1. Introduction

Multiferroic materials exhibit more than one ferroic order, such as ferromagnetism, ferroelectricity, and ferroelasticity [

1]. They have recently attracted significant attention due to their potential for applications in spintronics, magnetoelectrics, nonvolatile memories, sensors, and electrically tunable magnetic microwave devices [

2,

3]. A ferromagnetic-ferroelectric composite is a multiferroic that shows a variation of its ferroelectric order parameters when subjected to an external magnetic field, direct magnetoelectric (ME) effect, or changes in magnetic parameters in an applied electric field, converse ME effect. [

4]. In ME materials, the induced electric polarization P is related to the applied external magnetic field H by P = αH, where α is a second order ME-susceptibility tensor. Another parameter of importance is the ME voltage coefficient (MEVC) α

E=δE/δH, which is related to α by α=ε

0ε

rα

E, where ε

r is the relative permittivity of the material. According models for the ME effects in single-phase materials, the upper bound α is limited to the relation α ≤ (με)

1/2, where μ and ε are the permeability and permittivity of the material, respectively [

5]. One of the known single-phase multiferroic with a large α at room temperature is BiFeO

3 [

6]. In composite ME materials, the α can be ehnaced by exploiting the strain mediated interactions between the two phases [

4].

To obtain the maximum ME voltage coefficient (α

E) in a ferromagnetic-ferroelectric composite an optimized magnitude of the DC magnetic bias field H is needed. A maximum in the α

E occurs when the piezomagnetic coefficient q=dλ/dH (where λ is the magnetostriction) of ferro/ferrimagnetic component of the composite is also maximum. Hence a bias magnetic field, in general, is essential to achieve strong ME response. The need for a bias field, however, could be eliminated with a self-bias in the ferromagnetic. There are several avenues to accomplish the self-bias condition such as a large magneto-crystalline anisotropy field or the use of a functionally graded ferromagnet [

7,

8,

9]. Other avenues include the use of compositionally graded ferromagnetic phase [

10]. There are several experimental findings [

11,

12,

13] and theoretical models [

11,

12,

13] on graded ME composites. In laminated composites changing the mechanical resonance modes through electrical connectivity evoke the zero bias coupling when the bending strain activates a built-in bias [

9]. Thin films that rely on magnetic field dependence of resonant frequency and angular dependence of exchange bias field [

14,

15] can also show zero-bias ME effect. It is also shown that a homogeneous magnetostrictive phase can also produce zero bias ME effect [

16]. Cofired layered composites consisting of textured Pb(Mg

1/3Nb

2/3)O

3-PbTiO

3 and Cu and Zn doped NiFe

2O

4 show a giant zero-bias ME coefficient ~1000 mV/cm Oe [

17] wherein built in stress induces zero-bias effect.

Here we discuss a novel approach for a self-biased ME composite with the use of a ferromagnetic layer consisting of both M-type barium ferrite hexagonal ferrite, BaO 6Fe

2O

3 (BaM), with uniaxial anisotropy on the order of ~ 17.4 kOe, and nickel ferrite NiFe

2O

4 with high magnetostriction and piezomagnetic coefficient q [

18]. Composites of BaM-NFO with (1-x) wt.% of BaM and x wt.% of NFO, (BNx), were prepared by sintering powders of both ferrites. X-ray diffraction revealed the presence of both BaM and NFO and the absence of impurity phases. Scanning electron microscopy images showed crystallites of both ferrites. Magnetostriction λ measurements for BNx indicated values increased with increasing x and for x > 65 reached values comparable that of pure NFO. High frequency measurements were carried out to determine the anisotropy field H

A from dependence of the ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) frequency f

r on static magnetic field H. The in-plane H

A values in BNx were found to well above the value of 500 Oe for pure NFO. Platelets of sintered BNx were bonded to PZT to form bilayers for ME voltage coefficient (MEVC) measurements that showed a significant zero-field ME effects. Details on results of the studies are provided in the following sections.

