Submitted:

02 November 2023

Posted:

02 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

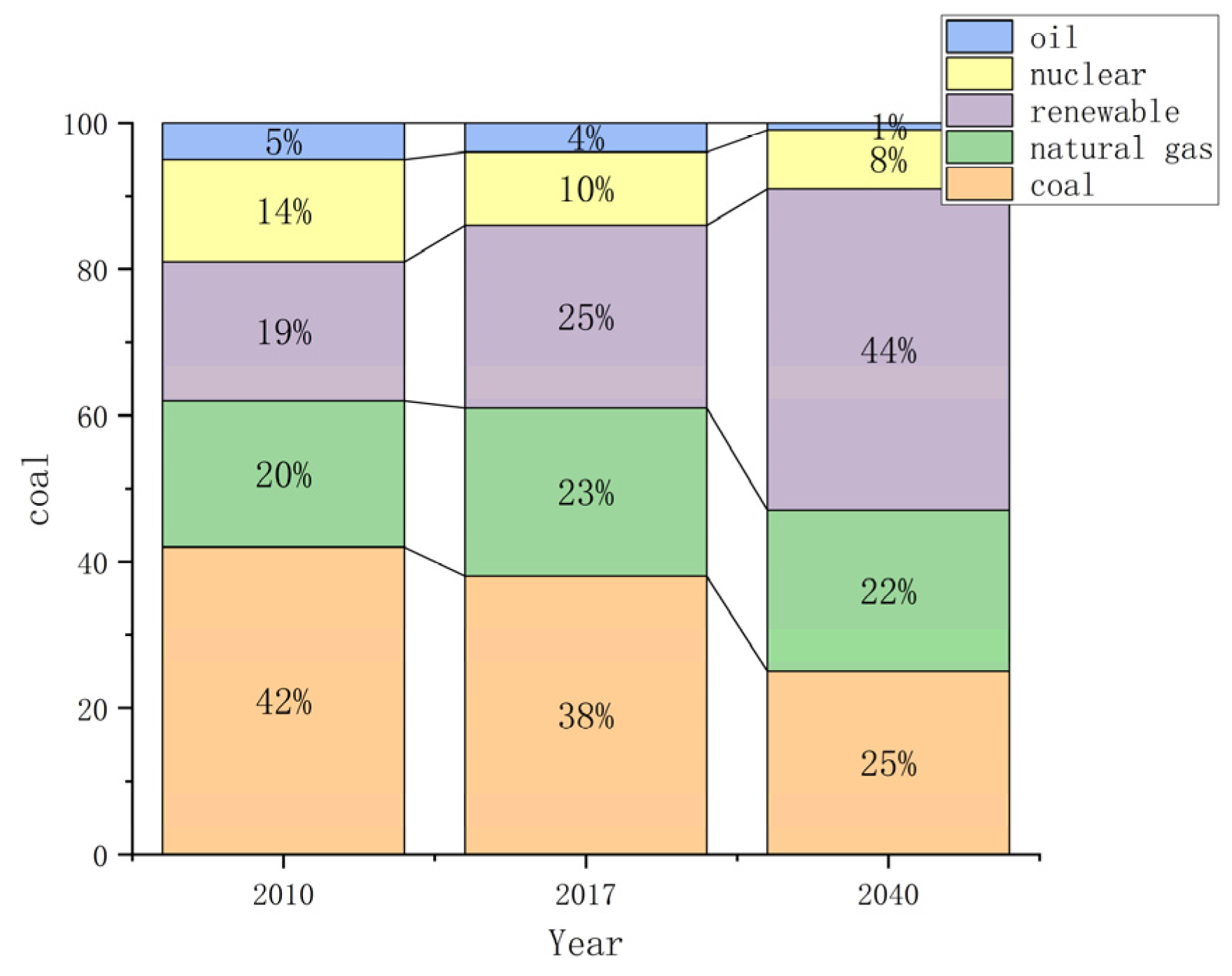

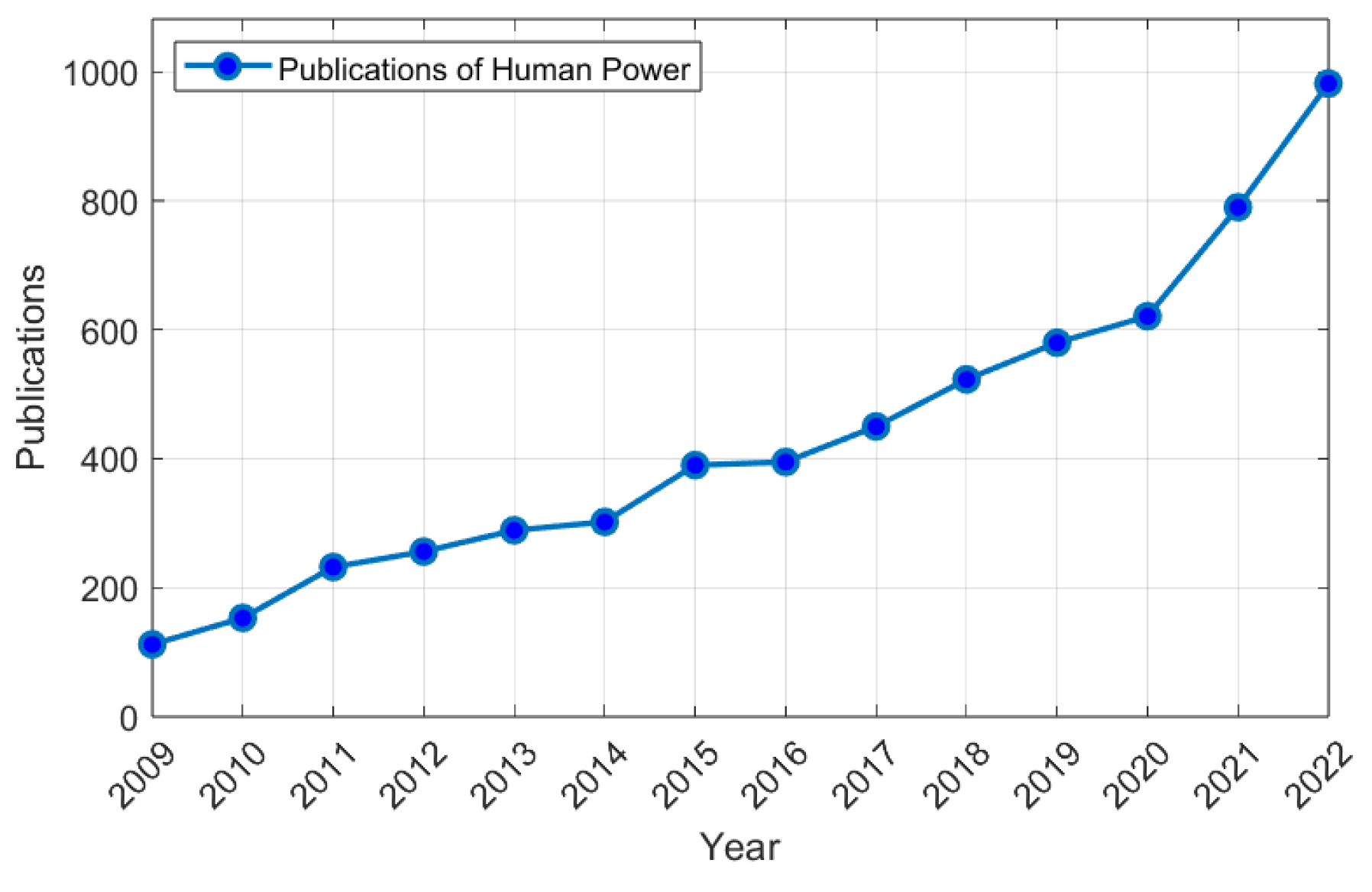

1. Introduction

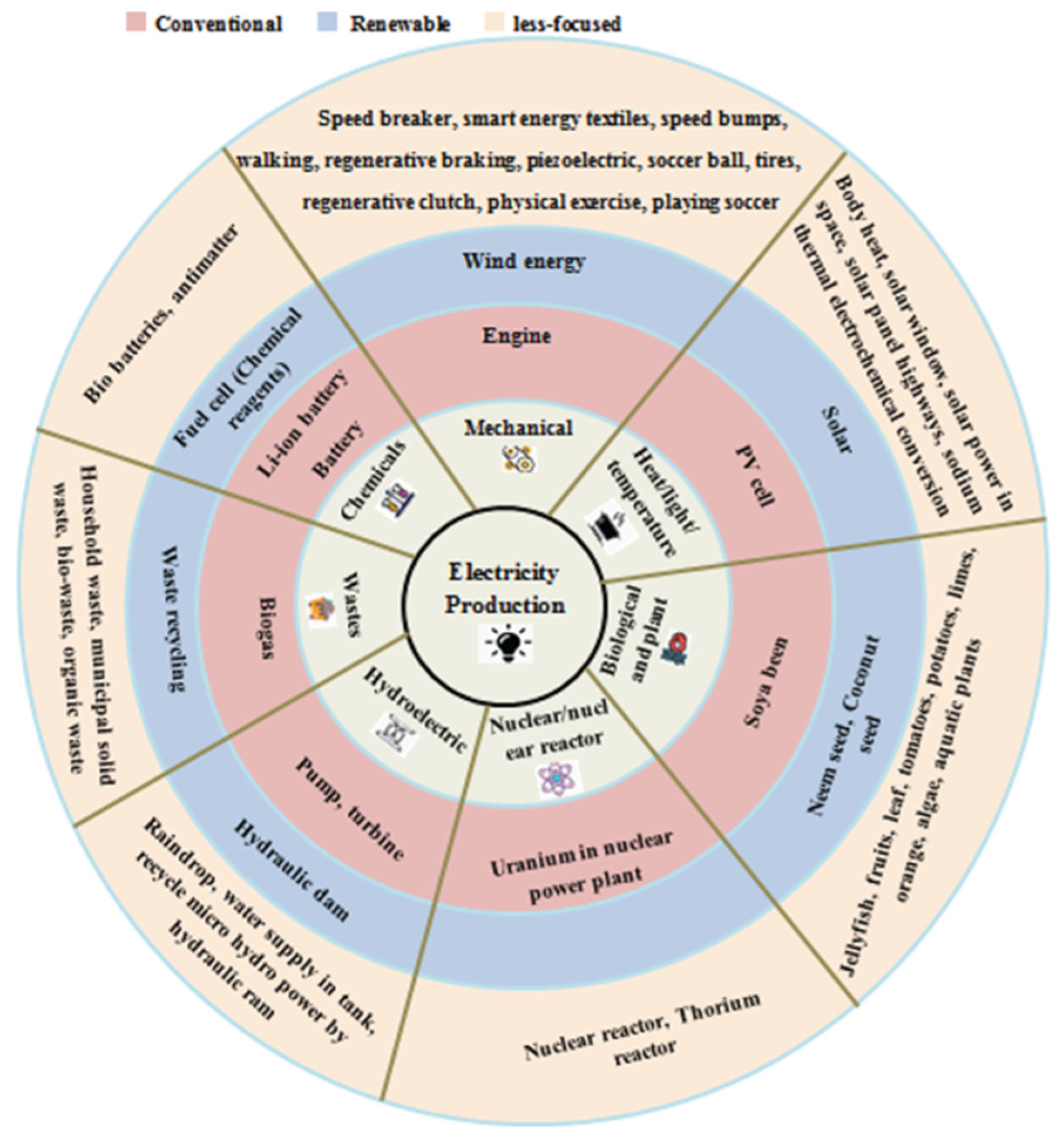

2. Human energy sources

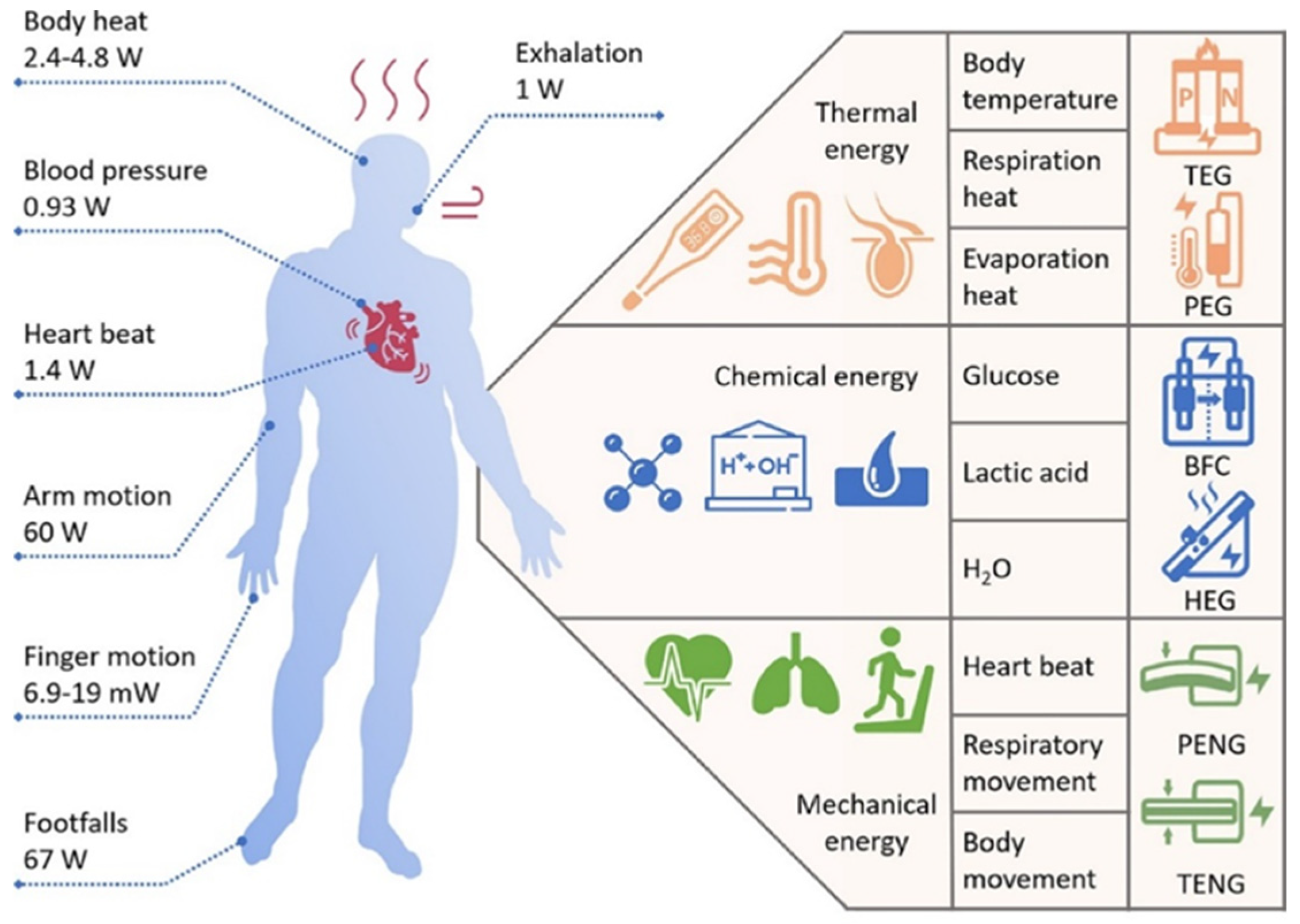

2.1. Thermal energy

2.2. Mechanical energy

2.3. Chemical energy

3. Harvesting Human Energy

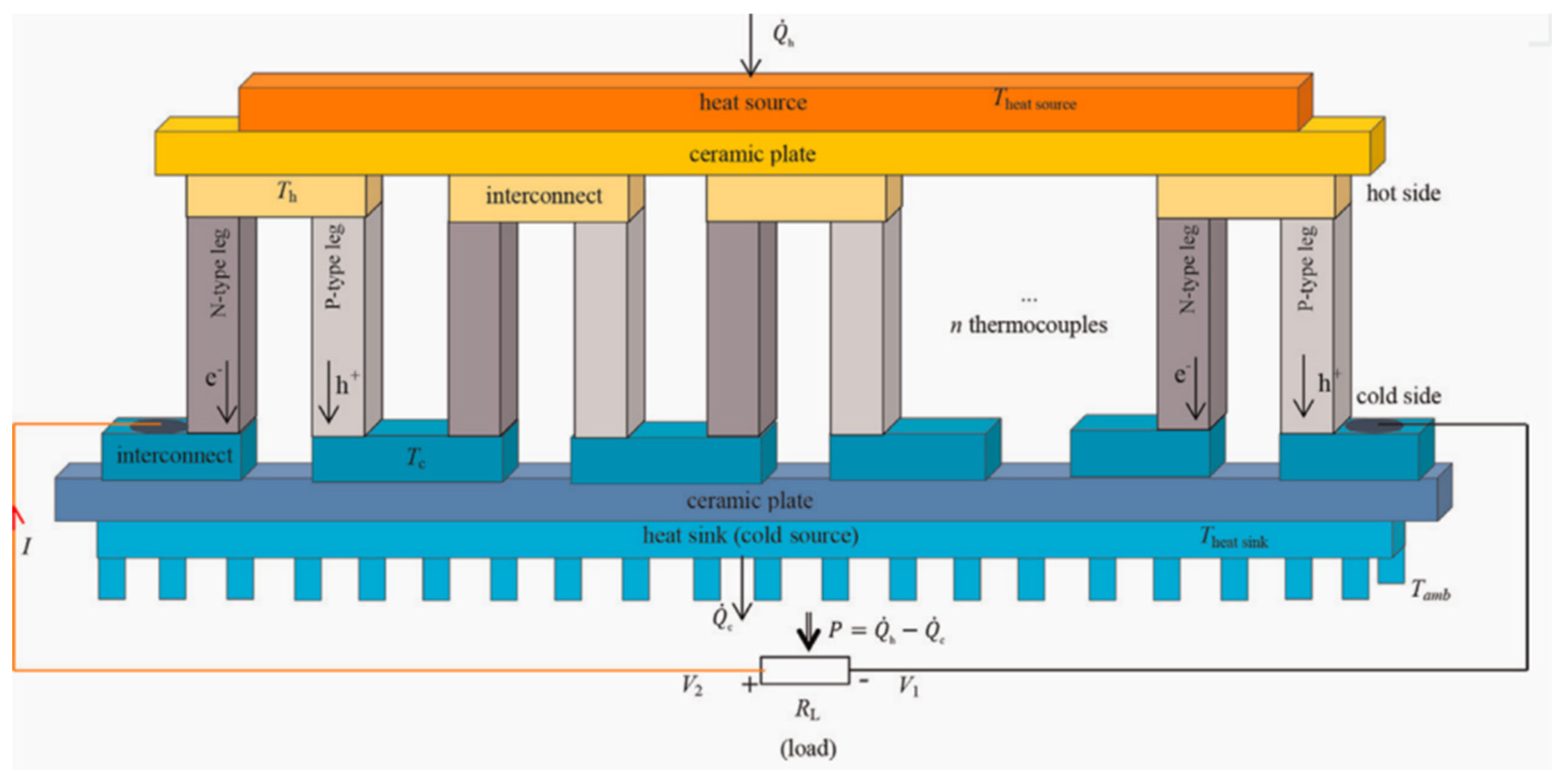

3.1. Thermoelectric energy harvesting

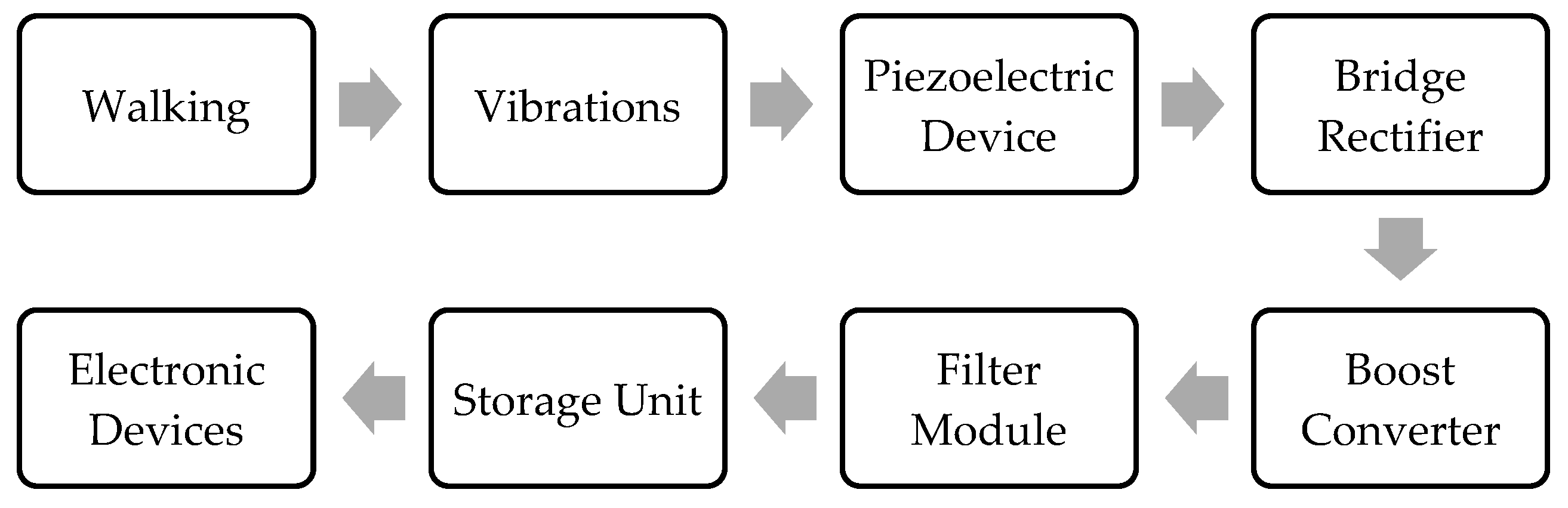

3.2. Piezoelectric generator

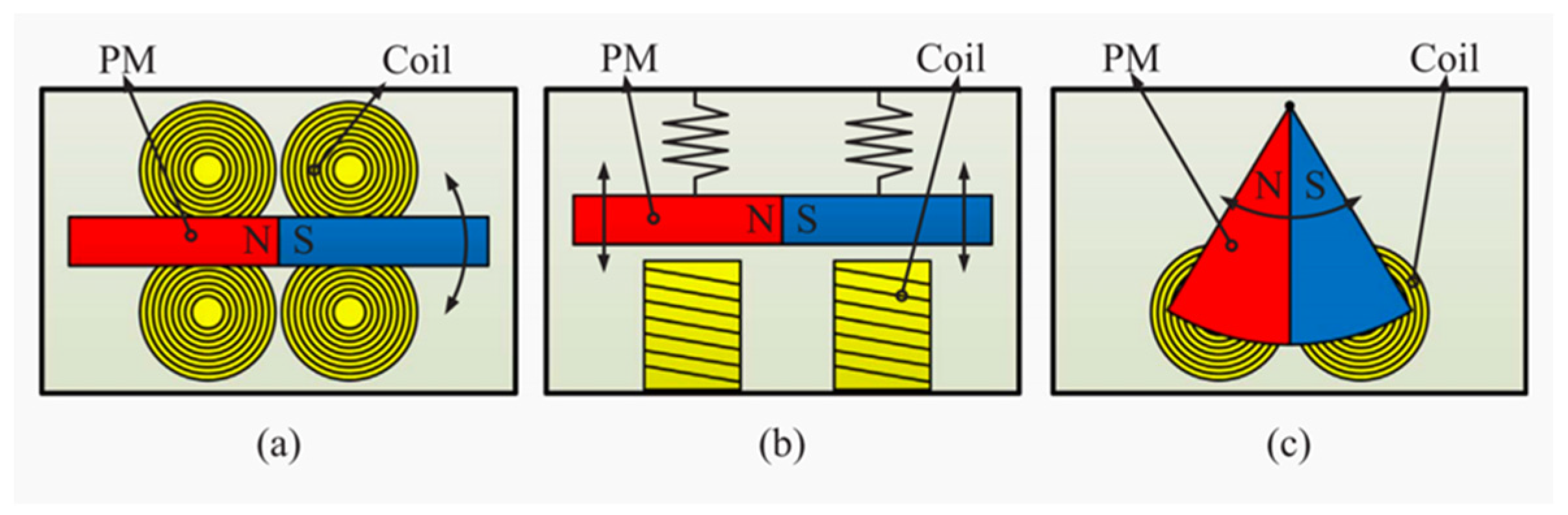

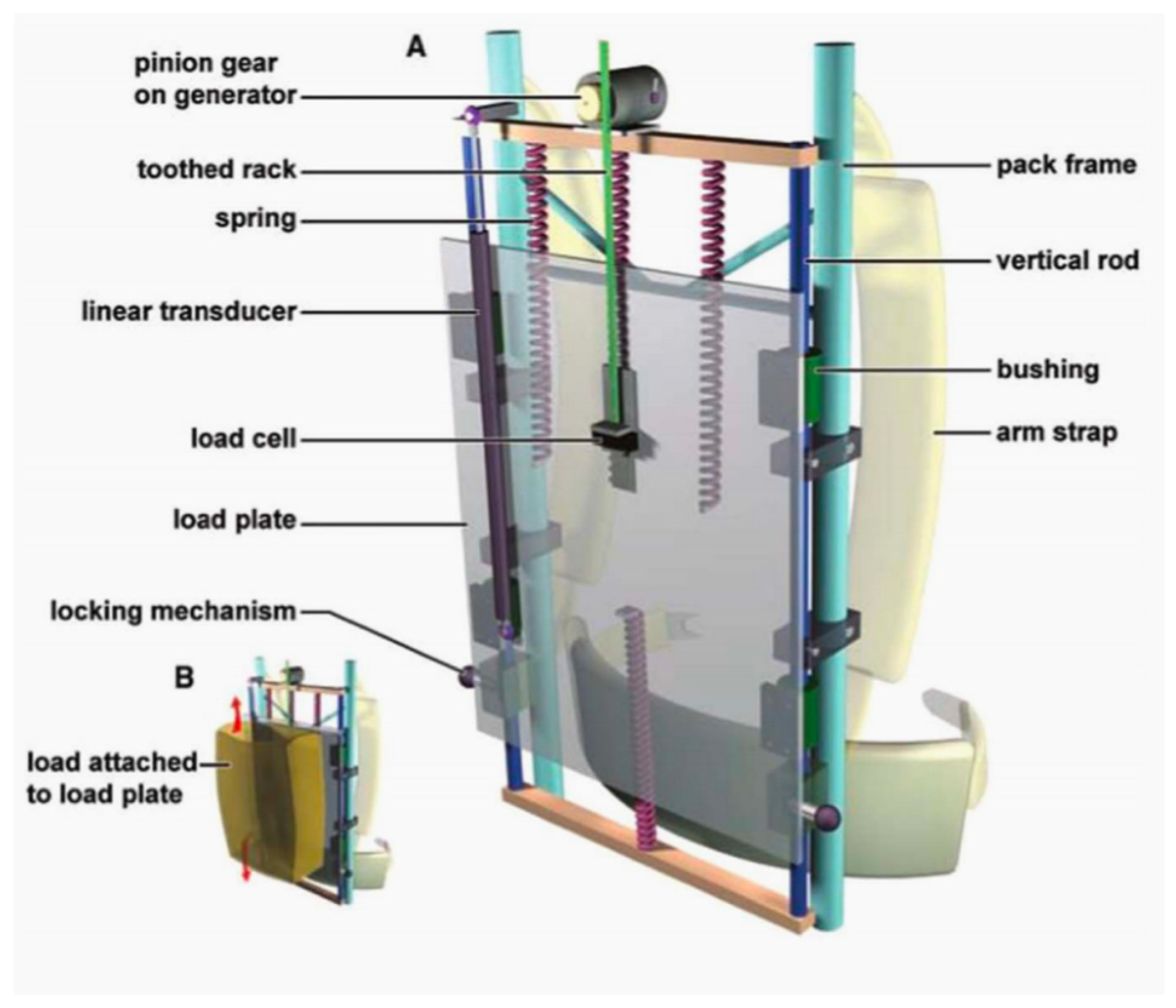

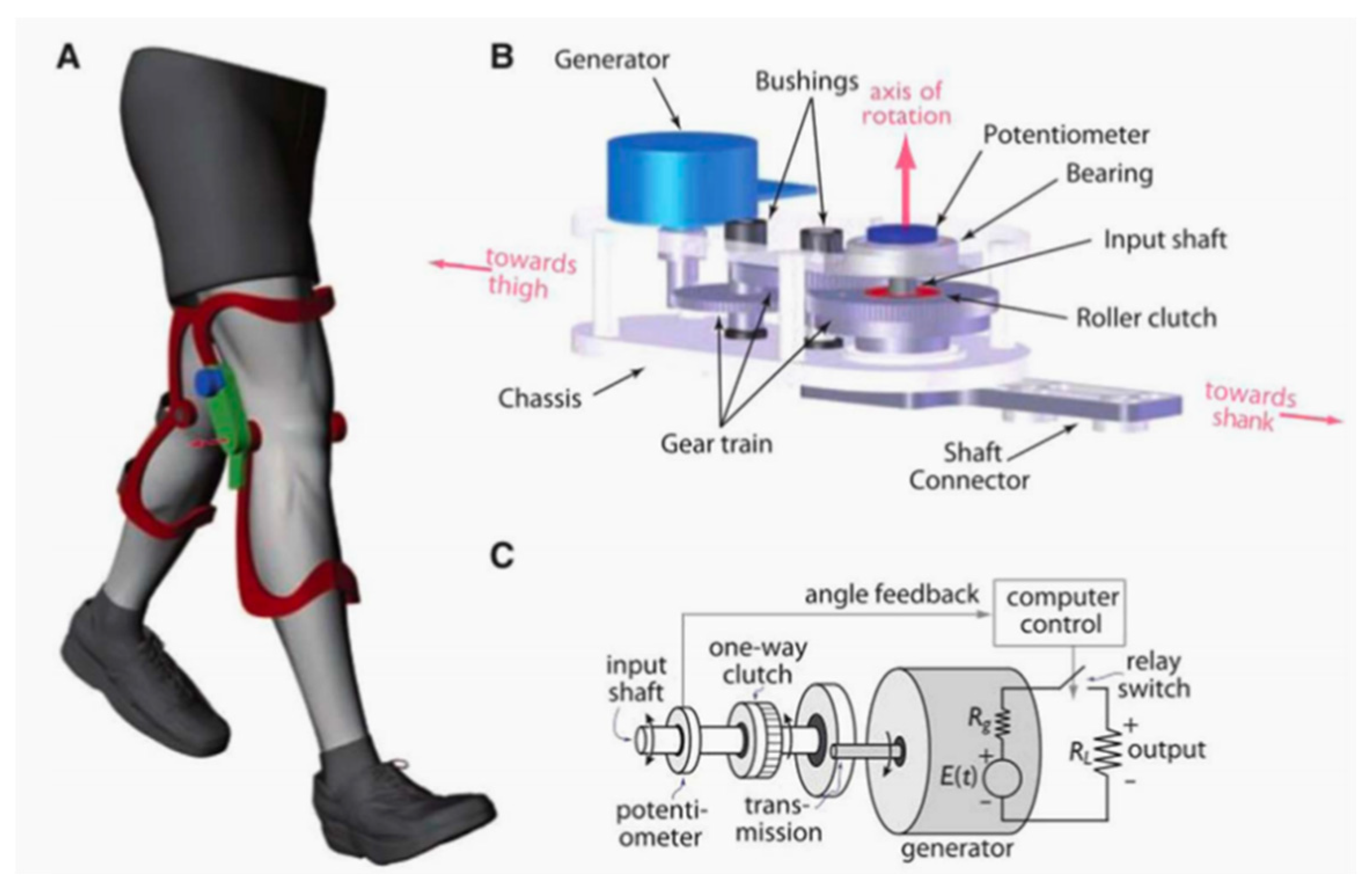

3.3. Electromagnetic Generators

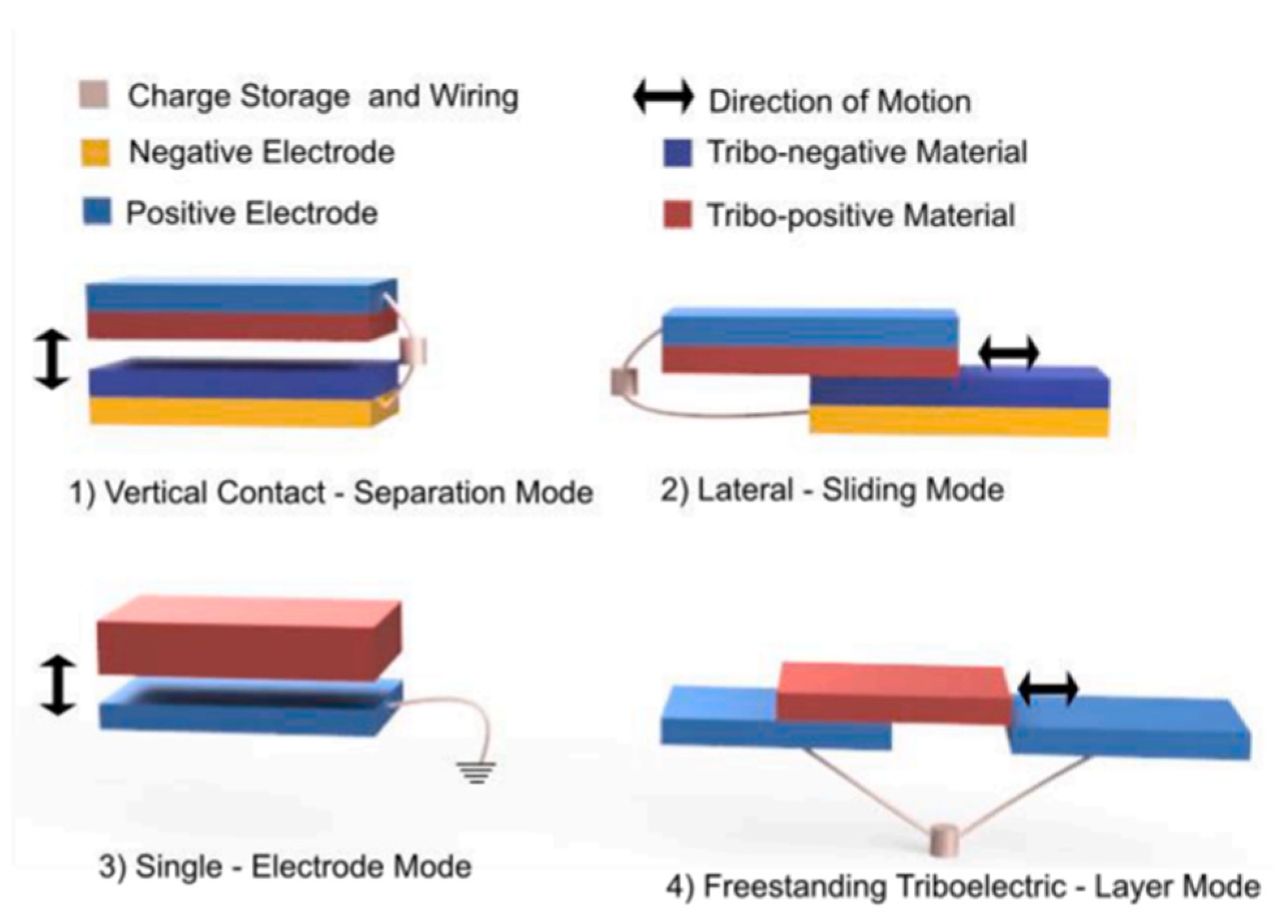

3.4. Triboelectric generators

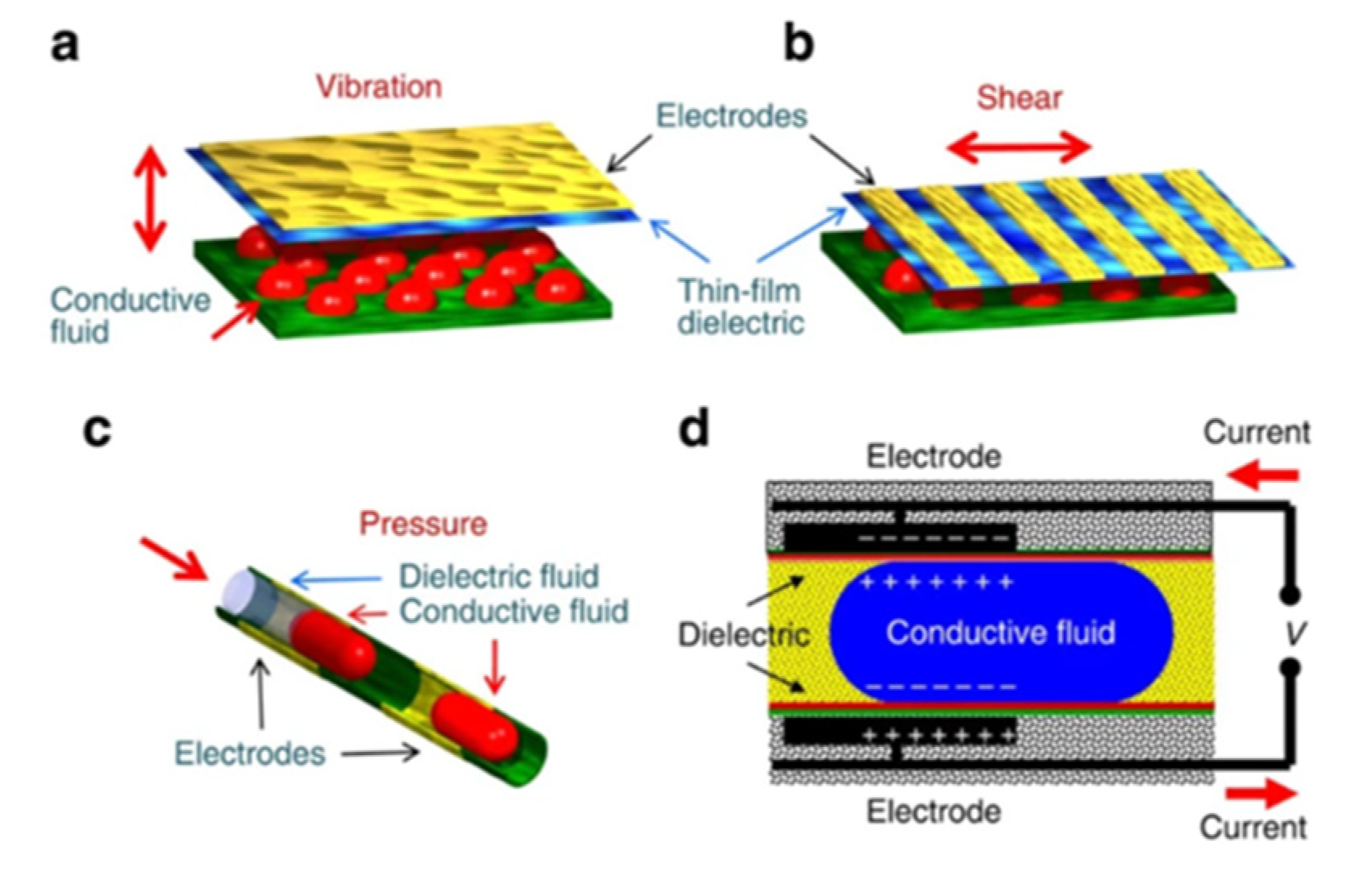

3.5. Reverse electro-wetting generator

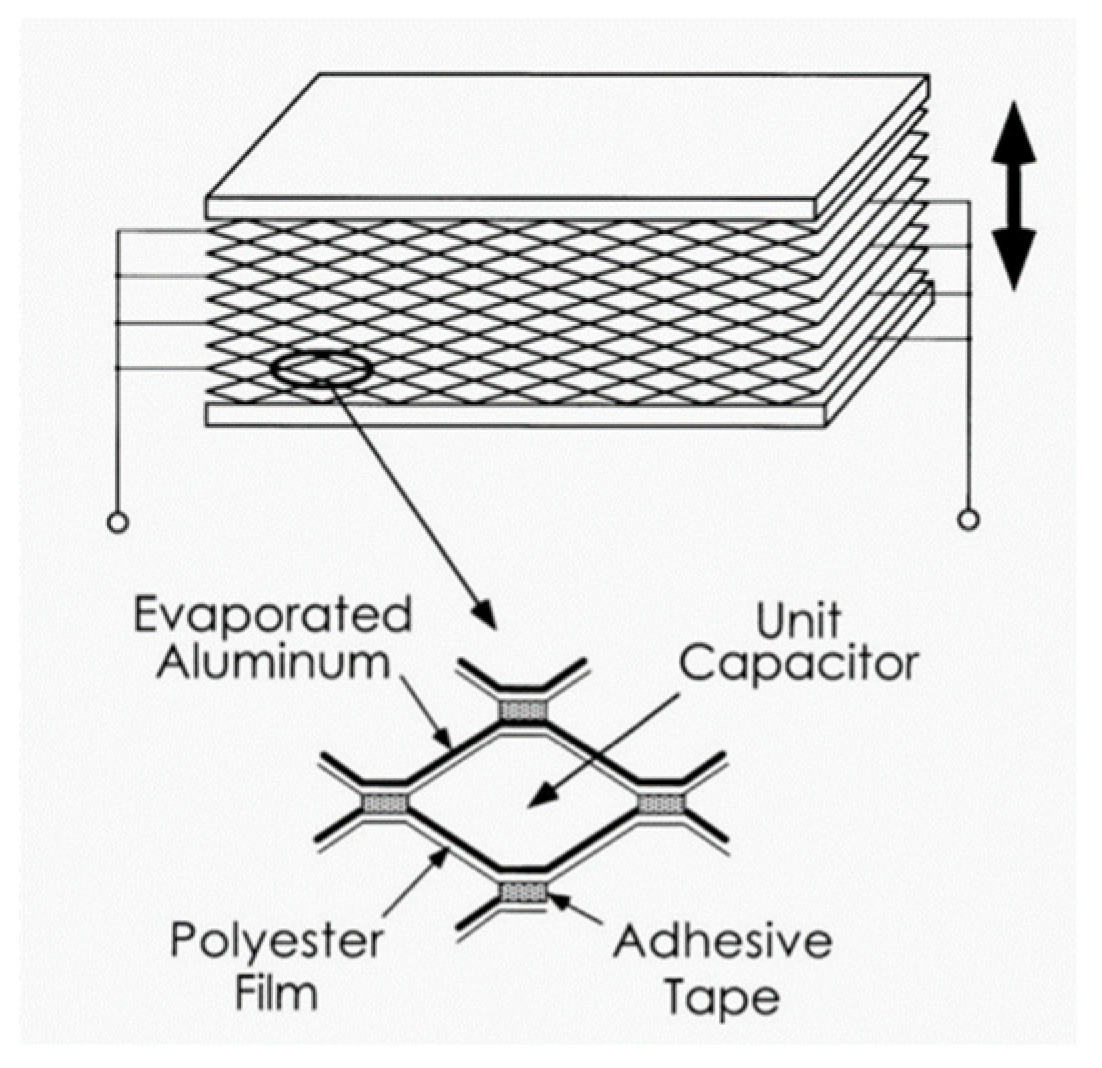

3.6. Electrostatic (dielectric elastomer)

4. Practical applications of human-powered electricity generation

4.1. Emergencies and times of war

4.1.1. Hand-cranked generators in war

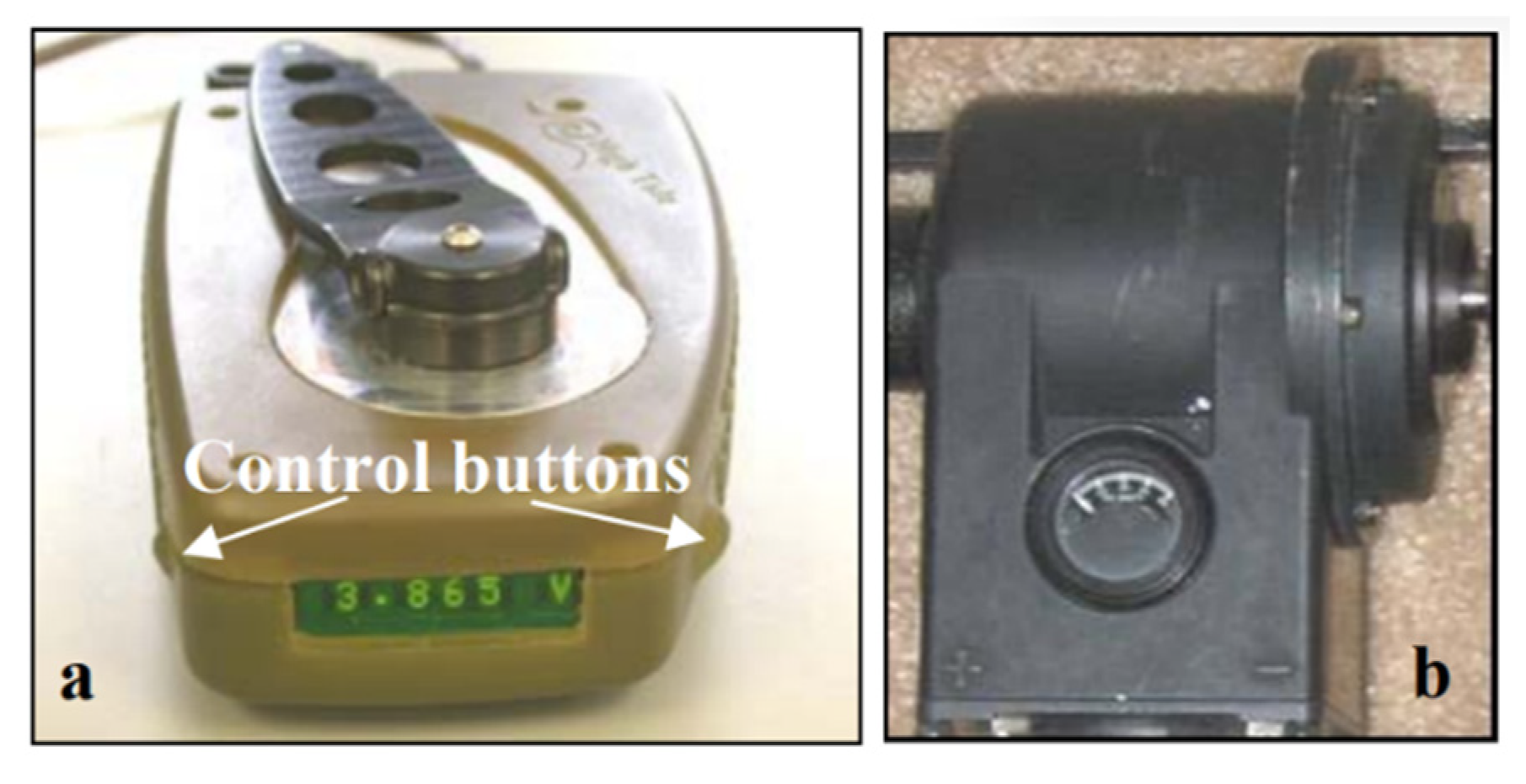

4.1.2. Emergency broadcasting and modern human power generation products

