1. Introduction

Concrete is the most widely used material in construction projects. However, with the acceleration of urbanization and the rapid development of construction projects, a substantial amount of abandoned concrete has resulted in severe environmental issues. Traditionally, waste concrete has often been treated as refuse, transported to landfills, or dumped in the natural environment, which not only leads to resource wastage but also causes pollution and environmental degradation [

1,

2,

3].

In recent years, the utilization of recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete has garnered significant attention as a solution to this problem [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Recycled concrete aggregates are obtained through processes such as crushing, screening, and washing of waste concrete and exhibit physical and mechanical properties similar to natural aggregates [

4,

5,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The utilization of recycled concrete aggregates not only reduces the consumption of natural resources but also lowers the processing costs associated with waste concrete, thereby contributing to the achievement of sustainability goals [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

However, due to the uncertainty in the properties and quality of waste concrete, there are some challenges associated with the use of recycled aggregates in certain engineering applications [

18]. For instance, recycled aggregates often exhibit a high porosity and increased water absorption [

9], which can lead to reduced workability of concrete. Additionally, harmful substances may be present in recycled aggregates, adversely affecting the mechanical properties and durability of concrete [

19,

20]. Therefore, the modification of recycled aggregates to enhance their performance and adaptability has become a focal point and a significant challenge in current research [

21].

This article aims to provide a comprehensive review of modification methods for recycled aggregates from waste concrete, and explore how to improve the performance of recycled aggregate and its application effect in concrete by introducing appropriate modifiers or processes. Specifically, this article will focus on the following aspects:

An overview of the physical and chemical properties of recycled concrete aggregates obtained from waste concrete.

Review existing methods and technologies for modifying recycled aggregates, encompassing physical, chemical, and biological approaches.

Summarize the current state of modification techniques, evaluate their pros and cons, and propose future research directions.

Through the research presented in this article, it is anticipated that new ideas and methods for the modification of recycled aggregates from waste concrete can be provided. This, in turn, will facilitate the widespread utilization of recycled aggregates in engineering practice and promote the direction of sustainable development in construction projects.

2. Differences Between Recycled Aggregates from Waste Concrete and Natural Aggregates

Recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete and natural aggregates are two distinct materials with several significant differences in terms of physical properties, chemical properties, mechanical performance, and sustainability [

22,

23]. The following sections will provide a detailed explanation of these differences and explore their impacts on concrete properties and engineering applications.

2.1. Physical Properties

Particle Shape and Gradation: Recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete typically have a more irregular particle shape compared to natural aggregates. The particle shape of recycled aggregates can be fractured, angular, or have rough surfaces, whereas natural aggregates tend to have smoother and more uniform particle shapes. There are noticeable differences in the particle size distribution (gradation) between recycled coarse aggregates and natural coarse aggregates, leading to poor gradation [

24].

Surface Characteristics: Due to the presence of a significant amount of adhering mortar on the surface of recycled aggregates, they are usually rougher in texture and contain more fine particles, capillary pores, and cracks resulting from the crushing process, whereas the surface of natural aggregates is relatively smoother [

14].

Water Absorption: The differences in surface characteristics between the two result in higher water absorption for recycled aggregates compared to natural aggregates, making recycled aggregates more prone to absorbing and retaining moisture. This can lead to reduced workability of concrete and an increase in the water-cement ratio.

2.2. Chemical Properties

Cement Hydration Products: Recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete carry a significant amount of cementitious mortar on their surfaces, and as a result, they contain a substantial amount of cement hydration products, such as C-S-H, calcium hydroxide, ettringite, etc., with an interface transition zone typically around 40-50μm in width [

25]. In contrast, natural aggregates primarily consist of components like calcium carbonate and silica dioxide. Therefore, there are substantial differences in chemical composition and properties between recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete and natural aggregates.

Harmful Substances: Recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete, especially those obtained from coastal or saline-alkali environments, may contain harmful substances like chloride ions, sulphates, organic materials, and other construction debris. These harmful substances can have adverse effects on the mechanical properties, durability, and resistance to chemical corrosion of concrete. In contrast, qualified natural aggregates typically do not contain harmful substances.

2.3. Mechanical Performance

Strength: Recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete typically exhibit lower strength compared to natural aggregates. The particles in recycled aggregates may have microcracks or fractured surfaces, and their gradation is often poorer, all of which contribute to their lower crushing values.

Interparticle Bonding: Due to their particle shape and the presence of mortar layers on their surfaces, recycled aggregates have weaker interparticle bonding with the cementitious matrix. This can result in reduced cohesion and crack resistance of the concrete.

2.4. Sustainability

Resource Utilization: The utilization of recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete can reduce the consumption of natural resources and mitigate the environmental damage caused by mining activities. In contrast, natural aggregates need to be obtained through mining and other related processing.

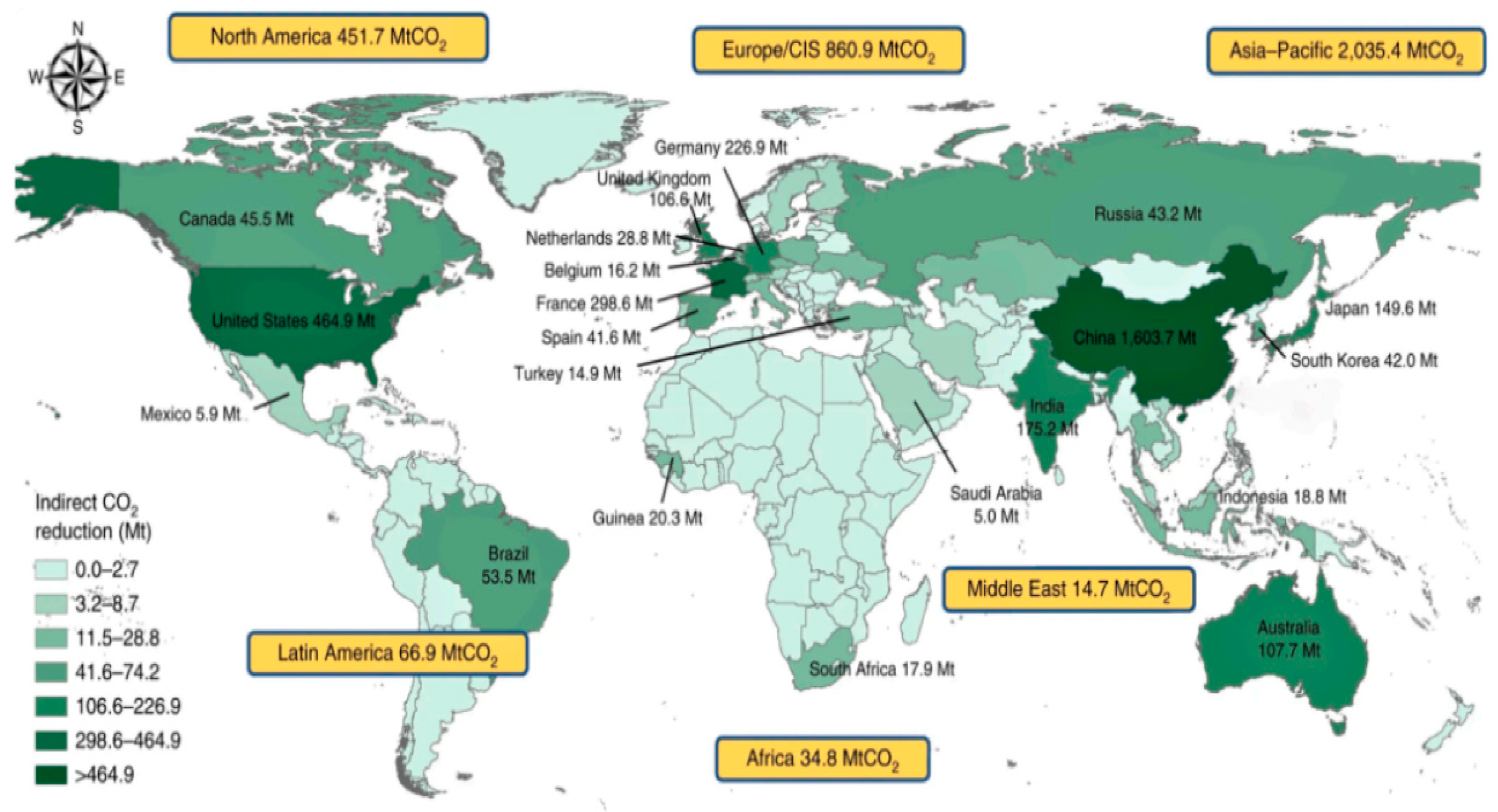

Environmental Impact: The use of recycled aggregates can reduce the landfilling and dumping of waste concrete, minimizing environmental pollution and the wastage of land resources. Furthermore, the production process of recycled aggregates is typically more energy-efficient and emission-reducing compared to the production process of natural aggregates, significantly lowering the carbon emissions associated with concrete. The global indirect carbon footprint reduction achieved by using carbonated solid waste in mortar and concrete is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.5. Impact on Concrete Performance and Engineering Applications