3. Results

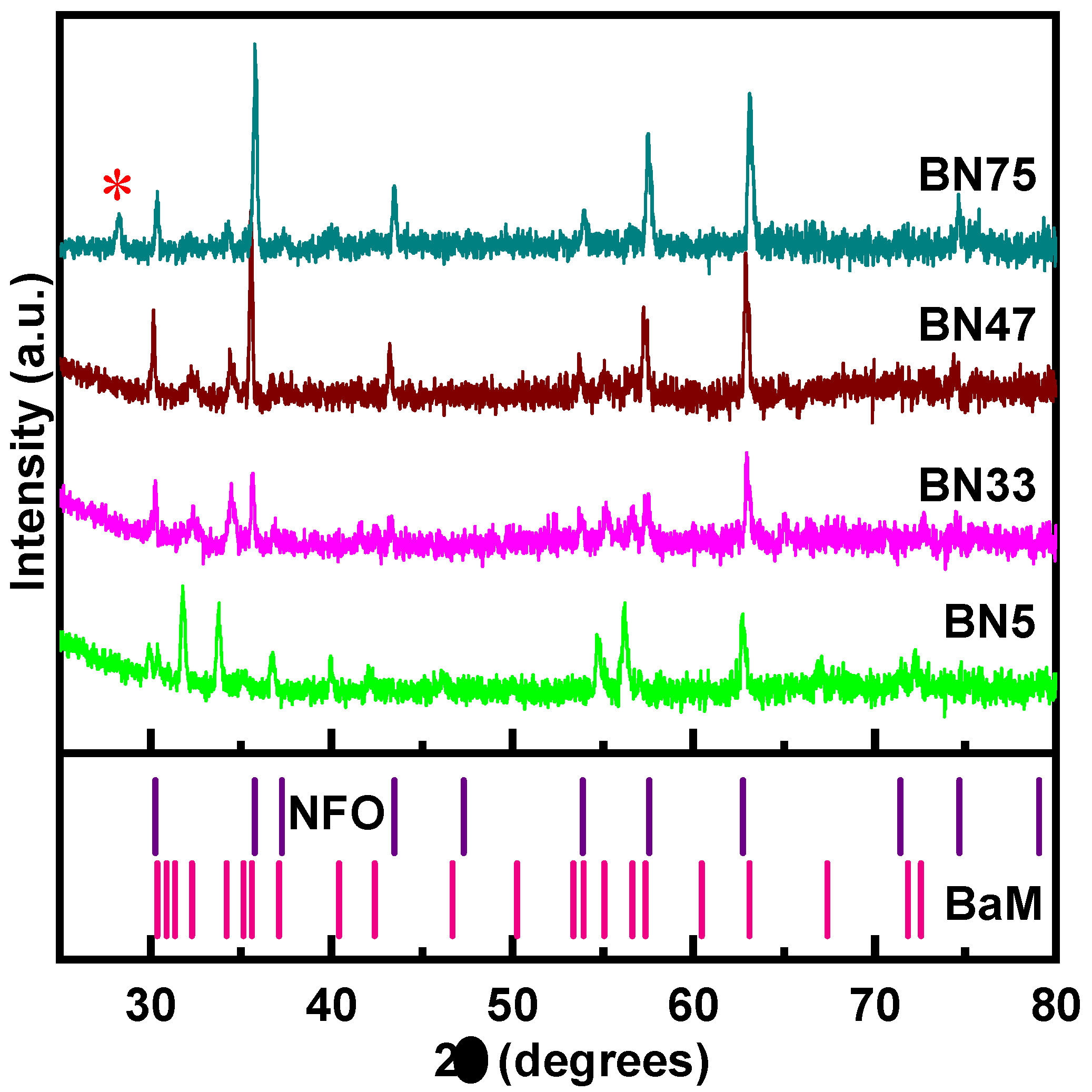

Representative powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the BNx samples are shown in

Figure 1. XRD patterns other BNx compositions are shown in the Figure S-1 in the Supplement. The XRD patterns show diffraction peaks from NFO and BaM. With increasing x-values, the NFO lines become stronger and BaM lines get weaker as expected. A small amount of an impurity phase, identified as antiferromagnetic Ba

5Fe

2O

8, is present only in BN41, BN44 and BN75 [

19]. Usually, Ba

5Fe

2O

8 type impurities (5BaO+Fe

2O

3) occur during the sintering of BaO and Fe

2O

3 based ferrites, especially in BaFe

12O

19 [

19]. However, since Ba

5Fe

2O

8 is AFM, the overall ME character of the BNx-PZT bilayers is expected to be unaffected.

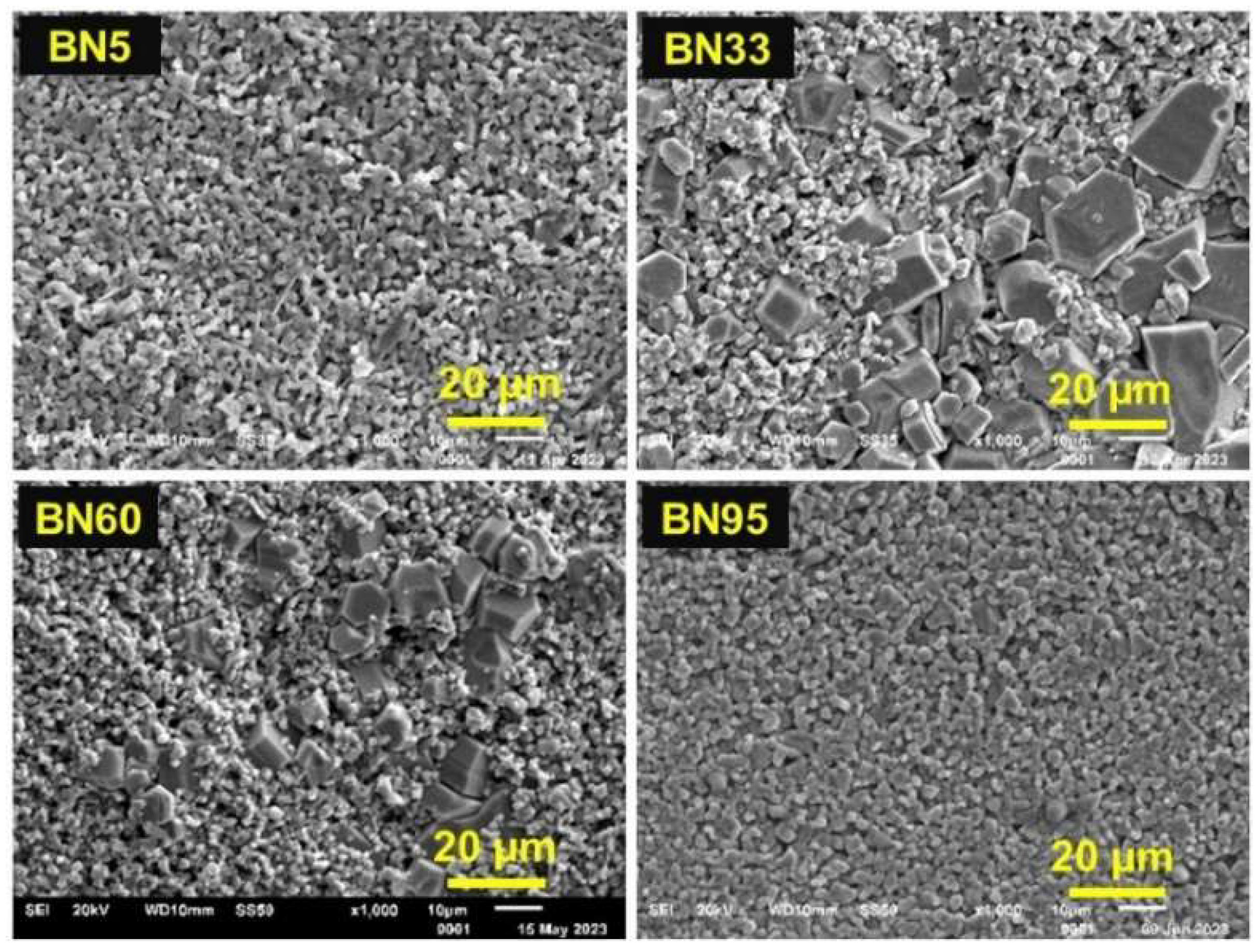

Representative SEM images for BNx (x=5, 33, 60 and 95) are shown in

Figure 2. The gradual increase in the grain size in the BN composites with increasing x (also in

Supplementary Figure S2) may indicate that NFO aids in the growth of hexagonal BaM grains for x≥9. Large grains are absent in BN5, but a closer examination of the surface morphology shows hexagonal-like features with grain size <2 μm. With increasing NFO content grains with size larger than 5 μm are present. For x > 41, the number of large grains reduces again. For the highest content of NFO (BN95) we observe similar grain distribution as pure NFO (

Supplementary Figure S2). BN5 also shows a similar grain distribution as pure BaM. Barium ferrite itself tends to form hexagonal grains [

20] and with a tweak in the synthesis process the particle shape can be made perfect spherical [

21]. In our case the processing has a large impact on the grain growth on these composites. The stabilization of the typical hexagonal BaM grains amongst NFO particles is worth noting.

