1. Introduction

Modern electrical grid development is driven by active research of various fields in the industry to satisfy the needs of modern society. Integration of renewable energy sources, differences in the supply chain, distributed management, active digitalization of monitoring, analysis, and management processes, as well as decentralization and scaling, leads to a wide range of problems, starting from performance to complex requirements for network objects in fault tolerance and resilience. One of the problems is the active synchronization of the states of a distributed network to maintain its structural and functional consistency. Such synchronization is crucial for critical infrastructure and is one of the necessary conditions for trouble-free functioning and stability. CRDT can ensure consistency in a deterministic and conflict-free manner. It is mainly used to provide fault-tolerant and robust systems. Therefore, we assume CRDT can potentially be used to maintain the overall resilience of the distributed electrical grid.

The main purpose of this study is to explore and evaluate the application of CRDTs in distributed electrical grid systems, particularly in high-load, real-time environments.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, related work is discussed, in

Section 3, a general representation of the distributed electrical grid’s state with formal definitions and consensus model representation for state coordination is described, in

Section 4, the experiment based on the actor-based framework for modelling of the distributed message delivery process using the CRDT-based state is outlined. In

Section 5-7, modelling results with farther discussion and conclusions are presented.

2. Literature Overview

In the latest decade, digital systems have radically transformed and adapted to the needs of modern society to meet the latest demands for speed, efficiency, security, fault tolerance and resilience. The massive shift from centralized computing architectures urges us that we should find a new way to address problems with applications which involve new approaches like the Internet of Things (IoT) where we can collect and preprocess data at the very end of the network.

Galesky et al. [

1] presented VCuve-Sync protocol where the state of the distributed application is maintained by CRDT, which allows operations to be performed simultaneously while ensuring a deterministic convergent final state. The results show that the solution demonstrates excellent performance in terms of message delivery latency and good efficiency in terms of bandwidth usage, especially in scenarios with multiple publishers and subscribers. Similar approach [

2] was proposed by Leonardo de Freitas Galesky and Luiz Antonio Rodrigues. Simić et al. [

3] proposed a concept of the distributed system where the machine state is represented by CRDT data, allowing operations like a real-time consensus with proper synchronization. Zhang et al. [

4] show how different protocols for state synchronization can be used in distributed systems. The characteristics of consistency are also analysed, and a blockchain system called CChain is proposed, which for the first time integrates the eventual consistency method (CRDT) into Fabric.

In a distributed system, strong consistency ensures that all clients observe consistent atomic updates of data across all servers. However, due to the influence of the CAP theorem, such systems must sacrifice availability during synchronization. Xin Zhao and Philipp Haller [

5] examined the model of observed atomic consistency (OAC), which ensures both fast convergent updates and non-convergent operations that require synchronization. The presented observable atomic consistency protocol (OACP) ensures OAC and can be implemented only if the communication subsystem ensures eventual delivery. This assumption is shared by CRDT.

Barreto et al. [

6] overview using CRDT for synchronization in rapidly changing distributed systems. The authors propose a PS-CRDT (publisher/subscriber) model to provide spatial and temporal decoupling of update dissemination. Such a solution ensures CRDT compatibility with the dynamic entry and exit of nodes in unstable environments. Lv et al. [

7] propose a new CRDT-based synchronization approach for real-time Co-CAD systems.

As we can see, there is a huge interest in using different CRDTs for the representation of the state of the distributed system for resolving disturbances and perturbations which can be caused by conflicts between system states. Numerous studies [

8,

9,

10,

11] show the efficiency, high performance, low latency and effective scalability of CRDT-based approaches in the context of message distribution, especially for large-scale systems with the Pub/Sub model. These results indicate that the solution is a promising option for ensuring strong eventual consistency [

12,

13] in distributed data systems. It can be very beneficial for systems which should be fault-tolerant and highly resilient.

3. General Representation of the Distributed Electrical Grid’s States Using CRDT

The overall state of the distributed electrical grid can be represented as a set of states of all its nodes, reflecting the current state of each one and their interactions [

14]. Among the aspects of the state, the following can be highlighted [

15,

16]:

Node availability: The state can indicate whether nodes in the network are available for data exchange. If a node fails or disconnects, this will affect the network’s state [

17];

Resource information: The state may include information about resources provided by the nodes;

Network load: The state can indicate the overall load on the network. If many nodes are actively exchanging data, this may lead to network congestion;

Connection stability: The state can reflect the stability of connections between nodes. If connections are unstable or nodes frequently lose connectivity, this can impact network performance.

The transmission of electricity to consumers can involve two types of events that should be distinguished [

18]:

Continuous phenomena, meaning deviations from nominal values that occur continuously. These phenomena mainly result from load characteristics, load power variations, or the nonlinear nature of the load;

Random voltage events, meaning sudden and significant deviations from the normal or desired voltage waveform. These are most likely due to unforeseen events (such as accidents) or external factors (such as weather conditions or actions by third parties).

Continuous phenomena include the frequency and variation of the supply current. For example, the nominal supply voltage frequency in Ukraine should be 50 Hz [

18]. Random voltage events include power supply interruptions and voltage sags. The cause of voltage sags is usually accidents occurring in public networks or consumer equipment. Overvoltages are generally caused by switching actions and load disconnections. Both phenomena are unpredictable and random, with their frequency varying significantly over the year depending on the type of power supply system and the observation point. Moreover, their distribution throughout the year can be highly uneven [

18].

It should be noted that the characteristics of the supply voltage—frequency, level, waveform, and symmetry of phase voltages—undergo changes during the normal operation of the system due to load power fluctuations, disturbances generated by certain types of equipment, and also during faults, which are mainly caused by external events. These characteristics change randomly over time at any chosen connection point, and furthermore, they can vary simultaneously at different connection points. As a result of these changes, in a reasonable number of cases, it can be expected that the characteristics will exceed the set values. Some phenomena affecting voltage, especially unpredictable ones, make it very difficult to establish appropriate values for their characteristics [

18].

In creating the distributed electrical grid model, the following principles were followed: the model should be used to describe the path of an object’s state change depending on its current state and additional information about the states of other objects, which is received externally.

The general state management model of an electrical system consists of a set of peer nodes, each representing an energy provider model with certain static and dynamic characteristics. The static characteristics include the node identifier and its geographical region. The dynamic characteristics include parameters such as nominal and actual power [

19,

20]. The combination of these characteristics forms the individual state of each node in the model.

To represent the state of a node it is necessary to identify characteristics that are unique, precise, and relatively infrequently changing, while also impacting management system decisions. Such characteristics include indicators of nominal and actual power.

