1. Introduction

It is widely recognized that physical systems can express their matter aggregation involving properties if they are formed distinctly either in low-temperature (quantum prone; towards crystal formation) or in high-temperature (classically meant, with amorphization effects included) limits. It is expected that an intriguing physical scenario appears at the borderline, namely at a passage between quantum and classical expositions, which is often seen when exploring a multitude of (functional) structures possessing an involvement of the so-called granules or molecular (dis)orderly tiny aggregates of versatile types. For example, polymer granules is a long, repeating chains of atoms, formed through the linkage of many molecules called monomers. The monomers can be identical, or they can have one or more substituted chemical groups. Of course, these differences between monomers can affect granules’ properties such as solubility, flexibility, or mechanical stability [

1,

2].

It is commonly accepted that controlling the size and shape of nanoparticles is a challenging issue. Even though there is no external load applied on a nanoparticle or on an ensemble of very small crystals, such as the quantum dots, their internal parts experience an appreciable surface stress that compensates for the corresponding capillary forces. Such a physical scenario also often shows up in colloidal self-assembly systems, especially those devoted to yielding special-purpose (soluble) nanocrystals employed in biomedical, cosmetical, and biomaterials science addressing applications. Functional nanocrystalline materials, made up of tiny and orderly granules, which one may name grains or crystallites, can also be mentioned in this circumstance [

3,

4].

There is no doubt, that a challenging task emerges on a quite general level, namely, how to extract from a given, often viscoelastic nucleation-growth framework [

2], reliable control of the size and shape of nanoparticles/nanocrystals, especially if the size of the objects is blurred solely in the nanoscale, i.e. in a typical range of about

1-100 nm. As one may expect, at low temperatures and in the lower part of the distance range of a few nanometers some quantum effects can be uncovered too. But at the same size range, even in the room temperature limit or for water at a bit lower temperature value (at about

277 K rendering a water drop denser than in room- and/or physiological temperatures), a certain creation of bonds is feasible. However, any creation of bonds when treated non-statistically, for example, when recalling the reactive collisions theory, ought to be described with the help of a quantum-mechanical framework [

4,

5].

In the following, we would like to introduce a mesoscopic, entropy-production model of a

d-dimensional (soft) material formation based on the very basic rules of the evolution of grains- or granules-containing systems, wherein the granule’s volume stands for a stochastic variable (

x), see [

6], and refs. therein. The material system addressed is supposed to reside close to the local thermodynamic equilibrium, eventually leaving it for the neighboring one. The change of local equilibria is eventually driven by the capillary forces (Kelvin-Laplace law), albeit the process is not entirely deterministic because it is also driven by matter diffusion through the subsequent (soft) grain boundaries [

