3.1. Stability Boundary

Synchronization occurs when the suppression dominates the dissimilarity. In power systems, the suppression is denoted as

and the dissimilarity is denoted as

. That is, when

, the system is synchronous and stable, otherwise it is out of synchronization. Therefore,

represents the synchronous stability boundary.

To facilitate the discussion of the validity of the synchronous boundary equation of power system, Equation (10) is restated here:

where

. (see Derivation of the boundary equation and Proof of the boundary equation)

Here,

is defined as the angle of rotation rate of the Kth meta-generator. It is important to note that

is not a phase and that

. Equation (10) actually defines the synchronous stability boundary for two meta-generators, hence

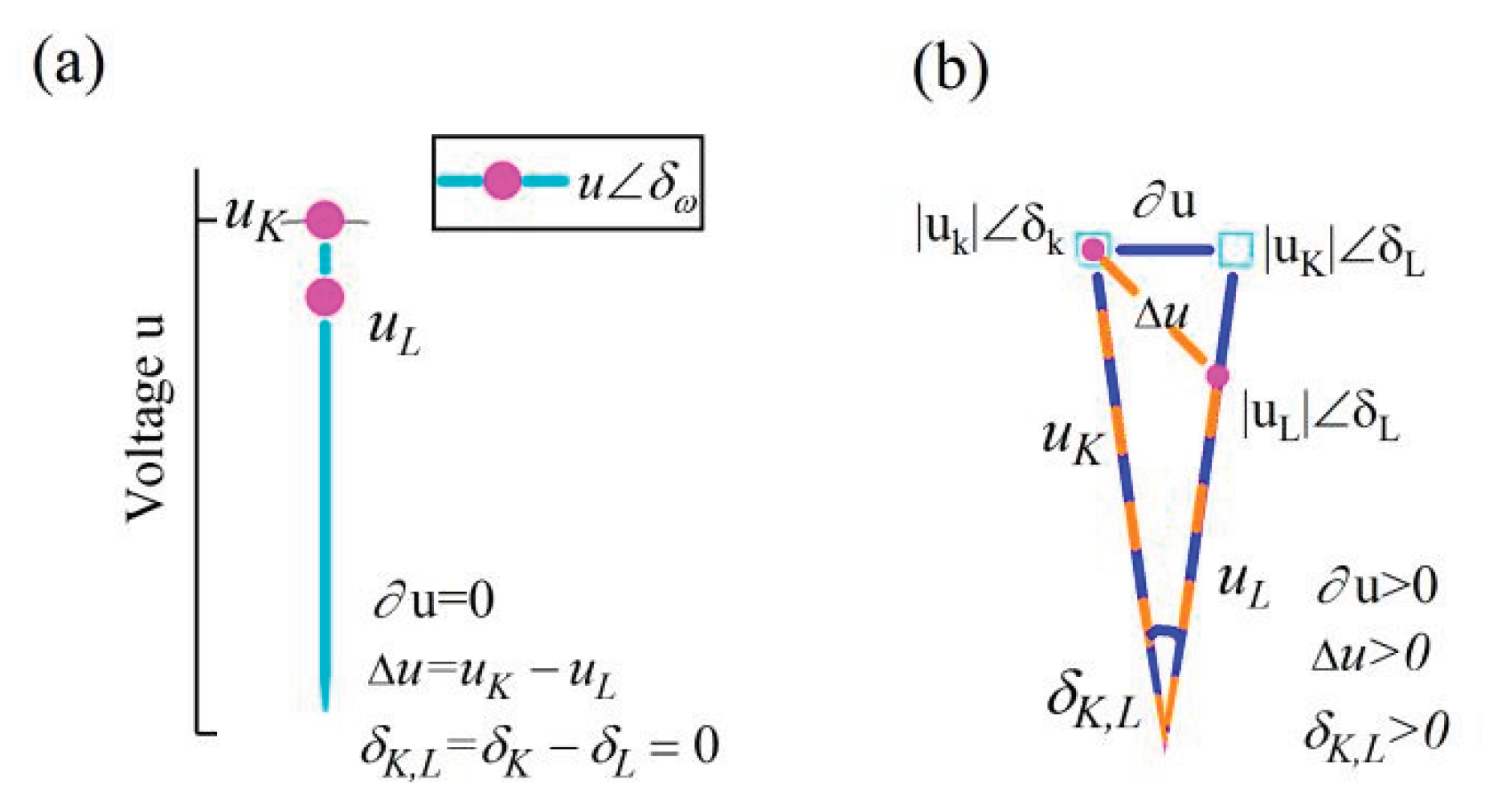

. For multi-generators systems, since all boundary equations share identical forms, the visualized graphs completely coincide, as shown in

