Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptualization of Executive Functions

1.2. Executive Function Alterations: Children at Psychosocial Risk

1.3. Executive Function Interventions: The Novel Scope of EF Training + Metacognition

1.4. Objectives

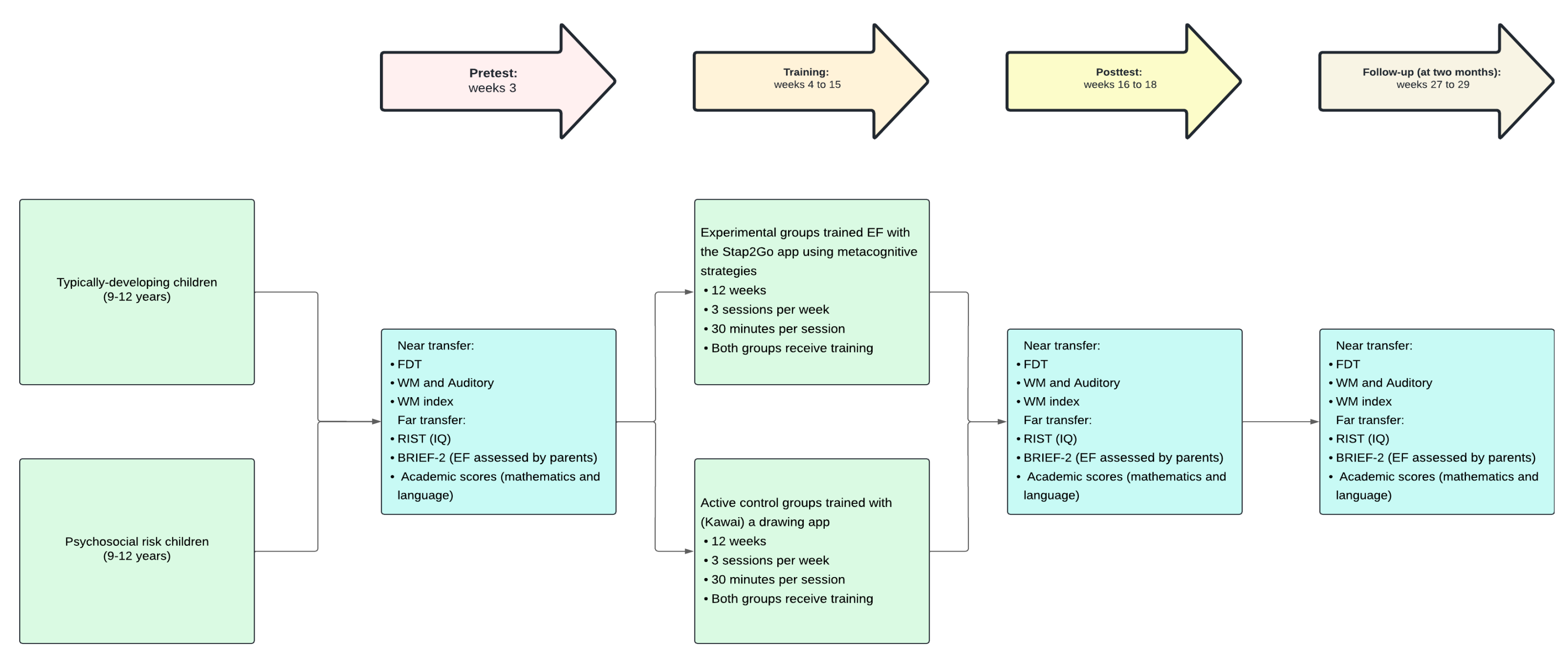

2. Materials and Methods

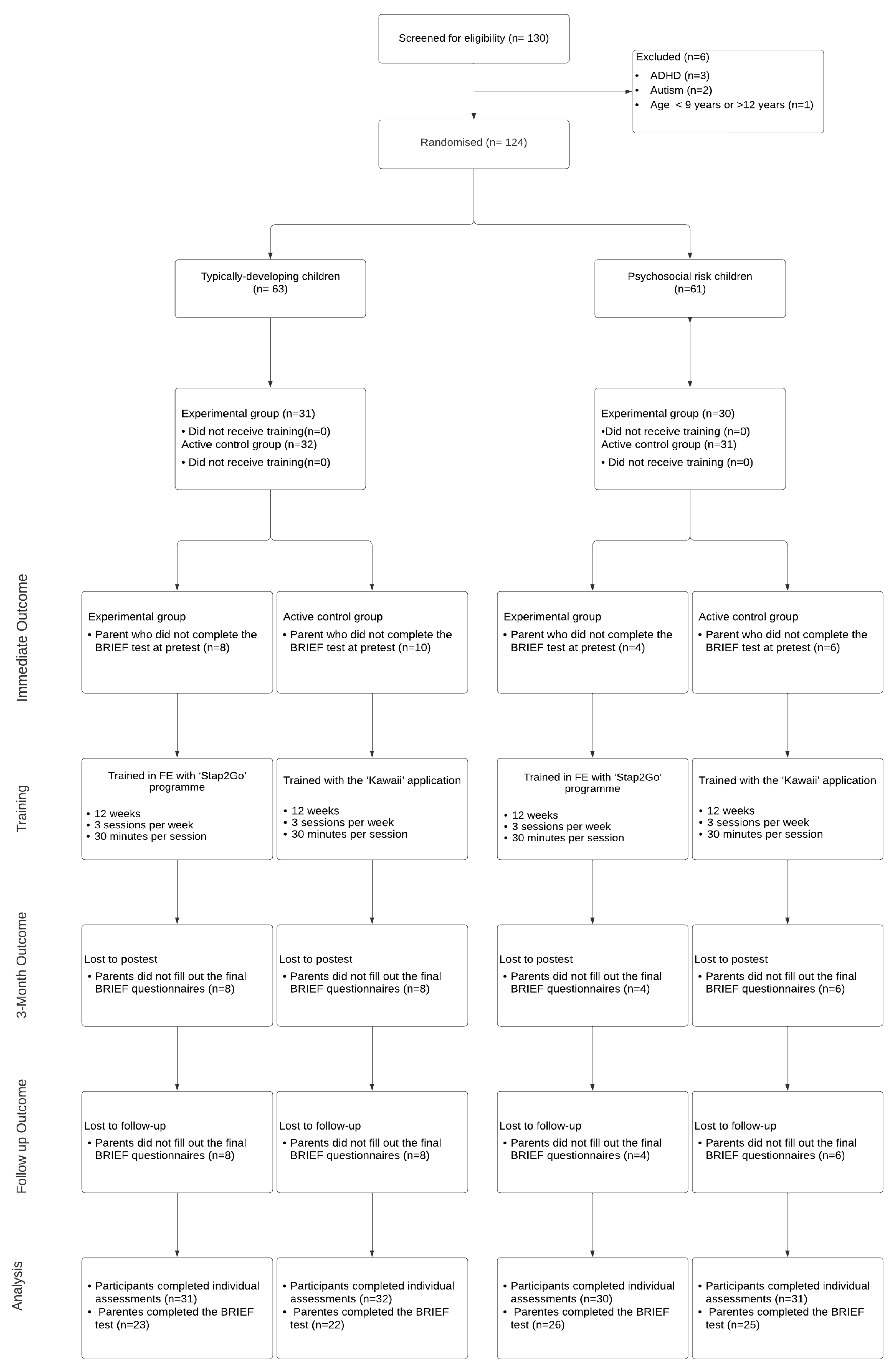

2.1. Participants

2.2. Assessments

- Questionnaire for parents created ad hoc: The questionnaire was used to collect participant data related to the inclusion criteria, filled out by the child’s legal guardian.

- Five Digit Test (FDT) (Sedó, 2007): This test provides measures of inhibition and flexibility. In the inhibition subscale, participants must count the numbers in a box instead of reading them. In the flexibility subscale, participants must change their strategy (from counting the numbers in a box to reading the numbers in it). The boxes in which the strategy is changed are marked by a blue frame. The Spearman-Brown coefficient for this test ranges from .92 to .95.

