1. Introduction

Colors are one of the first parameters, if not the first, captured and evaluated by human sight right after seeing any object, i.e., food, flowers and plants, clothes, animals, and other human beings. Due to this, the most varied industries invest in research and development to create new colors and sources and then conceive new market trends leading to innovation [

1,

2].

Synthetic pigments have participated significantly in the pigment industry for decades despite their negative impact on the environment and people's health. Although they dominate the market, microbial pigments, produced as secondary metabolites, are an alternative environment-friendly and non-toxic to synthetic pigments. In this context, microbial pigments possess excellent nutritional and therapeutic properties, and the industry is progressively recognizing these properties through the findings published in the literature. For instance, microalgae pigments reached significant commercialization in the food and supplements industry [

3]. The use of other microbial pigments is under constant development, and the pharmaceutical and textile are also commercializing these pigments with a broad possibility of expansion for the cosmetic sector and paint, among others [

4]. Besides this, the advances in organic chemistry and metabolic engineering linked to synthetic biology and omics sciences enabled the production on a large scale [

5].

2. Pigments and Dyes

Pigments or dyes are chemical substance that selectively absorbs light and reflects it at a 400-800 nm wavelength, resulting in a specific color visible to the naked eye. Physiologically, these resulting colors integrate first human perceptions, part of a primary system in visual information processing. This process occurs in the photoreceptors and ganglion cells of the human retina, which differentiate such colors in several micro divisions from different shades, nuances, clarities, and saturations. Humans attribute to colors not only everyday perceptions but also a representation of feelings, emotions, organization, and categorization of objects, memories, and construction of personal styles, among others [

6,

7]. The functions performed by pigments in living organisms range from beautification as a sensory attractant for pollination to internal functions such as protection against oxidative stress caused by ultraviolet (UV) radiation. These bioactive properties arouse the interest of industries once they are natural compounds with numerous benefits to human health, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties and, sometimes, being associated with the control and avoidance of some chronic diseases, such as types of cancers and cardiovascular problems [

8,

9]. Differences occur between dyes and pigments, although they have similar applications in providing colors to objects. Dyes are water-soluble compounds with a molecular level of dispersion that confers them brighter and more vivid colors but low stability to the light. Meanwhile, pigments are hardly soluble in water by nature, reaching a level of dispersion in particles; they are not affected by the vehicle of incorporation, maintaining the same absorption and mirroring of light [

10,

11].

2.1. Synthetic and Natural Pigments

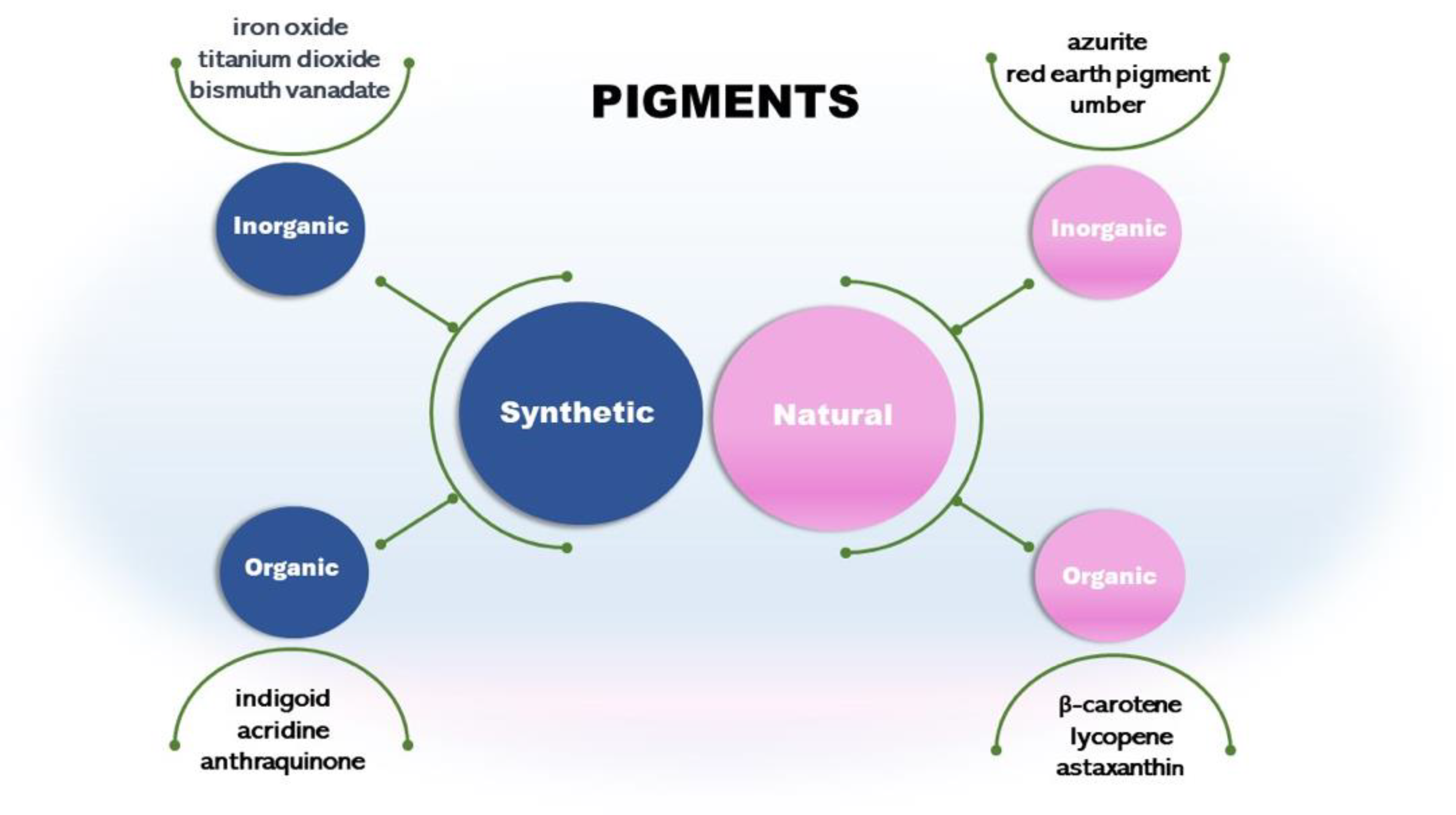

Pigments can be synthetic or natural (

Figure 1). Synthetic pigments are artificially created. They present various colors and are commonly used in industries, including paints, coatings, plastics, and ceramics. Some examples are cadmium red, iron oxide yellow, black, and bismuth vanadate. Some synthetic inorganic pigments like titanium dioxide and chromium oxide are mineral-based. These pigments are known for their stability and durability [

10,

11]. This pigment type presents a stable and well-known synthesis process and low-cost production, an economic advantage. With low or no biodegradability, they are contributing to the planet's unsustainable production chains. In addition, there are reports of cases associated with consuming synthetic pigments with carcinogenic properties and allergic reactions [

12,

13].

Other classes are synthetic organic pigments, which form a large group of differentiated compounds due to their chemical and physical properties, such as chromogen structure and solubility. We can cite the chromogens indigoid, acridine, and anthraquinones [

14]. Synthetic organic pigments are underestimated as environmental contaminants; currently, they are considered micropollutants due to their low concentration (ng/l to µg/l) in aquatic ecosystems [

14].

Kant reported that the textile industry is very pollutant, n

ot all but synthetic organic and inorganic pigments' toxic nature has become a problem for all life forms [

15]

. The presence of sulfur, naphthol, chromium compounds, heavy metals (copper, arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury, nickel, and cobalt), and other chemicals make the textile effluent highly toxic. Other harmful chemicals in the water may be formaldehyde-based pigment-fixing agents, chlorinated stain removers, hydrocarbon-based softeners, and non-biodegradable dyeing chemicals. These organic materials react with many disinfectants, especially chlorine, and form often carcinogenic by-products. The same heavy metal contamination was detected after the use of synthetic pigments in the textile industry in Indonesia [

16]

.

These industrial pollutants were hazardous and carcinogenic for consumers as well. It was not until recently that the synthetic pigments' effects started to surface, and industries were forced to look in a new direction [

4]. Eco-friendly products have been valued by the market and the public, who prefer more natural-based options, preferably with philosophies aligned with the planet's sustainability. This factor even warns traditional brands to support innovation values, bringing sustainable development to attract and retain more consumers [

12].

Another type is the natural inorganic pigments such as umber from clay minerals. It has been used in art and as a coloring agent for centuries. Other pigments are azurite and red earth pigment [

17]. Pigments from minerals are inorganic and usually extracted from rocks, soils, and ores [

18,

19]. However, as cited in this review, some synthetic inorganic are mineral-based and chemically synthesized. For example, iron oxide can be classified as natural inorganic if extracted from rocks or synthetic if chemically synthesized [

20].

Natural pigments from mineral sources may contain heavy metal contamination, which could be a problem used for industrial purposes. Because of this, numerous regulations worldwide aim to control the presence of lead, arsenic, and other heavy metals brought directly from pigments in some products, such as cosmetics [

12,

21]. The use of mineral pigments promotes ecological risks. In the case of irrigation water, it contaminates agriculture and food for human consumption. If not adequately routed, waste and disposal of this production process can enter a trophic chain and bioaccumulate in fish and aquatic bodies [

22].

In the dyes and pigments industry, around 15% of its world production is estimated to be wasted along the production chain up to the application, representing around 128 tons per day of environmental impact

. Precisely inorganic pigments, a large part of pigments, become environmental pollutants since they are poorly biodegradable and bioaccumulated [

23,

24]. Even at low concentrations, dyes and pigments discarded in rivers and seawater modify the tone of the water, reducing light penetration in the aqueous phase and thus negatively impacting a whole chain of marine life that depends on photosynthetic organisms. The problem becomes evident when additives from the textile industries are considered, using light-stable dyes but not biodegradable. In addition, heavy metals can still be discarded, even in underreported amounts, reaching aquatic life and soil and then incorporated into agriculture and cultivated foods, becoming part of the food chain.

Furthermore, what is debatable is that part of the pigments destination is for the cosmetic industry, which should prioritize the use of products that use renewable sources of substrates with a firm policy regarding pollutant disposal during production [

23,

25,

26,

27]. Natural organic pigments are growing more expressively as a source of natural pigments. They will be the focus of the next section.

3. Natural Pigments

Natural organic pigments from plants, insects, and microorganisms have many structures, such as carotenoids, like β-carotene, lycopene, and astaxanthin [

4,

28]. Plant-based pigments are rapidly denatured in the presence of a change in pH, harming reproducibility [

29]. In addition, plant pigments require large monoculture areas, pest control, and rainfall reliance, among other circumstantial parameters that affect the quality and the percentage of crop loss [

2,

30,

31,

32]. Therefore, this possibility, as much as it is natural, organic, and biodegradable, still causes some degree of impact on the environment due to the need for large irrigation volumes of water and, sometimes, the use of pesticides to help in pest control [

12,

22].

There are also pigments extracted from animals, mainly from insects and mollusks, widely used in ancient times. However, their use has declined over the years due to the difficulty of production and animal exploitation [

33]. Insects are a source of several pigments, such as

anthraquinones, aphids, pterins, tetrapyrroles, ommochromes, melanins, and papiliochromes [

34]. However, obtaining these pigments requires costly insect cultivation and purification [

28]. In addition, allergic problems have been reported [

35].

Table 1 compares the advantages and disadvantages of three primary pigment sources.

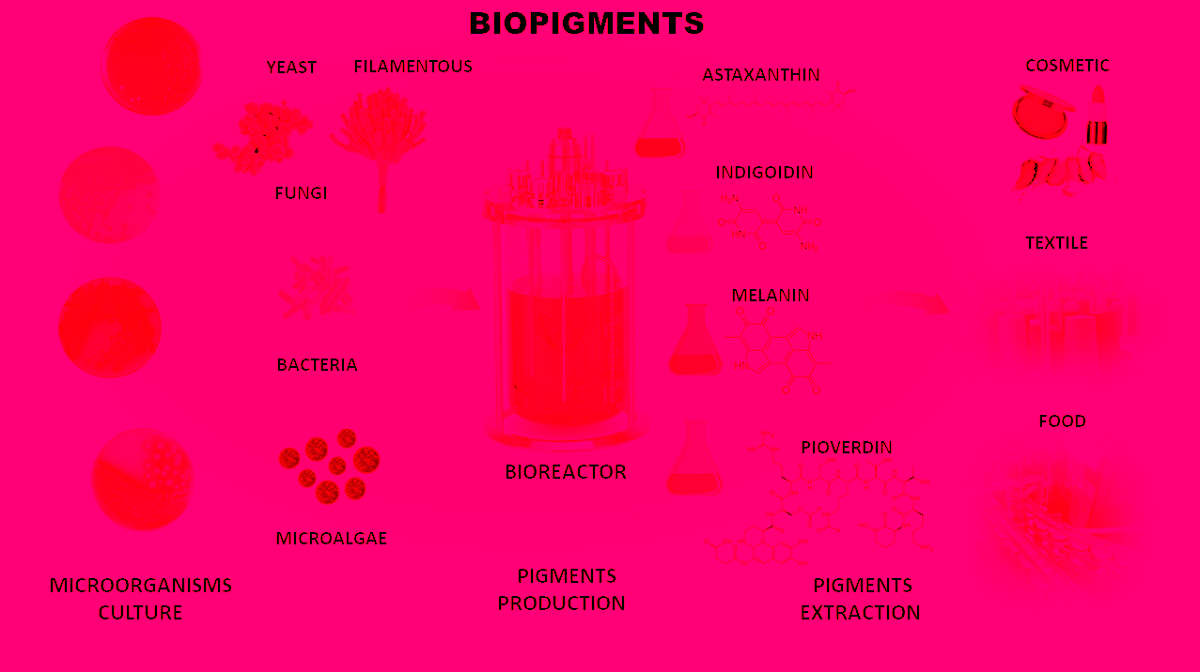

4. Microbial Pigments Advantages

An increasing search for sustainable and non-pollutant bioproducts is a reality in the current planet scenario. Microorganisms can be an excellent source of bioproducts with applications in various industrial sectors. One of these possibilities lies in producing microbial pigments. The use of microorganisms presents numerous advantages. They can grow in bioreactors under physical- chemical-controlled conditions and use industrial residues and by-products as carbon and nitrogen sources for fermentation, reducing production costs [

39]. In addition, this procedure lowers the industrial rejects, which will be biotransformed by microbial metabolism [

40,

41]. The production does not compete for arable land and is not influenced by climate change [

42]. Through synthetic biology, they can be modified genetically for optimization for production, including expressing genes in model microorganisms such as

E.coli [

1,

4,

43,

44,

45,

46].

Bacteria, fungi, and microalgae produce microbial pigments. They constitute a broad field with potential biotechnological applications for coloring in the food, cosmetic, textile, and pharmaceutical industries. Many microorganisms produce pigments of various chemical classes, such as carotenoids, anthocyanins, and prodigiosin [

47,

48,

49]. Microbial pigments are an essential alternative to traditional pigments and dyes used in industries. They bring countless benefits and reinforce the industrial commitment to the environment.

The use of microbial pigments still faces resistance, mainly due to production costs, despite being an innovative alternative, opening a new panorama of sustainable products that bring gains to the environment and human and animal health. Optimizing fermentation processes makes the bioprocess more profitable. They can come from modifications in the controlled cultivation process, but they can also be more punctual and specific. With research and investments in biotechnology, genetic modifications of microorganisms are feasible to increase pigment production or affect other parallel characteristics that also help manufacture colors [

42,

50]. It is necessary to consider that the world's bioprocess demand has been increasing in the last five years. The

Bioreactors market was valued at $2,615.4 million in 2020 and is estimated to reach $7,328.4 million by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 10.7% from 2021 to 2030. Development in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry and advancement in R&D for cell culture and microbial application are the major factors that drive the growth of the global bioreactors market [

51]

. In this context, improvements in bioprocesses for microbial pigments are in progress and are estimated to reduce costs.

5. Pigment Absorption

Visible light is a part of the electromagnetic spectrum whose wavelengths can interact with the visual system and be identified as colors. It comprehends the range of 740 (red) to 380 (violet) nm. The color of a pigment is observed when it absorbs visible light at a particular wavelength and reflects the remaining wavelengths. The observed color is the one complementary to the color absorbed. For instance, when a substance absorbs in the red wavelength range (625 - 740 nm), it gives its complementary color (green) and vice-versa [

52].

The absorption of electromagnetic energy in the UV or visible range by a chemical compound leads to specific transitions of electrons between orbitals. The required amount of energy must correspond to the energy gap between the orbitals for these transitions. The most probable transition is between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). When the gap between HOMO and LUMO is high, the molecule will absorb short-wavelength UV radiation; however, when this difference is reduced, the energy gap can be within the frequency of the visible spectrum [

52,

53]. In organic compounds, the structural feature that confers the ability to absorb visible light is the existence of various conjugated double bonds, which lowers the energy gap between HOMO and LUMO. The portion of the molecule that bears this characteristic and is responsible for light absorption is known as a chromophore [

52,

53]. In this section, the main chemical classes of pigments produced by microorganisms will be presented.

6. Properties of Microbial Pigments

Bacteria, fungi, archaea, and microalgae produce several primary and secondary metabolites that allow the microorganism to survive and adapt to its environment. Among these molecules and substances are the pigments, which in general have not only protective functions against external agents, such as ultraviolet radiation and reactive oxygen species, but also antibacterial and fungicidal actions to ensure the territoriality of the environment and its nutrients, preventing the installation of other microbial species at the site. Some pigments can also assist in photosynthetic functions in energy production in the cell [

54,

55,

56].

Table 2 summarizes examples of bacteria, microalgae, and fungi pigments. The names of microorganisms, their producers, and their functions are described.

Molelekoa

et al. [

73] characterized different microbial pigments extracted from fungi, such as bostrycoidin (a red aza-anthraquinone), with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties produced by

Fusarium solani. Another red one called rubropunctamine extracted from

Talaromyces verruculosus with antioxidant and antimicrobial biological activities described too; and sclerotin (yellow-brown) with antioxidant, antibiofilm and antimicrobial properties produced by

Penicillium multicolour and

P. mallochi. Some microorganisms can grow under different physicochemical conditions due to metabolites like carotenoids. In another work, the authors suggested that staphyloxanthin, a golden carotenoid biopigment extracted from Staphylococcus aureus, is an important virulence factor due to its antioxidant properties [

74].

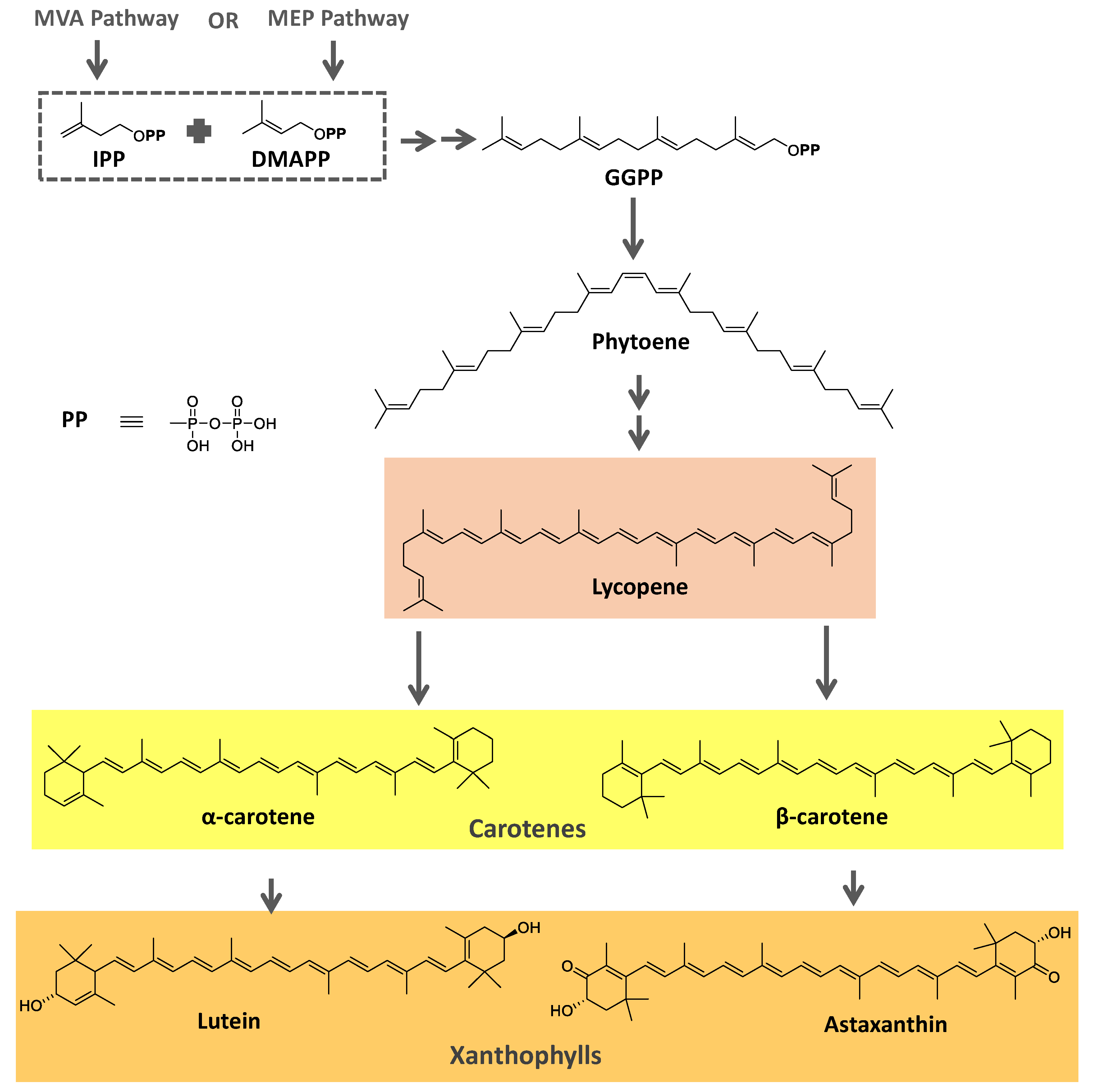

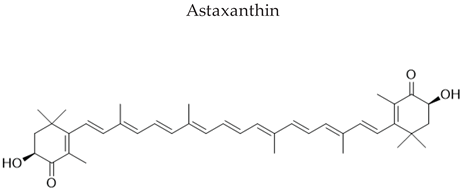

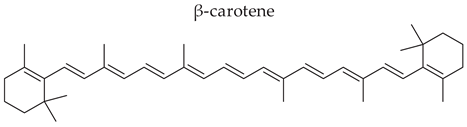

6.1. Carotenoids

Carotenoids, a group of isoprenoid-derived substances, represent nature's most widely distributed pigments, with yellow, orange, red, and purple colors. They are biosynthesized by archaea, eubacteria, algae, fungi, and plants [

75,

76,

77]. Bright colors in some animals, such as crustaceans, birds, and insects, can be due to carotenoids; however, those are obtained through diet or symbiotic/pathogenic microorganisms [

7,

76].

Most carotenoids are derived from the precursor phytoene (C

40). However, some species of bacteria can produce C

50 and C

30 carotenoids from different precursors [

7]. Their general structure comprises a polyene chain with nine or more conjugated double bonds and an end group on both sides [

7,

77]. These chains absorb light between 450–570 nm, corresponding to chlorophyll's absorption gap. Thus, carotenoids can be accessory pigments in photosynthesis [

7]. Carotenoid structures are classified into two broad groups: carotenes, non-oxygenated substances, and xanthophylls, corresponding to oxygenated molecules [

76,

77,

78]. Examples of both groups are shown in

Figure 2.

The biosynthetic pathway for carotenoids starts with condensing two geranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) molecules catalyzed by the enzyme phytoene synthase to produce phytoene. This precursor undergoes a series of desaturations and isomerization to form lycopene, a red-colored pigment, which can be later cyclized under the action of cyclases to form molecules such as α-, β-, and γ-carotenes. Hydroxylases, ketolases, or other enzymes may be oxygenated by Carotene molecules to originate xanthophylls [

78,

79]. GGPP can be derived from C

5 precursors (dimethylallyl diphosphate and isopentenyl diphosphate) from the mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway or the 2-

C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway depending on the organism. Archaea, fungi, and most bacteria utilize the MVA pathway, while photosynthetic organisms apply the MEP pathway [

78,

79].

Figure 2 summarizes the biosynthetic pathway for carotenoids.

Many microorganisms produce carotenoids, mainly due to the stressful environmental conditions in which they live. However, not all of them are of industrial relevance [

80]. Among the carotenoid-producing microorganisms, bacteria offer several advantages based on short life cycles, metabolic flexibility, and simple propagation techniques. In addition, they can be genetically manipulated [

81]. Torularhodin and torulene are widespread microbial carotenoid pigments produced by several genera of microorganisms in high concentrations [

82,

83]. Zoz

et al. [

84] described that these pigments had pro-vitamin A activity and potential application as coloring additives in foods and cosmetics, like the lycopene carotenoid pigment, due to their red color.

Table 3 shows different carotenoids cited in the literature, their sources, and their structural formulas.

Yoo

et al. [

88] reported the production of a red pigment with potential antioxidant and antibacterial activities extracted from the yeast

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa AY-01. Furthermore, in a recent study, Mussagy

et al. [

83] provided crucial information for regulatory approval of carotenoid pigment and subsequent commercialization. The authors concluded that microbial torularhodin reduces the risks associated with synthetic dyes, offering greater efficacy and safety for humans, inferring that this xanthophyll can and should be explored in various commercial applications.

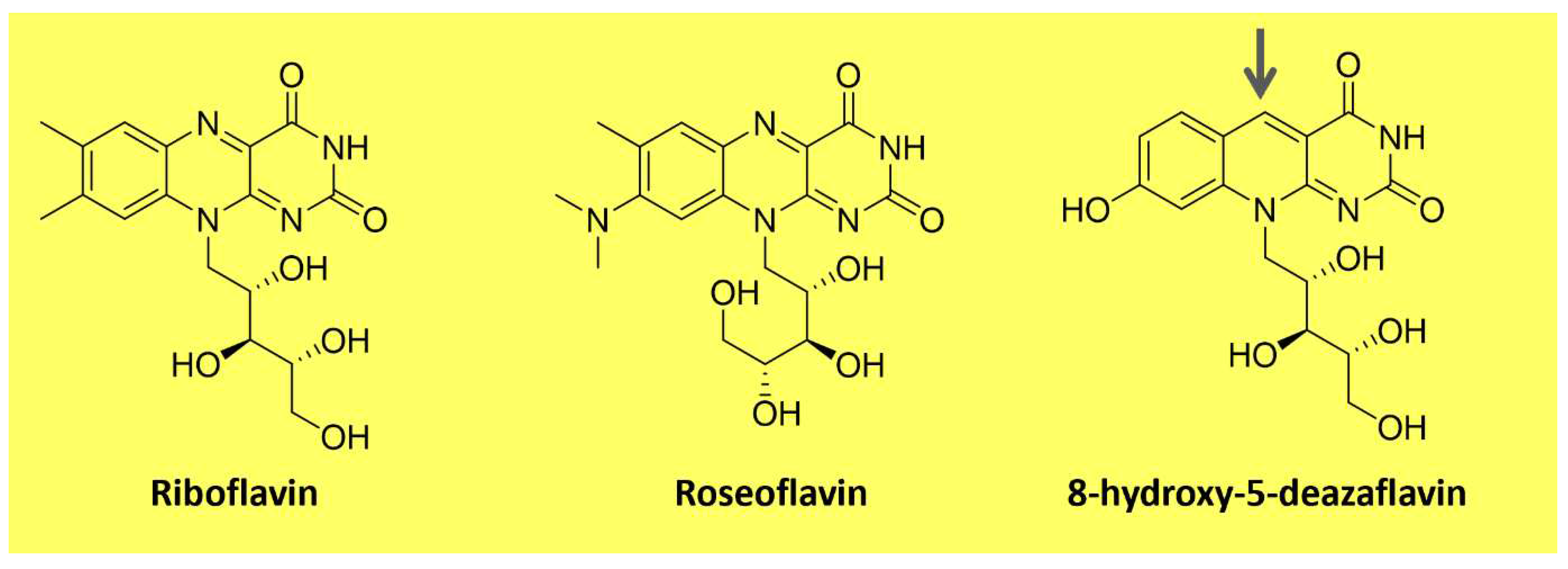

6.2. Flavins

Flavins are pteridine-based yellow substances bearing an

N-heterocyclic isoalloxazine ring (

Figure 3). They are produced by plants and most microorganisms [

89,

90]. Riboflavin (vitamin B2) is a water-soluble compound that exhibits pigment properties. It is the source of all biologically relevant flavins. It originates from flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), essential moieties for the activity of flavoproteins and flavo-coenzymes, which play many physiological roles, such as protein folding and metabolism of fatty acids and amino acids [

90]. Animals and a few microorganisms do not produce riboflavin and need to obtain it through nutrition as a vitamin [

89]. Apart from riboflavin, examples of natural flavins include roseoflavin an antimicrobial pigment (

Figure 3); a riboflavin analog produced by

Streptomyces bacteria, and 5-deazaflavins, flavin derivatives found in Archaea (e.g., 7,8-Dimethyl-8-hydroxy-5deazaflavin -

Figure 3), in which the nitrogen in the five positions of the isoalloxazine ring is replaced by a carbon [

89].

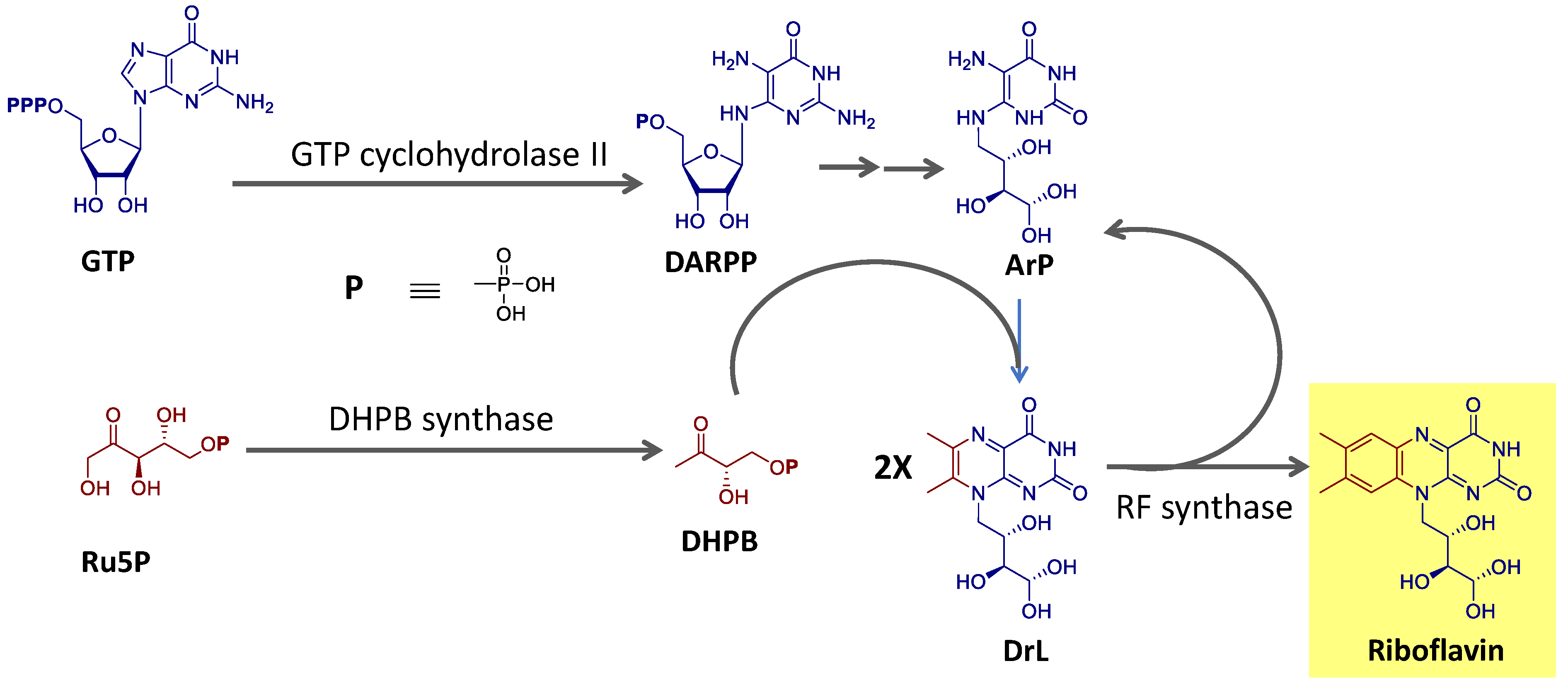

Riboflavin is biosynthesized using the purine guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and ribulose-5-phosphate (Ru5P) from the pentose phosphate pathway as precursors [

90,

91]. GTP provides the pyrimidine portion and the other two nitrogen atoms of the isoalloxazine ring and the ribityl side chain. Ru5P originates the remaining carbon atoms of the heterocyclic ring. The final reaction step, catalyzed by the enzyme riboflavin synthase, consists of a dismutation reaction in which two molecules of the intermediate 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine (DrL) exchange four carbon atoms [

90,

91]. This process is summarized in

Figure 4.

Deazaflavins, on the other hand, have diaminouracil and tyrosine as precursors, and its biosynthetic pathway was demonstrated to involve the participation of 5′-deoxyadenosyl radicals to form the typical heterocyclic ring [

92].

6.3. Tetrapyrrole Derivatives

Tetrapyrrole compounds, composed of four pyrrole rings connected by methine bridges, are ubiquitous. They constitute the heme group, which is part of hemoglobin, cytochromes, and other proteins, and are part of chlorophyll and billin pigments [

93,

94,

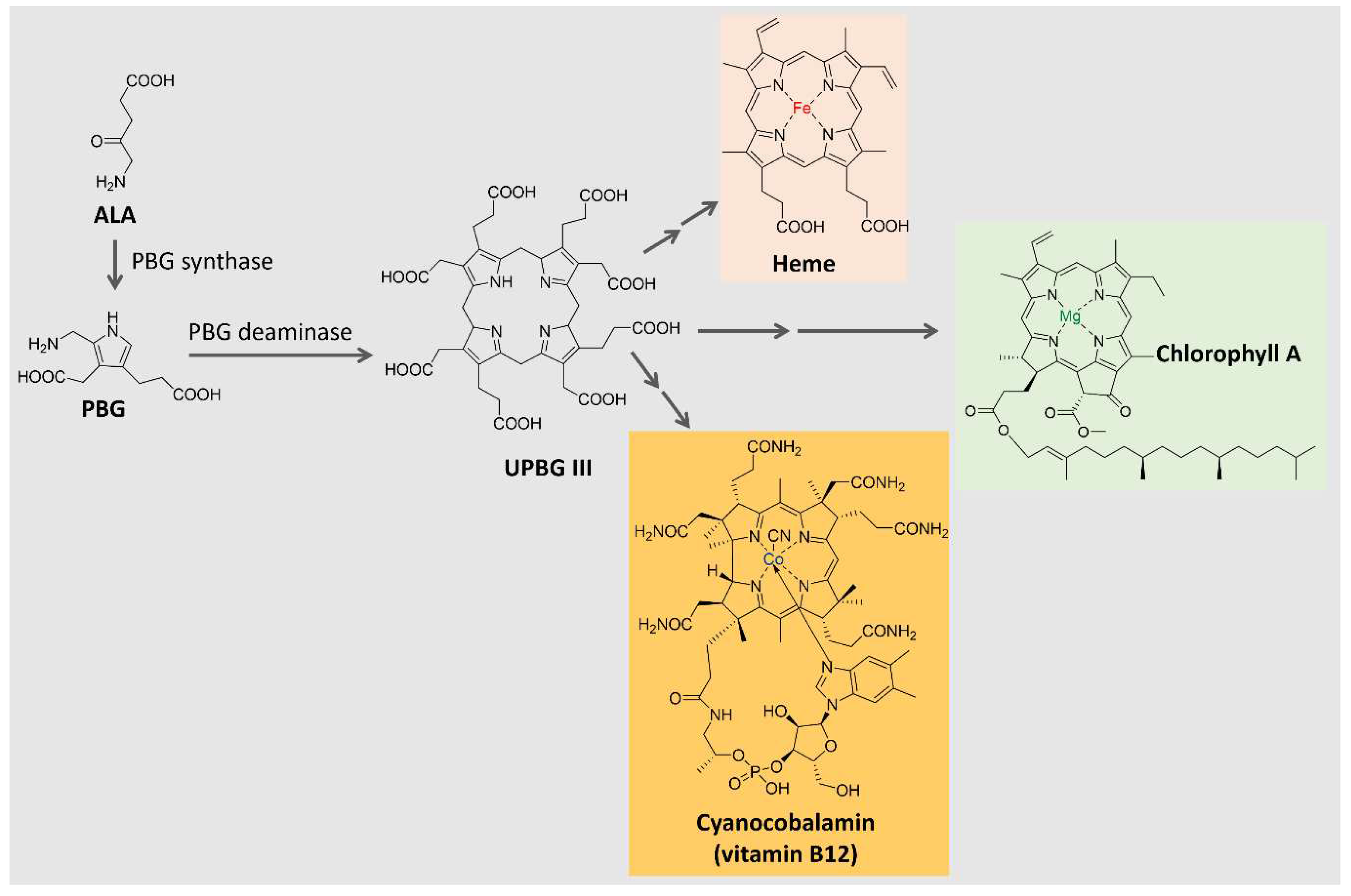

95]. Tetrapyrrole is biosynthesized from δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), a 5-carbon amino acid formed by the condensation of glycine and succinyl coenzyme A in animals, fungi, and some bacteria (C4 pathway) or from α-ketoglutarate in plants, algae, archaea, and most bacteria (C5 pathway) [

95,

96]. The condensation of two ALA molecules catalyzed by porphobilinogen synthase originates porphobilinogen (PBG), with a pyrrole ring in its structure. Porphobilinogen deaminase catalyzes the condensation of four molecules of porphobilinogen, forming a tetrapyrrole ring (uroporphyrinogen III) [

93,

95], which is further modified and complexed with metal ions to originate compounds such as the heme group, chlorophyll, coenzyme B12 and many others, as shown in

Figure 5. In the present section, two groups of tetrapyrrole pigments will be further discussed: the chlorophylls and the phycobiliproteins.

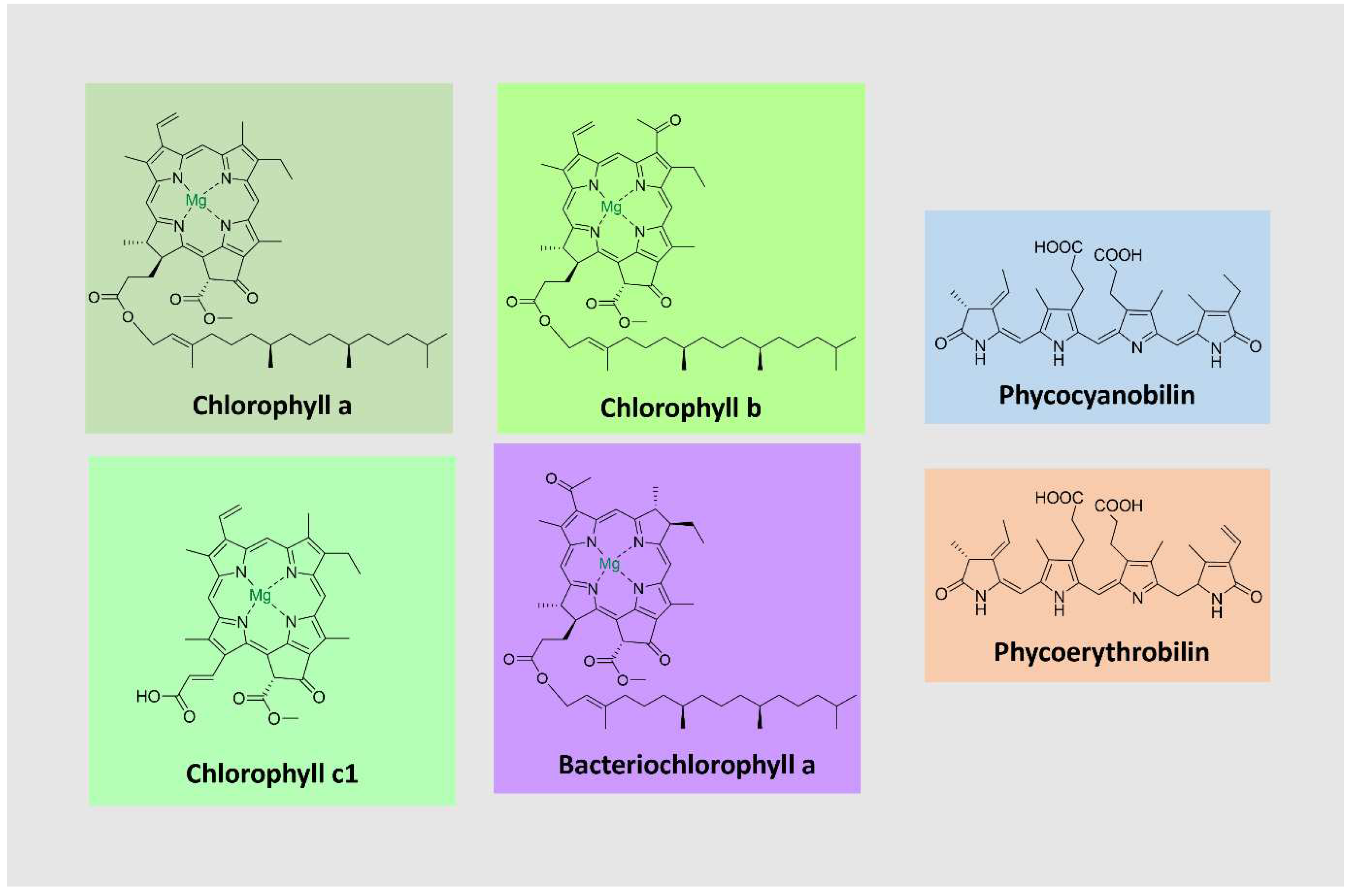

Chlorophylls, the most abundant pigments on earth, are essential for photosynthesis, absorbing light and transducing it into chemical energy [

97,

98]. They consist of tetrapyrrolic macrocyclic molecules complexed with magnesium. Most are esterified to a long-chain alcohol in C-17 [

99]. These pigments absorb light in the violet-blue (400-500 nm) and the yellow-orange/red (600-700 nm) parts of the visible spectrum. Chlorophylls occur together with carotenoids and proteins as light-harvesting complexes in plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. The most common ones are chlorophylls a-d [

98]. They differ in the degree of unsaturation of the pyrrolic macrocycle in the side chains, which influences their light absorption properties (

Figure 6).

Bacteriochlorophylls are found in anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria and are related to chlorophylls [

100]. They can have shifted absorption bands compared to chlorophyll (under 400 and beyond 700 nm), extending the usable light spectrum. A noteworthy example is bacteriochlorophyll a, the most widely distributed pigment in photosynthetic bacteria, with a purple color [

99,

100] (

Figure 6).

Phycobiliproteins (PBPs) are brilliantly colored, water-soluble proteins covalently linked to open-chain tetrapyrrole chromophores known as phycobilins. PBPs are part of light-harvesting complexes in cyanobacteria, red algae, and other algae groups. They are arranged in subcellular structures denominated phycobilisomes, which absorb sunlight from 470 – 660 nm and transfer the energy to chlorophyll a [

101,

102]. PBPs are classified into three major groups according to spectral properties: phycoerythrin (red), phycocyanin (blue), and allophycocyanin (bluish-green) [

102,

103,

104]. Due to essential absorption characteristics, PBPs have emerged as promising fluorescent labeling agents, suitable for applications in fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, fluorescence immunoassay, and various other biomedical studies. Red microalgae such as

Rhodella spp.,

Bangia spp., and

Porphyridium spp produce red PBPs [

104].

PBRs comprise hetero subunits α and β and are commonly found as trimers or hexamers. Each monomer contains two to five phycobilin units bound to cysteine residues [

101,

102]. Phycobillins are formed from the macrocyclic tetrapyrrole heme by cleavage of a carbon bridge and releasing the iron atom [

105]. There are four types of phycobilins, with different light absorption characteristics: phycocyanobilin (λ

max = 640 nm), phycoerythrobilin (λ

max = 550 nm), phycourobilin (λ

max = 490 nm), and phycobiliviolin (λ

max = 590 nm) (

Figure 5) [

101,

105].

Some authors [

106] described the strain of

Tolypothrix nodosa with the ability to produce toliporphins, which comprise a family of tetrapyrroles. Metagenomic surveys have revealed a diversity of bacteria dominated by Erythrobacteraceae, 97% of which are

Porphyrobacter species.

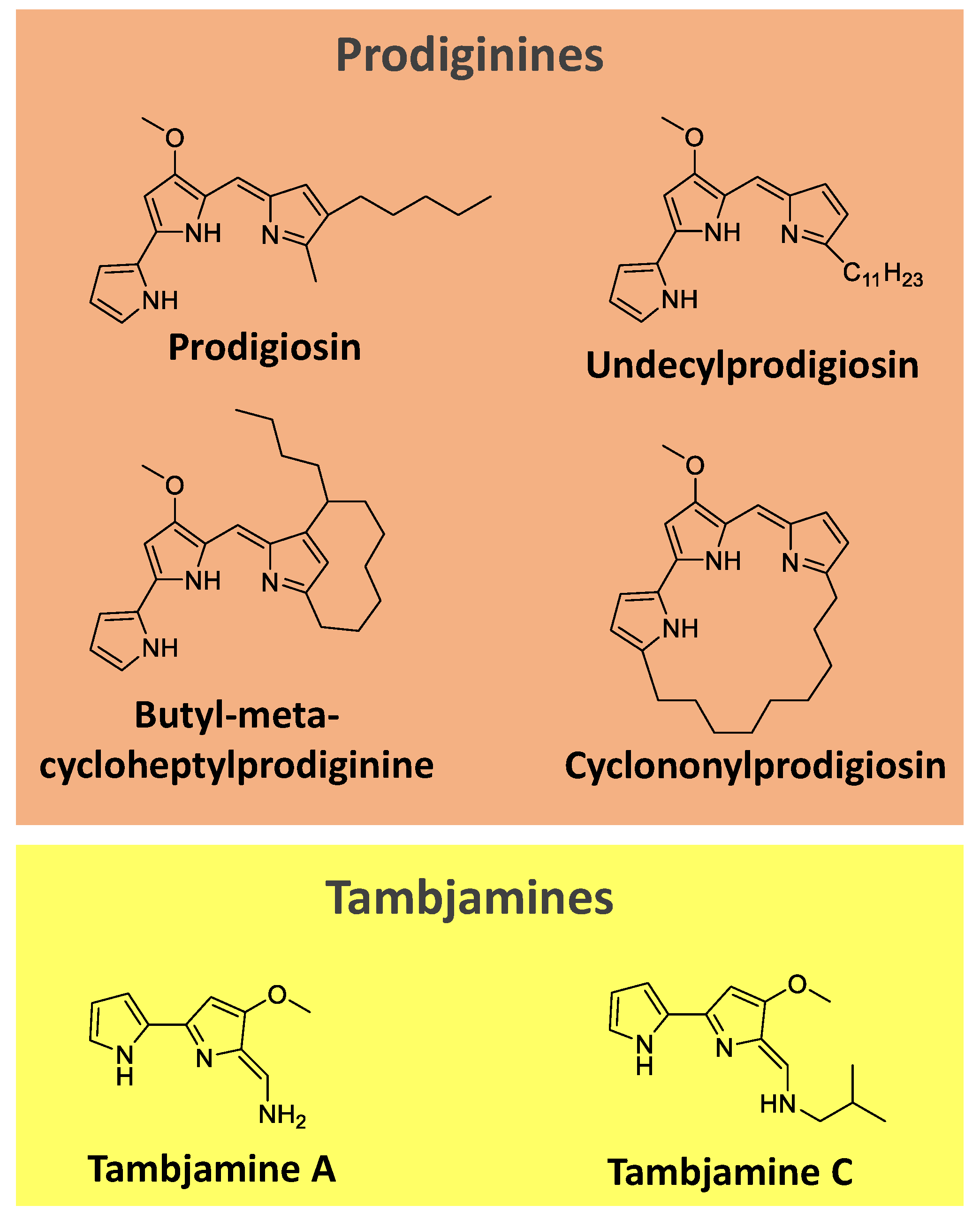

6.4. Other Pyrrole-Based Pigments: Prodiginines and Related Compounds

Prodiginines are a group of hydrophobic red tripyrrole pigments produced by

Serratia spp., actinomycetes, and some marine bacteria. The most known pigment of the class is prodigiosin (

Figure 7), produced mainly by

Serratia marcescens. Prodiginines can have a straight chain, such as prodigiosin and undecyl prodigiosin, or can bear a cyclic structure, like cyclononylprodigiosin and butyl-meta-cycloheptylprodiginine (

Figure 7) [

65,

107].

Tambjamines are another class of yellow pigments closely related to the prodiginines. They have a bipyrrole core condensed with a primary amine instead of a monopyrrole. Examples include tambjamine A and C (

Figure 7). Tambjamines are found in bacteria (e.g.,

Pseudoalteromonas spp.) and marine invertebrates (e.g., g bryozoans, nudibranchs, and ascidians) [

108,

109,

110].

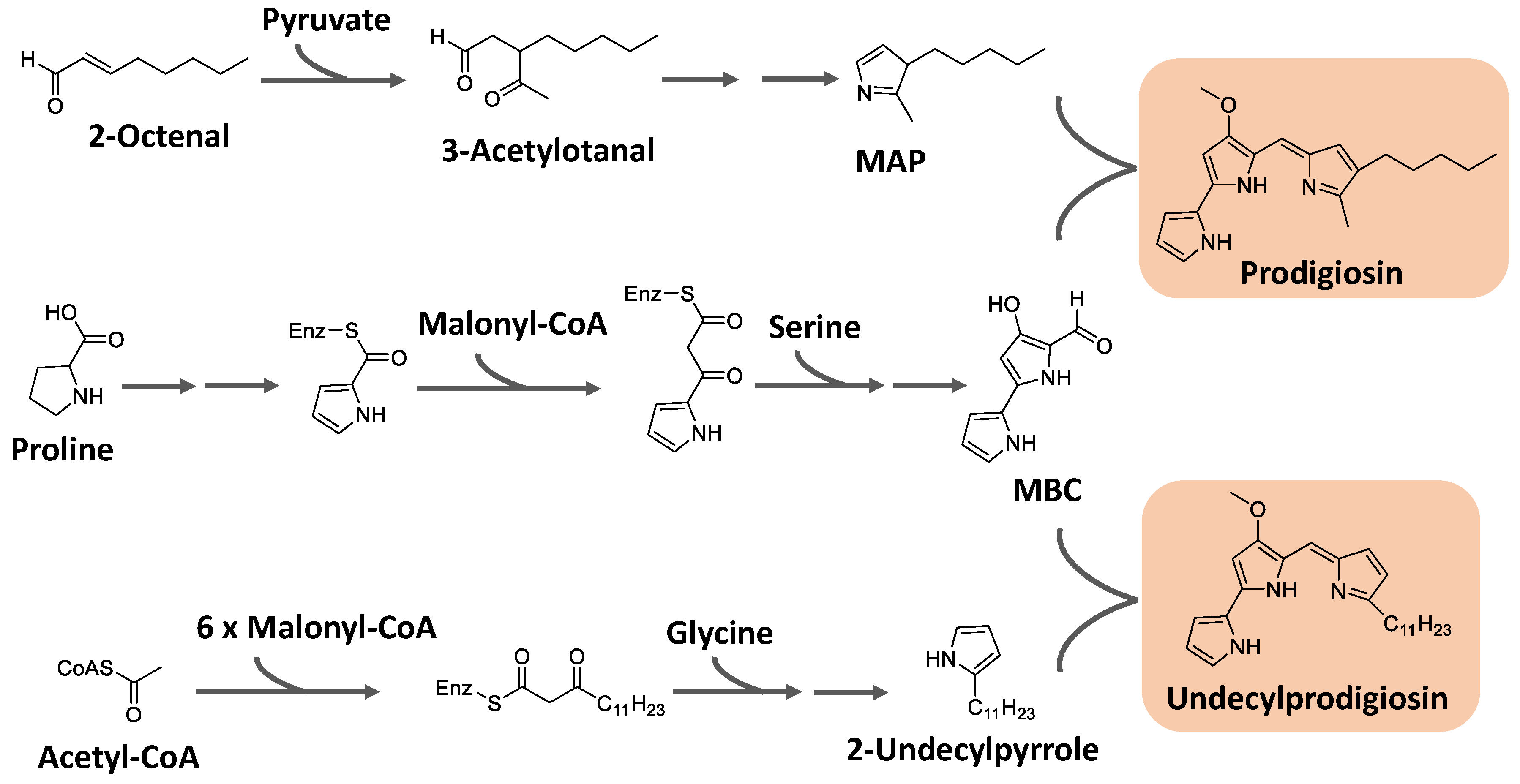

Prodiginines are biosynthesized through a bifurcated pathway that ends up with the enzymatic condensation of the bipyrrole molecule 4-methoxy-2-2′-bipyrrole-5-carbaldehyde (MBC) with a monopyrrole unit, which can be 2-methyl-3-pentylpyrrole, also known as 2-methyl-3-n-amyl-pyrrole (MAP), or 2-undecylpyrrole (

Figure 8). MBC is biosynthesized from proline, serine, and malonyl-CoA units. The monopyrrole portions originate from different substrates with different enzymatic apparatus. MAP has the fatty acid derivative 2-octenal and pyruvate as precursors, while 2-undecylpyrrole is biosynthesized from acetyl-CoA/malonyl-CoA units and glycine [

107,

111].

Kurbanoglu

et al. [

112] described that although

S. marcescens is the largest producer of prodigiosin, this pigment is also produced by other bacteria, such as

Streptomyces coelicolor,

S. lividans,

Hahella chejuensi,

Pseudovibrio denitriccans,

Pseudoalteromonas rubra,

P. denitrificans,

Vibrio gazogenes,

V. psychroerythreus,

Serratia plymuthica and

Zooshikella rubidus. Indeed, other authors [

113] inferred that the biopigment prodigiosin as a red alkaloid dye produced by several microorganisms with a linear tripyrrole chemical structural formula. According to the authors, prodigiosin has a broad spectrum of bioactive factors, such as antibacterial, antifungal, algaecidal, anti-Chagas, antiamoebic, antimalarial, anticancer, antiparasitic, antiviral, and/or immunosuppressive.

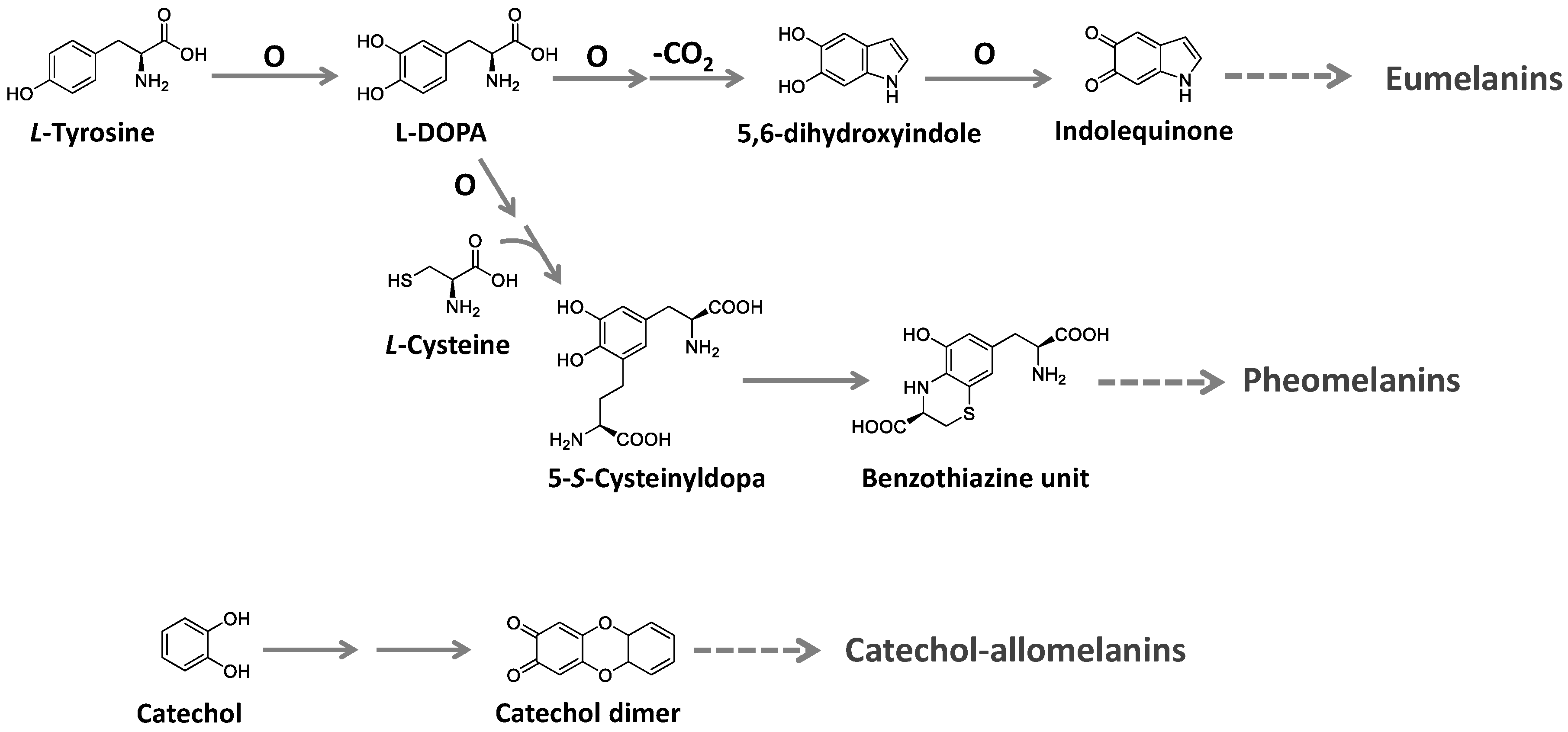

6.5. Melanins

Melanins are ubiquitous high molecular-weight pigments formed by the oxidative polymerization of phenolic compounds. They are stable, insoluble, and usually brown or black [

114,

115,

116]. Three major types of melanins are recognized: eumelanins, pheomelanins, and allomelanins. Eumelanins are found in animals, fungi, and some microorganisms. They are biosynthesized from tyrosine with the participation of the enzyme tyrosinase and have 5,6-dihydroxyindole as the main building block. Pheomelanins, present in higher animals (mammals, birds, and reptiles), differ from eumelanins by sulfur, incorporated from

L-cysteine to the tyrosine-derived units, forming benzothiazine and benzothiazole building blocks. Allomelanins, on the other hand, consist of a heterogeneous group found in plants and fungi. These melanins are devoid of nitrogen atoms and are formed from different nitrogen-free precursors, such as catechol, the most common, and gamma-glutaminyl-3,4-dihydroxybenzene 1,8-dihydroxy naphthalene, as well as caffeic, chlorogenic, protocatechuic, and gallic acids [

114,

116]. The biosynthesis of these groups is summarized in

Figure 9.

Rao

et al. [

117] described the production of different types of melanins by a wide variety of microorganisms, such as

Colletotrichum lagenarium,

Magnaporthe grisea,

Cryptococcus neoformans,

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis,

Sporothrix schenckii,

Aspergillus fumigates,

Vibrio cholerae,

Shewanella colwelliana,

Alteromonas nigrifaciens and many species of the genus

Streptomyces. Furthermore, a recent work described the remarkable production of melanins in bacteria isolated from sponges, suggesting that these microorganisms are potential sources for industrial melanin production [

118]. These results suggested that bioprospecting for melanin-producing bacteria, including those associated with other organisms or living in extreme environments, could help find melanin hyperproducers or extremozymes that could increase melanin yields.

6.6. Quinones and Azaphilones

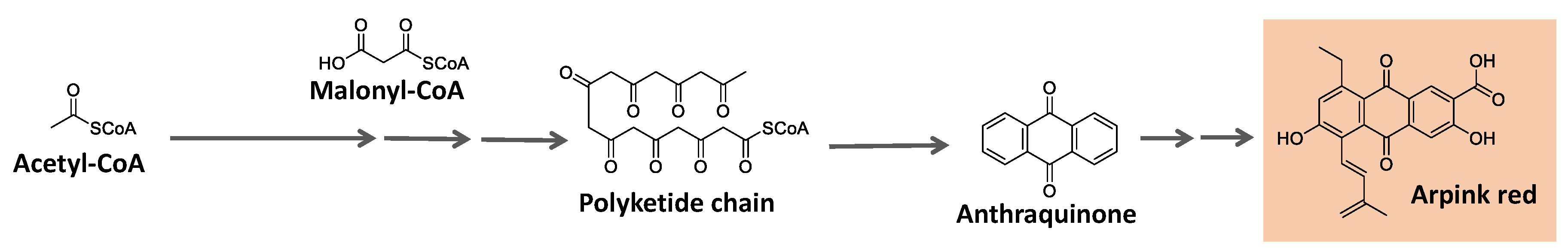

Some natural pigments assume a quinone (fully conjugated cyclic dione) scaffold, ranging from yellow to red [

119]. One example is arpink red produced by the fungus

Penicillium oxalicum [

120] (

Figure 10).

Quinones are derived from oxidizing suitable phenolic compounds [

121]. The acetate/mevalonate or shikimate pathways can form them from biosynthesized phenolic systems. The former involves condensing acetyl-CoA/malonyl-CoA units to form a polyketide chain subject to appropriate folding and cyclization, as summarized in

Figure 10 [

121,

122,

123].

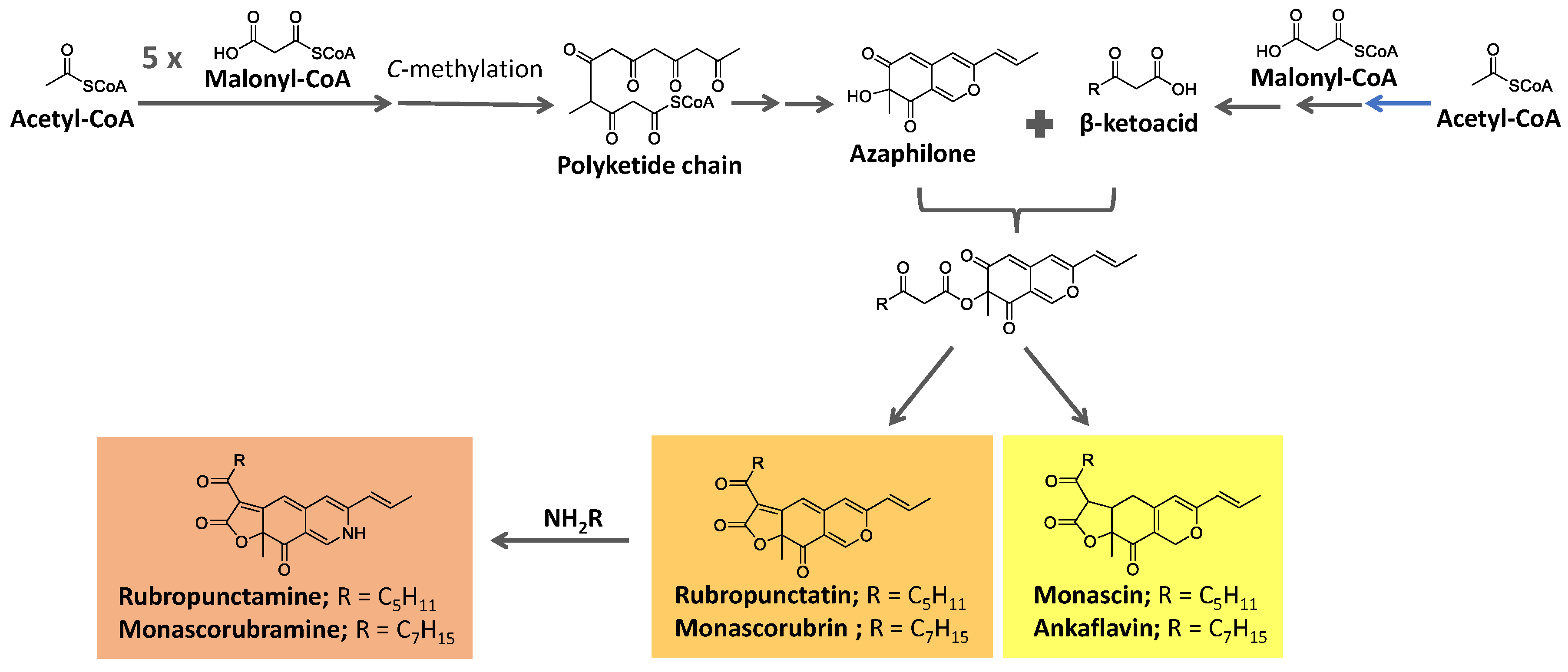

Azaphilone pigments, produced by filamentous fungi

Monascus spp, have a typical bicyclic chromophore. Six of them are well known (

Figure 11): the yellow pigments monascin and ankaflavin (λ

max = 330-450 nm), the orange pigments rubropunctatinand monascorubrin (λ

max = 460-480 nm), and the red pigments monascorubramine and rubropunctamine (λ

max = 490-530 nm) [

124,

125,

126].

These pigments are biosynthesized from precursors from the acetate/malonate pathway. They are proposed to be formed from the esterification of the polyketide-derived azaphilone chromophore with a β-ketoacid. These precursors are biosynthesized under the action of polyketide synthase (PKS) and fatty acid synthase (FAS), respectively [

125,

126,

127], as summarized in

Figure 11. The reaction of orange molecules with a primary amine, known as aminophilic reaction, would lead to the red substances, in which the heterocyclic oxygen is replaced by a nitrogen atom [

125].

6.7. Other Pigments

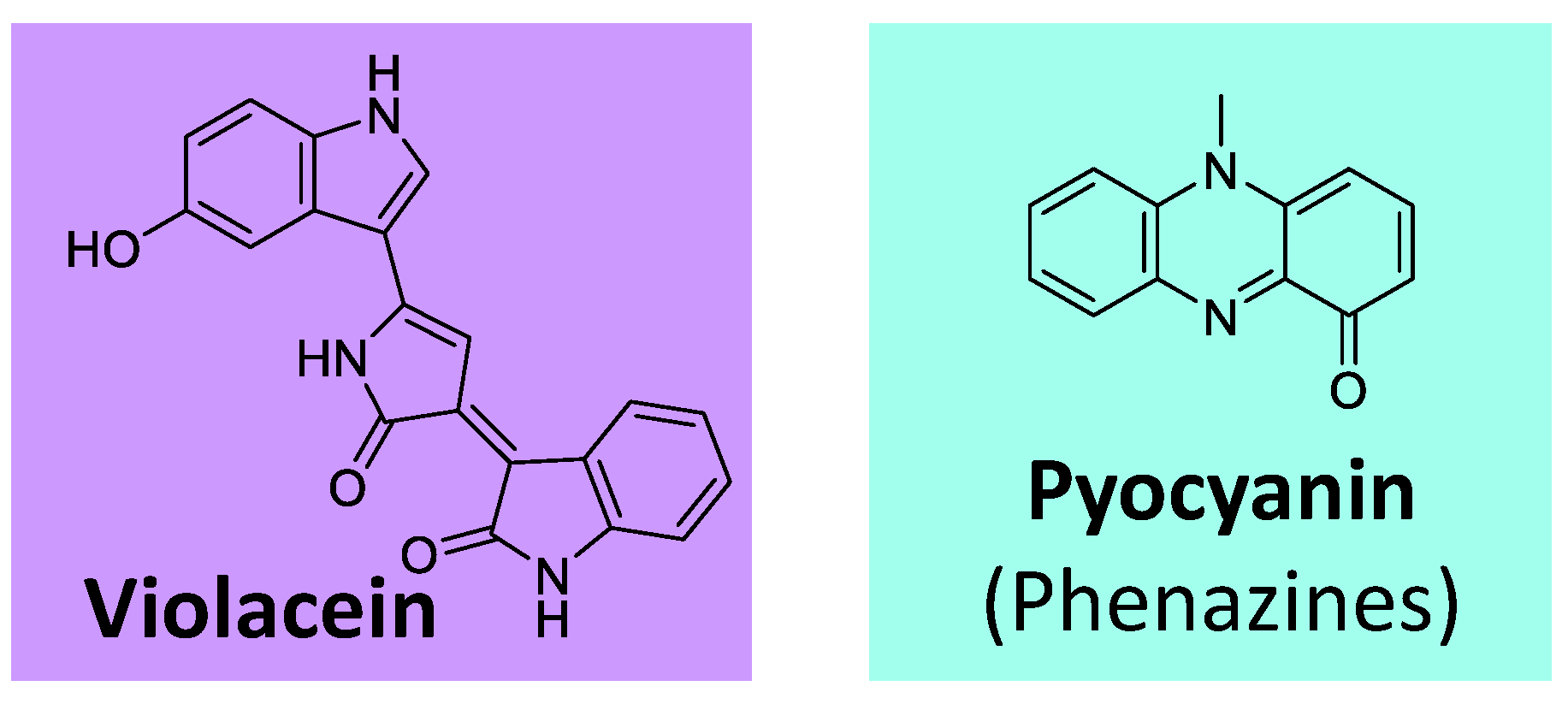

Besides the classes of pigments discussed in the previous topics, some others are worth mentioning. Violacein is an example (

Figure 12), an indole-violet/blue pigment biosynthesized from tryptophan. It is produced by various bacteria genera, such as

Chromobacterium, Collimonas, Duganella, Janthinobacterium, and

Pseudoalteromonas [

119,

128,

129].

Additionally, phenazines represent a group of aromatic

N-heterocyclic pigments produced by many bacteria, such as

Pseudomonas sp,

Nocardia sp,

Burkholderia sp,

Streptomyces sp, and

Vibrio sp [

119,

130]. These compounds, which can present several colors (purple, blue, green, yellow, red, and brown), derive from the shikimate pathway [

119,

131]. The most known example is the blue phenazine pyocyanin (

Figure 12), produced by

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

130,

131].

7. Pigment Market

According to a publication of Allied Market Research in 2023, the pigments market has been growing, valued at 1.8 billion dollars in 2021, considering the carotenoids segment alone. It is projected to reach

$2.7 billion by 2031, growing at a CAGR of 3.9% from 2022 to 2031. Inside this market, natural pigment additives are more focused by Europe and the US to reduce health impacts in the population that consumes artificially colored foods. In addition, FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has already approved the consumption and commercialization of some pigments derived from plants and microorganisms for human consumption as food additives, such as Arpink Red (

Penicillium oxalicum) and astaxanthin (

Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous) [

132,

133,

134,

135].

One of the significant advantages of microbial metabolites is their suitability in high demand for "natural,” "

biodegradable," and "

eco-friendly," for instance. These possibilities help construct a good image and status for the brands and industries that use them, influencing the consumer to trust the product. Marketing for natural product consumption supports advertising campaigns that constantly expand this market, pushing it for innovations to reach more and more market shares. Recent data shows that the global organic pigment market is expected to generate around 4.89 billion USD by 2024 [

136,

137].

Among the microbial pigments, the most applied in the industry are those extracted from microalgae and fungi, with less use of those from the bacterial group[

137,

138].

Pigments that bring antioxidant characteristics, for example, can increase the product's shelf life or even reduce the addition of other compounds commonly added in formulations. These gains must be analyzed case-by-case for each formulation and pigment; however, this opens a new horizon in the study, production, and use of microbial metabolites in different industry sectors, replacing traditional dyes and pigments [

3].

Carotenoids already have an expanding place in food coloring in the food industry. However, its vibrant colors vary in scales from yellow to red, depending on the type of carotenoid. It is also possible to use as an enhancer to treat cases of low intake or hypovitaminosis of vitamin A. It is known that some carotenoids, such as 𝛃-carotene have an orange color and are naturally present in some foods, such as carrots and pumpkin. It is a provitamin A agent, acting as a precursor of retinol; in this way, it can be produced by microorganisms and work as an additive in other foods that naturally do not have retinol or provitamin A, such as juices, butter, creams, milk and even sweets [

3].

8. Biotechnological Applications

8.1. Pharmaceutical and Medicine

Pharmaceutical and medicinal industries use pigments from different sources, such as microbial or higher algae and plants, because of their bioactive properties, adding value to the products. Pigments can be used as antimicrobial metabolites; many of the pigments already presented have antibacterial and antifungal activities. This property can benefit pharmaceutical and cosmetics formulations, increasing the safety of formulations and products' shelf life, especially the most perishable ones [

3]. The antimicrobial activity includes viruses ( e.g., prodiginines), bacteria (e.g., Pyocyanin), and fungi (e.g., violacein) [

139]. Several microbial pigments, such as melanin, prodigiosin, violacein, and others, present anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties described [

73,

140,

141,

142]. As demanded by pharmaceutical industries, studies have been conducted regarding microbial metabolites for discovering new bioactive compounds, including pigments. Prodigiosin from S. marcescens is well-known for its bioactive properties, and it has been described as a drug candidate for therapy in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [

143]. Recently, authors have described sclerotiorin, rubropunctamine, and bostrycoidin pigments from Penicillium multicolour, Talaromyces verruculosus, and Fusarium solani, respectively, presented antioxidant and antimicrobial activities against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [

73]. An anthraquinone pigment produced by T. purpureogenus was purified and exhibited antioxidant activity, anticancer properties against tumor cell lines, and being pointed as a potent agent for kidney cancer diagnosis [

57]. Antibiofilm property was also described in a study investigating the therapeutic characteristics of a pigment from P. mallochi ARA1 [

136]. The development and studies of novel natural pigment compounds are continuous in scientific literature and are a broad field to explore.

8.2. Cosmetics

Artificial or natural inorganic and organic pigments are primary sources of coloration in the cosmetics industry. Nevertheless, bio-based colorants are sought for sustainable concepts and additive functions such as antimicrobial and antioxidant activities found in these bioproducts [

144]. Plant pigments are well-known sources for the cosmetics industry [

144,

145,

146].

Regarding natural sources from microbial origin, microalgae and cyanobacteria are producers of high-value pigments such as carotenoids, phycocyanins, and chlorophylls for developing product colors with tons of yellow, orange, red, green, and blue, for example [

147,

148,

149]. The application of microalgae for the production of pigments and other bioproducts, such as vitamins and lipids, has been supported by scientists due to their possible integration into biorefinery and sustainable production in the industry [

150]. Various genera of bacteria and fungi have been described and studied for melanin production, which can be applied in the cosmetics industry as an ingredient in dermal products, such as sunscreen, due to high UV light protection properties. In addition, anticancer, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activities have been described [

151,

152]. The vast bioactive properties and different types of microbial pigments demonstrate the potential of microbial pigments to be applied to the cosmetics industry [

153], such as sunscreen, makeup, antiaging, skin lightening, and even for tattoos and permanent dyes combining the biological activity and coloring property. These applications are not yet widely explored by the industry. However, it is a promising appeal for this sector [

154,

155].

8.3. Food Industry

The food industry is notoriously the industrial field with the highest application of the use of microbial pigments. Pigments may be one of the most critical components in food because food color is an essential sensorial characteristic for consumer acceptance. Besides the sensorial aspect, natural pigments have been preferred in the food industry due to their potential health effects, in contrast to artificial colorants, as well as a conserving and shelf-life extending agent due to their antioxidant properties [

156]. Natural pigments already represent one-third of the pigment additive market in the food production sector, mainly in the carotenoid class, whose prominent representatives are 𝛃-carotene and astaxanthin. As seen in

Table 2, numerous microbial species can produce both and are already a reality in industrial food applications [

137].

Some pigments, namely riboflavin (from

B. subtilis), β-carotene (from

Blaskslea trispora and

Dunaliella salina), lycopene (

B. trispora), astaxanthin and canthaxanthin (

Haematococcus lacustris) have been already extracted and commercialized in current global market [

157]. Microbial canthaxanthin is used as a pigment additive for poultry and salmon feed. It can be obtained through the bacteria

Bradyrhizobium sp. and

Lactobacillus pluvalis [

158,

159]. Authors comment on the possibility of applying astaxanthin as an antioxidant in animal or human food and as it promotes a yellowish color [

160]. In some cases, astaxanthin supplementation can even accelerate the animal's growth and, as in the case of trout (

Oncorhynchus mykiss), optimize the production chain for the food industry [

161]. Supplementation in animal feed is usually used because canthaxanthin in the ration contributes to the pigmentation of animal muscle tissue, as in the case of salmon and shrimps, in the production of eggs, in chickens, and in obtaining more vivid colors in birds and canaries. Furthermore, canthaxanthin is an antioxidant that can help control free radicals in these animals and fertility [

162,

163,

164].

Chlorophylls from several microalgae origin (

Chlorella spp.,

Tetraselmis spp.,

Arthospira spp.) are widely used in the food industry for green colorants in addition to their bioactive properties, anticancer for example [

165]. For instance, a colored functional oil rich in fatty acids and antioxidants from

C. vulgaris microalgae was developed using less environment-harmful technology (supercritical CO

2 extraction) [

166]. Similarly, a yellowish pigment from

M. purpureus H14 fungi was studied for application in a functional rice noodle since it provided more stability, quality, and texture to the product apart from its bioactive properties (anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, anti-fatty) [

167].

Application of microbial pigments in food must be approved and meet the requirements of regulation and legislation institutions, such as GRAS (

Generally Regarded as Safe) label and FDA (

Food and Drug Administration, USA), which some microbial producers already have [

165,

168]. To conclude, even with some usage limitations (instability and costs, for example), microbial pigments are in high demand for the food market. They are trending to increase production and application in future years [

168].

8.4. Textile Industry

Applying microbial pigments for dyeing fabrics is not a common practice in industries. It has still been little explored in scientific research. However, some more recent and initial work shows the use of the pigment in different fabric types. They are divided into three stages: preparation of the dyeing solution containing the microbial pigment color fixing additives, hot dyeing (60-80ºC), and washing and drying the dyed fabric [

169].

Violacein pigment with bioactive properties (antimicrobial and antioxidant) was investigated for application in textile purposes [

170]. The authors extracted violet/purple pigment from the bacterial producer

Chromobacterium violaceum to dye cotton and silk. Good results were obtained on a small scale with color stability after the dyeing, washing, and drying. Furthermore, hot-dyed strips of cotton fabric with dark green pigment extracted from the fungus of the genus

Sclerotinia were prepared after successive washing and exposure to the sun [

171].

Bisht et al. [

172] proposed using antimicrobial pigments to develop an antimicrobial textile fabric in the textile industry. A crude extract of red pigments from

Rhodonellum psychrophilum was applied on cotton, rayon, and silk fabrics. Penetration and fixation of the pigment were observed, but without maintaining a vibrant color. Likewise, a red pigment produced by

Talaromyces albobiverticillius fungi in fermentation using agro-industrial waste was studied for dyeing cotton fabric and presented antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, showing a promising path of developing textile materials with bioactive properties [

173].

9. Metabolic Engineering

Due to the importance of microbial pigments and their industrial application, synthetic biology, and metabolic engineering strategies have been developed to optimize yield production and reduce bioprocess costs in this area. For this purpose, different strategies are used to build new biosynthetic pathways by recombining multiple target genes or regulating crucial molecule precursors in the biochemical chain to enhance the final yield of a bioproduct. They appear as an essential tool for the future market of these bioproducts [

149,

174]. The possibility of genetic engineering expands the perspectives of the production and application of microbial pigments, which can have their process optimized. These overexpressed genes regulate pigment production, growth, and fermentation in different culture conditions, cloning of genes in different microbial species more adapted to industrial processes, among other possibilities [

139].

Science fields, including microbiology, were strengthened in the 2000s after multi-omic (genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, proteomics) approaches were developed. In microbial biotechnology, they provided a rapid expansion of knowledge of molecular biology and metabolic pathways in microorganisms and the possibility of gene editing in microorganisms for specific applications [

149,

175]. Moreover, artificial intelligence can be used with omics sciences for better investigation and gene assembly of microbial agents in biotechnology. In this scenario, multi-omics can provide microalgae data to be inputted into computational systems biology and machine learning (heatmap analysis, clustering, neural network, and others), followed by a guided confirmation in the laboratory once target genes and metabolic pathways are identified. By combining multi-omics and predictive microbiology mathematical models, for example, it is possible to predict microbial growth or optimize culturing processes involved in their bioproduct production, including pigments [

176].

In the context of the present review, metabolomic was an important tool used in a work that successfully studied an enhanced production of lutein carotenoid by

Chlorella saccharophila strain in co-cultivation with a novel

Exiguobacterium sp. [

177]. In this work, metabolomics permitted authors to identify metabolites from microalgae and bacteria cultures alone and together, in addition to observing more than 40 metabolites unique when in co-culture. Another work used multi-omic tools for studying the production of carotenoids in

Isochrysis galbana microalgae and the involved genes under different light conditions during growth [

178].

Synthetic biology is a well-known tool in the biotechnology of pigments and their microbial producers due to the possibility of controlling and improving the biosynthesis of a bioproduct through modification in microbial genes. Researchers construct heterogeneous synthesis pathways after identifying functional genes for pigment production chains by direct cloning or through a metagenomics tool, followed by pathway assembly targeting the recombination of target genes (plasmid or plasmid-free techniques) [

174]. Following this concept, an increased yield of 𝛽-carotene was obtained after expressing three lipase and carotene pathway encoding genes from other microbial genera into the baker yeast

Saccharomyces cerevisiae [

179]. In a combinatorial multi-gene pathway assembly, lycopene pigment production was increased three times in an expression in

E. coli [

180]. Lycopene production was also incremented in another work that used recombinant genes in engineered yeasts (

S. cerevisiae) to optimize lipid production to pigment accumulation reaching up to 73.3 mg/cell dry weight [

181].

Biochemical engineering technology was used to regulate the biosynthesis of pigments from a mutant strain of the filamentous fungi

Monascus purpureus LQ-6, which produces several bioactive compounds [

182]. This technology consists of adding exogenous compounds in fermentation to alter cell metabolism, thus easing the regulation of target bioproducts. The authors observed that by adding 1.0 mg/L of methyl viologen and rotenone as cofactor agents, total yield production of pigment increased by approximately 40% and yellow pigment production by around 114%, respectively. The same work also showed that pigments changed from red to yellow through an electrolytic stimulation, with no citrinin, a mycotoxin produced by these strains. Other metabolic engineering strategies, such as extractive fermentation [

183] and low-frequency magnetic field exposure [

184], were also investigated for pigment production in

Monascus spp. strains. These examples and others found in the scientific literature show that the future of metabolic engineering is a promising tool for pigment development studies.

10. Conclusion

Microbial pigments are secondary metabolites derived from the most different species of microorganisms present in nature, including microbes already adapted to human interaction without presenting pathogenicity. Their use until the present time is underestimated and presents a range of alternatives in the replacement of traditional mineral and synthetic dyes. Even though there are still some barriers to its large-scale production, its application to the most diverse industrial sectors is covered with possibilities, such as the pharmaceutical, food, textile, and cosmetics industries. They can even play roles as colorants and additives to improve formulations, with their bioactive properties (antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, among others. More investments in the segment, regulations, and legislation are necessary for their production, application, and commercialization.

Biotechnology can be the key to sustainable development, thus anticipating and solving consumption-related problems. The process can continually be optimized to reduce downstream processes and environmental impacts, produce more stable pigments, use by-products from other sectors as fermentation substrates, and discover new pigments and their applications. There are still steps to be overcome, but microbial pigments offer economic, environmental, industrial, and significant commercial appeal potential, and, with investment, they can become the primary source of natural pigments and help reduce the use of synthetic pigments in the industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing, topic research, JVOB; writing; Pigments structures, topic research and formal analysis, LMC; writing, topic research, draft preparation ANJ; writing, topic research, editing; MCRM; conceptualization, writing, review, editing, project administration, and funding acquisition, ABV. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Postgraduate Program in Plant Biotechnology and Bioprocesses, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), through the Coordination of Aperfeiçoamento Pessoal de Ensino Superior (CAPES) [grant number 001], Conselho National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (MCTI-CNPq) grant code [309461/2019-7] and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), grant 'Cientista do Nosso Estado E26/200428/2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the study's design, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results

References

- Kumar, A.; Vishwakarma, H.S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, M. MICROBIAL PIGMENTS: PRODUCTION AND THEIR APPLICATIONS IN VARIOUS INDUSTRIES. IJPCBS 2015, 5, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.; Tiwari, K.S.; Gupta, C.; Tiwari, M.K.; Khan, A.; Sonkar, S.P. A Brief Review on Natural Dyes, Pigments: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Results Chem. 2023, 5, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, T.; Barrow, C.J.; Deshmukh, S.K. Microbial Pigments in the Food Industry—Challenges and the Way Forward. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, H.; Bajpai, S.; Mishra, A.; Kohli, I.; Varma, A.; Fouillaud, M.; Dufossé, L.; Joshi, N.C. Bacterial Pigments and Their Multifaceted Roles in Contemporary Biotechnology and Pharmacological Applications. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Li, Y.; Lawson, D.; Xie, D.-Y. Metabolic Engineering of Anthocyanins in Dark Tobacco Varieties. Physiol. Plant. 2017, 159, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, I.C.; Allen, W.L.; Arbuckle, K.; Caspers, B.; Chaplin, G.; Hauber, M.E.; Hill, G.E.; Jablonski, N.G.; Jiggins, C.D.; Kelber, A.; et al. The Biology of Color. Science 2017, 357, eaan0221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.H.; Strack, D. Carotenoids and Their Cleavage Products: Biosynthesis and Functions. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlawat, G.; Choudhury, A.R. A Review on the Biosynthesis of Metal and Metal Salt Nanoparticles by Microbes. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 12944–12967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-Barrera, A.M.; Areiza, D.; Zapata, P.; Atehortúa, L.; Correa, C.; Peñuela-Vásquez, M. Induction of Pigment Production through Media Composition, Abiotic and Biotic Factors in Two Filamentous Fungi. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 21, e00308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincke, G. Molecular Stacks as a Common Characteristic in the Crystal Lattice of Organic Pigment Dyes A Contribution to the “Soluble–Insoluble” Dichotomy of Dyes and Pigments from the Technological Point of View. Dyes Pigments 2003, 59, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothon, R Pigment and Nanopigment Dispersion Technologies. In Pigment and Nanopigment Dispersion Technologies; iSmithers Rapra Publishing, 2012 ISBN 978-1-84735-909-4.

- Arora, K.; Ameur, H.; Polo, A.; Di Cagno, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Gobbetti, M. Thirty Years of Knowledge on Sourdough Fermentation: A Systematic Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Mesquita, L.M.; Martins, M.; Pisani, L.P.; Ventura, S.P.M.; De Rosso, V.V. Insights on the Use of Alternative Solvents and Technologies to Recover Bio-based Food Pigments. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 787–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkaczyk, A.; Mitrowska, K.; Posyniak, A. Synthetic Organic Dyes as Contaminants of the Aquatic Environment and Their Implications for Ecosystems: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, R. Textile Dyeing Industry an Environmental Hazard. Nat. Sci. 2012, 04, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oginawati, K.; Suharyanto; Susetyo, S. H.; Sulung, G.; Muhayatun; Chazanah, N.; Dewi Kusumah, S.W.; Fahimah, N. Investigation of Dermal Exposure to Heavy Metals (Cu, Zn, Ni, Al, Fe and Pb) in Traditional Batik Industry Workers. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccato, A.; Moens, L.; Vandenabeele, P. On the Stability of Mediaeval Inorganic Pigments: A Literature Review of the Effect of Climate, Material Selection, Biological Activity, Analysis and Conservation Treatments. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzum, N.; Khan, F.I.; Hossain, M.Z.; Islam, M.N.; Saha, M.L. Isolation and Identification of Pigment Producing Bacteria From the Ratargul Swamp Forest Soil. Dhaka Univ. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.; Selinger, B. The Chemistry of Cosmetics. Aust. Acad. Sci. 2019.

- Veuthey, T. Dyes and Stains: From Molecular Structure to Histological Application. Front. Biosci. 2014, 19, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, M.A.; Seddigi, Z.S.; Nasr, M.M.; Gondal, B. Spectroscopic Detection of Health Hazardous Contaminants in Lipstick Using Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 175, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsahida, K.; Fauzi, A.M.; Sailah, I.; Siregar, I.Z. Sustainability of the Use of Natural Dyes in the Textile Industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 399, 012065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalek, I.M.; Benn, E.K.T.; Dos Santos, F.L.C.; Gordon, S.; Wen, C.; Liu, B. A Systematic Review of Global Legal Regulations on the Permissible Level of Heavy Metals in Cosmetics with Particular Emphasis on Skin Lightening Products. Environ. Res. 2019, 170, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sairam Mantri; Mallika Dondapati; Krishnaveni Ramakrishna; Amrutha V. Audipudi; Srinath B.S. Production, Characterization, and Applications of Bacterial Pigments- a Decade of Review. Biomedicine 2022, 42, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrio, E.S.; Ferreira, G.G.; Zuqui, S.N.; Silva, A.G. Plant Resources in Biocosmetic: A New Concept on Beauty, Health, and Sustainability. ESFA 2011, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Doulati Ardejani, F.; Badii, Kh.; Limaee, N.Y.; Shafaei, S.Z.; Mirhabibi, A.R. Adsorption of Direct Red 80 Dye from Aqueous Solution onto Almond Shells: Effect of pH, Initial Concentration and Shell Type. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 151, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bom, S.; Jorge, J.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto, J. A Step Forward on Sustainability in the Cosmetics Industry: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Wang, X.; Gao, S.; Li, D.; Zhou, J. Production of Natural Pigments Using Microorganisms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 9243–9254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikshit, R.; Tallapragada, P. Comparative Study of Natural and Artificial Flavoring Agents and Dyes. In Natural and Artificial Flavoring Agents and Food Dyes; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 83–111 ISBN 978-0-12-811518-3.

- Bisbis, M.B.; Gruda, N.; Blanke, M. Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Vegetable Production and Product Quality – A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1602–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U.; Oba, S. Salinity Stress Enhances Color Parameters, Bioactive Leaf Pigments, Vitamins, Polyphenols, Flavonoids and Antioxidant Activity in Selected Amaranthus Leafy Vegetables. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2275–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, C.R.; Rasco, B.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S. Natural Color Pigments: Oxidative Stability and Degradation Kinetics during Storage in Thermally Pasteurized Vegetable Purees. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 5934–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M.; Shabbir, M.; Mohammad, F. Natural Colorants: Historical, Processing and Sustainable Prospects. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2017, 7, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamim, G.; Ranjan, S.K.; Pandey, D.M.; Ramani, R. Biochemistry and Biosynthesis of Insect Pigments. Eur. J. Entomol. 2014, 111, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Maatsch, J.; Gras, C. The “Carmine Problem” and Potential Alternatives. In Handbook on Natural Pigments in Food and Beverages; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 385–428 ISBN 978-0-08-100371-8.

- Dave, S.; Das, J.; Varshney, B.; Sharma, V.P. Dyes and Pigments: Interventions and How Safe and Sustainable Are Colors of Life!!! In Trends and Contemporary Technologies for Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes; Dave, S., Das, J., Eds.; Environmental Science and Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-3-031-08990-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Ambika, A.A.A.; Nag, D.; Kumar, V.; Darnal, S.; Thakur, V.; Patial, V.; Singh, D. Microbial Pigments: Learning from Himalayan Perspective to Industrial Applications. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, kuac017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rather, L.J.; Mir, S.S.; Ganie, S.A.; Shahid-ul-Islam; Li, Q. Research Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives in Microbial Pigment Production for Industrial Applications - A Review. Dyes Pigments 2023, 210, 110989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermelho, A.B.; Noronha, E.F.; Filho, E.X.F.; Ferrara, M.A.; Bon, E.P.S. Diversity and Biotechnological Applications of Prokaryotic Enzymes. In The Prokaryotes; Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Thompson, F., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 213–240. ISBN 978-3-642-31330-1. [Google Scholar]

- Scarano, P.; Naviglio, D.; Prigioniero, A.; Tartaglia, M.; Postiglione, A.; Sciarrillo, R.; Guarino, C. Sustainability: Obtaining Natural Dyes from Waste Matrices Using the Prickly Pear Peels of Opuntia Ficus-Indica (L.) Miller. Agronomy 2020, 10, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.C.; Ligabue-Braun, R. Agro-Industrial Residues: Eco-Friendly and Inexpensive Substrates for Microbial Pigments Production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 589414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Lyu, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, W.; Ye, L.; Yang, R. Biotechnological Advances for Improving Natural Pigment Production: A State-of-the-Art Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Q.; Sun, T.; Zhu, X.; Xu, H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y. Engineering Central Metabolic Modules of Escherichia Coli for Improving β-Carotene Production. Metab. Eng. 2013, 17, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, H.S.; Chaudhary, P.; Beniwal, V.; Sharma, A.K. Microbial Pigments as Natural Color Sources: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 4669–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Singh, S.; Ghoshal, G.; Ramamurthy, P.C.; Parihar, P.; Singh, J.; Singh, A. Valorization of Agri-Food Industry Waste for the Production of Microbial Pigments: An Eco-Friendly Approach. In Advances in Agricultural and Industrial Microbiology; Nayak, S.K., Baliyarsingh, B., Mannazzu, I., Singh, A., Mishra, B.B., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 137–167. ISBN 9789811689178. [Google Scholar]

- Panesar, R.; Kaur, S.; Panesar, P.S. Production of Microbial Pigments Utilizing Agro-Industrial Waste: A Review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 1, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirti, K.; Amita, S.; Priti, S.; Mukesh Kumar, A.; Jyoti, S. Colorful World of Microbes: Carotenoids and Their Applications. Adv. Biol. 2014, 2014, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhia, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R. Antioxidant Prodigiosin-Producing Cold-Adapted Janthinobacterium Sp. ERMR3:09 from a Glacier Moraine: Genomic Elucidation of Cold Adaptation and Pigment Biosynthesis. Gene 2023, 857, 147178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. M. Hassan Et Al., S. Microbial Pigments: Sources and Applications in the Marine Environment. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2022, 26, 99–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, Z.; Sharma, M.; Awasthi, A.K.; Sivakumar, N.; Lukk, T.; Pecoraro, L.; Thakur, V.K.; Roberts, D.; Newbold, J.; Gupta, V.K. Bioprocessing of Waste Biomass for Sustainable Product Development and Minimizing Environmental Impact. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 322, 124548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allied Market Research Carotenoids Market Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2021-2031. 2023.

- Martins, G.B.C.; Sucupira, R.R.; Suarez, P.A.Z. A Química e as Cores. Rev. Virtual Quim 2015, 7, 1508–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavia, D.L.; Lampman, G.M.; Kriz, G.S. Introduction to Spectroscopy: A Guide for Students of Organic Chemistry. In; 2001 ISBN 0-03-031961-7.

- Sinha, S.; Choubey, S.; Kumar, A.; Bhosale, P. Identification, Characterization of Pigment Producing Bacteria from Soil and Water and Testing of Antimicrobial Activity of Bacterial Pigments. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res 2017, 42, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Aruldass, C.A.; Dufossé, L.; Ahmad, W.A. Current Perspective of Yellowish-Orange Pigments from Microorganisms- a Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Yang, J.E.; Choi, Y.J. Isolation and Characterization of a Yellow Xanthophyll Pigment-Producing Marine Bacterium, Erythrobacter Sp. SDW2 Strain, in Coastal Seawater. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanien, Y.A.; Nassrallah, A.A.; Zaki, A.G.; Abdelaziz, G. Optimization, Purification, and Structure Elucidation of Anthraquinone Pigment Derivative from Talaromyces Purpureogenus as a Novel Promising Antioxidant, Anticancer, and Kidney Radio-Imaging Agent. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 356, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiffary, M.R.; Prabowo, C.P.S.; Sharma, K.; Yan, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, H.U. High-Level Production of the Natural Blue Pigment Indigoidine from Metabolically Engineered Corynebacterium Glutamicum for Sustainable Fabric Dyes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 6613–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Ma, L.; Qin, X.; Zhu, H.; Chen, G.; Liang, Z.; Zeng, W. Efficient Production of Melanin by Aureobasidium Melanogenum Using a Simplified Medium and pH-Controlled Fermentation Strategy with the Cell Morphology Analysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsouko, E.; Tolia, E.; Sarris, D. Microbial Melanin: Renewable Feedstock and Emerging Applications in Food-Related Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owary, J. MICROBIAL COLOURANTS IN FOOD INDUSTRY: A NEW DIMENSION. In; 2022; Vol. 1, pp. 47–55.

- Elkhateeb, W.; Daba, G. Fungal Pigments: Their Diversity, Chemistry, Food and Non-Food Applications. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboyibor, C.; Kong, W.-B.; Chen, D.; Zhang, A.-M.; Niu, S.-Q. Monascus Pigments Production, Composition, Bioactivity and Its Application: A Review. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srilekha, V.; Krishna, G.; Sreelatha, B.; Jagadeesh Kumar, E.; Rajeshwari, K.V.N. Prodigiosin: A Fascinating and the Most Versatile Bioactive Pigment with Diverse Applications. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darshan, N.; Manonmani, H.K. Prodigiosin and Its Potential Applications. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 5393–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Ferreira, V.; Sant’Anna, C. Impact of Culture Conditions on the Chlorophyll Content of Microalgae for Biotechnological Applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob-Lopes, E.; Maroneze, M.M.; Deprá, M.C.; Sartori, R.B.; Dias, R.R.; Zepka, L.Q. Bioactive Food Compounds from Microalgae: An Innovative Framework on Industrial Biorefineries. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, I.; Cadier, E.; Beulens, J.W.J.; Van Der A, D.L.; Spijkerman, A.M.W.; Van Der Schouw, Y.T. Dietary Intake of Carotenoids and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, B.; Mou, H.; Chen, F.; Yang, S. Microalgae-Derived Pigments for the Food Industry. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraj, C.; Ugamoorthi, R.; Ramarethinam, S. Isolation of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa for Bacterial Pigment Production and Its Application on Synthetic Knitted Fabric. Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research 2021, 46, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García, F.; Klein, V.J.; Brito, L.F.; Brautaset, T. From Brown Seaweed to a Sustainable Microbial Feedstock for the Production of Riboflavin. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 863690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, R.; Li, R.; Wang, C.; Ban, R. Production of Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) by Bacillus subtilis J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molelekoa, T.B.J.; Augustyn, W.; Regnier, T.; Da Silva, L.S. Chemical Characterization and Toxicity Evaluation of Fungal Pigments for Potential Application in Food, Phamarceutical and Agricultural Industries. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Suo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Jin, F.; Zhao, H.; Shi, C. Genetic and Virulent Difference Between Pigmented and Non-Pigmented Staphylococcus Aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis-Mansur, M.C.P.P.; Cardoso-Rurr, J.S.; Silva, J.V.M.A.; De Souza, G.R.; Cardoso, V.D.S.; Mansoldo, F.R.P.; Pinheiro, Y.; Schultz, J.; Lopez Balottin, L.B.; Da Silva, A.J.R.; et al. Carotenoids from UV-Resistant Antarctic Microbacterium sp. LEMMJ01. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankari, M.; Rao, P.R.; Hemachandran, H.; Pullela, P.K.; Doss C, G.P.; Tayubi, I.A.; Subramanian, B.; Gothandam, K.; Singh, P.; Ramamoorthy, S. Prospects and Progress in the Production of Valuable Carotenoids: Insights from Metabolic Engineering, Synthetic Biology, and Computational Approaches. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 266, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as Natural Functional Pigments. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.-H.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, J.-G. Carotenoids Biosynthesis and Cleavage Related Genes from Bacteria to Plants. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2314–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumskaya, M.; Wurtzel, E.T. The Carotenoid Biosynthetic Pathway: Thinking in All Dimensions. Plant Sci. 2013, 208, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Gómez, L.C.; Montañez, J.C.; Méndez-Zavala, A.; Aguilar, C.N. Biotechnological Production of Carotenoids by Yeasts: An Overview. Microb. Cell Factories 2014, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meddeb-Mouelhi, F.; Moisan, J.K.; Bergeron, J.; Daoust, B.; Beauregard, M. Structural Characterization of a Novel Antioxidant Pigment Produced by a Photochromogenic Microbacterium Oxydans Strain. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 180, 1286–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghilardi, C.; Sanmartin Negrete, P.; Carelli, A.A.; Borroni, V. Evaluation of Olive Mill Waste as Substrate for Carotenoid Production by Rhodotorula Mucilaginosa. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2020, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussagy, C.U.; Gonzalez-Miquel, M.; Santos-Ebinuma, V.C.; Pereira, J.F.B. Microbial Torularhodin – a Comprehensive Review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2023, 43, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoz, L.; Carvalho, J.C.; Soccol, V.T.; Casagrande, T.C.; Cardoso, L. Torularhodin and Torulene: Bioproduction, Properties and Prospective Applications in Food and Cosmetics - a Review. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2015, 58, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asker, D.; Awad, T.S.; Beppu, T.; Ueda, K. Isolation, Characterization, and Diversity of Novel Radiotolerant Carotenoid-Producing Bacteria. In Microbial Carotenoids from Bacteria and Microalgae; Barredo, J.-L., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2012; Vol. 892, pp. 21–60. ISBN 978-1-61779-878-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nupur, L.N.U.; Vats, A.; Dhanda, S.K.; Raghava, G.P.S.; Pinnaka, A.K.; Kumar, A. ProCarDB: A Database of Bacterial Carotenoids. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabani, P.; Singh, O.V. Radiation-Resistant Extremophiles and Their Potential in Biotechnology and Therapeutics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, A.Y.; Alnaeeli, M.; Park, J.K. Production Control and Characterization of Antibacterial Carotenoids from the Yeast Rhodotorula Mucilaginosa AY-01. Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, C.A.; Sibirny, A.A. Genetic Control of Biosynthesis and Transport of Riboflavin and Flavin Nucleotides and Construction of Robust Biotechnological Producers. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 321–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hu, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, T. Production of Riboflavin and Related Cofactors by Biotechnological Processes. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher, A.; Eberhardt, S.; Fischer, M.; Kis, K.; Richter, G. Biosynthesis of Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin). Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2000, 20, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philmus, B.; Decamps, L.; Berteau, O.; Begley, T.P. Biosynthetic Versatility and Coordinated Action of 5′-Deoxyadenosyl Radicals in Deazaflavin Biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5406–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battersby, A.R. Tetrapyrroles: The Pigments of Life. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2000, 17, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptaszek, M. Rational Design of Fluorophores for in Vivo Applications. In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science; Elsevier Inc., 2013; Vol. 113, pp. 59–108 ISBN 9780123869326.

- Shepherd, M.; Medlock, A.E.; Dailey, H.A. Porphyrin Metabolism. In Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry; Elsevier, 2013; Vol. 3, pp. 544–549 ISBN 9780123786319.

- Kang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qi, Q. Metabolic Engineering to Improve 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Production. Bioeng. Bugs 2011, 2, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hörtensteiner, S. Chlorophyll Degradation during Senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Schliep, M.; Willows, R.D.; Cai, Z.-L.; Neilan, B.A.; Scheer, H. A Red-Shifted Chlorophyll. Science 2010, 329, 1318–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, H. An Overview of Chlorophylls and Bacteriochlorophylls: Biochemistry, Biophysics, Functions and Applications. In Chlorophylls and Bacteriochlorophylls; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2007; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, M.O.; Smith, K.M. Biosynthesis and Structures of the Bacteriochlorophylls. In Anoxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, 2006; pp. 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Su, H.-N.; Pu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.-N.; Liu, Q.; Qin, S. Phycobiliproteins: Molecular Structure, Production, Applications, and Prospects. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manirafasha, E.; Ndikubwimana, T.; Zeng, X.; Lu, Y.; Jing, K. Phycobiliprotein: Potential Microalgae Derived Pharmaceutical and Biological Reagent. Biochem. Eng. J. 2016, 109, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, A.R.; Schaefer, M.R.; Chiang, G.G.; Collier, J.L. The Phycobilisome, a Light-Harvesting Complex Responsive to Environmental Conditions. Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 57, 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, L.; Ben Hlima, H.; Hentati, F.; Hentati, O.; Derbel, H.; Michaud, P.; Abdelkafi, S. Microalgae: A Promising Source of Bioactive Phycobiliproteins. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadnichuk, I.N.; Krasilnikov, P.M.; Zlenko, D. V. Cyanobacterial Phycobilisomes and Phycobiliproteins. Microbiology 2015, 84, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.-A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Williams, P.G.; Lindsey, J.S.; Miller, E.S. Genome Sequence and Composition of a Tolyporphin-Producing Cyanobacterium-Microbial Community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01068–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, N.R.; Fineran, P.C.; Leeper, F.J.; Salmond, G.P.C. The Biosynthesis and Regulation of Bacterial Prodiginines. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, M.; Irace, C.; Costagliola, F.; Castelluccio, F.; Villani, G.; Calado, G.; Padula, V.; Cimino, G.; Lucas Cervera, J.; Santamaria, R.; et al. A New Cytotoxic Tambjamine Alkaloid from the Azorean Nudibranch Tambja Ceutae. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 2668–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picott, K.J.; Deichert, J.A.; DeKemp, E.M.; Snieckus, V.; Ross, A.C. Purification and Kinetic Characterization of the Essential Condensation Enzymes Involved in Prodiginine and Tambjamine Biosynthesis. Chembiochem Eur. J. Chem. Biol. 2020, 21, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai-Kawada, F.E.; Ip, C.G.; Hagiwara, K.A.; Awaya, J.D. Biosynthesis and Bioactivity of Prodiginine Analogs in Marine Bacteria, Pseudoalteromonas: A Mini Review. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, N.R.; Chawrai, S.; Leeper, F.J.; Salmond, G.P.C. Prodiginines and Their Potential Utility as Proapoptotic Anticancer Agents. In Emerging Cancer Therapy; Wiley, 2010; pp. 333–366 ISBN 9780470444672.

- Kurbanoglu, E.B.; Ozdal, M.; Ozdal, O.G.; Algur, O.F. Enhanced Production of Prodigiosin by Serratia Marcescens MO-1 Using Ram Horn Peptone. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2015, 46, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islan, G.A.; Rodenak-Kladniew, B.; Noacco, N.; Duran, N.; Castro, G.R. Prodigiosin: A Promising Biomolecule with Many Potential Biomedical Applications. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 14227–14258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, F. Melanins: Skin Pigments and Much More—Types, Structural Models, Biological Functions, and Formation Routes. New J. Sci. 2014, 2014, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, E.S. Pathogenic Roles for Fungal Melanins. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glagoleva, A.Y.; Shoeva, O.Y.; Khlestkina, E.K. Melanin Pigment in Plants: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narsing Rao, M.P.; Xiao, M.; Li, W.-J. Fungal and Bacterial Pigments: Secondary Metabolites with Wide Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavan, M.E.; López, N.I.; Pettinari, M.J. Melanin Biosynthesis in Bacteria, Regulation and Production Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]