Figure 2(a). The angle difference of rotation rate between the Kth and Lth meta-generators is

. According to the definition of synchronization,

.

denote the voltages of the Kth and Lth meta-generators, respectively. The meta-generators are “the map of the generators” (refer to Equation (2)). The voltage has been previously overlooked for simplicity [

22,

29] but is crucial for the synchronization stability of the grid.

is the frequency of the ith meta-generator, which is a normalization quantity commonly used in power system studies.

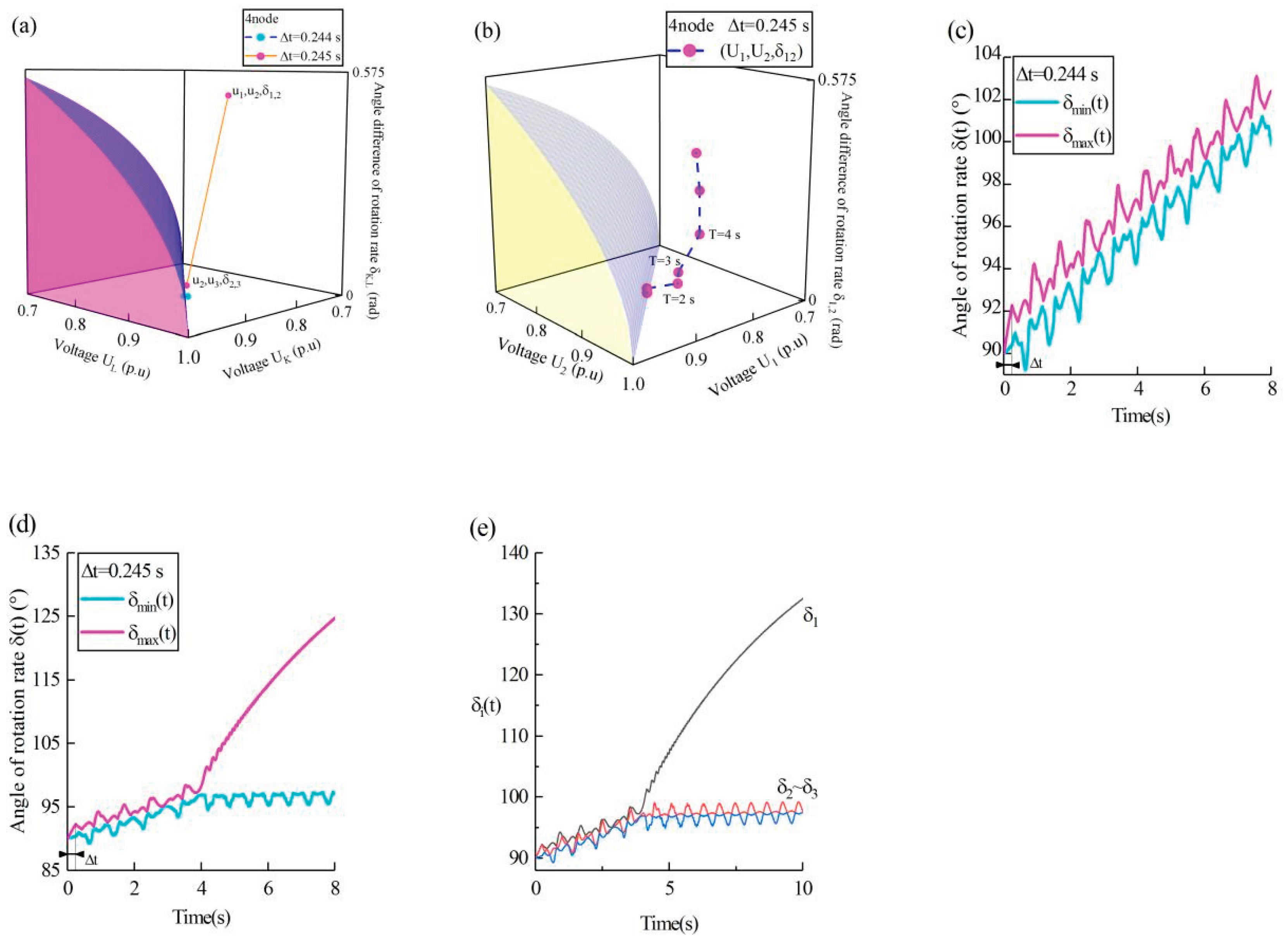

Figure 2.

Validity of stability boundary (Meta-generators in the 10-gen).

Figure 2.

Validity of stability boundary (Meta-generators in the 10-gen).

A New England test system was used. A three-phase short-circuit ground fault occurred at node 18. The data in

Figure 2 is derived from numerical simulations experiments.

is the fault clearing time.

denotes the step length commonly used in power system studies.

(a). Visualization of the stability boundary. The stability boundary in Equation (10) (blue surface and dark green plane) and the pink planes , and collectively define the boundaries and enclose the stability domain.

(b). Synchronization stability assessment and partial synchronization. is defined as the 3D coordinate point formed by the Kth and Lth meta-generators, and it is computed from and . are calculated using Equations (3) and (4). The cyan and magenta points represent the position of when and , respectively.

(c). The process of meta-generator desynchronization and the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators. The disturbed trajectory of is selected (). The calculation range is . Each cyan point represents the mean position of for a period of 1 second. The time T and the time interval are defined in Equation (5).

