2. Definitions of AR and review of theoretical perspectives

Analogies vary according to the degree of similarity between visuospatial characteristics of objects or related semantic concepts. Some analogies are more obvious if they contain large amounts of similar attributes as opposed to others which have very few similar attributes and therefore are more obtuse and harder to discern any embedded similarity. There is a gradation of analogical correspondence and according to Goswami (1992) people of all ages can identify degrees of pattern similarity through analogical reasoning. Discerning new conceptual relational patterns is an essential cognitive process for making sense of new phenomena which have multifaceted applications in academic learning, e.g., maths, science, artificial intelligence, languages, engineering, medicine, etc. (Trey & Khan, 2008; DeWolf, Bassok, & Holyoak, 2015; Ehri, Satlow, & Gaskins, 2009).

AR is considered an important cognitive process affecting multiple cognitive processes, and therefore neuroscientists are interested in understanding how the brain processes analogical relational reasoning, from a structural and functional perspective, aiming to improve its application for educational, occupational and health related outcomes (Dumas, Alexander, & Grossnickle, 2013; Krawczyk, 2012; Kumar, Cervesato, & Gonzalez, 2014). For example, targeted training of young people can improve AR skills to detect relational visuospatial patterns and understanding of ideational semantic correspondence in abstract concepts encountered in many educational and occupational problem-solving activities (Guerra-Carrillo, & Bunge, 2018).

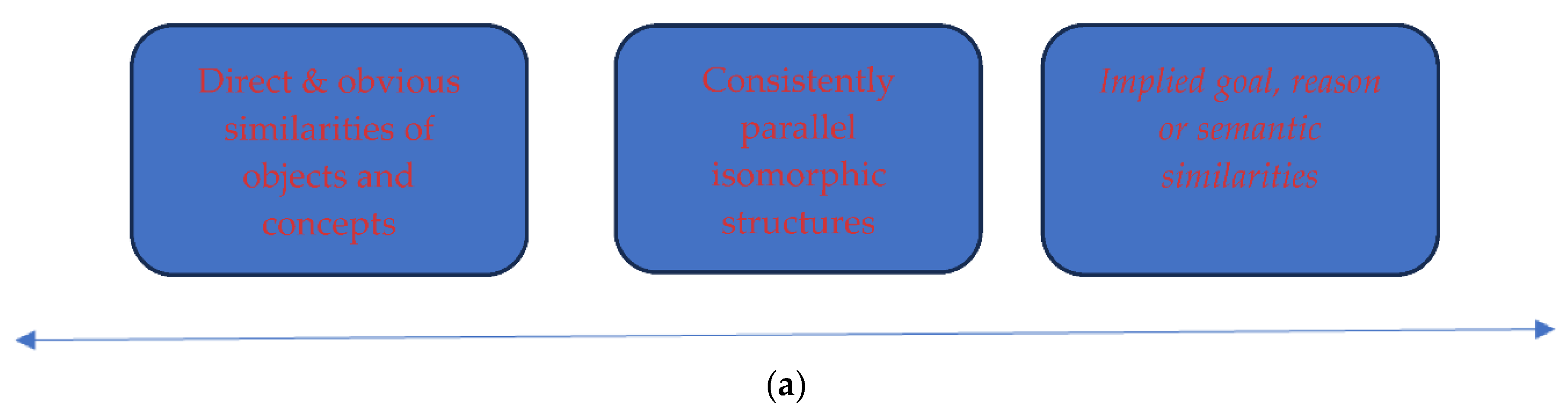

There are two competing theories of AR, the structure-mapping theory by Gentner (1983) and the multiconstraint theory by Holyoak & Thagard (1997). According to Gentner’s (1983) theory of structure-mapping, two seemingly unrelated elements are cognitively mapped out to identify differences and similarities. Analogical reasoning is based on two implicit constraints, structural consistency of direct correspondence for each element between two apparently similar phenomena or objects; and systematic comparison of the corresponding conceptual relations which have varying degrees of similarity (Gentner, & Markman, 1997). AR enables the extrapolation of logically coherent semantic inferences based on degrees of similarity, rather than irrelevant comparisons of haphazard elements without any logical similarities. Structure-mapping theory provides a framework for delineating different kinds of similarities: relational similarity (i.e., conceptual analogy), surface structural similarity, and literal similarity (identikit) (Falkenhainer, Forbus, & Gentner, 1989).

Analogies can be positioned in a graded continuum of incremental scaffolding from the simple to the more complex semantic relational and object-based AR (Gentner, 1983). Similarities which are identical or literal are at the first rank of the continuum. The middle rank consists of metaphors and conceptual relational analogies, with few concrete object attribute similarities, containing mainly implicit relational abstract semantic similarities. At the third rank of the continuum are semantically distant and obtuse abstract semantic similarities, which are found in creative AR and new generalised scientific theories, laws, and models. The following continuum (figure 1a) describes the graded differences from literal/complete similarities, to analogies with relational metaphors, to creative relationships underpinning new scientific generalised AR (Green et al., 2006; 2010; 2012).

Analogical abstractions can be based on language exemplars, which contain coherent logical comparisons and relational analogies (Gentner et al., 2011). Therefore, language learning often facilitates acquisition of various metaphorical and semantic analogies, which are used as scaffolding blocks to create new knowledge structures and generate new abstract ideas or new scientific models and discoveries (e.g., maths and science new insights and theories). Analogical learning enables learners to transfer knowledge through conceptual mapping from maths to science related issues, which is portable to solve new problems and make sense of new phenomena. Therefore, AR helps to align existing physical object similarities and semantic relational evidence to other related phenomena (e.g., music, construction, engineering applications), thus increasing the range and quality of understanding. AR facilitates incremental cross situational learning of new physical and abstract scientific categories which can be used in future learning scaffolding to construct new comparative physical and abstract scientific schemas (Gentner, 1983; Gick & Holyoak, 1983).

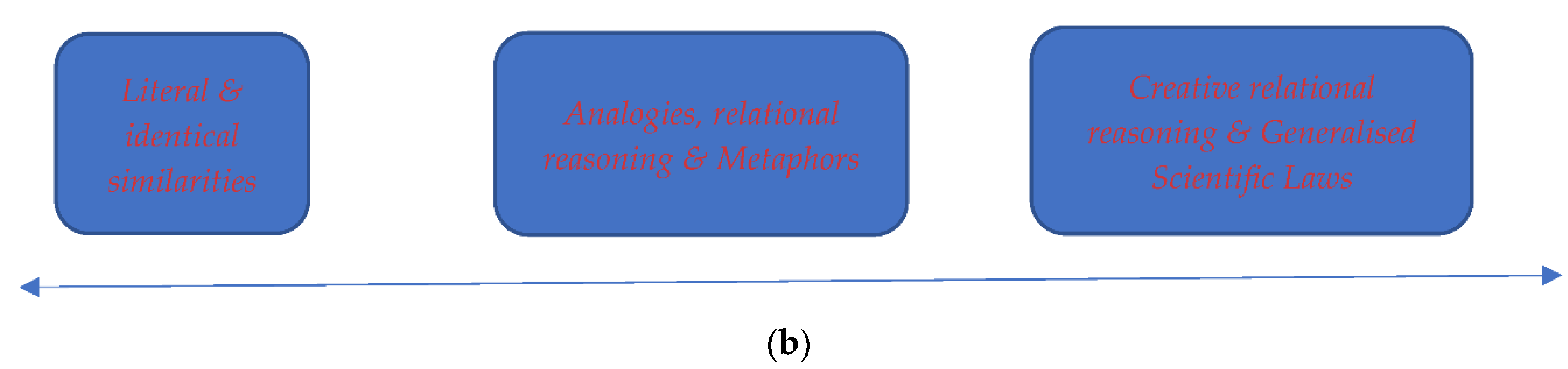

The second,

multiconstraint theory (Holyoak & Thagard, 1997), proposes that there are

three broad parameters or conditions which underpin AR. The first parameter, is that analogies contain

direct and obvious similarities at any level of conceptual abstraction between the analogy source and target analogy outcome. For example, an analogy concerning visuospatial attributes of objects, events or attitudinal intentions should be directly and obviously compared with equivalent target objects, events or attitudinal analogies. The second analogical parameter, is the

consistent isomorphic structural parallels between the relations of the source and the target analogue. For example, the isomorphic mapping between the visuospatial source analogy should be compared with homologue visuospatial analogies to generate direct and empirically coherent inferences, based on one-to-one correspondences to ensure consistent interpretation of the relational analogies. The third parameter, is the type of

implied goal or reason and semantic meaning between the source and target analogue. For example, if the source analogue is an abstract goal or intention or personality trait, the implied target analogue outcome should be able to map out and show a similar relational connection, which corresponds logically to the source analogue (see

Figure 1b). The multiconstraint theory suggests that relational reasoning can be part of visuospatial analogies, as opposed to the structure-mapping theory which suggests that relational reasoning is contained in both object and semantic conceptual analogies.

The major difference between the two theories is that Gentner (1983) extends and includes AR into the creative insights, ideas and concepts that are not easily apparent similarities. Fluid intelligence is normally associated AR and the generation of novel creative thinking and innovative solutions (Green et al., 2006). According to Green et al. (2006) AR is associated with fluid intelligence and it is a form of relational conceptual reasoning, which analyses different types and degrees of similarities to make new logically sound inferences to create new knowledge and new conceptual maps. A priori knowledge of abstract and empirically concrete types of knowledge are used to create new schemas of relational analogies and reasoning about all types of new relationships (Goswami, 1992; 1996). This relational process of a priori and posteriori knowledge can be achieved by the usage of semantic memory. AR can be achieved if there is sufficient and relevant experiential knowledge in the working memory to produce new analogies and conceptual maps (Halford, 1993).

