Introduction

The study of synchronization began with Huygens. As the number of studies on collective behavior in complex systems has grown, synchronization in coupled systems has garnered extensive attention1. Synchronization in complex systems2, e.g., synchronous discharge, the flashing of fireflies, and the synchronization of generators, is widely observed in nature and industry.

It is widely believed that networks are closely related to spontaneous synchronization2. Current research on the synchronization of complex networks is based on concepts from graph theory and statistical physics, such as the connectivity of the graph and the nodal degree2. To analyze synchronization behaviors of complex networks, these approaches require clear information about the network structure and simplify the interactions between individuals into a coupled network. However, this is difficult to achieve in practice3,4, as realistic interactions often cannot be observed. The complexity of real networks can also make topological information incomplete5. Additionally, overly large networks make clear topology modeling quite difficult. These challenges can lead to incorrect network reconfiguration and link predictions. Even if complete information regarding the network topology is obtained, other difficulties, such as the diversity of networks and community structures, uncertain dynamics and nonlinear network parameters, are often encountered simultaneously in real networks. These difficulties present substantial obstacles for the study of network synchronization.

To overcome the abovementioned difficulties, a network-independent synchronization analysis path is constructed for generator synchronization in power systems in this paper. Power systems are the largest man-made systems and are considered to be typical complex network systems. Therefore, the study of the synchronization behavior of generators in power grids is of critical importance not only for the stable operation of power systems but also for the wider field of synchronization of complex networks1,2. The approach in this paper identifies collective synchronization and those individuals not participating in it, based solely on the behavior of each individual in the system. In particular, this method reveals how individuals in the network are synchronized while ignoring the network structure. This approach has been experimentally verified for the realistic power grid systems.

Synchronization is a prerequisite for the normal operation of a power grid6. Large power systems are complex coupled systems where nonlinearities and uncertainties coexist7. To analyze the synchronization of generators, numerous insightful methods are being developed1,8–12, including the determination of synchronous stability boundaries13–15 and the use of spontaneous synchronization conditions2.

The identification of the synchronous stability boundary of a system is a key unresolved problem14,16,17. A stablity boundary is the union of critical points18, and when the system state is outside the stability boundary, it is desynchronized15. The boundary, which is a core concept of grid stability, is closely related to many other issues encountered in power systems19–21. Therefore, investigations of synchronous stability boundaries can make a significant impact on the development of power systems and the synchronization stability of complex networks. The derivation of an analytical equation that can describe a boundary has been a long-standing research goal in the field of power systems13,14,22. However, current research is still limited by the nonlinearity and uncertainty of power systems. On the other hand, the spontaneous synchronization of complex systems has been utilized to elucidate the synchronized operation of generators in interconnected grids23. Therefore, many studies on power system stability are based on the knowledge of synchronization conditions of complex networks2,23,24. However, this scheme is in some cases considered to oversimplify real systems9,23, and it has been argued that self-organization is not relevant for a power grid9.

Here, an equation is derived and visualized based on a succinct consensus. The equation describes the synchronous stability boundary of a power system in a unified manner and has elegant formal and physical interpretations. I started by showing the validity of the boundary equation with three pieces of evidences. These evidences demonstrate that this approach addresses the problems of the multiswing stability discrimination of multiple generators in a power system and partial synchronization. Subsequently, I demonstrated that the synchronous stability boundary is independent of the network structure and parameters. It is also shown here that the synchronization stability of the power system is determined by the amplitude, while the conclusion that both symmetry and asymmetry promote synchronization is discussed. In addition, by comparing the boundary with the location of synchronization occurred, I observed that spontaneous synchronization occurs only close to the boundary and is manifested as a specific structure. This represents the first clear evidence of spontaneous synchronization in a power system. Moreover, this close connection suggests that, like the synchronous stability boundary, the spontaneous synchronization on a network is also not directly related to the network. This novel approach is developed to investigate the synchronization of complex networks, taking into account potential scenarios of realistic network complexity, nonlinearity, or uncertainty. The conclusion in this paper may inspire advances in other disciplines.

Stability Boundary

Synchronization occurs when the coupling dominates the dissimilarity2. Currently2, the coupling is typically quantified by graph theory, and the dissimilarity is quantified by the frequencies . In this work, it is assumed that the coupling is quantified by the coupling power and the dissimilarity is quantified by the dissimilar power. When the generators are synchronized, there is no dissimilarity, meaning the dissimilar power is 0. The coupling power is denoted as PΔu and the dissimilar power is denoted as P∂u. That is, when , the system is synchronous and stable, otherwise it is out of synchronization. Therefore, PΔu = P∂u represents the synchronous stability boundary. This assumption quantifies the interactions between individuals and is not based on graph theory or statistical physics concepts.