4.2. Human power generation in fitness

4.2.1. Electricity generation in particular scenarios (gym)

4.2.2. Electricity generation for daily life

5. Opportunities and challenges of human power generation

5.1. Opportunities

5.1.1. Provide a large number of jobs and maintain social stability

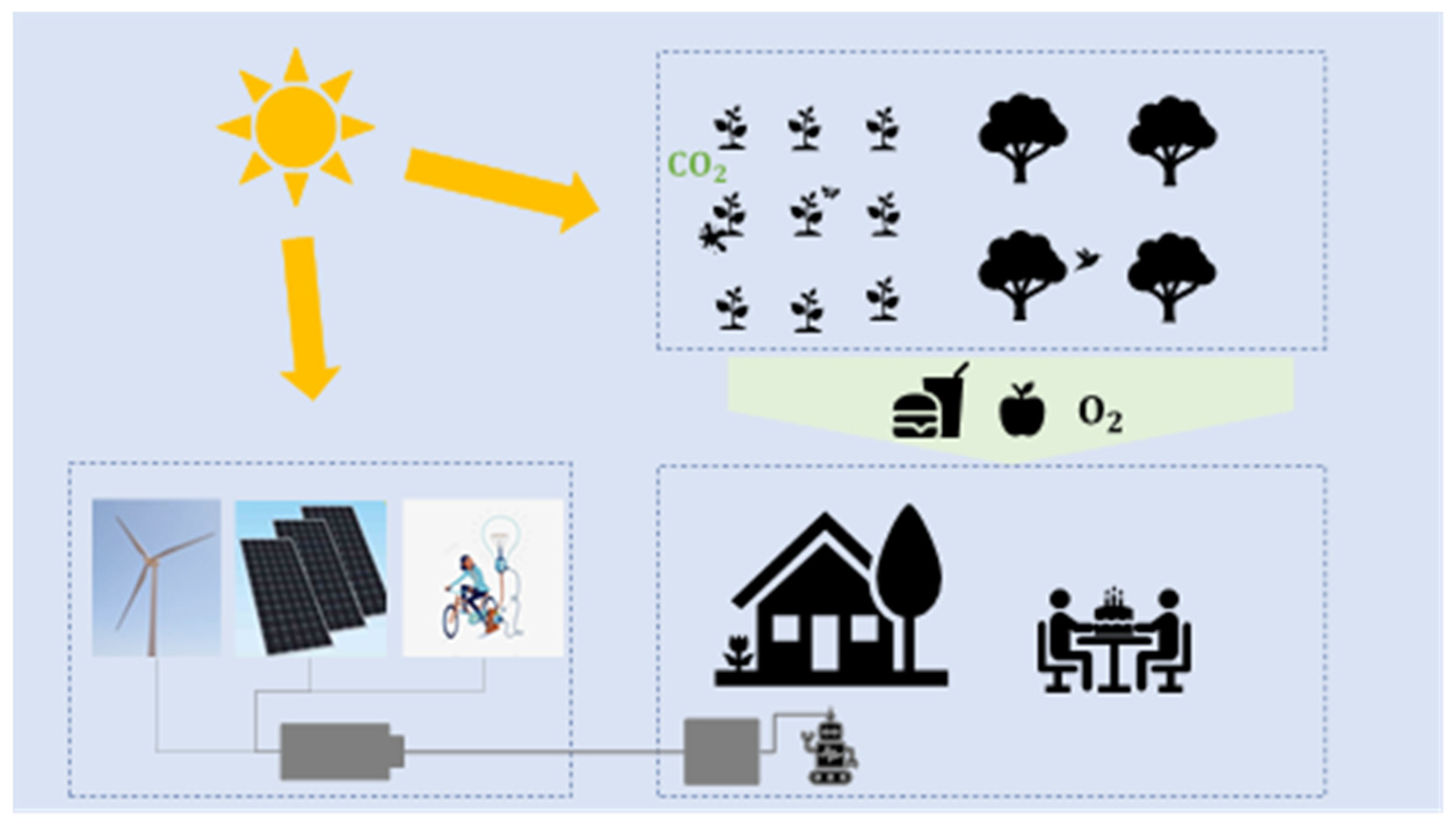

5.1.2. Environmentally friendly, no geographical restrictions

5.2. Challenges

5.2.1. Discontinuous human power generation

- Discontinuity of human activity due to physiological factors. Humans have limited physical strength, and sustained physical activity over a long period may lead to fatigue. As fatigue accumulates, a person's ability to generate electricity will gradually decrease, resulting in a drop in power output. For example, people may engage in strenuous activities for some time and then enter a state of rest or relaxation. This fluctuation in activity leads directly to discontinuities in power generation output [109,110]. For example, when people walk, since the direction of the force exerted by the human foot changes with time and gait, capturing the maximum energy throughout the walking cycle becomes challenging, which causes discontinuity in power generation [111]. In gym site, this problem may be solved through the shifts of workers.