The definitions of AR include relational similarities of both physical/structural visuospatial objects and events, as well as relational similarities of abstract semantic constructs. Analogies according to Gentner & Markman (1997) are based on perceived abstract relations of objects or/and semantic meanings coalescing to generate logical mapping of concepts which correspond to systematic rules of similarity above and beyond the physical and structural object attributes. Analogies convey implicitly systematic connections of logically coherent similarities between abstract relations as well as obvious similarities of factual visuo-spatial attributes, which may or may not contain emotional or conceptual comparisons. Therefore, abstract relational analogies are conceptual maps of higher order predicates, which are qualitatively different from the lower levels of analogies of factual object attributes. The research focus of this paper is on the relational analogies that young adolescents mentally construct during visuospatial and verbal semantic tasks while performing maths and science tasks, which require AR of similarities for both visuo-spatial and semantic conceptual relations.

2.1. Review of age and developmental stages of AR

Analogical thinking is age related and developmental changes are due to increasing educational knowledge and experiential learning over the years (Gentner & Rattermann, 1991). AR development in children is an incremental process dependent on both educational accretion and physical brain maturation. The brain’s ability to process incrementally more complex analogical relational problems increases as the relevant brain networks develop with age and training. Several researchers suggest that analogical relational reasoning evolves from simple visuospatial similarities during early childhood to more abstract semantic relational analogies during adolescence and early adulthood (Gentner, 2010; Childers et al., 2016). Analogical reasoning in 3-years old children starts with detecting similarities and understanding simple object attributes matching-to-sample task analogies, in a specific domain, and gradually progress to a relational shift by focusing on more abstract relational similarities (Gentner & Rattermann, 1991). Analogical reasoning for children of more than 5 years old, which have been exposed to more educational experiences, improves incrementally to more than one relational analogy and are able to process higher levels of semantic abstract relational match- to-sample task analogies, deciphering metaphors and causal analogies (Rattermann & Gentner, 1998; Halford, et al., 1998). Anderson et al. (2018) found that 3 months old children can discriminate between “same-different” attributes of stimuli, therefore, language is not a prerequisite to making simple structure-mapping relational comparisons, but language acquisition does help in the gradual developmental shift for processing more abstract relational matching-to-task analogical reasoning (Hespos, Anderson, Gentner, 2020).

The experimental stimuli, researchers have used with children, vary from simple action type of comparisons depicted in cartoons and word pairs, which can assess analogical reasoning based on physical features and conceptual relations of function, e.g., bread: slice of bread :: orange:? and/or using cartoon stimuli that contain a similarity to select between three options, e.g., slice of orange, slice of cake, or orange balloon (Ferrer et al., 2009). Analogical reasoning in young children is possible if they have relevant domain specific knowledge and therefore, can remember certain events, meanings, and object characteristics to use during analogical processing tasks and being able to control or inhibit irrelevant information (Morrison et al., 2011).

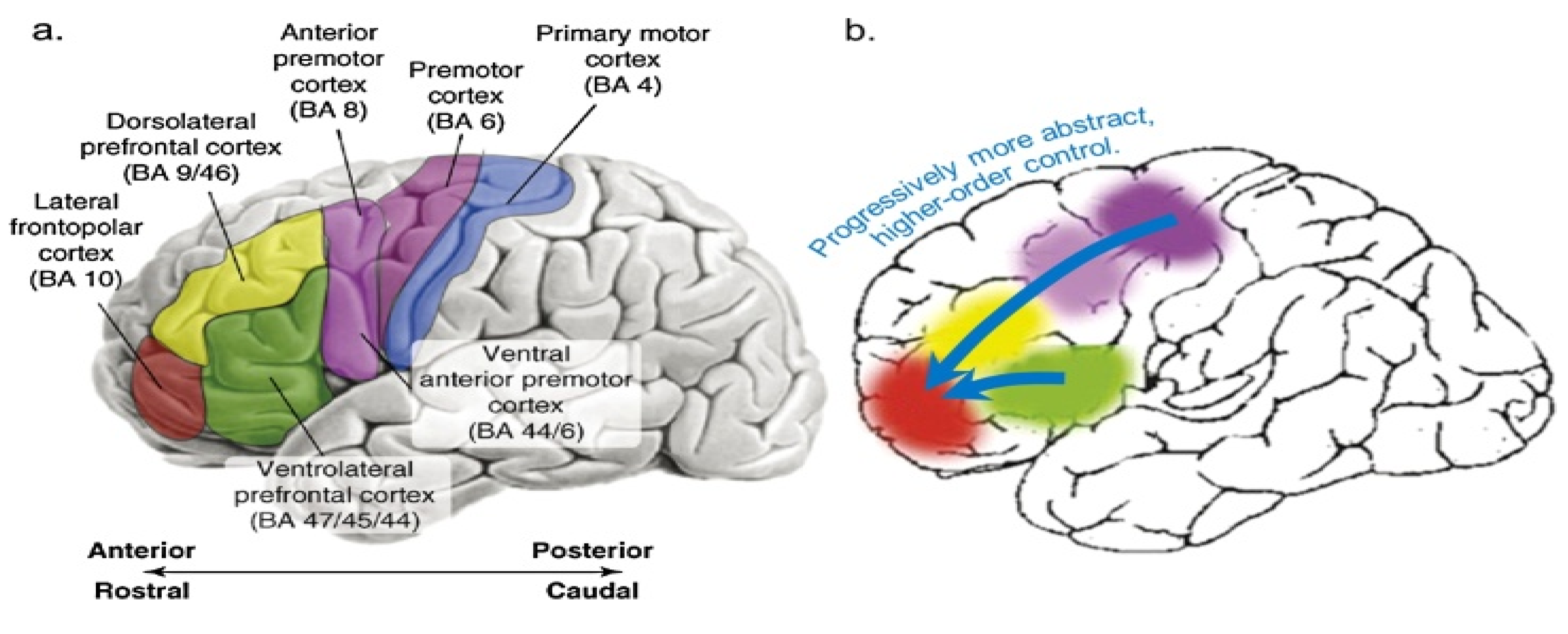

Brain development is dependent on biological age and therefore as children and adolescents grow, their brain’s ability to process more complex analogies increases (Dumas, Hummel & Sandhofer, 2008; Thibaut, French & Vesneva, 2010). Age related brain development facilitates incrementally better functionality of brain regions such as BA10 or corresponding to the Rostro Lateral Prefrontal Cortex (RLPFC), which is associated with higher level of cognition, prospective memory, working memory, multitasking and task switching (Crone et al., 2009). Children’s ability to process complex relational information is affected by their executive functional ability to inhibit irrelevant and distracting information (Morrison, Doumas, & Richland, 2011). The dorsal prefrontal cortex (DPFC) and the executive network (EN) are associated with integrating relational analogies, theory of mind, processing of abstract information (Christoff et al, 2004; Mason et al., 2007), and selective attention of stimulus-independent information (Burges et al., 2005; Burges, Dumontheil & Gilbert, 2007).

The hypothesis that during adolescence brain processing of abstract ideas and abstract thoughts is a non-linear development, associated with brain structure and grey matter volumes, which influence behavioural outcomes in a variety of tests, was tested using a multimethod approach using behavioral and functional MRI data (Dumontheil, Houlton, Christoff & Blakemore, 2010a). Using reliable relational AR stimuli, a sample of female participants N=178, age 7-27 years old for the behavioural study; and N=37, age 11-30 years old for the fMRI study, found that the biggest significant improvements were observed by the 7- 9 and 14-17 years old. However, the 9-11 performed at adult age levels, but performance accuracy dropped for the 11-14-years old. When the researchers investigated the combined effects of reaction time in relation to response accuracy (a ratio of speed over accuracy) for 2-relational, vs. 1-relation tasks, the data suggested a linear performance improvement during late childhood and mid-adolescence, with a significant improvement between 7–9 and 14–17 years old age groups.

Overall relational reasoning for processing 2-relational vs 1-relational reasoning tasks improved with age until maturity (Dumontheil, et al., 2010a). They found confirmatory evidence of complex age related linear and non-linear changes in processing accuracy especially during mid-adolescence age groups. Age related structural brain changes in RLPFC, and medial superior frontal gyrus are posited to influence behavioural outcomes for mid-adolescence and adulthood. But they also suggest that educational input, working memory (WM), and cognitive maturation skills may play a mediating role in influencing behavioural outcomes. Dumontheil, Hassan, Gilbert, & Blakemore (2010b) fMRI study found that age is related to the ability for processing self and other/stimuli-generated thoughts, and therefore relational reasoning is associated with brain developmental changes, partly involving the dorso lateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) during adolescence. Their fMRI data analysis produced positive correlations between age and specific brain region activations including the DLPFC (see

Figure 2).

