1. Introduction

Low dimensional quantum spin models have long been the subject of many theoretical and experimental approaches. The interest in such systems comes mainly due to two factors. First, there are several strong experimental appeals, because some physical realizations, when viewed by the relevant microscopic quantum interactions consist, in fact, of single molecules, or linear chains, or even ladder-like structures. Just to cite a few examples among the vast list of experimental results that fall in these scenarios, we have:

i) molecular magnetism in Cu5-NIPA [

1], V6-like magnetic molecules [

2], and multiferroics [

3] (these compounds can be considered as zero-dimensional systems);

ii) TMMC, CsNiF

3, and CuCl

22NC

5H

5 exhibiting one-dimensional character [

4];

iii) ladder-type structures as in (VO)

2P

2O

7[

5], Cu(C

5H

12N

2)

22Cl

4[

6], as well as cuprates La

2CuO

4 and La

6Ca

8Cu

24O

41[

7,

8,

9,

10]. Of course, the majority of the physical realizations have indeed the main quantum interactions along the three crystalline dimensions. Second, it is a real challenge to treat quantum models even in low dimensions, since the statistical mechanics of a

d-dimensional quantum model is equivalent to a

-classical model [

11], implying that even one-dimensional quantum systems can undergo a critical phase transition at zero temperature, the so called

quantum phase transition.

Despite in all physical realizations cited above the nearest-neighbor exchange being the relevant interaction, four-spin interactions in a plaquette have been suggested to reproduce the dispersion relation observed in inelastic neutron scattering experiments on cuprates [

7,

8,

9,

10] and even to stabilize a chiral spin liquid on the triangular lattice [

12]. This new experimental motivation has lead to an increase in theoretical investigations of quantum Ising-like models defined on a ladder, specially with four-spin interaction that has been shown to induce other unusual types of order, such as scalar chirality and intra-rail staggered dimerization (see, for instance, Ref. [

13] and references therein).

The spin-1/2 quantum transverse Ising model, defined on a ladder structure, with nearest-neighbor interaction, has been one of the most studied models in the literature. In particular, the model including a four-spin interaction on a plaquette, has been recently studied by using the density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) approach [

13] (the dynamical behavior has also been recently studied via the recurrence relation method [

14]). The ground state phase diagram has been obtained in the transverse field versus four-spin interaction plane. In this case, a ferromagnetic to paramagnetic second-order phase transition is observed and, for high enough antiferromagnetic four-spin couplings, the system presents a dimer phase and a multicritical point.

In the present work, we have revisited this model and used the exact diagonalization on finite lattices. The energy gap has been computed and from the corresponding finite-size-scaling (FSS) relation the critical transverse field has been obtained for several values of the four-spin interaction. The ferromagnetic-paramagnetic phase transition line has thus been obtained in the thermodynamic limit. The results agree well with those previously obtained from DMRG [

13]. However, contrary to the model with four-spin interactions in one dimension [

15], in the ladder structure it has been noticed that there are much stronger finite-size effects and one has to use indeed the larger possible lattices for the extrapolations. Moreover, the ferromagnetic-paramagnetic transition line on the ladder does not go to zero at the multiphase point in the classical limit of vanishing transverse field, as does the one-dimensional model.

The plan of the paper is the following. In the next section, the model is defined and the configurations in the classical limit is discussed.

Section 3 describes the theoretical approach using the exact diagonalization on finite ladders and the corresponding FSS relation for the energy gap and critical transverse field. The results of the transition line are presented in

Section 4 and some concluding remarks are addressed in the final Section.