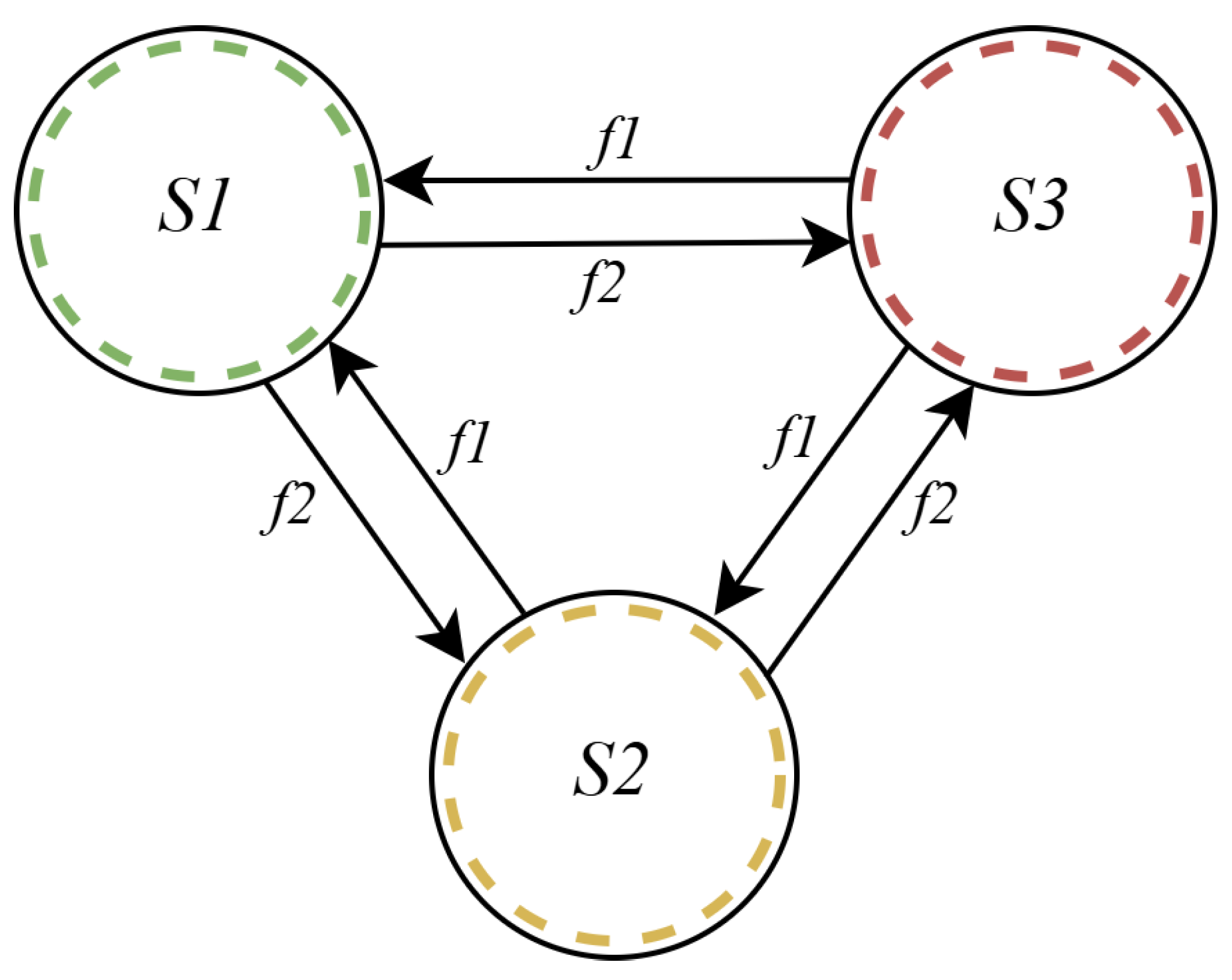

Since the model describes the state of the system, it would not be practical to store the actual values of these indicators within it, as this would lead to an infinite number of possible states that constantly change and would require replication. As minor fluctuations in indicators are acceptable, as noted above, and often do not result in a change in the overall state, an infinite set of states is unnecessary. Instead, we will represent it as a set of three possible states (

Figure 1).

Where S1 Green indicates that the supplier has excess capacity, S2 Yellow indicates that supply meets demand, S3 Red indicates that demand exceeds supply, and .

Data synchronization describes the concept of reconciling a set of data copies (states) or maintaining data integrity. The state reconciliation operation, or consensus, in distributed networks is a procedure for reaching common agreement on a distributed platform. It is essential for the nodes or entities involved in the distributed system to achieve consensus to ensure reliability and fault tolerance. Reliability and fault tolerance mean that, in a decentralized environment, there are several independent parties that can make their own decisions; some of these parties may act maliciously, yet the system must maintain a unified perspective despite their presence [

21].

In data exchange within networks where each node has its own copy of the data, ensuring consistency and state alignment is a critical issue. When a large number of nodes attempt to modify data simultaneously, conflicts arise that need to be resolved continuously and efficiently to avoid data discrepancies. Thus, the solution lies in developing methods and approaches that prevent conflicts and ensure data consistency in distributed networks [

22].

Conflict-free replicated data type (CRDT) [

23] is an abstract data type with a statically defined interface which allows distributed replication over multiple nodes. It allows optimistic replication [

24] in a principled way. Each replicate can be changed on demand and independently without any coordination overhead between them. When any two replicas have received the same set of updates, even if received in different orders, they reach the same state deterministically by adopting mathematically grounded rules to ensure state convergence [

25]. Moreover, if concurrent updates of a given data commute, and all its replicas execute all updates in causal order, then the values of the replicas converge. This is called a Commutative Replicated Data Type [

25]. It is designed to commute concurrent operations. This eliminates the need for complex concurrency control, allowing operations to be executed in different orders while having replicas converge to the same result. This approach guarantees no conflicts, thus removing the need for consensus-based concurrency control [

26,

27].

Using CRDTs to model the state of a distributed system has the following advantages:

The data structures are designed to be commutative and convergent [

28]. This means that multiple copies of the same data can be independently updated and then merged together without conflicts [

29]. This allows for efficient and accurate data analysis even in cases where the network is disconnected or has high traffic [

30,

31];

The CRDT approach relies on predetermined conflict resolution rules which dictate their semantics. These rules are typically data structure specific [

32]. CRDTs provide a mechanism for detecting and resolving conflicts, ensuring consistency across all copies of the data. This is particularly useful in the electrical grid, where multiple copies of state information can be stored in different locations;

By choosing a state-based CRDT structure [

28], which stores the current state of the data rather than the history of changes, they are suitable for real-time monitoring and analysis of data in the electrical grid;

Scalability: CRDTs enable the construction of distributed systems that can scale horizontally [

33] without the need for complex coordination mechanisms [

30];

Fault tolerance: CRDTs are fault-tolerant, as they allow data to be replicated between nodes and recovered in the event of a failure of one or more nodes [

34].

All the above advantages allow to build of highly resilient systems. CRDTs are divided into two types [

28]:

State-based CRDT: Convergent Replicated Data Type (CvRDT) - These CRDTs store a complete copy of the state on each network node, which is merged later. These CRDTs support state merge operations to avoid conflicts. A replica periodically propagates its local changes to other replicas through shipping its entire state. A received state is incorporated with the local state via a merge function that deterministically reconciles both states. To maintain convergence, merge is defined as a join: a least upper bound over a join-semilattice [

35]. A major drawback in state-based CRDTs is the communication overhead of shipping the entire state, which can get very large in size [

36];

Operation-based CRDT: Commutative Replicated Data Type (CmRDT) - These CRDTs store the operations that have been performed on each network node rather than a complete copy of the state. These CRDTs support the execution order of operations to ensure compatibility. The approach ensures that there are no conflicts, hence, no need for consensus-based concurrency control [

37]. CmRDTs have some advantages as they can allow for simpler implementations, concise replica state, and smaller messages; however, they are subject to some limitations: First, they assume a message dissemination layer that guarantees reliable exactly-once causal broadcast; these guarantees are hard to maintain since large logs must be retained to prevent duplication even if TCP is used [

38]. Second, membership management is a hard task in op-based systems especially once the number of nodes gets larger or due to churn problems, since all nodes must be coordinated by the middleware. Third, the op-based approach requires operations to be executed individually (even when batched) on all nodes [

36].

Based on these types, specific data types have been developed, such as counters, registers, sets, and graphs. Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs) can resolve conflicts if the data have certain mathematical properties, such as commutativity, associativity and idempotency. The problems created by CRDTs include a predefined structure that cannot be changed. Therefore, they cannot be used for all tasks, especially if the operations are not commutative [

3].

CRDTs raise important security concerns [

39]. A malicious replica could attempt to disrupt global convergence or consistency by interfering with other replicas; however, this risk can be managed using standard authentication methods [

40]. Another challenge, further accentuated with the decentralized and geodistributed nature of cloud-based deployments, is related to the privacy of the data stored within the CRDT. This cannot be done trivially using standard encryption techniques, as secure CRDT protocols would require replica-side computation – on encrypted data – to propagate operations. The outcomes in [28] introduce a foundational security model for CRDTs and provide specialized examples of secure CRDT constructions. Each construction must be carefully designed to use dedicated cryptographic techniques, so that the CRDT computations between replicas can be performed over encrypted data [

41].

In the current work, CvRDT with the possibility of spreading the delta of changes between nodes was used. Choosing a state-based CRDT [

28], which stores the current state of the data rather than the history of changes, it makes them suitable for real-time monitoring and analysis of data in the electrical grids.

