Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

01 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

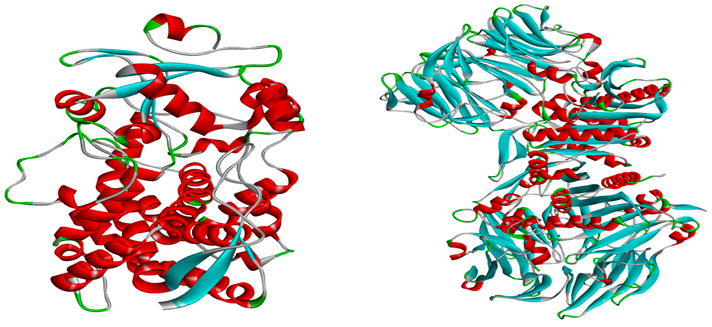

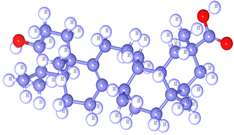

2.1. Structure optimization

2.2. Lipinski rule, Pharmacokinetics and Drug likeness

2.3. Molecular docking

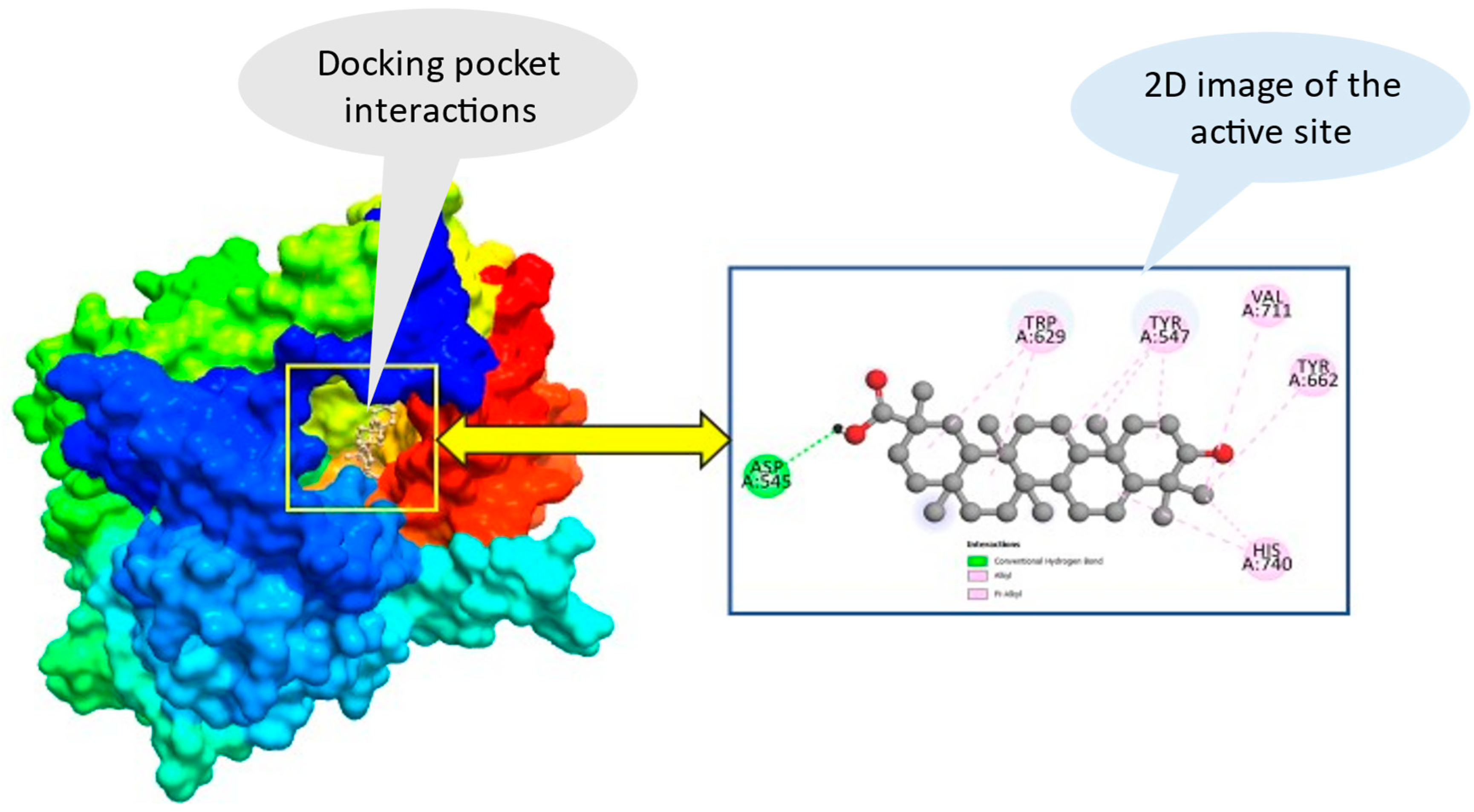

2.4. Ligand-protein interaction and molecular docking poses

2.5. ADMET studies

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Optimization and Ligand preparation

4.2. Protein preparation and Molecular Docking study

4.3. Lipinski rule, Pharmacokinetics and Drug likeness

4.4. ADMET Properties

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimmet, P.Z.; Magliano, D.J.; Herman, W.H.; Shaw, J.E. Diabetes: A 21st Century Challenge. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014, 2, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, D.R.; Guariguata, L.; Weil, C.; Shaw, J. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global Estimates of the Prevalence of Diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011, 94, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Magliano, D.J.; Zimmet, P.Z. The Worldwide Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—Present and Future Perspectives. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012, 8, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valodara, A.; Johar SR, K. TYPE 2 DIABETES MELLITUS AND ITS VASCULAR COMPLICATIONS. Towards Excellence 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Brown, J.; Vistisen, D.; Sicree, R.; Shaw, J.; Nichols, G. Global Healthcare Expenditure on Diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010, 87, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad-Elkareem, M.A.M.; Abdelgadir, E.H.; Badawy, O.M.; Kadri, A. Potential Antidiabetic Effect of Ethanolic and Aqueous-Ethanolic Extracts of Ricinus Communis Leaves on Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in Rats. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. SDF-1α and CXCR4 as Therapeutic Targets in Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2012, 2, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Ramen, C.B.; Manas, C. An Overview on Management of Diabetic Dyslipidemia. Journal of Diabetes and Endocrinology 2013, 4, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Parhofer, K.G. Diabetic Dyslipidemia. Metabolism 2014, 63, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, S.A.; Kasetti, R.B.; Sirasanagandla, S.; Tilak, T.K.; Kumar, M.V.J.; Rao, C.A. Antidiabetic and Antihyperlipidemic Activity of Piper Longum Root Aqueous Extract in STZ Induced Diabetic Rats. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.C.; Cull, C.A.; Frighi, V.; Holman, R.R.; Group, U.K.P.D.S. (UKPDS); Group, U.K.P.D.S. (UKPDS). Glycemic Control with Diet, Sulfonylurea, Metformin, or Insulin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Progressive Requirement for Multiple Therapies (UKPDS 49). JAMA 1999, 281, 2005–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erejuwa, O.O. Oxidative Stress in Diabetes Mellitus: Is There a Role for Hypoglycemic Drugs and/or Antioxidants. Oxidative stress and diseases 2012, 217, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, A. Recent Advances on Novel Dual-Acting Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha and Gamma Agonists. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2013, 4, 1644. [Google Scholar]

- Marles, R.J.; Farnsworth, N.R. Antidiabetic Plants and Their Active Constituents. Phytomedicine 1995, 2, 137–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.U.; Sreenivasulu, M.; Chengaiah, B.; Reddy, K.J.; Chetty, C.M. Herbal Medicines for Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Int J PharmTech Res 2010, 2, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar]