2. Model

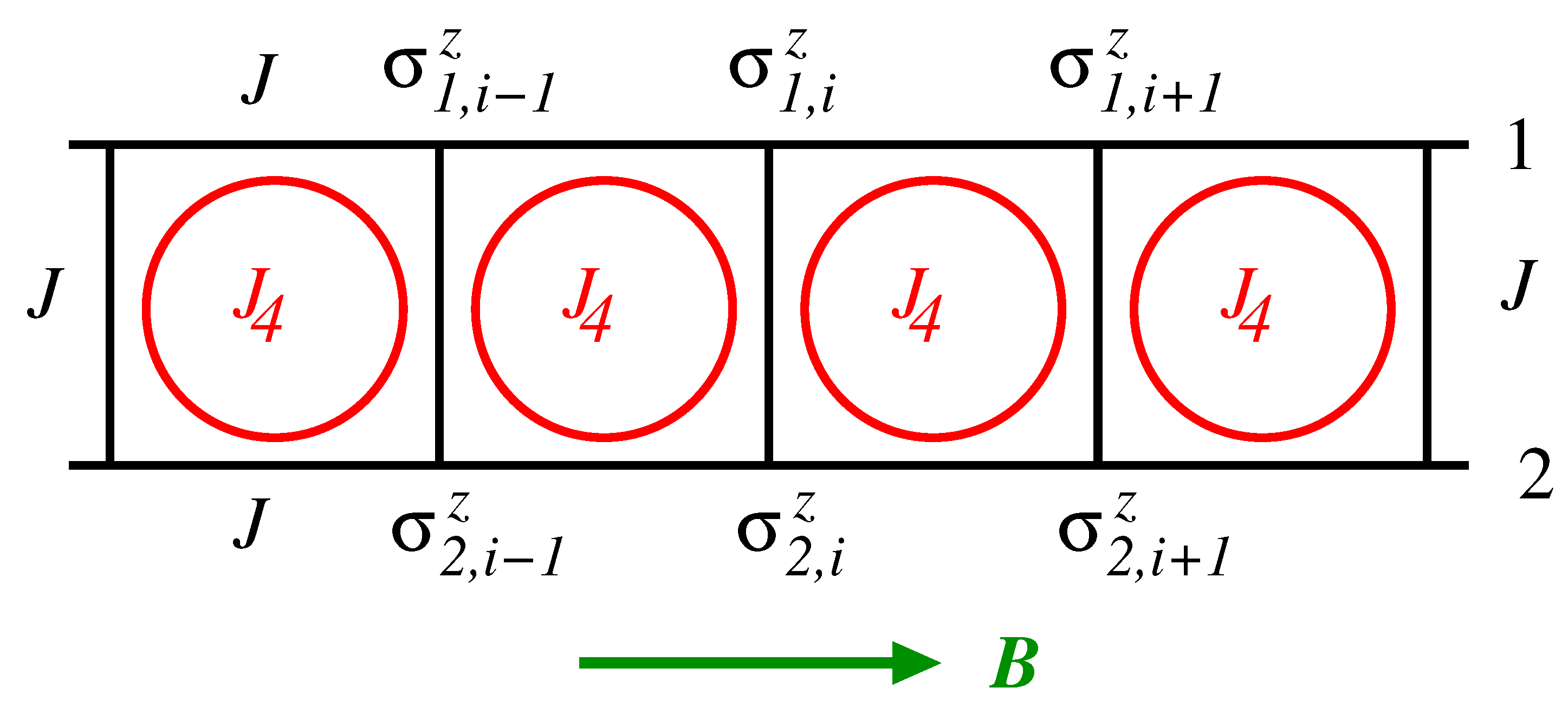

The Hamiltonian of the spin-1/2 Ising model, defined on a ladder structure, as depicted in

Figure 1, with four-spin interaction and in the presence of a transverse field, can be written as

where

is the nearest-neighbor exchange interaction along the rails and in the rungs,

is the four-spin interaction connecting the spins in a plaquette, and

B is the transverse external field applied in the

x direction. The sums are over the

L rungs of a ladder with periodic boundary conditions in the direction of the two side rails denoted, respectively, by 1 and 2. The spin-1/2 operators

, with

and

, are given by the Pauli spin matrices.

Due to the positiveness convention of the four-spin interaction in the Hamiltonian (

1), when

the plaquette ordering is also ferromagnetic for low values of transverse fields. As a result, the system undergoes a second-order transition from a ferromagnetic phase to a paramagnetic phase at a critical transverse field value

. This critical transverse field decreases as

increases. As has been shown in Ref. [

13], when

, this transition persists till some value of

(that is

B dependent) where a dimer phase is set up in the ladder.

