Submitted:

17 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Cycle Time Variability in Offsite Construction Factories

1.2. Process Time Estimation Methods

1.3. Research Areas for Further Investigation

1.3.1. Cycle Time-Influencing Factors

1.3.2. The Need for Continuous System Tuning

1.3.3. Machine-learning algorithms employed

1.4. Study Aim, Objectives and Contribution

- (1)

- Examine the effect of considering a variety of influencing factors on the performance of cycle time-estimation models: Doing so helps to demonstrate the importance of expending time and effort on the identification and understanding of influencing factors prior to building prediction models.

- (2)

- Explore the reliability of using data collected automatically through computer vision to train the estimation models: The findings of this task can shed light on the extent to which we can rely on automatically acquired data for building estimation models.

- (3)

- Examine the use of different machine learning algorithms, including the feed-forward ANN, LR, and RF algorithms, for cycle time estimation considering various influencing factors: As discussed in the literature review section above, there is no consensus regarding the behaviour of these machine learning algorithms in the context of process time estimation applications in offsite construction. Therefore, there is merit to gaining a better understanding of how these models perform given various influencing factors in the context of such applications.

2. System Description and Architecture

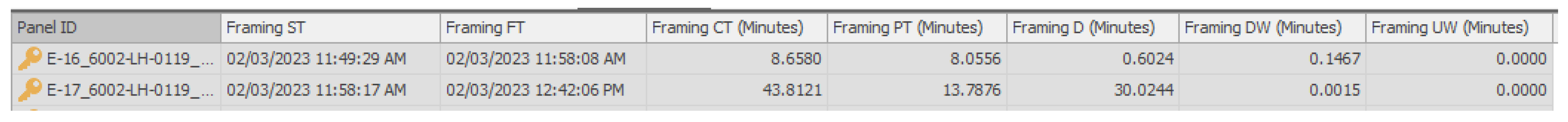

2.1. Process Time Variables

-

Cycle time (CT): CT refers to the total time spanning from the start of the process undertaken at a workstation for a given component until the end of the process, where a “cycle” refers to the set of tasks assigned to a workstation for a single component (e.g., one wall panel). CT is a function of two variables:

- ∘

- Processing time (PT): PT is the time spent by resources processing a component during a cycle at a workstation. Under ideal conditions, CT is equal to PT.

- ∘

-

Cycle delay (CD): CD is the time during which work is not performed on the component during a cycle at a workstation. In other words, it is the amount of time it takes a cycle to be completed beyond the expected completion time, which is PT. We can further differentiate between two types of delays: predictable cycle delays (PCD) and unpredictable cycle delays (UCD). PCD refers to interruptions to a cycle that can be anticipated and estimated to a certain extent. Examples of PCD include scheduled breaks, meetings, training sessions, predictable unavailability of resources, scheduled maintenance, and waiting for a slow material preparation process. UCD, on the other hand, arises from random events such as machine breakdowns, machine malfunctions, errors in shop drawings, power outages, worker injuries, phone calls, conversing with co-workers, and bathroom breaks.Given these definitions, CT is calculated satisfying Eq. (1).

-

Inter-cycle total delay (ITD): ITD is the total time spanning from the end of a cycle at a workstation to the start of the subsequent cycle. ITD is a function of the following variables:

- ∘

- Downstream-related waiting time (DW): DW is the time spent waiting for the completed component to be transferred to the downstream workstation. Specifically, it is the time spanning from the end of a process undertaken at a workstation to the time at which the component is transferred downstream. Various scenarios could result in DW. One such scenario is when the downstream workstation is busy and there is no inventory between the two workstations or there is inventory that is already at full capacity. Another example scenario that could result in DW is when the resources responsible for transferring the component between workstations are busy with other tasks. Although DW is not factored into the CT for a given cycle, it affects the start time of the subsequent cycle.

- ∘

- Upstream-related waiting time (UW): UW is the time spent waiting (after a completed component is transferred to the downstream workstation) for the upstream workstation to complete work before a new cycle can be started. This occurs when a given workstation is faster than the upstream workstation(s). Since it occurs before a new cycle is started, UW, like DW, is not factored into CT.

- ∘

-

Inter-cycle additional delay (ID): ID is the time by which the start of a new cycle is delayed beyond DW and UW due to any of the aforementioned reasons that cause CD. Note that the total duration of the related delay may be longer than ID, but it may overlap with DW and UW, which is why ID, as defined herein, specifically refers to the additional delay that exceeds the durations of DW and UW. Like CD, ID can arise from both predictable and random events, generally rendering it a random occurrence.Given these definitions, ITD is calculated satisfying Eq. (2).

