Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

03 November 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

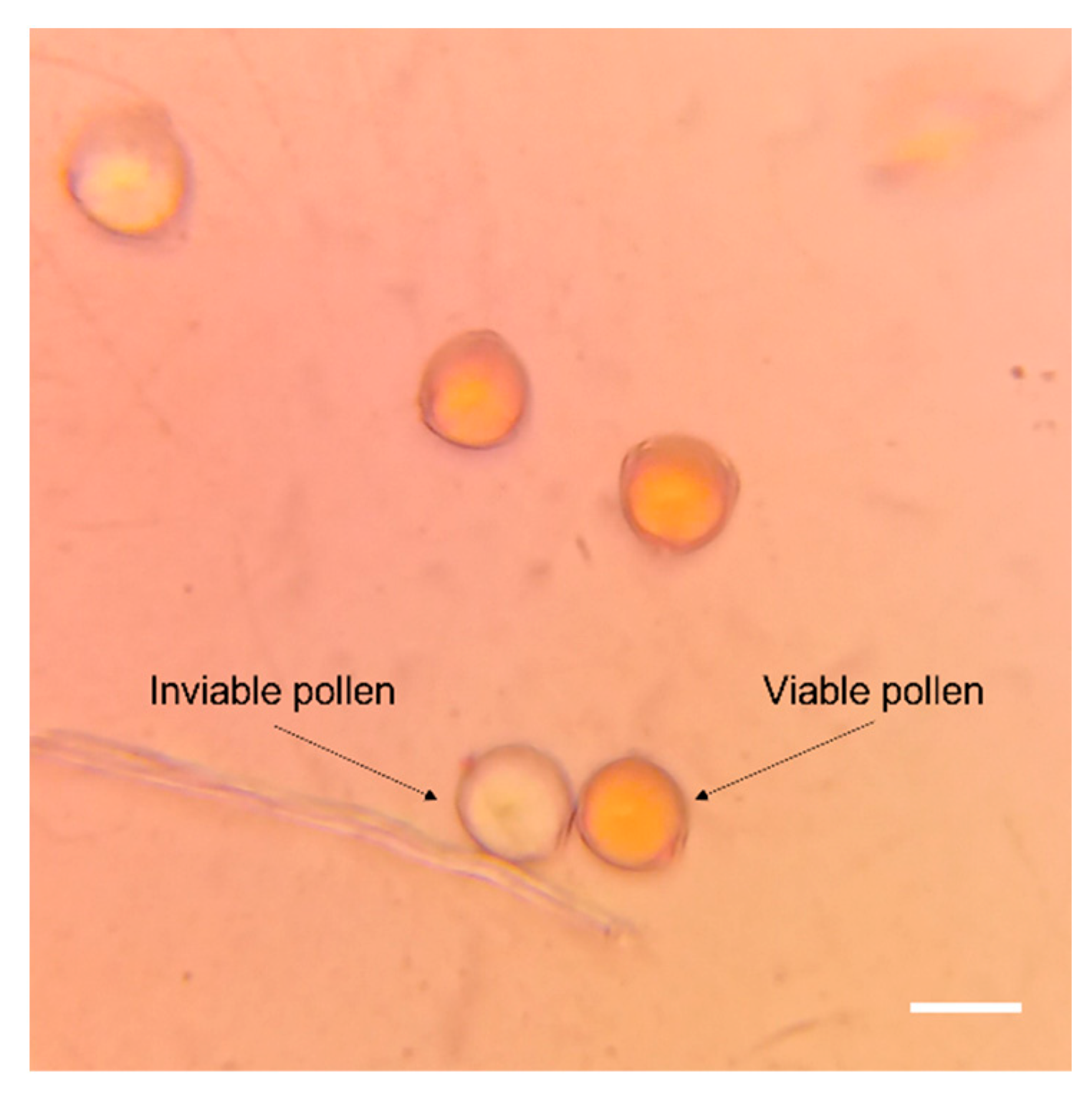

2.2. Pollen Viability Assessment

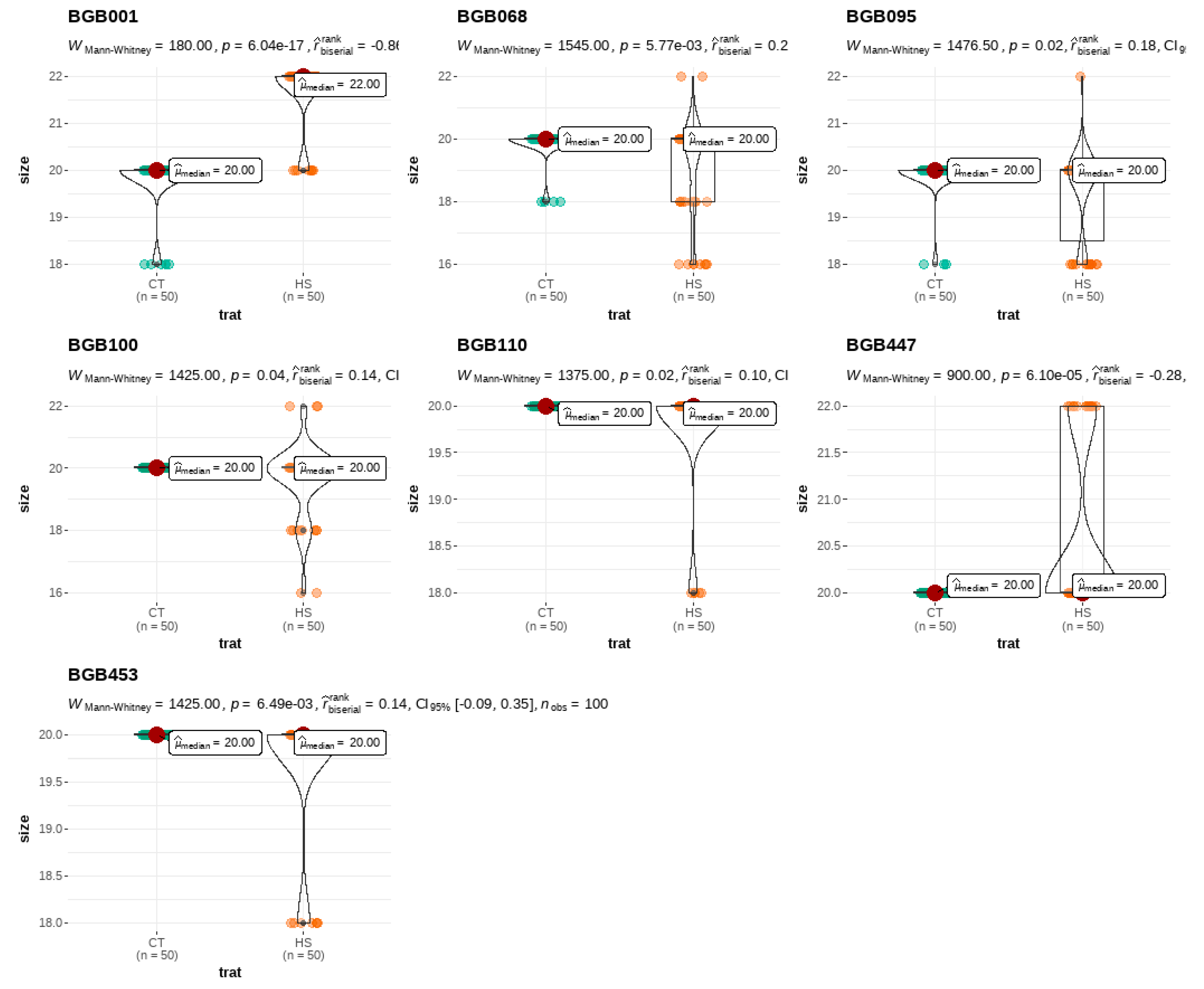

2.3. Pollen Size

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Pollen Viability-Based Heat Susceptibility Index (HSIpv)

2.4.2. Genetic Parameters

2.4.3. Heritability

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Variance

3.2. Pollen Viability-Based Heat Susceptibility Index (HSIpv)

3.3. Heritability for Pollen Viability

3.4. Pollen Size

3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts Of Interest

References

- Li, D.; Lu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Pan, J.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, G.; Shang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, C. 2022. The multi-omics basis of potato heterosis. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2022, 64:3, 671-687. :3.

- Malagamba, P. Potato production from true seed in tropical climates. HortScience 1988, 23:3, 495-500. :3.

