1. Introduction

Platelets are among the first cells to respond to an infection, monitor the integrity of the endothelium, initiate the inflammatory-immune and tissue repair process leading to sterilization of the infectious focus[

1]. Patients with COVID-19 have coagulation and platelet disorders, and although they have an average higher platelet count than subjects with forms of Acute distress Respiratiry Sindrome (ARDS) not associated with SARS-CoV-2[

2], in the subgroups that develop thrombocytopenia, the latter represents a negative prognostic parameter being associated with severe forms of the disease and an increase in lethality [

3,

4].

The innate immune response is a key issue to act as the first line of defense against many viral infection[

5]. The key innate immune sensing receptors are germ line-encoded pattern-recognitionreceptors (PRRs), which mediate the initial sensing of infection by recognition of PAMPs(pathogen-associated molecular patterns), upon microbial invasion of the host[

6]PRRs belong to different families, including Toll-like-receptors (TLRs).

TLRs are used by immune cells to recognize pathogens. There are some studies have shown that platelets express a variety of receptors, some of which are involvedin platelet activation, platelet–leucocyte reciprocal activation, immunopathology,and platelet-dependent antimicrobial activity, including the TLR family [

7,

8]

Innate immunity is primarily mediated by macrophages and neutrophils. These immune cells distinguish between pathogen and self by utilizing signals from TLRs. Stimulation of TLRs results in nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) and Mitaogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway activation, leading to the production of proinflammatory cytokines [

9].

TLR2 and TLR4 are the main receptors associated with platelet production/function andinflammation in the TLR family [

10].

The specific role of TLR-2 in the mechanisms of microvascular thrombosis observed during severe cases of COVID-19 disease. All three components of Virchow’s triad (endothelial injury, stasis and a hypercoagulable state)as recently reviewed by Wadowski PP et al [

11].

After sensing of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, TLR-2 dimerizes with TLR-1 or TLR6- and activates the proinflammatory NF-κB pathway [

12].

Studies from hyperlipidemia have shown that TLR2 pathway promotes platelet hyper-activation and thrombosis [

13].

Important studies in current literature have demonstrated that Pathogen Recognition by TLR-2 activates weibel-palade body exocytosis from endothelial cells [

14]and from alpha granules in platelets/megakaryocytes [

15,

16]. Furthermore, vWF has a central role in microthrombosis formation during COVID-19 [

17].

Megakaryocytes have TLRs, Tumor Necrosis Factor receptors (TNFR1 and 2), receptors for IL-1β and IL-6. All these receptors are involved in the activation of the pathway of NF-kB. NF-kB induces both inflammatory and thrombotic response [

18].

Platelets have many TLRs on their cell membrane, including TLR-4. Binding of microorganism (virus, bacteria, fungi, ecc) to TLR-4 induces platelets activation and release of their granule content (many factors involved in different processes)[

18].

In this study we have analyzed the immunohistochemical expression of TLR2 and CD61 in the specimens derived from autopsy procedures of patients died from critical SARS-CoV-2 infection, in order to potentially associate innate immune hyperinflammation with monocyte-macrophage up-regulation and microthrombosis mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval. The study was conducted according to the guide-lines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Attorney’s Office of Naples, protocol number p.p. 509568/020/44, dated May 15, 2020.

Clinicopathological data of selected patients.The group of patients that constituited our study has already been presented in our previous paper, in which we have investigated the role of Toll-Like receptor-4 in macrophage imbalance in lethal COVID 19 lung disease [

19]. The characteristics of this group are summarized in the

table 1.

Autopsy cases were been collected between June 2020 and July 2021 at time of wild-type SARS-CoV-2 with early onset of Epsilon and Alpha variants[

20] .

Patients deceased in a mean interval between diagnosis and death of 62.52 days (minimum of 20 days, maximum 120 days).

Autopsy protocol. Deceased patients underwent autopsy, through help of a ventilation system with six complete air changes/h (ACH) in a pressure-negative environment, with air exhausted through HEPA filters [Biosafety Level 3 (BSL3)], according to the University of Padova autopsy protocol[

21,

22].

Specimens of lung tissue from 25 patients deceased for SARS-CoV2 were been used as representative cases of COVID-19 lethal ARDS.

Methods. Immunohistochemical analysis has been performed on formalin-fixed paraffin embedded specimens derived from autopsy procedures (COVID-19-

(+) cohort), and from routine lung surgical operations (COVID-19-

(-) cohort). Single immunostaining has been performed using specific monoclonal antibodies against CD61 (clone 2F2) and TLR-2 (rabit policlonal), revealed by standard linked-streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase technique (LSAB), developed by 5’diaminobenzidine and/or alkaline phosphatase methods (

Table 2).

Evaluation was been performed by two blinded observers analyzing standard High Power Field (HPF) area, with 20X magnification, measuring 45508.61 µm

2. At least eight HPFs were been evaluated for a mean total area of 1160000 µm

2. Antibodies used and experimental conditions have been reported in

table 3.

The percentage of positive immunostained cells was been evaluated by digital pathology analyses using cellSens Dimension and Image-Pro Premier Offline (MediaCybernetics, Version 9.1.4 Build 5638) software.

Monoclonal CD61 antibody stained mature megakaryocytes, with a medium size of 50 µm in bone marrow and 20 µm in lung interstitial tissue, together with pre-megakaryocytes and pro-megakaryocytes with a mean size of 10 µm, and mature platelets with a medium size of 2,65 µm. Different nuclear sizes for pro-megakaryocytes, pre-megakaryocytes and mature megakaryocytes has been evaluated and reported as large sized multi-lobated and polyploid nuclei of medullary megakaryocytes and small sized and diploid nuclei of interstitial lung megakaryocytes. Positive control slide has been used for each immunohistochemical experiment using bone marrow samples. A series of non-inflamed lungs and of chronic interstitial lung pneumonia have been used to match samples of Sars-Cov-2 infected iper-inflamed lethal cases of Covid-19 pneumonia.

All the controls have pathological morbidity leading to surgical intervention for therapeutic purpose. In details, two out eleven cases had metastasis to the lung from distant carcinomas (one from breast cancer and one from large bowel cancer), six out 11 cases had primary lung adenocarcinomas, one out 11 had lung hamartoma, and two out 11 had complicated lung emphysema. This COVID-19(-) cohort, carrying slight chronic lung pneumonia, have been used to match samples of SARS-CoV-2(+) infected hyper-inflamed lethal cases of pneumonia, leading to not resolved COVID-19 related ARDS and death, representing the COVID-19(+) cohort.

In situ hybridization (ISH) method for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Briefly, ISH detection of SARS-CoV-2 was been performed using V-nCoV2019-S probe to detect viral sequences Spike (S) of SARS-CoV-2 in lung tissue using RNAscope 2.5 high-definition detection kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics). SARS-CoV-2 was been detected in lung tissues of lethal COVID-19 disease by in ISH according to methods reported in previous work of our laboratories in which we compared ISH with PCR methods [

23,

24,

25] and in current literature [

32].

Statistical analyses. Data have been analyzed by SOFA Statistics 1.4.6, and SPSS 28.01.0 Data Analysis and Statistical Software and Windows Operating Systems; Spearman's test and ANOVA statistical analysis were been used to correlate to clinicopathological parameters. Mann-U-Whitney testwas been used to compare non-parametrical variables (

Table 3).