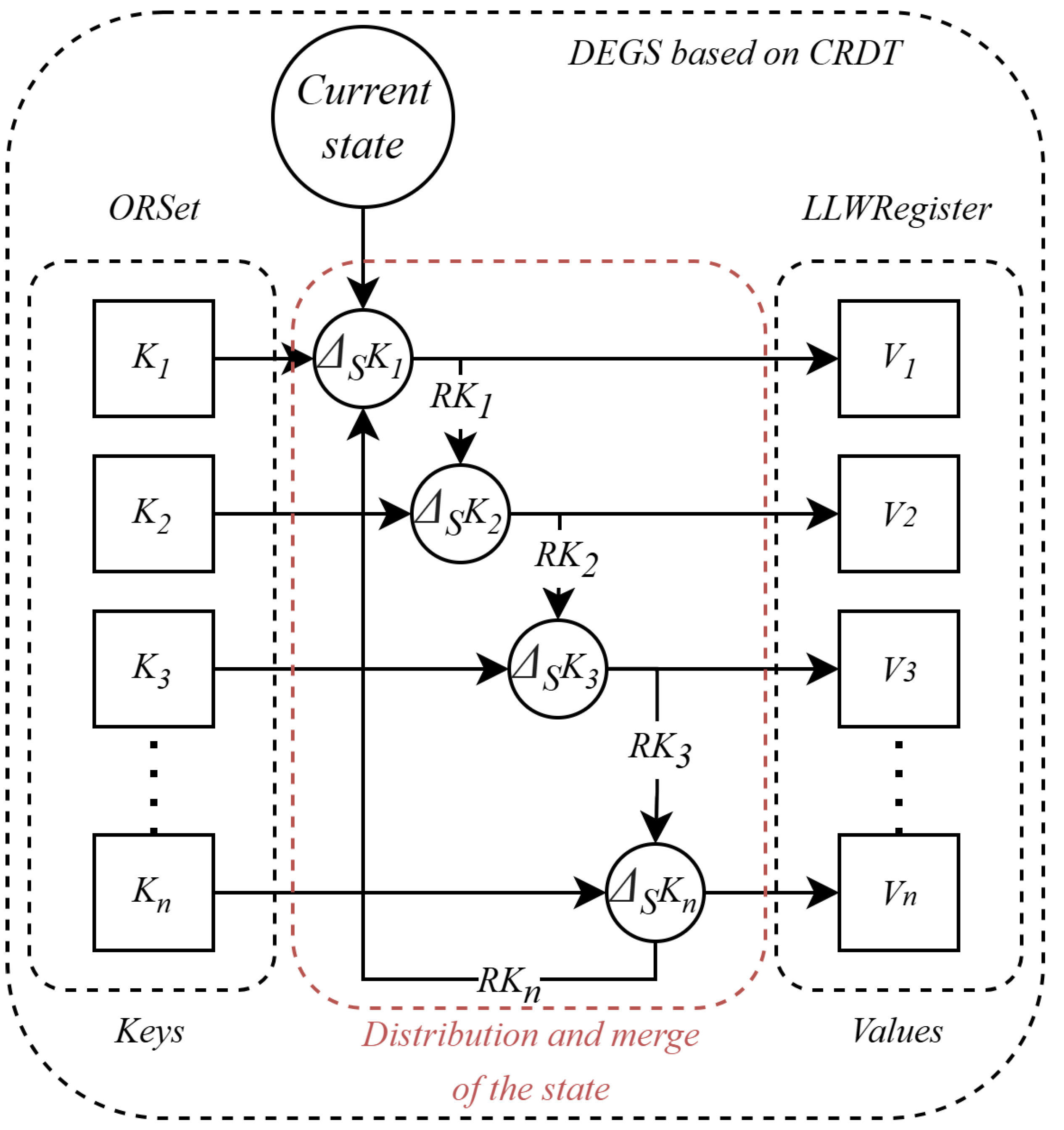

To describe the overall state of the system based on CRDT, which represents a Map data type that can be replicated across the entire set of nodes, according to [

42](p. 6) a modification of the Observed Remove Set (ORSet) [

28](p. 26) can be used. Since the container type Map is based on Set [

28](p. 21), the implementation of Map will have the same semantics as ORSet, except for the issue of concurrent updates to values, which must be merged in a specific manner. To address the mentioned issue, the CRDT data type LWW-Register [

28](p. 19) was chosen. Using this data type ensures that only the most recently written value is retained, while the previous value (if any) is discarded. Since we are interested in the most recent (current) state of a specific node in the overall system, this strategy is desirable.

Formally, LWW-Register can be defined as a set that is either empty or contains one value:

[

23](p. 4). It should also be noted that both ORSet and LWW-Register are Delta State Replicated Data Types [

36,

43], which reduces the need to send the full state during updates. In other words, when the state of an object changes, only the change itself will be sent, rather than the entire object with the new state. For example, adding elements

c and

d to the set {

} will result in sending the delta {

} and merging this state with the state on the receiving side, resulting in the set {

}. Therefore we can formulate a simple formula for state change as:

where

in a new state of

node,

is the previous state of

node,

is a change applied on the

node, ∘ is the merging changes operation.

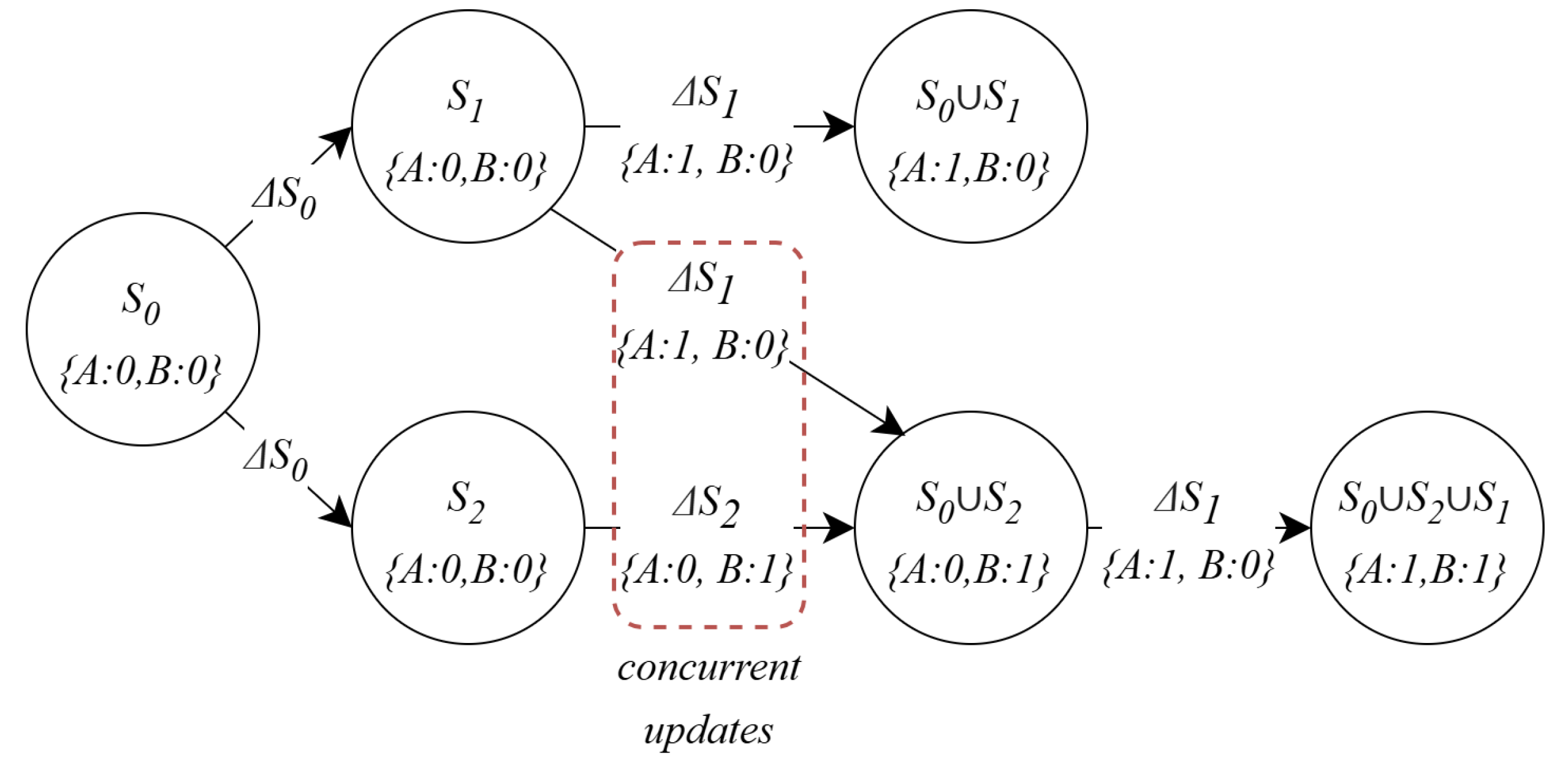

The overall state of the system will be represented by a Map data type based on ORSet, which has similar semantics for handling keys. However, in the case of concurrent updates to values (

Figure 2), any potential conflict will be resolved in favour of the most recently written value.