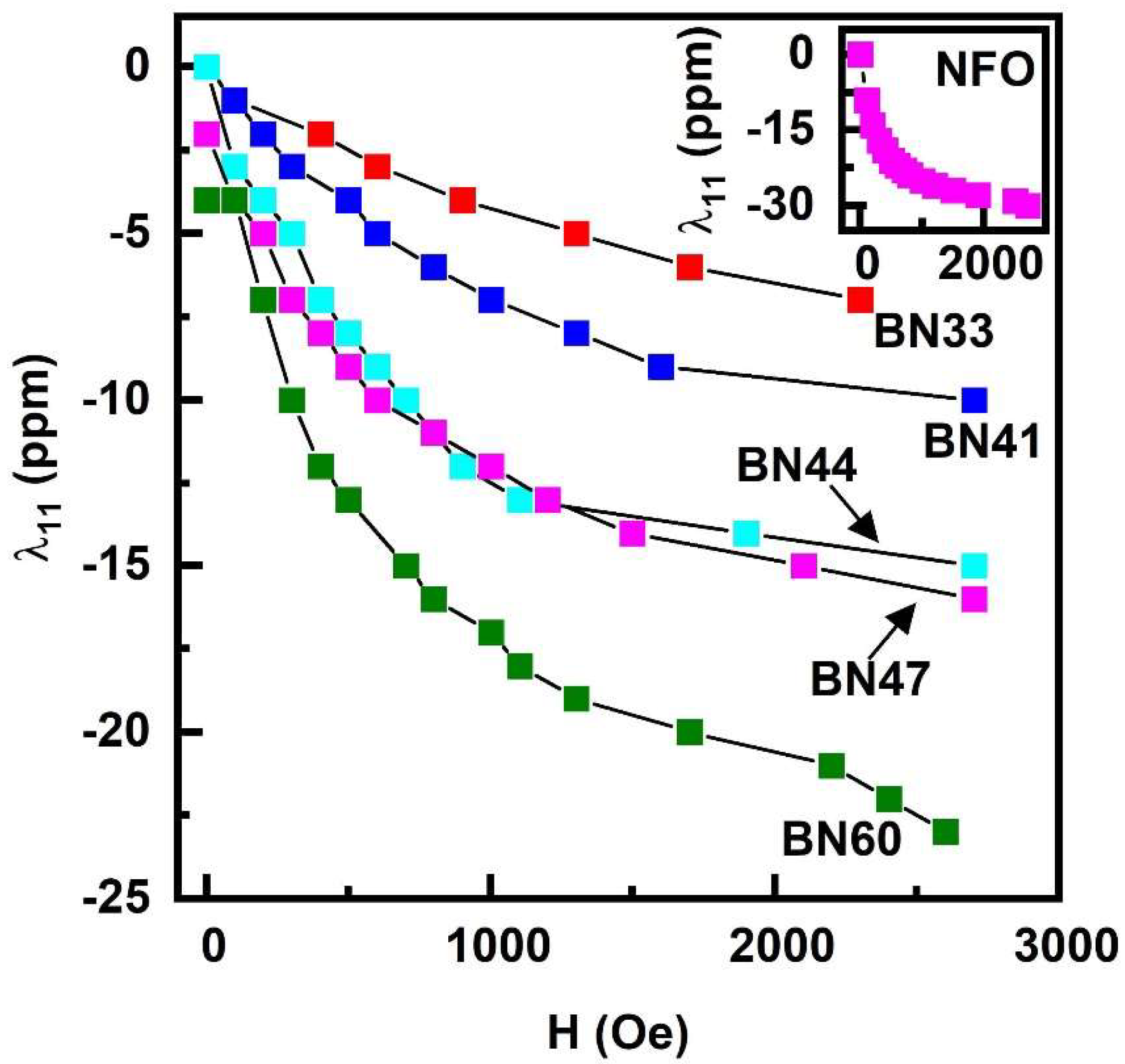

Since the magnetostriction λ is one of the key parameters that determine the strength ME interaction, we measured its value for the BNx composites. The measurements were done with a strain gage and a strain indicator and for H applied parallel to the sample plane. Data on the magnetostriction λ

11 measured parallel to H for the composites are shown in

Figure 3. The samples exhibit negative values for λ

11. The results are in accordance with the nature of magnetostrictive response of BaM and NFO [

22,

23]. With increase in the NFO content λ

11 increases and tends to show similar behaviour as pure NFO (shown in the inset of

Figure 3). The highest value of λ

11 ~ -23 ppm was measured for BN60 and we got similar values for x≥60. Our measurements on pure BaM showed λ

11=-1 ppm at 2.7 kOe. Hence it is clear that NFO phase is the major contributor towards the net magnetostriction of BN composites.

A key objective in this work is to achieve large enough H

A values in BNx to realize a strong zero-bias ME effects in a composite with PZT. Ferromagnetic resonance studies were carried out on the composites to determine H

A. Ferrite platelets, rectangular in shape, were placed in an S-shaped coplanar waveguide and excited with microwave power from a VNA. Profiles of the scattering matrix S