(d) and (e). Experimental verification of synchronous stability and the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators( and ). The horizontal axis represents the time. The vertical axis represents the value of . The maximum value of is represented by the magenta curve, and the minimum value is represented by the cyan curve. . At 11 second, in (d), and in (e). As illustrated in panel (d), the values of all meta-generators are close to each other and have approximately the same rate of change. panel (e) shows that in the time interval , increases sharply, indicating generator desynchronization.

(f). Experimental verification of partial synchronization. . The horizontal axis represents the time. The vertical axis represents the value of . After approximately 9 seconds, meta-generator 1 disengages from the cluster (cyan line). Subsequently, meta-generators 10 (magenta line) and 2 (orange dashed line) are separated. Meta-generators 3~9 form a synchronized cluster (green lines). are calculated using simulation software and Equation (2).

Three pieces of evidence demonstrate that Equation (10) effectively describes the synchronization stability boundary: 1) the boundary effectively distinguishes between stable and unstable states of the power system [see Figures 2(b) and 3(a)], 2) the stability of multiple swings [see Figures 2(c) and 3(b)], and 3) the partial synchronization phenomenon [see Figures 2(f) and 3(e)].

Figure 2(b) illustrates that the synchronization stability boundary effectively differentiates between synchronized and desynchronized states. A system comprising n meta-generators possesses n-1 3D coordinate points. The behavior of the cyan and magenta dots is significantly different, despite the slight difference in

(

Figure 2(b)). When

, all of the cyan dots are clustered at the boundary. When

, the three magenta dots, i.e.,

,

, and

, are outside the boundary and away from the rest of points. As mentioned above, when

,

is outside the boundary and the power system is out of synchronization. Consequently, it is concluded that the power system is stable at

and out of synchronization at

. The results in Figures 2(d) and (e) are in good agreement with this conclusion. Additional analogous results can be found in Figure S5.

