Submitted:

16 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study sites

2.2. Mist-netting and sampling birds

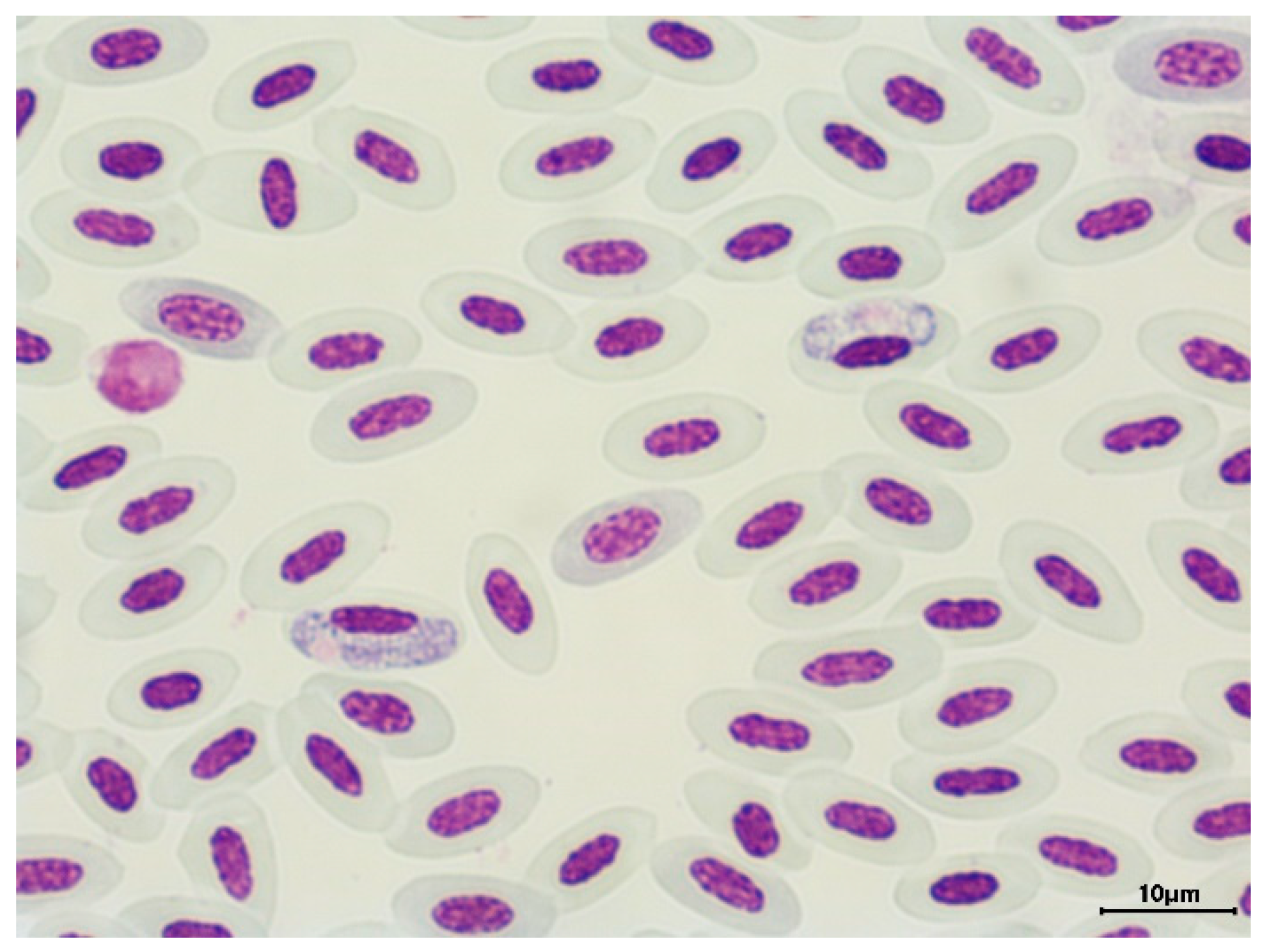

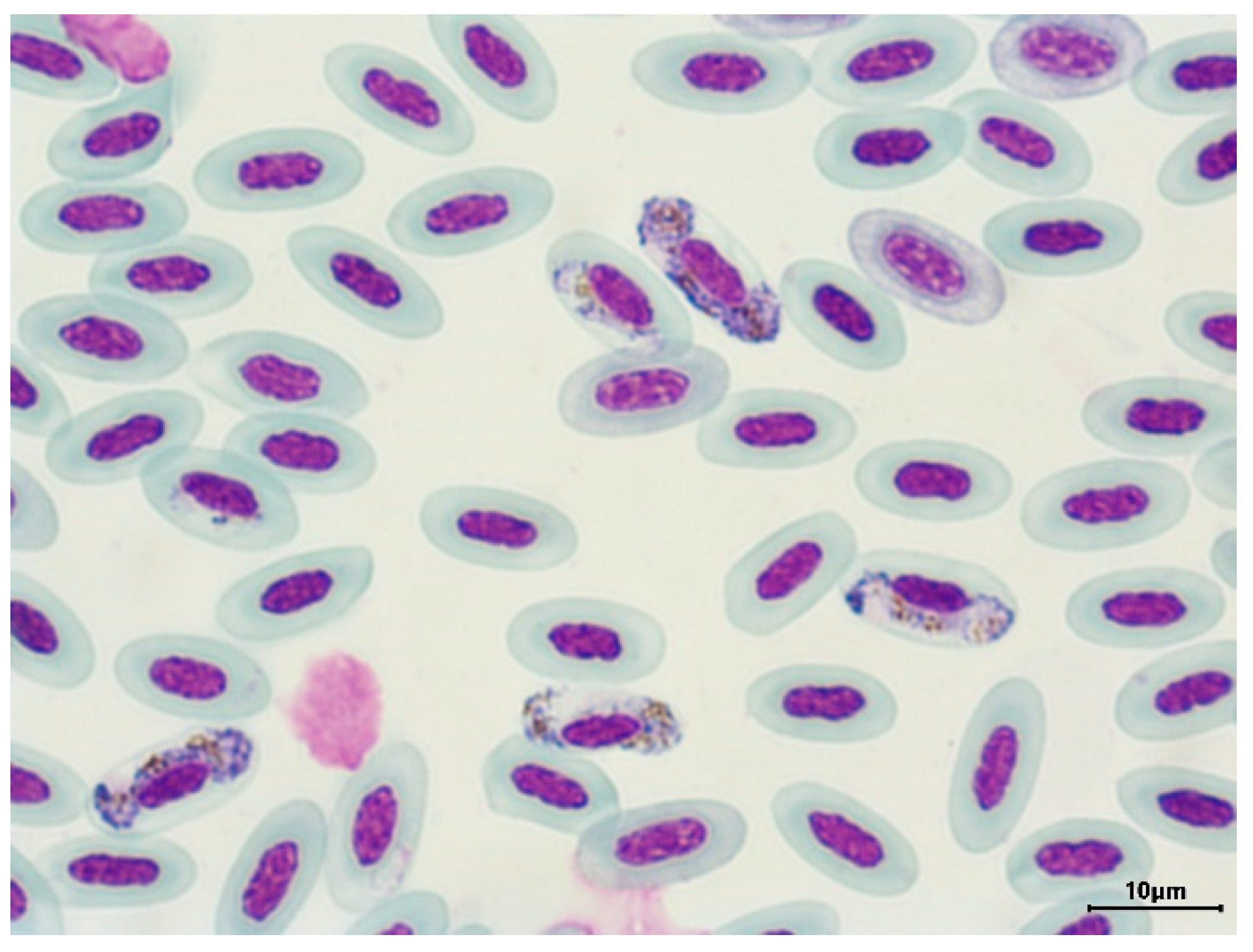

2.3. Microscopic analysis of haemosporidian

2.4. Molecular analysis of haemosporidian

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Haemosporidian infections based on the microscopical and molecular analyses