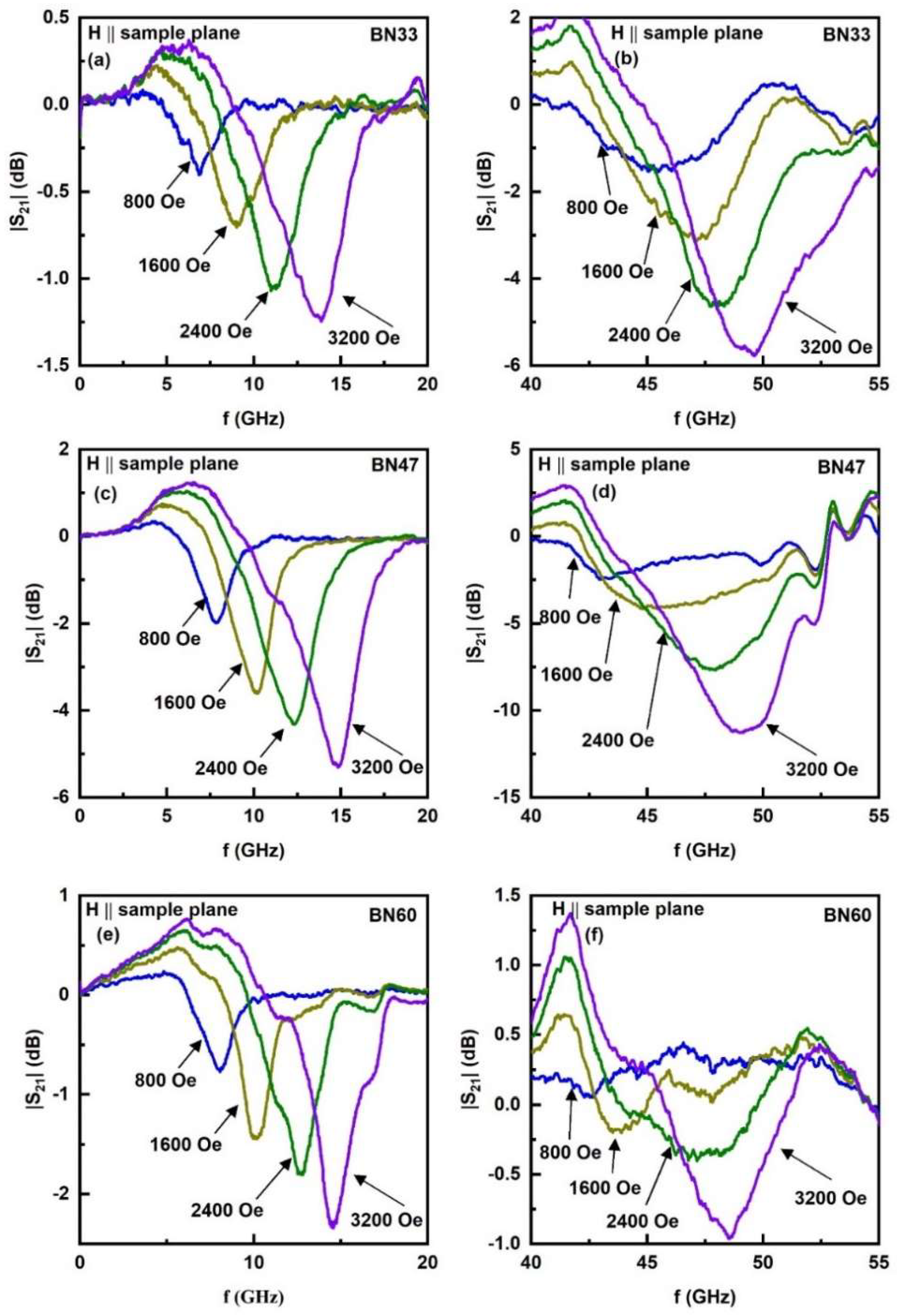

21 as a function of frequency f were recorded.

Figure 4 shows such profiles for a series of in-plane static magnetic field H along the sample length. For x values < 10, a single resonance mode was seen in the 50 GHz range (See

Supplementary Figure S3). With increasing NFO content two resonance modes were seen as in

Figure 4, one in the frequency range 3-20 GHz and another in the range 40-60 GHz. As discussed next, the resonance mode at the low frequency region in

Figure 4 is due to FMR in NFO whereas the higher frequency resonance is a magneto-dielectric mode in the composite [

24].

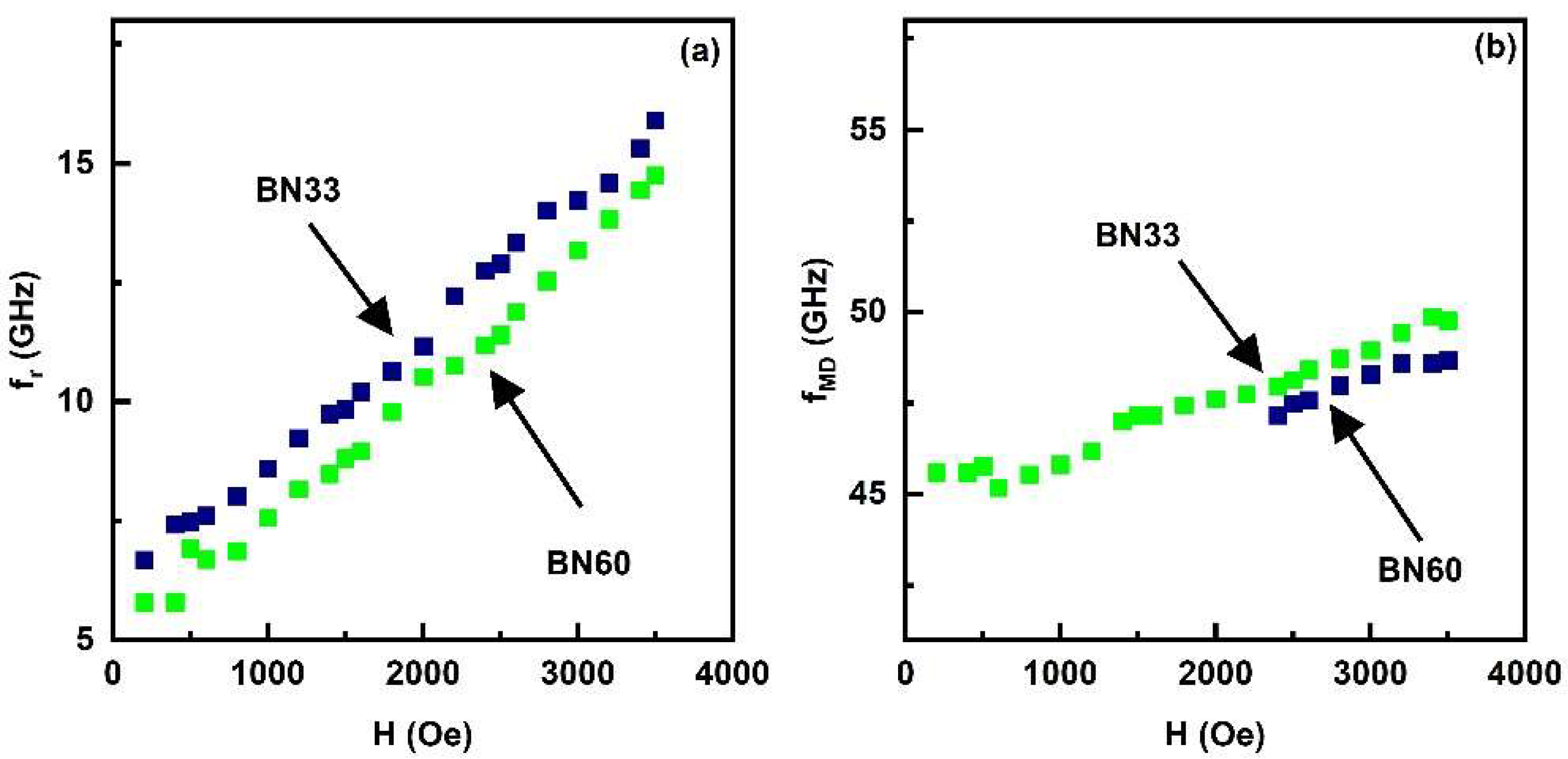

The H-dependence of the low- and high frequency mode frequencies f

r are shown in

Figure 5 (and in

Supplementary Figure S4). Data on f

r vs H for the low-frequency mode is shown in

Figure 5(a) for BN33 and BN60, with f

r increasing from 7.5 GHz at H= 1 kOe to 16 GHz for H=3.5 kOe for BN60 which amounts to an increase in f