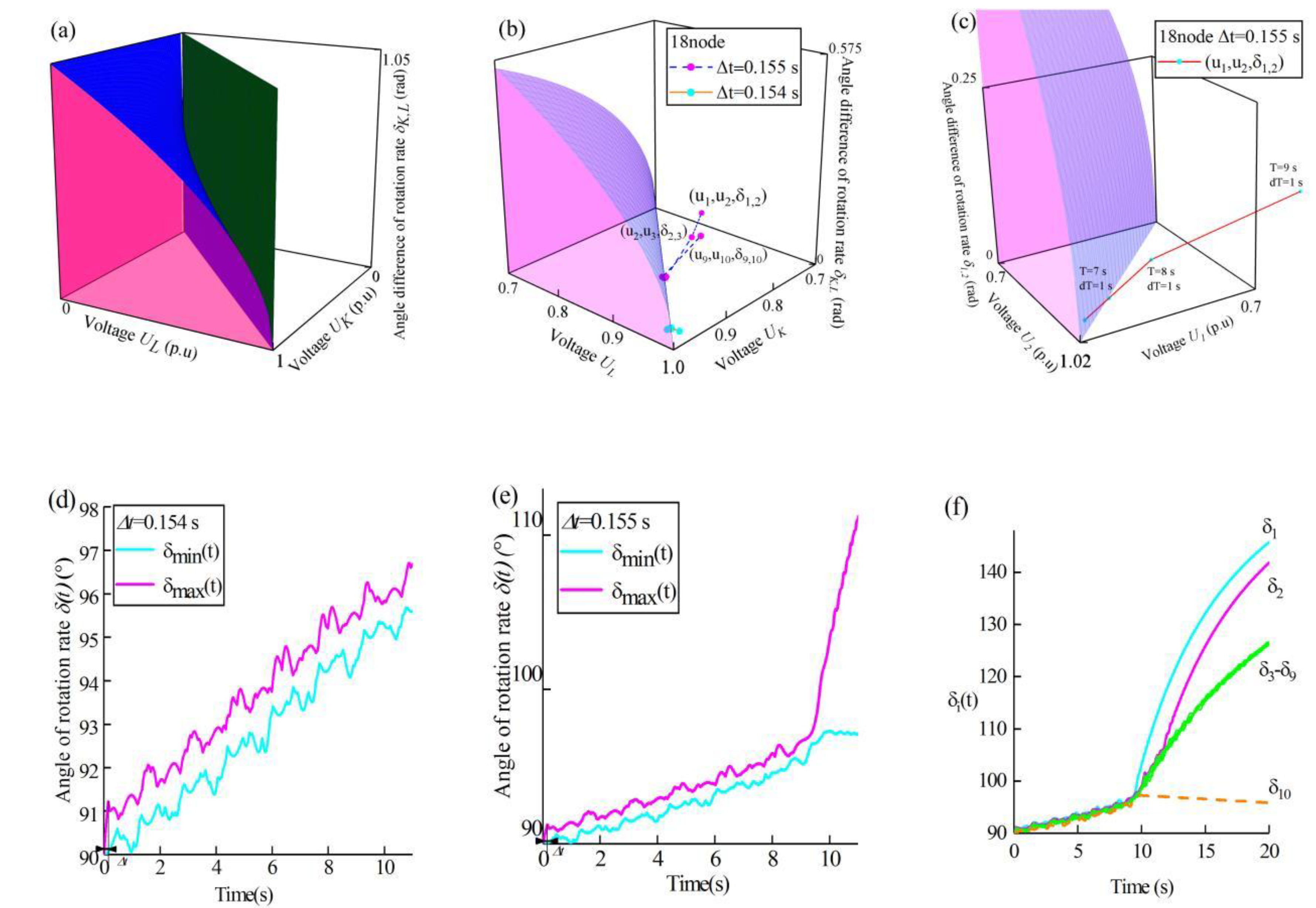

The boundary equation is expressed as follows:

where

. Eq. (1) is the specific expression of

in the power system.

Here, denote the voltages per unit of the Kth and Lth meta-generators, respectively. The amplitude, which in this context refers to voltage, has been previously overlooked for simplicity9,23 but is crucial for the synchronization stability of the grid. is the rotor speed per unit of the ith meta-generator, which is a normalization quantity commonly used in power system studies. is defined as the angle of rotation rate of the Kth meta-generator. The angle difference of rotation rate between the Kth and Lth meta-generators is . It is important to note that is not a phase and that . According to the definition of synchronization, .

