Submitted:

24 October 2023

Posted:

25 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Cement Formulations

- Crumb rubber powder from waste tire rubber (WTR) with a granule size less than 0.5 mm obtained from Kargo Recycling Nederweert, The Netherlands,

- Basoblock™ LD 105, a styrene-butadiene latex from BASF,

- Paragas® , a modified polyethylenimine (water soluble polymer) from BASF,

- Pozzolan from Heidelberg Cement (50% clinker, 25% slag en 25% pozzolan),

- Polypropylene (PP) and polyacrylonitrile (PAN) fibres 3 mm length, 35 and 12 micron diameter from Shandong Dachuan New Materials Co.,Ltd, China.

Sample Preparation

Thermal Cycling Tests

Drying Shrinkage Tests

3. Results

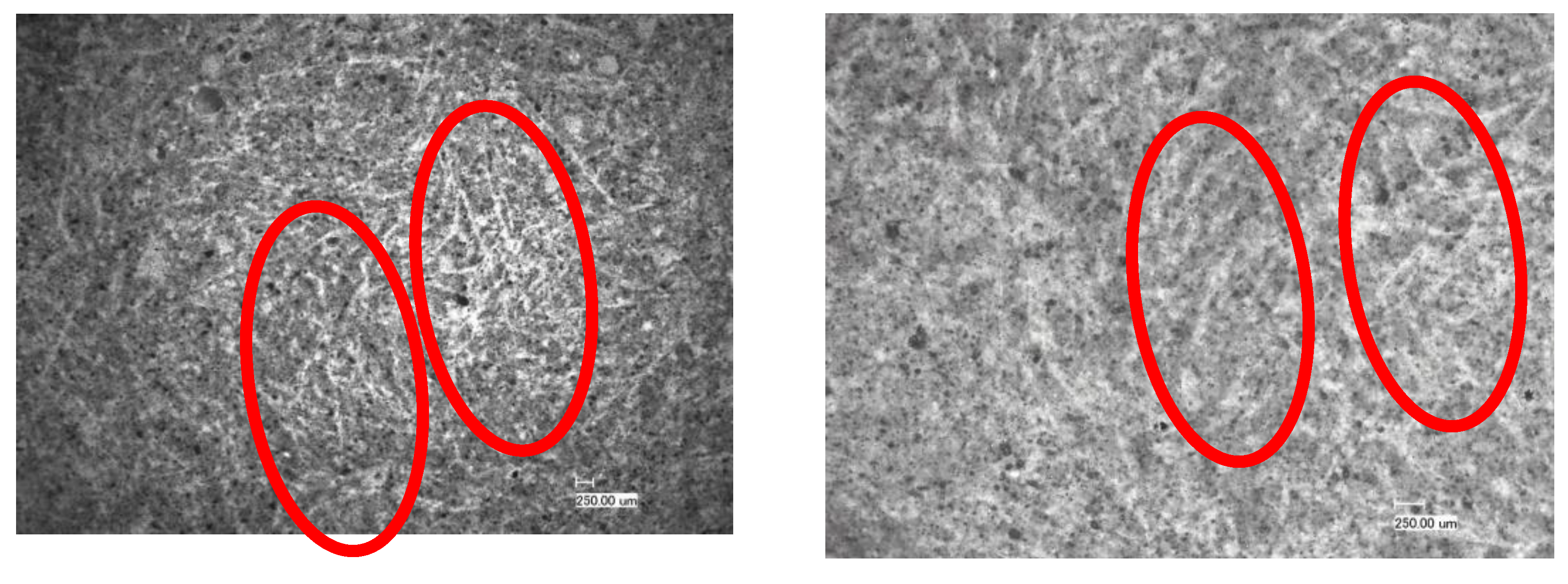

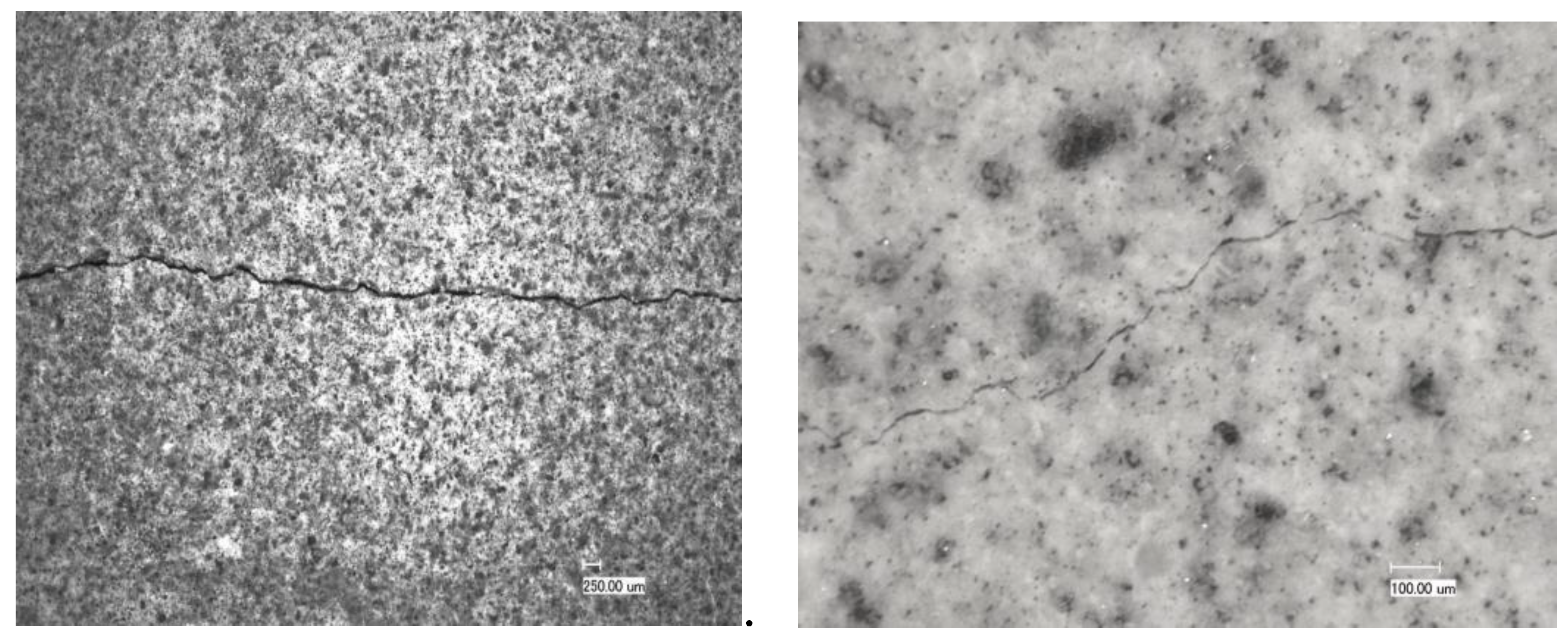