Furthermore, utilizing

Figure 2(b) facilitates easily identify different synchronization patterns as it provides specific information about synchronized and desynchronized individual meta-generators or groups of meta-generators. The New England test system comprises 10 meta-generators, which is equivalent to 9 dots in

Figure 2. As shown in

Figure 2(b),

,

and

are outside the boundary while the rest of the points are clustered near the boundary. This signify that the meta-generators are divided into 4 synchronization groups. Specifically,

outside the boundary means that the meta-generators 1 and 2 are not synchronized. There are analogous conclusions for

and

. That is, the meta-generators numbered 1, 2 and 10 are out of synchronization while the other meta-generators remain synchronized. This indicates that the meta-generators in each group are also clearly shown in

Figure 2(b). The result for the meta-generator synchronization group shown in

Figure 2(f) is in good agreement with those presented in

Figure 2(b). This is the phenomenon of cluster synchronization [

30,

31]. Current research suggests that cluster synchronization occurs for a variety of reasons [

32,

33]. These results suggest that these causes can be described as the loss of synchronization stability between the oscillators corresponding to certain coordinate points and splitting into different synchronized clusters when these points lie outside the boundary. This interpretation will deepen our understanding of the complex phenomenon of partial synchronization. [More evidence can be found in Table S1 in Supplemental Material.]

Figure 2(c) shows the transition of the power system from stabilization to instability. As shown in

Figure 2(c),

crosses the boundary outwardly during the time interval

. Subsequently,

increases dramatically during the time interval

. These results are in good agreement with the simulation result presented in

Figure 2(e). This also suggests that the assumption of ignoring voltage [

8] variations may fail even for short-term simulations(of the order of one second or less). The simulation result demonstrates that the system loses synchronization during the aforementioned time interval. Therefore, the time at which the 3D coordinate point crosses the boundary is the onset of synchronization loss. These results pertain to the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators, an important issue that has not been resolved to date [

34,

35]. The above results demonstrate the synchronization stability boundary expressed by Eq.(10) can discriminate the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators in real time. Comparison of the results in Figures 2(b) and (c) reveals that the synchronous stability boundary is applicable to different time scales in power systems (long-term and short-term dynamics). More importantly, these results show that the synchronization stability boundary is the same in various cases (multi-machine, multi-swing scenarios, cluster synchronization situations, and different time scales). To power systems, this helps analyze the synchronous stability in a unified way.

The numerical experimental results in Figures 2(d), (e) and (f) are time-series data independently calculated by the simulation software. The results in Figures 2(b) and (c) are in good agreement with these experimental data. The above results provide solid evidences for the correctness and validity of the boundary equation from various perspectives.

As shown in

Figure 2(a), geometrically, Equation (10) represents two surfaces in a coordinate system

. The left-hand side of Equation (10) corresponds to a plane (dark green) perpendicular to the plane

, and the right-hand side corresponds to a curve surface (blue). These two surfaces are fixed, i.e., they are independent of network topology and parameters. Therefore, Equation (10) is independent of the network topology, system parameters, perturbations and number of subsystems. This finding, which contradicts previous reports [

2,

15,

20], indicates that the stability boundary of power system is independent of these factors. It is emphasized that

, not

and

, is independent of the network topology. The impact of the network is nullified through division (refer to “Derivation of the boundary equation”).

