Submitted:

27 October 2023

Posted:

27 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Binding affinity and interactions of terpenes with DPP-4 enzyme

2.2. Binding affinity and interactions of terpenes with PTP1B enzyme

2.3. Ensemble docking analysis of selected triterpenes against DPP-4

2.4. Molecular dynamics of terpene-DPP-4 interactions

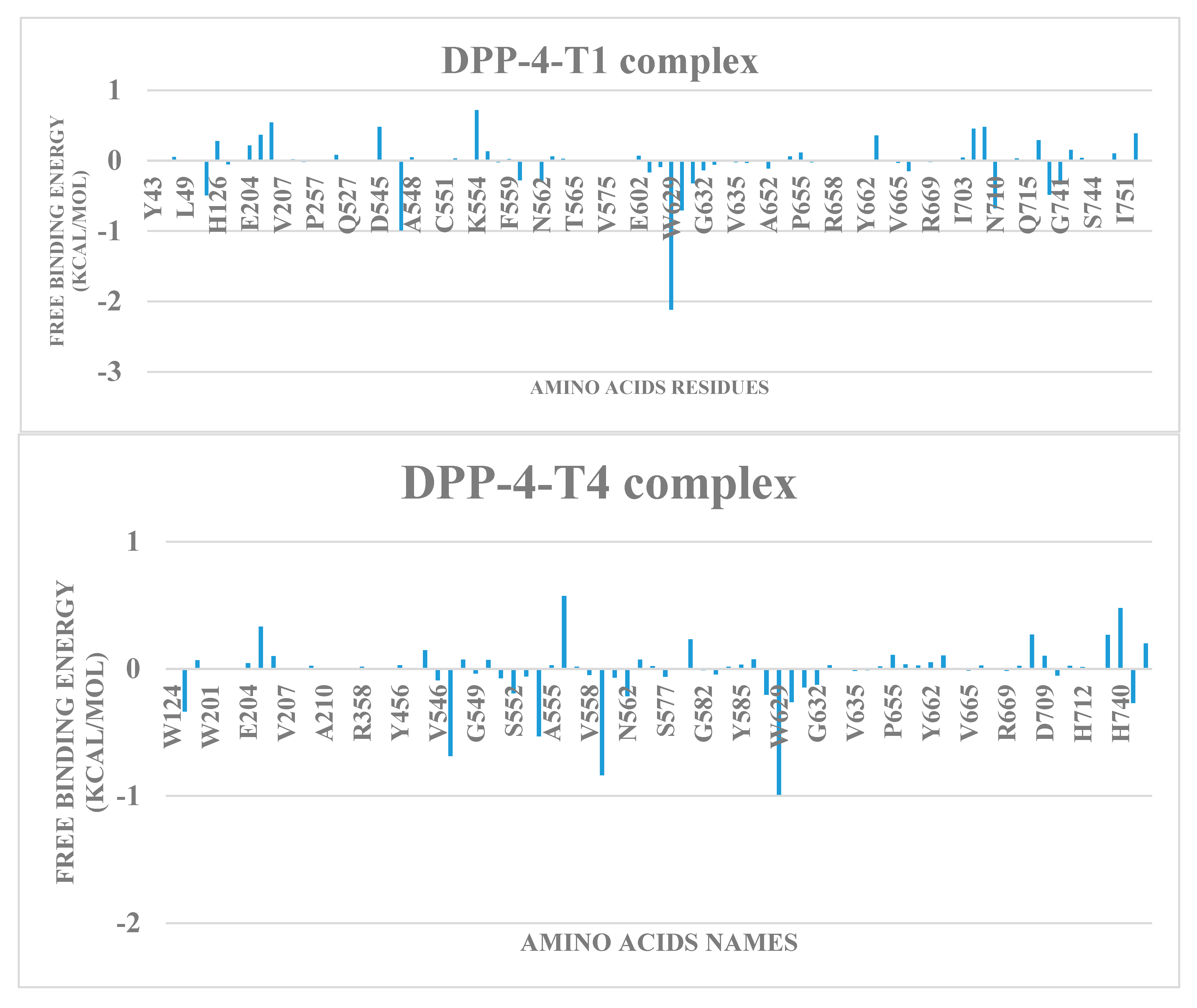

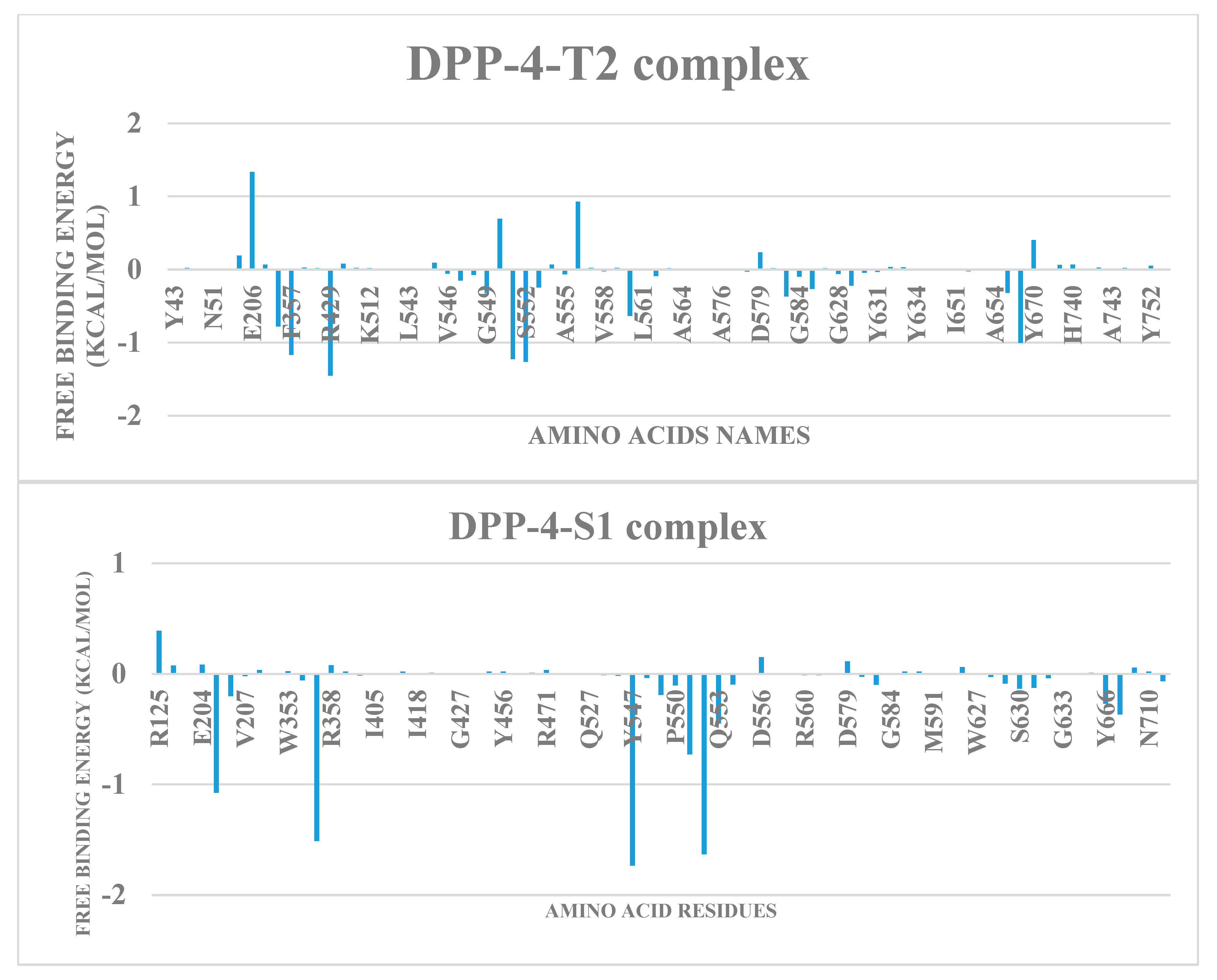

2.5. Free energy simulation of DPP-4-terpene complexes

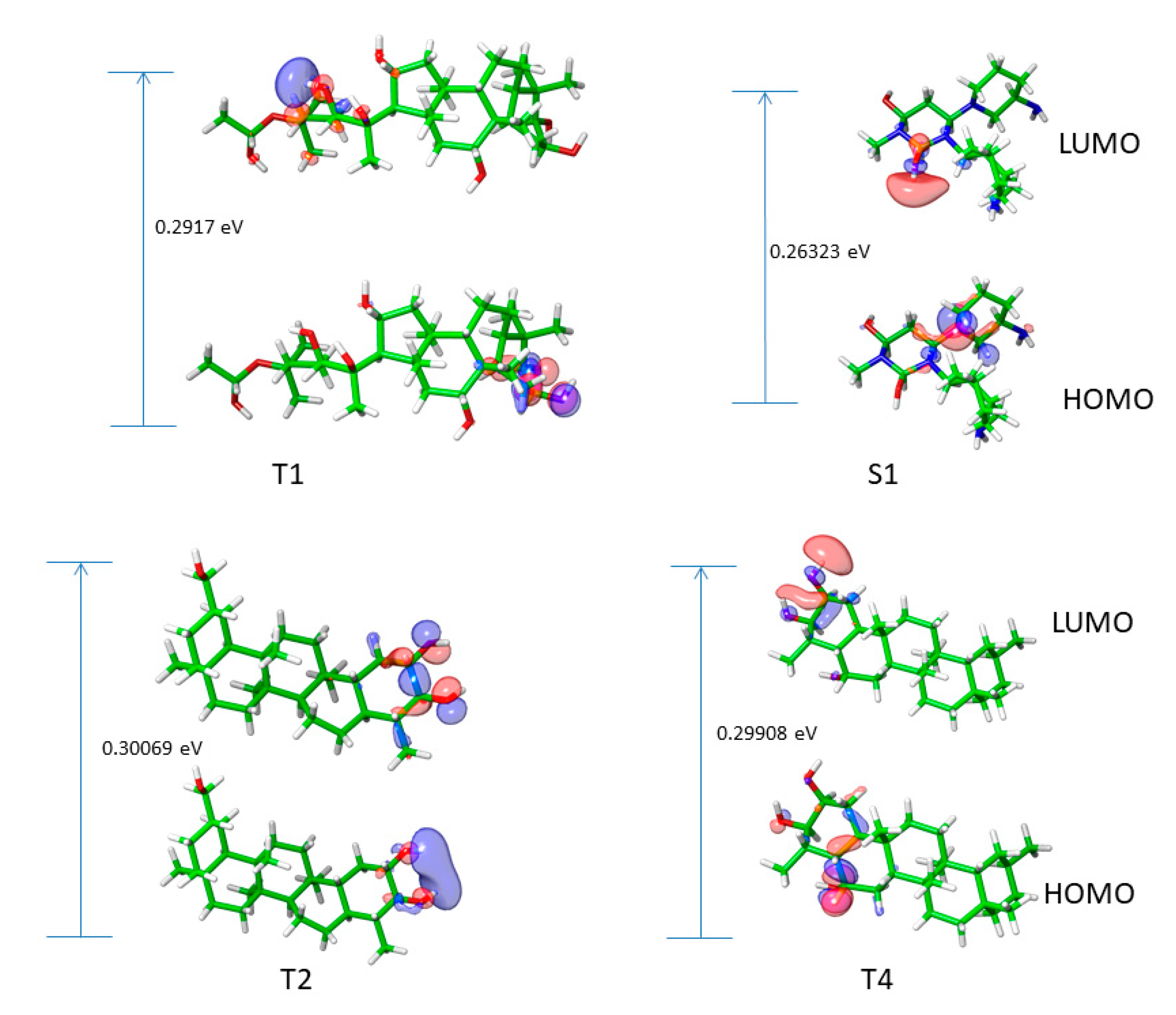

2.6. Frontier molecular orbitals of top triterpenes

2.7. Predicted physicochemical and ADMET properties of hit triterpenes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of protein structures

4.2. Ligand preparation

4.3. Molecular docking calculations

| Dimensions | DPP-4 (Å) |

PTP1B (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| center_x | 34.88 | 14.79 |