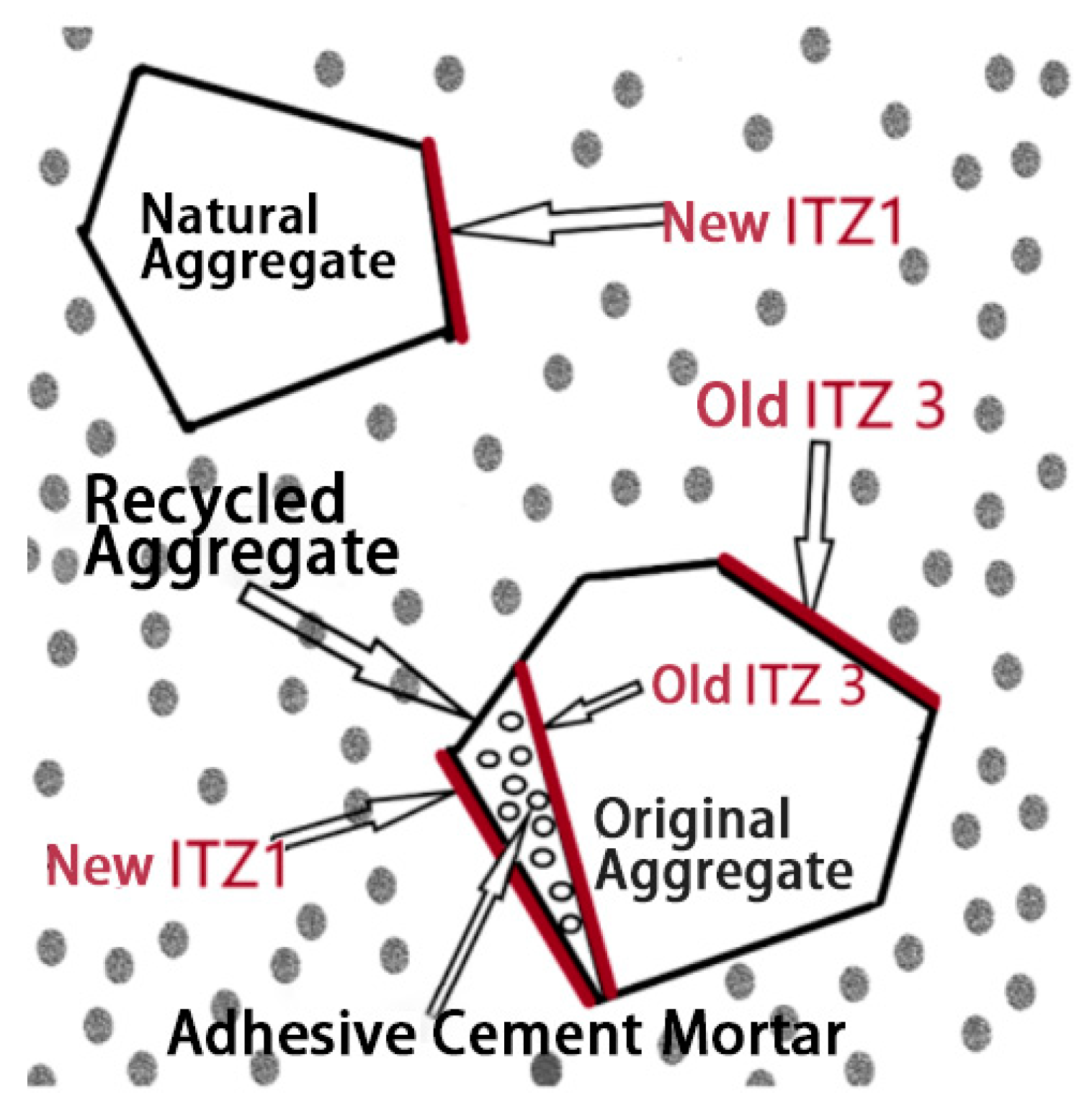

The presence of multiple interface transition zones in recycled aggregates [

25], coupled with their lower strength, can lead to a reduction in concrete's strength, bond with reinforcing steel, and durability, as depicted in

Figure 2. For example, the compressive strength of concrete decreases as the replacement rate of recycled aggregates increases, with a compressive strength of only 55% of regular concrete when 100% of the fine aggregates are replaced with recycled aggregates [

26]. Parameters such as electrical conductivity and chloride ion diffusion coefficient in concrete exhibit linear increases with higher rates of recycled aggregate substitution [

26]. Bao et al. [

14] found that the inclusion of recycled coarse aggregates generally lowered the compressive strength of concrete and increased the transport coefficients of water and chloride ions. Therefore, optimizing mix designs, employing admixtures, and utilizing aggregate modification techniques are necessary to enhance concrete performance. K. Pandurangan et al. studied the factors affecting the bond strength of recycled aggregate concrete by using different treatment methods [

59,

60,

61].

In summary, recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete and natural aggregates exhibit several significant differences in terms of physical properties, chemical properties, mechanical performance, and sustainability. Understanding these differences is of paramount importance for the enhancement of recycled aggregate modification techniques, the judicious utilization of recycled aggregates, the optimization of concrete mix designs, and the improvement of engineering applications.

3. Recycled Concrete Aggregate Modification Techniques

3.1. Physical Modification

Physical enhancement involves applying stress to the adhering mortar layer through mechanical and thermomechanical approaches to detach it, thereby improving the performance of recycled aggregates. Physical enhancement techniques can be categorized into three main types: mechanical grinding and shaping, heat treatment, and electric pulse treatment.

3.1.1. Mechanical Grinding and Shaping

By subjecting waste concrete to mechanical grinding and sieving, the physical properties and particle shape of recycled aggregates can be improved, enhancing their performance in concrete applications. This includes:

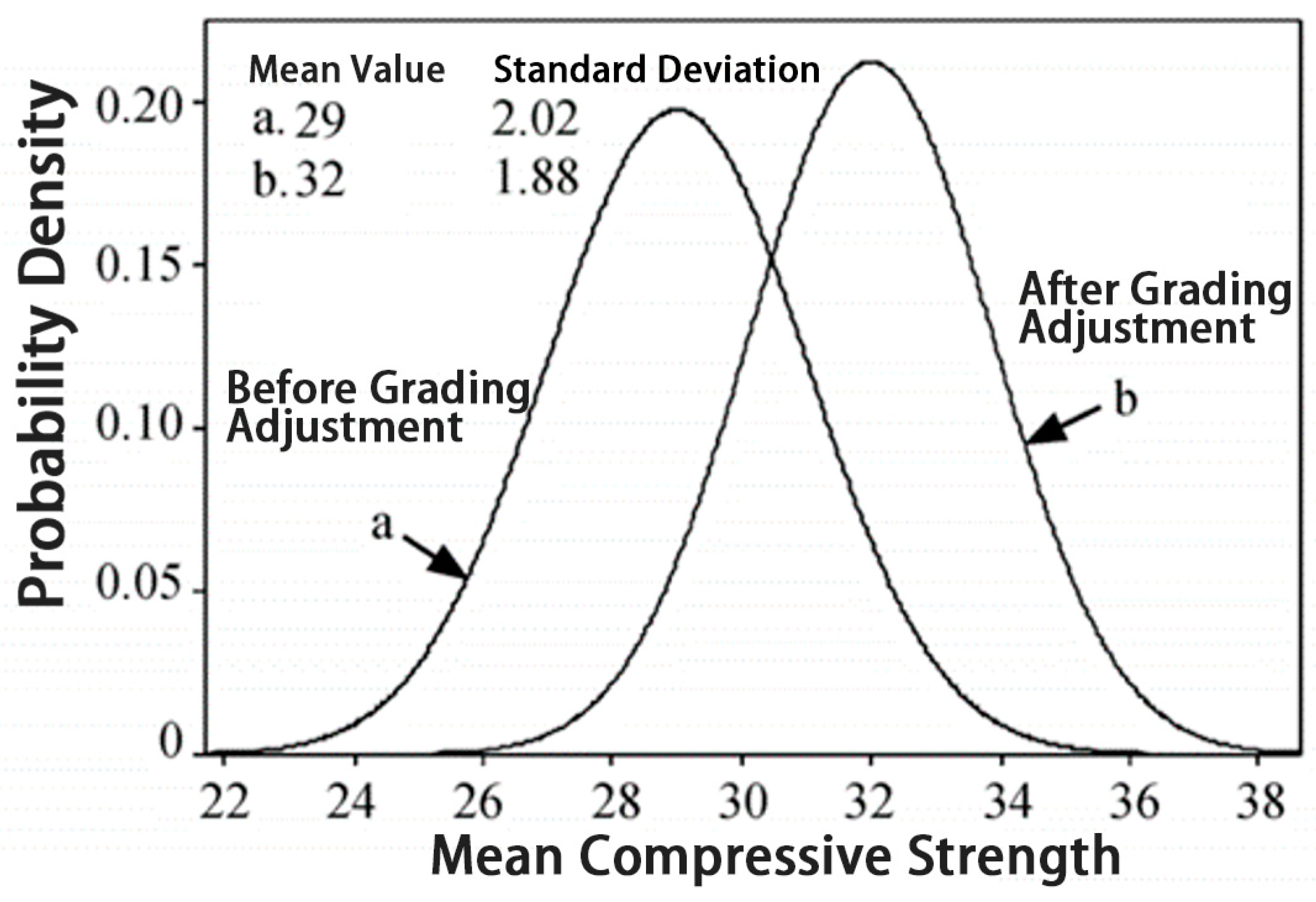

Crushing and Sieving: This is the most fundamental and commonly used method for preparing and processing recycled aggregates. Waste concrete is crushed using crushing equipment, and then crushed concrete is graded and reassembled through sieving equipment to obtain recycled aggregates that meet grading and physical performance requirements. For example, Wang et al. [

30] found that the water absorption of recycled aggregates significantly decreased after sieving to remove aggregates below 4.75 mm and fines. Xiao et al. [

24] noted that adjusting the aggregate grading resulted in a significant reduction in the standard deviation of compressive strength for concrete, with an increase in the mean value, as shown in

Figure 3. This indicates an enhancement in the compressive strength of recycled concrete, along with effective control of performance variability.

