1. Introduction

Illnesses associated with microbial foodborne pathogens are a major worldwide health concern, impacting millions of people annually. WHO (World Health Organization) estimates that nearly 1 in 10 individuals worldwide become ill after ingesting contaminated food, leading to 600 million cases of foodborne illnesses annually [

1]. The consequences extend beyond mere illness, with economic losses, hospitalizations, and even fatalities imposing a heavy toll on societies. Pathogens like

Salmonella,

Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, and norovirus are liable for numerous outbreaks, underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring and robust detection strategies. Efforts to curb the impact of foodborne illnesses are challenged by several factors, including the globalization of food trade, changes in food consumption habits, and the appearance of novel and infectious pathogens strains. These dynamics have heightened the complexity of safeguarding our food supply and underscored the importance of adopting innovative technologies that can swiftly and accurately detect the presence of harmful pathogens [

1,

2]. Rapid and precise foodborne pathogens detection is critical for controlling foodborne diseases. Traditional detection methods, such as culture-based approaches need a lot of time and effort, often taking several days to obtain results. This delay in detection can lead to the ingesting of contaminated food, resulting in the spread of pathogens and increased risks to public health. Therefore, there is a need for faster and more efficient detection methods that can provide real-time results [

3].

Single-mode biosensing approaches, such as nucleic acid-based approaches and immunological procedures, have been advanced for foodborne pathogens detection. However, these methods have limitations. Nucleic acid-based methods require complex sample preparation procedures and amplification steps, which might be tedious and prone to errors. Immunological methods rely on the specificity of antibodies, which may not always be available for all pathogens or may cross-react with other microorganisms [

4]. These limitations highlight the need for alternative approaches that can overcome these challenges.

Multimodal biosensing strategies, which combine multiple detection modalities, offer a promising solution to overcome the limitations of single-mode biosensing approaches. By integrating different sensing techniques,

i.e., immunological approaches, nucleic acid-based procedures, and biosensor-based techniques, multimodal biosensing can enhance the sensitivity, specificity, and rapidity of pathogen recognition [

4,

5,

6,

7]. As an example, the combination of nucleic acid-based methods with biosensor-based methods can provide rapid and accurate detection by targeting specific genetic sequences of pathogens and detecting their presence using highly sensitive biosensors [

4]. This approach can improve the overall performance of foodborne pathogen detection systems and enable real-time monitoring of food safety.

This article offers a thorough exploration of the current state of multimodal biosensing opportunities for foodborne pathogen detection. The focus will be on integrated approaches that involve combining two or more biosensing techniques to enhance accuracy, efficacy, and precision. Various aspects of multimodal biosensing are covered, including optical-based, electrochemical, nanomaterial-enhanced, and mass spectrometry-based platforms. It discusses the advantages, challenges, and potential applications of these technologies, as well as their implications for food safety and public health.

2. Multimodal biosensing techniques

2.1. Optical biosensing

Optical biosensing techniques have become effective powerful tools for foodborne pathogens detection because of their excellent sensitivity, label-free sensing capabilities, and real-time monitoring. This section explores three prominent optical techniques: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensors, fluorescence-based biosensors, and an innovative coupling of Raman spectroscopy.

2.1.1. SPR biosensors

SPR biosensors utilize the phenomenon where light interacts with a metal surface and generates an evanescent wave that is sensitive to cause a shift in refractive index near a surface. One approach to enhance the performance (e.g., sensitivity) of SPR biosensors for foodborne pathogens sensing is the use of long-range surface plasmons (LRSPs) together with magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) assays. LRSPs demonstrate low losses in contrast to regular surface plasmons, resulting in narrower resonance and improved quality [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The use of MNPs can further improve a sensor response by facilitating an analyte delivery to the surface of a sensor and amplifying a change in refractive index linked to the detection of a desirable analyte. This approach has demonstrated high sensitivity with

E. coli O157-H7 detection at lower concentrations of 50 CFU/mL [

12]. SPR biosensors provide a powerful platform for foodborne pathogens sensing. The combination of LRSPs and MNPs has demonstrated promise in improving the sensitivity and performance of these biosensors [

13]. SPR biosensor development for food control and pathogen detection has the potential to revolutionize food safety and public health [

14].

Wang et al. introduce an innovative approach to SPR biosensors utilizing grating-coupled LRSPs enhanced by MNP immunoassays. The sensor chip, created through nanoimprint lithography, exhibited an impressive 8.5-fold improvement in refractive index resolution compared to standard grating-coupled surface plasmons (GC-SPs). Employing MNPs, the assay efficiently captured target

E. coli O157:H7 pathogens, significantly enhancing a sensor signal. This LRSP method achieved a remarkable limit of detection at 50 CFU mL

–1, demonstrating sensitivity four orders of magnitude superior to conventional GC-SP resonance in direct detection formats [

15]. Another study presents an MNPs-enhanced SPR biosensor modified for rapid detection of

Salmonella Typhimurium in romaine lettuce. By integrating MNPs into a detection process, a biosensor demonstrated heightened sensitivity and speed in capturing a target pathogen. An innovative approach allowed for swift and accurate identification of

Salmonella Typhimurium presence, showcasing the biosensor's potential for enhancing food safety measures in fresh produce [

16].

An application of SPR biosensors for food control and pathogen identification has gained significant attention in recent years. These biosensors offer advantages such as simplicity, rapidity, and the potential for integration with microfluidic systems for automatic pathogen capture and detection [

17]. They have the potential to simplify procedures and reduce time, cost, and reactant consumption compared to traditional methods.

2.1.2. Fluorescence-based biosensors

Fluorescent-based biosensors are a unique approach for foodborne pathogen detection. The fabrication of fluorescent-based biosensors utilizes the principles of fluorescence to sense and measure the presence of specific pathogens in food specimens. For instance, Atay et al. discussed the use of nanomaterial interactions with various biorecognition components for the biosensing of important foodborne pathogens. They highlight the requirement for precise and fast identification and sensing of foodborne pathogens, as conventional techniques have constraints in terms of specificity and selectivity. Further, they review aptamers, nanofibers, and biosensors based on metal-organic frameworks for food pathogen identification. They explain the conventional methods, types of biosensors, common transducers, and recognition elements used in these biosensors. They also introduce novel signal amplification materials and nanomaterials that boost the sensitivity and performance of the biosensors. For instance, carbon quantum dots and DNA tetrahedron-aptamer structures modified with magnetic beads have been utilized for foodborne pathogen sensing [

18]. One approach involves combining biofunctional MNPs (Magnetic Nanoparticles) with fluorescence dyes. Gao et al. demonstrated that the procedure combining FePt-Van bio-functional MNPs with fluorescence dyes might attain fast, sensitive, and inexpensive bacteria recognition in the blood. FePt-NPS (FePt Nanoparticles) serves as a foundation for initiating vancomycin, which enables multivalent associations. Fluorescent vancomycin, a mixture of Vancomycin and fluorescein amine (Van-FLA), can stain enhanced bacteria for fast detection by employing fluorescence microscopy [

19].

Fluorescence-based biosensors offer quick and sensitive foodborne pathogen identification. These biosensors have benefits, such as excellent sensitivity, specificity, and ease of operation. The integration of nanomaterials and signal amplification strategies further enhances their performance. The development of precise and rapid fluorescence-based biosensing techniques is fundamental for confirming food safety and combating foodborne diseases.

2.1.3. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)

SERS has become a promising technique for the detection of foodborne pathogens. SERS is a sensitive and label-free analytical approach that can provide molecular fingerprinting of analytes based on their unique Raman scattering patterns. It offers various advantages, including high sensitivity, rapid analysis, and the ability to detect multiple pathogens concurrently. These biosensors can be integrated with SERS to improve the sensitivity/selectivity of pathogen recognition. For example, Zhao et al. demonstrated the identification of foodborne pathogens, such as

Salmonella and

E. coli, using SERS-based biosensors. They utilized gold nanoparticles as the SERS substrate and functionalized them with specific antibodies for pathogen recognition. The binding of pathogens to the antibody-functionalized nanoparticles resulted in enhanced Raman signals, enabling sensitive and specific pathogen sensing. In addition to integrating SERS with biosensors, other approaches have been investigated to improve the capability of SERS-based pathogen sensing. For example, gold or silver nanoparticles can enhance the Raman signals and provide a larger surface area for pathogen binding. Nanoparticle surface modification with specific ligands or antibodies can further enhance the selectivity of pathogen detection. Despite the benefits of SERS for foodborne pathogen sensing, there still exist some limitations to be addressed. One issue is the standardization of sample preparation and measurement protocols to ensure reproducibility and comparability of results. Another challenge is the development of robust and portable SERS instrumentation for on-site sensing in food processing facilities or field settings [

20].

Raman spectroscopic methods have shown promise in food safety detection, offering potential opportunities for rapid and accurate analysis [

21]. In the clinical field, Raman spectroscopy has shown promise for future SERS applications. Understanding the recent progress of Raman spectroscopy in medical research can guide the design of future SERS studies, benefiting researchers and clinicians [

22]. In a study performed by Xu et al., they suggested a novel approach for rapid food safety identification using an adaptable, stable, and sensitive SERS substrate made of graphite/titanium cotton. The research aimed to address the challenges associated with conventional food safety detection methods, such as time-consuming sample preparation and limited sensitivity [

23]. In conclusion, SERS holds excellent potential for the identification of foodborne pathogens. By integrating SERS with biosensors and utilizing nanomaterials, sensitive and specific pathogen sensing can be achieved. However, further research is required to address the challenges relating to sample preparation, instrumentation, and cost-effectiveness to enable the widespread application of SERS in food safety.

