Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

16 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Implications for Conservation and Management

REFERENCES

- Abban, E. K. 1999. Considerations for the conservation of African fish genetic resources for their sustainable exploitation. Towards policies for conservation and sustainable use of aquatic genetic resources. ICLARM Conf. Proc. 59, 277p, 95-100. Available from.

- Abiodun, J. A. 2002. Fisheries Statistical Bulletin Kainji Lake, Nigeria, 2001. Pp. 25p. Nigerian-German Kainji Lake Fisheries Promotion Project. Technical Report Series 18.

- Adite, A., K. O. Winemiller, and E. D. Fiogbe. 2006. Population structure and reproduction of the African bonytongue Heterotis niloticus in the Sô River-floodplain system (West Africa): implications for management. Ecology of Freshwater Fish 15:30-39. [CrossRef]

- Agbugui, M. O., H. O. Egbo, and F. E. Abhulimen. 2021. The Biology of the African Bonytongue Heterotis niloticus (Cuvier, 1829) from the Lower Niger River at Agenebode in Edo State, Nigeria. International Journal of Zoology 2021:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Akinsanya, B., I. O. Ayanda, A. O. Fadipe, B. Onwuka, and J. K. Saliu. 2020a. Heavy metals, parasitologic and oxidative stress biomarker investigations in Heterotis niloticus from Lekki Lagoon, Lagos, Nigeria. Toxicology Reports 7:1075-1082. [CrossRef]

- Akinsanya, B., I. O. Ayanda, B. Onwuka, and J. K. Saliu. 2020b. Bioaccumulation of BTEX and PAHs in Heterotis niloticus (Actinopterygii) from the Epe Lagoon, Lagos, Nigeria. Heliyon 6:e03272. [CrossRef]

- Allan, J. D., R. Abell, Z. E. B. Hogan, C. Revenga, B. W. Taylor, R. L. Welcomme, and K. Winemiller. 2005. Overfishing of inland waters. Bioscience 55:1041-1051. [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, F. W., G. H. Luikart, and S. N. Aitken. 2012. Conservation and the genetics of populations. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK.

- Arojojoye, O. A., A. A. Oyagbemi, O. E. Ola-Davies, R. O. Asaolu, Z. O. Shittu, and B. A. Hassan. 2021. Assessment of water quality of selected rivers in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria using biomarkers in Clarias gariepinus. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28:22936-22943. [CrossRef]

- Béné, C., and S. Heck. 2005. Fish and food security in Africa. NAGA, WorldFish Center Quarterly 28:8-13.

- Brummett, R., D. Nguenga, F. Tiotsop, and J.-C. Abina. 2010. The commercial fishery of the middle Nyong River, Cameroon: productivity and environmental threats.

- Chan, C. Y., N. Tran, S. Pethiyagoda, C. C. Crissman, T. B. Sulser, and M. J. Phillips. 2019. Prospects and challenges of fish for food security in Africa. Global Food Security 20:17-25. [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, G., and L. Garibaldi. 2015. The value of African fisheries. FAO fisheries and aquaculture circular 1093:1-76.

- Depierre, D., and J. Vivien. 1977. Une réussite du Service Forestier du Cameroun: l'introduction d'Heterotis niloticus dans le Nyong. Revue Bois et Forêts des Tropiques 173:59–68.

- Diouf, K., E. Akinyi, A. Azeroual, M. Entsua-Mensah, A. Getahun, P. Lalèyè, and T. H. Moelants. 2020. Heterotis niloticus. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T182580A134764025.en. . Accessed 05 November 2023.

- Do, C., R. S. Waples, D. Peel, G. M. Macbeth, B. J. Tillett, and J. R. Ovenden. 2014. NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne) from genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources 14:209-214. [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2003. Review of The State of World Fishery Resources: Inland Fisheries. FAO, Rome.

- FAO. 2021. Global capture production Quantity (1950–2021). https://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics-query/en/capture/capture_quantity. Accessed 05 Nov 2023.