- 2.

Air Separation: Air separation is based on the differences in particle size and density within recycled aggregates and relies on the action of wind to segregate particles. Heavier particles are less easily carried by the wind due to inertia, while lighter particles are more prone to being carried away by the wind, achieving particle separation. According to Li Gen [

24], for example, subjected crushed waste concrete particles with a particle size smaller than 4.75mm to 15 minutes of vibration grinding, followed by air separation at a velocity of 16 m/s to obtain recycled fine aggregates that meet the required specifications.

- 3.

Vibration Mixing Pretreatment: Preprocessing recycled aggregates through abrasion and crushing within a concrete mixer can conveniently achieve mechanical grinding and shaping of recycled aggregates. Wang Bo [

29] conducted experiments using two types of mixers (double-shaft mixer and planetary mixer), two mixing speeds (30 r/min and 55 r/min), and two mixing methods (vibration and regular) to mix crushed waste concrete recycled aggregates and discussed their impact on concrete performance.

These mechanical grinding and shaping methods can improve the physical properties and particle shape of recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete, making them more suitable for use in concrete. However, it's notable that the mechanical grinding and shaping process may exacerbate surface damage to recycled aggregates, leading to some performance degradation, such as reduced strength and increased water absorption [

29].

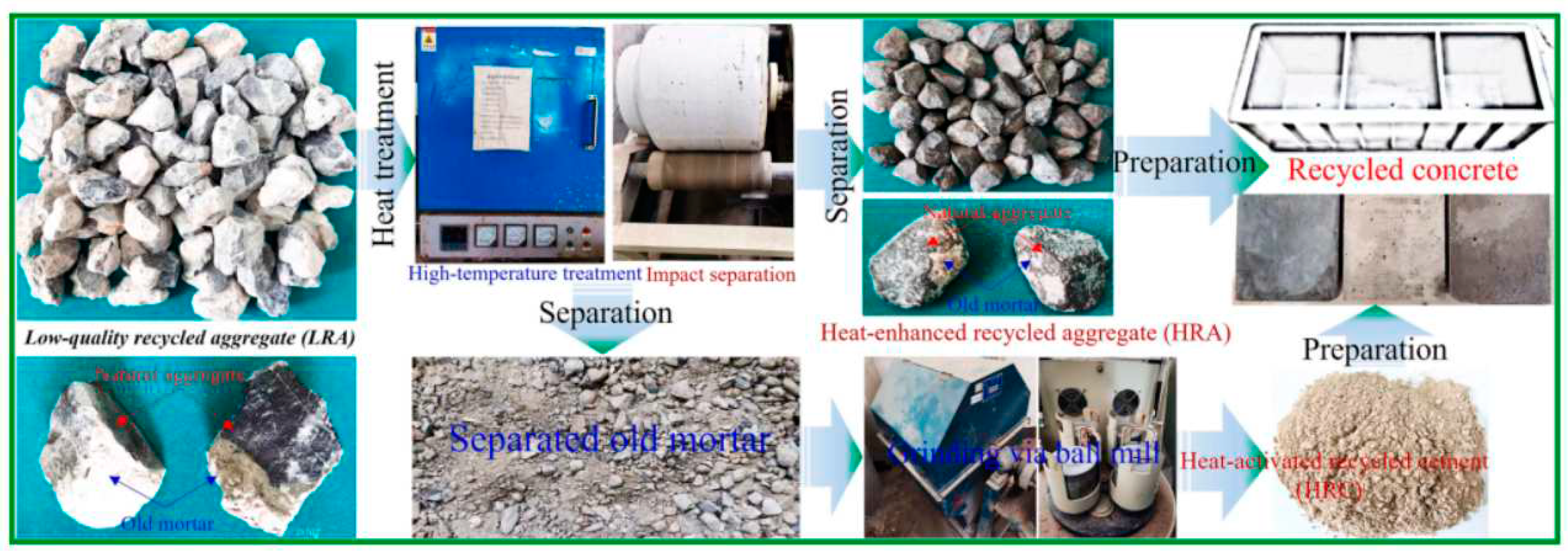

3.1.2. Heat Treatment

Recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete are subjected to high-temperature environments, involving hot air, hot water, steam, or thermal treatment. The application of high temperatures serves to remove cementitious gel and other organic substances from the surface of recycled aggregates, enhancing the cleanliness of their particle surfaces. Simultaneously, high-temperature treatment can improve the particle shape of recycled aggregates, making them more uniform and regular. A typical process flow for preparing concrete using heat-treated recycled aggregates is illustrated in

Figure 4.

However, due to the variability in raw materials for recycled aggregates, differences in particle size, and moisture content, there is no definitive consensus in the literature regarding the optimal heat treatment temperature and regimen, leading to several contradictions. For instance, Li Gen [

31] found that an ascent rate of 10 K/min and a heating temperature of 500°C were the most significant conditions for disrupting the interface transition zone on the surface of recycled coarse aggregates, representing the optimal conditions for removing adhering mortar. On the other hand, Wu et al. [

8] discovered that using a heat treatment of 700°C could transform low-quality recycled aggregates into thermally enhanced recycled aggregates (HRA) as a substitute for natural aggregates and thermally activated recycled cement (HRC) as a substitute for ordinary Portland cement. Furthermore, the high energy consumption associated with heat treatment limits its widespread application.

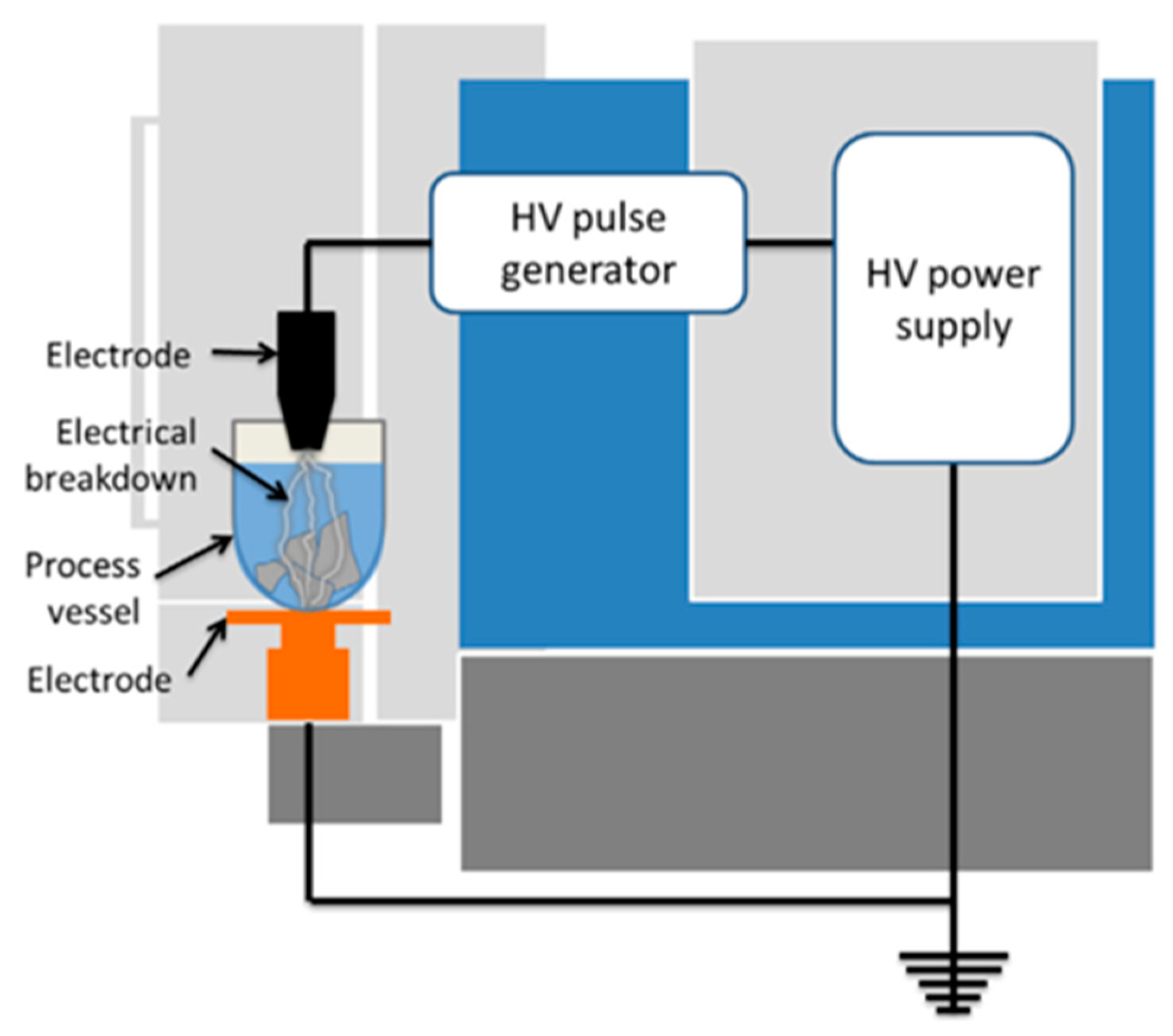

3.1.3. Microwave or Electric Pulse Treatment

The modification method involving microwave or electric pulse treatment of recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete is based on the application of electric pulse or microwave technology. By applying high-voltage electric pulses or microwaves to recycled aggregates, strong electric fields and current effects can be generated, leading to ion migration, electrochemical reactions, and electrothermal effects. These effects can alter the physical structure, surface properties, and chemical composition of recycled aggregates, thereby achieving the modification effect. The typical process for electric pulse treatment of recycled aggregates is illustrated in

Figure 5.