At , one has a classical system with a multiphase point at dividing the classical axis into two regions: 1) for a double degenerated ferromagnetic phase, and 2) for a ground state that is degenerate, with a residual entropy (here, the Boltzmann constant).

Contrary to what happens in the one-dimensional model with four-spin interaction along a straight line [

15], the ferromagnetic-paramagnetic transition line does not terminate at the multiphase point at

. This is a consequence of the ladder structure allowing the appearance of the rung dimerized phase [

13].

3. Theoretical background

We have used finite ladders of length

L, with

sites, and periodic boundary conditions. For each ladder, the energy gap

has been computed. The quantity

is given by

where

is the energy gap between the first excited state and the ground state, respectively.

is equivalent to the correlation length in thermal systems and satisfies the FSS relation [

16]

for two finite ladders of length

L and

, with usually

. From the above relation, it is possible to estimate

, the critical field for the ladder pair (

).

For large enough lattices, it is expected the quantities

, as a function of

B for a given value of

, to cross at the same point

, the critical transverse field for the considered value of

. However, in some cases, where the finite lattices are not large enough, residual corrections make the crossing points

suffer a systematic shift as

L varies. Nevertheless, there is an additional FSS relation for the

L dependence on the transition points

given by [

17]

where

is the critical transverse field in the thermodynamic limit,

is the correlation length critical exponent,

is the correction-to-scaling exponent, and

a and

b are non-universal constants. In this way, for every chosen value of

and reference ladder

, one obtains the crossing point

for the ladder pair (

) through Eq. (

3). Next, using Eq. (

4) for various values of

L, one computes the desired extrapolated value of critical transverse field.

In the present work, the energy gap has been obtained through exact diagonalization of finite ladders with length

L in the range

. For the larger lattices, we have employed the Lanczos diagonalization procedure [

18].

4. Results and discussion

In what follows, we have considered . This value of J can also be interpreted as measuring the four-spin interaction , as well as the transverse field strength B, in units of J.