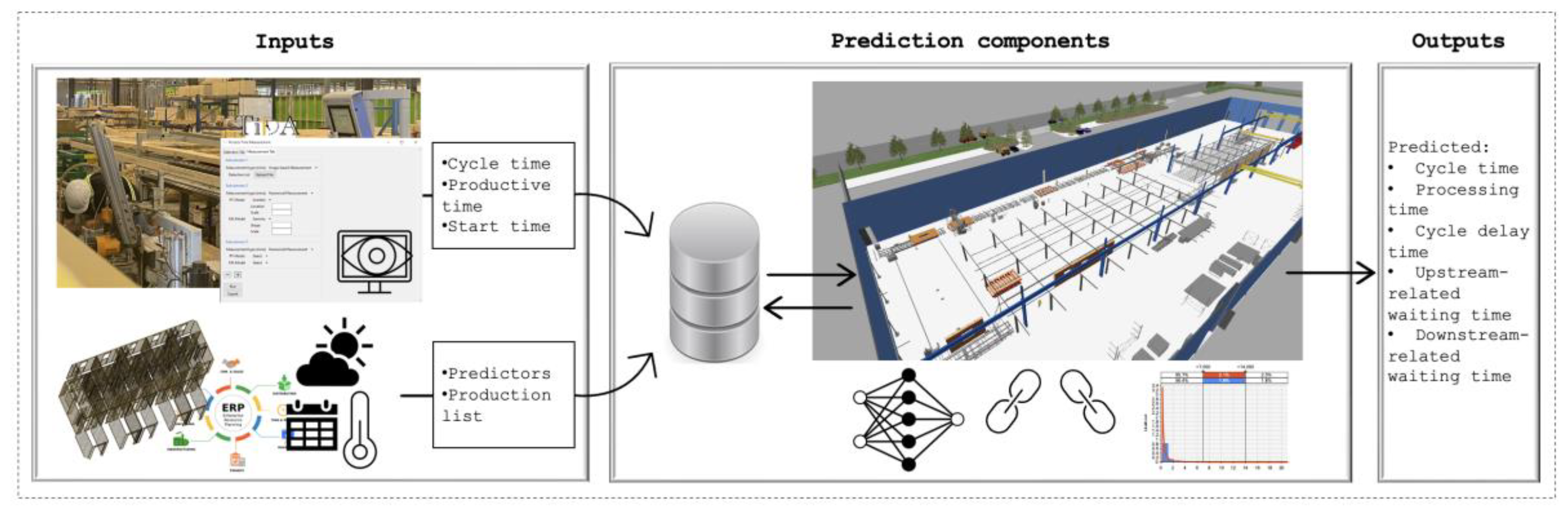

2.2. System Architecture and Components

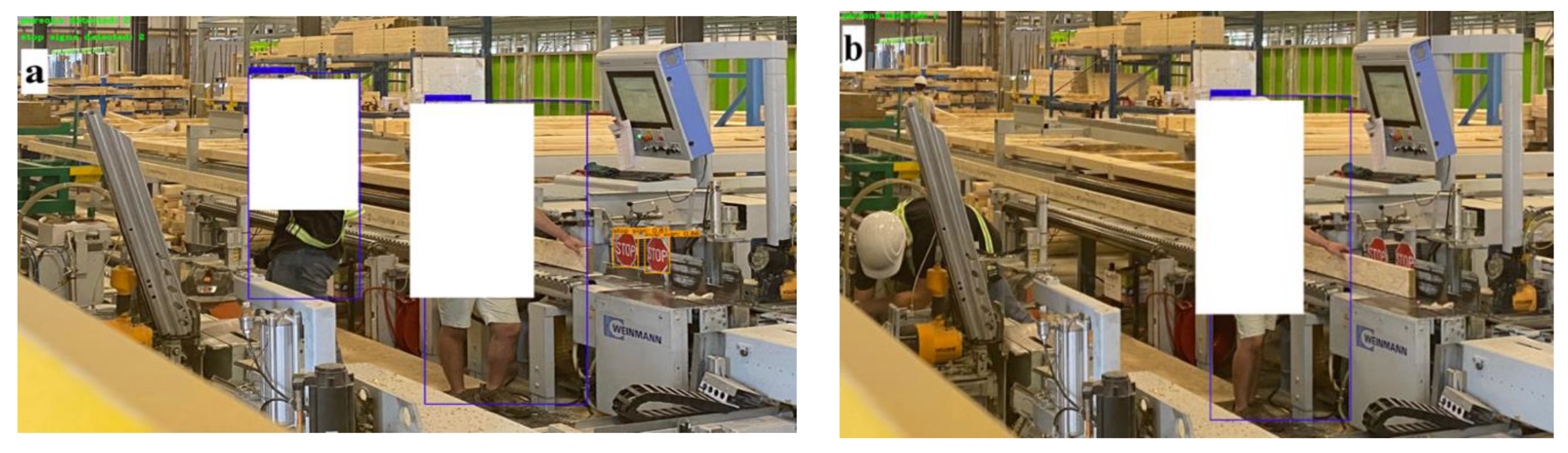

- A computer vision system for actual data collection at each workstation: As discussed above, various influencing factors contribute to CT variability in production factories. For this reason, the estimation system should be trained regularly in order to better capture the variability arising from various influencing factors, thus a continuous stream of data from the production factory is required. Therefore, the estimation system uses the computer vision-based time data acquisition system developed in a previous work [2] for automated data acquisition. The system automatically acquires data on the cycle start time, productive time (i.e., the time actually spent by resources working on a component at a workstation—equivalent to PT in the context of this study), and CT for each component processed for a given operation at a workstation.

- A prediction model for PT at each workstation: PT is predictable to a certain degree when the factors that influence its value for a given component at a workstation are known. The degree of predictability, however, may fluctuate at the workstation across different time frames. This is because most of the operations in offsite construction factories are still labour based. Labour-based tasks, even if they are well-defined and standardized, are still subject to high variability because of the inconsistency of human productivity. In fact, PT can even vary for the exact same task depending on the worker’s physical health, mental health, work environment, motivation, and other factors influencing their pace of work. Due to this variability, PT prediction can be highly complex at certain workstations. Nevertheless, machine-learning models can be leveraged to model such complexity. As such, the system developed in the present study uses machine-learning models to predict PT as a function of influencing factors at workstations.