2.2. Electrochemical biosensing

2.2.1. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS-based biosensors are a viable approach for identifying foodborne pathogens. These biosensors offer several benefits over conventional detection techniques, including simplicity of operation, rapid detection speed, high sensitivity, and low cost [

24]. Unlike immunological and nucleic acid-based approaches, which require sample pre-enrichment to concentrate the pathogens before sensing, EIS-based biosensors do not need sample pre-enrichment. This eliminates the need for time-consuming and labor-intensive sample preparation steps, making EIS-based biosensors a more efficient and convenient option for foodborne pathogen detection [

25]. EIS-based biosensors work by measuring the impedance changes that occur at the electrode surface when the target pathogens interact with the sensing elements immobilized on the electrode [

24]. The impedance fluctuations are then correlated with the presence and concentration of the pathogens. The sensing elements used in EIS-based biosensors can vary but commonly include antibodies, aptamers, or phages [

26,

27]. These recognition elements specifically bind to the target pathogens, allowing for selective detection [

27].

The integration of EIS-based biosensors with microfluidic technology has further enhanced their performance. Microfluidic chips offer several advantages, such as a large specific surface area, a small volume, excellent sample treatment capability, a short detection time, automatic operation, and lack of cross-contamination [

24]. These features make microfluidic-based EIS biosensors highly suitable for point-of-care and on-site applications, where quick and precise identification of foodborne pathogens is crucial for confirming food safety. Numerous investigations have demonstrated the efficiency of EIS-based biosensors in detecting foodborne pathogens. For example, portable electrochemical biosensors have been used to identify bacterial contamination in dairy products [

28].

Additionally, phage-based biosensors, which incorporate electrochemical transducers, have been employed for the rapid identification of live pathogens in food [

26]. These biosensors have shown high sensitivity, specificity, and reliability in sensing foodborne bacterial pathogens. EIS-based biosensors offer a viable approach to fast and sensitive recognition of foodborne pathogens. They eliminate the need for sample pre-enrichment and provide benefits such as simplicity of operation, rapid detection speed, excellent sensitivity, and low cost. The integration of EIS-based biosensors with microfluidic technology further enhances their performance, making them appropriate for point-of-care and on-site applications.

2.2.2. Amperometric and voltammetric biosensors

Amperometric and voltammetric biosensors have proven to be effective tools for sensing foodborne pathogens. These biosensors rely on electrochemical principles to sense and measure the presence of pathogens in food samples. Amperometric biosensors are based on the analysis of current generated by the electrochemical reaction between a target analyte and a bioreceptor attached to a sensor surface. For instance, Wang et al. demonstrated the use of carbon nanotube (CNT)/Teflon composite electrodes for amperometric detection of ethanol and glucose. The use of glucose oxidase and alcohol dehydrogenase/NAD(+) within the CNT/Teflon matrix enabled effective low-potential amperometric detection of these analytes. CNT-based composite devices offer advantages such as enhanced electron transfer, minimized surface fouling, and renewability of the sensor surface. In contrast, voltammetric biosensors measure current as a function of the voltage. The electrocatalytic properties of CNTs make them attractive for voltammetric biosensing. Additionally, the fabrication of CNT/Teflon composite electrodes, combining the benefits of CNTs with "bulk" composite electrodes, has been described. The loading of CNTs in a composite electrode was found to impact current and voltage data, as well as electrode resistance [

29].

The use of amperometric and voltammetric biosensors for foodborne pathogen detection has gained significant attention. Atay et al. reported that approximately 33% of electrochemical biosensors used in pathogen detection are amperometric, while 12% are voltammetric. Amperometric biosensors, in particular, have a long history and are widely used commercially [

18]. For example, Quintela et al. presented a sandwich-type bacteriophage-based amperometric biosensor for sensing STEC serogroups in complex matrices. The biosensor demonstrated high sensitivity, specificity, and reliability in detecting STEC in food samples, with a detection limit of 10 CFU/mL. This research contributes to the advancement of innovative biosensing technologies for food safety applications [

30].

2.3. Nanomaterial-based biosensing

2.3.1. Nanoparticles and quantum dots

Nanoparticles and quantum dots have emerged as effective nanomaterials for the detection of foodborne pathogens. Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) have garnered attention in the field of food safety due to their bright luminescence, low toxicity, and enrichment capabilities. These nanomaterials have been employed in fluorescence sensors for the accurate identification of various contaminants in food products, including pathogenic bacteria, food additives, heavy metal ions, food nutrients, and veterinary drug residues. The use of CQDs in fluorescence sensors is based on mechanisms such as fluorescent resonance energy transfer, internal filtering effect, and photoinduced electron transfer [

31]. In addition to CQDs, other carbon nanomaterials like graphene quantum dots (GQDs) have been explored for their potential as sensors in food analysis. These nanomaterials can be integrated with optical sensors to detect various contaminants in food samples, including insecticides, pesticides, antibiotics, toxic metals, mycotoxins, and microorganisms. The sensing approaches employed in these sensors encompass colorimetric sensing, fluorescence sensing, SERS, SPR, electroluminescence, and chemiluminescence [

32]. Apart from CQDs, various types of nanoparticles have been used for the detection of foodborne pathogens. For example, polyvinyl alcohol nanoparticles (PVA-NPs) grafted with naringenin have been studied for their antimicrobial efficacy on fresh beef. These nanoparticles demonstrated a slow and gradual release of naringenin, making them suitable for application in food models. Their antibacterial effectiveness was demonstrated against various foodborne pathogens [

33]. Quantum dots (QDs), including CQDs, in general, have shown promise for use in the food industry. Their unique properties, such as their small size and suitability for food analysis, make them attractive for quality assessment and safety control in food manufacturing. QDs used in food analysis can contribute to the improvement of food safety systems by enabling the detection of foodborne pathogens and extending the shelf life of food products [

34].

Magnetic nanoparticles have also been developed for the simultaneous detection of foodborne pathogens, such as

C. jejuni,

E. coli,

Vibrio cholera, and

Salmonella enterica. These nanoparticles enable the simple and efficient detection of multiple pathogens [

35]. Various nanomaterials, including magnetic beads, quantum dots, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene oxide, and plasmonic gold, have been employed for the sensing of foodborne pathogens. Synthetic DNA molecular beacon probes labeled with color codes have been utilized as nano barcodes for the detection of food pathogens. Additionally, silver nanoparticles have been used to coat the surfaces of refrigerators and storage containers to inhibit the spread of foodborne pathogens and food spoilage bacteria [

36].

Nanoparticles and quantum dots, particularly CQDs, have demonstrated significant potential for the detection of foodborne pathogens. These nanomaterials can be integrated into fluorescence sensors and optical sensors to enable precise and sensitive identification of contaminants in food products.

2.3.2. Nanowires and nanotubes

Nanowires and nanotubes have shown great promise in the detection of foodborne pathogens. These nanomaterials possess attractive properties that make them well-suited for highly sensitive and selective detection of (bio)chemical species. Nanowires, such as silicon nanowires (SiNWs), have been employed as nanosensors for the detection of various (bio)chemical species. SiNWs functionalized with antigens have shown reversible antibody attachment and concentration-dependent real-time sensing. This capability enables sensitive and label-free detection of a wide range of (bio)chemical species, including foodborne pathogens. The small size and sensitivity of nanowires make them suitable for array-based testing and in-vivo assessment.

In addition to nanowires, nanotubes have also been explored for the detection of foodborne pathogens. CNTs have been functionalized with specific aptamers or antibodies to selectively capture and detect target pathogens. The unique electrical and optical properties of CNTs enable label-free pathogen sensing through various mechanisms, such as impedance spectroscopy, field-effect transistor-based (FET) sensing, and fluorescence quenching [

37]. Another study by Zhang et al. investigated the use of CNTs for the detection of foodborne pathogens. Researchers developed a label-free electrochemical biosensor based on CNT-modified electrodes for the detection of

Salmonella typhimurium. The biosensor exhibited high sensitivity and specificity, with a LOD of 10 CFU/mL. CNTs provide a conductive and biocompatible platform for the attachment of antibodies, enabling specific recognition of target pathogens [

38]. Furthermore, the compatibility of nanowires and nanotubes with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology facilitates the development of label-free immunodetection platforms. CMOS-compatible semiconducting nanowires have been used for label-free immunodetection, enabling sensitive and specific sensing of target pathogens [

39].

Nanowires and nanotubes hold great promise for the detection of foodborne pathogens. Their large surface-to-volume ratio, small size, and amenability to functionalization with recognition elements make them ideal for sensitive and selective sensing. Integration with other sensing technologies allows for the development of multiplexed detection platforms. Further research and advancements in this field are needed to optimize the effectiveness and applicability of nanowire and nanotube-based sensors for food safety applications.

2.3.3. Nanocomposites

Nanocomposites play a crucial role in enhancing the efficiency of biosensors for the detection of foodborne pathogens. They can serve as sensing elements or platforms for coupling biomolecules like antibodies or DNA probes [

11]. Beyond their use in detection methods, nanocomposites also have potential applications in food processing and packaging. They can act as antimicrobial agents, scavengers of oxidants, or sensors for monitoring food quality and safety. However, it's essential to consider the safety and regulatory aspects of nanocomposites in food applications. Some nanomaterials may have toxic effects on animals and humans, and their potential risks must be thoroughly assessed [

40]. An example of nanocomposites used for sensing foodborne pathogens is the dual-mesoporous WO

3/Au nanocomposites. These nanocomposites have been applied in gas sensing for the detection of 3-hydroxy-2-butanone, a biomarker associated with

Listeria monocytogenes, a common foodborne pathogen. The dual-mesoporous structure of the nanocomposites provides a significant surface area for gas absorption, and the incorporation of gold nanoparticles enhances the sensing performance [

41].

Bacteriophage-based biosensors have been designed using nanocomposites for the precise identification of foodborne bacteria. Bacteriophages, which can recognize viable and non-viable bacteria, are used as the detection element in these biosensors, replacing antibodies. The nanocomposites in these biosensors can enhance signal transduction and improve detection sensitivity [

6]. Microfluidic chip biosensors have also been developed for the identification of foodborne pathogens using nanocomposites. These microfluidic chips offer advantages such as rapid and multiplexed detection, and they can be integrated with nanocomposites to enhance sensing performance. For example, microfluidic devices based on immunomagnetic nanocomposites coupled with urease and impedance measurement have been proposed for the sensing of foodborne pathogens [

24].