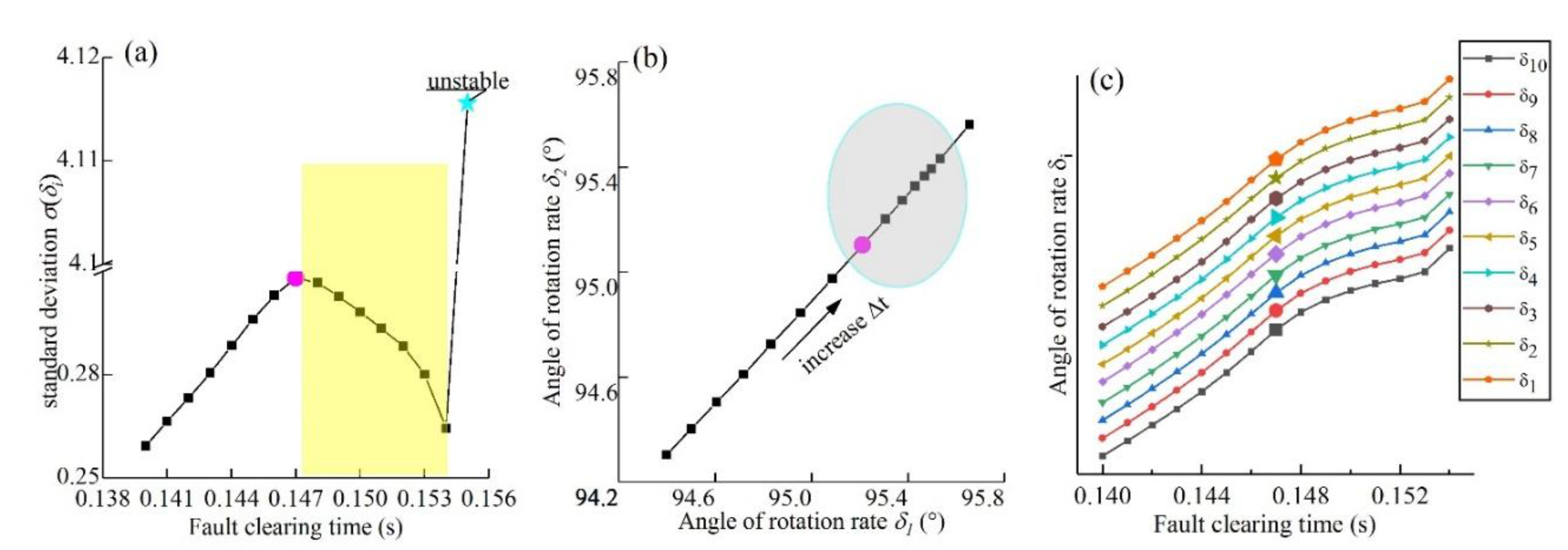

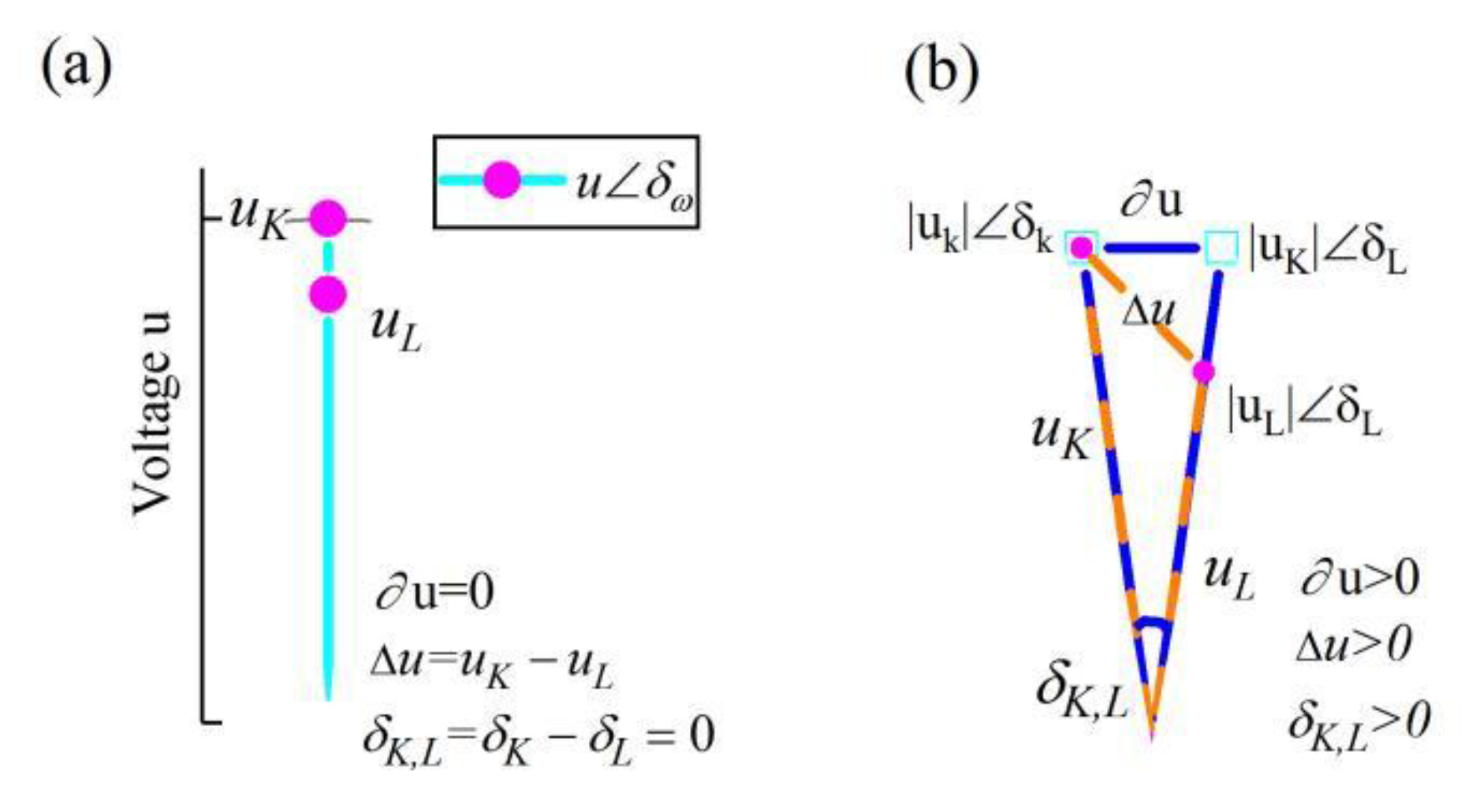

(a). Visualization of the stability boundary. The stability boundary in Eq. (1) (blue surface and dark green plane) and the pink planes , and collectively define the boundaries and enclose the stability domain.

(b). Synchronization stabilization discrimination. The dark green plane is not shown. is the fault clearing time. is defined as the coordinate of the coupling point of the Kth and Lth meta-generators, and it is computed from and . denotes the step length commonly used in power system studies. The coupling points in panel (b) are calculated using Eqs. (S3) and (S4).

(c). The disturbed trajectory of (). Each cyan point represents the mean position of for a period of 1 second. The time T=8 s and the time interval are defined in Eq. (S5).