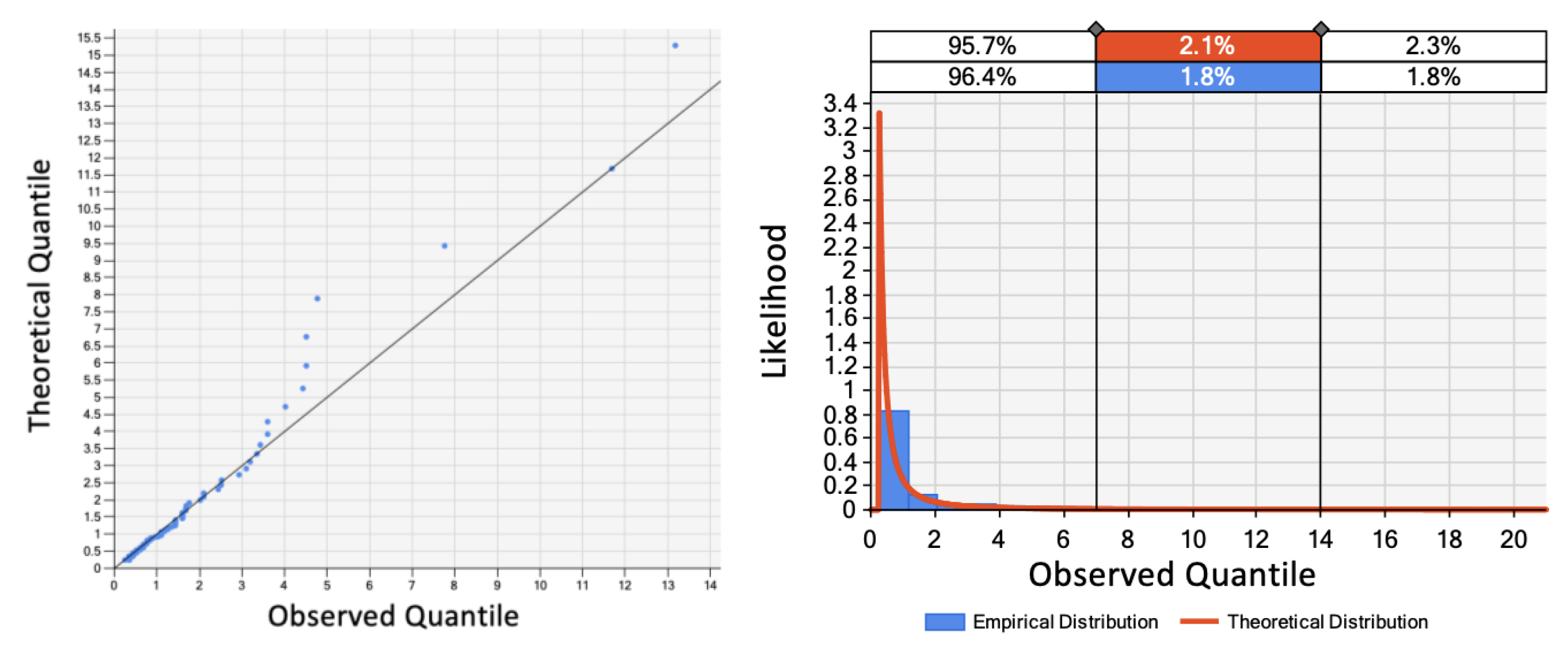

- Estimation models for UCD and ID at each workstation: Given the random nature of the events causing UCD and ID, probability distributions were used to model these variables.

