Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

31 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

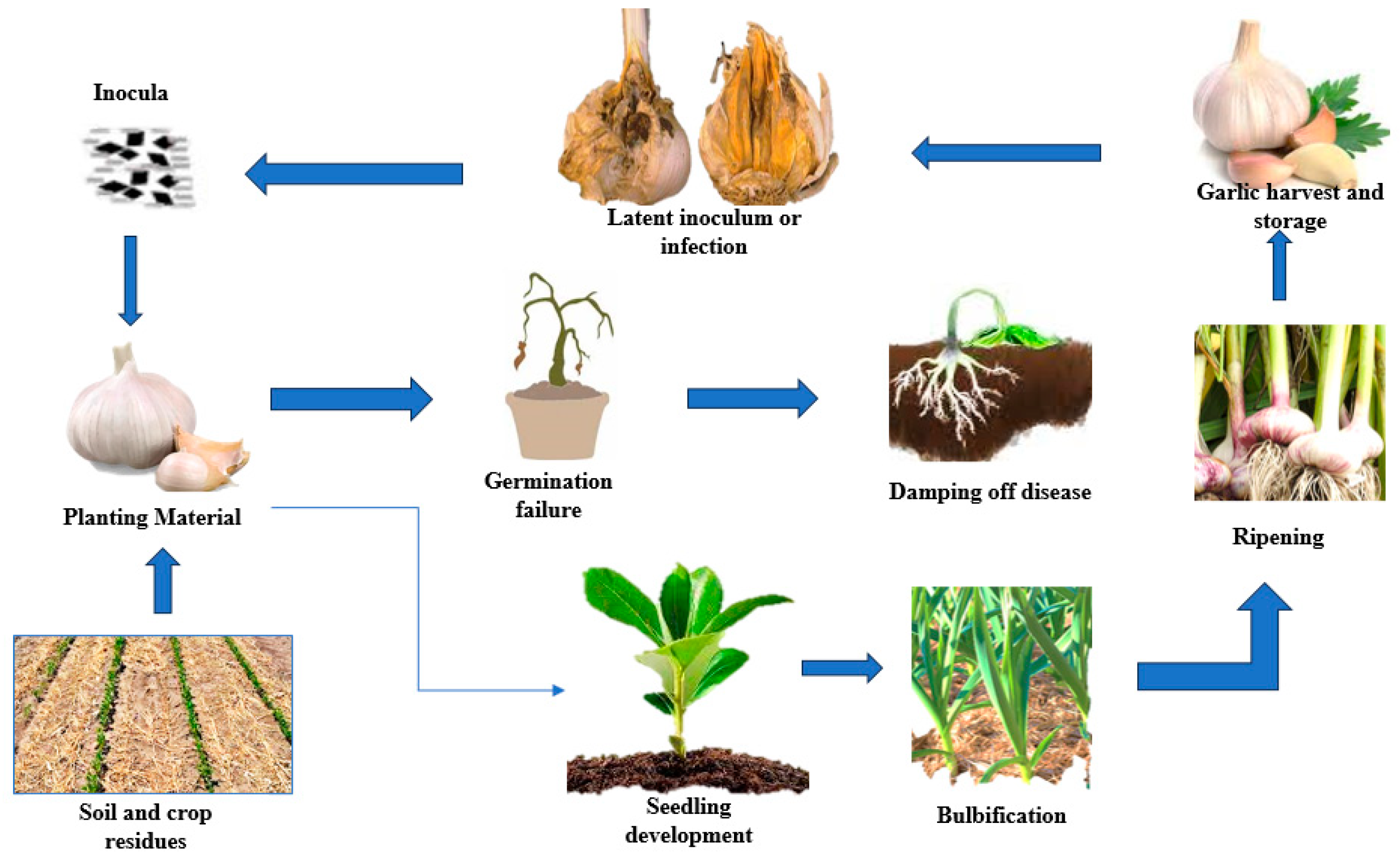

2. Garlic Seed Cloves as Habitat Pathogens

2.1. Fungal Pathogens

| Fungal Pathogen | Common Name | Disease Symptoms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium spp. | Blue Mold | Decay of seed cloves during storage | [30,31] |

| Botrytis spp. | Gray Mold | Gray mold on garlic bulbs | [32,33] |

| Fusarium spp. | Basal Rot | Basal rot and vascular wilt in plants | [12,34] |

| Sclerotium spp. | White Rot | White rot in garlic bulbs | [35] |

| Rhizoctonia spp. | Root Rot | Damping-off, root rot, and basal plate rot | [36,37] |

| Alternaria spp. | Leaf Blight | Leaf blight and bulb rot | [38] |

| Pythium spp. | Damping-off | Damping-off and root rot in seedlings | [39] |

| Sclerotinia spp. | White Mold | White mold on garlic bulbs | [40] |

| Colletotrichum spp. | Anthracnose | Anthracnose with sunken lesions | [41] |

| Myrothecium spp. | Bulb Rot | Bulb rot and leaf blight | [42] |

2.2. Fungal Pathogens in Soil

2.3. Mycotoxin

3. Bacteria and Virus

| Bacterial Pathogen | Common Name | Disease Symptoms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthomonas spp. | Bacterial Leaf Spot | Water-soaked lesions on leaves and bulbs | [58] |