The general representation of DEGS based on CRDT can be written as:

where

denotes a

→

data structure with generic type

K for the key and defined node state

V for the value (

Figure 3).

To prove that a data type is a Convergent Replicated Data Type, it is necessary to show that it satisfies all three properties: idempotence, commutativity, and associativity.

-

Idempotence: Based on the structure of an Observed-Removed Set, the data type consists of a set of all added elements and a set of all removed elements. If an attempt is made to add the same element again, the ORSet remains unmodified because this element is already present in the set, ensuring no duplicate entries. This property confirms the idempotence of the

operation in the ORSet, as applying the same addition multiple times yields the same result without further changes. This approach avoids duplication and maintains the integrity of the data type, allowing the ORSet to behave consistently across distributed systems and support the CRDT properties of convergence and eventual consistency. Adding an element to the ORSet (

operation):

To prove idempotence, we need to show that adding an element to the set twice has no effect. This means that:

Since adding an element that is already present in the set does not alter the set, the operation is idempotent.

Similarly, attempting to delete an element that has already been removed will not modify the ORSet. Removing an Element from the Set (

operation):

To prove idempotence, we need to show that removing an already removed element from the set has no effect. This means that:

Since if an element has already been removed from the set, removing it again will not change the set, so the operation is idempotent.

Therefore, the and operations are idempotent;

-

Commutativity: Since the

and

operations do not depend on each other, the order in which they are executed does not affect the result. Let’s consider the initial state

S, where

,

V is the set of elements, and

R is the set of elements marked as deleted. Suppose we want to add a new element

x to the set

V and remove an element

y from the set

V. These operations can be written as:

Let’s assume that we first apply

, followed by

:

Now, let’s consider the order where we first apply

and then

:

It can be seen that = , since in both cases we added the element x to the set V and removed the element y from the set V. Thus, the operations can be performed in any order, which makes the data type commutative;

-

Associativity: To prove the property of associativity, we need to show that the result of the operations does not depend on the order in which they are applied, regardless of how these operations are grouped. Let’s consider 3 valid states

,

, and

, where:

Let’s now apply the operations

and

sequentially to each of the states and compare the results:

4. Modelling

For simulation, a special actor-based [

44] framework (Vigilant Hawk) was created. Its implementation based on Akka toolkit [

45] which allows building highly concurrent systems that are scalable, highly efficient, and resilient by using Reactive Principles [

46]. Using the actor model offers several advantages, particularly for building distributed, asynchronous, and high-load systems. The main benefits of using the actor model [

47,

48,

49]:

Natural Modeling of Asynchronous Processes: The actor model is ideal for asynchronous programming, where tasks run in parallel and independently. Actors communicate via messages without blocking, making it easy to create parallel processes without the need for thread synchronization;

Improved Scalability: The actor model allows for the addition of new actors or the distribution of actors across nodes with minimal code changes. This makes it possible to scale applications both vertically (on a single server) and horizontally (across multiple servers or nodes);

State Isolation: Each actor has its own state, which is not directly accessible to other actors. This eliminates the need for locks on shared state, reducing errors related to synchronization. Actors can update their state independently, making the system more robust;

High Resilience and Self-recovery: Actors have a built-in supervision system where one actor can monitor another. If an actor fails, its supervisor can restart it or take other corrective actions, ensuring automatic recovery. This is crucial in distributed systems that need to maintain continuous operation;

Simplification of Distributed Computing: Since actors communicate through messages, they can exist on different nodes of a distributed system. Actors can interact with each other both locally and over the network, simplifying the development of distributed systems where actors can exchange data regardless of physical location;

High Performance via Asynchronous Processing: Since actors don’t block threads when processing messages, the system can handle a large number of requests simultaneously. This allows high performance even under heavy loads, as there is no downtime due to resource locking;

Natural Management of Parallelism: In an actor system, each actor is an isolated unit of parallel computation. This makes it easy to distribute workloads across different CPU cores or even different machines without the complexity typically associated with multi-threading;

Ease of Developing Complex Systems: The actor model is well-suited for systems where objects have complex behaviour or interact frequently. Instead of creating complex locking and synchronization mechanisms, actors use messaging to manage behaviour, simplifying code creation and maintenance.

The framework was developed for the modelling of clustered high-load systems like distributed electrical grids systems concerning using different protocols for message delivery. Source files can be found here [

50]. Within this framework, clustered electrical grid systems were modelled using CRDT to represent the state of the cluster nodes. Each node of the cluster is represented as an independent actor with its internal state [

51] encapsulated and modified only through message passing. This ensures that the state of each node is isolated, reducing the complexity of handling shared mutable states across the system. The cluster’s nodes communicate asynchronously without blocking their execution [

52]. This allows nodes to remain responsive, even when waiting for external resources or handling other tasks, improving scalability and reducing latency. The actors are designed to be fault-isolated, if an actor fails, the system can recover by creating a new actor or reassigning tasks to other actors. Each node as an actor can process requests in parallel, allowing the system to handle a large number of operations concurrently. That approach allows to get advantages in terms of concurrency, scalability, and fault tolerance. When a node changes its state, it notifies the replicator of its new state, and these changes become available to all other nodes in the system. Since each node can see the overall state of the system, a node with excess capacity can temporarily redistribute it to meet the urgent needs of other nodes lacking power at a given moment. This redistribution considers priority, giving preference to the nearest nodes based on each node’s geographical region.