3. Results

3.1. Main Histopathological Findings

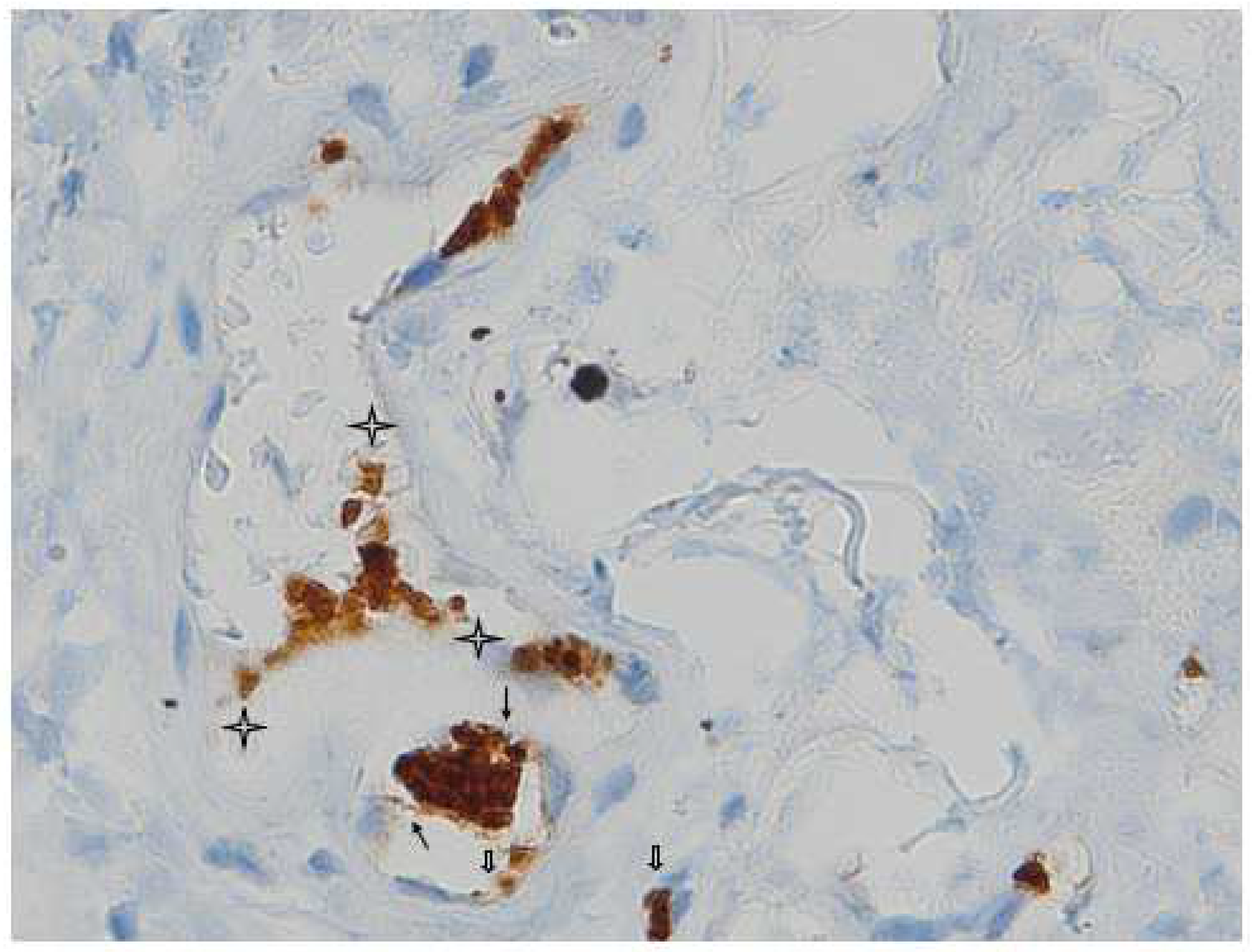

Megakaryocyte lies on the basement membrane of the capillary vessel and its offshoot proplatelets are in contact with two adjacent endothelial cells (

Figure 1).

CD61 + interstizial megakaryocytes line the alveolar space of denuded pneumocytes in Sars Cov-2 damaged lung.

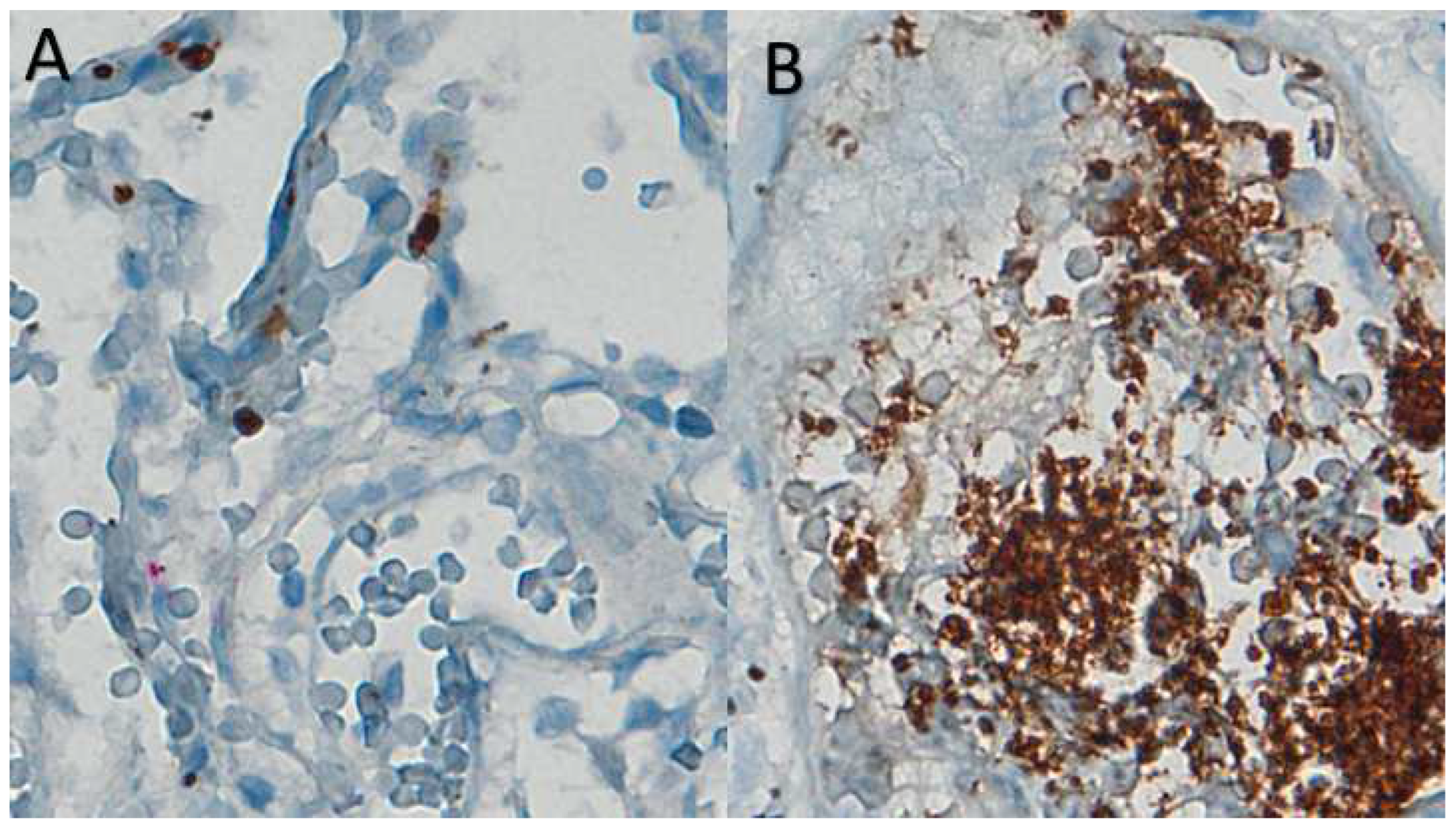

In uninfected lung interstizial vessel there are very rare platelet, stained with CD61 marker.(

Figure 2 A).

