Submitted:

06 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

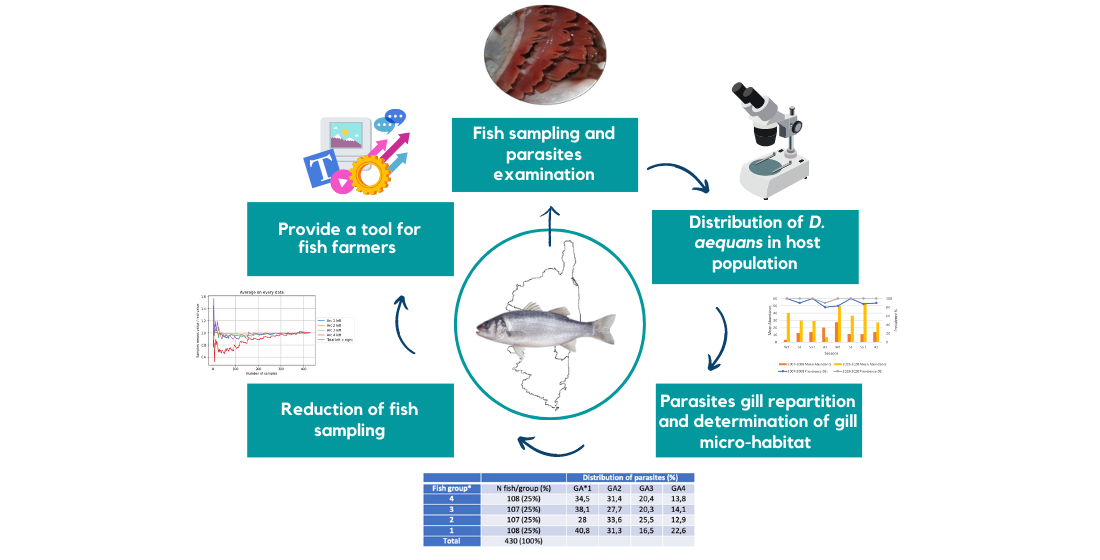

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

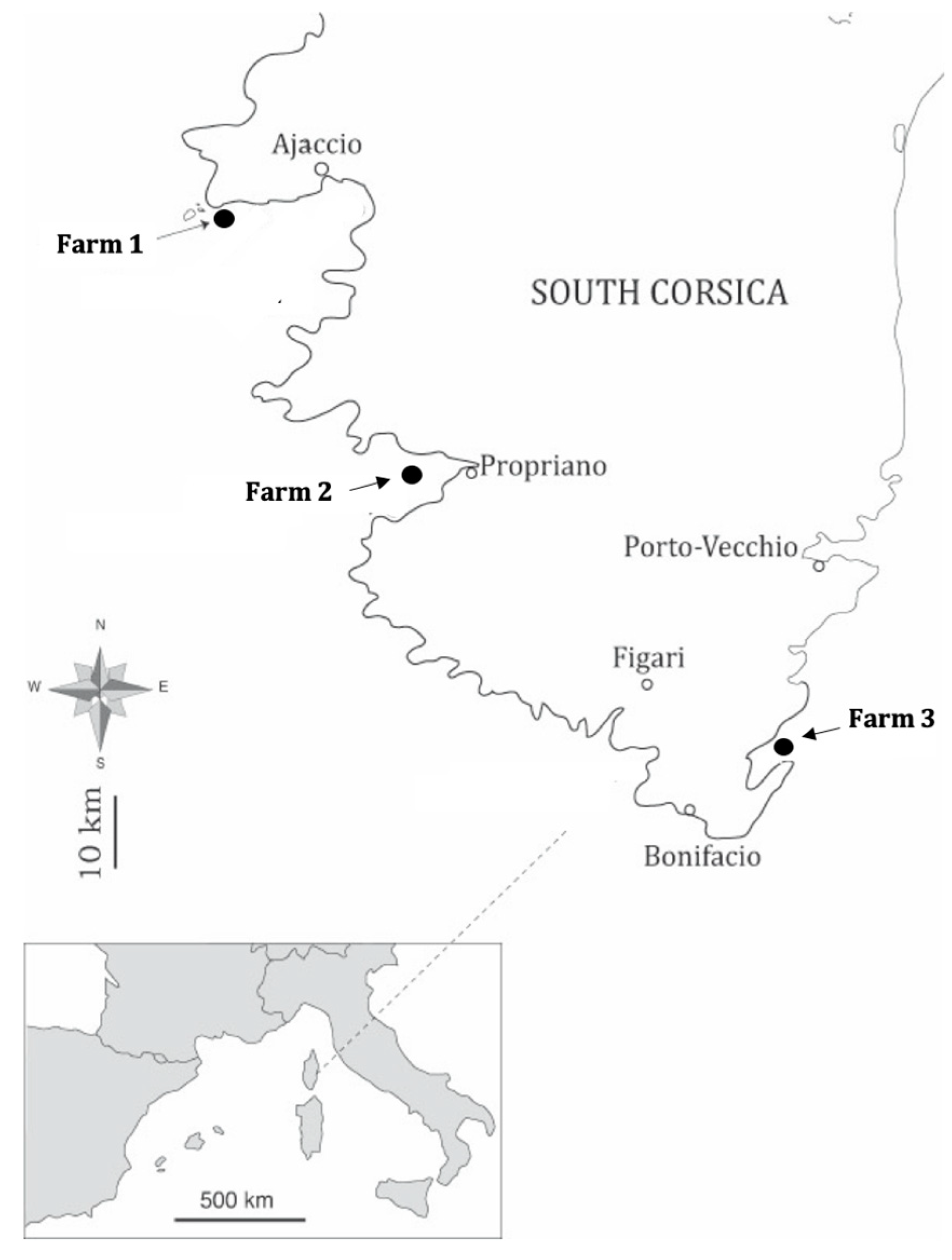

2.1. Fish Sampling and parasites examination

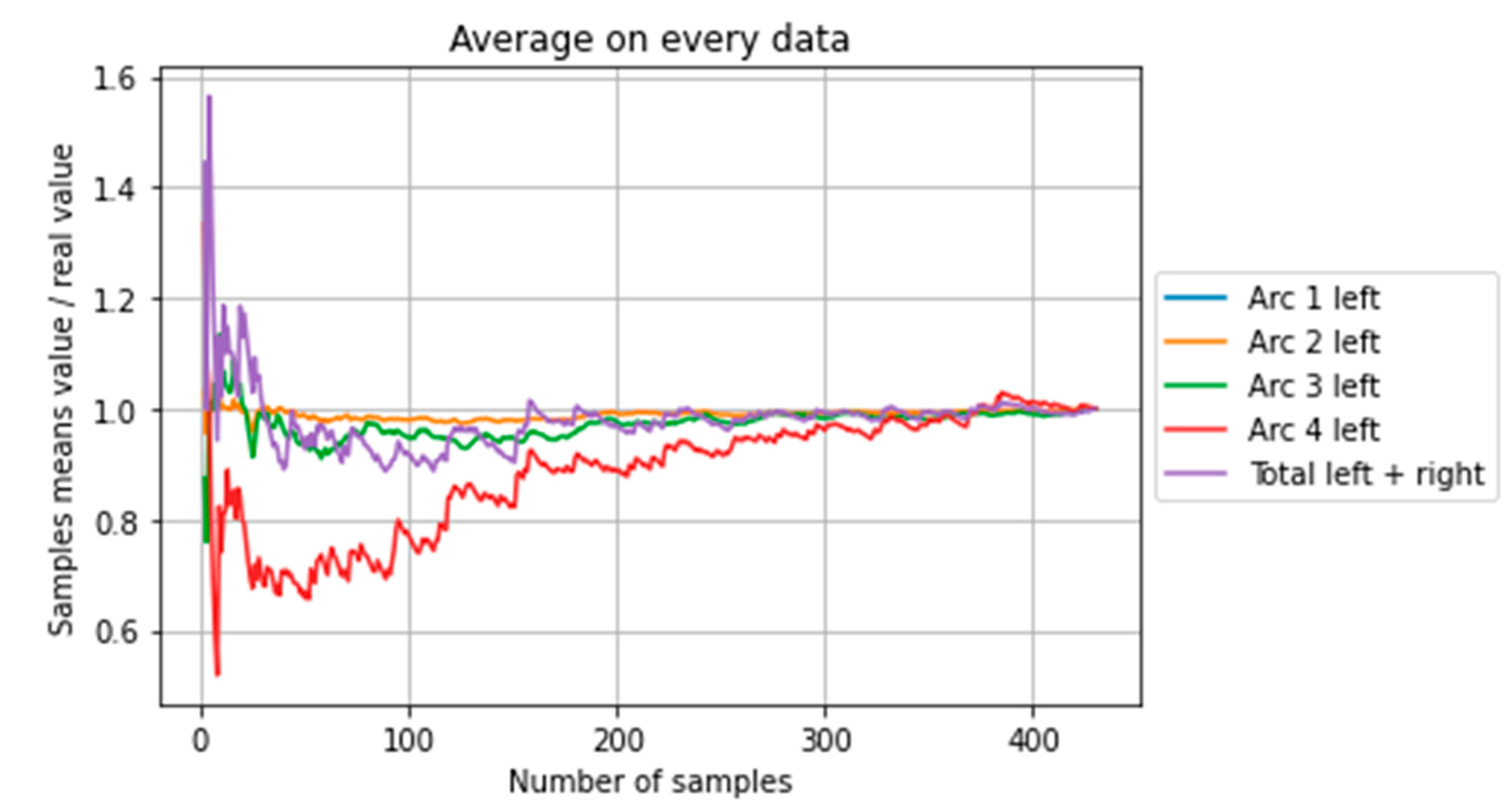

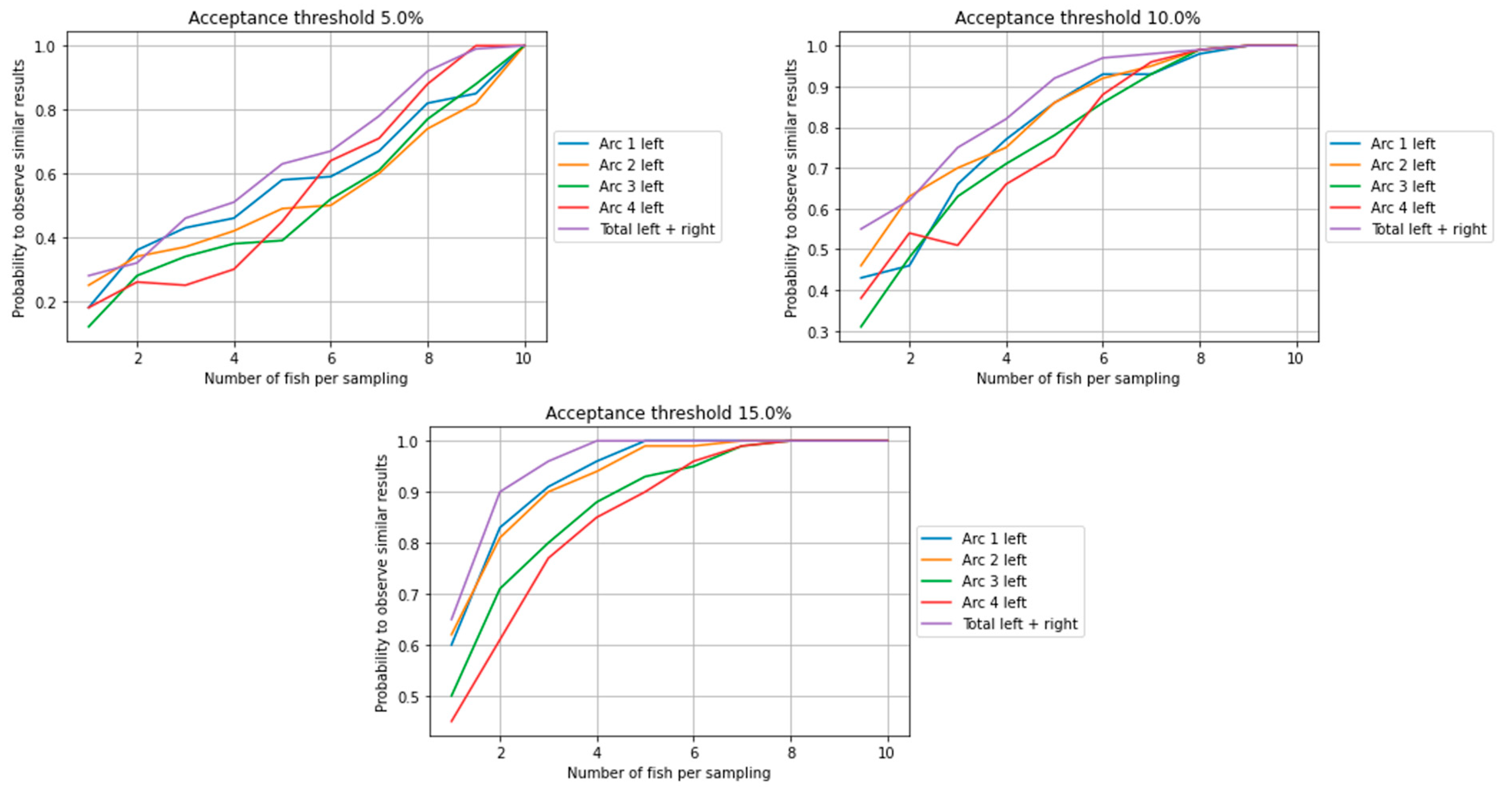

2.2. Statistical analyses

3. Results

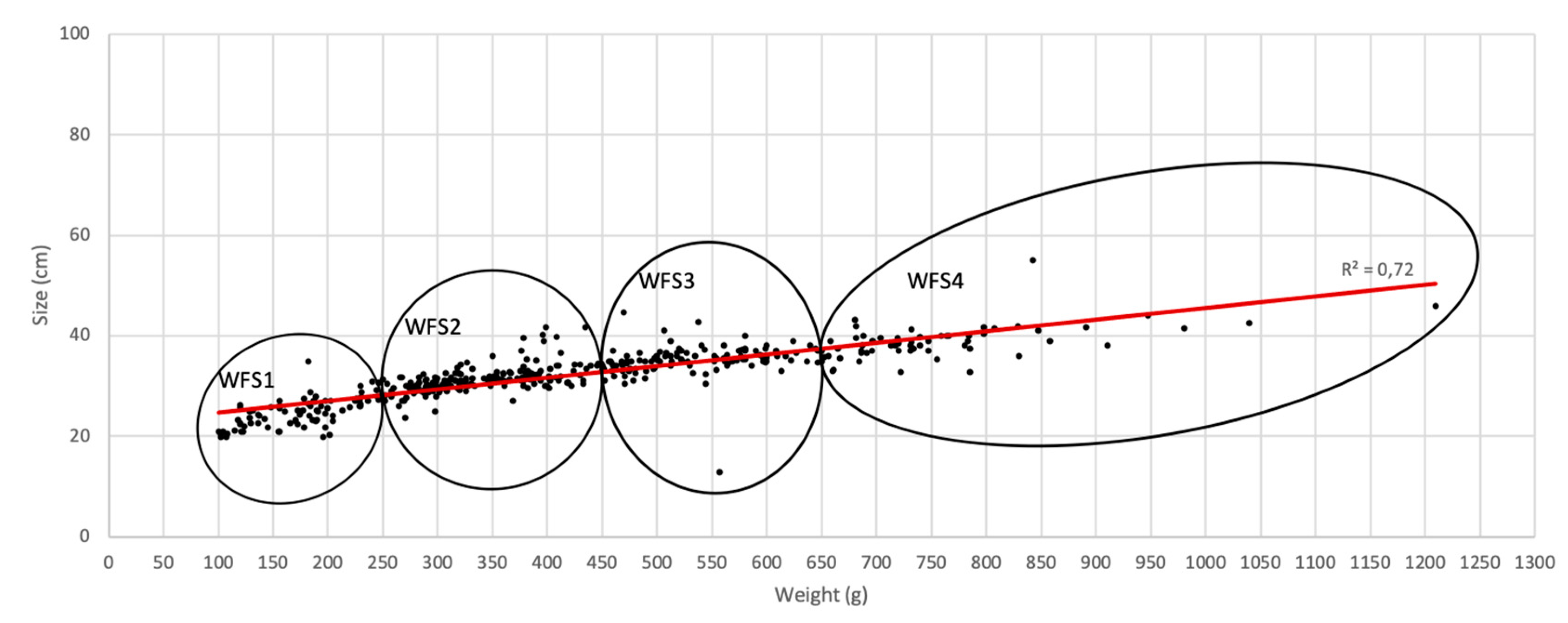

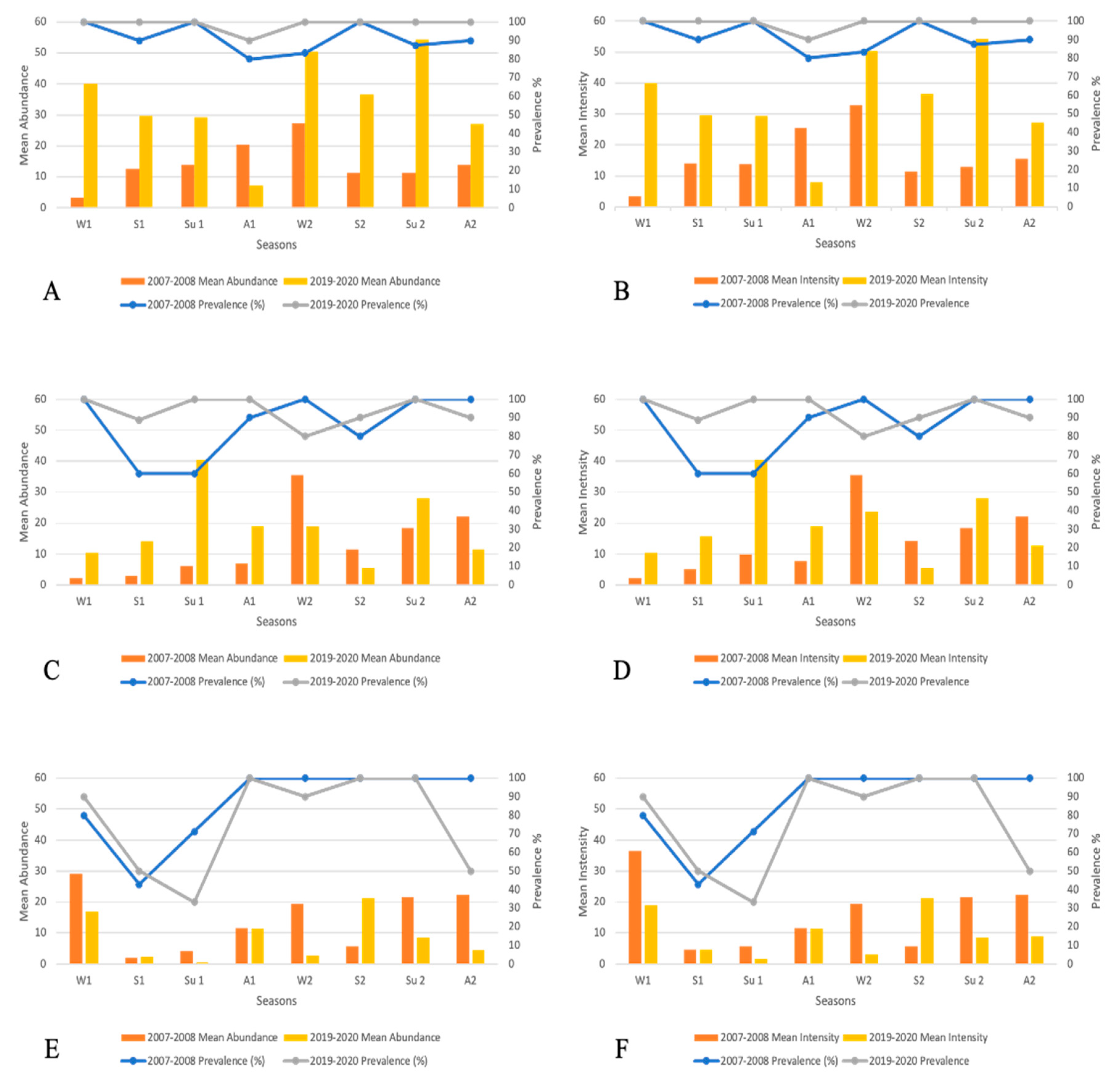

3.1. Distribution of D. aequans in host population

3.2. Parasite distribution on gills

4. Discussion

4.1. Distribution of D. aequans in host population

4.2. Parasite distribution on gills

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- F.A.O. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Published by FAO. Rome, 2020; p. 244.

- Lanza, G.R.; Wilda, K.M.; Bunluesin, S.; Panich-Pat, T. Green Aquaculture: designing and developing aquaculture systems integrated with phytoremediation treatment options. Phytoremediation. 