1. Introduction

As far as we currently know, water is essential for life, particularly in its liquid state that allows dynamics to take place [

1]. Indeed, hydrogen-bonds (HBs) in liquid water form and break on the single ps timescale. Consequently, “the presence of highly structured interfacial water correlated to specific functional states of proteins

… surprised the community” [

2]. As an example, Ref. [

2] discusses the X-ray diffraction from the snow flea Anti-Freeze Protein (sfAFP). Although crystallized at

room-temperature, it exhibited “an array of highly ordered water molecules on the flat, hydrophobic face of the protein” [

3]. While the family of antifreeze proteins, essential for life at subzero temperatures, is diverse, the sfAFP has no known homologues. Its structure is based on a GXY repeat unit, where G = Gly (glycine), and X is often another Gly. Occasionally, X = Cys (cystein), leading to intramolecular SS bonds.

Interestingly, collagens also have GXY as their repeat units, though here X and Y are often the imino acids P = Pro (proline) or O = Hyp (hydroxyproline), so that Pro-Hyp-Gly (i.e., POG) is the most common triplet in collagen [

4,

5]. While this ends the formal similarity between the two proteins, we will show below, using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, that a collagen mimetic peptide (CMP) based on the PPG repeat unit also possesses highly ordered interfacial water molecules (WMs)

at ambient temperature, with conjectured functional consequences.

Collagen is the most abundant structural protein in vertebrates, dominant in the extracellular matrix (ECM), and estimated to account for around 30 percent of the total protein weight in the human body. There are 28 known collagen families, among which collagens I, II, III, V, and XI are dominant and found in bones, tendons, cartilage, skin, blood vessels and more [

4]. As mentioned above, each collagen polypeptide chain has the

(or, equivalently,

) structure, folding into a left-handed helix. Three staggered polypeptide chains then combine to form a right-handed triple-helix,

, with 7/2 or 10/3 helical symmetry (3.5 or 3.33 residues per turn, respectively) [

6,

7,

8]. The three chains are linked together by strong HBs between the glycine’s NH group and the CO group at the X position of an adjacent chain, G-NH

…OC-X. There is only this one direct HB between adjacent chains per triplet. When X and Y are imino acids then, due to their proline ring, there is no H atom bonded to their backbone (bb) N atom. When X and Y are amino acids, their NH group points outward from the triple helix axis. However, a X-NH...OH

...OC-G single water bridge can then form [

9]. Weaker CH…OC HBs, emanating from an

-carbon, e.g. G-CH

…OC-X, also contribute to the triple helix stability [

10].

Biological collagen samples, such as a tendon, consist of a hierarchy of collagen molecules, in which triple helices assemble into microfibrils, which assemble into fibrils and finally cross-linked fibers [

4]. These are difficult to disentangle and crystallize, so that only low-resolution X-ray structures are available for natural collagen samples [

11]. To circumvent this complexity, various CMPs were synthesized and crystallized. The simplest are the (PPG)

peptides, (n = 9 or 10), whose X-ray structures (commonly at 100 K) have been determined several times [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], see Protein Data Bank (PDB) structures 1K6F, 1A3I, 1A3J, 2CUO, 1ITT, 3AH9. These have higher resolutions than the earlier biological collagen samples, revealing not only the details of the triple helix, but also individual WMs at the peptide-water interface.

Unlike an earlier NMR study suggesting that an ordered “water wire” exists parallel to the collagen main axis [

19], other ordered arrangements of water were revealed by the peptide diffraction studies [

20,

21]:

- (a)

The bb-carbonyl oxygen atoms of the G, X and Y residues accepts HBs from 1, 0 and 2 WMs, respectively. Clearly, X-CO is not hydrated because it is the HB acceptor in the direct G-NH…OC-X HB.

- (b)

In (PPG)

X-ray structures [

13,

14], bb-carbonyls from Gly and Pro(Y) are connected intramolecularly by a 1-water bridge, and intermolecularly by a 3-water bridge.

- (c)

When an amino acid is present in the X or Y positions, or Hyp in Y, their NH or OH moieties (respectively) serve as anchor points for additional water bridges.

Water bridges fascinated the collagen X-ray community, because they were envisioned as stabilizing the collagen structure [

5,

21,

22,

23]. These chains were “immobilized relative to bulk water and aligned in the plane transverse to the axis of the molecule”, thus explaining the “tendon magic angle effect” seen in magnetic resonance imaging [

24]. This “ice-like” behavior must persist at least into the msec time-regime to be observed in T2 NMR measurements [

25]. Only one work casted doubts on the water bridge explanation for collagen stability [

26].

