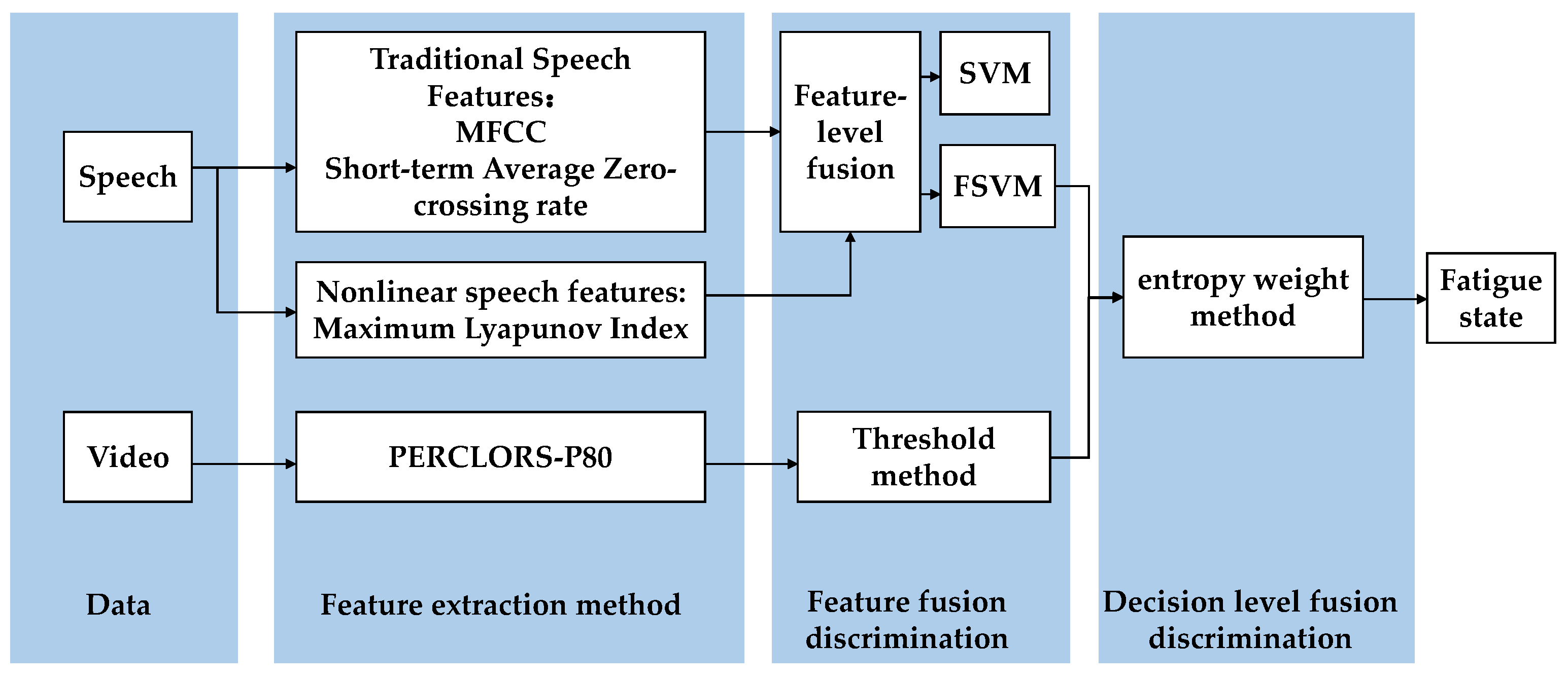

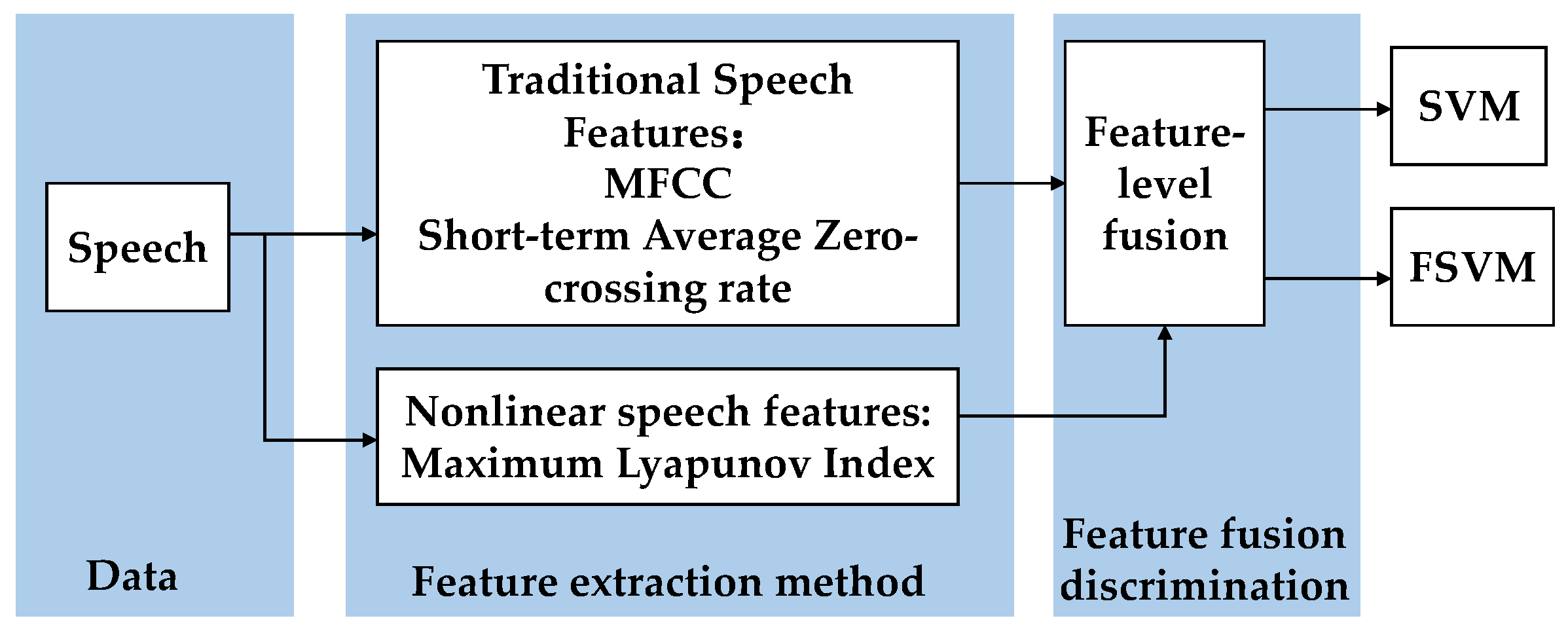

In the field of speech processing recognition, there are currently various speech features. We can divide them into three categories: spectral features, statistical features, and nonlinear features. We choose one from each category so that our data fusion can depict speech from three different perspectives. Here we extract the Mel frequency cepstral coefficient (MFCC), short-time-average zero-crossing rate, and maximum Lyapunov index. Based on the percentage of eyelid closure over time (PERCLOS) as eye features, feature fusion was applied to the features of the two types of data sources, and an evaluation index system was established.

2.1. Speech feature classification algorithm based on the FSVM

In fatigue detection, because the fuzzy samples in the feature space often lead to reduction of the classification interval and affect the classification performance of the classifier [

16]. In practical applications, training samples are often affected by some noise. This noise may have adverse effects on the decision boundary of SVM, leading to a decrease in accuracy. To solve this problem, this paper introduces the idea of a fuzzy system and combines it with an FSVM algorithm.

The membership function is first introduced. The algorithm principle of the FVSM is to add a membership function

to original sample set

so as to change the sample set to

. Membership function

refers to the probability that the

th sample belongs to the

category; this is referred to as the reliability, where

, and a larger

indicates a higher reliability. After introducing the membership function, the SVM formula can be expressed as

Original relaxation variable

is replaced by

since the original error description of the sample does not meet the conditions for the relaxation variable presented in the form of the weighted error term of

. Reducing the membership degree of sample

weakens the influence of error term

on the objective function. Therefore, when locating the optimal segmentation surface,

can be regarded as a secondary (or even negligible) sample feature, which can exert a strong inhibitory effect on isolated samples in the middle zone, and yield a relatively good optimization effect on the establishment of the optimal classification surface. The quadratic programming form of formula (1) is dually transformed to

In this formula, the constraint condition is changed from to , and the weight coefficient is added to penalty coefficient . For samples with different membership degrees, the added penalty coefficients are also different: indicates the ordinary SVM, while when sample becomes too small, and its contribution to the optimal classification plane will also become smaller.