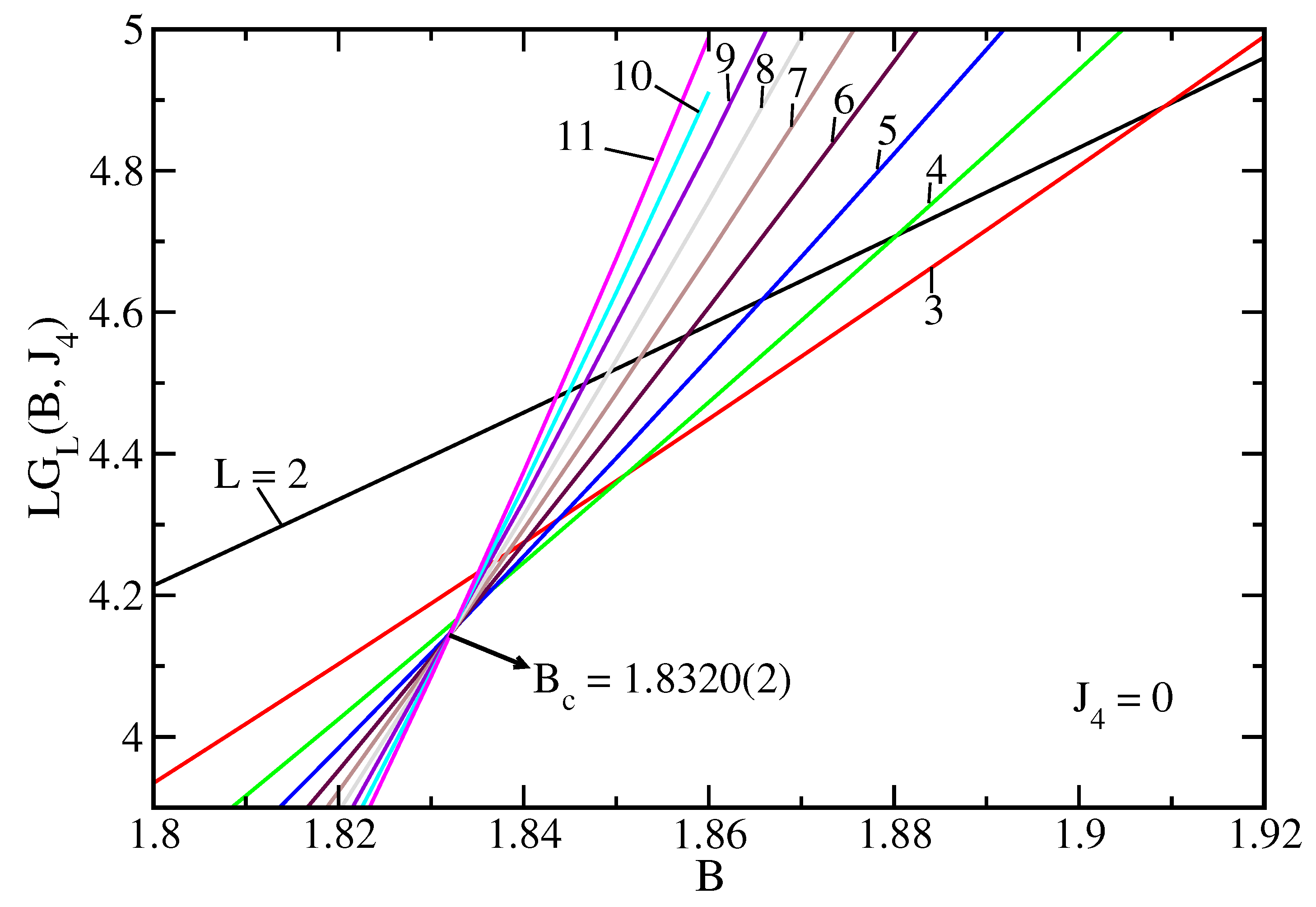

As an example of the behavior of energy gap as a function of the transverse field,

Figure 2 shows

for several values of

L and

. In this case, we simply have the transverse Ising model on a ladder [

19]. It is clear that a small region of unique crossings is only achieved for the larger ladders. The estimate of the critical transverse field, in this case, is enlighten by the corresponding arrow.