The question is to what extent structures observed in crystals at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., 100 K) are relevant to room-temperature liquid water? Clearly, water hexagons and cubes are seen in ices, which does not mean they characterize liquid water. Moreover, in liquid water the protein is surrounded by many more WMs as compared with its X-ray structure, and these could create networks that branch in all directions, obscuring any putative linear water chain. Such questions can be readily addressed by MD simulations, a field benefiting from constant improvement in force fields and analysis tools.

Indeed, several MD simulations of collagen-like peptides were conducted in search of stable water bridges [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. For concreteness, consider the last study on the list, by Madhavi et al. [

33], which is the most recent and detailed. It considered a triple helix composed of 30-residue peptide chains (PDB file 1BKV [

34]), in which the first 3 and last 4 triplets are (POG)

and (POG)

, respectively. [The central portion of this peptide contains (non-imino) amino acids, and is less relevant for the present study.] They have analyzed all single-water bridges, which in the imino-rich segments can be only of the intramolecular G-CO

…HOH

…OC-Y type. With a cutoff of 2.4 Å for the OH

…O HB distance, this bridge was found in only 1.2 % of the 10 ns MD frames at 310 K (quite in contrast to an earlier study [

35]). Thus, longer bridges (not monitored) may be even less probable. We conclude that water bridges are insignificant for the (PPG)

peptide at room temperature.

In contrast, first shell hydration (involving the bb-carbonyl oxygen atoms) is significant. As mentioned above, the X-ray studies indicated 0-2-1 hydration for the X-Y-G triplet at 100 K. Adding the single-water and (twice the) double-water hydration probabilities at 310 K from Tbl. 6 of Madhavi et al. gives hydration numbers of <0.01, 1.26 and 0.99, respectively. While this resembles qualitatively the X-ray results, the MD study reported only the average over all imino-rich sites. Moreover, the (continuous) residence times of water hydrogen atoms at the Y-CO and G-CO sites were found to be only 0.84 and 4 ps, respectively. These numbers are similar to (or shorter than) those of bulk liquid water, giving no hint for an “ice-like” behavior.

Nevertheless, there are several arguments suggesting that these residence times should be longer:

- (a)

The PPG segments are short, and located at the two ends of the 1BKV peptide, where the triple helix is less compact and more exposed to solution.

- (b)

The zwitterionic peptide was not “capped” to better mimic infinitely long chains.

- (c)

The 10 ns simulations are not sufficiently long to obtain the residence time distribution (only its average).

- (d)

The average residence time was measured for a water H atom, rather than its O atom. This monitors water reorientation times, which terminate with a flip exchanging the two H atoms of a WM, rather than the O atom leaving its binding location. Consequently, the study is best repeated for an intact (PPG) peptide.

The present work analyses classical MD trajectories for the [(PPG))] collagen-like peptide, determining the structure of its hydration layers. We show that in spite of the rapid water dynamics, the first hydration layer is as ordered as in the crystal state, with periodic 0-1.7-1 hydration for all X-Y-G triplets. Similar periodic behavior is calculated for the solvent accessible surface area (SASA). The average continuous residence times for a WM in the G-CO and Y-CO sites are about 82 and 26 ps, respectively, indicating that water exchange between the first hydration shell and the bulk is actually much slower than in pure water. Finally, we briefly discuss the implications of these results.

2. Materials and Methods

In collagen model peptides, X-ray crystallography has provided high-resolution structures of the basic triple-helical conformation and its water-mediated hydration network [

14,

17,

18]. In this study, the crystal structure of the CMP [(PPG)

)]

, available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 1K6F), was used for the MD simulations [

16]. It was chemically synthesized, and its X-ray diffraction was taken at 1.30 Å resolution [

16]. This peptide system has been extensively studied for properties such as stability and solvation of collagen protein [

30,

36,

37]. The unit cell consisted of two head-to-tail triple helices, of which we focused on one (chains A, B and C).

The two termini of the tripeptide are oppositely charged (the N-terminal positive and C-terminal negative). Consequently, they showed unusual interaction with solvent molecules during the simulation, including partial unwinding. Hence, we capped the two ends with N-terminal acetyl and C-terminal N-Me amide to neutralize their respective terminals by using Amber Tools [

38], performing the MD under both the capped and uncapped conditions.