In optimal solution

, the support vector is the nonzero solution of

. After introducing the membership function,

is divided into two parts: (1) the effective support vector distributed on the hyperplane; that is, the sample corresponding to

, which meets the constraint condition; and (2) the isolated sample that needs to be discarded according to the rule; that is, the sample corresponding to

. Therefore, the classification ability of each SVM is tested by the membership function, and finally the decision model of FSVM is obtained through training as follows:

where

The sample membership function has a large impact on the classification effect of FSVM, and so selecting an appropriate sample membership function is an important step in the design of the FSVM. The commonly used membership functions include the linear membership function, S-type membership function, type membership function [

17].

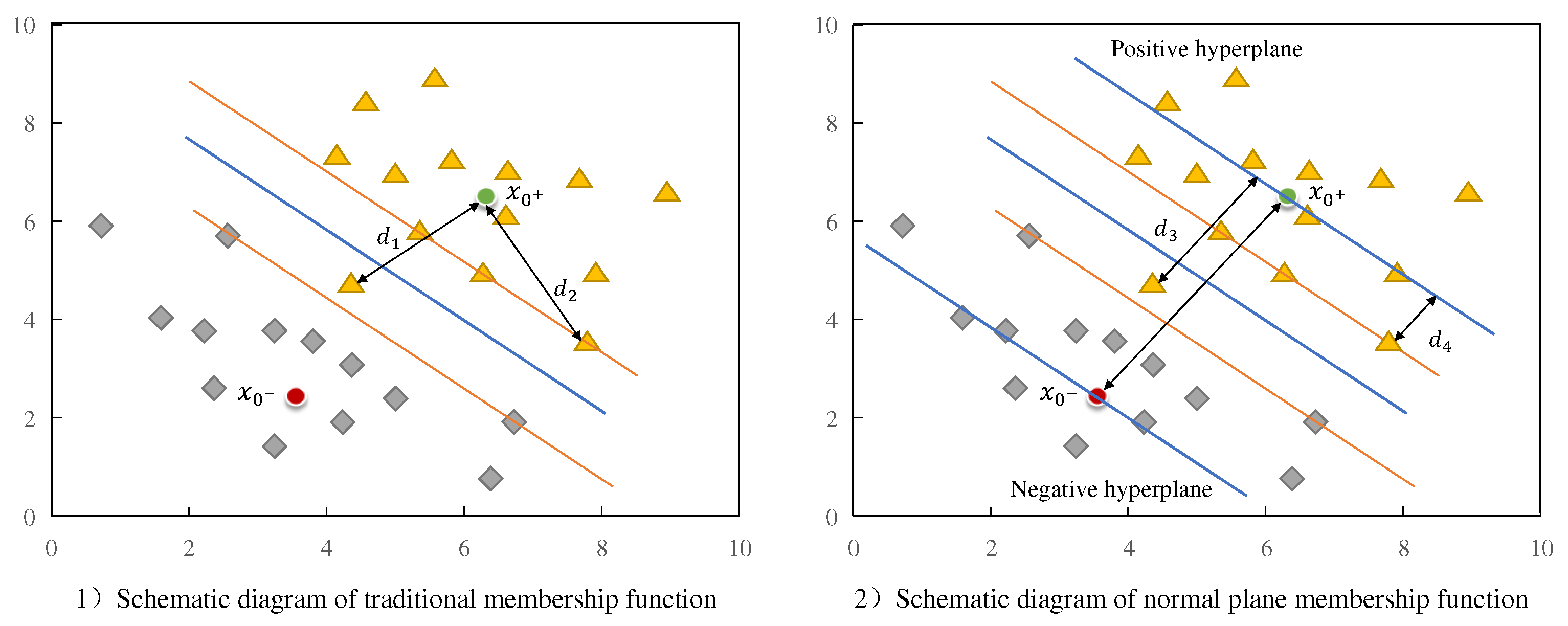

However, the traditional membership function (see

Figure 2.2) usually only considers the distance between the sample and the center point. Therefore, when there are isolated samples or noise points close to the center point, they will be incorrectly assigned a higher membership.

As shown in

Figure 2a, in the triangle samples of the positive class, distance

between the isolated sample and the sample center is basically the same as distance

between the support sample and the sample center, and so the two samples will be given the same membership value, which will adversely affect the determination of the optimal classification plane.