- Minocha, S. An Overview on Lagenaria Siceraria (Bottle Gourd). Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Research 2015, 4, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Beevy, S.S.; Kuriachan, P. Chromosome Numbers of South Indian Cucurbitaceae and a Note on the Cytological Evolution in the Family. J Cytol Genet 1996, 31, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, Y.; Maundu, P.; Fujimaki, H.; Morishima, H. Diversity of Landraces of the White-Flowered Gourd (Lagenaria Siceraria) and Its Wild Relatives in Kenya: Fruit and Seed Morphology. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2005, 52, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashilo, J.; Shimelis, H.; Odindo, A. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Bottle Gourd [Lagenaria Siceraria (Molina) Standl.] and Implications for Breeding: A Review. Sci Hortic 2017, 222, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, H.C.; Whitaker, T.W. Cucurbits from the Tehuacan Caves; University of Texas Press, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Upaganlawar, A.; Balaraman, R. Bottle Gourd (Lagenaria Siceraria) A Vegetable Food for Human Health-a Comprehensive Review. Pharmacol online 2009, 1, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, S.S.; Mohale, D.S.; Ghule, B. v; Saoji, A.N.; Yeole, P.G. Studies on the Antihyperlipidemic Activity of Flavonoidal Fraction of Lagenaria Siceraria. International Journal of Chemical Sciences 2008, 6, 751–760. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, J.A. Handbook of Biologically Active Phytochemicals and Their Activities; CRC Press, Inc., 1992; ISBN 0849336708. [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni, K.M. Indian Materia Medica, Bombay Popular Prakashan. Mumbai VI 1954, 629. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk, B.-E.; Gericke, N. People’s Plants: A Guide to Useful Plants of Southern Africa; Briza publications, 2000; ISBN 1875093192. [Google Scholar]

- Abdin, M.Z.; Arya, L.; Saha, D.; Sureja, A.K.; Pandey, C.; Verma, M. Population Structure and Genetic Diversity in Bottle Gourd [Lagenaria Siceraria (Mol.) Standl.] Germplasm from India Assessed by ISSR Markers. Plant systematics and evolution 2014, 300, 767–773. [Google Scholar]

- Akash, S.; Chakma, U.; Chandro, A.; Matin, M.M.; Howlader, D. The Computational Screening of Inhibitor for Black Fungus and White Fungus by D-Glucofuranose Derivatives Using in Silico and SAR Study. Org. Commun 2021, 14, 336–353. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A.; McGaughey, G.B.; Sheridan, R.P.; Good, A.C.; Warren, G.; Mathieu, M.; Muchmore, S.W.; Brown, S.P.; Grant, J.A.; Haigh, J.A. Molecular Shape and Medicinal Chemistry: A Perspective. J Med Chem 2010, 53, 3862–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortemme, T.; Baker, D. A Simple Physical Model for Binding Energy Hot Spots in Protein–Protein Complexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 14116–14121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahire, E.D.; Sonawane, V.N.; Surana, K.R.; Talele, G.S. Drug Discovery, Drug-Likeness Screening, and Bioavailability: Development of Drug-Likeness Rule for Natural Products. In Applied pharmaceutical practice and nutraceuticals; Apple Academic Press, 2021; pp. 191–208. ISBN 1003054897. [Google Scholar]

- Kumer, A.; Chakma, U.; Rana, M.M.; Chandro, A.; Akash, S.; Elseehy, M.M.; Albogami, S.; El-Shehawi, A.M. Investigation of the New Inhibitors by Sulfadiazine and Modified Derivatives of α-d-Glucopyranoside for White Spot Syndrome Virus Disease of Shrimp by in Silico: Quantum Calculations, Molecular Docking, ADMET and Molecular Dynamics Study. Molecules 2022, 27, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Abbasi, H.W.; Shahid, S.; Gul, S.; Abbasi, S.W. Molecular Docking, Simulation and MM-PBSA Studies of Nigella Sativa Compounds: A Computational Quest to Identify Potential Natural Antiviral for COVID-19 Treatment. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2021, 39, 4225–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M. Design, Synthesis and ADMET Prediction of Bis-Benzimidazole as Anticancer Agent. Bioorg Chem 2020, 96, 103576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, W.P. Going Further than Lipinski’s Rule in Drug Design. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2012, 7, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Kenakin, T.; Blackburn, T. Pharmacology for Chemists: Drug Discovery in Context; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2017; ISBN 1782621423. [Google Scholar]