2.4. Other Biosensing Modalities

2.4.1. Magnetic Biosensors

Magnetic biosensors have gained significant attention for the detection of foodborne pathogens due to their sensitivity, specificity, and ease of use. These biosensors utilize magnetic nanoparticles as the sensing element, which can be functionalized with specific DNA probes or antibodies for the targeted identification of pathogens [

42]. One type of magnetic biosensor is the magnetic relaxation switch sensor, which is based on a magnetic relaxation signal. This sensor has been widely employed for the rapid identification of foodborne pathogens because it offers background-free detection and high sensitivity. Bacteriophages, which can distinguish between viable and non-viable bacteria, have been used as the recognition components in these biosensors, replacing antibodies. The combination of bacteriophages and magnetic relaxation switch sensors enables precise identification of foodborne pathogens [

6]. A magnetic biosensor was developed for sensing Salmonella using curcumin to report the signal as well as click chemistry to amplify the signal. The biosensor exhibited a correlation between absorbance (468 nm) and

S. Typhimurium concentration, with a LOD of 50 CFU/mL. The biosensor also demonstrated good performance in spiked chicken samples, with a mean accuracy of 107.47% [

42]. Other studies have also explored the application of magnetic biosensors for the detection of foodborne pathogens. One review discussed various biosensors, including magnetic biosensors, for the identification of food pathogens. It highlighted the use of magnetic beads functionalized with DNA tetrahedron-aptamer structures and CQDs for

S. aureus sensing. The biosensor exhibited a LOD of 43 CFU/mL [

18].

Magnetic biosensors offer a promising approach for the detection of foodborne pathogens. They provide rapid and sensitive identification without the need for sample pre-enrichment. Further research and advancements in this field have the potential to lead to the development of practical magnetic biosensors for food safety and pathogen detection applications.

2.4.2. Microfluidics

Microfluidics has emerged as a potent technique for the detection of foodborne pathogens, owing to its ability to manipulate small volumes of fluids and provide rapid and sensitive analysis. The field of microfluidics has seen substantial developments in recent years, enabling the advancement of innovative detection methods. One key advantage of microfluidics is its capability to achieve instant and multiplexed identification of foodborne pathogens. Microfluidic devices can integrate various functional components, including sample preparation, enrichment, and sensing, into a single platform. This integration enabled the simultaneous identification of multiple pathogens from a single sample, reducing the time/cost usually accompanying traditional detection methods. For example, microfluidic chip-based systems have been developed for the concurrent sensing of multiple foodborne pathogens (including

Salmonella,

Listeria monocytogenes, and

E. coli) [

43].

Furthermore, microfluidic devices offer enhanced sensitivity and specificity in pathogen sensing. The small dimensions of microfluidic channels enable efficient mixing and reaction of target pathogens with specific biorecognition elements, such as antibodies or aptamers. This enhanced interface between the target pathogens and the bio-recognition components improves the sensitivity and selectivity of detection. Additionally, microfluidic devices can provide precise control over fluid flow and reaction conditions, further enhancing detection performance [

43].

Microfluidics also enables the development of portable and point-of-care detection systems for foodborne pathogens. The miniaturization of devices and the use of portable readout systems, such as smartphones or handheld detectors, allow for on-site and real-time detection. This portability is particularly valuable in resource-limited settings or during outbreaks, where rapid and decentralized detection is crucial for timely intervention and control measures [

44]. For instance, a microfluidic chip was designed for the detection of

Salmonella in food samples. The chip integrated sample preparation, DNA extraction, and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) on a single platform. The detection of amplified DNA was achieved using a portable fluorescence detector. The microfluidic chip demonstrated an LOD of 10 CFU/mL for

Salmonella in spiked milk samples, with an entire analysis time of less than 2 hours [

45]. Another microfluidic-based immunoassay was utilized for the sensing of

E. coli O157-H7. The microfluidic chip integrated magnetic bead-based immunoassay and electrochemical detection. The chip showed a LOD of 10 CFU/mL for

E. coli O157-H7 in spiked apple juice samples, with an entire analysis time of 60 minutes [

46].

Microfluidics has revolutionized the identification of foodborne pathogens by offering instant, sensitive, and multiplexed analysis. The integration of various functional components, enhanced sensitivity and specificity, and the development of portable systems have significantly advanced the field. Microfluidic-based detection systems can improve food safety and public health by allowing immediate and precise identification of foodborne pathogens.

Table 1.

Development of multimodal biosensing techniques for foodborne pathogens detection.

Table 1.

Development of multimodal biosensing techniques for foodborne pathogens detection.

| Pathogen |

Sample |

Detection Method |

Analysis Time |

LOD |

References |

| E. coli O157-H7 |

Food samples |

Surface plasmon resonance |

30 Min |

50 CFU/mL

|

[14] |

| E. coli, S. aureus, |

Human blood |

Fluorescence-based biosensors |

120 Min |

4 CFU/mL

|

[19]

|

| S.typhimurium |

Food samples

|

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy |

Not Stated |

35 CFU/mL |

[23]

|

| Shiga toxin E. coli |

Water sample |

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

1 hour

|

10-102 CFU/mL |

[29]

|

| Salmonella typhimurium |

Chicken sample |

Magnetic Biosensors |

Not Stated

|

50 CFU/mL |

[42]

|

| Salmonella |

Milk samples |

Microfluidic

Biosensors |

2 hour

|

10 CFU/mL

|

[45] |

| E. coli O157-H7 |

Apple juice samples |

Microfluidic-based immunoassay |

1 hour |

10 CFU/mL

|

[46] |

| E. coli |

Urine Sample |

Colorimetric Biosensors |

Not Stated

|

35 CFU/mL

|

[47]

|

| E. coli |

Water sample |

Anodic particle Colorimetry technique |

Not Stated |

1 CFU/mL

|

[48]

|

| Salmonella typhimurium |

food samples |

Luminescence Bioassay Method |

Not Stated |

10-15 CFU/mL |

[49] |

3. Integrated multimodal biosensing platforms

3.1. Fusion of optical and electrochemical techniques

Integrated multimodal biosensing platforms represent a powerful approach by combining different sensing techniques, such as optical and electrochemical methods, to provide comprehensive and accurate detection of analytes. These platforms have gained significant attention due to their potential applications in numerous fields. Electrochemical biosensors are among the most widely used and successfully commercialized types of biosensors. They are popular because of their high sensitivity, selectivity, and simplicity. Enzyme-based electrochemical biosensors, in particular, have garnered increasing interest due to their promising applications in various areas. These biosensors use enzymes as recognition elements to selectively detect target analytes such as glucose, hydrogen peroxide, phenol, and cholesterol [

50]. On the other hand, optical biosensors offer benefits including label-free detection, real-time detection, and enhanced sensitivity. They depend on the interaction between light and the target analyte to generate a signal for detection. Optical biosensing platforms can be based on various principles, including fluorescence, SPR, and reflectivity measurements [

51,

52]. Supramolecular self-assembly is another approach to enhance biosensing platforms. This technique has been used in enzyme sensing, providing a label-free biosensing system with excellent sensitivity and multimodal readouts. The simplicity of this approach eliminates the need for time-consuming substrate preparation and allows for naked eye detection [

53].

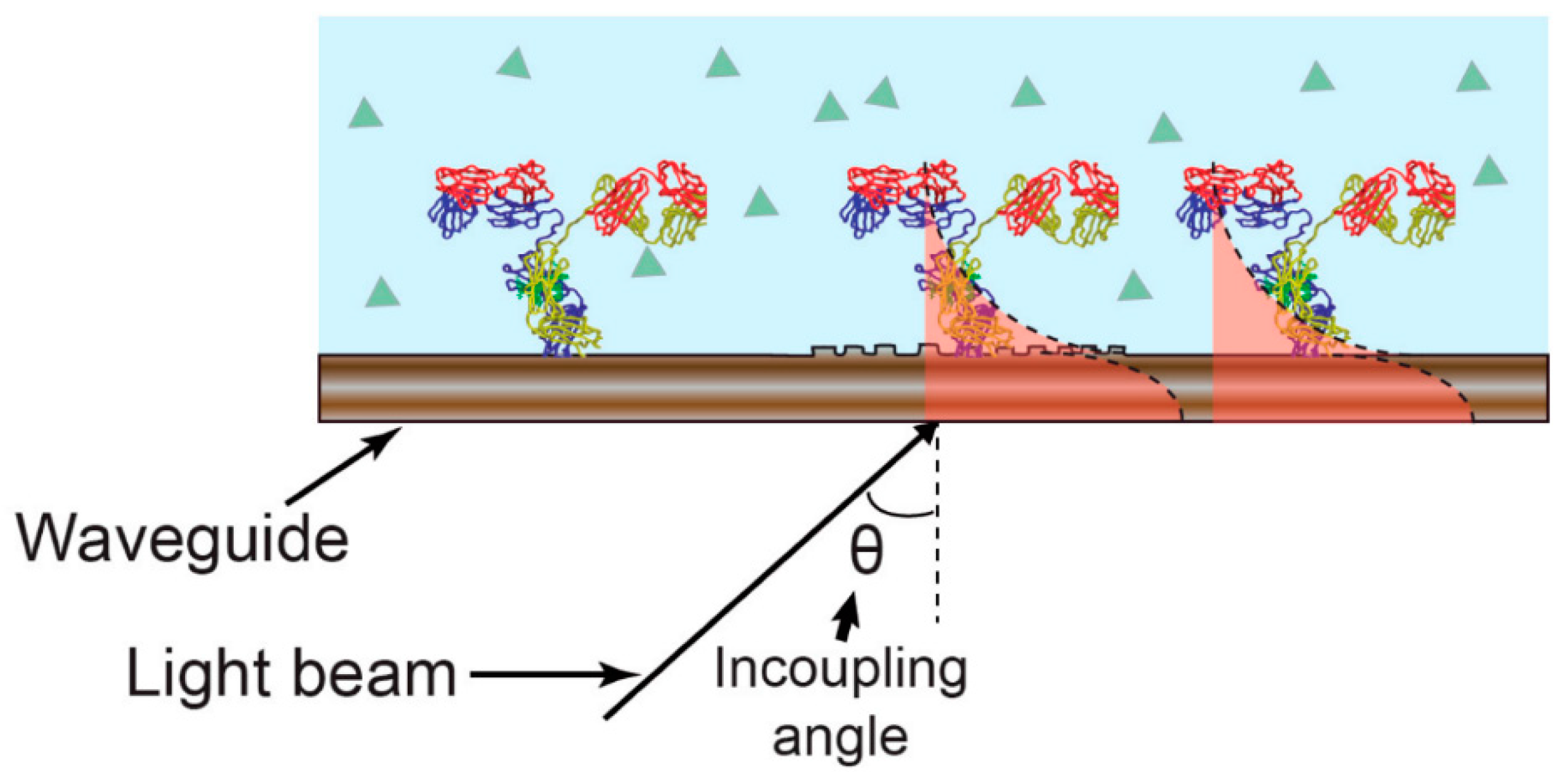

An additional electro-optical technique is electrochemical optical waveguide light mode spectroscopy (EC-OWLS). EC-OWLS integrates the principles of evanescent field optical detection with electrochemical monitoring of surface adsorption processes. This is achieved by integrating an electrochemically and optically consistent layer on an optical platform. In OWLS, a grating is applied to a couple of lights in a waveguide at angular specifications that correspond to transverse magnetic and electric modes. These coupling angles change with a refractive index at the waveguide-solution interface. Measuring these coupling angles enables the characterization of properties related to an adsorbed layer [

54].