- WM sub-index of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale (WISC-V): We used the Spanish adaptation of the WISC-V for children (2014), focusing on the WM index subtests: (1) Digits, which involves repeating digits in direct, reverse, and ascending order; (2) Drawing Span, requiring participants to recall and order drawings after brief exposure; and (3) Letters and Numbers, in which participants repeat numbers in ascending order and letters alphabetically after hearing a mixed series. The Spanish adaptation for children WISC-V (2014) was applied.

- Reynold’s Brief Intelligence Test (RIST): RIST (Reynolds and Kamphaus, 2013) is a screening intelligence test that contains two subscales: Riddles, to assess verbal intelligence, and Categories, to assess non-verbal intelligence. The sum of both subscales determines an intelligence index (M = 100; SD = 15). The reliability for this test, based on Cronbach’s alpha, is .91.

- Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF-2) (Gioia et al., 2015): This standardized test for youth aged 5 to 18 focuses on assessing EF with two versions, for teachers and parents. It is a Likert-type assessment in which the parent/guardian responds regarding frequency to a series of questions. Three main indices comprise the different clinical scales: Behavioral regulation index, Emotional regulation index, and Cognitive regulation index. The Global index of executive function is made up of all three. It provides various scores related to EF, such as inhibition, flexibility, self-control, WM, and cognitive regulation. Higher scores indicate problems or difficulties (T, typical scale M = 50, SD = 10). This study used the Spanish adaptation (Gioia et al., 2017). This test has high reliability (based on Cronbach’s alpha M = .86).

- School performance: The numerical evaluations provided by the participant’s tutor in mathematics and language were used. Student’s academic performance ranges from 0 to 10.

