Running Head: RNA binding protein interactions with modified RNA

The Central Dogma of molecular biology

The discovery of RNA modifications has introduced a new layer of complexity to the ever-changing landscape of biochemistry and molecular biology. Biochemistry and molecular biology involve the study of the structure, function, and interactions between macromolecules essential to life. Molecular biology is based on the interplay between deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), ribonucleic acid (RNA), and protein. These macromolecules are essential for life, with DNA serving as an information storage, RNA as an intermediary dealer of DNA’s information and a jack of all trades, and protein as a versatile, functional building block that makes a cell go. This process, where DNA is made into RNA which is made into protein, is the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology (find the original citation XXX). Despite a number of exceptions to the Central Dogma, concept continues to serve as a fundamental framework for comprehending molecular biology (Ille, Lamont and Mathews 2022). This review focuses on the chemical interactions of RNA with RNA binding proteins, the impacts of RNA modifications on these interactions, and the connection between RNA modifications and the Central Dogma. Understanding how RNAs interact with proteins gives insights into the processes and mechanisms responsible for gene regulation, life, and disease. A greater understanding of RNA biology will lead to new tools to investigate their roles in organisms and new therapies for human and animal diseases.

Overview of RNA and RNA modifications.

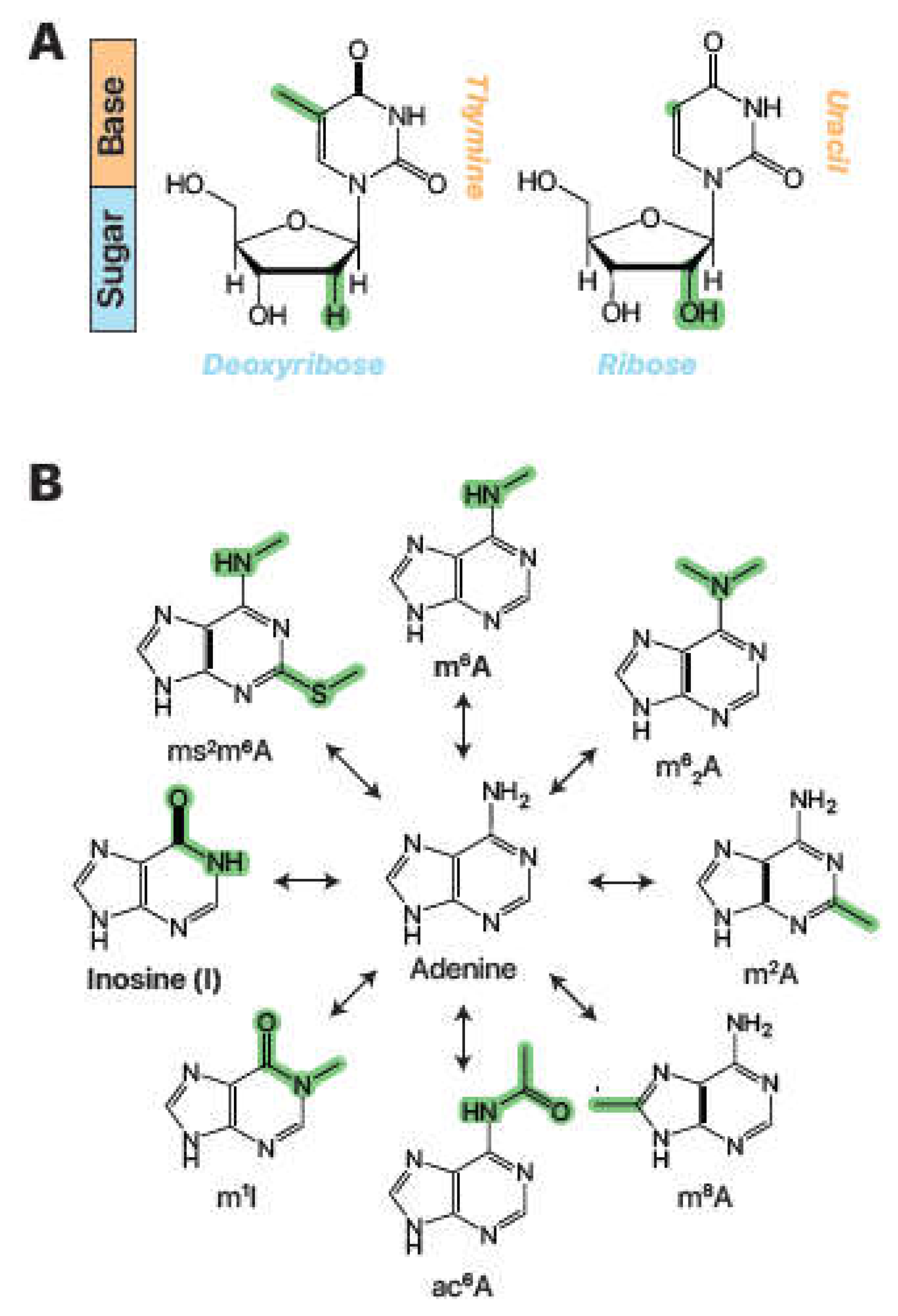

There are three key structural differences between RNA and DNA (

Minchin and Lodge 2019). First, RNA has a hydroxyl group at the 2’ position of its ribose sugar (

Fig 1A). DNA does not, thus defining its “Deoxyribose” name. Second, RNA uses adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and uracil as bases (

Fig 1B). DNA also uses A, C, G, but typically uses thymine (T) instead of U (

Minchin and Lodge 2019), with some notable exceptions (XXX- e.g (

Takahashi and Marmur 1963)). Both DNA and RNA can base pair and go from single stranded nucleic acid to antiparallel double stranded helix (

Fig 1C). DNA and RNA can form other structural assemblies, and they can fold on each other for tertiary structures (

Fig 1C), similar to protein. However, the third difference is that RNA is found in cells as single stranded, double stranded, and tertiary structures. DNA is primarily found as double-stranded helices, stabilizing the nucleic acid, protecting it from degradation to permit long-term transfer of biological information. Thus, DNA and RNA have structural similarities, but their inherent chemical attributes enable them to be used for different purposes in biology.

Figure 1.

DNA, RNA, and RNA modifications. (A) Chemical structures of DNA thymidine and RNA uridine. Chemical differences highlighted in green. (B) Adenine and a selection of natural RNA base modifications. N6-methyladenosine, m6A; N6,N6-dimethyladenosine, m62A; 2-methyladenosine, m2A; 8-methyladenosine, m8A; N6-acetyladenosine, ac6A; 1-methylinosine, m1I; 2-methylthio-N6-methyladenosine, ms2m6A. Chemical differences again highlighted in green.

Figure 1.

DNA, RNA, and RNA modifications. (A) Chemical structures of DNA thymidine and RNA uridine. Chemical differences highlighted in green. (B) Adenine and a selection of natural RNA base modifications. N6-methyladenosine, m6A; N6,N6-dimethyladenosine, m62A; 2-methyladenosine, m2A; 8-methyladenosine, m8A; N6-acetyladenosine, ac6A; 1-methylinosine, m1I; 2-methylthio-N6-methyladenosine, ms2m6A. Chemical differences again highlighted in green.