The choice of the force-field (FF) for the protein and its water solvent significantly impacts MD simulation results. Here we utilize the AMBER14SB FF for the protein [

39], in comparison with the CHARMM36m FF [

40] (Figure S6). For explicit water model, we use the TIP4P/2005, which reproduces accurately the water density, enthalpy of vaporization, and oxygen-oxygen radial distribution function at room temperature [

41]. As the water model may be crucial for hydration properties, we compare the results with those from the TIP3P models (Figures S5, S9 and S12).

All simulations were conducted using the GROMACS MD software, version 2020.2 [

42], at two different temperature 300 or 250 K. The 168 crystal WMs in the X-ray structure were either deleted or retained, which appeared to have little effect on the equilibrated structure of the hydration layers because the water ligands are readily exchanged with the bulk [

43,

44,

45]. To run the simulation, we have considered different simulation boxes containing between 12,000 and 62,306 WMs with appropriate density. A triclinic box was used to define the systems’ boundaries because of the peptide’s cylindrical shape [

46]. The protein was separated by at least 10 Å from the box boundaries in all directions. Periodic boundary conditions were imposed, with particle mesh Ewald (PME) summation to evaluate the long-range Coulombic interactions [

47].

The subsequent equilibration phase comprised of three steps. First, energy minimization was performed, followed by 1 ns equilibration in the NVT ensemble (constant volume, temperature, and number of particles) and finally 1 ns equilibration in the NPT ensemble (constant pressure, temperature, and number of particles), using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat at 1 atm [

48]. The production run then followed, with a 100 ns long NPT trajectory. The fastest time modes were eliminated by restricting the motion of the hydrogen atoms using the Linear Constraint Solver (LINCS) algorithm [

49]. This allowed for a relatively large timestep of 2 fs, enabling us to reach a longer production time, 100 ns (0.5

timesteps). Such long times were needed for proper averaging over protein modes. The trajectorys’ coordinates were saved every 1 to 10 ps. These are the data passed over to the analysis phase.

Trajectory processing was performed using the Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) package [

50], along with our own Tcl scripts (collected in the Supplementary Documents). We determine the water structure in the hydration shells by calculating the radial distribution function (RDF) denoted by

, and its integral, as implemented in VMD. Alternately, we have determined the average hydration numbers in both first and second solvation shells of the Res-CO oxygen atoms (where Res = Gly or Pro) from Tcl script S1.

The hydration pattern is explained, in part, from the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) around the Res-CO oxygen, calculated from our Tcl script S2.

Additionally, we analyzed the residence time distribution of water near Res-CO, using our Tcl script S3, to show that it extends to longer times than in liquid water, but much shorter than in ice. Thus, the high order of the hydration layer is not due to “ice like” structures. Rather, the average radius of gyration, (Tcl script S6), pointing to cylinder-like symmetry, could be the origin of the highly ordered triple helix in the liquid state.