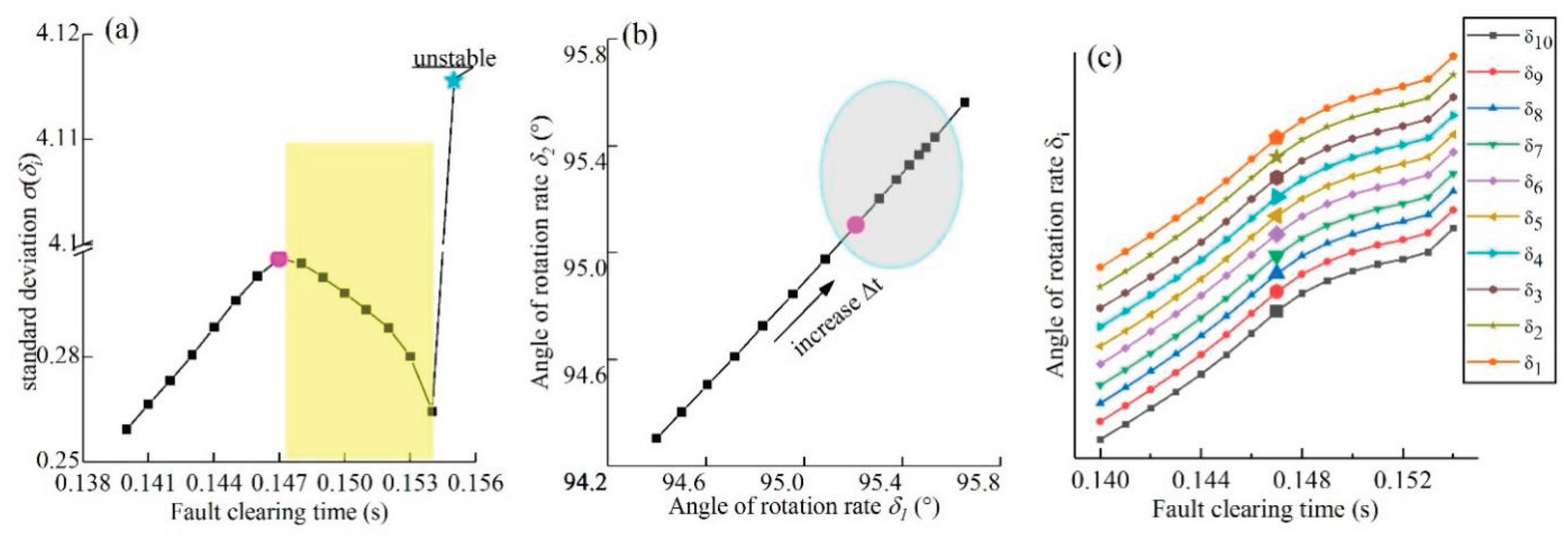

Figure 3.

Network-independent synchronous stability boundary. (Meta-generators in the 3-gen).

Figure 3.

Network-independent synchronous stability boundary. (Meta-generators in the 3-gen).

A three-phase short circuit to a ground fault occurred at the 4-node. The values of are calculated using simulation software and Equation (2). are calculated using Equations (3) and (4).

(a). Synchronization stabilization discrimination and partial synchronization. When , two cyan dots are clustered at the boundary. When , is outside the boundary and away from (magenta dots).

(b). The stability of multiple swings for multiple generators.

.

crosses the boundary outwardly in the time interval

and

rapidly increases in the time interval

. This is in good agreement with the result presented in

Figure 3(d).

.

(c) and (d) show experimental verification of synchronous stability and the stability of multiple swings for multiple generators. The horizontal axis represents the time. The vertical axis represents the value of . The maximum value of is represented by the magenta curve and the minimum value is represented by the cyan curve. At 8 s, in (c), and in (d). Meta-generators are synchronized at and out-of-sync at .

(e).The phenomenon of partial synchronization. (). The horizontal axis represents the time. The vertical axis represents the value of . In the early stages, all meta-generators are synchronized. After approximately 4 s, meta-generator 1 disengages from the cluster (black line). Meta-generators 2 ~ 3 form a synchronized cluster (red line and blue line). Three meta-generators break up into two coherent groups.

The straightforward method to prove that “the boundary is independent of the network” is to test whether Equation (10) holds true for a completely different network. Analogous results were obtained for the 3-generator test system using the same procedure (see

Figure 3).

Figure 2 shows the results of the simulation with the New England test system, whereas the results in

Figure 3 are from the 3-generator test system. The New England test system and 3-gen are two completely different network systems [

26,

27]. They clearly have completely different topology and parameters, but in both cases, the same boundary equation is applied. This is because the aforementioned evidence can be reproduced in the 3-generator test system. Both

Figure 3(a) and

Figure 2(b) correspond to evidence 1) mentioned above. Both

Figure 3(b) and

Figure 2(c) correspond to evidence 2). Both

Figure 3(e) and

Figure 2(f) correspond to evidence 3). Consequently, a comparison of

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 reveals that Equation (10) can be used to characterize the boundary of a different network. Moreover, the failures occurring on different network nodes can lead to different results. The results in Figure S5 and Table S1 correspond to different failures. These findings demonstrate that the synchronization stability boundary is is not only independent of the network topology, it is also independent of system parameters and fault locations. All of the above evidence suggests that in complex systems, synchronization conditions can be defined by the behavior of individuals, regardless of whether or not there is a clear network of interactions between those individuals.