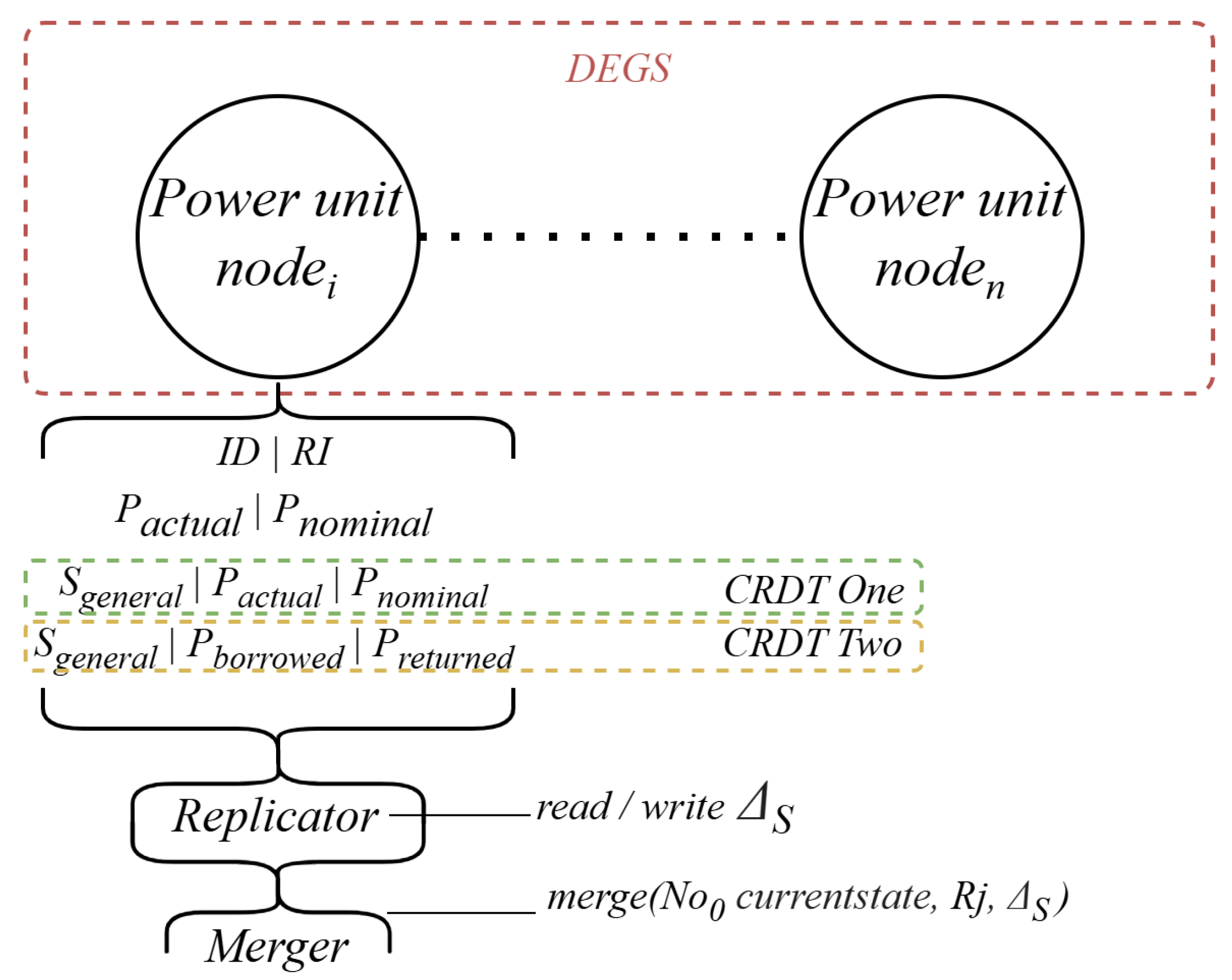

The simulated cluster consists of electrical unit nodes. Each node has its unique identifier (

), region identifier (

), its own nominal and actual power, two sets with identifiers of other units, and the values of borrowed and returned electricity from/to these units. The structural view of the node can be seen in

Figure 4.

In addition, each electrical unit has its own state (

) which reflects the relationship between nominal (

) and actual (

) power:

Each unit has its own view of the state of the grid as a whole where is the state of the node in some time t and points to the general state of the system with respect to a previous state of the i’s node in t-1, including states of other nodes. Each node is responsible for publishing changes to its state in this data structure and reading updates from other nodes whenever there are changes. In the experiment, we have 100 nodes that are in a green state. Through external influence, we increase the actual power in the observed node of the system so that it goes to the red state. We observe the state of the electrical grid as a whole (from the perspective of a random node in the system) over time while the system balances (nodes in a red state transition to a yellow state by borrowing power from neighbouring nodes, and nodes in a green state transition to a yellow state after borrowing this power). Therefore, we compose a view of a whole system based on a single node, which allows us to calculate messaging based on dynamic distancing.

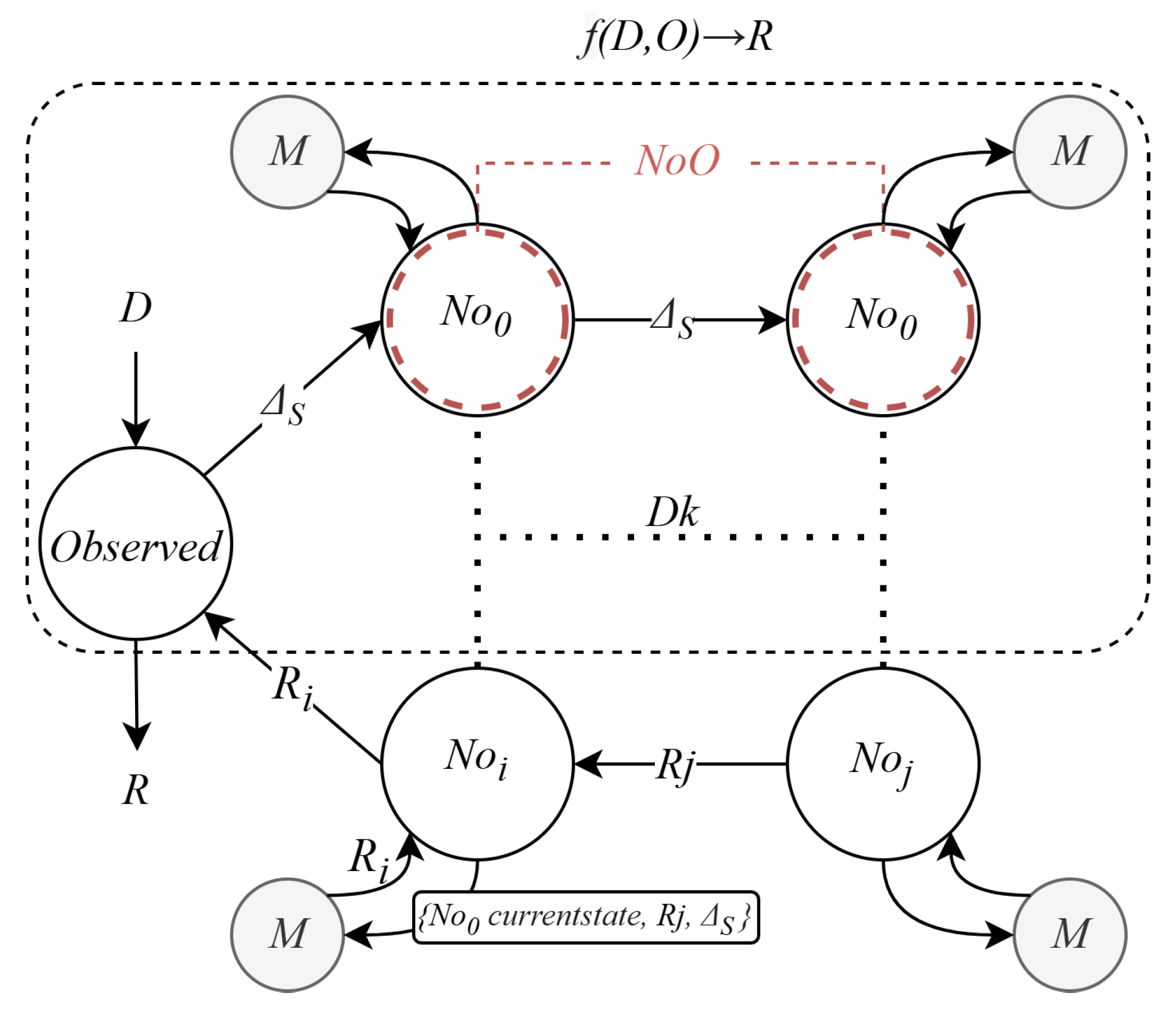

The experiment flow in terms of inner node communication is presented in

Figure 5, where Observed is the observable node,

D is the actual disturbance (in our case it is based on actual and nominal power of the node),

is the delta of the state to be shared with nearest nodes,

is the depth coefficient which shows the number of layers of nodes from the perspective of Observed node,

R is the resulting state,

is the process of CRDT message distribution from the Observed node to other nodes and vice versa,

is the nearest node which has established communication channel with Observed node,

means that

each transfer of

occurs in the same way as if each

will become Observer, then actual Observer becomes the corresponding

,

M is the merge function (incorporates merging strategy), which accepts

and (if it exists) corresponding

R for inner state changes and creation of intermediate result.

M can be interpreted using Equation

1. For example, the merge function for

can be written as

.

It should be noticed that each node incorporates a merge function between its actual state, and incoming result, therefore there may be collisions between and R, but based on the previous sections of the paper we can assume that any conflicts will be resolved during CRDT message distribution.