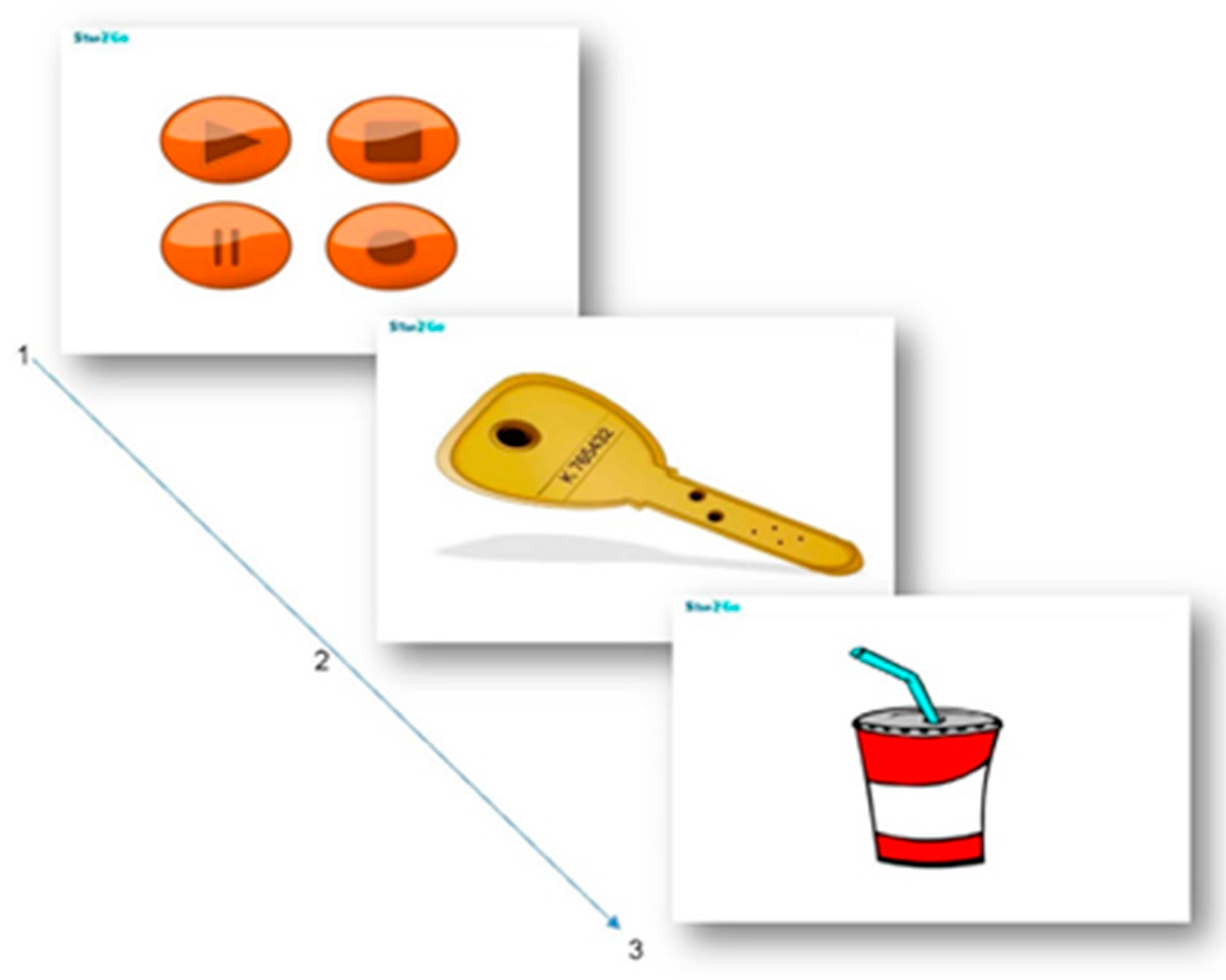

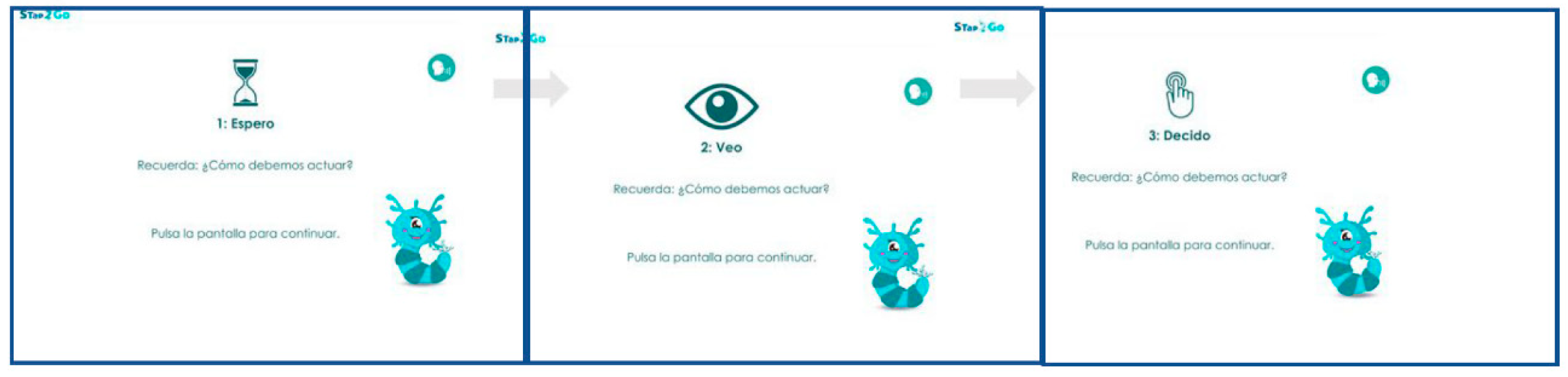

2.3. Interventions

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

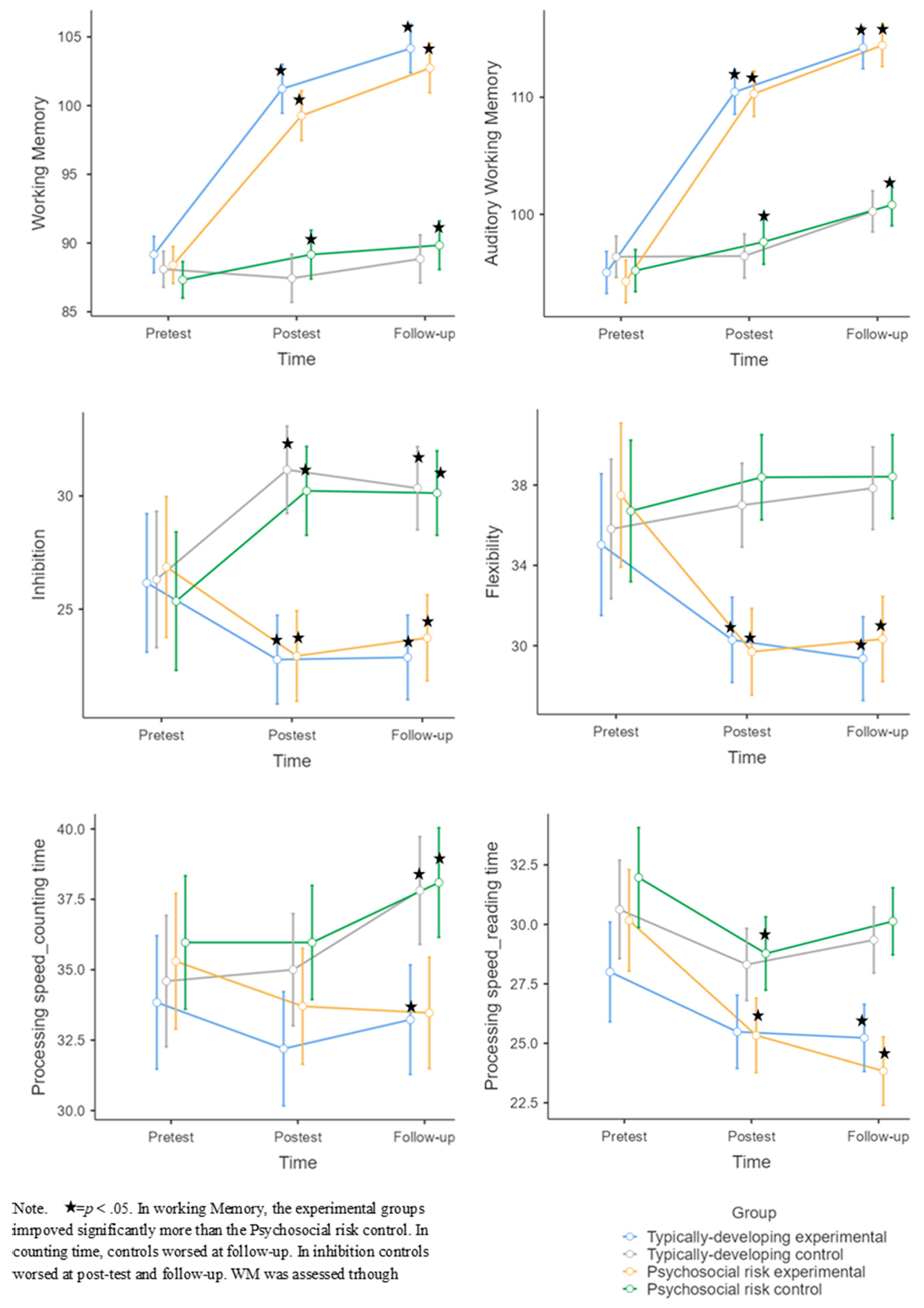

3.1. Variables Considered Near Transfer Assessed Individually

| Experimental group | Control group | ANOVA t1p-value |

Main effect (Time in each group) |

Main effect (Group/time/time*group) |

||

| WISC-V Working Memory Index | Pretest | 89.2 (4.69) | 88.1 (3.45) | .31 | Experimental: (χ2 = 52.7, p = <.001) Control: (χ2 = 5.02, p =.08) |

|

| Postest | 101.2(8.10) | 87.4 (2.34) | ||||

| Follow-up | 104.2 (7.53) | 88.8 (2.77) | ||||

| WISC-V Auditory Working Memory Index | Pretest | 95.0 (4.17) | 96.4 (5.36) | .27 | (F (1,58) = 60.75, p = <.001, η²p =.50) (F (1,58) = 4.46, p = <.014, η²p =.07) (F (1,58) = 85.55, p = <.001, η²p =.59) |

|

| Postest | 110.5 (7.39) | 96.4 (4.75) | ||||

| Follow-up | 114 (6.56) | 100 (4.45) | ||||

| FDT Inhibition | Pretest | 26.2 (8.43) | 26.3 (9.53) | .95 | (F (1,60) = 13.16, p = <.001, η²p =.18) (F (1,60) = .22, p = .81, η²p =.004) (F (1,60) = 14.96, p = <.001, η²p =.2) |

|

| Postest | 22.8 (5.96) | 31.2 (5.52) | ||||

| Follow-up | 22.9 (5.80) | 30.3 (4.49) | ||||

| Pretest | 35.0 (9.90) | 35.8 (9.44) | .75 | (F (1,60) = 11.14, p = .001, η²p =.16) (F (1,60) = .31, p = .73, η²p =.005) (F (1,60) = 9.56, p = <.001, η²p =.14) |

||

| FDT Flexibility | Postest | 30.3 (6.47) | 37.0 (6.14) | |||

| Follow-up | 29.4 (5.74) | 37.8 (6.07) | ||||

| Pretest | 33.8 (6.55) | 34.6 (5.29) | .62 | (F (1,58) = 5.80, p = .019, η²p =.08) (F(1,58) = 1.19, p = .31, η²p =.02) (F(1,58) = 5.59, p = .005, η²p =.08) |

||

| FDT Counting Time | Postest | 32.2 (4.91) | 35.0 (2.88) | |||

| Follow-up | 33.2 (5.20) | 37.8 (4.89) | ||||

| FDT Reading Time | Pretest | 28.0 (4.64) | 30.6 (5.32) | .04 | (F (1,60) = 13.22, p = <.001, η²p =.18) (F (1,60) = 1.45, p = .23, η²p =.02) (F (1,60) = 5.89, p = .018, η²p =.09) |

|

| Postest | 25.5 (3.78) | 28.3 (3.23) | ||||

| Follow-up | 25.2 (3.17) | 29.3 (3.43) | ||||

| Experimental group | Control group |

ANOVA t1p-value |

Main effect (Time in each group) |

Main effect (Group/time/time*group) |

|||

| WISC-V Working Memory Index | Pretest | 88.4 (2.92) | 87.3 (3.61) | .20 | Experimental: (χ2 = 55.9, p = <.001) Control: (χ2 = 12.7, p = .002) |

||

| Postest | 99.3 (4.28) | 89.2 (3.26) | |||||

| Follow-up | 102.7 (4.23) | 89.8 (4.15) | |||||

| WISC-V Auditory Working Memory Index | Pretest | 94.3 (5.07) | 95.2 (5.45) | .49 | (F (1,59) = 79.55, p = <.001, η²p =.58) (F (1,59) = 3.41, p = .036, η²p =.06) (F (1,59) = 80.16, p = <.001, η²p =.58) |

||

| Postest | 110.3 (4.88) | 97.6 (3.72) | |||||

| Follow-up | 114 (4.02) | 101 (4.66) | |||||

| FDT Inhibition | Pretest | 26.9 (8.37) | 25.4 (7.94) | .47 | (F (1,59) = 8.35, p = .005, η²p =.13) (F (1,59) = .77, p = 46, η²p =.01) (F (1,59) = 18.25, p = <.001, η²p =.24) |

||

| Postest | 22.9 (4.06) | 30.2 (6.20) | |||||

| Follow-up | 23.7 (5.04) | 30.1 (5.55) | |||||

| FDT Flexibility | Pretest | 37.5 (9.55) | 36.7 (10.7) | .76 | (F (1,59) = 14.42, p = <.001, η²p =.19) (F (1,59) = .41, p = .662, η²p =.007) (F (1,59) = 9.6, p = <.001, η²p =.14) |

||

| Postest | 29.7 (5.90) | 38.4 (5.28) | |||||

| Follow-up | 30.3 (5.80) | 38.4 (5.82) | |||||

| FDT Counting Time | Pretest | 35.3 (6.19) | 36.0 (8.29) | .72 | (F (1,59) = 1.74, p = .192, η²p =.03) (F (1,59) = 1.31, p = .27, η²p =.02) (F (1,59) = 6.94, p = .001, η²p =.11) |

||

| Postest | 33.7 (5.47) | 36.0 (8.26) | |||||

| Follow-up | 33.5 (5.16) | 38.1 (6.49) | |||||

| FDT Reading Time | Pretest | 30.2 (6.75) | 32.0 (6.68) | .3 | Experimental: (χ2 =25.5, p = <.001) Control: (χ2 = 11.3, p = .004) |

||

| Postest | 25.3 (3.11) | 28.8 (6.38) | |||||

| Follow-up | 23.8 (2.67) | 30.1 (5.82) | |||||

- WISC-V Working Memory Index

- WISC-V Auditory Working Memory Index

- FDT Inhibition

- FDT Flexibility

- FDT Counting Time (Processing Speed)