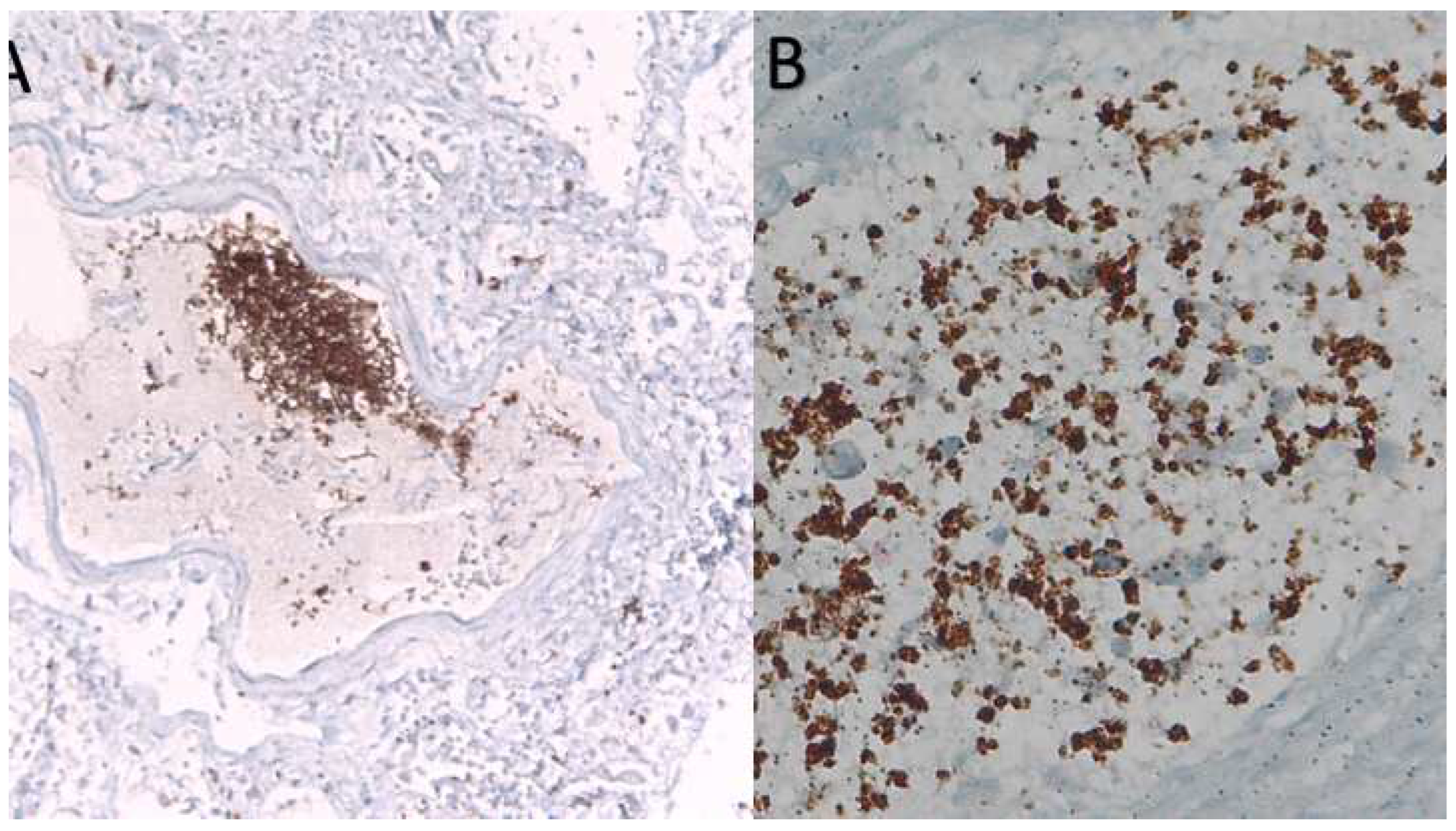

The interaction in vessels of SARS-Cov-2 patients of monocyted (CD61-) and platelets (CD61+) is responsible for hypercoagulation, thrombosis and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) a late event associated to lethality (

Figure 2B and Figure 3A and B).

3.2. In Situ Hybridization (ISH).

All patients who died from a lethal form of SARS-CoV-2 infection in our cohort of COVID-19 lethal disease had ARDS due to lung tissue viral persistence demonstrated by PCR as previously reported[

23].Therefore in this study we presented the percentage of Spike-1

(+) cases as evaluated by ISH compared to mean values ± Standard Error Means (SEM) of selected studied markers (TLR-2, CD61) (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Mean ± SEM of TLR2, CD61 immunoreactivity values according to COVID-19 status, and Spike-1 ISH detection.

Table 3.

Summary of Mean ± SEM of TLR2, CD61 immunoreactivity values according to COVID-19 status, and Spike-1 ISH detection.

| COVID-19 Status |

Immunohistochemistry |

Spike-1 (ISH)

