1. Introduction

Soil and water conservation (SWC) practices have been given a high priority and attention, which is the main effect of improving soil fertility and reducing soil erosion. Soil and water conservation practices play a great role in promoting sustainable soil quality and productivity (Deng and Shangguan, 2021). It is not only related to the improvement of soil fertility, but also the sustainable development of the agricultural sector and the economy of the country at large (Tilahun, 2019; Abiye, 2022). Moreover, it is vital to reduce soil erosion and runoff velocity, trap sediment and nutrients, improve water quality, enhance downstream water, reduce sedimentation and improve land productivity (Belayneh et al., 2019). However, SWC practices are not effective in the developing countries because of different socioeconomic factors such as lack of finance, lack of training, and farmers’ perception (Asfaw and Neka, 2017). Furthermore, it results in a major variation of soil physicochemical properties (Assaye, 2020).

Land degradation and soil erosion remains one of the biggest environmental problems in the world, particularly in the developing countries (Lal, 2014). It is the main problem forcing agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa (Wolka and Negash, 2014). Besides, land degradation and soil erosion are the major challenges that adversely affect agricultural production in Ethiopia (Belay and Van Rompaey, 2015). Furthermore, soil erosion and land degradation have adverse effects on soil physicochemical properties (Belayneh et al., 2019). Soil erosion accelerates the degradation of land that occurs through water and wind erosion (Hurni et al. 2016; Seifu and Elias, 2018). The majority of the farmers in rural areas are subsistence oriented in cultivation of crops, but the cultivated lands are impoverished soils that are highly susceptible to soil erosion (Shiene, 2012). The average annual rate of soil loss in cultivated lands is 42 t ha−1 yr−1 in Ethiopia (Hurni, 1993). Moreover, the average soil loss rate on steep slopes is 300 t ha−1 yr−1 where vegetation cover is scant and lack of SWC practices areas (Hailu et al., 2012). The main factors that initiate the degradation of land and soil erosion in the Agemi watershed include chemical fertilizer, lack of SWC practices and removal of crop residues from cultivated lands. Although several research efforts on evaluating the effect of SWC practices on soil physicochemical properties (Erkossa et al., 2018, Guadie et al., 2020, Sinore and Doboch, 2021) have been made in different parts of Ethiopia, empirical evidence is limited in the Agemi watershed. The findings of this study play an essential role in providing relevant evidence for policy-makers on the impacts of different SWC practices on soil properties and insuring food security. Hence, this study explored the effect of SWC practices and slope gradient on soil physicochemical properties in the Agemi watershed of northwestern Ethiopia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