- FDT Reading Time (Processing Speed)

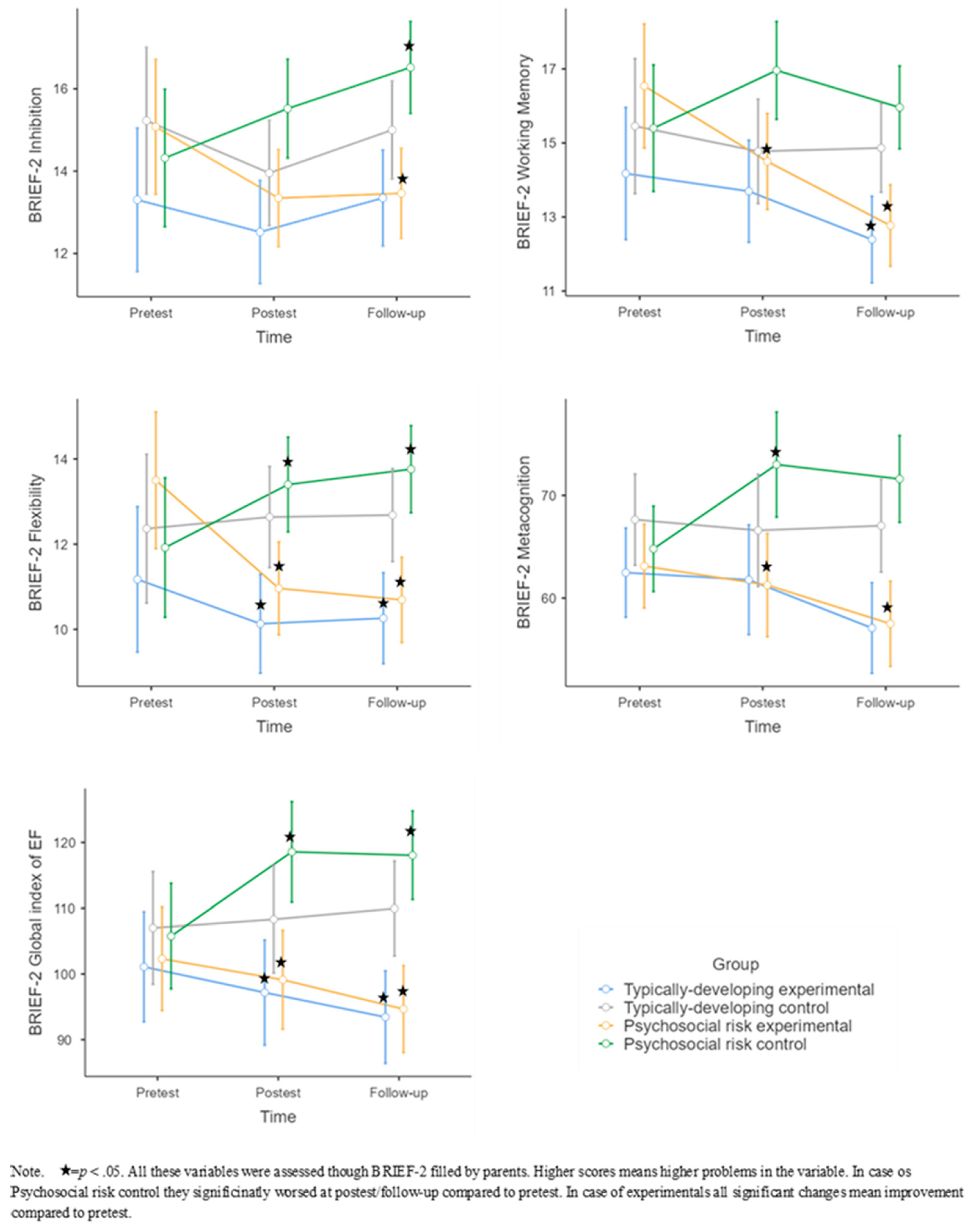

3.2. Variables Considered Transfer in Participants’ Daily Lives Were Assessed Through Parent Questionnaires

| Experimental group | Control group | ANOVA t1p-value |

Main effect (Time in each group) |

Main effect (Group/time/time*group) |

||

| BRIEF-2 Inhibition | Pretest | 13.3 (2.57) | 15.2 (3.25) | .03 | (F (1,43) = 2.64, p = .11, η²p =.59) (F (1,43) = .01, p = .92, η²p =.00) (F (1,43) =.02, p = .87, η²p =.001) |

|

| Postest | 12.5 (1.81) | 13.9 (3.03) | ||||

| Follow-up | 13.3 (1.70) | 15.0(2.68) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Flexibility | Pretest | 11.2 (2.35) | 12.4 (2.50) | .11 | Experimental: χ2 = 1.25, p =.53 Control: χ2 = .438, p = .80 |

|

| Postest | 10.1 (2.05) | 12.8 (2.80) | ||||

| Follow-up | 10.3 (1.81) | 13.0 (3.05) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Working Memory | Pretest | 14.2 (2.71) | 15.5 (2.22) | .32 | (F (1,43) = 8.84, p = .005, η²p =.17) (F (1,43) = .021, p = .98, η²p =.001) (F (1,43) = 1.43, p = .25, η²p =.033) |

|

| Postest | 13.7 (2.40) | 14.8 (3.84) | ||||

| Follow-up | 12.4 (1.34) | 15.0 (2.71) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Metacognition Index | Pretest | 62.5 (10.09) | 67.6 (9.62) | .09 | (F (1,43) = 7.50, p = .009, η²p =1.52) (F (1,43) = .37, p = .7, η²p =.009) (F (1,43) = 1.55, p = .22, η²p =.04) |

|

| Postest | 61.8 (11.7) | 66.9 (14.5) | ||||

| Follow-up | 57.1 (6.86) | 67.6 (11.20) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Global Index of Executive Function | Pretest | 101 (15.9) | 107 (25.6) | .36 | Experimental: (χ2 =11.9, p =.003) Control: (χ2 =.67, p =.72) |

|

| Postest | 97.2 (14.2) | 109.0 (20.9) | ||||

| Follow-up | 93.4 (9.55) | 111.0 (17.70) |

| Psychosocial risk experimental group (PRE) | Psychosocial risk control group (PRC) | ANOVA t1p-value |