3. Results

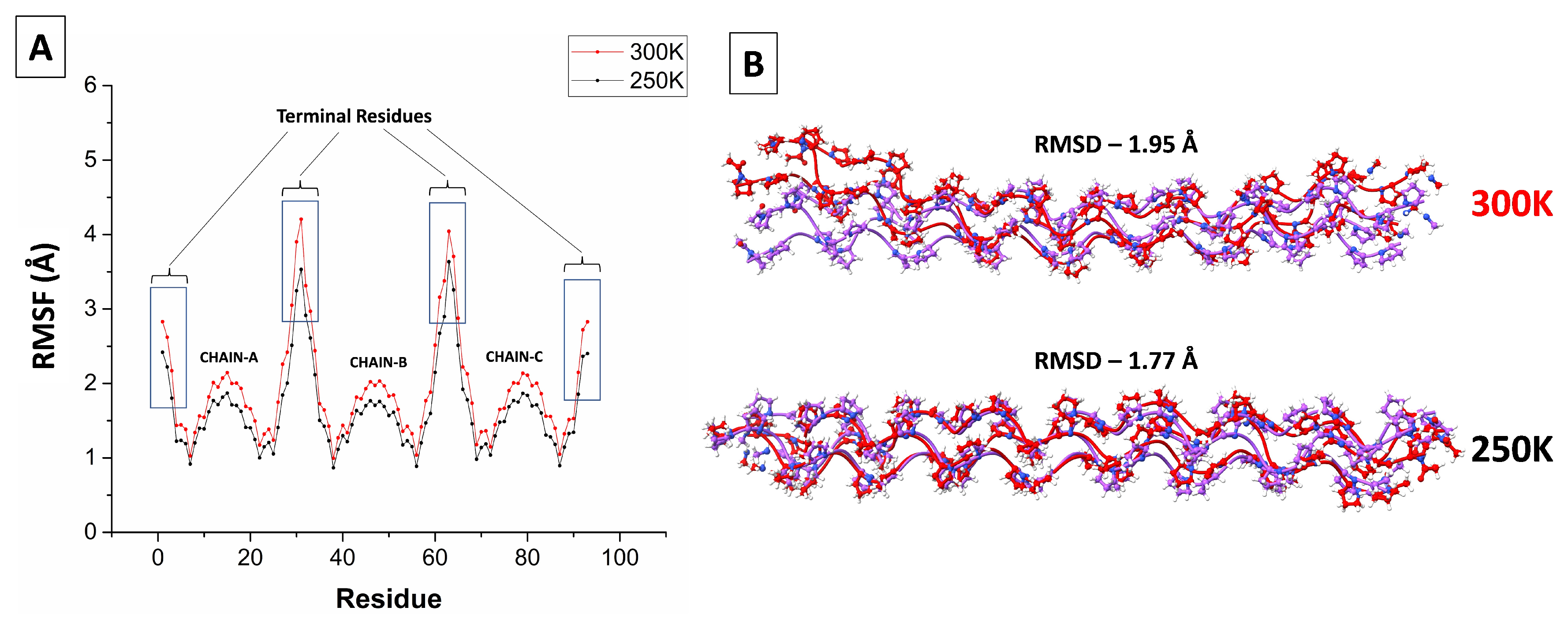

3.1. Stability and Fluctuations

A common check on the equilibration of a protein in MD simulations is obtained by monitoring the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of its backbone atoms from their initial positions as a function of simulation time. As Figure S1 shows, the RMSD of the [(PPG)

]

peptide is essentially time-independent on the ns timescale, indicative of rapid equilibration on the simulation timescale. Comparison of the RMSD at 250 and 300 K in Figure S1 shows only little temperature dependence, suggesting that the peptide is stable in spite of its short length. Indeed, for a collagen-like peptide with more variable amino-acid triplets (

Figure 5 in Ref. [

51]) the calculated RMSD at 300 K was about 4 Å, whereas here it is only 2 Å (Table S1). Thus, the homogeneous composition of the

peptide results in a very stable and ordered structure. The root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of the C-alpha atom in each residue is depicted in

Figure 1A. It reveals large fluctuations only at the terminal residues, where the triple helix may partly unwind. This is seen particularly at the higher temperature (300 K) in

Figure 1B. However, two to three residues from the chain’s end the RMSF decreases to nearly 1 Å. It then increases back to ca. 2 Å towards the middle of the chain, perhaps due to the bending mode of the triple helix. A similar behavior has been observed in

Figure 6 of Ref. [

51].

3.2. Radius of Gyration

The radius of gyration (

), averaged over all frames in a trajectory, is often compared with the end-to-end distance (

), as both are measures for the spatial extent of a protein. Roughly speaking,

is the distance from the center of the peptide to one of its ends, so it may be expected to be close to

. However, for linear polymers generally

. For example, in an “ideal chain”,

(see Equation (12) in Ref. [

52], p. 16–17 in Ref. [

53]).

