1. Introduction

Extensive efforts have been devoted to advancing lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) due to their superior energy density, prolonged cyclic lifespan, and eco-friendliness [1-3]. However, the demand for LIBs with higher energy density in practical applications necessitates exploring alternative anode materials [4, 5]. Transition-metal-oxide (TMO)-based anodes, such as ZnO, have gained attention due to their high theoretical capacity and low costs. Despite its advantages, bulk ZnO faces challenges of sluggish kinetics and poor cycling stability which primarily due to volumetric expansion during lithiation and delithiation processes [6-8].

To address these limitations, researchers have explored strategies including morphology control and nanostructure design. Nanoscale structural design plays a pivotal role in achieving optimal anode performance by mitigating volume expansion and shortening the electron transfer path [9-11]. Increasing the surface area and pore density of anode materials promotes enhanced contact between the electrolyte and anode, facilitating the formation of a stable solid electrolyte interface (SEI) and improving electrochemical properties [12-14]. Additionally, integrating carbon-based materials like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) with ZnO anodes has been shown to enhance electrochemical performance by forming an electron conductive network and providing a cushion against volume expansion [

15].

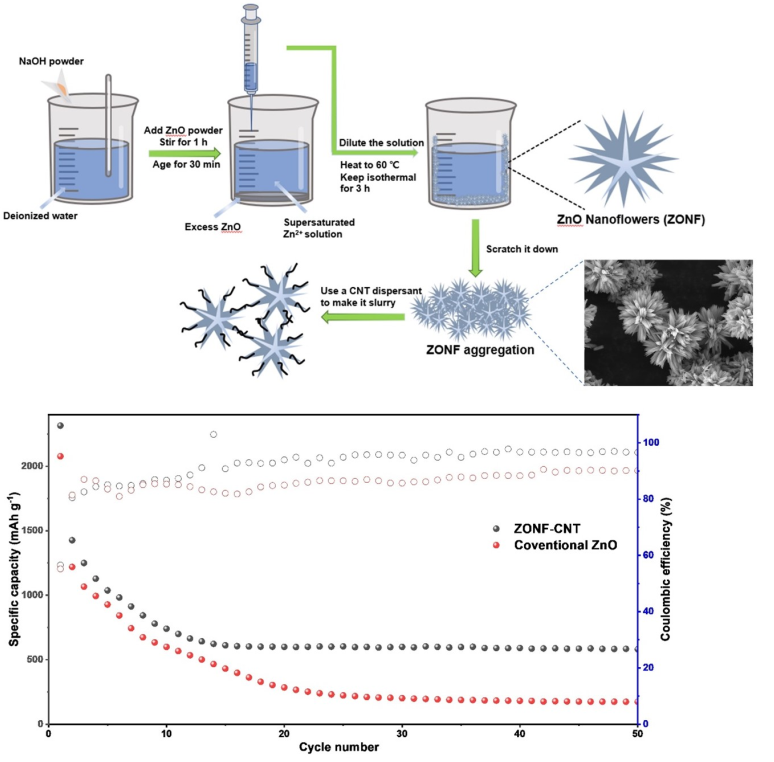

However, the synthesis of ZnO nanostructures has relied on complex methods, and the preparation of composite anodes poses challenges for commercialization. In this study, we present a facile two-step dilution crystallization method for synthesizing hierarchical ZnO nanoflowers (ZONFs) at a low temperature. The ZONFs are combined with CNT dispersants to in-situ form the ZONF-CNT composite, offering a simplified approach compared to conventional methods. The flower-like morphology enhances the contact area between the anode and electrolyte, promoting a stable SEI and favorable cyclic performance. The inclusion of CNTs dispersants prevents aggregation and improves cyclic stability. Moreover, the presence of CNTs establishes an electrically conductive network, enhancing the charge transfer. Overall, the ZONF-CNT composite demonstrates exceptional electrochemical performance, making it highly desirable for efficient energy storage devices.

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should be carefully reviewed and key publications cited. Please highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions. As far as possible, please keep the introduction comprehensible to scientists outside your particular field of research. References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [

1] or [

2,

3], or [

4,

5,

6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

3. Results

The crystal structure of the ZONFs was investigated by the powder XRD (

Figure 1(b)). All the main peaks are well agreed with the Bragg’s reflections of the standard wurtzite ZnO structure (JCPDS Card No.36-1451) with lattice constants a = b = 3.24 Å and c = 5.21 Å

17. To further confirm the structure of the as-prepared sample, the Raman spectroscopy was conducted, as shown in

Figure 1(c). The major peaks are mainly in the range from 250 to 500 cm

-1 with a characteristic peak located at about 438 cm

-1 that is ascribed to the E

2 vibration of ZnO, verifying the hexagonal structure of as-prepared powders [

18].

