1. Introduction

Congenital myopathies are a group of genetic muscle diseases that are classified based on the histopathological features observed on muscle biopsy [

1]. Among these disorders nemaline myopathy (NM) was first described as a non-progressive congenital musculoskeletal disorder, characterized by the presence of inclusions in muscle fibers called "nemaline rods" [

2]. This pathology contains a wide genetic heterogeneity, since multiple mutations in different genes that produce a similar phenotype have been identified [

3]. Its incidence is approximately 1 in 50,000 live births.

The International European Neuromuscular Group classifies NM into six clinical subtypes based on the severity, age of onset, and degree of muscle weakness: severe congenital (neonatal), Amish, intermediate congenital, typical congenital, childhood onset, and adult-onset [

4]; Of these, the most common subtype corresponds to the typical congenital subtype [

5]. The most common clinical presentation is characterized by an onset in early infancy or childhood with hypotonia or generalized weakness predominantly in facial, axial, and proximal limb muscles. Additional features include skeletal deformities, dysmorphic fascia, arched high palate, and respiratory distress with respiratory tract infections [

1]. The natural history of the disease is usually static or very slowly progressive and many of the patients can lead normal lives. Serious clinical complications are almost always secondary to respiratory deficiency and sometimes to cardiological problems. In most cases, cardiomyopathy develops in adulthood, while rarely occurs in childhood [

6].

There are 14 known causative genes of NM [

7]. Mutations in the

ACTA1 and

NEB genes, which code for actin 1 alpha (ACTA1) and nebulin (NEB) proteins, respectively, critical components of the sarcomeric thin filament, result in the most prevalent types of NM. More specifically, it is predicted that mutations in the

NEB gene account for over 50% of cases of NM, whereas mutations in the

ACTA1 gene account for between 15%-25% of cases [

8]. NEB, known as the giant actin-binding protein because it has a molecular weight of between 600-800 kDa, plays a very important role in stabilizing and regulating the length of the actin filament [

9]. ACTA1 is the actin isoform predominantly found in the thin filaments of skeletal muscles and essential, along with myosin, for muscle contraction [

10].

The diagnosis is established from the clinical suspicion, since paraclinical studies such as creatinine kinase levels may be normal or slightly elevated and electromyography may show nonspecific myopathic changes. The diagnosis is confirmed histopathologically by muscle biopsy analysis, in which characteristic rod bodies (nemaline bodies) are found in the sarcoplasm, evidenced by modified Gomori stain [

1]. Increasingly the diagnosis is made or confirmed by molecular genetic testing for mutations in the genes known to cause NM.

The etiology of the disease remains unclear. The accumulation of nemaline bodies by itself does not explain the muscle weakness characteristic of the disease and could be only a secondary phenomenon of the main pathogenic process. In fact, no correlation has been observed between the severity of the disease and the degree of accumulation of nemaline bodies [

11]. In addition to nemaline bodies, pathological defects have been also observed in skeletal muscle fibers both in mouse models and in patients with NM: abundant, unevenly spaced, and with irregular morphology nuclei; interrupted nuclear envelope; impaired chromatin arrangement; and cytoskeletal disorganization [

12]. Due to the important role of the nuclear form and the envelope in the regulation of gene expression, and of the cytoskeleton in maintaining the integrity of the muscle fiber, it is likely that these alterations are responsible for some distinctive features of the disease, such as the disorder of the contractile filaments and the altered mechanical properties.

The disease has also been associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, specifically, with complex I dysfunction or deficiency [

13]. One hypothesis proposes that by disrupting the integrity of the thin filaments and, consequently, disrupting normal muscle function, less energy is used and there is a "down-regulation" of complex I activity and, therefore, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production [

13]. In addition, regarding the formation of nemaline rods, numerous rods were observed in some patients with complex I deficiency [

14]. It has been seen that the formation of these can be induced in muscle and non-muscle cells in vitro by several different cellular stressors [

15]. These data suggest that metabolic alterations during the formation and turnover of sarcomeres may induce the formation of nemaline rods. However, it is still unclear how these two pathological phenomena are related. Furthermore, interactions between mitochondria and the actin cytoskeleton have been linked to essential functions of this organelle [

16]. Thus, actin filaments primarily modulate mitochondrial dynamics [

17,

18], trafficking and autophagy [

19], but also mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism [

20]. Therefore, it is reasonable to deduce that the actin polymerization defects in NM such as

ACTA1 and

NEB mutations may affect mitochondrial function.

Animal and cell models are needed to better understand the mechanisms involved in the development of the disease. Currently, animal, and in vitro models of NM are being explored, specifically mouse and zebrafish models [

21]. Respect to cellular models, in addition to in vitro contraction studies of muscle fibers [

22], functional studies have been conducted in specific genetic mutations and their proteins in several cell lines, such as NIH3T3 fibroblasts, C2C12 myoblasts or Sol 8 myogenic cells that differentiate into myotubes [

23,

24]. Most patient mutations studied by cell transfection reveal cellular defects typical of the disease, such as actin aggregates and the formation of nemaline bodies seen in patients' muscle biopsies. On the other hand, regarding human cell lines of the disease, recently, two isogenic lines of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) derived from a patient with severe nemaline myopathy with a dominant heterozygous mutation in the

ACTA1 gene have been achieved [

25]. Alternatively, patient-derived skin fibroblasts can be easily obtained by small biopsies of the skin in a non-invasive way, have a great capacity for division and harbor the specific mutations of the patients [

26].

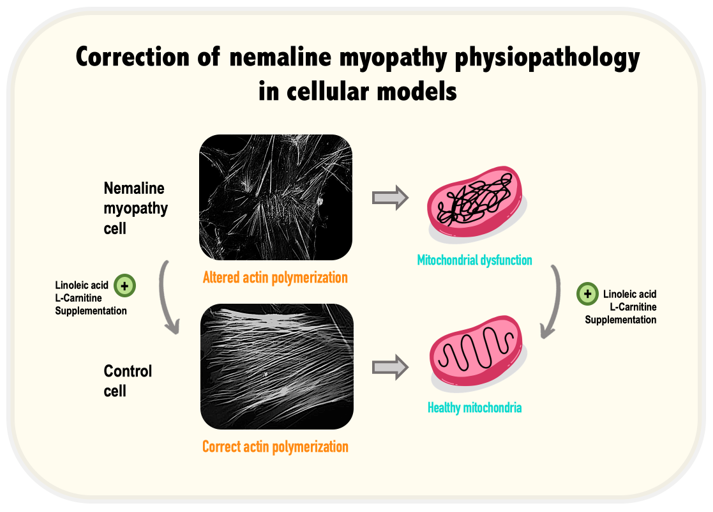

In this manuscript, we have evaluated whether fibroblasts derived from NM patients carrying ACTA1 and NEB mutations can be useful cellular models for studying disease pathophysiology. The work is based on the hypothesis that both affected proteins, ACTA1 and NEB, may participate in the formation and stabilization of actin filaments, and therefore, alterations of actin polymerization can be visualized in patient-derived fibroblasts. In addition, we examined the consequences of actin polymerization defects on mitochondrial function. Finally, we also evaluated the correction of all pathological alterations by mitochondrial targeting compounds such as linoleic acid (LA) and L-carnitine (LCAR).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

The subsequence antibodies were acquired from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom): Alpha Skeletal Muscle Actin (ab28052), Alpha tubulin (ab7291), NADH:Ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A9 (NDUFA9) (ab14713), cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV (COXIV) (ab14744), ATP synthase F1 subunit alpha (ATP5F1A) (ab1478), Voltage-depebdent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) (ab14734) and Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2) (ab68155). The next antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific (Whaltham, MA, United States)): Rho (A, B, C) (PAI-338), Rho-associated protein kinase 1 (ROCK1) (PA5-22262), Phospho-ROCK1 (PA5-36763) and NADH:Ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S1 (NDUFS1) (PA5-22309). RhoA (8789S), Vimentin (D21H3) and Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4) (52455S) were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, United States). Antibodies for beta actin (MBS448085) and Mitochondrially Encoded NADH:Ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit 1 (Mt-ND1) (6888S) were purchased from MyBioSource (San Diego, CA, United States). Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 2 (UQCR2) was supplied from US Biological (Salem, MA, United States). The following antibodies were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, United States): dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) (sc-32898), succinate dehydrogenase complex iron-sulfur subunit B (SDHB) (sc-271548) and Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD1) (sc-101523). Optic atrophy type 1 (OPA1) (HPA036926) was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (San Luis, MO, United States). Novus Biologicals (Centennial, CO, United States) provided Mitochondrially Encoded cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2 (Mt-CO2) (NBP1-778220). Trypsin, Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), Saponin, Tris-Base, 4ʹ,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) 4.5 g/l and 1 g/l glucose, L-glutamine, Pyruvate (Gibco), Penicillin:Streptomycin 10,000:10,000 (Gibco), Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Gibco), Mowiol 4-88 Mw (Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, United States)). Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, United States)). PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Rho Activation Assay Kit (Rf. 8820) (Cell Signaling Technology (Massachusetts, United States)). Rhodamine Phalloidin Reagent (Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom)). Acrylamide 37.5:1 solution, Clarity TM Western ECL substrate, electrophoresis buffer (TGS), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), Triton X-100, blot buffer (TG), Tween-20, DC Protein Assay Reagent A, B, S, (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. (Hercules, CA, USA)). 2-Isopropanol, Ethanol, Methanol, Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Ammonium Persulfate (APS), Glacial Acetic Acid, Potassium Hydroxide (KOH), Potassium Chloride (KCL) (Panreac (Barcelona, Spain)), Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). L-carnitine (sc-205727), Y27632 (sc-3536) and Paraformaldehyde (PFA) (sc-25326B) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, United States). Sigma-Aldrich (San Luis, MO, United States) supplied Linoleic acid (L1376).

2.2. Patients and cell culture

Four lines of fibroblasts derived from patient skin biopsies from the Pediatric Department of Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla, Spain were used. Two controls lines of primary human skin fibroblasts were purchased from ATCC. Patient 1 (P1) presents a heterozygous pathogenic variant c.133G>T (p.Val45Phe) in ACTA1 that causes a missense variant. The second patient (P2) is also heterozygous carrying changes in position c.760A>T (p.Asn254Tyr) in ACTA1. The third patient (P3) presents heterozygous pathogenic variants c.10321A>C (p.Thr3441Pro) and c.13669C>T (pArg4557*) in NEB. The fourth patient (P4) presents heterozygous pathogenic variants c.24407_24410dup (p.Leu8137Phefs*18) c.8425C>T (p.Arg2809*) in NEB.

Control values were represented as mean±SD of three control lines. Fibroblasts were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium DMEM (Gibco™, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco™, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 100 mg/ml penicillin/streptomycin. Fibroblasts were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. Experiments were performed with less than 12 passage fibroblasts cultures.

2.3. Immunoblotting

Western blotting was performed using standard methods. After protein transfer, the membrane was incubated with various primary antibodies diluted 1:1000 and then with the corresponding secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) at a 1:10000 dilution. The Immun-Star HRP substrate kit (Biorad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was used to identify particular proteins.

2.4. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

ACTA1 and NEB gene expression in fibroblasts was analysed by qPCR using mRNA extracts. Using TrizolTM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), mRNA was extracted in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. To obtain complementary DNA (cDNA), RNA was retrotranscribed using the Iscript cDNA synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States). TB GreenTM Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara Bio Europe S.A.S., Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) was used for qPCR. CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to detect accurate quantification of gene expression. ACTA1 primers were 5’-CCATTTATGAGGGCTACGCG-3’ (Forward primer) and 5’- CAGCTTCTCCTTGATGTCGC-3’ (Reverse primer) amplifying a sequence of 158 nucleotides. NEB primers were 5’- GAAACCAGACCACAGCCTTG-3’ (Forward primer) and 5’-TAGGGCATCTTTCACCGTGT-3’ (Reverse primer) amplifying a sequence of 224 nucleotides. Human α Tubulin was used as a housekeeping control gene and the primers were 5’-GCAGCATTTGTAGCAGGTGA-3’ (Forward primer) and 3’- GCATTGCCAATCTGGACAC -5’ (reverse primer). All primer pairs were previously validated by PCR, followed by gel electrophoresis, confirming correct product amplification.

2.5. Active RhoA assay

Fibroblasts were grown on 75 cm2 flasks in DMEM containing 10% FBS. According to the manufacturer’s recommendations, media were removed, and cells were washed twice using ice-cold PBS 1X and the cell lysate was collected using Lysis/Binding/Wash buffer supplemented 1X protease inhibitor cocktail provided by the Active Rho Detection Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA, Cat. 8820). After centrifuging at 16000 g at 4°C for 15 min, lysate protein concentration was determined using BCA Protein Assay Kit and a 1 mg/ml lysate in 1X Lysis/Binding/Wash buffer was prepared. After making the cell lysate stock, protein then was incubated with GST Rhotekin-RBD affinity beads at 4°C for 1 h with gentle rocking. Bound proteins (Active RhoA form) were washed and prepared with SDS Sample Buffer and then, Western blotting analysis was carried out according to the previously mentioned protocol.