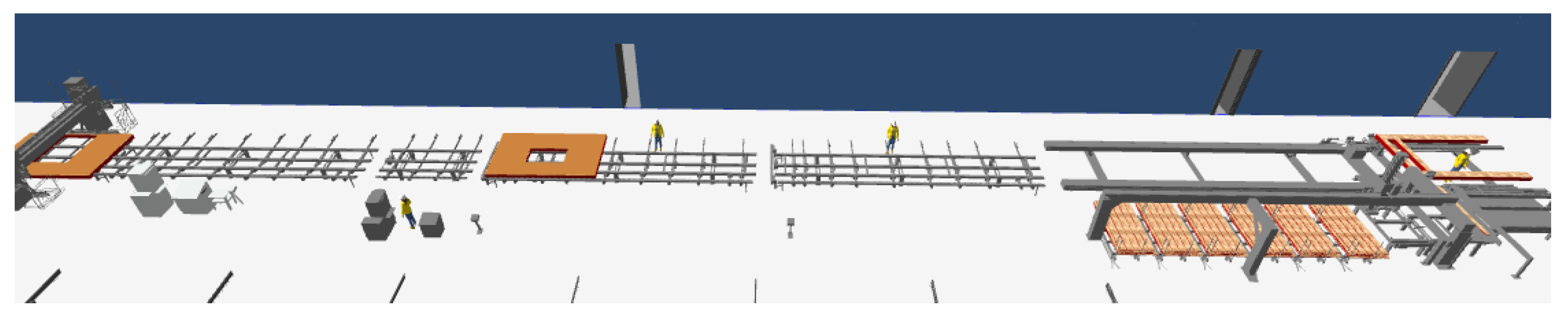

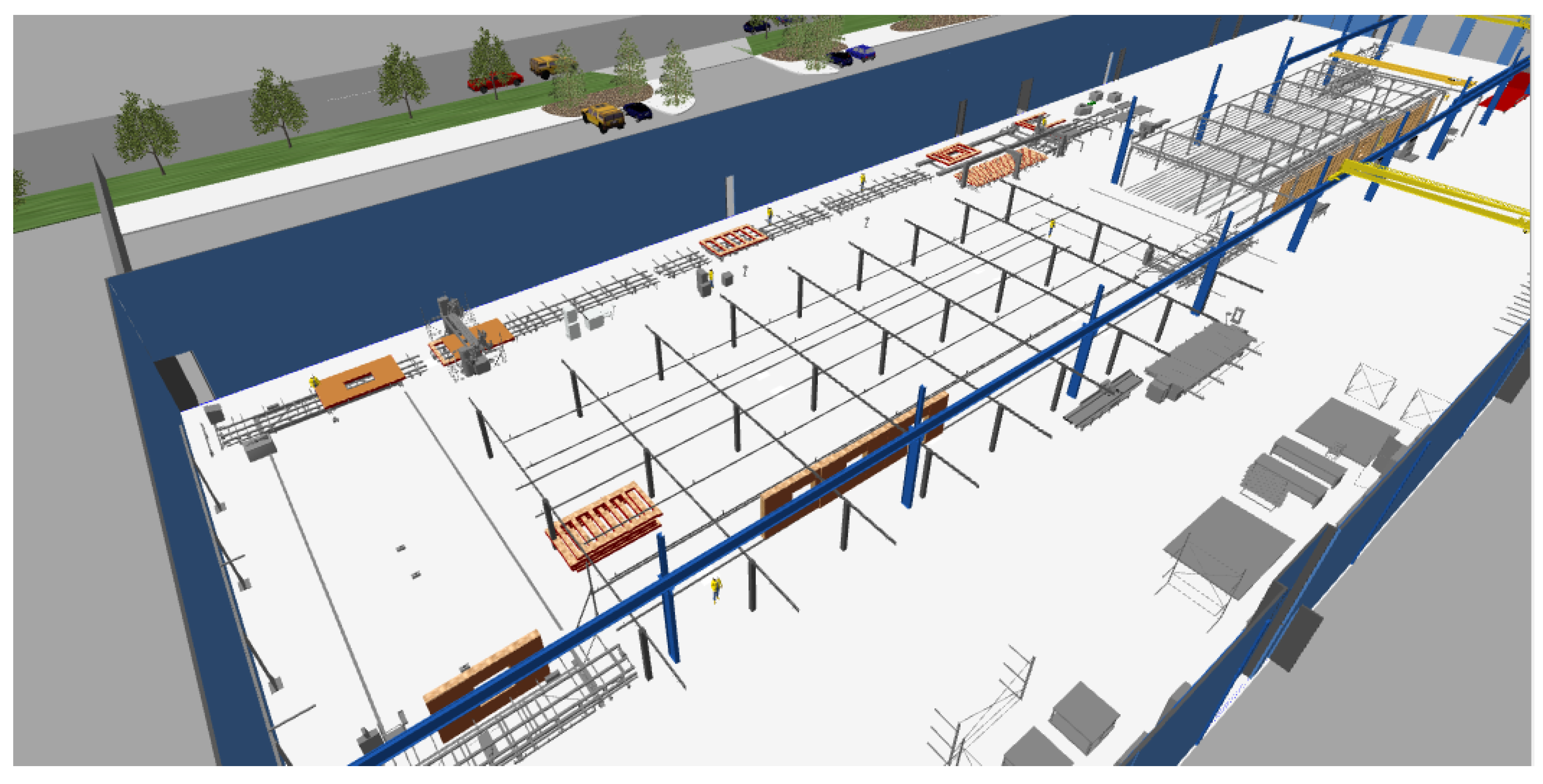

- A 3D simulation model for PCD, DW, and UW: Workstations on a production line affect one another, as the above discussions on DW and UW serve to demonstrate. A simulation model can be used to model the interdependencies among different workstations that determine the durations of UW and DW (which, in turn, affect the start times of cycles). A simulation model can also model the dependencies of workstations on materials/resources, scheduled events, and other forms of PCD. In the present study, a 3D simulation model was used in the estimation system to leverage the benefits associated with its realistic visual representation of the real factory. (Specifically, the 3D visual representation allows the user to determine whether the model is error-free and to validate its representativeness of reality. A 3D model that is developed to be representative of reality also helps users to better understand and analyze the real manufacturing operations.)