| Pseudomonas spp. | Soft Rot | Softening and decay of bulbs | [59] |

| Erwinia spp. | Bacterial Bulb Decay | Slimy rotting of bulbs | [60] |

| Pantoea ananatis | Center Rot | Rotting and discoloration of bulb centers | [61] |

| Clavibacter spp. | Bacterial Canker | Raised, corky cankers on leaves and stems | [62] |

| Burkholderia cepacia | Bulb Rot | Rotting and foul odor in bulbs | [63] |

| Enterobacter cloacae | Basal Plate Rot | Rotting at the base of bulbs | [64] |

| Dickeya spp. | Blackleg | Blackened and soft rotting of stems | [65] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Crown Gall | Tumor-like growths on stems and roots | [66] |

| Virus | Common Name | Symptoms and Effects | Vectors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garlic common latent virus (GCLV) | Common Latent Virus | No visible symptoms, latent infection in garlic plants | Unknown | [67] |

| Garlic mosaic virus (GarMV) | Garlic Mosaic Virus | Mosaic patterns on leaves, stunted growth, reduced yield | Aphids (Myzus persicae) | [68] |

| Leek yellow stripe virus (LYSV) | Leek Yellow Stripe Virus | Yellow stripes on leaves, stunted growth, bulb deformities | Onion thrips (Thrips tabaci) | [69] |

| Shallot latent virus (SLV) | Shallot Latent Virus | No visible symptoms, latent infection in shallots | Unknown | [70] |

| Onion yellow dwarf virus (OYDV) | Onion Yellow Dwarf Virus | Stunted growth, yellowing of leaves, bulb size reduction | Onion thrips (Thrips tabaci) | [71] |

| Iris yellow spot virus (IYSV) | Iris Yellow Spot Virus | Yellow spots on leaves, necrotic streaks, bulb damage | Onion thrips (Thrips tabaci) | [72] |

| Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) | Cucumber Mosaic Virus | Mosaic patterns, leaf curling, plant stunting | Aphids (various species) | [73]t |

| Tobacco rattle virus (TRV) | Tobacco Rattle Virus | Stunted growth, yellowing, necrosis, bulb deformities | Soil-borne nematodes (Trichodorus spp.) | [74] |

| Shallot virus X (ShVX) | Shallot Virus X | Yellowing, stunted growth, distorted bulbs | Unknown | [75] |

| Garlic latent virus (GarLV) | Garlic Latent Virus | No visible symptoms, latent infection in garlic plants | Unknown | [76] |

4. Nematodes

| Nematode Pest | Common Name | Damage Symptoms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ditylenchus dipsaci | Stem and Bulb Nematode | Stunted growth, leaf yellowing, bulb rot, and reduced yield | [88] |

| Meloidogyne spp. | Root-Knot Nematode | Galls on roots, stunted growth, nutrient deficiency | [89] |

| Pratylenchus spp. | Lesion Nematode | Lesions on roots, reduced root system, poor nutrient uptake | [90] |

| Tylenchulus semipenetrans | Citrus Nematode | Feeding damage on roots, decline in plant health | [91] |

| Heterodera spp. | Cyst Nematode | Formation of cysts on roots, stunted growth, yield loss | [92] |

| Xiphinema spp. | Dagger Nematode | Feeding damage on roots, yellowing, wilting | [89] |

| Longidorus spp. | Needle Nematode | Stunted growth, root damage, nutrient deficiency | [89] |

| Trichodorus spp. | Sting Nematode | Feeding damage on roots, reduced root system | [93] |

| Pratylenchoides spp. | False Root-Knot Nematode | Root galling, stunted growth, reduced yield | [94] |

| Radopholus similis | Burrowing Nematode | Tunneling in roots, stunting, wilted leaves | [95] |