2017, 5, 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, F.; Onofri, L.; Fezzardi, D. Aquaculture in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea: a Blue Growth perspective. Nunes PALD, Svensson LE, Markandy A (Eds). Handbook on the Economics and Management of Sustainable Oceans, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham and Northampton, UK, 2017; pp. 93–123.

- Mare & Stagni Corsi. Syndicat des Aquaculteurs Corses. Cahier des charges Label Rouge LA 01-11« Bar d’aquaculture marine ». 2011, p. 29.

- Lia, R.P.; Zizzo, N.; Tinelli, A.; Lionetti, C.; Cantacessi, C.; Otranto, D. Mass mortality in wild greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili) infected by Zeuxapta seriolae (Monogenea: Heteraxinidae) on the Jonian Sea. Bull. Eur. Ass. Fish. Pathol. 2007, 27, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Merella, P.; Cherchi, S.; Garippa, G.; Fioravanti, M.L.; Gustinelli, A.; Salati, F. Outbreak of Sciaenacotyle panceri (Monogenea) on cage-reared meagre Argyrosomus regius (Osteichtyes) from the western Mediterranean Sea. Dis. of Aquat. Org. 2009, 86, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ternengo, S.; Agostini, S.; Quilichini, Y.; Euzet, L.; Marchand, B. Intensive infestations of Sciaenocotyle pancerii (Monogenea, Microcotylidae) on Argyrosomus regius (Asso) under fish farming conditions. J. Fish. Dis. 2010, 33, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, L. Impact du parasitisme sur la pisciculture en Corse. Suivi des parasitoses et étude des transferts de parasites depuis la faune sauvage vers les poissons élevés en mer ouverte. Thèse, Université de Corse, Pasquale Paoli, 2010.

- Antonelli, L.; Marchand, B. Metazoan parasites of the European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax (Linnaeus 1758) (Pisces: Teleostei) from Corsica. In: Health and Environment in Aquaculture. Edited by Edmir Daniel Carvalho, Gianmarco Silva David and Reinaldo J. Silva, InTech, 2012; pp. 43–62.