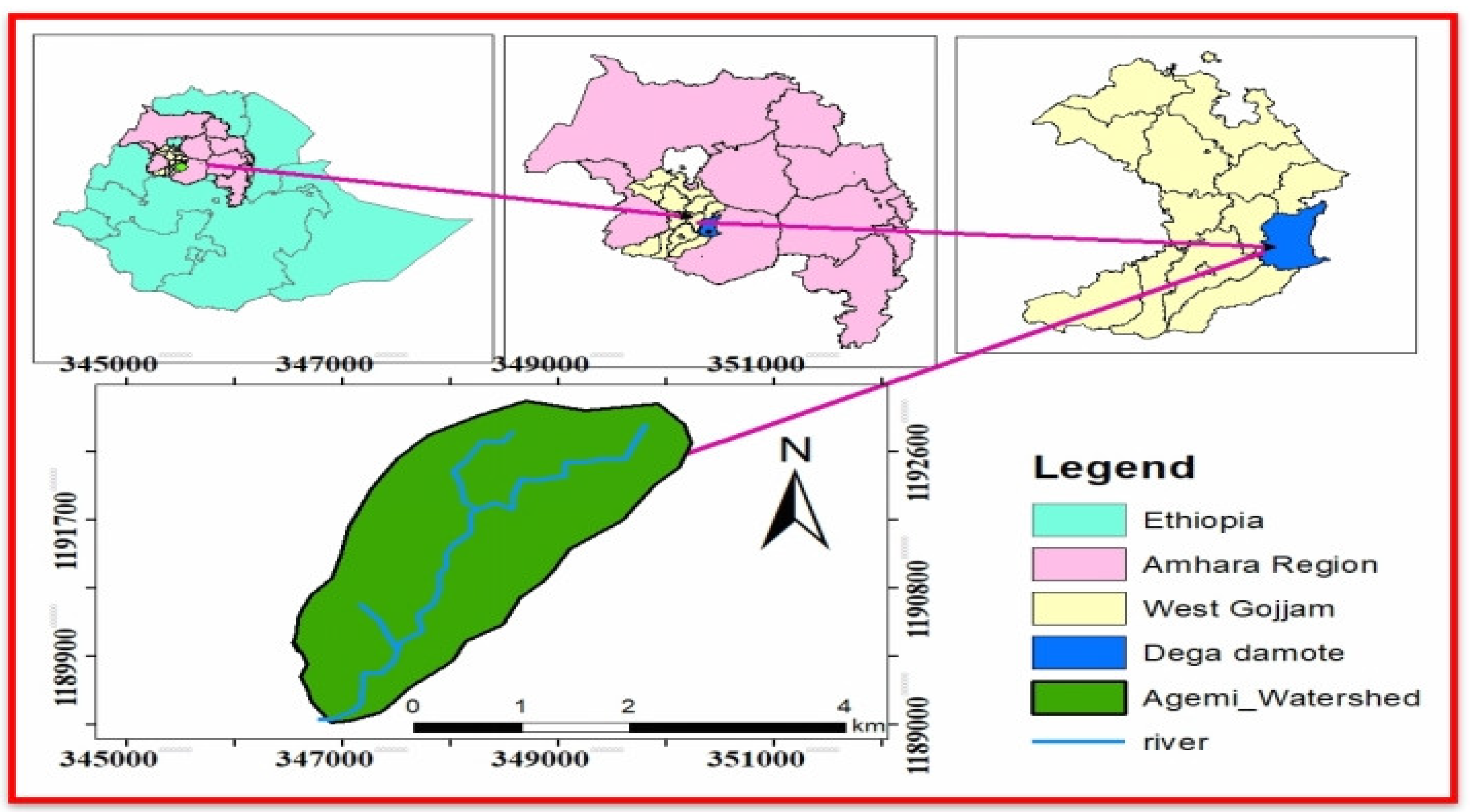

The study was conducted in the Agemi watershed of northwestern Ethiopia (

Figure 1). The Agemi watershed, which is situated at 10° 45’ 10.57” north and 37° 35’ 58.41” east. The altitude ranges from 2372-2880 masl. It is far from 400 km northwest of Addis Ababa. Moreover, the area of the watershed covers about 798 ha (

Figure 1).

Topographically, the study area is mountainous (25%), undulated (50%), valleys (10%) and plains (15%). Based on FAO classification (2006), the soil of the district is Nitosols (19.5%), Andosols (0.5%), Leptosols (25%), Vertisols (35%) and Luvisols (20%). The dominant soil of the watershed is Nitosols, which are deep, well-drained and red tropical soils (FAO, 2006). According to