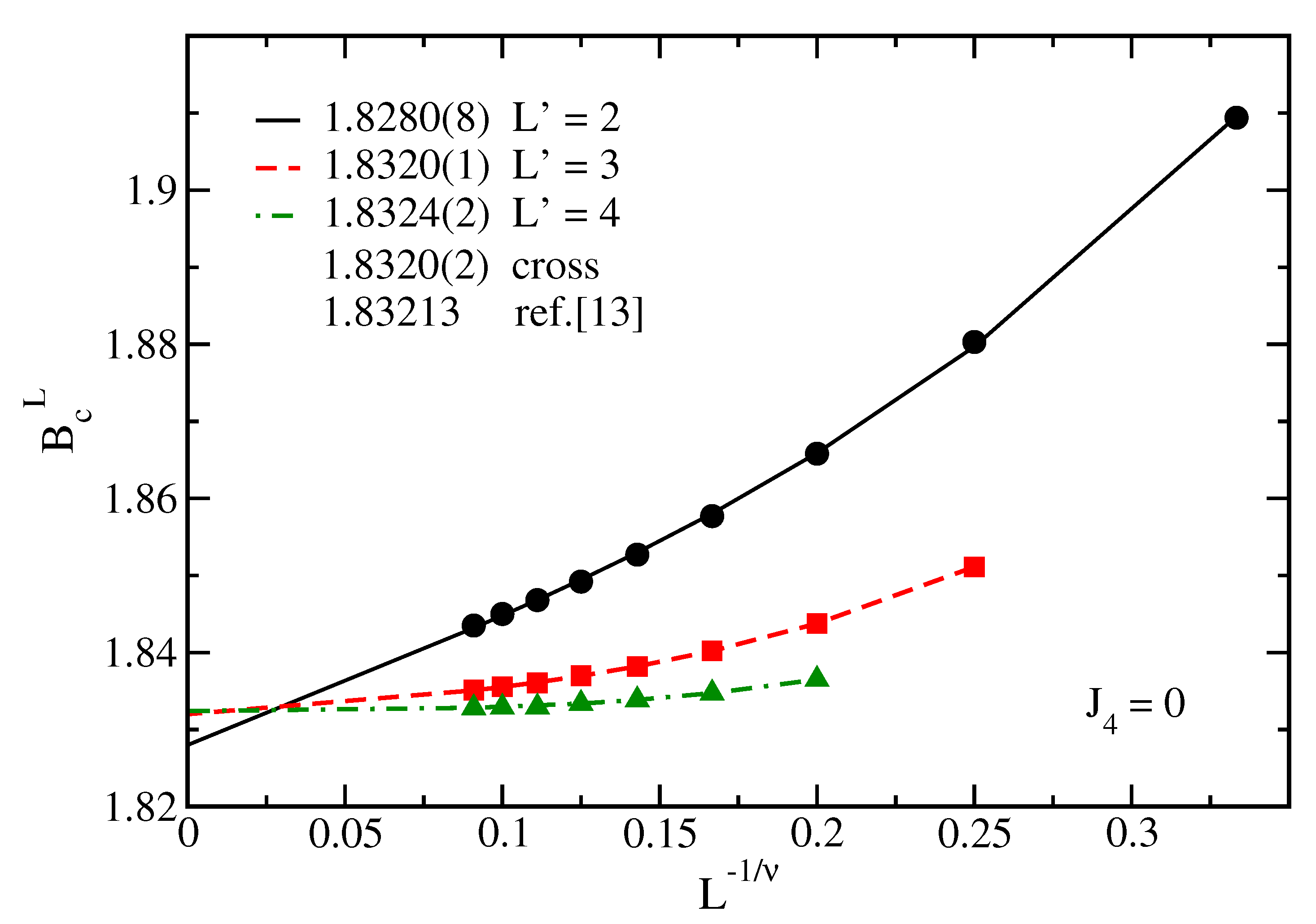

It is also evident in that figure that for smaller ladders there is a shift in the values of crossings

. We can thus compute

by taking a reference lattice

and several values of

. From the results of

Figure 2, it is possible to have a clear crossing by using

, and 4. The results so obtained are depicted in

Figure 3, which allows one to obtain additional extrapolated estimates of

through fits to Eq. (

4) for each value of the reference ladder

. The present estimate

agrees very well with

coming from DMRG of Ref. [

13] using a finite ladder with length

.

It should be stressed that in using Eq. (

4) one needs the exponents

and

. Although from Eq. (

3) it is possible to compute

using renormalization group ideas and estimates of

[

15,

20] (for instance, from the values of the crossings

for the larger ladders) the obtained results are close to the exact ones for this universality class. However, the correction-to-scaling exponent cannot be obtained in this way and, at least, should be treated as an extra adjustable parameter. For this reason, and from the fact that we are indeed more interested in the location of the transition line, we have resorted to the known values

and

for the Ising universality class in order to compute the extrapolated critical transverse field.

Similar curves, with similar FSS analysis, are obtained when

.