Main effect (Time in each group) |

Main effect (Group/time/time*group) |

||

| BRIEF-2 Inhibition | Pretest | 15.1 (6.23) | 14.3 (3.50) | .59 | Experimental: (χ2 = 4.10, p =.13) Control: (χ2 = 6.74, p = .03) |

|

| Postest | 13.3 (3.22) | 15.5 (3.68) | ||||

| Follow-up | 13.5 (2.73) | 16.5 (3.64) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Flexibility | Pretest | 13.5 (6.54) | 11.9 (3.17) | .28 | Experimental: (χ2 = 4.88, p = .08) Control: (χ2 = 10.2, p = .006) |

|

| Postest | 11.0 (2.96) | 13.4 (3.15) | ||||

| Follow-up | 10.7 (2.54) | 13.8 (2.85) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Working Memory | Pretest | 16.5 (7.15) | 15.4 (2.63) | .45 | Experimental: (χ2 = 18.0, p = <.001) Control: (χ2 = 2.04, p = .36) |

|

| Postest | 14.5 (3.54) | 17.0 (3.55) | ||||

| Follow-up | 12.8 (2.94) | 16.0 (3.81) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Metacognition Index | Pretest | 63.1 (10.86) | 64.8 (11.16) | .58 | (F (1,46) = 9.78, p = .003, η²p = .17) (F (1,46) = 1.63, p = .202, η²p = .033) (F (1,46) = 9.52, p = <.001, η²p = .17) |

|

| Postest | 61.3 (11.9) | 73.0 (13.9) | ||||

| Follow-up | 57.5 (9.70) | 71.6 (14.12) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Global Index of ExecutiveFunction | Pretest | 102 (19.4) | 106 (19.3) | .53 | (F (1,46) = 9.93, p = .003, η²p = .17) (F (1,46) =1.28, p = .282, η²p = .026) (F (1,46) = 9.34, p = <.001, η²p = .16) |

|

| Postest | 99.1 (19.1) | 118.6 (22.2) | ||||

| Follow-up | 94.7 (15.93) | 118.0 (22.62) |

- BRIEF-2 Inhibition

- BRIEF-2 Flexibility

- BRIEF-2 Working Memory

- BRIEF-2 Metacognition Index

- BRIEF-2 Global Index of Executive Function

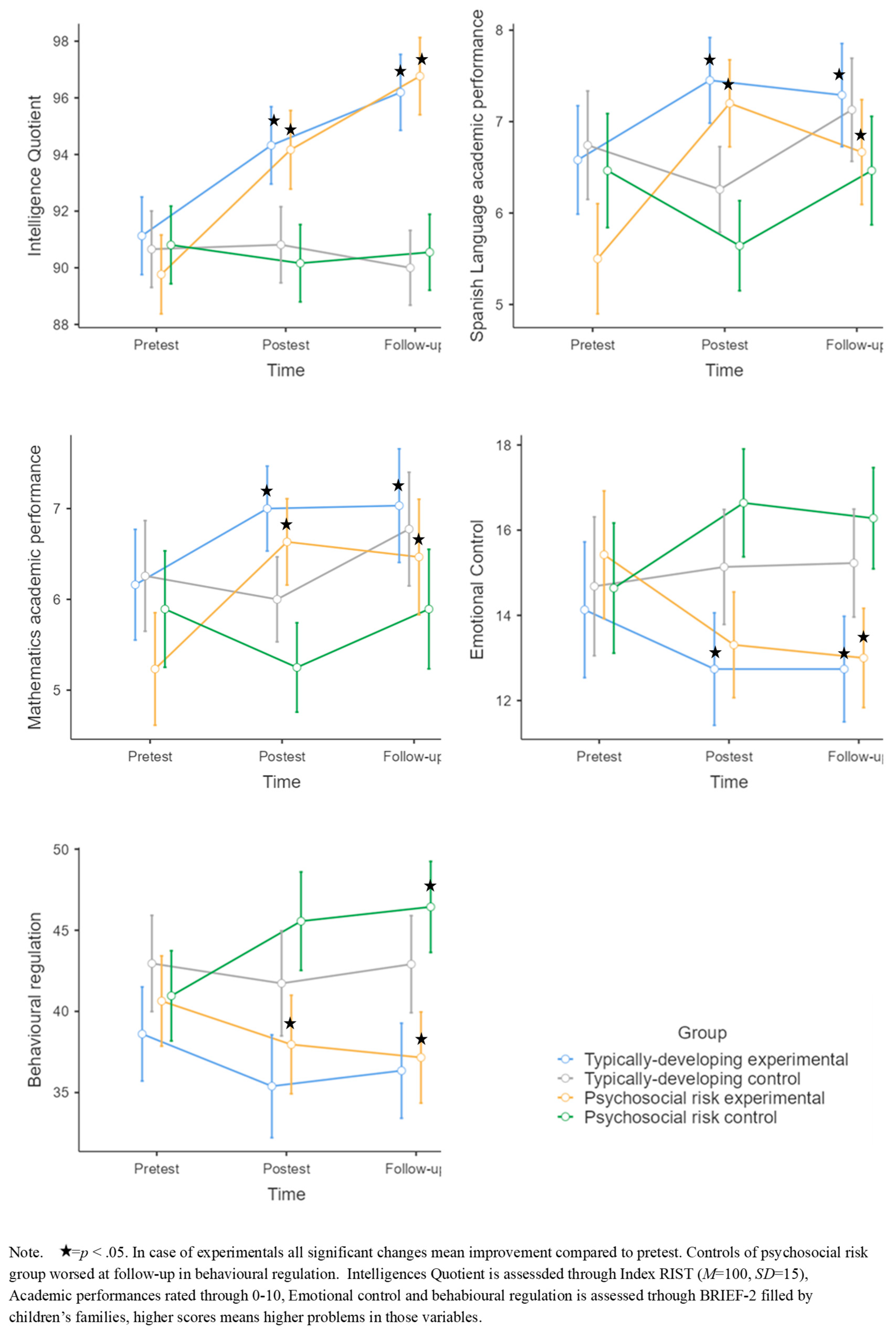

3.3. Variables Considered Far Transfer (Not Directly Trained)

| Experimental group | Control group | ANOVA t1p-value |

Main effect (Time in each group) |

Main effect (Group/time/time*group) |

||

| RIST Intelligence Index | Pretest | 91.1 (4.76) | 90.7 (3.70) | .66 | Experimental: (χ2 = 32.1, p = <.001) Control: (χ2 = 1.1, p = <.57) |

|

| Postest | 94.3 (5.06) | 90.8 (3.17) | ||||

| Follow-up | 96.2 (5.36) | 90.0 (2.62) | ||||

| Spanish Language academic performance | Pretest Postest Follow-up |

6.58 (1.52) 7.45 (1.39) 7.29 (1.49) |

6.74 (2.18) 6.31 (1.53) 7.19 (1.71) |

.74 | (F (1,60) = 1.66, p = .020, η²p = .03) (F (1,60) = 2.41, p = .094, η²p = .04) (F (1,60) = 17.08, p = <.001, η²p = .22) |

|

| Mathematics academic performance | Pretest | 6.16 (1.55) | 6.26 (2.16) | .84 | (F (1,60) = 1.2, p = .28, η²p = .02) (F (1,60) = .78, p = .46, η²p = .013) (F (1,60) = 9.57, p = <.001, η²p = .14) |

|

| Postest | 7.00 (1.13) | 6.06 (1.58) | ||||

| Follow-up | 7.03 (1.60) | 6.84 (1.89) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Emotional Control | Pretest | 14.1 (2.97) | 14.7 (2.66) | .51 | (F (1,43) = 10.47, p = .002, η²p= .20) (F (1,43) = .18, p = .83, η²p= .004) (F (1,43) = 3.97, p = <.023, η²p= .09) |

|

| Postest | 12.7 (1.39) | 15.4 (2.84) | ||||

| Follow-up | 12.7 (1.60) | 15.5 (2.92) | ||||

| BRIEF-2 Behavioral Regulation Index | Pretest | 38.6 (6.60) | 43.0 (6.47) | .03 | (F (1,43) = 10.34, p = .003, η²p =.20) (F (1,43) = 1.12, p = .29, η²p =.03) (F (1,43) = .01, p = .93, η²p =.00) |

|

| Postest | 35.4 (3.38) | 42.1 (7.47) | ||||

| Follow-up | 36.3 (3.51) | 43.5 (7.29) |

| Experimental group | Control group | ANOVA t1p-value |

Main effect (Time in each group) |

Main effect (Group/time/time*group) |

||

| RIST Intelligence Index | Pretest | 89.8 (3.22) | 90.0 (3.53) | .23 | (F (1,59) = 20.53, p = <.001, η²p =.26) (F (1,59) = .44, p = .64, η²p =.01) (F (1,59) = 47.47, p = <.001, η²p =.45) |