More information can be obtained from the expression of Equation (10). Specifically, the left-hand side of Equation (10) represents the global stability domain [

20] (i.e.,when

,

).

is a manifestation of the symmetry of the system. This finding shows that high symmetry can promote synchronization in complex networks. This can explain why symmetric networks have better synchronization capabilities. This has been reported in various studies [

36,

37].

The right-hand side of Equation (10) has a variant that is expressed by:

where

is the stability margin of the Kth and Lth meta-generator angle difference of the rotation rate. That is, for

, the system remains synchronously stable when

. The difference between

and

can be used to measure the degree of asymmetry of the system. When

are sufficiently close [

38],

tends to 0. As

increases,

increases. In other words, the synchronization stability domain becomes larger as the degree of asymmetry increases. This explains the recently discovered superior synchronization stability of highly asymmetric systems [

25,

39]. It is very difficult to maintain a high degree of symmetry at all times after the system is perturbed. For those systems requiring stability, asymmetry may be a more economical candidate. In addition, Equation (17) shows the potential for stability control: we may be able to increase the synchronization stability margin by carefully controlling the voltage. When

, the Kth and Lth meta-generators are not synchronized. The synchronization stability domain is finite.

Consequently, both high symmetry and high asymmetry promote synchronization. The expression of Equation (10) is very simple, yet it harmonizes these two contradictory conclusions well and requires no additional assumptions.

In summary, Equation (10) enables a unified analysis of the synchronization stability of the grid and provides a new understanding of synchronization. To determine the stability of n oscillators, only n pairs of variables

are required. These variables can be readily obtained. Compared to the current literature [

40,

41,

42], the conclusions of this paper may indicate that we need to revisit the relationship between synchronization phenomena and networks.

3.2. Spontaneous Synchronization in Power System

Power systems may be destabilized when they are disturbed [

43]. Therefore, it is equally important to study the the transition behavior of a disturbed system from stable to unstable states. Observation shows that when the system is disturbed and on the brink of destabilization, the trajectory of

becomes intriguing. A surprisingly specific structure emerges from the collective behavior of these trajectories. The polar coordinates of the ith meta-generator are denoted by

.