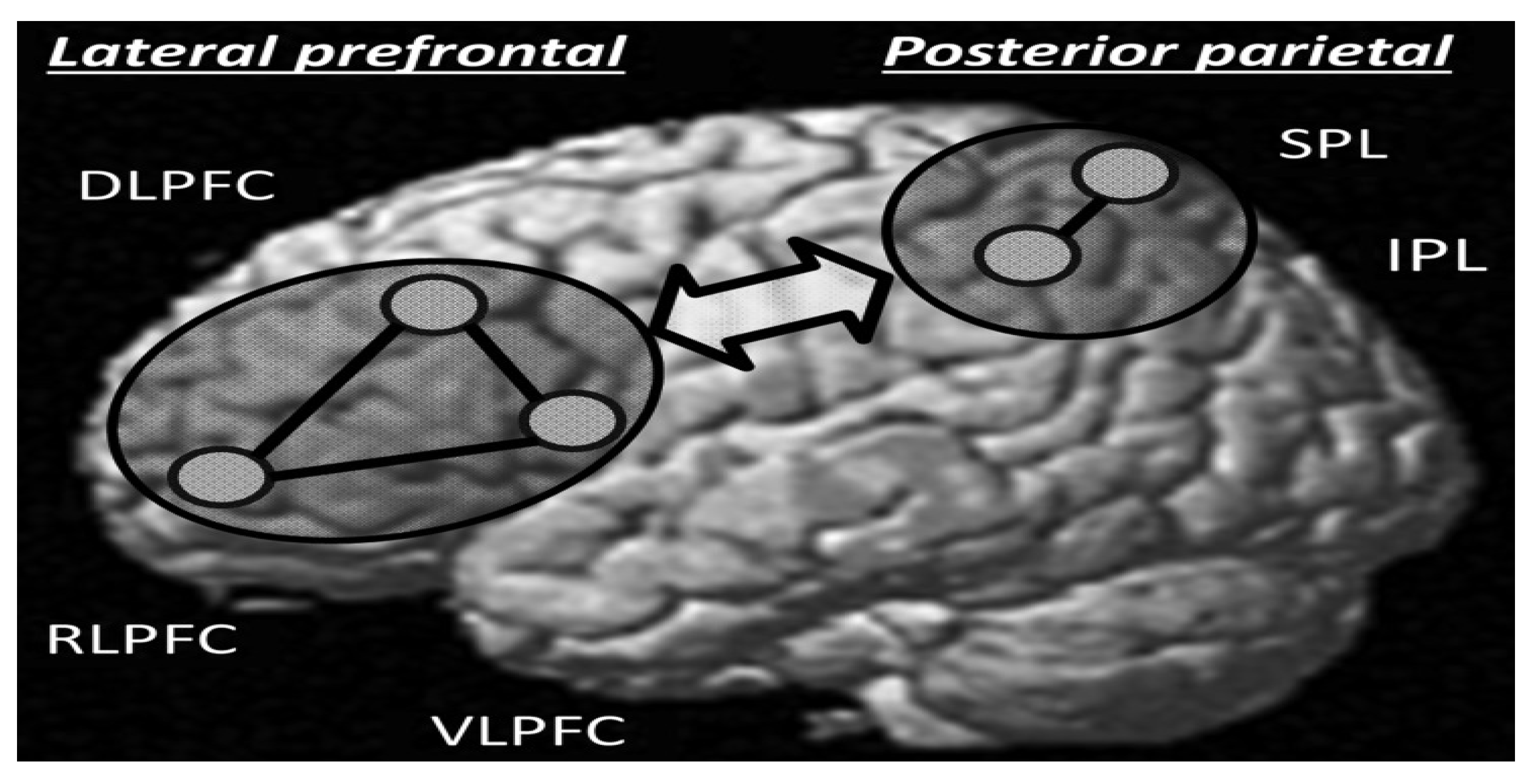

The proposition that reasoning is contingent to age and brain development stages was recently tested with a large sample (N=132) of children and adolescents ranging from 6-18 years old (Wendelken, et al., 2018). They hypothesised that two major brain network connectivities are associated with reasoning abilities, namely the lateral fronto-parietal network (LFPN) (Wendelken, et al., 2018). Their results suggest that for the 6-8 years-old children’s LFPN connectivity was not associated with reasoning, but the actual speed of processing mediated the children’s reasoning ability. For 9-11 years old, LFPN connectivity between left and right RLPFC was mediated by working memory (WM). The 12-18 years-old reasoning abilities were associated with strong connectivity between the left RLPFC and inferior parietal lobule (IPL). More specifically, the left anterior prefrontal cortex (LAPFC, BA 47/45), which is activated during controlled semantic retrieval, was found to be positively correlated with participants’ age. The research supports the hypothesis that improved performance during middle childhood and early adolescence on AR tasks is driven largely by improvements in their ability to selectively retrieve task-relevant semantic relationships (Wendelken, et al., 2018). Therefore, age and development stages of reasoning ability are associated with different degrees of connectivity in the RLPFC-IPL network and that development of reasoning is strongly associated with late childhood and early adolescence (Whitaker, Vendetti, Wendelken, & Bunge, 2018) (see

Figure 3).

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 27 experiments attempted to identify the statistically significant activation networks for AR using semantic and visuospatial tasks (Hobeika et al., 2016). The researchers suggest that AR activates a number of cortical (frontal and parietal cortices) and subcortical basal ganglia (BG) structures and provides evidence that analogical and deductive reasoning are sensitive to the types of stimuli used. The data suggest that bilateral posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and right middle frontal gyrus (MFG) are relevant for relational arguments; left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and BG for categorical arguments; and left precentral gyrus (PG) for propositional arguments. Urbanski et al. (2016) show that the left RLPFC is a critical node in the analogical reasoning processing network and suggest that the consistently common brain area activated during all studies was the left RLPFC. The semantic and visuospatial types of stimuli activate differentially domain specific brain areas (inferior and middle frontal gyri) from general brain regions (left RLPFC). Similarly, differences in brain activation were found between visuospatial and matrix types of stimuli analogies, with distinct regions in the left and right networks of the left RLPFC. Different types of analogical tasks produce different brain anatomical activations and therefore accurate prediction of brain activation depends on the fine differences between the types of stimuli which afford more nuanced and accurate understanding of AR. Other meta-analyses and voxel-based morphometry studies found that the left RLPFC is consistently correlated with AR (Vartanian, 2012; Aichelburg et al., 2014). The implication of a left RLPFC can be explained by the verbal semantic type of stimuli being processed and the right RLPFC for processing more visuospatial types of information stimuli (Cho et al., 2010; Hampshire et al., 2011). A transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) experiment found that, the anodal stimulation tests produced strong positive correlations between tDCS stimulation and improvement in memory source retrieval at the RLPFC, but no significant change occurred in AR and visuospatial perception task performance (Westphal et al., 2019). Therefore, the RLPFC is consistently engaged in multiple activities and is positively associated with WM activation during abstract conceptual and AR processing.

2.2. Working Memory, Executive Network, and IQ relationships with AR

Researchers suggest that WM and IQ are positively associated with educational success (Cowan & Alloway, 2008; Alloway & Alloway, 2010; Donati, Meaburn & Dumontheil, 2018). However, there are contrasting views on the specific relationship between WM and IQ. Some researchers view the two constructs as identical (Colom et al., 2004); but others recognise the similarities and shared attributes, but they consider them as two different brain functions (Alloway et al., 2004; Conway et al., 2002). A meta-analysis found that WM and IQ are not identical but highly correlated and have a shared variance of approximately 20%, but both account for learning success (Ackerman, Beier, & Boyle, 2005). Therefore, it is difficult to clearly delineate precisely IQ’s and WM’s contributions towards learning, but the research evidence suggests that although they are dissociable, they are highly related at different stages of cognitive processing (Alloway & Alloway, 2010; Morris, Farran, & Dumontheil, 2019).

An extensive review found that several neuroimaging studies support the idea that during adolescence the RLPFC is strongly associated with processing abstract logical thinking, relational analogical integration, and episodic memory retrieval (Dumontheil, 2014). According to Barker and Warburton (2020), associative recognition memory, used during AR, combines different types of information representation in specific contexts of time and space. Associative memory integration depends on widespread cooperation of brain networks and multiple overlapping brain subnetworks are co-activated to perform specific behavioural and cognitive memory retrieval tasks. For example, the hippocampal-prefrontal networks process object spatial and temporal memories, but other networks process experiential and behavioural representations (Barker & Warburton, 2020). However, these findings are based on correlational studies but not causal research evidence, because, the left frontopolar cortex is also activated during inductive types of relational reasoning, and WM brain regions were more active during deductive reasoning tasks than inductive processing (Goel, 2014; Goel et al., 1997). In addition, similar activations in the frontopolar cortex during abstract relational integration and during AR of relational categorization, was not related to WM activation (Green et al., 2006). Strong activation occurred in the parieto-frontal network during processing and analysis of both AR and category relational processing tasks for semantic categorisation (Green et al., 2006, Green, et al., 2012). These researchers suggest that WM mediates analogical reasoning, which underpins mapping out logically relational criteria used for categorisation and making mental leaps.

Memory and AR tasks are associated with activation in the left RLPFC, while the right RLPFC is activated during reasoning tasks only, and serves an auxiliary role to the RLPFC, which is responsible for domain general reasoning processing (Westphal, Reggente, Ito, & Rissman, 2016). These fMRI findings provide supporting evidence that the RLPFC processes domain general and specific representations during evaluation and integration of relevant analogical information, and that episodic memory is engaged during correct information retrieval and monitoring of different types of computations (Westphal et al., 2016). These researchers suggest that the reason for memory engagement in the left RLPFC may be due to the verbal types of stimuli used, which is consistent with the findings by Bunge, et al. (2005) and Green et al. (2010). Westphal et al. (2016) suggest that the multiple cognitive processes carried out by the RLPFC interact flexibly with the default mode network (DMN), the memory retrieval network (MRN) and the semantic network (SN) as well as with many posterior networks involved in problem solving, fluid intelligence and behavioural decisions.

AR is often associated with the executive control function (EF), which is responsible for coordinating WM, goal integration, motivational intentions and inhibiting irrelevant information (Kruger et al., 2002; Reynolds et al., 2006; Hobeika et al., 2016). Several brain networks are involved during AR problem solving, such as EF, WM, the salient system (Downar et al., 2002), and the semantic control system (Binder et al., 2009; Lambon et al., 2017) which activate the DLPFC as well as the parietal and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Bartley et al., 2019). Relational reasoning is therefore associated with EF which includes WM, attentional control for individual tasks and new task switching (Miyake et al., 2000; Ferrer, O’Hare & Bunge, 2009). Research with patients with clinical damage to the EF network, impairs analogical relational reasoning processing, which is evident in several studies with various populations, varied clinical contexts and types of assessments (Krawczyk et al., 2008; Morrison, Doumas, & Richland, 2011; Frausel, Simms, & Richland, 2018).