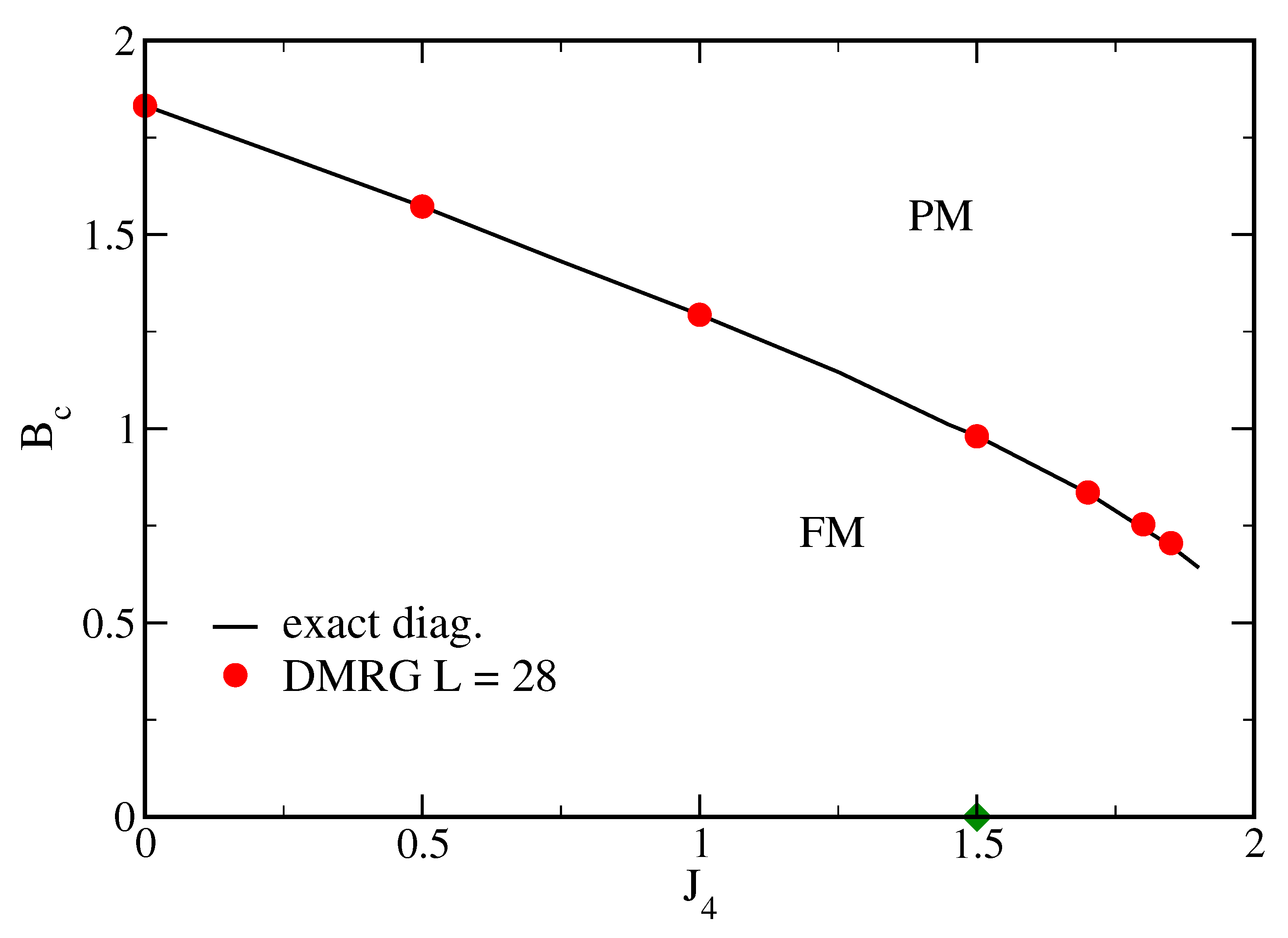

Figure 4 shows the critical transverse field

as a function of

obtained from the present method in comparison to some results from DMRG of Ref. [

13]. One can clearly see that, contrary of what happens for the very same model in one dimension [

15] (with four-spin interactions along a straight line), the transition line definitely does not go to zero as

tends to 3/2, the multiphase point. The agreement with DMRG results is not only apparent in

Figure 4 but also in

Table 1, that gives a more detailed numerical comparison for some selected values of

.

5. Concluding remarks

The transverse Ising model, defined on a ladder and with four-spin interactions on a plaquette, has been studied by using the finite-size-scaling approach with exact diagonalization of finite ladders. The method has furnished quite good results for the ferromagnetic to paramagnetic transition line in the transverse field versus four-spin interaction plane. The computed critical transverse field, in the themdynamic limit, are also in good agreement with those coming from density matrix renormalization group procedure.