The actual experiment consists of several phases with different timestamps to simulate latency degradation, therefore the interval took from 9 seconds to 45 seconds. The following hardware configuration for simulation consists of Apple M3 Pro, 36 GB RAM, and 512 GB SSD disk. The specific set of experiments which includes latency degradation and message distribution density were concluded. To show how messages spread across the network the view from the perspective of undisturbed nodes in the system was used.

5. Modelling Results

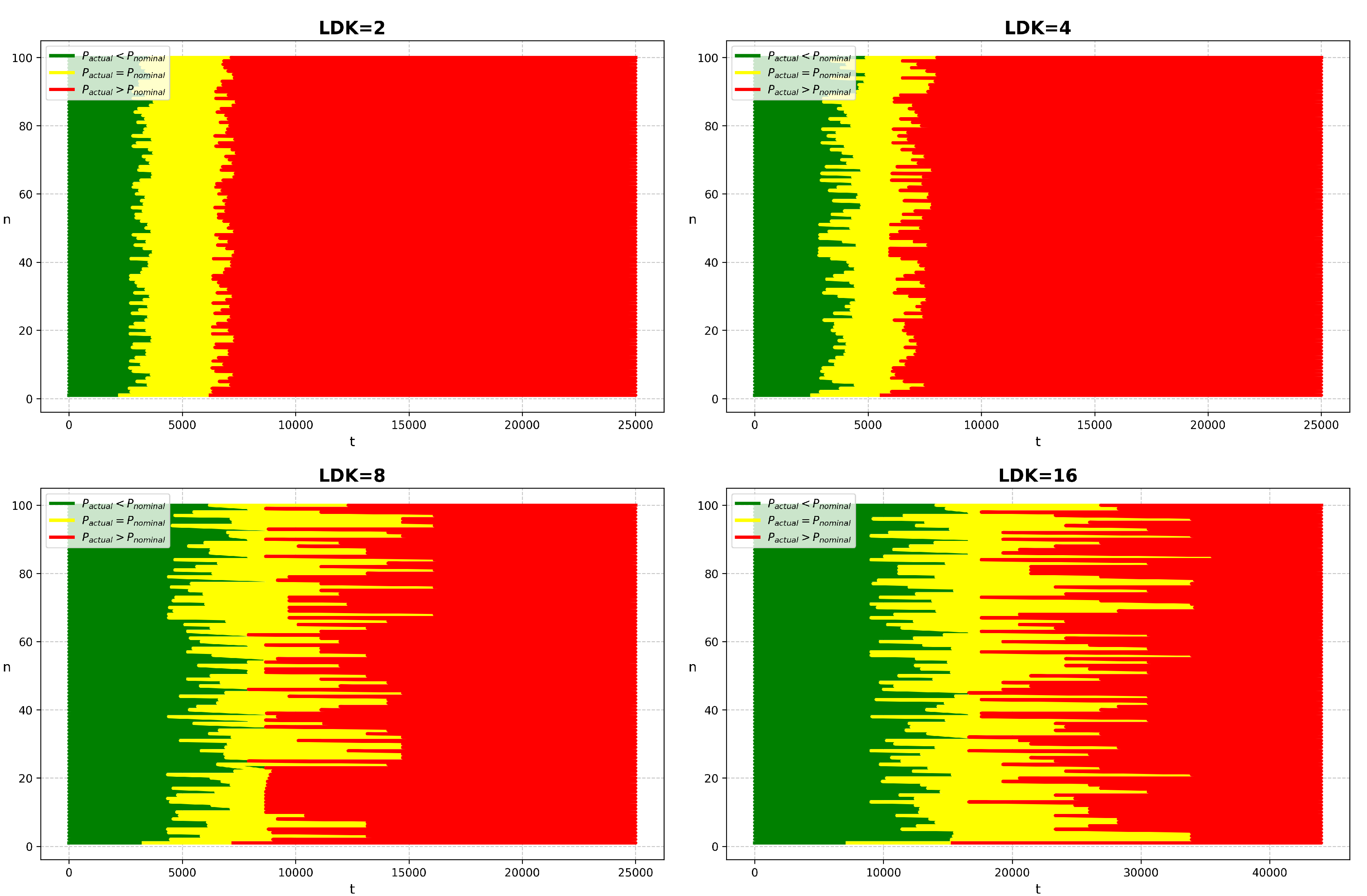

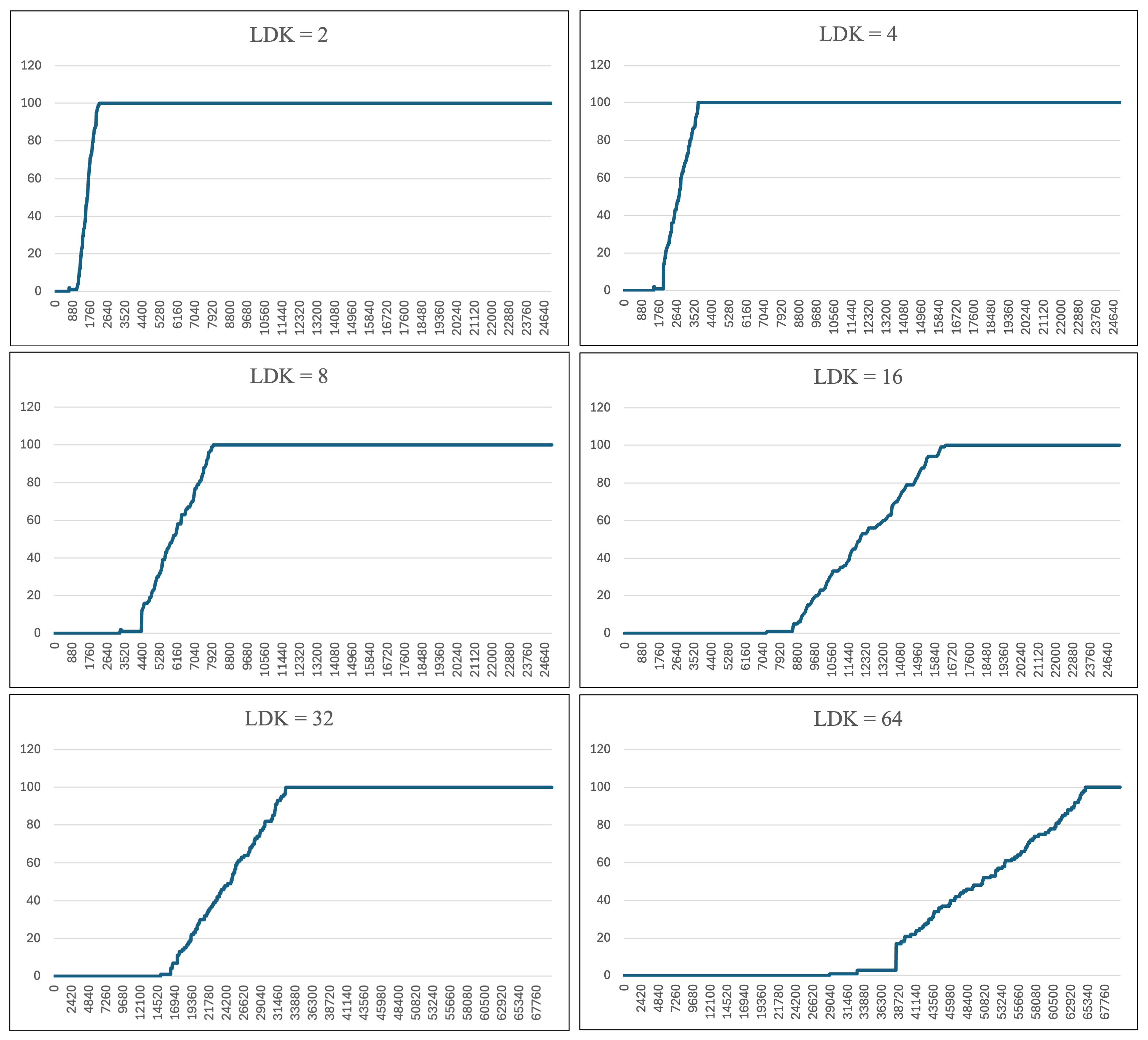

The actual simulation results can be seen in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 respectively, where the latency degradation coefficient (LDK) takes into account the different distance between nodes and FSDT is the full state distribution time which shows the time for which the state change spreads to 100% of other nodes.