Xiao Jianzhuang et al. [

32] conducted a strengthening test on recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) through low power microwave, and compared with the traditional technology, microwave heating modified recycled coarse aggregate had a better effect. Tsujino et al. [

33] first proposed the new microwave technology for concrete aggregate recovery. Through CO

2 emission test and mechanical property test during the treatment of 1t waste concrete, it was confirmed that compared with traditional recycling methods, the CO

2 content generated in the microwave heating process was lower and the recovered RCA quality was higher. Ong et al. [

34] systematically discussed the possibility of microwave technology in the recycling process of concrete, and discussed the basic working principle of microwave technology in the application of concrete regeneration. Compared with other traditional aggregate extraction technologies, microwave heating combined with mechanical crushing technology can obtain higher RCA quality. It should be noted that due to the lack of relevant theoretical research, microwave technology has not been applied in the field of civil engineering on a large scale. On the one hand, concrete is a complex artificial composite material, and the properties of concrete under microwave are affected by factors such as mix ratio and water content. On the other hand, the mechanism of water migration, pore pressure and thermal stress in concrete under high temperature is still unclear, which greatly limits the popularization and application of microwave technology [

35].

Du Wenping [

36] adopted an experimental research method and used microwave-assisted mechanical picking technology to treat waste concrete blocks, obtain high-quality recycled coarse aggregate, and then prepare recycled concrete to study its compressive properties and failure patterns. The mechanical properties of reclaimed coarse aggregate with high quality were compared with those obtained from natural coarse aggregate and other picking processes, which showed that the microwave assisted mechanical picking process had strong advantages. The damage degree of regenerated coarse aggregate was analyzed from the microscopic point of view by SEM scanning test. The results showed that the coarse aggregate obtained by microwave-assisted mechanical process picking waste concrete blocks had high quality characteristics [

57,

58].

Menard et al. [

37] found that both microwave and electric pulse technologies are effective in removing adhering mortar from the surface of recycled aggregates. Compared to microwave treatment, electric pulse technology has lower energy consumption (1~3 vs. 10~40 kW h t-1), but it can only be used for recycled aggregates immersed in water, posing some challenges for engineering applications. It is important to note that the electric pulse treatment modification method for recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete is still in the research and development stage, and specific treatment parameters and process conditions need further optimization and validation.

3.2. Chemical Modification

3.2.1. Acid Treatment for Adhering Mortar Removal

The acid treatment modification method for recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete is based on the chemical reaction between acidic solutions and recycled aggregates. Commonly used acid wash solutions include hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, acetic acid, phosphoric acid, and others. The basic reaction equations are shown in Equations (1) to (3). These acidic solutions can chemically react with the adhering substances on the surface of recycled aggregates, such as cementitious materials, and pollutants, causing them to dissolve or detach, thus removing surface adherents. The acid treatment modification method for recycled concrete aggregates from waste concrete can effectively remove cementitious materials, pollutants, improve particle shape, increase the active sites and chemical reactivity on the surface of recycled aggregates, and enhance their bonding ability and interaction with the cementitious matrix.

For example, Pan’s research [

1] found that the water absorption of recycled aggregates soaked in 0.2M acetic acid solution for 24 hours decreased by up to 25.5%, and the apparent density and crushing index of all recycled aggregates treated with dilute acetic acid were improved. However, pickling treatment involves the treatment of acidic solutions and waste liquids, which can easily lead to safety and environmental issues, making it difficult to widely apply.

3.2.2. Sodium Silicate Enhancement of Adhering Mortar

The method of sodium silicate enhancement for recycled aggregates is based on the chemical reaction and cementing action between sodium silicate and recycled aggregates. Sodium silicate is an inorganic binder material with excellent adhesion and cementitious properties. During the treatment process, the sodium silicate solution can penetrate the interior of the recycled aggregate particles, react chemically with the cementitious materials inside, form hydration products of the cementitious materials, and create a bond with the cementitious matrix, thus enhancing the recycled aggregates. The basic reaction equation is shown in Equation (4) [

38].

Song et al. [

39] found that after immersion in sodium silicate with a modulus of 2.8, the strength of recycled coarse aggregate increased, water absorption decreased, and the concrete strength increased by more than 50%, indicating a significant modification effect. Sodium silicate can also synergize with other nanomaterials to modify recycled aggregates. For example, Liu et al. [

40] discovered that compared to control samples, the compressive strength and tensile strength of recycled aggregate concrete modified with a combination of sodium silicate and nano-silica increased by 25.3% and 21.1%, respectively, at 56 days. However, the introduction of sodium silicate, which is strongly alkaline, may lead to more severe alkali-aggregate reactions [

38].

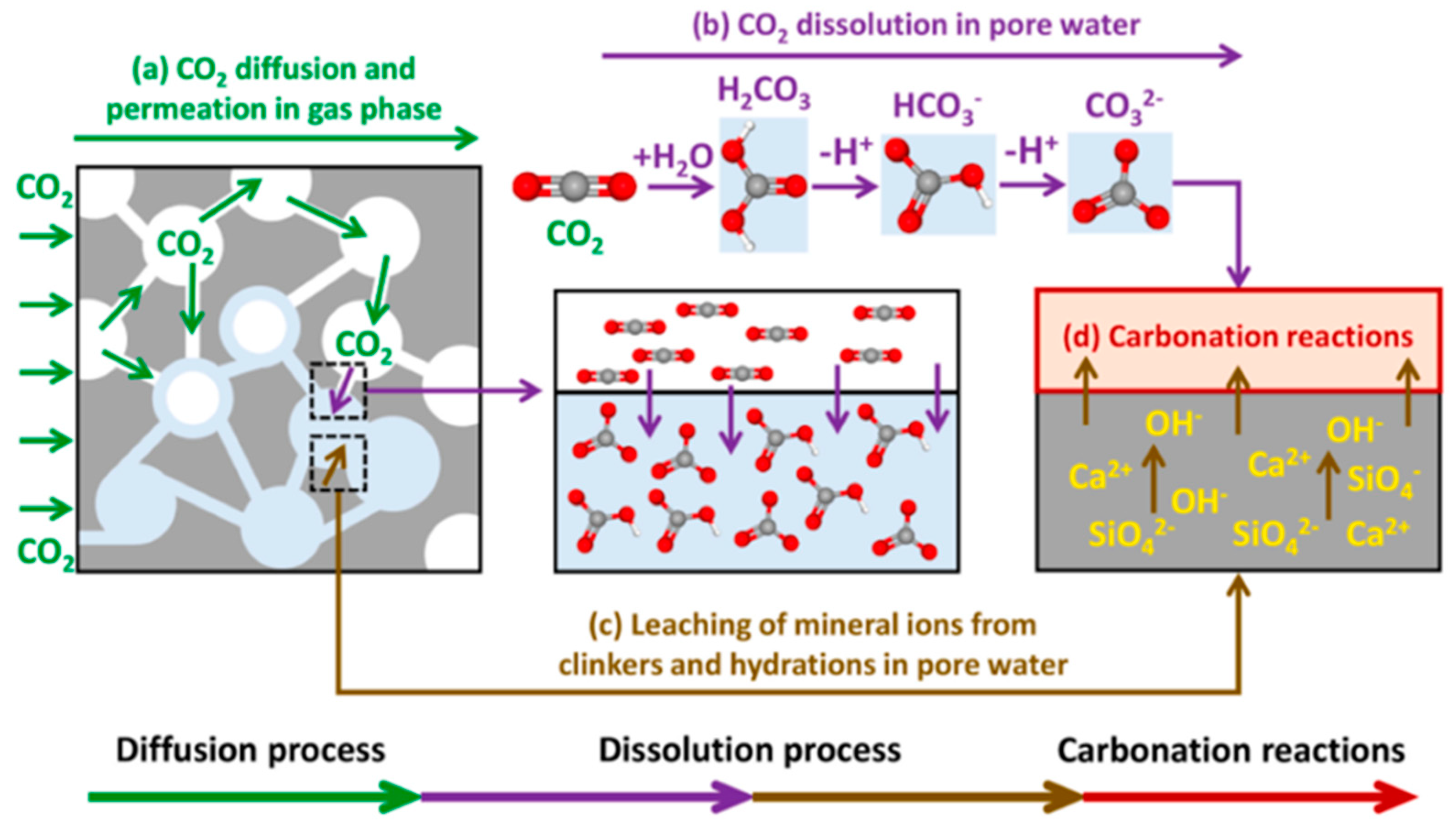

3.2.3. Carbonation Reinforcement of Adhesive Mortar

The carbonation reinforcement method for recycled aggregates is based on the chemical reaction and cementing action between carbonates and the adhesive mortar. In the process, recycled aggregates are typically exposed to carbon dioxide (CO

2), which reacts with carbonates in the gas phase or solution to form a carbonate layer on the surface of recycled aggregates. The basic reaction equations for the oxidation of calcium, the hydration of calcium silicate gel, and the carbonation of ettringite are shown in equations (5) to (7) [

21]. Specifically, the carbonation process is influenced by the characteristics of the parent material of recycled aggregates, including particle size, porosity, moisture content, and the carbonation method and conditions, such as CO

2 concentration, gas pressure, carbonation reaction time, relative humidity, and temperature. The carbonation mechanism of recycled aggregates can be described by the diffusion-dissolution-carbonation reaction process, as shown in

Figure 6 [

27]. The carbonate layer can fill the pores and microcracks on the surface of particles, improving the compactness and strength of recycled aggregates.