- Bloomfield, J.A.; Rose, T.J.; King, G.J. Sustainable harvest: managing plasticity for resilient crops. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2014, 12, 517–533. [CrossRef]

- IPCC: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H. O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; Pirani, A.; Moufouma-Okia, W.; Péan, C.; Pidcock, R.; Connors, S.; Matthews, J. B. R.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gomis, M. I.; Lonnoy, E.; Maycock, T.; Tignor, M.; Waterfield, T. (eds.)]. 2018 In Press.

- Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adler, C.; Aldunce, P.; Ibrahim, Z.Z. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland 2022.

- Jarvis, A.; Lane, A.; Hijmans, R.J. The effect of climate change on crop wild relatives. Agriculture, Ecosystem and Environment 2008, 126, 13–23.

- Vincent, H.; Amri, A.; Castañeda-Álvarez, N.P.; Dempewolf, H.; Dulloo, E.; Guarino, L.; Hole, D.; Mba, C.; Toledo, A.; Maxted, N. Modeling of crop wild relative species identifies areas globally for in situ conservation. Communications Biology 2019, 2:1, 1-8. :1.

- Silva, G.O.; Lopes, C.A. Sistema de produção da Batata. Embrapa, Brasília 2016, 2.

- Stokstad, E. The new potato. Science 2019, 363:6427, 574-577.

- Hardigan, M.A.; Laimbeer, F.P.E; Newron, L.; Crisovan, E.; Hamilton, J.P.; Vaillancourt, B.; Wiegert-Rininger, K.; Wood, J.C.; Douches, D.S.; Farré, E.M.; Veilleux, R.E.; Nuell, C.R. Genome diversity of tuber-bearing Solanum uncovers complex evolutionary history and targets of domestication in the cultivated potato. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017, 114:46, 9999–10008.

- Spooner, D.M.; Ghislain, M.; Simon, R.; Jansky, S.H.; Gavrilenko, T. Systematics, diversity, genetics, and evolution of wild and cultivated potatoes. Botanical Review 2014, 80, 283–383.

- Hawkes, J.G.; Hjerting, J.P. The potatoes of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. A biosystematics study. Oxford University Press, London 1969, pp. 525.

- Hijmans, R.J.; Spooner, D.M. Geographic distribution of wild potato species. American Journal of Botany 2001, 88, 2101–2112.

- Dempewolf, H.; Baute, G.; Anderson, J.; Kilian, B.; Smith, C.; Guarino, L. Past and future use of wild relatives in crop breeding. Crop Science 2017, 57:3, 1070-1082. [CrossRef]

- Warschefsky, E.; Penmetsa, R.V.; Cook, D.R.; Von Wettberg, E.J. Back to the wilds: tapping evolutionary adaptations for resilient crops through systematic hybridization with crop wild relatives. American journal of Botany 2014, 101:10, 1791-1800. [CrossRef]

- Jansky, S. Overcoming hybridization barriers in potato. Plant Breeding 2006, 125:1, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Bethke, P.C.; Halterman, D.A.; Jansky, S. Are we getting better at using wild potato species in light of new tools?. Crop Science 2017, 57:3, 1241-1258.

- Hawkes, J.G. Significance of wild species and primitive forms for potato breeding. <italic>Euphytica</italic> <bold>1958</bold>, <italic>7:3</italic>. :3.

- Correll, D. The potato and its wild relatives. Texas Research Foundation, Renner, USA 1962, pp. 606.

- Lindhout, P.; Meijer, D.; Schotte, T.; Hutten, R.C.; Visser, R.G.; van Eck, H.J. Towards F1 hybrid seed potato breeding. Potato Research 2011, 54:4, 301-312. :4.

- Jansky, S.H.; Charkowski, A.O.; Douches, D.S.; Gusmini, G.; Richael, C.; Bethke, P.C.; Spooner, D.M.; Novy, R.G.; de Jong, H.; de Jong, W.S.; Bamberg, J.B.; Thompson, A.L.; Bizimungu, B.; Holm, D.G.; Brown, C.R.; Haynes, K.G.; Sathuvalli, V.R.; Veilleux, R.E.; Miller, J.C.; Bradeen, J.M.; Jiang, J. Reinventing potato as a diploid inbred line–based crop. Crop Science 2016, 56, 1412–1422.