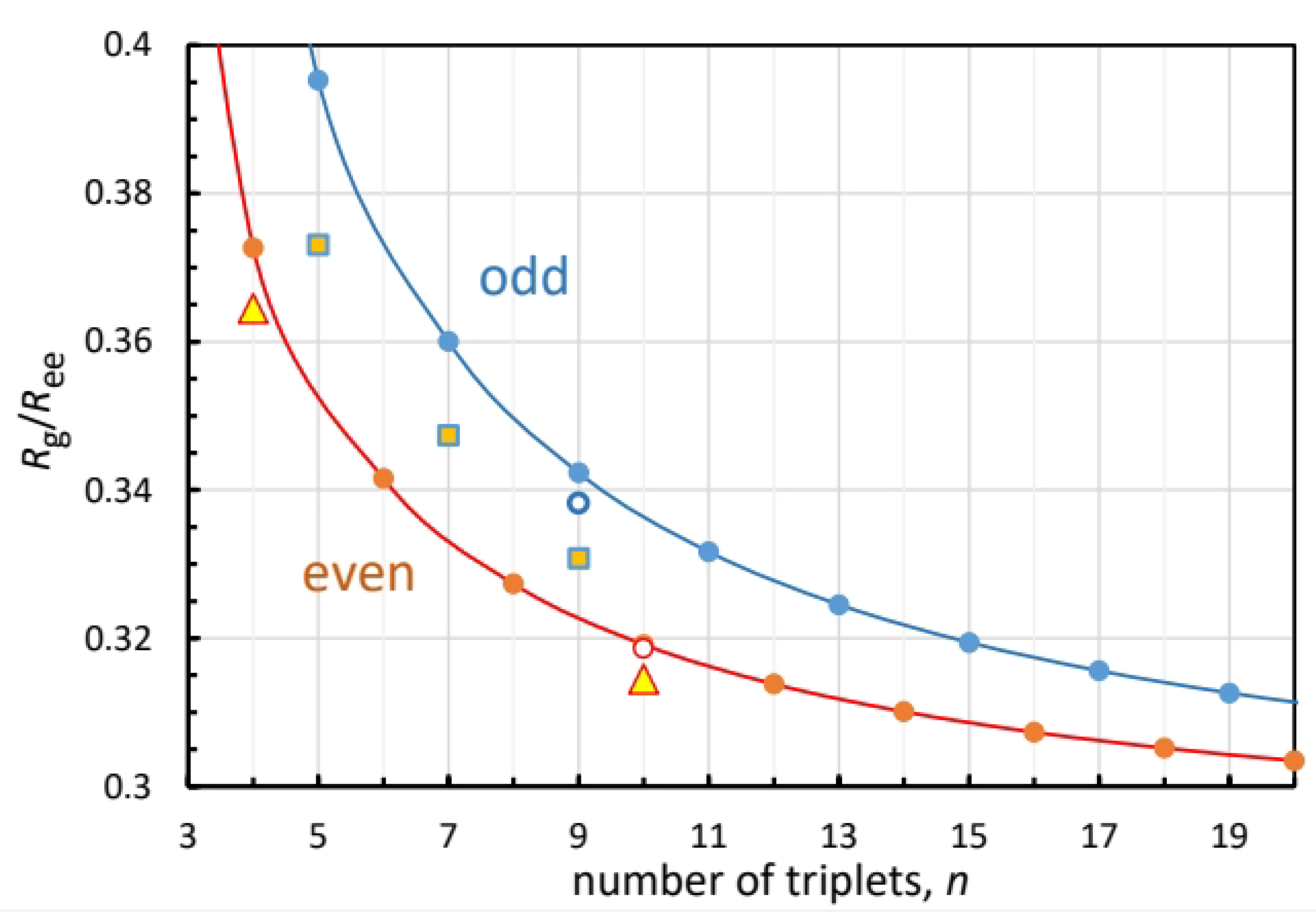

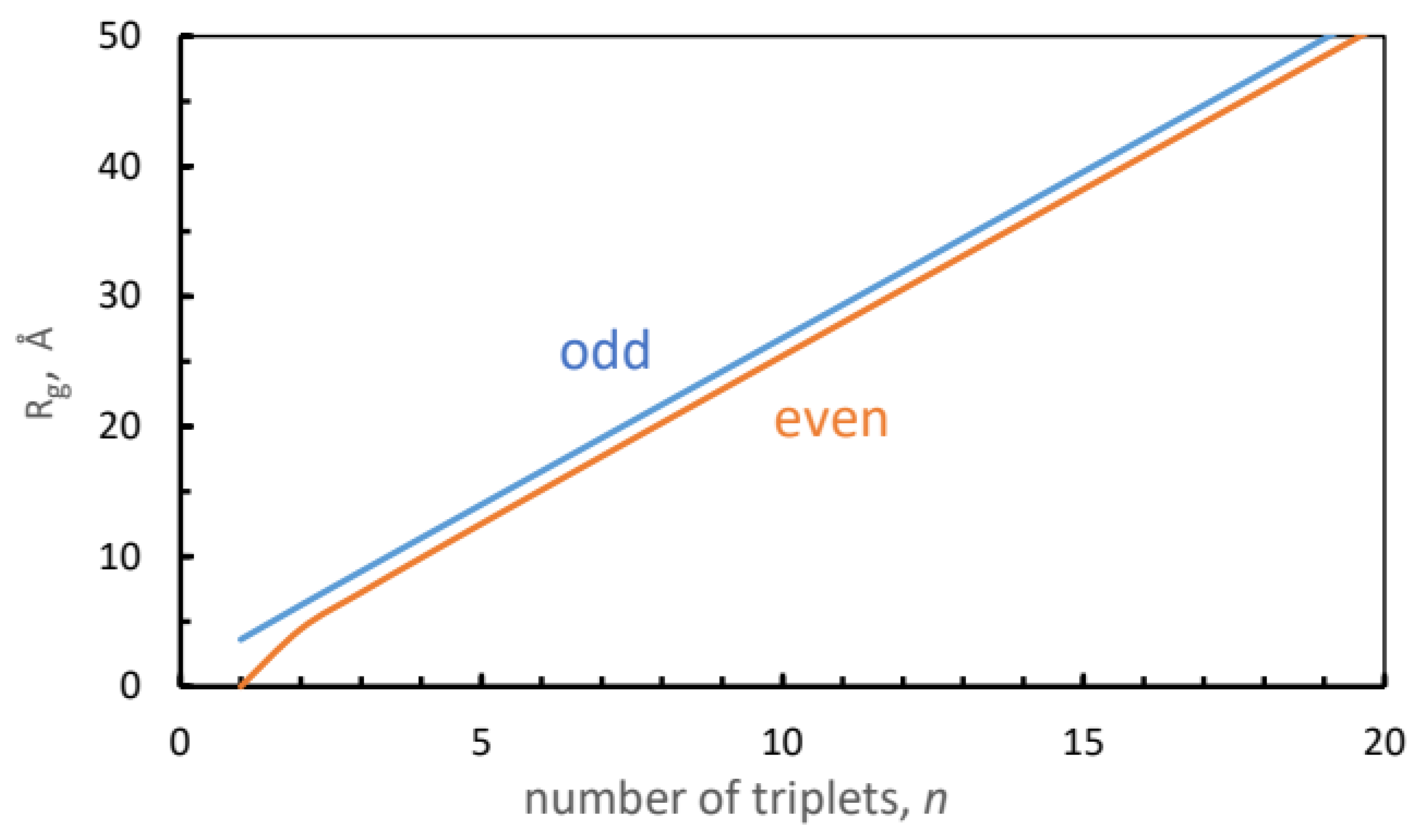

Here we calculate for a linear chain such as , as a function of the number of PPG triplets, n. For this aim, we have simulated four additional (capped) peptides, obtaining , 5, 7, 9 and 10, each at 250 and 300 K. These numerical results are subsequently compared with a simple analytical theory that, amusingly, suggests different n-dependencies for even and odd n.

The squared radius of gyration,

was calculated for all the

N atoms of the peptide, having masses

and distances

from the center of mass (CM), and averaged over all 10000 frames of each trajectory. Results for the five peptides at the two temperatures are collected in

Table 1.The values of

from experimental X-ray structures for

and 10 (at about 100 K) are in excellent agreement with our simulated values, even mimicking the slight decrease in

with decreasing

T that is seen here. This indicates that a linear model is indeed very suitable for the (PPG)

peptides. In comparison to

Å for (PPG)

, the

experimental value for the (POG)

peptide (using X-ray solution scattering) is only 23 Å, suggesting that a linear model is less suitable in this case [

54].

Table S2 summarizes our simulated values, measured between the two terminal -carbons, for each chain of the peptides (, 5, 7, 9, and 10) at 250 and 300 K.

Averaging, further, over the three chains at 300 K, yields the values in

Table 2. In comparison to a

simulation that gave an average

Å at 263.5 K [

27], our value for

(at 250 K) is 72.7 Å. However, in comparison to both simulation results, the

from the X-ray structures (for

and 10) are notably smaller (values in parentheses in

Table 2), which contrasts with the high level of agreement between

from X-ray and simulations in

Table 1.