|

| Postest | 94.2 (4.04) | 90.2 (2.68) | ||||

| Follow-up | 96.8 (3.54) | 90.5 (3.00) | ||||

| Spanish Language academic performance | Pretest | 5.50 (1.61) | 6.46 (1.14) | .01 | (F (1,59) = 74.22, p = <.001, η²p = .58) (F (1,59) = .26, p = .61, η²p = .005) (F (1,59) = 37.86, p = <.001, η²p = .41) |

|

| Postest | 7.20 (1.24) | 5.61 (1.28) | ||||

| Follow-up | 6.67 (1.60) | 6.39 (1.56) | ||||

| Mathematics academic performance | Pretest Postest Follow-up |

5.23 (1.65) 6.63 (1.35) 6.47 (1.74) |

5.89 (1.34) 5.32 (1.30) 5.90 (1.85) |

.10 | (F (1,59) = 1.65, p = .20, η²p = .03) (F (1,59) = 1.41, p = .25, η²p = .02) (F (1,59) = 24.12, p = <.001, η²p = .31) |

|

| BRIEF-2 Emotional Control | Pretest Postest Follow-up |

15.4 (5.55) 13.3 (3.07) 13.0 (2.68) |

14.6 (3.21) 16.6 (4.53) 16.3 (4.16) |

.54 | Experimental: (χ2 = 40.5, p=<.001) Control: (χ2 = 2.05, p = .36) |

|

| BRIEF-2 Behavioral Regulation Index | Pretest Postest Follow-up |

40.8 (5.61) 37.8 (8.14) 37.2 (6.97) |

41.0 (8.76) 45.6 (9.56) 46.4 (9.12) |

.12 | (F (1,46) = 8.12, p = .006, η²p = .15) (F (1,46) = 2.03, p = .14, η²p = .041) (F (1,46) = 9.97, p = <.001, η²p = .17) |

- RIST Intelligence Index

- Spanish Language Academic Performance

- Mathematics Academic Performance

- BRIEF-2 Emotional Control

- BRIEF-2 Behavioral Regulation Index

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EF | Executive Functions |

| WM | Working Memory |

References

- Andrés, M. L., Richaud de Minzi, M. C., Castañeiras, C., Canet-Juric, L. & Rodríguez-Carvajal, R. (2016). Neuroticism and depression in children: The role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 177(2), 55–71. [CrossRef]

- Ardila, A., Pineda, D., & Rosselli, M. (2000). Correlation between intelligence test scores and executive function measures. Archives of clinical neuropsychology, 15(1), 31-36. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R., & Jones, S. M. (2019). An integrated model of regulation for applied settings. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22(1), 2–23. [CrossRef]

- Barreyro, J. P., Injoque-Ricle, I., Formoso, J. & Burin, D. I. (2017). The role of working memory and sustained attention in the generation of explanatory inferences. Liberabit, 23(2), 235–247. [CrossRef]

- Best, J. R., Miller, P. H., & Naglieri, J. A. (2011). Relations between executive function and academic achievement from ages 5 to 17 in a large, representative national sample. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 327–336. [CrossRef]

- Bosanquet, P. & Radford, J. (2019). Teaching assistant and pupil interactions: The role of repair and topic management in scaffolding learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(1), 177–190. [CrossRef]

- Brocki, K. C., & Bohlin, G. (2004). Executive functions in children aged 6 to 13: A dimensional and developmental study. Developmental neuropsychology, 26(2), 571-593. [CrossRef]

- Camuñas, N., Mavrou, I., Vaíllo, M. & Martínez, R. M. (2022). An executive function training programme to promote behavioural and emotional control of children and adolescents in foster care in Spain. Trends in neuroscience and education, 27, 100175. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S. M., & Moses, L. J. (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children's theory of mind. Child development, 72(4), 1032-1053. [CrossRef]

- Cassandra, B. & Reynolds, C. (2005). A Model of the Development of Frontal Lobe Functioning: Findings From a Meta-Analysis. Applied Neuropsychology, 12 (4), 190–201. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cole, K., & Mitchell, P. (2000). Siblings in the development of executive control and a theory of mind. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(2), 279-295. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S. K., & Chan, W. W. L. (2022). The roles of different executive functioning skills in young children’s mental computation and applied mathematical problem-solving. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 40(1), 151-169. [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, N., & Blaye, A. (2016). Metacognitive monitoring of executive control engagement during childhood. Child Development, 87 (4), 1264–1276. [CrossRef]

- Crawford C., Macmillan L. & Vignoles A. (2017). When and why do initially high-achieving poor children fall behind? Oxford Review of Education, 43 (1), pp. 88 –108. [CrossRef]

- Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological bulletin, 115(1), 74. [CrossRef]

- Dajani, D. R., & Uddin, L. Q. (2015). Demystifying cognitive flexibility: Implications for clinical and developmental neuroscience. Trends In Neurosciences, 38(9), 571–578. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M. C., Amso, D., Anderson, L. C. & Diamond, A. (2006). Development of cognitive control and executive functions from 4 to 13 years: Evidence from manipulations of memory, inhibition, and task switching. Neuropsychologia, 44(11), 2037–2078. [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C. R., Wood, S. J., Anderson, V., Buchanan, J., Proffitt, T. M., Mahony, K., y Pantelis, C. (2003). Normative data from the CANTAB. I: Development of executive function over the lifespan. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 25(2), 242-254. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135–168. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. & Ling, D. S. (2019). Review of the evidence on, and fundamental questions about, efforts to improve executive functions, including working memory. In J. M. Novick, M. F. Bunting, M. R. Dougherty, & R. W. Engle (Eds.), Cognitive and working memory training: perspectives from psychology, neuroscience, and human development (pp. 143–431). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A., Barnett, W. S., Thomas, J. & Munro, S. (2007). Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science, 318(5855), 1387–1388. [CrossRef]

- Doebel, S. (2020). Rethinking executive function and its development. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(4), 942–956. [CrossRef]

- Doebel, S., Dickerson, J. P., Hoover, J. D., & Munakata, Y. (2018). Using language to get ready: Familiar labels help children engage proactive control. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166, 147–159. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K. & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2015). Children and socioeconomic status. In M. H. Bornstein, T. Leventhal, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: ecological environments and processes (7th ed., pp. 534–573). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Engle, P. L., & Black, M. M. (2008). The effect of poverty on child development and educational outcomes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136, 243–256. [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A. (2009). The role of metacognitive experiences in the learning process. Psicothema, 21(1), 76–82. https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8799.

- Ferguson, H. J., Brunsdon, V. E., & Bradford, E. E. (2021). The developmental trajectories of executive function from adolescence to old age. Scientific reports, 11(1), 1382. [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Frick, M. A., Forslund, T., Fransson, M., Johansson, M., Bohlin, G. & Brocki, K. C. (2017). The role of sustained attention, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament in the development of early self-regulation. British Journal Of Psychology, 109(2), 277–298. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. P., & Miyake, A. (2017). Unity and diversity of executive functions: Individual differences as a window on cognitive structure. Cortex, 86, 186–204. [CrossRef]

- Friedman N. P., Miyake, A., Corley, R. P., Young, S. E., DeFries, J. C., & Hewitt, J. K. (2006). Not All Executive Functions Are Related to Intelligence. Psychological Science, 17(2), 172–179. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. P., Miyake, A., Young, S. E., DeFries, J. C., Corley, R. P., & Hewitt, J. K. (2008). Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of experimental psychology: General, 137(2), 201–225. [CrossRef]

- Fuster, J. M. (2001). The prefrontal cortex--an update: time is of the essence. Neuron, 30(2), 319–333. [CrossRef]

- Gagne, J. R., Liew, J., & Nwadinobi, O. K. (2021). How does the broader construct of self-regulation relate to emotion regulation in young children?. Developmental Review, 60, Article 100965. [CrossRef]

- Stap2Go S.L. (2022). Stap2Go (1.3.0) [App]. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.GeneticAI.STap2Go&hl=es_419&gl=US).

- Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C. & Kenworthy, L. (2015). Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function, Second Edition (BRIEF-2). Psychological Assessment Resources. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, E. (2001). The executive brain: Frontal lobes and the civilized mind. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children's self-regulation and competence in school. Journal of educational psychology, 81(2), 143–154. [CrossRef]

- Hackman, D. A., Farah, M. J. & Meaney, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 11(9), 651–659. [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press.

- Hofmann, W., Schmeichel, B. J. & Baddeley, A. (2012). Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(3), 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Isquith, P. Κ., Gioia, G. A. & Espy, K. A. (2004). Executive Function in Preschool Children: Examination Through Everyday Behavior. Developmental Neuropsychology, 26(1), 403–422. [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, L. B., & Stifter, C. A. (2008). Individual differences in preschoolers' self-regulation and theory of mind. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54(1), 125–150. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, L., Astiz, D., Hidalgo, V., & Contín, M. (2019). Ensuring respect for at-risk children’s rights. Lessons learned from home-and group-based family education programs. In L. Moran & J. Canavan (Eds.), Realising children’s rights through supporting parents (pp. 43–60). UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre. https://cdn.flipsnack.com/widget/v2/widget.html?hash=ftkarl897.

- Johann, V. E., & Karbach, J. (2020). Effects of game-based and standard executive control training on cognitive and academic abilities in elementary school children. Developmental science, 23(4), e12866. [CrossRef]

- Johann, V., Könen, T., & Karbach, J. (2019). The unique contribution of working memory, inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and intelligence to reading comprehension and reading speed. Child Neuropsychology, 26(3), 324–344. [CrossRef]

- Jolles, D. D., & Crone, E. A. (2012). Training the developing brain: a neurocognitive perspective. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 6, 76. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. M., Bailey, R., Barnes, S. P., & Partee, A. (2016). Executive Function Mapping Project: Untangling the terms and skills related to executive function and self-regulation in early childhood. (Issue October). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/efmapping_report_101416_final_508.pdf.

- Jones, J. S., Milton, F., Mostazir, M., & Adlam, A. R. (2020). The academic outcomes of working memory and metacognitive strategy training in children: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Developmental science, 23(4), e12870. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R. M., & Tager–Flusberg, H. (2004). The relationship of theory of mind and executive functions to symptom type and severity in children with autism. Development and psychopathology, 16(1), 137-155. [CrossRef]

- Karbach, J. & Unger, K. (2014).Executive Control training from middle childhood to adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B., & Luna, B. (2018). Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 94, 179–195. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L. R., Lopez, R. A., Hunt, R. H., Hodel, A. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Thomas, K. M. (2024). Impacts of early deprivation on behavioral and neural measures of executive function in early adolescence. Brain and cognition, 179, 106183. [CrossRef]

- Lipina, S. J., Hermida, M. J., Segretin, M. S., Prats, L., Fracchia, C. & Colombo, J. A. (2011). Childhood poverty and cognitive development: a review from developmental neuroscience. Argentine Journal of Public Health, 2(6), 25–37.

- Liu, Q., Zhu, X., Ziegler, A. & Shi, J. (2015). The effects of inhibitory control training for preschoolers on reasoning ability and neural activity. Scientific reports, 5, 14200. [CrossRef]

- Lozano Gutiérrez, A. & Ostrosky F. (2011). Development of Executive Functions and the Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychology, Neuropsychiatry and Neurosciences Journal, 11(1), 159–172.

- Manfra, L., Davis, K. D., Ducenne, L., & Winsler, A. (2014). Preschoolers’ motor and verbal self-control strategies during a resistance-to-temptation task. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 175(4), 332–345. [CrossRef]

- Marcovitch, S. & Zelazo, P. D. (2009). A hierarchical competing systems model of the emergence and early development of executive function. Developmental science, 12(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Martins, M., Pinto, R., Živković, M. & Jiménez, L. (2024). Parenting Competences Among Migrant Families Living at Psychosocial Risk in Spain. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 25(2), 737–758. [CrossRef]

- Marulis, L. M., Baker, S. T., & Whitebread, D. (2020). Integrating metacognition and executive function to enhance young children’s perception of and agency in their learning. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 50, 46–54. [CrossRef]

- Melby-Lervåg M, Redick TS, & Hulme C (2016). Working memory training does not improve performance on measures of intelligence or other measures of “far transfer”: Evidence from a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 512–534. [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. L., & Cummings, J. L. (Eds.). (2017). The human frontal lobes: Functions and disorders. Guilford Publications.

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A., Howerter, A. & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., & Friedman, N. P. (2012). The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(1), 8–14. [CrossRef]

- Moraine, P. (2014). The student's executive functions. Improving attention, memory, organisation and other functions to facilitate learning. Narcea.

- Morgan, A. B. & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2000). A meta-analytic review of the relation between antisocial behavior and neuropsychological measures of executive function. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(1), 113–136. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A. B. & Chein, J. (2011). Does working memory training work? The promise and challenges of enhancing cognition by training working memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(1), 46–60. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T. O. (1990). Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings. Psychology of learning and motivation, 26, 125–173). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1994). Metacognition: Knowing about knowing. In J. Metcalfe & A. P. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 1–25). The MIT Press. [CrossRef]

- Niebaum, J.C., & Munakata, Y. (2022). Why Doesn't Executive Function Training Improve Academic Achievement? Rethinking Individual Differences, Relevance, and Engagement from a Contextual Framework. Journal of Cognition and Development, 24(2), 241–259. [CrossRef]

- Oberste, M., Javelle, F., Sharma, S., Joisten, N., Walzik, D., Bloch, W. & Zimmer, P. (2019). Effects and Moderators of Acute Aerobic Exercise on Subsequent Interference Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2616. [CrossRef]

- Obonsawin, M. C., Crawford, J. R., Page, J. M., Chalmers, P., Cochrane, R. H. B. & Low, G. (2002). Performance on tests of frontal lobe function reflect general intellectual ability. Neuropsychologia, 40(7), 970–977. [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, K., & Hisasaka, T. (2018). Beyond intelligence: A meta-analytic review of the relationship among metacognition, intelligence, and academic performance. Metacognition and Learning, 13(2), 179–212. [CrossRef]

- Peng, P., Namkung, J., Barnes, M., & Sun, C. Y. (2015). A meta-analysis of mathematics and working memory: Moderating effects of working memory domain, type of mathematics skill, and sample characteristics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 455e473. [CrossRef]

- Pennington, B. F. & Ozonoff, S. J. (1996). Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37(1), 51–87. [CrossRef]

- Perone, S., Simmering, V. R., & Buss, A. T. (2021). A dynamical reconceptualization of executive-function development. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1198–1208. [CrossRef]

- Piu Piu Apps (2023). Kawaii Paint Gradient (1.4.2 Version) [App].https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.piupiuapps.coloringgradientkawaii&hl=es_CR.

- Rodrigo, M.J., Byrne, S., & Álvarez, M. (2011). Preventing child maltreatment through parenting programmes implemented at the local social services level. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(1), 89–103. [CrossRef]

- Pozuelos, J. P., Cómbita, L. M., Abundis, A., Paz-Alonso, P. M., Conejero, Á., Guerra, S. & Rueda, M. R. (2018). Metacognitive scaffolding boosts cognitive and neural benefits following executive attention training in children. Developmental Science, 22(2), e12756. [CrossRef]

- Reder, L. M., & Schunn, C. D. (2014). Metacognition does not imply awareness: Strategy choice is governed by implicit learning and memory. In Implicit memory and metacognition (pp. 45–77). Psychology Press.

- Reynolds, C. R. & Kamphaus, R. W. (2013). RIAS and RIST Manual. Spanish adaptation. TEA Editions.