3.2. Haemosporidian infections in juvenile birds based on the microscopical and molecular analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valkiūnas, G. Avian Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia; CRC press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Iezhova, T.A. Keys to the avian Haemoproteus parasites (Haemosporida, Haemoproteidae). Malaria Journal 2022, 21, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, O.; Waldenström, J.; Bensch, S. A new PCR assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avian blood. J. Parasitol. 2004, 90, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensch, S.; Hellgren, O.; Pérez-Tris, J. MalAvi: A public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MalAvi database. Available online: http://mbio-serv2.mbioekol.lu.se/Malavi/index.html (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Kučera, J. Blood parasites of birds in Central Europe. 1.Survey of literature. The incidence in domestic birds and general remark to the incidence in wild birds. Folia Parasitologica 1981, 28, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kučera, J. Blood parasites of birds in Central Europe. 2. Leucocytozoon. Folia Parasitologica 1981, 28, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kučera, J. Blood parasites of birds in Central Europe. 3. Plasmodium and Haemoproteus. Folia Parasitologica 1981, 28, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hauptmanová, K.; Benedikt, V.; Literák, I. Blood Parasites in Passerine Birds in Slovakian East Carpathians. Acta Protozool. 2006, 45, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, M.; Kisková, J. Absence of blood parasites in the Alpine Accentor Prunella collaris. Oecologia Montana 2010, 19, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Berthová, L.; Országhová, Z.; Valkiūnas, G. The first report of nine species of haemosporidian parasites (Haemosporida: Haemoproteus, Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon) in wild birds from Slovakia. Biologia 2012, 67, 931–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šujanová, A.; Špitalská, E.; Václav, R. Seasonal dynamics and diversity of haemosporidians in a natural woodland bird community in Slovakia. Diversity 2021, 13, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimírová, M.; Hamšíková, Z.; Kocianová, E.; Marini, G.; Mojšová, M.; Mahríková, L.; Berthová, L.; Slovák, M.; Rosá, R. Relative density of host-seeking ticks in different habitat types of south-western Slovakia. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2016, 69, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthová, L.; Slobodník, V.; Slobodník, R.; Olekšák, M.; Sekeyová, Z.; Svitálková, Z.; Kazimírová, M.; Špitalská, E. The natural infection of birds and ticks feeding on birds with Rickettsia spp. and Coxiella burnetii in Slovakia. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2016, 68, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, L. Identification guide to European passerines, 4th ed.; Lars Svensson, Stockholm, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hromádko, M.; Horáček, J.; Chytil, J.; Pithart, K.; Škopek. J. Guide to the determination of our passerines, Publisher ZUV, Hradec Králové (in Czech). 1992.

- Hromádko, M.; Horáček, J.; Chytil, J.; Pithart, K.; Škopek. J. Guide to the determination of our passerines, Publisher ZUV, Hradec Králové (in Czech). 1993.

- Hromádko, M.; Horáček, J.; Chytil, J.; Pithart, K.; Škopek., J. Guide to the determination of our passerines; Publisher ZUV, Hradec Králové (in Czech), 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bensch, S.; Stjernman, M.; Hasselquist, D.; Ostman, O.; Hansson, B.; Westerdahl, H.; Pinheiro, R.T. Host specificity in avian blood parasites: A study of plasmodium and haemoproteus mitochondrial DNA amplified from birds. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2000, 267, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A. , Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GenBank database. Available online: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Bell, J.A.; Weckstein, J.D.; Fecchio, A.; Tkach, V.V. A new real-time pcr protocol for detection of avian haemosporidians. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedl, T.W.P.; Groscurth, E. A real-time PCR protocol for simple and fast quantification of blood parasite infections in evolutionary and ecological studies and some data on intensities of blood parasite infections in a subtropical weaverbird. J. Ornithol. 2012, 153, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiersch, T.R.; Wachtel, S.S. On the evolution of genome size of birds. J. Hered. 1991, 82, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Past: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeo. Electronica 2001, 4, 4, http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm. [Google Scholar]