- FAO. 2022. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation. Pp. 266. FAO, Rome. [CrossRef]

- Fish Laboratory. 2021. African Arowana (Heterotis niloticus): Ultimate Care Guide. https://www.fishlaboratory.com/fish/african-arowana/. Accessed 05 November 2023.

- Frankham, R. 2022. Evaluation of proposed genetic goals and targets for the Convention on Biological Diversity. Conservation Genetics 23:865-870. [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R., J. Ballou, and D. Briscoe. 2002. Introduction to Conservation Genetics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Frankham, R., J. D. Ballou, and D. A. Briscoe. 2010. Introduction to Conservation Genetics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Frankham, R., C. J. A. Bradshaw, and B. W. Brook. 2014. Genetics in conservation management: revised recommendations for the 50/500 rules, Red List criteria and population viability analyses. Biological Conservation 170:56-63. [CrossRef]

- Franklin, I. R. 1980. Conservation biology: an evolutionary-ecological perspective. Pp. 135–149 in M. E. Soulé and B. A. Wilcox, eds. Conservation biology: An evolutionary-ecological perspective. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Funge-Smith, S. J. 2018. Review of the state of world fishery resources: inland fisheries. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular.

- Funge-Smith, S., and A. Bennett. 2019. A fresh look at inland fisheries and their role in food security and livelihoods. Fish and Fisheries (Oxford) 20:1176-1195. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, K. J., and M. C. Whitlock. 2015. Evaluating methods for estimating local effective population size with and without migration. Evolution 69:2154-2166. [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, M. E., and M. E. Soulé. 1986. Minimum viable populations: processes of species extinction. Pp. 19-34 in M. E. Soulé, ed. Conservation Biology: the Science of Scarcity and Diversity. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Hamilton, M. B., M. Tartakovsky, and A. Battocletti. 2018. speed-ne: Software to simulate and estimate genetic effective population size (Ne) from linkage disequilibrium observed in single samples. Molecular Ecology Resources 18:714-728. [CrossRef]

- Bierbach, and K. E. Linsenmair. 2011. A description of teleost fish diversity in floodplain pools ('Whedos') and the Middle-Niger at Malanville (north-eastern Benin). Journal of Applied Ichthyology 27:1095-1099. [CrossRef]

- Hoban, S., M. W. Bruford, J. M. da Silva, W. C. Funk, R. Frankham, M. J. Gill, C. E. Grueber, M. Heuertz, M. E. Hunter, and F. Kershaw. 2023. Genetic diversity goals and targets have improved, but remain insufficient for clear implementation of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. Conservation Genetics 24:181-191. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, L. A., E. Carrera, A. Adite, and K. O. Winemiller. 2013. Genetic differentiation of a primitive teleost, the African bonytongue Heterotis niloticus, among river basins and within a floodplain river system in Benin, West Africa. Journal of Fish Biology 83:682-690. [CrossRef]

- Husemann, M., F. E. Zachos, R. J. Paxton, and J. C. Habel. 2016. Effective population size in ecology and evolution. Heredity (Edinb) 117:191-2. [CrossRef]

- Ikomi, R. B., and F. O. Arimoro. 2014. Effects of recreational activities on the littoral macroinvertebrates of Ethiope River, Niger Delta, Nigeria. Journal of Aquatic Sciences 29:155-170.

- Jamieson, I. G., and F. W. Allendorf. 2012. How does the 50/500 rule apply to MVPs? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 27:578-584. [CrossRef]

- Kamath, P. L., M. A. Haroldson, G. Luikart, D. Paetkau, C. Whitman, and F. T. Van Manen. 2015. Multiple estimates of effective population size for monitoring a long-lived vertebrate: an application to Yellowstone grizzly bears. Molecular Ecology 24:5507-5521. [CrossRef]

- Laë, R. 1995. Climatic and anthropogenic effects on fish diversity and fish yields in the Central Delta of the Niger River. Aquatic Living Resources 8:43-58. [CrossRef]