- Mechanical efficiency. Even if a human can provide a constant and stable force, computerized devices that convert human labor into electricity may have erratic efficiency due to wear and tear, design flaws, or other reasons [112].

- Accelerated equipment losses. Unstable power output may cause large shocks to power conversion and transmission equipment, shortening the life of such equipment. Unbalanced voltages and currents can lead to overheating or overloading components inside the equipment, thus accelerating their wear and tear [113].

- Reduced power quality. Unstable power generation leads to fluctuations in voltage and frequency, and such volatility may cause damage to the equipment connected to that power source, especially some sophisticated equipment with high power quality requirements [114].

- Increased safety risk. Unstable electricity can lead to short circuits, fires, or other safety incidents in electrical equipment, thus increasing the safety risk of using human-powered electricity generation [115].

5.2.2. Less power generation (Low energy conversion efficiency)

5.2.3. Battery Energy Storage Issues

5.2.4. High cost

- Overall Retrofit Cost. The total cost of the retrofit is $20,000. Converting the gym to human-powered generation requires a relatively significant initial investment.

- Annual Savings. The yearly savings through workforce generation is $1,000. This means it will take 20 years to recover the investment without considering other factors.

- Present value savings over five years. Considering the time value of money (probably based on some discount rate), the current value of the savings over five years is $3,800.

- Actual cost of the retrofit. Considering the 5-year savings, the actual retrofit cost is $16,200.

6. Feasibility Study of Ecovillage System Engineering Concept and Development of Human Power Generation Prototypes

6.1. Introduction of the project

6.2. Research route

6.3. Application prospect and impact on the industries of the future

6.4. The role of eco-village system engineering in the basic research of the unified theory of large-scale complex engineering systems

7. Summary