(d) and (e). The results of the numerical experiment. The horizontal axis represents the time. The maximum value of is represented by the magenta curve, and the minimum value is represented by the cyan curve. . At 11 second, in (d), and in (e). As illustrated in panel (d), the values of all meta-generators are close to each other and have approximately the same rate of change. panel (e) shows that in the time interval (9 s, 10 s), increases sharply, indicating generator desynchronization.

(f). The phenomenon of partial synchronization and the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators. . After approximately 9 seconds, meta-generator 1 disengages from the cluster (cyan line). Subsequently, meta-generators 10 (magenta line) and 2 (orange dashed line) are separated. Meta-generators 3~9 form a synchronized cluster (green lines). in panels (d), (e) and (f) are calculated using simulation software and Eq. (S2).

Three pieces of evidence demonstrate that Eq. (1) effectively describes the synchronization stability boundary: 1) the boundary effectively distinguishes between stable and unstable states of the power system [see Figs. 1(b) and S1(a)], 2) the stability of multiple swings [see Figs. 1(c) and S1(b)], and 3) the partial synchronization phenomenon [see Figs. 1(f) and S1(e)].

Figure 1(b) illustrates that the synchronization stability boundary effectively differentiates between synchronized and desynchronized states.. A system comprising n meta-generators possesses n-1 coupling points. The behavior of the cyan and magenta dots is significantly different, despite the slight difference in

(Fig. 1(b)). When

, all of the cyan coupling points are clustered at the boundary. When

, the three magenta coupling points, i.e., (

u1,

u2,

δ1,2), (

u2,

u3,

δ2,3), and (

u9,

u10,

δ9,10), are outside the boundary and away from the rest of points. As mentioned above, when

, the coupling point

is outside the boundary and the power system is out of synchronization. Consequently, it is concluded that the system is stable at

and out of synchronization at

. The results in Figs. 1(d) and (e) are in good agreement with this conclusion. Additional analogous results can be found in Fig. S8.

Furthermore, utilizing Fig. 1(b) facilitates easily identify different synchronization patterns as it provides specific information about synchronized and desynchronized individual meta-generators or groups of meta-generators. The New England test system comprises 10 meta-generators, which is equivalent to 9 coupling points. As shown in Fig. 1(b), the 3 coupling points , and are outside the boundary while the rest of the points are clustered near the boundary. This signify that the meta-generators are divided into 4 synchronization groups. Specifically, outside the boundary means that the meta-generators 1 and 2 are not synchronized. There are analogous conclusions for and . That is, the meta-generators numbered 1, 2 and 10 are out of synchronization while the other meta-generators remain synchronized. This indicates that the meta-generators in each group are also clearly shown in Fig. 1(b). The result for the meta-generator synchronization group shown in Fig. 1(f) is in good agreement with those presented in Fig. 1(b). This is the phenomenon of partial synchronization. These results suggest that the partial synchronization phenomenon25–28 is caused by the loss of synchronization stability among these individuals or groups. This interpretation will deepen our understanding of the complex phenomenon of partial synchronization.

Figure 1 (c) clearly shows the transition of the power system from stabilization to instability. As shown in Fig. 1(c), (u1, u2, δ1,2) crosses the boundary outwardly during the time interval . Subsequently, increases dramatically during the time interval . (9 s, 10 s) These results are in good agreement with the simulation result presented in Fig. 1(e). The simulation result demonstrate s that the system loses synchronization during the aforementioned time interval . Therefore, the time at which the coupling point crosses the boundary is the onset of synchronization loss. These results pertain to the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators, an important issue that has not been resolved to date29,30. The above results demonstrate the synchronization stability boundary expressed by Eq.(1) can discriminate the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators in real time. More importantly, this finding suggests that the synchronous stability boundary and the multimachine multiswing stability boundary are, in fact, identical. This result helps analyze the synchronous stability of the power system in a unified way.

The numerical experimental results in Figs. 1(d), (e) and (f) are time-series data independently calculated by the simulation software. The results in Figs. 1(b) and (c) are in good agreement with these experimental data. The above results provide solid evidences for the correctness and validity of the boundary equation from various perspectives.

As shown in Fig. 1(a), geometrically, Eq. (1) represents two surfaces in a coordinate system . The left-hand side of Eq. (1) corresponds to a plane (dark green) perpendicular to the plane , and the right-hand side corresponds to a curve surface (blue). These two surfaces are clearly fixed, i.e., they are independent of network topology and parameters. Therefore, Eq. (1) is independent of the network topology, system parameters, perturbations and number of subsystems. This finding, which contradicts previous reports2,13,14, indicates that the stability boundary is independent of these factors. I emphasized that , not PΔu and P∂u, is independent of the network topology. The impact of the network is nullified through division (refer to “Derivation of the boundary equation”).

The most straightforward method to prove that “the boundary is independent of the network” is to test whether Eq. (1) holds true for a completely different network. Analogous results were obtained for the 3-generator test system using the same procedure (see Fig. S1). Fig. 1 shows the results of the simulation with the New England test system, whereas the results in Fig. S1 are from the 3-generator test system. The New England test system and 3-gen are two completely different network systems. They clearly have completely different topologies and parameters, but in both cases, the same boundary equation is applied. This is because the aforementioned evidence can be reproduced in the 3-generator test system. Both Fig. S1(a) and Fig. 1(b) correspond to evidence 1) mentioned above. Both Fig. S1(b) and Fig. 1(c) correspond to evidence 2). Both Fig. S1(e) and Fig. 1(f) correspond to evidence 3). Consequently, a comparison of Figs. 1 and S1 reveals that Eq. (1) can be used to characterize the boundary of a different network. Moreover, the failures occurring on different network nodes can lead to different network structures. That is, the results in Fig. S8 can be considered as coming from different networks. These results also show that Eq. (1) is independent of the network. Eq. (1) is the analytical equation for the synchronous stability boundary. Therefore, these findings demonstrate that the synchronization stability boundary is independent of the network structure and parameters. This conclusion is at least applicable to those reconfigurable networks. Eq.(1) can be a good solution for multiple generators’ synchronization stability, the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators, and partial synchronization.