| center_y | 29.17 | -3.40 |

| center_z | 16.00 | 1.69 |

| Size x | 21.92 | 16.50 |

| Size y | 17.77 | 19.72 |

| Size z | 22.83 | 27.64 |

4.4. Prime MM-GBSA post docking calculations

4.5. Ensemble docking analysis

4.6. Molecular dynamics simulation

4.7. Clustering analysis

4.8. Binding free energy calculation using MM-GBSA

4.9. Density functional theory

4.10. Physicochemical admetSAR analysis

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Kaur N, Kumar V, Nayak SK, et al. Alpha-amylase as molecular target for treatment of diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive review. Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 2021 2021/10/01;98,539-560. [CrossRef]

- Whiting, D.R.; Guariguata, L.; Weil, C.; Shaw, J. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 94, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, N.H. Q&A: Five questions on the 2015 IDF Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 115, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, N.H.; Shaw, J.E.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; da Rocha Fernandes, J.D.; Ohlrogge, A.W.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 138, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimann, M.; Bonifacio, E.; Solimena, M.; Schwarz, P.; Ludwig, B.; Hanefeld, M.; Bornstein, S. An update on preventive and regenerative therapies in diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 121, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourad, A.A.E.; Khodir, A.E.; Saber, S.; Mourad, M.A.E. Novel Potent and Selective DPP-4 Inhibitors: Design, Synthesis and Molecular Docking Study of Dihydropyrimidine Phthalimide Hybrids. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes care. 2014 Jan;37 Suppl 1:S81-90. [CrossRef]