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hasan, M.A.; Abubakar, I.R.; Rahman, S.M.; Aina, Y.A.; Islam Chowdhury, M.M.; Khondaker, A.N. The synergy between climate change policies and national development goals: Implications for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 249, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotzke, J.; Jakob, C.; Bony, S.; Dirmeyer, P.A.; O'Gorman, P.A.; Hawkins, E.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.; Nowicki, S.; Paulavets, K.; Seneviratne, S.I.; et al. Climate research must sharpen its view. Nat Clim Chang 2017, 7, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E. Climate change caused by human activities is happening and it already has major consequences. Journal of energy natural resources law 2018, 36, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, C. Entropy-TOPSIS Method to Study the Factors Affecting Light Pollution. In Proceedings of the Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology, 2023; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu, L.; Moll, F. Review of energy harvesting techniques and applications for microelectronics. In Proceedings of the VLSI Circuits and Systems II, 2005; pp. 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidur, R.; Islam, M.; Rahim, N.; Solangi, K. A review on global wind energy policy. Renewable sustainable energy reviews 2010, 14, 1744–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xie, G.; Zou, P. Energy Source and Energy Dissipation Mechanism of Coal and Gas Outburst Based on Microscope. Acta Microscopica 2020, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, R.; Raimi, D.; Aldana, G. Global energy outlook 2019: the next generation of energy. Resources for the Future 2019, 1, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ağbulut, Ü. Turkey’s electricity generation problem and nuclear energy policy. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, Environmental Effects 2019, 41, 2281–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, N.; Mouratiadou, I.; Luderer, G.; Baumstark, L.; Brecha, R.J.; Edenhofer, O.; Kriegler, E. Global fossil energy markets and climate change mitigation–an analysis with REMIND. Climatic change 2016, 136, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citaristi, I. The Development of International Organizations: A Chronology. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2022; Routledge: 2022; pp. 34–41.