- EasyCalculation. Available online: https://www.easycalculation.com/statistics (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Valkiũnas, G.; Izheova, T.A.; Križanauskiene, A.; Palinauskas, V.; Sehgal, R.N.M.; Bensch, S. A comparative analysis of microscopy and PCR-based detection methods for blood parasites. J. Parasitol. 2008, 94, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvi, S.I.; Schultz, J.J.; Atkinson, C.T. PCR diagnostics underestimate the prevalence of avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum) in experimentally-infected passerines. J. Parasitol. 2002, 88, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, F.A.; Sehgal, R.N.M.; Jones, H.I.; Smith. T.B. A comparative analysis of PCR-based detection methods for avian malaria. J. Parasitol. 2002, 88, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldenstrom, J. , Bensch, S.; Hasselquist, D.; Ostman, O. A new nested polymerase chain reaction method very efficient in detecting Plasmodium and Haemoproteus infections from avian blood. J. Parasitol. 2004, 90, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krone, O.; Valkiũnas, G.; Lessow, O.; Müller, K.; Iezhova, T.A.; Fickel, J.; Bensch, S. Haemosporidian blood parasites in european birds of prey and owls. J. Parasitol. 2087, 94, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, S.; Ricklefs, R.E. Parasitemia in PCR-detected Plasmodium and Haemoproteus infections in birds. J. Avian Biol. 2008, 39, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garamszegi, L.Z. The sensitivity of microscopy and PCR-based detection methods affecting estimates of prevalence of blood parasites in birds. J. Parasitol. 2010, 96, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumm, Y.R.; Bakaloudis, D.; Barboutis, C.; Cecere, J.G.; Eraud, C.; Fischer, D.; Hering, J.; Hillerich, K.; Lormée, H.; Mader, V.; Masello, J.F.; Metzger, B.; Rocha, G.; Spina, F.; Quillfeldt, P. Prevalence and genetic diversity of avian haemosporidian parasites in wild bird species of the order Columbiformes. Parasitol. Res., 2021, 120, 1405–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynton-Jenkis, J.G.; Chaine, A.S.; Russell, A.F.; Bonneaud, C. Parasite detection and quantification in avian blood is dependent on storage medium and duration. Ecol. Evolution, 2023, 13, e9819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noni, V.; Tan, C.S. Prevalence of haemosporidia in Asian Glossy Starling with discovery of misbinding of Haemoproteus-specific primer to Plasmodium genera in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. BMC Vet Res 2023, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehsani Amrei, S.F.; Motevalli Haghi, A.; Nateghpour, M.; Mohebali, M.; Youssefi, M.; Raiesi, O.; Mahdavi, S.; Farivar, L. Detection of Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia in Migratory and Native Birds in Mazandaran and Golestan Provinces, Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2022, 16, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; Norouzian, H.; Nayebzadeh, H.; Shokrani, H. Molecular Detection and Phylogenetic Analysis of Avian Haemosporidian Parasites in House Sparrows (Passer domesticus) of Western Iran. J Wildl Dis. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarría, X.; Matta, N.E.; Cadena-Ortíz, H.; Alarcón, I.; Bahamonde-Vinueza, D.; González, A.D.; Bonaccorso, E. Haemosporidian parasites in the ash-breasted Sierra finch (Geospizopsis plebejus): insights from an Andean dry forest population. Parasitology, 2022, 150, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Bensch, S.; Iezhova, T.A.; Križanauskiene, A.; Hellgren, O.; Bolshakov, C.V. Nested cytochorome B polymerase chain reaction diagnostics underestimate mixed infections of avian blood haemosporidian parasites: Microscopy is still essential. J. Parasitol. 2006, 92, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehtindjiev, P.; Križanauskienė, A.; Bensch, S.; Palinauskas, V.; Asghar, M.; Dimirov, D.; Scebba, S.; Valkiūnas, G. A new morphologically distinct avian malaria parasite that fails detection by established polymerase chain reaction-based protocols for amplification of the cytochrome b gene. J. Parasitol. 2012, 98, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciloglu A, Ellis VA, Bernotienė R, Valkiūnas G, Bensch S. A new one-step multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection and identification of avian haemosporidian parasites. Parasitol Res 2019, 118, 191–201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basto, N.; Rodríguez, O.A.; Marinkelle, C.J.; Gutiérrez, R.; Matta, N. Haematozoa in birds from La Macarena National Natural Park (Colombia). Caldasia. 2006, 28, 371–7. [Google Scholar]

