Submitted:

26 October 2023

Posted:

27 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

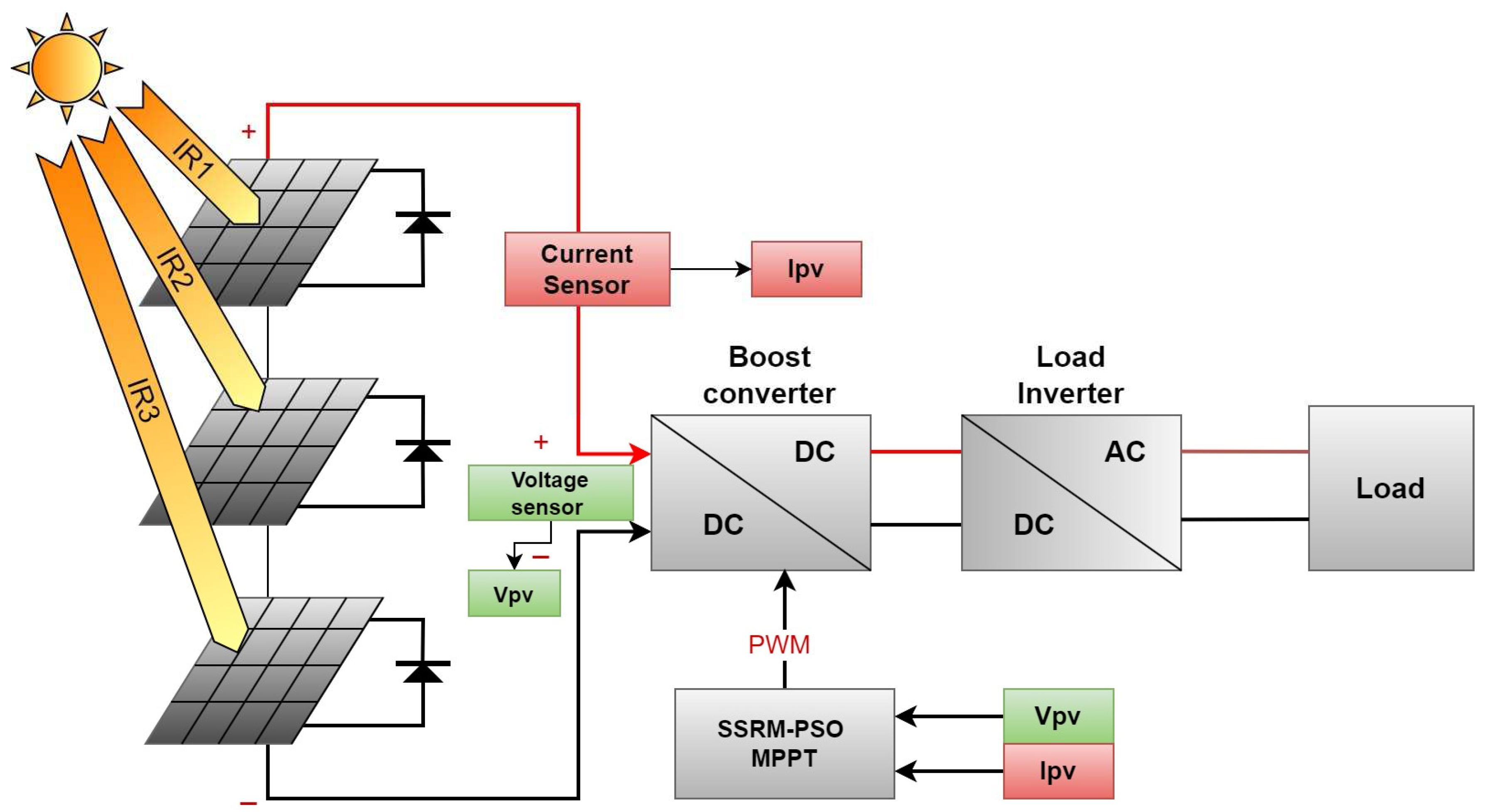

2.1. Implementation of the PSO approach for MPPT in PV systems

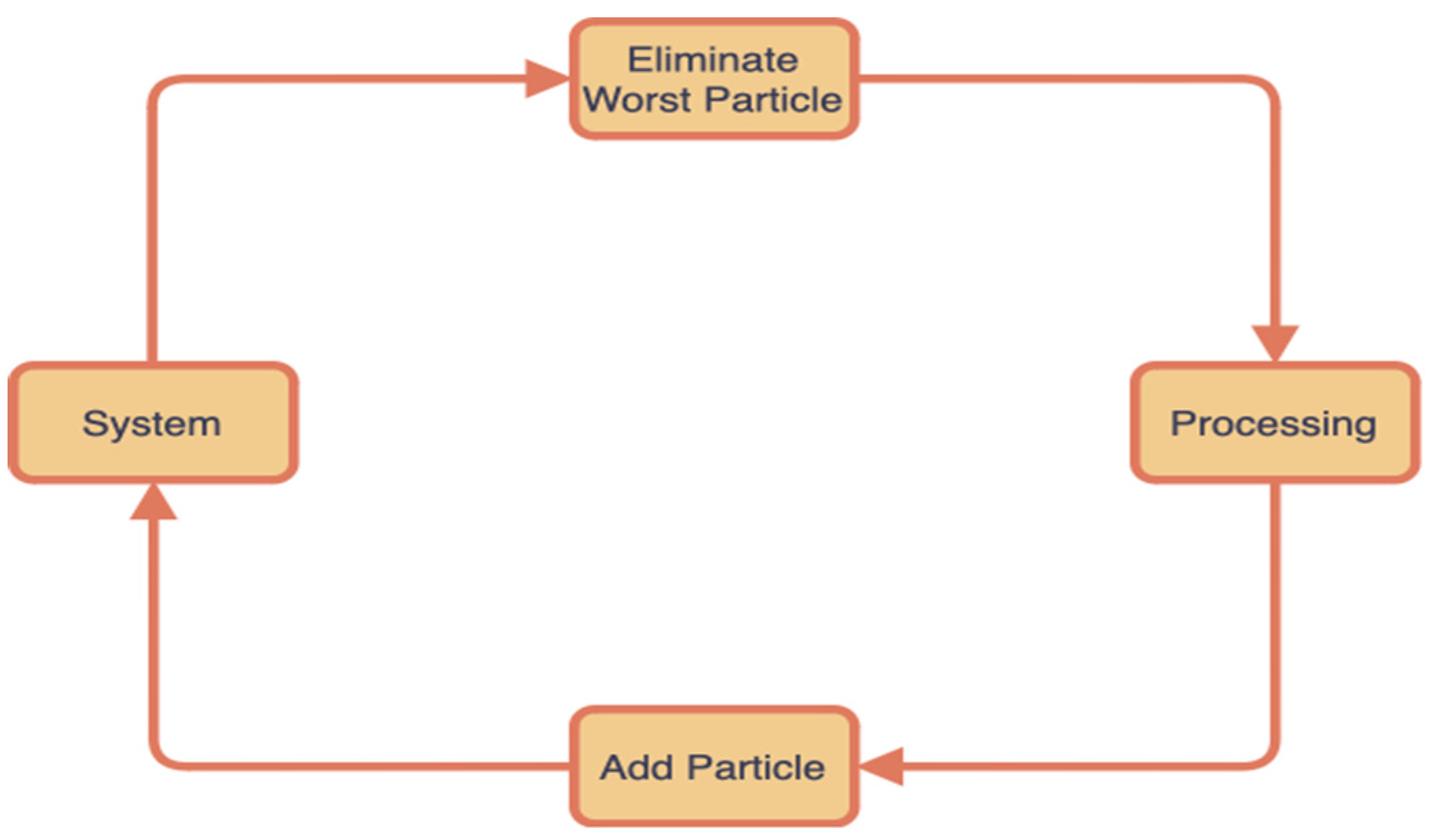

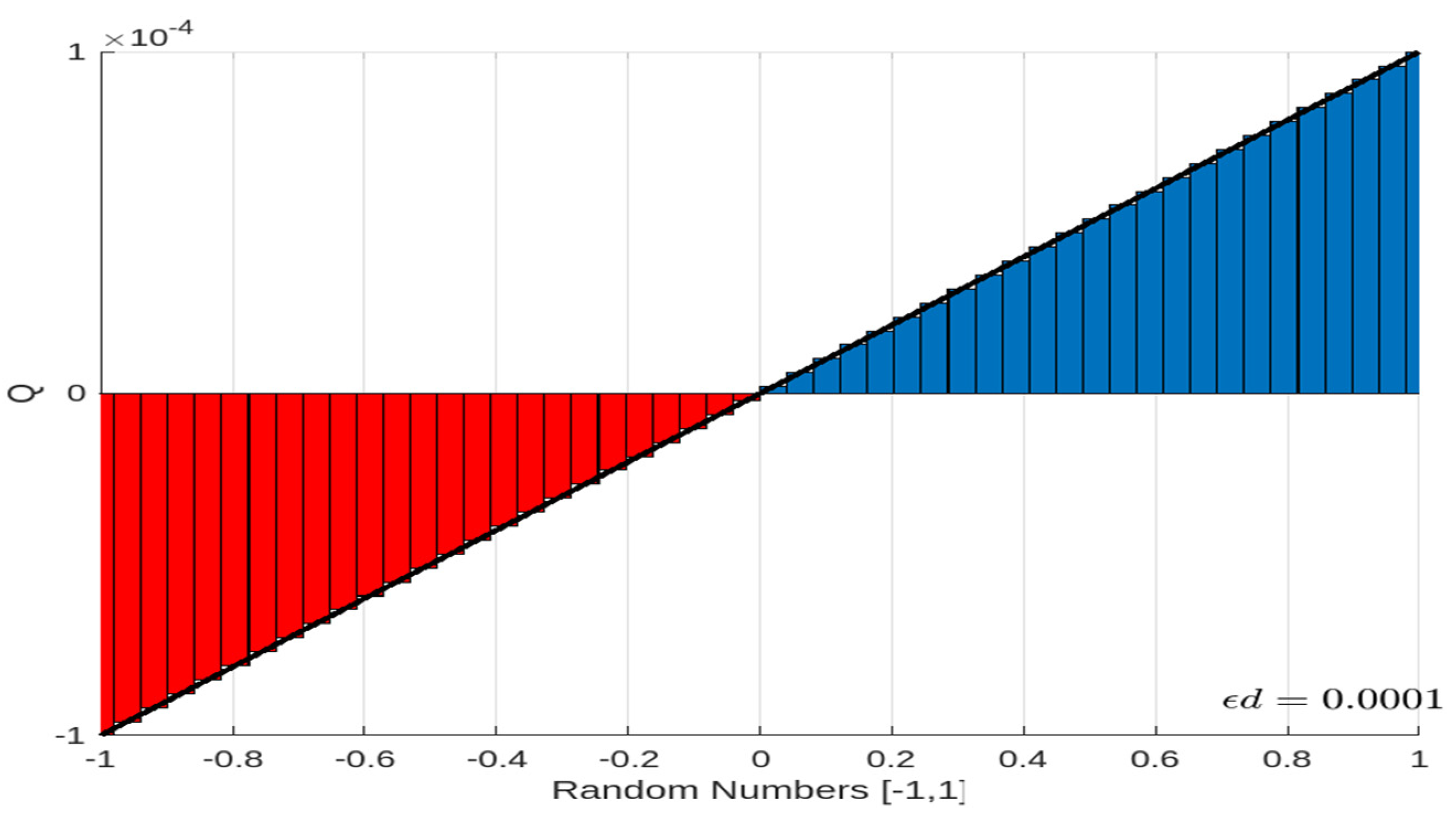

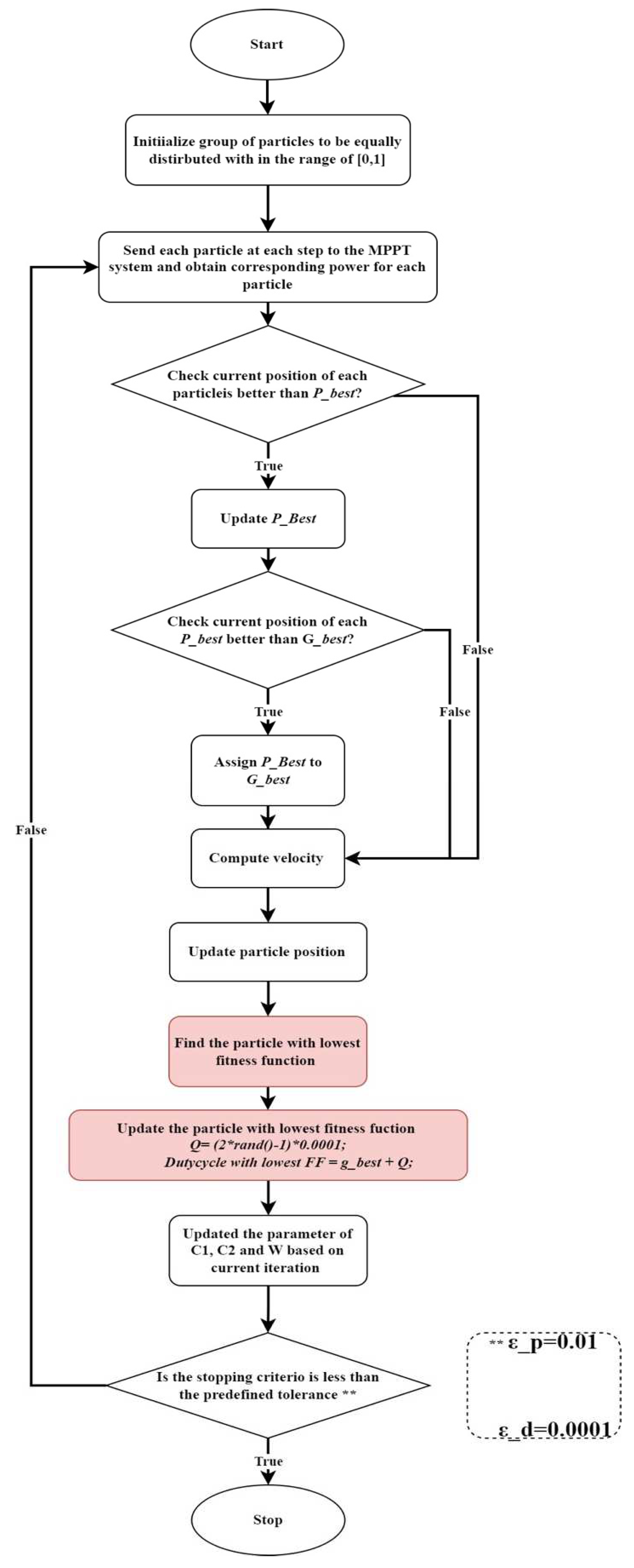

