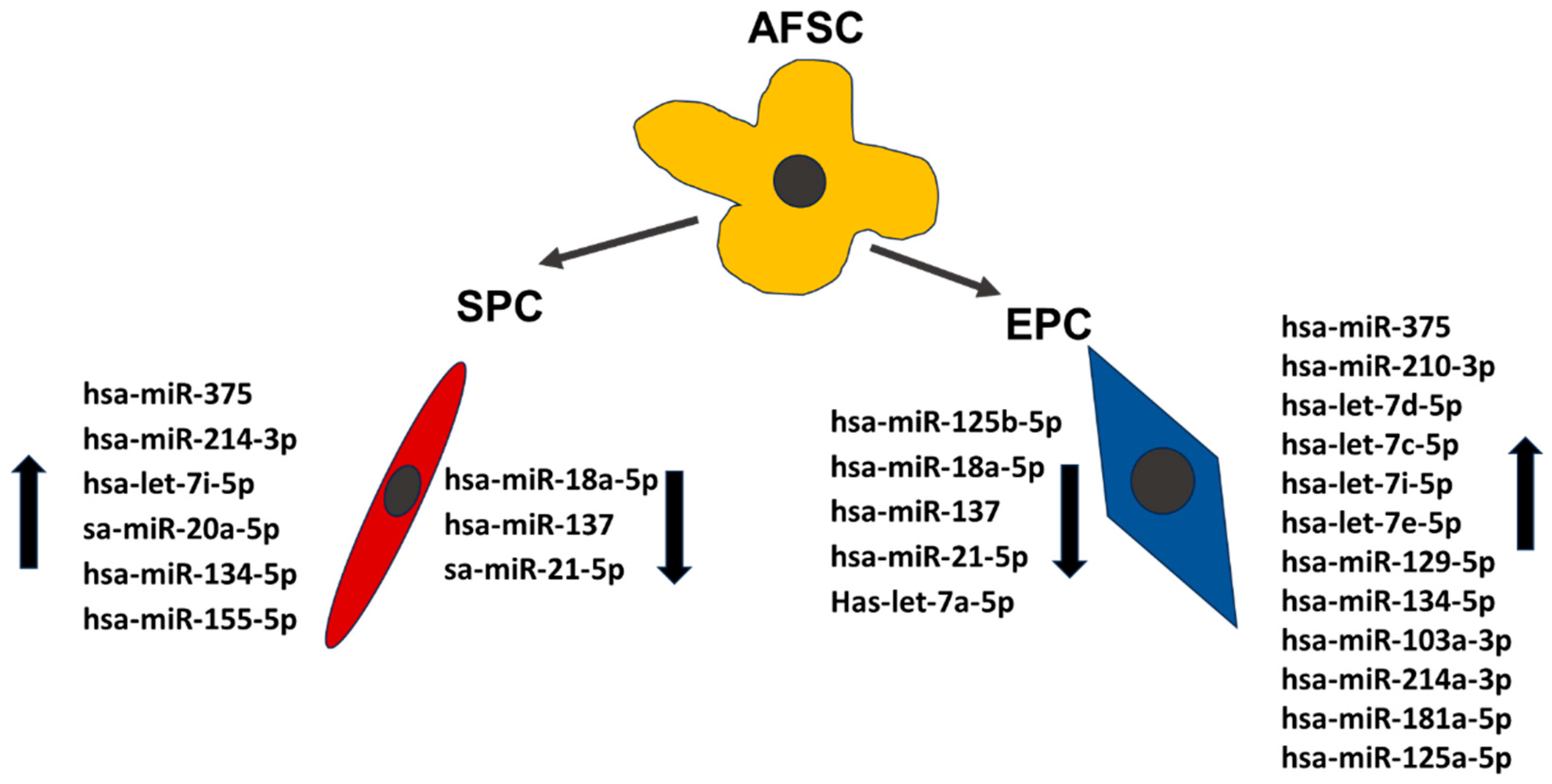

2.2. miRNA regulates the differentiation of AFSC

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Amniotic fluid stem cells differentiation and characterization

4.2. Gene expression and functional characterization of EPC

4.3. Gene expression assays on smooth muscle progenitor cells (SPC)

4.4. Patch-clamp assays on smooth muscle progenitor cells (SPC)

4.5. miRNA expression

4.6. Data analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loukogeorgakis, S.P.; De Coppi, P. Concise Review: Amniotic Fluid Stem Cells: The Known, the Unknown, and Potential Regenerative Medicine Applications. Stem Cells. 2017, 35(7), 1663-1673. [CrossRef]

- Cananzi, M.; De Coppi, P. CD117(+) amniotic fluid stem cells: state of the art and future perspectives. Organogenesis. 2012, 8(3), 77-88. [CrossRef]

- Resca, E.; Zavatti, M.; Maraldi, T.; Bertoni, L.; Beretti, F.; Guida, M.; La Sala, G.B.; Guillot, P.V.; David, A.L.; Sebire, N.J.; De Pol, A.; De Coppi, P. Enrichment in c-Kit improved differentiation potential of amniotic membrane progenitor/stem cells. Placenta. 2015, 36(1), 18-26. [CrossRef]