2.6. Immunofluorescence microscopy

Fibroblasts were grown on 1 mm width (Goldseal No. 1) glass coverslips for 24–48h in DMEM containing 20% FBS. Cells were rinsed once with PBS 1X, fixed in 4% PFA for 5 min at room temperature and permeabilized in 0.1% saponin for 5 min. Then, cells were blocked with blocking solution (1% BSA in PBS 1X). For immunostaining, glass coverslips were incubated with primary antibodies diluted 1:100 in blocking solution, overnight at 4°C. Unbound antibodies were removed by washing the coverslips with PBS 1X (three times, 5 min). The secondary antibody, a FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse antibody, or a tetramethyl rhodamine goat anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes), diluted 1:400 in blocking solution, were added and incubated for 2h at room temperature. Coverslips were then rinsed with PBS 1X for 5 min, incubated for 1 min with PBS 1X containing DAPI (1 μg/ml), and washed with PBS (three 5-min washes). Finally, the coverslips were mounted onto microscope slides using Mowiol aqueous mounting medium and analysed using a DeltaVision system (Applied Precision; Issaquah, WA) with an Olympus IX-71 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) as well as the colocalization.

2.7. Immunofluorescence staining of cytoskeletal F-actin

Briefly, fibroblasts were seeded on 1 mm coverslips (Goldseal No. 1) for 24–48 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Next day after reaching to 50% confluency, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 minutes at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.1% Saponin for 15 minutes. Then, cells were washed with PBS 1X twice and incubated with Rhodamine-Phalloidin, a high affinity F-actin probe conjugated to red-orange fluorescent dye, at 1 μg/ml for 30 minutes. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS 1X three times and incubated with DAPI at 1 μg/ml for 5 min to nuclei staining. Subsequently, cells were washed three times with PBS 1X for 5 minutes. Finally, the coverslips were mounted on microscope slides with Mowiol aqueous mounting medium. After staining, images were taken by a DeltaVision system with an Olympus IX-71 fluorescence microscope with a 40× oil objective. Images were analysed by Fiji-ImageJ software.

In order to evaluate the state of actin filaments, the percentage of cells with correct actin polymerization and the length of actin filaments present in each cell were examined. To estimate the percentage of cells with correct actin polymerization for each patient, three counts of 100 cells per sample were performed; the values of these counts were compared among themselves and between the different samples. Cells with correct actin polymerization were considered those cells that presented actin filaments similar to those presented by control cells. The length of actin filaments present in each cell were measured by Fiji-ImageJ software. To execute this, the filaments of 30 cells of each cell line were measured in triplicate. The actin filament length values represented in the figures are expressed as the average of the measured filament lengths.

2.8. Bioenergetics and Oxidative Stress Analysis

Mitochondrial respiratory function of control and NM fibroblasts were measured using mito-stress test assay by XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA). Cells were seeded at a density of 15000 cells/well in XF24 cell culture plates in 150 μl growth medium (DMEM medium containing 20% FBS) and placed in 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. After 24h incubation, growth medium from each well was removed, leaving 50 μl of media. Then, cells were washed twice with 1 ml of pre-warmed assay medium (XF base medium supplemented with 10-mM glucose, 1-mM glutamine, and 1-mM sodium pyruvate; pH 7.4) and 450 μl of assay medium (500 μl final) was added. Cells were incubated in 37°C incubator without CO2 for 1h to allow pre-equilibrating with the assay medium. Mitochondrial functionality was evaluated by sequential injection of four compounds that affect bioenergetics. The final concentrations of injections were 1 μM oligomycin, 2 μM FCCP (carbonyl cyanide-4-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone), and 2.5 μM rotenone/antimycin A. The best concentration of each inhibitor and uncoupler, as well as the optimal cells seeding density, were determined in preliminary assays. A minimum of five wells per treatment were utilized in any given experiment. This assay allowed for an estimation of basal respiration, ATP production, maximal respiration, and spare respiratory capacity parameters.

2.9. Mitotracker staining. Analysis of Mitochondrial Network

Cells were stained with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (100 nM, 45 min, 37°C), a mitochondrial potential-dependent dye, and examined by fluorescence microscopy. The amount of mitochondrial fragmentation was evaluated using the Fiji software. For each experimental condition, a total of 100 cells collected in three different experiments were used to calculate the number of small, rounded mitochondria per cell. Length or ratio between the major and minor axis of the mitochondrion, degree of circularity and percentage of rounded/tubular mitochondria were considered.

2.10. Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, fibroblasts mitochondrial superoxide generation was measured using 5 μM MitoSOX™ Red. Previously, cells were seeded and grown on coverslips until reaching 80% of confluency. Mitochondrial localization of MitoSOX™ Red signal was confirmed in combination with MitoTracker™ Deep Red FM staining (100 nM, 45 min, 37°C), an in vivo mitochondrial membrane potential-independent probe. Cells' nuclei were stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI. After staining, images were taken by a DeltaVision system with an Olympus IX-71 fluorescence microscope with a 40× oil objective. Images were analysed by Fiji-ImageJ software.

2.11. Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted in accordance with our research group's previous description [

27]. In situations where there were few events (n<30), we employed non-parametric statistics that do not make any distributional assumptions [

28]. In these cases, multiple groups were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis test. We used parametric tests when the number of events was greater (n>30). In these instances, a one-way ANOVA was used to compare multiple groups. Statistical analysis were conducted using the GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The information is presented as the mean±SD values or as an example from three independent experiments. p-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

4. Discussion

Nemaline myopathy (NM) encompasses a large spectrum of rare genetic myopathies characterized by hypotonia, weakness and depressed or absent deep tendon reflexes. Histology examination of muscle biopsy typically shows the presence of nemaline rods. In this work, we explored the pathophysiological alterations in NM using patient-derived fibroblasts patients carrying ACTA1 and NEB mutations. Mutant fibroblasts manifest alterations in actin filament polymerization associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition, we identified two compounds, linoleic acid (LA) and L-carnitine (LCAR) that restored actin polymerization and corrected bioenergetics deficiency in both ACTA1 and NEB mutant fibroblasts.

Actin is a widely distributed, highly conserved protein that plays a key role in the cytoskeleton and is involved in a variety of biological processes. In addition to providing structural support for the cell, actin plays a role in cell migration, cell division and organelle trafficking [

29,

30]. Actin's role was first described in muscle contraction in 1942 by A. Szent-Györgyi [

31]. Actin is found in two different forms: G-actin, which is the globular monomeric actin that polymerizes to form filamentous F-actin [

32].

Six different actin isoforms are expressed in a higher mammal [

33]. A group of structurally related genes with highly homologous nucleotide sequences that share a common precursor code for different isoforms of actin [

34]. Actin isoforms differ by four amino acid residues localized at positions 1, 2, 3, and 9 of the N-terminus [

33]. Six human actin genes - α-skeletal (

ACTA1), α-cardiac (

ACTC1), α-smooth muscle (

ACTA2), γ-smooth muscle (

ACTG2), β-cytoplasmic (

ACTB), γ-cytoplasmic (

ACTG1) - are localized on the different chromosomes [

35]. The seventh actin isoform, β-actin-like protein 2 (ACTBL2), has been recently identified. It is a member of the non-muscle actin class, along with γ- and β-cytoplasmic actins, but its expression is extremely low [

36]. Cytoplasmic actins are expressed in mammalian cells in various proportions [

37].

Conversely, nebulin (NEB) is a very large filamentous protein ranging in size from 600 to 900 kDa that is a crucial part of the thin filament in skeletal muscle. Because of its size and the difficulty in obtaining nebulin in its native state from muscle, its functions are still largely unknown [

38].

In our work, we have demonstrated for the first time that both actin 1 alpha (ACTA1) and nebulin (NEB) are expressed in dermal fibroblasts allowing the investigation of pathological alterations induced by mutant proteins in an easy-to-use cellular model. In addition, both proteins indeed participate in actin filament polymerization in dermal fibroblasts since both mutant proteins ACTA1 and NEB caused defects in actin polymerization in NM cells.

One interesting finding in our work is that NM patient-derived fibroblasts exhibited alterations in mitochondrial network morphology associated with down-regulation of the expression levels of mitochondrial proteins and deficient mitochondrial bioenergetics suggesting a marked mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria are organelles that undergo dynamic changes through fission (division into two or more independent organelles) and fusion (formation of a single structure) events, biogenesis, and mitophagy (clearance of damaged organelles) [

39,

40]. These processes regulate mitochondrial morphology, number, and turnover, respectively, referred to as mitochondrial quality control [

41]. Mitochondrial fusion and fission cycles are adaptive changes controlled by dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), mitofusin 1 (MFN1), mitofusin 2 (MFN2), and optic atrophy protein 1 (OPA1) in mammalian cells [

42]. Mitochondrial fusion increases mitochondrial metabolism, while mitochondrial fission contributes to mitochondrial apoptosis and is considered a prerequisite for mitophagy [

43]. Mitophagy removes selectively old or dysfunctional mitochondria through its sequestration and engulfment for the subsequent lysosomal degradation [

44]. Different stresses, such as oxidative damage, hypoxia, mitochondrial depolarization or mitochondrial DNA damage enhance mitophagy [

45,

46]. Accumulating evidence reveals that mitophagy is required to maintain skeletal muscle plasticity by controlling mitochondrial biogenesis turnover, and mitochondrial proteostasis [

47,

48], in order to increase mitochondrial activity and remodeling during early myogenic differentiation [

49,

50,

51].

Cytoskeletal components, particularly microtubules and F-actin, work collaboratively to regulate mitochondrial processes of fission/fusion, mitophagy and morphology in response to extracellular stressors [

52]. Mitochondrial motility is also dependent on the coordinated action of cytoskeletal elements, especially microtubules and F-actin, which distribute and anchor the organelles to the proper locations within the cell [

53]. Specifically, it has been suggested that alterations to the cytoskeleton can affect mitochondria, resulting in functional modifications in the organelle. The primary role of mitochondria in cells is energy production, which is closely correlated with the regulation of their morphology, organization, and distribution by the cytoskeleton [

54]. Thus, cytoskeletal abnormalities of actin polymerization in NM can subsequently lead to impairments in mitochondrial respiration, thereby accelerating disease progression.

The process of mitochondrial fission involves the formation of ring-shaped DRP1 oligomers on the outer membrane of the mitochondria, which are then constricted by hydrolysis [

55]. In order to facilitate the subsequent recruitment of dynamin-2, which coordinates membrane scission, DRP1 rings tighten and constrict mitochondria. [

56]. Nevertheless, in order to reduce their cross-sectional diameter, mitochondria must first go through a pre-constriction step because they are frequently thicker than DRP1 rings. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) tubules are wrapped and tightened around mitochondria to produce this pre-constriction. Growing evidence points to actin polymerization as the primary force behind the ER's bending around the mitochondria [

57,

58].

In addition, F-actin at Mito/ER contacts may prime DRP1 to form functional oligomers on the outer membrane of the mitochondria [

59]. In vitro GTPase assays show that DRP1 activity is greatly enhanced in the presence of actin filaments [

59]. Taken together, these observations suggest that filamentous actin acts as an important regulator of inner and outer mitochondrial membrane fission.

Moreover, the actin cytoskeleton controls the movement of mitochondria in simple eukaryotes like budding yeast [

60] and is necessary for the accurate inheritance of mitochondria during cytokinesis [

61]. Microtubules in metazoans are responsible for coordinating long-distance mitochondrial movement, but the actin cytoskeleton is also involved in regulating mitochondrial distribution, coordinating anchoring, and coordinating short-distance mitochondrial motility [

52].

In addition, actin cytoskeleton plays an important role on mtDNA expression and maintenance [

62]. The mammalian mitochondrial DNA genome (mtDNA) contains 37 genes organized in compact DNA:protein complexes called nucleoids [

63,

64], whose expression requires a high degree of coordination with the nuclear genome [

65]. In yeast, the ERMES (ER-mitochondria encounter structure) complex regulates the stability and organization of mtDNA in nucleoids in an actin-dependent manner [

66]; in mammals, MERCs (Mitochondria Endoplasmic Reticulum Contact Sites) are spatially-linked to mitochondrial nucleoids, regulating their distribution, division and active transportation by the microtubules [

67]. Furthermore, recent super-resolution microscopy-based studies probed the presence of β-actin-containing structures inside the mitochondrial matrix [

68].

Furthermore, β-actin-deficient human cells were more susceptible to stress brought on by a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ), as well as altered mtDNA mass and nucleoid organization [

69], indicating a regulatory function in mtDNA transcription and quality control. In addition to actin, myosin II has been linked to isolated mitochondrial nucleoids, and its silencing results in mtDNA alterations [

62]. These evidences support the role of actin and actin-binding proteins in mitochondrial nucleoid segregation and mtDNA transcription and maintenance, likely through formation of a “mitoskeleton” network supporting mtDNA inheritance.