- Bradshaw, J.E. Breeding diploid F1 hybrid potatoes for propagation from botanical seed (TPS): comparisons with theory and other crops. Plants 2022,11:9, 1121. [CrossRef]

- Endelman, J.B. Jansky, S.H. Genetic mapping with an inbred line-derived F2 population in potato. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2016, 129, 935-943. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, D.; Viquez-Zamora, M.; Van Eck, H.J.; Hutten, R.C.B.; Su, Y.; Rothengatter, R.; Visser, R.G.F.; Lindhout, W.H.; Van Heusden, A.W. QTL mapping in diploid potato by using selfed progenies of the cross S. tuberosum× S. chacoense. Euphytica 2018, 214, 1-18.

- Song, L.; Endelman, J.B. Using haplotype and QTL analysis to fix favorable alleles in diploid potato breeding. The Plant Genome 2023, e20339. [CrossRef]

- De Vries, M.; ter Maat, M.; Lindhout, P. The potential of hybrid potato for East-Africa. Open Agriculture 2016, 1:1, 151-156. [CrossRef]

- Bethke, P.C.; Halterman, D.A.; Francis, D.M.; Jiang, J.; Douches, D.S.; Charkowski, A.O.; Parsons, J. Diploid potatoes as a catalyst for change in the potato industry. American Journal of Potato Research 2022, 99:5-6, 337-357.

- Bethke, P.C.; Halterman, D.A.; Jansky, S.H. Potato germplasm enhancement enters the genomics era. Agronomy 2019, 9:10, 575.

- Watson, A.; Ghosh, S.; Williams, M.J.; Cuddy, W.S.; Simmonds, J.; Rey, M.D.; Hatta, M.A.M.; Hinchliffe, A.; Steed, A.; Reynolds, D.; Adamsky, N.M.; Breakspear, A.; Korolev, A.; Rayuner, T.; Dixon, L.E.; Riaz, A.; Martin, W.; Ryan, M.; Edward, D.; Batley, J.; Raman, H.; Carter, J.; Rogers, C.; Domoney, C.; Moore, G.; Harwood, W.; Nicholson, P.; Dieters, M.J.; DeLacy, I.H.; Zhou, J.; Uauy, C.; Boden, S.A.; Park, R.F.; Wulff, B.B.H.; Hickey, L.T. Speed breeding is a powerful tool to accelerate crop research and breeding. Nature Plants 2018, 4:1, 23-29.

- Schindfessel, C.; De Storme, N.; Trinh, H.K.;Geelen, D. Asynapsis and meiotic restitution in tomato male meiosis induced by heat stress. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Omidi, M.; Siahpoosh, M.R.; Mamghani, R.; Modarresi, M. The influence of terminal heat stress on meiosis abnormalities in pollen mother cells of wheat. Cytologia 2014, 79:1, 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Seetharam, K.; Zaidi, P.H.; Dinesh, A.; Vinayan, M.T.; Nath, U.K. Dissecting heat stress tolerance in tropical maize (Zea mays L.). Field Crops Research 2017, 204, 110-119. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Cheng, X.; Kong, B.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Sang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, P. Heat shock-induced failure of meiosis I to meiosis II transition leads to 2n pollen formation in a woody plant. Plant Physiology 2022, 189:4, 2110-2127. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.P. Differential staining of aborted and non-aborted pollen. Stain Technology 1969, 44, 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Marks, G.E. An aceto-carmine glycerol jelly for use in pollen-fertility counts. Stain Technology 1954, 29:5, 277-277.

- Ordoñez, B.; Orrillo, M.; Bonierbale, M.W. Technical manual potato reproductive and cytological biology. International Potato Center (CIP) 2017, pp.69.

- Ferreira, E.B.; Cavalcanti, P.P.; Nogueira, D.A. ExpDes.pt: Experimental Designs package (Portuguese). R package version 1.1.2., 2021. Available online: https://cran.utstat.utoronto.ca/web/packages/ExpDes.pt/ExpDes.pt.pdf (accessed on 01 August 2023).

- Rstudio Team Rstudio: Integrated Development for R. Rstudio, PBC, Boston, MA, 2020. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/. (accessed on 01 August 2023).

- Fischer, R.A.; Maurer, R. Drought resistance in spring wheat cultivars. I. Grain yield responses. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 1978, 29:5, 897-912.

