Submitted:

20 June 2024

Posted:

21 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Changes to the Proteome in MDX Compared to Wild Type

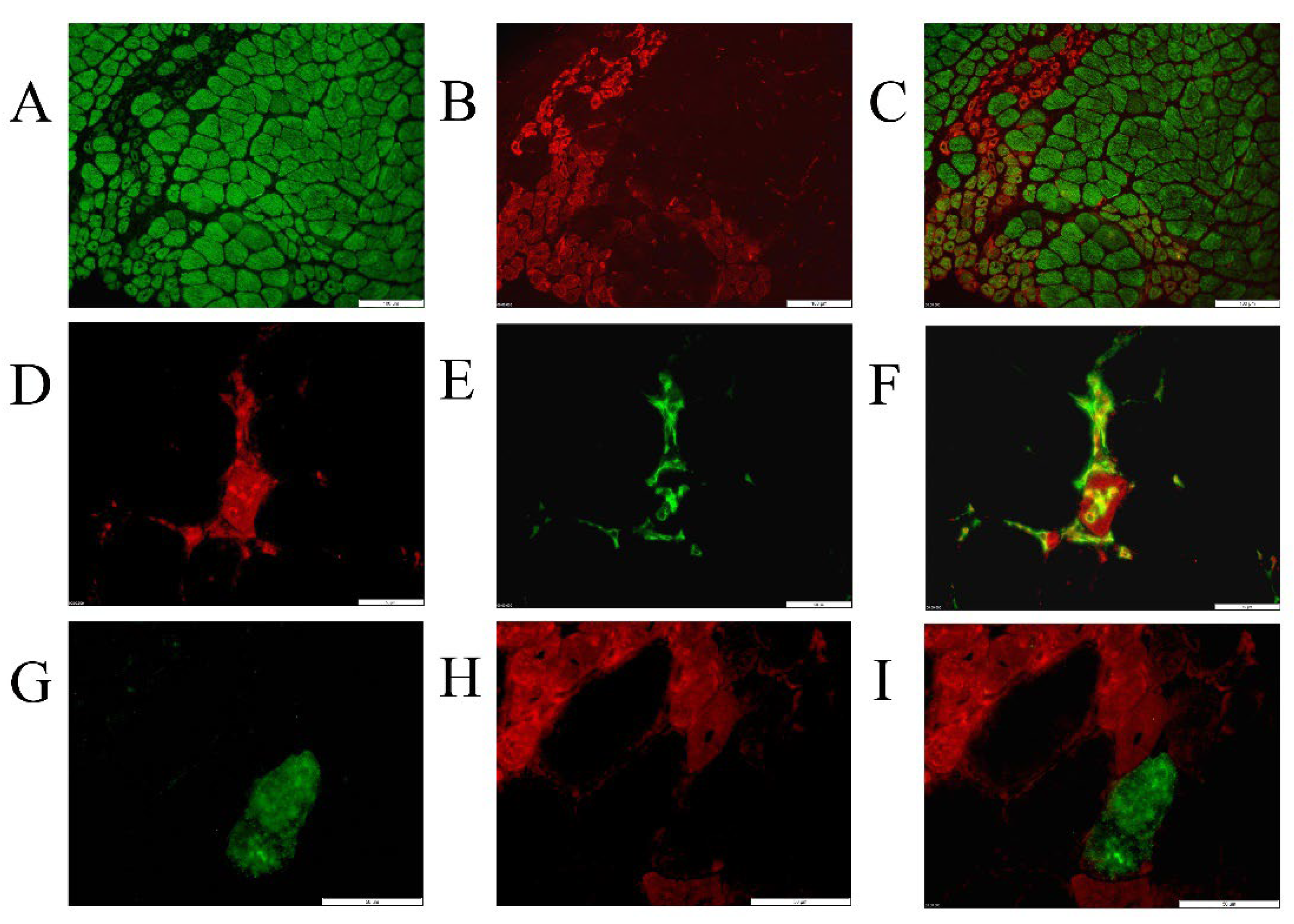