- Rashid, F.; Joardder, M.U. Future options of electricity generation for sustainable development: Trends and prospects. Engineering Reports 2022, 4, e12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, K.; Østergaard, J. Battery energy storage technology for power systems—An overview. Electric power systems research 2009, 79, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, G. Runge-Kutta method designs wave energy maximum output power. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Applied Mathematics, Modelling, and Intelligent Computing (CAMMIC 2023), 2023; pp. 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, P. Temperatures of skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle and core in resting men in cold, comfortable and hot conditions. European journal of applied physiology occupational physiology 1992, 64, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, F.; Nozariasbmarz, A.; Vashaee, D.; Öztürk, M.C. Designing thermoelectric generators for self-powered wearable electronics. Energy Environmental Science Pollution Research 2016, 9, 2099–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taub, A.I. Automotive materials: Technology trends and challenges in the 21st century. MRS bulletin 2006, 31, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshinski, V.; Pozniakovska, N.; Mikluha, O.; Voitko, M. Modern education technologies: 21st century trends and challenges. In Proceedings of the SHS Web of Conferences, 2021; p. 03009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Ladkin, A. Trends affecting the convention industry in the 21st century. In Proceedings of the Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 2005; pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, Z.; Tang, B. Can digital skill protect against job displacement risk caused by artificial intelligence? Empirical evidence from 701 detailed occupations. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0277280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J. Artificial intelligence: Implications for the future of work. American journal of industrial medicine 2019, 62, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, H.J.; Daugherty, P.; Bianzino, N. The jobs that artificial intelligence will create. MIT Sloan Management Review 2017, 58, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruetzemacher, R.; Paradice, D.; Lee, K.B. Forecasting extreme labor displacement: A survey of AI practitioners. Technological Forecasting Social Change 2020, 161, 120323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhwar, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Wood, G.; Aguinis, H.; Bamber, G.J.; Beltran, J.R.; Boselie, P.; Lee Cooke, F.; Decker, S.; DeNisi, A. Human resource management in the age of generative artificial intelligence: Perspectives and research directions on ChatGPT. Human Resource Management Journal 2023, 33, 606–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-H.; Rust, R.; Maksimovic, V. The feeling economy: Managing in the next generation of artificial intelligence (AI). California Management Review 2019, 61, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, C. The future of radiology augmented with artificial intelligence: a strategy for success. European journal of radiology 2018, 102, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxley, P.; Evans, S.; Gately, C.; Webber, M.; Mears, A.; Pajak, S.; Kendall, T.; Medina, J.; Katona, C. Stress and pressures in mental health social work: The worker speaks. British Journal of Social Work 2005, 35, 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, C.-H.; Cao, X.; Zhong, R.Y.; Duan, X.; Li, P. Industrial Internet of Things-enabled monitoring and maintenance mechanism for fully mechanized mining equipment. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2022, 54, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, C.-Y.; Tsai, N.-C. Human powered MEMS-based energy harvest devices. Applied Energy 2012, 93, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lin, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Duan, J.; Hu, B.; Zhou, J. Fiber-based energy conversion devices for human-body energy harvesting. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 1902034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starner, T.; Paradiso, J.A. Human Generated Power for Mobile Electronics Ѓ. 2004.

- Kiely, J.; Morgan, D.; Rowe, D.; Humphrey, J. Low cost miniature thermoelectric generator. Electronics Letters 1991, 25, 2332–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaevitz, S.B.; Franz, A.J.; Jensen, K.F.; Schmidt, M.A. A combustion-based MEMS thermoelectric power generator. In Proceedings of the Transducers’ 01 Eurosensors XV: The 11th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors and Actuators, Munich, Germany, 10–14 June 2001; 2001; pp. 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Najafi, K.; Bernal, L.P.; Washabaugh, P.D. An integrated combustor-thermoelectric micro power generator. In Proceedings of the Transducers’ 01 Eurosensors XV: The 11th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors and Actuators, Munich, Germany, 10–14 June 2001; 2001; pp. 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proto, A.; Penhaker, M.; Conforto, S.; Schmid, M. Nanogenerators for human body energy harvesting. Trends in biotechnology 2017, 35, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamer, T.; Paradiso, J. Human generated power for mobile electronics Low Power Electronics Design. Low Power Electronics Design 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lukowicz, P. Kinetic energy powered computing-an experimental feasibility study. In Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 2003. Proceedings., 2003; pp. 22–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Song, J. Piezoelectric nanogenerators based on zinc oxide nanowire arrays. Science 2006, 312, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Qin, Y.; Dai, L.; Wang, Z.L. Power generation with laterally packaged piezoelectric fine wires. Nature nanotechnology 2009, 4, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Tran, V.H.; Wang, J.; Fuh, Y.-K.; Lin, L. Direct-write piezoelectric polymeric nanogenerator with high energy conversion efficiency. Nano letters 2010, 10, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.; Choi, M.Y.; Choi, W.M.; Shin, H.J.; Park, H.K.; Seo, J.S.; Park, J.; Yoon, S.M.; Chae, S.J.; Lee, Y.H. Fully rollable transparent nanogenerators based on graphene electrodes. Advanced Materials 2010, 22, 2187–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Lin, L. Progress in triboelectric nanogenerators as a new energy technology and self-powered sensors. Energy Environmental Science Pollution Research 2015, 8, 2250–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, F.; Dulio, S.; Patrini, M.; Guizzetti, G.; Mustarelli, P. Energy harvesting from human motion: materials and techniques. Chemical Society Reviews 2016, 45, 5455–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupenkin, T.; Taylor, J.A. Reverse electrowetting as a new approach to high-power energy harvesting. Nature communications 2011, 2, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pheasant, S. A Review of:“Human Walking”. By VT INMAN, HJ RALSTON and F. TODD.(Baltimore, London: Williams & Wilkins, 1981.)[Pp. 154.]. Ergonomics 1981, 24, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, W.D.; Katch, F.I.; Katch, V.L. Exercise physiology: nutrition, energy, and human performance; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2010.

- Yuan, J.; Zhu, R. A fully self-powered wearable monitoring system with systematically optimized flexible thermoelectric generator. Applied energy 2020, 271, 115250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starner, T. Human-powered wearable computing. IBM systems Journal 1996, 35, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Herrmann, S.D.; Meckes, N.; Bassett Jr, D.R.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Greer, J.L.; Vezina, J.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Leon, A.S. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Medicine science in sports exercise 2011, 43, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. Jama 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeneman, P.B.; Busch-Vishniac, I.J.; Wood, K.L. Feasibility of micro power supplies for MEMS. Journal of Microelectromechanical systems 1997, 6, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görge, G.; Kirstein, M.; Erbel, R. Microgenerators for energy autarkic pacemakers and defibrillators: Fact or fiction? Herz 2001, 26, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirtharajah, R.; Chandrakasan, A.P. Self-powered signal processing using vibration-based power generation. IEEE journal of solid-state circuits 1998, 33, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.A.; Epstein, A.H. An informal survey of power MEMS. In Proceedings of the The international symposium on micro-mechanical engineering, 2003; pp. 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Bo, L.; Li, Z. Recent progress in human body energy harvesting for smart bioelectronic system. Fundamental Research 2021, 1, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, J.S.; Ward, R.E.; Lacroix, J.; Hébert, P.C.; Barnes, M.A.; Bohn, D.J.; Dirks, P.B.; Doucette, S.; Fergusson, D.; Gottesman, R. Hypothermia therapy after traumatic brain injury in children. New England Journal of Medicine 2008, 358, 2447–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth. The range and variability of the blood flow in the human fingers and the vasomotor regulation of body temperature. American Heart Journal 1940, 19, 249–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G. Body temperature variability (Part 1): a review of the history of body temperature and its variability due to site selection, biological rhythms, fitness, and aging. Alternative medicine review 2006, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Q.; Liu, D.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, Z. Liquid concentration measurement based on laser scattering principle. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Optics and Image Processing (ICOIP 2023), 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckaba, C.E.; Hansen, L.W.; Downey, J.A.; Darling, R.C. Calculation of temperature distribution in the human body. AIChE Journal 1973, 19, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. The cytoskeleton and cell behavior. In Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition; Garland science: 2002.

- McNaught, A.D.; Wilkinson, A. Compendium of chemical terminology; Blackwell Science Oxford, 1997; Volume 1669. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L.D.; Bell, J.S.; Kearsley, M.; Pitaevskii, L.; Lifshitz, E.; Sykes, J. Electrodynamics of continuous media; elsevier: 2013; Volume 8.

- Enescu, D. Thermoelectric energy harvesting: basic principles and applications. Green energy advances 2019, 1, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, D. General principles and basic considerations. Thermoelectrics Handbook 2005.

- Watkins, C.; Shen, B.; Venkatasubramanian, R. Low-grade-heat energy harvesting using superlattice thermoelectrics for applications in implantable medical devices and sensors. In Proceedings of the ICT 2005. 24th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, 2005., 2005; pp. 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patowary, R.; Baruah, D.C. Thermoelectric conversion of waste heat from IC engine-driven vehicles: A review of its application, issues, and solutions. International journal of energy research 2018, 42, 2595–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, D.-W.; Zhao, W.-S.; You, B.; Liu, J.; Qian, C.; Xu, H.-B. Intelligent Design and Tuning Method for Embedded Thermoelectric Cooler (TEC) in 3-D Integrated Microsystems. IEEE Transactions on Components, Packaging and Manufacturing Technology 2023, 13, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitzler, A.; Tiersten, H.; Warner, A.; Berlincourt, D.; Couqin, G.; Welsh III, F. IEEE Standard on Piezoelectricity. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Inc., New York 1988.

- Yingyong, P.; Thainiramit, P.; Jayasvasti, S.; Thanach-Issarasak, N.; Isarakorn, D. Evaluation of harvesting energy from pedestrians using piezoelectric floor tile energy harvester. Sensors Actuators A: Physical 2021, 331, 113035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu, L.; Fonellosa, F.; Moll, F. Electrical characterization of a piezoelectric film-based power generator for autonomous wearable devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the XVIII Conference on Design of Circuits and Integrated Systems, Ciudad Real, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Al-Furjan, M.S.H.; Zou, J.; Liu, W. A review on heat and mechanical energy harvesting from human–Principles, prototypes and perspectives. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 82, 3582–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, J.; Granstrom, J.; Sodano, H. Energy harvesting through a backpack employing a mechanically amplified piezoelectric stack. Mechanical Systems Signal Processing 2008, 22, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelan, J.M.; Li, Q.; Naing, V.; Hoffer, J.A.; Weber, D.; Kuo, A.D. Biomechanical energy harvesting: generating electricity during walking with minimal user effort. Science 2008, 319, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rome, L. Backpack for harvesting electrical energy during walking and for minimizing shoulder strain. 2008.