2.3. AR association with maths and science performance

Understanding maths and science is essential for success in education and virtually all aspects of life because they assist in discovering and analysing patterns and relationships embedded within concepts and visuospatial physical phenomena (Bressan, 2018; Project 2061, 2009). Making sense of the relationships between numbers is the basis for developing arithmetic and mathematical reasoning skills useful for students at all levels of education including science subjects (Dehaene, 1997). Several longitudinal research studies in the UK (Bynner & Parsons, 1997; 2006) and globally (OECD, 2016) found that poor skills in maths can negatively impact employment opportunities, health outcomes, social-civic involvement, and overall quality of life. Educational progress for all age groups is affected by the ability to process effectively mathematical concepts such as counting, ranking and proportional comparisons, often represented as percentages or ratios (Schwartz, et al., 2018; 2020). Processing numbers and maths skills are fundamentally important because they are domain general abilities, which utilise relational reasoning and therefore rely on many brain regions to carry out different types of computations (Dehaene, 2011; Dehaene, Bossini, & Giraux, 1993). Several researchers found that there is a natural educationally supportive relationship between maths and science and the two are by necessity integrated and mutually beneficial for learning new concepts (Czerniak, Weber, Sandmann, & Ahern, 1999; Goldstrom, 2004; Lonning, & DeFranco, 1997).

Processing numerical concepts necessitates semantic comprehension of numerical symbols, manipulation and remembering relevant processes to apply for solving maths and science problems (Prado, Chadha, & Booth, 2011)). Researchers suggest that WM is essential function for processing numerical concepts and the PFC is positively associated with generic abstract cognitive functions of computing, monitoring, and integrating mathematical concepts (Christoff & Gabrieli, 2000). The amount of memory resources required for complex maths computations are greater than for simple tasks (Fehr et al., 2007; Kong et al., 2005), and a number of cognitive models have been suggested regarding how the brain processes numbers. One of the most cited models is the ‘triple code’ model by Dehaene & Cohen (1995; 1997), which predicts that numerical calculations are processed in three formats: a) visual processing for Arabic symbolic numerals, processed bilaterally by the inferior ventral occipital-temporal brain areas; b) assessing quantity magnitudes and analogical relationships, processed by the inferior parietal regions; c) and verbal semantic processing of words describing mathematical relationships, activating the left perisylvian areas (Dehaene, 1992; Dehaene & Cohen, 1997).

A meta-analysis conducted by Arsalidou & Taylor (2011) proposes a more comprehensive model of additional brain networks regarding mental arithmetic processing, by adding the inferior parietal cortex, temporal cortex, verbal system, basal ganglia, thalamus, cingulate gyri, the insula, the cerebellum, and the mediating role WM plays in assisting the prefrontal cortices (DLPFC (BA 9, BA 46) and frontopolar (BA 10). A recent meta-analysis, with children 14 years and younger, found strong positive activation in the parietal area (e.g., inferior parietal lobule and precuneus) and frontal cortices (e.g., superior, and medial frontal gyri) for processing mental-arithmetic; and the insula and claustrum, which are involved during maths problem solving (Arsalidou, Pawliw-Levac, Sadeghi, & Pascual-Leone, 2018). Understanding science and using scientific reasoning procedures to solve various problems, is often associated with scientific literacy competence, deemed to be essential for multiple educational and professional applications. During cognitive processing of novel tasks, e.g., maths and science problem solving, or aiming to discover novel patterns without any obvious order or sequence, brain activation increases in the left premotor area, left anterior cingulate, and right ventral striatum, but decreases in the right DLPFC and parietal areas (Berns, Cohen, & Mintun, 1997). According to Nenciovici, Allaire-Duquette & Masson (2019) there are three main types of scientific reasoning tasks: overcoming misconceptions, causal reasoning, and hypothesis generation and testing. Their meta-analysis suggests that there are similar brain activations for all three types of scientific reasoning processing which are: the lateral prefrontal regions, which are also related to EF, and the middle temporal regions which are associated with declarative memory.

A mixed methods study, combining behavioural survey and fMRI data to investigate the complex interactions between analogical relational reasoning and performance in maths and science tasks, suggests that verbal AR with WM and verbal IQ are strong predictors of science and maths accuracy (Brookman-Byrne, Mareschal, Tolmie, & Dumontheil, 2019). In addition, they found that matrix non-verbal relational AR, was positively associated with science accuracy and multiple brain regions were activated, including the occipital cortex, superior and inferior parietal gyri, precuneus, pre-supplemental motor area (PSMA), posterior parts of superior and middle frontal gyri, anterior insula, posterior parts of the inferior and middle temporal gyri. On the other hand, maths processing was positively associated with verbal AR, the anterior temporal cortex, and negatively associated with nonverbal matrix AR and the middle temporal gyrus. Matrix non-verbal relational reasoning tasks produced positive correlations with parietal, frontal, and temporal cortex clusters, as well as in the cerebellum, the left superior parietal lobule (SPL) and the left middle temporal gyrus (MTG). The literature review supports and leads to the proposition of the following hypotheses to test empirically with behavioural and fMRI neuroscience research protocols.

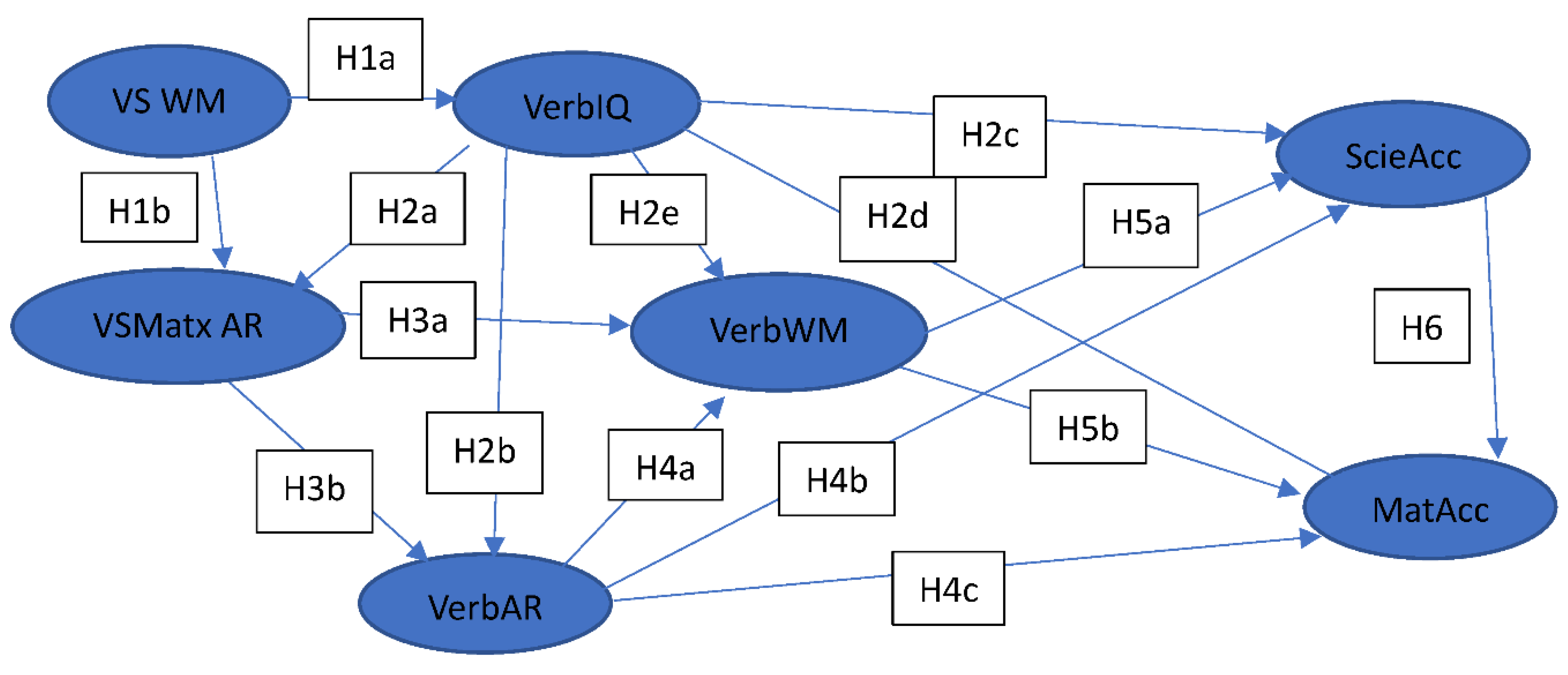

2.4. Hypotheses to be tested for both the behavioural and fMRI data

Hypothesis 1: WM (verbal & Visuospatial WM) are positively related to Verbal IQ (H1a) and Visuospatial Matrix AR (H1b).

Hypothesis 2: Verbal IQ is positively related to Visuospatial Matrix AR (H2a), verbal AR (H2b), Verbal WM (H2c), with maths (H2d) and science (H2e) performance.

Hypothesis 3: Visuospatial Matrix AR is positively related to Verbal WM (H3a), and Verbal AR (H3b).

Hypothesis 4: Verbal AR is positively related to Verbal WM (H4a), Science (H4b) and Maths (H4c).

Hypothesis 5: Verbal WM, mediates the relationship between IQ, Verbal AR and Visuospatial Matrix (VS) AR, and is positively related to science (H5a) and maths (H5b) performance.

Hypothesis 6: Science is positively related to Maths (H6a for behavioural data).