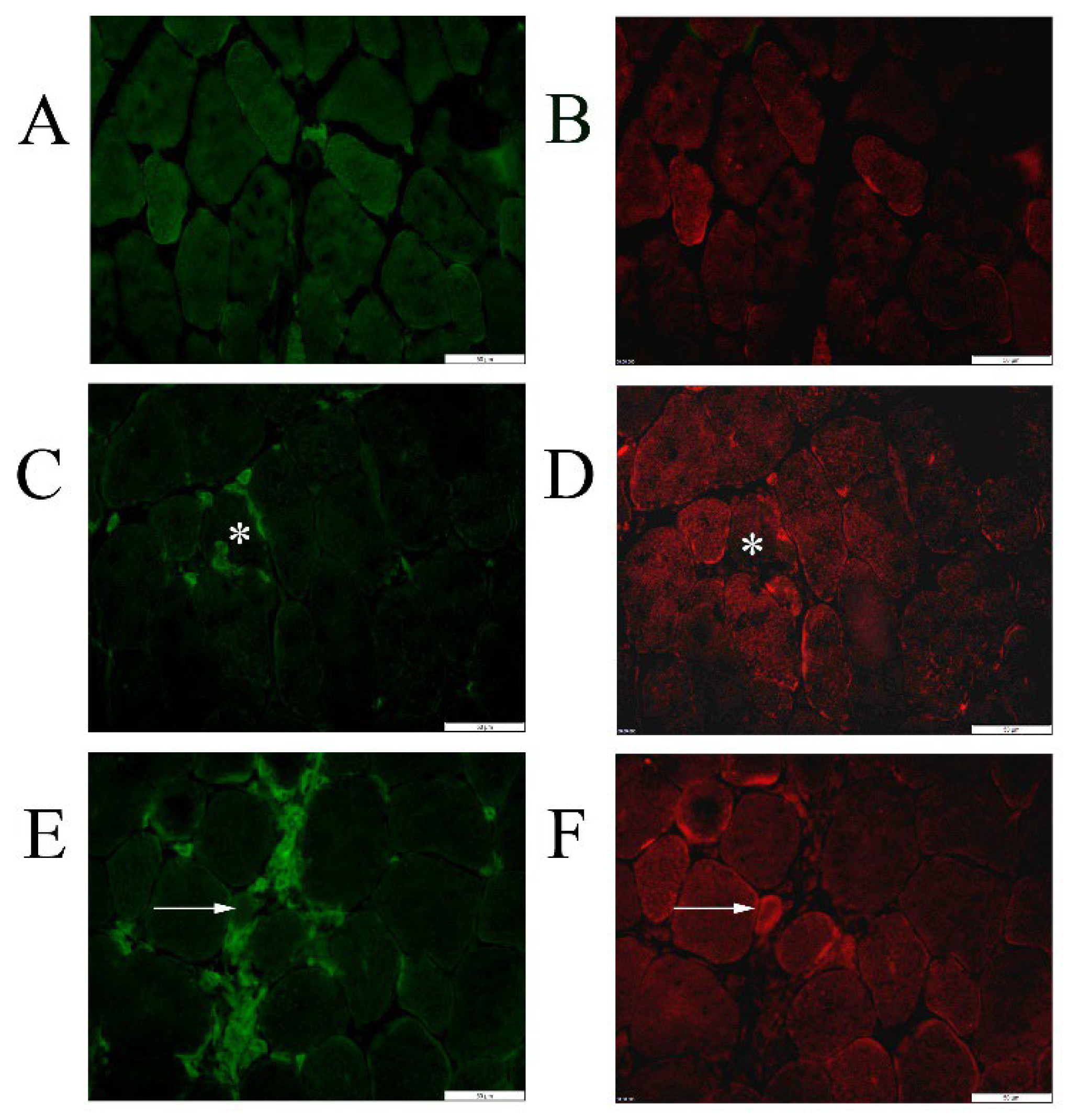

2.2. Tissue Expression Patterns of Autophagy-Related Proteins in MDX Compared to Wild Type

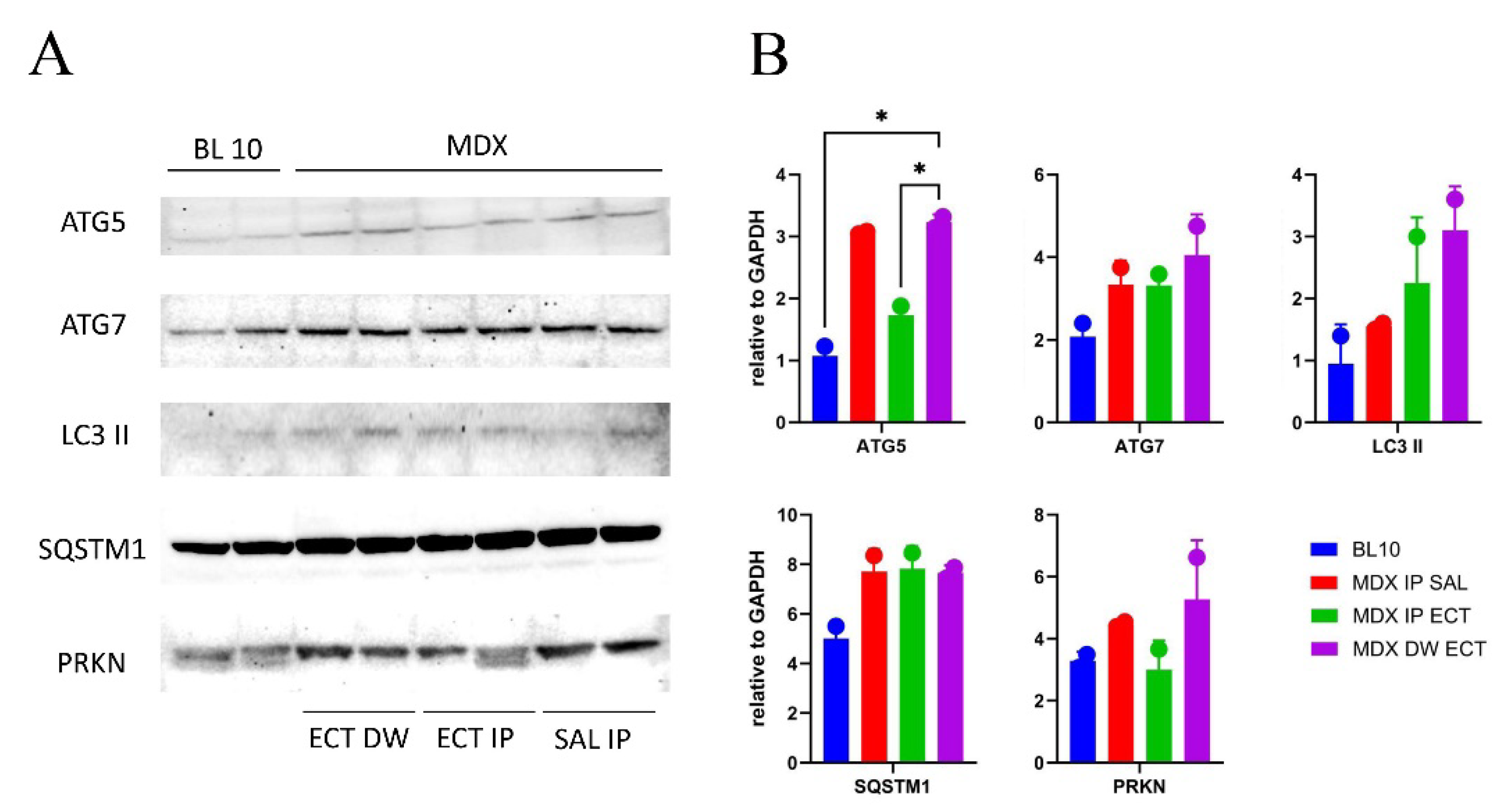

2.3. Changes to the Skeletal Muscle Proteome of Ectoine-Treated MDX