Figure 1 provides an illustration of this sensing mechanism.

Integrated multimodal biosensing platforms that fuse optical and electrochemical techniques indeed offer enhanced capabilities for sensing analytes such as foodborne pathogens. These platforms leverage the strengths of various sensing principles to provide comprehensive and accurate results. They have the potential to revolutionize numerous fields, including healthcare, environmental monitoring, and food safety. Continued research and innovation in this field are expected to lead to the development of advanced biosensing technologies with a wide range of applications. These innovations have the potential to improve the detection and response to various analytes, ultimately benefiting public health and safety.

3.2. Combination of optical and nanomaterial-based methods

Integrated multimodal biosensing platforms that combine optical and nanomaterial-based methods have indeed demonstrated significant potential in various biosensing applications. Nanomaterials, such as transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) and nanoporous anodic alumina (NAA), have been extensively explored for their unique properties and their ability to enhance biosensor performance [

55,

56]. TMDs, including MoS

2, have gained interest due to their multi-dimensional structures and structure-dependent electronic, optical, and electrocatalytic properties. MoS

2 nanostructures have found utility in both optical and electrochemical biosensing platforms. For instance, 1D MoS

2 QDs have exhibited good photoluminescence, enabling optical biosensing of various analytes using a simple fluorimetric technique. On the other hand, 2D MoS

2 nanostructures have been investigated for electrochemical biosensing due to their controllable electronic energy levels [

55]. Nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles and silica nanoparticles have also been widely employed in fluorescence-based biosensing. These nanomaterials offer superior optical properties, including brighter fluorescence, a broader range of excitation and emission wavelengths, and increased photostability compared to traditional organic dyes. They can be integrated into biosensing platforms to enhance sensitivity and enable a diverse selection of probes [

57]. NAA is a versatile platform for optical biosensors. NAA possesses unique physical and chemical properties that make it suitable for designing biosensors in conjunction with various optical methods. It has been demonstrated that NAA can enhance the performance of optical biosensors and serve as an alternative to other nanoporous platforms. Researchers have explored the coupling of NAA with various optical detection techniques, and the performance of NAA-based biosensing devices has been evaluated [

56].

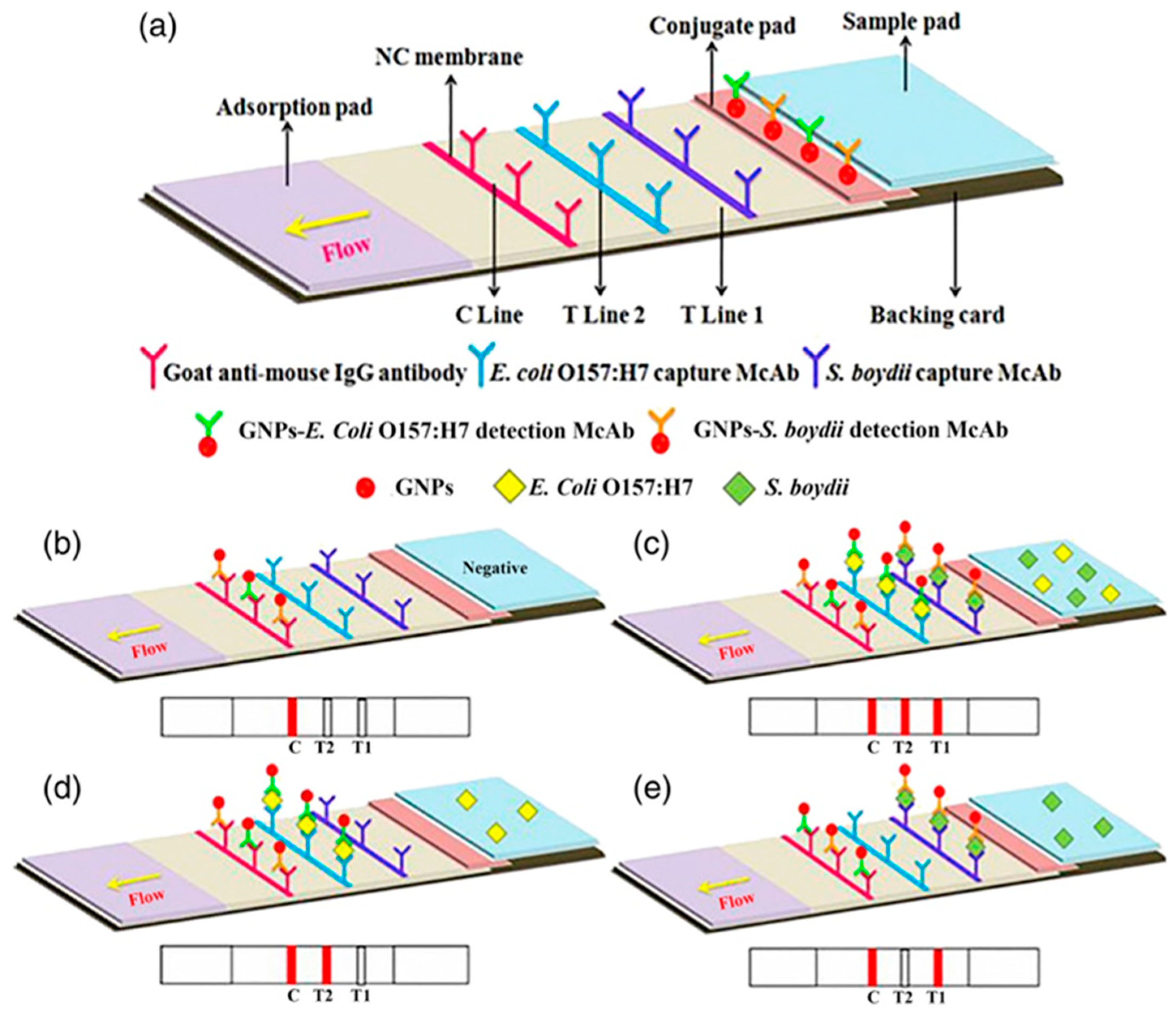

An illustrative example is the work of Song et al. where they developed a method for simultaneous detection of

E. coli O175:H7 and Shigella boydii using a gold immuno-chromatographic strip (ICS). Gold nanoparticles (GNPs) with an approximate diameter of 15 nm were employed and conjugated with monoclonal antibodies specific to these two bacteria. This conjugation was achieved through ionic and hydrophobic interactions between the GNPs and antibodies at a pH level around the isoelectric point of the antibodies. GNPs were separately conjugated with monoclonal antibodies targeting

E. coli O175:H7 and

S. boydii. These GNP-antibody conjugates specific to each bacterium were then combined. Typically, an ICS includes a conjugate pad containing GNP-antibody conjugates or other ligands. In this setup, when a capture antibody specific to each bacterium was immobilized on a membrane, the ICS effectively identified the presence of

E. coli O175:H7,

S. boydii, or both bacteria in a tested sample [

58]. The process for preparing a membrane for GNPs-based ICS is illustrated in

Figure 2a–e.

3.3. Integration of multiple nanomaterials

Integrated multimodal biosensing platforms that incorporate multiple nanomaterials hold significant promise in various biosensing applications. Nanomaterials bring unique properties that can enhance biosensor performance. One widely explored nanomaterial in biosensing platforms is MoS

2. MoS

2 nanostructures have shown tremendous potential because of their distinctive electronic, electrocatalytic, and optical properties. These characteristics make MoS

2 suitable for both electrochemical and optical biosensing applications. MoS

2-based biosensors have demonstrated exceptional sensitivity/selectivity in detecting various analytes. Integrating multiple nanomaterials in biosensing platforms allows for synergistic effects and improved performance. For example, the combination of TiO

2 and MoS

2 nanomaterials can enhance sensing capabilities by leveraging their respective properties. TiO

2 nanomaterials can act as a support matrix for immobilizing enzymes or other recognition elements, while MoS

2 nanomaterials can enhance optical or electrochemical signal transduction [

55].