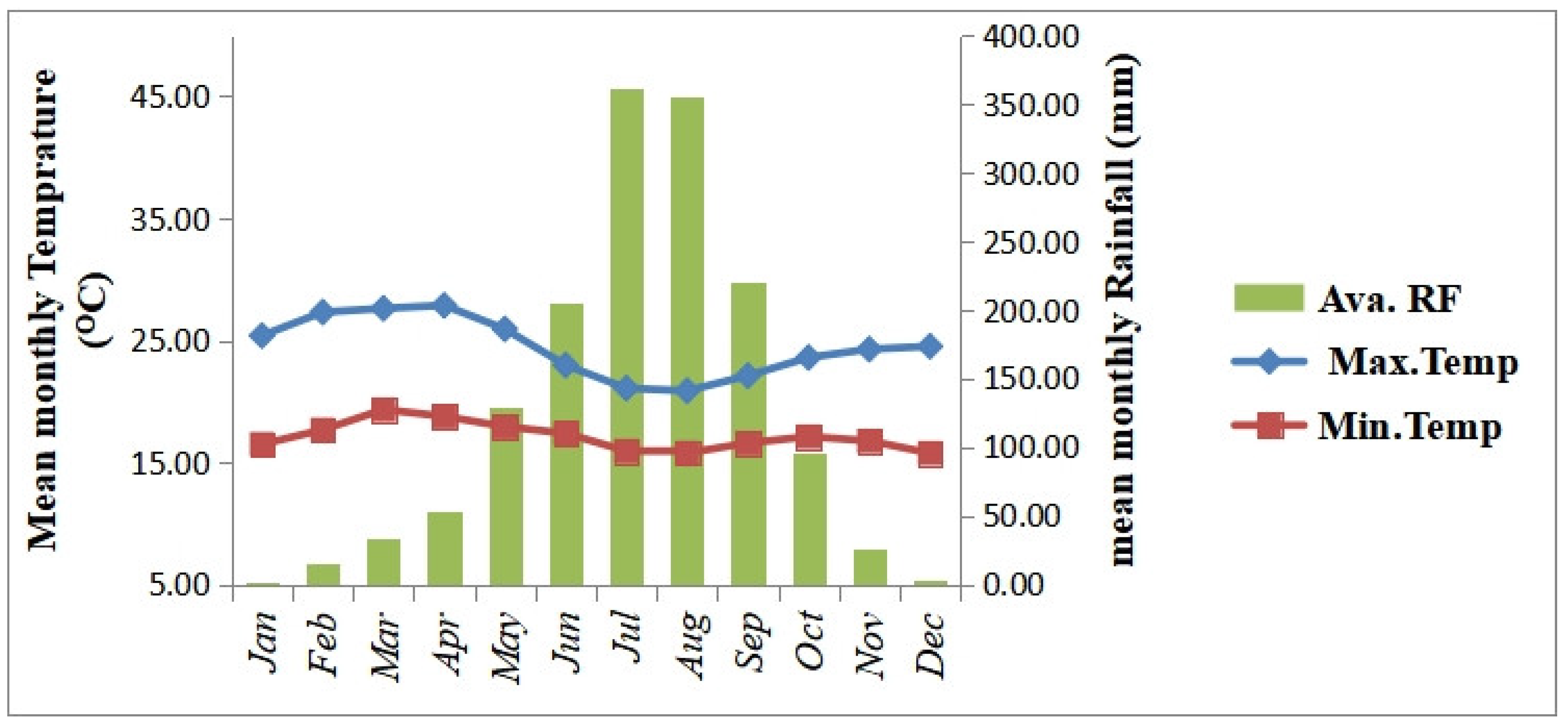

the national meteorology agency data obtained from Bahir Dar branch (2000-2019), the annual mean average rainfall is 1200 to 1800 mm (

Figure 2). Also, the lower and higher temperatures are 17.15 °C and 24.48 °C, respectively (

Figure 2).

2.2. Preparation of Soil Samples

A preliminary survey was carried out for general understanding and to identify slope gradients, farmland treated with SWC practices and untreated farmland in the study site. Accordingly, three slope classes include lower (5-10%), middle (10-15%), upper slope class (>15), treated farmland with stone-faced soil bund (SFSB), soil bund (SB) and untreated farmland were identified in the study area. Hence, the soil samples were collected both treated and untreated farmland with three slope classes. Soil samples were collected to scale down by 0.5m from the upper bund and scale up by 0.5m from the lower bund between two successive bunds (Belayneh et al., 2019). The soil samples were carefully isolated from unwanted materials like gravel soil, plant and animal residues from the soil samples. Both soils of disturbed and undisturbed samples were collected at the top of 0-20cm soil depth from four corners and one center of square plots. The undisturbed soil samples were taken using a core sampler of known volume to determine the bulk density of soil. Whereas disturbed soil samples were taken using an auger for the analysis of soil physicochemical properties. Thus, one-kilogram of composite soil samples were collected for each sample plot. Therefore, 27 soil samples were collected from the three slope classes and three farmlands with three replications. Then, the soil samples were air dried, crushed and passed in to a 2 mm sieve for all parameters excluding total nitrogen and organic carbon that passed through a 0.5 mm sieve.

2.3. Analysis of Soil Physicochemical Properties

Bulk density of the soil was estimated using a core sampler and the soil was oven dried at 105 °C for 24 hours (Black, 1965). According to Brady & Weil (2008), the total porosity (TP) of the soil was calculated by Equation (1). Soil texture was analyzed using the hydrometer method (Bouyoucos, 1962).