Additionally, the complete activation of metabolic pathways that subsequently control mitochondrial function depends on actin filaments. For example, direct binding of glycolytic enzymes like glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase or aldolase to F-actin can activate them [

70]. Interestingly, in brain mitochondria actin regulates the retention of cytochrome c between respiratory chain complexes III and IV by its direct association with both complexes, and inhibition of actin polymerization with cytochalasin b enhanced mitochondrial respiration through increased complex IV activity [

71]. Recently, proteomic analysis using NEB [

72] and ACTA1 [

73] mice models revealed perturbations in several cellular processes, including mitochondrial dysfunction and changes in energetic metabolism and stress-related pathways. Abnormal mitochondrial distribution, reduced mitochondrial respiratory function, increased mitochondrial membrane potential, and abnormally low ATP content were all revealed by structural and functional studies.

In our work we have also identified two compounds, LA and LCAR, that improving mitochondrial bioenergetics were able to restore actin polymerization.

LA is a carboxylic acid composed of 18 carbon atoms and three cis double bonds (18:2ω6), and is an essential fatty acid indispensable to the human body and therefore, it must be ingested through diet [

74,

75]. Pharmacological studies have shown that LA has a wide range of pharmacological effects such as anti-metabolic syndrome, antiinflammatory, anticancer, antioxidize, neuroprotection, and the regulation of the intestinal flora [

76,

77,

78]. LA is a major component of cardiolipin (CL), which is a specific inner-mitochondrial membrane phospholipid that is important for optimal mitochondrial function including respiration and energy production [

79]. Furthermore, this phospholipid participates in morphology and stability of mitochondrial cristae, fission and fusion-mediated mitochondrial quality control and dynamics, mitophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis and protein import, and multiple mitochondrial steps of the apoptotic process [

79]. Due to its high content of unsaturated fatty acids and its location in the IMM near to electron transport chain (ETC) complexes, the main sites of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, CL is particularly prone to peroxidation, an event that may affect many CL-dependent reactions and processes [

80,

81,

82]. In addition, the accumulation of oxidized CL in the OMM serves as important signaling platform during the apoptotic process, resulting in the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and in the release of cytochrome c (cyt c) from mitochondria to the cytosol [

83,

84].

Specifically, CL and its LA content are known to be positively associated with cytochrome c oxidase (COX) activity [

85] thereby making this lipid molecule an essential factor related to mitochondrial health and function. Structural studies have shown that CL is important for stabilization (i.e., the assembly of complex subunits) of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complex I (CI), complex II (CII), complex III (CIII), and complex IV (CIV) [

86,

87,

88,

89]. On the other hand, a decrease in CL levels by low dietary intake of LA promotes the disassembly of these mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes [

90]. In contrast, LA-enriched diet increased mitochondrial CL, and OXPHOS protein levels [

91]. Additionally, it was recently discovered that cardiolipin is necessary for the respiratory chain to organize into supramolecular assemblies [

92]. Furthermore, incubation of cells with different concentrations of LA led to a dose- and time-dependent increase of cardiolipin levels [

93].

It is conceivable that LA supplementation by increasing cardiolipin levels may positively impact the activity of a variety of mitochondrial proteins and enzymes, including the electron transport chain (ETC) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes, thus increasing mitochondrial function and dynamics. Furthermore, LA stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis signaling by the upregulation of PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) in C2C12 cells [

94].

In addition of its cardiolipin dependent actions, LA also promotes an increase of fascin expression, an actin crosslinker globular protein that generates actin bundles built of parallel actin filaments, which mediate formation and stability of cellular protrusions including microspikes, stress fibers, membrane ruffes, and filopodia [

95]. In this respect, LA is found to induce membrane ruffling and phagocytic cup formation along with cytoskeletal rearrangement in microglia [

96]. Furthermore, LA has many effects on cytoskeleton proteins in general and actin filaments in particular. For instance, it has been reported that LA enhances cell migration by altering the dynamics of microtubules and the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton at the leading edge [

97]. Moreover, LA may activate the RhoA/ROCK pathway and therefore, may facilitate actin polymerization. Thus, it has been shown that LA increased Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1) expression and phosphorylation of ROCK and Myosin Phosphatase Target Subunit 1 (MYPT-1), a distal signal of ROCK [

98].

On the other hand, LCAR, a well-known dietary supplement which is needed for the translocation of fatty acids into the mitochondrial compartment for β-oxidation [

99,

100] and has a role in carbohydrate metabolism possesses this potential to raise the mitochondrial biogenesis, increasing various mitochondrial components’ gene expression and maintains their function via supplying their respective substrates and protecting them against insults including the toxic products’ or reactive radicals’ accumulation [

101,

102]. Therefore, LCAR as natural compounds that can enhance cellular energy transduction may have therapeutical potential in NM. Studies in recent years have demonstrated the protective effects of LCAR treatment on mitochondrial functions [

102]. Consistent with this hypothesis, a premature boy with a congenital form of nemaline myopathy due to mutation in the

ACTA1-gene showed decreased LCAR levels in the eighth week of life. After sufficient oral LCAR substitution he improved gradually [

103]. Furthermore, LCAR ameliorates congenital myopathy in a tropomyosin 3 de novo mutation transgenic zebrafish [

104]. Furthermore, LCAR significantly reduced statin-induced myopathy [

105] and skeletal muscle atrophy in rats [

106]. In addition, LCAR improved exercise performance in human patients with mitochondrial myopathy [

107] and may prevent age-associated muscle protein degradation and regulate mitochondrial homeostasis [

108].

As actin polymerization is dependent of ATP levels. During cycles of actin assembly and disassembly, actin monomers polymerize into filaments in an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-bound state, and the polymerization of actin is followed by the irreversible hydrolysis of ATP to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and phosphate (6).

Thus, in eukaryotic cells, the actin cytoskeleton's turnover between its monomeric and filamentous forms is a significant energy drain. It is not surprising that lower ATP levels slow actin polymerization since ATP is essential for actin polymerization. Reduced ATP levels most likely cause an abundance of ADP-G-actin versus ATP-G-actin. The lower actin polymerization rate observed in the ATP-deficient cells may be explained by the fact that ADP-G-actin polymerizes at a substantially slower rate than ATP-G-actin [

109,

110]. Actin filament assembly and dynamic behavior are mediated in large part by binding with ATP and ATP hydrolysis.

In addition, RhoA activity which regulates actin polymerization decreased in parallel with the concentration of ATP and GTP during depletion by mitochondrial inhibitors recovered rapidly when cells were returned to normal culture conditions [

111], suggesting that ATP and GTP levels modulate RhoA activation.

In this regard, mitochondrial dysfunction in NM cells may cause ATP deficiency and aggravate the impairment of actin polymerization. LCAR and/or LA supplementation may boost mitochondrial ATP formation and consequently may facilitate actin filament formation by increasing actin monomers bound to ATP and RhoA activation by increasing GTP levels.

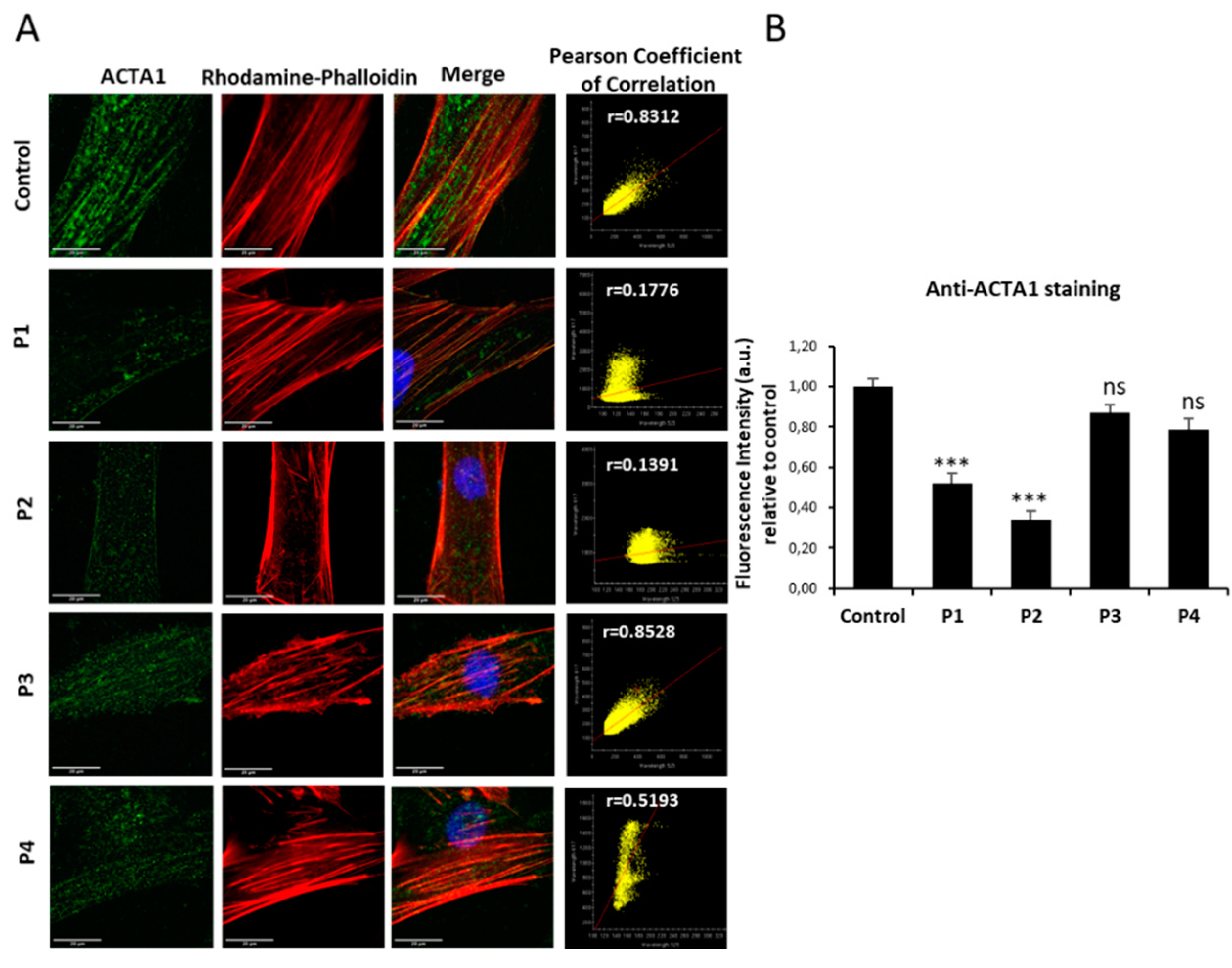

Figure 1.

ACTA1 expression levels by immunofluorescence microscopy in control and NM cells. (A) Control (C1) and NM cells (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were immunostained against ACTA1 and visualized under fluorescence microscope. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. The colocalization between ACTA1 signal and F-actin staining by Rhodamine-Phalloidin was analysed by Pearson correlation coefficient. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated with DeltaVision system. A positive correlation was considered when Pearson coefficient > 0.75. (B) Quantification of ACTA1 signal. Images were taken using the 60x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. ***p<0.001 between NM and control cells. Scale bars=20 µm.

Figure 1.

ACTA1 expression levels by immunofluorescence microscopy in control and NM cells. (A) Control (C1) and NM cells (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were immunostained against ACTA1 and visualized under fluorescence microscope. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. The colocalization between ACTA1 signal and F-actin staining by Rhodamine-Phalloidin was analysed by Pearson correlation coefficient. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated with DeltaVision system. A positive correlation was considered when Pearson coefficient > 0.75. (B) Quantification of ACTA1 signal. Images were taken using the 60x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. ***p<0.001 between NM and control cells. Scale bars=20 µm.