In order to avoid the above situation, a membership function of the normal plane is proposed, which involves connecting the center points of positive and negative samples to determine the normal plane, and synchronously determining the hyperplane of the sample attribute. In this approach the sample membership is no longer determined by the distance between the sample and the center point, but by the distance from the sample to the attribute hyperplane. As shown in

Figure 2b, the distance between the isolated sample and the sample center becomes

, and the distance between the supporting sample and the sample center becomes

, which is better at eliminating the influence of isolated samples.

In the specific calculation, first set the central point of positive and negative samples as

and

, respectively, and

and

as the number of positive and negative samples, and calculate their center coordinates according to the mean value:

is the vector connecting the centers of the two samples, and normal vector

is obtained by transposing

. Then the hyperplane to which the two samples belong is

Then the distance from any sample

to its category hyperplane is

If the maximum distance between positive samples and the hyperplane is set to

, and the maximum distance between negative samples and the hyperplane is set to

, then the membership of various inputs is

where

takes a small positive value to satisfy

.

In the case of nonlinear classification, kernel function

is also used to map the sample space to the high-dimensional space. According to mapping relationship

, the center points of the positive and negative samples become

The distances from the input sample to the hyperplane can then be expressed as

This formula can be calculated using inner product function

in the original space rather than

. Then, the distance of positive sample

from the positive hyperplane is

Similarly, the distance of negative sample

from the negative hyperplane is

Through formula (10) and formula (11), we can use formula (7) to obtain the membership degree in the case of nonlinearity.

2.2. Eye-fatigue feature extraction algorithm based on PERCLOS

This section describes eye feature extraction. PERCLOS refers to the proportion of time that the eye is closed, and is widely used as an effective evaluation parameter in the field of fatigue discrimination. P80 in PERCLOS, which corresponds to the pupil being covered by more than 80% of the eyelid, was the best parameter for fatigue detection, and so we selected this as the judgment standard for eye fatigue[

18].

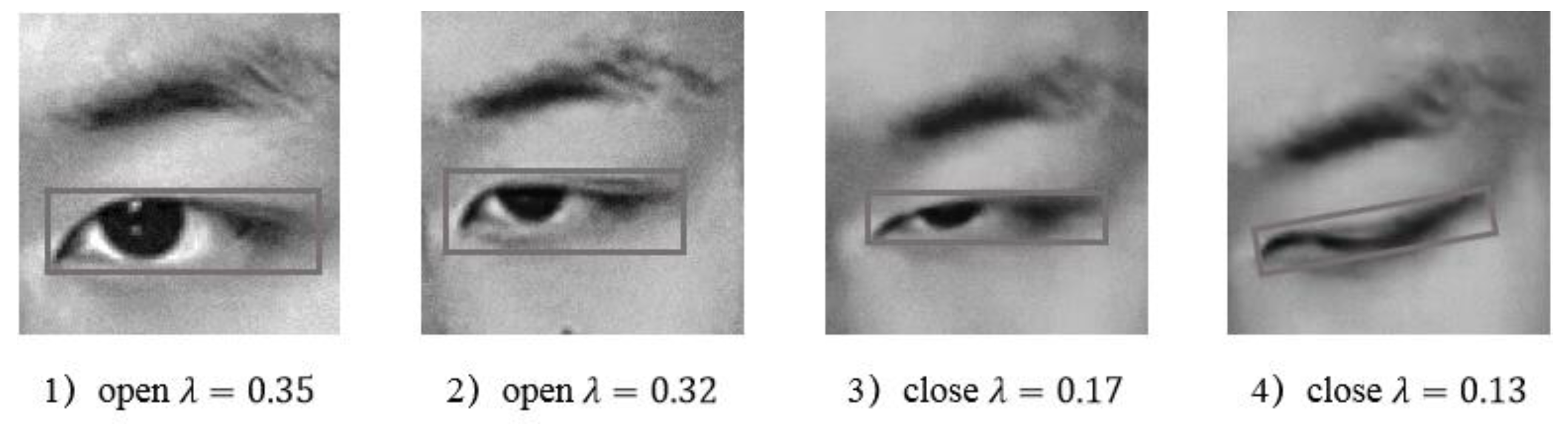

Before extracting PERCLOS, we first need to identify the closed state of the eyes. This is addressed here by analyzing the aspect ratio of the eyes.