r with H at the rate 3.4 GHz/kOe. A similar rapid increase in f

r with H is seen in

Figure 5(a) for BN33. From the rate of change in f

r with H one may associate this mode with FMR in NFO. Data in

Figure 5(b) on f

r vs H for the high frequency mode are for BN33 and BN60. This mode shows a linear variation in f

r with H with a rate of increase ~1.3 GHz/kOe. This slow variation in f

r with H is indicative of a magneto-dielectric mode in the composite platelet. This mode is not of importance for the current study and is considered for further analysis [

24].

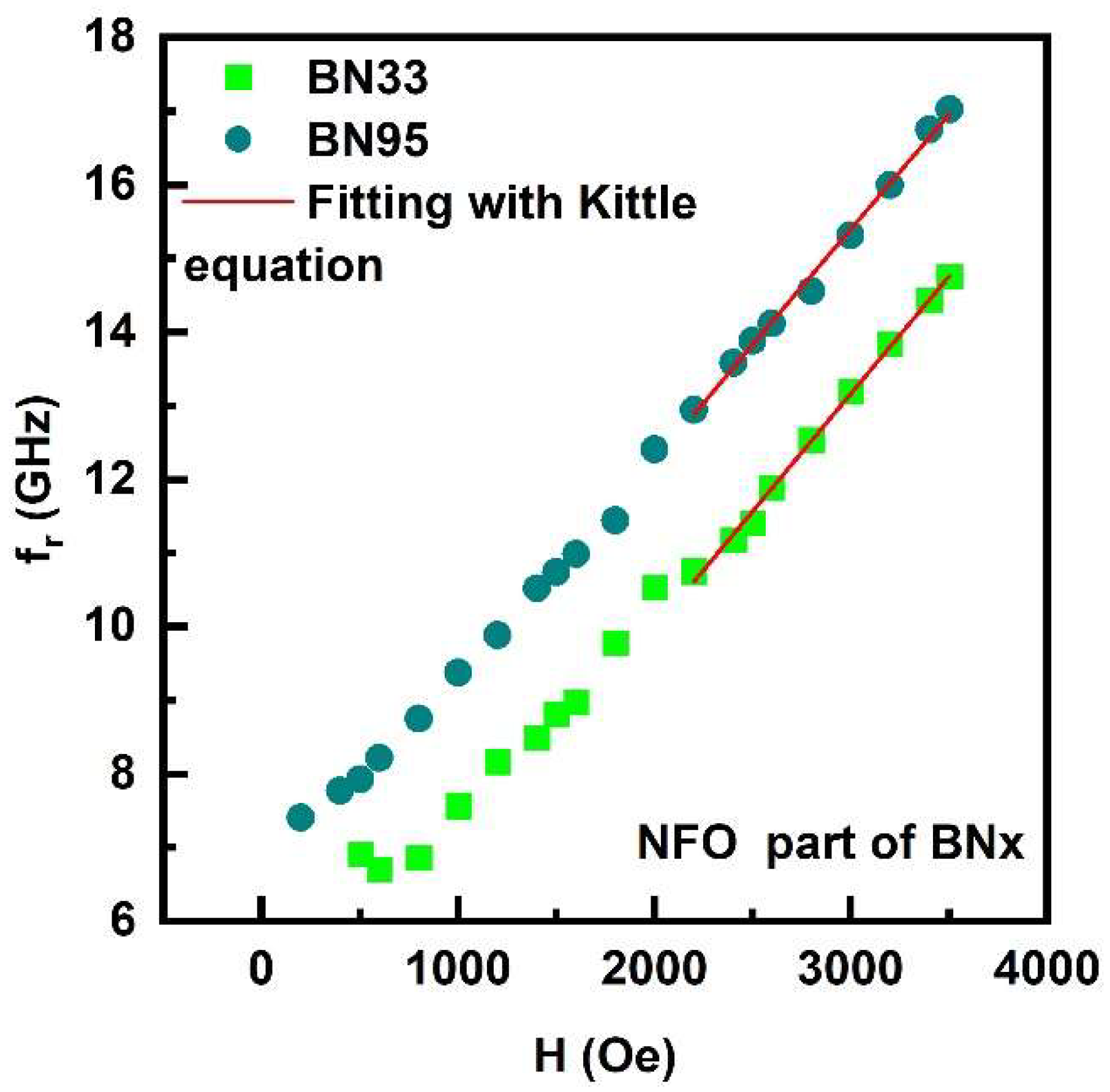

In order to estimate the built-in magnetic anisotropy field H

A in the composites, we first analysed the f

r vs H data for FMR as shown in

Figure 6 to determine the effective magnetization 4πM

eff= 4πM

s + H

A, where 4πM

s is the saturation magnetization. The Kittel equation for the FMR mode frequency is given by,

where, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, H is the in-plane external magnetic field along the x-direction, N

x, N

y and N

z are the demagnetization factors along the length, width and thickness of the platelet, respectively. The demagnetizing factors were calculated for the platelets used for FMR and the data as in

Figure 6 was fitted to Eq. (1) to determine 4πM

eff. Estimated values of the gyromagnetic ratio γ and 4πM

eff and measured 4πM

s are given in

Table 1. The values of γ range from 3.17 GHz/kOe for x = 33 to 2.98 GHz/kOe for x = 0.75 that are well within the range 3.20 GHz/kOe for pure NFO to 2.69 GHz/kOe for polycrystalline BaM [

25,

26]. The cause of low γ value for x = 75 needs to be investigated. Values of the anisotropy H

A estimated from FMR data are also given in

Table 1 for BNx composites with x = 33 – 95. The anisotropy field H

A is negative for x = 33 and 38, indicative of out-of-plane anisotropy for the polycrystalline composites. It is positive for higher x-values, increases from ~ 1 kOe for x=41 to ~ 12.39 kOe for x=75. Further increase in x results in a decrease in H

A. One may therefore infer from these H

A -values that a majority of BaM crystallites in x = 33 and 38 have out-of-plane orientation leading to a rather small perpendicular anisotropy for the sample. With increasing value of NFO content in x > 41, the higher concentration of NFO appears to promote the growth of BaM crystallites with in-plane orientation for the c-axis and a net in-plane anisotropy field that reaches a maximum value for x = 75. Several reported efforts in the past on FMR in polycrystalline BaM mainly dealt with textured BaM thin and thick films and showed, depending on the degree of texture, out-of-plane H

A -values in the range 4.5 to 15 kOe [

27,

28]. In this work, however, the composites show in-plane anisotropy field except for x = 33 and 38.