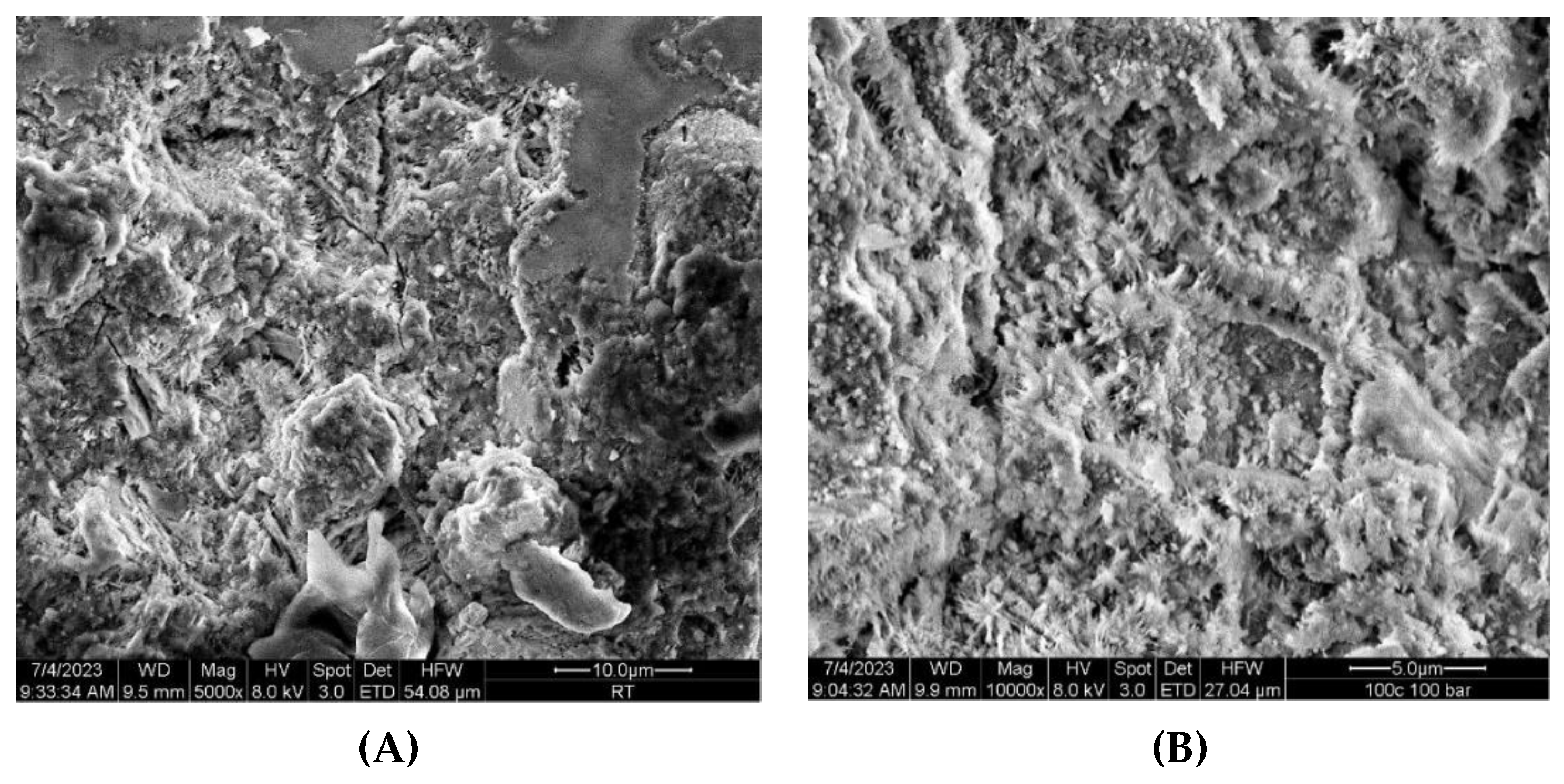

Thermal Cycling Tests

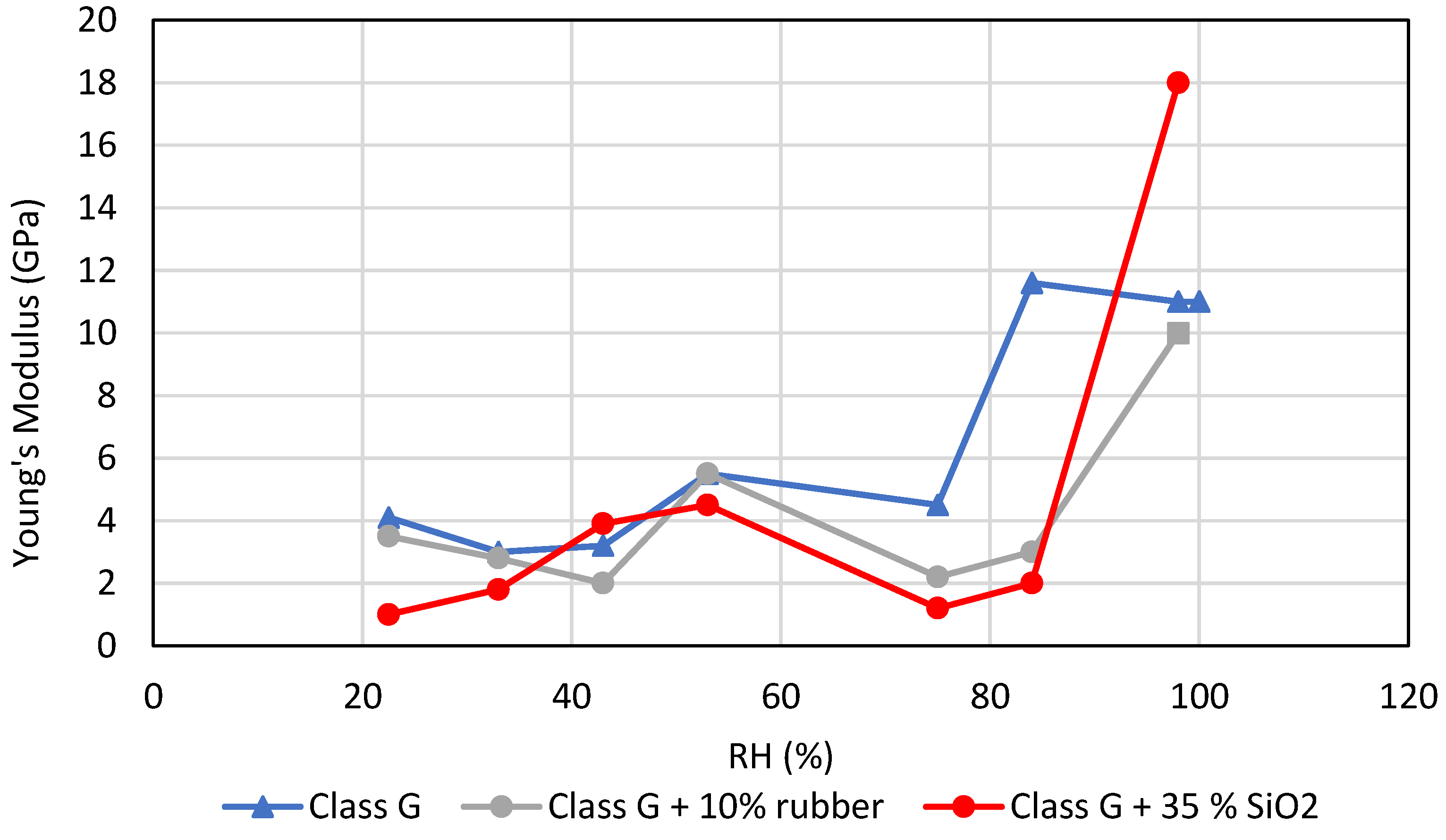

Drying Shrinkage Tests

4. Discussion

Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- IRENA - International Renewable Energy Agency, https://www.irena.org/News/articles/2023/May/Boosting-the-Global-Geothermal-Market-Requires-Increased-Awareness-and-Greater-Collaboration.

- Kuanhai, D., Yue, Y., Yi, H., Zhonghui, L., Yuanhua, L., Experimental study on the integrity of casing-cement sheath in shale gas wells under pressure and temperature cycle loading, (2020) Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 195, art. no. 107548. [CrossRef]

- Alberdi-Pagola, P. and Fischer, G. 2023. Quantification of Shrinkage-Induced Cracking in Oilwell Cement Sheaths, SPE Drill & Compl 1–17, SPE-214685-PA. [CrossRef]