- Dezfuli, B.S.; Giari, L.; Simoni, E.; Menegatti, R.; Shinn, A.P.; Manera, M. Gill histopathology of cultured European sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.), infected with Diplectanum aequans (Wagener 1857) Diesing 1958 (Diplectanidae: Monogenea). Parasitol. Res. 2007, 100, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragoni, G.; Romestand, B.; Trilles, J.P. Parasitoses à Cymothoidiens chez le loup Dicentrarchus labrax Linnaeus (1758) en élevage. 1. Ecologie parasitaire dans le cas de l’étang de Diana (Haute-Corse) (Isopoda, Cymothoidae). Crustaceana. 1984, 44, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, S.; Saroglia, M.; Berni, P.; Cognetti-Varriale, A.M. Influence of temperature on the life cycle of Diplectanum aequans (Monogenea, Diplectanidae), parasitic on sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.). J. Fish. Dis. 1998, 21, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimo, M.; Volpatti, D.; Galeotti, M.; E Bron, J.; Beraldo, P. New insights into the host parasites interactions of Amyloodiniosis in European sea-bass: a multi modal approach. Pathogens 2022, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merella, P.; Garippa, G.; Salati, F. Parasites of cage cultured European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax and gilthead sea bream Sparus aurata from Sardinia (western Mediterranean): first results. Parassitologia. 2006, 48, 290. [Google Scholar]

- Muniesa, A.; Basurco, B.; Aguilera, C.; Furones, D.; Reverté, C.; Sanjuan-Vilaplana, A.; Jansen, M.D.; Brun, E.; Tavorpanich, S. Mapping the knowledge of the main diseases affecting sea bass and sea bream in Mediterranean. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, G. Study of Diplectanum aequans (Wagener, 1957) Diesing, 1858 (Monogenea, Monopisthocotylea, Diplectanidae) with a scanning electronic microscope. Z. Parasitenkd. 1976, 51, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.O.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lotz, J.M. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagnelie, P. Analyses statistiques à plusieurs variables, Presses agronomiques de Gembloux, Bruxelles. 1975.