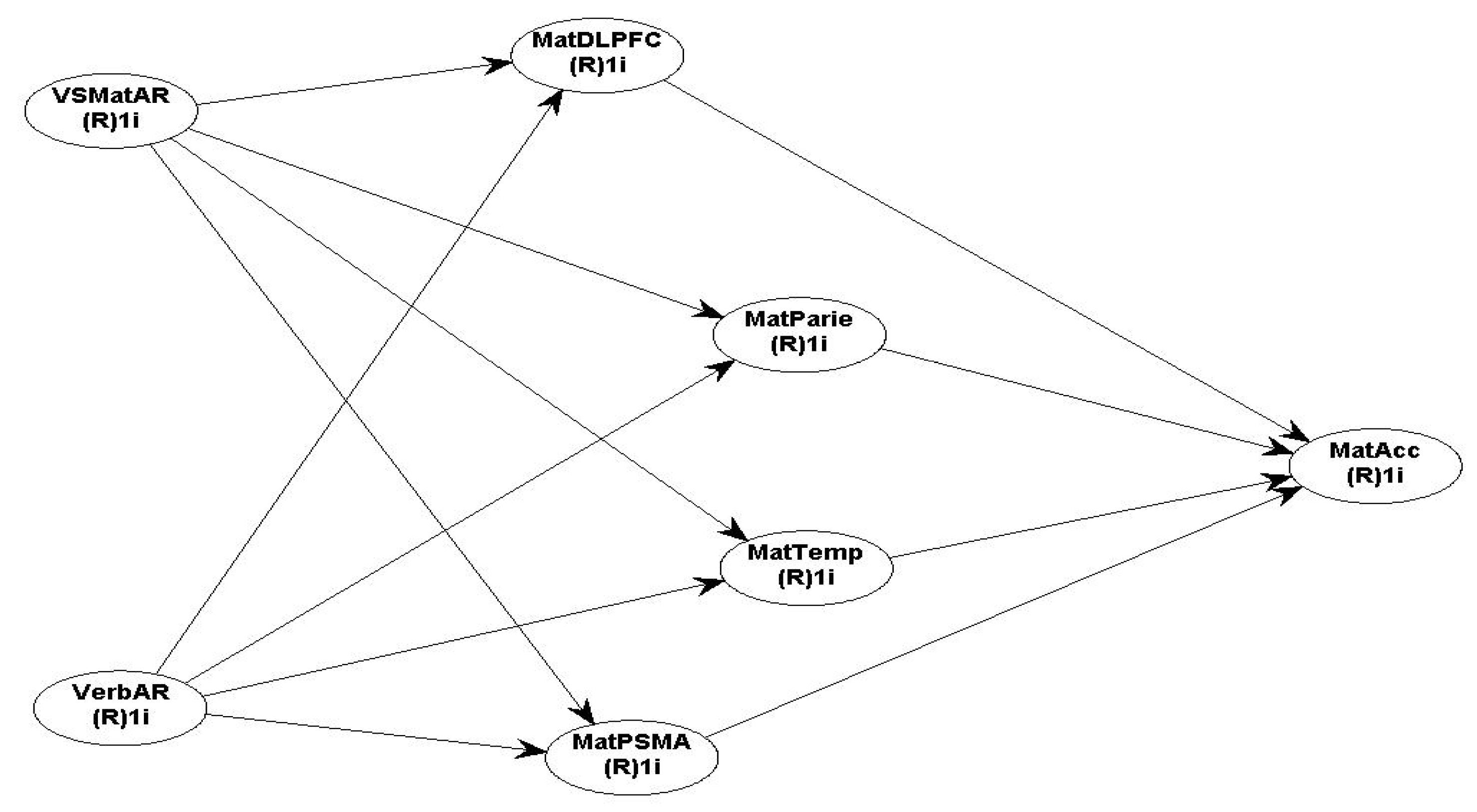

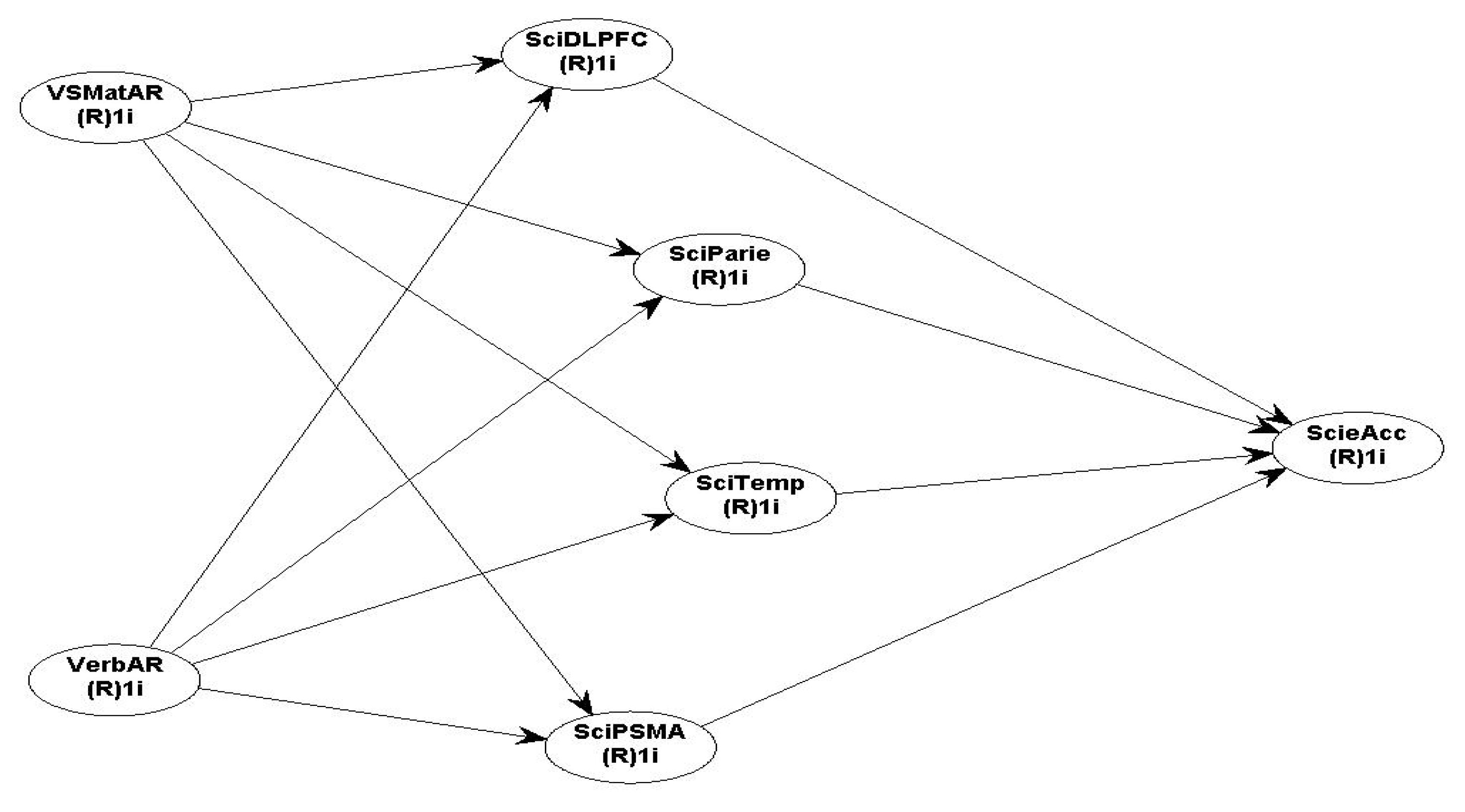

Hypothesis 7: For the neuroscience fMRI data; there is a positive relationship between Verbal AR and Visuospatial Matrix AR with activation in the frontoparietal network (H7 a, b, c, d, e), which includes the DLPFC & RLPFC, Parietal, temporal, and PSMA. In turn, all four brain regions of interest are positively related to Maths and Science accuracy (DVs).