General overview of the representation of the distributed electrical grid’s states using CRDT was made. Formal model with corresponding structure was reviewed. Special actor based framework for simulation of the distributed high-load electrical grids was developed and used for the deeper research of the actual advantages of CRDTs in terms of message delivering in the distributed systems.

It was found that increasing distancing between nodes with latency degradation can cause turbulences, making the system more complex to manage in various forms. We can also observe that there is an effective LDK value (in our case, ), at which the network does not experience significant disturbances. Therefore, to optimize , it is advisable to divide the cluster into smaller sub-clusters. Naturally, such a division would require a specific topology and a specialized inter-cluster communication protocol to maintain connectivity within larger network groupings. Additionally, it is worth noting that under , the system responded smoothly and predictably.

We observe that FSDT increases with LDK; however, the process of message distribution among other nodes remains stable and predictable. Essentially, there is a linear relationship between FSDT and LDK, allowing for the current solution to scale. It is also worth noting that an inflated average value of LDK was used in this experiment to demonstrate the performance of DEGS based on CRDT during a general network connectivity degradation.

6. Discussion

The application of Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs) to distributed electrical grid systems (DEGS) presents a novel approach to addressing the challenges of state synchronization in decentralized environments. Our study demonstrates that CRDTs can effectively maintain consistency and ensure deterministic behavior in DEGS, even under conditions of network latency and node disturbances.

One of the key findings from our simulations is the identification of an effective latency degradation coefficient (LDK), specifically , where the network maintains stability without significant disturbances. This suggests that DEGS can tolerate certain levels of latency without compromising state synchronization, which is critical for real-time monitoring and control. The linear relationship observed between the full state distribution time (FSDT) and LDK indicates that the system’s scalability is achievable without introducing non-linear complexities in message dissemination.

Our use of the actor-based framework, leveraging the Akka toolkit, has proven advantageous in modeling the asynchronous and concurrent nature of DEGS. The actor model’s inherent support for scalability, fault tolerance, and high concurrency aligns well with the requirements of modern electrical grids, which are increasingly distributed and subjected to high loads. By encapsulating each grid node as an independent actor with isolated state management, we have minimized the risks associated with shared mutable states and have enhanced the system’s resilience to node failures.

The experimental results affirm that CRDTs can facilitate efficient state synchronization in DEGS. The CRDTs’ properties of idempotence, commutativity, and associativity ensure that concurrent updates from multiple nodes converge to a consistent global state without the need for complex concurrency control mechanisms. This is particularly beneficial in scenarios where nodes may experience intermittent connectivity or when the network is subject to high traffic volumes.

However, the study also highlights certain limitations and areas for further exploration. The increase in FSDT with higher LDK values indicates that while the system remains stable, the time required for state changes to propagate throughout the network can become significant. This delay may not be acceptable in scenarios where rapid response times are critical, such as in the mitigation of sudden load imbalances or fault conditions. To address this, it may be necessary to implement strategies such as dividing the network into smaller sub-clusters to reduce propagation delays, albeit at the cost of increased complexity in inter-cluster communication and coordination.

Another consideration is the potential impact of network topology on message distribution efficiency. While our simulations assumed a certain degree of homogeneity in node connectivity, real-world electrical grids may exhibit more complex and heterogeneous network structures. Future work should investigate how different topologies influence CRDT-based synchronization and whether adaptive algorithms can optimize message routing based on real-time network conditions.

Security concerns associated with CRDTs, as noted in prior research [

39,

40,

53], are also pertinent to DEGS. Ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of state information is paramount, especially given the critical nature of electrical grid infrastructure. Incorporating robust authentication mechanisms and exploring secure CRDT protocols that can operate over encrypted data without compromising performance are essential areas for future development.

The simplification of node states to three discrete levels (green, yellow, red) provides a practical approach to modeling system behavior without the overhead of managing continuous state variables. However, this abstraction may overlook nuances in grid dynamics that could be important for finer-grained control and optimization. Incorporating additional state levels or adopting a hybrid approach that combines discrete and continuous state representations might offer improved fidelity without sacrificing the benefits of CRDTs.

In conclusion, the adoption of CRDTs for state synchronization in DEGS shows significant promise in enhancing system resilience and operational efficiency. The deterministic and conflict-free nature of CRDTs aligns well with the demands of distributed electrical grids, where timely and accurate state information is critical for maintaining balance and preventing failures. By addressing the identified limitations and extending the framework to accommodate more complex network conditions and security requirements, the proposed approach can contribute to the development of more robust and scalable DEGS architectures.

7. Conclusions

Overall, the system behaved predictably, and consistency was maintained after the disturbance. Despite the fact that the state synchronization time increased during significant disturbances, the nodes remained in a deterministic state, which prevented additional errors or network failures. This allows for efficient and accurate data analysis. The experimental results above demonstrated that the proposed solution is both scalable and fault-tolerant within the context of the effectiveness of the application of the CRDT for the synchronization of the distributed electric power grid system. Thanks to the state-based CRDT structure, the corresponding DEGS are well-suited for real-time monitoring and analysis of data in the electrical grids.

The next research steps can cover a wider range of different topics. Directions can include the development of special protocols for inner and outer electrical grid communication, including cybersecurity aspects of the replicated data types, since it is expected that larger clustered systems can be divided into separate ones. It will be very beneficial to develop a state management system based on the described data state, which will allow combining different approaches of stated data distribution, monitoring, threads and corresponding risks analysis, management and control of the whole system. The authors also consider it expedient to develop a universal approach to creating the topology of a distributed electrical grid system.

It will allow using CRDTs on different levels without any overhead based on the design of individual parts of the system. Independent clustered topologies will also provide a straight way for scalability and founded issues mentioned earlier. It can be a very tough problem, because each cluster can have its own architecture and non-functional requirements (NFRs). It is also crucial to now the behavior of message distribution in regards to the distance between nodes and state management issues.

Author Contributions

A.P.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, visualization. I.P.: Methodology, software, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation. M.Y.: Investigation, resources and editing, visualization. D.S.: Investigation, resources and editing. H.K.: Supervision, data curation, writing—review and editing. V.A.: Supervision, data curation, visualization, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Galesky, L.F.; Rodrigues, L.A.; Duarte, E.P. Jr. , Arantes, L. In Efficient Synchronization of CRDTs using VCube-PS. In Proceedings of the 12th Latin-American Symposium on Dependable and Secure Computing (LADC ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA; 50 -– 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galesky, L. F.; Rodrigues, L.A. Efficient CRDT Synchronization at Scale using a Causal Multicast over a Virtual Hypercube Overlay. In Proceedings of the 11th Latin-American Symposium on Dependable Computing (LADC ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA; 84 -– 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, M.; Stojkov, M.; Sladić, G.; Milosavljević, B. CRDTs as replication strategy in large-scale edge distributed system: An overview. In: Zdravković, M., Konjović, Z., Trajanović, M. (Eds.) ICIST 2020 Proceedings, pp.46-50, 2020.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. K.; Han, Y. J. CChain: a high throughput blockchain system, Proc. SPIE 12599, Second International Conference on Digital Society and Intelligent Systems (DSInS 2022), 125990K (3 April 2023); [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Haller, P.; Replicated data types that unify eventual consistency and observable atomic consistency, Journal of Logical and Algebraic Methods in Programming, Volume 114, 2020, 100561, ISSN 2352-2208. [CrossRef]

- Barreto, A.; Paulino, H.; Silva, J.A. ; Preguiça, N,; PS-CRDTs: CRDTs in highly volatile environments, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 141, 2023; ISSN 0167-739X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; He, F.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, Y. A novel CRDT-based synchronization method for real-time collaborative CAD systems, Advanced Engineering Informatics, Volume 38, 2018, 381–391, ISSN 1474-0346. [CrossRef]

- Acher, Q.; Ignat, C.; Ibrahim, S. Quantifying the Performance of Conflict-free Replicated Data Types in InterPlanetary File System. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Distributed Infrastructure for the Common Good (DICG ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA; 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Porto, D.; Clement, A.; Gehrke, J.; Preguiça, N.M.; Rodrigues, R. Making geo-replicated systems fast as possible, consistent when necessary; 10th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 12), USENIX Association (2012), pp. 265-278.