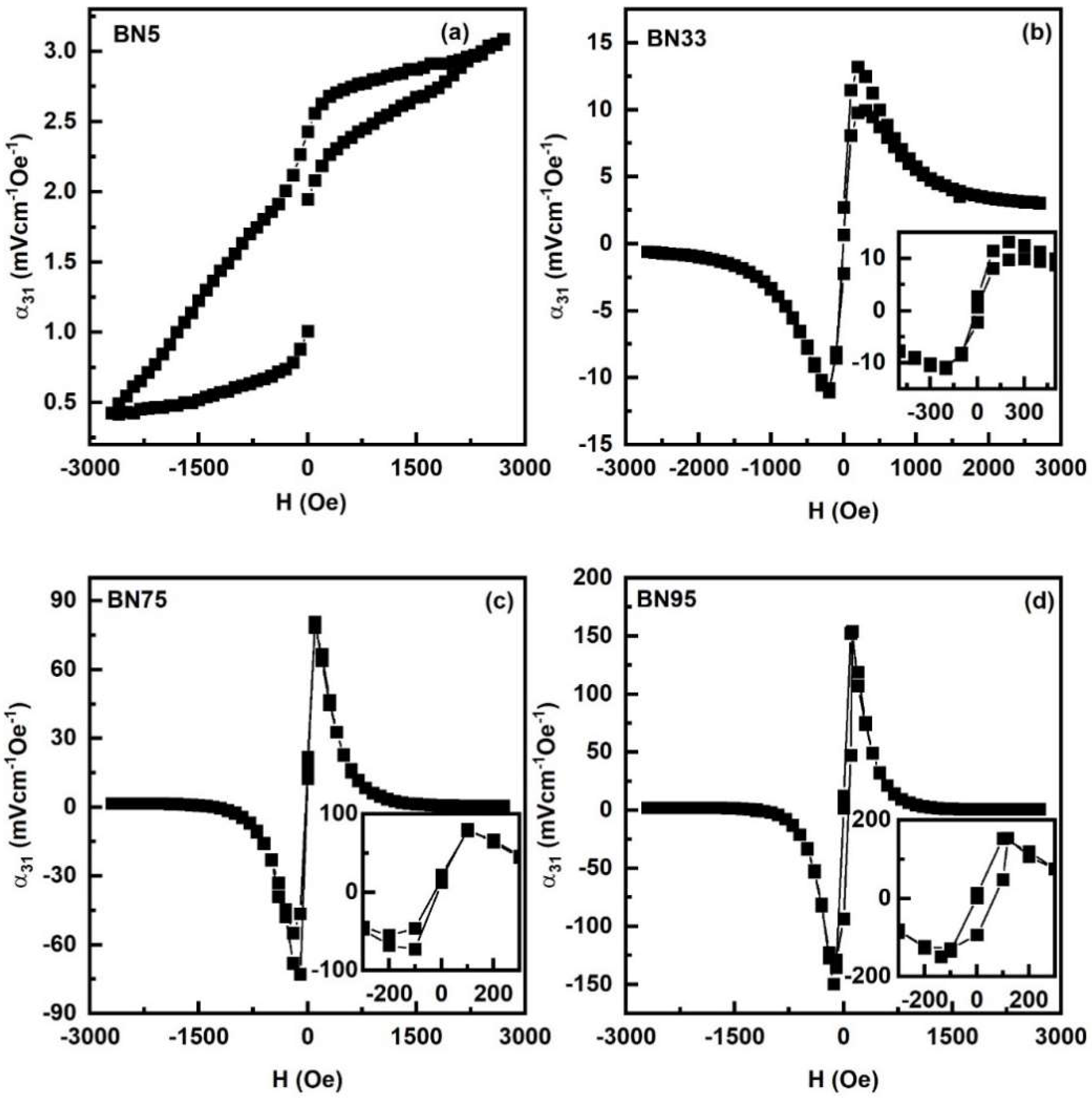

The strength of ME coupling was measured in bilayers of the composites and vendor supplied PZT (PZT850, American Piezo Ceramics, USA). Ferrite platelets of approximate lateral dimensions 5 mm × 10 mm and thickness t = 0.3 – 0.5 mm were bonded to PZT with 20 μm thick layer of a fast-dry epoxy. The ME voltage coefficient (MEVC) was measured for two different orientations of the applied magnetic fields: (i) α31 for the DC filed H and ac field h both parallel to each other and along the length of the sample and (ii) α33 for the magnetic fields applied perpendicular to the sample plane. The MEVC is given by α = V3/(h t), where V3 is the strain induced ac voltage measured across PZT. The ME coefficients were measured at low frequencies as well as at mechanical resonances in the bilayers.

The value of α

31 increases with increase in H to a maximum. The maximum value of MEVC for BN5 is rather small due to low q-value for this BaM rich composite. With further increase in the NFO content in the composites, α

31 increases to a maximum value of ~ 152 mV/cm Oe for BN95. Upon further increase in H, α

31 in general decreases to a minimum for composites with x > 5. Bias field H dependence of α

31 in

Figure 7 essentially tracks the variation in q with H, reaches a maximum at the maximum in the slope of λ

11 vs H, and drops to near zero when α

31 vs H (

Figure 3) shows saturation. Other significant features in the results from

Figure 7 are as follows. (i) When H is decreased from ~ 3 kOe back to zero a hysteresis in α

31 vs H is evident for all the BNx-PZT bilayers. (ii) Upon reversing the field H, a 180 deg phase shift (indicated by negative values for α

31) is observed in the ME voltage except for x=5. (iii) The bilayers show a finite remnant value for α

31 at zero-bias and, as discussed later, is attributed to the built-in bias in BNx provided by the anisotropy field H

A.