Soil pH (H2O) was measured using a pH meter with a 1:2.5 soil-to-water ratio (Van Reeuwijk, 2002). Organic carbon was determined by dichromate oxidation methods, while the soil organic matter was the percentage of organic carbon by 1.724 (Sertsu & Bekele, 2000). Total nitrogen was determined by the micro-Kjeldahl digestion, distillation and titration method (Bremner & Mulvaney, 1982). Available phosphorus was determined by the Olsen method (Olsen et al., 1954). Exchangeable Ca and Mg were measured by an atomic absorption spectrophotometer, while exchangeable Na and K were measured by a flame photometer (Rowell, 1994). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined by leaching of ammonium acetate (Chapman, 1965). The percent base saturation of the soils was calculated as the content of basic cations divided by CEC (Bohn et al., 2001).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The effects of soil and water conservation (SWC) practices on slope gradients on the soil properties were statistically analyzed using the two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following the procedure of SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, 2008). The mean separation was done using the least significant difference (LSD) at a 5% of significant level.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of SWC Practices and Slope Gradient on Soil Physicochemical Properties

3.1.1. Soil Texture

Soil texture showed a significant variation between SWC practices (treated) and untreated farmland with slopes (

Table 1). The content of sand in treated farmland was lower (29%) than untreated farmland (34.33%). This

could be the removal of fine particles by soil erosion from untreated land due to the absence of physical barriers. Finer soil particles have been removed by erosion and increasing the proportion of the coarser particles (Terefe et al., 2020)

. Furthermore, Ademe et al. (2017) also confirmed that

there is a higher sand and silt content, but lower content of clay in the untreated farmlands than farmland treated with SWC practices. Moreover, the finding of Hishe et al. (2017) revealed that untreated farmland had the highest sand fractions than treated farmlands. Sand content was higher (35%) and lower (28.56%) in the upper and lower slope classes, respectively (

Table 1). The higher amount of sand content in the upper slope class might be the removal of fine soil particles from steep slopes to the gentle slope class. The result is agreed with Aytenew (2015) and Jembere et al. (2017) who stated that the content of sand increases with an increase in slopes. The lower value of clay (27.33%) was obtained from untreated farmland. However, the higher clay (36.56%) was observed in treated farmland with SFSB followed by SB.

This might be the effects of SWC practices on reducing soil erosion. The result agrees with the finding of Guadie et al. (2020) and Mengistu et al. (2016).

3.1.2. Soil Bulk Density

The BD of soils showed statistically significant variation (p<0.01) between SWC practices and slope (

Table 1). The higher BD of soil (1.36 g cm

−3) was recorded on untreated farmland than treated farmland. This might be the presence of organic matter in treated farmland with SWC practices. Because the higher amount of organic matter decreases the BD of soils. This finding was in line with Challa et al. (2016)

and Guadie et al

. (2020), who showed that the lower BD in treated farmland with SFSB and SB than untreated farmland. Besides, research conducted by Habtamu (2015) reported that an untreated land exhibits higher BD in soils than soil under treated farmland. The lower BD of soil (1.29 g cm

−3) was recorded in lower slope class than middle (1.32 g cm

−3) and upper slope class (1.34 g cm

−3). This could be the removal of organic matter from the upper slope and deposited on the lower slopes. Similar findings by Husen et al. (2017); Gadisa and Hailu (2020), who stated that

the lower BD of soils was recorded in the lower slope than in upper slope.

3.1.3. Total Porosity (TP)

The highest (51.49%) and the lowest (48.81%) TP of soils were observed under the treated lands with SFSB followed by SB than untreated farmland, respectively (

Table 1). This could be that soils on untreated farmland have undergone structural degradation due to removal of soil organic matter. The lower TP of soils on the untreated land was low organic matter content and high BD of soils. The findings of

Guadie et al. (2020) noted that a reverse relationship between BD and TP of soils was done under different environmental conditions. The highest (51.15%) TP of soil was recorded on the lower slope rather than the middle slope (50.36%) and upper slope class (49.27%). This is also due to downward movement of fine particles from upper slope to lower slope positions. The reports of Aytenew (2015) showed that the effects of soil erosion create the variation of BD among slope classes.

3.1.4. Soil pH (H2O)

The ANOVA indicated that the pH of soils was significantly affected by SWC practices and slope class (

Table 2). The soil pH was highest (5.88) on the lower slope of farmland treated with SFSB and lowest (5.68) on the lower slope of land treated with SB followed by untreated land (5.70). Relatively lower soil pH value on untreated land than land treated with SFSB and SB might be associated with loss of basic cations by water erosion. The result agreed with the findings of

Ademe et al. (2017) and Guadie

et al. (2020) who stated that treated farmland has a higher pH value than untreated farmland

. Correspondingly, Teressa (2017) reported that soil pH was higher on treated farmland and lower in untreated farmland. This could be the removal of basic cation and organic matter by water erosion factors from untreated farmland. Therefore, as per the rating of Tadesse et al. (1991), soil pH of both treated and untreated farmland was rated as moderately acidic in the study area.