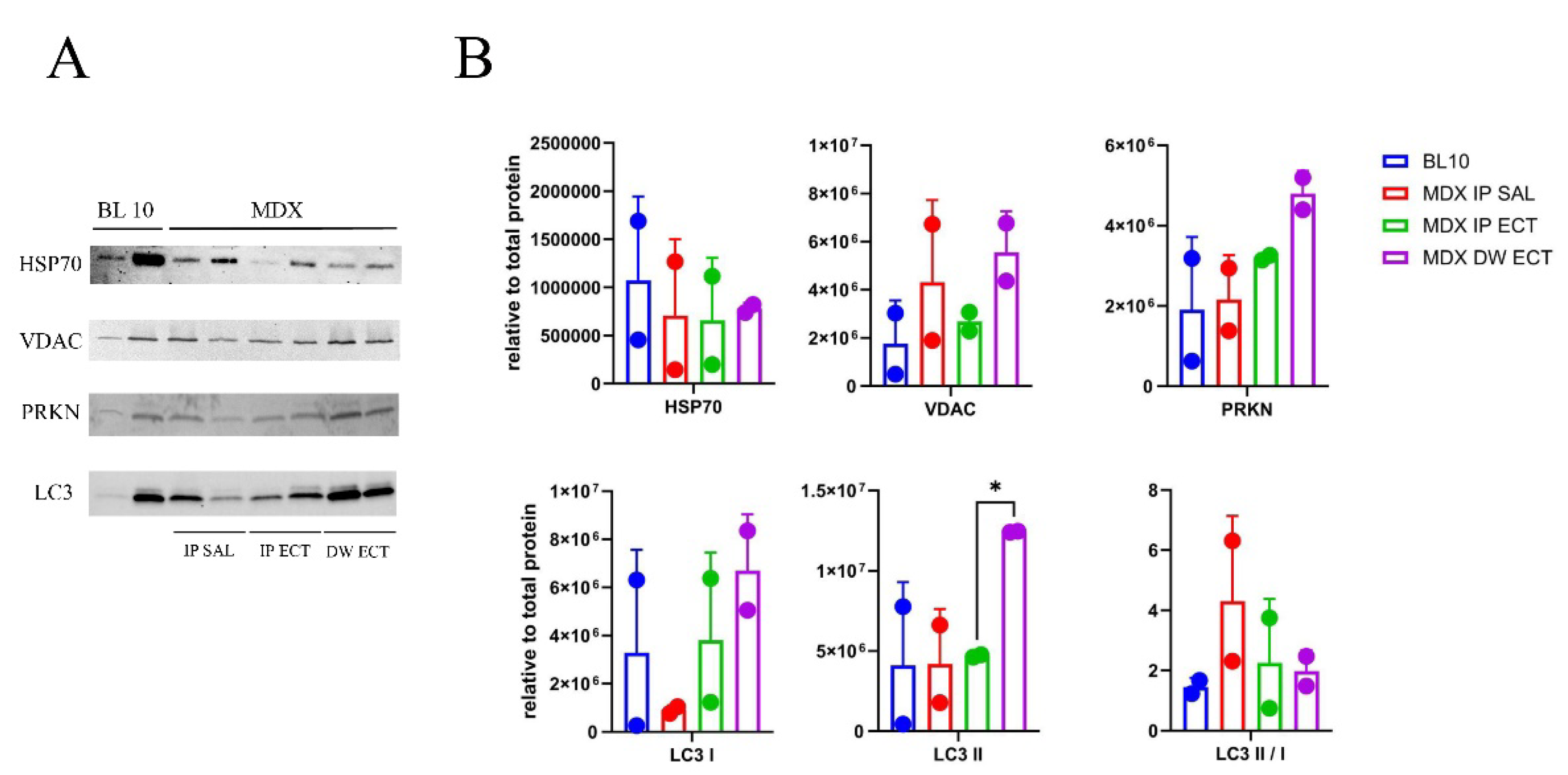

2.4. Changed Tissue Expression Patterns of Autophagy-Related Proteins in Ectoine-Treated MDX

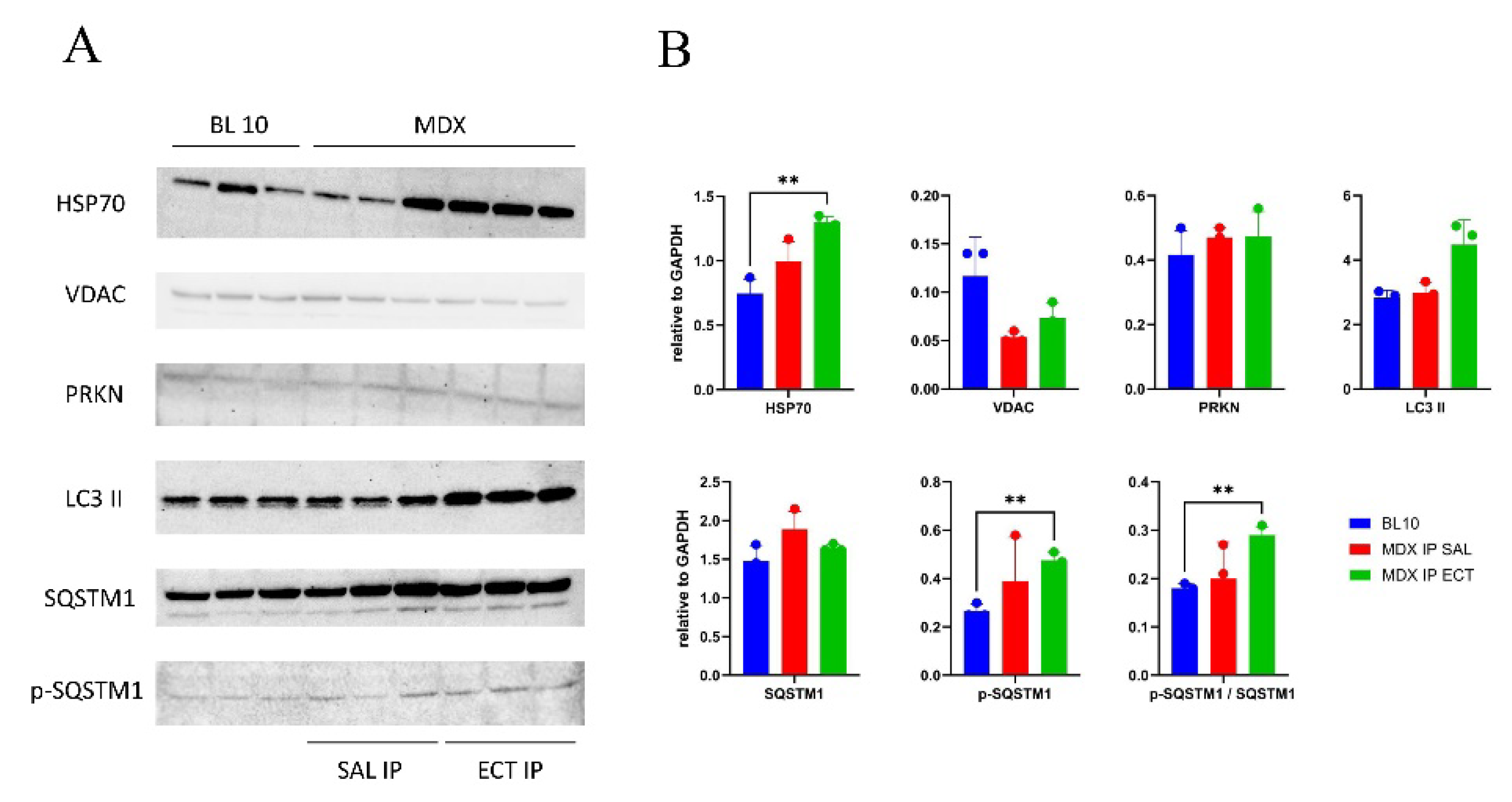