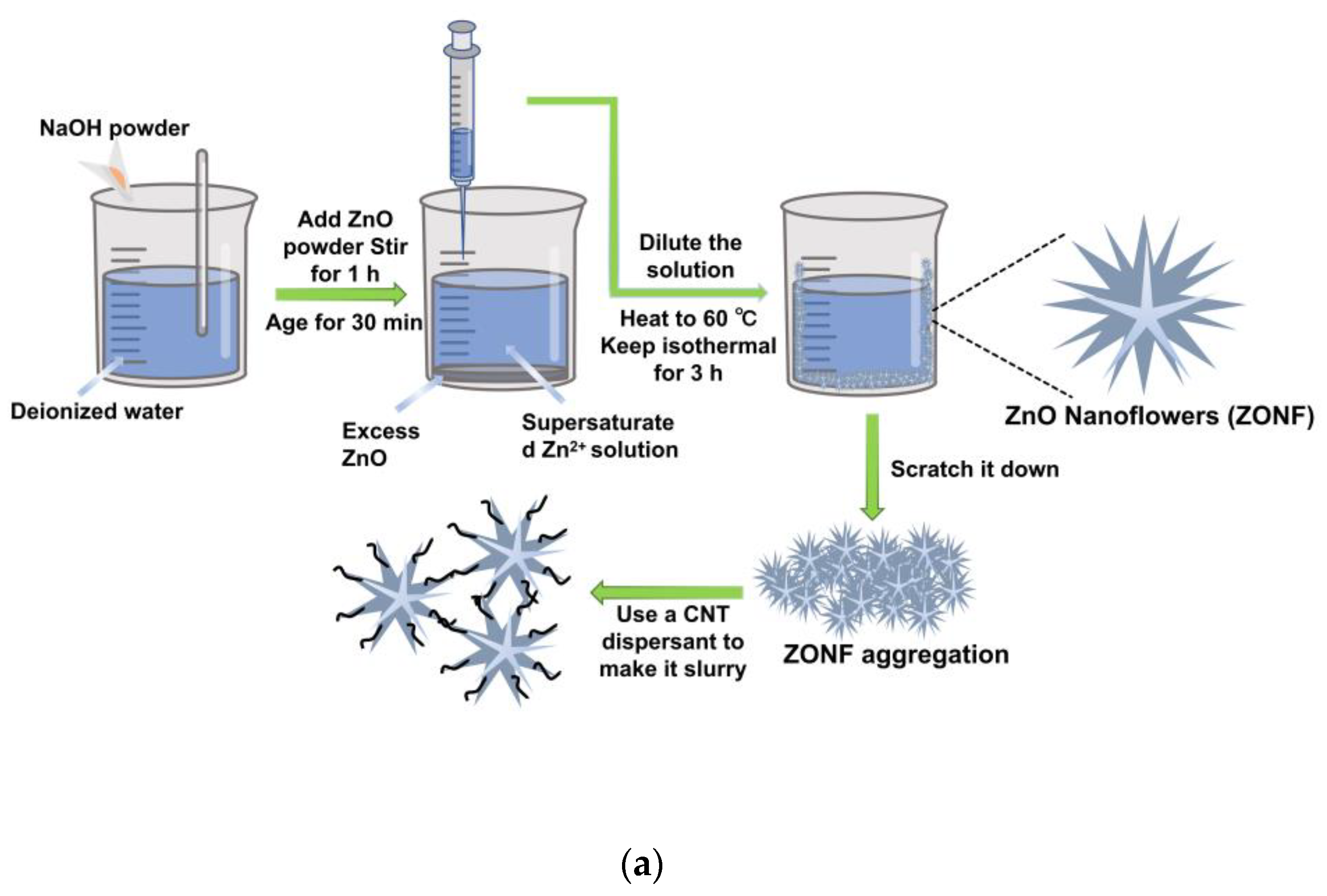

The morphology of the synthesized ZONFs was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in

Figure 2(a), the SEM image reveals a uniform distribution of hierarchical ZnO nanoflowers. It is observed that the nanoflowers possess ample space between them, which serves two important functions: firstly, it can accommodate potential expansion of ZnO during the charging-discharging process, and secondly, it provides multiple pathways for the diffusion of Li ions. At higher magnifications (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)), it can be observed that each hierarchical flower structure is composed of numerous nano-spines, significantly increasing the contact area with the electrolyte and facilitating the formation of a stable solid SEI layer. The diameter distribution of the ZnO nanoflowers was analyzed and plotted as shown in

Figure 2(d), indicating that the majority of the nanoflowers exhibit diameters in the range of 3-6 µm.