- Piłaciński, S.; Zozulińska-Ziółkiewicz, D.A. State of the art paper Influence of lifestyle on the course of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Arch. Med Sci. 2014, 1, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.; Chowta, M.; Chowta, N.; Shastry, R.; Kamath, P. The Proportion of Type 2 Diabetic Patients Achieving Treatment Goals and the Survey of Patients’ Attitude Towards Insulin In tiation ini Patient s with Inadequate Glycaemic Control with Oral Anti-diabetic Drugs. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2021, 17, e110620182719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, T.; Sampson, S.R. Activation of Insulin Signaling by Botanical Products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moller David, E. Metabolic Disease Drug Discovery— “Hitting the Target” Is Easier Said Than Done. Cell metabolism. 2012 2012/01/04/;15,19-24. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, A.; Kanwar, N.; Bharati, S.; Srivastava, P.; Singh, S.P.; Amar, S. Exploring New Drug Targets for Type 2 Diabetes: Success, Challenges and Opportunities. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasole, R.; Martin, H.D.; Kimiywe, J. Traditional Medicine and Its Role in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus: "Patients' and Herbalists' Perspectives". Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 2835691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, S.K.; Bhatt, R.; Kumar, A. Targeting type II diabetes with plant terpenes: the new and promising antidiabetic therapeutics. Biologia 2021, 76, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi OM, Gyebi GA, Saheed A, et al. Inhibition mechanism of alpha-amylase, a diabetes target, by a steroidal pregnane and pregnane glycosides derived from Gongronema latifolium Benth [Original Research]. Frontiers in molecular biosciences. 2022 2022-August-10;9. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, T.; Pan, S.; Qiu, J.; Zhou, S. Overview of clinically approved oral antidiabetic agents for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2015, 42, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Tahrani, A.; Bailey, C.J.; Del Prato, S.; Barnett, A.H. Management of type 2 diabetes: new and future developments in treatment. Lancet 2011, 378, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, O.M.; Gyebi, A.G.; Adebayo, J.O.; Oguntola, J.A.; Olaiya, C.O. Marsectohexol and other pregnane phytochemicals derived from Gongronema latifolium as α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors: in vitro and molecular docking studies. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M. Incretin therapies: highlighting common features and differences in the modes of action of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Diabetes, Obes. Metab. 2016, 18, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M.A.; Niedereichholz, U.; Ettler, R.; Holst, J.J.; Ørskov, C.; Ritzel, R.; Schmiegel, W.H.; Edgerton, D.S.; Kraft, G.; Smith, M.S.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 inhibition of gastric emptying outweighs its insulinotropic effects in healthy humans. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 1997, 273, E981–E988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliaki, C.; Doupis, J. Incretin-based therapy: a powerful and promising weapon in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. Res. Treat. Educ. Diabetes Relat. Disord. 2011, 2, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvo, F.; Moore, N.; Arnaud, M.; Robinson, P.; Raschi, E.; De Ponti, F.; Bégaud, B.; Pariente, A. Addition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors to sulphonylureas and risk of hypoglycaemia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016, 353, i2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternoster S, Falasca M. Dissecting the Physiology and Pathophysiology of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 [Review]. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2018 2018-October-11;9. [CrossRef]

- Glossmann, H.H.; Lutz, O.M. Pharmacology of metformin – An update. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 865, 172782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, G.; Hardie, D.G.; Pearson, E.R. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondani G, Peyron J-F. Metformin, an Anti-diabetic Drug to Target Leukemia [Mini Review]. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2018 2018-August-10;9. [CrossRef]

- McGovern, A.; Tippu, Z.; Hinton, W.; Munro, N.; Whyte, M.; de Lusignan, S. Comparison of medication adherence and persistence in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes, Obes. Metab. 2017, 20, 1040–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain H, Green IR, Abbas G, et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitors as potential anti-diabetes agents: patent review (2015-2018). Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 2019 2019/09/02;29(9):689-702. [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, M.; Hosseini, H.; ArabSadeghabadi, Z.; Babaei-Khorzoughi, R.; Gorgani-Firuzjaee, S.; Meshkani, R. The role of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 78, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, M.; Gupta, S.J.; Chaudhary, A.; Garg, V.K. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors as antidiabetic agents – A brief review. Bioorganic Chem. 2017, 70, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, A.; Tajuddeen, N. Antidiabetic compounds from medicinal plants traditionally used for the treatment of diabetes in Africa: A review update (2015–2020). South Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 146, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Islam, S. African Medicinal Plants with Antidiabetic Potentials: A Review. Planta Medica 2014, 80, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaiya C, O Soetan K, M Esan A. The role of nutraceuticals, functional foods and value added food products in the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. Afr J Food Sci. 2016;10,185-193. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed A, Ibrahim H, Islam MS. Chapter 8 - Plant-Derived Antidiabetic Compounds Obtained From African Medicinal Plants: A Short Review. In: Atta ur R, editor. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. Vol. 54: Elsevier; 2017. p. 291-314.