- De Coppi, P.; Bartsch, G.Jr.; Siddiqui, M.M.; Xu, T.; Santos, C.C.; Perin, L.; Mostoslavsky, G.; Serre, A.C.; Snyder, E.Y.; Yoo, J.J.; Furth, M.E.; Soker, S.; Atala, A. Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2007, 25(1), 100-6. [CrossRef]

- Shamsnajafabadi, H.; Soheili, Z.S. Amniotic fluid characteristics and its application in stem cell therapy: A review. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2022, 20(8), 627-643. [CrossRef]

- Cananzi, M.; Atala, A.; De Coppi, P. Stem cells derived from amniotic fluid: new potentials in regenerative medicine. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009, 18, 17-27. [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, A.; D’Amico, M.A.; Izzicupo, P.; Gaggi, G.; Guarnieri, S.; Mariggiò, M.A.; Antonucci, I.; Corneo, B.; Sirabella, D.; Stuppia, L.; Ghinassi, B. Cardiomyocytes derived from human cardiopoietic amniotic fluids. Sci Rep. 2018, 8(1), 12028. [CrossRef]

- Di Tizio, D.; Di Serafino, A.; Upadhyaya, P.; Sorino, L.; Stuppia, L.; Antonucci, I. The impact of epigenetic signatures on amniotic fluid stem cell fate. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 4274518. [CrossRef]

- Condorelli, G.; Latronico, M.V.; Cavarretta, E. microRNAs in cardiovascular diseases: current knowledge and the road ahead. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014, 63(21), 2177-87. [CrossRef]

- Milcu, A.I.; Anghel, A.; Muşat, O.; Munteanu, M.; Salavat, M.C.; Iordache, A.; Ungureanu, E.; Bonţe, D.C.; Borugă, O. Implications at the ocular level of miRNAs modifications induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2022, 63(1), 55-59. [CrossRef]

- Trohatou, O.; Zagoura, D.; Bitsika V.; Pappa, K.I.; Antsaklis, A.; Anagnou, N.P.; Roubelakis, M.G. Sox2 suppression by miR-21 governs human mesenchymal stem cell properties. Stem Cells Translational Medicine, 2014, 3, 1, 54–68. [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, R.; Olivieri, F.; Ferretti, C.; Mattioli-Belmonte, M.; di Primio, R.; Orciani, M. mRNAs and miRNAs profiling of mesenchymal stem cells derived from amniotic fluid and skin: the double face of the coin. Cell and Tissue Research, 2014, 355, 1, 121–130. [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh-Ghaleh Aziz, S.; Pashaei-Asl, F.; Fardyazar, Z.; Pashaiasl, M. Isolation, characterization, cryopreservation of human amniotic stem cells and differentiation to osteogenic and adipogenic cells. PLoS One, 2016, vol. 11, no. 7, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Glemžaitė, M.; Navakauskienė, R. Osteogenic differentiation of human amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells is determined by epigenetic changes. Stem Cells International, 2016, 2016, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, R.; Sorgentoni, G.; Caffarini, M.; Sayeed, M.A.; Olivieri, F.; Di Primio, R.; Orciani, M. New miRNAs network in human mesenchymal stem cells derived from skin and amniotic fluid. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016, 29(3), 523-528. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Sayago, J.M.; Fernandez-Arcas, N.; Reyes-Engel, A.; Benito, C..; Narbona, I.; Alonso, A. Changes in CDKN 2 D, TP 53, and mi R 125a expression: potential role in the evaluation of human amniotic fluid-derived mesenchymal stromal cell fitness. Genes to Cells, 2012, 17(8), 673-687. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Furusawa, C.; Kaneko, K. Pluripotency, differentiation, and reprogramming: A gene expression dynamics model with epigenetic feedback regulation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015, 11(8), e1004476. [CrossRef]

- Bem, J.; Grabowska, I.; Daniszewski, M.; Zawada, D.; Czerwinska, A.M.; Bugajski, L.; Piwocka, K.; Fogtman, A.; Ciemerych, M.A. Transient microRNA expression enhances myogenic potential of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2018, 36(5), 655-670. [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Pirouz, M.; Choi, J.; Huebner, A.J.; Clement, K.; Meissner, A.; Hochedlinger, K.; Gregory, R.I. An intermediate pluripotent state controlled by micrornas is required for the naive-to-primed stem cell transition. Cell Stem Cell. 2018, 22(6), 851-864.e5. [CrossRef]