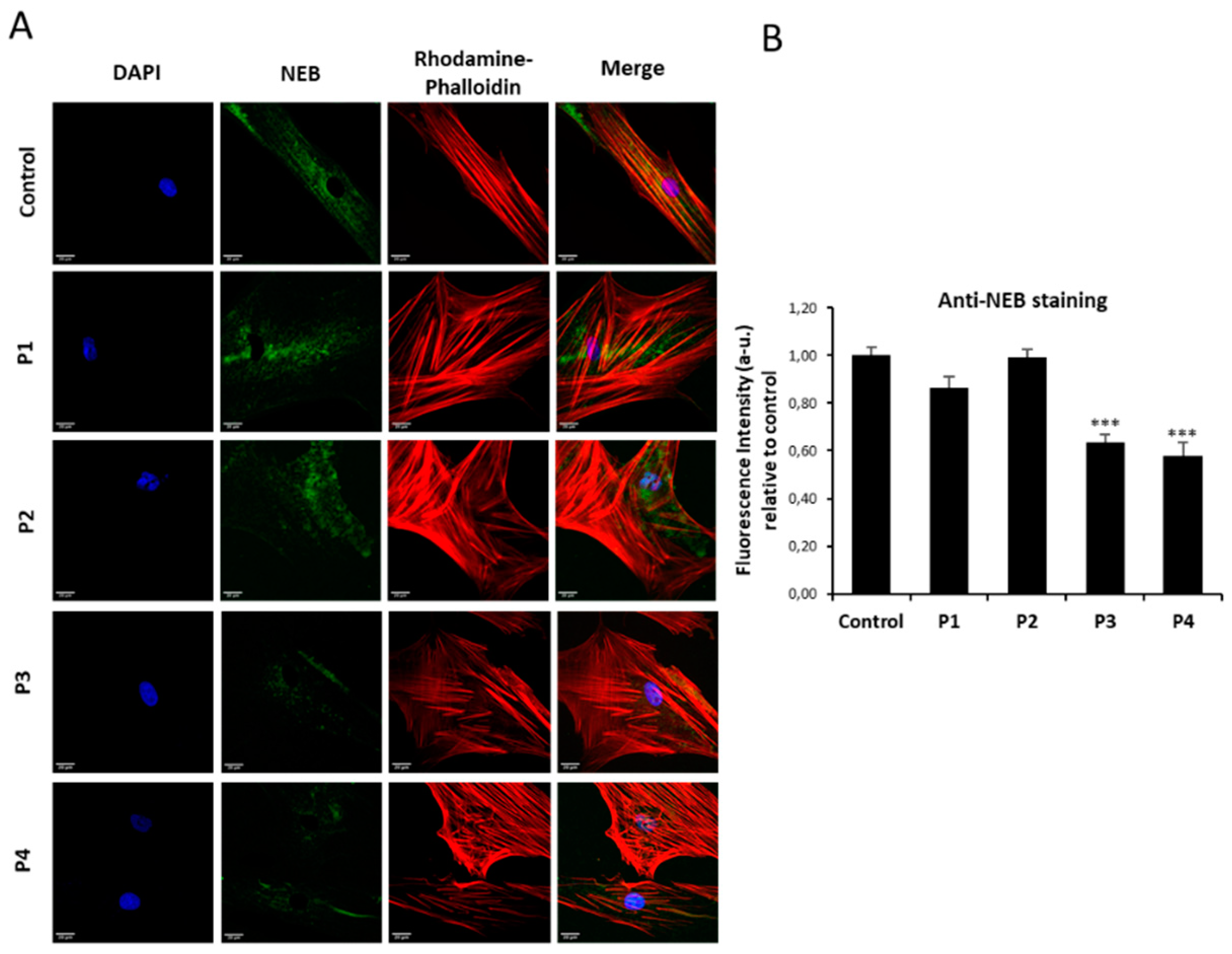

Figure 2.

NEB expression levels by immnunofluorescence microscopy in control and NM cells. (A) Control (C1) and NM cells (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were immunostained against NEB and visualized under widefield fluorescence microscope. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. (B) Quantification of NEB signal. Images were taken using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. Scale bars=20 µm.

Figure 2.

NEB expression levels by immnunofluorescence microscopy in control and NM cells. (A) Control (C1) and NM cells (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were immunostained against NEB and visualized under widefield fluorescence microscope. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. (B) Quantification of NEB signal. Images were taken using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. Scale bars=20 µm.

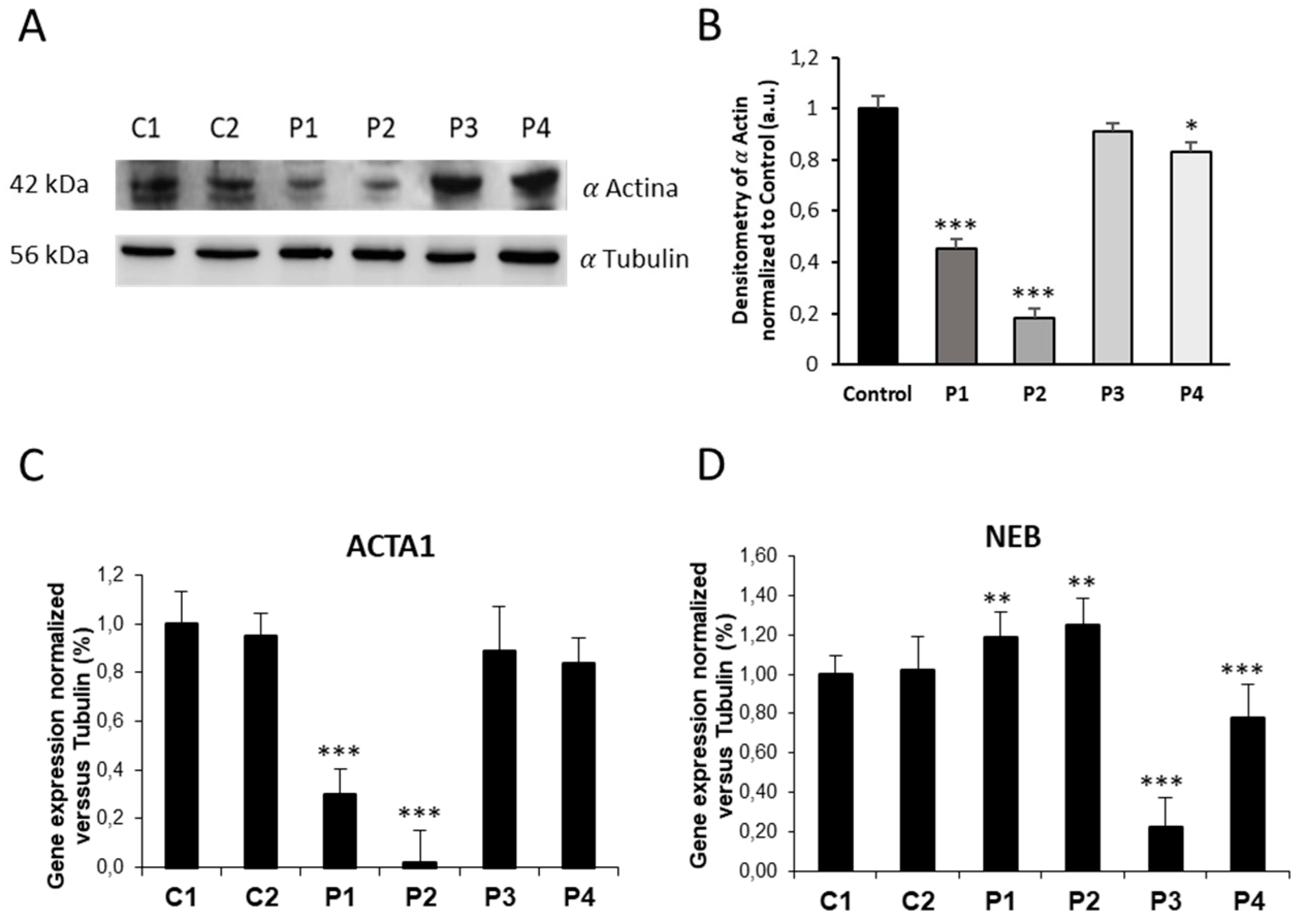

Figure 3.

ACTA1 and NEB expression levels in control and NM cells. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against ACTA1 and α Tubulin, which was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of the Western blotting. (C) ACTA1 gene expression quantified by RT-PCR. Results were normalized to α Tubulin gene expression. (D) NEB gene expression quantified by RT-PCR. Results were normalized to α Tubulin gene expression. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM cells and controls. a.u., arbitrary units.

Figure 3.

ACTA1 and NEB expression levels in control and NM cells. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against ACTA1 and α Tubulin, which was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of the Western blotting. (C) ACTA1 gene expression quantified by RT-PCR. Results were normalized to α Tubulin gene expression. (D) NEB gene expression quantified by RT-PCR. Results were normalized to α Tubulin gene expression. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM cells and controls. a.u., arbitrary units.

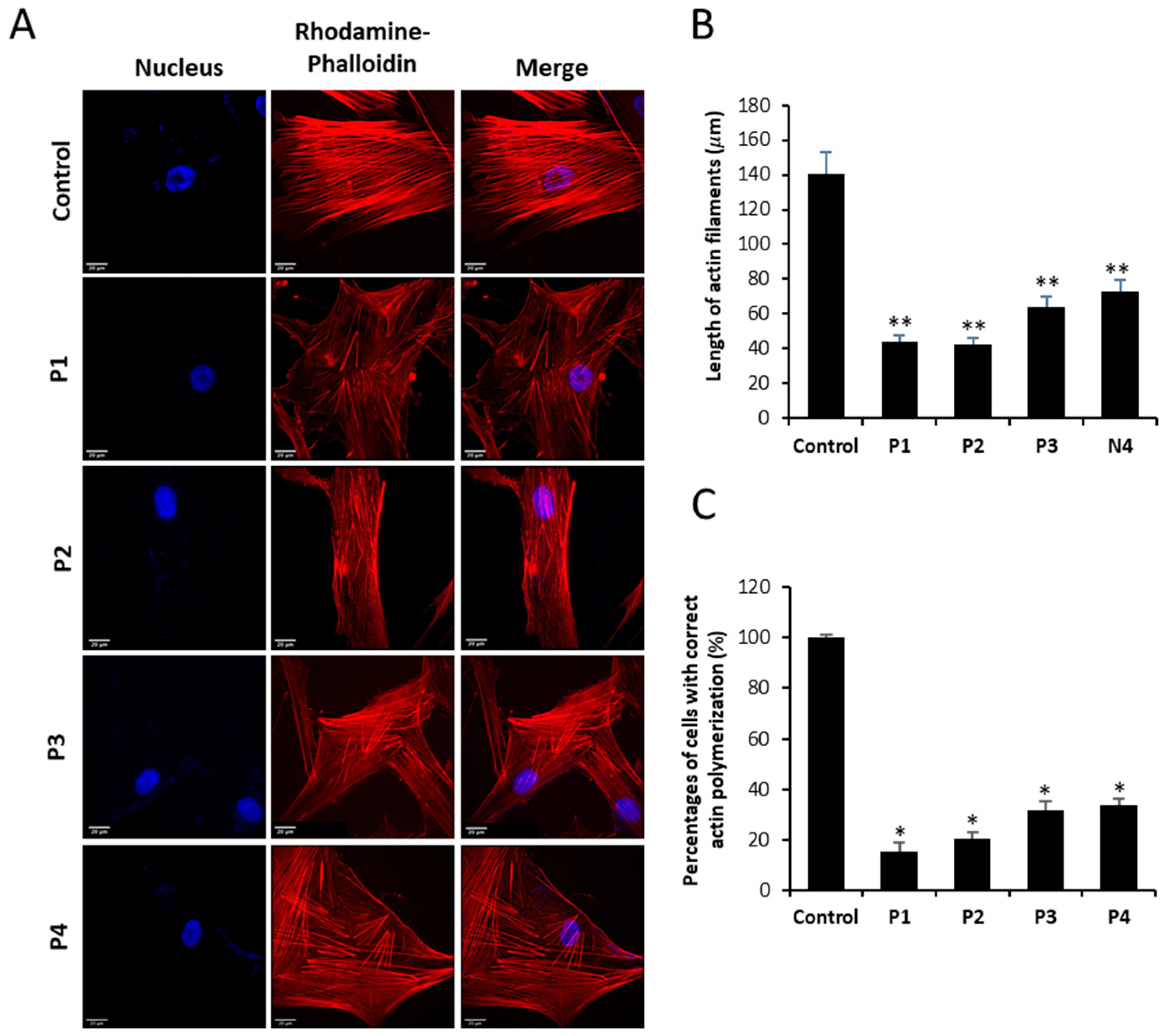

Figure 4.

Actin staining by Rhodamine-Phalloidin of Control and NM fibroblasts. (A) Control and NM fibroblasts, P1 and P2 (mutation in ACTA1) and P3 and P4 (mutation in NEB) were stained with Rhodamine-Phalloidin and visualized under widefield fluorescence microscope. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) presented smaller and unstructured actin filaments compared to control fibroblasts. Images were taken using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. (B) Measurement of the length of actin filaments (𝜇m). The length of the actin filaments was measured in triplicate with the ImageJ software in 30 images. (C) Percentage of cells with correct actin polymerization. Three counts of 100 cells per sample were performed. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Figure 4.

Actin staining by Rhodamine-Phalloidin of Control and NM fibroblasts. (A) Control and NM fibroblasts, P1 and P2 (mutation in ACTA1) and P3 and P4 (mutation in NEB) were stained with Rhodamine-Phalloidin and visualized under widefield fluorescence microscope. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) presented smaller and unstructured actin filaments compared to control fibroblasts. Images were taken using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. (B) Measurement of the length of actin filaments (𝜇m). The length of the actin filaments was measured in triplicate with the ImageJ software in 30 images. (C) Percentage of cells with correct actin polymerization. Three counts of 100 cells per sample were performed. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. Scale bar = 20 µm.