- Sprent, P. Pratique des statistiques non paramétriques, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Paris. 1992.

- Gonzalez-Lanza, C.; Alvarez-Pellitero, P.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A. Diplectanidae (Monogenea) infestations on sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.), from the Spanish area. Histopathology and population dynamics under culture conditions. Parasitol. Res. 1991, 77, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, L.; Quilichini, Y.; Marchand, B. Sparicotyle chrysophrii (Van Beneden and Hesse 1863) (Monogenea: Polyopisthocotylea) parasite of cultured Gilthead sea-bream Sparus aurata (Linnaeus 1758) (Pisces: Teleostei) from Corsica: ecological and morphological study. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 107, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, L.; Quilichini, Y.; Marchand, B. Biological study of Furnestinia echeneis Euzet and Audouin 1959 (Monogenea: Monopisthocotylea: Diplectanidae), parasite of cultured Gilthead sea-bream Sparus aurata (Linnaeus 1758) (Pisces: Teleostei) from Corsica. Aquaculture. 2010, 307, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, L.; Foata, J.; Quilichini, Y.; Marchand, B. Influence of season and site location on European cultured sea bass parasites in Corsican fish farms using indicator species analysis (IndVal). Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winger, A.C.; Kanck, M.; Kristoffersen, R.; Knudsen, R. Seasonal dynamics and persistence of Gyrodactylus salaris in two riverine anadromous Arctic charr populations. Environ. Biol. Fish. 2008, 83, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, J.; Van Oosterhout, C. The impact of parasites on the life history evolution of guppies (Poecilia reticulate): the effects of host size on parasite virulence. Int. J. Parasitol. 2007, 13, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, R.; Rohde, K. Comparing the richness of metazoan ectoparasite communities of marine fishes: controlling for host phylogeny. Oecologia. 1997, 110, 278–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silan, P.; Maillard, C. Biologie comparée du développement et discrimination des Diplectanidae ectoparasites du Bar (Teleostei). Ann. Sci. Nat. Zool. Biol. Ani. 1989, 10, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marcogliese, D.J. Implications of climate change for parasitism of animals in the aquatic environment. Can. J. Zool. 2001, 79, 1331–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Lanza, C.; Alvarez-Pellitero, P.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A. Diplectanidae (Monogenea) infestations on sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.), from the Spanish area. Histopathology and population dynamics under culture conditions. Parasitol. Res. 1991, 77, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladineo, M. Monogenean parasites in Adriatic cage-reared fish. Acta. Adriat. 2004, 45, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, R.; Shinn, A.P.; Grenfell, S.E.; Bron, J.E.; Burnell, G.; Cool, E.J.; Crumlish, M.; Culloty, S.; Davidson, K.; Ellis, R.P.; Flynn, K.J. Review of climate change impacts on marine aquaculture in the UK and Ireland. Aquat. Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2012, 22, 389–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, A.; Rintamäki, P.; Jokela, J.; Valtonen, E.T. Increasing water temperature and disease risks in aquatic systems: climate change increases the risk of some, but not all, diseases. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010, 40, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobert, S.; Fullgrabe, L.; Lejeune, P.; Marengo, M. Climate change and fisheries: the case study of Corsica, an ideal reference station in the Mediterranean Sea. Aquac. Fish. Stud. 2020, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Adloff, F.; Somot, S.; Sevault, F.; Jordà, G.; Aznar, R.; et al. Mediterranean Sea response to climate change in an ensemble of twenty first century scenarios. Clim. Dyn. 2015, 45, 2775–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Caroli, F.; Guidetti, P.; Morri, C. Seawater warming at the northern reach for southern species: Gulf of Genoa, NW Mediterranean. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U.K. 2018, 98, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F. 2006. Climate change hot-spots. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33-L08707, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Piroddi, C.; Coll, M.; Liquete, C.; Macias, D.; Greer, K.; Buszowski, J.; Steenbeek, J.; Danovaro, R. , Christensen, V. Historical changes of the Mediterranean Sea ecosystem: modelling the role and impact of primary productivity and fisheries changes over time. Sci. rep. 2017, 7, 44491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, M.L.; Canziani, O.F.; Palutokof, J.P.; Van der Linden, P.J.; Hanson, C.E. IPCC. 2007. Climate change 2007: Impacts, Adapatation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmantal Panel on Climate Change. Cambrdige University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 2007; pp. 976.