Carbonation treatment can improve the shape and surface characteristics of recycled aggregate particles, increase the bonding force between particles, and enhance the compactness and mechanical properties of concrete. For example, after carbonation treatment, the loose bulk density of recycled coarse aggregates increased by 6.9%, and the compacted bulk density increased by 4.9% [

30].

Carbonation strengthening can reduce the pores and microcracks in recycled aggregates, lowering the rate of water absorption and the impact of corrosive media. For instance, the water absorption rate of recycled coarse aggregates decreased by 2.1% after carbonation treatment for 24 hours [

30]. Experimental research by Song et al. [

41] found that when the replacement rate of recycled coarse aggregates was 50%, 75%, and 100%, the chloride ion penetration resistance of carbonation-strengthened recycled aggregate concrete increased by 13.8%, 16.6%, and 11.3%, respectively.

It should be noted that carbonation strengthening of recycled aggregates requires control of conditions such as CO2 concentration, pressure, addition of calcium hydroxide, and aggregate particle size to ensure the appropriate carbonation reaction and strengthening effect.

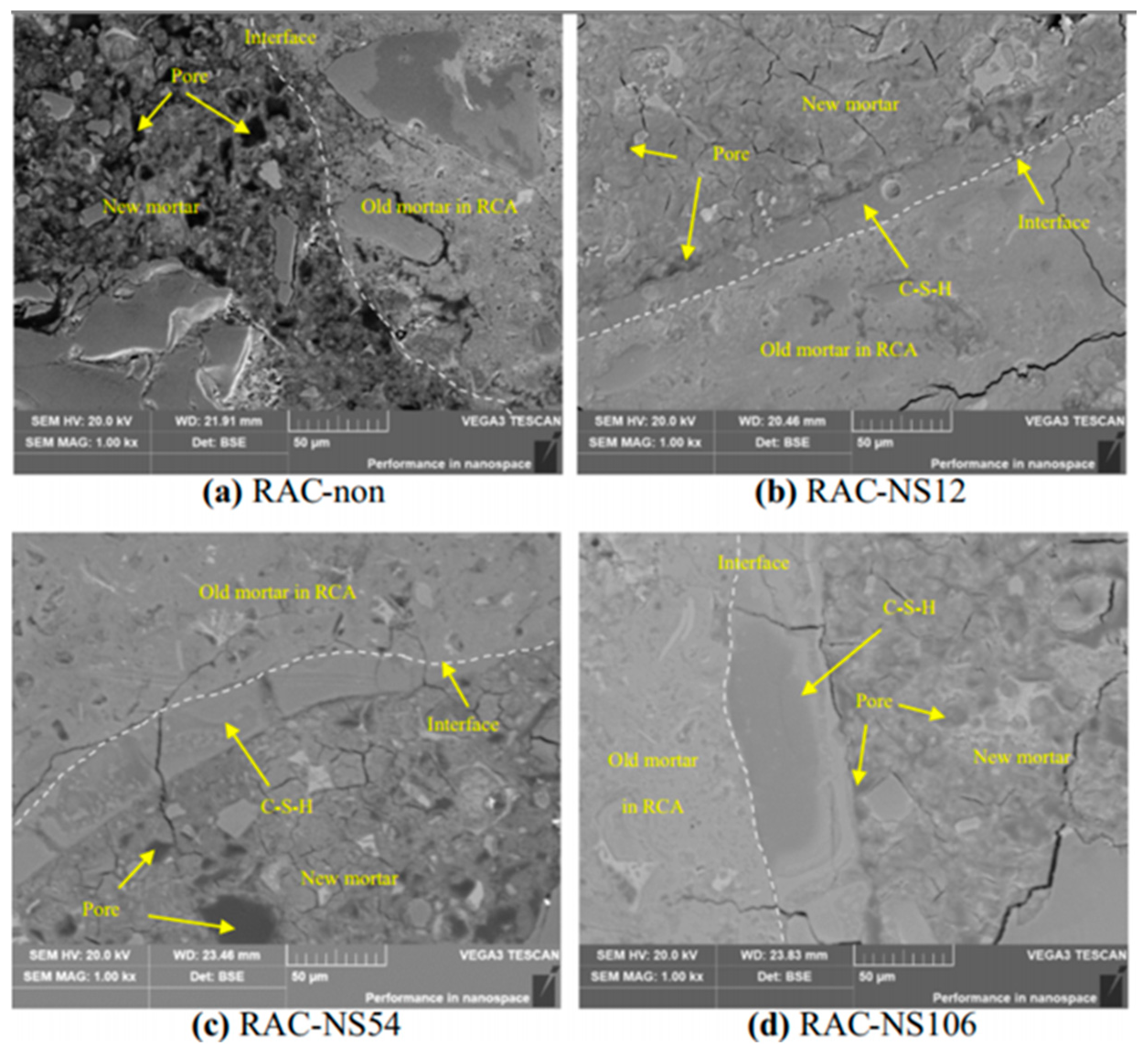

3.2.4. Strengthening Recycled Aggregates with Inorganic Slurries such as Cement, Mineral Admixtures, and Nanomaterials

Basic Principle: The method of strengthening recycled aggregates with inorganic slurries such as cement, mineral admixtures, and nanomaterials is based on the cementitious reaction and encapsulation between them. During the treatment process, recycled aggregates usually come into contact with the slurry, and particles of cement, mineral admixtures, or nanomaterials react with the surface of recycled aggregates through hydration or pozzolanic reactions, forming a gel or encapsulation layer. This process can fill the pores and microcracks on the particle surface and the new interfacial transition zone, as shown in the BSE image in

Figure 7 [

42], thereby enhancing the compactness and strength of the recycled aggregates [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47].

Cement slurry reinforcement treatment can create a dense cement gel layer or coating on the surface of recycled aggregates, filling the pores and micro-cracks on the particle surface, thus enhancing the compressive strength of concrete. Wang et al. [

48] used the cement slurry wrapping method and secondary mixing process to strengthen recycled coarse aggregates, and the 28-day compressive strength of C20, C30, and C40 recycled concrete reached 98%, 91%, and 97% of that of ordinary concrete. After modifying recycled coarse aggregates with sprayed colloidal silica ash, the compressive strength and elastic modulus of the corresponding recycled concrete increased by 9.2% and 11.7%. Its durability even approached that of natural aggregate concrete. The secondary water absorption rate, charge transfer value, and carbonation depth decreased by 66.3%, 46.1%, and 28.4% [

42].

Improved Particle Shape: Strengthening treatment can improve the shape and surface characteristics of recycled aggregate particles, increasing the bulk density. For example, after soaking in 2wt.% and 4wt.% colloidal silica solutions, the loose bulk density of recycled coarse aggregates increased by 15.6% and 18.6% [

30].

Cement, mineral admixtures, and nanomaterial slurry reinforcement treatment can reduce the pores and micro-cracks in recycled aggregates, reduce the rate of water and chloride ion penetration, and improve the durability and impermeability of concrete. For instance, after soaking in 2wt.% and 4wt.% colloidal silica solutions, the water absorption rate of recycled coarse aggregates decreased by 3.65% and 4.67% [

30].

It should be noted that the cement, mineral admixtures, and nanomaterial reinforcement treatment of recycled aggregates require control of the slurry's proportions, treatment time, and environmental conditions to ensure appropriate curing reactions and reinforcement effects. Additionally, recycled aggregates treated with cement slurry reinforcement need to undergo proper screening and processing to achieve the required particle grading.

3.2.5. Polymer Reinforcement of Recycled Aggregates

Polymer reinforcement of recycled aggregates is based on the interaction and encapsulation between polymer materials and recycled aggregates. During the treatment process, recycled aggregates typically come into contact with a polymer solution or molten polymer, and polymer materials interact with the surface of the recycled aggregates through adsorption, penetration, or encapsulation. This interaction can improve the surface properties of recycled aggregates and the bond between particles, enhancing their mechanical performance and stability.