- Vralstad T., Skorpa R., Opedal N., De Andrade J., Effect of thermal cycling on cement sheath integrity: Realistic ex-perimental tests and simulation of resulting leakages, (2015) SPE-178467-MS. [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, J., Sangesland, S., Todorovic, J., Vrålstad, T., Cement sheath integrity during thermal cycling: A novel approach for experimental tests of cement systems, (2015) SPE-173871-MS.

- N. M.P. Low, J.J. Beaudoin, Flexural strength and microstructure of cement binders reinforced with wollastonite mi-cro-fibres, Cement and Concrete Research, 23, (1993) 905-916.

- M. L. Berndt, A. J. Philippacopoulos, Incorporation of fibers in geothermal well cements, Geothermics, 31, (2002) 643-656.

- Doğan, C. & Demir, İ. (2021). Polymer fibers and effects on the properties of concrete . Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi , 11 , 438-451. [CrossRef]

- Eldin N.N., Senouci A.B., Rubber-tire particles as concrete aggregate, (1993) Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 5, 478 – 496.

- Segre, N., Ostertag, C., Monteiro, P.J.M., Effect of tire rubber particles on crack propagation in cement paste, (2006) Materials Research, 9, 311-320. [CrossRef]

- AC1 Committee 548.1R-2008, Guide for the Use of Polymers in Concrete, American Concrete Institute.

- Y. Ohama, Principle of latex modification and some typical properties of latex modified mortars and concretes, ACI Mater. J. 84 (12) (1987) 511–518.