- Kapsenberg, L.; Alliouane, S.; Gazeau, F.; Mousseau, L.; Gattuso, J.P. Costal ocean acidification and increasing total alkalinity in the Northwestern Mediterranean sea. Ocean Sci. 2017, 13, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavia, D.; Field, J.C.; Boesch, D.F.; Buddemeier, R.W.; Burkett, V.; Cayan, D.R.; Fogarty, M.; Harwell, M. Climate change impacts on the US coastal and marine ecosystems. Estuaries. 2002, 25, 149–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, L.; Foata, J.; Quilichini, Y.; Marchand, B. Influence of season and site location on European cultured sea bass parasites in Corsican fish farms using indicator species analysis (IndVal). Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvell, C.D.; Mitchell, C.E.; Ward, J.R.; Altize,r S. ; Dobson, A.P.; Ostfeld, R.S.; Samuel, M.D. Climate warming and diseases risks for territorial and marine biota. Science. 2002, 5576, 2158–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodhain, F. Modifications climatiques : impact potentiel sur la santé, l’exemple des maladies à vecteur. Bull. Assoc. Anc. Elèves Inst. Pasteur. 2000, 162, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Marcogliese, D.J. 2008. The impact of climate change on the parasites and infectious diseases of aquatic animals. Rev.- Off. Int. Epizoot. 2008, 27, 467–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, A.; Thieltges, D.W.; Poulin, R. Parasites and global warming: net effects of temperature on an intertidal host-parasite system. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 415, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, J.; Palomera, I.; Salat, J.; Solé, I. Impact of fresh-water input and wind on landings of anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) and sardine (Sardina pilchardus) in shelf-waters surrounding the Ebre (Ebro) River delta (north-western Mediterranean). Fish. Oceanogr. 2004, 13, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, S.C.; Fast, M.D.; Kuparinen, A.; Medcalf, K.E.; Hutchings, J.A. Increasing tempeartures accentuate negative fitness consequences of a marine parasite. Sci. rep. 2020, 10, 18467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminot, A.; Kerouel, R. Hydrologie des écosystèmes marins: paramètres et analyses. Collection Méthodes d’analyse en milieu marin, 2004, IFREMER, p. 336.

- Devreker, D.; Souissi, S.; Winkler, G.; Forget-Leray, J.; Leboulenger, F. Effects of salinity, temperature and individual variability on the reproduction of Eurytemora affinis (Copepoda; Calanoida) from the Seine estuary: A laboratory study. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol, 2009, 368, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krkosek, M. Host densities thresholds and disease control for fisheries and aquaculture. Aquacul. Environ. Interact. 2010, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhaduzzaman, A.M.; Hanif, A.; Khan, S.; Osma, M.H.; Shovon, N.H.; Rahman, K.; Ahmed, S.B. Perfect stocking density ensures best production and economic returns in floating cages aquaculture system. J. of Aquac. Res. Development. 2020, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, P.J.; Rizzoli, A.; Grenfell, B.T.; Heesterbeek, H.; Dobson, A.P. The ecology of wildlife diseases. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2001, p. 216.

- Ravenni, G. Infestation by Diplectanum aequans (Wagener 1857) Diesing 1858 in cultured sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). Riv. Ital. Piscic-Ittiopatol. 1983, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, A.; Maillard, C. Gill repartition of two Monogenea: Diplectanum aequans (Wagener 1857) Diesing 1958 and D. laubieri Lambert and Maillard 1974 (Monogenea, Monopisthocotylea) simultaneous parasites of the sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1975, 50, 691–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cognetti-Varriale, A.M.; Castelli, A.; Cecchini, S.; Saroglia, M. Distribution of Diplectanum aequans (Monogenea) on the gills of intensively reared seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax, L.). Bull. Eur. Ass. Fish Pathol. 1992, 13, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Liu, J.; Gibson, D.I.; Dong, A. Spatial distributions of two species of monogeneans on the gills of Siganus Fuscescens (Houttuyn) and their seasonal dynamics in caged versus wild caught-hosts. J. Parasitol. 2006, 95, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagge, A.M.; Sasal, P.; Valtonen, E.T.; Karvonen, A. Infracommunity level aggregation in the monogenean communities of crucian carp (Carassius Carassius). Parasitology. 2005, 131, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskivaara, M.; Valtonen, E.T.; Vuori, K.M. Microhabitat distribution and coexistence of Dactylogyrus species (Monogenea) on the gills of roach. Parasitology. 1991, 104, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombi, J.; Bilong Bilong, C.F. Distribution of gill parasites of the freshwater fish Barbus martorelli Roman, 1971 (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) and tendency to inverse intensity evolution between Myxosporidia and Monogenea as a function of the host age. Rev. élev. méd. vét. Pays trop. 2004, 57, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simková, A.; Verneau, O.; Gelnar, M.; Morand, S. Specificity and specialization of congeneric Monogenans parasiting Cyprinid. Evolution. 2006, 60, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Morand, S.; Simková, A.; Matějusová, I.; Plaisance, L.; Verneau, O.; Desdevises, Y. Investigating patterns may reveal processes: evolutionary ecology of ectoparasitic monogeneans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002, 32, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, M.E.; Luque, J.L. 1998. Distribution patterns of Microcotyle nemadactylus (Monogenea) on gill filaments of Cheilodatylus variegatus (Teleostei). Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 1998, 93, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombi, J.; Akoumba, J.F.; Bilong Bilong, C.F. The monogenean community on the gills of Oreochromis niloticus from Melen fish station in Yaounde, Cameroon. Int. J. Mod. Biol. Res. 2014, 2, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arme, C.; Halton, D.W. Observations on the occurrence of Diclidophora merlangi (Trematoda:Monogenea) on the gills of whiting, Gadus merlangus. J. of Fish. Biol. 1972, 4, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, P.A.; Martorelli, S.R. Seasonality, distribution, and preference sites of Demidospermus valenciennesi Gutiérrez et Suriano, 1992 (Monogenea: Ancyrocephalidae) in catfish. Res. Rev. Parasitol. 1994, 54, 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hanek, G.; Fernando, C.H. Spatial distribution of gill parasites of Lepomis Gibbosus (L.) and Ambloplites rupestris (Raf.). Can. J. Zool. 2011, 56, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbin, T.P.; Vanhove, P.M.; Seehausen, O.; Maan, M.E. Microhabitat distributions and species interactions of ectoparasites on the gills of cichlid fish in Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Farm 1 | Farm 2 | Farm 3 | Mean T(°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | W | 14.2 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.13 |