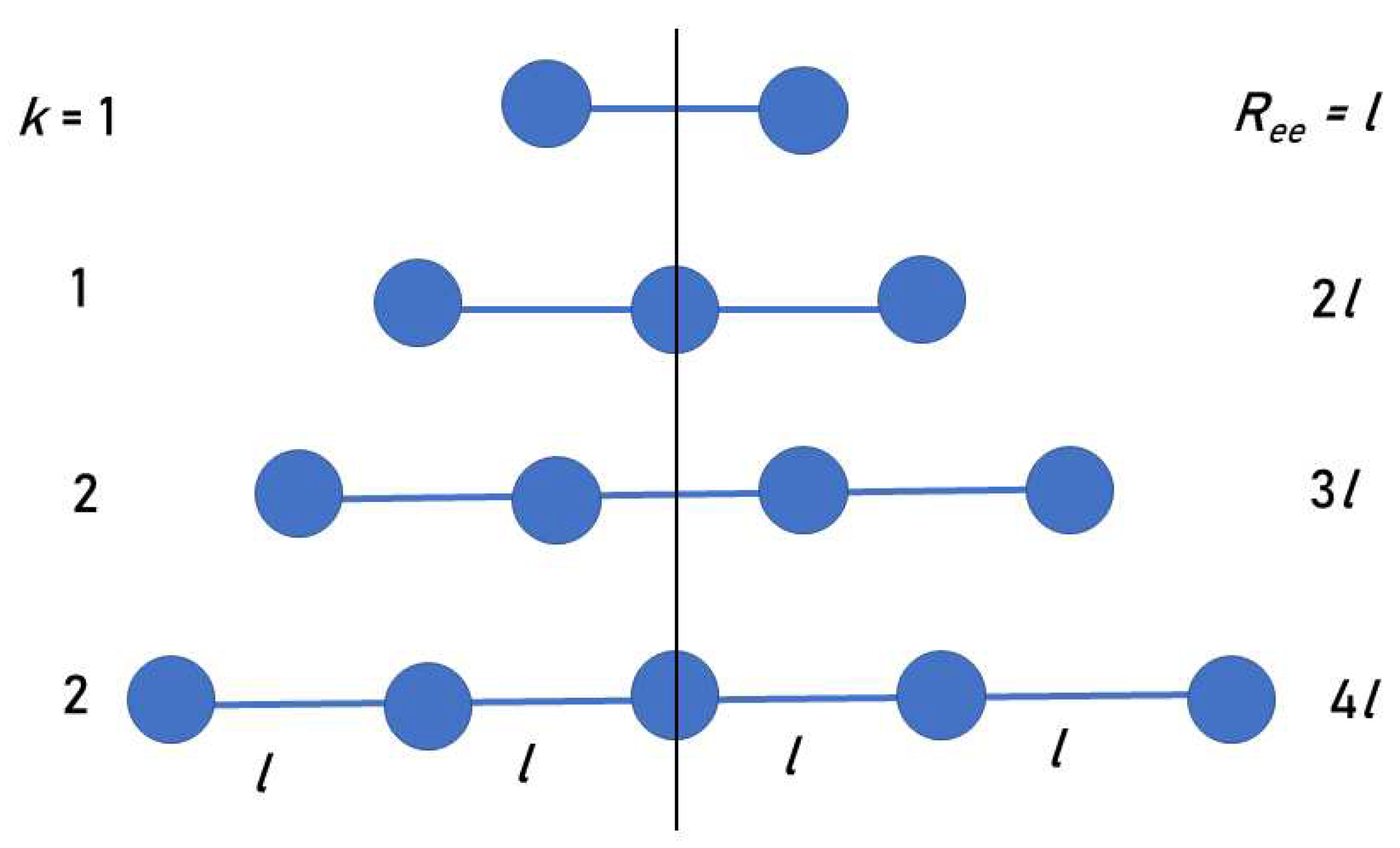

We suggest a simple model that explains the (PPG)

results. The model collagen peptide is composed of mass points representing PPG triplets, arranged along a linear axis, with fixed distances

l between them (

Figure 2). Due to symmetry, it suffices to consider the

k points on just one side of the CM.

Consider first the case of an odd number of triplets,

, when the CM is at the central triplet of the chain. The distances of the triplets from the CM are integer multiples of

l, namely:

, so that

. Let the index

i count these triplets, where

denotes the central triplet at the CM location. Then the averaged radius of gyration over all triplets is defined as

It is well known that the series of squared integers sums analytically

is sometimes called the “square pyramidal number”, because it counts the number of identical balls that can be arranged in the form of a

k-level square pyramid. Therefore, Equation (

1) becomes:

For example, for the peptide , and then , or .

For an even number of triplets,

,

, and the CM is in between the two central triplets (

Figure 2). Therefore, the closest triplets to the CM are a distance

from it. The averaged radius of gyration over all residues is now

obtained by replacing

i by

in Equation (

1). Given that

, one obtains:

For the peptide , and then , or . This is in remarkable agreement with obtained in our simulations.

Figure 3 shows the dependence of

on the number of triplets in the peptide, for the odd and even cases, Equations (

3) and (

5), respectively. Lines were added to guide the eye. The odd curve is always above the even, but at large

k they converge to a common value,

.

The triangles and squares depict the simulation results for the even and odd peptides, respectively. For

and 10 the triangles fall close to theoretical points. The squares depicting

, 7 and 9 fall further below the odd values from Equation (

3). Judging from the experimental crystal data for

and 10 in

Table 2, a main source of error is the disagreement with the simulated

. Replacing it with the experimental

(for

, 10), while keeping the simulated

, produces the open circles

Figure 3, which are in excellent agreement with the model (closed circles).