Figure 3 shows images of a human eye in different states. When the eye is fully closed, the eye height is 0 and aspect ratio

is the smallest. Conversely,

is largest when the eye is fully open.

We calculate the PERCLOS value by applying the following steps:

1. Histogram equalization

Histogram equalization of an eye image involves adjusting the grayscale used to display the image so as to increase the contrast between the eye, eyebrow, and skin color areas and thereby make these structures more distinct, which will improve the extraction accuracy of the aspect ratio [

19].

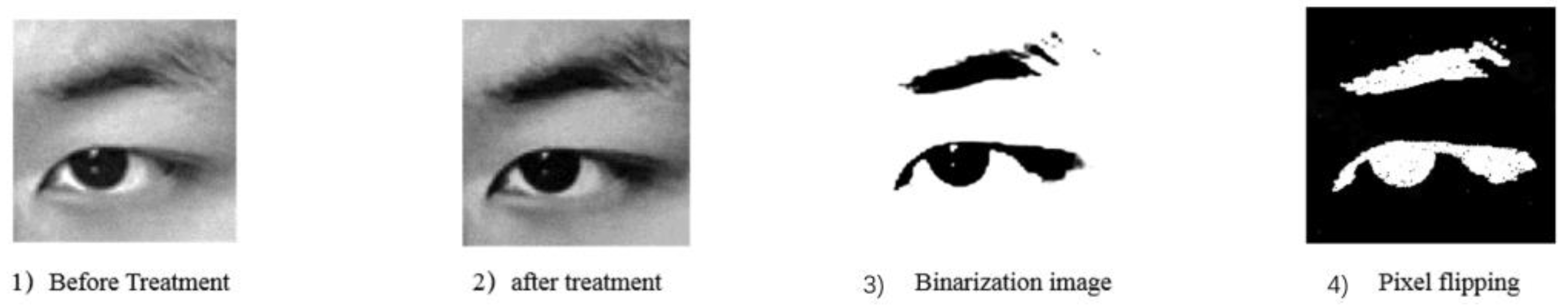

Figure 2.4a and b show images before and after histogram equalization processing, respectively.

2. Image binarization

Considering the color differences in various parts of the eye image, it is possible to set a grayscale threshold to binarize each part of the image [

20]. Through experiments, it was concluded that the processing effect was optimal when the grayscale threshold was between 115 and 127, and so the threshold was set to 121.

Figure 2.4c shows the binarized image of the eye, and the negative image in

Figure 2.4d is used for further data processing since the target area is the eye.

Figure 4.

Eye image processing: 1) before histogram equalization,2) after histogram equalization, 3) after binarization, and 4) the negative binarized image.

Figure 4.

Eye image processing: 1) before histogram equalization,2) after histogram equalization, 3) after binarization, and 4) the negative binarized image.