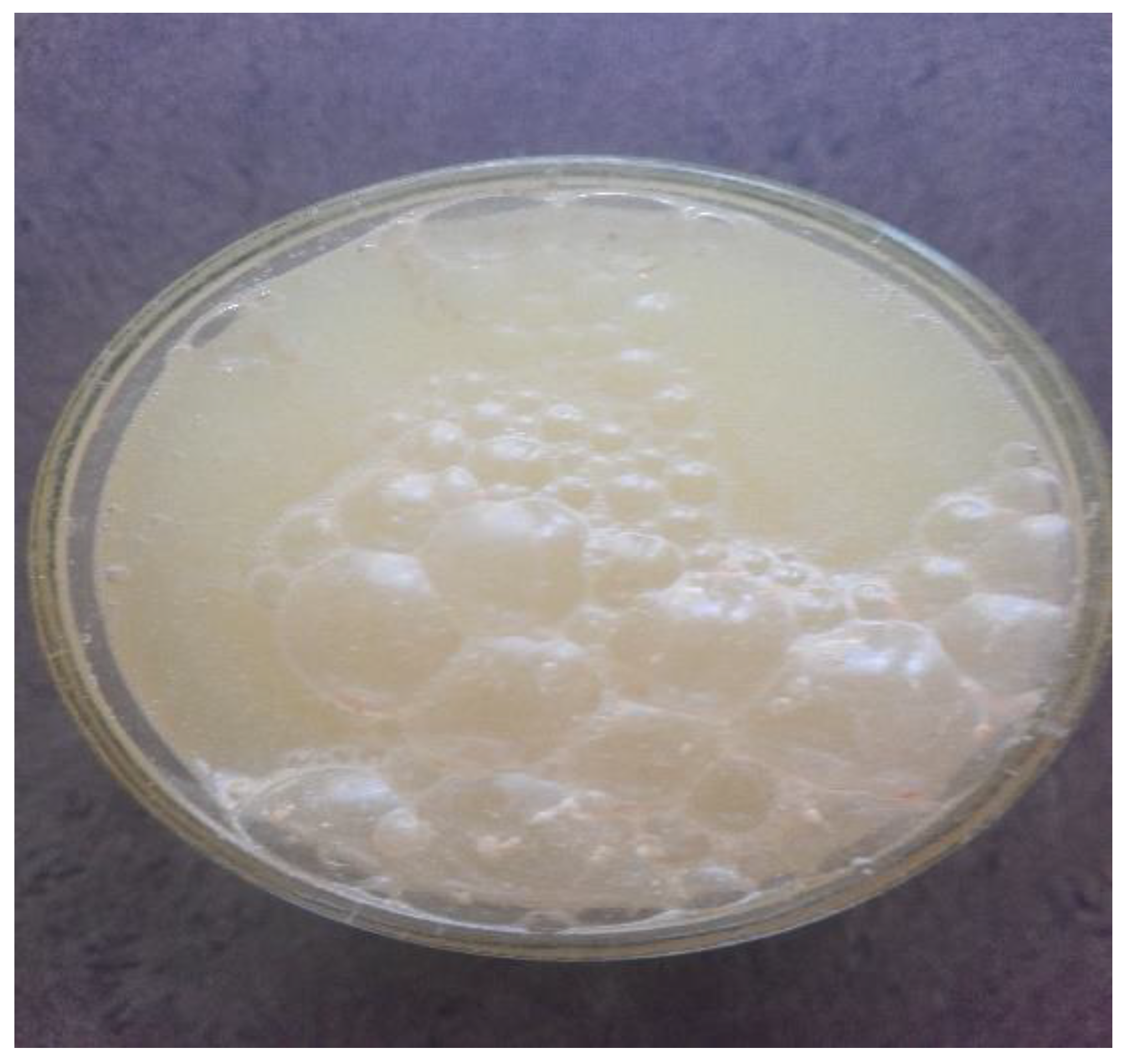

7]. Qualitatively and on a (crude) macroscopic scale, the process of interest is supposed to be reminiscent of a bubbles-containing formation, see

Figure 1.

In one of the recent previous studies, we have confined ourselves to a relevant circumstance, namely, we have directed our efforts towards quantum wires and very low-dimensional nano-objects, as well as nanofibrils formations, reaching ultimately the space dimension

d=1. As a consequence, our system has been assumed to be of the negligible role played in it typically by the surface tension. In turn, to keep the needle-shaped system as a whole we have assumed that the Van der Waals attraction ought to be at play while creating the structure; virtually, the electrostatic Coulomb/dipolar attraction can be of favor too. On the other hand, it qualitatively looks like we would efficiently confine to a line (or a chain) of a granules-containing system or the like [

8,

2].

In the current study, we would like to take advantage of the full

d-dimensional matter aggregation case published elsewhere [

9,

10,

11,

12], but this time we explore thoroughly the

x-dependent (state-dependent) diffusion function of the aggregation in the algebraic (scalable) form of

with

where α is a characteristic surface-to-volume exponent,

represents a diffusion constant (typically of the order of

), and

x mimics the (hyper)volume of the granule; for

x=v and

d=3, one would provide, for example, a sphere’s volume

v=(4π/3). Note that

applies here, thus, the sphere’s surface clearly becomes

s=4π For the purpose of this study, it is worth noting that the range of the linear size (radius)

r is from sub-millimeters to nanometers. (In general, the characteristic exponent α represents a generically colloidal nature of the mesoscopic aggregation.)

In the present study, we would like to focus on the following subject matter. First, in contrast to the considerations developed in [

8] we are going to explore in full the

d-dimensional picture of the aggregation [

6,

12]. Second, we wish to go a step further with the previously touched-upon stochastic quantization procedure applied to diffusion-type systems [

8], proposed originally in terms of a quantum-classical crossover in critical dynamics, allowing to convert the diffusion-type equation to a Schrödinger’s equation (at first, in the imaginary time domain). It is possible to get if the diffusion coefficient is proportional to Planck’s constant

h [

13]. In the limit of

h going to zero, i.e. while escaping from the respective quantum domain, the (soft) material evolution in

x-space would attain a low-valued ‘subdiffusive’ (and, otherwise non-quantum) mode, nearly causing to trap the atoms or molecules absorbed by any of the adjacent granules [

1,

2].