More information can be obtained from the expression of Eq. (1). Specifically, the left-hand side of Eq. (1) represents the global stability domain13 (i.e.,when ,|uL| = |uK|, ). |uL| = |uK| is a manifestation of the symmetry of the system. This finding shows that high symmetry can promote synchronization in complex networks. This can explain why symmetric networks have better synchronization capabilities. This has been reported in various studies31,32.

The right-hand side of Eq. (1) has a variant that is expressed by:

where is the stability margin of the Kth and Lth meta-generator angle difference of the rotation rate. . The difference between and can be used to measure the degree of asymmetry of the system. Clearly, when |uL|, |uK| are sufficiently close33, tends to 0. As |uL| - |uK| increases, increases. In other words, the synchronization stability domain becomes larger as the degree of asymmetry increases. This explains the recently discovered superior synchronization stability of highly asymmetric systems6,34. It is very difficult to maintain a high degree of symmetry at all times after the system is perturbed. For those systems requiring stability, asymmetry may be a more economical candidate. When , the Kth and Lth meta-generators are not synchronized.

Consequently, both high symmetry and high asymmetry promote synchronization. The expression of Eq. (1) is very simple, yet it harmonizes these two contradictory conclusions well and requires no additional assumptions.

In summary, Eq. (1) enables a unified analysis of the synchronization stability of the grid and provides a new understanding of synchronization. To determine the stability of a power system of n generators, only n pairs of variables ui, δi, i(1,2,..., n) are required. These variables are physically meaningful and can be readily obtained. This greatly simplifies the study of grid synchronization stability.

Synchronization of complex networks is one of the central concepts of complexity science. However, the expression for its stability boundary, the equation , is so simple. It may suggest that we need to further understand the concept of the “complexity”.

Spontaneous Synchronization

Synchronized systems may be destabilized when they are disturbed. Therefore, it is equally important to study the the transition behavior of a disturbed system from stable to unstable states. I have observed that when the system is disturbed and on the brink of destabilization, the trajectory of the operating point becomes intriguing. A surprisingly specific structure emerges from the collective behavior of these trajectories. The operating point of the ith meta-generator is denoted by .

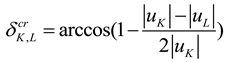

(a). Spontaneous synchronization of meta-generators. The horizontal axis represents the fault clearing time. The vertical axis represents the standard deviation of . The yellow area means the thin layer where spontaneous synchronization occurs. Here, denotes the standard deviation of , which begins to decrease at 0.147 s (magenta dots) and increases by 1300% at 0.155 s when the system becomes unstable (cyan pentagram dots). can be calculated using Eq. (S6).

(b). The phenomenon of potential barrier on plane . increased from 0.140 s to 0.154 s. The black arrow means the direction in which increased. From (the magenta dot) onward, the distance between neighboring points decreased in the direction of the black arrow (the elliptical shaded area).

(c). Starting points of spontaneous synchronization. The horizontal axis represents the fault clearing time. The amplified points mean the starting points of spontaneous synchronization. Near the boundary, all of starting points appear at . The disturbance trajectories of all of the points were almost identical. σi in panels (b) and (c) are calculated using Eq. (S3).

As shown in Fig. 2(a), exhibits discontinuity at 0.154 s and 0.155 s. In agreement with the findings presented in Fig. 1, the system is stable at and unstable at . The decrease in from the highest point in the yellow region indicated that on the brink of destabilization, the velocity of the subsystem was spontaneously directed toward the mean value. This counterintuitive phenomenon is consistent with the definition of spontaneous synchronization effect8,35. The spontaneous synchronization effect causes to decrease whether the operating point crosses the potential barrier in the inward or outward direction. Therefore, within the thin layer, the results of in different directions are not the same. This may form a hysteresis loop of in these directions.

Figure 2.

Spontaneous synchronization and unique structure. The fault clearing time increases from 0.140 s to 0.155 s. The arrow means the direction of increase in (the 18-node three-phase short circuit to the ground fault). .

Figure 2.

Spontaneous synchronization and unique structure. The fault clearing time increases from 0.140 s to 0.155 s. The arrow means the direction of increase in (the 18-node three-phase short circuit to the ground fault). .

Although spontaneous synchronization has been utilized to understand the synchronous operation of generators23, certain studies have cast doubt on the existence of spontaneous synchronization in power systems9. The reason for these doubts is that current research has not uncovered direct evidence of self-organizing synchronization in the power system, nor has it shown exactly where it occurs. Self-organizing behavior emerges from the interactions of these meta-generators, and its effects are reflected in the perturbation trajectories at the operating point. As shown in Fig. 2(b), for a constant step size , the interval between points decreases progressively within the shaded area, leading to the emergence of a unique trajectory structure. I refer to this novel structure as a “potential barrier” because the points within the shaded area exhibit "decelerating motion", as if the mass points were crossing a potential barrier. To the best of my knowledge, this structure has not been previously reported. σ(σi) reaches its maximum at and begins to decrease in Fig. 2(a). The magenta dot corresponds exactly to in Figs. 2(b). All of amplified points appear at the identical in Fig. 2(c). These amplified points are located at the transition of . Prior to this, . After this, . Moreover, the system is unstable at . These results demonstrate that is the starting point and is the end of spontaneous synchronization. This is the position of spontaneous synchronization where emergence occurs.