3. Procedure and Methods for System Deployment

3.1. Deploy Computer Vision for Automated Data Acquisition and Manually Collect Data for Testing

3.2. Identify Influencing Factors

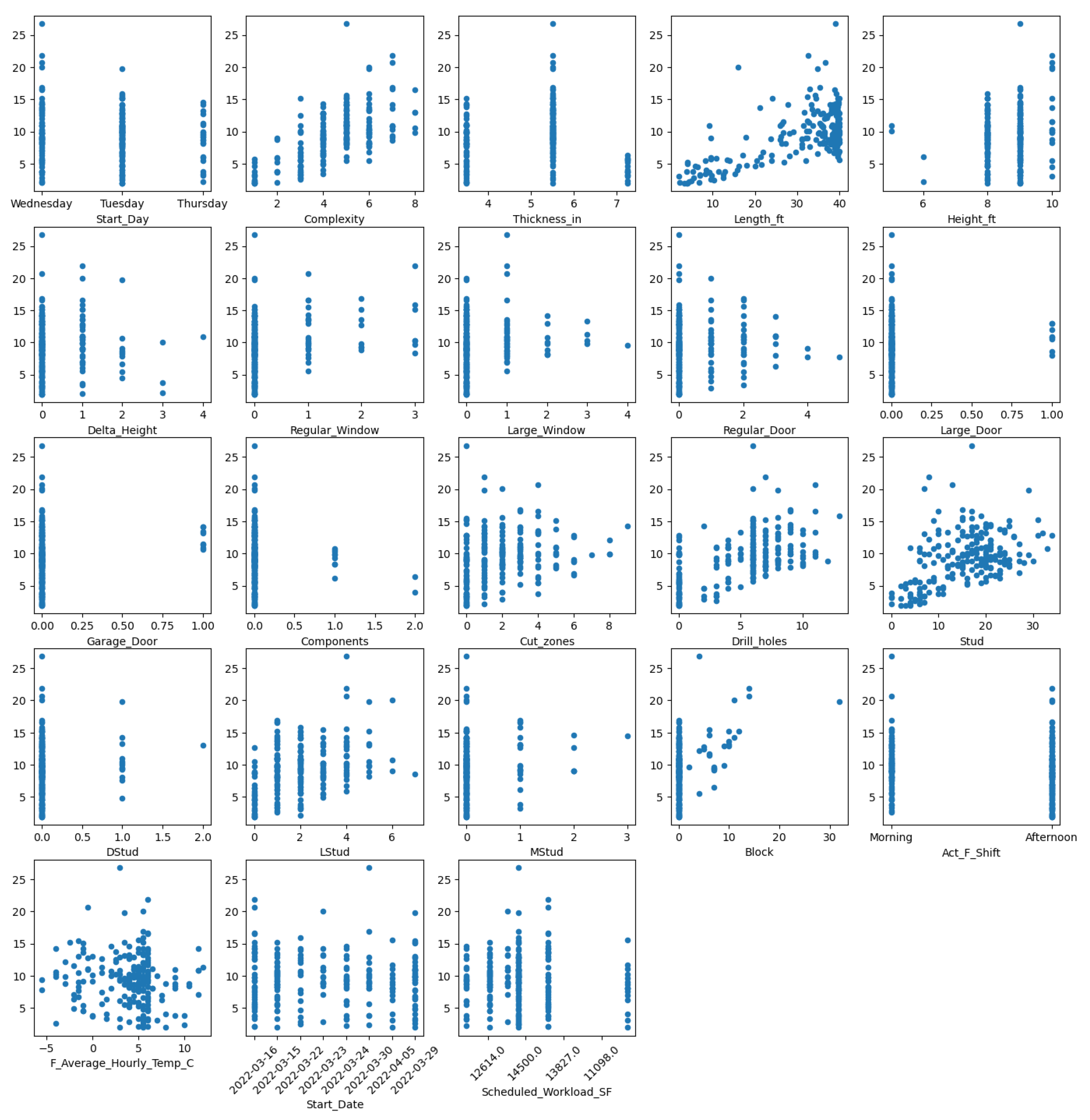

3.3. Prepare Data, Perform Exploratory Data Analysis, and Pre-Process Data

3.3.1. Data Preparation

3.3.2. Exploratory data analysis

3.3.2.1. Statistical description

- The range of PT values is wide (i.e., from 1.9 min to 26.8 min), with an average value of 9.3 min for wall lengths ranging from 2 ft to 40 ft and an average length of 30.3 ft.

- The number of panels with large doors, garage doors, preassembled components, double studs, multi-ply studs, and blocks is small relative to the total sample size of 212 wall panels. (Having a small amount of data could compromise accuracy with respect to identifying correlations between the features and the response variable, PT.)

- No wall panels in the dataset were framed on Mondays. As such, any potential effect of this day of the week on PT was not explored.

| Outcome | |||||||||

| Non-zero count | mean | std | min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max | ||

| PT (minutes) | 212 | 9.3 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 6.7 | 9.3 | 11.5 | 26.8 | |

| CT (minutes) | 212 | 11.6 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 7.7 | 10.2 | 13.4 | 58.4 | |

| Numerical features | |||||||||

| Feature | Non-zero count | mean | std | min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max | |

| 1 | Length (ft) | 212 | 30.3 | 11.8 | 2 | 25.5 | 36.2 | 39.2 | 40 |

| 2 | Height (ft) | 212 | 8.6 | 0.8 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| 3 | Delta height (ft) | 51 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.0 |

| 4 | Thickness (in) | 212 | 5.1 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 7.2 |

| 5 | Regular windows | 37 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 6 | Large windows | 49 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 7 | Regular doors | 60 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 8 | Large doors | 8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 9 | Garage doors | 8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | Preassembled components | 11 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 11 | Cutting zones | 150 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| 12 | Drilled holes | 164 | 5.1 | 3.4 | 0 | 2.8 | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| 13 | Studs | 208 | 15.7 | 7.5 | 0 | 10 | 17 | 21 | 34 |

| 14 | Double studs | 14 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 15 | L-shaped studs | 179 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 16 | Multi-ply studs | 26 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 17 | Blocks | 27 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 |

| 18 | Avg hourly temp. (°C) | N/A | 3.9 | 3.4 | −5.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 6 | 12 |

| 19 | Complexity | 212 | 4.4 | 1.6 | 1 | 3.75 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| 20 | Scheduled workload (sf) | 212 | 14,654 | 2,582 | 11,098 | 12,614 | 14,500 | 16,492 | 21,715 |

| 21 | Panel sequence | 212 | N/A | ||||||

| Categorical features | |||||||||

| Feature | Non-zero count | Categories | Top | Freq. | |||||

| 22 | Day | 212 | [‘Tuesday’, ‘Wednesday’, ‘Thursday’] | Tuesday | 112 | ||||

| 23 | Shift | 212 | [‘Morning’, ‘Afternoon’] | Afternoon | 125 | ||||

| 24 | Date | 212 | [‘2022-03-15’, ‘2022-03-16’, ‘2022-03-22’, ‘2022-03-23’,’2022-03-24’, ‘2022-03-29’, ‘2022-03-30’, ‘2022-04-05’] | 2022-03-16 | 41 | ||||

3.3.2.2. Correlation with PT

| Feature | Spearman’s coefficient | Feature | Spearman’s coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity | 0.63 | Multi-ply studs | 0.17 |

| Drilled holes | 0.54 | Large doors | 0.10 |

| Length (ft) | 0.49 | Regular doors | 0.10 |

| Studs | 0.42 | Double studs | 0.10 |

| L-shaped studs | 0.39 | Height (ft) | 0.08 |

| Blocks | 0.35 | Delta height (ft) | 0.05 |

| Cutting zones | 0.31 | Thickness (in) | 0.04 |

| Regular windows | 0.28 | Scheduled workload (SF) | −0.02 |

| Large window | 0.20 | Preassembled components | −0.06 |

| Garage doors | 0.20 | Avg hourly temp. (°C) | −0.11 |

3.3.2.3. Multicollinearity

| Feature | VIF | Feature | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height_ft | 80.5 | Large_Window | 2.9 |