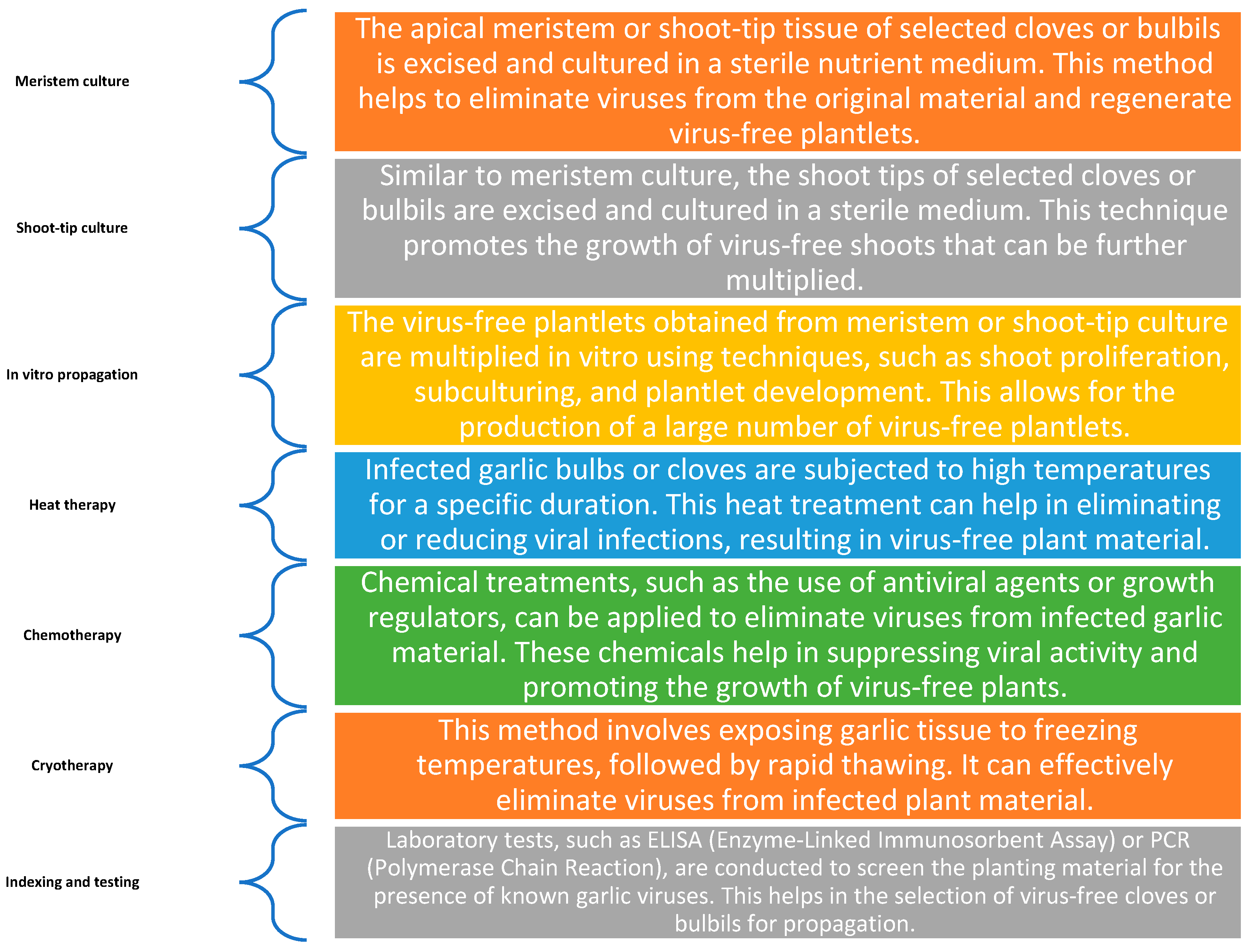

5. Disease Free Planting Stock

5.1. Resistant Cultivars

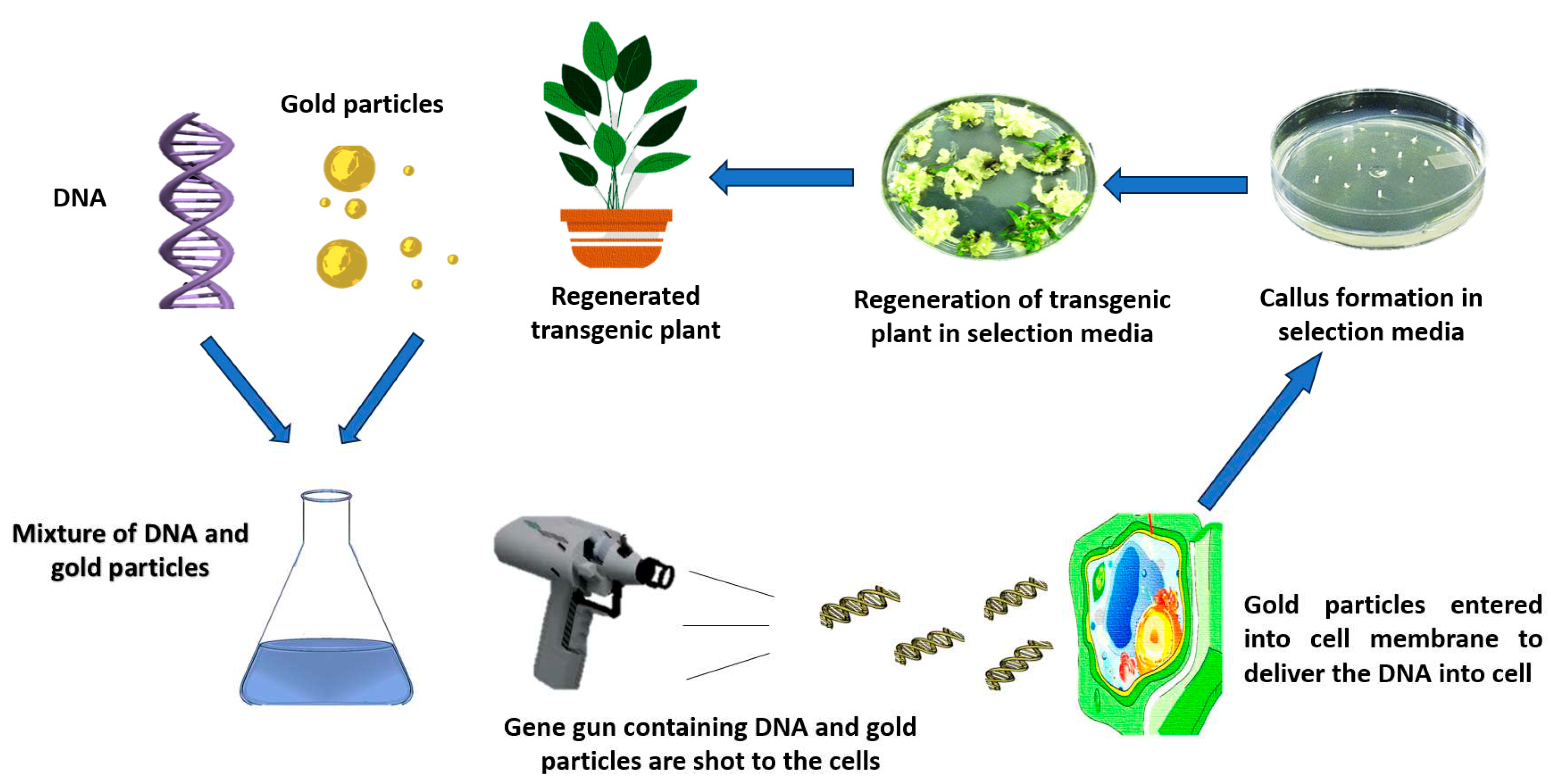

5.2. Genetic Modification

6. Challenges

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shemesh-Mayer, E.; Kamenetsky-Goldstein, R. Traditional and novel approaches in garlic (Allium sativum L.) breeding. Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Vegetable Crops: Volume 8: Bulbs, Roots and Tubers 2021, 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, F.M. Diseases and disease management in seed garlic: Problems and prospects. Am. J. Plant Sci. Biotechnol 2007, 1, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Marodin, J.C.; Resende, F.V.; Gabriel, A.; Souza, R.J.d.; Resende, J.T.V.d.; Camargo, C.K.; Zeist, A.R. Agronomic performance of both virus-infected and virus-free garlic with different seed bulbs and clove sizes. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira 2019, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, H.; Shemesh-Mayer, E.; Forer, I.; Kryukov, L.; Peters, R.; Kamenetsky-Goldstein, R. Bulbils in garlic inflorescence: development and virus translocation. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 285, 110146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shabasi, M.; Osman, Y.; Rizk, S. Effect of planting date and some pre-planting treatments on growth and yield of garlic. Journal of Plant Production 2018, 9, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, B.; Woldetsadik, K.; M Ali, W. Effect of harvesting time, curing and storage methods on storability of garlic bulbs. The Open Biotechnology Journal 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, B.; Mudgal, V.D.; Champawat, P.S. Storage of garlic bulbs (Allium sativum L.): A review. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2019, 42, e13177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, M.; Dong, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Meng, H. Growth, bolting and yield of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in response to clove chilling treatment. Scientia Horticulturae 2015, 194, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuzzo, L.; Xavier, A. Effect of temperature and photoperiod on the mycelial development of Stromatinia cepivora, the causal agent of white rot of garlic and onion. Summa Phytopathologica 2017, 43, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhar, K.M. Bulb development in garlic–a review. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, D.A.; Ivanova, E.A.; Semenov, M.V.; Zhelezova, A.D.; Ksenofontova, N.A.; Tkhakakhova, A.K.; Kholodov, V.A. Diversity, Ecological Characteristics and Identification of Some Problematic Phytopathogenic Fusarium in Soil: A Review. Diversity 2023, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, L.; Palmero, D. Fusarium dry rot of garlic bulbs caused by Fusarium proliferatum: A review. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahid, M.; Tony, H.S.; Isamail, M.E.; Galal, A.A. Effects of certain fungicide alternatives on garlic yield, storage ability and postharvest rot infection. New Valley Journal of Agricultural Science 2022, 2, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, R.; Moser, J. The role of mites in insect-fungus associations. Annual review of entomology 2014, 59, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, A.; Chong, J.H. Biological control strategies in integrated pest management (IPM) programs. Clemson University Cooperative, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension, LGP 2021, 1111, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, F.; Hellier, B.; Lupien, S. Pathogenic fungi in garlic seed cloves from the United States and China, and efficacy of fungicides against pathogens in garlic germplasm in Washington State. Journal of Phytopathology 2007, 155, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHOIRUDDIN, M.R.; FATAWI, Z.D.; HADIWIYONO, H. Virulence and genetic diversity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepae as the cause of root rot in garlic. Asian Journal of Tropical Biotechnology 2019, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez-Valle, R.; Macias-Valdez, L.M.; Reveles-Hernández, M. Common pathogens of garlic seed in Aguascalientes and Zacatecas, Mexico. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 2017, 8, 1881–1885. [Google Scholar]