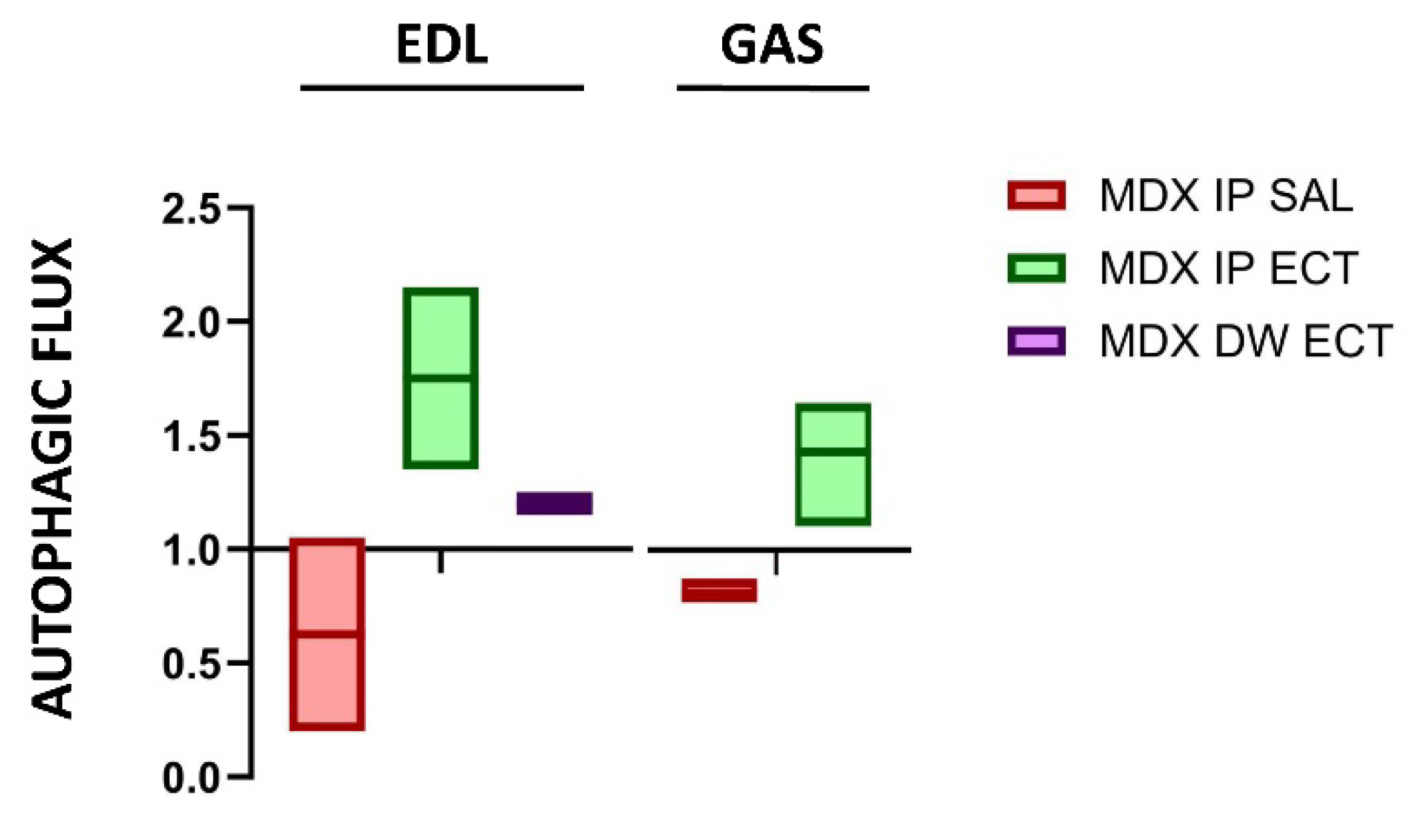

2.5. Changes to the Mitochondrial Proteome in Ectoine-Treated MDX

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Care, Treatment and Muscle Sampling