| Length_ft | 60.7 | Regular_Door | 2.7 |

| Complexity | 48.6 | Regular_Window | 2.0 |

| Scheduled_Workload_SF | 42.2 | Start_Day_Thursday | 1.6 |

| Thickness_in | 36.9 | Block | 1.6 |

| Stud | 31.2 | Large_Door | 1.4 |

| Drill_holes | 11.7 | Delta_Height | 1.4 |

| Act_F_Shift_Afternoon | 6.0 | DStud | 1.4 |

| F_Average_Hourly_Temp_C | 5.8 | MStud | 1.4 |

| LStud | 4.0 | Preassembled components | 1.3 |

| Cut_zones | 4.0 | Garage_Door | 1.3 |

| Start_Day_Tuesday | 3.3 |

3.3.3. Data Pre-Processing

3.4. Select Performance Evaluation Metrics

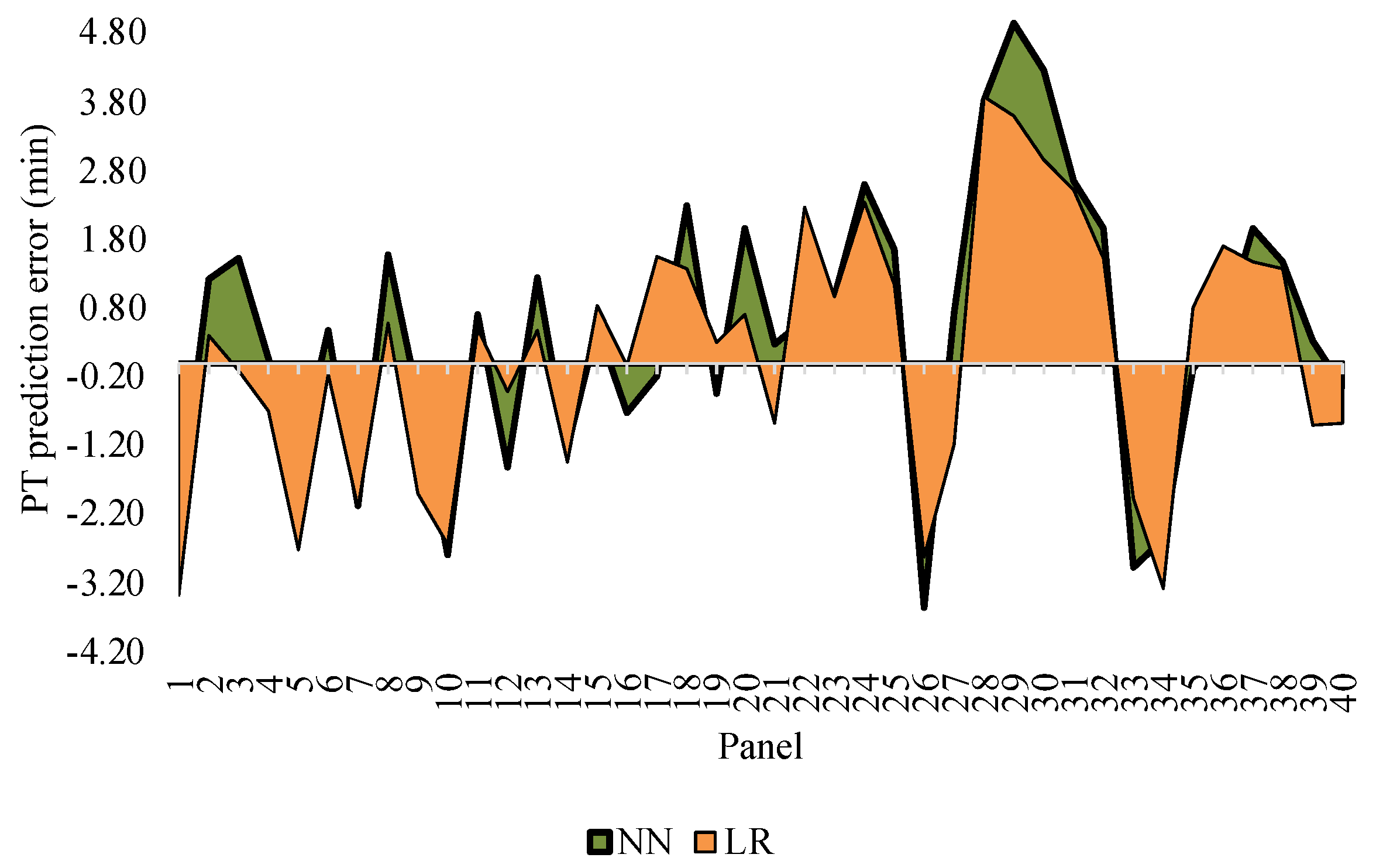

- The prediction error, , was calculated satisfying Eq. (4). This metric was selected to examine whether the predictions tended to overestimate (positive error value) or underestimate (negative error value) true values, as well as to determine the degree of variance of the measures from their true values for each panel.where is the prediction error corresponding to panel , is the predicted value for panel , and is the actual value corresponding to panel .

- The sum of errors, SE, was calculated satisfying Eq. (5). This metric was used to evaluate whether the predictions made for a batch of panels are cumulatively overestimated or underestimated.where is the total number of panels used for evaluation.

- The MAE was calculated satisfying Eq. (6). This metric was used to determine the average degree of variance of the predictions from their true values, regardless of whether they had been overapproximated or underapproximated.

- The mean percentage error (MPE was calculated satisfying Eq. (7). This metric was used to evaluate the prediction errors as a percentage of the true values.

- The root mean squared error (RMSE) was calculated satisfying Eq. (8). This metric was used in addition to MAE as it is useful for detecting outlier values since it assigns a higher penalty to larger errors compared to MAE.

3.5. Build PT Prediction Models

3.5.1. Artificial Neural Network Model

3.5.2. Linear Regression Model

3.5.3. Random Forest Model

3.6. Develop UCD and ID Estimation Models

3.7. Build the Simulation Model

4. System Testing Results and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of PT Predictions

4.2. Evaluation of CT Predictions

5. Further Analysis of the Findings

5.1. Use of Computer Vision Data

5.2. Influencing Factors

5.3. The Performance of Different Machine-Learning Algorithms

5.4. Criticality of Unpredictable Delays

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

6.2. Implications for the Industry

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

Acknowledgements

Disclosure statement

References

- A. Caggiano, Manufacturing system BT - CIRP encyclopedia of production engineering, in: L. Laperrière, G. Reinhart (Eds.), Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014: pp. 830–836. [CrossRef]

- F. Alsakka, I. El-Chami, H. Yu, M. Al-Hussein, Computer vision-based process time data acquisition for offsite construction, Autom Constr. 149 (2023) Article no. 104803. [CrossRef]

- F. Alsakka, H. Yu, F. Hamzeh, M. Al-Hussein, Factors influencing cycle times in offsite construction, in: Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), Lille, France, 2023: pp. 723–734. [CrossRef]