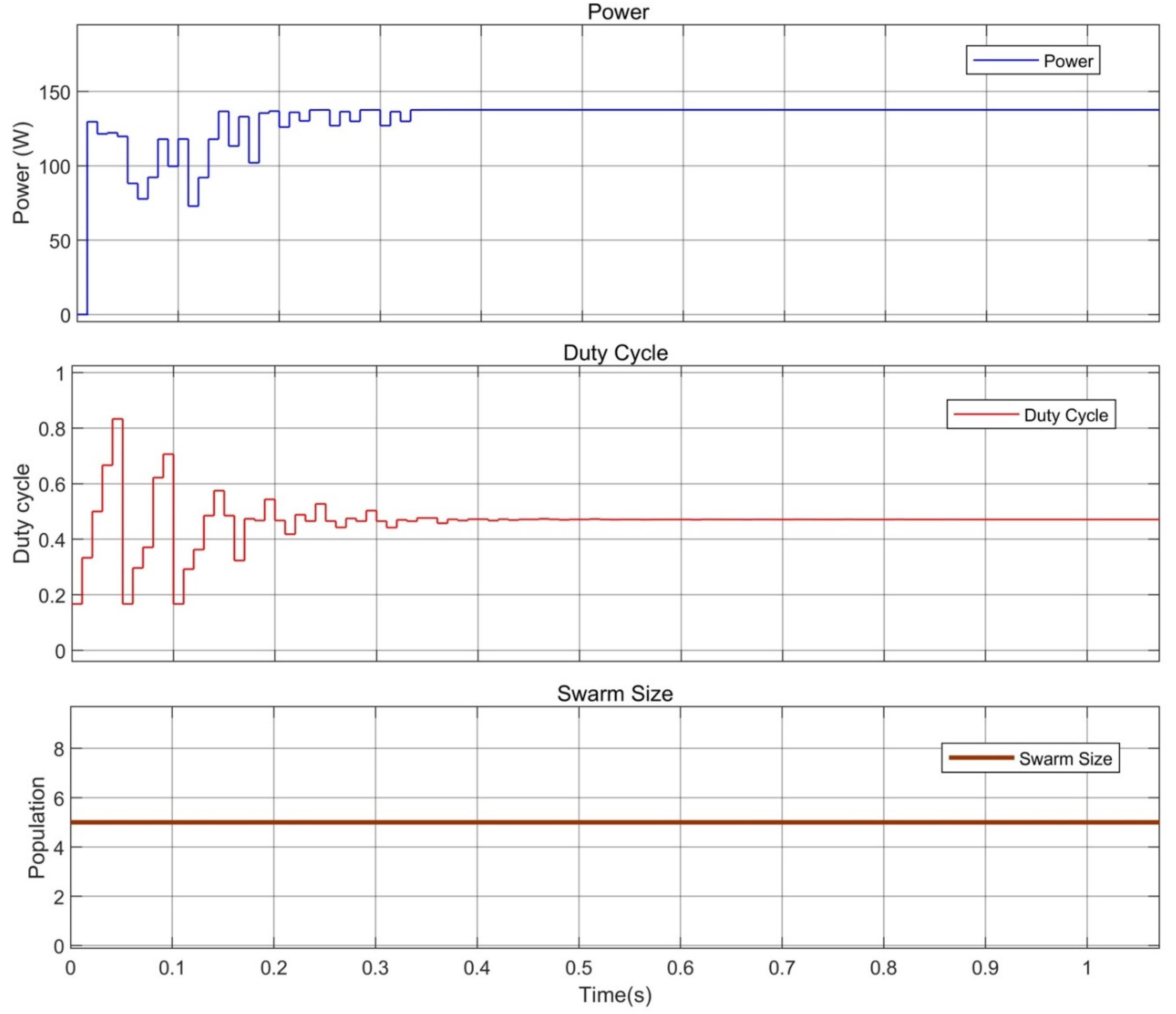

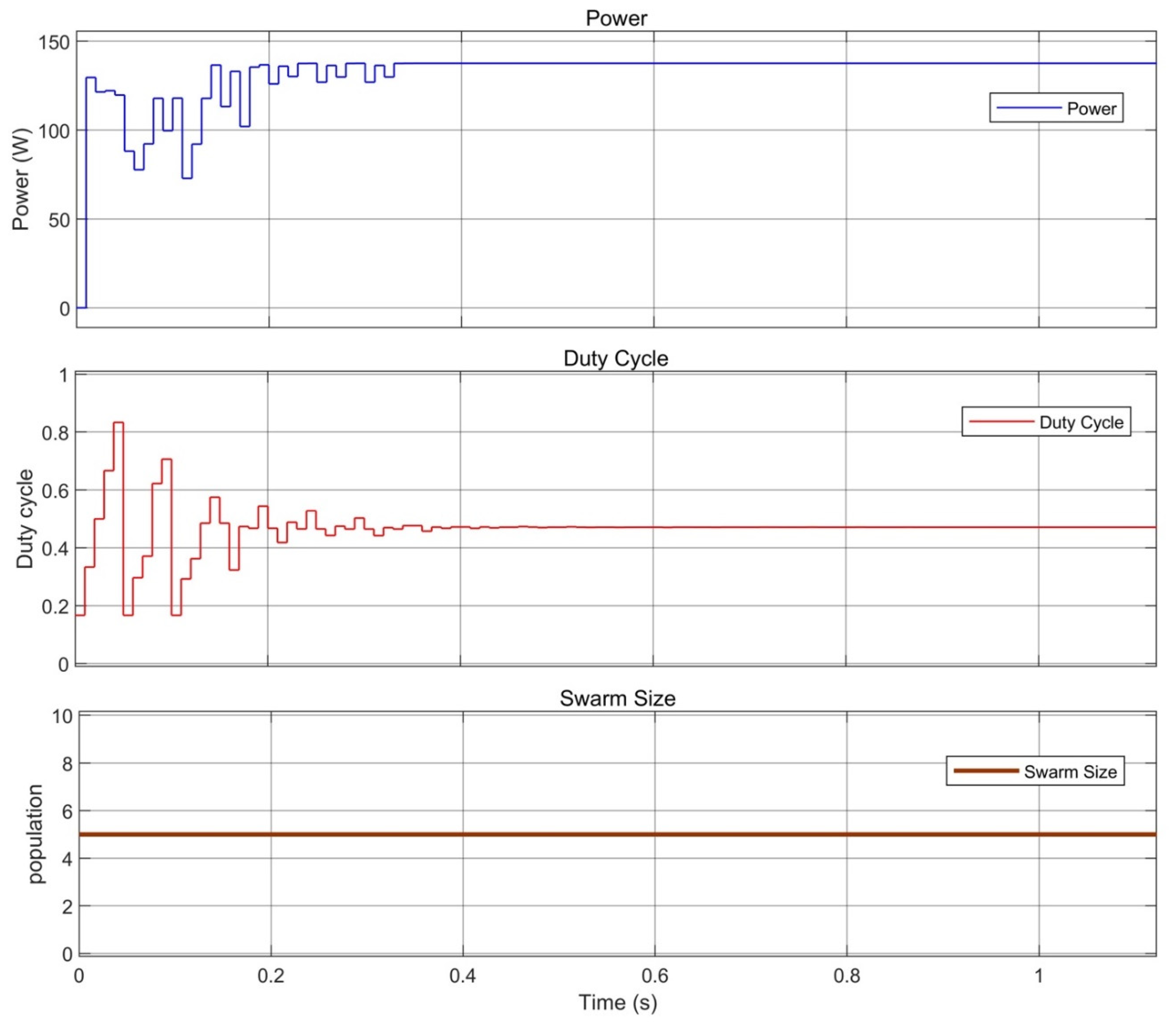

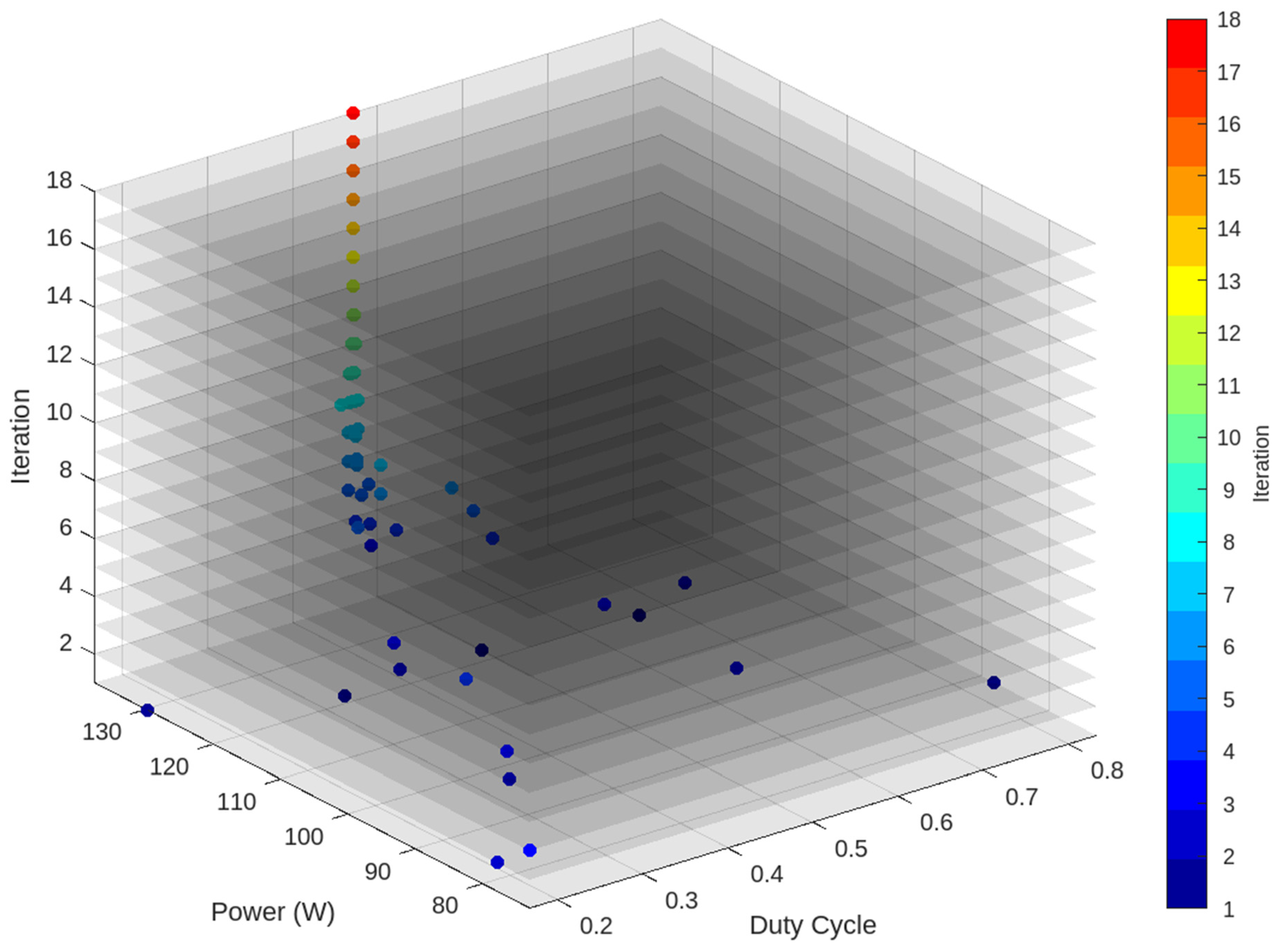

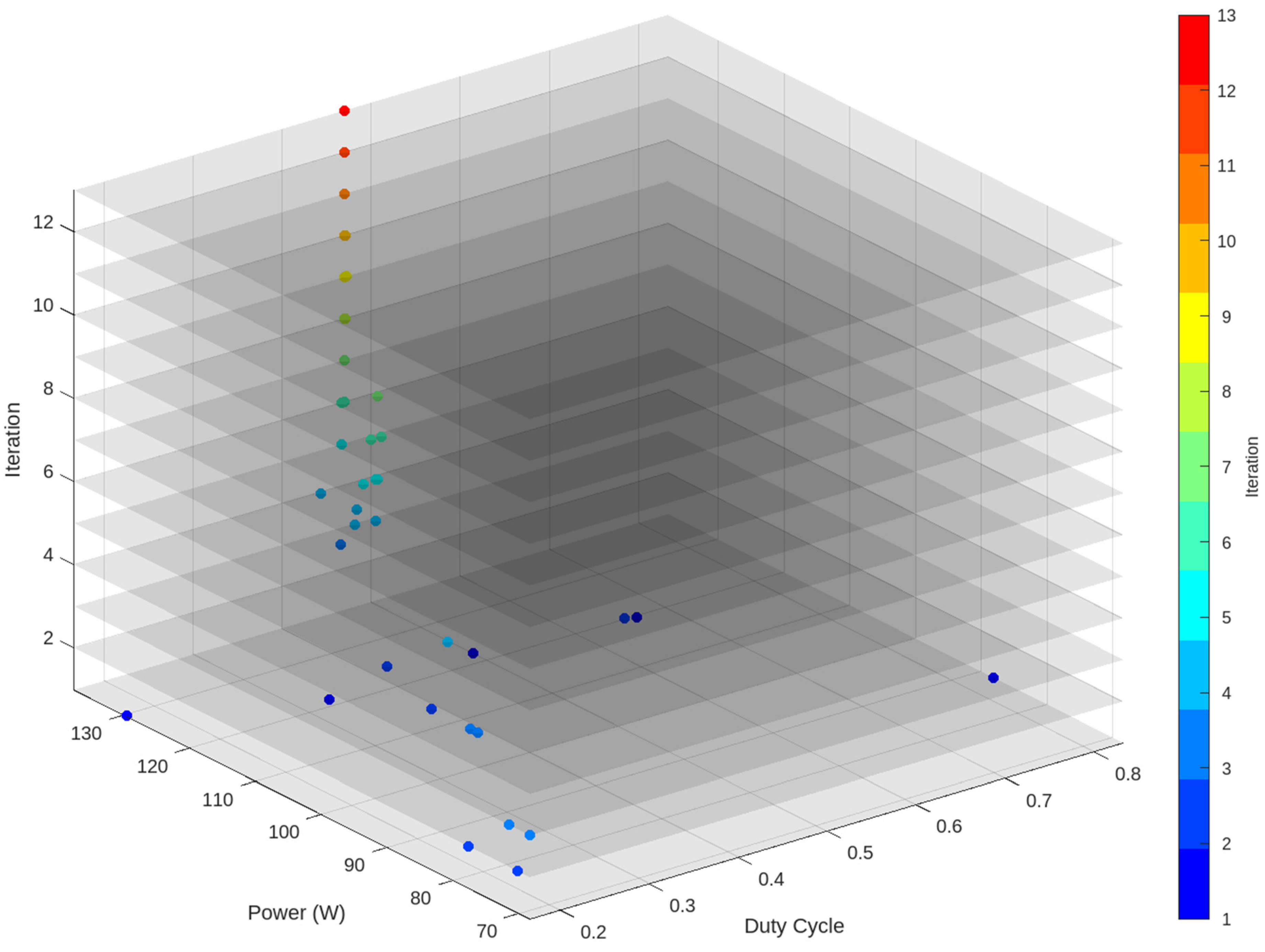

2.2. PSO Swarm Self-Reinforcement Mechanism (PSO-SSRM)

| Step1: | Initialize the particle to have a uniform distribution within the range [0.1, 0.9]. |

| Step2: | Dispatch every particle to the MPPT system at every step, then gather the corresponding power at each one. |

| Step3: | Inspect the current location of each particle. If it’s superior to , then update to this best new value. If not, proceed to Step 4. |

| Step4: | Compare each with . If is smaller than , then update accordingly. If not, advance to Step 5. |

| Step5: | Discard the particle that has the minimum fitness function, then reinforce it by adjusting its value with . |

| Step6: | Update the velocity for every particle. |

| Step7: | Update the position of the particle, considering both the global and personal best. |

| Step8: | Updated parameter of , & based on current iteration, then proceed to Step 2. |