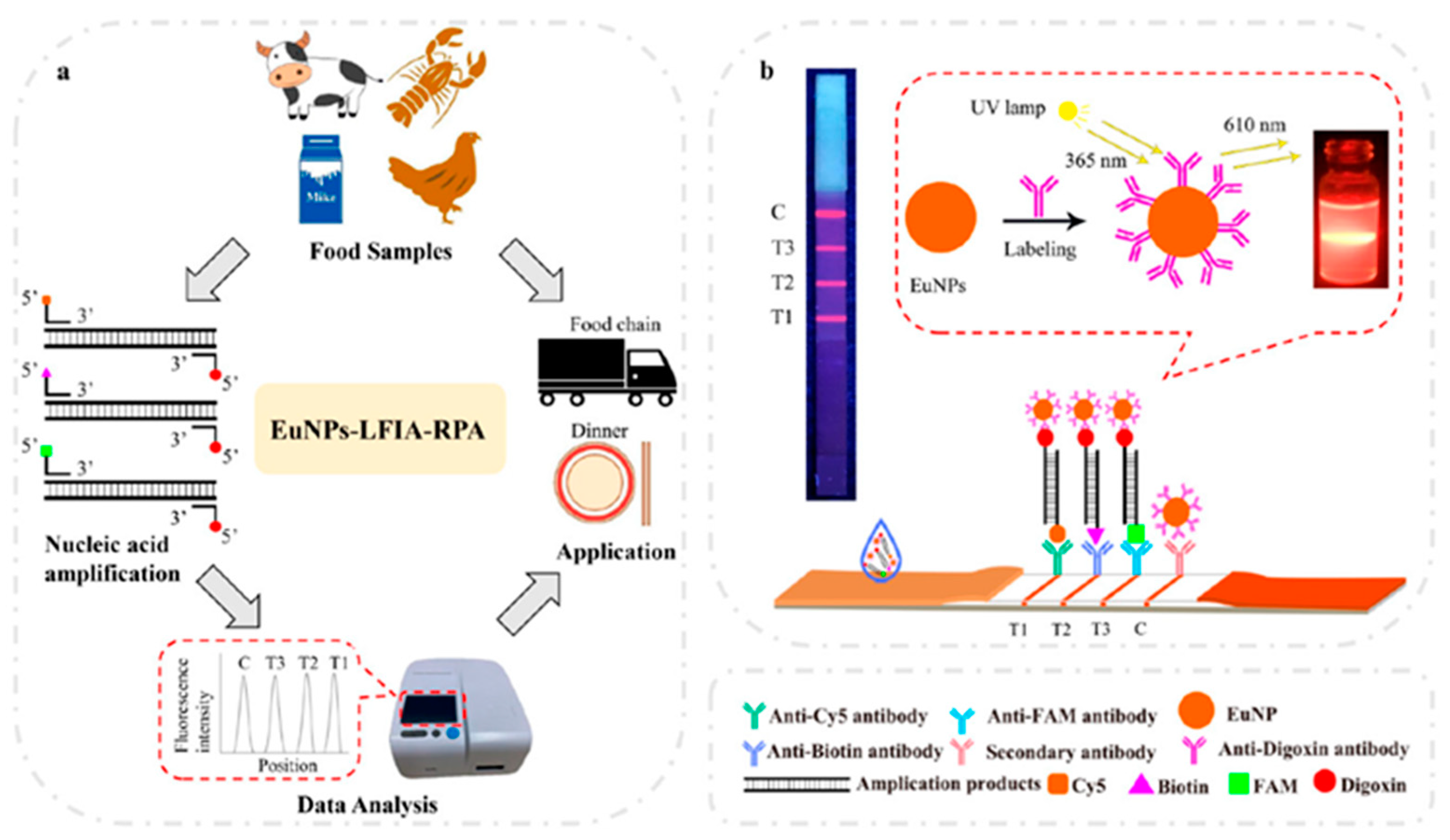

As an illustrative example, Chen et al. described the fundamental components and preparation steps of a lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA), as depicted in

Figure 3. LFIA consists of four essential elements: a nitrocellulose filter (NC) membrane, sample and absorbent pads, and a backing card. To enable detection, conjugates of EuNPs and anti-digoxin monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were applied to the conjugate pad. Additionally, specific antibodies, including anti-biotin, anti-Cy5, and anti-FAM antibodies, were deposited onto three distinct test lines located on the NC membrane. These antibodies were chosen for their ability to detect

Vibrio parahaemolyticus,

Listeria monocytogenes, and E

. coli O157-H7. Furthermore, a control line on the NC membrane was attached with goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibody to serve as the assay control. Sample pads were soaked in phosphate-buffered saline (0.01 M with pH 7.4), dried at 37 ºC for 12 hours, and stored in sealed bags at 25 ºC until use. For a colloidal gold-based LFIA (CG-LFIA), the conjugation process involved anti-digoxin antibodies and colloidal gold applied onto a conjugate pad, while all other aspects remained consistent with a EuNP-based LFIA [

59].

Overall, the study presents a promising approach for fast and sensitive foodborne pathogens detection. The combination of RPA and EuNP-based LFIA offers a potential solution for improving food safety and public health by enabling concurrent detection of multiple pathogens in food samples.

3.4. Hybrid biosensing with microfluidics

Integrated multimodal biosensing platforms based on hybrid biosensing with microfluidics have emerged as a favorable approach for various applications in biomedical research and diagnostics. These platforms combine the advantages of multiple sensing modalities, such as acoustofluidics, electromagnetic metamaterials, and fluorescence enhancement, with the capabilities of microfluidics for sample handling and manipulation.

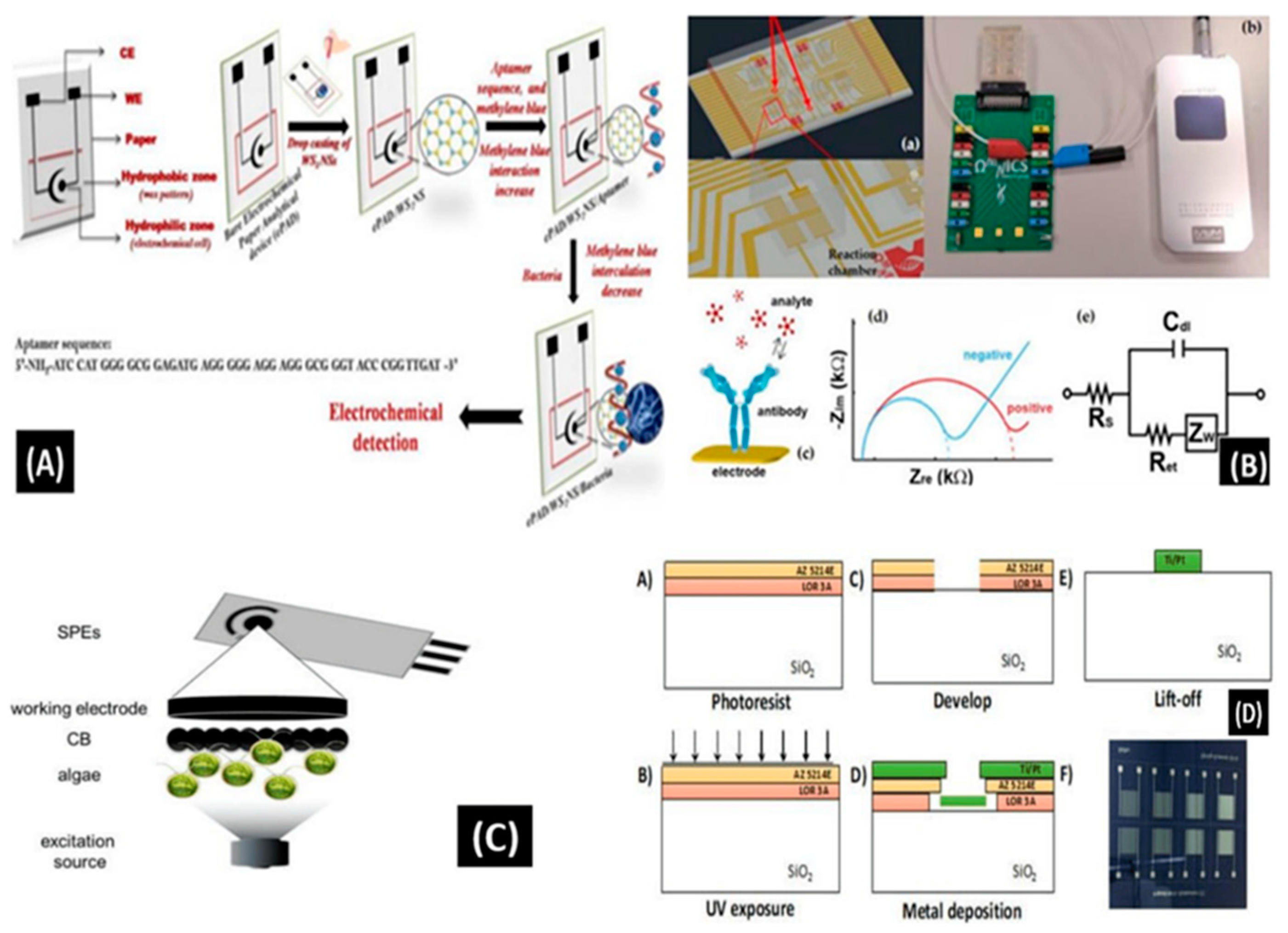

One example of such an integrated biosensing platform is presented in the work by Zahertar et al. They propose a fully integrated biosensing platform that combines the functionalities of acoustofluidic technology and electromagnetic metamaterials into a single device. This platform enables microfluidic performance at acoustic frequencies and the detection of liquid characteristics at microwave frequencies, allowing for enhanced lab-on-a-chip devices [

60]. Another example is Mishra et al. introducing an innovative paper-based aptamer-based electrochemical sensing device for

Listeria monocytogenes detection, a known pathogen responsible for foodborne illnesses. This aptasensor offers numerous advantages: it is easy, consistent, disposable, and inexpensive (

Figure 4A). The incorporation of aptamer enhances its capabilities, further contributing to the field of biosensors. This aptasensor's sensing and quantification limits were established to be 10 and 4.5 CFU/mL, respectively, with a linear range of approximately 101-108 CFU/mL [

61]. Buja et al. (2022) presented a microfluidics-based chip for

ampelovirus and

nepovirus detection. This chip features a multi-chamber design, enabling the simultaneous and rapid identification of these targets. It exhibits the ability to sense GLRaV-3 and Grapevine fanleaf virus (GFLV) at dilution factors over 15 times higher compared to ELISA, thereby providing enhanced sensitivity in virus identification (

Figure 4B). This microfluidic platform is characterized by its simplicity, speed, miniaturization, and cost-effectiveness, making it well-suited for large-scale monitoring evaluations [

62]. Antonacci et al. described an algal cytosensor designed for the electrochemical assessment of bacteria in wastewater using

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii attached to carbon black (CB) nano-modified screen-printed microelectrodes. CB nanoparticles, owing to their ability to sense oxygen generated via algae and resulting current, served as nano-modifiers (

Figure 4C). This sensor's capability was assessed for the detection of

E. coli in real wastewater samples, exhibiting a linear concentration range from 100 - 2000 CFU/100 mL [

63]. Sidhu et al. presented a microelectrode-based aptasensor on a platinum interdigitated electrode (IDE) for the identification of

Listeria spp. in hydroponic growth media. This sensor was integrated into a hydroponic lettuce system for particle or sediment trapping, facilitating real-time evaluation of irrigation water (

Figure 4D). Detailed electrochemical analysis was performed in the presence of Listeria spp. DNA, followed by calibration in various solutions. An aptasensor exhibited a 90% accuracy and could be reused several times after simple cleansing [

64].