- Khan, I.; Wu, J.; Sajjad, M. Pollen viability-based heat susceptibility index (HSIpv): A useful selection criterion for heat-tolerant genotypes in wheat. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1064569.

- Burton, G.W. Quantitative inheritance in grasses. In Proceedings of the 6th International Grassland Congress, State College, PA, USA 1952, 17–23, pp–277. [Google Scholar]

- Allard, R.W. Principles of plant breeding. John Willey and Sons. Inc. New York 1960, pp. 485.

- Robinson, H.F.; Cornstock, R.E.; Harvey, P.H. Estimates of heritability and degree of dominance in corn. Agronomy Journal 1949, 41, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.W.; Robinson, H.F.; Comstock, R.E. Estimation of genetic and environmental variability in soybean. Agronomy Journal 1955, 47, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, R. Breeding for quantitative traits in plants. 2nd ed. Woodbury: Stemma Press 2010, pp. 390.

- Begcy, K.; Nosenko, T.; Zhou, L.Z.; Fragner, L.; Weckwerth, W.; Dresselhaus, T. Male sterility in maize after transient heat stress during the tetrad stage of pollen development. Plant Physiology 2019, 181:2, 683-700.

- Ullah, A.; Nadeem, F.; Nawaz, A.; Siddique, K.H.; Farooq, M. Heat stress effects on the reproductive physiology and yield of wheat. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2022, 208:1, 1-17.

- Kumar, N.; Kumar, N.; Shukla, A.; Shankhdhar, S.C.; Shankhdhar, D. Impact of terminal heat stress on pollen viability and yield attributes of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Cereal Research Communications 2015, 43:4, 616-626.

- Paupière, M.J.; Müller, F.; Li, H.; Rieu, I.; Tikunov, Y.M.; Visser, R.G.; Bovy, A.G. Untargeted metabolomic analysis of tomato pollen development and heat stress response. Plant Reproduction 2017, 30:2, 81-94.

- Bamberg, J.B. Screening potato (Solanum) species for male fertility under heat stress. American Potato Journal 1995, 72, 23-33.

- Allard, R.W.; Hansche, P.E. Some parameters of population variability and their implications in plant breeding. Advances in Agronomy 1964, 16, 281–325. [Google Scholar]

- Nagalakshmi, R.M.; Ravikesavan, R.; Paranidharan, V.; Manivannan, N.; Firoz, H.; Vignesh, M.; Senthil, N. Genetic variability, heritability and genetic advance studies in backcross populations of maize (Zea mays L. ). Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2018, 9, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.N.; Nallathambi, G.; Senthil, N.; Tamilarasi, P.M. Genetic divergence (Zea mays L. ) Analysis in indigenous maize. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2010, 1, 1241–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Schoper, J.B.; Lambert, R.J.; Vasilas, B.L. Maize pollen viability and ear receptivity under water and high temperature stress 1. Crop Science 1986, 26:5, 1029-1033.

- Panthee, D.R.; Kressin, J.P.; Piotrowski, A. Heritability of flower number and fruit set under heat stress in tomato. HortScience 2018, 53:9, 1294-1299.

- Hazra, P.; Ansary, S.H. , Genetics of heat tolerance for floral and fruit set to high temperature stress in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). SABRAO Journal of Breeding & Genetics 2008, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, R.K.; Kumar, S. Variability, Heritability and Genetic Advance in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Genotypes. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 2023, 35:4, 138-144.

- Visscher, P.; Hill, W.; Wray, N. Heritability in the genomics era — concepts and misconceptions. Nature Review Genetics 2008, 9, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petr, F.C.; Frey, K.J. Genotypic Correlations, Dominance, and Heritability of Quantitative Characters in Oats 1. Crop Science 1966, 6:3, 259-262.

- Chatara, T.; Musvosvi, C.; Houdegbe, A.C.; Sibiya, J. Variance Components, Correlation and Path Coefficient Analysis of Morpho-Physiological and Yield Related Traits in Spider Plant (Gynandropsis gynandra (L.) Briq.) under Water-Stress Conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13:3, 752.