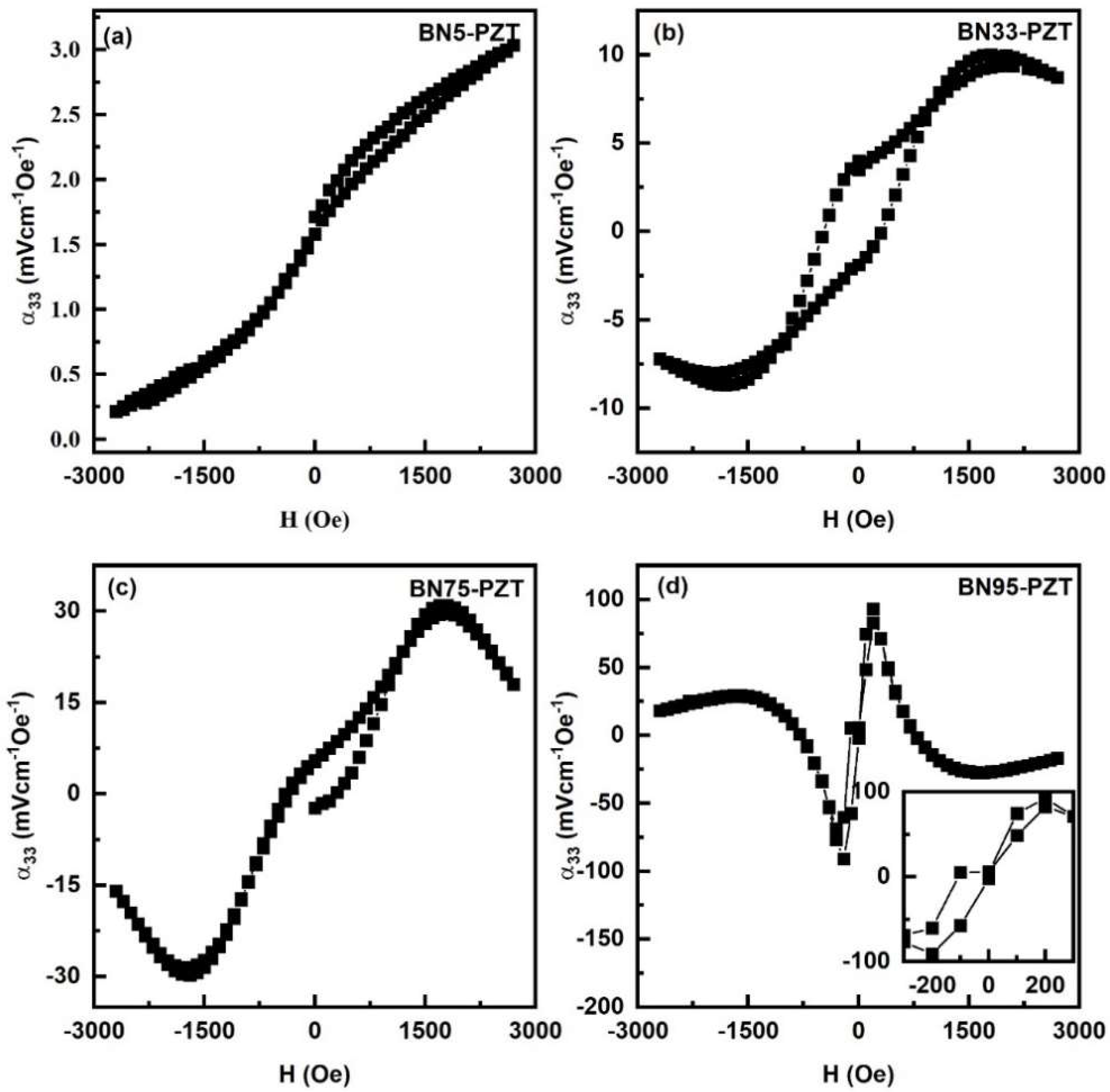

Figure 8 shows results of MEVC measurements for the magnetic fields applied perpendicular to the bilayers of BNx-PZT (also shown in the

supplement, Figure S5). The variation in MEVC has similar hysteresis and remnance as for the in-plane magnetic fields.

However, the following features in α

33 vs H differ from the dependence of MEVC for in-plane magnetic fields. (i) Overall MEVC values are smaller in

Figure 8 since demagnetization factors reduce both the dc and ac magnetic fields. (ii) the decrease in MEVC for H > 1.5 kOe is relatively small compared to α

31 vs H. (iii) Data in

Figure 8 for BN95-PZT bilayers shows a reversal in the sign of for H > 0.75 kOe for both positive and negative H.