5. Discussion of Behavioural and Neuroscientific fMRI Research findings

5.1. Discussion of Behavioural data results

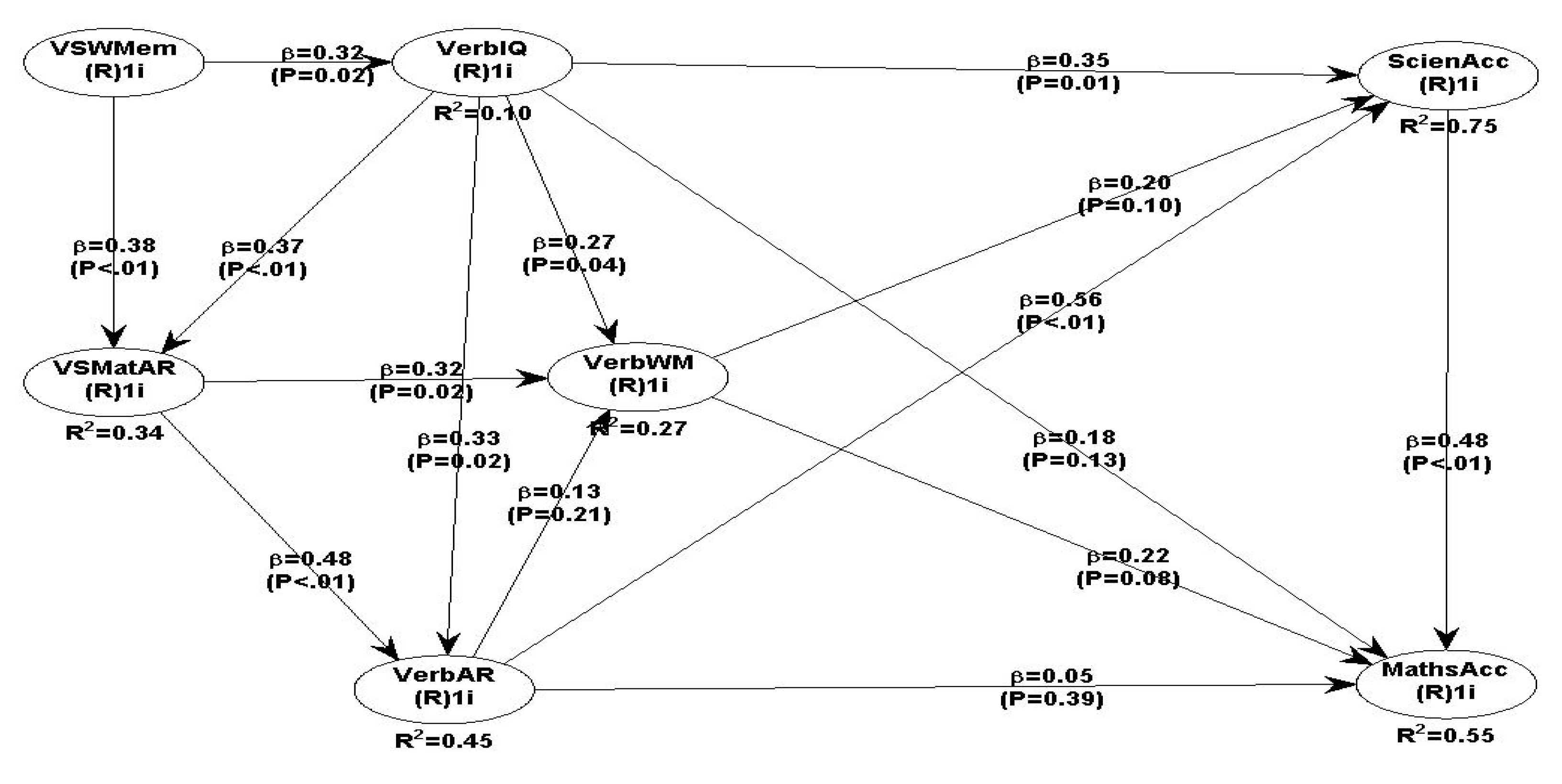

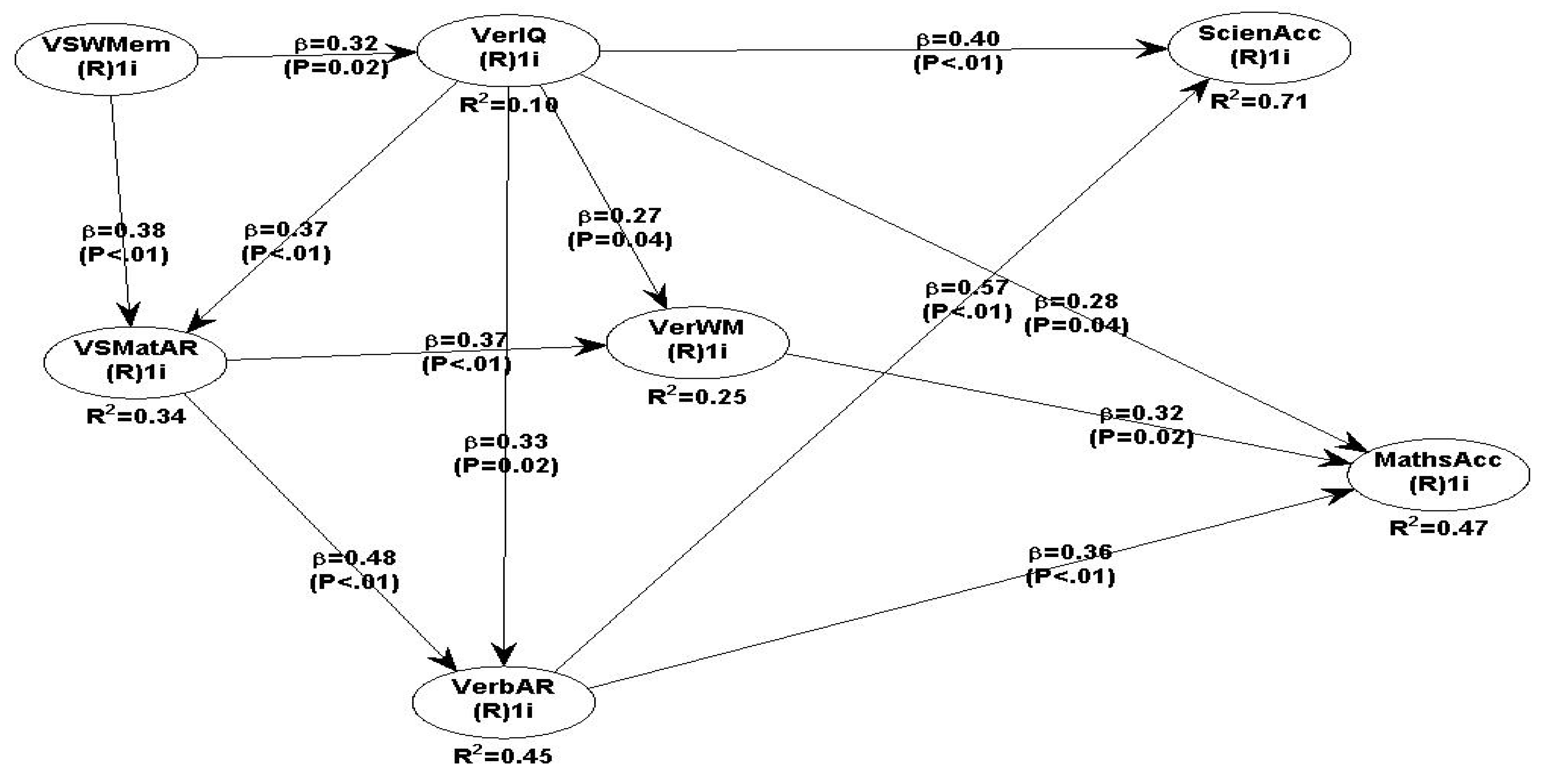

This discussion evaluates first the behavioural and secondly the neuroscience fMRI results. Overall, the behavioural data results support most of the hypotheses made except two, namely the VerbAR->VerbWM (β = 0.13, P=0.21) and VerbWM->ScieAcc (β = 0.20, P=0.10). However, several interesting findings emerged, which are useful to academics and educational practitioners. The behavioral SEM data modelling suggests that verbal IQ is an important influence for maths (β = 0.28, P=0.04) and science accuracy performance (β = 0.40, P<.01). In addition, verbal IQ is positively related to a number of IVs, namely, VerbWM (β = 0.27, P=0.04), with verbal AR (β = 0.33, P=0.02), with VSMatrix AR (β = 0.37, P<.01) and with VSWM (β = 0.32, P=0.02). No other study has tested simultaneously with SEM the combined effects of verbal IQ on maths and science accuracy combined with verbal and VS matrix AR. Verbal IQ appears to be a driving influence for multiple cognitive processes including memory for verbal and matrix visuospatial information, as well as VerbAR and VS matrix AR. In fact, verbal AR ->science (β = 0.57, P<.01) and verbal IQ->science (β = 40, P<.01) are the two strongest predictors of science accuracy and therefore, educationalists need to consider the multiple learning benefits by developing strong verbal analogical reasoning skills and integrate relevant scientific semantic knowledge to improve teaching and outcomes in maths and science. Verbal WM is strongly associated with VS matrix AR (β = 0.37, P<.01), and also as a mediator with maths accuracy (β = 0.32, P=0.02), which suggests that overall verbal IQ combined with Verbal AR skills and VerbWM are the strongest and most significant predictors for science and maths performance for adolescent students.

The strong relationship between VSMatrix AR->verbal AR (β = 0.48, P<.01) suggests a positive contribution to the overall association with maths accuracy (β = 0.36, P<.01). The vital role that VSWM plays with VS matrix AR (β = 0.38, P<.01), and VSWM with VerbIQ (β = 0.32, P=0.02) suggests that students need both visuospatial empirical experiences and skills, because they are strongly associated with Verbal WM, Verbal IQ and in turn with Verbal AR. In combination, VSWM and VerbWM contribute indirectly to the accretion of knowledge and understanding of procedural methods for Visuospatial and Verbal AR tasks, which in turn are relevant resources for more efficient visualising processing of maths and science relationships and conceptualising new analogical relationships, thus creating new ideas and better thinking models.

A second major finding is that, science performance is strongly predicted by two factors, primarily by verbal AR (β = 0.57, P<.01) and secondly, by Verbal IQ (β = 0.40, P<.01), as well as with an indirect contribution by VSWM-> VerbIQ (β = 0.32, P=0.02) and VSMatAR -> VerbAR. The positive association between maths and science accuracy shown in model 1 (β =0.48, P<.01), suggests that the two subjects share a substantial common body of knowledge and skills and supports the previous findings that effective studying of science needs certain amount of maths knowledge to conduct meaningful calculations and measurements of scientific phenomena (Goldstrom, 2004; Lonning, & DeFranco, 1997). Educational practitioners need to design curricula that combine relevant vocabulary and conceptual knowledge of both maths and science to integrate science and maths literacy with rigorous and clear semantic understanding of relevant conceptual relationships. Relational analogical reasoning appears to improve maths and science performance and therefore students need to understand the foundational meanings and relationships embedded in both maths and science theories. Language teaching should aim to make analogical connections between general as well as domain specific knowledge of maths and science curricula (Nenciovici, Allaire-Duquette & Masson, 2019; Dündar-Coecke, & Tolmie (2020).