However, an appreciable novelty of the current study is thought of to be a Heisenberg-type diffusional relation coming out from a suitable redefinition of Equation (1), qualitatively in accord with what has been proposed in [

13,

14,

15]. This redefinition along with an exploration of its consequences (i.e., toward quantum-size effect [

4,

16]), resulting in the classical-quantum passage of the aggregation, will be presented in section 3.

The paper is organized as follows. In section 2, a mesoscopic model for a

d-dimensional (soft) material formation in nonequilibrium-thermodynamic conditions is introduced [

12], while in section 3 classical-quantum crossover of the

d-dimensional (nano)granules involving formation, involving the offered granule-size (

r) dependent Heisenberg-type diffusional relation is unveiled.

Section 4 will contain a concluding address.

2. Mesoscopic model for a granules-containing mesoscopic formation in nonequilibrium thermodynamic conditions

Certain selected examples of some types of macro-granules involving matter have been presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. Of course, they are of very qualitative, and above all, of exclusively macroscopic, also demonstrative, everyday character – an equivalent of the granule can be here either a bubble or some liquid egg, or finally, a piece of wood, thus in fact, a real granular system [

17]. What they, however, demonstrate in common, is that they are supposed to be closed-packed structures, cf. [

7]. We will refer to the close-packing conditions in dimension

d but for meso- and nanoscopic matter aggregations in the subsequent sections/rationale. (Our tacit assumption for the rest of the paper’s content will be the matter-aggregation statistical scalability, cf. [6, 9,10,12].)

From now on, however, let us introduce in short a model of the so-called normal grain growth [

9,

10,

2] that is based on the physical assumption that the system is conservative, which means that

is proposed. To complete the problem presented in Equations (3)-(4) one has to prescribe the initial and boundary conditions, abbreviated by IBCs; the so-called delta-Dirac and absorbing IBCs can be found elsewhere [

9,

10].

As anticipated in the preceding section, a decomposition of the aggregating matter flux

J(

x,t) into two main contributions [

1,

12]

ought to be assured as a signature of colloid-type systems, namely, a surface tension involving the non-gradient part (involving implicitly the Kelvin-Laplace pressure term [

2]) and its diffusion-type gradient-including counterpart. Bear in mind that

σ and

Do are surface tension and diffusion reference (temperature-dependent) parameters, respectively. The (skew) distribution

f(

x,t) represents the probability density of finding the respective grain of size

x at time

t; cf. [

6] and refs. Therein. The characteristic exponent α reads (cf. Equation (2))

where

d – Euclidean space dimension (

d = 1,2,3 …). Realize that if

d = 1 then

α = 0, and in Equation (4) the diffusion-type term becomes classically defined with a constant

Do. Be aware of the fact that non-integer values of

d>1 are not excluded a priori, albeit another non-integer-value involving approach has been offered so far [

1]. By virtue of it, the factor preceding the gradient of

f(

x,

t) becomes

x-independent, This phenomenological (

d=1)-model, invented for the physical-metallurgical grains-containing system, evolving diffusively in the so-called normal grain-growth conditions (recall the mention on IBCs above) is an entropy-production model [

8].

But the

x-independence is not the case of

d>1. This is because the line- and surface tension do influence the granules' state-dependent evolution driven by Equations (3) and (4) with the corresponding IBCs [

2]; cf.

Figure 1.

According to [

7] it can be presented (cf., Equation (4)) in dimension

d, in terms of the entropy production, if the matter flux is written as [

11]

in which case the only difference, when comparing Equations (4) and (6), is that there is a free energy gradient

, which implies that the coefficient (mobility)

, with

L(

x) – an Onsager’s coefficient, see [

1] for comparison. The most important physical fact [

11] appears to be here that

b(

x) is inversely proportional to the local temperature

T, thus, for the high-temperature limit the non-diffusive term, given by the free energy gradient (

), irrespective of the role played by dimension

d, vanishes. Thus, the evolution of granules is essentially based on the matter flux

with

, which implies the independence (of the kinetics) of the state variable

x. Obviously, the evolution of the

d=1-material system remains conservative, in accord with Equation (3) for α=0, which is equivalent to

d=1, cf. Equation (2) or (5). This can virtually be the case of the formations of quantum wires during a molecular beam (hetero)epitaxy process, or similarly, when by the same nanotechnology an emergence of nanorods proves to be efficient, or some nanofibrils, and their bundles emerge as one-dimensional quantum materials [

8,

19], expressing the quantum-size effect but exclusively for

d>1, especially if

d=3 appears to be the case of relevance [

16,

18].