The elemental mapping analysis of the ZONFs was conducted using Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS), and the results are presented in Figures 2(e)-2(g). As anticipated, the distribution of the Zn and O elements on the surface of the nanoflowers is found to be uniform, confirming the expected composition of ZnO. Additionally, a carbon signal is observed in the EDS maps, which originates from the conductive carbon resin used for sample fixation on the platform.

Figure 2(h) displays a representative EDS spectrum of the ZONFs, revealing prominent peaks corresponding to Zn and O elements. The absence of any other significant peaks in the spectrum further supports the conclusion that the final product obtained is pure ZnO.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) was employed to gain insights into the detailed structure of the synthesized ZnO nanoflowers.

Figure 2(i) presents the overall structure of a representative flower, with a diameter of approximately 3 µm. The hierarchical architecture exhibits numerous spines protruding from a central core. At higher magnification, two individual spines are clearly visible in

Figure 2(j). The formation of these spines can be attributed to the influence of surface energy during the synthesis process of ZONFs. To further elucidate the crystal structure, High-Resolution TEM (HRTEM) imaging and corresponding Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) patterns of the ZONFs are displayed in

Figure 2(k) and 2(l), respectively. The lattice spacings observed in the HRTEM image, namely 0.26 nm and 0.25 nm corresponding to the (002) and (101) planes of ZnO wurtzite structure, respectively, indicate a polycrystalline nature of the as-prepared ZONFs, which is further confirmed by

Figure 2(l). The presence of isotropic polycrystals is advantageous in terms of improved resilience during the charging-discharging process, as compared to single crystals [

11]. Moreover, the flower-like morphology, in contrast to other nanostructures such as nanorods or nanosheets, offers a significantly larger contact area with the electrolyte, thereby facilitating the formation of a stable SEI and enhancing the reaction kinetics, ultimately reducing the polarization effect.

The electrochemical performance of the ZONF-CNT anode for LIBs was evaluated carefully with half-cells assembled with Li metal as counter anodes. From the previous report [

19], the Li

+ insertion and extraction in the anode can be generally demonstrated by the following equations:

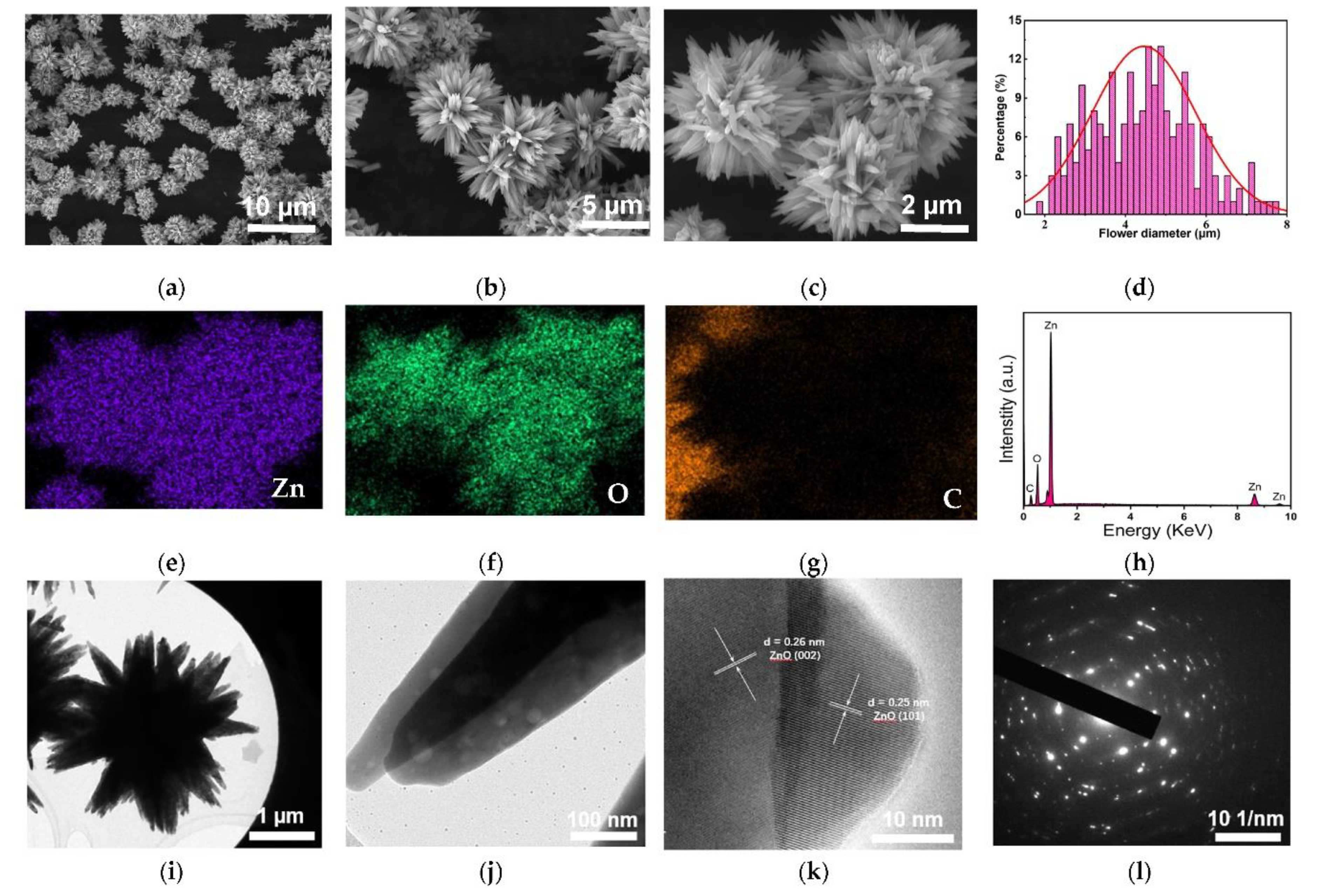

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) measurements were conducted on the ZONF-CNT anode in the voltage range of 0.05-2.5 V (vs. Li

+/Li) at a scan rate of 0.2 mV s

-1. The CV profiles depicted in

Figure 3(a) represent the electrochemical reactions during the charging and discharging processes in the cell. During the first cathodic scan of the ZONF-CNT, a distinct peak was observed at approximately 0.24 V, which subsequently shifted to a potential of 0.62 V in the subsequent cycles. This phenomenon primarily arises from the reduction of Zn

2+ to Zn, the formation of LiZn, and the generation of a Solid Electrolyte Interface (SEI) layer, which may contribute to a partial loss in irreversible capacity

20. During the anodic scanning process, five characteristic peaks at 0.36, 0.54, 0.70, 1.67, and 2.58 V were identified. The first three peaks are attributed to the multi-step de-alloying process of lithium-zinc alloys, such as LiZn, LiZn

2, Li

2Zn

3, and Li

2Zn

5, along with the decomposition of the SEI layer [

21]. The sharp anodic peak observed at 1.67 V can be attributed to the inverse conversion of Zn and Li

2O into ZnO [

22], while the 2.58 V peak is likely associated with the slight oxidation of residual dispersant, which almost disappears in the subsequent cycles. In the subsequent scans, the CV curves exhibit a high degree of overlap, indicating the excellent reversibility of the ZONF-CNT anode.

The discharge/charge profiles of the ZONF-CNT anode and the conventional ZnO anode were evaluated in the potential range of 0.05-2.5 V (vs. Li/Li

+) at a current density of 0.5C. Figures 3(b) and 3(c) illustrate the charge-discharge behaviors of the ZONF-CNT and conventional ZnO anodes during the initial three full cycles. In

Figure 3(b), the ZONF-CNT anode exhibits a discharge capacity of 2314.2 mAh g

-1 during the first cycle, with a corresponding coulombic efficiency (CE) of 56.7%. It should be noted that the initial discharge capacity is significantly higher than the initial charge capacity due to an unidentified activation process [