- Che, P.; Liu, J.; Shan, Z.; Wu, R.; Yao, C.; Cui, J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Burnett, M.S.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. miR-125a-5p impairs endothelial cell angiogenesis in aging mice via RTEF-1 downregulation. Aging Cell. 2014, 13(5), 926-934. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Ge, J.; Wang, Z.; Ren, J.; Wang, X.; Xiong, H.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Let-7e modulates the inflammatory response in vascular endothelial cells through ceRNA crosstalk. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 42498. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, M.; Yu, M.; Ping, F.; Wang, T.; Wang, X. Vildagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, attenuated endothelial dysfunction through miRNAs in diabetic rats. Arch Med Sci. 2019, 17(5), 1378-1387. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, Q.; Gong, K.; Long, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, X. Downregulation of miR-103a-3p contributes to endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction in deep vein thrombosis through PTEN targeting. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020, 64, 339-346. [CrossRef]

- Yamakuchi, M. Endothelial senescence and microRNA. Biomol Concepts. 2012, 3(3), 213-23. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Lei, Q.; Ma, J.; Ju, R. Effects of hypoxic-ischemic pre-treatment on microvesicles derived from endothelial progenitor cells. Exp Ther Med. 2020, 19(3), 2171-2178. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Flach, H.; Onizawa, M.; Wei, L.; McManusm M.T.; Weiss, A. Negative regulation of Hif1a expression and TH17 differentiation by the hypoxia-regulated microRNA miR-210. Nat Immunol. 2014, 15(4), 393-401. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, Z.; Zhao, X.; Xu, M.; Chen, M. Expression of miR-210 in the peripheral blood of patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and its effect on the number and function of endothelial progenitor cells. Microvasc Res. 2020, 131, 104032. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.H.; Han, X.Y.; Yao, M.D.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yan, B. Differential MicroRNA expression pattern in endothelial Progenitor cells during diabetic retinopathy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 773050. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, K.C.; Wu, W., Subramaniam, S.; Shy, J.Y.; Chiu, J.J.; Li, J.Y.; Chien, S. MicroRNA-21 targets peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-alpha in an autoregulatory loop to modulate flow-induced endothelial inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108:10355–10360. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, P.; Xiong, Q.; Song, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Yuan, W.; Rui, Y.C. MicroRNA-125a/b-5p inhibits endothelin-1 expression in vascular endothelial cells. J Hypertens. 2010, 28(8), 1646-1654. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.C.; Hsieh, I.C.; Hsi, E.; Wang, Y.S.; Dai, C.Y.; Chou, W.W; Juo, S.H. Negative feedback regulation between microRNA let-7g and the oxLDL receptor LOX-1. J Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 4115-4124. [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.H.; Zhang. Y.W.; Lou, X.Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, H.H. Protective effects of let-7a and let-7b on oxidized low-density lipoprotein induced endothelial cell injuries. PLoS One. 2014, 9(9):e106540. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, K.; Huang, W.; Zhang, X. MiR-137 inhibited cell proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells via targeting IGFBP-5 and modulating the mTOR/STAT3 signaling. PLoS One. 2017, 12(10), e0186245. [CrossRef]

- Kee, H.J.; Kim, G.R.; Cho, S.N.; Kwon, J.S.; Ahn, Y.; Kook, H.; Jeong, M.H. mir-18a-5p microrna increases vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation by downregulating syndecan4. Korean Circ J. 2014, 44(4), 255-563. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Zhou, M.H.; Li, S.P.; Zhao, H.M.; Zhang, Y.R.; Chen, D.; Wu, Y.X.; Pang, Q.F. MiR-155-5p attenuates vascular smooth muscle cell oxidative stress and migration via inhibiting BACH1 expression. Biomedicines 2023, 11(6), 1679. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Xing, W.; Li, J.; Du, R.; Cao, D.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhong, G.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, C.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jin, X.; Zhao, D.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Yuan, M.; Song, J.; Chang, Y.Z.; Gao, F.; Ling, S.; Li, Y. Vascular smooth muscle cell-specific miRNA-214 knockout inhibits angiotensin II-induced hypertension through upregulation of Smad7. FASEB J. 2021, 35(11):e21947. [CrossRef]

- Iordache, F.; Constantinescu, A.; Andrei, E.; Amuzescu, B.; Halitzchi, F.; Savu, L.; Maniu, H. Electrophysiology, immunophenotype, and gene expression characterization of senescent and cryopreserved human amniotic fluid stem cells. J Physiol Sci. 2016, 66(6), 463-476. [CrossRef]

- Airini, R.; Iordache, F.; Alexandru, D.; Savu, L.; Epureanu, F.B.; Mihailescu, D.; Amuzescu, B.; Maniu, H. Senescence-induced immunophenotype, gene expression and electrophysiology changes in human amniocytes. J Cell Mol Med. 2019, 23(11), 7233-7245. [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.A; Heide, J.; Knott, T.; Airini, R,; Epureanu, F.B.; Deftu, A.F.; Deftu, A.T.; Radu, B.M.; Amuzescu, B. Recording of multiple ion current components and action potentials in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes via automated patch-clamp. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2019, 100, 106599. [CrossRef]

- Scheel, O.; Frech, S.; Amuzescu, B.; Eisfeld, J.; Lin, K.H.; Knott, T. Action Potential Characterization of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Cardiomyocytes Using Automated Patch-Clamp Technology. ASSAY and Drug Development Technologies. 2014, 457-469. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).