- Buslyk, T.; Rosalovsky, V.; Salyha, Y. PCR-based detection and quantification of mycotoxin-producing fungi. Cytology and Genetics 2022, 56, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khar, A.; Hirata, S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Shigyo, M.; Singh, H. Breeding and genomic approaches for climate-resilient garlic. Genomic Designing of Climate-Smart Vegetable Crops 2020, 359–383. [Google Scholar]

- Aysan, Y.; Horuz, S. Commercially Important Vegetable Crop Diseases. In Handbook of Vegetable Preservation and Processing; CRC Press, 2015; pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas, M.C.; Cavagnaro, P.F. In vivo and in vitro screening for resistance against Penicillium allii in garlic accessions. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2020, 156, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, L.; Palmero, D. Incidence and etiology of postharvest fungal diseases associated with bulb rot in garlic (Alllium sativum) in Spain. Foods 2021, 10, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.H.; Javaid, A. Penicillium echinulatum causing blue mold on tomato in Pakistan. Journal of Plant Pathology 2022, 104, 1143–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visagie, C.; Houbraken, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Hong, S.-B.; Klaassen, C.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.; Varga, J.; Yaguchi, T.; Samson, R. Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium. Studies in mycology 2014, 78, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houbraken, J.; Kocsubé, S.; Visagie, C.M.; Yilmaz, N.; Wang, X.-C.; Meijer, M.; Kraak, B.; Hubka, V.; Bensch, K.; Samson, R. Classification of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and related genera (Eurotiales): An overview of families, genera, subgenera, sections, series and species. Studies in mycology 2020, 95, 5–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimer, O. Different mulch material on growth, performance and yield of garlic: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Agric 2020, 4, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenetsky, R. Garlic: botany and horticulture. HORTICULTURAL REVIEWS-WESTPORT THEN NEW YORK- 2007, 33, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Iqbal, N. Post-harvest pathogens and disease management of horticultural crop: A brief review. Plant Arch 2020, 20, 2054–2058. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Askar, A.A.; Rashad, E.M.; Ghoneem, K.M.; Mostafa, A.A.; Al-Otibi, F.O.; Saber, W.I. Discovering Penicillium polonicum with high-lytic capacity on Helianthus tuberosus tubers: Oil-based preservation for mold management. Plants 2021, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, J.F. Preliminary Studies on Fungus Associated with Storage Disease of Garlic (Allium Sativum L.) in Nigeria.

- Chen, J.; Yan, R.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Hu, H. Compositional shifts in the fungal diversity of garlic scapes during postharvest transportation and cold storage. Lwt 2019, 115, 108453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Sharma, G.; Sharma, K. Major Diseases of Garlic (Allium Sativum L.) and Their Management. Diseases of Horticultural Crops: Diagnosis and Management: Volume 2: Vegetable Crops 2022, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Le, D.; Audenaert, K.; Haesaert, G. Fusarium basal rot: profile of an increasingly important disease in Allium spp. Tropical Plant Pathology 2021, 46, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, V.P.; Araújo, N.A.; Schwanestrada, K.R.; Pasqual, M.; Dória, J. Athelia (Sclerotium) rolfsii in Allium sativum: potential biocontrol agents and their effects on plant metabolites. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2018, 90, 3949–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chohan, S.; Perveen, R.; Abid, M.; Naqvi, A.H.; Naz, S. Management of seed borne fungal diseases of tomato: a review. Pakistan Journal of Phytopathology 2017, 29, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Hussain, H.; Shah, B.; Ullah, W.; Naeem, A.; Ali, W.; Khan, N.; Adnan, M.; Junaid, K.; Shah, S.R.A. Evaluation of phytobiocides and different culture media for growth, isolation and control of Rhizoctonia solani in vitro. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2016, 4, 417–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bisht, I.; Agrawal, R. Susceptibility to purple blotch (Alternaria porri) in garlic (Allium sativum). Annals of applied biology 1993, 122, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Qi, K.; Wang, P.; Li, C.; Qi, J. Identification of Pythium species as pathogens of garlic root rot. Journal of Plant Pathology 2021, 103, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, V.P.; Araújo, N.A.F.; Machado, N.B.; Júnior, P.S.P.C.; Pasqual, M.; Alves, E.; Schwan-Estrada, K.R.F.; Doria, J. Yeasts and Bacillus spp. as potential biocontrol agents of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in garlic. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 261, 108931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; K, J.; Nadig, S.M.; Manjunathagowda, D.C.; Gurav, V.S.; Singh, M. Anthracnose of onion (Allium cepa L.): A twister disease. Pathogens 2022, 11, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bruggen, A.H.; Gamliel, A.; Finckh, M.R. Plant disease management in organic farming systems. Pest Management Science 2016, 72, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidharthan, V.K.; Aggarwal, R.; Shanmugam, V. Fusarium wilt of crop plants: disease development and management. Wilt Diseases of Crops and their Management 2019, 519–533. [Google Scholar]