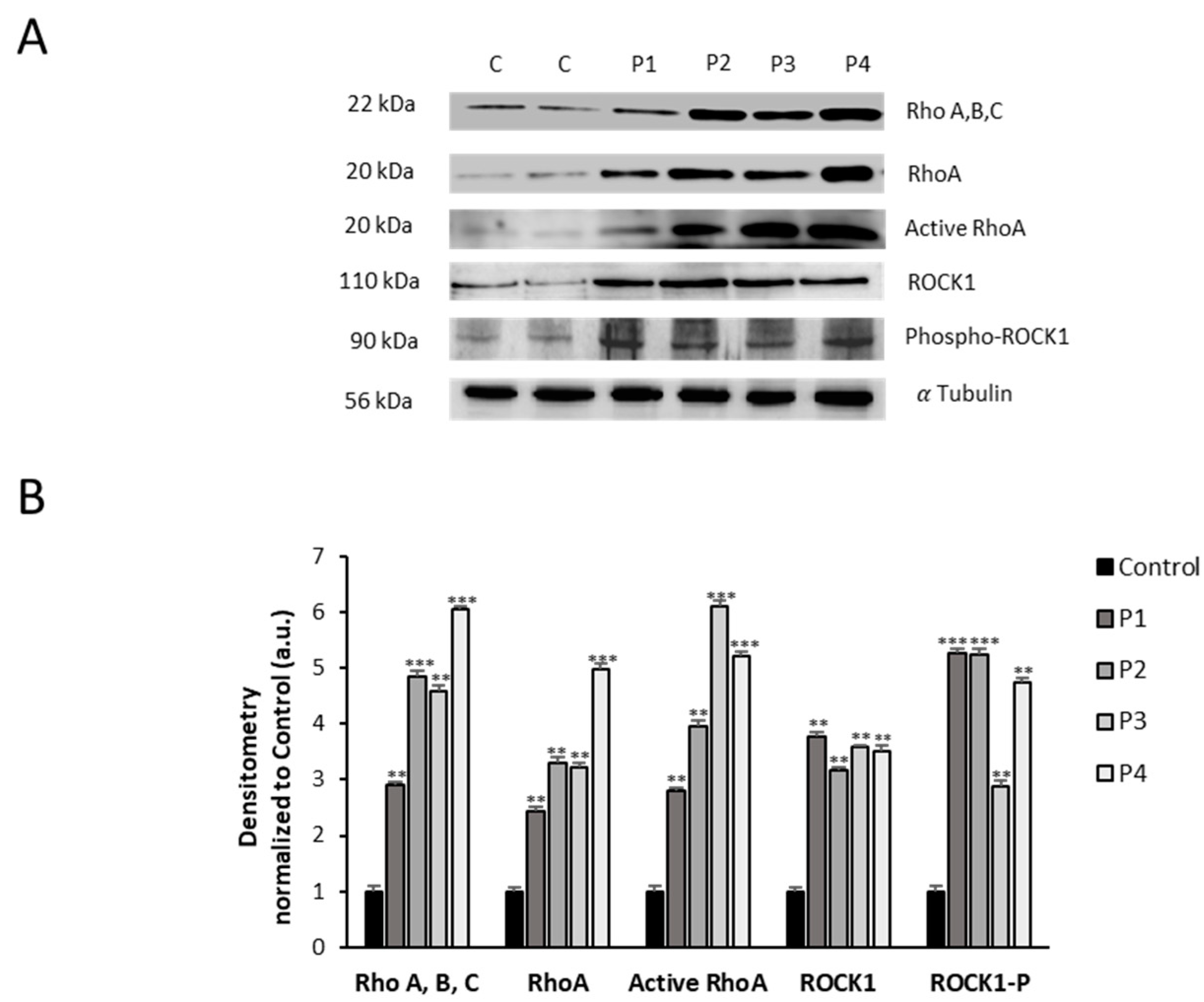

Figure 5.

Expression level of RhoA/ROCK pathway in NM cells. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against Rho (A, B, C), RhoA, Active RhoA purified by Active Rho Detection Kit as described in Material and Methods, ROCK1, phospho-ROCK1 and α Tubulin, which was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For controls cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. A.U., arbitrary units.

Figure 5.

Expression level of RhoA/ROCK pathway in NM cells. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against Rho (A, B, C), RhoA, Active RhoA purified by Active Rho Detection Kit as described in Material and Methods, ROCK1, phospho-ROCK1 and α Tubulin, which was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For controls cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. A.U., arbitrary units.

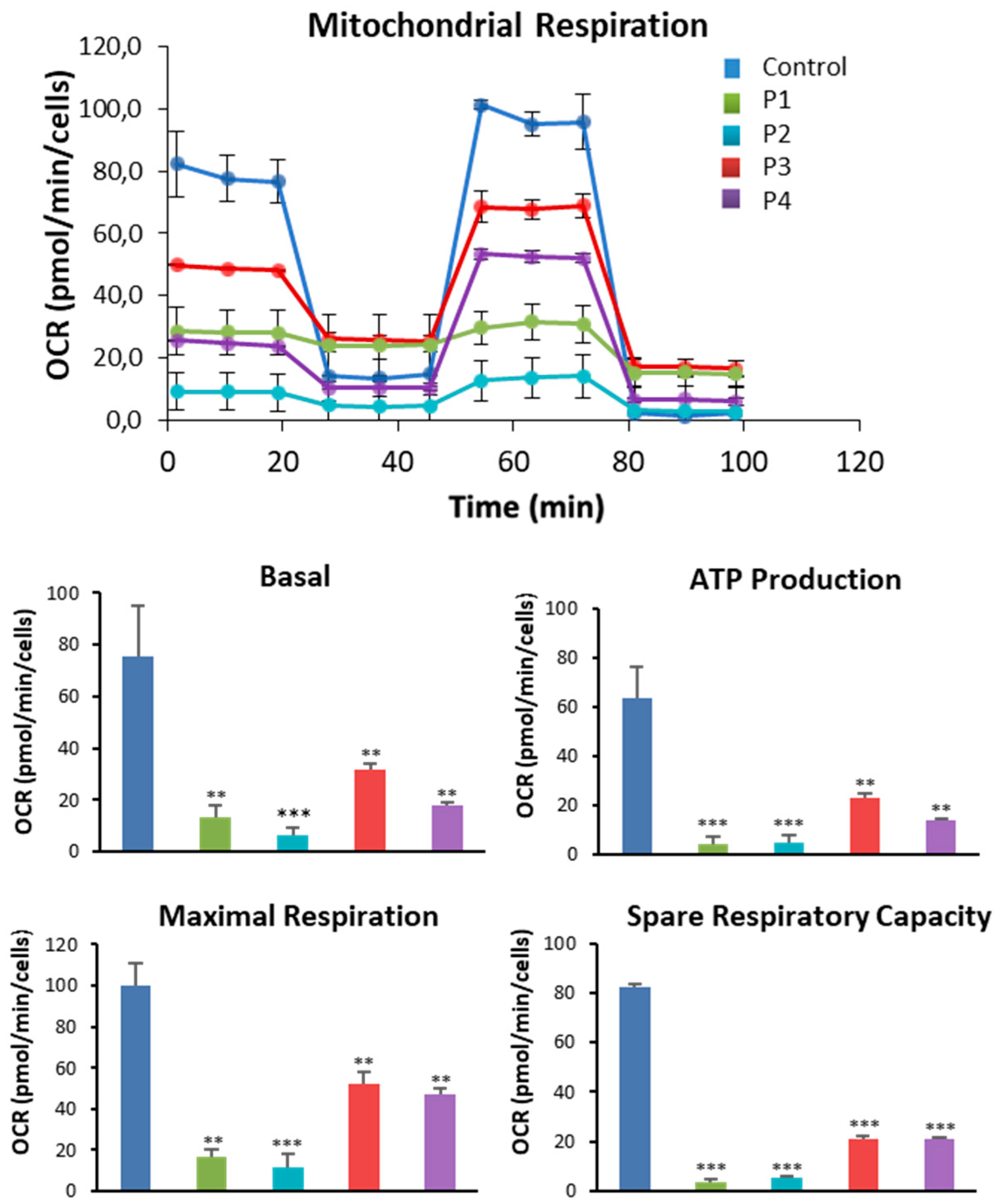

Figure 6.

Bioenergetics analysis of control and NM fibroblasts. Basal and maximal respiration, Mitochondrial ATP production and Spare Respiratory capacity were determined in controls (C1 and C2) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) by using the Seahorse analyzer as described in Material and Methods. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells.

Figure 6.

Bioenergetics analysis of control and NM fibroblasts. Basal and maximal respiration, Mitochondrial ATP production and Spare Respiratory capacity were determined in controls (C1 and C2) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) by using the Seahorse analyzer as described in Material and Methods. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells.

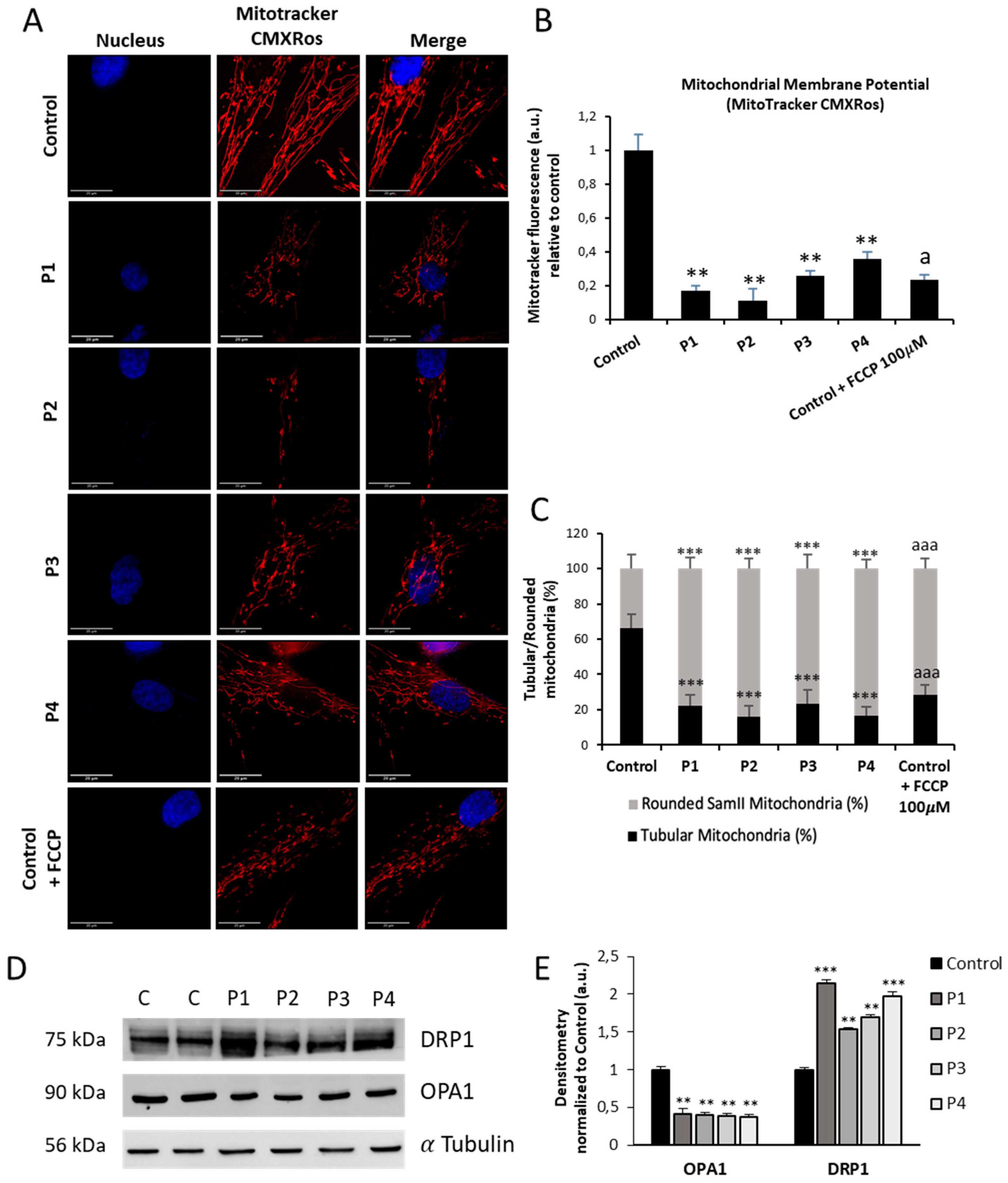

Figure 7.