Positive/Total, (%) |

| |

CD61

Mean ± SEM |

TLR2

Mean ± SEM |

|

| Positive |

|

108.43 ± 35.22 |

163.33 ± 38.50 |

|

Spike-1 positive

12/25(48) |

| 35.23 ± 17.46 |

95.54 ± 19.66 |

|

Spike-1 negative

13/25(52) |

| Negative |

|

26.50 ± 7.41 |

16.33 ± 5.29 |

|

|

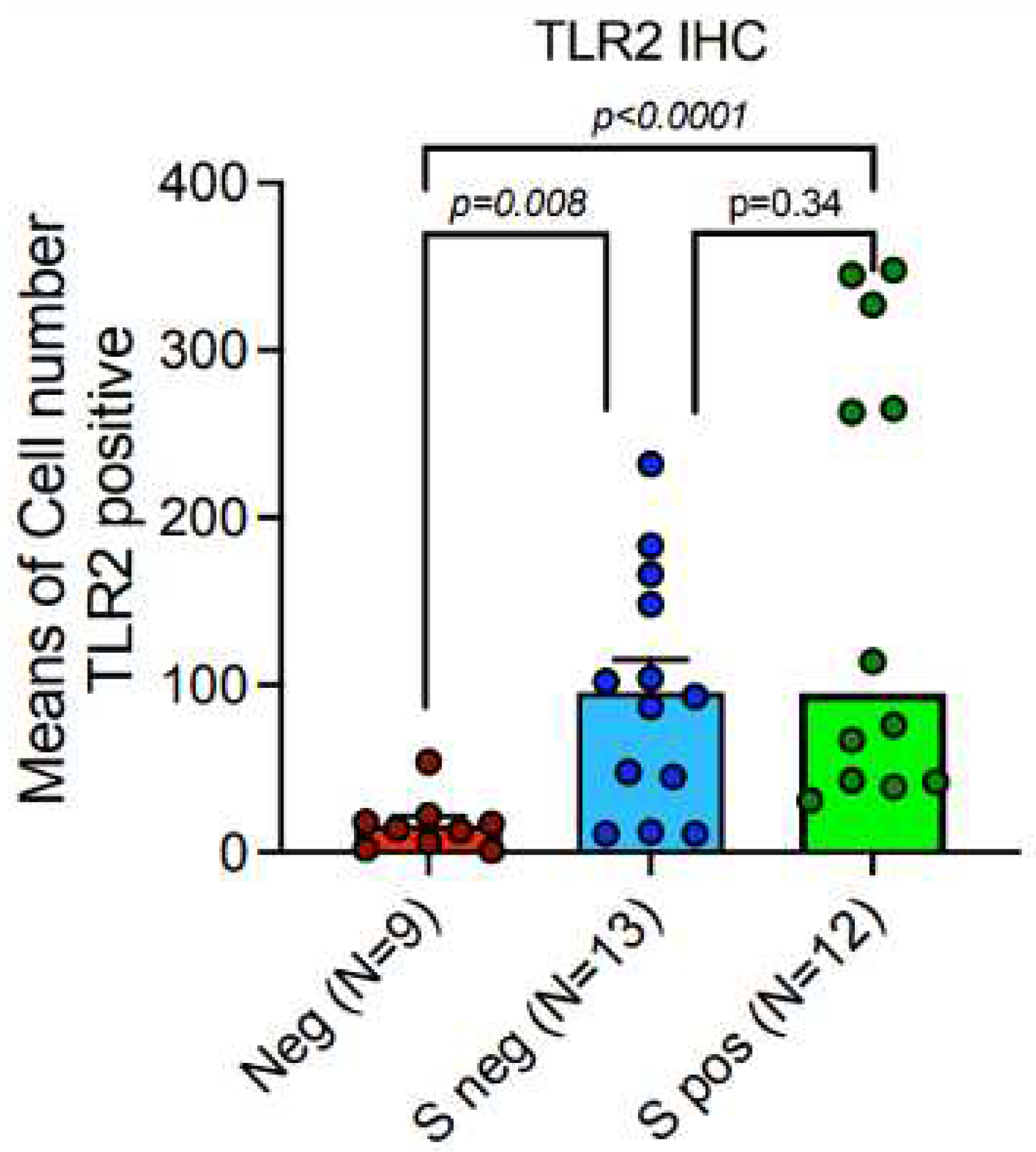

3.3. TLR-2 Expression Was Up-Regulated in a Subgroup of Patients with Lethal COVID-19 Lung Disease.

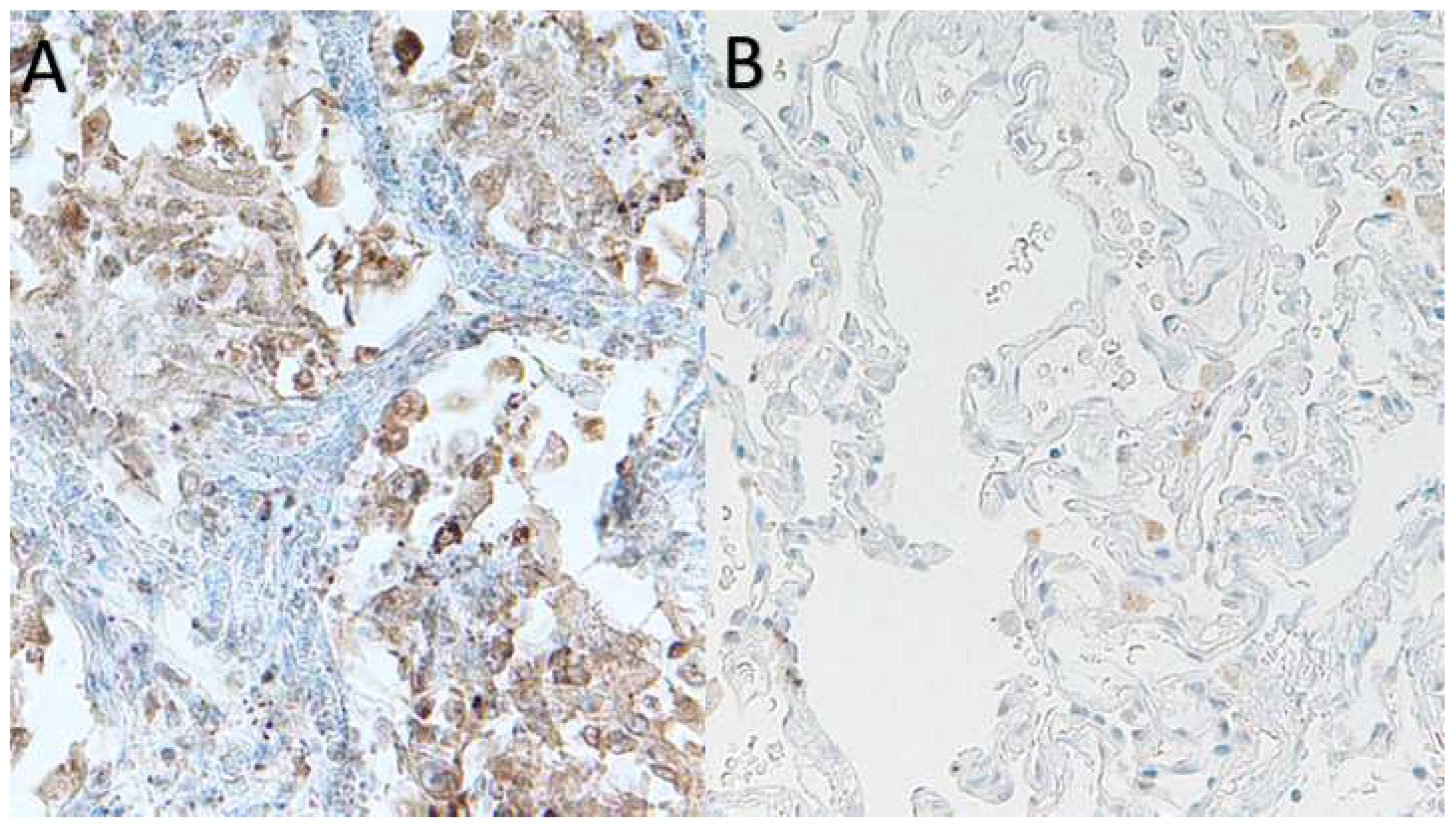

TLR-2 was significantly higher in lungs of patients with lethal Covid-19 (

Figure 4)Furthermore, TLR-2 was up-regulated in lung macrophages in a subgroup of deceased COVID-19 patients..The average of TLR-2stained macrophage per square area is up-regulated as compared to control cases, however, statistically significant values are not reached, in this cohort, due to heterogeneous variability of TLR-2 mediated hyper-inflammation in different deceased subjects. In detail, our digital pathology based immunohistochemistry showed a mean count of TLR-2 positive macrophages of 128,08 ± SEM 21,789 in COVID-19 patients, versus mean count of 16,33 ± SEM 5,29 in control cases. Nevertheless, our study showed a trend to TLR-2 up-regulation in lungs of a subgroup patients with lethal COVID-19, when compared to the control group of SARS-CoV-2 negative lungs. In particular, we showed a sub-group with strong TLR-2 over-expression (