| S | 17.1 | 20.3 | 20.6 | 19,33 | |

| Su | 25.5 | 22.4 | 24.3 | 24,1 | |

| A | 17.7 | 21.7 | 21.5 | 20,3 | |

| Mean T (°C) | 18.63 | 19.63 | 20.13 | ||

| 2008 | W | 13.7 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 13.5 |

| S | 18.8 | 20.5 | 20.8 | 20.03 | |

| Su | 24.8 | 24.9 | 24.8 | 24.83 | |

| A | 21 | 20.4 | 22.6 | 21.33 | |

| Mean T (°C) | 19.6 | 19.8 | 20.4 | ||

| 2019 | W | 14 | 14.5 | 14 | 14.2 |

| S | 15 | 18.1 | 19.8 | 17.63 | |

| Su | 26 | 26.2 | 28.2 | 26.8 | |

| A | 21 | 23.1 | 24 | 22.7 | |

| Mean T (°C) | 19 | 20.5 | 21.5 | ||

| 2020 | W | 14 | 14 | 15.7 | 14.6 |

| S | 18 | 19 | 19.6 | 18.9 | |

| Su | 25 | 28 | 27 | 26.7 | |

| A | 18 | 24 | 23.8 | 21.9 | |

| Mean T (°C) | 18.8 | 21.3 | 21.5 |

| Fish group [Weight (g)] | N fish/group (%) | Prevalence (%) | Mean abundance (± SD) | Mean intensity (± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFS*4 ]543-1210] | 108 (25%) | 75 | 21.4 (± 21.7) | 24.1 ± (22.8) |

| WFS3 ]381-543] | 107 (25%) | 81 | 19.5(± 21.7) | 21.3 ± (22.6) |

| WFS2 ]278-381] | 107 (25%) | 79 | 19.1 (± 21.8) | 21.1 ± (22.8) |

| WFS1 [100-278] | 108 (25%) | 66 | 14.6 (± 19.8) | 17.2 ± (21.3) |

| Prevalence | Abundance | Intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | (p) | Mean | ±SD | U test (p) | Mean | ±SD | U test (p) | |

| 2007-2008 | 4.74 | 0.029 | 16.07 | 4.93 | 0.026 | 18.24 | 5.87 | 0.02 |

| 2019-2020 | 33.52 | 15.8 | 33.63 | 15.58 | ||||

| Prevalence | Abundance | Intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | (p) | Mean | ±SD | U test (p) | Mean | ±SD | U test (p) | |

| 2007-2008 | 2.09 | 0.148 | 14.96 | 11.47 | 0.38 | 16.17 | 10.55 | 0.46 |

| 2019-2020 | 19.67 | 11.58 | 20.77 | 11.36 | ||||

| Prevalence | Abundance | Intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | (p) | Mean | ±SD | U test (p) | Mean | ±SD | U test (p) | |

| 2007-2008 | 4.66 | 0.031 | 11.48 | 8.27 | 0.26 | 12.35 | 7.3 | 0.32 |

| 2019-2020 | 7.34 | 7.22 | 8.5 | 6.6 | ||||

| Mean abundance (± SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Left (L) | Right (R) | |

| GA1 | 3.37 (±5,02) | 3.17 (± 4,55) |

| GA2 | 2.91 (± 4.07) | 2.81 (± 4.13) |

| GA3 | 2.07 (±3.21) | 1.81 (± 2.8) |

| GA4 | 1.37 (±2.75) | 1.14 (± 2.35) |

| Total | 9.71 (±12.28) | 8.99 (±11.45) |

| U test | p=0.68 | |

| Distribution of parasites (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish group* | N fish/group (%) | GA*1 | GA2 | GA3 | GA4 |

| 4 | 108 (25%) | 34,5 | 31,4 | 20,4 | 13,8 |

| 3 | 107 (25%) | 38,1 | 27,7 | 20,3 | 14,1 |

| 2 | 107 (25%) | 28 | 33,6 | 25,5 | 12,9 |

| 1 | 108 (25%) | 40,8 | 31,3 | 16,5 | 22,6 |

| Total | 430 (100%) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).