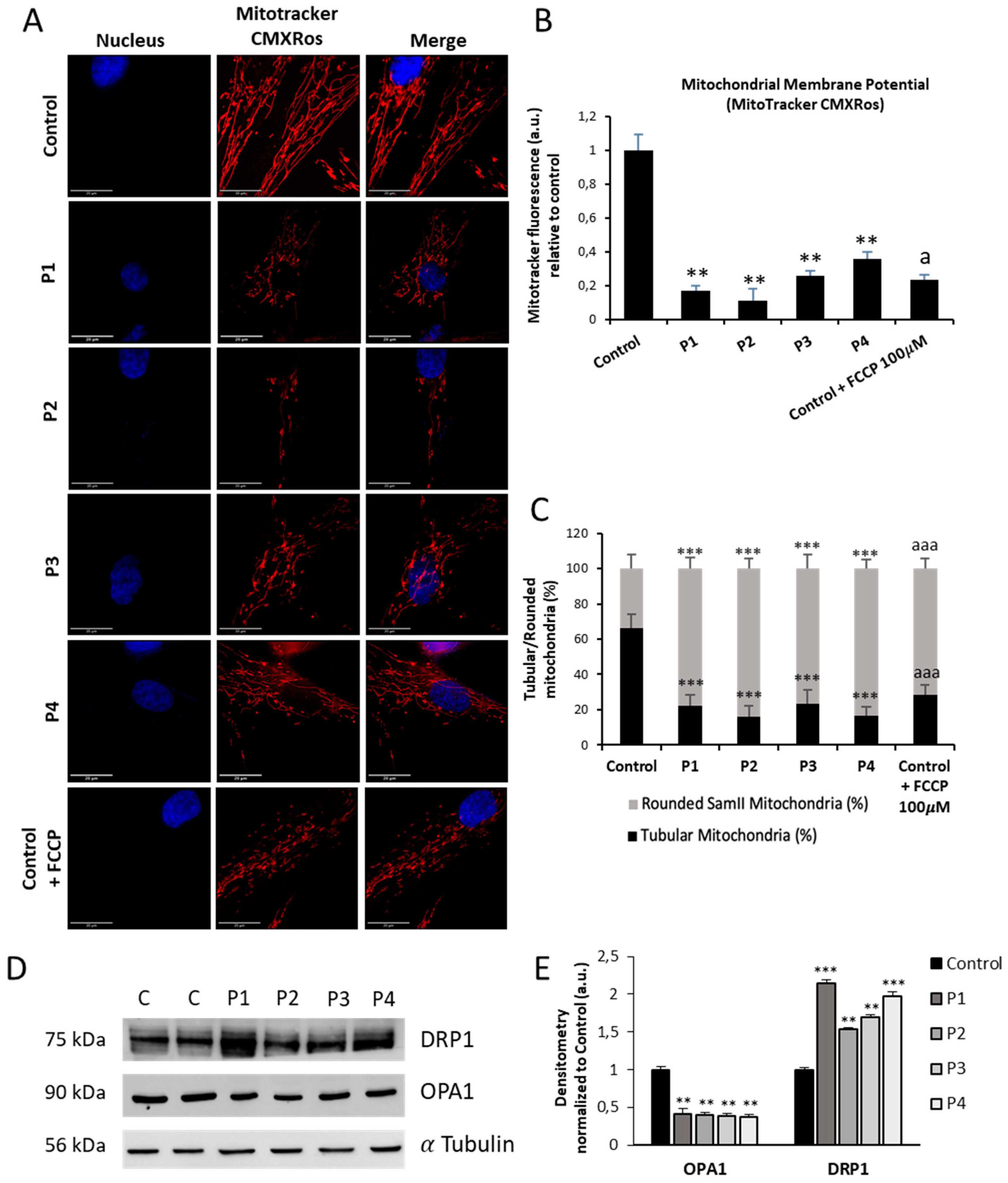

Mitochondrial polarization and network in control and NM cells. (A) Representative images of control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) stained with MitoTrackerTM Red CMXRos and visualized under widefield fluorescence microscope. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. As a positive control of membrane depolarization, we used 100 µM CCCP for 4 h in control cells. Images were taken using the 100x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Fluorescence quantification of MitoTracker signal. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (at least 100 cells for each condition and experiment were analysed). (C) Quantification of tubular and rounded percentage of mitochondria in control and NM fibroblasts. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (at least 100 cells for each condition and experiment were analysed). (D) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against DRP1, OPA1 and α Tubulin, which was used as a loading control. (E) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For controls cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM cells and controls; ap<0.05, aap<0.01, aaap<0.001 between the presence and the absence of CCCP. A. U.: arbitrary units.

Figure 7.

Mitochondrial polarization and network in control and NM cells. (A) Representative images of control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) stained with MitoTrackerTM Red CMXRos and visualized under widefield fluorescence microscope. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. As a positive control of membrane depolarization, we used 100 µM CCCP for 4 h in control cells. Images were taken using the 100x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Fluorescence quantification of MitoTracker signal. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (at least 100 cells for each condition and experiment were analysed). (C) Quantification of tubular and rounded percentage of mitochondria in control and NM fibroblasts. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (at least 100 cells for each condition and experiment were analysed). (D) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against DRP1, OPA1 and α Tubulin, which was used as a loading control. (E) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For controls cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM cells and controls; ap<0.05, aap<0.01, aaap<0.001 between the presence and the absence of CCCP. A. U.: arbitrary units.

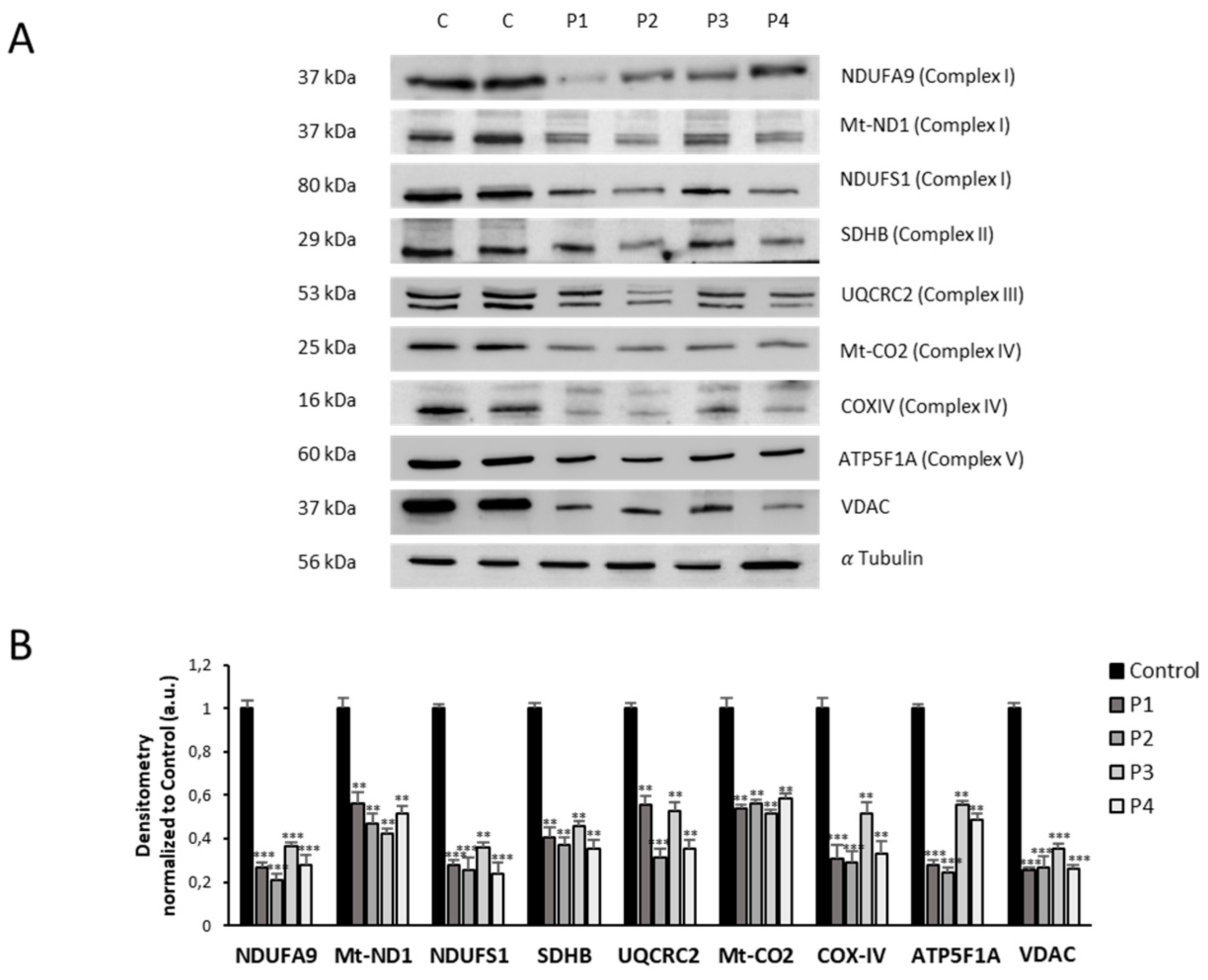

Figure 8.

Mitochondrial protein expression levels in control and NM cells. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against NDUFA9 (Complex I), NDUFS4 (Complex I), mtND1(Complex I), SDHB (Complex II), UQCRC2 (Complex III), mtCO2 (Complex IV), COX4 (Complex IV), ATP5A (Complex V) and VDAC1. α Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For controls cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. A.U., arbitrary units.

Figure 8.

Mitochondrial protein expression levels in control and NM cells. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against NDUFA9 (Complex I), NDUFS4 (Complex I), mtND1(Complex I), SDHB (Complex II), UQCRC2 (Complex III), mtCO2 (Complex IV), COX4 (Complex IV), ATP5A (Complex V) and VDAC1. α Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For controls cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. A.U., arbitrary units.