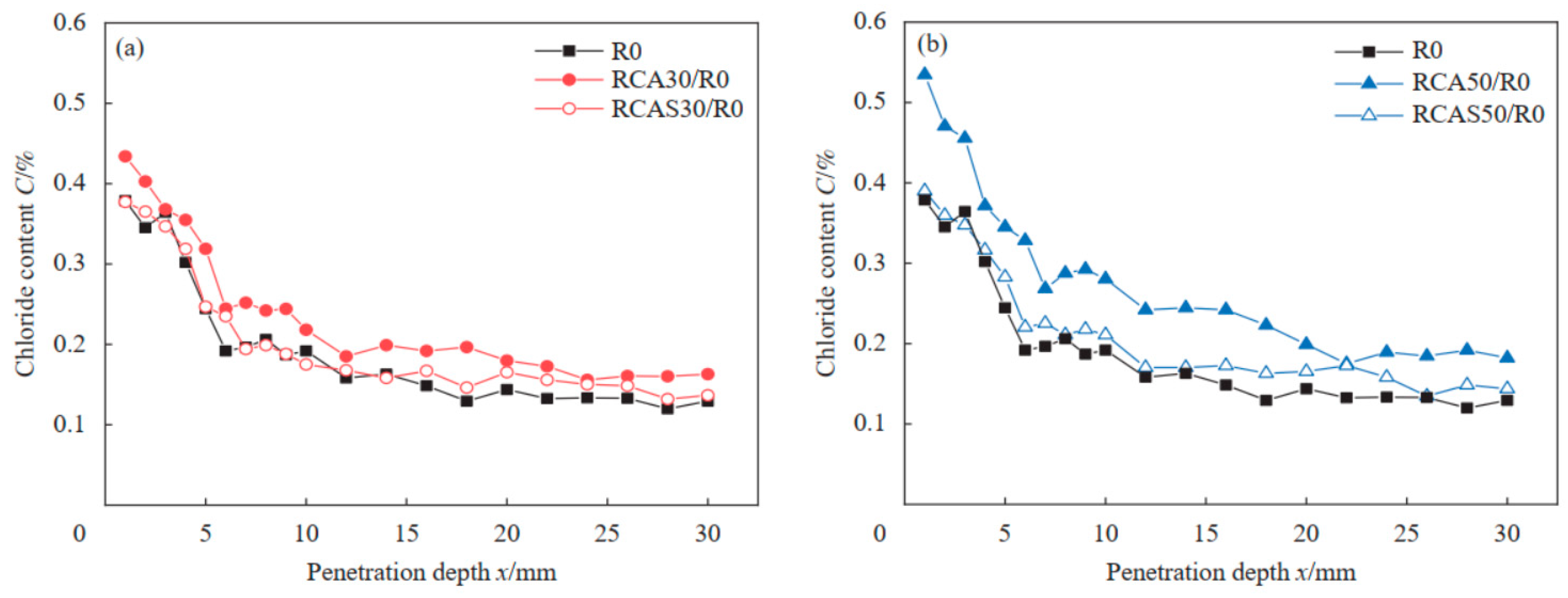

Bao et al. [

20] found that after silane impregnation treatment, the water absorption rate of recycled coarse aggregates was effectively controlled, resulting in a significant improvement in the chloride ion permeability of the prepared concrete. The internal chloride ion content of C30 and C50 recycled concrete was significantly reduced, approaching that of ordinary concrete, as shown in

Figure 8. Li [

49] found that water-based epoxy and styrene-butadiene latex modified recycled coarse aggregates improved the compressive and flexural strength of pervious bricks and improved their permeability. Song et al. [

39] found that a 20% concentration of polyaluminum sulphate had a strengthening effect on the strength and water absorption of recycled coarse aggregates from waste concrete. The concrete strength increased by approximately 30%, and durability also improved, although the overall effect was slightly inferior to that of sodium silicate treatment. Additionally, some studies have found that polymer-treated recycled aggregates may lead to a slight reduction in concrete strength [

20].

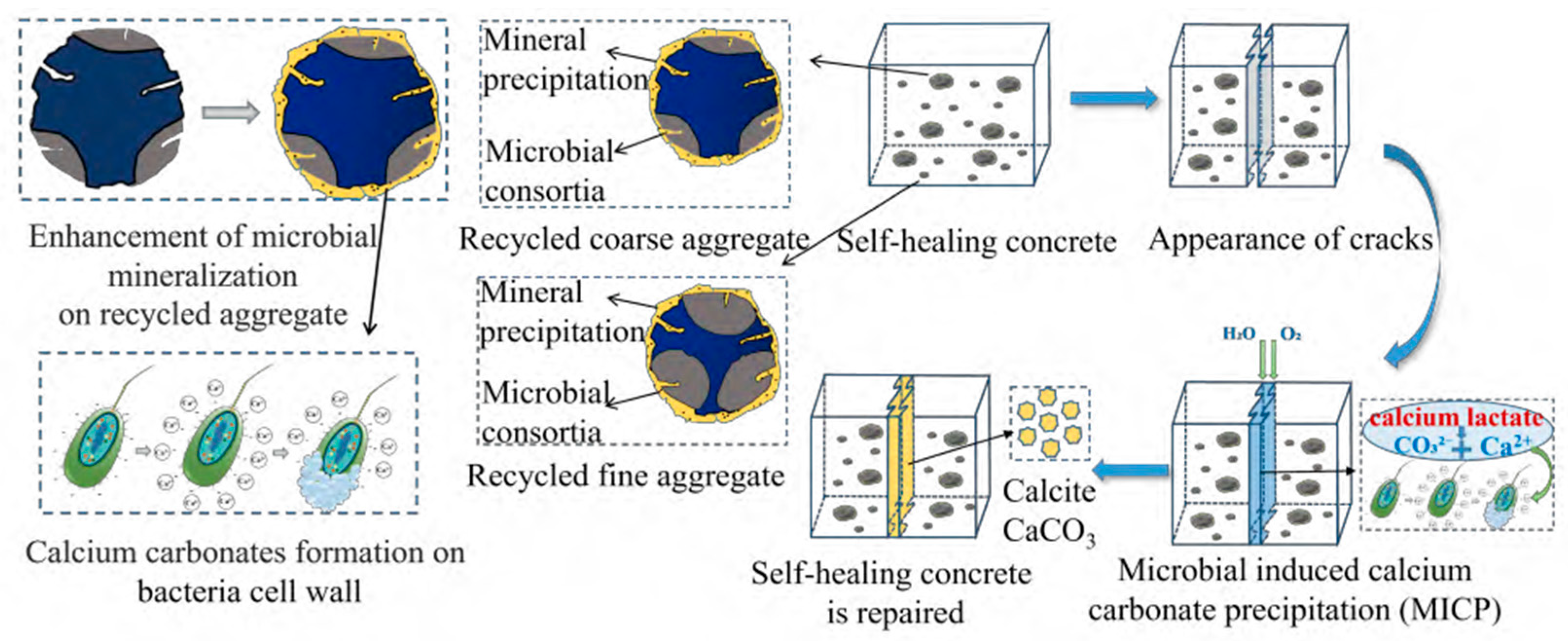

3.3. Microbial-Induced Carbonate Precipitation Modification

Microbial-Induced Carbonate Precipitation (MICP) is a method used for enhancing recycled aggregates, based on the metabolic activity of specific microorganisms, with the most used microorganisms being urease-producing bacteria (such as urease-producing Bacillus). During the treatment process, recycled aggregates contact with a solution containing urea and a source of calcium. Microorganisms metabolize urea, breaking it down into ammonia and carbon dioxide. Ammonia reacts with calcium ions in the solution to generate calcium carbonate. Subsequently, calcium carbonate precipitates on the surface of the recycled aggregates, forming calcium-rich cementitious material that fills the pores and microcracks on the particle surface, thereby enhancing their mechanical properties and stability. The principle of microbial mineralization for repairing cracks in recycled aggregates is shown in

Figure 9. MICP can improve compressive strength, enhance particle shape, and increase durability. Moreover, it is environmentally friendly, with low energy consumption and minimal environmental impact.

For instance, the research conducted by Zhang et al. [

51] indicates that Bacillus spores of cocci bacteria-induced calcium carbonate deposition has a favourable strengthening effect on recycled coarse aggregates. The crushing index and water absorption significantly decrease, while the apparent density increases. The optimal strengthening effect is achieved at 10 days. It's important to note that microbial-induced carbonate precipitation for enhancing recycled aggregates requires control over the microbial growth conditions, the concentrations of urea and calcium sources, and the treatment duration to ensure appropriate carbonate deposition and strengthening effects. Hua Sujin et al. [

50] discovered that using a mixed culture of microorganisms for enhancing recycled aggregates can yield good enhancement results. After 28 days of repair, the average crack width in the concrete and the complete repair rate reach 0.28 millimetres and over 60%. This represents an improvement of over 47.4% and 50%, compared to regular concrete without microbial-induced mineralization for crack repair. Furthermore, the water permeability coefficient of the repaired concrete decreases by over 99.7%, demonstrating better waterproofing performance.