3. Calculate eye aspect ratio

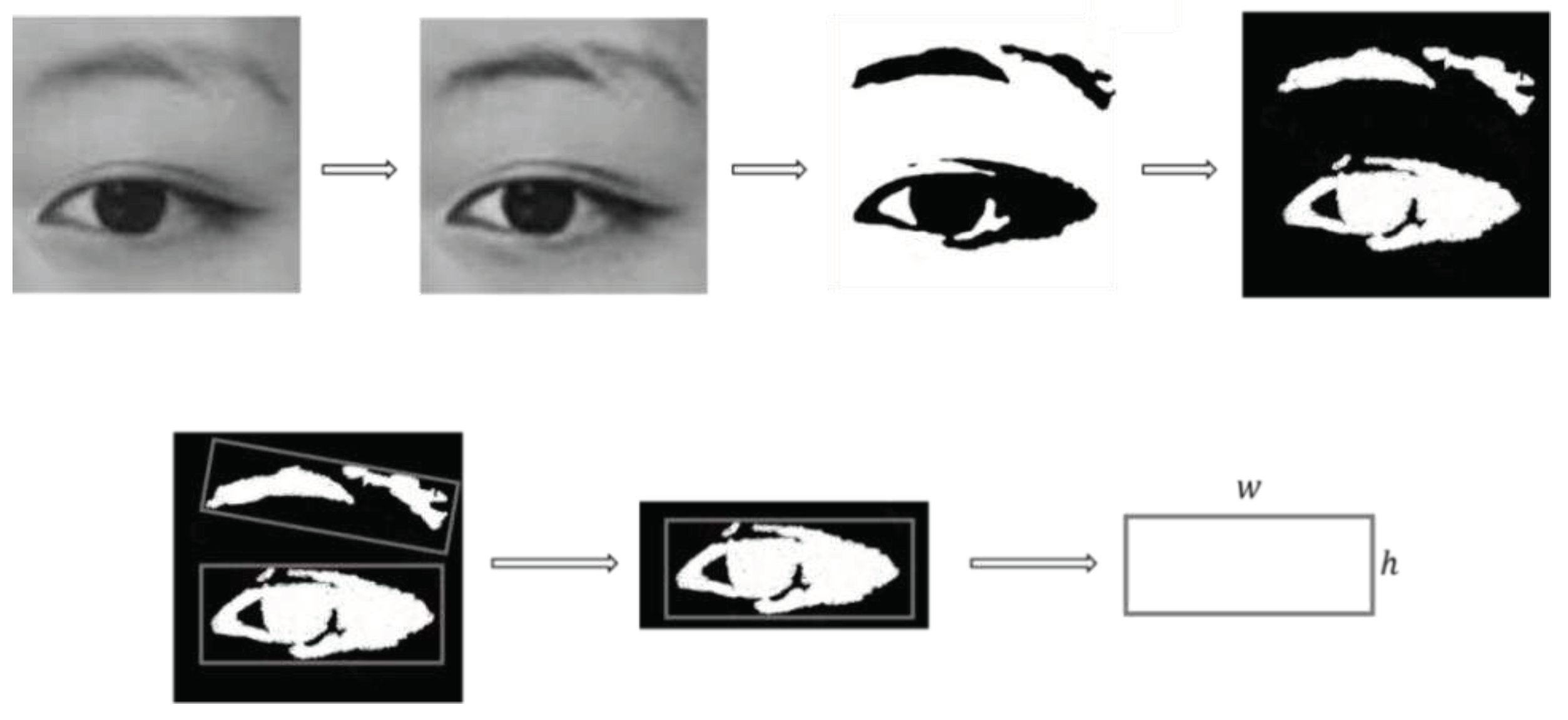

Determining the minimum bounding rectangle for the binary image as shown in

Figure 5 yields two rectangles of the eyebrow and eye. The lower one is the circumscribed rectangle of the eye, and the height and width of the rectangle correspond to the height and width of the eye.

Height

and width

of the rectangle are obtained by calculating the pixel positions of the four vertices of the rectangle, with the height-to-width ratio of the eye is calculated as

. P80 was selected as our fatigue criterion, and so when the pupil is covered by more than 80% of the eyelid, we consider this to indicate fatigue. The height-to-width-ratio statistics for a large number of human eye images were used to calculate the

values of eyes in different states. We defined

.23 as a closed-eye state, and

as an open-eye state [

21].

Figure 2.6 shows the aspect ratio of the eye for different closure states.

4. Calculate the PERCLOS value

The principle for calculating the PERCLOS value based on P80 is as follows: assuming that an eye blink lasts for

, where the eyes are open at moments

and

, and the time when the eyelid covers the pupil for more than 80% is

, then the value of PERCLOS is

Considering that the experiments involved analyzing eye-video data, continuous images can be obtained after frame extraction, and so the timescale can be replaced by

fps = 30 with fixed image frames; that is, by analyzing the video of the controller’s control eye over a certain period of time, the total number of images collected in the data is