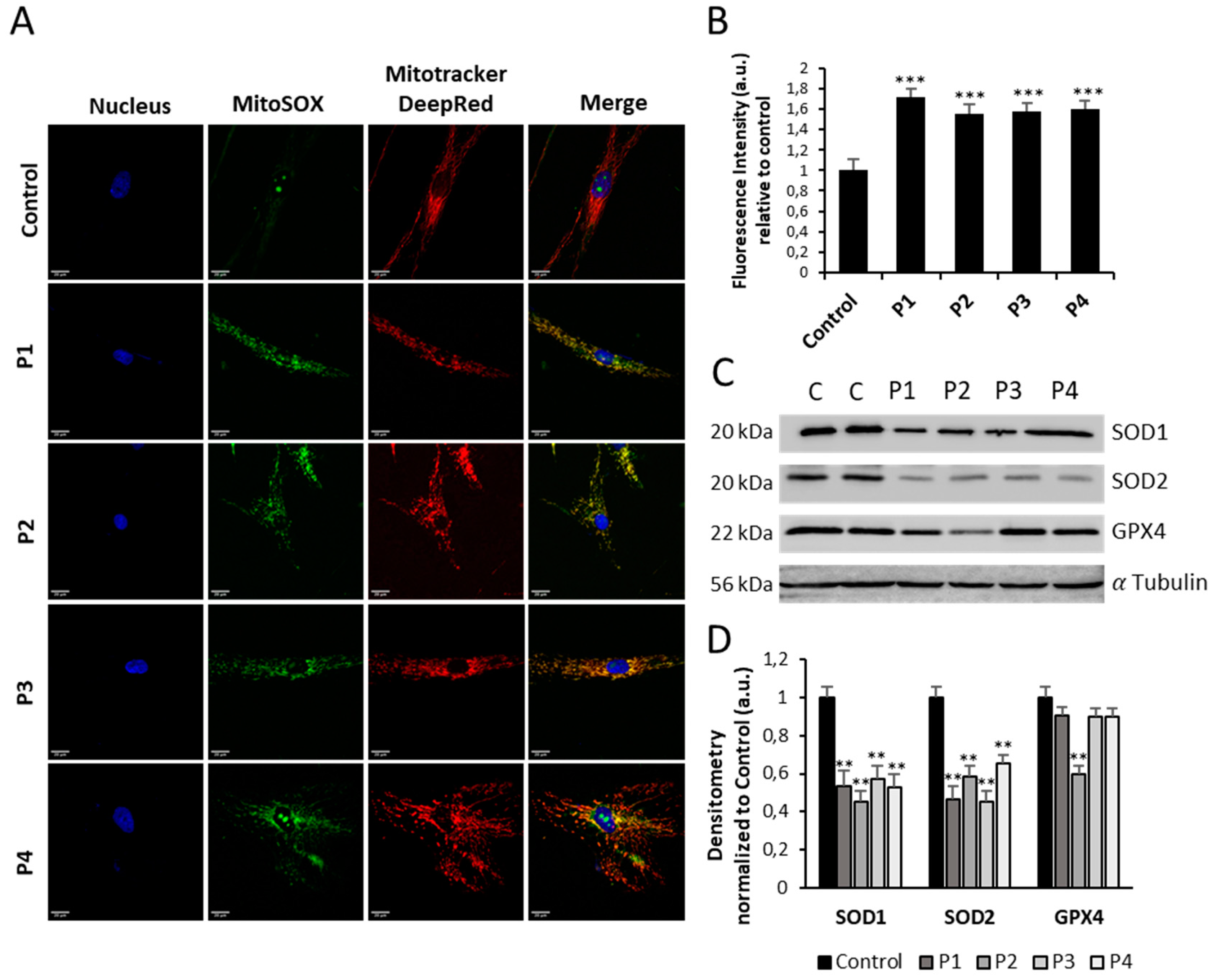

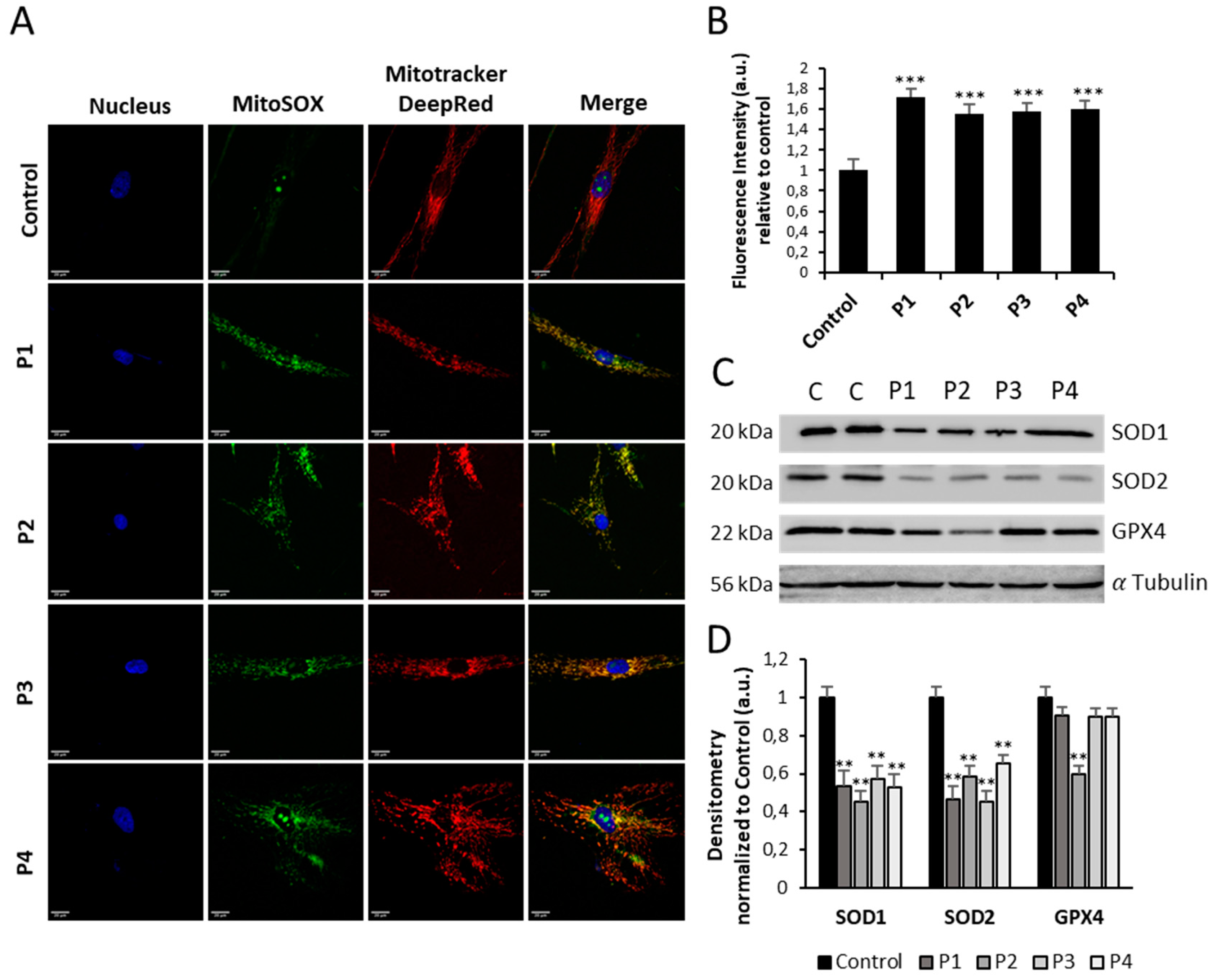

Figure 9.

Expression levels of ROS and antioxidant enzymes in NM cells. (A) Representative images of control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) stained with MitoSOX™ Red and MitoTrackerTM DeepRed. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. Images were taken under widefield fluorescence microscope using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Fluorescence quantification of MitoSOX™ Red signal. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (at least 100 cells for each condition and experiment were analysed). (C) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from Controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against SOD1, SOD2 and GPX4. α Tubulin was used as a loading control. (D) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For control cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. A.U., arbitrary units.

Figure 9.

Expression levels of ROS and antioxidant enzymes in NM cells. (A) Representative images of control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) stained with MitoSOX™ Red and MitoTrackerTM DeepRed. Nuclei were revealed by DAPI staining. Images were taken under widefield fluorescence microscope using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Fluorescence quantification of MitoSOX™ Red signal. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (at least 100 cells for each condition and experiment were analysed). (C) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from Controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1, P2, P3 and P4. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against SOD1, SOD2 and GPX4. α Tubulin was used as a loading control. (D) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For control cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells. A.U., arbitrary units.

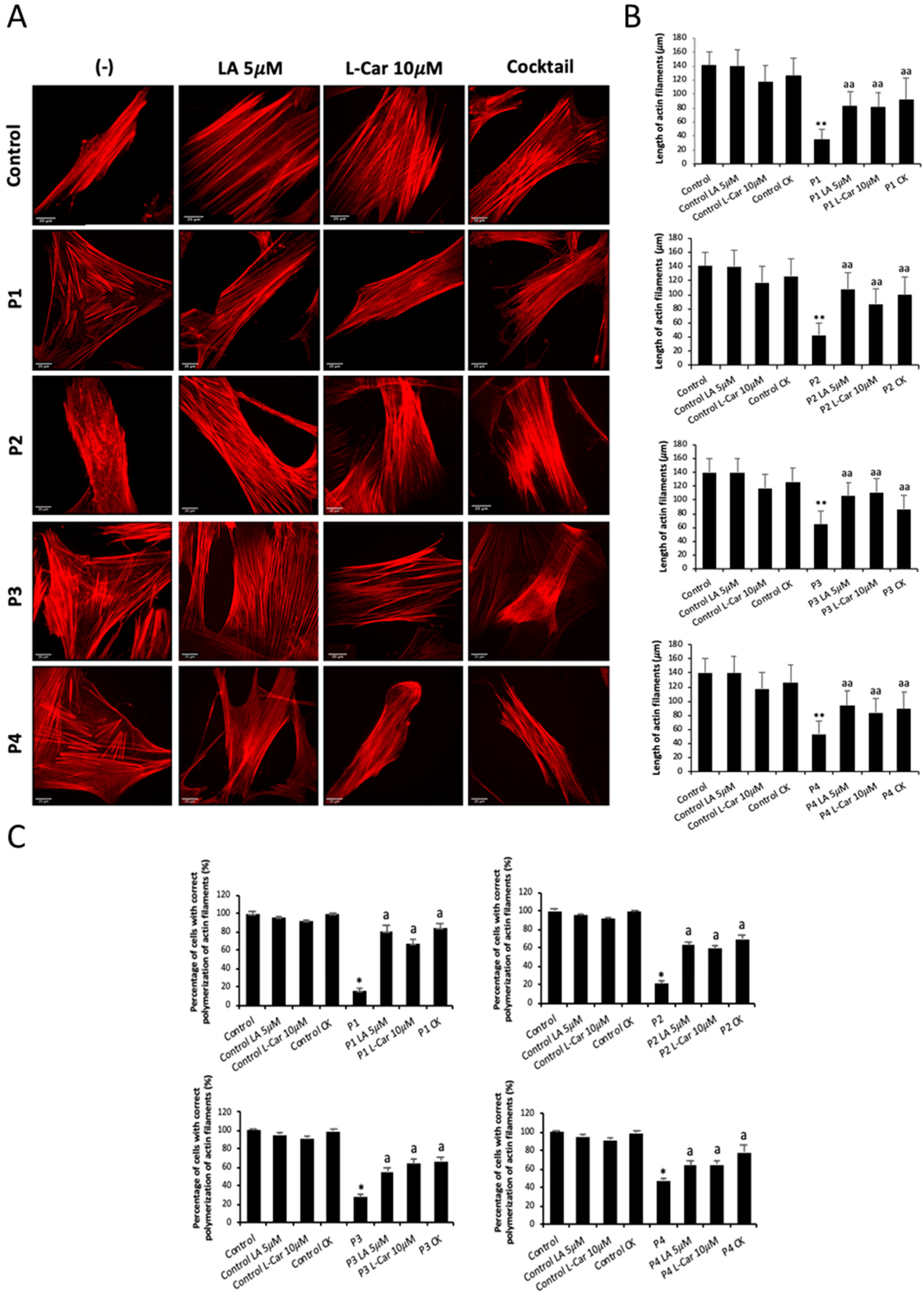

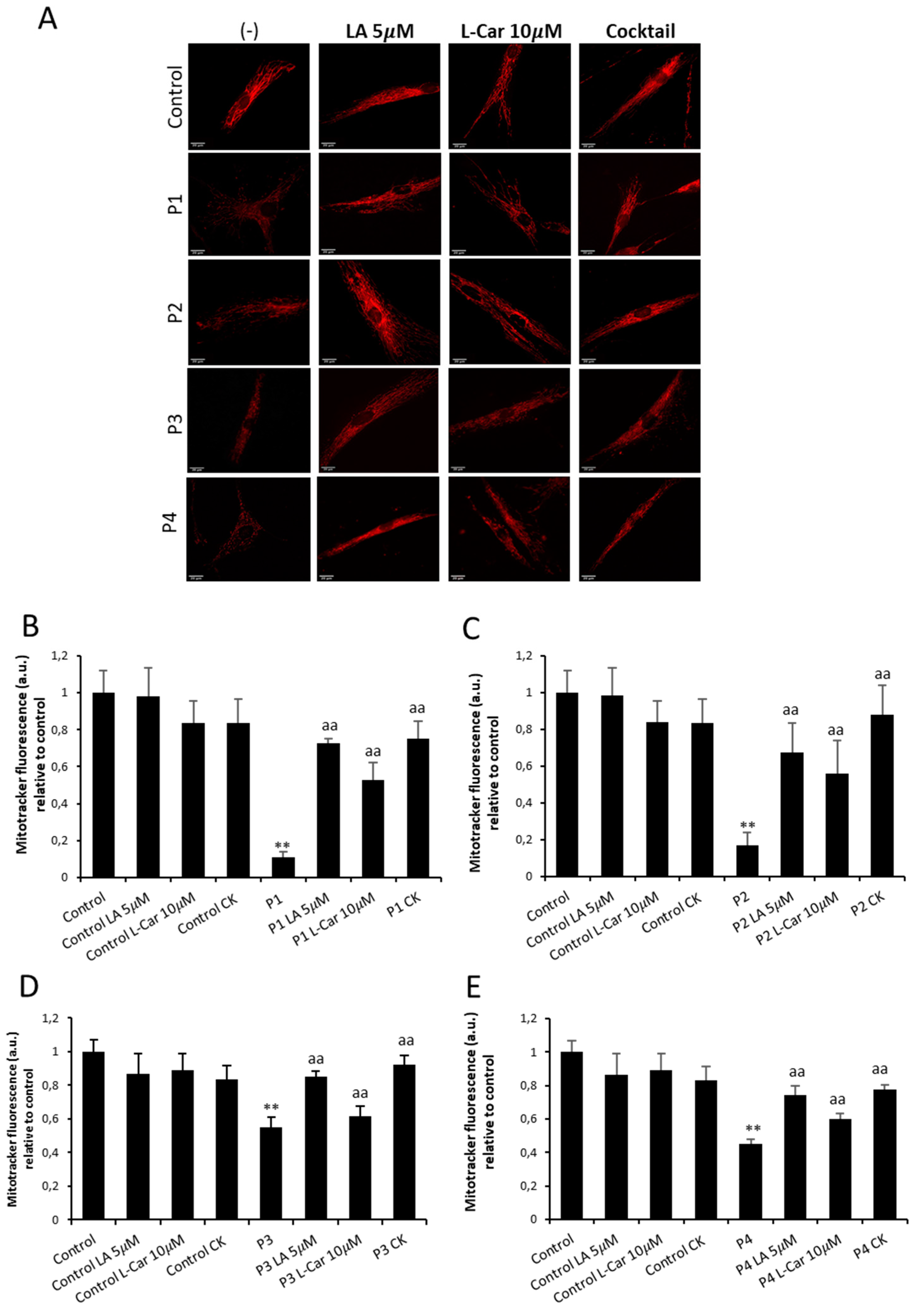

Figure 10.

Effect of LA and LCAR on actin polymerization in control and NM cells. Control and NM fibroblasts were treated with 5 mM LA and 10 mM LCAR individually or in combination (Cocktail) for 7 days. (A) Representative images of treated and untreated (-) Control and NM fibroblasts, P1 and P2 (mutation in ACTA1) and P3 and P4 (mutation in NEB) stained with Rhodamine-Phalloidin. Images were taken using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Measurements of the length of actin filaments (𝜇m). The length of the actin filaments was measured in triplicate with the ImageJ software in 30 images. (C) Percentages of cells with correct actin polymerization. Three counts of 100 cells per sample were performed. **p<0.01 between NM and controls cells; ap<0.05, aap<0.01 between untreated (-) and treated NM cells.

Figure 10.