4.2. Protein Sample Preparation

4.3. Western Blotting

4.4. Statistical Analysis

4.5. Immunofluorescent Staining

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Ginjaar, I.B.; Bushby, K. The importance of genetic diagnosis for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Med Gen 2016, 53, 145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.G.; Wahl, R.A. Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy in adolescents: current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 2018, 9, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suthar, R.; Sankhyan, N. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Practice Update. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics 2018, 85, 276–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin, B. Dystrophin complex functions as a scaffold for signalling proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2014, 1838, 635–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soblechero-Martín, P.; Albiasu-Arteta, E.; Anton-Martinez, A.; de la Puente-Ovejero, L.; Garcia-Jimenez, I.; González-Iglesias, G.; Larrañaga-Aiestaran, I.; López-Martínez, A.; Poyatos-García, J.; Ruiz-Del-Yerro, E.; Gonzalez, F.; Arechavala-Gomeza, V. Duchenne muscular dystrophy cell culture models created by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and their application in drug screening. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 18188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grounds, M.D.; Terrill, JR.; Al-Mshhdani, B.A.; Duong, M.N.; Radley-Crabb, H.G.; Arthur, P.G. Biomarkers for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: myonecrosis, inflammation and oxidative stress. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2020, 13, dmm043638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Li, H.; He, J.; Liang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W. TRIM72 Alleviates Muscle Inflammation in mdx Mice via Promoting Mitophagy-Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Inactivation. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2023, 2023, 8408574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Putten, M.; Putker, K.; Overzier, M.; Adamzek, W.A.; Pasteuning-Vuhman, S.; Plomp, J.J.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Natural disease history of the D2-mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. FASEB J 2019, 33, 8110–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucha, O.; Kaziród, K.; Podkalicka, P.; Rusin, K.; Dulak, J.; Łoboda, A. Dysregulated Autophagy and Mitophagy in a Mouse Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Remain Unchanged Following Heme Oxygenase-1 Knockout. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frudd, K.; Burgoyne, T.; Burgoyne, J.R. Oxidation of Atg3 and Atg7 mediates inhibition of autophagy. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.J.; Suomi, F.; Oláhová, M.; McWilliams, T.G.; Taylor, R.W. Emerging roles of ATG7 in human health and disease. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2021, 13, e14824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammoh, N. The multifaceted functions of ATG16L1 in autophagy and related processes. Journal of Cell Science 2020, 133, jcs249227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWilliams, T.G.; Barini, E.; Pohjolan-Pirhonen, R.; Brooks, S.P.; Singh, F.; Burel, S.; Balk, K.; Kumar, A.; Montava-Garriga, L.; Prescott, A.R.; Hassoun, S.M.; Mouton-Liger, F.; Ball, G.; Hills, R.; Knebel, A.; Ulusoy, A.; Di Monte, D.A.; Tamjar, J.; Antico, O.; Fears, K.; Smith, L.; Brambilla, R.; Palin, E.; Valori, M.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Tienari, P.; Corti, O.; Dunnett, S.B.; Ganley, I.G.; Suomalainen, A.; Muqit, M.M.K. Phosphorylation of Parkin at serine 65 is essential for its activation in vivo. Open Biology 2018, 8, 180108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebori, R.; Kuno, A.; Hosoda, R.; Hayashi, T.; Horio, Y. Resveratrol Decreases Oxidative Stress by Restoring Mitophagy and Improves the Pathophysiology of Dystrophin-Deficient mdx Mice. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2018, 2018, 9179270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGreevy, J.W.; Hakim, C.H.; McIntosh, M.A.; Duan, D. Animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from basic mechanisms to gene therapy. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2015, 8, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, R.; Possekel, S.; Dubach-Powell, J.; Meier, T.; Ruegg, M.A. Mammalian animal models for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscular Disorders 2009, 19, 241–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.J. Tracking progress: an update on animal models for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2018, 11, dmm035774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grounds, M.D.; Radley, H.G.; Lynch, G.S.; Nagaraju, K.; De Luca, A. Towards developing standard operating procedures for pre-clinical testing in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurobiology of Disease 2008, 31, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, E.; Vellecco, V.; Iannotti, F.A.; Paris, D.; Manzo, O.L.; Smimmo, M.; Mitilini, N.; Boscaino, A.; de Dominicis, G.; Bucci, M.