- Galesky, L.F.; Rodrigues, L.A.; Duarte, E.P. Jr.; Arantes, L. Efficient Synchronization of CRDTs using VCube-PS. In Proceedings of the 12th Latin-American Symposium on Dependable and Secure Computing (LADC ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA; 50-–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; He, F.; Lv, X.; Multi-core accelerated CRDT for large-scale and dynamic collaboration. J Supercomput 78, 10799–10828 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gomes, V.B.F.; Kleppmann, M.; Mulligan D., P.; Beresford A., R. “Verifying strong eventual consistency in distributed systems.” Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages (PACMPL), vol. 1, no. OOPSLA, Oct. 2017.

- Ahuja A., Gupta G., Sidhanta S., Edge Applications: Just Right Consistency, 2019 38th Symposium on Reliable Distributed Systems (SRDS), Lyon, France, 2019, ( 01-04 October 2019) pp. 351-3512. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Al-Darrab, A. M. A. Rushdi, Multi-State Reliability Evaluation of Local Area Networks, 2021 National Computing Colleges Conference (NCCC), Taif, Saudi Arabia, 2021, pp. 1-6 (27-28 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Weikert, D.; Steup, C.; Mostaghim, S. Availability-Aware Multiobjective Task Allocation Algorithm for Internet of Things Networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, (2022), 9(15):12945-12953. [CrossRef]

- Tariverdi, A.; Torresen, J. Rafting Towards Consensus: Formation Control of Distributed Dynamical Systems. arxiv 2023, arXiv:arXiv:2308.10097v1. [Google Scholar]

- Alahmad, Y.; Agarwal, A. Multiple objectives dynamic VM placement for application service availability in cloud networks. J Cloud Comp 13, 46 (2024). [CrossRef]

- State Standard of Ukraine (DSTU). Voltage characteristics of electricity supplied by public electricity networks (DSTU EN 50160:2014) Kyiv: Derzhspozhyvstandart Ukrainy, 2024. https://dnaop.com/html/61662/doc-%D0%94%D0%A1%D0%A2%D0%A3_EN_50160_2014.

- IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces IEEE 1547-2018. https://standards.ieee.org/ieee/1547/5915/.

- IEEE Standard for Relays and Relay Systems Associated with Electric Power Apparatus IEEE C37.90-2005. https://standards.ieee.org/ieee/C37.90/3284/.

- Masood, F.; Faridi, A. R. Consensus Algorithms In Distributed Ledger Technology For Open Environment. 2018 4th International Conference on Computing Communication and Automation (ICCCA), Greater Noida, India, 2018, pp. 1-6, (14-15 December 2018). [CrossRef]

- Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Maarten van Steen. Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2nd Edition.; CreateSpace; 2016.

- Preguiça, N. Conflict-free Replicated Data Types: An Overview. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.10254v1. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Y.; Shapiro, M. Optimistic replication. ACM Computing Surveys, 2005; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, P.S. Approaches to Conflict-free Replicated Data Types. arXiv, 2310. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, M.; Preguiça, N.; Baquero, C.; Zawirski, M. Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, S: Grenoble, France. [CrossRef]

- Letia, M.; Preguiça, N.; Shapiro, M. CRDTs: Consistency without Concurrency Control. Computing Research Repository (CoRR), 0907. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, M; Preguiça, N.; Baquero, C.; Zawirski, M. A comprehensive study of Convergent and Commutative Replicated Data Types. RR-7506, Inria – Centre Paris-Rocquencourt; INRIA. 2011, pp.50. https://hal.inria.fr/file/index/docid/555588/filename/techreport.

- Saquib, N.; Krintz, C.; Wolski, R. Log-Based CRDT for Edge Applications, 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering (IC2E), CA, USA, 2022, pp. 126-137. 30 September. [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, O.; Yu, W. Coordination-Free Replicated Datalog Streams with Application-Specific Availability. In: Tekli, J., Gamper, J., Chbeir, R., Manolopoulos, Y. (eds) Advances in Databases and Information Systems. ADBIS 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14918. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Kleppmann, M.; Mulligan, D. P.; Gomes, V. B.; Beresford, A. R. A Highly-Available Move Operation for Replicated Trees, IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquib, N.; Krintz, C.; Wolski, R. Log-Based CRDT for Edge Applications, 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering (IC2E), CA, USA, 2022, pp. 126–137. 30 September. [CrossRef]

- Biletskyy, B.O. Horizontal and vertical scalability of machine learning methods. Problems in Programming, 2019, 2, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazinska, M.; Balakrishnan, H.; Madden, S.R.; Stonebraker, M. Fault tolerance in the borealis distributed stream processing system. ACM Trans. Database Syst. 33(1), 1-–44 (2018). https://homes.cs.washington.edu/~magda/balazinska-tods08.pdf.

- Nation, J. B. Semilattices, Lattices and Complete Lattices. In Revised Notes on Lattice Theory, University of Hawaii https://math.hawaii.edu/~jb/books.

- Almeida, P.S.; Shoker, A.; Baquero, C. Delta State Replicated Data Types. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 111, 2018, 162–173. [CrossRef]

- Letia, M.; Preguiça, N.; Shapiro, M. CRDTs: Consistency without concurrency control. arXiv 2009 https://arxiv.org/pdf/0907.0929.pdf.

- Helland, P. Idempotence Is Not a Medical Condition: An essential property for reliable systems. Queue 2012, 10, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preguiça, N.; Baquero, C.; Shapiro, M. Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs). In Encyclopedia of Big Data Technologies. Springer, 2019.

- Jannes, K.; Lagaisse, B.; Joosen, W. Secure replication for client-centric data stores. In DICG 2022, 31–-36. ACM, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Portela, B.; Pacheco, H.; Jorge, P,; Pontes, R. General-Purpose Secure Conflict-free Replicated Data Types. 2023 IEEE 36th Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2023, 521–536. [CrossRef]

- An optimized conflict-free replicated set. https://hal.inria.fr/file/index/docid/738680/filename/RR-8083.

- Enes, V.; Almeida, P.S.; Baquero, C.; Leitão, J. Efficient Synchronization of State-Based CRDTs. In: ICDE (2019). https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.02750.

- Hewitt, C. Actor Model of Computation: Scalable Robust Information Systems. 2015 https://arxiv.org/abs/1008.1459.

- Akka toolkit. Available online: https://akka.io/ (accessed on 14 10 2024).

- The Reactive Manifesto. https://www.reactivemanifesto. (accessed on 14 10 2024)2024.

- Garnock-Jones, T. History of Actor, Lecture notes Harvard University, 2016 https://groups.seas.harvard.edu/courses/cs252/2016fa/12.pdf.

- Camilleri, C.; Vella, J.G.; Nezval, V. Horizontally Scalable Implementation of a Distributed DBMS Delivering Causal Consistency via the Actor Model. Electronics 2024, 13, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, G. A.; Mason, I. A.; Smith, S. F.; Talcott, C. L. A foundation for actor computation,Journal of Functional Programming, 1997 7(1), 1–-72. [CrossRef]

- Vigilant Hawk. Available online: https://github.com/ipk0/vigilant-hawk (accessed on 14 10 2024).

- To, Q.; Soto, J.; Markl, V. A Survey of State Management in Big Data Processing Systems. https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.01596.

- ACTORS: A Model of Concurrent Computation in Distributed Systems. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/6952 (accessed on 14 10 2024).

- Barbosa, M.; Ferreira, B.; Marques, J.; Portela, B.; Preguiça, N. Secure Conflict-free Replicated Data Types. ICDCN 21: Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Distributed Computing and Networking, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).