- Mahomoodally, M.; Korumtollee, H.; Chady, Z. Ethnopharmacological uses of Antidesma madagascariense Lam. (Euphorbiaceae). J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 4, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beidokhti, M.; Lobbens, E.; Rasoavaivo, P.; Staerk, D.; Jäger, A. Investigation of medicinal plants from Madagascar against DPP-IV linked to type 2 diabetes. South Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 115, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, L.; Havik, P.J.; Romeiras, M.M. Medicinal plants of Guinea-Bissau: Therapeutic applications, ethnic diversity and knowledge transfer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 183, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, Z.; Guo, B.; Sun, M.; Onakpa, M.M.; Yao, G.; Zhao, M.; Che, C.-T. Modified diterpenoids from the tuber of Icacina oliviformis as protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-I.; Chou, C.-H.; Liao, M.-H.; Chen, T.-M.; Cheng, C.-H.; Anggriani, R.; Tsai, C.-P.; Tseng, H.-I.; Cheng, H.-L. Bitter melon triterpenes work as insulin sensitizers and insulin substitutes in insulin-resistant cells. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 13, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majouli, K.; Hlila, M.B.; Hamdi, A.; Flamini, G.; Ben Jannet, H.; Kenani, A. Antioxidant activity and α-glucosidase inhibition by essential oils from Hertia cheirifolia (L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 82, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy SK, Kumar A, Bhatt R. Hedychium coronarium Rhizomes: Promising Antidiabetic and Natural Inhibitor of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase. Journal of dietary supplements. 2020;17,81-87. [CrossRef]

- Gong Y, Chen K, Yu SQ, et al. [Protective effect of terpenes from fructus corni on the cardiomyopathy in alloxan-induced diabetic mice]. Zhongguo ying yong sheng li xue za zhi = Zhongguo yingyong shenglixue zazhi = Chinese journal of applied physiology. 2012 Jul;28,378-80, 384.

- Ma TK, Xu L, Lu LX, et al. Ursolic Acid Treatment Alleviates Diabetic Kidney Injury By Regulating The ARAP1/AT1R Signaling Pathway. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity : targets and therapy. 2019;12:2597-2608. [CrossRef]

- Praveen Kumar M, Poornima, Mamidala E, et al. Effects of D-Limonene on aldose reductase and protein glycation in diabetic rats. Journal of King Saud University - Science. 2020 2020/04/01/;32,1953-1958. [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, Y.; Soeatmadji, D.W.; Sumitro, S.B.; Widodo, M.A. Anti-diabetic potential of Urena lobata leaf extract through inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.-F.; Gao, L.-X.; Li, J.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Guo, Y.-W. Cembrane diterpenoids from the soft coral Sarcophyton trocheliophorum Marenzeller as a new class of PTP1B inhibitors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 5076–5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.-B.; Zhang, H.; Dong, S.-H.; Sheng, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Yue, J.-M. New triterpenoids with protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibition from Cedrela odorata. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 16, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunyemi, O.M.; Gyebi, G.A.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Esan, A.M.; Olaiya, C.O.; Soliman, M.M.; Batiha, G.E.-S. Identification of promising multi-targeting inhibitors of obesity from Vernonia amygdalina through computational analysis. Mol. Divers. 2022, 27, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Singla, R.; Jaitak, V. In Silico Study of Flavonoids as DPP-4 and α-glucosidase Inhibitors. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2018, 15, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalichem, N.S.S.; Jupudi, S.; Yasam, V.R.; Basavan, D. Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitory action of Calebin A: An in silico and in vitro analysis. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2021, 12, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quek, A.; Kassim, N.K.; Lim, P.C.; Tan, D.C.; Latif, M.A.M.; Ismail, A.; Shaari, K.; Awang, K. α-Amylase and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitory effects of Melicope latifolia bark extracts and identification of bioactive constituents using in vitro and in silico approaches. [CrossRef]

- Quy PT, Van Hue N, Bui TQ, et al. Inhibitory, biocompatible, and pharmacological potentiality of dammarenolic-acid derivatives towards α-glucosidase (3W37) and tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B). Vietnam Journal of Chemistry. 2022 2022/04/01;60,223-237. [CrossRef]