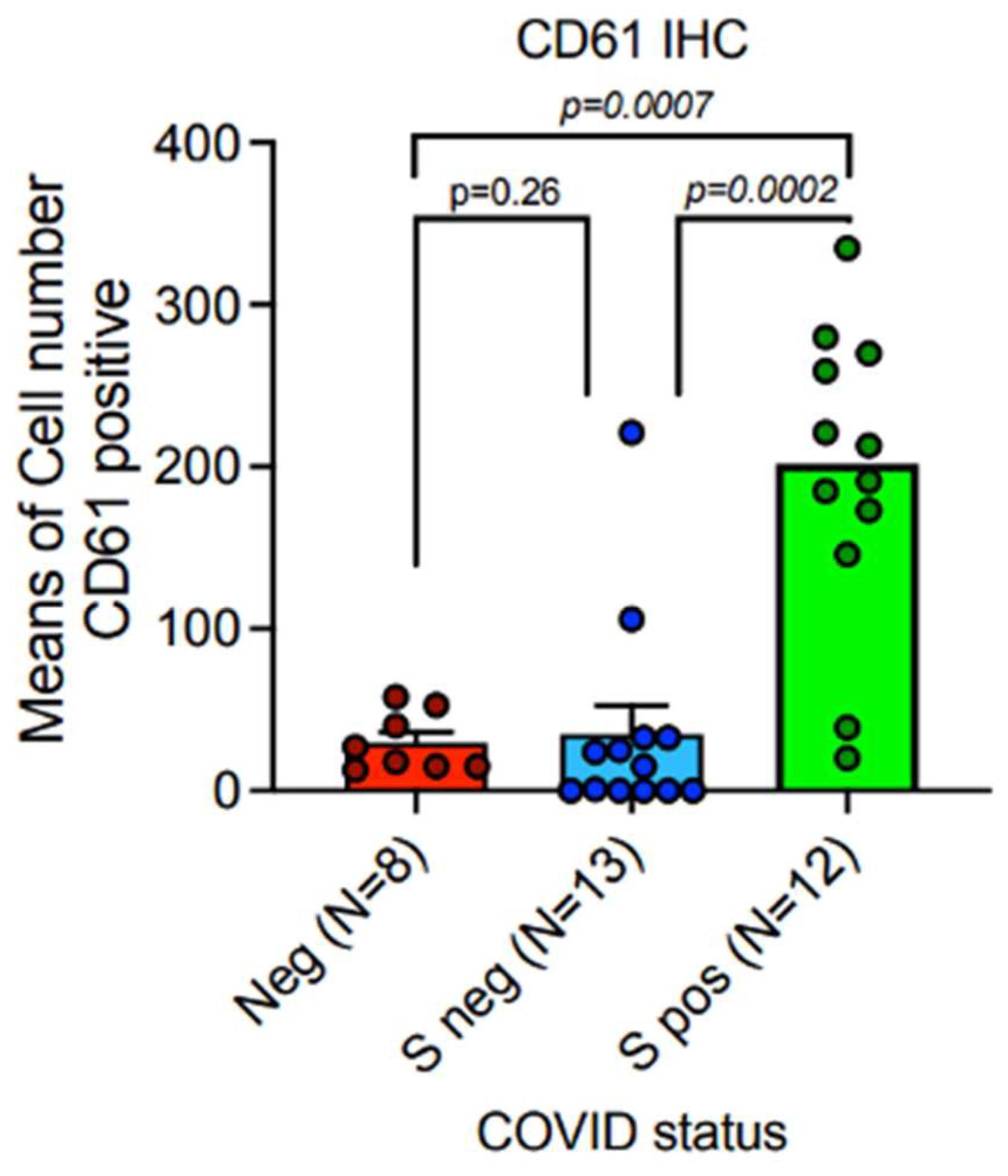

Figure 5). 3.4. Platelet Membrane Glycoprotein IIIa (CD61) Was Up-Regulated in a Subgroup of Patients with Lethal COVID-19 Lung Disease.

Expressione of CD61 showed significant up-regulation in lungs of patients with lethal Covid 19, when compared to the control group od SARS-Cov-2 negative lungs. The subgroup of patients with significantly high levels of CD61+ platelets and magakaryocytes, associated with a systemic pro-thrombotic state and with the formation of tissue micro-thrombosis, corresponds to the Spike-S1 positive cases demonstrated by PCR and ISH methods.

Means and SEM were obtained by immunohistochemical expression of CD61 (clone 9C4) (

Table 3,Figure 6), as evaluated by digital pathology analysis; Spike-1

(+)status was detected by PCR-based methods and ISH.Immunohistochemistry showed a mean count in SARS-CoV-2

(-) controls of 26,50 ± 7,41 SEM, versus mean count of 35,23 ± 17,46 SEM, and 180,43 ± 35,33 SEM in Spike-1

(-) and Spike-1

(+) COVID-19 deceased patients respectively. Comparisons were statistically significant as evaluated by Mann-U-Whitney test(p<0,001).

4. Discussion

Lethal Covid-19 lung disease is a pathological process with lack of defense mechanism induced by the virus and a massive innate immunity with iper-inflammation e necroptosis, in some of the cases there is a significant number of inflammatory cells, such as in exudative pneumonia, while in other cases, there is a moderate number of inflammatory interstitial cells, joint participation of pneumocytes, endothelium and maturating megakaryocytes [

26].There are also myeloid derived cells such as megakaryocytes, platelets and macrophages M1 (CD68+, CD61+) and a modest percentage of lymphocytes. In the analyzed cases is shown an unstopped inflammatory process, an ineffective macrophage M2 response and a production of cytokines by megakaryocytes/platelets/macrophages/endothelium. In the majority of studied cases, there is an early-intermediate diffuse alveolar damage DAD phase histologically proven, except for a reduced number than expected showing advanced late DAD associated with advanced fibrosis[

27].

Formation of fibrin-rich thrombi is a key aspect of DAD. In vivo imaging studies suggest that Interleukine-1 (IL-1) and Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNF-α) may mobilize von Willebrand Factor (vWF) to the endothelial surface in inflammation, inducing thrombus formation mediated by platelet glycoprotein GPlbα-lX-V complex [

28]. In vivo imaging visualizes discoid platelet aggregations without endothelium disruption and implicates contribution of inflammatory cytokine and integrin signaling [

29].

To date there is sufficient evidence that lung megakaryocytes are directly infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus. In the bone marrow, viral SARS-CoV-2 NProtein has been detected within megakaryocytes, key cells in platelet production and thrombus formation [

30]SARS-CoV-2 interacts with platelets and megakaryocytes via angiotensin-converting ezyme 2 (ACE2)-independent mechanism [

31]. However, other authors report that SARS-CoV-2 interacts with platelets and megakaryocytes via ACE2-dependent mechanisms [

32].

Furthermore, platelets and megakaryocytes are activated directly by inflammatory response indirectly through the cytokine storm [

33] and indirectly by the effects on the bone marrow. In particular by the biological effects exerted by IL-6. IL-6 upregulates the process of megakaryocytopoiesis in bone marrow by stimulating TPO, thereby increasing the number of blood platelets in circulation [

34].

Although in the past it was thought that megakaryocytes fully mature in the bone marrow and arrive in the lung to release platelets, today it has been discovered that pulmonary megakaryocytes have a much more complex and articulated role, as they are responsible for the production of large quantities of platelets which in some studies they come to be demonstrated as 50% of the entire production of platelets and also in conditions of stress of the hematopoietic marrow they are able to exit the lungs and colonize the hematopoietic marrow again, restore the number of platelets and contribute to hematopoiesis multilinear[

35].

Recently, it’s demonstrate the presence of megakaryocytes not only in the bone marrow, but also in the microcirculation and extravascular space of the lung, providing the 50% of the total platelets production [

35].

Infection and lung injuries are associated with the megakaryopoiesis stimulus and increase of lung megakaryocytes.In the lungs of patients who died from COVID-19, megakaryocytes were found in the interstitial alveolar capillaries with the presence of aspects of nuclear hyperchromasia and atypia identified with specific immunohistochemical methods by means of staining positivity for CD61, in association with platelets; platelets within small vessels together with fibrin networks aggregate inflammatory cells including neutrophils and monocyte-macrophages[

36].