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Cirino, G. Duchenne's muscular dystrophy involves a defective transsulfuration pathway activity. Redox Biology 2021, 45, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markati, T.; Oskoui, M.; Farrar, M.A.; Duong, T.; Goemans, N.; Servais, L. Emerging therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The Lancet Neurology 2022, 21, 814–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.L.; Alexander, M.S. The Interplay of Mitophagy and Inflammation in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Life (Basel) 2021, 11, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbelet, S.; De Paepe, B.; De Bleecker, J.L. Abnormal NFAT5 Physiology in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Fibroblasts as a Putative Explanation for the Permanent Fibrosis Formation in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merckx, C.; De Paepe, B. The Role of Taurine in Skeletal Muscle Functioning and Its Potential as a Supportive Treatment for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Metabolites 2022, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merckx, C.; Zschüntzsch, J.; Meyer, S.; Raedt, R.; Verschuere, H.; Schmidt, J.; De Paepe, B.; De Bleecker, J.L. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Ectoine in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Comparison with Taurine, a Supplement with Known Beneficial Effects in the mdx Mouse. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, L.; Hermann, L.; Stöveken, N.; Richter, A.A.; Höppner, A.; Smits, S.H.J.; Heider, J.; Bremer, E. Role of the Extremolytes Ectoine and Hydroxyectoine as Stress Protectants and Nutrients: Genetics, Phylogenomics, Biochemistry, and Structural Analysis. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bownik, A.; Stępniewska, Z. Ectoine as a promising protective agent in humans and animals. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 2016, 67, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbiera, A.; Sorrentino, S.; Lepore, E.; Carfì, A.; Sica, G.; Dobrowolny, G.; Scicchitano, B.M. Taurine Attenuates Catabolic Processes Related to the Onset of Sarcopenia. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 8865–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouschop, K.M.; van den Beucken, T.; Dubois, L.; Niessen, H.; Bussink, J.; Savelkouls. K.; Keulers, T.; Mujcic, H.; Landuyt, W.; Voncken. J.W.; Lambin, P.; van der Kogel, A.J.; Koritzinsky, M.; Wouters, B.G. The unfolded protein response protects human tumor cells during hypoxia through regulation of the autophagy genes MAP1LC3B and ATG5. The Journal of clinical investigation 2010, 120, 127–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyo, J.O.; Yoo, S.M.; Ahn, H.H.; Nah, J.; Hong, S.H.; Kam, T.I.; Jung, S.; Jung, Y.K. Overexpression of Atg5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan. Nature Communication 2013, 4, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; Andres, A.M.; Taylor, D.J.R.; Weston, T.; Hiraumi, Y.; Stotland, A.; Kim, B.J.; Huang, C.; Doran, K.S.; Gottlieb, R.A. Mitophagy is required for mitochondrial biogenesis and myogenic differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts. Autophagy 2016, 12, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, A.; Omairi, S.; Mitchell, R.; Vaughan, D.; Matsakas, A.; Vaiyapuri, S.; Ricketts, T.; Rubinsztein, D.C.; Patel, K. Attenuation of autophagy impacts on muscle fibre development, starvation induced stress and fibre regeneration following acute injury. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 9062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaoui, D.; Subtil, A. ATG16L1 functions in cell homeostasis beyond autophagy. FEBS J 2022, 289, 1779–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Outeiriño, L.; Hernandez-Torres, F.; Ramirez de Acuña, F.; Rastrojo, A.; Creus, C.; Carvajal, A.; Salmeron, L.; Montolio, M.; Soblechero-Martin, P.; Arechavala-Gomeza, V.; Franco, D.; Aranega, A.E. miR-106b is a novel target to promote muscle regeneration and restore satellite stem cell function in injured Duchenne dystrophic muscle. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2022, 29, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Velasco, E.; Vallejo, D. , Esteban. FJ.; Doherty, C.; Hernández-Torres, F.; Franco, D.; Aránega, A.E. A Pitx2-MicroRNA Pathway Modulates Cell Proliferation in Myoblasts and Skeletal-Muscle Satellite Cells and Promotes Their Commitment to a Myogenic Cell Fate. Molecular Cell Biology 2015, 35, 2892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aránega, A.E.; Lozano-Velasco, E.; Rodriguez-Outeiriño, L.; Ramírez de Acuña, F.; Franco, D.; Hernández-Torres, F. MiRNAs and Muscle Regeneration: Therapeutic Targets in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Z.; Wu, F.; Chuang, A.Y.; Kwon, J.H. miR-106b fine tunes ATG16L1 expression and autophagic activity in intestinal epithelial HCT116 cells. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2013, 19, 2295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosemans, G.; Merckx, C.; De Bleecker, J.L.; De Paepe, B. Inducible Heat Shock Protein 70 Levels in Patients and the mdx Mouse Affirm Regulation during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration in Muscular Dystrophy. Frontiers in Bioscience-Scholar 2022, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.R.; Valpuesta, J.M. Hsp70 chaperone: a master player in protein homeostasis. F1000Res 2018, 7, F1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, J.I.; Barnoud, T.; Zhang, G.; Tian, T.; Wei, Z.; Herlyn, M.; Murphy, M.E.; George, D.L. Inhibition of stress-inducible HSP70 impairs mitochondrial proteostasis and function. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 45656–45669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna,S. ; Spaulding, H.R.; Quindry, T.S.; Hudson, M.B.; Quindry, J.C.; Selsby, J.T. Indices of Defective Autophagy in Whole Muscle and Lysosome Enriched Fractions From Aged D2-mdx Mice. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 691245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, H.R.; Ballmann, C.; Quindry, J.C.; Hudson, M.B.; Selsby, J.T. Autophagy in the heart is enhanced and independent of disease progression in mus musculus dystrophinopathy models. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis 2019, 8, 2048004019879581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, A.; Hosoda, R.; Sebori, R.; Hayashi, T.; Sakuragi, H.; Tanabe, M.; Horio, Y. Resveratrol Ameliorates Mitophagy Disturbance and Improves Cardiac Pathophysiology of Dystrophin-deficient mdx Mice. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 15555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, R.; Hosoda, R.; Tatekoshi, Y.; Iwahara, N.; Saga, Y.; Kuno, A. Transcriptional dysregulation of autophagy in the muscle of a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Badr, M.A.; Kyrychenko, V.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Shirokova, N. Deficit in PINK1/PARKIN-mediated mitochondrial autophagy at late stages of dystrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 2018, 114, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Palma, C.; Morisi, F.; Cheli, S.; Pambianco, S.; Cappello, V.; Vezzoli, M.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Moggio, M.; Ripolone, M.; Francolini, M.; Sandri, M.; Clementi, E. Autophagy as a new therapeutic target in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Death Discovery 2012, 3, e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Lei, S.; She, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, R. Running improves muscle mass by activating autophagic flux and inhibiting ubiquitination degradation in mdx mice. Gene 2024, 899, 148136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, O.; Myszka, M.; Podkalicka, P.; Świderska, B.; Malinowska, A.; Dulak, J.; Łoboda, A. Proteome Profiling of the Dystrophic mdx Mice Diaphragm. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaulding, H.R.; Kelly, E.M.; Quindry, J.C.; Sheffield, J.B.; Hudson, M.B.; Selsby, J.T. Autophagic dysfunction and autophagosome escape in the mdx mus musculus model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2018, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herhaus, L. TBK1 (TANK-binding kinase 1)-mediated regulation of autophagy in health and disease. Matrix Biology 2021, 100-101, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.M.; Ordureau, A.; Paulo, J.A.; Rinehart, J.; Harper, J.W. The PINK1-PARKIN Mitochondrial Ubiquitylation Pathway Drives a Program of OPTN/NDP52 Recruitment and TBK1 Activation to Promote Mitophagy. Molecular Cell 2015, 60, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Xie, H.; Liu, X.; Potjewyd, F.; James, L.I.; Wilkerson, E.M.; Herring, L.E.; Xie, L.; Chen, X.; Cabrera, J.C.; Hong, K.; Liao, C.; Tan, X.; Baldwin, A.S.; Gong, K.; Zhang, Q. TBK1 Is a Synthetic Lethal Target in Cancer with VHL Loss. Cancer Discovery 2020, 10, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Casanova, J.L.; Sancho-Shimizu, V. Human TBK1: A Gatekeeper of Neuroinflammation. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2016, 22, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizon, V.; Rybina, S.; Gerbal, F.; Delort, F.; Vicart, P.; Baldacci, G.; Karsenti, E. MURF2B, a novel LC3-binding protein, participates with MURF2A in the switch between autophagy and ubiquitin proteasome system during differentiation of C2C12 muscle cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e76140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimauro, I.; Pearson, T.; Caporossi, D.; Jackson, M.J. A simple protocol for the subcellular fractionation of skeletal muscle cells and tissue. BMC Research Notes 2012, 5, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castets, P.; Frank, S.; Sinnreich, M.; Rüegg, M.A. "Get the Balance Right": Pathological Significance of Autophagy Perturbation in Neuromuscular Disorders. Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 2016, 3, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumati, P.; Coletto, L.; Sabatelli, P.; Cescon, M.; Angelin, A.; Bertaggia, E.; Blaauw, B.; Urciuolo, A.; Tiepolo, T.; Merlini, L.; Maraldi, N.M.; Bernardi, P.; Sandri, M.; Bonaldo, P. Autophagy is defective in collagen VI muscular dystrophies, and its reactivation rescues myofiber degeneration. Nature Medicine 2010, 16, 1313–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanin, M.; Nascimbeni, A.C.; Angelini, C. Muscle atrophy, ubiquitin-proteasome, and autophagic pathways in dysferlinopathy. Muscle Nerve 2014, 50, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Marker | Muscle | Age | Regulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC3 I | gastrocnemius | 11 months | D2-MDX > BL 10 | [40] |