- Doussang, D. , González-Acuña, D., Torres-Fuentes, L.G. et al. Spatial distribution, prevalence and diversity of haemosporidians in the rufous-collared sparrow, Zonotrichia capensis. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciloglu, A.; Ergen, A.G.; Inci, A.; Dik, B.; Duzlu, O.; Onder, Z.; Yetismis, G.; Bensch, S.; Valkiūnas, G.; Yildrim, A. Prevalence and genetic diversity of avian haemosporidian parasites at an intersection point of bird migration routes: Sultan Marshes National Park, Turkey. Acta Trop. 2020, 210, 105465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillfeldt, P.; Arriero, E.; Martínez, J.; Masello, J.F.; Merino, S. Prevalence of blood parasites in seabirds- a review. Front Zool. 2011, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarov, N.; Kampen, H.; Wiegmann, A.; Werner, D.; Bensch, S. Blood parasites in vectors reveal a united blackfly community in the upper canopy. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Martínez-Gómez, J.E.; Valkiūnas, G.; Loiseau, C.; Bell, D.A.; Sehgal, R.N. Diversity and phylogenetic relationships of hemosporidian parasites in birds of Socorro Island, México and their role in the re-introduction of the Socorro Dove (Zenaida graysoni). J Parasitol 2013, 99, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heym, E.C.; Kampen, H.; Krone, O.; Schäfer, M.; Werner, D. Molecular detection of vector-borne pathogens from mosquitoes collected in two zoological gardens in Germany. Parasitol Res 2019, 118, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Ilgūnas, M.; Bukauskaitė, D.; Chagas, C.R.F.; Bernotienė, R.; Himmel, T.; Harl, J.; Weissenböck, H.; Iezhova, T.A. Molecular characterization of six widespread avian haemoproteids, with description of three new Haemoproteus species. Acta Tropica 2019, 197, 105051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nourani, L.; Aliabadian, M.; Dinparast Djadid, N.; Mirshamsi, O. Occurrence of Haemoproteus spp. (Haemosporida: Haemoproteidae) in New Host Records of Passerine Birds from the East of Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2018, 13, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bennet, G.F.; Peirce, M.A.; Ashford, R.W. Avian haematozoa: mortality and pathogenicity. J. Nat. Hist. 1993, 27, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Catedral, L.; Brunton, D.; Stidworthy, M.F.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Pennycott, T.; Schulze, C.; Braun, M.; Wink, M.; Gerlach, H.; Pendl, H.; Gruber, A.D.; Ewen, J.; Pérez-Tris, J.; Valkiūnas, G.; Olias, P. Haemoproteus minutus is highly virulent for Australasian and South American parrots. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Tris, J.; Hellgren, O.; Križanauskienė, A.; Waldenström, J.; Secondi, J.; Bonneaud, C.; Fjeldsȧ, J.; Hasselquist, D.; Bensch, S. Within-Host Speciation of Malaria Parasites. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, Y.; Verbeek, M.; Michelsen, V.; Bjørn, P.; Los, W.; Steeman, F.; Bailly, N.; Basire, C.; Chylarecki, P.; Stloukal, E.; Hagedorn, G.; Wetzel, F.; Glöckler, F.; Kroupa, A.; Korb, G.; Hoffmann, A.; Häuser, C.; Kohlbecker, A.; Müller, A.; Güntsch, A.; Stoev, P.; Penev, L. Fauna Europaea – all European animal species on the web. Biodiversity Data Journal 2014, 2, e4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauna Europaea database Available online:. Available online: http://www.faunaeur.org/distribution_table.php (accessed on 22 February 2023).

| Bird species | Prevalence | Haemosporidian species | Haemosporidian Lineage in MALAVI | Haemosporidian Lineage in GenBank |

| Urbanized habitats | ||||

| Parus major | 5/37 | P. (Haemamoeba) relictum | SGS1 (8) | MK652232 |

| Parus montanus | 1/6 | |||

| Cyanistes caeruleus | 1/9 | |||

| Sylvia atricapilla | 1/28 | |||

| Sylvia atricapilla | 11/28 | H. (P.) parabelopolskyi | SYAT02 (7) SYAT10 (1) SYAT01 (2) SYAT07 (1) |

JN164719 AY831757 AY831750 AY831754 |

| Sylvia communis | 1/1 | H. (P.) majoris | CWT4 | KJ488675 |

| Fringilla coelebs | 4/6 | Haemoproteus (P.) sp. | CCF2 (3) CCF1 (1) |

AF495551 AF495550 |

| Emberiza citrinella | 1/1 | EMCIR01 | GU085190 | |

| Sylvia atricapilla | 3/28 | us (3) | ||

| Turdus merula | 1/9 | us | ||

| Turdus merula | 6/9 | P. (N.) vaughani | SYAT05 (6) | DQ847271 |

| Turdus merula | 1/9 | P. (H.) matutinum | LINN1 (3) | DQ847270 |

| Erithacus rubecula | 1/10 | |||

| Emberiza schoeniculus | 1/15 | |||

| Emberiza schoeniculus | 2/15 | P. (Giovannolaia) circumflexum | SYBOR02 (2) | DQ368392 |

| Turdus philomelos | 2/2 | BT7 TURDUS1 |

MK062195 KM361492 |

|

| Prunella modularis | 1/6 | TURDUS1 | KM361492 | |

| Parus major | 12/37 | Leucocytozoon sp. | PARUS19 (4) PARUS28 (1) PARUS4 (4) PARUS18 (1) STUR1/TURPEL01 (1) us (1) |