3. Nanoscale classical vs. quantum limit of the d=3-dimensional granules involving formation: construction of the diffusion function

As we have already pointed out, we are interested in the matter aggregation case for higher dimensions (

d>1) but with in-parallel stepping down toward nanoscale linear dimensions of

r-s, the radii of the granules/domains. Therefore, it is easy to see that the examples presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 are of a crude and qualitative connotation, only. They can, however, strengthen our intuition at least in terms of close-packing (bio)material conditions. More subtle examples of, e.g. microfibrils in natural systems (cornea; embryos), basically detectable by light microscopy, one can take from [

20,

21].

To take an appreciable advantage of the preannounced close-packing conditions based on our matter aggregation model, one has to resort to the evaluation of the statistical moments of the distribution

f(x,t) [

2] (as denoted by

) obeying the set of equations (3)-(5) with the IBCs, and

x-dependent diffusion function

D(x), Equation (1). Evaluation of the statistical moments

for

n=1, which is equivalent to get the total system volume

V [

22] conserved,

V=const., leads also through

to a type of subdiffusive late-time (

t) structural behavior

wherein the ensemble average

(asymptotically) stands the average number of granules in the conservative system (1) with (3)-(5). It is acceptable that

, cf. Equation (8), being different from the fluctuation

growing a bit faster (in accord with a temporal change of the specific volume of the aggregate) than the quantity in (8), mimicking the (averaged) area of the granule which develops in time subdiffusively for

d>1. For an analogy, one can consult [

22] (see refs. therein too), in which a peculiar percolation-assisted construction of the mean-squared displacement in the space of

x-sizes, and in analogue to Equation (8), has been offered based on the (bare) structure-property argumentation. Notice that the super-dimension

d+1 embodied in (8) is a quantitative signature of the close-packing measure [

7], indicative of a minimal

d-dimensional neighborhood of any selected grain/granule of interest.

However, for the quantum -size effect [

16,

18] a more clear, thus sophisticated, procedure is desired. It can be proposed, based on the same averaging as above

, see ref. [

2] for details, by introducing the generalized diffusion coefficient of the (bio)material formation

with the characteristic colloid-type exponent

. By making use of the geometrical similarity relation

x (for the granule’s hypervolume) one is able, when plugging in it Equation (2) or (5), and performing the differentiation over time

t, that

which holds true for

d=3 or

. (Realize that relation (9) does not contain any information about the shape of the granules; the shape factor is assumed to be quantitatively of order of one, being at the same time a dimensionless parameter, e.g. 4π/3.) Defining the diffusion coefficient

one is capable of providing the following Heisenberg-type diffusive relation

thus, in the

r-space, meaning, in the space of the (round) granules’ sizes. To our knowledge, it is a novelty and virtually, a useful and practical tool for the quantum-size effect aggregations in question.

It is conjectured by the present feature study that if the radius (or, a linear granule’s size)

r is placed in the nanometer-scale range of (upper) order of

then by assuming

and accepting

well above an initial time (fairly close to stationarity), one can get

. It is still within the proper range of diffusion coefficient’s values, for example, for semiconductors, when Ga atoms perform diffusional motion along GaAs

(001) plane [

23].