- Lederoun, D., K. R. Lalèyè, A. R. Boni, G. Amoussou, H. Vodougnon, H. Adjibogoun, and P. A. Lalèyè. 2018. Length–weight and length–length relationships of some of the most abundant species in the fish catches of Lake Nokoué and Porto-Novo Lagoon (Benin, West Africa). Lakes & Reservoirs: Research & Management 23:351-357. [CrossRef]

- Lind, C. E., S. K. Agyakwah, F. Y. Attipoe, C. Nugent, R. P. Crooijmans, and A. Toguyeni. 2019. Genetic diversity of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) throughout West Africa. Scientific Reports 9:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Lind, C. E., R. E. Brummett, and R. W. Ponzoni. 2012. Exploitation and conservation of fish genetic resources in Africa: issues and priorities for aquaculture development and research. Reviews in Aquaculture 4:125-141. [CrossRef]

- Lonsinger, R. C., J. R. Adams, and L. P. Waits. 2018. Evaluating effective population size and genetic diversity of a declining kit fox population using contemporary and historical specimens. Ecology and Evolution 8:12011-12021. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B. E. 2016. Inland fisheries of tropical Africa. J. F, Graig, Freshwater Fisheries Ecology (eds.). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.:349.

- Moreau, J. 1982. Expose synoptique des donnees biologiques sur Heterotis niloticus (Cuvier, 1829). FAO Synopsis sur les pèches:1-45.

- Mshelia, M. B., A. N. Okaeme, N. O. Dantoro, J. A. Abiodun, O. M. Olowosegun, and I. Y. Yemi. 2005. Responsible fisheries enhancing poverty alleviation of fishing communities of Lake Kainji. 19th Annual Conference of the Fisheries Society of Nigeria (FISON), Ilorin, Nigeria. 597-604. Available from.

- Mustapha, M. K. 2010. Heterotis niloticus (Cuvier, 1829) a threatened fish species in Oyun reservoir, Offa, Nigeria; the need for its conservation. Asian Journal of Experimental Biological Sciences 1:1-7.

- Oladimeji, T. E., I. C. Caballero, M. Mateos, M. O. Awodiran, K. O. Winemiller, A. Adite, and L. A. Hurtado. 2022. Genetic identification and diversity of stocks of the African bonytongue, Heterotis niloticus (Osteoglossiformes: Arapaiminae), in Nigeria, West Africa. Scientific Reports 12:8417. [CrossRef]

- Olaosebikan, B. D., and N. O. Bankole. 2005. An analysis of Nigerian freshwater fishes: those under threat and conservation options. Proceedings of the 19th annual conference of the fisheries society of Nigeria (FISON), 29 Nov - 03 Dec 2004, Ilorin, Nigeria. 754–762. Available from.

- Olukolajo, S., Olufemi, and E. Hillary, Chikezie. 2012. Species diversity and growth pattern of the fish fauna of Epe Lagoon, Nigeria. Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science 7:392-401. [CrossRef]

- Palstra, F. P., and D. E. Ruzzante. 2008. Genetic estimates of contemporary effective population size: what can they tell us about the importance of genetic stochasticity for wild population persistence? Molecular Ecology 17:3428-3447. [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R., and P. E. Smouse. 2012. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics 28:2537-2539. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pereira, N., J. Wang, H. Quesada, and A. Caballero. 2022. Prediction of the minimum effective size of a population viable in the long term. Biodiversity and Conservation 31:2763-2780. [CrossRef]

- Pita, A., M. Pérez, F. Velasco, and P. Presa. 2017. Trends of the genetic effective population size in the Southern stock of the European hake. Fisheries research 191:108-119. [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld, B., F. Thoto, D. Houessou, and L. Wesenbeeck. 2019. Tragedy of the inland lakes. International Journal of the Commons 13:609–636. [CrossRef]

- Sovic, M., A. Fries, S. A. Martin, and H. Lisle Gibbs. 2019. Genetic signatures of small effective population sizes and demographic declines in an endangered rattlesnake, Sistrurus catenatus. Evolutionary Applications 12:664-678. [CrossRef]

- United Nations-Department of Economic and Social Affairs-Population Division. 2019. World population prospects 2019: Highlights (st/esa/ser. A/423).