- Riccio, C. A., Hewitt, L. L. & Blake, J. J. (2011). Relationship of measures of executive function with aggressive behavior in children. Applied Neuropsychology, 18 (1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Richland, L. E., & Burchinal, M. R. (2013). Early Executive Function Predicts Reasoning Development. Psychological Science, 24(1), 87–92. [CrossRef]

- Roebers, C. M. (2017). Executive function and metacognition: Towards a unifying framework of cognitive self-regulation. Developmental Review, 45, 31–51. [CrossRef]

- Roebers, C. M., & Feurer, E. (2016). Linking executive functions and procedural metacognition. Child Development Perspectives, 10(1), 39–44. [CrossRef]

- Rosselli, M., Matute, E. & Jurado, M.B. (2008). Executive functions throughout life. Neuropsychology, Neuropsychiatry and Neurosciences Journal, 8, 23–46.

- Rossignoli-Palomeque, T., Pérez-Hernandez, E. & González-Marqués, J. (2020). Training effects of attention and EF strategy-based training “Nexxo” in school-age students. Acta Psychologica, 210, 103174. [CrossRef]

- Rossignoli-Palomeque, T., Pérez-Hernández, E. & González-Marqués, J. (2018). Brain training in children and adolescents: Is it scientifically valid? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 565. [CrossRef]

- Rossignoli-Palomeque, T., Quirós-Godoy, M., Perez-Hernandez, E., & González-Marqués, J. (2019). Schoolchildren's compensatory strategies and skills in relation to attention and executive function app training. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2332. [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M. R., Posner, M. I. & Rothbart, M. K. (2005). The development of executive attention: Contributions to the emergence of self-regulation. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28(2), 573–594. [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, M. A., Xu, F., Carlson, S. M., Moses, L. J., & Lee, K. (2006). The Development of Executive Functioning and Theory of Mind: A Comparison of Chinese and U.S. Preschoolers. Psychological Science, 17(1), 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Sala, G., & Gobet, F. (2019). Cognitive training does not enhance general cognition. Trends in cognitive sciences, 23(1), 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, S. (2016). Influence of parenting style on children's behaviour. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 3(2). [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H., Daseking, M., Gawrilow, C., Karbach, J. & Kerner Auch Koerner J. (2022). Self-regulation in preschool: Are executive function and effortful control overlapping constructs? Dev Sci., 25(6):e13272. [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, K., Mulder, H., Deković, M. & Matthys, W. (2012). Executive Functions in Preschool Children with Externalizing Behavior Problems: A Meta-Analysis. Journal Of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(3), 457–471. [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P. H., Krupp, S. & Howland, S. (2013). Strategic leadership: The essential skills. Harvard business review, 91(1-2). 131–4, 147.

- Sedó, M. (2007). Five Digit Test. TEA Ediciones.

- Séguin, J. R. (2009). The frontal lobe and aggression. European Journal Of Developmental Psychology, 6(1), 100–119. [CrossRef]

- Séguin, J. R., Boulerice, B., Harden, P. W., Tremblay, R. E. & Pihl, R. O. (1999). Executive functions and physical aggression after controlling for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, general memory, and IQ. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(8), 1197–1208. [CrossRef]

- Semrud-Clikeman, M. & Bledsoe, J. (2011). Updates on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Learning Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 13(5), 364–373. [CrossRef]

- Shimamura AP. (2000). Toward a cognitive neuroscience of metacognition. Conscious Cogn., 9(2), 313–323. [CrossRef]

- Shin, M., & Brunton, R. (2024). Early life stress and mental health—Attentional bias, executive function and resilience as moderating and mediating factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 221, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Shore, R. (1997). Rethinking the Brain: New Insights Into Early Development. Families and Work Institute.

- Simons, D. J., Boot, W. R., Charness, N., Gathercole, S. E., Chabris, C. F., Hambrick, D. Z., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. (2016). Do “brain-training” programs work?. Psychological science in the public interest, 17(3), 103–186. [CrossRef]

- Smid, C. R., Karbach, J., & Steinbeis, N. (2020). Toward a science of effective cognitive training. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(6), 531–537. [CrossRef]

- Sroufe, L. A. (2000). Emotional development: the organization of emotional life in the early years. Cambridge University Press.

- Strobach, T. & Karbach, J. (2021). Cognitive Training. An Overview of Features and Applications (second edition). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Stuss D. T. (2011). Functions of the frontal lobes: relation to executive functions. Journal of the International Neuropsychological. Society: JINS, 17(5), 759–765. [CrossRef]

- Tamm, L., & Nakonezny, P. A. (2015). Metacognitive executive function training for young children with ADHD: a proof-of-concept study. Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders, 7(3), 183–190. [CrossRef]

- Takacs, Z. K. & Kassai, R. (2019). The efficacy of different interventions to foster children’s executive function skills: a series of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 145(7), 653–697. [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. (2022). Jamovi (Version 2.3.24) [Software]. https://www.jamovi.org.

- Titz, C. & Karbach, J. (2014). Working memory and executive functions: Effects of training on academic achievement. Psychological Research, 78(6), 852–868. [CrossRef]

- Waber, D. P., Gerber, E., Turcios, V. Y., Wagner, E. R. & Forbes, P. (2006). Executive Functions and performance on High-Stakes testing in children from urban schools. Developmental Neuropsychology, 29(3), 459–477. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Li, C., Ren, X., & Schweizer, K. (2021). How executive processes explain the overlap between working memory capacity and fluid intelligence: A test of process overlap theory. Journal of Intelligence, 9(2), 2 . [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. (2015). WISC-V. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-V. Pearson.

- Wood, D., Bruner, J. S. & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100. [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, H., Aber, J. L., & Beardslee, W. R. (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: implications for prevention. The American psychologist, 67(4), 272–284. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D. & Carlson, S. M. (2012). Hot and Cool Executive Function in Childhood and Adolescence: Development and Plasticity. Child Development Perspectives, 6(4), 354–360. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D., Craik, F. I. M. & Booth, L. (2004). Executive function across the life span. Acta Psychologica, 115(2-3), 167–183. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D., Qu, L., & Kesek, A. C. (2010). Hot executive function: Emotion and the development of cognitive control. In S. D. Calkins & M. A. Bell (Eds.), Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition (pp. 97–111). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D., Qu, L., & Müller, U. (2005). Hot and cool aspects of executive function: Relations in early development. In W. Schneider, R. Schumann-Hengsteler, & B. Sodian (Eds.), Young children's cognitive development: Interrelationships among executive functioning, working memory, verbal ability, and theory of mind (pp. 71–93). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Zhao, X., Chen, L. & Maes, J. H. R. (2018). Training and transfer effects of response inhibition training in children and adults. Developmental Science, 95(T), eTWsTT. [CrossRef]

- Zuber, S., Joly-Burra, E., Mahy, C.E.V., Loaiza, V., & Kliegel, M. (2022). Are facet-specific task trainings efficient in improving children's executive functions, and why (they might not be)? A multi-facet latent change score approach. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 227, 105602. [CrossRef]

| RIST | Gender F/M | Age | ||

| Pretest | Typically-developing experimental group | 91.1 (4.76) | 14/17 | 133 (12.9) |

| Typically-developing control group | 90.7 (3.70) | 12/20 | 131 (6.96) | |

| Psychosocial risk experimental group | 89.8 (3.22) | 14/16 | 135 (8.76) | |

| Psychosocial risk control group | 90.8 (3.53) | 21/10 | 133 (10.3) | |

| F(3.120) | 0.69 (p = .057) |

1.13 (p = .34) |

||

| Postest | Typically-developing experimental group | 94.3 (5.06) | 14/17 | 136 (12.9) |

| Typically-developing control group | 90.8 (3.17) | 12/20 | 135 (6.96) | |

| Psychosocial risk experimental group | 94.2 (4.04) | 14/16 | 138 (8.75) | |

| F(3.120) | 10.1 (p = < .001) |

1.14 | ||

| Follow-up | Typically-developing experimental group | 96.2 (5.36) | 14/17 | 140 (12.9) |

| Typically-developing control group | 90.0 (2.62) | 12/20 | 138 (6.94) | |

| Psychosocial risk experimental group | 96.8 (3.54) | 14/16 | 142 (8.76) | |

| Psychosocial risk control group | 90.5 (3.00) | 21/10 | 90.5 (3.00) | |

| F(14.5) | 32.4 (p = < .001) |

1.13 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).