- De la Lastra, E.; Camacho, M.; Capote, N. Soil bacteria as potential biological control agents of Fusarium species associated with asparagus decline syndrome. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambhulkar, P.P.; Raja, M.; Singh, B.; Katoch, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, P. Potential native Trichoderma strains against Fusarium verticillioides causing post flowering stalk rot in winter maize. Crop Protection 2022, 152, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J.; Summerell, B. Fusarium laboratory workshops—A recent history. Mycotoxin Research 2006, 22, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 오지연; 김기덕. Control strategies for fungal pathogens on stored onion (Allium cepa) and garlic (Allium sativum): A Review. 생명자원연구 2016, 24, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Mendez, W.; Obregon, M.; Moran-Diez, M.E.; Hermosa, R.; Monte, E. Trichoderma asperellum biocontrol activity and induction of systemic defenses against Sclerotium cepivorum in onion plants under tropical climate conditions. Biological Control 2020, 141, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.L.; Hua, G.K.H.; Scott, J.C.; Dung, J.K.; Qian, M.C. Evaluation of Sulfur-Based Biostimulants for the Germination of Sclerotium cepivorum Sclerotia and Their Interaction with Soil. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2022, 70, 15038–15045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis-Madden, R.; Rehmen, S.; Hildebrand, P. GARLIC STORAGE, POST-HARVEST DISEASES, AND PLANTING STOCK CONSIDERATIONS. FACT SHEET 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seefelder, W.; Gossmann, M.; Humpf, H.-U. Analysis of fumonisin B1 in Fusarium proliferatum-infected asparagus spears and garlic bulbs from Germany by liquid chromatography− electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2002, 50, 2778–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, O.K.; Seredin, T.M.; Danilova, O.A.; Filyushin, M.A. First report of Fusarium proliferatum causing garlic clove rot in Russian Federation. Plant Disease 2021, 105, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, A.E. Fusarium mycotoxins: chemistry, genetics, and biology; American Phytopathological Society (APS Press), 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic, S.; Levic, J.; Petrovic, T.; Logrieco, A.; Moretti, A. Pathogenicity and mycotoxin production by Fusarium proliferatum isolated from onion and garlic in Serbia. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2007, 118, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, M.-A.; Luçon, N.; Houdault, S. Clove-transmissibility of Pseudomonas salomonii, the causal agent of ‘Café au lait’disease of garlic. European journal of plant pathology 2009, 124, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallock-Richards, D.; Doherty, C.J.; Doherty, L.; Clarke, D.J.; Place, M.; Govan, J.R.; Campopiano, D.J. Garlic revisited: antimicrobial activity of allicin-containing garlic extracts against Burkholderia cepacia complex. PLoS One 2014, 9, e112726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, A.A.; Abbas, E.E.; Tohamy, M.; El-Said, H. EFFECTIVE FACTORS ON ONION BACTERIAL SOFT ROT DISEASE INCIDENCE DURING STORAGE. Zagazig Journal of Agricultural Research 2019, 46, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumagnac, P.; Gagnevin, L.; Gardan, L.; Sutra, L.; Manceau, C.; Dickstein, E.; Jones, J.B.; Rott, P.; Pruvost, O. Polyphasic characterization of xanthomonads isolated from onion, garlic and Welsh onion (Allium spp.) and their relatedness to different Xanthomonas species. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2004, 54, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardan, L.; Bella, P.; Meyer, J.-M.; Christen, R.; Rott, P.; Achouak, W.; Samson, R. Pseudomonas salomonii sp. nov., pathogenic on garlic, and Pseudomonas palleroniana sp. nov., isolated from rice. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2002, 52, 2065–2074. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, H.; Horita, H.; Nishimura, F.; Mori, M. Pseudomonas salomonii, another causal agent of garlic spring rot in Japan. Journal of general plant pathology 2020, 86, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurjanah, N.; Joko, T.; Subandiyah, S. Characterization of Pantoea ananatis isolated from garlic and shallot. Jurnal Perlindungan Tanaman Indonesia 2017, 21, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, S.T.; Gladders, P.; Paulus, A.O. Vegetable diseases: a color handbook; Gulf Professional Publishing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Júnior, P.S.P.C.; Cardoso, F.P.; Martins, A.D.; Buttrós, V.H.T.; Pasqual, M.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F.; Dória, J. Endophytic bacteria of garlic roots promote growth of micropropagated meristems. Microbiological research 2020, 241, 126585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Tian, X.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. First Report of Enterobacter cloacae Causing Bulb Decay on Garlic in China. Plant Disease 2022, 106, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wolf, J.M.; Acuña, I.; De Boer, S.H.; Brurberg, M.B.; Cahill, G.; Charkowski, A.O.; Coutinho, T.; Davey, T.; Dees, M.W.; Degefu, Y. Diseases caused by Pectobacterium and Dickeya species around the world. Plant diseases caused by Dickeya and Pectobacterium species 2021, 215–261. [Google Scholar]