5.2. Discussion of the fMRI Results

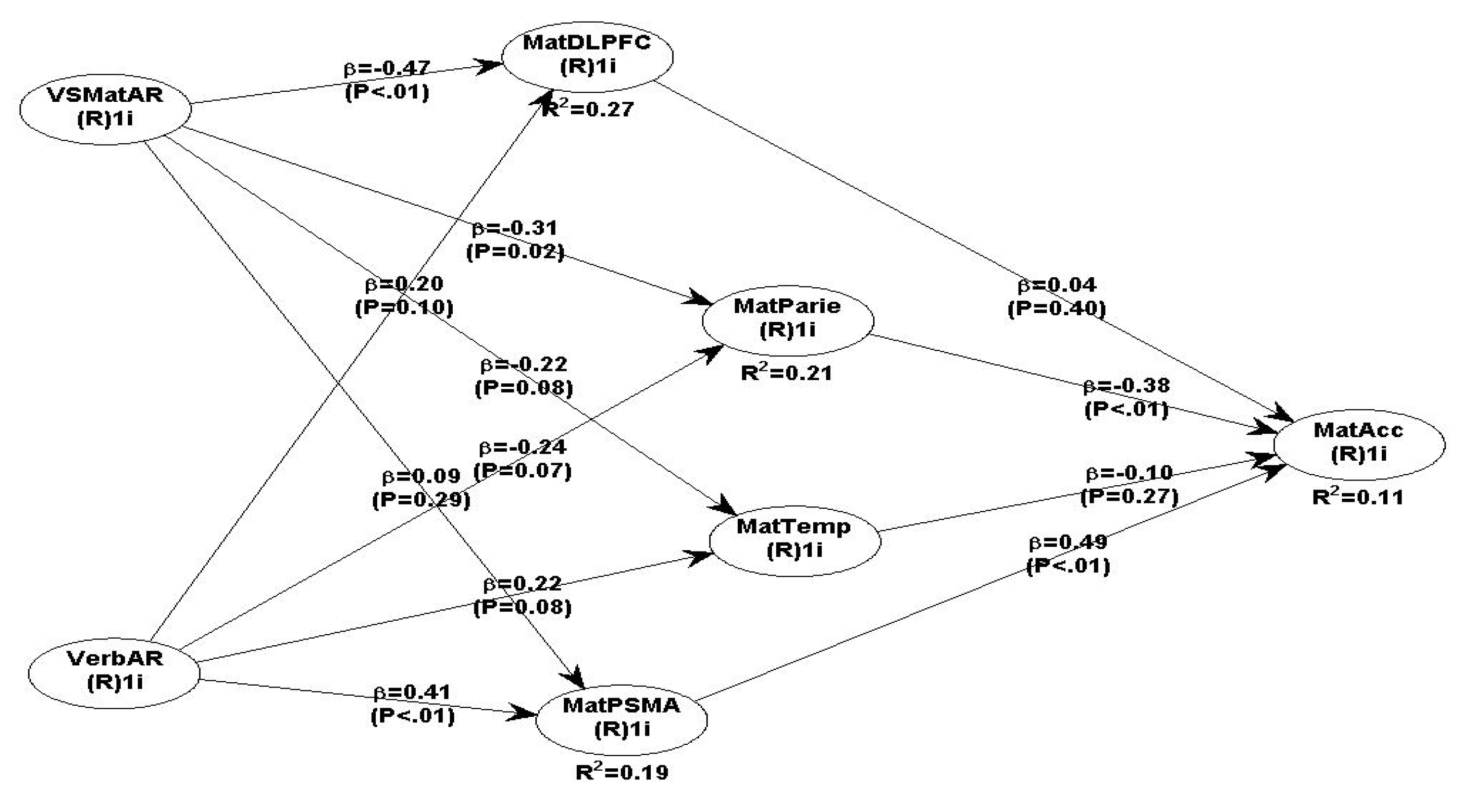

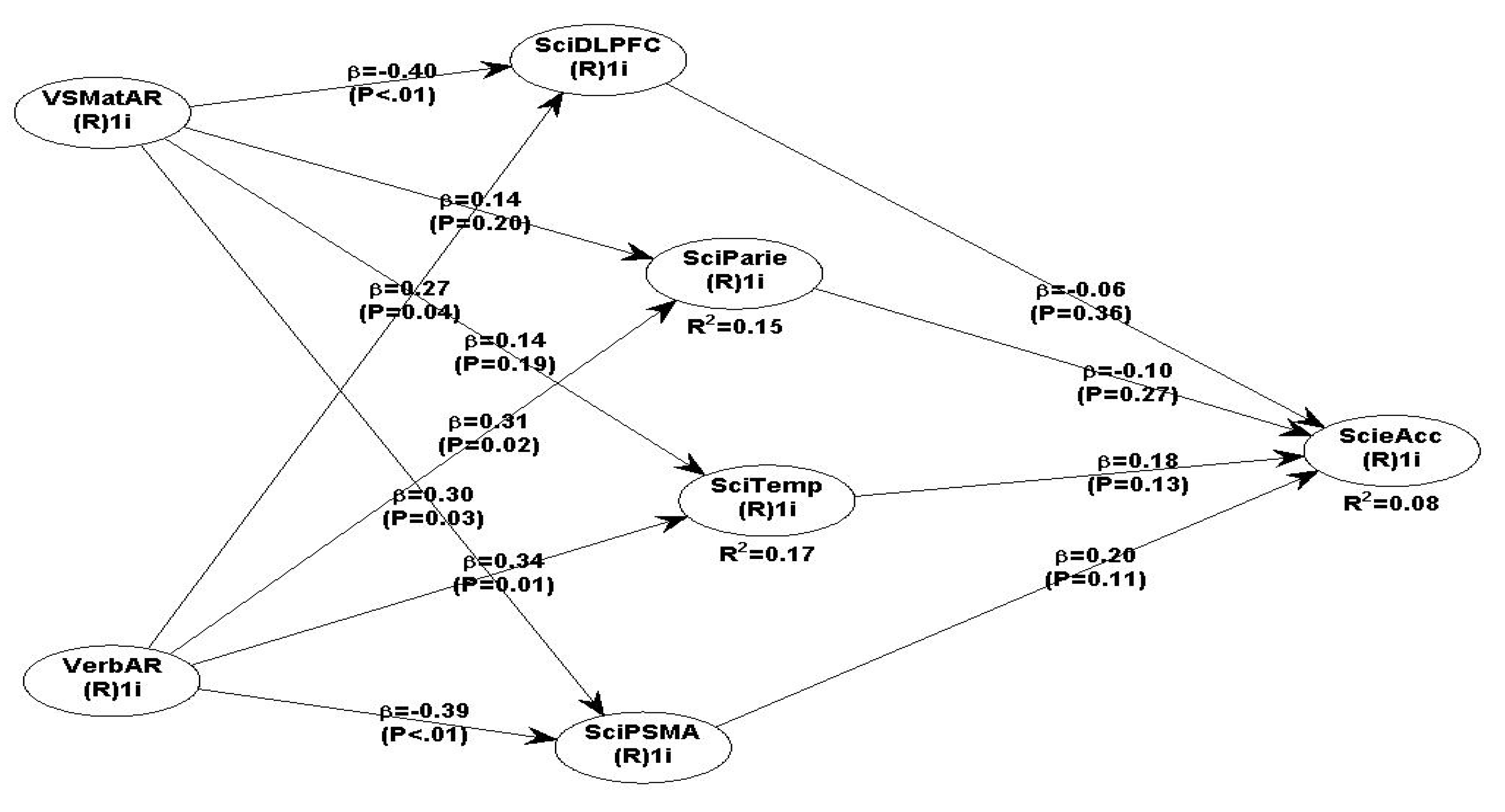

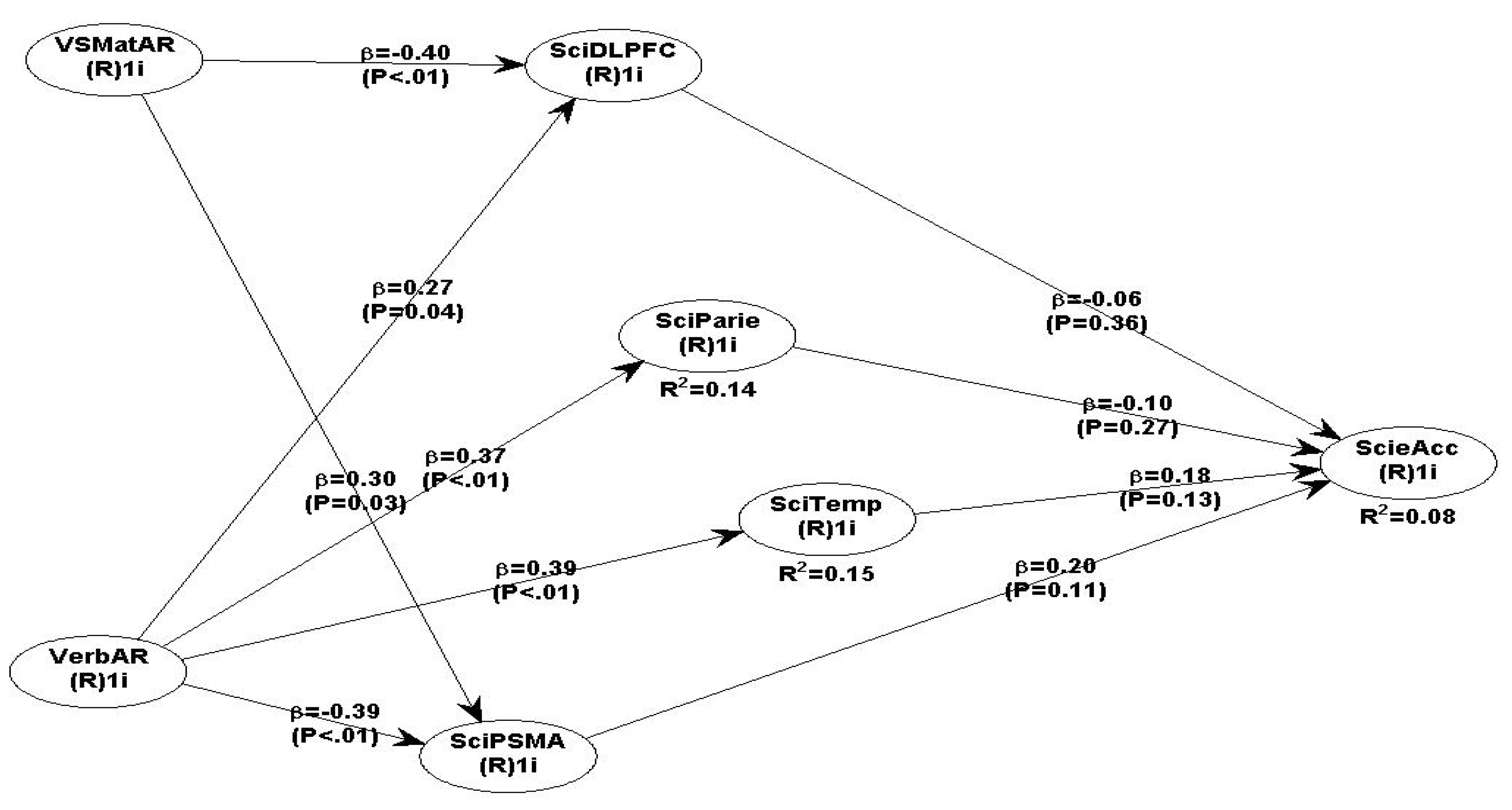

The fMRI maths model 3 produced a mixture of positive and negative relationships between VerbAR and VSMatrix AR with all four brain ROI, which in turn were related to Maths and Science accuracy. The hypothesis that all four brain regions (bilateral DLPFC, Parietal, Temporal and PSMA) would be positively related to Maths accuracy performance is not supported by the actual data results. The only positive and significant path coefficients are between Verbal AR and PSMA (β =0.41, P<.01), and PSMA with Maths accuracy (β =0.49, P<.01). The three statistically significant but negative path coefficients are between VSMatAR -> DLPFC (β = - 0.47, P<.01), VSMatAR -> Parietal (β = - 0.31, P=0.02) and Parietal->Maths (β = - 0.38, P<.01). These three negative path coefficients are possible deactivations due to the lower age developmental stages of the adolescent brains indicating non engagement yet for maths processing (Dumontheil et al., 2010b; Wendelken, Chung & Bunge, 2012). The five statistically non-significant path coefficients between the two IVs with brain ROI indicate that there is no activation during the maths processing, e.g., VSMatAR->Temporal (β = 0.22, P=0.08), VSMatAR ->PSMA (β = 0.09, P=0.29); and VerbAR->DLPFC (β = 0.20, P=0.10), VerbAR->Parietal (β = 0.24, P=0.07), and VerbAR->Temporal (β = 0.22, P=0.08). A plausible explanation is that the fronto-parietal brain networks including the EF and semantic network are not yet fully developed in the adolescent brains and therefore there is no activation during maths and science problem solving (Wendelken et al., 2016; Whitaker et al., 2018; Nenciovici et al., 2019).

The two non-significant path coefficients between the three brain ROI indicate that they are disengaged during the maths processing tasks, namely, DLPFC ->Maths accuracy is very weak and (β= 0.04, P=0.40), and, Temporal ->Maths (β = 0.04, P=0.04). These relationships require further investigation to ascertain if they are caused or influenced by the VS Matrix AR or/and the Verbal AR or both, or if they are due to young adolescent brains’ underdevelopment of relevant networks (Hobeika et al., 2016; Nenciovici et al., 2019). The overall maths model 3 fit and quality indices are within the acceptable levels and therefore the model fits the data well despite the presence of several negative or non-significant path coefficients. The main model fit index, GoF=0.393 is large enough and the Sympson’s paradox ration (SPR=0.750) is close to the ideal level required and therefore all relationships are valid and reliable.

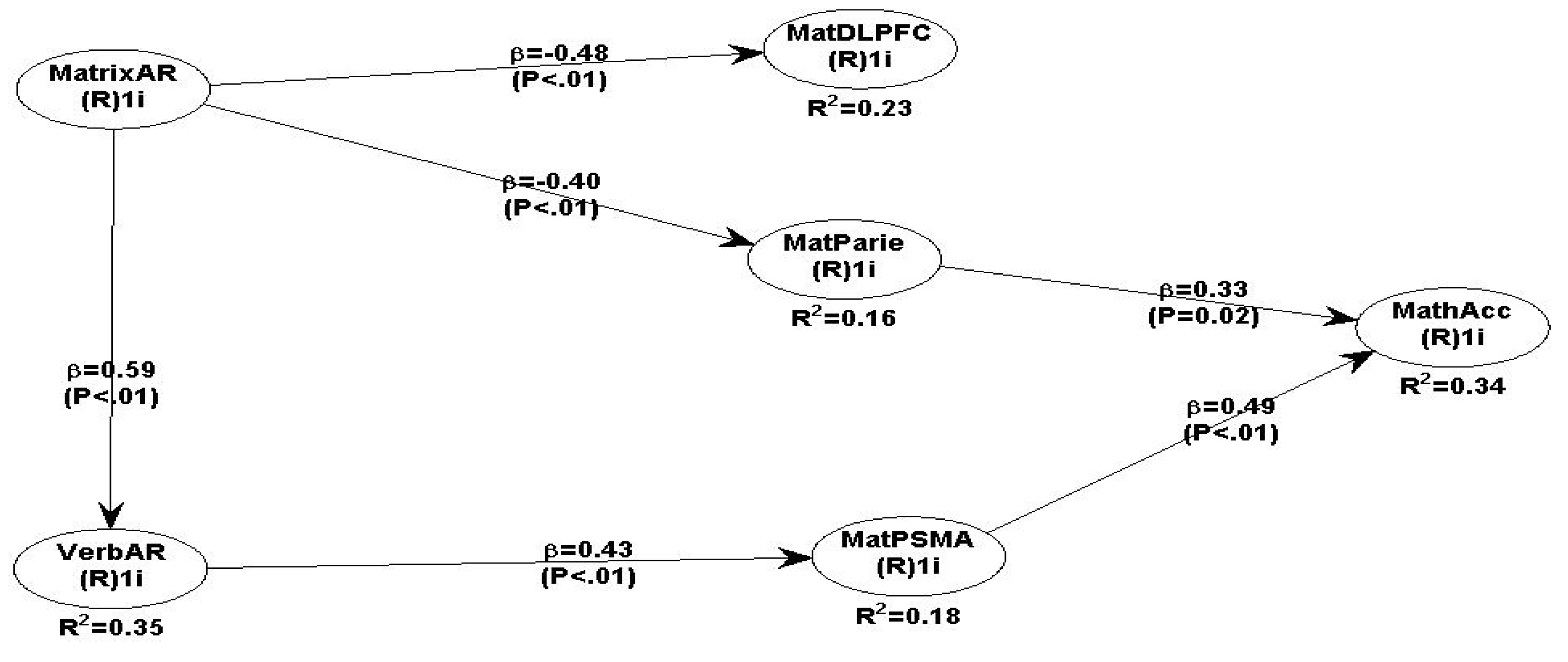

The more parsimonious maths model 4 incudes only the statistically significant path coefficients and the model fit indices have improved even more thus producing a very good fit with the data. The negative relationships between VS Matrix AR -> DLPFC (β = -0.48, P<.01) does not have any further connection with MathAcc performance and therefore it suggests that for adolescents it is deactivated, thus strongly indicating that it may be due to younger age-related brain development (Ferrer et al., 2009; Dumas et al., 2008; Dumontheil et al., 2010b). VSMatAR is also negatively related with Parietal but it is very significant (β = - 0.40, P<.01). However, the best predictors of maths accuracy are Verbal AR, which is related to PSMA (β = 0.43, P<.01), and PSMA which is related to Maths (β = 0.49, P<.01); and Parietal -> MatAcc (β = 0.33, P=0.02). The positive relationship between maths accuracy and the parietal cortex is strongly supported by other researchers who found similar relationships (Arsalidou et al., 2011; 2018; Dehaene, 2011; Dehaene et al., 2003). The strong positive relationships between PSMA and Parietal with math accuracy indicate that these two brain regions are important during the maths conceptualisation and choosing which method of analysis to utilise. Maths model 4 fit indices are all acceptable, with all path coefficients are statistically significant, robust and fitting the data very well.