- S. Pascal, A. Alliche, P. Pilvin, Mechanical behavior of polymer modified mortars, Mater. Sci. Eng. 380 (1–2) (2004) 1–8.

- H. Justnes, B.A. Øye, The microstructure of polymer cement mortars, Nordic Concr. Res. 9 (1990) 69-80.

- Song, J., Xu, M., Liu, W., Wang, X., Wu, Y., Synergistic Effect of Latex Powder and Rubber on the Properties of Oil Well Cement-Based Composites, (2018) Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, (2018) art. no. 4843816. [CrossRef]

- Kuanhai, D., Yue, Y., Yi, H., Zhonghui, L., Yuanhua, L., Experimental study on the integrity of casing-cement sheath in shale gas wells under pressure and temperature cycle loading, (2020) Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 195, art. no. 107548. [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, Lewis. "Humidity fixed points of binary saturated aqueous solutions." Journal of research of the National Bureau of Standards. Section A, Physics and chemistry 81.1 (1977): 89.

- Song, Y., Wu, Q., Agostini, F., Skoczylas, F., Bourbon, X., Concrete shrinkage and creep under drying/wetting cycles, (2021) Cement and Concrete Research, 140, art. no. 106308. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Xinxiang , Kuru, Ergun , Gingras, Murray , Iremonger, Simon , Chase, Preston , and Zichao Lin. "Characterization of the Microstructure of the Cement/Casing Interface Using ESEM and Micro-CT Scan Techniques." SPE J. 26 (2021): 1131–1143. [CrossRef]

- K. Kovler, S. Zhutovsky, Overview and future trends of shrinkage research, Mater. Struct. 39 (9) (2006) 827–847. [CrossRef]

- Brue, F.N.G., Davy, C.A., Burlion, N., Skoczylas, F., Bourbon, X., Five year drying of high-performance concretes: Effect of temperature and cement-type on shrinkage, (2017) Cement and Concrete Research, 99, 70-85. [CrossRef]

- Cagnon, H., Vidal, T., Sellier, A., Bourbon, X., Camps, G., Drying creep in cyclic humidity conditions, (2015) Cement and Concrete Research, 76, pp. 91-97. [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.-J., Mechanical and durability performance of polyacrylonitrile fiber reinforced concrete, (2015) Materials Re-search, 18 (6), pp. 1298-1303. [CrossRef]

- Chinchillas-Chinchillas, M.J., Orozco-Carmona, V.M., Gaxiola, A., Alvarado-Beltrán, C.G., Pellegrini-Cervantes, M.J., Baldenebro-López, F.J., Castro-Beltrán, A., Evaluation of the mechanical properties, durability and drying shrinkage of the mortar reinforced with polyacrylonitrile microfibers, (2019) Construction and Building Materials, 210, pp. 32-39. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., Xu, Q., Microscopic, physical and mechanical analysis of polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete, (2009) Materials Science and Engineering A, 527 (1-2), pp. 198-204. [CrossRef]

- Torsæter, M., Todorovic, J., Lavrov, A., Structure and debonding at cement-steel and cement-rock interfaces: Effect of geometry and materials, (2015) Construction and Building Materials, 96, 164-171. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Composition |