- Tallei, T.E.; Tumilaar, S.G.; Niode, N.J.; Kepel, B.J.; Idroes, R.; Effendi, Y.; Sakib, S.A.; Emran, T. Bin Potential of Plant Bioactive Compounds as SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (M pro) and Spike (S) Glycoprotein Inhibitors: A Molecular Docking Study. Scientifica (Cairo) 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lionta, E.; Spyrou, G.; K Vassilatis, D.; Cournia, Z. Structure-Based Virtual Screening for Drug Discovery: Principles, Applications and Recent Advances. Curr Top Med Chem 2014, 14, 1923–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, J.; Rechenmacher, F.; Kessler, H. N-methylation of Peptides and Proteins: An Important Element for Modulating Biological Functions. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2013, 52, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; An, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, S.; Lv, H.; Wang, S. Drug-Target Interaction Prediction Based on Multisource Information Weighted Fusion. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Helby, A.A.; Ayyad, R.R.A.; Zayed, M.F.; Abulkhair, H.S.; Elkady, H.; El-Adl, K. Design, Synthesis, in Silico ADMET Profile and GABA-A Docking of Novel Phthalazines as Potent Anticonvulsants. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2019, 352, 1800387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkaeed, E.B.; Elkady, H.; Belal, A.; Alsfouk, B.A.; Ibrahim, T.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.; Arafa, R.K.; Metwaly, A.M.; Eissa, I.H. Multi-Phase in Silico Discovery of Potential SARS-CoV-2 RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Inhibitors among 3009 Clinical and FDA-Approved Related Drugs. Processes 2022, 10, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Gasch, T.; Stahl, M. Binding Site Characteristics in Structure-Based Virtual Screening: Evaluation of Current Docking Tools. J Mol Model 2003, 9, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; Sanschagrin, P.C.; Mainz, D.T. Extra Precision Glide: Docking and Scoring Incorporating a Model of Hydrophobic Enclosure for Protein− Ligand Complexes. J Med Chem 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantsar, T.; Poso, A. Binding Affinity via Docking: Fact and Fiction. Molecules 2018, 23, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumer, A.; Chakma, U.; Matin, M.M.; Akash, S.; Chando, A.; Howlader, D. The Computational Screening of Inhibitor for Black Fungus and White Fungus by D-Glucofuranose Derivatives Using in Silico and SAR Study. Organic Communications 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Islam, M.; Akash, S.; Mim, S.; Rahaman, M.; Bin Emran, T.; AKKOL, E.; Sharma, R.; Alhumaydhi, F.; Sweilam, S. In Silico Investigation and Potential Therapeutic Approaches of Natural Products for COVID-19: Computer-Aided Drug Design Perspective. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, B.; Cosconati, S.; Gabelica, V.; Petraccone, L.; De Tito, S.; Marinelli, L.; La Pietra, V.; Saverio di Leva, F.; Lauri, I.; Trotta, R. State-of-the-Art Methodologies for the Discovery and Characterization of DNA G-Quadruplex Binders. Curr Pharm Des 2012, 18, 1880–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.I. A Simple Principle for Understanding the Combined Cellular Protein Folding and Aggregation. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2020, 21, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hann, M.M.; Leach, A.R.; Harper, G. Molecular Complexity and Its Impact on the Probability of Finding Leads for Drug Discovery. J Chem Inf Comput Sci 2001, 41, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohlke, H.; Klebe, G. Approaches to the Description and Prediction of the Binding Affinity of Small-molecule Ligands to Macromolecular Receptors. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2002, 41, 2644–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. In Silico ADMET Prediction: Recent Advances, Current Challenges and Future Trends. Curr Top Med Chem 2013, 13, 1273–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, N.E.-H.; Borah, P.; Deb, P.K.; Venugopala, K.N.; Hourani, W.; Alzweiri, M.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Tiwari, V. ADMET Profiling in Drug Discovery and Development: Perspectives of in Silico, in Vitro and Integrated Approaches. Curr Drug Metab 2021, 22, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P.; Hazarika, S.; Deka, S.; Venugopala, K.N.; Nair, A.B.; Attimarad, M.; Sreeharsha, N.; Mailavaram, R.P. Application of Advanced Technologies in Natural Product Research: A Review with Special Emphasis on ADMET Profiling. Curr Drug Metab 2020, 21, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E. V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. PkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.W.A. Software Review of ChemBioDraw 12.0 2010.