- Lal, N.; Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Pandey, S. Assessment of Variability, Correlation and Path Analysis for the Selection of Elite Clones in Litchi Based on Certain Traits. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2023, 65, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olakojo, S.A.; Olaoye, G. Correlation and heritability estimates of maize agronomic traits for yield improvement and Striga asiatica (L.) kuntze tolerance. African Journal of Plant Science 2011, 5, 365–369. [Google Scholar]

- Aminu, D.; Izge, A.U. Heritability and correlation estimates in maize (Zea mays L.) Under drought conditions in northern guinea and sudan savannas of Nigeria. World Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2012, 8, 598–602. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, M.G.; Sarker, U.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Banik, B.R. Genetic variability of yield and its contributing characters on CIMMYT maize inbreds under drought stress. Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Research 2015, 39, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, W.G.; Goddard, M.E. Visscher, P.M. Data and theory point to mainly additive genetic variance for complex traits. PloS Genetics 2008, 4:2, e1000008.

- Prakash, R.; Ravikesavan, R.; Vinodhana, N.K.; Senthil, A. Genetic variability, character association and path analysis for yield and yield component traits in maize (Zea mays L. ). Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2019, 10, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakara, B.N.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Wani, S.P.; Gowda, C.L. Biology and genetic improvement of Jatropha curcas L.: a review. Applied Energy 2010, 87:3, 732-742.

- Kalloo, G. Genetic improvement of tomato. Springer Science & Business Media 2012, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Dane, F.; Hunter, A.G.; Chambliss, O. L. Fruit set, pollen fertility, and combining ability of selected tomato genotypes under high-temperature field conditions. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 1991, 116:5, 906-910.

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.; Roychowdhury, R.; Fujita, M. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14:5, 9643-9684.

- Paupière, M.J.; Van Heusden, A.W.; Bovy, A.G. The metabolic basis of pollen hermos-tolerance: perspectives for breeding. Metabolites 2014, 4:4, 889-920.

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Jones, A.; Rose, R.J.; Song, Y. Heat stress in legume seed setting: effects, causes, and future prospects. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, S.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Welti, R. Alterations in wheat pollen lipidome during high day and night temperature stress. Plant, Cell & Environment 2018, 41, 1749–1761. [Google Scholar]

- Djanaguiraman, M.; Perumal, R.; Ciampitti, I.A.; Gupta, S.K.; Prasad, P.V.V. Quantifying pearl millet response to high temperature stress: thresholds, sensitive stages, genetic variability and relative sensitivity of pollen and pistil. Plant, Cell & Environment 2018, 41, 993–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti, V.; Celebrin, D.; Napoli, N.; Ghelli, R.; Brunetti, P.; Costantino, P.; Cardarelli, M. An auxin maximum in the middle layer controls stamen development and pollen maturation in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist 2013,1194–1207.

- Araki, T. Transition from vegetative to reproductive phase. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2001, 4, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümel, M.; Dally, N.; Jung, C. Flowering time regulation in crops—what did we learn from Arabidopsis? Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2015, 32, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohani, N.; Singh, M.B.; Bhalla, P.L. High temperature susceptibility of sexual reproduction in crop plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 71, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiqing, S.; Somayanda, I.; Sebastian, S.V.; Singhm, K.; Gill, K.; Prasad, P.V.; Jagadish, S.V. Heat stress during flowering affects time of day of flowering, seed set, and grain quality in spring wheat. Crop Science 2018, 58:1, 380–392.

- Chaturvedi, P.; Wiese, A.J.; Ghatak, A.; Zaveska D.L.; Weckwerth, W.; Honys, D. Heat stress response mechanisms in pollen development. New Phytologist 2021, 231:2, 571-585.

- Delph, L.F.; Johannsson, M.H.; Stephenson, A.G. How environmental factors affect pollen performance ecological and evolutionary perspectives. Ecology 1997, 78, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djanaguiraman, M.; Prasad, P.V.; Boyle, D.; Schapaugh, W. Soybean pollen anatomy, viability and pod set under high temperature stress. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2013, 199, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djanaguiraman, M.; Prasad, P.V.; Murugan, M.; Perumal, R.; Reddy, U.K. Physiological differences among sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) genotypes under high temperature stress. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2014, 100, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M.; Tsuchiya, T.; Hamada, K.; Kawamura, S.; Yano, K.; Ohshima, M.; Higashitani, A.; Watanabe, M.; Kawagishi-Kobayashi, M. High temperatures cause male sterility in rice plants with transcriptional alterations during pollen development. Plant & Cell Physiology 2009, 50, 1911–1922. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, M.; Chourey, P.S.; Boote, K.J.; Allen, L.H.Jr. Short-term high temperature growth conditions during vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition irreversibly compromise cell wall invertase-mediated sucrose catalysis and microspore meiosis in grain sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). Journal of Plant Physiology 2010, 167, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pécrix, Y.; Rallo, G.; Folzer, H.; Cigna, M.; Gudin, S.; Le Bris, M. Polyploidization mechanisms: temperature environment can induce diploid gamete formation in Rosa sp. Journal of Experimental Botany 2011, 62, 3587–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, M.K.; Rauf, S.; Khurshid, M.; Iqbal, S.; Bhat, J.A.; Farzand, A.; Riaz, A.; Xing, G.; Gai, J.,Pollen Viability an Index of Abiotic Stresses Tolerance and Methods for the Improved Pollen Viability. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research 2019,32:4, 609-624.