, and the number of closed eyes is

, then the value of PERCLOS is

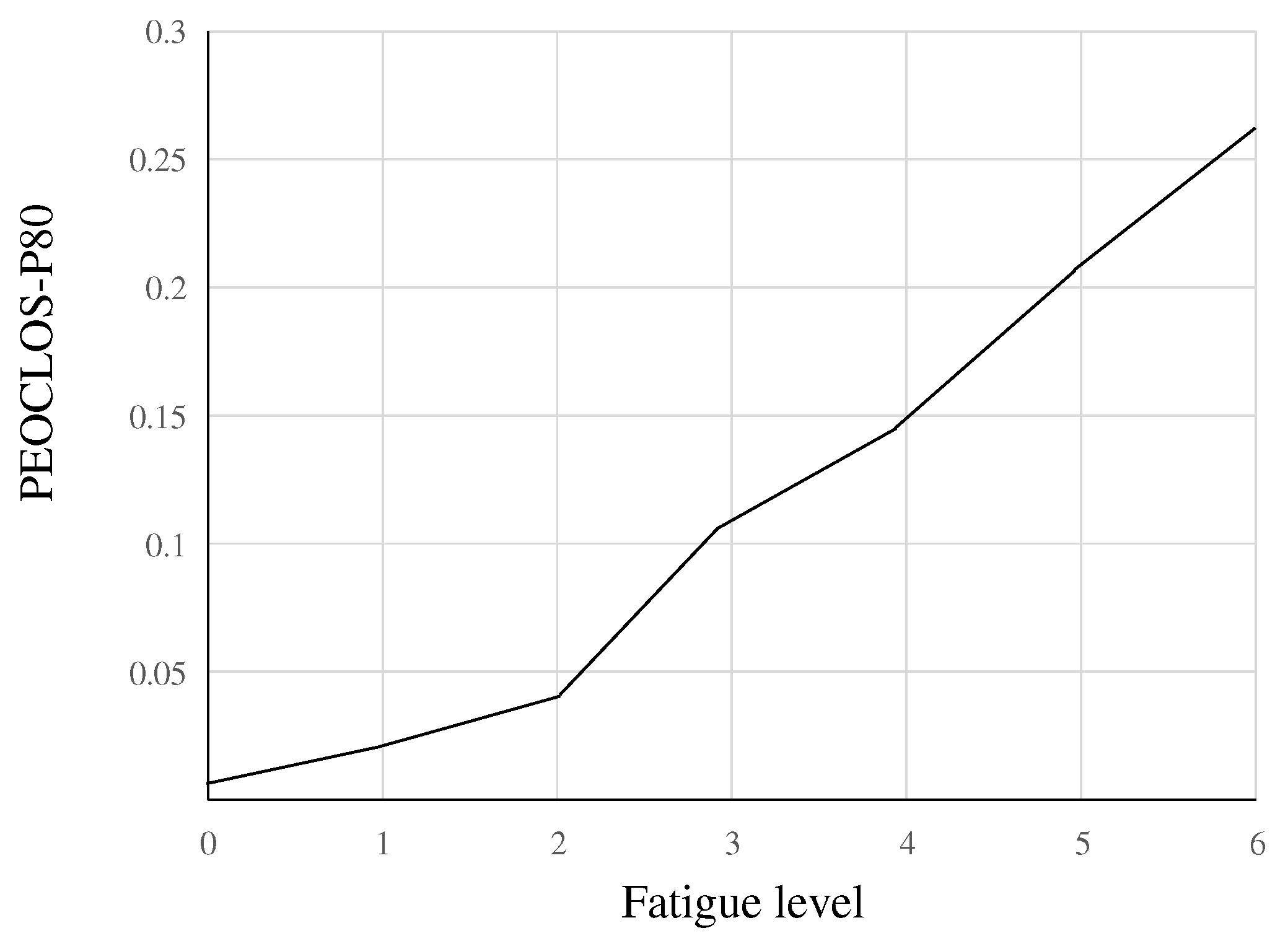

Figure 7 shows that the PERCLOS value (for P80) is positively correlated with the degree of fatigue. Therefore, we can take the PERCLOS value of controllers as the indicator value of their eye fatigue, and quantitatively describe the fatigue state of controllers through PERCLOS (P80).

2.3. Decision-level fatigue-information fusion based on the entropy weight method

The concept of entropy is often used in information theory to characterize the degree of dispersion of a system. According to the theory of the entropy weight method, a higher information-entropy index indicates data with a smaller degree of dispersion, and the smaller the impact of the index on the overall evaluation, the lower the weight [

22]. According to this theory, the entropy weight method determines the weight according to the degree of discreteness of the data, and the calculation process is more objective. Therefore, the characteristics of information entropy are often used in comprehensive evaluations of multiple indicators to reasonably weight each indicator.

The main steps of the entropy weight method are as follows:

Normalization of indicators. Assuming that there are

samples and

indexes,

represents the value of the

th indicator(

) corresponding to the

th sample (

), then the normalized value

can be expressed as

where

and

represent the minimum and maximum values of the indicators, respectively.

2. Calculate the proportion of the th sample value under index :.

3. Calculate the entropy of index

. According to the definition of information entropy, the information entropy of a set of data values is

where, when

, the information entropy is

4. Calculate the weight of each indicator. After obtaining the information entropy of each index, the weight of each index can be calculated using the following formula: