1. Introduction

The generation of wastewater from domestic, agricultural and industrial sources has a major impact on aquatic ecology, drinking water quality and public health [

1,

2]. Current wastewater treatment processes necessitate large capital investments and these systems emit substantial amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere [

3,

4,

5]. The bio-electrochemical systems are green technology to address this problem, because these devises transform organic compounds into fuels, electric energy or hydrogen [

6,

7]. The two-chamber configuration (MFC) employs a proton exchange membrane (PEM) or separator between the anode and cathode. Ion exchange membranes have positive or negative functional groups that can facilitate selective transport of opposing ions. In bioelectrochemical systems (BES), the PEM acts as a physical barrier that separates the anodic and cathodic reactions catalysed by microorganisms, while maintaining chemical gradients and reducing the distance between electrodes [

8]. An ideal separator is engineered to enhance energy production, minimize oxygen crossover to the anode, restrict the diffusion of fuel and organic matter to the cathode, create no resistance to the transport of ionic species, prevent biofouling of the the cathode, and expandthe functionality of the BES beyond poewer generation [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Nafion-117 is a membrane widely used in BES such as microbial fuel cells (MFC) and microbial electrolysis cells (MEC). Nafion-117 membranes offer excellent mechanical stability, high cationic conductivity and resistance to chemicals [

13]. However, their perfluorinated sulfonic acid groups reduce their function to alkaline environments because they can become protonated in alkaline environments, thereby diminishing their ion transport capability. In addition, Nafion-117 membranes account for 40% of the total cost of BES, and their disposal presents significant environmental concerns [

14]. Similarly, polyamide nanofiltration (NF) membranes, which have not previously been tested in microbial fuel cells (MFCs), pose similar challenges.NF membranes are able to retain small organic particles and salts, potentially reducing oxygen crossover [

15]. While they may introduce higher ion transfer resistance than the ion-selective membranes commonly used in MFCs, they may still be promising candidates for evaluation as separators in these systems due to their unique properties and potential advantages [

12].

Recent research has focused on integrating hybrid organic-inorganic membranes into a single membrane to take advantage of the complementary properties of each component. [

16]. Natural polymers such as chitosan are a sustainable and cost-effective alternative to synthetic polymers. Chitosan-based hybrid composites, nanomaterials, ion exchange membranes, and mixed matrix membranes have attracted extensive attention. [

17,

18,

19]. Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs), a subclass of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), are promising materials due to their high surface area, crystallinity, and microporous structure. In particular, ZIF-8, which has large pores (11.6 Å) that are accessible through small openings (3.4 Å), suggests potential applications in various fields [

20,

21].

This study presents a novel separator based on a chitosan biopolymer in combination with nanochannels created from ZIF-8 nanofillers. The performance of the composite membranes was evaluated in comparison with commercial membranes (Nafion-117 and NF) for use in BES. The incorporation of ZIF-8 nanofillers into the chitosan matrix effectively restructure chitosan matrix and facilitated selective ion transport through the newly formed nanochannels. This enhanced ion transport resulted in high proton conductivity of up to 0.105 S/cm at room temperature and low surface resistance. These favourable properties make the composite ZIF-8/CS membranes promising candidates for BES separator applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄, 98%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 97 %), sodium chloride (NaCl, 99.99%), anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4, ≥99.0%), hydrochloric acid fuming (HCl, 37%), potassium chloride (KCl, ≥99.5%), iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO₄.7H₂O, 99.5%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%), magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (MgSO₄.7 H₂O, 99.0%) and acetic acid (CH3COOH, 99.8%), were purchased from Merck KGaA. Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn (NO3)2⋅6H2O, 99%), 2-Methylimidazole (Hmim, 97%) and Dimethyl carbonate (DMC, 99%) were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Germany). The Bovine Serum Albumin (Lyophilized Powder BSA ~66 kDa) and Chitosan CS polymer powder (low molecular weight) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (US). Triethylamine (TEA, N(CH2CH3)3, 99.5%), ethanolamine (NH₂CH₂CH₂OH, 99.5%), absolute ethanol (C2H5OH, 99.9%), Nafion-117 and NF membrane were provided by VWR International (Belgium). PAN (PX-FSR-1) was purchased from Synder Filtration (USA). All chemicals were used as received without further purification procedure.

2.2. Synthesis of ZIF-8 Particles

ZIF-8 particles were synthesized according to the method described in [

22]. Initially, 2.00 g of Zn (NO

3)

2⋅6H

2O was dissolved in 12.1 g of deionized water. Furthermore, 3.31 g of Hmim was dissolved in 48.4 g of deionized water. Thereafter, 3.00 ml of TEA was added to the Hmim solution. Then the two solutions were mixed for 30 min. The product was then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min and washed twice with deionized water and once with absolute ethanol. Finally, the product was dried in an oven at 120 ℃ for 10h before the following use.

2.3. Membrane Preparation

The composite ZIF-8/CS membrane were synthesized according to the method described in [

22]. First, 1.00 g of CS was dissolved in 49.0 g of 2.00 %wt. acetic acid solution and stirred at room temperature for 2h. Then, the pH of the solution was adjusted to ≥ 4 using ethanolamine [

23]. The solution was stirred for 24 hours. Thereafter, 0.150 g of ZIF-8 nanoparticles, a concentration effective in previous pervaporation studies, was added to optimize porosity and ion transport in the membrane for BES. The mixture was stirred for 12 hours to ensure uniform distribution of the particles in the CS. After stirring, the membranes were prepared by solvent evaporation method. Briefly, the solution was poured onto support membranes (PAN) with a stainless-steel retaining ring and dried in a fume hood to obtain the dried membrane. After drying, composite ZIF-8/CS membrane was neutralized with NaOH aqueous solution. For the method, NaOH was dissolved in deionized water to make 2.00 %wt NaOH aqueous solution. Composite ZIF-8/CS membrane was immersed in this solution for three times (15 min each time) and then washed with absolute etanol for three times [

24]. Finally, the membranes were stored in a 0.500 g/L NaCl solution before the next use.

2.4. Membrane Characterization

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Zeiss, ULTRA with Bruker EDS chemical analyzer) was used to analyze the ZIF-8 nanofillers and show the morphology of the composite ZIF-8/CS membrane. The membranes were previously immersed in liquid nitrogen to obtain a clean cross section. Then, a thin layer of gold was deposited under vacuum with a sputter coater (BALZERS UNION FL 9460 BALZERS SCD 030) to make the samples conductive. As for the crystallinity of ZIF-8 nanofillers, pure CS and the composite ZIF-8/CS membrane, it was investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance, Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.54 Å) in the range of 6.00 to 60.0°, while the FT-IR spectra of the ZIF-8 nanofillers and composite ZIF-8/CS membranes. were obtained using a Bruker spectrometer from 400 cm

- 1 to 4000 cm

- 1 in ATR mode to investigate the chemical composition of the fabricated membrane.[

22]

2.5. Water Uptake Test

Water absorption tests on the membranes were carried out gravimetrically using an analytical balance (Denver Instrument model TP-214). Before conducting water uptake, membranes were dried into an oven at 80°C for 12 hours to remove excess humidity. Afterward, the samples were cut into 2x2 cm squares. After cutting, the dried membrane samples were immersed in deionized water for 24 hours at 37 °C. Hydrated membrane samples (W

wet) were weighed as quickly as possible. After weighing, the membrane samples were dried again at 60 °C for 24h in an oven to evaporate all of the adsorbed water. The membrane samples were reweighed (W

dry). All experiments were performed at least three times. Water absorption was calculated using the following equation [

25,

26]:

2.6. Durability Test

The durability of the membranes was evaluated by the Fenton test [

27]. First, the samples were cut into 2x2 cm squares. After cutting, the dried membrane samples were immersed into 50.0 ml Fenton solution (3.00 % wt. hydrogen peroxide solution and 20.0 ppm Fe

2+) for 150 hours at 80

◦C [

28]. Finally, the weights of dried samples before (Wa) and after (Wd) the experiment were compared. Membrane durability was calculated from the following equation [

29,

30]:

2.7. Surface Electrical Resistance

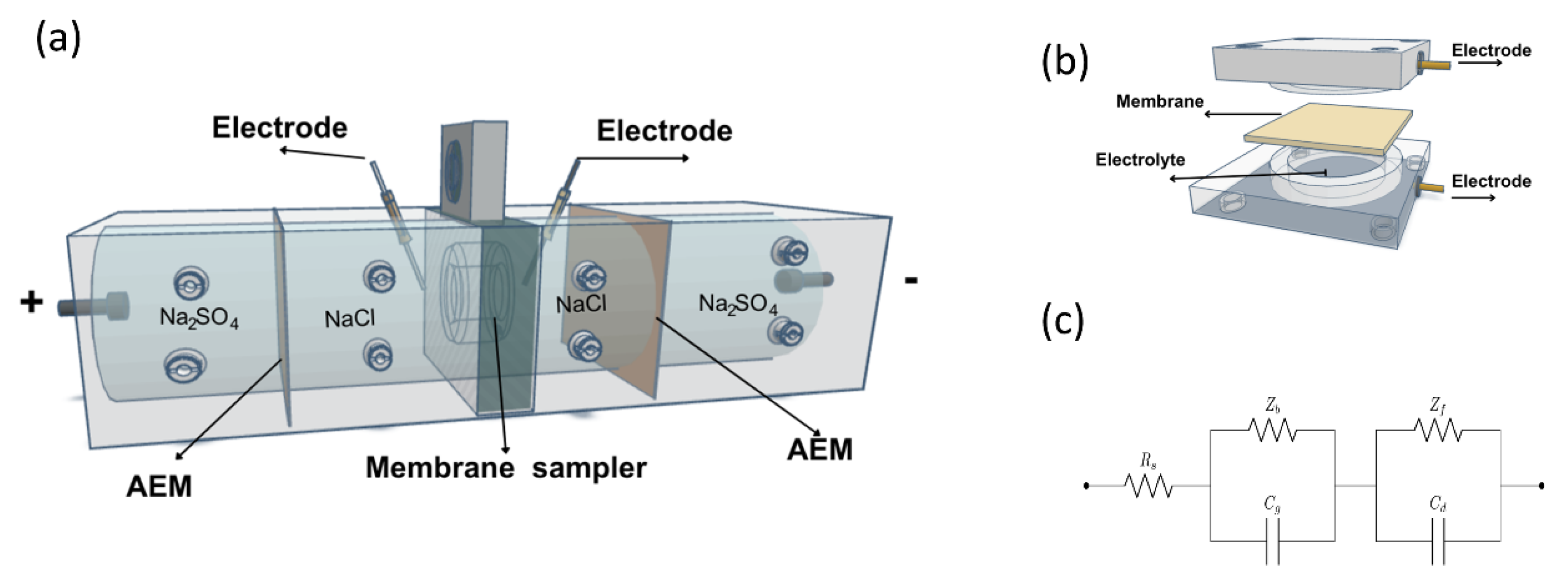

The surface electrical resistance of the membrane was measured by chronopotentiometry. The diagram of the experimental cell is shown below (

Figure 1a).

The four-chamber test cell (

Figure 1a) used had an effective membrane area (S) of 7.00 cm

2 and two Ag/AgCl reference electrodes, closed to the membrane, to measure the potential difference across the membrane. After the cell was assembled, solutions of NaCl 0.100 molL

-1, Na

2SO

4 0.200 molL

-1 and bovine serum albumin (BSA) 0.500 gL

-1 were circulated in the corresponding chambers at a specific flow rate using four pumps. Then, a direct current (I) of 11.0 mA and potential of 9.00 V was applied for 24h. At the same time, the potential difference without the membrane sample (U) and with the membrane sample (U

o) was measured using a voltage data logger (Pico Technology PicoLog 1012) [

31,

32]. Electrical resistance was calculated from the following equation.

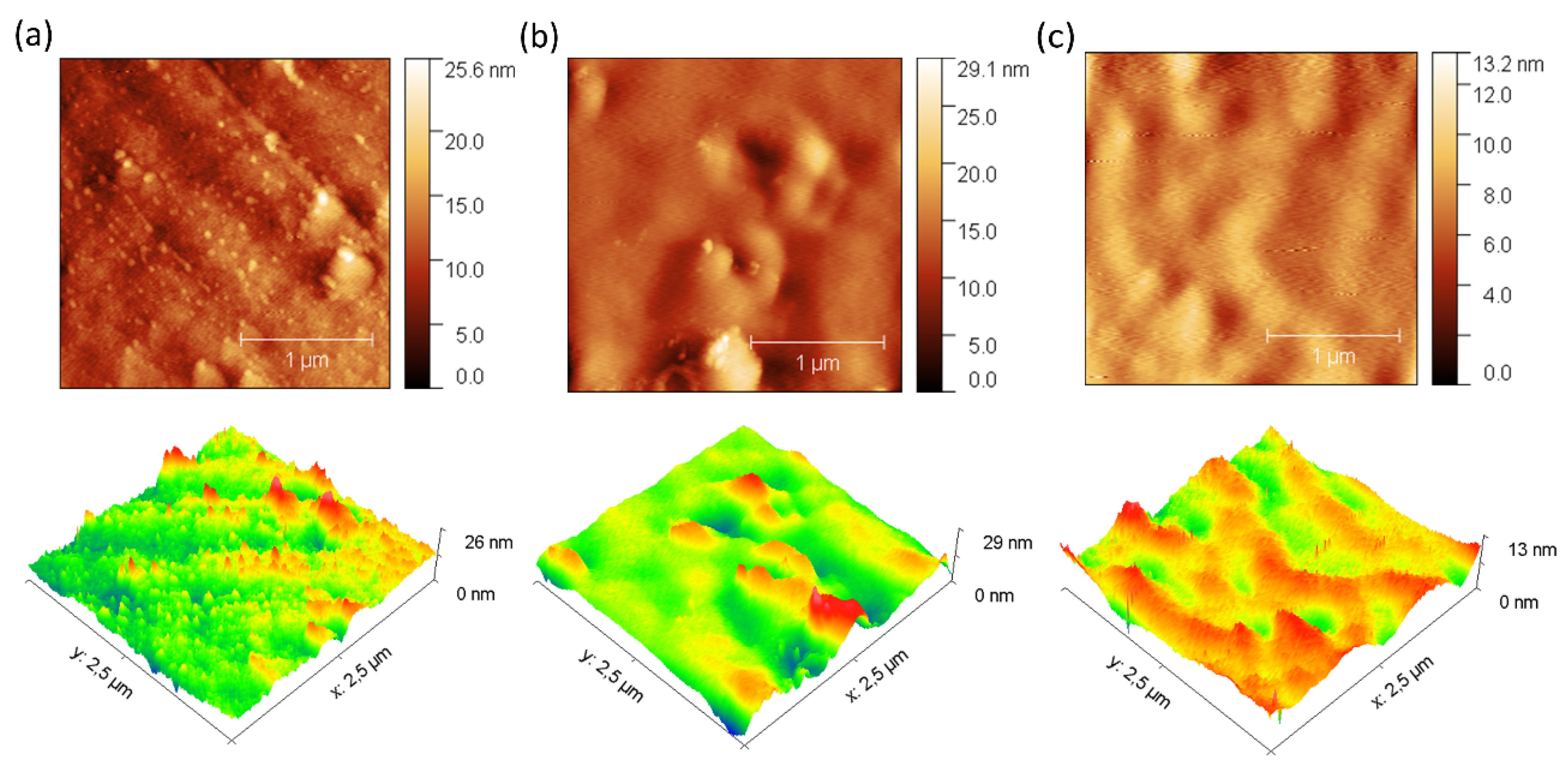

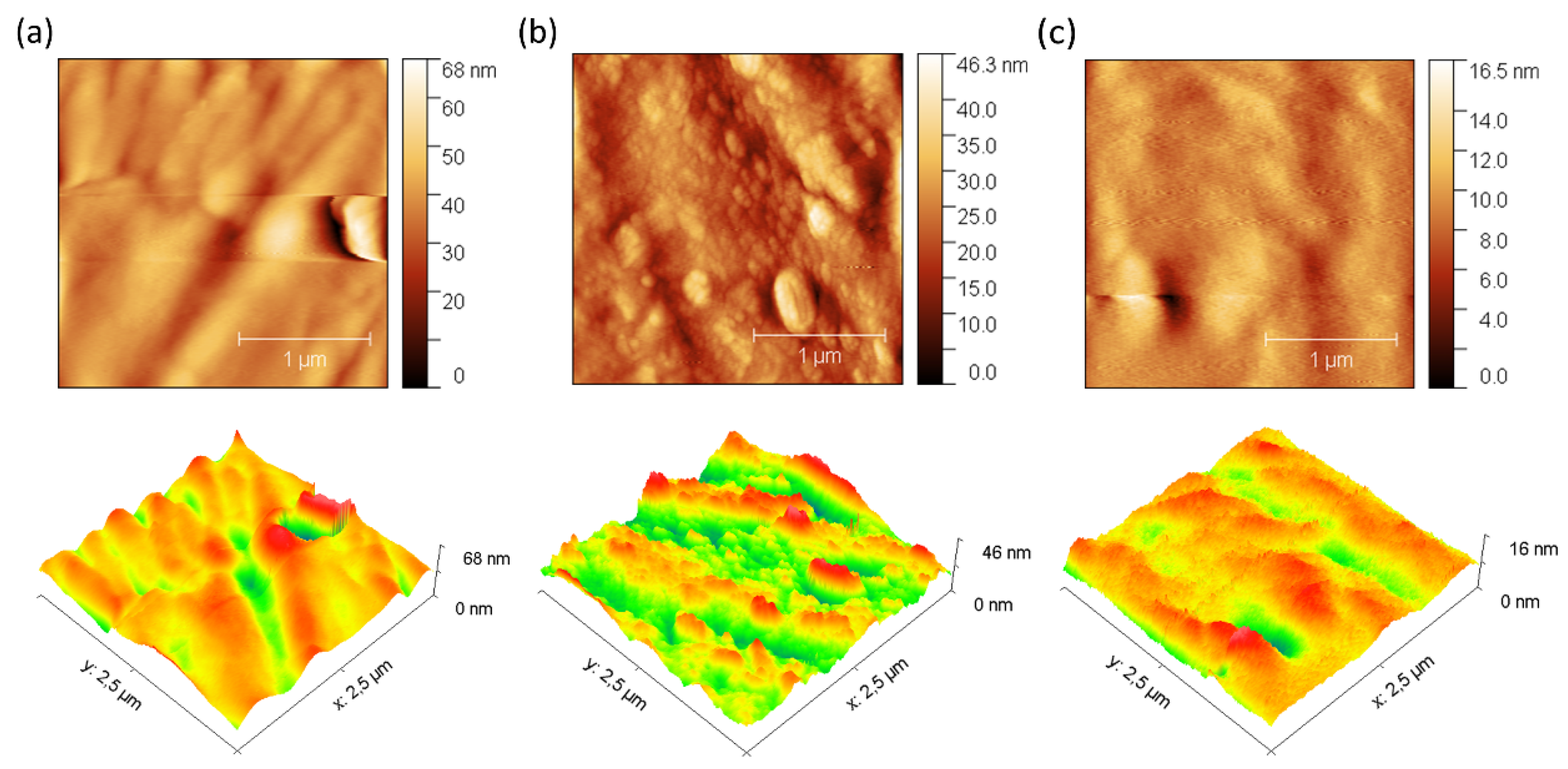

2.8. Anti-Fouling Analysis

The antifouling performance of the membranes was evaluated by observing the changes in surface morphology using an atomic force microscope (AFM; Park Systems, NX10). The samples were initially cut into approximately 1.00 cm squares. The scan size for AFM imaging was 2.5 × 2.5 μm. The average roughness (Ra) of the membranes before and after biofouling was then calculated to evaluate the changes in surface texture [

33,

34].

2.9. Impedance Spectroscopy Characterizations

Impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed after immersing each membrane in bath solution (0.01M HCl) inside the symmetrical electrochemical cell (

Figure 1b). The frequency response analyzer used for the EIS measurements was the potentiostats/galvanostats (Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT302N). A small sinusoidal alternating potential of 10 mV amplitude, was applied over a frequency range of 10 Hz to 100 kHz. The surface area (A) of the membrane exposed to the electrolyte was 1.76 cm² (one side). The membrane was placed at the center (d = 0.500 cm) of the Ag/AgCl electrodes [

35]. Finally, the Nyquist spectra were fitted using the equivalent circuit show in

Figure 1c using ZSimpWin, software (Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Data Analysis Software), where Rs is the bath solution resistance, Zb membrane resistance, Zf resistance due to faradaic processes including interfacial charge transfer resistance and Warburg impedance, Cg and Cd represent geometric capacitance and double layer capacitance, respectively [

36]. The ionic conductivity of the membranes in the longitudinal direction was calculated with the following equation:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Membrane Characterization

3.1.1. Characterization of ZIF-8

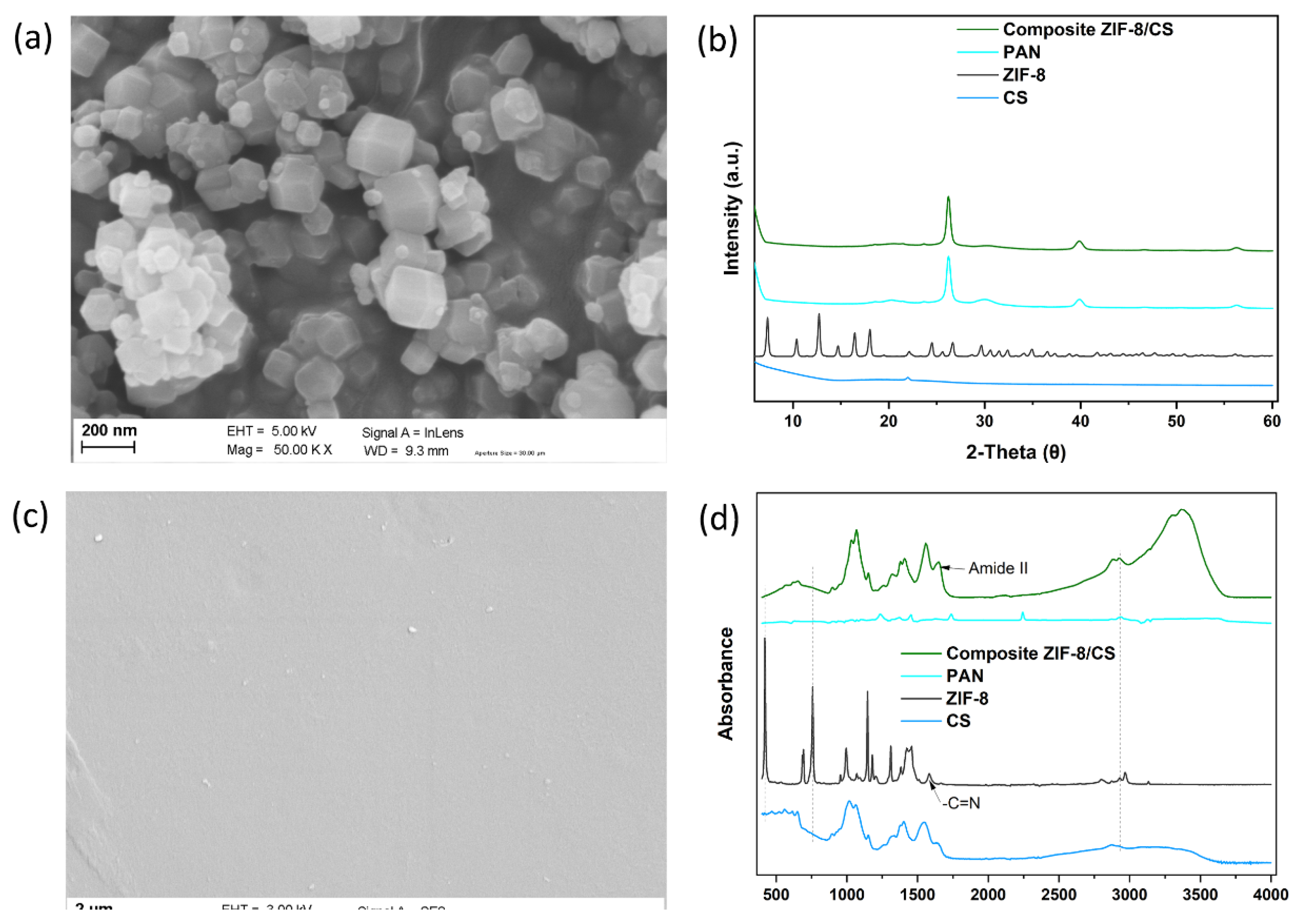

Figure 2a shows the SEM images of the synthesized ZIF-8 particles.

The size of the synthesized ZIF-8 nanoparticles was in the order of 100-200 nm. In addition, small size crystals as nanofillers within the chitosan polymer matrix can reduce the non-selective volumes at the nanofiller/polymer interface, thus high membrane selectivity can be achieved [

37]. XRD analysis showed a crystal structure of ZIF-8 with characteristic peaks at 2θ values of 7.3°, 10.3°, 12.7°, 14.7°, 16.4°, 18.0°, 22.1°, 24.4°, 25.5°, 26.6° 29.6° and 34.9°, as shown in

Figure 2b. The XRD patterns of the synthesized ZIF-8 are in good agreement with those in the literature [

38,

39,

40], indicating that a very crystalline ZIF-8 without impurities was obtained.

3.1.2. Morphology of the Membranes

The composite ZIF-8/CS membranes were characterized by SEM. As seen in

Figure 2c, the membrane had a smooth surface, but with some defects. Furthermore, it shows that the ZIF-8 particles were well dispersed in the CS matrix, with no apparent cracks, indicating a good interface. This indicates good compatibility and uniform interfacial distribution between the ZIF-8 nanofillers and the CS matrix.

3.1.3. XRD Characterizations of ZIF-8/CS Composite Membranes

XRD spectrum for the composite ZIF-8/CS membrane (

Figure 2b) shows the characteristic diffraction peak of CS located at 2θ = 21.9° [

41], demonstrating that the incorporation of ZIF-8 nanofillers did not influence the CS crystal form. Moreover, the composite ZIF-8/CS membrane shows a new peak located around 2θ = 32.1°, indicating the presence of ZIF-8 nanofillers within the overall polymeric matrix [

42].

3.1.4. FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis of Membranes

The chemical functional groups of ZIF-8 nanofiller, pure CS and composite ZIF-8/CS membrane were evaluated by FITR (

Figure 2d). Significant bands were observed at 420, 692, 760, 993, 1146, 1178, 1310, 1357, 1456, 1587, 2799, 2929 and 3134 cm

-1 for the ZIF-8 particulate samples. The peak at 2929 cm

-1 was attributed to asymmetric C-H aliphatic stretching vibration, while the peak at 1587 cm

-1 is due to -C=N stretching vibration. The peak at 760 cm

-1 was associated with the bending vibration of the imidazole ring. The Zn-N stretching vibration was observed at 420 cm

-1, implying that the zinc ions chemically combined with the nitrogen atoms of the methylimidazole groups to form the imidazole ring [

43]. The characteristic peaks in the spectrum of the ZIF-8 nanofiller appeared in the FTIR spectrum of the composite ZIF-8/CS, demonstrating that the ZIF-8 nanofiller was successfully incorporated into the CS matrix.

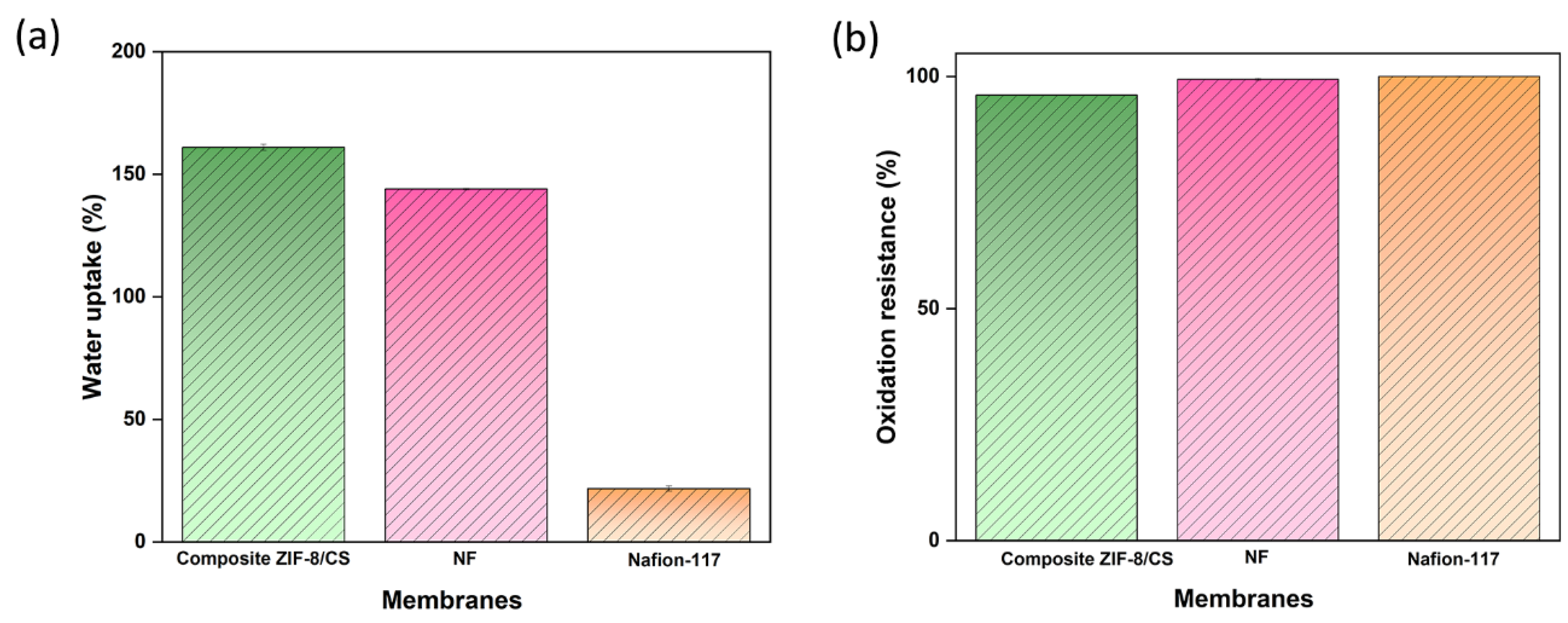

3.2. Water Uptake of the Membrane

The values of percent water absorption of the membranes for 24 hours were 161%, 144% and 21.8% for the samples of composite ZIF-8/CS membrane, NF and Nafion-117, respectively (

Figure 3a).

The composite ZIF-8/CS membrane showed a high level of hydration that can be attributed to the combination of the porous structure of ZIF-8 and the hydrophilic properties of chitosan. The -OH and -NH

2 functional groups present in chitosan can form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, thus increasing the water holding capacity [

44,

45]. The NF membrane showed considerable water absorption capacity, making it particularly suitable for applications in BES. In contrast, the Nafion-117 membrane showed low water sorption capacity. Despite its high ionic conductivity, the lack of a suitable porous structure may restrict its effectiveness in processes that depend on high hydration [

46]. This difference in water absorption capacity highlights the importance of considering membrane microstructure when selecting materials to optimize membrane performance.

3.3. Durability Test

Nafion-117, NF and composite ZIF-8/CS membranes showed 100%, 99.4% and 96.0 % of oxidation resistance, respectively, after exposure to Fenton’s reagent (

Figure 3b).

Although both composite ZIF-8/CS and NF membranes exhibited comparable stability, their resistance to oxidation was inferior compared to Nafion-117. Nevertheless, the membrane matrix remained intact after 192 hours under extreme conditions. This stability was attributed to the greatest stability of ZIF-8 and the antioxidant properties of chitosan [

47,

48]. These properties help protect the membrane from peroxyl radicals generated during the operation of the bioelectrochemical system (BES), potentially extending its service life [

35,

49,

50].

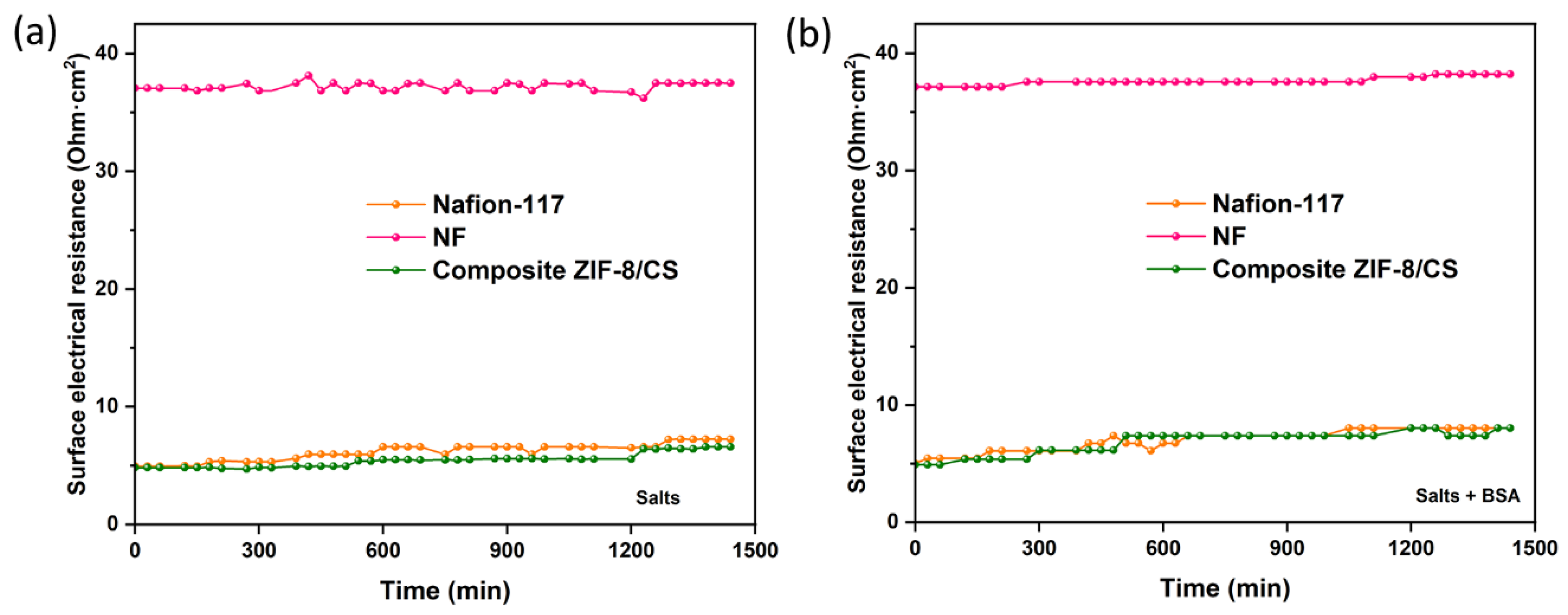

3.4. Surface Electrical Resistance and Anti-Fouling Evaluation

We found, surface electrical resistance values for the active area of the membrane of: 4.91 Ωcm² for composite ZIF-8/CS membrane, 5.03 Ωcm

2 for Nafion-117 and 37.1 Ωcm² for NF. The composite ZIF-8/CS membrane has the lowest surface electrical resistance among three kinds of membranes. This difference could be attributed to the materials present in the mixed matrix membrane structure: The composite ZIF-8/CS membrane contains ZIF-8 nanofillers, a very porous material that could increase the active surface area of the membrane by better distributing the ions in the CS matrix. Moreover, they can act as an efficient channel for ion transport, improving the performance of the composite ZIF-8/CS. In addition, CS exhibits good ionic conductivity in wet media due to the presence of amino (-NH

2) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups in its structure, which can protonate in acidic conditions, facilitating the transport of protons (H

+) in contact with the membrane matrix [

12,

51,

52].

The antifouling property of the membranes was evaluated by the variation of the electrical resistance of the membranes as a function of time, as shown in

Figure 4.

Fouling is caused by the accumulation of organic molecules and salts on the surface of the membrane or within its pores [

53]. In ours experiments, bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as an organic contaminant. Organic BSA has a volume of 84.5 nm³ and a slight negative density of charge, which increases its mobility in solution and its probability of collision on the membrane surface [

54]. The results suggest that there is a slight increase in the surface electrical resistance of the membranes when they come into contact with BSA (

Figure 4b). Conversely, no significant variation in electrical resistance was observed over time when exposed to salts (

Figure 4a), suggesting minimal fouling by salts. This increase in electrical resistance is likely attributed to membrane surface fouling.

In addition, 3D images obtained by AFM were used for a detailed investigation of the surface morphology before and after fouling of the membranes with BSA (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The data obtained reveal remarkable differences in the behavior of the ZIF-8/CS membrane compared to the other membranes analyzed.

Table 1 presents the mean roughness (Ra) and maximum height (Sz) values for the three membranes analyzed previously. A significant increase in Sa and Sz was observed for all membranes after fouling, as shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. In particular, the composite ZIF-8/CS membrane, although showing a minor absolute change compared to the Nafion-117 and NF membrane, shows an increase of 25.88% in Sa and 26.02% in Sz. Although these changes are less compared to those observed in Nafion-117 (179.48% in roughness) and NF (117.12%), they indicate that the ZIF-8/CS composite membrane is more resistant to fouling by BSA. The lower susceptibility of the ZIF-8/CS composite membrane to fouling suggests that its surface properties are more effective in reducing protein adsorption. This not only improves its performance, but also implies greater viability for long-term applications [

54,

55,

56].

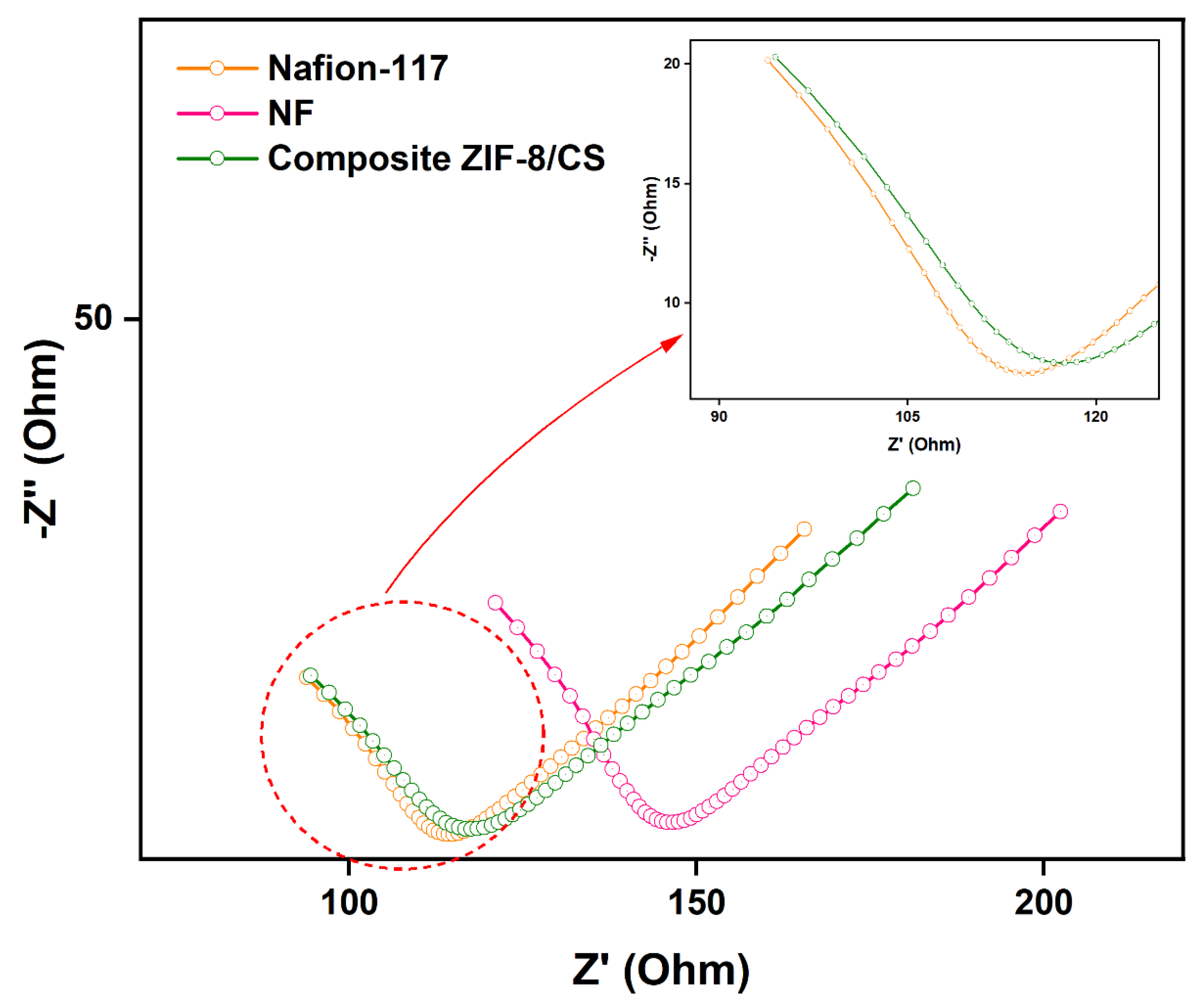

3.5. Impedance Spectroscopy

The Nyquist plots show in

Figure 7 have two distinctive parts, at high frequencies a resistance-capacitor loop, meanwhile at low frequencies a Warburg element is observed.

The deviation from the onset of the Warburg loop in each membrane reflects the kinetic influence of ion transport toward the membrane/electrolyte interface and into the membrane matrix [

57]. The decrease in frequencies for the onset of Warburg impedance (

Figure 7), suggests that Nafion-117 and composite ZIF-8/CS membrane have higher ionic conductivity and lower resistances (Zb) compared to NF membranes, due to the delayed access of the electrolyte to the polymeric network of NF membranes (

Table 2) [

58]. Furthermore, the increased ionic conductivity in the composite ZIF-8/CS could be attributed to a higher surface area, possibly related to the addition of Zif-8 in the chitosan polymeric matrix, leading to higher ionic activity and transport [

22,

59].

4. Conclusions

The ZIF-8/CS composite membrane exhibits similar performance to Nafion-117 and NF membranes but stands out for its superior water retention, excellent thermal and oxidative stability, low surface resistance, and effective antifouling properties. Additionally, its comparable ionic conductivity to Nafion-117 (0.105 S/cm), combined with its biodegradability and lower cost, positions it as a promising alternative for sustainable bioelectrochemical applications. While studies on its direct implementation in BES remain scarce, these findings open new avenues for exploring its use in microbial fuel cells, desalination, CO₂ capture, and water purification technologies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research department of the Universidad Central del Ecuador (Cif8Fuce-ce-fcq-1) and the Renewable Energy Research Laboratory of the School of Chemical Sciences for the support and facilities provided during the execution of this research project.

References

- K. Penzy et al., “Industrial wastewater irrigation increased higher heavy metals uptake and expansins, metacaspases, and cystatin genes expression in Parthenium and maize,” Environ Monit Assess, vol. 195, no. 12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Singh, A. Chakraborty, and R. Sehgal, “A systematic review of industrial wastewater management: Evaluating challenges and enablers,” J Environ Manage, vol. 348, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Sheikh, H. R. Harami, M. Rezakazemi, J. L. Cortina, T. M. Aminabhavi, and C. Valderrama, “Towards a sustainable transformation of municipal wastewater treatment plants into biofactories using advanced NH<inf>3</inf>-N recovery technologies: A review,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 904, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Wu, Z. Zhang, Y. Luo, Y. Bai, and J. Fan, “Bioremediation of phenolic pollutants by algae - current status and challenges,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 350, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Abbasi, M. Ahmadi, and M. Naseri, “Quality and cost analysis of a wastewater treatment plant using GPS-X and CapdetWorks simulation programs,” J Environ Manage, vol. 284, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. J. González-Pabón, R. Cardeña, E. Cortón, and G. Buitrón, “Hydrogen production in two-chamber MEC using a low-cost and biodegradable poly(vinyl) alcohol/chitosan membrane,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 319, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Bajracharya et al., “An overview on emerging bioelectrochemical systems (BESs): Technology for sustainable electricity, waste remediation, resource recovery, chemical production and beyond,” Renew Energy, vol. 98, pp. 153–170, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Uduma, K. L. Oguzie, C. F. Chijioke, T. E. Ogbulie, and E. E. Oguzie, “Bioelectrochemical technologies for simultaneous treatment of dye wastewater and electricity generation: a review,” International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, vol. 20, no. 9, pp. 10415–10434, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Abbassi and A. K. Yadav, Introduction to microbial fuel cells: challenges and opportunities. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Min, J. Kim, S. Oh, J. M. Regan, and B. E. Logan, “Electricity generation from swine wastewater using microbial fuel cells,” Water Res, vol. 39, no. 20, pp. 4961–4968, 2005. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Chae, M. Choi, F. F. Ajayi, W. Park, I. S. Chang, and I. S. Kim, “Mass transport through a proton exchange membrane (Nafion) in microbial fuel cells,” Energy and Fuels, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 169–176, 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Oliot, S. Galier, H. Roux de Balmann, and A. Bergel, “Ion transport in microbial fuel cells: Key roles, theory and critical review,” Appl Energy, vol. 183, pp. 1682–1704, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Chae, M. J. Choi, J. Lee, F. F. Ajayi, and I. S. Kim, “Biohydrogen production via biocatalyzed electrolysis in acetate-fed bioelectrochemical cells and microbial community analysis,” Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 33, no. 19, pp. 5184–5192, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Rozendal, H. V. M. Hamelers, K. Rabaey, J. Keller, and C. J. N. Buisman, “Towards practical implementation of bioelectrochemical wastewater treatment,” Trends Biotechnol, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 450–459, 2008. [CrossRef]

- B. Van Der Bruggen, A. Koninckx, and C. Vandecasteele, “Separation of monovalent and divalent ions from aqueous solution by electrodialysis and nanofiltration,” Water Res, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 1347–1353, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Moorthy, B. Maria Mahimai, D. Kannaiyan, and P. Deivanayagam, “Synthesis and fabrication of Cu-trimesic acid MOF anchored sulfonated Poly(2,5-benzimidazole) membranes for PEMFC applications,” Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 48, no. 92, pp. 36063–36075, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B.-C. Jonathan, M. Kim, and J. R. Kim, “Bioelectricity Generation Using a Crosslinked Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) and Chitosan (CS) Ion Exchange Membrane in Microbial Fuel Cell,” Journal of Electrochemical Science and Technology, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 303–310, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Mukoma, B. R. Jooste, and H. C. M. Vosloo, “Synthesis and characterization of cross-linked chitosan membranes for application as alternative proton exchange membrane materials in fuel cells,” J Power Sources, vol. 136, no. 1, pp. 16–23, 2004. [CrossRef]

- P. Srinophakun, A. Thanapimmetha, S. Plangsri, S. Vetchayakunchai, and M. Saisriyoot, “Application of modified chitosan membrane for microbial fuel cell: Roles of proton carrier site and positive charge,” J Clean Prod, vol. 142, pp. 1274–1282, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Li et al., “MOFs meet membrane: application in water treatment and separation,” Mater Chem Front, vol. 7, no. 21, pp. 5140–5170, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Zornoza, C. Tellez, J. Coronas, J. Gascon, and F. Kapteijn, “Metal organic framework based mixed matrix membranes: An increasingly important field of research with a large application potential,” Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, vol. 166, pp. 67–78, 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, Y. Hartanto, D. Nikolaeva, Z. He, S. Chergaoui, and P. Luis, “High-performance ZIF-8/biopolymer chitosan mixed-matrix pervaporation membrane for methanol/dimethyl carbonate separation,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 293, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Leus et al., “Systematic study of the chemical and hydrothermal stability of selected ‘stable’ Metal Organic Frameworks,” Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, vol. 226, pp. 110–116, 2016. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, G. Van Eygen, Y. Hartanto, B. Van der Bruggen, and P. Luis, “Nanostructural modulation of chitosan matrix for facilitating transport of organic molecules across the membrane by pervaporation,” J Memb Sci, vol. 706, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Abu-Saied, E. A. El-Desouky, E. A. Soliman, and G. A. El-Naim, “Novel sulphonated poly (vinyl chloride)/poly (2-acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulphonic acid) blends-based polyelectrolyte membranes for direct methanol fuel cells,” Polym Test, vol. 89, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Veiga and A. M. Moraes, “Study of the swelling and stability properties of chitosan-xanthan membranes,” J Appl Polym Sci, vol. 124, no. SUPPL. 1, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Qiao, M. Saito, K. Hayamizu, and T. Okada, “Degradation of Perfluorinated Ionomer Membranes for PEM Fuel Cells during Processing with H[sub 2]O[sub 2],” J Electrochem Soc, vol. 153, no. 6, p. A967, 2006. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhao, B. L. Yi, H. M. Zhang, and H. M. Yu, “MnO2/SiO2-SO3H nanocomposite as hydrogen peroxide scavenger for durability improvement in proton exchange membranes,” J Memb Sci, vol. 346, no. 1, pp. 143–151, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Schauer and L. Brožová, “Heterogeneous ion-exchange membranes based on sulfonated poly(1,4-phenylene sulfide) and linear polyethylene: Preparation, oxidation stability, methanol permeability and electrochemical properties,” J Memb Sci, vol. 250, no. 1–2, pp. 151–157, 2005. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu and B. E. Logan, “Electricity generation using an air-cathode single chamber microbial fuel cell in the presence and absence of a proton exchange membrane,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 38, no. 14, pp. 4040–4046, 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. Bahamonde Soria, J. Zhu, I. Gonza, B. Van der Bruggen, and P. Luis, “Effect of (TiO2: ZnO) ratio on the anti-fouling properties of bio-inspired nanofiltration membranes,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 251, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, R. Fu, Z. Liu, and H. Wang, “Low-resistance anti-fouling ion exchange membranes fouled by organic foulants in electrodialysis,” Desalination, vol. 417, pp. 1–8, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Madih, A. H. El-Shazly, M. F. Elkady, A. N. Aziz, M. E. Youssef, and R. E. Khalifa, “A facile synthesis of cellulose acetate reinforced graphene oxide nanosheets as proton exchange membranes for fuel cell applications,” Journal of Saudi Chemical Society, vol. 26, no. 2, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Rahimpour, S. S. Madaeni, and S. Mehdipour-Ataei, “Synthesis of a novel poly(amide-imide) (PAI) and preparation and characterization of PAI blended polyethersulfone (PES) membranes,” J Memb Sci, vol. 311, no. 1–2, pp. 349–359, 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. Schauer and L. Brožová, “Heterogeneous ion-exchange membranes based on sulfonated poly(1,4-phenylene sulfide) and linear polyethylene: Preparation, oxidation stability, methanol permeability and electrochemical properties,” J Memb Sci, vol. 250, no. 1–2, pp. 151–157, Mar. 2005. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang and U. E. Spichiger, “Impedance study of Mg2+-selective membranes,” Electrochim Acta, vol. 45, no. 14, pp. 2259–2266, 2000. [CrossRef]

- S. Yu et al., “Elevated pervaporation performance of polysiloxane membrane using channels and active sites of metal organic framework CuBTC,” J Memb Sci, vol. 481, pp. 73–81, 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. A. H. M. Nordin, A. F. Ismail, A. Mustafa, P. S. Goh, D. Rana, and T. Matsuura, “Aqueous room temperature synthesis of zeolitic imidazole framework 8 (ZIF-8) with various concentrations of triethylamine,” RSC Adv, vol. 4, no. 63, pp. 33292–33300, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Devrim, S. Erkan, N. Baç, and I. Eroǧlu, “Preparation and characterization of sulfonated polysulfone/titanium dioxide composite membranes for proton exchange membrane fuel cells,” Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 3467–3475, 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Casado-Coterillo, A. Fernández-Barquín, B. Zornoza, C. Téllez, J. Coronas, and Á. Irabien, “Synthesis and characterisation of MOF/ionic liquid/chitosan mixed matrix membranes for CO<inf>2</inf>/N<inf>2</inf> separation,” RSC Adv, vol. 5, no. 124, pp. 102350–102361, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang et al., “Synthesis of nano-ZIF-8@chitosan microspheres and its rapid removal of p-hydroxybenzoic acid from the agro-industry and preservatives,” Journal of Porous Materials, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 29–38, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Khajavian, E. Salehi, and V. Vatanpour, “Nanofiltration of dye solution using chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol)/ZIF-8 thin film composite adsorptive membranes with PVDF membrane beneath as support,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 247, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hu, H. Kazemian, S. Rohani, Y. Huang, and Y. Song, “In situ high pressure study of ZIF-8 by FTIR spectroscopy,” Chemical Communications, vol. 47, no. 47, pp. 12694–12696, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Khajavian, E. Salehi, and V. Vatanpour, “Chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol thin membrane adsorbents modified with zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) nanostructures: Batch adsorption and optimization,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 241, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Luo, S. Rojas-Carbonell, Y. Yan, and A. Kusoglu, “Structure-transport relationships of poly(aryl piperidinium) anion-exchange membranes: Eeffect of anions and hydration,” J Memb Sci, vol. 598, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Banerjee, R. K. Calay, and F. E. Eregno, “Role and Important Properties of a Membrane with Its Recent Advancement in a Microbial Fuel Cell,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 2, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Yin, H. Kim, J. Choi, and A. C. K. Yip, “Thermal stability of ZIF-8 under oxidative and inert environments: A practical perspective on using ZIF-8 as a catalyst support,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 278, pp. 293–300, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Abd El-Hack et al., “Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of chitosan and its derivatives and their applications: A review,” Dec. 01, 2020, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- B. Mattsson, H. Ericson, L. M. Torell, and F. Sundholm, “Degradation of a fuel cell membrane, as revealed by micro-Raman spectroscopy,” Electrochim Acta, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 1405–1408, 2000. [CrossRef]

- G. Hübner and E. Roduner, “EPR investigation of HO· radical initiated degradation reactions of sulfonated aromatics as model compounds for fuel cell proton conducting membranes,” J Mater Chem, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 409–418, 1999. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhu, R. S. Kingsbury, D. F. Call, and O. Coronell, “Impact of solution composition on the resistance of ion exchange membranes,” J Memb Sci, vol. 554, pp. 39–47, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lai, “Development of ZIF-8 membranes: opportunities and challenges for commercial applications,” Curr Opin Chem Eng, vol. 20, pp. 78–85, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhai et al., “Effect of Na+ on organic fouling depends on Na+ concentration and the property of the foulants,” Desalination, vol. 531, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. O. Mahlangu et al., “Role of permeate flux and specific membrane-foulant-solute affinity interactions (∆Gslm) in transport of trace organic solutes through fouled nanofiltration (NF) membranes,” J Memb Sci, vol. 518, pp. 203–215, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, J. Wang, Y. Zhang, Q. Zhang, K. Huo, and C. Han, “Breaking the trade-off between selectivity and permeability of nanocomposite membrane modified by UIO66@PDA through nonsolvent thermally induced phase separation method,” Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, vol. 130, pp. 306–316, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M.-J. Choi et al., “Effects of biofouling on ion transport through cation exchange membranes and microbial fuel cell performance,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 102, no. 1, pp. 298–303, 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Balakrishnan and K. R. V. Subramanian, Nanostructured ceramic oxides for supercapacitor applications. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Montalvillo et al., “Charge and dielectric characterization of nanofiltration membranes by impedance spectroscopy,” J Memb Sci, vol. 454, pp. 163–173, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xing, H. Li, and G. Avgouropoulos, “Research progress of proton exchange membrane failure and mitigation strategies,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 10, 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).