Lung megakaryocytes in infectious pneumonia generally have an early precursor gene profile compared to mature bone marrow megakaryocytes[

37]. Cytokines such as IL-3, IL-6, IL-11, LIF, erythropoietin, and thrombopoietin stimulate megakaryocyte progenitor cell maturation[

38], while the chemochineas CXCL5, CXCL7,CCL5inhibit megakaryocyte progenitor cell maturation [

39]. In particular, IL-6, together with SCF, IL-3 and IL-11, is involved in the activation of endomitosis in megakaryocytes[

40] and acts in a TPO-dependent manner together with IL [interleukin]-1β, IL-3, YRSACT , while IL-1α, CCL5 [C-C motif chemokine ligand 5], IGF [insulin-like growth factor]-1) act in a TPO-dependent manner Independent.

Thus, we hypothesize that IL-6 upregulation in COVID-19, as well as IL-3, IL-11 upregulation, is likely involved in the stimulation of megakaryocytes and possibly also resident megakaryocytes in the lung. Platelets and monocytes-macrophages have both been found in the lungs of subjects who died from COVID-19 and it is therefore important to learn more about the interactions between platelets and monocytes-macrophages. Interleukin-6 is an important regulator of thrombopoiesis as megakaryocytes produce IL-6 and express IL-6R on their surface[

41]. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that interleukin 6 is a potent promoter of megakaryocyte maturation[

42]IL-6 is able to increase platelet count thus demonstrating a thrombocytopoietic role; however some functions can be exacerbated in inflammatory pathological conditions as a dysregulation of IL-6 can alter platelet function, making the platelets themselves more sensitive to the action of thrombin and other agonist factors on platelets. IL-6 also increases plasma fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor. These IL-6-mediated modifications of both platelets and the coagulation phase may be decisive in the mechanism of thrombogenesis in the course of pathological inflammation.

Thrombocytopenia has been clearly associated with mortality in patients with COVID-19 [

4].

There are numerous pathogenetic mechanisms to explain thrombocytopenia in infections, which have been reviewed by Yang M et al [

4].

In our study expression of CD61 showed significant up-regulation in lungs of patients with lethal COVID-19, when compared to the control group of SARS-CoV-2 negative lungs. The subgroup of patients with significantly high levels of CD61+ platelets and megakaryocytes, associated with a systemic pro-thrombotic state and with the formation of tissue micro-thrombosis, corresponds to the Spike-S1 positive cases demonstrated by PCR and ISH methods.

Platelets have many TLRs on their cell membrane, including TLR4. Binding of microorganism (virus, bacteria, fungi) to TLR4 induces platelets activation and release of their granule content (many factors involved in different processes) [

18]

In our previous study, we demonstrated upregulation of TLR4 in lethal SARS-Cov 2 disease [

19].

In this study we demonstrated that the expression of TLR2 similarly was significantly higher in lungs of patients with lethal COVID-19, when compared to the control group of SARS-CoV-2 negative lungs.

5. Conclusions

Microthrombosis in deadly covid-19 lung disease is associated with an increase in the number of platelets and megakaryocytes in the pulmonary interstitium as well as their functional activation; it is also associated with an increase in innate immunity TLR2, which binds the Sars-Cov2 E protein, and the persistence of the spike 1 sequence.

References

- Menter, D.G.; Kopetz , S.; Hawk, E.; Sood, A.K; Loree, J.M.; Gresle, P.; Honn, V.K.. Platelet "first responders" in wound response, cancer, and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017.36(2):199–213. [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Huang, M.; Li, D;Tang N. Difference of coagulation features between severe pneumonia induced by SARS-CoV2 and non-SARS-CoV2. J Thromb Thrombolysis.2020.51 (4): 1107-1110. [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Plebani, M.; Henry, B.M. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis [published online ahead of print. Clin Chim Acta. 2020. Mar 13. 506:145–148. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, Q.;, Wang, Y.; WU, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, Y:; Shang, Y. Thrombocytopenia and its Association with Mortality in Patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. 10.1111/jth.14848. [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, E.I.; Macal, M.; Lewis, G.M.; Harker, J.A. Innate and Adaptive Immune Regulation during Chronic Viral Infections. Annu.Rev. Virol. 2015, 2, 573–597. [CrossRef] [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern Recognition Receptors and Inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820. [CrossRef] [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, L.; Massberg, S. Platelets as key players in inflammation and infection. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2020, 27, 34–40. [CrossRef][PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Dib, P.R.B.; Quirino-Teixeira, A.C.; Merij, L.B.; Pinheiro, M.B.M.; Rozini, S.V.; Andrade, F.B.; Hottz, E.D. Innate immune receptorsin platelets and platelet-leukocyte interactions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 108, 1157–1182. [CrossRef] [PubMed].

- Beaulieu, L.M.; Freedman, J.E. The role of inflammation in regulating platelet production and function: Toll-like receptors in platelets and megakaryocytes. Thromb Res.2010. 125(3):205-209. [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, F.; Ammollo, C.T.; Morrissey, J.H.; Dale, G.L.; Friese, P.; Esmon, N.L.; Esmon, C.T. Extracellular histones promotethrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: Involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4.Blood 2011, 118, 1952–1961.[CrossRef]].

- Wadowski, P.P.; Panzer, B.; Józkowicz, A.; Kopp, C.W.; Gremmel, T.; Panzer, S.; Koppensteiner, R. Microvascular Thrombosis as a Critical Factor in Severe COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. Jan 27;24(3):2492. PMID: 36768817; PMCID: PMC9916726. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Shafiei, M..S.; Longoria, C.; Schoggins, J.W.; Savani, R.C.; Zaki, H. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces inflammation via TLR2-dependent activation of the NF-κB pathway. Elife.2021. 10:e68563. [CrossRef]

- Biswas S.; Zimman, A.; Gao, D.; Byzova, T.V.; Podrez, E.A. TLR2 Plays a Key Role in Platelet Hyperreactivity and Accelerated Thrombosis Associated with Hyperlipidemia. Circ. Res.2017. 121:951–962. [CrossRef]

- Into T.; Kanno, Y.; Dohkan, J.I.; Nakashima, M.; Inomata, M.; Shibata, K.I.; Lowenstein C.J.; Matsushita K. Pathogen Recognition by Toll-like Receptor 2 Activates Weibel-Palade Body Exocytosis in Human Aortic Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem.2007. 282:8134–8141. [CrossRef]

- Singh B.; Biswas I..; Bhagat, S.; Surya Kumari S.; Khan G.A. HMGB1 facilitates hypoxia-induced vWF upregulation through TLR2-MYD88-SP1 pathway. Eur. J. Immunol.2016. 46:2388–2400. [CrossRef]

- Carestia A.; Kaufman, T.; Rivadeneyra, L.; Landoni, V.I.; Pozner, R.G.; Negrotto S.; D’Atri L.P.; Gómez R.M.; Schattner M. Mediators and molecular pathways involved in the regulation of neutrophil extracellular trap formation mediated by activated platelets. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016. 99:153–162. [CrossRef]

- Fujimura Y.; Holland, L.Z. COVID-19 microthrombosis: Unusually large VWF multimers are a platform for activation of the alternative complement pathway under cytokine storm. Int. J. Hematol.2022. 115:457–469. [CrossRef]

- Mussbacher, M.; Salzmann, M.; Brostjan, C.; Hoesel, B.; Schoergenhofer, C.; Datler, H.; Hohensinner, P.; Basílio, J.; Petzelbauer, P.; Assinger, A.; Schmid, J.A. Cell Type-Specific Roles of NF-κB Linking Inflammation and Thrombosis. Front Immunol.2019 Feb 4. 10:85. PMID: 30778349; PMCID: PMC636921. [CrossRef]

- Pedicillo, M.C.; De Stefano, I.S.; Zamparese R.; Barile R.;, Meccariello, M.;, Agostinone, A.; Villani, G.; Colangelo, T.; Serviddio, G.; Cassano T.; Ronchi, A.; Pannone, P.; Zito Marino, F.; Miele F.; , Municinò, M.; Pannone. G. The Role of Toll-Like receptor-4 in Macrophage Imbalance in Lethal COVID19 Lung Disease, and Its Correlation with Galectina-3. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2023, 24, 13259. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, F.; Pezzuto, F.; Fortarezza, F.; Hofman, P.; Ker, I.; Panizo, A.; Thusen, V.V.d.; Timofeev, S.; Gorkiewicz, G.; Lunardi, F. Pulmonary pathology and COVID-19: Lessons from autopsy: The experience of European Pulmonary Pathologists. VirchowsArch. 2020, 477, 359–372. [CrossRef] [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Basso, C.; Calabrese, F.; Sbaraglia, M.; Del Vecchio, C.; Carretta, G.; Saieva, A.; Donato, D.; Flor, L.; Crisanti, A.; Tos, A.P.D. Feasibility of postmortem examination in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: The experience of a Northeast Italy University Hospital.Virchows Arch. 2020, 477, 341–347. [CrossRef] [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, A.; Marino, F.Z.; Carraturo, E.; La Mantia, E.; Campobasso, C.P.; De Micco, F.; Mascolo, P.; Municinò, M.; Mucininò, E.; Vestini, F.; et al. PD-L1 Overexpression in the Lungs of Subjects Who Died from COVID-19: Are We on the Way to Understandingthe Immune System Exhaustion Induced by SARS-CoV-2? Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2022, 32, 9–20. [CrossRef].

- Hooper, J.E.; Padera, R.F.; Dolhnikoff, M.; da Silva, L.; Duarte-Neto, A.N.; Kapp, M.E.; Lacy, J.M.; Mauad, T.; Saldiva, P.; Rapkiewicz, A.V.; et al. A Postmortem Portrait of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Large Multi-institutionalAutopsy Survey Study. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2021, 145, 529–535. [CrossRef] [PubMed].

- Massoth, L.R.; Desai, N.; Szabolcs, A.; Harris, C.K.; Neyaz, A.; Crotty, R.; Chebib, I.; Rivera, M.N.; Sholl, L.M.; Stone, J.R.; et al. Comparison of RNA In Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry Techniques for the Detection and Localization ofSARS-CoV-2 in Human Tissues. Am. J. Surg. Pathol.2021, 45, 14–24. [CrossRef].

- Roden, A.C.; Vrana, J.A.; Koepplin, J.W.; Hudson, A.E.; Norgan, A.P.; Jenkinson, G.; Yamaoka, S.; Ebihara, H.; Monroe, R.; Szabolcs, M.J.; et al. Comparison of In Situ Hybridization, Immunohistochemistry, and Reverse Transcription-Droplet Digital Polymerase Chain Reaction for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Testing in Tissue. Arch. Pathol.Lab. Med.2021, 145, 785–796. [CrossRef].

- Viksne, V.; Strumfa, I.; Sperga, M.; Ziemelis, J.; Abolins, J. Pathological Changes in the Lungs of Patients with a Lethal COVID-19 Clinical Course. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022 Nov. 12(11), 2808. PMCID: PMC9689224 PMID: 36428868. [CrossRef]

- Maiese, A.; Manetti, A.C.; LaRussa, R.; Di Paolo, M.; Turillazi, E.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Autopsy findings in Covid-19 related deaths: a literature review. Forensic Sci Med Pathol.2021, 17(2): 279-296. PMCID: PMC7538370. PMID: 33026628. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.; Manabe, I.; Nagasaki, M.; Kakuta, S.; Iwakura, Y.;, Takayama, N.; Ooehara, J.; Otsu, M.; Kamiya, A.; Petrich, B.G.; Urano, T.; Kadono, T.; Sato, S.; Aiba, A.; Yamashita, H.; Sugiura, S.; Kadowaki, T.; Nakauchi, H.; Eto, K.; Nagai, R. In vivo imaging in mice reveals local cell dynamics and inflammation in obese adipose tissue. 2008.J Clin Invest, 118(2): 710-721. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.; Manabe, I.; Nagasaki, M.; Kakuta, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Takayama, N.; Ooehara, J.; Otsu, M.; Kamiya, A.; Petrich, B.G.; Urano, T.; Kadono, T.; sato, S.; Aiba, A.; Yamashita, H.; Sugiura S.; Kadowaki, T.; Nakauchi, H.; Eto, K.; Nagai, R. In vivo imaging visualizes discoid platelet aggregations without endothelium disruption and implicates contribution of inflammatory cytokine and integrin signaling. Blood. 2012. 119 (8): e45-e56 Blood (2012) 119 (8): e45–e56. [CrossRef]

- Gray-Rodriguez, S.; Jensen, M.P.; Otero-Jimenez, M.; Hanley, B.; Swann, O.C.; Ward, P.A.; Saguero, F.J.; Querido, N.; Farkas, I.; Velentza-Almpani, E.; Weir, J.; Barclay, W.S.; Carroll, M.W.; Jaunmuktane, Z.; Brandner, S.; Pohl, U.; Allinson, K.; Thom, M.; Troakes, C.; Al-Sarraj. S.; Sastre, M.; Gveric, D.; Gentleman, S.; Roufosse, C.; Osborn, M,; Alegre-Abarrategui, J. Multisystem screening reveals SARS-CoV-2 in neurons of the myenteric plexus and in megakaryocytes. J Pathol.2022 Feb 2. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35107828. [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Y.; Lu, S.; Zheng, X.; Deng, F. SARS-CoV-2 interacts with platelets and megakaryocytes via ACE2-independent mechanism. J Hematol Oncol2021. 14, 72. [CrossRef]

- Zaid, Y.; Guessous, F. The ongoing enigma of SARS-CoV-2 and platelet interaction. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022. Jan 25;6(1):e12642. PMID: 35106430; PMCID: PMC8787413. [CrossRef]

- Battina, H.L.; Alentado, V.J.; Srour, E.F.; Moliterno, A.R.; Kacena, M.A. Interaction of the inflammatory response and megakaryocytes in COVID-19 infection. Exp Hematol.2021. 104:32-39. [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.; Bertoncello, I.; Jackson, H.; Arnold, J.; Kavnoudias, H. The role of interleukin 6 in megakaryocyte formation, megakaryocyte development and platelet production. Ciba Found Symp.1992. 167:160–170. discussion 170–163.

- Lefrançais, E.; Ortiz-Muñoz, G.; Caudrillier, A.; Mallavia, B.; Liu, F.; Sayah, D.M.;Thornton, E.E.; Headley, M.B.; David, T.;Coughlin, S.R.; Krummel, M.F.; D Leavitt, A.; Passeguè, E.; Looney M.R.; The lung is a site of platelet biogenesis and a reservoir for haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2017; 544(7648):105–109. [CrossRef]

- Weyrich, A.S.; Zimmerman, G.A. Platelets in lung biology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013. 75: 569–591. [CrossRef]

- Lefrançais, E.; Ortiz-Muñoz, G.; Caudrillier, A.; Mallavia, B.; Liu, F.; Sayah, D.M.;Thornton, E.E.; Headley, M.B.; David, T.;Coughlin, S.R.; Krummel, M.F.; D Leavitt, A.; Passeguè, E.; Looney M.R.; The lung is a site of platelet biogenesis and a reservoir for haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2017; 544(7648):105–109. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.S.; Hoffman, R. Growth factors affecting human thrombocytopoiesis: potential agents for the treatment of thrombocytopenia, in Blood. vol. 80, 1992, pp. 302-307.