3.1.5. Soil Organic Matter

The lowest (2.36%) and highest (3.09%) soil organic matter (SOM) content was recorded in untreated and treated farmland with SFSB followed by SB, respectively (

Table 2). The higher SOM could be

accumulation of crop residues and less vulnerability of soil erosion in treated farmland. The lowest SOM might be the loss of decaying leaves and the source of SOM because of lack of physical barriers in the untreated farmland. The result was in line with the findings of Belayneh et al. (2019) who reported that untreated lands had a lower SOM than land treated with SFSB

. Moreover, Challa et al.

(2016) revealed that the lower SOM was observed under untreated land. Regarding to the slope, a higher mean value (3.11%) of SOM was recorded on the lower slope than on the upper and middle slope classes (

Table 2). It could be the transportation of SOM to the lower slope class by erosion. The findings of

Aytenew (2015) and

Chota (2019) stated that the quantity of OM was higher on the lower slope than in the upper slope.

3.1.6. Total Nitrogen (TN)

The mean value of TN content of soils under untreated farmland (0.12%) was significantly lower than treated farmland with SFSB followed by SB (

Table 2). This could be the fast mineralization of existing low SOM content. The result was in line with the findings of

Belayneh et al. (2019);

Ademe et al. (2017) who reported that

the mean value of TN was higher on treated than on untreated farmland

. The result agrees with the findings of Challa et al.

(2016) who found that the TN content under untreated farmland was lower than treated farmland. The highest TN (0.29%) was recorded from the lower slope, while the lowest mean value (0.1%) was recorded from the upper slope. This might be the removal of SOM by soil erosion from the upper slopes, and plant residues and other animal debris are transported and accumulated to the lower slope position. The findings of Lelago et al. (2016) noted

that the lower and higher values of TN were recorded under moderately steep and gentle slopes, respectively. Moreover, the findings of Bekele et al. (2018),

Wubie and Assen (2019) also stated that the highest amount of TN was obtained from gentle slopes.

3.1.7. Available Phosphorus (AP)

The AP

was affected by SWC practices and slope positions (p < 0.05) (

Table 2). The highest AP was observed under treated farmland with SFSB. While the lowest mean value of AP was observed in untreated farmlands (

Table 2). The lower AP results from continuous cultivation and extractive plant harvest to accelerate soil erosion. This finding is in line with

Degu et al. (2019) who found that AP was higher under farmland treated with SFSB and SB than untreated

. Guadie

et al. (2020) and Teressa (2017)

also pointed out AP under treated farmlands was higher than untreated farmlands. The highest AP (6.09 ppm) had been recorded from lower slope and middle slope (5.87 ppm) while the lowest (5.68 ppm) was recorded in the upper slope class. Due to soil erosion, the top soil and organic matter were transported from the upper slope position and accumulated to the lower slope. The result was agreed with the findings of chota (2019), who reported that the lower

AP was recorded in the upper slope rather than the lower and middle slopes. Several research results by Ademe et al. (2017) and Amuyou & Kotingo (2015) noted that higher AP in the lower slope position than on the upper slope.

3.1.8. Exchangeable Bases (Ca+2, Mg+2, Na+ and K+)

Basic cations such as Ca

+2, Mg

+2, K

+ were significantly varied among treated and untreated farmland with slope classes (

Table 3). The highest mean values of Ca

+2, Mg

+2, K

+ were recorded in the treated farmland than untreated farmland. This might be farmland treated with SWC to reduce soil erosion and leaching of basic cations in the study area. The result was agreed with Degu et al. (2019) who showed that higher basic cations were recorded in the treated farmland than on untreated farmland because SWC practices reduce soil erosion and leaching of basic cations. Mengistu et al. (2016) also reported that exchangeable Mg

2+, Ca

2+ and K

+ in the treated farmland with SWC practices were significantly higher than untreated farmland. The lowest and highest exchangeable basic cations (Ca

+2, Mg

+2, K

+ and Na

+) were recorded on the upper and lower slopes, respectively (

Table 3). It could be transport of minerals by erosion from the steep slope areas to the lower slope areas. The result was agreed with the findings of chota (2019) and Degu et al. (2019) revealed that treated farmland showed a higher value of exchangeable basic cations than untreated farmland in the upper and lower slope classes. Ademe et al. (2017) and Kehali et al. (2017) also reported that a higher content of basic cations were recorded on the lower slopes than the middel and the upper slopes.

