3.1. Structure Characterization and Adsorption Properties of ZIF-L

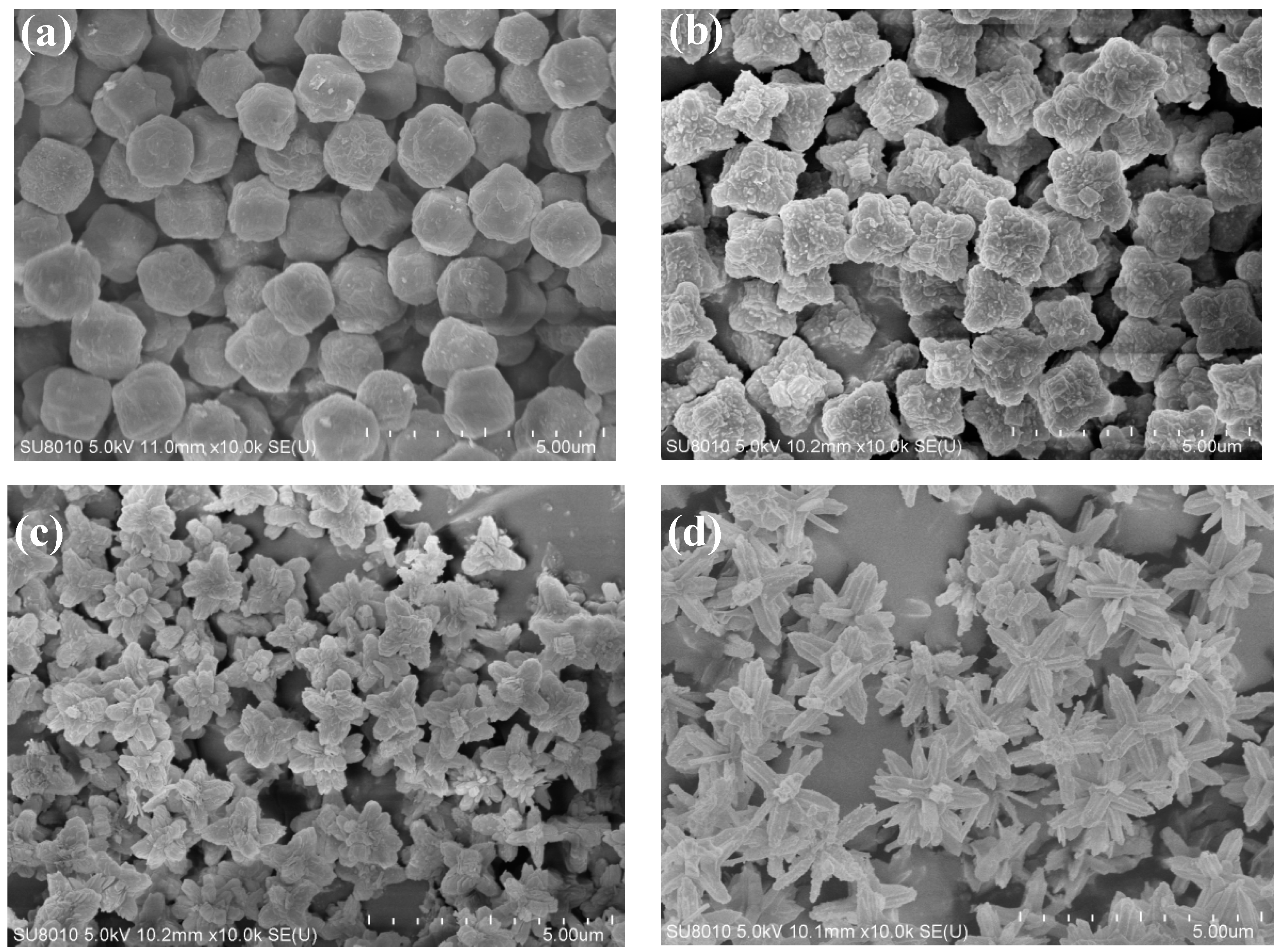

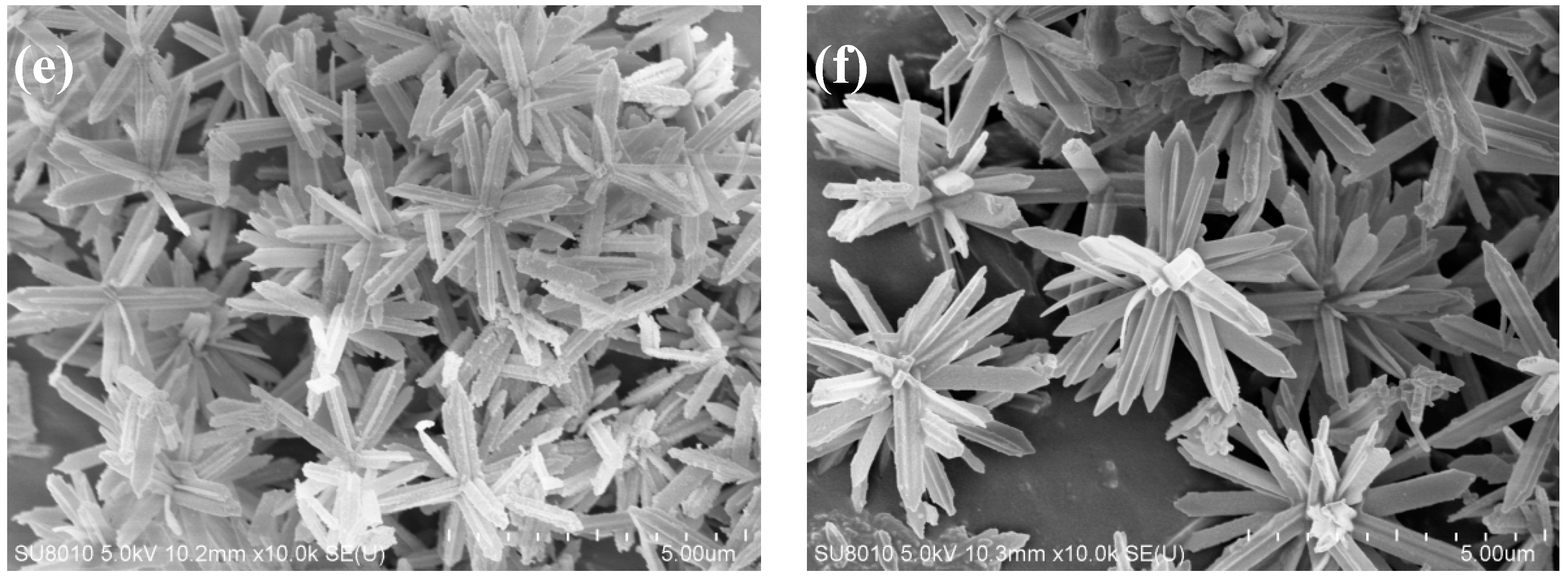

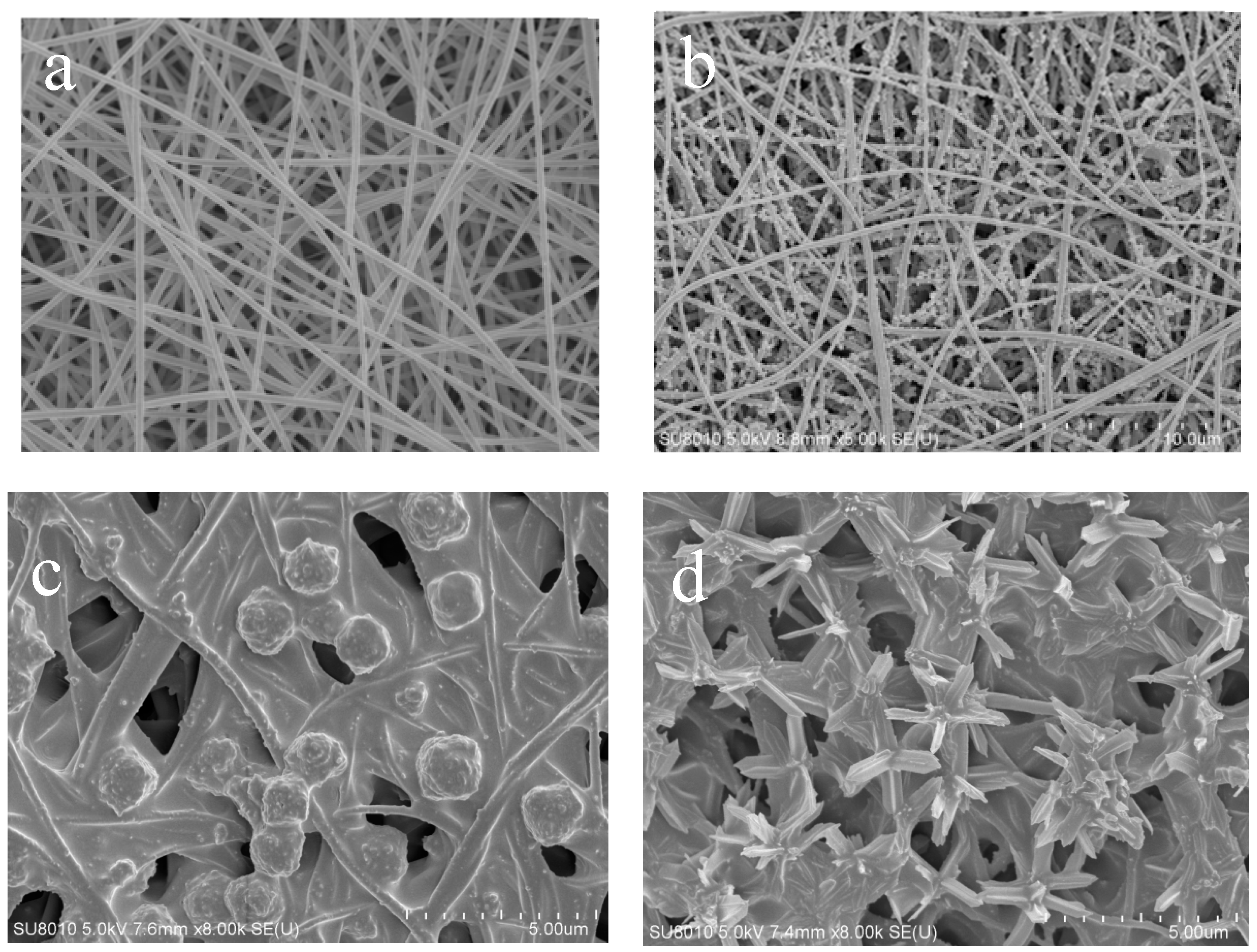

Figure 3 shows the SEM images of the ZIF-L series crystals. As shown in

Figure 3, with more addition of H

2O

2, the ZIF-L gradually grows into a flower-shaped structure with elongated branches, and such branches on the crystal surface increase in number and become longer and thinner. The observation is consistent with the description in the published literature [

6].

The formation mechanism of flower-shaped ZIF-L structures can be understood as a two-step crystal growth process. Zn2+ first binds with 2-methyl imidazole to form the ZIF-L core, and then H2O2 adsorbed onto the crystal core causes lattice accumulation layer by layer through hydrogen bonding, enabling the lateral and epitaxial growth of the crystal core. With the increase of H2O2 concentration, the number of H2O2 molecules adsorbed onto the core surface increases, and the growth site also increases. Due to steric hindrance, the core surface tends to epitaxial growth, resulting in an increased number of elongated branches on the crystal surface.

For ZIF-L-5, in the SEM image, some broken branches were found, possibly due to the branches of ZIF-L-5 are too slender and unstable during ultrasound process. However, no broken branches were observed in the morphology analysis of ZIF-L-3 and 4; this indicates that ZIF-L-3 and 4 in ZIF-L structures are more stable.

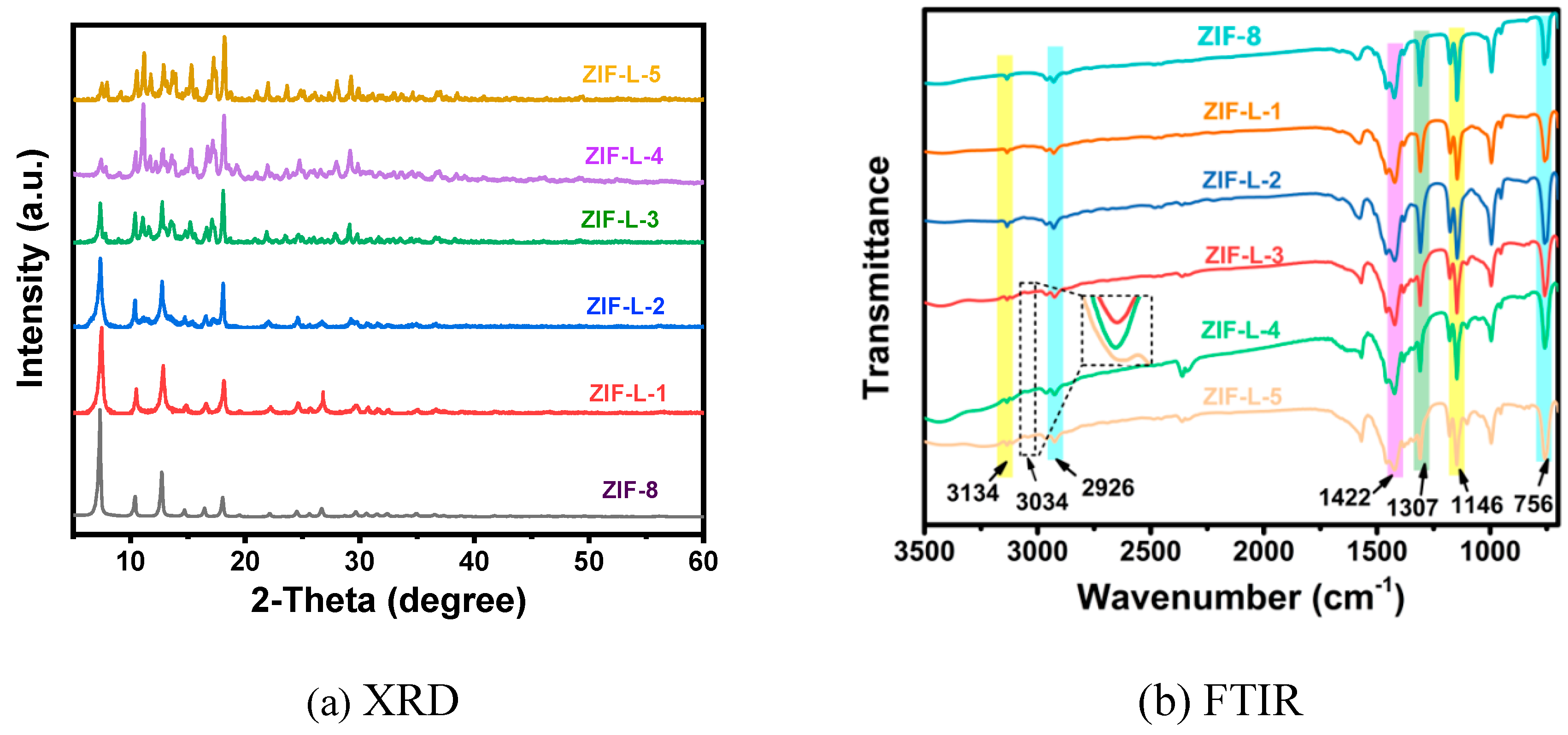

In

Figure 4a, ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-1, at 011,002,022,013 and 222, demonstrated the successful synthesis of ZIF-8 and ZIF-L[

7]. It is also noticed that ZIF-L-1 lacks the characteristic peak of ZIF-L, while ZIF-L-3, 4, and 5 are consistent with the characteristic peak of ZIF-L. This might be due to incomplete crystallization with 1ml H

2O

2, not forming ZIF-L characteristic peak. Adding more H

2O

2, the crystal structure gradually changes to ZIF-L [

8], and the ZIF-L-3, 4, and 5 crystals have changed into a stable ZIF-L structure. This demonstrates that the H

2O

2 addition to the ZIF-8 reaction system can transform the ZIF-8 crystal into ZIF-L.

In the FTIR spectrum of

Figure 4b, all ZIL-L samples display significant peaks at 756 cm

-1, 1146 cm

-1, 1307 cm

-1, 1422 cm

-1, 2920 cm

-1, 3134 cm

-1, and 3034 cm

-1. The peak at 756 cm

-1 is assigned to out-of-plane bending; peaks at 1146 and 1307 cm

-1 correspond to in-plane bending; peaks at 1422 and 2920 cm

-1 correspond to the expansion vibration of the C-H and C= N bonds on the imidazole ring; and peaks at 3134 cm

-1 correspond to the expansion vibration of the methyl group [

9]. Note that a new peak appeared in the last three samples, located at 3034 cm-1, caused by the N-H bond, which was generated as a result of the crystal transition to ZIF-L. Free 2-methylimidazole is dispersed in the middle layer of the ZIF-L phase, so there are many free 2-methylimidazole (a non-crystalline molecule at the amino-binding site) [

10].

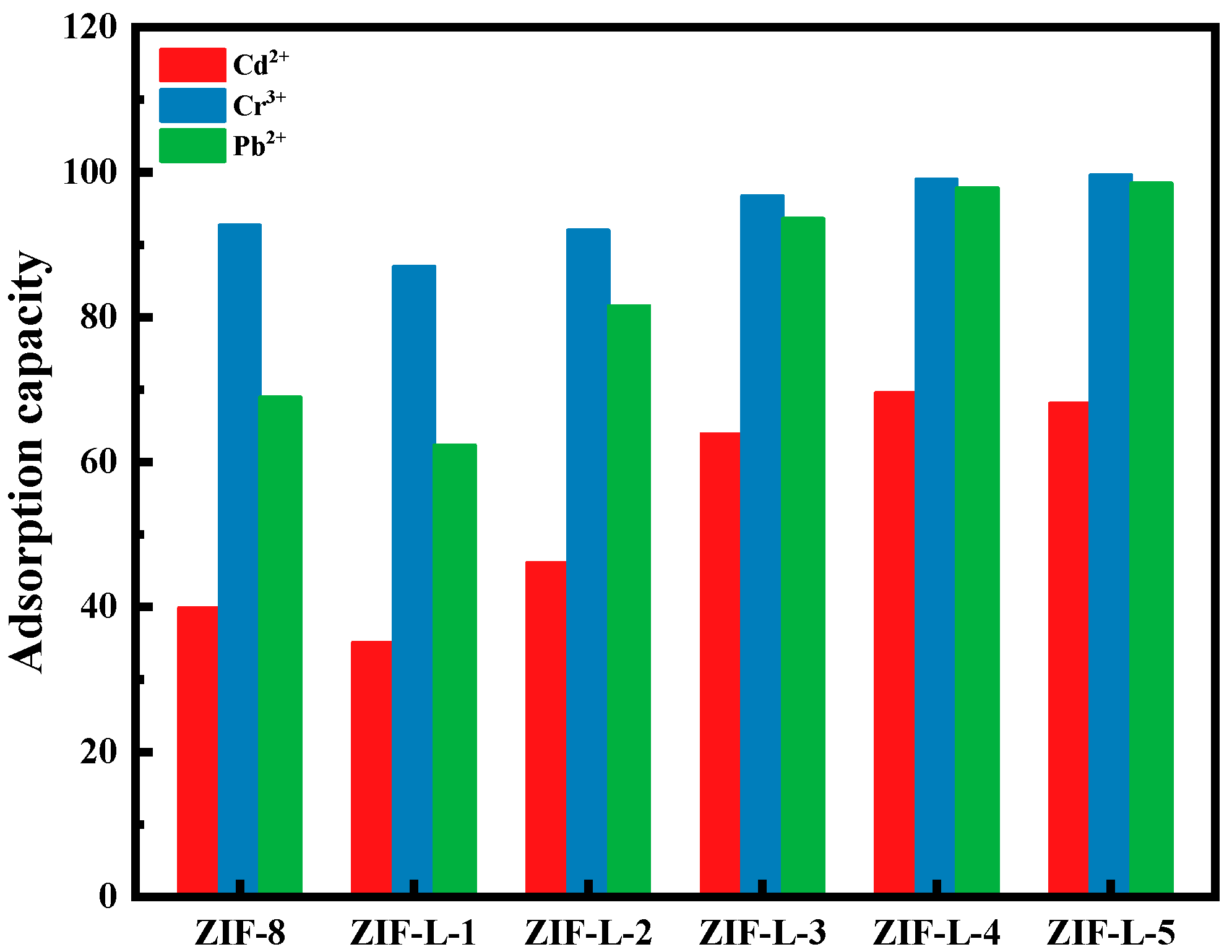

The adsorption properties of six MOF materials (i.e., ZIF-8, ZIF-L-1, ZIF-L-2, ZIF-L-3, ZIF-L-4 and ZIF-L-5) on heavy metal solutions (including 10 ppm each of Cd

2+, Cr

3+ and Pb

2+) are shown in

Figure 5.

It can be seen from

Figure 5, the six MOF materials have excellent adsorption capacity for Cd

2+, Cr

3+ and Pb

2+. The adsorption abilities are mainly attributed to the ion exchange between ZIF-L and metal cations (cation heavy metals can replace Zn

2+ site) and coordination (between cations and functional groups-NH-and-OH). In addition, electrostatic attraction also plays a synergistic role in the adsorption process [

11].

The principle of adsorption selectivity of ZIF-L series materials to three heavy metals is similar, in an order of Cr

3+> Pb

2+> Cd

2+. This is because the high ions are more likely to be adsorbed; for example, Cr

3+ is preferentially adsorbed. ZIF-8 has significantly higher selectivity for Cr

3+. For Cd

2+ and Pb

2+, with the same valences, the adsorbent usually preferentially adsorbs divalent cations with lower hydration energy; this is because the metal ions must leave most of the hydration water before entering the smaller channel of the adsorbent, and the lower hydration energy is more likely to escape [

12]. It was reported that Pb

2+ hydration energy is 1425 kJ/mol and Cd

2+ hydration energy is 1755 kJ/mol. Obviously, Pb

2+ has less hydration energy and is easier to enter the micropores of the adsorbent. The heavy metal ions separated from most of the hydration water are more conducive to interact with the adsorbent functional groups. Therefore, Pb

2+ prefers Cd

2+ to be adsorbed [

13,

14,

15]. This is also consistent with the experimental results of the present study.

The adsorption rates of ZIF-L-1 to ZIF-L-4 in mixed heavy metal solution are gradually increased with higher H2O2 addition. Branches from ZIF-L-1 to ZIF-L-4 structures increase in numbers and with elongated lengths, resulting in larger total surface areas in contact with heavy metal ions, thus high mass transfer efficiency. The adsorption capacities of ZIF-L-4 and ZIF-L-5 are barely the same. However, in the SEM images of ZIF-L-5, fragments and broken branches were found, and the branches were too slender and unstable; therefore, ZIF-L-4 was selected as the adsorbent for subsequent studies.

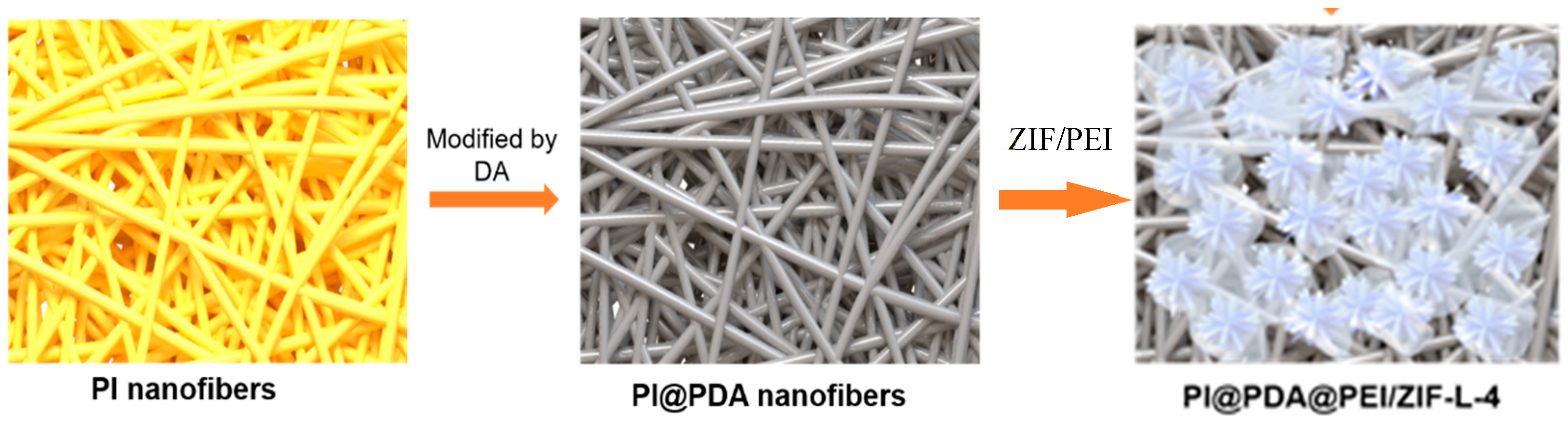

3.2. Characterization of PI@PDA@PEI/ZIF-L-4 Composite Membranes

Electrospinning nanofibers loaded MOFs is a method to produce MOFs into membranes, in which less separation pressure and lower energy consumption are needed compared to the conventional mixed matrix membrane. The commonly used methods to load MOFs on electrospinning nanofibers mainly include co-electrospinning and in situ growth; there are still certain problems such as that active sites of MOFs are buried or easy to fall off from the fiber surface.

Polyethylenimine (PEI) has many forms of amino groups, including primary, secondary, and tertiary functional amine sites. Studies have shown that PEI with coordination and hydrophilicity has excellent adsorption and chelation capacity to heavy metal ions. The present study used PEI as an adhesive to anchor MOFs to the fibers, and improved the binding force of PEI to PI by grafting polydopamine on PI nanofibers.

To obtain the PI @ PDA @ PEI / ZIF-8 and PI @ PDA @ PEI / ZIF-L nanofiber composite membranes, ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-4 were incorporated into the PEI system and coated onto PDA-modified PI fibers. In which, nanofibers mainly provide support and promote penetration, PEI provides the bonding effect of ZIF onto fibers, and ZIF-L is for the adsorption of heavy metal ions. To explore the effect of ZIF-L morphology on the membrane separation performance, the mechanism of membrane separation was speculated by XPS and EDS.

As shown in

Figure 6a,b, the PI nanofibers have a smooth surface and a three-dimensional mesh nanostructure, and the diameter of the filament ranges from 100 to 200 nm. A handful of PDA particles were adhered to the surface of the PI fibers, resulting in increase of the PI fiber diameters to 150~280 nm, along with a corresponding increase in the roughness of the nanofibers.

From

Figure 6c,d, it can be seen that spherical particles of about 2 μm in diameter can be observed on the surface of the composite membrane mixed with ZIF-8, consistent with the morphology of ZIF-8 crystals. The composite membrane incorporated with ZIF-L-4 (PI@PDA@PEI/ZIF-L-4 membrane) was bonded to a large number of flower-shaped ZIF-L-4 crystals with a diameter of approximately 4 μm. The incorporation of PEI binds ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-4 to the fiber through the cross-linking network, binding ZIF-L-4 tightly to the fiber matrix and not easy to fall off.

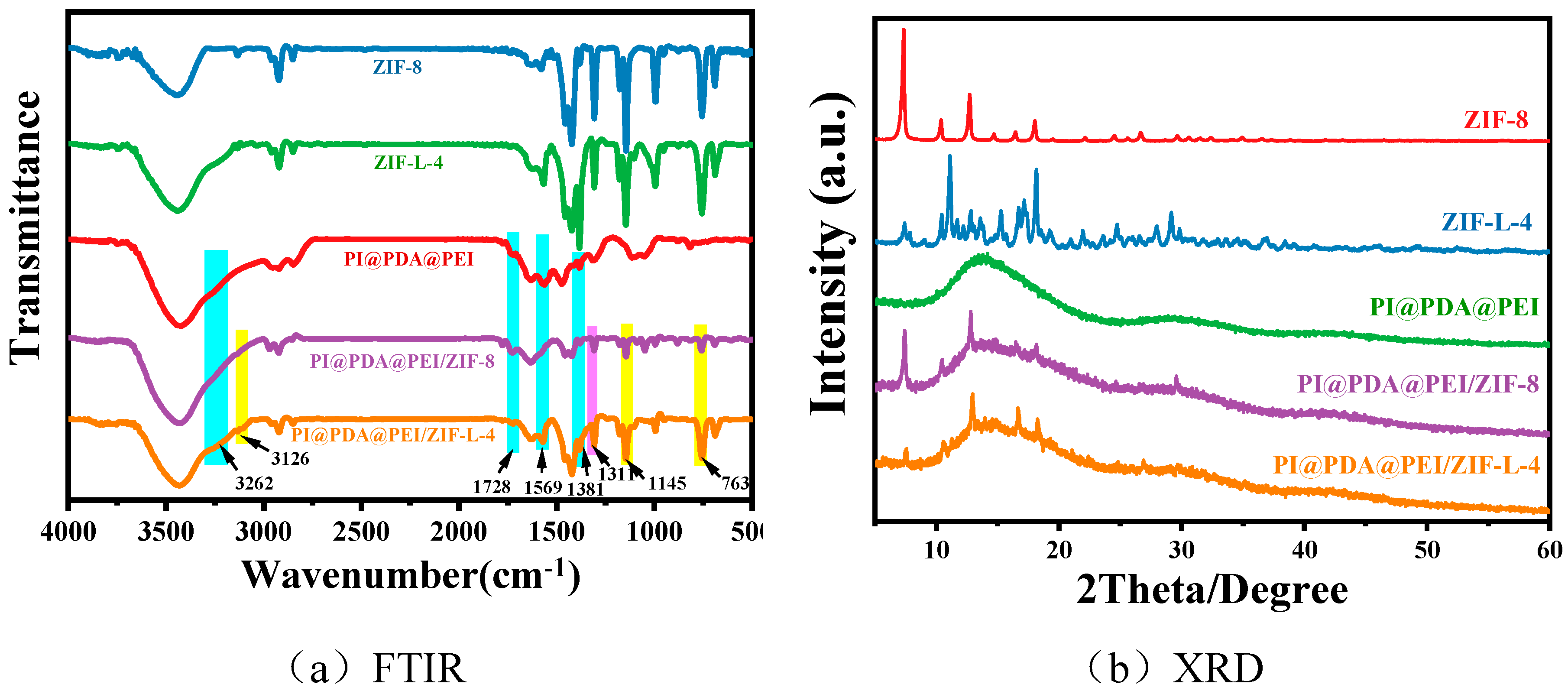

The composition and structure of the different materials were verified by FTIR and XRD, as shown in

Figure 7.

As shown from

Figure 7a, in the PI@PDA@PEI membrane, distinct characteristic peaks can be observed at 3262 cm

-1,1569 cm

-1,1483cm

-1 and 1580 cm

-1. The peaks at 3262 cm

-1 and 1569 cm

-1 belong to the bending vibrations of the-NH

2 and-NH in the PEI chain, respectively. The more intense peaks at 1483 cm

-1 and 1580 cm

-1 peaks represent the characteristic absorption peaks of the secondary amine and primary amine groups [

16,

17].

For ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-4, the peak at 756cm

-1 is assigned to out-of-plane bending; peaks at 1146 and 1307cm

-1 correspond to in-plane bending; peaks at 1422 and 2926cm

-1 correspond to the expansion vibration of the C-H and C= N bonds on the imidazole ring; and the peak at 3134 cm

-1 corresponds to the expansion vibration of the methyl group. Note that a new peak appeared in the last three samples, located at 3034 cm

-1, which is caused by the N-H bond. The formation of this bond is the result of the crystal transition to ZIF-L, where the free 2-methimidazole is dispersed in the middle layer of the ZIF-L phase, so there are many free 2-methimidazole (a non-crystalline molecule in the amino binding site) [

6].

Compared with PI@PDA@PEI, some new peaks appeared in the PI@PDA@PEI/ZIF-8 and PI@PDA@PEI/ZIF-L-4 composite membranes. The new peak at 3136 cm-1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the methyl group in ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-4, the new peak at 759cm-1 corresponds to out-of-plane bending of ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-4, and the new peaks at 1147 and 1308cm-1 correspond to in-plane bending of ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-4, demonstrating the successful loading of ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-4.

From the XRD profile of

Figure 7b, the diffraction peak of ZIF-8 is consistent with those reported in previous work, where 2 θ are characteristic peaks of 7.3,10.3,12.7,12.7,14.7,16.4 and 18.0 corresponding to (011), (002), (112), (022), (013) and (222) surface [

18], demonstrating the successful preparation of ZIF-8. The diffraction peak of ZIF-L-4 agrees with that of ZIF-L as shown in the literature, indicating the successful preparation of ZIF-L-4. The peaks of both composite membranes correspond to the amorphous peaks of the polymer and the major crystallization peaks of ZIF-L. ZIF-L doping is effective, and the topology of all species is preserved after recombination.

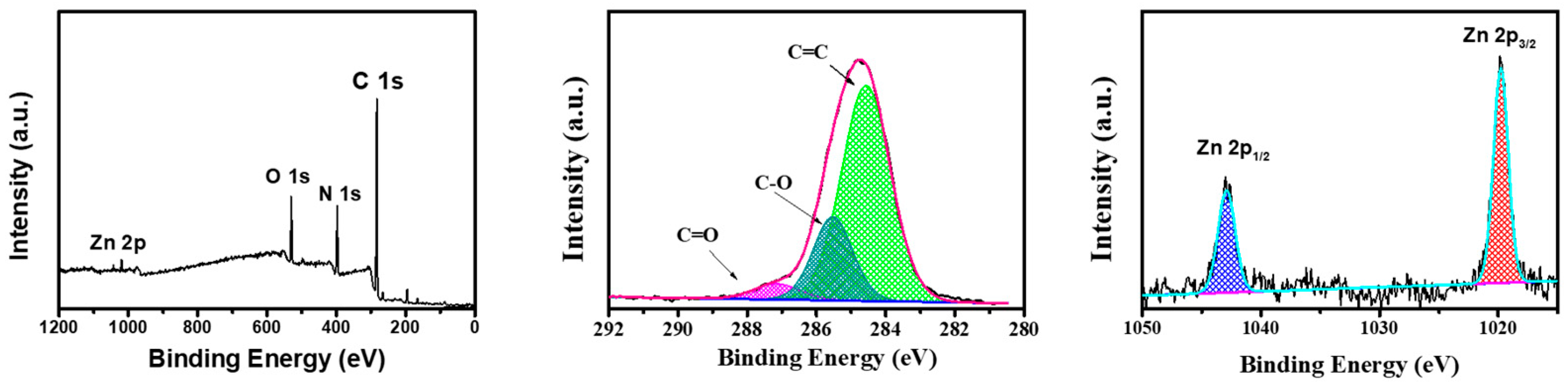

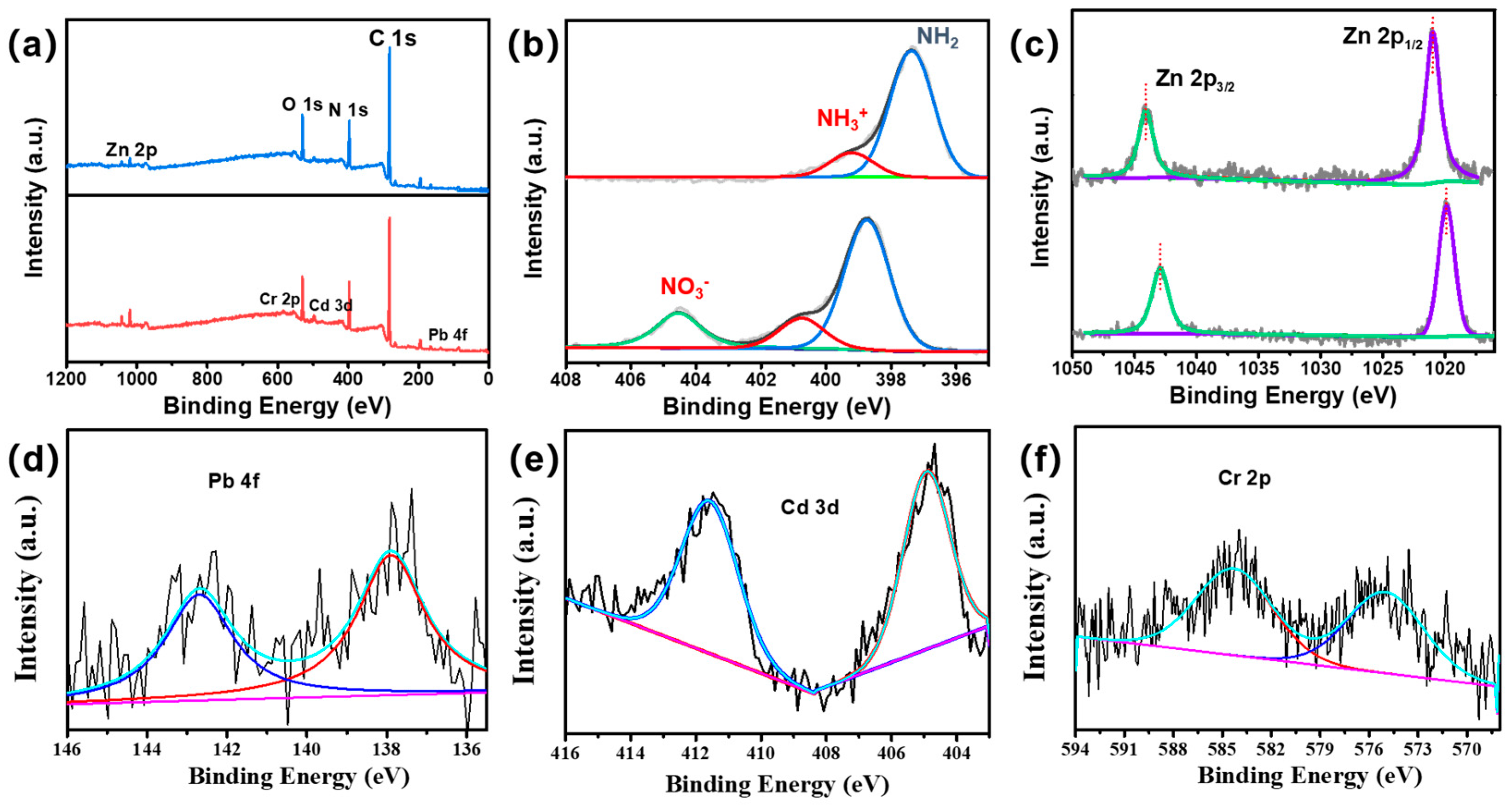

To further verify the structure of the composite membrane surface, an XPS analysis was performed on the PI @ PDA @ PEI / ZIF-L-4 composite membrane, as shown in

Figure 8. The prepared composite membrane samples showed several characteristic peaks at binding energies of approximately 285.08, 397.08 and 531.8 eV, mainly corresponding to C 1s, N 1s, O 1s and Zn 2 p. In the C1s spectrum, three main peaks can be observed at 287.7, 285.8 and 284.5 eV for C=O, C=N and C=C groups. Among them, the C=O group proves the existence of the PI fiber layer in the composite membrane, the C=N group is the crosslinking reaction between PEI and ECH, and the C=C group proves the presence of 2-methimidazole in PI and ZIF-L.

High-resolution N 1s spectra (

Figure 8) were fitted to two characteristic nitrogen species at 399.2 and 397.4 eV, corresponding to neutral amine (–NH

2/–NH) and protonated amine (–NH

3+ or -NH

2+), confirming the binding of PEI in the composite membrane. In addition, two characteristic peaks of Zn were displayed at 1020.6 eV (Zn2p3) and 1043.9 eV (Zn2p1). The above results showed that the PEI / ECH crosslinking system was successfully synthesized on the PI nanofibers and the ZIF-L-4 nanoparticles were successfully loaded on the membrane surface.

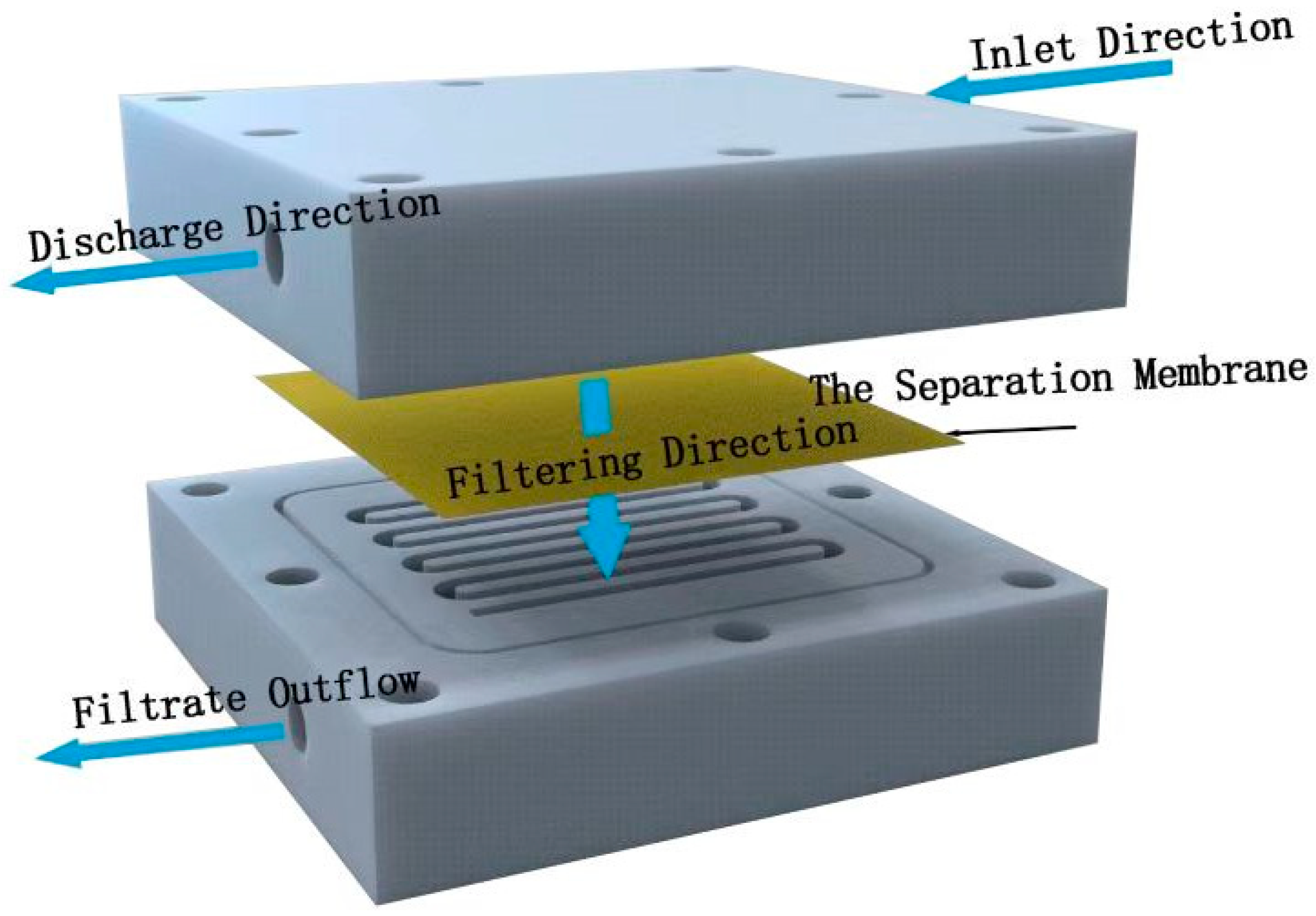

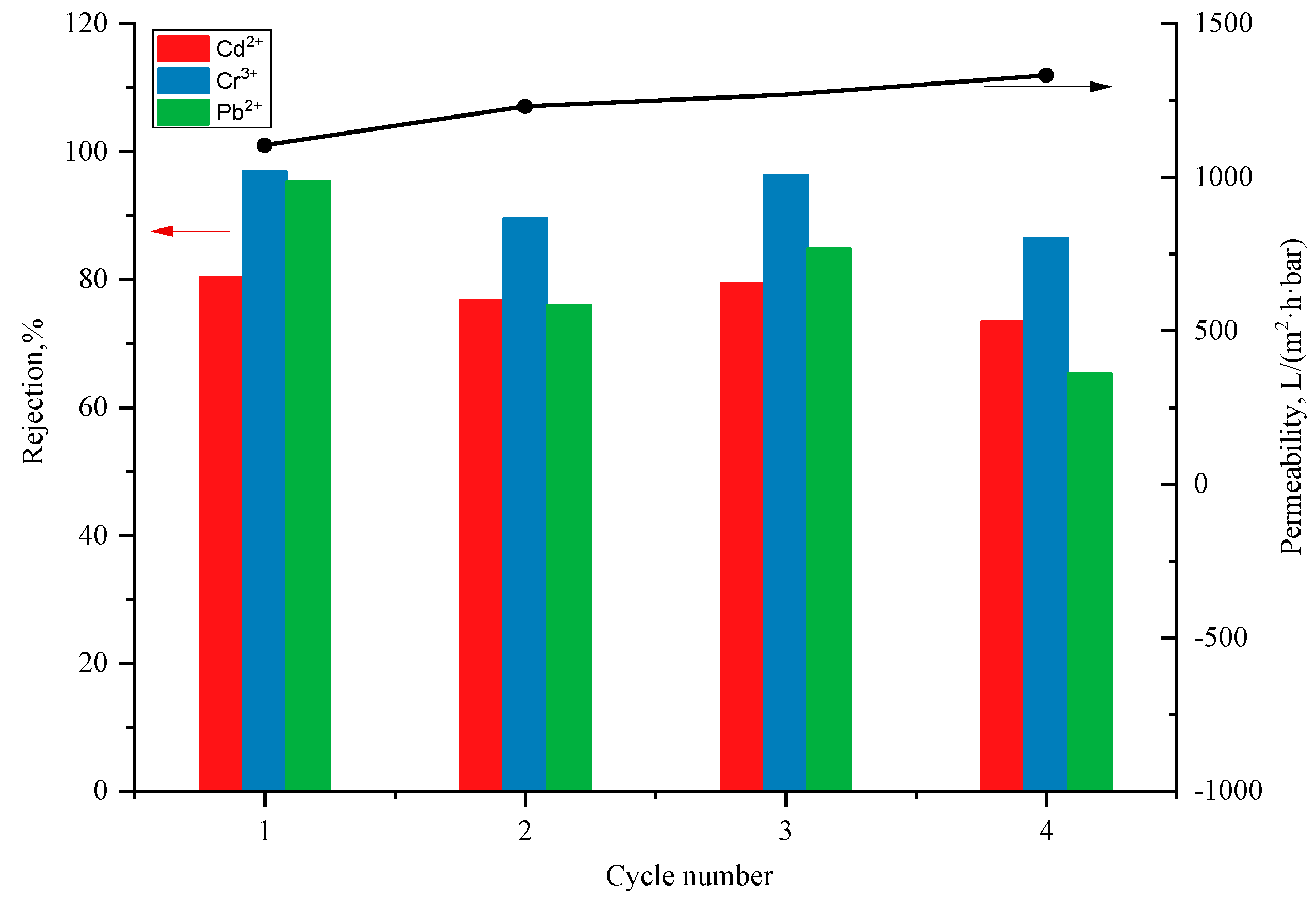

3.3. Separation Properties of the PI@PDA@PEI/ZIF-L-4 Composite Membranes

The separation properties of the membrane were determined by permeability experiments. Through the operation of the self-made cross-flow filtration device, the water flux of the membrane was calculated by formula (1), and the heavy metal barrier rate was calculated by measuring the concentration change of heavy metal ions before and after cross-flow filtration by ICP-OES. The operating pressure of the device is 1bar, the test temperature is 25℃, the three-component heavy metal solution is used as the feeding liquid (including Cd2+、Cr3+ 、Pb2+ each 1ppm), and the solution flow rate is 250 ml/min..

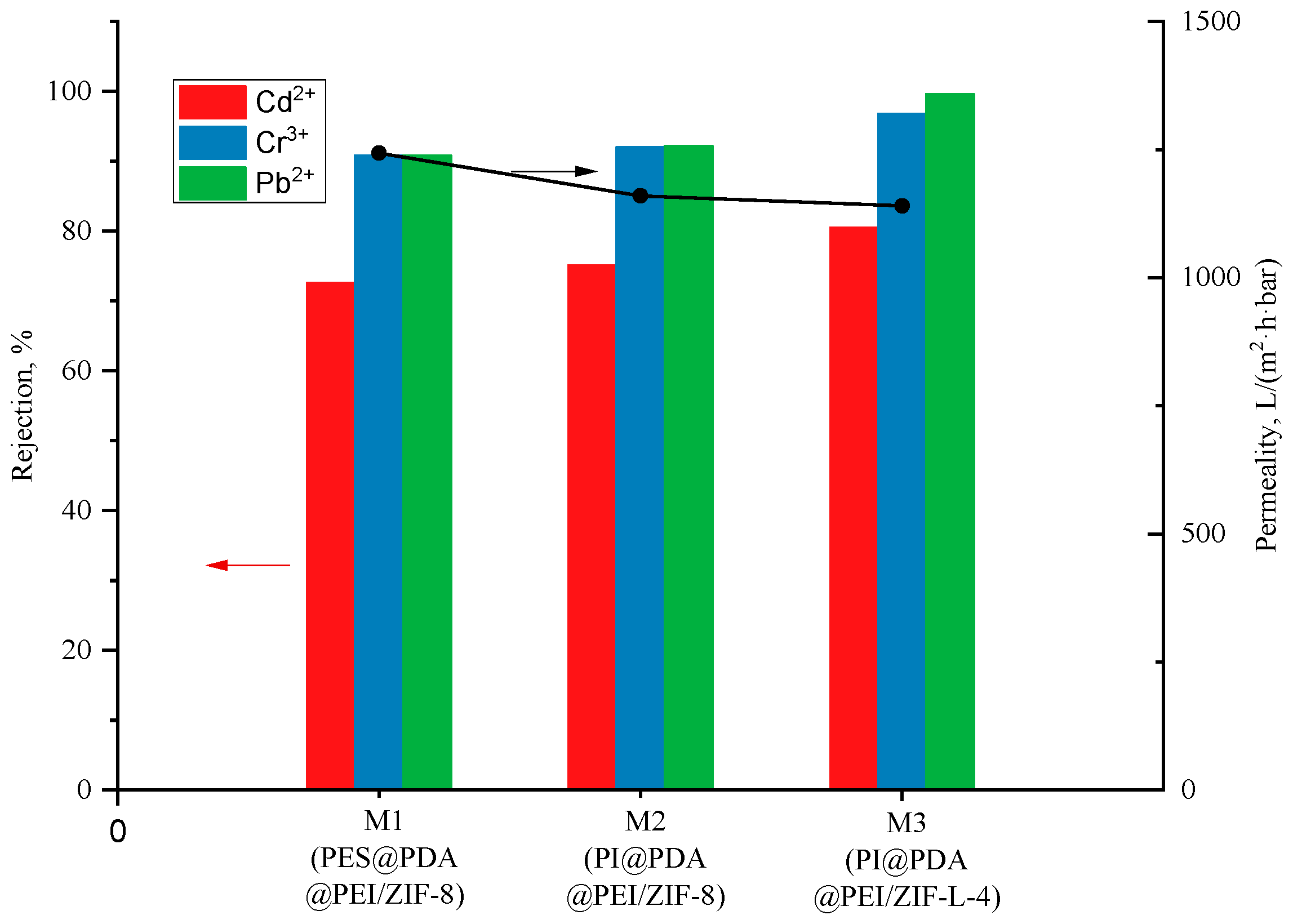

The water flux of PI @ PDA @ PEI / ZIF-8 composite membrane and PI @ PDA @ PEI / ZIF-L-4 composite membrane and the separation performance for heavy metal solutions are shown in

Figure 9.