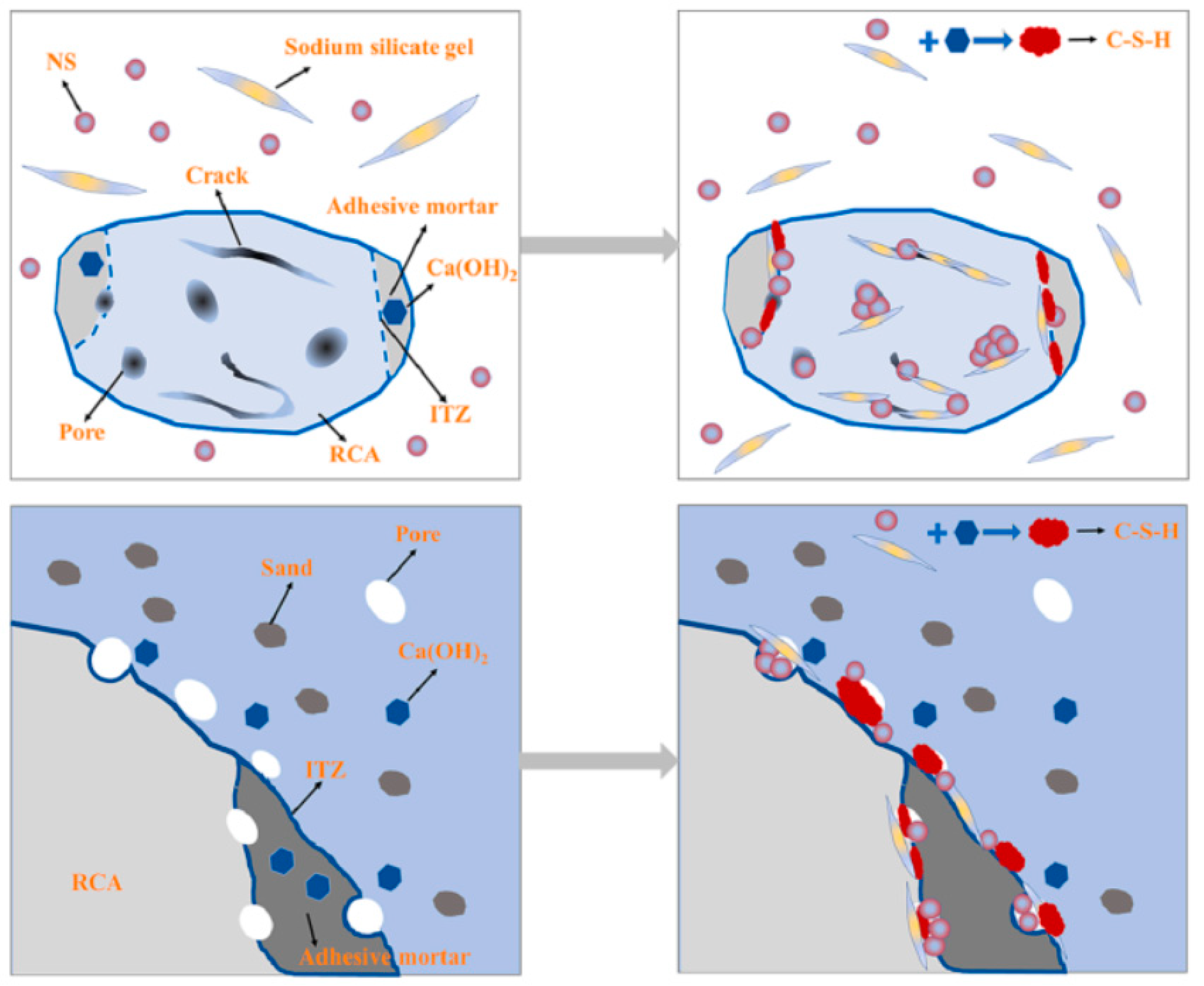

It's notable that the combination of the above methods is often used to achieve better results. Therefore, flexibility in combining these methods is recommended for practical applications. For example, Xue [

52] found that the combination of sodium silicate enhancement and cement-based penetrating crystalline material slurry pre-wetting is optimal for enhancing recycled coarse aggregates to prepare concrete with improved resistance to chloride ion penetration and freeze-thaw resistance. The principle of the sodium silicate and nano silica co-modification of recycled aggregates is illustrated in

Figure 10. Specifically, nano silica (NS) and sodium silicate can penetrate into the interior of the recycled coarse aggregates through microcracks and strengthen the microstructure of the old interfacial transition zone (ITZ). During the formation of the new ITZ, NS and sodium silicate can enter the interior of the recycled coarse aggregates through microcracks and react with calcium hydroxide, converting it into C-S-H gel, thereby enhancing the ITZ. Modified recycled aggregate concrete has a relatively higher degree of hydration, improved pore structure, and increased strength and durability of recycled concrete.

4. Conclusion and Outlook

The research shows that the production and recovery process of recycled aggregate will be accompanied by high energy consumption, a lot of dust pollution and other problems, and the quality of recycled aggregate produced is not high, poor adaptability[

53,

54,

55,

56].The existing physical, chemical, and biological techniques for enhancing recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) have made some progress in improving the performance of RCA. However, there are still some common problems and challenges, including:

Consistency of Enhancement Effects: The physical and chemical properties of RCA may vary significantly due to differences in the source materials, leading to inconsistent enhancement effects reported in the literature. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct in-depth research into the changes in the properties of RCA and the mechanisms of enhancement to achieve more stable enhancement effects for practical engineering applications.

Compatibility of Composite Materials: The compatibility between RCA and enhancement materials (such as polymers, microorganisms, etc.) is a crucial issue. Researchers need to explore the interactions between suitable enhancement materials and RCA to improve the performance and stability of composite materials.

Long-Term Performance and Durability: While RCA enhancement techniques can improve mechanical properties in the short term, long-term performance and durability, especially at the component level, still need further investigation. Researchers should focus on the aging of materials, fatigue performance, and durability of RCA after enhancement to ensure their reliability in real-world engineering applications.

Feasibility for Large-Scale Applications: RCA enhancement techniques need to be economically feasible and scalable for large-scale applications. Therefore, researchers should consider the scalability, cost-effectiveness, and practical implementation of enhancement techniques to promote their widespread adoption in real engineering projects.

The future research directions of recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) enhancement may encompass the following areas:

In-Depth Investigation of Enhancement Mechanisms: Further research should delve into the mechanisms underlying RCA enhancement techniques. This includes studying the interactions between enhancement materials and RCA, the formation mechanisms of enhancement effects, and other fundamental principles and influencing factors.

Development of Novel Enhancement Materials: Exploration of novel enhancement materials such as nanomaterials, fiber materials, and bio-based materials to improve the performance and stability of RCA. These materials may offer improved compatibility, enhanced effects, and greater environmental friendliness.

Integration of Multi-Functional Enhancement Techniques: Integration of various RCA enhancement techniques to create multi-functional enhancement systems. For instance, combining polymer reinforcement with microbial-induced carbonate precipitation techniques to achieve a more comprehensive enhancement of RCA.

Sustainability and Environmental Impact Assessment: Comprehensive sustainability assessments of RCA enhancement techniques, considering aspects like resource utilization, energy consumption, and environmental impacts. Additionally, research is needed to assess the potential environmental and human health impacts of RCA enhancement techniques.

In summary, future research efforts should be dedicated to addressing the challenges associated with RCA enhancement techniques and promoting their feasibility and sustainability in practical engineering applications. This will contribute to enhancing the performance of recycled concrete aggregates, advancing sustainable construction, and promoting the recycling of resources.

References

- Pan Z. Fundamental And Application Research On The Utilization Of Acetic Acid Modified Recycled Aggregate [D]. Southeast University,2019.

- Huang J. Study On The Fundamental Characteristics Of Setting Retardant And Shrinkage-Reducing Type Ofalkali-Activated Slag Recycled Concrete[D]. Harbin Institute of Technology, 2022.

- Ge X. Research on Application of Salvaged Materials and Regenerative Materials in the Context of Resource-efficient Landscape[D]. Beijing Forestry University, 2014.

- Zhang W., Yuan Z., Li D., et al. Mechanical and vegetation performance of porous concrete with recycled aggregate in riparian buffer area[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022, 332: 130015.

- Wang C., Xiao J., Qi C., et al. Rate sensitivity analysis of structural behaviors of recycled aggregate concrete frame[J]. Journal of Building Engineering. 2022, 45: 103634.

- Gao D., Yan H., Yang L., et al. Analysis of bond performance of steel bar in steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber reinforced concrete with partially recycled coarse aggregates[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022, 370: 133528.

- Yan H., Gao D., Guo A., et al. Monotonic and cyclic bond responses of steel bar with steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2022, 327: 127031.

- Wu H., Liang C., Zhang Z., et al. Utilizing heat treatment for making low-quality recycled aggregate into enhanced recycled aggregate, recycled cement and their fully recycled concrete[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2023, 394: 132126.

- Hosseinnezhad H., Sürmelioğlu S., çakır Ö A., et al. A novel method for characterization of recycled concrete aggregates: Computerized microtomography[J]. Journal of Building Engineering. 2023, 76: 107321.

- Younis K. H. Influence of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) molarity on fresh properties of self-compacting slag-based geopolymer concrete containing recycled aggregate[J]. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021.

- Nematzadeh M., Nazari A., Tayebi M. Post-fire impact behavior and durability of steel fiber-reinforced concrete containing blended cement–zeolite and recycled nylon granules as partial aggregate replacement[J]. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering. 2021, 22(1): 5.