| diaphragm | 11 months | D2-MDX > BL 10 | [40] | |

| heart | 7 weeks | MDX ≅ BL 10 | [41] | |

| heart | 5.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | [42] | |

| heart | 14 months | MDX ≅ BL 10 | [41] | |

| heart | 17 months | MDX ≅ BL 10 | [41] | |

| LC3 II | tibialis anterior | 5.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | [43] |

| extensor digitorum longus | 5 weeks | MDX*≅ BL 10 | this study | |

| gastrocnemius | 5 weeks | MDX*≅BL 10 | this study | |

| gastrocnemius | 11 months | D2-MDX ≅ BL 10 | [40] | |

| diaphragm | 11 months | D2-MDX ≅ BL 10 | [40] | |

| heart | 7 weeks | MDX ≅ BL 10 | [41] | |

| heart | 5.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | [42] | |

| heart | 12 months | MDX > BL 10 | [44] | |

| heart | 14 months | MDX < BL 10 | [41] | |

| heart | 17 months | MDX < BL 10 | [41] | |

| LC3 II/I | quadriceps | 5.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | [14] |

| tibialis anterior | 4 months | MDX > BL 10 | [45] | |

| extensor digitorum longus | 6.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | this study | |

| gastrocnemius | 11 months | D2-MDX ≅ BL 10 | [40] | |

| soleus | 3.5 months | MDX < BL 10 | [46] | |

| diaphragm | 6 weeks | MDX > BL 10 | [47] | |

| diaphragm | 3 months | MDX > BL 10 | [47] | |

| diaphragm | 4 months | MDX > BL 10 | [45] | |

| diaphragm | 11 months | D2-MDX ≅ BL 10 | [40] | |

| heart | 14 months | MDX ≅ BL 10 | [41] | |

| SQSTM1 | quadriceps | 5.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | [14] |

| tibialis anterior | 4 months | MDX > BL 10 | [45] | |

| tibialis anterior | 5.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | [43] | |

| extensor digitorum longus | 5 weeks | MDX*≅ BL 10 | this study | |

| gastrocnemius | 5 weeks | MDX*≅ BL 10 | this study | |

| gastrocnemius | 11 months | D2-MDX < BL 10 | [40] | |

| soleus | 3.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | [46] | |

| diaphragm | 4 months | MDX > BL 10 | [45] | |

| diaphragm | 11 months | D2-MDX > BL 10 | [40] | |

| heart | 7 weeks | MDX ≅ BL 10 | [41] | |

| heart | 5.5 months | MDX > BL 10 | [42] | |

| heart | 12 months | MDX > BL 10 | [44] | |

| heart | 14 months | MDX ≅ BL 10 | [41] | |

| heart | 17 months | MDX ≅ BL 10 | [41] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).