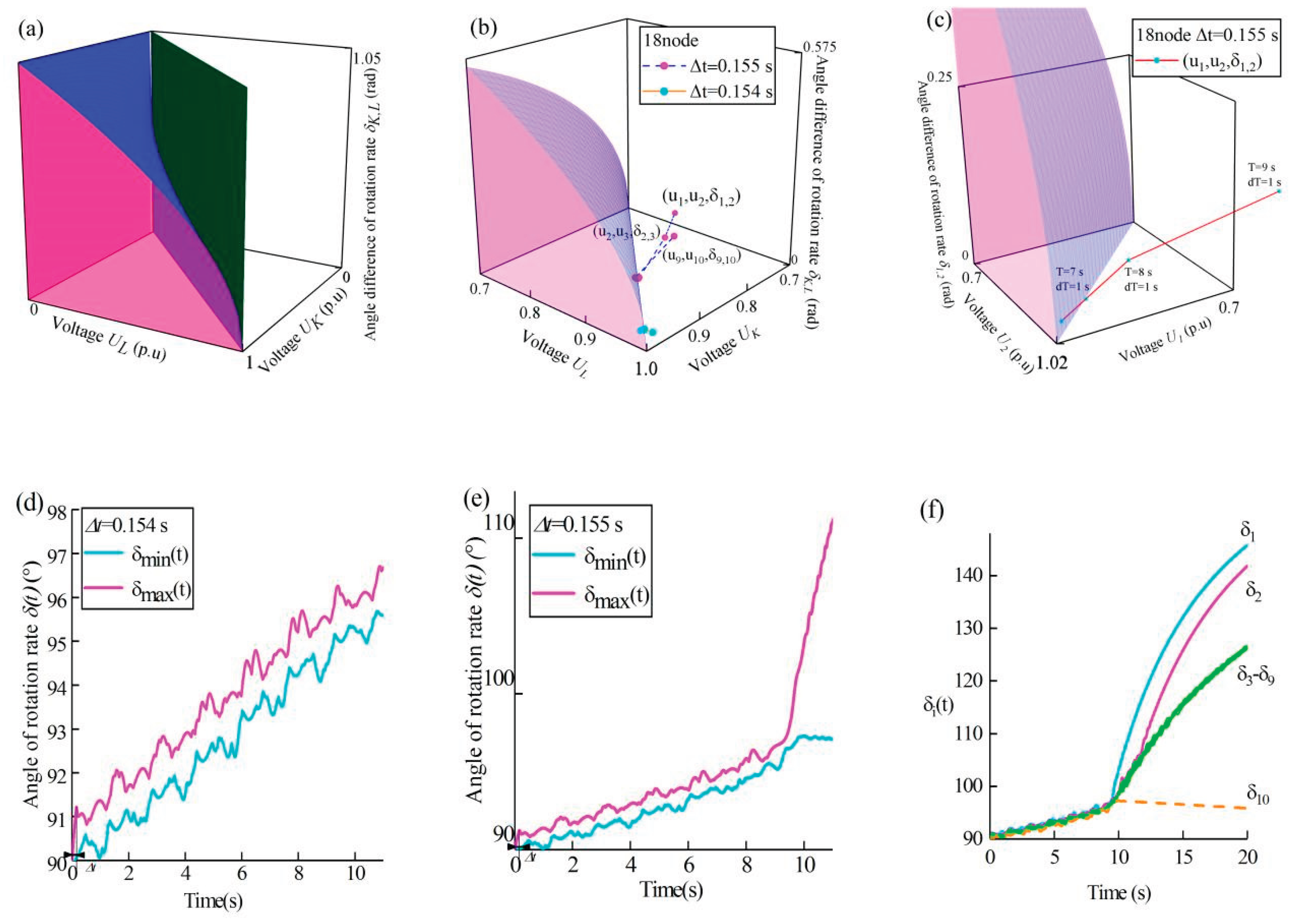

Figure 4.

Spontaneous synchronization positions and unique structure. (Meta-generators in the 10-gen).

Figure 4.

Spontaneous synchronization positions and unique structure. (Meta-generators in the 10-gen).

The fault clearing time increases from 0.140 s to 0.155 s. The arrow means the direction of increase in (the 18-node three-phase short circuit to the ground fault). . The data of are derived from numerical simulations experiments and are calculated using Equation (3).

(a). Spontaneous synchronization of meta-generators. The horizontal axis represents the fault clearing time. The vertical axis represents the standard deviation of . The yellow area means the thin layer where spontaneous synchronization occurs. Here, denotes the standard deviation of , which begins to decrease at 0.147 s (magenta dots) and increases by 1300% at 0.155 s when the system becomes unstable (cyan pentagram dots). can be calculated using Equation (6).

(b). The phenomenon of potential barrier on plane . increased from 0.140 s to 0.154 s. The black arrow means the direction in which increased. From (the magenta dot) onward, the distance between neighboring points decreased in the direction of the black arrow (the elliptical shaded area).[For the sake of image clarity, the point corresponding to is difficult to display in the figure; its data can be found in doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.24825.]

(c). Starting points of spontaneous synchronization and long-range correlation. The horizontal axis represents the fault clearing time. The amplified points mean the starting points of spontaneous synchronization. Near the boundary, all of starting points appear at . The trends of all of were almost identical. Combining (b) and (c) reveals that in this case, unique structures exist between any two meta-generators.[Since the values of corresponding to the same are nearly identical, the scale values on the vertical axis had to be omitted to illustrate the trend and facilitate visualization. This data can be found in doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.24825, as shown in “Data availability”.]