3.1.9. Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC)

The CEC of soil was affected by SWC practices (treated farmland) and slopes (p<0.01) (

Table 3). The lower CEC (31.59 c

mol (+) kg−1) was obtained on untreated farmland and the higher CEC (38.68 c

mol (+) kg−1) was acquired on treated farmland with SFSB (36.82 c

mol (+) kg−1). The lower CEC on the treated farmland could be induced by erosion and transportation of clay and SOM in the study area. The result was agreed with Degu et al. (2019);

Mengistu et al. (2016) and S

elassie et al. (2015), who stated

that CEC was higher under treated land with SFSB and SB than untreated. The research conducted by Wolka et al. (2016) reported that cultivated lands treated with SB showed higher CEC than untreated farmland. High CEC contents might be the presence of high clay contents and SOM in treated farmland. Besides, SWC is important to increasing soil fertility by reducing nutrient losses. The lower CEC was obtained from the upper slope and the higher value of CEC was obtained from the lower slope class (

Table 3). The lower CEC of soils at the upper slopes could be clay and SOM transported by erosion to the lower slope positions. The study agrees with Rezaei et al. (2015), Kehali et al. (2017) and

Chota (2019) who noted that the accumulation of CEC was higher on the lower slopes than the middle and upper slopes.

3.1.10. Percent of Base Saturation (PBS)

The lower mean value of PBS (48.74%) was obtained from untreated land and the higher mean value of PBS (55.27%) was obtained from treated farmland (

Table 3). It could be low OM and removal of basic cations from untreated farmlands by the action of surface runoff. The PBS was higher on the lower slopes followed by the middle and upper slope classes. It could be the accumulation of clay minerals that were transported from the upper slopes. Similar findings by Aytenew (2015) and

Beshir et al. (2015) stated that the higher PBS was recorded in the lower slope class because of water erosion transport minerals from upper slope to the lower slope.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study showed that physicochemical properties of soils have a significant variation between treated and untreated farmland with slope classes in the study area. The physicochemical properties of soils such as clay, total porosity (TP) pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (AP), exchangeable cation includes Ca2+, Mg2+, K+ and percent base saturation (PBS) were significantly higher on treated farmland with stone-faced soil bund than soil bund followed by untreated farmland. However, bulk density, silt and sand content were higher in the untreated farmland than in treated farmland. The higher values of clay, pH, CEC, SOM, TN, AP and K+ were recorded in the lower slope position than in the middle and upper slope positions. However, the lower content of sand, silt and bulk density was recorded on the lower slopes than in the upper slope class. Thus, farmland treated with stone-faced soil bund (SFSB) play a great role in improving soil fertility than soil bund (SB) followed by untreated farmland in the study area. Therefore, soil and water conservation practices such as stone-faced soil bund (SFSB) should be implemented on farmland to minimize soil erosion and amend soil fertility in the study watershed.

Author Contributions

Mamaru Atinafu, Kassie Getnet, Amare Gojjam: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding

They have no funding to conduct this research.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

Additional Information

No additional information is accessible.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Agriculture Office of Dega Damote district for logistical support during data collection. Moreover, we greatly thank farmers’ willingness to provide farmland for soil sample collection in the study area.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abiye, W. Soil and Water Conservation Nexus Agricultural Productivity in Ethiopia. Adv. Agric. 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademe, Y. , Kebede, T., Mullatu, A. and Shafi, T., 2017. Evaluation of the effectiveness of soil and water conservation practices on improving selected soil properties in Wonago district, Southern Ethiopia. J. Soil Sci. Environ. Manag. 8, 70-79.

- Amdemariam, T. , Selassie, Y.G., Haile, M. and Yamoh, C., 2011. Effect of soil and water conservation measures on selected soil physical and chemical properties and barley (Hordeum spp.) yield. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 5.

- Amuyou, U.A. and Kotingo, K.E., 2015. Toposequence analysis of soil properties of an agricultural field in the Obudu Mountain slopes, cross river state-Nigeria. Eur. J. Phys. Agric. Sci. 3.

- Assaye, A.E. , 2020. Farmers’perception on soil erosion and adoption of soil conservation measures in ethiopia. Int. J. For. Soil Eros. 10.