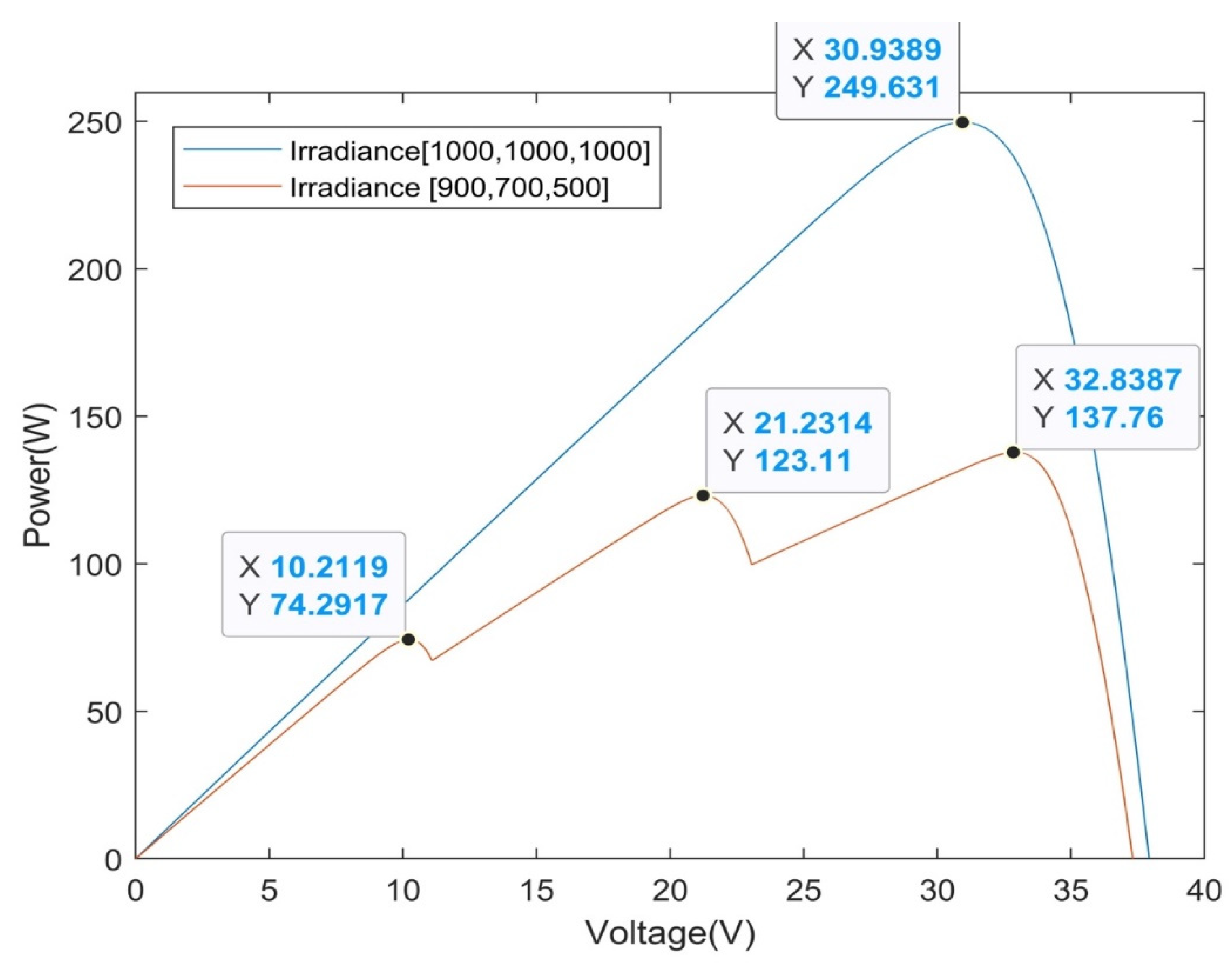

3. PV System Modeling:

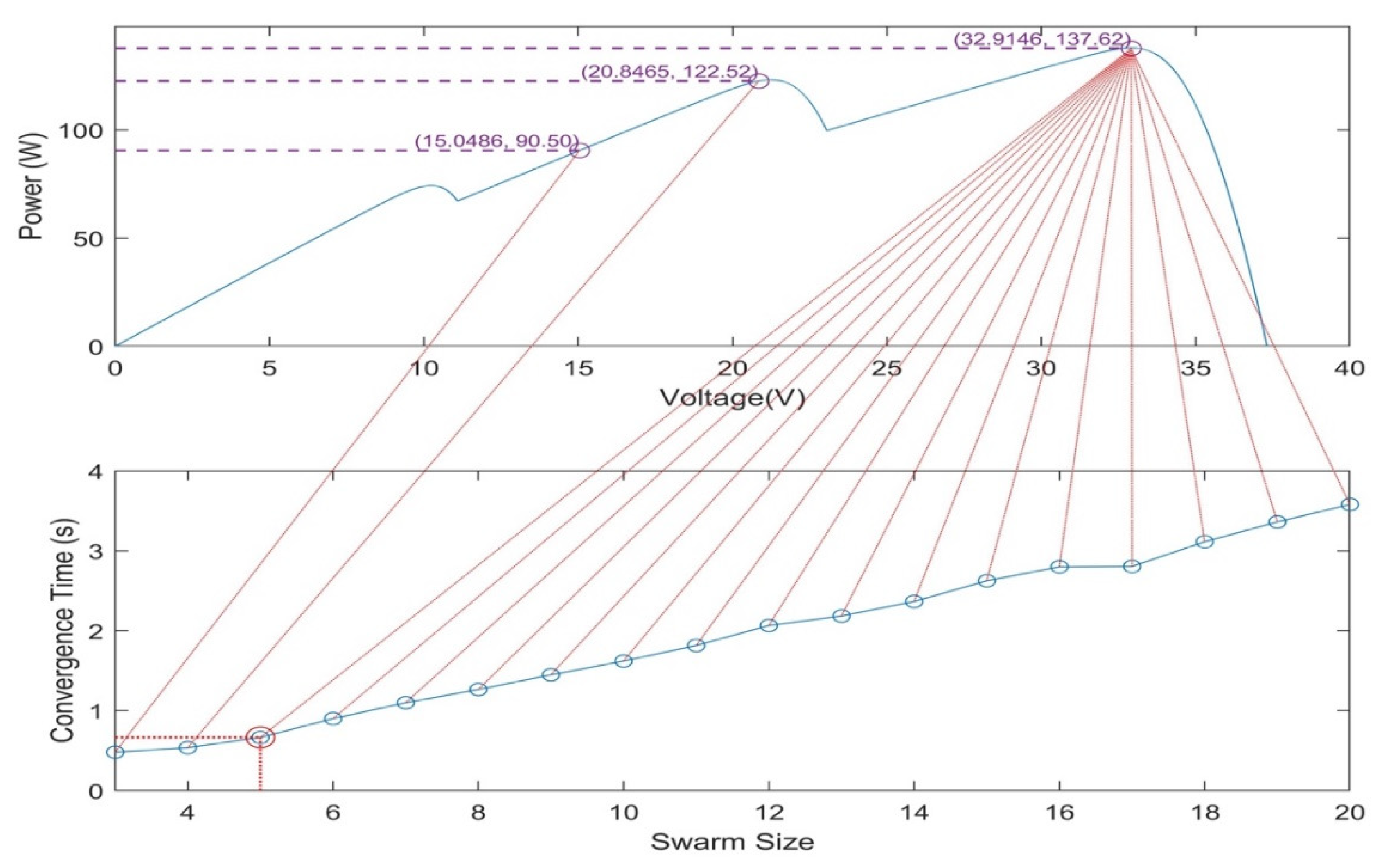

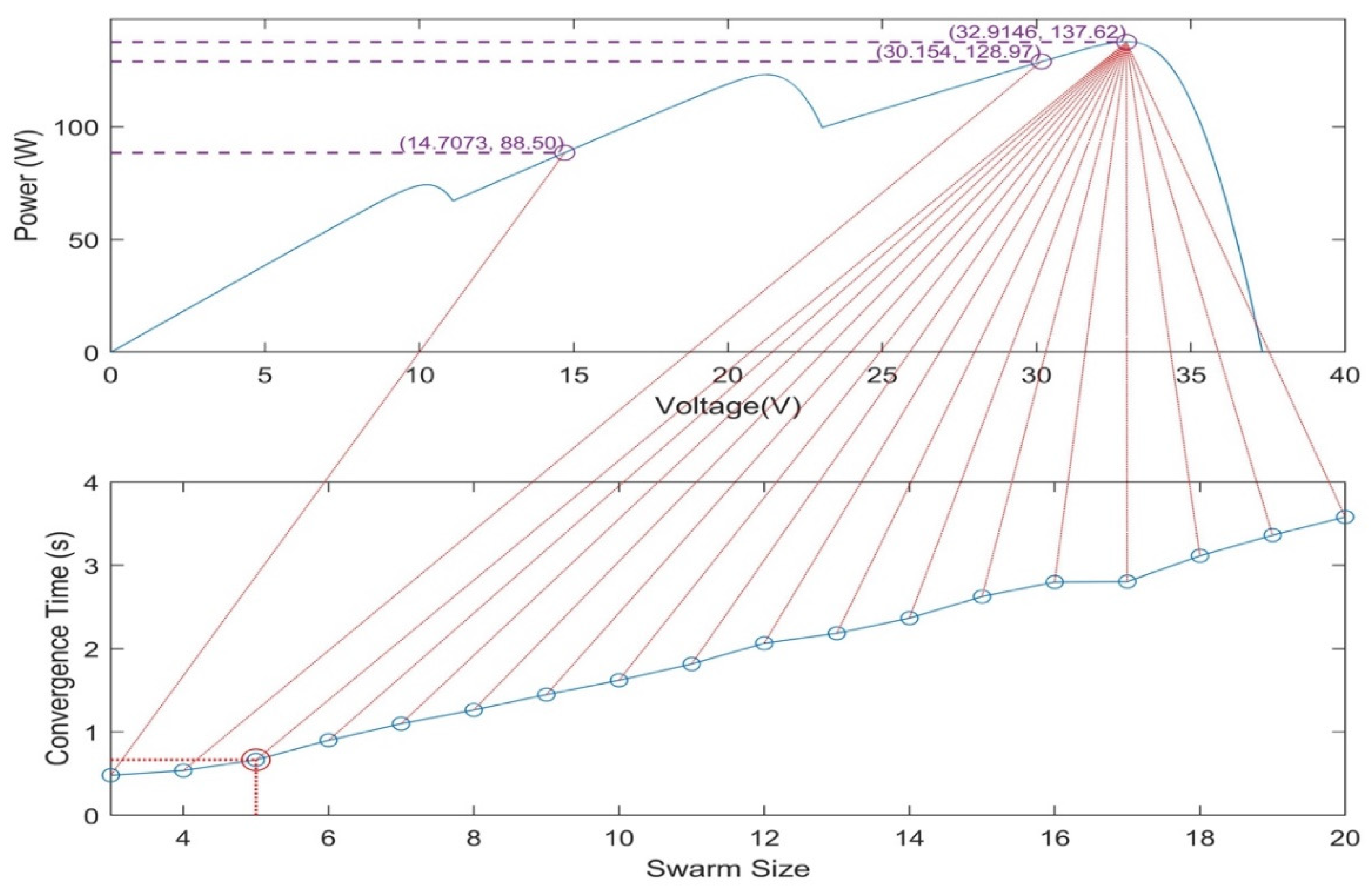

4. Simulation Analysis and Results

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

References

- A. M. Eltamaly, “Performance of MPPT Techniques of Photovoltaic Systems Under Normal and Partial Shading Conditions,” in Advances in Renewable Energies and Power Technologies, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 115-161.

- A. M. Eltamaly, H. M. H. Farh and M. S. Al Saud, “Impact of PSO reinitialization on the accuracy of dynamic global maximum power detection of variant partially shaded PV systems,” Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 7, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. M. H. Farh, M. F. Othman, A. M. Eltamaly and M. S. Al-Saud, “Maximum Power Extraction from a Partially Shaded PV System Using an Interleaved Boost Converter,” Energies, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 1–18, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. M. H. Farh, M. F. Othman and A. M. Eltamaly, “Maximum Power Extraction from Grid-Connected PV System,” in Saudi Arabia Smart Grid (SASG), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2017.