- Munir M. J., Kazmi S. M. S., Wu Y., et al. Development of a unified model to predict the axial stress–strain behavior of recycled aggregate concrete confined through spiral reinforcement[J]. Engineering Structures. 2020, 218: 110851.

- Feng C., Huang Y., Cui B., et al. Research Progress on Treatment Methods of Building Recycled Concrete Aggregates[J]. Material Introduction. 2022, 36(21): 84-91.

- Bao J., Li S., Zhang P., et al. Influence of the incorporation of recycled coarse aggregate on water absorption and chloride penetration into concrete[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2020, 239: 117845.

- Khaliq W., Taimur. Mechanical and physical response of recycled aggregates high-strength concrete at elevated temperatures[J]. Fire safety journal. 2018, 96: 203-214.

- Wang C., Xiao J. Evaluation of the stress-strain behavior of confined recycled aggregate concrete under monotonic dynamic loadings[J]. CEMENT & CONCRETE COMPOSITES. 2018, 87: 149-163.

- Li J., Yang E. Macroscopic and microstructural properties of engineered cementitious composites incorporating recycled concrete fines[J]. Cement and Concrete Composites. 2017, 78: 33-42.

- Zhao G., Zhu Z., Ren G., et al. Utilization of recycled concrete powder in modification of the dispersive soil: A potential way to improve the engineering properties[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2023, 389: 131626.

- Ye T., Xiao J., Duan Z., et al. Geopolymers made of recycled brick and concrete powder – A critical review[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2022, 330: 127232.

- Bao J., Li S., Zhang P., et al. Effect of recycled coarse aggregate after strengthening by silane impregnation on mass transport of concrete [J]. Journal of Composite Materials. 2020, 37(10): 2602-2609.

- Feng C., Cui B., Huang Y., et al. Enhancement technologies of recycled aggregate – Enhancement mechanism, influencing factors, improvement effects, technical difficulties, life cycle assessment[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2022, 317: 126168.

- Wang C., Xiao J., Li C. Strain rate effect analysis on characteristic parameters of restoring force for recycled aggregate concrete frame structures [J] Journal of Civil Engineering 2021, 54 (08): 24-36.

- Wang C., Xiao J., Li Q. Experimental study on mechanical behavior of confined recycled aggregate concrete under cyclic loadings [J] Journal of Building Structures 2020, 41 (S2): 436-442.

- Xiao J., Lin Z., Zhu J. Effects of Recycled Aggregates' Gradation on Compressive Strength of Concrete [J] Journal of Sichuan University (Engineering Science Edition) 2014, 46 (4): 154-160.

- Xiao J., Li W., Sun Z., et al. Properties of interfacial transition zones in recycled aggregate concrete tested by nanoindentation[J]. Cement and Concrete Composites. 2013, 37: 276-292.

- Duan Z., Hou S., Pan Z., et al. Rheology of recycled fine aggregate concrete and its effect on strength and durability [J] Journal of Building Structures 2020, 41 (S2): 420-426.

- Zhang T., Chen M., Wang Y., et al. Roles of carbonated recycled fines and aggregates in hydration , microstructure and mechanical properties of concrete: A critical review[J]. CEMENT & CONCRETE COMPOSITES. 2023, 138.

- Xie T., Zhao X. Can a local bond test truly reflect impact of recycled aggregate on the bond between deformed steel bars and recycled aggregate concrete?—A critical assessment and development of a generic model[J]. Engineering Structures. 2021, 244: 112826.

- Wang B. Effect of Vibration Mixing on Attrition and Cleavage of Recycled Aggregate and Performance of Recycled Aggregate Concrete[D]. Chang'an University, 2019.

- Wang Y., Li R., Zhu C., et al. Influence of strengthening treatment on physical properties of recycled coarse aggregate [J] Concrete 2021 (2): 82-85.

- Li G., Research on the preparation technology of high-quality recycled aggregate and the activation of cement stone powder [D] Kunming University of Science and Technology, 2016.

- Xiao Jianzhuang, Wu Lei, Fan Yuhui. Modification test of recycled coarse aggregate by microwave heating[J].Concrete,2012(7):55–57.

- Tsujino M, Noguchi T, Kitagaki R, et al. Completely recyclable concrete of aggregate-recovery type by a new technique using aggregate coating[J].Journal of Structural and Construction Engineering,2010,75(647):17–24.

- Ong K C G, Akbarnezhad A. Microwave-assisted concrete technology[M]. Boca Raton:CRC Press,2015:129–167.

- Shao Zhushan, Zhang Pengju, Wei Wei, et al. Influence of moisture content on concrete mechanical properties under microwave irradiation[J].Advanced Engineering Sciences,2021,53(6):93–102.

- Du Wenping. Research on selection technology of high quality recycled concrete aggregate[D].Xi’an:Xi’an University of Science and Technology,2017.

- Menard Y., Bru K., Touze S., et al. Innovative process routes for a high-quality concrete recycling[J]. Waste Management. 2013, 33(6): 1561-1565.

- Ma S., Niu Z., Liu Y., et al. Research Progress on Performance Enhancement of Recycled Aggregate from Construction Waste [J] Journal of Building Science and Engineering 2022, 39 (6): 1-13.

- Song X., Bai C. Effect of Chemical Enhancing Agents on the Properties of Recycled Aggregate and Recycled Concrete[J] Silicate notification 2019, 38 (6): 1748-1754.

- Liu X., Xie X., Liu R., et al. Research on the durability of nano-SiO2 and sodium silicate co-modified recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) concrete[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2023, 378: 131185.

- Song B., Yan H., Cui H., et al. Influence of Carbonation on Chloride Ion Penetration Resistance of CO2 Modified Recycled Aggregate Concrete [J] Material Introduction 2023, 37 (S1): 147-150.

- Li L., Xuan D., Chu S.H., et al. Modification of recycled aggregate by spraying colloidal nano silica and silica fume[J]. Materials and Structures. 2021, 54(6).

- Wang Y., Zhang X., Fang J., et al. Mechanical Properties of Recycled Concrete Reinforced by Basalt Fiber and Nano-silica[J]. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering. 2022, 26(8): 3471-3485.

- Sahu A., Dey T., Chakraborty S. Influence of Nano Silica on Mechanical and Durability Characteristic of Mortar made by Partial Replacement of Natural Fine Aggregate with Recycled Fine Aggregate[J]. Silicon. 2021, 13(12): 4391-4405.

- Sadeghi-Nik A., Berenjian J., Alimohammadi S., et al. The Effect of Recycled Concrete Aggregates and Metakaolin on the Mechanical Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete Containing Nanoparticles[J]. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering. 2019, 43(S1): 503-515.

- Reddy N. S., Lahoti M. A succinct review on the durability of treated recycled concrete aggregates[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2023, 30(10): 25356-25366.

- Hosseini P., Booshehrian A., Madari A. Developing Concrete Recycling Strategies by Utilization of Nano-SiO2 Particles[J]. Waste and Biomass Valorization. 2011, 2(3): 347-355.

- Wang L., Chen Y., Pan W., et al. Effects of manufacture technology on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete [J] Concrete. 2011 (6): 162-164.

- Li P. Properties study of polymer modified permeable bricks of recycled aggregate [J] New building materials .2018, 45 (2): 137-140.

- Hua S., Zhang J., Gao P., et al. Self-healing of concrete cracks by immobilizing non-axenic bacteria with enhanced recycled aggregates [J] Journal of Composite Materials.2023: 1-13.

- Zhang J., Chen P., Xu H., et al. Experimental study on the behavior of recycled aggregates strengthened by microbial induced carbonate precipitation [J] Journal of Zhejiang University of Technology (Natural Science Edition). 2020, 43 (01): 122-129.

- Xue L. Research on Key Problems of Recycled Concrete Application in Northern Marine Environment [D] Dalian University of Technology, 2021.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196.

- Makul N, Rattanadecho P, Agrawal D K. Applications of microwave energy in cement and concrete—A review[J].Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews,2014,37:715–733.

- Kim K H, Cho H C, Ahn J W. Breakage of waste concrete for liberation using autogenous mill[J].Minerals Engineering,2012,35:43–45.

- Hu Zhichun, Li Guoxin, Ouyang Mengxue. Research progress of waste concrete recycling[J].Commercial Concrete,2016(1):30–32.

- Tsujino M, Noguchi T, Tamura M, et al. Application of conventionally recycled coarse aggregate to concrete structure by surface modification treatment[J].Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology,2007,5(1):13–25.

- Dai Jun, Li Chuanjing, Yang Fan, et al. Effect of different moisture content on weakening strength of rock under microwave irradiation[J].Water Power,2018,40(1):31–34.

- Lu Gaoming, Li Yuanhui, Hassani F, et al. Experimental and theoretical research progress of microwave assisted mechanical rock breaking[J].Chinese Journal of Geotechnical Engineering,2016,38(8):1497–1506.

- K. Pandurangan, A. Dayanithy, S. Om Prakash. Influence of treatment methods on the bond strength of recycled aggregate concrete[J]. Construction and Building Materials,2016(120): 212-221.

- S. Laserna, J. Montero. Influence of natural aggregates typology on recycled concrete strength[J]. Construction and Building Materials, 2016(115): 78-86.

- P. Saravanakumar, K. Abhiram, B. Manoj. Properties of treated recycled aggregates andits influence on concrete strength characteristics[J]. Construction and Building Materials,2016(111): 611-617.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).