Currently, spontaneous synchronization is considered to be closely related to the network structure36. However, the results of this paper yield another conclusion. I want to emphasize that the “spontaneous synchronization” in this paper refers only to the position of spontaneous synchronization where emergence occurs. The experimental results show that the thin layer where spontaneous synchronization occurred is found only close to the synchronization stability boundary. Different failures led to different network structures. Similar to Fig. 2(a), those results in Fig. S5 from different network structures suggest that a decrease in σ(σi) occurs only when the system is on the brink of lose synchronization. In other words, the system suddenly self-organizes toward synchronous evolution only when it about to reach a critical synchronous stable state. Additionally, a comparison of Figs. 2(a) and S2(a) indicates that the same conclusion holds true for a completely different network. These phenomenon can be interpreted as spontaneous synchronization occurring only close to the synchronous stability boundary. Eq. (1) describes the stability boundary of the power system. Consequently, for coupled network systems, the link between spontaneous synchronization and the boundary suggests that the location where spontaneous synchronization occurs is constrained by Eq. (1). As mentioned above, Eq. (1) is independent of the network. This finding suggests that spontaneous synchronization is independent of the network. This conclusion challenges the traditional perception of spontaneous synchronization in networks.

Additionally, when PΔu = P∂u, collective synchronization emerges from individuals’ behavior. Specifically, at , of all meta-generators transforms simultaneously (refer to Fig. 2(c)). Given that these meta-generators are connected to different nodes, this result suggests that they exhibit long-range correlation at the point of impending destabilization. This correlation leads to a collective movement of all individuals as a whole.

Current research on synchronization phenomena focuses on the transition from disorder to synchronization. There are few references to “the emergence of spontaneous synchronization during the evolution of a fully synchronized system to disorder”. The paper shows that the system also undergoes self-organization before it loses synchronization stability. Synchronization emerges from disorder when an operating point crosses the boundary in the inward direction. In this case, spontaneous synchronization may have different initial values and conditions, and it is not clear where it is started, which is an important issue that is not discussed in this paper. Considering that changes before and that is a phase transition point, I infer that the boundary is the onset of synchronization in that case.

The behavior of the operating point near the boundary is diverse. For example, A comparison of Figs. 2 and S2 reveals that spontaneous synchronization can result in at least two different results. The reasons for this difference, or rather, the specific conditions for the formation of a potential barrier, require further research. Moreover, the thin layer where spontaneous synchronization occurs has some thickness. This thickness may be related to the network topology and parameters, but its solution is not clear. These issues will be addressed in future research.

Methods

Derivation of the boundary equation and visualized

There is a consensus in the literature: Synchronization occurs when the coupling dominates the dissimilarity2. Currently, the coupling is typically quantified by graph theory, and the dissimilarity is quantified by the frequencies .

(a). The generators are kept in synchronized operation. The magenta dot indicates the ith generator . The length of the solid cyan line represents the generator port bus voltage amplitude . The angle of the solid line is defined as the angle of rotation rate of the Kth meta-generator. Note that is not a phase. is the rotor speed per unit of the Kth meta-generator. Specifically, for the power system, when the generator operates synchronously, , and .

(b). Following a disturbance in the power system, , and . is defined as “the coupling potential difference” between the Kth and Lth meta-generators (the orange dotted line between the magenta square dots). Correspondingly, is constructed to describe “the dissimilar potential difference” between the Kth and Lth meta-generators (the solid blue line between the cyan dots).

In real operating power systems, the generator port bus voltages (per unit value) and are often unequal. That is, when all generators operate synchronously, the coupling strength between them is greater than 0 because of the difference between and (i.e., )[see Fig. 3(a)]. Unlike in the previous method, the coupling strength between the nodes is quantified by . is the coupling power. .

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram. Fig. 3 is an analogous illustration of the amplitude angle which is the foundation of power system analysis.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram. Fig. 3 is an analogous illustration of the amplitude angle which is the foundation of power system analysis.

On the other hand, the dissimilarity between the nodes is quantified by . is named the dissimilar power. corresponds to complete synchronization. When all the generators are completely synchronized(i.e., no dissimilarity), (i.e., ). Following a disturbance in the power system, the generators' rotational speeds are dissimilar, (i.e., ) [see Fig. 3(b)].

The expressions for and are analogous to those of , which can represent the interaction between the nodes in a power system. and have the same dimension and can be directly compared in size. is the impedance between the Kth and Lth meta-generators.

Considering the consensus mentioned earlier, the boundary equation is expressed as in the grid. When , the system is synchronous and stable. Conversely, when [to fulfill this condition, is chosen instead of in Eq. (S1)], the system is out of synchronization and unstable.

I emphasize that , not and , is independent of the network topology. It is clear from the form of and that they are related to the network, as information about the network is contained in . However, eliminates . It is observed that . The set of points for which is the synchronous stability boundary.

The symbols "∆" and "∂" are for distinction only and have no mathematical significance. Thus, Eq. (1) is obtained via derivation from . Clearly, the only variables in Eq. (1) are and .

is the stability boundary equation. When , the system is stable. When , the system is unstable. Geometrically, describes exactly curved surfaces that, together with , and encloses a stable domain.