- Olawale, F.; Olofinsan, K.; Iwaloye, O.; Chukwuemeka, P.O.; Elekofehinti, O.O. Screening of compounds from Nigerian antidiabetic plants as protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitor. Comput. Toxicol. 2022, 21, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wallace, M.B.; Feng, J.; Stafford, J.A.; Skene, R.J.; Shi, L.; Lee, B.; Aertgeerts, K.; Jennings, A.; Xu, R.; et al. Design and Synthesis of Pyrimidinone and Pyrimidinedione Inhibitors of Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, P.; Baby, B.; Aleissaee, H.M.; Vijayan, R. A Molecular Modeling Investigation of the Therapeutic Potential of Marine Compounds as DPP-4 Inhibitors. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzouzi JT, Soh PN, Mbatchi B, et al. Cogniauxia podolaena: bioassay-guided fractionation of defoliated stems, isolation of active compounds, antiplasmodial activity and cytotoxicity. Planta medica. 2008 Oct;74,1453-6. [CrossRef]

- Olarewaju, O.O.; Fajinmi, O.O.; Arthur, G.D.; Coopoosamy, R.M.; Naidoo, K.K. Food and medicinal relevance of Cucurbitaceae species in Eastern and Southern Africa. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Miyase, T.; Muregi, F.W.; Naoshima-Ishibashi, Y.; Umehara, K.; Warashina, T.; Kanou, S.; Mkoji, G.M.; Terada, M.; Ishih, A. Antiplasmodial Triterpenoids from Ekebergia capensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakudya, T.T.; Tshabalala, T.; Dangarembizi, R.; Erlwanger, K.H.; Ndhlala, A.R. The Potential Therapeutic Value of Medicinal Plants in the Management of Metabolic Disorders. Molecules 2020, 25, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, K.; Alqahtani, A.; Kim, M.-S.; Cho, J.-L.; Cui, P.H.; Li, C.G.; Groundwater, P.W.; Li, G.Q. Tetracyclic triterpenoids in herbal medicines and their activities in diabetes and its complications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 2406–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutschländer, M.; Lall, N.; Van de Venter, M.; Hussein, A. Hypoglycemic evaluation of a new triterpene and other compounds isolated from Euclea undulata Thunb. var. myrtina (Ebenaceae) root bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. Euclea undulata Thunb.: Review of its botany, ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and biological activities. Asian Pacific journal of tropical medicine. 2017 2017/11/01/;10,1030-1036. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lu, X.; El-Seedi, H.; Teng, H. Recent advances in the development of sesquiterpenoids in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaruk, J.; Borzym-Kluczyk, M. The role of triterpenes in the management of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Phytochem. Rev. 2014, 14, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbah, J.A.; Tane, P.; Ngadjui, B.T.; Connolly, J.D.; Okunji, C.C.; Iwu, M.M.; Schuster, B.M. Antiplasmodial Agents from the Leaves ofGlossocalyx brevipes. Planta Medica 2004, 70, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N, T.; E, F.; V, K.; R, J.; D, N.; Dj, S.; Telesphore, N.B. Ethnomedical and Ethnopharmacological Study of Plants Used by Indigenous People of Cameroon for The Treatments of Diabetes and its Signs, Symptoms and Complications. J. Mol. Biomarkers Diagn. 2016, 8, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickii, J.; Njifutie, N.; Foyere, J.A.; Basco, L.K.; Ringwald, P. In vitro antimalarial activity of limonoids from Khaya grandifoliola C.D.C. (Meliaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 69, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, O.E.; Akinpelu, O.B.; Bakare, A.A.; Yusuf, F.O.; Gomba, R.; Araka, D.C.; Ogundare, T.O.; Okolie, A.C.; Adebawo, O.; Odutola, O. Five traditional Nigerian Polyherbal remedies protect against high fructose fed, Streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes in male Wistar rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talontsi, F.M.; Lamshöft, M.; Bauer, J.O.; Razakarivony, A.A.; Andriamihaja, B.; Strohmann, C.; Spiteller, M. Antibacterial and Antiplasmodial Constituents of Beilschmiedia cryptocaryoides. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabo, H.K.; Tane, P.; Connolly, J.D. Diterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids from Aframomum arundinaceum. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2006, 34, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagar, M.; Ahmed, H.A.; Aljohani, G.; Alhaddad, O.A. Investigation of Some Antiviral N-Heterocycles as COVID 19 Drug: Molecular Docking and DFT Calculations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawale, F.; Iwaloye, O.; Elekofehinti, O.O. Virtual screening of natural compounds as selective inhibitors of polo-like kinase-1 at C-terminal polo box and N-terminal catalytic domain. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 40, 13606–13624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszek, A.M.; Reynisson, J. Defining Known Drug Space Using DFT. Mol. Informatics 2016, 35, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, M.; Raja, K.K.; Murugesan, S.; Kumar, B.K.; Rajagopal, G.; Thirunavukkarasu, S. Synthesis, biological evaluation, molecular docking, molecular dynamics and DFT studies of quinoline-fluoroproline amide hybrids. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1217, 128360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2000, 44, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyebi GA, Elfiky AA, Ogunyemi OM, et al. Structure-based virtual screening suggests inhibitors of 3-Chymotrypsin-Like Protease of SARS-CoV-2 from Vernonia amygdalina and Occinum gratissimum. Comput Biol Med. 2021 Sep;136:104671. [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawale, F.; Iwaloye, O.; Olofinsan, K.; Ogunyemi, O.M.; Gyebi, G.A.; Ibrahim, I.M. Homology modelling, vHTS, pharmacophore, molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies for the identification of natural compound-derived inhibitor of MRP3 in acute leukaemia treatment. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 3729–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salentin S, Schreiber S, Haupt V, et al. PLIP: Fully automated protein-ligand interaction profiler. Nucleic acids research. 2015 04/14;43. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker H, Berendsen H, Dijkstra E, et al., editors. Gromacs-a parallel computer for molecular-dynamics simulations. 4th International Conference on Computational Physics (PC 92); 1993: World Scientific Publishing.