Indeed, traditional methods for foodborne pathogen sensing, while sensitive, can often be tedious and time-consuming, which limits their practical utility. Therefore, the development of novel sensing assays for foodborne pathogens is crucial, as exemplified in

Figure 4A–D. Rapid detection of pathogens represents a promising approach in microfluidics-based biosensing through research and development efforts.

4. Advantages and challenges of multimodal biosensing

4.1. Enhanced sensitivity and specificity

Multimodal biosensing platforms provide numerous advantages, including enhanced sensitivity and specificity in detecting various analytes, including foodborne pathogens.

Liu et al. emphasize that multimodal biosensing platforms aim to achieve signal amplification, lower detection limits, and the ability to detect multiple targets. By combining different detection modalities, these platforms can enhance the specificity of detection, allowing for the sensing of analytes at lower concentrations. Specifically, they discuss the use of nanomaterial labeling in electrochemical immunosensors and immunoassays. The incorporation of nanomaterial labels, such as colloidal silver/gold, provides significant signal enhancement, enabling ultrasensitive electrochemical sensing of biothreat agents, infectious agents, and disease-related protein biomarkers [

66]. Xu et al. discuss microfluidics and its capability to manipulate the size, shape, and composition of particles, resulting in the production of monodisperse particles with an exceptionally narrow range of sizes. This precise control allows for enhanced sensitivity in biosensing applications [

67]. Siqueira et al. describe the incorporation of hybrid nanofilms on capacitive field-effect sensors, which can enhance the specificity of biosensors. Their study demonstrates that the incorporation of a hybrid urease-CNT nanofilm improves the output signal performance and sensitivity, enabling enhanced properties for urea detection [

68]. Kim et al. mention the use of plasmon-enhanced fluorescence in biosensing for sensitivity improvement. This strategy utilizes plasmonic nanostructures to enhance fluorescence signals, leading to improved sensitivity in biosensing applications [

69]. Chen et al. demonstrate the sensitivity enhancement achieved by using two-dimensional (2D) MXene in fiber optic biosensors. The metallic conductivity, high specific surface area, hydrophilic surface, and wide-band optical absorption of 2D MXene contribute to sensitivity enhancement in biosensing. They also support the sensitivity boost achieved by fiber optic biosensors through refractive index (RI) detection. Their study shows a significant sensitivity improvement in fiber optic RI sensors and fiber optic SPR sensors, which can be employed for the sensing of trace biochemical molecules [

70].

Najeeb et al. demonstrate the advantages of enhanced specificity and sensitivity in an electrochemical biosensor for the sensing of marine biological toxins [

71,

72]. Another study discusses how an electrochemical biosensor incorporating polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) as modifiers achieves enhanced sensitivity and specificity for the identification of saxitoxin [

73]. Furthermore, they highlight the advantages of label-free detection using a field-effect device-based biosensor for saxitoxin, emphasizing the enhanced sensitivity and specificity achieved [

72]. Yadav et al. discuss various plasmonic-based optical detection platforms, including SERS, SPR, and LSPR. These platforms offer excellent specificity, sensitivity, and ease of operation, making them advantageous for the early sensing of biomarkers of infectious diseases [

74]. Zargartalebi et al. introduce a novel approach for reagentless biosensing using the COVID-19 virus as a model target. The study demonstrates high sensitivity and rapid sensing achieved by integrating a coffee-ring phenomenon into a detection scheme, enabling target pre-concentration on a ring-shaped electrode [

75].

Multimodal biosensing platforms offer enhanced sensitivity and specificity through the integration of different detection modalities and the use of nanomaterial labels, microfluidics, hybrid nanofilms, MXene fibers, and plasmon-enhanced fluorescence. These platforms offer the detection of low-concentration analytes and provide a comprehensive and consistent approach to sensing various targets, including foodborne pathogens.

4.2. Improved analytical performance

Multimodal biosensing, driven by improved analytical performance, offers several advantages in the field of biosensing.

The integration of multiple modalities, such as microfluidics and biosensors, allows for enhanced analytical performance. Microfluidic systems provide precise control over fluid flow, enabling high-throughput processing, improved transport, and reduced sample and reagent volumes. This integration enhances sensitivity, accelerates the mixing of reagents, and enables the simultaneous analysis of multiple analytes within a single platform [

76]. Multimodal biosensing platforms enable multiplexed detection of multiple analytes. For example, Pappa et al. discussed the integration of an organic transistor array with finger-powered microfluidics for conducting multi-analyte saliva experiments. This platform offers the potential for noninvasive, multiplexed, and personalized point-of-care diagnostics [

77]. Sadabadi et al. reported a compact multi-analyte biosensing device consisting of an organic electrochemical transistor (OECT) microarray combined with a pumpless microfluidic system. This platform allows for the quantitative monitoring of lactate, glucose, and cholesterol levels [

76].

The incorporation of different transduction elements and biorecognition elements in multimodal biosensing platforms enhances the specificity of sensing. Pappa et al. discussed the use of a "blank electrode" in biosensing platforms to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio and sensitivity. By incorporating an additional OECT functionalized with an unspecific protein, background interference can be minimized, leading to improved specificity [

77]. Furthermore, multimodal biosensing platforms offer the advantages of disposability, portability, real-time sensing, and exceptional accuracy. These platforms have the potential to revolutionize point-of-care diagnostics, environmental monitoring, healthcare, and precision agriculture [

78].

Multimodal biosensing, driven by improved analytical performance, offers advantages such as enhanced sensitivity, multiplexed detection, improved specificity, and the ability to integrate (bio)chemical components into a single device. These advancements have the potential to transform various fields, including environmental monitoring, healthcare, and agriculture.

4.3. Minimization of false positives and negatives

Multimodal biosensing, focused on minimizing false positives and negatives, provides several advantages in various applications. One of the key benefits is the integration of different sensing modalities, such as magnetic and optical biosensing, into a single platform. This integration allows for the simultaneous detection of multiple analytes or the use of complementary techniques to enhance sensitivity and accuracy. For example, optical-magnetic multimodal bioprobes have been designed to overcome the limitations of single-modal probes, capitalizing on the unique electronic structures and magnetic and optical properties of lanthanide ions [

79]. Another advantage of multimodal biosensing is the potential for increased detection sensitivity and accuracy. By combining multiple sensing modalities, detection limits can be enhanced, enabling the identification of analytes at lower concentrations. This is particularly important in clinical diagnostics, where early detection of diseases or pathogens is crucial for effective treatment and prevention. Multimodal biosensing can also reduce false positive cases, improving the specificity of the detection [

5].

Multimodal biosensing devices can provide additional benefits in terms of responsiveness to various microenvironments and external stimuli. This flexibility allows for the recognition of analytes in complex samples or challenging conditions, enhancing the robustness and reliability of the biosensing system. Additionally, the use of biomimetic enzyme-like biosensing platforms can further enhance the performance of multimodal biosensors. These platforms mimic the catalytic activity of natural enzymes and can provide enhanced sensitivity and selectivity in detecting target analytes [

80].

In the field of medical imaging, multimodal biosensing also offers advantages. For example, the integration of optical and magnetic imaging techniques allows for improved imaging depth and resolution. Optical imaging techniques, such as up-conversion nanoparticles, offer high spatial resolution but limited imaging depth, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides large penetration depth but lower resolution. By combining these modalities, the advantages of both techniques can be leveraged to achieve detailed imaging of internal structures with improved depth and resolution [

79]. Multimodal biosensing, with a focus on minimizing false positives and negatives, offers several advantages in various applications. These advantages include the integration of different sensing modalities, increased detection sensitivity and accuracy, responsiveness to different microenvironments, and enhanced medical imaging capabilities. These qualities make multimodal biosensing a viable approach for a wide range of biosensing applications.

4.4. Challenges and limitations

4.4.1. Integration and Miniaturization

Integration and miniaturization are two key challenges in multimodal biosensing. The integration of different sensing modalities into a single platform requires careful consideration of the design and fabrication processes. This is significant for achieving portability, ease of use, and the ability to perform parallel, multiplexed, and automated studies. Integration also facilitates the incorporation of sensors and actuators with electronic experiment and measurement circuits, enabling seamless integration within a chip, package, or system [

81]. However, integrating multiple modalities can be complex and may require advanced fabrication techniques and materials [

82]. Miniaturization into the nanoscale is another challenge in multimodal biosensing. While miniaturization offers advantages like increased signal-to-noise ratio and improved sensitivity, there are trade-offs to consider. One trade-off is the longer time it takes to gather target analytes on the surface of a sensor owing to increased mass transport intervals. Careful consideration of signal transduction processes and reaction-transport kinetics is necessary to develop strategies that leverage miniaturization while maintaining minimal detection limits and immediate response times. Additionally, the choice of structure and device design, such as porous structures with a lower density of high pores, can impact a detection limit [

81].

The challenges of integration and miniaturization in multimodal biosensing are not limited to technical aspects but also extend to commercialization and practical implementation. Commercialization of biosensors faces challenges such as sample preparation, introduction of nanomaterials, comparison to other technologies, and development of multiplex portable biosensors with low-cost formats. The stability of immobilized receptors and the fabrication of high-complexity components are also important considerations for commercialization [

83]. Furthermore, the integration of microfluidics with multimodal biosensing systems presents additional challenges in terms of design, miniaturization, and compatibility with wearable devices [

84].