- A. M. Eltamaly, H. M. Farh and M. F. Othman, “A novel evaluation index for the photovoltaic maximum power point tracker techniques,” Solar Energy, vol. 174, p. 940–956, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly, H. M. H. Farh and A. G. Abokhalil, “A novel PSO strategy for improving dynamic change partial shading photovoltaic maximum power point tracker,” ENERGY SOURCES, PART A: RECOVERY, UTILIZATION, AND ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Farh, A. M. Eltamaly and M. S. Al-Saud, “Interleaved boost converter for global maximum power extraction from the photovoltaic system under partial shading,” IET Renewable Power Generation, vol. 13, no. 8, pp. 1232-1238, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Esram and P. L. Chapman, “Comparison of photovoltaic array maximum power point tracking techniques,” IEEE, vol. 22, no. NO. 2, pp. 439-449, 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. Ahmed and Z. Salam, “An Enhanced Adaptive P&O MPPT for Fast and Efficient Tracking Under Varying Environmental Conditions,” IEEE, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 1487-1496, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhu, L. Shang, P. Li and H. Guo, “Modified hill climbing MPPT algorithm with reduced steady-state oscillation and improved tracking efficiency,” J. Eng, vol. 2018, no. 17, p. 1878–1883, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, A.; Ayyub, M.; Khan, M.R.; Jain, A.; Husain, M.A. Realization of Incremental Conductance MPPT Algorithm for Solar Photovoltaic System. International Journal of Ambient Energy 2017, 39, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Rezk and A. M. Eltamaly, “A comprehensive comparison of different MPPT techniques for photovoltaic systems,” Solar Energy, vol. 112, p. 1–11, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly, “Performance of smart maximum power point tracker under partial shading conditions of photovoltaic systems,” Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, vol. 7, no. 4, 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Subudhi and R. Pradhan, “A Comparative Study on Maximum Power Point Tracking Techniques for Photovoltaic Power Systems,” IEEE, vol. VOL. 4, no. 1, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Teo, R. H. G. Tan, V. H. Mok, V. K. Ramachandaramurthy and C. Tan, “Impact of Partial Shading on the P-V Characteristics and the Maximum Power of a Photovoltaic String,” Energies, vol. 11, no. 7, p. 1860, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly and H. M. Farh, “Dynamic global maximum power point tracking of the PV systems under variant partial shading using hybrid GWO-FLC,” Solar Energy, pp. 306-316, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Priyadarshi, V. K. Ramachandaramurthy, S. Padmanaban and F. Azam, “An Ant Colony Optimized MPPT for Standalone Hybrid PV-Wind Power System with Single Cuk Converter,” Energies, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 167-190, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Hadji, J.-P. Gaubert and F. Krim, “Real-Time Genetic Algorithms-Based MPPT: Study and Comparison (Theoretical an Experimental) with Conventional Methods,” Energies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 459-476, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Tey, S. Mekhilef and M. Seyedmahmoudian, “Implementation of BAT algorithm as maximum power point tracking technique for photovoltaic system under partial shading conditions.pdf,” IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), pp. 2531-2535, 2018.

- J. Ahmed and Z. Salam, “A maximum power point tracking (MPPT) for PV system using cuckoo search with partial shading capability.pdf,” Applied Energy, vol. 119, pp. 118-130, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Kennedy and R. Eberhart, “Particle Swarm Optimization,” International Conference on Neural Networks (ICNN’95), p. 1942–1948, 1995.

- A. M. Eltamaly, H. M. Farh and M. S. Al-Saud, “Grade point average assessment for metaheuristic GMPP techniques of partial shaded PV systems,” IET Renewable Power Generation, vol. 13, no. 8, pp. 1215-1231, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K.-H. Chao, Y.-S. Lin and U.-D. Lai, “Improved particle swarm optimization for maximum power point tracking in photovoltaic module arrays,” Applied Energy, vol. 158, pp. 609-618, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Ahmed and Z. Salam, “A critical evaluation on maximum power point tracking methods for partial shading in PV systems,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 47, pp. 933-953, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Elgendy, B. Zahawi and D. J. Atkinson, “Assessment of perturb and observe MPPT algorithm implementation techniques for PV pumping applications,” IEEE, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 21-33, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly, M. S. Al-Saud and A. G. Abokhalil, “A novel scanning bat algorithm strategy for maximum power point tracker of partially shaded photovoltaic energy systems,” Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1093-1103, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Askarzadeh and A. Rezazadeh, “Artificial bee swarm optimization algorithm for parameters identification of solar cell models,” Applied Energy, vol. 102, pp. 943-949, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. O. Baatiah, A. M. Eltamaly and M. A. Alotaibi, “Improving Photovoltaic MPPT Performance through PSO Dynamic Swarm Size Reduction,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly, “A novel particle swarm optimization optimal control parameter determination strategy for maximum power point trackers of partially shaded photovoltaic systems,” Engineering Optimization, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 634-650, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly, Z. A. Almutairi and M. A. Abdelhamid, “Modern Optimization Algorithm for Improved Performance of Maximum Power Point Tracker of Partially Shaded PV Systems,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 13, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Shaqarin, “Particle Swarm Optimization with Targeted Position-Mutated Elitism (PSO-TPME) for Partially Shaded PV Systems,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 5, p. 3993, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Chtita, S. Motahhir, A. El Hammoumi, A. Chouder, A. S. Benyoucef, A. El Ghzizal, A. Derouich, M. Abouhawwash and S. S. Askar, “novel hybrid GWO–PSO-based maximum power point tracking for photovoltaic systems operating under partial shading conditions,” Sci Rep 12, p. 10637, 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Dagal, B. Akın and E. Akboy, “MPPT mechanism based on novel hybrid particle swarm optimization and salp swarm optimization algorithm for battery charging through simulink,” Sci Rep 12, p. 2664, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Kacimi, A. Idir, S. Grouni and M. S. Boucherit, “Improved MPPT Control Strategy for PV Connected to Grid Using IncCond-PSO-MPC Approach,” CSEE JOURNAL OF POWER AND ENERGY SYSTEMS, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 1008-1020, 2023.

- A. Sharma, A. Sharma, V. Jately, M. Averbukh, S. Rajput and B. Azzopardi, “A Novel TSA-PSO Based Hybrid Algorithm for GMPP Tracking under Partial Shading Conditions,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 3164, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. H. IBRAHIM, S. P. ANG, M. N. DANI, M. I. RAHMAN, R. PETRA and S. M. SULTHAN, “Optimizing Step-Size of Perturb & Observe and Incremental Conductance MPPT Techniques Using PSO for Grid-Tied PV System,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 13079-13090, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly, “A Novel Strategy for Optimal PSO Control Parameters Determination for PV Energy Systems,” Sustainability, no. 13, p. 1008, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly, M. S. Al-Saud and A. G. Abo-Khalil, “Performance Improvement of PV Systems’ Maximum Power Point Tracker Based on a Scanning PSO Particle Strategy,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 1185, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Kamil and M. S. Nasr, “Maximum Power Point Tracking Method for Photovoltaic System Based on Enhanced Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Under Partial Shading Condition,” International Journal of Intelligent Engineering and Systems, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 241-254, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Chawda, O. P. Mahela, N. Gupta, M. Khosravy and T. Senjyu, “Incremental Conductance Based Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Global Maximum Power Tracking of Solar-PV under Nonuniform Operating Conditions,” MDPI, vol. 10, no. 13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Al-Muthanna, S. Fang, I. AL-Wesabi, K. Ameur, H. Kotb, K. M. AboRas, H. Z. Al Garni and A. A. Mas’ud, “A High Speed MPPT Control Utilizing a Hybrid PSO-PID Controller under Partially Shaded Photovoltaic Battery Chargers,” MDPI, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 35-78, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eltamaly and H. M. H. Farh, “Maximum Power Extraction from the Photovoltaic System Under Partial Shading Conditions,” pp. 107-129, 2019.