- Pang, L.; Weiss, M.J.; Poncz, M. Megakaryocyte biology and related disorders. J. Clin. Invest., 2005 (115) , pp. 3332-3338. [CrossRef]

- 40. Alan T Nurden. The biology of the platelet with special reference to inflammation, wound healing and immunity. Frontiers In Bioscience, Landmark, 2018, 23, 726-751. [CrossRef]

- Noetzli, L.J.; French, S.L.; Machlus, K.R. New Insights Into the Differentiation of Megakaryocytes From Hematopoietic Progenitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019; 39(7):1288–1300. [CrossRef]

- Burstein SA. Effects of interleukin 6 on megakaryocytes and on canine platelet function. StemCells. 1994;12(4):386–393. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Megakaryocyte lies on the basement membrane of the capillary vessel and its offshoot proplatelets are in contact with two adjacent endothelial cells. The staining shows the connections between megakaryocytes and endothelium (full arrows) and between endothelium and platelets (empty arrows); note the proplatelets (full arrowheads) and released platelets (stars); in the lower caliber microvessels (< 10 micron) red blood cells must stack in a narrow lumen which in cross section is lined by two endothelial cells and one megacaryocyte [bottom of the figure](CD-61 immunostaining with standard LSAB-HRP, nuclear counterstainig with Gill’s type-II Haematoxylin; further magnification of a x60 histological picture).

Figure 1.

Megakaryocyte lies on the basement membrane of the capillary vessel and its offshoot proplatelets are in contact with two adjacent endothelial cells. The staining shows the connections between megakaryocytes and endothelium (full arrows) and between endothelium and platelets (empty arrows); note the proplatelets (full arrowheads) and released platelets (stars); in the lower caliber microvessels (< 10 micron) red blood cells must stack in a narrow lumen which in cross section is lined by two endothelial cells and one megacaryocyte [bottom of the figure](CD-61 immunostaining with standard LSAB-HRP, nuclear counterstainig with Gill’s type-II Haematoxylin; further magnification of a x60 histological picture).

Figure 2.

A) CD61 in uninfected lung interstitial vessel; B) interstizial vessels knots stained with megacaryocytes/plateler CD61 marker in Covid-19 desease. (CD-61 immunostaining with standard LSAB-HRP, nuclear counterstainig with Gill’s type-II Haematoxylin; further magnification of a x60 histological picture).

Figure 2.

A) CD61 in uninfected lung interstitial vessel; B) interstizial vessels knots stained with megacaryocytes/plateler CD61 marker in Covid-19 desease. (CD-61 immunostaining with standard LSAB-HRP, nuclear counterstainig with Gill’s type-II Haematoxylin; further magnification of a x60 histological picture).

Figure 3.

A) CD61+ platelets in lung micro-thrombus; B) Monocytes (CD61-) and platelets (CD61+) interaction in vessels of SARS-COV-2+ PATIENT .This is responsible for hypercoagulation, thrombosis and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) a late event associated to lethality(CD-61 immunostaining with standard LSAB-HRP, nuclear counterstainig with Gill’s type-II Haematoxylin; further magnification of a x 20 histological picture).

Figure 3.

A) CD61+ platelets in lung micro-thrombus; B) Monocytes (CD61-) and platelets (CD61+) interaction in vessels of SARS-COV-2+ PATIENT .This is responsible for hypercoagulation, thrombosis and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) a late event associated to lethality(CD-61 immunostaining with standard LSAB-HRP, nuclear counterstainig with Gill’s type-II Haematoxylin; further magnification of a x 20 histological picture).

Figure 4.

TLR-2 up-regulation in COVID-19 lethal COVID-19 lung disease (A ), as compared to uninfected lung (B) (CD-61 immunostaining with standard LSAB-HRP, nuclear counterstainig with Gill’s type-II Haematoxylin; further magnification of a x 20 histological picture).

Figure 4.

TLR-2 up-regulation in COVID-19 lethal COVID-19 lung disease (A ), as compared to uninfected lung (B) (CD-61 immunostaining with standard LSAB-HRP, nuclear counterstainig with Gill’s type-II Haematoxylin; further magnification of a x 20 histological picture).

Figure 5.

TLR2 (CD282) was strongly up-regulated in both Spike-positive and Spike-negative SARS-CoV-2 related autoptic lethal lungs, when compared to SARS-CoV-2 negative controls; Mann-U-Withney statistical test (p<0,001), with further increase of the levels of expression in Spike-positive cases (p<0,0001).

Figure 5.

TLR2 (CD282) was strongly up-regulated in both Spike-positive and Spike-negative SARS-CoV-2 related autoptic lethal lungs, when compared to SARS-CoV-2 negative controls; Mann-U-Withney statistical test (p<0,001), with further increase of the levels of expression in Spike-positive cases (p<0,0001).

Figure 6.

Platelet-megakaryocyte up-regulation is strongly associated with the persistence of Spike-1 in lethal COVID-19 lung disease.Expression of CD61 showed significant up-regulation in lungs of patients with lethal COVID-19, when compared to the control group of SARS-CoV-2 negative lungs. The subgroup of patients with significantly high levels of CD61+ platelets and megakaryocytes, associated with a systemic pro-thrombotic state and with the formation of tissue micro-thrombosis, corresponds to the Spike-S1 positive cases demonstrated by PCR and ISH methods. Means and standard deviations were obtained by immunohistochemical (IHC) expression of CD61 (glycoprotein IIIa), as evaluated by digital pathology analysis; Spike positive status was detected by PCR-based methods and In Situ Hybridization; Mann-U-Withney statistical test (p<0,001).

Figure 6.

Platelet-megakaryocyte up-regulation is strongly associated with the persistence of Spike-1 in lethal COVID-19 lung disease.Expression of CD61 showed significant up-regulation in lungs of patients with lethal COVID-19, when compared to the control group of SARS-CoV-2 negative lungs. The subgroup of patients with significantly high levels of CD61+ platelets and megakaryocytes, associated with a systemic pro-thrombotic state and with the formation of tissue micro-thrombosis, corresponds to the Spike-S1 positive cases demonstrated by PCR and ISH methods. Means and standard deviations were obtained by immunohistochemical (IHC) expression of CD61 (glycoprotein IIIa), as evaluated by digital pathology analysis; Spike positive status was detected by PCR-based methods and In Situ Hybridization; Mann-U-Withney statistical test (p<0,001).

Table 1.

Patients and controlsA series of 25 patients with someone comorbidities (Chronic nephropathy, Hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, Obesity, diabetes mellitus, Obstructive chronic broncho-pneumopathy) who died from a lethal form of Sars-CoV2 infection were studied. 13 males and 12 females, age between 45 and 80 years.

Table 1.

Patients and controlsA series of 25 patients with someone comorbidities (Chronic nephropathy, Hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, Obesity, diabetes mellitus, Obstructive chronic broncho-pneumopathy) who died from a lethal form of Sars-CoV2 infection were studied. 13 males and 12 females, age between 45 and 80 years.

| |

Age < 50 |

Age >50 |

| Female COVID-19 cases |

1 |

11 |

| Female Control cases |

0 |

2 |

| Male Covid-19 cases |

2 |

11 |

| Male Control cases |

1 |

10 |

Table 2.

Antibody used and experimental conditions.

Table 2.

Antibody used and experimental conditions.

| ANTIBODY |

CLONE |

METHOD |

| TLR2 |

rabbit policlonal |

LSAB-HRP/AP, Ventana Benchmark® XT autostainer |

| CD61 |

2f2 |

LSAB-HRP/AP, Ventana Benchmark® XT autostainer |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).