- Waples, R. S., T. Antao, and G. Luikart. 2014. Effects of overlapping generations on linkage disequilibrium estimates of effective population size. Genetics 197:769-80. [CrossRef]

- Waples, R. S., and C. Do. 2008. LDNE: a program for estimating effective population size from data on linkage disequilibrium. Molecular Ecology Resources 8:753-6. [CrossRef]

- Waples, R. S., and C. H. I. Do. 2010. Linkage disequilibrium estimates of contemporary Ne using highly variable genetic markers: a largely untapped resource for applied conservation and evolution. Evolutionary Applications 3:244-262. [CrossRef]

- Waples, R. S., and P. R. England. 2011. Estimating contemporary effective population size on the basis of linkage disequilibrium in the face of migration. Genetics 189:633-644. [CrossRef]

- Wikondi, J., E. P. J. Ngono, A. T. Nana, F. Meutchieye, and M. E. T. Tomedi. 2023. Farming Features of African Bonytongue Fish Heterotis niloticus in Cameroon, Central Africa. Open Journal of Animal Sciences 13:232-248. [CrossRef]

- Wood, J. L. A., M. C. Yates, and D. J. Fraser. 2016. Are heritability and selection related to population size in nature? Meta-analysis and conservation implications. Evolutionary Applications 9:640-657. [CrossRef]

- Yem, I. Y., A. O. Sani, N. O. Bankole, H. U. Onimisi, and Y. M. Musa. 2007. Over fishing as a factor responsible for declined in fish species diversity of Kainji, Nigeria. 21st Annual Conference of the Fisheries Society of Nigeria (FISON), Calabar, Nigeria. 79-85. Available from http://hdl.handle.net/1834/37723.

| Production (average per year) | * Yearly Production * | |||||||||

| Region | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

Percentage of world’s total for 2020 |

| Africa – inland | 1.47M | 1.89M | 2.33M | 2.87M | 3.01M | 3.02M | 3.24M | 3.21M | 3.49M | 28 |

| Africa - Heterotis | 5,961 | 12,653 | 23,876 | 31,815 | 29,257 | 28,649 | 27,818 | 27,777 | ||

|

Nigeria – inland % of Africa |

100,513 (6.8%) |

104,173 (5.3%) |

210,970 (9.01%) |

350,175 (12.2%) |

420,078 (14.0%) |

392,188 (12.9%) |

373,344 (11.4%) |

354378 (10.9%) |

362,792 (10.4%) |

3 (9th globally) |

|

Nigeria –Heterotis % of Africa |

4,770 (80.0%) |

10,877 (86.0%) |

20,606 (86.3%) |

27,896 (87.7%) |

25,689 (87.8%) |

24,626 (86.0%) |

23,375 (84.0%) |

23,875 (86.0%) |

||

| Benin - inland | 31,823 | 31,830 | 28,664 | 28,969 | 33,415 | 28,900 | 28,775 | 28,815 | 29,000 | |

| Benin - Heterotis | 421 | 565 | 564 | 791 | 853 | 1398 | 925 | 1,085 | 1,095 | |