- L.C. Chao, Assessing earth-moving operation capacity by neural network-based simulation with physical factors, Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering. 16 (2001) 287–294. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Zayed, D.W. Halpin, Simulation as a Tool for Pile Productivity Assessment, J Constr Eng Manag. 130 (2004) 394–404. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Zayed, D.W. Halpin, Pile Construction Productivity Assessment, J Constr Eng Manag. 131 (2005) 705–714. [CrossRef]

- C.M. Tam, A.W.T. Leung, D.K. Liu, Nonlinear Models for Predicting Hoisting Times of Tower Cranes, Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering. 16 (2002) 76–81. [CrossRef]

- C.M. Tam, T.K.L. Tong, S.L. Tse, Modelling hook times of mobile cranes using artificial neural networks, 6193 (2010) 839–849. [CrossRef]

- L.C. Chao, M.J. Skibniewski, Estimating construction productivity: Neural-network-based approach, 8 (1994) 234–251. [CrossRef]

- M. Lu, S. AbouRizk, U. Hermann, Estimating Labor Productivity Using Probability Inference Neural Network, Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering. 14 (2000) 241–248. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, M. Lu, S. Abourizk, BIM-based data mining approach to estimating job man-hour requirements in structural steel fabrication, in: Proceedings of the 2015 Winter Simulation Conference, IEEE, 2015: pp. 3399–3410. [CrossRef]

- L. Song, S.M. AbouRizk, Measuring and modeling labor productivity using historical data, J Constr Eng Manag. 134 (2008) 786–794. [CrossRef]

- V. Benjaoran, N. Dawood, D. Scott, Bespoke precast productivity estimation with neural network model, in: Proceedings of the 20th Annual ARCOM Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 2004: pp. 63–74. http://www.arcom.ac.uk/-docs/proceedings/ar2004-1063-1074_Benjoran_Dawood_and_Scott.pdf.

- V. Benjaoran, N. Dawood, Intelligence approach to production planning system for bespoke precast concrete products, Autom Constr. 15 (2006) 737–745. [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, Y. Mohamed, M. Al-Hussein, A machine learning approach to predict production time using real-time RFID data in industrialized building construction, Advanced Engineering Informatics. 52 (2022) Article no. 101631. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Ahn, S.U. Han, M. Al-Hussein, Improvement of transportation cost estimation for prefabricated construction using geo-fence-based large-scale GPS data feature extraction and support vector regression, Advanced Engineering Informatics. 43 (2020) Article no.101012. [CrossRef]

- L. Shafai, Simulation based process flow improvement for wood framing home building production lines, MSc thesis, University of Alberta, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Altaf, M. Al-Hussein, H. Yu, Wood-frame wall panel sequencing based on discrete-event simulation and particle swarm optimization, in: Proceedings of the 31st International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction and Mining, 2014: pp. 254–261. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, M.S. Altaf, M. Lu, Automated production planning in panelized construction enabled by integrating discrete-event simulation and BIM, in: Proceedings of the 5th International/11th Construction Specialty Conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, 2015: p. Article no.048. [CrossRef]

- A.P.S. Bhatia, S.H. Han, O. Moselhi, Z. Lei, C. Raimondi, Simulation-based production rate forecast for a panelized construction production line, in: Proceedings of the 2019 CSCE Annual Conference, Laval (Greater Montreal), 2019: p. Article no. CON160. https://www.csce.ca/elf/apps/CONFERENCEVIEWER/conferences/2019/pdfs/PaperPDFversion_160_0419122655.pdf.

- Y.T. Tai, W.L. Pearn, J.H. Lee, Cycle time estimation for semiconductor final testing processes with Weibull-distributed waiting time, Int J Prod Res. 50 (2012) 581–592. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. Dominguez-Caballero, R. Ward, S. Ayvar-Soberanis, D. Curtis, Machining cycle time prediction: Data-driven modelling of machine tool feedrate behavior with neural networks, Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 75 (2022) 102293. [CrossRef]

- T. Chen, An effective fuzzy collaborative forecasting approach for predicting the job cycle time in wafer fabrication, Comput Ind Eng. 66 (2013) 834–848. [CrossRef]

- M. Kuhn, K. Johnson, Feature engineering and selection: A practical approach for predictive models, Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Alsakka, S. Assaf, I. El-Chami, M. Al-Hussein, Computer vision applications in offsite construction, Autom Constr. 154 (2023) 104980. [CrossRef]

- T.S. Huang, Computer vision: Evolution and promise, in: Proceedings of the 19th CERN School of Computing, 1996: pp. 21–25. [CrossRef]

- IBM, What is computer vision? | IBM, (2022). https://www.ibm.com/topics/computer-vision (accessed April 18, 2022).

- KBV research, Global Computer Vision Market by Product Type, by Component, by Application, by Vertical, by Region, Industry Analysis and Forecast 2020-2026, (2020). https://www.kbvresearch.com/computer-vision-market/ (accessed April 19, 2022).

- Verified Market Research, Global Computer Vision Market Size By Application(Automotive, Food & Beverage, Sports & Entertainment, Consumer Electronics, Robotics, Medical), By Geographic Scope And Forecast, 2021.

- Data Bridge Market Research, Global Computer Vision Market – Industry Trends and Forecast to 2029, 2022.

- Z. Zheng, Z. Zhang, W. Pan, Virtual prototyping-and transfer learning-enabled module detection for modular integrated construction, Autom Constr. 120 (2020) Article no. 103387. [CrossRef]

- Z.C. Wang, B. Yang, Q.L. Zhang, Automatic detection and tracking of precast walls from surveillance construction site videos, in: Life-Cycle Civil Engineering: Innovation, Theory and Practice, CRC Press/Balkema, 2021: pp. 1439–1446. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, Q. Zhang, B. Yang, T. Wu, K. Lei, B. Zhang, T. Fang, Vision-Based Framework for Automatic Progress Monitoring of Precast Walls by Using Surveillance Videos during the Construction Phase, Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering. 35 (2021) 04020056. [CrossRef]

- A. Ahmadian Fard Fini, M. Maghrebi, P.J. Forsythe, T.S. Waller, Using existing site surveillance cameras to automatically measure the installation speed in prefabricated timber construction, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. 29 (2021) 573–600. [CrossRef]

- P. Martinez, B. Barkokebas, F. Hamzeh, M. Al-Hussein, R. Ahmad, A vision-based approach for automatic progress tracking of floor paneling in offsite construction facilities, Autom Constr. 125 (2021) Article no.103620. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Casson, L.D.M. Farmer, Understanding and checking the assumptions of linear regression: A primer for medical researchers, Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 42 (2014) 590–596. [CrossRef]

- H. Adeli, Neural Networks in Civil Engineering: 1989–2000, Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering. 16 (2001) 126–142. [CrossRef]

- Moselhi, T. Hegazy, P. Fazio, Neural networks as tools in construction, J Constr Eng Manag. 117 (1991) 606–625. https://doi-org.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(1991)117:4(606)open_in_new.