HM234027 JX855047 AY393795 HM234026 DQ847246/ KT376971 |

| Cyanistes caeruleus | 3/9 | PARUS19 PARUS4 PARUS50 |

HM234027 AY393795 JX855065 |

|

| Turdus merula | 1/9 | ON932273 | ||

| Turdus philomelos | 1/2 | dp | ||

| Sylvia atricapilla | 1/28 | PARUS4 | AY393795 |

|

| Prunella modularis | 1/6 | PRUMOD01 | KJ488638 | |

| 62/196 | ||||

| Natural habitats | ||||

| Sylvia atricapilla | 13/32 | H. (P.) parabelopolskyi | SYAT01 (9) SYAT02 (4) |

JN164718 JN164719 |

| Erithacus rubecula | 10/42 | H. (Parahaemoproteus) balmorali | ROBIN1/LULU1 | AY393807 |

| Carduelis carduelis | 1/11 | |||

| Emberiza schoeniculus | 1/2 | |||

| Sylvia atricapilla | 1/32 | |||

| T. philomelos | 1/1 | |||

|

Coccothraustes coccothraustes |

1/3 | H. (P.) concavocentralis | HAWF2 | GQ396708 |

| Turdus merula | 1/4 | H. (P.) minutus | TURDUS2 | KM361485 |

| Erithacus rubecula | 1/42 | H. (P.) pallidus | SYAT03 | JN164720 |

| Carduelis carduelis | 1/11 | |||

| Erithacus rubecula | 5/42 | Haemoproteus (P.) sp | CIRCUM01 (1) us (4) |

KC994896 |

|

Coccothraustes coccothraustes |

1/3 | HAWF1 | DQ368348 | |

| Carduelis carduelis | 1/11 | us | ||

| Emberiza citrinella | 1/4 | CCF6 | DQ368341 | |

| Scolopax rusticola | 1/1 | us | ||

| Sylvia atricapilla | 1/32 | us | ||

| Sylvia curruca | 1/4 | LWT1 | AF495563 | |

| Erithacus rubecula | 2/42 | P. (G.) circumflexum | TURDUS1 | KM361492 |

| Emberiza citrinella | 1/4 | |||

| Emberiza cia | 1/2 | P. (H.) relictum | SGS1 | JX196866 |

| Erithacus rubecula | 1/42 | DP | ||

| Passer montanus | 1/2 | SGS1 | MK652232 | |

| Fringilla coelebs | 1/3 | COLL1 | AY831747 | |

| Turdus merula | 2/4 | P. (N.) vaughani | SYAT05 (2) | OP546094 |

| Turdus merula | 1/4 | P. matutinum | LINN1 | DQ847270 |

| Cyanistes caeruleus | 1/4 | Plasmodium sp. | us | |

| Erithacus rubecula | 5/42 | Leucocytozoon sp. | BT2 BT5 SFC8 SYCON06 PARUS19 |

AY393802 AY393798 DQ847234 KP688305 HM234027 |

|

Coccothraustes coccothraustes |

3/3 | HAWF1 (1) us (2) |

DQ368348 | |

| Scolopax rusticola | 1/1 | SCORUS01 | LC230149 | |

| Cyanistes caeruleus | 1/4 | PARUS4 | AY393795 | |

| 63/121 | ||||

| Avian species | Haemosporidian species |

| Urbanized habitats | |

| Turdus merula | P. (N.) vaughani SYAT05, L. (L.) sp. |

| Cyanistes caeruleus | P. (H.) relictum SGS1, L. (L.) sp. PARUS19 |

| Parus major | P. (H.) relictum SGS1, L. (L.) sp. PARUS4 |

| Parus major | P. (H.) relictum SGS1, L. (L.) sp. PARUS18 |

| Parus major | P. (H.) relictum SGS1, L. (L.) sp. STUR1/TURPEL01 |

| Sylvia atricapilla | P. (H.) sp., L. (L.) sp. PARUS4 |

| Turdus philomelos | P. (G.) circumflexum BT7, L. (L.) sp. |

| Natural habitats | |

| Erithacus rubecula | H. (P.) sp., L. (L.) sp. BT2 |

| Scolopax rusticola | H. (P.) sp., L. (L.) sp. |

| Erithacus rubecula | H. (P.) balmorali ROBIN1/LULU1, L. (L.) sp. SFC8 |

| Coccothraustes coccothraustes | H. (P.) sp. HAWF1, L. (L.) sp. |

| Erithacus rubecula | P. (G.) circumflexum TURDUS1, L. (L.) sp. SYCON06 |

| Coccothraustes coccothraustes | H. (P.) concavocentralis HAWF2, L. (L.) sp. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).