| Comparison | Genetic differentiation test | ||||||

| Pop1 | Pop2 | Fst | Gst | G'st(Nei) | G'st(Hed) | G''st | Dest |

| Centre | South | 0.041 | 0.024 | 0.047 | 0.079 | 0.101 | 0.057 |

| Centre | Littoral | 0.035 | 0.023 | 0.045 | 0.082 | 0.103 | 0.061 |

| South | Littoral | 0.049 | 0.031 | 0.060 | 0.097 | 0.124 | 0.068 |

| Centre | North | 0.047 | 0.035 | 0.068 | 0.162 | 0.191 | 0.132 |

| South | North | 0.083 | 0.066 | 0.124 | 0.264 | 0.309 | 0.212 |

| Littoral | North | 0.051 | 0.039 | 0.075 | 0.169 | 0.200 | 0.136 |

| Centre | Far-North | 0.088 | 0.076 | 0.142 | 0.320 | 0.368 | 0.264 |

| South | Far-North | 0.129 | 0.111 | 0.201 | 0.410 | 0.469 | 0.336 |

| Littoral | Far-North | 0.072 | 0.060 | 0.113 | 0.239 | 0.282 | 0.190 |

| North | Far-North | 0.059 | 0.046 | 0.089 | 0.244 | 0.278 | 0.207 |

| Population |

Raw Ne (Corrected Ne assuming AL = 9–4) 95% CI Parametric of raw Ne 95% CI Jackknife of raw Ne |