Despite the expected efficacy of the FSS along the ferromagnetic-paramagnetic transition line, the model shows, in fact, strong finite-size effects, and only with considerably larger lattices the results could be accurately obtained. One unexpected feature consists in the method being unable to locate the dimerized phase and the corresponding transition that occurs to the ferromagentic and paramagnetic phases. For values the crossings become more difuse and in some regions it is not possible to obtain good fits with the expected scaling relation. Perhaps more suitable quantities than the energy gap should be necessary to unveil the transition character and the microscopic spin behavior for larger values of the four-spin interaction.

6. Aknowledgments

The authors would like to thank F. C. Xavier and R. G. Pereira for fruitful discussions, and the former for the invaluable help in implementing the Lanczos algorithm in the ladder lattice. This work has been partially funded by the Brazilian agencies CNPq, CAPES, FAPEMIG and FUNCAP. Special thanks are due to Professor S.-H. Tsai for the help in using the GACRC facilities of the cluster at the University of Georgia in the USA, and Professor G. Weber for the use of the workstations of the Statistical Physics group at UFMG in Brazil. Computational support by the system SGI Altix 1350, the CENAPAD.UNICAMP-USP computational park, Campinas, São Paulo - BRAZIL, is also gratefully acknowledged.

References

- R. Nath et al., Phys. Rev. B 87 214417 (2013).

- P. Kowalewska and K. Szalowski, J. Mag. Mag. Mat. 496 165933 (2020).

- A. Valentim, D. J. García , and J. A. Plascak, Phys. Rev. B 105 174426 (2022).

- H.J. Mikeska, J. Magn. Magn. Mat. 13 35 (1979).

- D. C. Johnston, J.W. Johnston, D. P. Goshorn and A. J. Jacobson, Phys. Rev. B 35 219 (1987).

- M. Hagiwara, H. A. Katori, U. Schollwock and H. J. Mikeska, Phys. Rev. B 62 1051 (2000).

- S. Brehmer, H.-J. Mikeska, M. Müller, N. Nagaosa, and S. Uchida, Phys. Rev. B 60 329 (1999).

- M. Matsuda, K. Katsumata, R. S. Eccleston, S. Brehmer, and H.-J. Mikeska, Phys. Rev. B 62 8903 (2000).

- R. Coldea, S. M. Hayden, G. Aeppli, T. G. Perring, C. D. Frost, T. E. Mason, S.-W. Cheong, and Z. Fisk, Phys. Rev. Lett. 86 5377 (2001).

- C. B. Larsen, A. T. Romer, S. Janas, F. Treue, B. Monsted, N. E. Shaik, H. M. Ronnow, and K. Lefmann, Phys. Rev. B 99 054432 (2019).

- see for instance, S. Sachdev, Quantum Phase Transitions, second edition, Cambridge University Press, New York (2011).

- T. Cookmeyer, J. Motruk, and J. E. Moore, Phys. Rev. Lett. 127 087201 (2021).

- J.C. Xavier, R.G. Pereira, M.E.S. Nunes, and J.A. Plascak, Phys. Rev. B 105 024430 (2022).

- Wescley Luiz de Souza, Érica de Mello Silva, and Paulo H. L. Martins, Phys. Rev. E 101 042104 (2020).

- Paulo R. Colares Guimarães, J. A. Plascak, F. C. Sá Barreto, and J. Florêncio, Phys. Rev. B 66 064413 (2002).

- M.N. Barber, in Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena, edited by C. Domb and J.L. Lebowitz, Academic, London (1983).

- see, for instance, D. P. Landau and K. Binder, A Guide to Monte Carlo Simulation in Statistical Physics, 5th Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2021).

- G. H. Golub and C. F. van Loan, Matrix Computations, 3rd ed., Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (1996).

- J. C. Xavier and F. B. Ramos, J. Stat. Mech. P10034 (2014).

- O. F. de Alcantara Bonfim and J. Florêncio, Phys. Rev. B 74 134413 (2006).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).