In this experiment, effects of MOF morphology on the separation performances were investigated by doping the membrane with ZIF-8 and ZIF-L-4 in different appearances. As shown in the

Figure 9, the flower-shaped ZIF-L-4 can be more assisting to the deposition of PEI on the fiber membrane with more mosaic branching structures, and the crystal branches interlace each other, providing a long-range channel for the transport of water molecules. Therefore, the water molecules stay in the membrane for longer, and the water flux (1140 L·m

−2·h

−1·bar

−1) is lower than the water flux of the ZIF-8 composite membrane (1243.44 L·m

−2·h

−1·bar

−1).

As seen in

Figure 9, the water flux of the PI @ PDA @ PEI / ZIF-L-4 composite membrane is 1140 L·m

−2·h

−1·bar

−1, which is lower than such of the ZIF-8 composite membrane (i.e., 1243.44 L·m

−2·h

−1·bar

−1). The fact is that, comparing with ZIF-8, the flower-shaped ZIF-L-4 (containing more mosaic branching structures and with branches between crystals cross each other) provides a long-range channel for the transport of water molecules; thus, the water molecules stay in the membrane for longer.

It can also be seen in

Figure 9 that by introduction of ZIF-L-4 into the composite membrane, the removal rate of heavy metals was significantly increased. The barrier rate of Cr

3+ and Pb

2+ both exceed 90%. The removal rate of Cd

2+ increased by 7%, from 73.3% to 80.4%; the removal rate of Cr

3+ increased by 6.6%, from 90.2% to 96.8%; the removal rate of Pb

2+ increased by 9.3%, from 90.3% to 99.6%. Due to the flower-shaped branching structure of ZIF-L-4, the total surface area of contact with heavy metals is larger than that of ZIF-8. The long-range orderly channels formed by staggered branches enforce great resistance to transmission of heavy metal ions, and also greatly improves the efficiency of heavy metal ions contacting the active site on ZIF-L-4. The adsorption effect of heavy metal ions is much better improved.

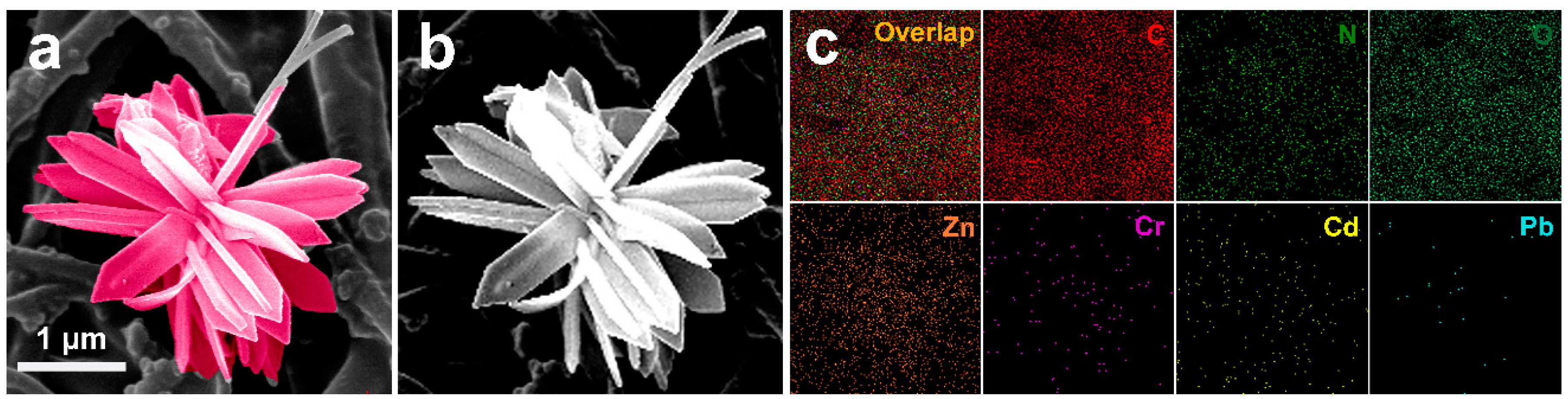

3.5. Exploration of Separation Mechanism of ZIF-L/PEI/PDA@PI Composite Membrane

The composite membranes prepared in this experiment are High Flux Separation Membranes permeating at low pressure. It is expected to adsorb heavy metal ions through the active sites in the membrane. EDX mapping was inspected on membranes as shown in

Figure 11.

As shown in

Figure 12, Cd

2+ and Cr

3+ exist on the membrane surface, but Pb

2+ was not detected. It can be confirmed that the adsorption of heavy metal ions does occur on the membrane surface. When the heavy metal ions are adsorbed on the membrane surface, the electrostatic repulsion between the incoming heavy metal ions in the solution and the adsorbed heavy metal ions will be conducive to the high exclusion of the incoming heavy metal ions. The content of lead is low, probably because Pb

2+ has a smaller hydration energy, which is easier to enter the micropores of the adsorbent and also easier to enter the channels of ZIF-L-4. ZIF-L-4 adsorbs Pb

2+ in pores through pores. Since ZIF-L-4 has a large size and many channels, the detection depth of EDX cannot reach the Pb

2+ captured in the pores. The adsorption mechanism has to be verified by XPS.

As shown in

Figure 12, peaks of Pb4f, Cd3d, and Cr2p appeared in the spectrum of XPS after adsorption, indicating that Cd

2+, Cr

3+, and Pb

2+ were successfully adsorbed on the surface of the composite membrane. Before adsorption, the N 1s spectra were deconvoluted into two peaks at binding energies of 399.2 and 397.4 eV, corresponding to the neutral amine (–NH

2/–NH) and protonated amine (–NH

3+ or -NH

2+). With the filtration contacting with heavy metal ions in the feeding solution, the N 1s spectra of the composite film at binding energies of 404.5, 400.7, and 398.73eV were deconvoluted into three peaks. First, the new peak observed at 404.6ev corresponds to the nitrate (-NO

3-). The positive binding energy of the neutral and protonated amine is attributed to the binding of nitrogen atoms to heavy metal ions. Because the N atom shares lone pair electrons in the hybrid orbit coordinated between nitrogen and heavy metal ions, coordination bonds are formed, resulting in reduced electron cloud density, thus moving the binding energy to high energy [31]. Before adsorption, Zn2p peaked at 706.5 eV and 719.9 eV, demonstrating the presence of ZIF-L-4. After heavy metal adsorption, the Zn2p binding energy decreased and moved negatively, indicating that the chemical environment of Zn also changed. This is mainly due to the adsorption of heavy metal ions around Zn, changing the distribution state of its electron cloud, and Zn is also the active site of heavy metal adsorption.