RNA modifications can occur on all four bases and encompass a diverse array of chemical changes to the nitrogenous base or ribonucleoside sugar. The study of naturally occurring ribonucleoside modifications began in 1951 with the discovery of pseudouridine (Ψ) (

Cohn and Volkin 1951), an isomer of uridine with a carbon-carbon bond attaching the base to the ribose sugar and an added nitrogen (

Fig XXX). Since this discovery, over 140 additional modifications have been identified (

Cantara et al. 2011;

Lorenz, Lünse and Mörl 2017;

Boccaletto et al. 2022). The pace of identifying new modifications is rapidly accelerating due to the enhanced precision and accuracy provided by modern molecular biology equipment and techniques, along with the growing appreciation of RNA modifications and their involvement in a myriad of cellular pathways (

Hong et al. 2020). Other common modification examples include the addition of a hydroxymethyl group on cytidine to form 5-hydroxymethylcytidine (5hmC,

Fig. 2A, XXX) and the methylation of adenosine to form N6-methyladenosine (m

6A,

Fig. 2B, XXX). These chemical changes occur via specialized enzymatic pathways unique to the modification and biological context (

Fu et al. 2013;

Alseth, Dalhus and Bjoras 2014). Therefore, RNA modifications are found at in differing amounts and RNA sites, dependent on the organism, cell type, environment, and other factors.

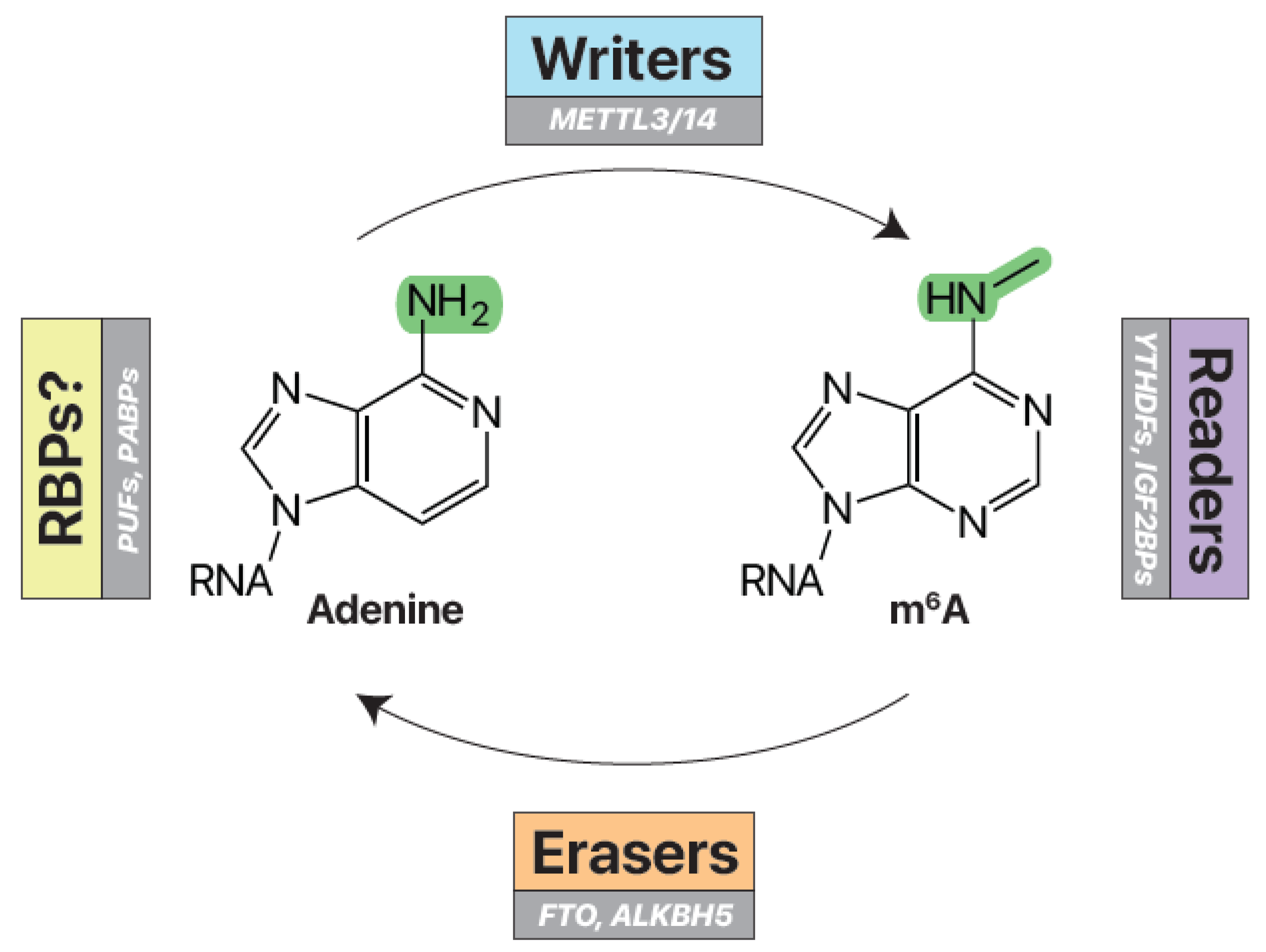

Figure 2.

Writers, erasers, and readers of m6A. Writer enzymes (e.g. METTL3/14) add a methyl group to the nitrogen-6 position of adenosine to make N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA. Eraser enzymes (e.g. FTO, ALKBH5) can remove these methyl marks. Reader RNA-binding proteins (e.g. YTHDFs, IGF2BPs) specifically recognize and bind m6A RNA. Unmodified RNA may be recognized by other RNA-binding proteins (e.g. PUFs, PABPs).

Figure 2.

Writers, erasers, and readers of m6A. Writer enzymes (e.g. METTL3/14) add a methyl group to the nitrogen-6 position of adenosine to make N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA. Eraser enzymes (e.g. FTO, ALKBH5) can remove these methyl marks. Reader RNA-binding proteins (e.g. YTHDFs, IGF2BPs) specifically recognize and bind m6A RNA. Unmodified RNA may be recognized by other RNA-binding proteins (e.g. PUFs, PABPs).

The writers and erasers of m6A

RNA modifications are managed by molecular writers and erasers (Fig. 3A) (Patil, Pickering and Jaffrey 2018; Shi, Wei and He 2019). Writers are enzymes that add a specific RNA modification, while erasers are enzymes that remove the modification. Writers and erasers work together to create and manage the epitranscriptome—the dynamic balance of RNA modifications within the cell. This regulation has far-reaching implications on the molecular function and expression of the modified RNA targets (Lin et al. 2016; Oakes et al. 2017; McCown et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2019).

The m

6A writers and erasers are particularly well-characterized (

Fig. 3) (

Shi, Wei and He 2019;

Jiang et al. 2021) and have a significant impact on gene expression, animal development, and human disease (

Lin et al. 2016;

Yoon et al. 2017;

Choe et al. 2018;

Paris et al. 2019). As such, this review will use m6A as a prototypical example of the chemistry, biochemistry, and biology of an RNA modification and how it interacts with proteins. Discovered in the 1970s (XXX), the modification is prevalent in vertebrate RNA (

Dominissini et al. 2012) and found on thousands of their messenger RNAs (mRNAs), the RNAs used to code for proteins. The mRNAs have modifications concentrated on near stop codons and in their 3’ untranslated regions (

Dominissini et al. 2012;

Patil, Pickering and Jaffrey 2018). The methyltransferase complexes modify adenosine into m

6A. Although consisting of several proteins, the cores of these complexes involved the methyltransferase-like (METTL) enzymes that catalyze the reaction. For example, METTL3 and METTL14 assemble and can modify adenosines in mRNAs, but rely on other proteins for enzymatic activity and site selection (

Liu et al. 2014;

Huang et al. 2021). METTL3 is the enzyme catalytic subunit but relies on METTL14 and other proteins to maintain the correct conformation for enzymatic activity. Complex proteins can also impart preferences for m

6A modification sites (

Bokar et al. 1994). All methyltransferase complexes prefer specific RNA sequences known as motifs (

Fig. 3C). The targeted RNA sequence for METTL3/METTL14 is RRACH motif, where R = A or G, and H = A, C, or U (

Wei and Moss 1977;

Harper et al. 1990). The central A of this motif is enzymatically converted to m

6A. There are two established m

6A erasers: Alkylation B Homolog 5 (ALKBH5) and Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated protein (FTO) (

Zheng et al. 2013;

Zhao et al. 2014). These demethylases work by modifying the N

6 methyl group further to chemistry that can restore the base into unmodified adenosine (

Zhao et al. 2014). Both writers and erasers are associated with human disease. Overexpression of the METTL3/METTL14 m

6A writers are associated with liver, gastric, and colon cancer

(XXX- better to have original citations for particular cancers). The FTO m

6A eraser is associated with obesity (

Fawcett and Barroso 2010). In summary, writers and readers are the enzymatic Ying-Yang for RNA modifications like m

6A. Perturbation of this dynamic balance can lead to disease.

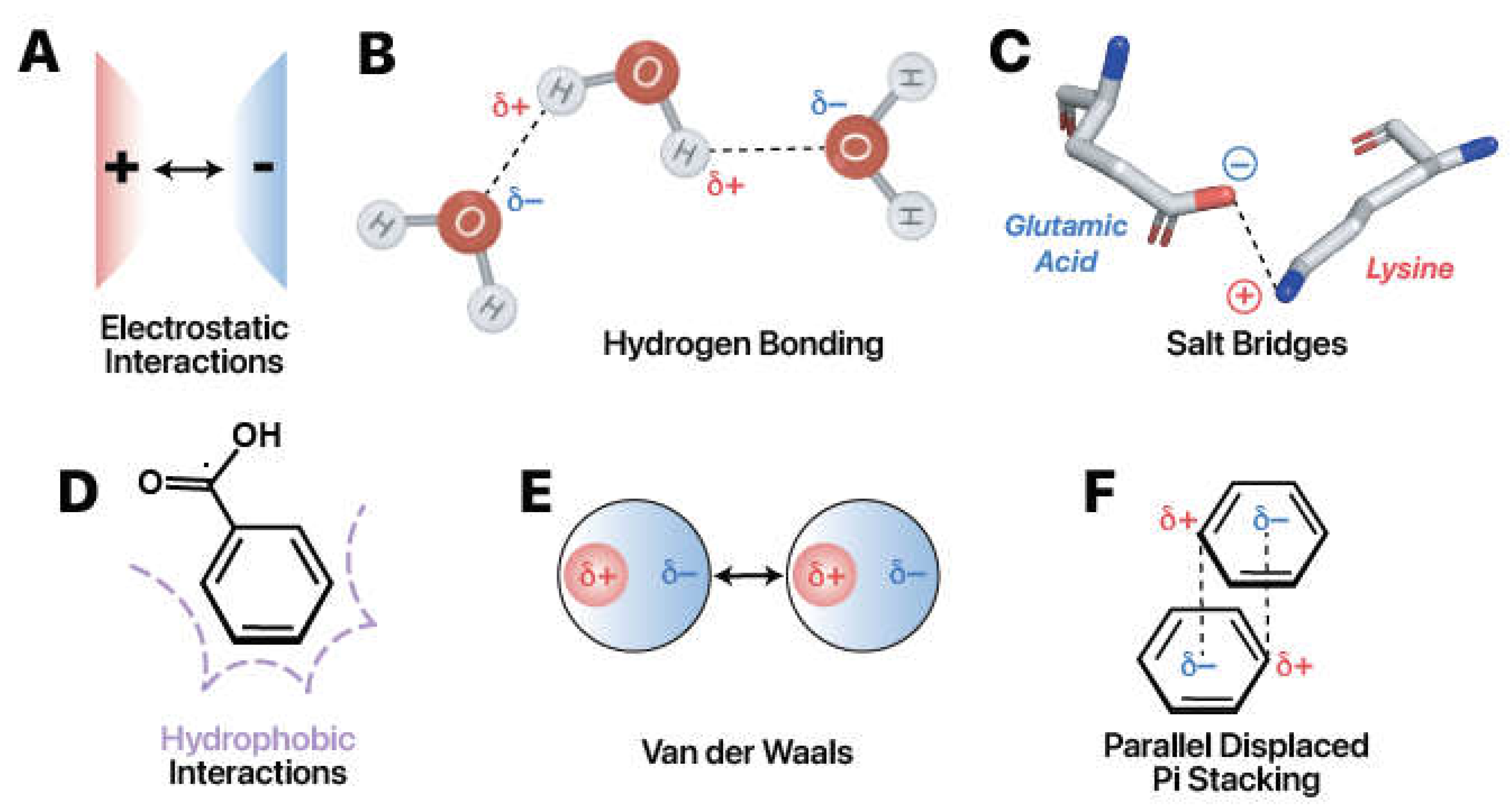

Figure 3.

Six types of intermolecular forces drive RNA-protein interactions. (A) Opposite charges attract. (B) Hydrogen bonds occur commonly among polar molecules such as water. The difference in electronegativity creates opposite partial charges that attract one another. Images adapted from Biorender (Biorender.com). (C) Salt bridges represent the combination of hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions. Example from PDB ID: 5W4A (AOKI et al. 2021). (D) Hydrophobic interactions form in polar solvents. Nonpolar regions aggregate to minimize disruption of favorable solvent-solvent interactions. (E) London dispersion forces, a subtype of Van der Waals interactions, occur due to temporary induced dipoles. (F) Parallel-displaced pi stacking is favorable due to attractions between the positive hydrogen substituents (_+) and the negatively-charged (_-), delocalized pi system.

Figure 3.

Six types of intermolecular forces drive RNA-protein interactions. (A) Opposite charges attract. (B) Hydrogen bonds occur commonly among polar molecules such as water. The difference in electronegativity creates opposite partial charges that attract one another. Images adapted from Biorender (Biorender.com). (C) Salt bridges represent the combination of hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions. Example from PDB ID: 5W4A (AOKI et al. 2021). (D) Hydrophobic interactions form in polar solvents. Nonpolar regions aggregate to minimize disruption of favorable solvent-solvent interactions. (E) London dispersion forces, a subtype of Van der Waals interactions, occur due to temporary induced dipoles. (F) Parallel-displaced pi stacking is favorable due to attractions between the positive hydrogen substituents (_+) and the negatively-charged (_-), delocalized pi system.

The readers of m6A

Readers are binding proteins that recognize specific RNA modifications, an interaction that can lead to regulation of the RNA target. The best characterized readers for m6A are the YTH domain family of proteins (YTHDFs) and YTH domain containing proteins (YTHDCs). YTHDFs and YTHDCs recognize m6A in the nucleus and cytoplasm to resulting in different biochemical functions, contingent on the specific reader protein and the cellular context (Liao, Sun and Xu 2018). For example, YTHDF2 and other YTH proteins can attract mRNA decay machinery through the recruitment the CCR4-NOT deadenylation complex (Du et al. 2016) CCR4-NOT removes the poly-A tail of mRNAs, leading to mRNA turnover. Additional functions of the YTH proteins are still being studied, but a critical aspect is that these proteins must bind to their RNA target to elicit their biochemical function (XXX- He and the first YTH ID). Thus, the molecular recognition of YTH and other RNA binding proteins depend on their interactions with target RNA.

Common RNA-Protein Interactions

To understand how readers recognize specific RNA modifications, it is essential to have a foundation of the chemical interactions between RNA and protein. RNA-protein interactions commonly encompass: 1) electrostatic interactions, 2) hydrogen bonding, 3) salt bridges, 4) hydrophobic interactions, 5) Van der Waals interactions, and 6) pi stacking interactions (Fig. 4) (Corley, Burns and Yeo 2020).

Electrostatic interactions arise from the attraction or repulsion between charged particles (Fig. 4A). The fundamental idea is that opposite charges attract while like charges repel. Protein amino acids have neutral, positive, or negative charges. The propensity of a particular amino acid to carry or lack charge is governed by the chemical structure of its side chain as well as the pH of the surrounding environment (Zhao et al. 2014). While unmodified A, C, G, and U are almost universally neutrally charged within the cell, some RNA modifications carry charge at physiological conditions (Anderson, Droogmans and Grosjean 2005; Lorenz, Lünse and Mörl 2017). Notably, the phosphate group contained in the backbone of nucleic acids carries a negative charge. Consequently, many readers have positively charged residues that nonspecifically attract nucleic acid (Järvelin et al. 2016; Balcerak et al. 2019).

Hydrogen bonding occurs when the partial positive charge of a hydrogen atom, bound to an electronegative atom, attracts an electronegative partner (Fig 4B). Electronegativity denotes an atom's propensity to attract electrons. When highly electronegative atoms, like oxygen or nitrogen, are bound to hydrogen atoms, regions of partial negative charge and partial positive charge are formed, indicated as δ- or δ+, respectively. The partial positive charge occurs on the less electronegative hydrogen, in this case. Conversely, the partial negative charge occurs on the more electronegative group. When correctly oriented, these oppositely charged regions can establish attractions. Neutral hydrogen bonds at 2.4–3.0 Å distance contribute about 0.5–1.5 kcal/mol per interaction, and charged hydrogen bonds, or “salt bridges,'' within a 4.0 Å distance contribute 3.5–4.5 kcal/mol per interaction (Fig 4C) (Herschlag and Pinney 2018). Protein and RNA contains chemical moieties capable of hydrogen bonding, and RNA and protein modifications frequently introduce additional groups that change this capability (Järvelin et al. 2016; Balcerak et al. 2019; Hofweber and Dormann 2019). While generally weaker than covalent or ionic interactions, the lump sum contribution of hydrogen bonds can have considerable impact on the RNA binding protein selectivity for a given modification. Analyses have estimated the prevalence of hydrogen bonds to the base, the ribose 2’-OH, and the RNA phosphate backbone at 36%, 24%, and 41% of RNA-protein hydrogen bonds respectively (Treger and Westhof 2001; Gupta and Gribskov 2011).

Hydrophobic interactions (Fig 4D) occur as a result of molecules trying to minimize contact with the surrounding water. The interactions occur between non-polar regions at distances of 3.8–5.0 Å and contribute approximately 1–2 kcal/mol (Dill et al. 2008; Onofrio et al. 2014). RNA and protein have hydrophilic or hydrophobic moieties which group with like elements (Anderson, Droogmans and Grosjean 2005; Hofweber and Dormann 2019; McCown et al. 2020). Hydrogen bonding will drive hydrophilic interactions. Amino acids with many nonpolar carbon—carbon bonds, like leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and others, are hydrophobic and will fold together to form a “hydrophobic core.” This core may also interact with a hydrophobic moiety on RNA (Allain 1997; Yang 2002; Yu et al. 2014; Zhu et al. 2014a). Up to 50% of RNA-protein interface interactions may be hydrophobic, depending on the RBP (Hu et al. 2018).

There are two types of Van der Waals forces: the weaker London Dispersion Forces and the stronger dipole-dipole forces (Petrucci et al. 1997). London Dispersion Forces arise due to temporary induced dipoles, or imbalances in the charge distribution surrounding molecules (Fig. 4E). Permanent dipoles are hydrogen bonds exceeding a threshold distance of typically 3.0 Å (Allers and Shamoo 2001; Jones et al. 2001). Both Van der Waals forces are weak electrostatic interactions of about 0.5–1 kcal/mol (Corley, Burns and Yeo 2020). They largely play stabilizing roles in the binding of proteins to RNA (Corley, Burns and Yeo 2020).

Aromatic rings aligning face-to-face or face-to-edge results in pi stacking (

Fig. 4F). These interactions typically form at distances of 2.7–4.3 Å and are relatively strong, contributing about 2–6 kcal/mol per interaction (

Wilson, Holland and Wetmore 2016). They are frequently observed in protein and RNA interactions due to the aromaticity present in RNA and many amino acids. In YTH and other RNA Binding Proteins, pi stacking interactions play a crucial role in shaping the active site, effectively sandwiching the targeted base in place (

Oubridge et al. 1994;

Zhu et al. 2014b).

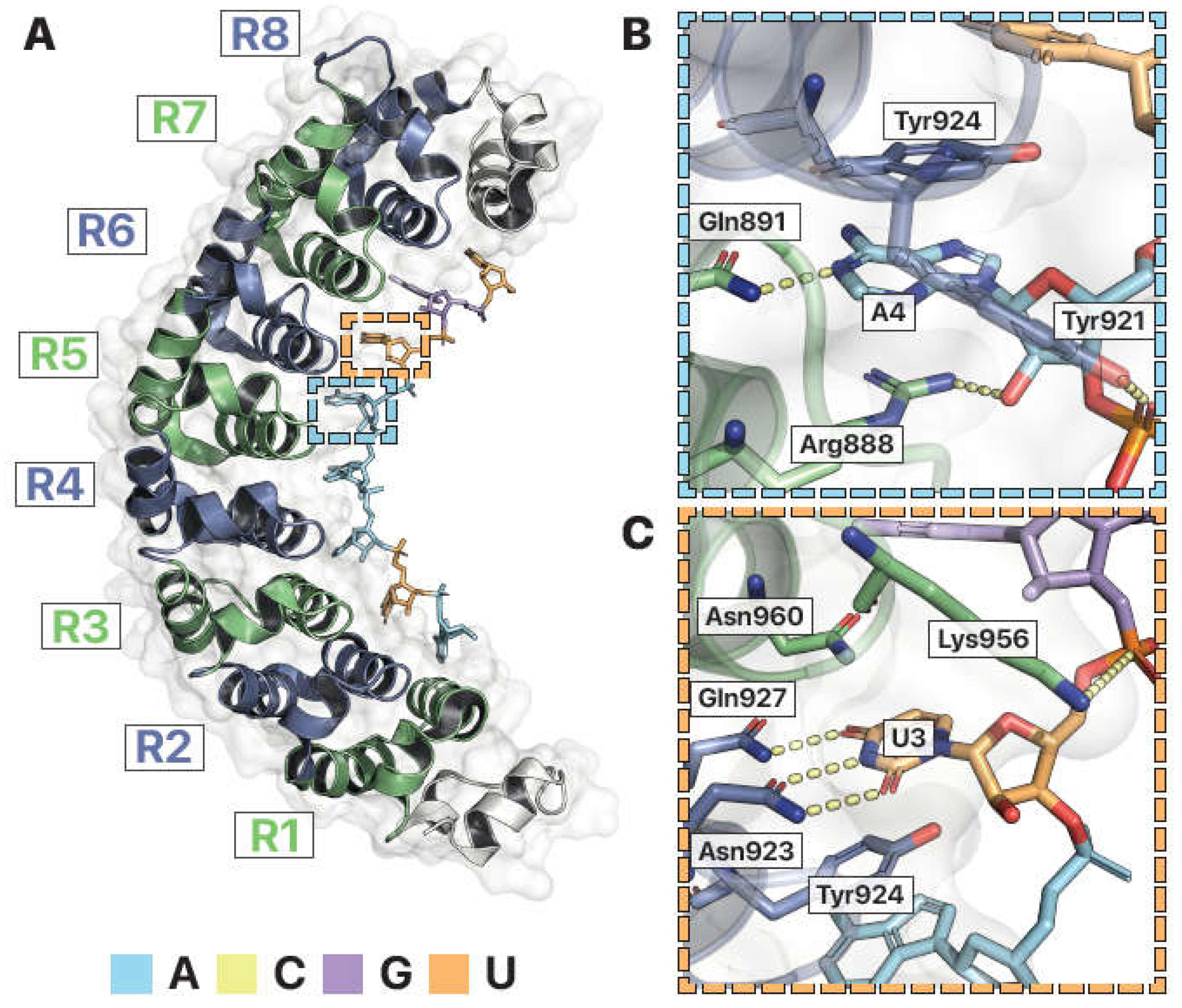

Figure 4.

Structural features of Pumilio, an RNA-binding protein. (A) Crystal structure of human Pumilio 2 homology domain (hPUM2-HD) in complex with RNA (PDB ID: 3Q0Q (LU AND HALL 2011)). The RNA binding domain is composed of 8 α-helical PUF repeats (green and blue), each binding a single RNA base (color coded). Dashed boxes are enlarged in B and C. (B) Coordination of adenosine RNA. Recognition of adenosine at site 4 (“A4”) is mediated by pi stacking with Arginine888 (Arg888) and Tyrosine924 (Tyr924) and hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) with Glutamine891 (Gln891), Arginine888 (Arg888), and Tyrosine921 (Tyr921). (C) Recognition of uridine at site 3 (“U3”) is mediated by pi stacking with Tyrosine924 (Tyr924) and Asparagine960 (Asn960),hydrogen bonds with Glutamine927 (Gln927) and Asparagine923 (Asn923), and electrostatic attractions (dashed lines) between Lysine956 (Lys956) and the RNA phosphate backbone. Images by Pymol (SCHRÖDINGER).

Figure 4.

Structural features of Pumilio, an RNA-binding protein. (A) Crystal structure of human Pumilio 2 homology domain (hPUM2-HD) in complex with RNA (PDB ID: 3Q0Q (LU AND HALL 2011)). The RNA binding domain is composed of 8 α-helical PUF repeats (green and blue), each binding a single RNA base (color coded). Dashed boxes are enlarged in B and C. (B) Coordination of adenosine RNA. Recognition of adenosine at site 4 (“A4”) is mediated by pi stacking with Arginine888 (Arg888) and Tyrosine924 (Tyr924) and hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) with Glutamine891 (Gln891), Arginine888 (Arg888), and Tyrosine921 (Tyr921). (C) Recognition of uridine at site 3 (“U3”) is mediated by pi stacking with Tyrosine924 (Tyr924) and Asparagine960 (Asn960),hydrogen bonds with Glutamine927 (Gln927) and Asparagine923 (Asn923), and electrostatic attractions (dashed lines) between Lysine956 (Lys956) and the RNA phosphate backbone. Images by Pymol (SCHRÖDINGER).

Recognition of RNA by RNA binding proteins

All RNA binding proteins follow similar principles when interacting with their targets. First, they have specificity interactions that designate their sequence or secondary structure preferences. Second, they use positively charged amino acid side chains to account for the negatively charged phosphate backbone. Third, they often specify for the 2’ hydroxyl in RNA to differentiate between DNA.

The Pumilio and FBF protein family (PUFs) of RNA binding proteins serve as a good example of sequence specific RNA interactors that use these three concepts. PUFs contain a conserved RNA-binding domain known as the Pumilio homology domain (PUM-HD) (Quenault, Lithgow and Traven 2011), of which there are many atomic-resolution crystal structures determined without and with RNA (XXX). The human Pumilio 2 homology domain (hPUM2-HD) structure bound to RNA shows how the canonical PUM-HD has eight ɑ-helical repeats that binds to a conserved RNA sequence, UGUANAUA, with N being A, C, G, or U (Gerber et al. 2006; Morris, Mukherjee and Keene 2008; Hafner et al. 2010). Each α-helical repeat recognizes one unpaired base via three amino acid side chains (Campbell, Valley and Wickens 2014). Two side chains interact with an edge of the base, while the third residue forms pi stacking interactions in the plane between two bases (Goldstrohm, Hall and McKenney 2018). Thus, in following with the first principle, amino acid side chains form a tripartite code for sequence binding specificity. PUM-HD also has arginine, lysine, and histidine side chains surrounding the RNA binding surface, following the second principle of positively charged groups attracting negatively charged RNA (new Fig panel?). hPUM2-HD does not have amino acids specifying the 2’ hydroxyl of RNA. Notably, this PUM-HD can bind to both RNA and DNA (XXX). To summarize, the RNA-bound hPUM2-HD structure shows many of the basic characteristics observed in other RNA binding proteins. Deviations to the basic principles, such as the lack of specificity for the 2’ hydroxyl, allows the protein to bind to a broader range of substrates.

Recognition of adenosine at the fourth RNA position is specific and occurs almost entirely through interactions with the nucleobase (

Fig. 6B). The ringed tyrosine and positively charged, flat arginine contributes favorable pi stacking interactions, while glutamine forms a hydrogen bond with the adenosine nitrogen (

Fig 6B). Uridine at the 3rd RNA position has its base similarly sandwiched between amino acid side chains, but specificity is dictated by a different set of protein residues (

Fig. 6C). Uridine and adenosine are very different bases. Uridine is a pyrimidine with a single ring, while adenosine is a purine with two rings. The uracil base of uridine has oxygen moieties attached to its ring. The adenine base of adenosine has nitrogen attached to its ring. PUM-HD uses the oxygen and nitrogen as chemical signatures to differentiate uridine from adenosine. The oxygens on the uracil base form hydrogen bonds with the nitrogens of glutamine and asparagine in PUM-HD. This binding interaction is incompatable with an adenine base. At the remaining six recognition sites, PUM-HD uses specific combinations of amino acids in each α-helical repeat to target specific nucleobases (

Lu and Hall 2011). Thus, RNA binding proteins like PUF target specific RNAs by selecting amino acids that account for the particular chemical signature of their desired targets.

Figure 5.

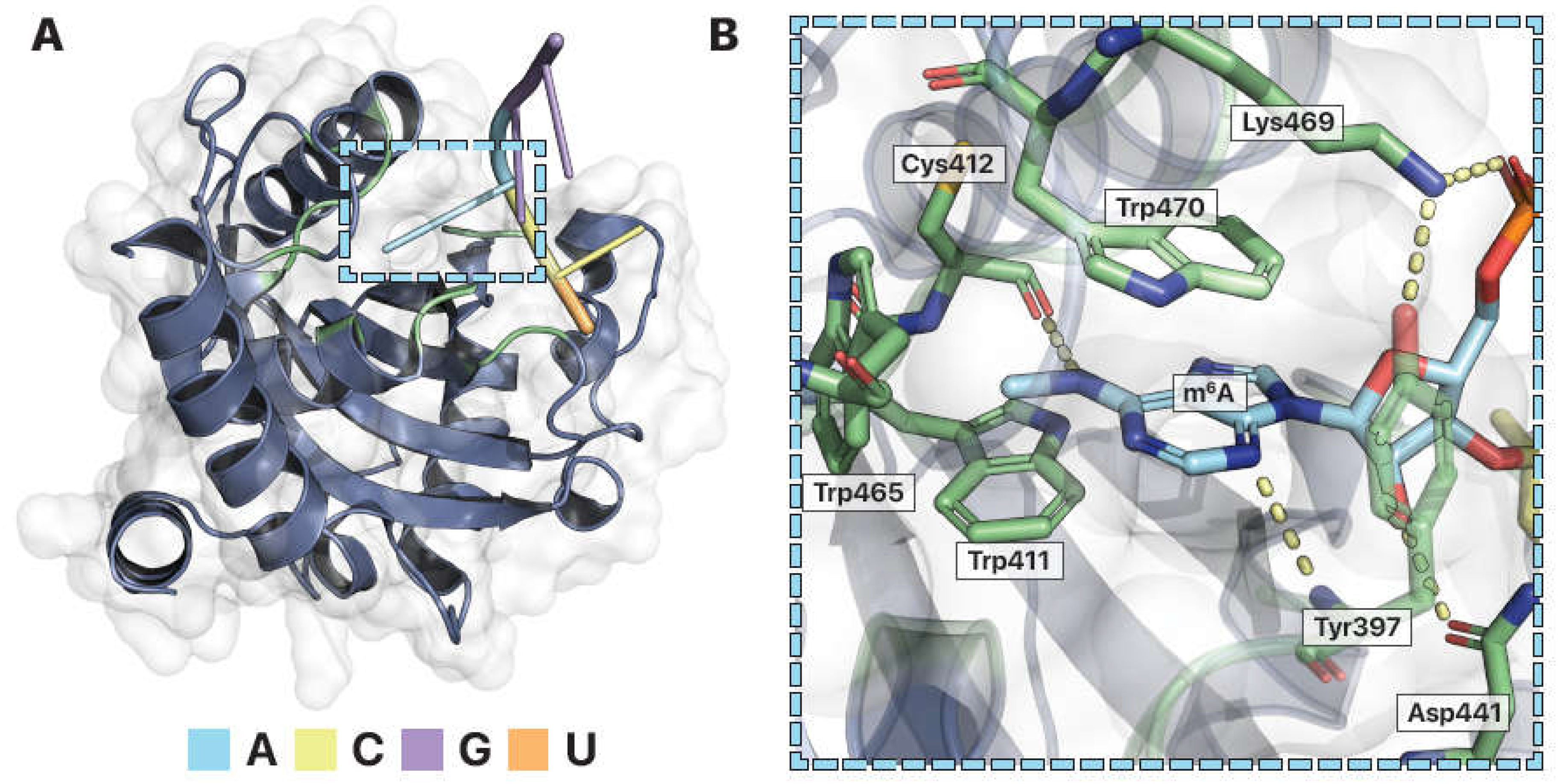

Structural features of YTH, a modified RNA binding protein. (A) Crystal structure of human YTHDF1 in complex with N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA (PDB ID: 4RCJ (Xu et al. 2015)). The modified RNA binding domain has a globular fold that forms a specificity pocket for the m6A modified RNA base. RNA color coded. Dashed box enlarged. (B) The m6A binding pocket. Tryptophan411 (Trp411), Tryptophan465 (Trp465), and Tryptophan470 (Trp470) form a hydrophobic cage that envelopes m6A. Pi stacking with Tryptophan470 and hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) with Cysteine412 (Cys412) and Tyrosine397 (Tyr397) help stabilize the m6A nucleotide within the binding pocket. Salt bridges form between Lysine469 (Lys469) and the RNA phosphate backbone. Images by Pymol (Schrödinger).

Figure 5.

Structural features of YTH, a modified RNA binding protein. (A) Crystal structure of human YTHDF1 in complex with N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA (PDB ID: 4RCJ (Xu et al. 2015)). The modified RNA binding domain has a globular fold that forms a specificity pocket for the m6A modified RNA base. RNA color coded. Dashed box enlarged. (B) The m6A binding pocket. Tryptophan411 (Trp411), Tryptophan465 (Trp465), and Tryptophan470 (Trp470) form a hydrophobic cage that envelopes m6A. Pi stacking with Tryptophan470 and hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) with Cysteine412 (Cys412) and Tyrosine397 (Tyr397) help stabilize the m6A nucleotide within the binding pocket. Salt bridges form between Lysine469 (Lys469) and the RNA phosphate backbone. Images by Pymol (Schrödinger).

Recognition of m6A RNA by RNA binding proteins

RNA binding proteins that can bind modified RNAs like m6A use the same binding strategies as RNA binding proteins that target unmodified RNA. m6A has a methyl group added to its N6 adenosine nitrogen (Fig. 2B). As a result, a nonpolar, bulky methyl group is in place of a hydrogen that can form hydrogen bonds. Similar to PUM-HD forming a specificity pocket that matches the chemistry of a particular RNA base, RNA binding proteins that target modified RNAs chemically accommodate the modification to differentiate between modified and unmodified RNAs. For example, the specificity of the YTH domain for m6A is explained in the atomic resolution crystal structure of YTHDF1 bound with m6A -containing RNA (Fig. 5) (Xu et al. 2015). Like PUM-HD, the YTH domain has ringed amino acids that pi stack with the adenine base of m6A. Positively charged amino acids also form salt bridges with the RNA backbone serve to nonspecifically attract RNA substrates (Fig. 5F). Differences are observed at the YTH specificity pocket for m6A versus the PUM-HD pocket for unmodified adenosine. YTH forms a hydrophobic cage of amino acids surrounding the modification (Fig. 5B). The ring plane of a YTH tryptophan amino acid is perpendicular to the pi stacking amino acids to add a carbon-pi interaction with the methyl moiety of m6A. This interaction also allows the protein to differentiate m6A over an unmodified adenosine with a hydrophilic nitrogen. The YTH binding pocket is absent of any water molecules (Fig. 5C). This is predicted to improve the stability of the hydrophobic interactions and prevent solvent-solvent interactions (XXX cite?). Additionally, YTH hydrogen bonds with the nitrogens of m6A to hold the modified base in place (Fig. 5D). Thus, the specificity pocket of YTH is designed to accommodate a hydrophobic chemical modification to specify the modified adenosine and differentiate from unmodified RNA.

To summarize, the YTHDF1 and hPUM2-HD have similar strategies to target specific RNA substrates. First, both YTHDF1 and hPUM2-HD use amino acid side chains and a medley of chemical interactions to form a specificity pocket designed to accommodate the chemistry of the RNA targeted (Lu and Hall 2011; Xu et al. 2015). YTH hydrophobic interactions predominately assemble the pocket to accommodate the hydrophobic character of the m6A methyl group, while PUM-HD hydrophilic interactions drive its pocket specifity for the unmodified adenosine nitrogen. Second, ringed amino acids pi stack to present the base in a proper position for the binding pocket. And third, positively charged residues on the protein's surface attract the RNA phosphate backbone to nonspecifically enhance its affinity for all RNA substrates. Other RNA binding proteins follow the same principles but can only be appreciated when observing the structural interactions between RNA and protein.

New frontiers in RNA binding proteins

The Central Dogma of Molecular Biology outlines the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein. The pivotal position of RNA, in between the DNA responsible for heredity and the proteins which represent functional products, renders it as a key point of further research in the field of molecular biology. RNA modifications expand the RNA alphabet beyond the four standard ribonucleotides by introducing various alterations to their chemical structure. These RNA modifications are created or removed by enzymes which are characterized either as writers or erasers. These enzymes play a necessary role biology for gene regulation, development, obesity, and cancer (Fawcett and Barroso 2010; Zheng et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2016; Oakes et al. 2017; Yoon et al. 2017; Choe et al. 2018; Zhou and Pang 2018; McCown et al. 2019; Paris et al. 2019; Chen and Wong 2020; Huang et al. 2022). RNA binding protein readers have evolved to selectively bind distinct unmodified and modified RNA. While differing the structure and sequence, these binding proteins use a conserved set of principles to recognize target RNA. The differences and similarities of RNA binding proteins is on full display in atomic resolution RNA-protein structural models.

The study of RNA modifications is in a renaissance and undergoing exponential growth. Only a handful of modifications have been characterized, in part because of the lack of methods to identify their RNA targets and sites. Some methods use chemistry (e.g. XXX) or RNA binding proteins (e.g. XXX) to identify the sites, but these methods must be specifically tailored to each RNA modification. Universal methods to identify multiple types of RNA modifications are challenging but also in the infant stages of development (e.g. XXX). Determining the modification sites provides a starting point toward understanding how they affect RNA stability, folding, and function. Thus, the development of new, accurate methods for uncharacterized RNA modifications will be key to investigate the link between modifications, biology, and disease (Carlile et al. 2014; Delatte et al. 2016; Garalde et al. 2018; Khoddami et al. 2019; Acera Mateos et al. 2023). As discussed in this review, one key mechanism of m6A is the recruitment of RNA binding proteins through novel chemical interactions for RNA regulation. A safe prediction is that other RNA modifications will also recruit or prevent interactions with RNA binding proteins as their biological mechanism. Similar to YTH, PUM-HD, and others, these RNA binding proteins will undoubtedly follow similar strategies to recognize subtle chemical differences of modified RNA to deliver a profound impact on RNA form and function.

Funding

S.T.A. is funded by the NIH/NIGMS (R35 GM142691) and received start-up funds from the Indiana University School of Medicine and its Precision Health Initiative (PHI).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acera Mateos, P., Y. Zhou, K. Zarnack and E. Eyras, 2023 Concepts and methods for transcriptome-wide prediction of chemical messenger RNA modifications with machine learning. Brief Bioinform 24. [CrossRef]

- Allain, F. H. T., 1997 Structural basis of the RNA-binding specificity of human U1A protein. The EMBO Journal 16: 5764-5772. [CrossRef]

- Allers, J., and Y. Shamoo, 2001 Structure-based analysis of protein-RNA interactions using the program ENTANGLE. J Mol Biol 311: 75-86. [CrossRef]

- Alseth, I., B. Dalhus and M. Bjoras, 2014 Inosine in DNA and RNA. Curr Opin Genet Dev 26: 116-123. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. T., L. Droogmans and H. Grosjean, 2005 Fine-tuning of RNA functions by modification and editing. Grosjean, H., editor 12: 121-139. [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S. T., T. R. Lynch, S. L. Crittenden, C. A. Bingman, M. Wickens and J. Kimble, 2021 C. elegans germ granules require both assembly and localized regulators for mRNA repression. Nat Commun 12: 996. [CrossRef]

- Balcerak, A., A. Trebinska-Stryjewska, R. Konopinski, M. Wakula and E. A. Grzybowska, 2019 RNA–protein interactions: disorder, moonlighting and junk contribute to eukaryotic complexity. Open Biology 9: 190096. [CrossRef]

- Boccaletto, P., F. Stefaniak, A. Ray, A. Cappannini, S. Mukherjee et al., 2022 MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2021 update. Nucleic Acids Res 50: D231-D235. [CrossRef]

- Bokar, J. A., M. E. Rath-Shambaugh, R. Ludwiczak, P. Narayan and F. Rottman, 1994 Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei. Internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J Biol Chem 269: 17697-17704. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Z. T., C. T. Valley and M. Wickens, 2014 A protein-RNA specificity code enables targeted activation of an endogenous human transcript. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 21: 732-738. [CrossRef]

- Cantara, W. A., P. F. Crain, J. Rozenski, J. A. McCloskey, K. A. Harris et al., 2011 The RNA Modification Database, RNAMDB: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D195-201. [CrossRef]

- Carlile, T. M., M. F. Rojas-Duran, B. Zinshteyn, H. Shin, K. M. Bartoli and W. V. Gilbert, 2014 Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515: 143-146. [CrossRef]

- Cerneckis, J., Q. Cui, C. He, C. Yi and Y. Shi, 2022 Decoding pseudouridine: an emerging target for therapeutic development. Trends Pharmacol Sci 43: 522-535. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., and C.-M. Wong, 2020 The emerging roles of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) deregulation in liver carcinogenesis. Molecular Cancer 19. [CrossRef]

- Choe, J., S. Lin, W. Zhang, Q. Liu, L. Wang et al., 2018 mRNA circularization by METTL3–eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature 561: 556-560. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, W. E., and E. Volkin, 1951 Nucleoside-5′-Phosphates from Ribonucleic Acid. Nature 167: 483-484. [CrossRef]

- Corley, M., M. C. Burns and G. W. Yeo, 2020 How RNA-Binding Proteins Interact with RNA: Molecules and Mechanisms. Molecular Cell 78: 9-29. [CrossRef]

- Delatte, B., F. Wang, L. V. Ngoc, E. Collignon, E. Bonvin et al., 2016 Transcriptome-wide distribution and function of RNA hydroxymethylcytosine. Science 351: 282-285. [CrossRef]

- Dill, K. A., S. B. Ozkan, M. S. Shell and T. R. Weikl, 2008 The Protein Folding Problem. Annual Review of Biophysics 37: 289-316. [CrossRef]

- Dominissini, D., S. Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S. Schwartz, M. Salmon-Divon, L. Ungar et al., 2012 Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485: 201-206. [CrossRef]

- Du, H., Y. Zhao, J. He, Y. Zhang, H. Xi et al., 2016 YTHDF2 destabilizes m6A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4–NOT deadenylase complex. Nature Communications 7: 12626. [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, K. A., and I. Barroso, 2010 The genetics of obesity: FTO leads the way. Trends Genet 26: 266-274. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., G. Jia, X. Pang, R. N. Wang, X. Wang et al., 2013 FTO-mediated formation of N6-hydroxymethyladenosine and N6-formyladenosine in mammalian RNA. Nat Commun 4: 1798. [CrossRef]

- Garalde, D. R., E. A. Snell, D. Jachimowicz, B. Sipos, J. H. Lloyd et al., 2018 Highly parallel direct RNA sequencing on an array of nanopores. Nature Methods 15: 201-206. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A. P., S. Luschnig, M. A. Krasnow, P. O. Brown and D. Herschlag, 2006 Genome-wide identification of mRNAs associated with the translational regulator PUMILIO in <i>Drosophila melanogaster</i>. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103: 4487-4492. [CrossRef]

- Goldstrohm, A. C., T. M. T. Hall and K. M. McKenney, 2018 Post-transcriptional Regulatory Functions of Mammalian Pumilio Proteins. Trends in Genetics 34: 972-990. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., and M. Gribskov, 2011 The role of RNA sequence and structure in RNA--protein interactions. J Mol Biol 409: 574-587. [CrossRef]

- Hafner, M., M. Landthaler, L. Burger, M. Khorshid, J. Hausser et al., 2010 Transcriptome-wide Identification of RNA-Binding Protein and MicroRNA Target Sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141: 129-141. [CrossRef]

- Harper, J. E., S. M. Miceli, R. J. Roberts and J. L. Manley, 1990 Sequence specificity of the human mRNA N6-adenosine methylase<i>in vitro</i>. Nucleic Acids Research 18: 5735-5741. [CrossRef]

- Herschlag, D., and M. M. Pinney, 2018 Hydrogen Bonds: Simple after All? Biochemistry 57: 3338-3352. [CrossRef]

- Hofweber, M., and D. Dormann, 2019 Friend or foe-Post-translational modifications as regulators of phase separation and RNP granule dynamics. J Biol Chem 294: 7137-7150. [CrossRef]

- Hong, M., S. Tao, L. Zhang, L. T. Diao, X. Huang et al., 2020 RNA sequencing: new technologies and applications in cancer research. J Hematol Oncol 13: 166. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., L. Qin, M. Li, X. Pu and Y. Guo, 2018 A structural dissection of protein–RNA interactions based on different RNA base areas of interfaces. RSC Advances 8: 10582-10592. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., J. Mo, Z. Liao, X. Chen and B. Zhang, 2022 The RNA m6A writer WTAP in diseases: structure, roles, and mechanisms. Cell Death & Disease 13. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., T.-Q. Chen, K. Fang, Z.-C. Zeng, H. Ye and Y.-Q. Chen, 2021 N6-methyladenosine methyltransferases: functions, regulation, and clinical potential. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 14. [CrossRef]

- Ille, A. M., H. Lamont and M. B. Mathews, 2022 The Central Dogma revisited: Insights from protein synthesis, CRISPR, and beyond. WIREs RNA 13. [CrossRef]

- Järvelin, A. I., M. Noerenberg, I. Davis and A. Castello, 2016 The new (dis)order in RNA regulation. Cell Communication and Signaling 14. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., B. Liu, Z. Nie, L. Duan, Q. Xiong et al., 2021 The role of m6A modification in the biological functions and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6: 74. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S., D. T. Daley, N. M. Luscombe, H. M. Berman and J. M. Thornton, 2001 Protein-RNA interactions: a structural analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 943-954. [CrossRef]

- Khoddami, V., A. Yerra, T. L. Mosbruger, A. M. Fleming, C. J. Burrows and B. R. Cairns, 2019 Transcriptome-wide profiling of multiple RNA modifications simultaneously at single-base resolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116: 6784-6789. [CrossRef]

- Liao, S., H. Sun and C. Xu, 2018 YTH Domain: A Family of N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) Readers. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 16: 99-107. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S., J. Choe, P. Du, R. Triboulet and I. R. Gregory, 2016 The m 6 A Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes Translation in Human Cancer Cells. Molecular Cell 62: 335-345. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Y. Yue, D. Han, X. Wang, Y. Fu et al., 2014 A METTL3–METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nature Chemical Biology 10: 93-95. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, C., C. Lünse and M. Mörl, 2017 tRNA Modifications: Impact on Structure and Thermal Adaptation. Biomolecules 7: 35. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G., and T. M. T. Hall, 2011 Alternate Modes of Cognate RNA Recognition by Human PUMILIO Proteins. Structure 19: 361-367. [CrossRef]

- McCown, P. J., A. Ruszkowska, C. N. Kunkler, K. Breger, J. P. Hulewicz et al., 2020 Naturally occurring modified ribonucleosides. WIREs RNA 11: e1595. [CrossRef]

- McCown, P. J., M. C. Wang, L. Jaeger and J. A. Brown, 2019 Secondary Structural Model of Human MALAT1 Reveals Multiple Structure–Function Relationships. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20: 5610. [CrossRef]

- Minchin, S., and J. Lodge, 2019 Understanding biochemistry: structure and function of nucleic acids. Essays Biochem 63: 433-456. [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. R., N. Mukherjee and J. D. Keene, 2008 Ribonomic Analysis of Human Pum1 Reveals <i>cis-trans</i> Conservation across Species despite Evolution of Diverse mRNA Target Sets. Molecular and Cellular Biology 28: 4093-4103. [CrossRef]

- Oakes, E., A. Anderson, A. Cohen-Gadol and H. A. Hundley, 2017 Adenosine Deaminase That Acts on RNA 3 (ADAR3) Binding to Glutamate Receptor Subunit B Pre-mRNA Inhibits RNA Editing in Glioblastoma. Journal of Biological Chemistry 292: 4326-4335. [CrossRef]

- Onofrio, A., G. Parisi, G. Punzi, S. Todisco, M. A. Di Noia et al., 2014 Distance-dependent hydrophobic–hydrophobic contacts in protein folding simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16: 18907-18917. [CrossRef]

- Oubridge, C., N. Ito, P. R. Evans, C. H. Teo and K. Nagai, 1994 Crystal structure at 1.92 Å resolution of the RNA-binding domain of the U1A spliceosomal protein complexed with an RNA hairpin. Nature 372: 432-438. [CrossRef]

- Paris, J., M. Morgan, J. Campos, G. J. Spencer, A. Shmakova et al., 2019 Targeting the RNA m6A Reader YTHDF2 Selectively Compromises Cancer Stem Cells in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell Stem Cell 25: 137-148.e136. [CrossRef]

- Patil, D. P., B. F. Pickering and S. R. Jaffrey, 2018 Reading m(6)A in the Transcriptome: m(6)A-Binding Proteins. Trends Cell Biol 28: 113-127. [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, R. H., F. G. Herring, J. D. Madura and C. Bissonnette, 1997 General Chemistry: Principles and Modern Applications, 11e.

- Quenault, T., T. Lithgow and A. Traven, 2011 PUF proteins: repression, activation and mRNA localization. Trends in Cell Biology 21: 104-112. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, L., The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System,, pp.

- Shi, H., J. Wei and C. He, 2019 Where, When, and How: Context-Dependent Functions of RNA Methylation Writers, Readers, and Erasers. Molecular Cell 74: 640-650. [CrossRef]

- Slotkin, W., and K. Nishikura, 2013 Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing and human disease. Genome Medicine 5: 105. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, I., and J. Marmur, 1963 Replacement of thymidylic acid by deoxyuridylic acid in the deoxyribonucleic acid of a transducing phage for Bacillus subtilis. Nature 197: 794-795. [CrossRef]

- Treger, M. L., and E. Westhof, 2001 Statistical analysis of atomic contacts at RNA-protein interfaces. Journal of Molecular Recognition 14: 199-214. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-M., and B. Moss, 1977 Nucleotide sequences at the N<sup>6</sup>-methyladenosine sites of HeLa cell messenger ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 16: 1672-1676. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. A., D. J. Holland and S. D. Wetmore, 2016 Topology of RNA–protein nucleobase–amino acid π–π interactions and comparison to analogous DNA–protein π–π contacts. RNA 22: 696-708. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., K. Liu, H. Ahmed, P. Loppnau, M. Schapira and J. Min, 2015 Structural Basis for the Discriminative Recognition of N6-Methyladenosine RNA by the Human YT521-B Homology Domain Family of Proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry 290: 24902-24913. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., 2002 Solution structure of the LicT-RNA antitermination complex: CAT clamping RAT. The EMBO Journal 21: 1987-1997. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.-J., F. R. Ringeling, C. Vissers, F. Jacob, M. Pokrass et al., 2017 Temporal Control of Mammalian Cortical Neurogenesis by m6A Methylation. Cell 171: 877-889.e817. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q., W. Ye, C. Jiang, R. Luo and H.-F. Chen, 2014 Specific Recognition Mechanism between RNA and the KH3 Domain of Nova-2 Protein. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 118: 12426-12434. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Y. Yang, B.-F. Sun, Y. Shi, X. Yang et al., 2014 FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Research 24: 1403-1419. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Q. Zhao, P. J. Kaboli, J. Shen, M. Li et al., 2019 m1A Regulated Genes Modulate PI3K/AKT/mTOR and ErbB Pathways in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Transl Oncol 12: 1323-1333. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G., A. J. Dahl, Y. Niu, P. Fedorcsak, C.-M. Huang et al., 2013 ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Molecular Cell 49: 18-29. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-X., and X. Pang, 2018 Electrostatic Interactions in Protein Structure, Folding, Binding, and Condensation. Chemical Reviews 118: 1691-1741. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T., I. A. Roundtree, P. Wang, X. Wang, L. Wang et al., 2014a Crystal structure of the YTH domain of YTHDF2 reveals mechanism for recognition of N6-methyladenosine. Cell Research 24: 1493-1496. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T., I. A. Roundtree, P. Wang, X. Wang, L. Wang et al., 2014b Crystal structure of the YTH domain of YTHDF2 reveals mechanism for recognition of N6-methyladenosine. Cell Res 24: 1493-1496. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).