What we have achieved so far for striving to disclose the quantum-size effect, pertinent mostly to tiny nanoscale formations [

16], is that Equation (10) can be tested readily against its quantum Heisenberg-type expression. It can formally be performed thanks to a quantization procedure in which a profound analogy between quantum fluctuations and Brownian motion is addressed, proposed by Fürth [

13] in the early nineteen thirties, and elaborated by Nelson in the nineteen sixties of the past century [

14], and later, by Ruggiero and Zanetti [

15]. In this procedure a derivation of Schrödinger’s equation can essentially be obtained from the Newton-Langevin type dynamics, with an aid of associated Ornstein-Uhlenbeck noise, playing a role of the external medium acting on the system’s dynamics [

14]. From Fürth-Nelson quantization procedure [

13,

14], also well elaborated in [

15], it turns out that the diffusion coefficient included in Equation (10) gives rise to the similarity relation, namely

if one makes use of an effective analogy between the random walk in

x-space of granules’ sizes (quantum-size effect) and that of conventional (for Brownian particles) space coordinates (

d>1) [

22,

24];

r belongs to the nanometer scale,

r[nm] in Equation (11). Of course, the Planck’s constant,

h, viewed in terms of action (formally, Joule times second), is known as a very small quantity. It is also well-accepted that converting the evolving system to the classical limit means that

would apply, which is pretty well consistent with the meaning of Equation (11), with very small diffusion-coefficient values [

23]. The ratio of h/m from Equation (12) below, is expressed in diffusion-coefficient units, i.e. in

, see discussion below Equation(2) or that presented after Equation (10).

To exploit the size vs. space position analogy [

22] in full, let us provide the appropriate well-known expression for

which is derived in [

13,

14] for a diffusing particle/granule of an average mass

μ. (Realize that complete methods of solution for stochastic-classical and quantum Fokker-Planck equations have been offered by [

24,

25].) The diffusing particle in our physical circumstance is the growing granule that is expanding in the atomic mass, and upon the stationarity limit of the uptake with saturation effect when a granule is ultimately being created by addition of atoms or molecules [

1,

22]. Another interesting physical nanosystem would be when nanobubbles in organic/inorganic monolayers are formed in the regime of negligible surface-tension [

26], thus, presumably along with the action of diffusive dynamics in

d>1 [

25], Equation (7); cf. Figure (1) for a certain macroscopic outlook. But looking at the impact of Equation (12) on the stationary- or late-time (saturation) limit of the essentially subdiffusive process (with a very slowly decreasing value of the diffusion coefficient) one would come to a firm quantitative conclusion that for a small-cluster (granule) mass of order of

10-24 kg (tens to hundreds of Ga atoms), one arrives at

of the above indicated values in the range of the semiconductor-characteristic (GaAs) diffusion coefficients [

23], cf. some values listed after Equation (10).

4. Concluding address

The following conclusions can be juxtaposed as follows:

- (1)

-The mesoscopic (principal) model offered here is essentially structureless: The only “structure” that is involved is given by the surface-to-volume (colloid-type) exponent, Equation (2) or (5), but the statistical features of the Fokker-Planck and Smoluchowski type of the subsequent aggregational, dimension-dependent dynamics (Equations (3)-(5)) give rise to its useful very peculiar properties;

- (2)

-From these dynamics, in particular for

d=3 for which Equation (1) does express its diffusion-structural behavior, it follows that the classical stochastic (diffusional) dynamics are able to meet their near quantum Heisenberg-type counterpart, contributing thoroughly to the corresponding quantum-size effect [

16], thus to obeying Equations (9)-(12);

- (3)

-It turns out that even though the mesoscopic matter aggregations do not provide any versatile structural impact, they are robust enough within the surface or interface realm of action to give rise to an efficient numerical and computer-simulational investigation toward atomic detail of what is inside the granules in terms of their corresponding subtle mechano-chemical stability, their internal strength and compactness (prospectively, pointing to their functionalities and complexities, as partly uncoverable by means of numerical and simulational methods), and the like [

20,

21].

It is always to warn someone’s awareness here that, in general, an elementary entropy change (at a given temperature

T) of the aggregation, designated by

as addressed by [

7], depends on the chemical potential of the system

µ(

x,

t), which in turn, must depend upon the elementary free system’s energy release, and a chemical affinity [

11]. (Note that for

T-

s high enough one would effectively attain

δS = 0, thus, the thermodynamic equilibrium.) We are of the opinion that we have to unveil

as a useful cause of the energy win by the physical entities such as atoms or molecules as being absorbed (also, adsorbed and/or chemically bonded) by their adjacent virtually (target-like) counterparts. In this way, for example, an effective nonequilibrium

d>1-structure (quantum dots) can emerge, and repetitive realization of

µ(

x,

t) would rest upon the above sketched energy-gaining and the entities’ exchange elementary process. The chemical affinity, in turn, should be realized possibly by means of a respective bonding, for example an

H-bonding, as mentioned in [

2,

4].