Regarding the SEM model 5 for science accuracy, testing all the hypothesised brain region activations by the IVs of VS Matrix AR and Verbal AR produced mixed results. There are a few non-significant path coefficients, e.g., VSMatAR -> Parietal (β =0.14, P=0.20) and VSMatAR ->Temporal (β = 0.14, P=0.19). All brain ROI path coefficients with science are non-significant, e.g., DLPFC-> science (β =0.06, P=0.36), Parietal -> science (β = - 0.10, P=0.27), Temporal -> science (β =0.18, P=0.13) and PSMA-science (β =0.20, P=0.11). The interpretation as mentioned above, is that age related brain network development is not yet complete and therefore during science tasks they are inactive (Whitaker et al., 2018).

Interestingly, all VerbAR path coefficients with all brain ROI are statistically significant, e.g., VerbAR->DLPFC (β =0.27, P=0.04), VerbAR-> Parietal (β =0.31, P=0.02), VerbAR -> Temporal (β =0.34, P=0.01); but VerbAR -->PSMA is negative and significant (β = - 0.39, P<.01), indicating disengagement during the action of actual science task processing. Like the maths model, the relationship of science VSMatAR -> DLPFC is negative but significant (β = - 0.40, P<.01) which can be interpreted as disengagement due to lack of age-related development of the frontal brain regions (Brookman-Byrne et al., 2019; Suarez-Pellicioni, Berteletti, & Booth, 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Normally, the DLPFC is the last part of the brain regions that becomes fully developed by the age of late adolescence and early maturity (Dumontheil, 2014; Dumontheil, Houlton, Christoff & Blakemore, 2010a; Geake & Hansen, 2005; Wendelken et al., 2016). Abstract thinking about maths and science involves several brain regions including the parietal and temporal cortex and the current research findings partially support prior similar findings (Wang et al., 2020; Belkacem et al., 2020).

Fluid intelligence is also related to the DLPFC and therefore the adolescents lack of full development implies less availability of brain network connectivity indexed by lower or negative BOLD activation during maths and science thinking and novel problem solving (Heidekum, Vogel, & Grabner, 2020; Wright et al., 2007; Yuan, Voelkle & Raz, 2018). However, the general model 5 fit indices of GoF=0.413 and Symonds paradox ratio =0.846 are very good. The experimental and more parsimonious science model 6 produced slightly better path coefficients but overall, it does not provide any new insights.

In summary, the fMRI research data support some of the hypothesised science model relationships. Overall VerbAR is positively related to DLPFC, Parietal and Temporal, but negatively with PSMA. The VSMatAR is positively related to PSMA, but negatively related to DLPFC. Surprisingly, none of the four brain ROI are activated during science tasks. Regarding the maths hypothesised relationships, the findings support one hypothesis, e.g., a strong positive and significant relationship between VerbAR and PSMA, but VSMatAR is negatively related to both DLPFC and Parietal. Only two brain regions, Parietal and PSMA are positively and statistically significantly related to maths accuracy.