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An Advanced Semantic Chemical Editor, Visualization, and Analysis Platform. J Cheminform 2012, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead-and Drug-like Compounds: The Rule-of-Five Revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Sevrioukova, I.F.; Denisov, I.G.; Zhang, X.; Chiu, T.-L.; Thomas, D.G.; Hanse, E.A.; Cuellar, R.A.D.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Langenfeld, V.W. Heme Binding Biguanides Target Cytochrome P450-Dependent Cancer Cell Mitochondria. Cell Chem Biol 2017, 24, 1259–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, J.M.; Clark, D.E.; Dunsdon, S.J.; Fenton, G.; Fillmore, A.; Harris, N.V.; Higgs, C.; Hurley, C.A.; Krintel, S.L.; MacKenzie, R.E. Novel Heterocyclic DPP-4 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2012, 22, 1464–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S. Biologics: An Update and Challenge of Their Pharmacokinetics. Curr Drug Metab 2014, 15, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

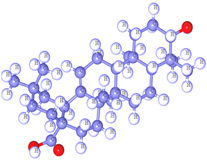

Bryonolic acid

|

L-ascorbic acid

|

Bryonolol

|

Bryononic acid |

Cucurbitacin G

|

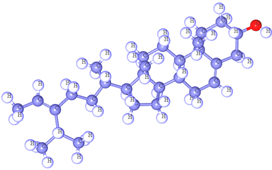

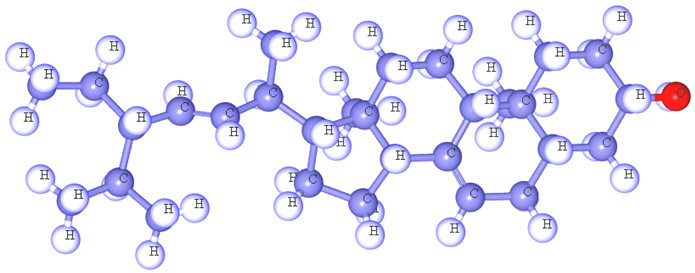

Fucosterol

|

Hesperidin

|

Isofucosterol

|

Oleanolic acid

|

Spinasterol

| ||

| Ligand No. | Parameters of Lipinski rule, Pharmacokinetics and Drug likeness | |||||||

| PubChem ID | Molecular weight (Dalton) | Hydrogen bond acceptor | Hydrogen bond donor | Topological polar surface area (Ų) | Lipinski rule | Bioavailability Score | ||

| Result | violation | |||||||

| 01 | 159970 | 456.7 | 3 | 2 | 57.53 | Yes | 1 | 0.85 |

| 02 | 54670067 | 176.12 | 6 | 4 | 107.22 | Yes | 0 | 0.55 |

| 03 | 15756408 | 442.72 | 2 | 2 | 40.46 | Yes | 1 | 0.55 |

| 04 | 472768 | 456.7 | 3 | 2 | 57.53 | Yes | 1 | 0.85 |

| 05 | 441818 | 534.68 | 8 | 5 | 152.36 | Yes | 1 | 0.55 |

| 06 | 5281328 | 412.69 | 1 | 1 | 20.23 | Yes | 1 | 0.55 |

| 07 | 10621 | 610.56 | 15 | 8 | 234.29 | No | 3 | 0.17 |

| 08 | 5281326 | 412.69 | 1 | 1 | 20.23 | Yes | 1 | 0.55 |

| 09 | 10494 | 456.7 | 3 | 2 | 57.53 | Yes | 1 | 0.85 |

| 10 | 5281331 | 412.69 | 1 | 1 | 20.23 | Yes | 1 | 0.55 |

| No | Name | PubChem CID | Human CYP3A4 bound to metformin (PDB ID: 5G5J) | Human dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (PDB ID: 4A5S) |