- P. Umapathy, C. Venkataseshaiah and M. S. Arumugam, “Particle Swarm Optimization with Various Inertia Weight Variants for Optimal Power Flow Solution,” Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Abido, “Multiobjective particle swarm optimization technique for environmental/economic dispatch problem,” IEEE, 2008.

- Y. Shi and R. C. Eberhart, “Empirical study of particle swarm optimization,” IEEE, 1999.

- Y. Shi and R. C. Eberhart, “Parameter Selection in Particle Swarm Optimization,” in Lecture Notes in Computer Science—Evolutionary Programming VII, vol. 1447, pp. 591-600, 1998.

- A. Ratnaweera, S. K. Halgamuge and H. C. Watson, “Self-Organizing Hierarchical Particle Swarm Optimizer with Time-Varying Acceleration Coefficients,” IEEE, vol. 8, no. 3, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Clerc and J. Kennedy, “he particle swarm-explosion, stability, and convergence in a multidimensional complex space,” IEEE, vol. 6, pp. 58-73, 2002. [CrossRef]

- M. Clerc, “The Swarm and the Queen: Towards a Deterministic and Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization,” In Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation-CEC99, Washington, DC, vol. 3, p. 1951–1957, 1999.

- M. Jiang, Y. P. Luo and S. Y. Yang, “Particle swarm optimization-stochastic trajectory analysis and parameter selection,” In Swarm Intelligence, Focus on Ant and Particle Swarm Optimization, p. 179–198, 2007.

- W. Zhang, D. Ma, J.-j. Wei and H.-f. Liang, “A parameter selection strategy for particle swarm optimization based on particle positions.,” Expert Systems with Applications, p. 3576–3584, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. R. Harrison, A. P. Engelbrecht and B. M. Ombuki-Berman, “An adaptive particle swarm optimization algorithm based on optimal parameter regions,” IEEE, pp. 1-8, 2017.

| Specification | Value |

| Maximum Power per module | 83.28 W |

| Open Circuit voltage | 12.64 V |

| Short Circuit current | 8.62 A |

| Voltage at MPP | 10.32 V |

| Current at MPP | 8.07 A |

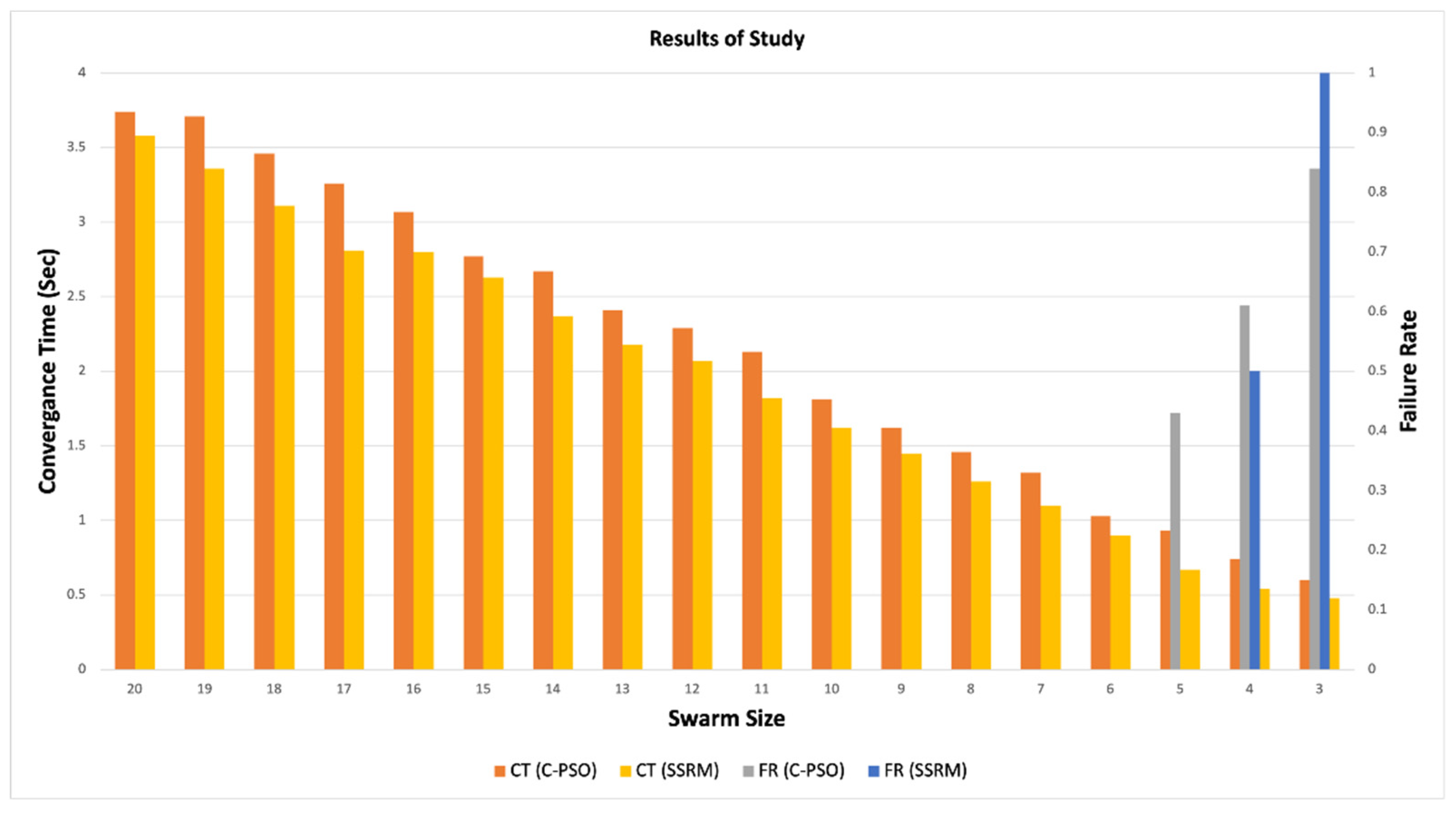

| SS | C-PSO | SSRM-PSO | ||

| CT | FR | CT | FR | |

| 20 | 3.74 | 00% | 3.58 | 0% |

| 19 | 3.71 | 0% | 3.36 | 0% |

| 18 | 3.46 | 0% | 3.11 | 0% |

| 17 | 3.26 | 0% | 2.81 | 0% |

| 16 | 3.07 | 0% | 2.8 | 0% |

| 15 | 2.77 | 0% | 2.63 | 0% |

| 14 | 2.67 | 0% | 2.37 | 0% |

| 13 | 2.41 | 0% | 2.18 | 0% |

| 12 | 2.29 | 0% | 2.07 | 0% |

| 11 | 2.13 | 0% | 1.82 | 0% |

| 10 | 1.81 | 0% | 1.62 | 0% |

| 9 | 1.62 | 0% | 1.45 | 0% |

| 8 | 1.46 | 0% | 1.26 | 0% |

| 7 | 1.32 | 0% | 1.1 | 0% |

| 6 | 1.03 | 0% | 0.9 | 0% |

| 5 | 0.93 | 43% | 0.67 | 0% |

| 4 | 0.74 | 61% | 0.54 | 50% |

| 3 | 0.6 | 84% | 0.48 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).