- Asfaw, D.; Neka, M. Factors affecting adoption of soil and water conservation practices: The case of Wereillu Woreda (District), South Wollo Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2017, 5, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytenew, M. , 2015. Effect of slope gradient on selected soil physicochemical properties of Dawja watershed in Enebse Sar Midir District, Amhara National Regional State. Am. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 6, 74-81.

- Bekele, A.; Aticho, A.; Kissi, E. Assessment of community based watershed management practices: emphasis on technical fitness of physical structures and its effect on soil properties in Lemo district, Southern Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2018, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, K.T.; Van Rompaey, A.; Poesen, J.; Van Bruyssel, S.; Deckers, J.; Amare, K. Spatial Analysis of Land Cover Changes in Eastern Tigray (Ethiopia) from 1965 to 2007: Are There Signs of a Forest Transition? Land Degrad. Dev. 2015, 26, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belayneh, M.; Yirgu, T.; Tsegaye, D. Effects of soil and water conservation practices on soil physicochemical properties in Gumara watershed, Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2019, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshir, S.; Lemeneh, M.; Kissi, E. Soil Fertility Status and Productivity Trends Along a Toposequence: A Case of Gilgel Gibe Catchment in Nadda Assendabo Watershed, Southwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Prot. Policy 2015, 3, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.A. , 1965. Methods of soil analysis, part1. American society of agronomy, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Bohn, H.L.; Mcneal, B.L. and Oconnor, G.A., 2001. Soil Chemistry.3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York. 108 p.

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Hydrometer Method Improved for Making Particle Size Analyses of Soils 1. Agron. J. 1962, 54, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.C. 2008. The nature and properties of soils. Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Prentice Hall. Vol. 13, 662–710.

- Bremner, J.M. and Mulvaney, C.S., 1982. Total Nitrogen, Methods of soil analysis. Part 2. Chemical and microbiological properties, (methodsofsoilan2), 595-624.

- Challa, A. , Abdelkadir, A. and Mengistu, T., 2016. Effects of graded stone bunds on selected soil properties in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Int. J. Nat. Resour. Ecol. Manag. 1, 42-50.

- Chapman, H.D. , 1965. Cation-exchange capacity. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2 Chemical and microbiological properties, 9, 891-901.

- Chota, M.K. , 2019. Effect of slope gradient on selected soil physico chemical property and macronutrient status from coffee farms in gomma district, southwestern ethiopia (doctoral dissertation, jimma university).

- Degu, M.; Melese, A.; Tena, W. Effects of Soil Conservation Practice and Crop Rotation on Selected Soil Physicochemical Properties: The Case of Dembecha District, Northwestern Ethiopia. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Shangguan, Z. HIGH QUALITY DEVELOPMENTAL APPROACH FOR SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION AND ECOLOGICAL PROTECTION ON THE LOESS PLATEAU. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkossa, T.; Williams, T.O.; Laekemariam, F. Integrated soil, water and agronomic management effects on crop productivity and selected soil properties in Western Ethiopia. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2018, 6, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO., 2006. Plant Nutrition for Food Security: A guide for Integrated Nutrient Management. FAO, Fertilizer and Plant Nutrition Bullet in 16, Rome, Italy.

- Gadisa, S.; Hailu, L. Effect of Level Soil Bund and Fayna Juu on Soil Physico-chemical Properties, and Farmers Adoption Towards the Practice at Dale Wabera District, Western Ethiopia. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2020, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadie, M.; Molla, E.; Mekonnen, M.; Cerdà, A. Effects of Soil Bund and Stone-Faced Soil Bund on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Crop Yield Under Rain-Fed Conditions of Northwest Ethiopia. Land 2020, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtamu, H. , 2015. Effect of soil and water conservation on selected soil Characteristics in Dimma watershed, central Ethiopia. Addis Ababa Univ. Ethiop. pp.30-31.

- Hailu, W. , Moges, A. and Yimer, F., 2012. The effects of ‘fanyajuu’soil conservation structure on selected soil physical & chemical properties: the case of Goromti watershed, western Ethiopia. Resour. Environ. 2, 132-140.

- Hazelton, P. and Murphy, B., 2007. Interpreting soil test results. 2nd ed. CSIRO Publisher. 52p.