Effect of LA and LCAR on actin polymerization in control and NM cells. Control and NM fibroblasts were treated with 5 mM LA and 10 mM LCAR individually or in combination (Cocktail) for 7 days. (A) Representative images of treated and untreated (-) Control and NM fibroblasts, P1 and P2 (mutation in ACTA1) and P3 and P4 (mutation in NEB) stained with Rhodamine-Phalloidin. Images were taken using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Measurements of the length of actin filaments (𝜇m). The length of the actin filaments was measured in triplicate with the ImageJ software in 30 images. (C) Percentages of cells with correct actin polymerization. Three counts of 100 cells per sample were performed. **p<0.01 between NM and controls cells; ap<0.05, aap<0.01 between untreated (-) and treated NM cells.

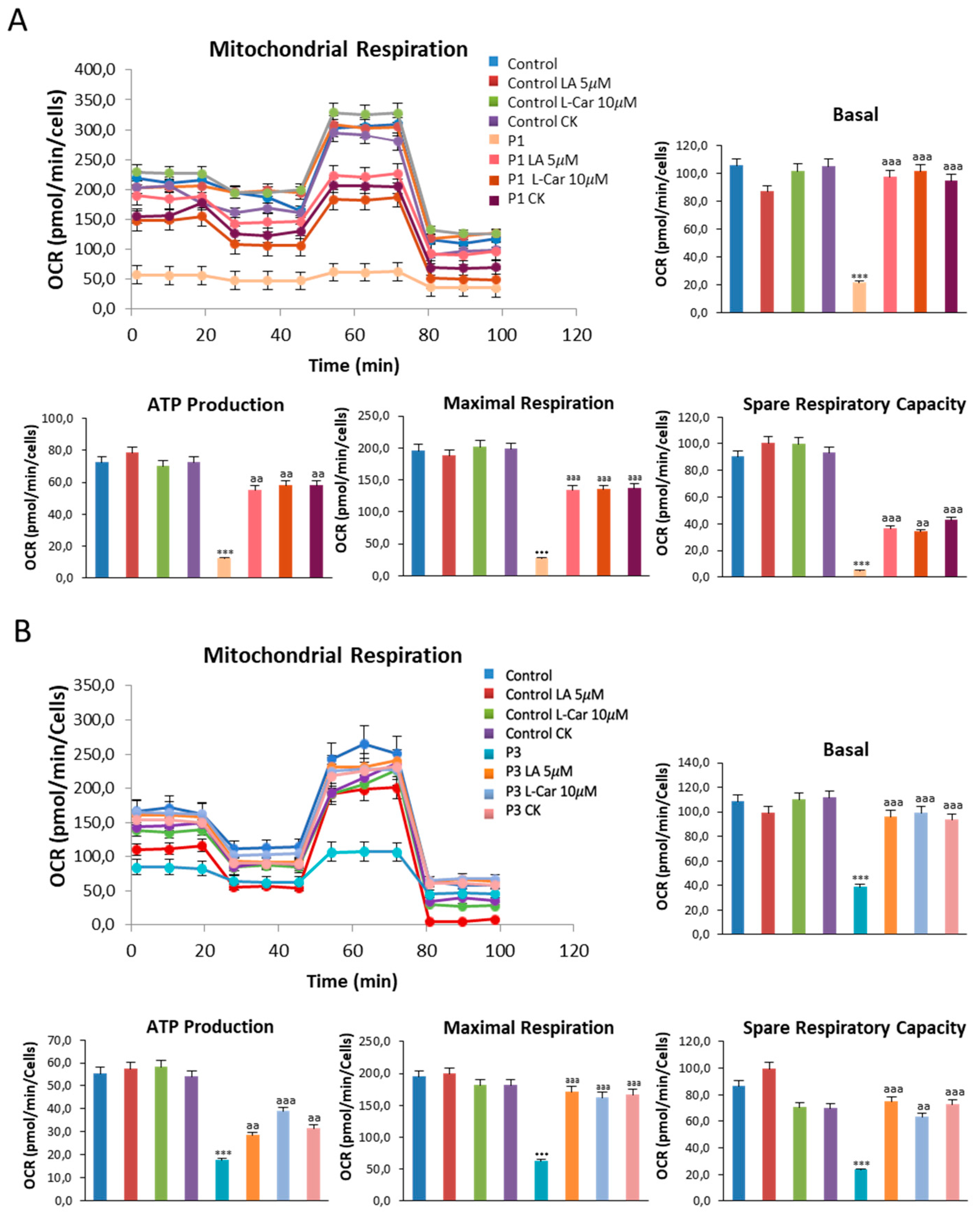

Figure 11.

Effect of LA and LCAR on bioenergetics of control and NM fibroblasts. Control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1 and P3) were treated (+) with 5 mM LA and 10 mM LCAR individually or in combination for 7 days. Basal and maximal respiration, Mitochondrial ATP production and Spare Respiratory capacity were determined in controls (C1 and C2) and NM fibroblasts (P1 and P3) by using the Seahorse analyzer as described in Material and Methods. (A) Corresponding with P1; (B) Corresponding with P3. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells; aap<0.01, aaap<0.001 between untreated (-) and treated NM cells.

Figure 11.

Effect of LA and LCAR on bioenergetics of control and NM fibroblasts. Control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1 and P3) were treated (+) with 5 mM LA and 10 mM LCAR individually or in combination for 7 days. Basal and maximal respiration, Mitochondrial ATP production and Spare Respiratory capacity were determined in controls (C1 and C2) and NM fibroblasts (P1 and P3) by using the Seahorse analyzer as described in Material and Methods. (A) Corresponding with P1; (B) Corresponding with P3. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. ***p<0.001 between NM and controls cells; aap<0.01, aaap<0.001 between untreated (-) and treated NM cells.

Figure 12.

Effect of LA and LCAR on mitochondrial polarization and network in control and NM cells. Control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were treated (+) with 5 mM LA and 10 mM LCAR individually or in combination (Cocktail) for 7 days. (A) Representative images of untreated and treated control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1 and P2) stained with MitoTrackerTM Red CMXRos, an in vivo mitochondrial membrane potential-dependent probe. Images were taken using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Fluorescence quantification of MitoTracker signal. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (at least 100 cells for each condition and experiment were analysed). **p<0.01 between NM and controls cells; aap<0.01 between untreated (-) and treated NM cells. A. U.: arbitrary units.

Figure 12.

Effect of LA and LCAR on mitochondrial polarization and network in control and NM cells. Control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were treated (+) with 5 mM LA and 10 mM LCAR individually or in combination (Cocktail) for 7 days. (A) Representative images of untreated and treated control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1 and P2) stained with MitoTrackerTM Red CMXRos, an in vivo mitochondrial membrane potential-dependent probe. Images were taken using the 40x lens and processed by the ImageJ software. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Fluorescence quantification of MitoTracker signal. Data represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (at least 100 cells for each condition and experiment were analysed). **p<0.01 between NM and controls cells; aap<0.01 between untreated (-) and treated NM cells. A. U.: arbitrary units.

Figure 13.

Effect of LA and LCAR on mitochondrial protein expression levels in control and NM cells. Control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were treated with 5 µM LA and 10 µM LCAR individually or in combination (Cocktail, CK) for 7 days. (

A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1 and P2. (

B) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P3 and P4 Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against NDUFA9, SDHB, UQCR2, Mt-CO2, ATP5F1A, VDAC, OPA1 and DRP1. α Tubulin was used as a loading control. (Densitometry of the Western blotting

Supplementary Figures S8–S11).

Figure 13.

Effect of LA and LCAR on mitochondrial protein expression levels in control and NM cells. Control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were treated with 5 µM LA and 10 µM LCAR individually or in combination (Cocktail, CK) for 7 days. (

A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1 and P2. (

B) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P3 and P4 Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against NDUFA9, SDHB, UQCR2, Mt-CO2, ATP5F1A, VDAC, OPA1 and DRP1. α Tubulin was used as a loading control. (Densitometry of the Western blotting

Supplementary Figures S8–S11).

Figure 14.

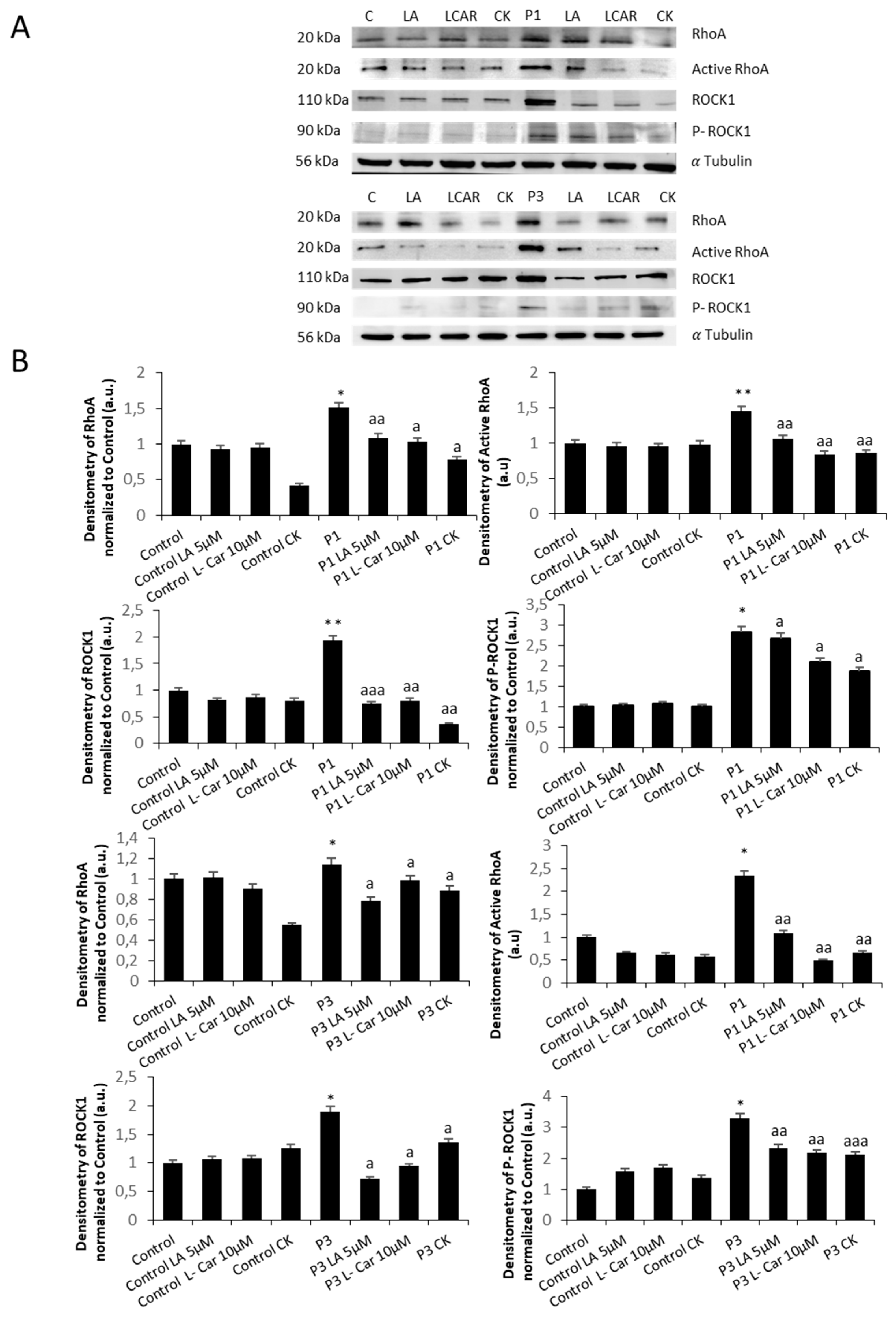

Effect of LA and LCAR on RhoA/ROCK pathway activation in Control and NM cells. Control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were treated with 5 µM LA and 10 µM LCAR individually or in combination for 7 days. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1 and P2. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against RhoA, Active RhoA purified by Active Rho Detection Kit as described in Material and Methods, ROCK1, phospho ROCK1 and α Tubulin, which was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For controls cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, between treated and untreated (-) cells. ap<0.05 aap<0.01 aaap<0.001 between untreated (-) and treated NM cells. A. U.: arbitrary units.

Figure 14.

Effect of LA and LCAR on RhoA/ROCK pathway activation in Control and NM cells. Control (C1) and NM fibroblasts (P1, P2, P3 and P4) were treated with 5 µM LA and 10 µM LCAR individually or in combination for 7 days. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of cellular extracts from controls (C1 and C2) and NM patient cell lines P1 and P2. Protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on a SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunostained with antibodies against RhoA, Active RhoA purified by Active Rho Detection Kit as described in Material and Methods, ROCK1, phospho ROCK1 and α Tubulin, which was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of the Western blotting. For controls cells (C1 and C2), data are the mean±SD of the two control cell lines. Data represent the mean±SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, between treated and untreated (-) cells. ap<0.05 aap<0.01 aaap<0.001 between untreated (-) and treated NM cells. A. U.: arbitrary units.