The challenges of integration and miniaturization in multimodal biosensing are multifaceted. They involve technical considerations in terms of design, fabrication, and signal transduction mechanisms, as well as practical challenges in commercialization and implementation. Overcoming these challenges requires interdisciplinary approaches, including materials science, chemistry, biology, and engineering. Addressing these challenges will enable the development of advanced multimodal biosensing platforms with enhanced sensitivity, accuracy, and practicality.

4.4.2. Cost and Scalability

The cost and scalability of multimodal biosensing present significant challenges in their implementation and practical use. One challenge is the cost of the development and production of multimodal biosensing platforms. The integration of multiple sensing modalities often requires sophisticated and specialized equipment, materials, and fabrication techniques, which can be expensive. Additionally, the use of advanced technologies, such as nanomaterials and microfluidics, can further increase the cost of multimodal biosensing. The high cost of development and production can limit the accessibility and widespread adoption of multimodal biosensing technologies, particularly in resource-limited settings [

83]. Scalability is another challenge in multimodal biosensing. As the number of sensing modalities or the complexity of the system increases, scalability becomes a critical consideration. Achieving scalability in multimodal biosensing requires efficient and scalable fabrication processes, as well as the ability to handle and analyze large volumes of data generated by multiple modalities [

85].

Furthermore, the scalability of multimodal biosensing is closely linked to the commercialization and practical implementation of these technologies. The advancement of cost-effective and scalable manufacturing processes is essential for the widespread adoption of multimodal biosensing platforms [

83]. In addition, the scalability of data analysis and interpretation methods is crucial for handling the large amounts of data generated by multiple modalities. Efficient algorithms and computational resources are needed to process and analyze the data in a timely manner, especially in real-time applications [

85]. The cost and scalability of multimodal biosensing pose significant challenges in their implementation and practical use. Overcoming these challenges requires advancements in cost-effective manufacturing techniques, efficient data analysis algorithms, and scalable infrastructure to support the implementation of multimodal biosensing in various applications.

5. Applications in foodborne pathogen detection

Multimodal biosensing techniques have shown great potential in improving the detection of pathogenic microorganisms

i.e. Salmonella,

E. coli, and

S. aureus [

86].

For instance, a multimode dot-filtration immunoassay (MDFIA) for rapid

Salmonella typhimurium detection was developed using MoS

2@Au complexes. MoS

2 served as a versatile antibody label, enhancing sensitivity through its intrinsic color, peroxidase-like activity, and photothermal effect. Immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane, the immune-MoS

2@Au complexes underwent visual qualitative analysis, showing color changes. The quantitative analysis utilized a complexes' photothermal effect, measuring temperature variation under laser irradiation.

Salmonella levels were quantified by correlating temperature variation with bacterial count logarithm. This method integrates visual and quantitative techniques, providing swift and accurate biosensing potential [

87].

Another study presents a sensitive

E. coli sensor featuring rapid response times, achieved through the immobilization of T4 bacteriophages on a multimode microfiber (MM). The MM, formed by tapering an optical fiber to micrometer dimensions under non-adiabatic conditions, allows for the excitation of fundamental and higher-order modes, creating mode interference primarily with HE

11 and HE

12 modes. By capturing

E. coli, the immobilized T4 bacteriophage induces changes in the refractive index of these modes. The sensor detects

E. coli concentration by monitoring shifts in the resonance wavelength of the mode interference spectrum, thereby offering a versatile and efficient method for

E. coli detection [

88].

Furthermore, Zheng et al. introduce a split-type multimodal biosensor for

S. aureus detection. Utilizing FePor-TPA's dual enzyme performance and photocurrent response, the biosensor operates in two modes. In the first mode, the 2D FePor-TPA thin film exhibits sensitive photocurrent and catalase activity, decomposing H

2O

2 to O

2. In the second mode, FePor-TPA shows excellent peroxidase activity, oxidizing TMB to oxTMB under acidic conditions. The biosensor offers a "signal-on" response, with increased targets generating more H

2O

2 and gluconic acid, enhancing sensitivity. The biosensor demonstrates high sensitivity and selectivity, making it a promising tool for

S. aureus detection [

89].

In conclusion, innovative biosensors have been developed for rapid detection of foodborne pathogens. The integration of MoS2@Au complexes in a multimode dot-filtration immunoassay enables swift and accurate Salmonella typhimurium detection, combining visual and quantitative analysis methods. Additionally, a versatile E. coli sensor utilizing T4 bacteriophages on a multimode microfiber offers efficient and adaptable E. coli detection based on mode interference. Furthermore, a split-type multimodal biosensor employing FePor-TPA demonstrates dual enzyme performance, achieving sensitive S. aureus detection through photocurrent and peroxidase activity. These advancements showcase the potential of multimodal biosensors for rapid and precise foodborne pathogen detection in diverse applications.

6. Future Perspectives

The integration of multiple biosensing strategies to enhance the accuracy, efficacy, and precision of foodborne pathogen detection holds great promise in shaping the future of biosensor technology. As research in multimodal biosensing for foodborne pathogens continues to evolve, several compelling future perspectives emerge. The field of nanotechnology is advancing rapidly, offering novel nanomaterials with enhanced properties for biosensing applications. Future developments in engineered nanoparticles, nanowires, and nanocomposites are expected to further improve the sensitivity and selectivity of integrated biosensing platforms. Microfluidic technologies are enabling the miniaturization and integration of multiple processes on a single chip, enhancing the efficiency of sample preparation, detection, and analysis. The synergy between microfluidics and multimodal biosensing will enable rapid and precise pathogen detection, even with limited sample volumes. The fusion of data from multiple biosensing techniques will require advanced data analysis algorithms. Machine learning, artificial intelligence, and pattern recognition methods will play a significant role in extracting meaningful information from complex multimodal biosensor data, leading to more accurate and reliable results. Future multimodal biosensors may find applications beyond the laboratory, allowing real-time examination of food products throughout the supply chain. These biosensors could be integrated into portable devices for on-site detection, enabling quick decision-making and intervention to prevent foodborne outbreaks. The development of modular and customizable biosensing platforms will empower researchers and industries to tailor integrated biosensors to specific pathogen detection needs. Such platforms would allow the integration of different biosensing techniques based on the target pathogen and sample matrix. Incorporating these advancements and perspectives into multimodal biosensing for foodborne pathogens holds the potential to revolutionize food safety practices, ensuring the timely detection and prevention of foodborne illnesses.

7. Conclusions

The convergence of various biosensing techniques into integrated multimodal platforms holds the promise to revolutionize foodborne pathogen detection. These advanced biosensors offer enhanced accuracy, efficacy, and precision, enabling earlier and more reliable identification of contaminants in food products. Through the synergistic combination of optical, electrochemical, nanomaterial-based, and other techniques, researchers and industries can address the limitations of single-mode biosensors and enhance the overall capabilities of pathogen detection. Integration of multiple biosensing strategies not only provides more comprehensive data about the target pathogens but also minimizes false positive and false negative results. Despite the challenges of integrating different sensing principles, the benefits of improved performance and reliability justify the efforts required. As nanotechnology, microfluidics, and data analysis methods continue to advance, the potential for future multimodal biosensors to become an indispensable tool in ensuring food safety and public health is immense. With continuous research and collaboration, multimodal biosensing opportunities for foodborne pathogens will shape the landscape of biosensor technology, contributing to safer food products, reduced outbreaks, and healthier communities. The journey towards these goals is marked by exciting advancements and a shared commitment to fostering innovation at the intersection of biosensing, nanotechnology, and public health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.D.; writing-original draft preparation, N.U.; Supervision, M.K.D.; Funding acquisition, M.K.D. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the NSF Grant (# 2130658) and The Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Department at The University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Scallan, E.; et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerging infectious diseases 2011, 17, 7. [CrossRef]

- Havelaar, A.H.; Kirk, M.D.; Torgerson, P.R.; Gibb, H.J.; Hald, T.; Lake, R.J.; Praet, N.; Bellinger, D.C.; de Silva, N.R.; Gargouri, N.; et al. World Health Organization Global Estimates and Regional Comparisons of the Burden of Foodborne Disease in 2010. PLOS Med. 2015, 12, e1001923. [CrossRef]

- Akil, L. Trends of Foodborne Diseases in Mississippi: Association with Racial and Economic Disparities. Diseases 2021, 9, 83. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lin, C.-W.; Wang, J.; Oh, D.H. Advances in Rapid Detection Methods for Foodborne Pathogens. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 297–312. [CrossRef]

- Lukose, J.; Barik, A.K.; N, M.; M, S.P.; George, S.D.; Murukeshan, V.M.; Chidangil, S. Raman spectroscopy for viral diagnostics. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 199–221. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Advances in the Bacteriophage-Based Precise Identification and Magnetic Relaxation Switch Sensor for Rapid Detection of Foodborne Pathogens, in Foodborne Pathogens-Recent Advances in Control and Detection. 2022, IntechOpen.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X. Molecular imprinting technology for sensing foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 4581–4598. [CrossRef]

- Homola, J. Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors for Detection of Chemical and Biological Species. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 462–493. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; He, J.; Yang, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Xiao, S.; Huang, B.; Yuan, Y.; Sheng, Q.; Yue, T. Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based Sensing for Food Safety Analysis. Processes 2022, 10, 2576. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Belwal, T.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, Z. Nanomaterial-based biosensors for sensing key foodborne pathogens: Advances from recent decades. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1465–1487. [CrossRef]

- Bobrinetskiy, I.; Radovic, M.; Rizzotto, F.; Vizzini, P.; Jaric, S.; Pavlovic, Z.; Radonic, V.; Nikolic, M.V.; Vidic, J. Advances in Nanomaterials-Based Electrochemical Biosensors for Foodborne Pathogen Detection. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2700. [CrossRef]

- Gloag, L.; Mehdipour, M.; Chen, D.; Tilley, R.D.; Gooding, J.J. Advances in the Application of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Sensing. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1904385. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Qi, Q.; Wang, C.; Qian, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors for food allergen detection in food matrices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 142, 111449. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Knoll, W.; Dostalek, J. Bacterial Pathogen Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor Advanced by Long Range Surface Plasmons and Magnetic Nanoparticle Assays. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 8345–8350. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., W. Knoll, and J. Dostalek. Long range surface plasmon resonance bacterial pathogen biosensor with magnetic nanoparticle assay. in 2011 International Workshop on Biophotonics. 2011. IEEE.