As shown in

Figure 4(a),

exhibits discontinuity at 0.154 s and 0.155 s. In agreement with the findings presented in

Figure 2, the system is stable at

and unstable at

. The decrease in

from the highest point in the yellow region indicated that on the brink of destabilization, the velocity of the subsystem was spontaneously directed toward the mean value. This counterintuitive phenomenon is consistent with the definition of spontaneous synchronization effect [

13,

44]. It can be inferred that the spontaneous synchronization effect causes

to decrease whether the system crosses the yellow area(in

Figure 4(a)) in the inward or outward direction. Therefore, within the thin layer, the results of

in different directions are not the same. Moreover, Referring to Figure S3(b), the fault clearing time at

within the thin layer aligns with the fault clearing time corresponding to the yellow-shaded region in

Figure 4(a). This indicates that the system undergoes self-organization before losing synchronous stability, and this phenomenon occurs at the boundary of synchronous stability. For power systems, the spontaneous synchronization that occurs prior to destabilization provides additional protection for the synchronous stability of the system.

As shown in

Figure 4(b), for a constant step size

, the interval between points decreases progressively within the shaded area, leading to the emergence of a unique trajectory structure. This novel structure, termed a “potential barrier”, exhibits “decelerating motion” within the shaded area, as if the mass points were crossing a potential barrier. To the best of my knowledge, this structure has not been previously reported.

reaches its maximum at

and begins to decrease in

Figure 4(a). The magenta dot corresponds exactly to

in

Figure 2(b).

All of amplified points appear at the identical

in

Figure 4(c). These amplified points are located at the transition of

. Specifically, at

,

of all meta-generators transforms simultaneously. Prior to this,

. After this,

. Moreover, the system is unstable at

. These results demonstrate that

is the starting point and

is the end of spontaneous synchronization. This is the position of spontaneous synchronization where emergence occurs. Self-organizing behavior emerges from the interactions of these meta-generators, and its effects are reflected in the behavior of the oscillators. Given that these meta-generators are connected to different nodes, this result suggests that they exhibit long-range correlation at the point of impending destabilization. This correlation leads to a collective movement of all individuals as a whole.

In contrast to the previous literature discussing synchronization in power grids [

11,

22], this work reports a new phenomenon of spontaneous synchronization. These phenomena may originate from different mechanisms, since they occur in forward processes subject to perturbations, exhibit a special structure. Simultaneously, the thin layer where spontaneous synchronization occurred is found close to the synchronization stability boundary. That is, oscillators in the same network may have two different spontaneous synchronization behaviors at the same time.

Currently, spontaneous synchronization is considered to be closely related to the network structure [

45]. However, the results of this section yield another conclusion. Similar to

Figure 4(a), those results in Figure S4 from different fault responses suggest that the system suddenly self-organizes toward synchronous evolution only when it about to reach the edge of synchronous stable. These phenomenon can be interpreted as spontaneous synchronization occurring only close to the synchronous stability boundary. Consequently, for coupled network systems, the link between spontaneous synchronization and the boundary suggests that the location where spontaneous synchronization occurs is constrained by Equation (10). This finding suggests that spontaneous synchronization is independent of the network. As shown in Figure S1, results from entirely different network (the 3-generator test system) further corroborate this conclusion. This conclusion challenges the traditional perception of spontaneous synchronization in networks.

More importantly, these unexpected results show that we still lack research on the destabilization process of complex systems and the interaction and behavior of oscillators at the stability boundary. The behavior of the systems near the boundary is diverse. For example, A comparison of Figures 4 and S1 reveals that spontaneous synchronization can result in at least two different results. The reasons for this difference, or rather, the specific conditions for the formation of a potential barrier, require further research. Moreover, the thin layer where spontaneous synchronization occurs has some thickness. However, the solution for this thickness is not clear. These issues will be addressed in future research.

and the dissimilarity is denoted as

and the dissimilarity is denoted as  . That is, when

. That is, when  , the system is synchronous and stable, otherwise it is out of synchronization. Therefore,

, the system is synchronous and stable, otherwise it is out of synchronization. Therefore,  represents the synchronous stability boundary.

represents the synchronous stability boundary.

and

and  , is independent of the network topology. The impact of the network is nullified through division (refer to “Derivation of the boundary equation”).

, is independent of the network topology. The impact of the network is nullified through division (refer to “Derivation of the boundary equation”).