23]. In the 2nd and 3rd cycles, the CE improves to 80.5% and 82.5%, respectively, indicating a reduced formation of the SEI film and LiZn alloy in subsequent electrochemical processes, thus demonstrating enhanced cyclic stability. Despite the considerable capacity loss observed in the first two cycles, the ZONF-CNT anode still maintains a substantial specific capacity of 1249.8 mAh g

-1 in the 3rd cycle, surpassing the theoretical capacity (372 mAh g

-1) of commercial graphite anodes. For comparison, the discharge/charge profiles of the conventional ZnO anode in the potential window of 0.05-2.5 V (vs. Li/Li

+) were also investigated, as presented in

Figure 3(c). The conventional ZnO anode exhibits a relatively lower discharge capacity of 1066.3 mAh g

-1 in the 3rd cycle, although it demonstrates good CE in the initial three cycles.

The cycling performance of the ZONF-CNT anode and the conventional ZnO anode was assessed, as presented in

Figure 3(e), in a potential range of 0.05 to 2.5 V at a current density of 0.5C. In the first cycle, the conventional ZnO anode exhibits a discharge capacity of 2079.9 mAh g

-1, whereas the ZONF-CNT anode demonstrates a significantly higher discharge capacity of 2314.2 mAh g

-1. These relatively high capacities in the first cycle can be attributed to the formation of Li-zinc alloy and subsequent conversion of ZnO to Zn [

24]. Both the conventional ZnO and ZONF-CNT anodes exhibit notable reversible capacities at a high current density during the initial cycles. Moreover, the ZONF-CNT anode exhibits nearly twice the capacity of the conventional ZnO anode after 20 cycles. The superior rate and capacity performance of the ZONF-CNT anode can be attributed to the formation of a stable conductive network between the ZnO nanoflowers and the CNT, which effectively prevents the aggregation of active materials. Consequently, the discharge capacity of the ZONF-CNT anode stabilizes after 15 cycles, while the performance of the conventional ZnO anode continues to deteriorate until the 30th cycle. Significantly, the stable ZONF-CNT anode can be cycled for up to 50 cycles, maintaining a capacity of approximately 580.5 mAh g

-1, which greatly exceeds the theoretical capacity of graphite.

To gain deeper insights into the mechanism of the ZONF-CNT and conventional ZnO anodes, potentiostatic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis was conducted.

Figure 3(d) presents the Nyquist curves of the ZONF-CNT and conventional ZnO anodes after 15 cycles, covering a frequency range of 100 kHz to 10 MHz with an amplitude of 5 mV. As depicted in

Figure 3(e), the diameter of the depressed semicircles in the high-frequency region corresponds to the charge transfer resistance, denoted as R

ct [

25]. Notably, the R

ct value of the ZONF-CNT anode is significantly lower than that of the conventional ZnO anode. This can be attributed to the conductive nature of the CNTs enveloping each ZnO nanoflower, which provides multiple electron pathways for the charging and discharging processes. Furthermore, the EIS curve of the conventional ZnO anode exhibits a minor semicircle between the high and low-frequency regions, indicating the presence of an interface layer resistance that influences the rate performance. Consequently, owing to the hierarchical nano-flower structure and the incorporation of CNTs, the ZONF-CNT anode exhibits considerably lower resistance compared to the conventional ZnO anode. This hierarchical structure and CNT combination facilitate multi-pathways for Li-ion transport and electron conduction, respectively [

26].