- Bhandari, D.; Chen, F.-C.; Bridgman, R.C. Magnetic Nanoparticles Enhanced Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for Rapid Detection of Salmonella Typhimurium in Romaine Lettuce. Sensors 2022, 22, 475. [CrossRef]

- Balbinot, S.; et al. Plasmonic biosensors for food control. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 111, 128-140. [CrossRef]

- Atay, E.; Altan, A. Nanomaterial interfaces designed with different biorecognition elements for biosensing of key foodborne pathogens. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 3151–3184. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, L.; Ho, P.; Mak, G.C.; Gu, H.; Xu, B. Combining Fluorescent Probes and Biofunctional Magnetic Nanoparticles for Rapid Detection of Bacteria in Human Blood. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 3145–3148. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Xu, Z. Detection of Foodborne Pathogens by Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1236. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.; Yu, Z.; Lu, X. Application of Raman Spectroscopic Methods in Food Safety: A Review. Biosensors 2021, 11, 187. [CrossRef]

- Xing, G.; Sun, X.; Li, N.; Li, X.; Wu, T.; Wang, F. New Advances in Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFI) Technology for Food Safety Detection. Molecules 2022, 27, 6596. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Hua, T.; Guo, R.; Miao, D.; Jiang, S. Flexible, stable and sensitive surface-enhanced Raman scattering of graphite/titanium-cotton substrate for conformal rapid food safety detection. Cellulose 2019, 27, 941–954. [CrossRef]

- Mi, F.; Hu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Peng, F.; Geng, P.; Guan, M. Recent advancements in microfluidic chip biosensor detection of foodborne pathogenic bacteria: a review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 2883–2902. [CrossRef]

- Law, J.W.-F.; Ab Mutalib, N.-S.; Chan, K.-G.; Lee, L.-H. Rapid methods for the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens: principles, applications, advantages and limitations. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 770. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hindi, R.R.; Teklemariam, A.D.; Alharbi, M.G.; Alotibi, I.; Azhari, S.A.; Qadri, I.; Alamri, T.; Harakeh, S.; Applegate, B.M.; Bhunia, A.K. Bacteriophage-Based Biosensors: A Platform for Detection of Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens from Food and Environment. Biosensors 2022, 12, 905. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cui, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Bin, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y. Advances in Electrochemical Aptamer Biosensors for the Detection of Food-borne Pathogenic Bacteria. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202202190. [CrossRef]

- McGrath, T.F.; Elliott, C.T.; Fodey, T.L. Biosensors for the analysis of microbiological and chemical contaminants in food. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 403, 75–92. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Musameh, M. Carbon Nanotube/Teflon Composite Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 2075–2079. [CrossRef]

- Quintela, I.A.; Wu, V.C.H. A sandwich-type bacteriophage-based amperometric biosensor for the detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serogroups in complex matrices. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 35765–35775. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; An, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Hasan, M. Advances in Fluorescent Sensing Carbon Dots: An Account of Food Analysis. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 9031–9039. [CrossRef]

- Sabui, P.; Mallick, S.; Singh, K.R.; Natarajan, A.; Verma, R.; Singh, J.; Singh, R.P. Potentialities of fluorescent carbon nanomaterials as sensor for food analysis. Luminescence 2022, 38, 1047–1063. [CrossRef]

- Ab Rashid, S.; Rosli, N.S.M.; Teo, S.H.; Tong, W.Y.; Leong, C.R.; Yusof, F.A.M.; Tan, W.-N. Naringenin-Grafted Polyvinyl Alcohol (Na/PVA) Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterisation and in vitro Evaluation of Its Antimicrobial Efficiency on Fresh Beef. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2022, 33, 143–161. [CrossRef]

- Sistani, S. and H. Shekarchizadeh, Applications of Quantum Dots in the Food Industry, in Quantum Dots-Recent Advances, New Perspectives and Contemporary Applications. 2022, IntechOpen.

- Mocan, T.; Matea, C.T.; Pop, T.; Mosteanu, O.; Buzoianu, A.D.; Puia, C.; Iancu, C.; Mocan, L. Development of nanoparticle-based optical sensors for pathogenic bacterial detection. J. Nanobiotechnology 2017, 15, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Somavarapu, S., et al., Nanotechnology-A New Frontier in Medical Microbiology. Nanotechnology for Advances in Medical Microbiology, 2021: p. 375-392.

- Cui, Y.; Wei, Q.; Park, H.; Lieber, C.M. Nanowire Nanosensors for Highly Sensitive and Selective Detection of Biological and Chemical Species. Science 2001, 293, 1289–1292. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; et al. Composite-Scattering Plasmonic Nanoprobes for Label-Free, Quantitative Biomolecular Sensing. Small 2019, 15, 1901165.

- Stern, E.; Klemic, J.F.; Routenberg, D.A.; Wyrembak, P.N.; Turner-Evans, D.B.; Hamilton, A.D.; LaVan, D.A.; Fahmy, T.M.; Reed, M.A. Label-free immunodetection with CMOS-compatible semiconducting nanowires. Nature 2007, 445, 519–522. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hwang, H.-M. Nanotechnology in food science: Functionality, applicability, and safety assessment. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 671–681. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; et al. Rationally Designed Dual-Mesoporous Transition Metal Oxides/Noble Metal Nanocomposites for Fabrication of Gas Sensors in Real-Time Detection of 3-Hydroxy-2-Butanone Biomarker. Advanced Functional Materials 2022, 32, 2107439. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Xue, L.; Zhang, H.; Guo, R.; Li, Y.; Liao, M.; Wang, M.; Lin, J. An enzyme-free biosensor for sensitive detection of Salmonella using curcumin as signal reporter and click chemistry for signal amplification. Theranostics 2018, 8, 6263–6273. [CrossRef]

- Sackmann, E.K.; Fulton, A.L.; Beebe, D.J. The present and future role of microfluidics in biomedical research. Nature 2014, 507, 181–189. [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.D.; Linder, V.; Sia, S.K. Commercialization of microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic devices. Lab Chip 2012, 12, 2118–2134. [CrossRef]

- Whitesides, G.M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 2006, 442, 368–373. [CrossRef]

- Kaaliveetil, S.; Yang, J.; Alssaidy, S.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Menon, N.H.; Chande, C.; Basuray, S. Microfluidic Gas Sensors: Detection Principle and Applications. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1716. [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.; Vijayan, A.N.; Joseph, K. Cysteine capped gold nanoparticles for naked eye detection of E. coli bacteria in UTI patients. Sens. Bio-Sensing Res. 2015, 5, 33–36. [CrossRef]

- Sepunaru, L.; Tschulik, K.; Batchelor-McAuley, C.; Gavish, R.; Compton, R.G. Electrochemical detection of single E. coli bacteria labeled with silver nanoparticles. Biomater. Sci. 2015, 3, 816–820. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Duan, N.; Shi, Z.; Fang, C.; Wang, Z. Simultaneous Aptasensor for Multiplex Pathogenic Bacteria Detection Based on Multicolor Upconversion Nanoparticles Labels. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 3100–3107. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; et al. ZnO-based amperometric enzyme biosensors. Sensors 2010, 10, 1216-1231.

- Gheorghiu, M.; Polonschii, C.; Popescu, O.; Gheorghiu, E. Advanced Optogenetic-Based Biosensing and Related Biomaterials. Materials 2021, 14, 4151. [CrossRef]

- Syahir, A., H. Mihara, and K. Kajikawa, A new optical label-free biosensing platform based on a metal− insulator− metal structure. Langmuir 2010, 26, 6053-6057. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chapman, R.; Stevens, M.M. Label-Free Multimodal Protease Detection Based on Protein/Perylene Dye Coassembly and Enzyme-Triggered Disassembly. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 6410–6417. [CrossRef]

- Juan-Colás, J.; Johnson, S.; Krauss, T.F. Dual-Mode Electro-Optical Techniques for Biosensing Applications: A Review. Sensors 2017, 17, 2047. [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Dutta, H.S.; Gogoi, S.; Devi, R.; Khan, R. Nanostructured MoS2-Based Advanced Biosensors: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2017, 1, 2–25. [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Kumeria, T.; Losic, D. Nanoporous Anodic Alumina: A Versatile Platform for Optical Biosensors. Materials 2014, 7, 4297–4320. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W. Nanomaterials in fluorescence-based biosensing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 394, 47–59. [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, C.; Wu, S.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; Yang, B.; Qiu, S.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Zeng, H.; et al. Development of a lateral flow colloidal gold immunoassay strip for the simultaneous detection of Shigella boydii and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in bread, milk and jelly samples. Food Control. 2016, 59, 345–351. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ma, B.; Li, J.; Chen, E.; Xu, Y.; Yu, X.; Sun, C.; Zhang, M. A Rapid and Sensitive Europium Nanoparticle-Based Lateral Flow Immunoassay Combined with Recombinase Polymerase Amplification for Simultaneous Detection of Three Food-Borne Pathogens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 4574. [CrossRef]

- Zahertar, S.; Wang, Y.; Tao, R.; Xie, J.; Fu, Y.Q.; Torun, H. A fully integrated biosensing platform combining acoustofluidics and electromagnetic metamaterials. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2019, 52, 485004. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Pilloton, R.; Jain, S.; Roy, S.; Khanuja, M.; Mathur, A.; Narang, J. Paper-Based Electrodes Conjugated with Tungsten Disulfide Nanostructure and Aptamer for Impedimetric Detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Biosensors 2022, 12, 88. [CrossRef]