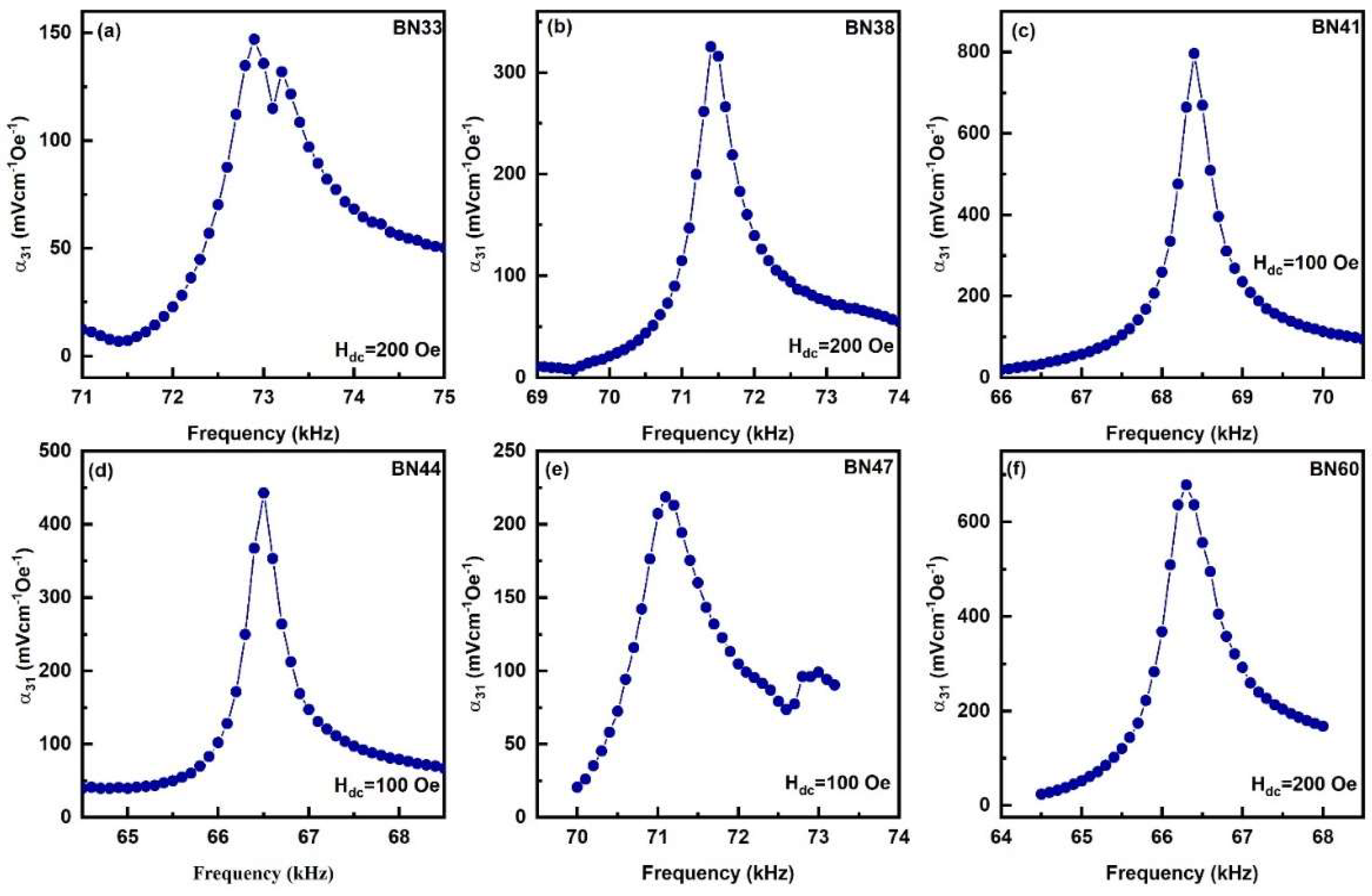

The strength of ME coupling in the bilayers was also characterized by measuring the frequency f dependence of the MEVC at mechanical resonance modes. Prior to these measurements we obtained the electromechanical resonance (EMR) frequencies (f

r) for the composites by measuring the frequency dependence of the impedance with an LCR meter. Mode frequencies could not be obtained for BNx for x≤19, but we were able to determine the frequency of longitudinal resonance modes for higher x-values. MEVC α

31vs f under a bias field H =100 – 200 Oe for the bilayers are shown in

Figure 9. One observes an increase in α

31 with increasing f and a sharp peak in its value at f

r ~ 66 – 73 kHz. We were able to identify f

r with the longitudinal EMR mode from the known composite dimensions. For x=33 the figure shows a fine structure with a double peak in the α

31vs f profile with values of 147 mV/cm Oe at 72.9 kHz and 132 mV/cm Oe at 73.2 kHz. Bilayers of BNx-PZT with x>33 have a single peak in the profiles and BN41-PZT shows the highest value of α

31=797 mVcm

-1Oe

-1 at 68.4 kHz. One observes a significant enhancement in the ME coefficients at f

r compared to values at 100 Hz (

Figure 7), and for example, by a factor 36 for x=41. We discuss the results of these ME measurements in the following section.

4. Discussions

It is evident from the results of this study that (i) it is possible to synthesize composites of spinel and M-type hexagonal ferrites free of ferromagnetic impurity phases, (ii) the composites, depending on the amount of BaM, have a moderately high uniaxial anisotropy that switches from uniaxial in BaM-rich compositions to planar anisotropy as NFO content is increased, and (iii) the magnetostriction is quiet small for BaM rich composites, but increases significantly with increasing NFO content although the piezomagnetic coefficient q is rather small in all of the composites due to slow increase in λ with H compared to pure NFO.

It is clear from the results of ME measurements in

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 that the bilayers of BNx and PZT show MEVC that are much higher than reported values for M-type hexaferrite-PZT bilayers [

29], but smaller than for NFO-PZT [

30]. Under optimum value of H, the highest MEVC are α

31 = 152 mV/cm Oe and α

33 = 90 mV/cm Oe, both for BN95-PZT. These values, however, are relatively small due to the weak piezomagnetic coupling strengths in BNx compared to nickel ferrite or nickel zinc ferrite based layered composites with PZT [

30,

31].

A key and primary objective of this work was to synthesize a ferromagnetic oxide with a moderately large H

A and high magnetostriction and piezomagnetic coupling for use with PZT to achieve ME coupling in the absence of an external bias magnetic field. It is worth noting that this goal was indeed accomplished. Bilayers of BNx-PZT used in this study do show a zero-bias MEVC (

Figure S6 in the supplement). Bilayer of BN75-PZT shows the highest α

31=22 mV/cm Oe at zero bias and BN85-PZT bilayer shows highest α

33=9 mV/cm Oe at zero bias. Strategies employed in the past to realize zero-bias ME effects included the use of an external stimuli or a ferromagnetic layer graded either in magnetization or in composition, etc [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The use of an easy to synthesize composite of a spinel ferrite and hexaferrite in this work for zero-bias ME effect makes this method more viable than others. There are reports wherein composites consisting of NFO and PZT show large ME coefficient of 460 mV/cm Oe for bilayers and 1500 mV/cm Oe for multilayers [

32]. The MEVC at resonance in these systems was as high as 1 V/cm Oe [

33]. Modified NFO and PZT multilayers even showed a higher ME coefficient [

34]. But there is hardly any evidence for ME coupling zero-bias effect in these composites [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Due to very low magnetostriction BaM is not suitable for strong direct ME coupling, but the very high uniaxial anisotropic field in the system is utilized in this work. Even though BaM grains in our BNx composites are expected to be completely randomized leading to a net zero the anisotropic field, the increase in the NFO content in BNx seems to promote the growth BaM grains with in-plane c-axis and a net in-plane anisotropy field.

Finally, we compare the zero-bias MEVC values with results reported in the past. Use of a nickel zinc ferrite graded either in magnetization or composition in a bilayer with PZT resulted in a zero-bias MEVC of 37 mV/cm Oe. Electric field induced bending vibration mode generated zero-bias ME effect in lead free system show a MEVC ~30 mV/cm

-Oe [

9]. Low field hysteresis based zero-bias effect also showed a value of ~60 mV/cm

- Oe

- [

16]. In our work we have obtained zero-bias ME coefficient ~22 mV/cm

-Oe

- for BN75-PZT bilayer which is comparable to the earlier report [

10]. The zero-bias ME response in our study could be improved with the use of composites of NFO and M-type strontium ferrite (SrM) or Al substituted SrM or BaM with higher λ than pure BaM. Aluminum substituted BaM or SrM may be good choices as they also have anisotropic fields as high as ~33kG [

35].