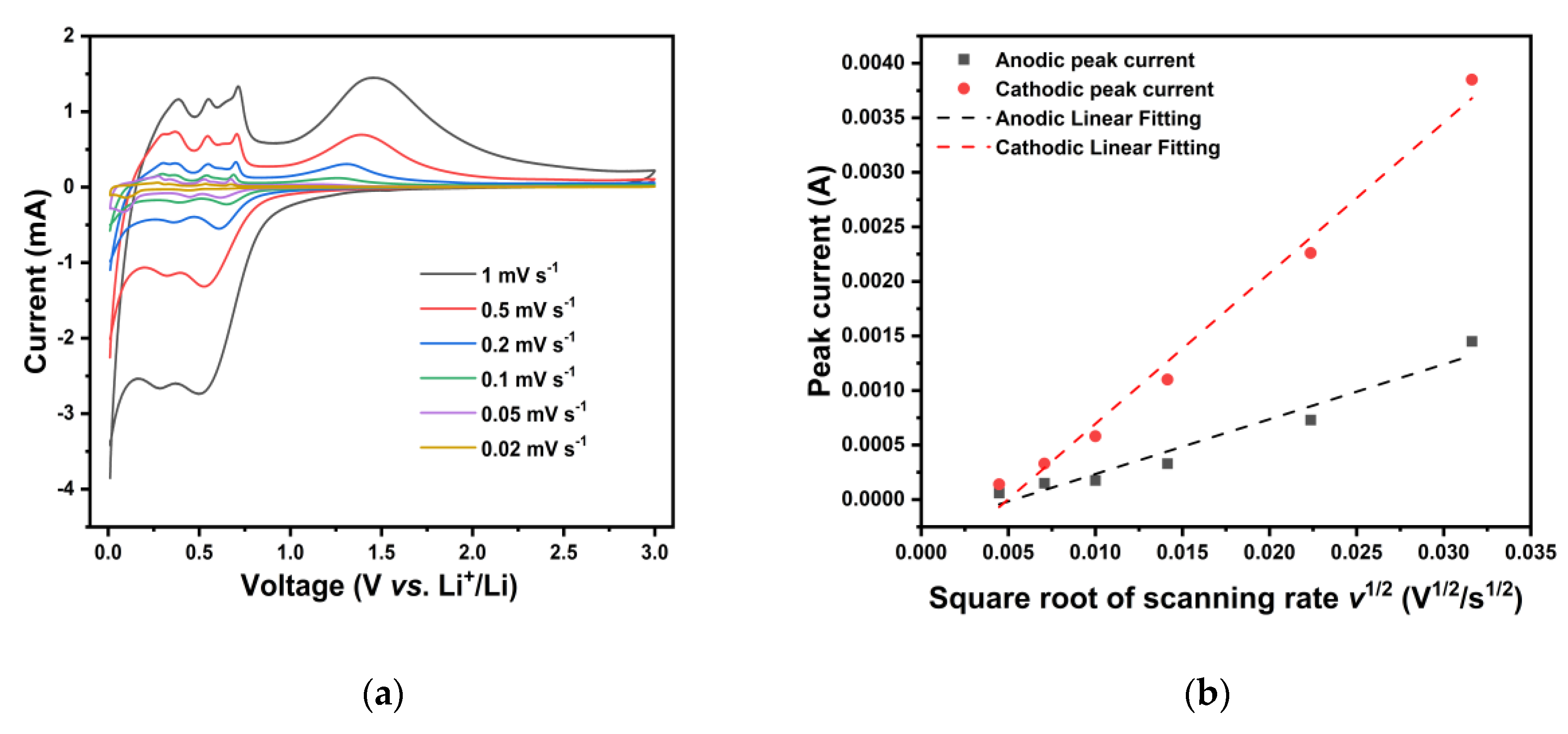

In general, four approaches are applied to figure out the Li

+ diffusion coefficient, including EIS, CV, potentiostatic intermittent titration technique (PITT) and Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT). Because of its accuracy, herein the CV method was adapted and the results at different scanning rates are presented in

Figure 4(a). The equation to calculate the Li

+ diffusion coefficient is shown below [

16]:

where I

p denotes the peak current (in Ampere), n is the charge-transfer number, A represents the surface area (in cm

2) of the anode, D

Li is the chemical diffusion coefficient for Li

+, F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, ΔC

o factor shows the bulk concentration of Li-ion in the anode (

i.e., 0.168 mol/cm

3), and v denotes the scanning rate of CV. At room temperature, Eq. (3) can be simplified as follows:

Based on Eq. (4), the relationship between the peak current and the square root of the scanning rate can be figured out and is shown in

Figure 4(b), where the slope of the linear fitting can be used to calculate D

Li directly. The Li

+ diffusion coefficient D

Li is calculated to be in the range of 3.227 ⨯ 10

-13 to 2.432 ⨯ 10

-12 cm

2 s

-1, which is even higher than that of other excellent ZnO-based anodes like hybrid ZnO/Si/porous-carbon anode [

27]. The faster Li

+ diffusion is ascribed to the hierarchical and porous structure of as-prepared nanoflowers and the synergistic function of CNTs which can not only form an electron conductive network around active materials but also prevent them from aggregating and pulverizing. As a result, both low electron charge-transfer resistance R

ct and high Li

+ diffusion coefficient D

Li have been realized, suggesting that the ZONF-CNT composite owns a superior advantage in charge transfer.