- Eady, C.; Davis, S.; Catanach, A.; Kenel, F.; Hunger, S. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of leek (Allium porrum) and garlic (Allium sativum). Plant Cell Reports 2005, 24, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellardi, M.; Marani, F.; Betti, L.; Rabiti, A. Detection of garlic common latent virus (GCLV) in Allium sativum L. in Italy. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 1995, 34, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yong-Jian, F.; Chu-Hua, W.; Zhen-Xiao, L.; Zheng, X. Molecular Cloning and Nucleotide Sequence of the Coat Protein Gene from Garlic Mosaic Virus. Virologica Sinica 2015, 9, 333. [Google Scholar]

- Lunello, P.; Di Rienzo, J.; Conci, V.C. Yield loss in garlic caused by Leek yellow stripe virus Argentinean isolate. Plant disease 2007, 91, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Baranwal, V.; Joshi, S. Simultaneous detection of Onion yellow dwarf virus and Shallot latent virus in infected leaves and cloves of garlic by duplex RT-PCR. Journal of Plant Pathology 2008, 371–374. [Google Scholar]

- Lot, H.; Chovelon, V.; Souche, S.; Delecolle, B. Effects of onion yellow dwarf and leek yellow stripe viruses on symptomatology and yield loss of three French garlic cultivars. Plant disease 1998, 82, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Schwartz, H.F.; Cramer, C.S.; Havey, M.J.; Pappu, H.R. Iris yellow spot virus (T ospovirus: B unyaviridae): from obscurity to research priority. Molecular plant pathology 2015, 16, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanac, Z. Cucumber mosaic virus in garlic. Acta Botanica Croatica 1980, 39, 21M26. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, R.; Lesemann, D.-E.; Pleij, C. Tobacco rattle virus genome alterations in the Hosta hybrid ‘Green Fountain’and other plants: reassortments, recombinations and deletions. Archives of virology 2012, 157, 2005–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.I.; Song, J.T.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y.D. Molecular characterization of the garlic virus X genome. Journal of General Virology 1998, 79, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Baranwal, V. First report of Garlic common latent virus in garlic from India. Plant Disease 2009, 93, 106–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.M.; Majeed, A.J. Effect of growing seasons, plant extracts with various rates on Black Bean Aphid, Aphis Fabae (Aphididae: Homoptera). Kurdistan Journal of Applied Research 2018, 3, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, B.; Archana, M.; Sharma, S. Nematode vectors of plant diseases and its perspectives. Advances in Nematology 2003, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Gharekhani, G.; Ghorbansyahi, S.; Saber, M.; Bagheri, M. Influence of the colour and height of sticky traps in attraction of Thrips tabaci (Lindeman)(Thysanoptera, Thripidae) and predatory thrips of family Aeolothripidae on garlic, onion and tomato crops. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 2014, 47, 2270–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.T.; Koo, B.J.; Jung, J.H.; Chang, M.U.; Kang, S.G. Detection of allexiviruses in the garlic plants in Korea. The Plant Pathology Journal 2007, 23, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunello, P.; Mansilla, C.; Sánchez, F.; Ponz, F. A developmentally linked, dramatic, and transient loss of virus from roots of Arabidopsis thaliana plants infected by either of two RNA viruses. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2007, 20, 1589–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrič, I.; Ravnikar, M. A carlavirus serologically closely related to Carnation latent virus in Slovenian garlic. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica 2005, 85, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Ye, W.; Badiss, A.; Sun, F. Description of Ditylenchus dipsaci (Kuhn, 1857) Filipjev, 1936 (Nematoda: Anguinidae) infesting garlic in Ontario, Canada. International journal of Nematology 2010, 20, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Zaida, M.; Hughes, B.; Celetti, M. Discovery of potato rot nematode, Ditylenchus destructor, infesting garlic in Ontario, Canada. Plant disease 2012, 96, 297–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiñez, S. Control of the stem and bulb nematode Ditylenchus dipsaci,(Kuhn) Filipjev on garlic crops (Allium sativum L.). Agricultura Técnica (Santiago) 1992, 51, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- DRAGHICI, D.; MIHUT, A.; HANGANU, M.; VIRTEIU, A.M.; GROZEA, I. EVALUATION AND KEEPING UNDER CONTROL THE PEST POPULATIONS OF GARLIC CULTIVATED IN AN ORGANIC SYSTEM. Research Journal of Agricultural Science 2022, 54. [Google Scholar]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Abuljadayel, D.A.; Shafi, M.E.; Albaqami, N.M.; Desoky, E.-S.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Mesiha, P.K.; Elnahal, A.S.; Almakas, A.; Taha, A.E. Control of foliar phytoparasitic nematodes through sustainable natural materials: Current progress and challenges. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2021, 28, 7314–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollov, D.; Subbotin, S.; Rosen, C. First report of Ditylenchus dipsaci on garlic in Minnesota. Plant disease 2012, 96, 1707–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindra, H.; Sehgal, M.; Narasimhamurthy, H.; Soumya, D. First Report of Root-Knot Nematode (Meloidogyne spp.) on Garlic in India. Indian Journal of Nematology 2015, 45, 121–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, A.; Al Hinai, M.S.; Handoo, Z. Occurrence, population density, and distribution of root-lesion nematodes, Pratylenchus spp., in the Sultanate of Oman. Nematropica 1997, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Youssef, M. Population dynamics of the citrus nematode, Tylenchulus semipenetrans, on navel orange as affected by some plant residues, an organic manure and a biocide. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 2014, 47, 2233–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creech, J.E.; Johnson, W.G. Survey of broadleaf winter weeds in Indiana production fields infested with soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines). Weed technology 2006, 20, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupriya, P.; Anita, B.; Kalaiarasan, P.; Karthikeyan, G. Population dynamics and community analysis of plant parasitic nematodes associated with carrot, potato and garlic in the Nilgiris district, Tamil Nadu. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2019, 7, 627–630. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuzaslanoglu, E.; Sonmezoglu, O.A.; Genc, N.; Akar, Z.M.; Ocal, A.; Karaca, M.S.; Elekcioglu, I.H.; Ozsoy, V.S.; Aydogdu, M. Occurrence and abundance of nematodes on onion in Turkey and their relationship with soil physicochemical properties. Nematology 2019, 21, 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, D.; Keetch, D. Other Contributions: Some Observations on the Host Plant Relationships of Radopholus similis in Natal. Nematropica 1976, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Loyola-Vargas, V.M.; Ochoa-Alejo, N. An introduction to plant cell culture: the future ahead. Plant cell culture protocols 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tegen, H.; Mohammed, W. The role of plant tissue culture to supply disease free planting materials of major horticultural crops in Ethiopia. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare 2016, 6, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bikis, D. Review on the application of biotechnology in garlic (Allium sativum) improvement. International Journal of Research Studies in Agricultural Sciences 2018, 4, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Twaij, B.M.; Jazar, Z.H.; Hasan, M.N. Trends in the use of tissue culture, applications and future aspects. International Journal of plant biology 2020, 11, 8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Qarshi, I.A.; Nazir, H.; Ullah, I. Plant tissue culture: current status and opportunities. Recent advances in plant in vitro culture 2012, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bagi, F.; Stojscaron, V.; Budakov, D.; El Swaeh, S.M.A.; Gvozdanovi-Varga, J. Effect of onion yellow dwarf virus (OYDV) on yield components of fall garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Serbia. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2012, 7, 2386–2390. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, R.; Batra, V. Evaluation of garlic varieties against purple blotch disease and yield. Journal of Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Sciences 2005, 27, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, M.M.; Sahi, S.T.; Habib, A.; Ashraf, W.; Zeshan, M.A.; Raheel, M.; Shakeel, Q. Management of Fusarium basal rot of onion caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepae through desert plants extracts. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture 2021, 37, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, J.G.; Makuch, M.A.; Ordovini, A.F.; Frisvad, J.C.; Overy, D.P.; Masuelli, R.W.; Piccolo, R.J. Identification, pathogenicity and distribution of Penicillium spp. isolated from garlic in two regions in Argentina. Plant pathology 2009, 58, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, J.G.; Makuch, M.A.; Ordovini, A.F.; Masuelli, R.W.; Overy, D.P.; Piccolo, R. First report of Penicillium allii as a field pathogen of garlic (Allium sativum). 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, F.; Crowe, F. Embellisia skin blotch and bulb canker of garlic. Compendium of Onion and Garlic Diseases and Pests, 2nd Edn. HF Schwartz and SK Mohan, eds. American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN 2008, 17-18.

- Martínez, F.L.; Noyola, P.P. Caracterización molecular de aislados de Sclerotium cepivorum mediante análisis del polimorfismo de los fragmentos amplificados al azar. Acta Universitaria 2001, 11, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, S.; Smith, R. First report of rust caused by Puccinia allii on wild garlic in California. Plant Disease 2001, 85, 1290–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolini, P.; Tian, S.P. Low-temperature biology and pathogenicity of Penicillium hirsutum on garlic in storage. Postharvest Biology and Technology 1996, 7, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreño, R.; Rodríguez-Alcocer, E.; Martínez-Guardiola, C.; Carrasco, L.; Castillo, P.; Arbona, V.; Jover-Gil, S.; Candela, H. Turning Garlic into a Modern Crop: State of the Art and Perspectives. Plants 2023, 12, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultom, T.; Simbolon, D.L.; Nainggolan, W.S. Effect of gamma rays on phenotypic of garlic cultivar doulu. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2020; p. 012081. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).