| Binding affinity (Kcal/mol) | Binding affinity (Kcal/mol) | |||

| 01 | Bryonolic acid | 159970 | -9.3 | -9.7 |

| 02 | L-ascorbic acid | 54670067 | -9.9 | -9.1 |

| 03 | Bryonolol | 15756408 | -8.3 | -9.5 |

| 04 | Bryononic acid | 472768 | -9.7 | -9.2 |

| 05 | Cucurbitacin G | 441818 | -9.6 | -9.0 |

| 06 | Fucosterol | 5281328 | -9.9 | -9.1 |

| 07 | Hesperidin | 10621 | -10.7 | -9.7 |

| 08 | Isofucosterol | 5281326 | -9.2 | -9.3 |

| 09 | Oleanolic acid | 10494 | -9.1 | -9.1 |

| 10 | Spinasterol | 5281331 | -9.5 | -9.2 |

| Metformin hydrochloride | 14219 | -6.3 | -6.7 | |

| Sl. No | Absorption | Distribution | Metabolism | Excretion | ||||||||

| Water solubility LogS | Caco-2 permeability | Human Intestinal Absorption (%) | VDss (human) | BBB Permeability | CYP450 1A2 Inhibitor | CYP 450 2C9 Substrate | CYP450 3A4 Substrate | CYP450 3A4 Inhibitor | Total Clearance (mL/min/kg) |

Renal OCT2 substrate | ||

| 01 | -3.45 | 1.14 | 98.11 | -0.853 | No | No | No | Yes | No | -0.036 | No | |

| 02 | -1.55 | -0.25 | 39.15 | 0.218 | No | No | No | No | No | 0.631 | No | |

| 03 | -6.33 | 1.1 | 92.03 | 0.338 | No | No | No | Yes | No | 0.067 | No | |

| 04 | -3.46 | 1.15 | 98.42 | -0.799 | No | No | No | Yes | No | -0.036 | No | |

| 05 | -4.42 | 0.43 | 69.47 | -0.398 | No | No | No | No | No | 0.322 | No | |

| 06 | -6.75 | 1.21 | 94.64 | 0.179 | No | No | No | Yes | No | 0.619 | No | |

| 07 | -3.01 | 0.50 | 31.48 | 0.996 | No | No | No | No | No | 0.211 | No | |

| 08 | -6.71 | 1.21 | 94.64 | 0.179 | No | No | No | Yes | No | 0.619 | No | |

| 09 | -3.26 | 1.16 | 99.55 | -1.009 | No | No | No | Yes | No | -0.081 | No | |

| 10 | -6.68 | 1.21 | 94.97 | 0.178 | No | No | No | Yes | No | 0.611 | No | |

| Sl. No. | Compound name | AMES toxicity | Max. tolerated dose (human) mg/kg/day |

Oral Rat Acute Toxicity (LD50) (mol/kg) | Oral Rat Chronic Toxicity (mg/kg/day) |

Hepatotoxicity | Skin Sensitization |

| 01 | Bryonolic acid | No | 0.098 | 2.294 | 2.065 | Yes | No |

| 02 | L-ascorbic acid | No | 1.598 | 1.063 | 3.186 | No | No |

| 03 | Bryonolol | No | -0.863 | 2.213 | 2.031 | No | No |

| 04 | Bryononic acid | No | 0.098 | 2.294 | 2.065 | Yes | No |

| 05 | Cucurbitacin G | Yes | -0.461 | 2.502 | 2.001 | No | No |

| 06 | Fucosterol | No | -0.653 | 2.553 | 0.89 | No | No |

| 07 | Hesperidin | No | 0.525 | 2.506 | 3.167 | No | No |

| 08 | Isofucosterol | No | -0.653 | 2.553 | 0.89 | No | No |

| 09 | Oleanolic acid | No | 0.094 | 2.196 | 2.109 | Yes | No |

| 10 | Spinasterol | No | -0.664 | 2.54 | 0.872 | No | No |

| Metformin hydrochloride | Yes | 0.874 | 2.465 | 2.122 | No | Yes | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).