- K. Gurney, An introduction to neural networks, 1st ed., CRC Press, 1997. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Jain, J. Mao, K.M. Mohiuddin, Artificial neural networks: a tutorial, Computer (Long Beach Calif). 29 (1996) 31–44. [CrossRef]

- COCO Consortium, COCO - Common Objects in Context, (n.d.). https://cocodataset.org/#home (accessed June 9, 2022).

- A. Bochkovskiy, C.-Y. Wang, H.-Y.M. Liao, Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection, ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2004.10934. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Time and Date AS, Weather for Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, (2023). https://www.timeanddate.com/weather/canada/edmonton (accessed March 16, 2023).

- R.M. O’brien, A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors, Qual Quant. 41 (2007) 673–690. [CrossRef]

- H2O.ai, Overview — H2O 3.40.0.3 documentation, (2023). https://docs.h2o.ai/h2o/latest-stable/h2o-docs/index.html (accessed April 26, 2023).

- H2O.ai, Grid (Hyperparameter) Search — H2O 3.40.0.3 documentation, (2023). https://docs.h2o.ai/h2o/latest-stable/h2o-docs/grid-search.html (accessed April 26, 2023).

- T.D. Gedeon, Data Mining of Inputs: Analysing Magnitude and Functional Measures, Int J Neural Syst. 08 (1997) 209–218. [CrossRef]

- RapidMiner, RapidMiner | Amplify the Impact of Your People, Expertise & Data, (n.d.). https://rapidminer.com/ (accessed April 24, 2023).

- H2O.ai, Variable Importance — H2O 3.40.0.3 documentation, (2023). https://docs.h2o.ai/h2o/latest-stable/h2o-docs/variable-importance.html (accessed April 26, 2023).

- Engineering at Alberta, Simphony.NET 4.6, (n.d.). https://www.ualberta.ca/engineering/research/groups/construction-simulation/simphony.html (accessed July 4, 2022).

- Wolfram MathWorld, Least Squares Fitting, (n.d.). https://mathworld.wolfram.com/LeastSquaresFitting.html (accessed July 4, 2022).

- F.J. Massey, The Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Goodness of Fit, J Am Stat Assoc. 46 (1951) 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Simio, Simulation, production planning and scheduling software, (n.d.). https://www.simio.com/ (accessed March 14, 2023).

| Actual PT (min) | NN | LR | RF | Fixed rate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted PT (min) | (min) | Predicted PT (min) | (min) | Predicted PT (min) | (min) | Predicted PT (min) | (min) | ||

| 1 | 14.17 | 11.95 | −2.22 | 10.78 | −3.39 | 11.36 | −2.81 | 7.33 | −6.84 |

| 2 | 10.58 | 11.79 | 1.21 | 10.98 | 0.40 | 10.82 | 0.24 | 8.61 | −1.97 |

| 3 | 8.83 | 10.34 | 1.51 | 8.71 | −0.12 | 9.81 | 0.98 | 6.83 | −2.00 |

| 4 | 9.92 | 10.00 | 0.08 | 9.23 | −0.69 | 11.14 | 1.22 | 8.03 | −1.89 |

| 5 | 15.17 | 13.75 | −1.42 | 12.45 | −2.72 | 11.40 | −3.77 | 5.31 | −9.86 |

| 6 | 4.58 | 5.05 | 0.47 | 4.42 | −0.16 | 5.95 | 1.37 | 4.39 | −0.19 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | |

| 38 | 7.42 | 8.90 | 1.48 | 8.79 | 1.37 | 8.78 | 1.36 | 8.13 | 0.71 |

| 39 | 12.67 | 12.99 | 0.32 | 11.77 | −0.90 | 11.08 | −1.59 | 8.71 | −3.96 |

| 40 | 11.33 | 11.00 | −0.33 | 10.46 | −0.87 | 9.83 | −1.50 | 7.77 | −3.56 |

| MAE (min) | 1.57 | 1.52 | 1.81 | 2.87 | |||||

| MPE | 19% | 19% | 21% | 29% | |||||

| SE (min) | 17.68 | 5.62 | 10.01 | −98.64 | |||||

| Actual CT (min) | Prediction system | Fixed rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted CT (min) | (min) | Predicted CT (min) | (min) | ||

| 1 | 22.02 | 15.21 | −6.81 | 8.62 | −13.40 |

| 2 | 11.5 | 12.06 | 0.56 | 10.12 | −1.38 |

| 3 | 8.9 | 10.66 | 1.76 | 8.04 | −0.86 |

| 4 | 10 | 10.68 | 0.68 | 9.44 | −0.56 |

| 5 | 17.63 | 14.62 | −3.01 | 6.25 | −11.38 |

| 6 | 7.57 | 7.64 | 0.07 | 5.16 | −2.41 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | |

| 38 | 7.82 | 10.38 | 2.56 | 9.56 | 1.74 |

| 39 | 18.67 | 14.61 | −4.06 | 10.25 | −8.42 |

| 40 | 14.8 | 12.18 | −2.62 | 9.14 | −5.66 |

| MAE (min) | 3.03 | 4.72 | |||

| MPE | 23% | 34% | |||

| SE (min) | −50.10 | −156.25 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).