- Oostenbrink, C.; Villa, A.; Mark, A.E.; Van Gunsteren, W.F. A biomolecular force field based on the free enthalpy of hydration and solvation: The GROMOS force-field parameter sets 53A5 and 53A6. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1656–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüttelkopf AW, Van Aalten DM. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein–ligand complexes. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography. 2004;60,1355-1363. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salentin, S.; Schreiber, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Adasme, M.F.; Schroeder, M. PLIP: Fully automated protein–ligand interaction profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W443–W447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller BR, 3rd, McGee TD, Jr., Swails JM, et al. MMPBSA.py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. Journal of chemical theory and computation. 2012 Sep 11;8,3314-21. [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Yang, F.; Wang, P.; Zheng, G.; Chen, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhu, F. What Contributes to Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors’ Dual-Targeting Mechanism? The Key Role of Transmembrane Domain 6 in Human Serotonin and Norepinephrine Transporters Revealed by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuccinardi, T. What is the current value of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods in drug discovery? Expert opinion on drug discovery. 2021 Nov;16,1233-1237. [CrossRef]

- Elekofehinti, O.O.; Iwaloye, O.; Olawale, F.; Chukwuemeka, P.O.; Folorunso, I.M. Newly designed compounds from scaffolds of known actives as inhibitors of survivin: computational analysis from the perspective of fragment-based drug design. Silico Pharmacol. 2021, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee P, Eckert AO, Schrey AK, et al. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic acids research. 2018 Jul 2;46(W1):W257-w263. [CrossRef]

| S/N | Compounds | Class | Dockingscore (Kcal/mol) | PostDocking MM-GBSA (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Alogliptin | -7.7 | -37.02 | |

| T1 | Cucurbitacin B | tetracyclic triterpenes | -9.9 | -47.80 |

| T2 | 20-Epi-isoiguesterinol | Bisnortriterpenes | -9.9 | -29.78 |

| T3 | Isoiguesterin | Bisnortriterpenes | -9.7 | -28.75 |

| T4 | 6-Oxoisoiguesterin | Bisnortriterpenes | -9.3 | -32.90 |

| T6 | Isoiguesterinol | Bisnortriterpenes | -9.0 | -29.36 |

| T7 | 1-Deacetylkhivorin | Limonoids | -8.9 | -19.72 |

| T8 | 7-Deacetylkhivorin | Limonoids | -8.8 | -25.71 |

| Compounds |

Hydrogen bonds (Bond lenght Å) |

Hydrophobic Interaction | Other interactions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Residues | No | Residues | No | Residues | |

| Alogliptin | 5 | ARG125(2.22;2.26) TRP629(2.37) HIS740(3.41) SER630(2.46) | 7 | TRP629(3.99;5.64;4.98) TYR547(4.21;4.99) HIS740(5.19) LYS554 | 1 | HIS740 |

| T1 | 7 | LYS554 ASN562(2) SER630(2) TYR631 HIS740 | 6 | TYR666(2) TYR547 TRP629(2) TYR662 | 0 | None |

| T4 | 3 | ARG125 TYR547 HIS740 | 7 | TYR547(2) TRP627(2) TRP629(2) HIS740 | 0 | None |

| T2 | 3 | TYR547 LYS544 ASP545 | 7 | TYR547(2) TRP627 TRP629(2) TYR662 HIS740 | 0 | None |

| S/N | Compounds | Class | Dockingscore (Kcal/mol) | Prime MM-GBSA (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2 | ISOTHIAZOLIDINONE | 9.8 | -85.23 | |

| T9 | Tsangibeilin B | Beilshmiedic acid derivatives | -8.4 | -42.32 |

| T10 | Cryptobeilic acid C | Beilshmiedic acid derivatives | -8.1 | -44.09 |

| T3 | Isoiguesterin | Bisnorterpenes | -7.5 | -42.07 |

| T4 | 6-Oxoisoiguesterin | Bisnorterpenes | -7.4 | -41.11 |

| T6 | Isoiguesterinol | Bisnorterpenes | -7.0 | -45.82 |

| T11 | Galanolactone | Clerodane and labdanediterpenoids | -6.5 | -43.56 |

| T2 | 20-Epi-isoiguesterinol | Bisnorterpenes | -6.2 | -29.06 |

| Compounds |

Hydrogen bonds (Bond length Å) |

Hydrophobic Interaction | Other interactions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Residues | No | Residues | No | Residues | |

| S2 |

11 |

ARG47(2.01) CYS215(3.04) SER216(1.96) ALA217(2.25) GLY218(3.02) ILE219(2.36) GLY220(2.02) ARG221(2.05) GLN266(1.99) ASP48(1.88; 2.63) | 3 | ALA217(3.75) PHE182(4.81) ARG47(5.37) | 1 | ASP48(3.87) |

| T6 |

4 |

ARG47 LYS120 SER216(2) | 7 | PHE182(3) ALA217(2) ILE219 TYR46 | 0 | None |

| T10 |

4 |

LYS120(2.76;2.98) ARG221(2.13; 2.06) | 8 | PHE182(4.68;5.45) ALA217(5.49; 4.26) ARG221(3.74) TYR46(4.75; 4.03) ILE219(5.15) | 2 | ASP181 (3.82) CYS215(4.90) |

| T11 |

5 |

SER216(2.36;3.08) ALA217(2.22) ARG221(2.28) GLN262(3.79) | 6 | ALA217(4.12) ILE219(4.82) TYR46(4.73; 4.06) PHE182 (5.07; 4.48) | 0 | None |

| SYSTEM | ΔVDWAALS | ΔEEL | ΔEGB | ΔESURF | ΔGGAS | ΔGSOLV | ΔTOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | -34.67 ± 3.39 | -18.69 ± 7.22 | 46.29 ± 6.49 | -4.79 ± 0.43 | -53.35 ± 7.49 | 41.5 ± 6.35 | -11.85 ± 3.34 |

| T4 | -22.20 ± 3.38 | -7.25 ± 12.28 | 25.02 ± 10.43 | -2.82 ± 0.65 | -29.44 ± 13.02 | 22.2 ± 10.09 | -7.24 ± 4.62 |

| T2 | -30.73 ± 5.27 | 125.46 ± 28.01 | -93.17 ± 30.7 | -3.82 ± 0.66 | 94.73 ± 31.83 | -96.99 ± 30.24 | -2.26 ± 3.64 |

| S1 | -22.63 ± 4.15 | -304.75 ± 33.46 | 312.75 ± 28.86 | -3.28 ± 0.53 | -327.39 ± 33.19 | 309.48 ± 28.53 | -17.91 ± 6.42 |

| HOMO | LUMO | Band gap | Electronegativity | Ionization potential |

Electron affinity |

Hardness | softness | Chemical potential |

Electrophilicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | -0.20306 | 0.06017 | 0.26323 | 0.071445 | 0.20306 | -0.06017 | 0.131615 | 3.798959 | -0.07145 | 0.002552 |

| T1 | -0.24354 | 0.04816 | 0.29170 | 0.097690 | 0.24354 | -0.04816 | 0.145850 | 3.428180 | -0.09769 | 0.004772 |

| T4 | -0.24676 | 0.05232 | 0.29908 | 0.09722 | 0.24676 | -0.05232 | 0.14954 | 3.343587 | -0.09722 | 0.004726 |

| T2 | -0.24692 | 0.05377 | 0.30069 | 0.096575 | 0.24692 | -0.05377 | 0.150345 | 3.325684 | -0.09658 | 0.004663 |

| Terpenoids | Cucurbitacin B | 20-Epi-isoiguesterinol | 6-Oxoisoiguesterin |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 558.7 | 422.6 | 420.58 |

| #Rotatable bonds | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| #H-bond acceptors | 8 | 3 | 3 |

| #H-bond donors | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| TPSA | 138.2 | 57.53 | 57.53 |

| ESOL Class | MS | MS | PS |

| Lipinski violations | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ghose violations | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Veber violations | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Egan violations | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Muegge violations | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| PAINS alerts | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Brenk alerts | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Synthetic Accessibility | 6.79 | 6.29 | 5.21 |

| GI absorption | Low | High | High |

| BBB permeant | No | No | No |

| Pgp substrate | Yes | No | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | Yes | Yes |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).