||

| MAF = 0.05 | no singletons | MAF = 0.02 | |

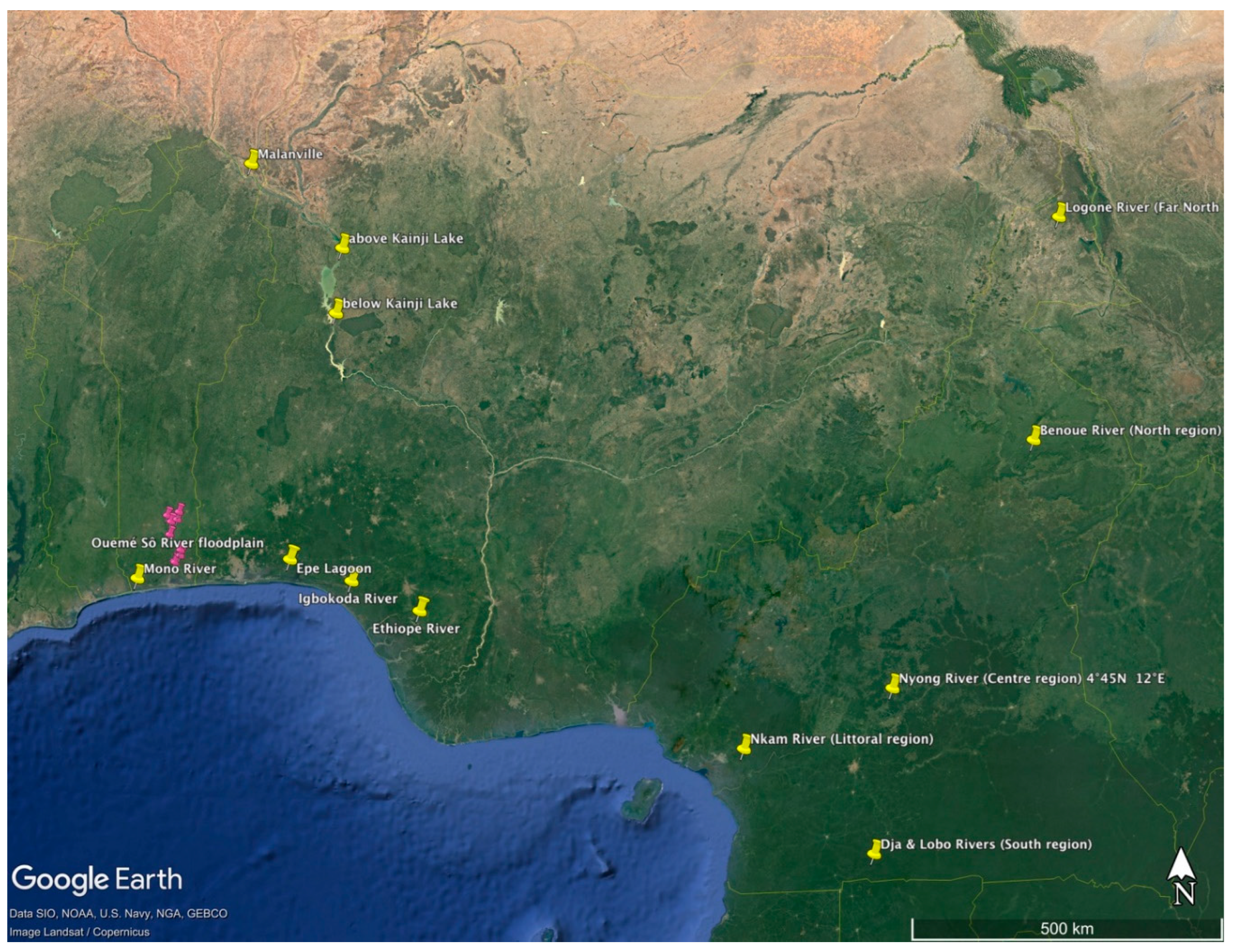

| Nigeria Populations: | |||

| Kainji Lake | 23.7(25.6–32.3) | 27.7(30.0–37.7) | 44.3*(47.9–60.4) |

| 14.2–48.9 | 18.1–49.3 | 27.6–93.0 | |

| 9.3–278.0 | 11.6–281.0 | 20.9–333.7 | |

| Epe Lagoon | 23.1(25.0–31.5) | 18.1*(19.6–24.7) | |

| 11.3–84.4 | 10.5–38.8 | ||

| 8.4–∞ | 7.2–116.6 | ||

| Igbokoda1 | ∞ | ∞ | ∞* |

| 21.5–∞ | 21.5–∞ | 242.0–∞ | |

| 14.9– ∞ | 14.9– ∞ | 62.3–∞ | |

| Igbokoda2 | 288.0(311.6–392.3) | ∞* | |

| 18.5–∞ | 4703.4–∞ | ||

| 11.6–∞ | 180–∞ | ||

| Ethiope River | 42.2(45.7–57.5) | 56.5*(61.1–77.0) | |

| 15.6– ∞ | 19.6– ∞ | ||

| 8.2– ∞ | 13.7– ∞ | ||

| Benin Populations: | |||

| Ouemé–Sô River fldp. | 92.1(99.7–125.5) | 266.1(287.9–362.5) | 179.5(194.2–244.5) |

| 69.5–125.8 | 196.5–390.4 | 131.3–262.9 | |

| 44.2–250.1 | 137.8–947.8 | 78.9–1031.0 | |

| Mono River | 22.9(24.8–31.2) | 28.7*(31.1–39.1) | |

| 9.2–904.8 | 12.4–662.8 | ||

| 9.1–2310.1 | 9.8–∞ | ||

| Malanville | 27.0(29.2–36.8) | 25.5*(27.6–34.7) | |

| 3.0–∞ | 4.7–∞ | ||

| 2.1–∞ | 10.0–∞ | ||

| Cameroon Populations: | |||

| Benoue River (North) | 48.0(51.9–65.4) | 56.2(60.8–76.6) | 63.7*(68.9–86.8) |

| 19.1–∞ | 21.6–∞ | 24.4–∞ | |

| 14.6–∞ | 17.3–∞ | 23.0–∞ | |

| Logone Riv. (Far-North) | 61.3(66.3–83.5) | 103.2*(111.7–140.6) | |

| 17.1–∞ | 22.7–∞ | ||

| 11.1–∞ | 17.5–∞ | ||

| Nkam River (Littoral) | ∞ | ∞ | ∞* |

| 36.3–∞ | 82.9–∞ | 32.1–∞ | |

| 11.3– ∞ | 24.4– ∞ | 31.1–∞ | |

| Dja & Lobo Riv. (South) | 2.6(2.8–3.5) | 2.6*(2.8–3.5) | |

| 1.2–18.3 | 1.4–11.9 | ||

| 0.7–∞ | 1.3–14.7 | ||

| Nyong River (Centre) | ∞ | ∞* | |

| 23.1– ∞ | 26.5– ∞ | ||

| 12.6– ∞ | 15.7– ∞ | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).