In summary, the boundary equation can be found, where . The coordinate system is established, and the boundary is visualized (Fig. 1(a)).

Power grid datasets

Here, I describe the sources of data for the two power-grid networks considered in this study, namely the 3-generator (3-gen) test system and the New England (10-gen) test system37,38. The results of utilizing the New England test system are shown in Figs. 1, 2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, and S8, and the results of utilizing the 3-generator test system are shown in Figs. S1 and S2.

For each system, the data provide the generators’ dynamic parameters, the net injected real power at all generator nodes, the power demand at all nongenerator nodes, and the parameters of all power lines and transformers. These parameters are sufficient for standard power flow calculations and stability calculations6.

WECC 3-generator test system (3-gen). This system represents the Western System Coordinating Council (WSCC), which is part of the region now called the Western Electricity Coordinating Council (WECC) in the North American power grid. All the parameters mentioned above are from ref. 37.

New England test system (10-gen). The IEEE 39 bus system is well known as the 10-machine New England Power System. Generator 1 represents the aggregation of many generators. All the parameters mentioned above are from ref. 38.

The significance of using two entirely distinct test systems is much greater than that of merely adding a few numerical results. More crucially, this serves to demonstrate the applicability of the assumption of this paper to a completely different network.

Simulation software

Each of the two models was simulated separately using the Power System Analysis Software Package (PSASP), version 7.0, a simulation software. The PSASP is a large-scale power system analysis software package that implements a wide variety of computational functions. I utilized the software to perform standard power flow calculations on two test systems and to calculate the dynamic parameters of generators after a three-phase short-circuit ground fault, respectively.

The standard power flow calculation calculates the voltage, current and other physical quantities of the power system in steady-state operation. In the PSASP, the power flow calculation is the basis of the stability calculation. The mathematical model for stability calculation includes the mathematical description of the power grid and the dynamic characteristics of the equipment, as well as the simulation of various possible disturbance modes and stabilization measures. The techniques for power flow calculation and stability calculation are well established. For detailed knowledge on power flow calculations and stability calculations, see Refs. 11, 29 and 39. Notably, Eq. (1) is not the result of a power flow calculation or stability calculation.

Experimental steps and data processing

The selection of parameters should adhere to the following principles: 1) The coupling strength and the dissimilarity could be quantified and be constructed as an expression of the energy function by the selected parameters. 2) When the subsystems are coupled but not dissimilar, and . 3) The number of parameters should be sufficiently small to prevent dimensional catastrophe. 4) The selected parameters should have a clear physical meaning and are easily accessible. Consequently, the careful selection of suitable parameters is essential. For power systems, and are suitable parameters. In real systems, these parameters can be measured directly. I calculate the rotation rate and voltage of the generator using the aforementioned simulation software.

First, I modeled the networks of the test systems in the software package and input the data. I utilized the standard power flow calculation program to obtain data such as the port bus voltage of the generator. For steady state operation, the frequency base value is set at 50 Hz.

To observe the response of the disturbed operating point, I turned off the controls. Prior to performing stability calculations, I fixed the fault location (e.g., node 18 in the New England test system, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2) and specified the fault type and the fault clearing time . All fault types discussed in this paper were set as a three-phase short circuit to ground. I calculated the rotation rate and port bus voltage of the ith generator for various fault clearing times . To test the effectiveness of the approach for the stability of multiple swings, the time window was set to 20 seconds. That is, using the start of the disturbance as a starting point, I calculated and recorded the generator data for the next 20 seconds. The fault location and type remain unchanged, a new fault clearing time was set, and the above steps were repeated until the system loses synchronization stability (Figs. 1(e) and S1(d)). denotes the step length.

The angle of rotation rate of the ith generator was subsequently calculated as . The extensive interconnections between generators make stability analysis very challenging (see Fig. S3). This challenge arises from the complexity of the network. To address this issue, the concept of a meta-generator is introduced here. At moment t, the instantaneous values of the n generator system are arranged in descending order by , relabeled, and then reconstituted as the n meta-generator system .

In other words, when the condition

holds,

A meta-generator is created by reordering and labeling generators. This is a technical treatment only, and this transformation has been shown not to change the pattern of change in the state of the system [see Figs. S4(a), S6 and S7]. In this way, I obtain the meta-generator data . Before and after the transformation, the number of generators and meta-generators is equal.

The operating point of the ith meta-generator is represented by . The coupling point of the Kth and Lth meta-generators is represented by . This data can be utilized as coordinates for visualization, as shown in Fig. 1. These points are calculated as follows:

The means of

over

were

and

The results here are shown in Figs. 1(b), 2(b), S2(a), etc.

After disturbance, the location of the coupling point vary with time. The means of

over

were

where

is the time interval. The results here are shown in Figs. 1(c) and S2(b).