- Zhu, G.; Peng, B.; Chen, J.; Jing, Q.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as a new energy technology: From fundamentals, devices, to applications. Nano Energy 2015, 14, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Wang, Z.L. Theoretical systems of triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2015, 14, 161–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.K.; Jeong, U. Material aspects of triboelectric energy generation and sensors. NPG Asia Materials 2020, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, R.; Kumar, C.; Mulvihill, D.M.; Pillai, S.C. Opportunities and Challenges in Triboelectric Nanogenerator (TENG) based Sustainable Energy Generation Technologies: A Mini-Review. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2022, 9, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Ding, Z.; Li, Z.; Zheng, H.; Fu, J.; Diao, C.; Zhang, X.; Tian, J.; Zi, Y. A fully-packaged ship-shaped hybrid nanogenerator for blue energy harvesting toward seawater self-desalination and self-powered positioning. Nano Energy 2019, 57, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Lin, Z.-H.; Su, Y.; Bai, P.; Wen, X.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting wind energy and as self-powered wind vector sensor system. ACS nano 2013, 7, 9461–9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.-R.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Wang, Z.L. Flexible triboelectric generator. Nano energy 2012, 1, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yu, A.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Jia, M.; Zhai, J.; Wang, Z.L. Large-scale fabrication of robust textile triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2020, 71, 104605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Dong, K.; Ye, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhai, S.; Cheng, R.; Liu, D.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.L. A breathable, biodegradable, antibacterial, and self-powered electronic skin based on all-nanofiber triboelectric nanogenerators. Science Advances 2020, 6, eaba9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugele, F.; Duits, M.; Van den Ende, D. Electrowetting: A versatile tool for drop manipulation, generation, and characterization. Advances in colloid interface science 2010, 161, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.-H.; Manakasettharn, S.; Taylor, J.A.; Krupenkin, T. Bubbler: a novel ultra-high power density energy harvesting method based on reverse electrowetting. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 16537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelrine, R.; Kornbluh, R.; Pei, Q.; Joseph, J. High-speed electrically actuated elastomers with strain greater than 100%. Science 2000, 287, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meninger, S.; Mur-Miranda, J.O.; Amirtharajah, R.; Chandrakasan, A.; Lang, J. Vibration-to-electric energy conversion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1999 international symposium on Low power electronics and design, 1999; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Roundy, S.; Wright, P.K.; Pister, K.S. Micro-electrostatic vibration-to-electricity converters. In Proceedings of the ASME international mechanical engineering congress and exposition; 2002; pp. 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lee, C.; Kotlanka, R.K.; Xie, J.; Lim, S.P. A MEMS rotary comb mechanism for harvesting the kinetic energy of planar vibrations. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2010, 20, 065017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, R.; Kabei, N.; Katayama, K.; Tsuboi, E.; Tsuchiya, K. Development of an electrostatic generator for a cardiac pacemaker that harnesses the ventricular wall motion. Journal of artificial organs 2002, 5, 0239–0245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, T.B.; Cygan, P.J.; Leung, F.C. Man portable power needs of the 21st century: I. Applications for the dismounted soldier. II. Enhanced capabilities through the use of hybrid power sources. Journal of Power Sources 2000, 91, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyers, W.L.; Coombe, H.S.; Hartman, A. Harvesting Energy with Hand-Crank Generators to Support Dismounted Soldier Missions. 2004.

- Jansen, A.J. Human Power empirically explored. 2011.

- Pham, H.; Bandaru, A.P.; Bellannagari, P.; Zaidi, S.; Viswanathan, V. Getting Fit in a Sustainable Way: Design and Optimization of a Low-Cost Regenerative Exercise Bicycle. Designs 2022, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, T. These Exercise Machines Turn Your Sweat Into Electricity. IEEE Spectrum 2011, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.E.; Bhumi, S.; Monika, R. Real Time Battery Charging System by Human Walking. International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering Technology 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilian, B.; Behdad, S.; Wang, B. The evolution and future of manufacturing: A review. Journal of manufacturing systems 2016, 39, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negahban, A.; Smith, J.S. Simulation for manufacturing system design and operation: Literature review and analysis. Journal of manufacturing systems 2014, 33, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M.; Falbe, C.M.; McKinley, W.; Tracy, P.K. Technology and organization in manufacturing. Administrative science quarterly 1976, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, J.S. Economies of scale, concentration, and the condition of entry in twenty manufacturing industries. The American Economic Review 1954, 44, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Painuly, J.P. Diffusion of renewable energy technologies—barriers and stakeholders’ perspectives. Renewable energy 2004, 29, 1431–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, J.; Li, R.; Jiang, X.T. Exploring the role of nuclear energy in the energy transition: A comparative perspective of the effects of coal, oil, natural gas, renewable energy, and nuclear power on economic growth and carbon emissions. Environment Research 2023, 221, 115290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, L.M.; Witter, R.Z.; Newman, L.S.; Adgate, J.L. Human health risk assessment of air emissions from development of unconventional natural gas resources. Science of the Total Environment 2012, 424, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saidur, R.; Rahim, N.A.; Islam, M.R.; Solangi, K.H. Environmental impact of wind energy. Renewable sustainable energy reviews 2011, 15, 2423–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhang, Y. Effects of solar photovoltaic technology on the environment in China. Environmental Science Pollution Research 2017, 24, 22133–22142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.M.; Arey, J.S.; Seewald, J.S.; Sylva, S.P.; Lemkau, K.L.; Nelson, R.K.; Carmichael, C.A.; McIntyre, C.P.; Fenwick, J.; Ventura, G.T. Composition and fate of gas and oil released to the water column during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 20229–20234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Q.; Lan, P.; Looney, C. A probabilistic framework for modeling and real-time monitoring human fatigue. IEEE Transactions on systems, man,cybernetics-Part A: Systems humans 2006, 36, 862–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vøllestad, N.K. Measurement of human muscle fatigue. Journal of neuroscience methods 1997, 74, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanchi, V.; Papić, V.; Cecić, M. Quantitative human gait analysis. Simulation Practice Theory 2000, 8, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rong, K.; Lu, R. Energy loss and mechanical efficiency forecasting model for aero-engine bevel gear power transmission. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2022, 231, 107569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derafshian Maram, M.; Amjady, N. Event-based remedial action scheme against super-component contingencies to avert frequency and voltage instabilities. IET Generation, Transmission Distribution 2014, 8, 1591–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Myrzik, J.; Kling, W. Consequences of poor power quality-an overview. In Proceedings of the 2007 42nd International Universities Power Engineering Conference, 2007; pp. 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, L.J.; Ladha, A.; Kolhe, C.; Patel, A.; Summers, J.S.; Rao, S.R.; Das, P.; Mohammady, M.; Conant, E.; Ramanathan, N. Poor power quality is a major barrier to providing optimal care in special neonatal care units (SNCU) in Central India. Gates Open Research 2022, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Hu, H.; He, S. Modeling and experimental investigation of an impact-driven piezoelectric energy harvester from human motion. Smart Materials Structures 2013, 22, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Zhang, T.; Xu, L. A review of power scavenging from vibration sources based on the piezoelectric effect. Mech. Sci. Tech. Aerosp. Eng 2010, 29, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.P.; Jain, S. Person identification based on gait using dynamic body parameters. In Proceedings of the Trendz in information sciences & computing (TISC2010), 2010; pp. 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, Z.; Mei, X. Overview of human walking induced energy harvesting technologies and its possibility for walking robotics. Energies 2019, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacín, M.R.; de Guibert, A. Why do batteries fail? Science 2016, 351, 1253292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.K.; Peng, H.; Liu, G.; McIlwrath, K.; Zhang, X.F.; Huggins, R.A.; Cui, Y. High-performance lithium battery anodes using silicon nanowires. Nature nanotechnology 2008, 3, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, M.; Liao, W.-H. On the energy storage devices in piezoelectric energy harvesting. In Proceedings of the Smart Structures and Materials 2006: Damping and Isolation, 2006; pp. 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Ding, S.; Fan, B.; Li, P.Y.; Yang, H. Development of a novel compact hydraulic power unit for the exoskeleton robot. Mechatronics 2016, 38, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, M.N.; Lau, K.; Agogino, A.M. Human power generation in fitness facilities. In Proceedings of the Energy Sustainability, 2010; pp. 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.C.; Li, R.; Pan, L.L. A Comparison of New General System Theory Philosophy With Einstein and Bohr. Philosophy 2023, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W. C. On the philosophical ontology for a general system theory. Philosophy 2021, 11, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Activity | Output / W | Activity | Output / W |

|---|---|---|---|

| Walking | 315 | Mopping | 225 |

| Jogging | 630 | Cooking | 225 |

| Running | 990 | Making bed | 297 |

| Bicycling | 675 | Rotate handle | 60 |

| Home sweeping | 270 | arm motion(joints rotation) | 28 |

| chemical compound | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1275 | 0 | -393.5 | -285.8 |

| chemical substance | Formula | energy generation (kJ/mol) | energy generation (kcal/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 2,809 | 3.75 | |

| Lactic acid | 1,330 | 3.33 | |

| Water | 0 | 0 |

| Industry | Manufacturing | Installation | Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detailed work |

|

|

|

| Research and Development | Training and Education | Logistics | Sales and Marketing |

|

|

|

|

| Total Cost of Retrofit | $20,000 |

| Annual Savings | $1,000 |

| Present Value of Saving after 5 Years | $3,800 |

| True Cost of Retrofit | $16,200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).