- Hishe, S.; Lyimo, J.; Bewket, W. Soil and water conservation effects on soil properties in the Middle Silluh Valley, northern Ethiopia. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2017, 5, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurni, H. Degradation and Conservation of the Resources in the Ethiopian Highlands. Mt. Res. Dev. 1988, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurni, H. , Berhe, W.A., Chadhokar, P., Daniel, D., Gete, Z., Grunder, M. and Kassaye, G., 2016. Soil and water conservation in Ethiopia: guidelines for development agents.

- Husen, D. , Esimo, F. and Getechew, F., 2017. Effects of soil bund on soil physical and chemical properties in Arsi Negelle woreda, Central Ethiopia. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 11, 509-516.

- Jembere, A.; Berecha, G.; Tolossa, A.R. Impacts of termites on selected soil physicochemical characteristics in the highlands of Southwest Ethiopia. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2017, 63, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehali, J. , Tekalign, M. and Kibebew, K., 2017. Characteristics of agricultural landscape features and local soil fertility management practices in Northwestern Amhara, Ethiopia. J. Agron. 16, 180-195.

- Lal, R. Soil conservation and ecosystem services. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2014, 2, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelago, A. , Mamo, T., Haile, W. and Shiferaw, H., 2016. Assessment and mapping of status and spatial distribution of soil macronutrients in Kambata Tembaro Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 4, 305-317.

- Mengistu, D.; Bewket, W.; Lal, R. Conservation Effects on Soil Quality and Climate Change Adaptability of Ethiopian Watersheds. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015, 27, 1603–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R. , Cole, C.V., Watanabe, F.S., Dean, L.A. 1954. Estimation of available phosphorous in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate. USDA Circular, 939: 1-19.

- Rowell, D.L. , 1994. Soil Science: Methods and Application, Addison Wesley Longman, Limited England.

- Seifu, W.; Elias, E. Soil Quality Attributes and Their Role in Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2018, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selassie, Y.G.; Anemut, F.; Addisu, S. The effects of land use types, management practices and slope classes on selected soil physico-chemical properties in Zikre watershed, North-Western Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2015, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertsu, S.; Bekele, T. and., 2000. Procedures for soil and plant analysis.

- Shiene, S.D. , 2012. Effectiveness of soil and water conservation measures for land restoration in the Wello area, northern Ethiopian highlands (Doctoral dissertation, Universitäts-und Landesbibliothek Bonn).

- Sinore, T.; Doboch, D. Effects of Soil and Water Conservation at Different Landscape Positions on Soil Properties and Farmers’ Perception in Hobicheka Sub-Watershed, Southern Ethiopia. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T. , Haque, I. and Aduayi, E.A., 1991. Soil, plant, water, fertilizer, animal manure and compost analysis manual. ILCA PSD Working Document.

- Terefe, H.; Argaw, M.; Tamene, L.; Mekonnen, K.; Recha, J.; Solomon, D. Effects of sustainable land management interventions on selected soil properties in Geda watershed, central highlands of Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teressa, D. , 2017. The effectiveness of stone bund to maintain soil physical and chemical properties: The case of Weday watershed, East Hararge zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Civ. Environ. Res. 9, 9-18.

- Tilahun, Z.A. , 2019. Role of Watershed Management for Reducing Soil Erosion in Ethiopia.

- Van Reeuwijk, LP. , 2002. Procedures for soil analysis, 6th edition. ISRIC, Wageningen, the Netherlands. Technical paper 9.

- Wadera, L. , 2013. Characterization and Evaluation of Improved Ston Bunds for Moisture Conservation, Soil Productivity and Crop Yield in Laelay Maychew Woreda of Central Tigray (Doctoral dissertation, M. Sc. Thesis. School of Graduate Studies. Haramaya University, Ethiopia).

- Wolka, K. and Negash, M., 2014. Farmers’ adoption of soil and water conservation technology: a case study of the Bokole and Toni sub-watersheds, southern Ethiopia. J. Sci. Dev. 2, 35-48.

- Wolka, K.; Moges, A.; Yimer, F. Effects of level soil bunds and stone bunds on soil properties and its implications for crop production: the case of Bokole watershed, Dawuro zone, Southern Ethiopia. Agric. Sci. 2011, 02, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolka, K.; Mulder, J.; Biazin, B. Effects of soil and water conservation techniques on crop yield, runoff and soil loss in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 207, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubie, M.A.; Assen, M. Effects of land cover changes and slope gradient on soil quality in the Gumara watershed, Lake Tana basin of North–West Ethiopia. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 6, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).