Near the boundary, was calculated at a relatively fine scale. The standard deviation of is calculated as follows:

where

is the expectation of

. The results here are shown in Figs. 2(a) and S2(a) and S5.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Koronovskii, A.A.; Moskalenko, O.I.; Hramov, A.E. synchronization in complex networks. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2012, 38, 924–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, F.; Chertkov, M.; Bullo, F. Synchronization in complex oscillator networks and smart grids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 2005–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Hao, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, P.; Shen, F. Online Reconstruction of Complex Networks From Streaming Data. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 5136–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linyuan, L.L.; Zhou, T. Link prediction in complex networks: A survey. Phys. A Stat. Mech. its Appl. 2011, 390, 1150–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Fang, J. Topology identification of the modified complex dynamical network with non-delayed and delayed coupling. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 68, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, F.; Nishikawa, T.; Motter, A.E. Asymmetry underlies stability in power grids. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.; Messina, A.R.; Vittal, V. Normal form analysis of complex system models: A structure-preserving approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2007, 22, 1908–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Hill, D.J. Synchronization of Kuramoto Oscillators: A Regional Stability Framework. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 2020, 65, 5070–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, M.R.; Bologna, S.; Bompard, E.F.; D’, G.; Agostino, N.A.; Ellens, W.; Pagani, G.A.; Scala, A.; Verma, T. Knowing power grids and understanding complexity science. Int. J. Crit. Infrastructures 2015, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrala, G.; Dimitrovski, A.; Pannala, S.; Simunovic, S.; Starke, M. Parareal in Time for Fast Power System Dynamic Simulations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrala, G.; Dinesha, D.L.; Dimitrovski, A.; Sreekanth, P.; Simunovic, S.; Starke, M. Large Multi-Machine Power System Simulations Using Multi-Stage Adomian Decomposition. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 3594–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Fang, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. Power System Transient Stability Assessment Based on Big Data and the Core Vector Machine. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 7, 2561–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qin, C.; Yang, T. Theory and Method of Power System Integrated Security Region Irrelevant to Operation States: An Introduction. Engineering 2020, 6, 754–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, F.; Wei, W.; Wang, Z. Approaching the Transient Stability Boundary of a Power System: Theory and Applications. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ammar, E.A.; El-Kady, M.A. Application of operating security regions in power systems. IEEE PES Transm. Distrib. Conf. Expo. Smart Solut. a Chang. World 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, P.; Paserba, J.; Ajjarapu, V.; Andersson, G.; Bose, A.; Canizares, C.; Hatziargyriou, N.; Hill, D.; Stankovic, A.; Taylor, C.; et al. Definition and classification of power system stability. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2004, 19, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student Member, B.B.; Senior Member, G.A. On the nature of unstable equilibrium points in power systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1993, 8, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.D.; Wu, F.F.; Varaiya, P.P. A BCU Method for Direct Analysis of Power System Transient Stability. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1994, 9, 1194–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubhanga, K.N.; Kulkarni, A.M. Application of Structure Preserving Energy Margin Sensitivity to Determime the Effectiveness of Shunt and Serles FACTS Devices. IEEE Power Eng. Rev. 2002, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhui, P.; Senroy, N. Real-Time Prediction and Control of Transient Stability Using Transient Energy Function. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Marhoon, H.H.; Leevongwat, I.; Rastgoufard, P. A fast search algorithm for Critical Clearing Time for power systems transient stability analysis. 2014 Clemson Univ. Power Syst. Conf. PSC 2014 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimorov, D.; Wang, X.; Kamwa, I.; Joos, G. An approach to constructing analytical energy function for synchronous generator models with subtransient dynamics. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 5958–5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motter, A.E.; Myers, S.A.; Anghel, M.; Nishikawa, T. Spontaneous synchrony in power-grid networks. Nat. Phys. 2013, 9, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wei, W.; Zheng, Z. Promoting synchrony of power grids by restructuring network topologies. Chaos An Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2023, 33, 63149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramoto, Y.; Battogtokh, D. Coexistence of Coherence and Incoherence in Nonlocally Coupled Phase Oscillators. Physics (College. Park. Md). 2002, 4, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, E.A.; Thutupalli, S.; Fourrière, A.; Hallatschek, O. Chimera states in mechanical oscillator networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 10563–10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaggio, M.J.; Abrams, D.M. Chimera states: Coexistence of coherence and incoherence in networks of coupled oscillators. Nonlinearity 2015, 28, R67–R87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Gonzalez-Longatt, F.M.; Wall, P.; Terzija, V. Two-step spectral clustering controlled islanding algorithm. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajala, O.; Dominguez-Garcia, A.; Sauer, P.; Liberzon, D. A Second-Order Synchronous Machine Model for Multi-swing Stability Analysis. 51st North Am. Power Symp. NAPS 2019 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto, L.F.C.; Bretas, N.G. Required damping to assure multiswing transient stability: the SMIB case. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2000, 22, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecora, L.M.; Sorrentino, F.; Hagerstrom, A.M.; Murphy, T.E.; Roy, R. Cluster synchronization and isolated desynchronization in complex networks with symmetries. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denker, M.; Timme, M.; Diesmann, M.; Wolf, F.; Geisel, T. Breaking Synchrony by Heterogeneity in Complex Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatekin, C.Z.; Uçak, C. Sensitivity analysis based on transmission line susceptances for congestion management. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2008, 78, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Motter, A.E. Symmetric States Requiring System Asymmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 114101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, F.; Bullo, F. Synchronization in complex networks of phase oscillators: A survey. Automatica 2014, 50, 1539–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Eigenvector-based analysis of cluster synchronization in general complex networks of coupled chaotic oscillators. Front. Phys. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.; Fouad, A.A. Power system control and stability; John Wiley & Sons, 2008; ISBN 8126518189.

- Pai, A. Energy function analysis for power system stability; Springer Science & Business Media, 1989; ISBN 0792390350.

- Niu, M; Wan, C; Xu, Z. A review on applications of heuristic optimization algorithms for optimal power flow in modern power systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2014, 2, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).