| Genesys code | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local code | Species | Origin | Lat | Lon | |

| BGB447 | BRA00183755-8 | S. malmeanum | Porto Lucena, RS, Brazil | -27.8561 | -55.0164 |

| BGB100 | BRA 00167017-3 | S. chacoense | Catamarca, Argentina | -41 | -71.5 |

| BGB110 | BRA 00167028-0 | S. chacoense | Unknown | - | - |

| BGB106 | BRA 00167023-1 | S. chacoense | Unknown | - | - |

| BGB095 | BRA 00167447-2 | S. chacoense | Cordoba, Argentina | -31.13333 | -64.48333 |

| BRSIPR-BEL | BRA00167251-8 | S. tuberosum | Brazil | - | - |

| BGB001 | BRA00167007-4 | S. commersonii | Ijuí, RS, Brazil | -28.388 | -53.915 |

| BGB453 | BRA00183760-8 | S. commersonii | Herval, RS, Brazil | -32.0236 | -53.3956 |

| BGB068 | BRA00167420-9 | S. commersonii | São Gabriel, RS, Brazil | -30.336 | -54.32 |

| Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F-value | Pr (>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block | 1 | 82.3 | 5 | 2.450 | 0.141 |

| Genotype | 6 | 4278.7 | 4 | 21.228 | 0.000* |

| Temperature | 1 | 869.1 | 6 | 25.872 | 0.000* |

| Genotype×Temperature | 6 | 340.9 | 3 | 1.532 | 0.200 |

| Residue | 13 | 436.7 | 2 | ||

| Total | 27 | 6007.7 | 1 | ||

| CV (%) | 7.13 |

| Components | Pollen viability | |

|---|---|---|

| VP | phenotypic variance | 210.29 |

| VG | genotypic variance | 164.10 |

| Ve | residual variance | 35.66 |

| VG×T | genotype × treatment interaction variance | 10.54 |

| H2B | broad sense heritability (%) | 78 |

| AG | accuracy in genotypic selection | 0.96 |

| PCV | phenotypic coefficient of variation | 17.84 |

| GCV | genotypic coefficient of variation | 15.76 |

| GG | genetic gain % | 28.68 |

| GA | Genetic advance | 23.30 |

| ∑ | General average | 81.29 |

| Species | Temperature treatment | Heritability (h2) % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Genesys code | CT | HS | HSIpv | Score | ||

| BGB447 | BRA 00183755-8 | S. malmeanum | 100 a* | 91.5 abc | 0.66 | Tolerant | 91.32 |

| BGB100 | BRA 00167017-3 | S. chacoense | 98.5 a | 94.0 ab | 0.36 | Tolerant | 88.35 |

| BGB110 | BRA 00167028-0 | S. chacoense | 96.0 a | 83.5 abcd | 1.01 | Tolerant | 88.56 |

| BGB095 | BRA 00167447-2 | S. chacoense | 89.5 abcd | 71.5 bcde | 1.57 | Moderaltely tolerant | 83.16 |

| BGB001 | BRA 00167007-4 | S. commersonii | 86.5 abcd | 65.5 de | 1.89 | Moderaltely tolerant | 58.82 |

| BGB453 | BRA 00183760-8 | S. commersonii | 69.0 b | 69.5 bc | 0.06 | Tolerant | 83.82 |

| BGB068 | BRA 00167420-9 | S. commersonii | 68.5 cde | 54.5 e | 1.59 | Moderaltely tolerant | 87.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).