|---|---|

| TestCEM B | class G |

| TestCEM R10 | class G + 10 % rubber particles |

| TestCEM R20 | class G + 20 % rubber particle |

| TestCEM si35 | class G + 35 % silica fume |

| TestCEM si40 | class G + 40 % silica fume |

| TestCEM BB | class G + 10 % Basoblock |

| TestCEM PG | class G + 20 % Paragas |

| TestCEM PP | class G + 1.5 % PP fibers |

| TestCEM PAN | class G + 1.5 % PAN fibers |

| TestCEM Poz | 50 % class G + 25 % slag + 25 % pozzolan |

| TestCEM PAN-BB | class G + 1 % PAN fibers + 10 % Basoblock |

| TestCEM PAN-R10 | Class G + 1 % PAN fibers +10 % rubber particles |

| TestCEM R-BB | class G + 10 % rubber particles + 10 % Basoblock |

| Saturated Salt Solution | RH (%) |

|---|---|

| CH3COOK | 22.5 |

| MgCl2 | 33 |

| K2CO3 | 43 |

| Mg(NO3)2 | 53 |

| NaCl | 75 |

| KCl | 84 |

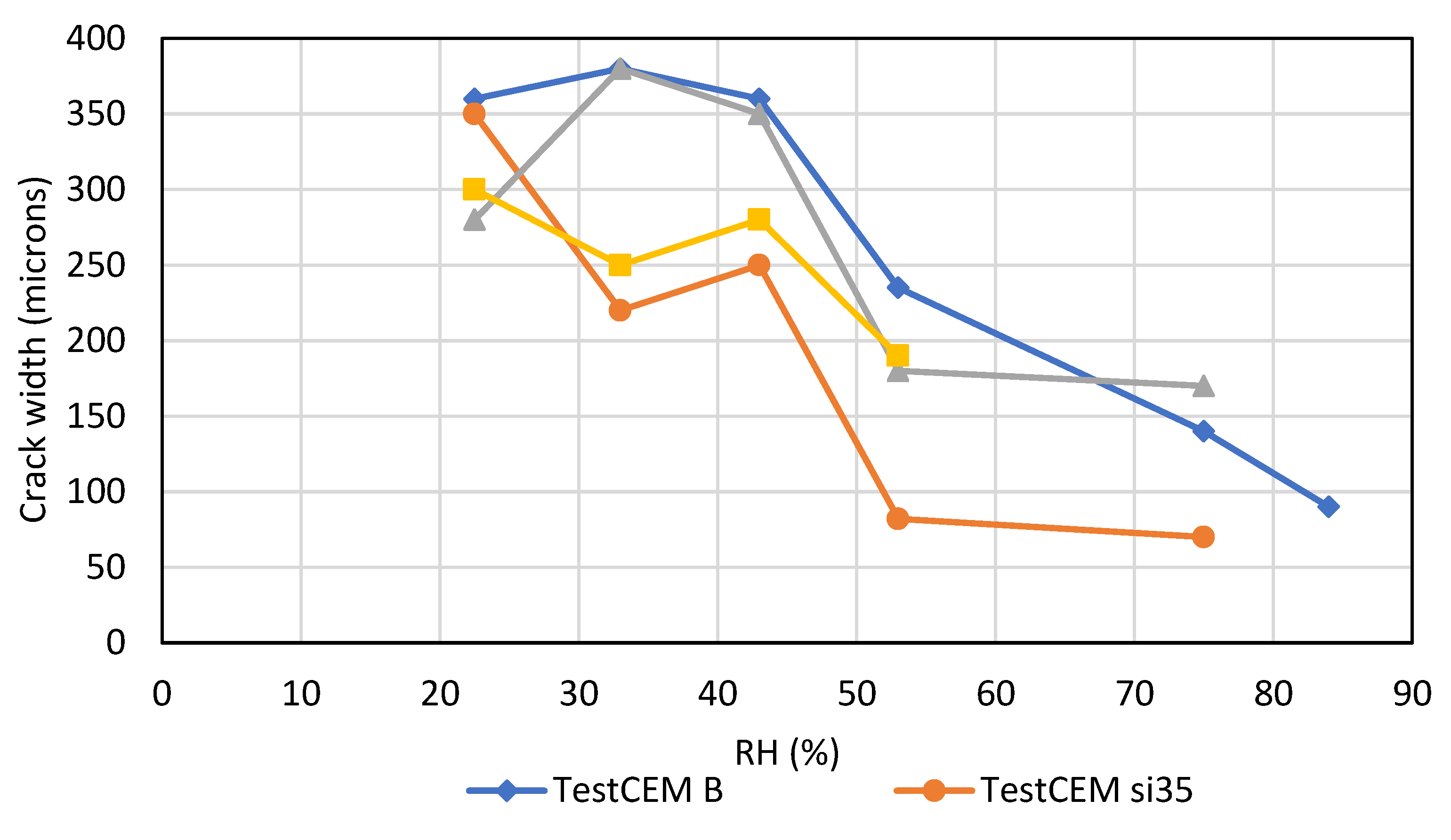

| Sample | Crack Width Opening (μm) |

|---|---|

| TestCEM B | 45 |

| TestCEM si35 | 44 |

| TestCEM R10 | 35 |

| TestCEM R20 | - |

| TestCEM PG | 12 |

| TestCEM PP | - |

| TestCEM PAN | - |

| TestCEM PAN-BB | - |

| TestCEM PAN-R10 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).