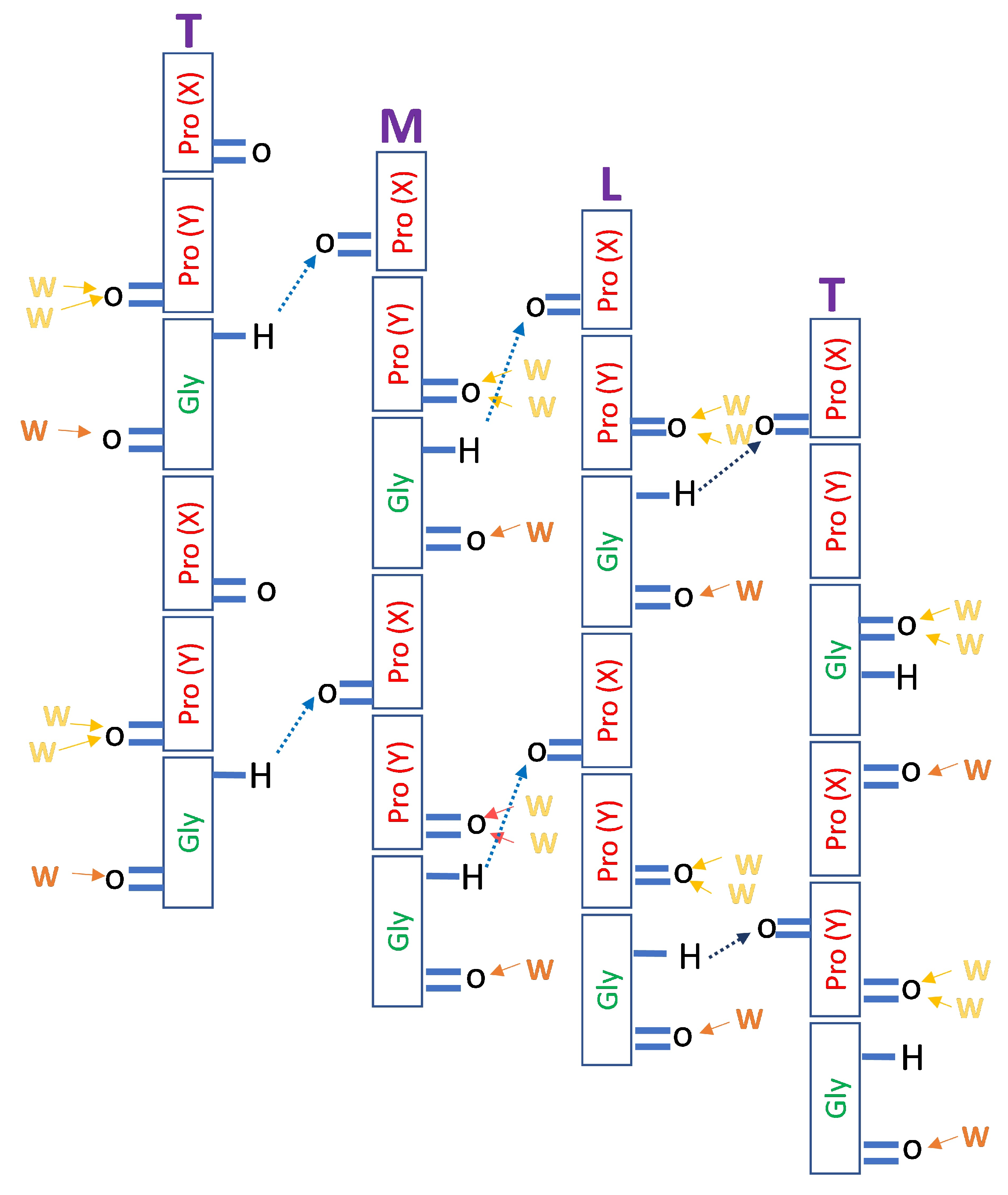

3.3. Characterization of Hydration Sites

In the [(Pro(X)-Pro(Y)-Gly)

]

collagen tripeptide model chain, hydrogen bonds between the main chains are responsible for the triple-helix stability. Early fibre diffraction models already deduced the correct interstrand Gly-NH···OC-Pro(X) connectivity, where the NH group of the Gly residue acts as a HB donor, and the CO group of the residue in the X position of an adjacent strand acts as an acceptor [

13,

21]. Therefore there is exactly one such HB per tripeptide, as depicted schematically in

Figure 4.

There are three bb-carbonyl groups per tripeptide unit, which may potentially serve as binding sites for WMs.

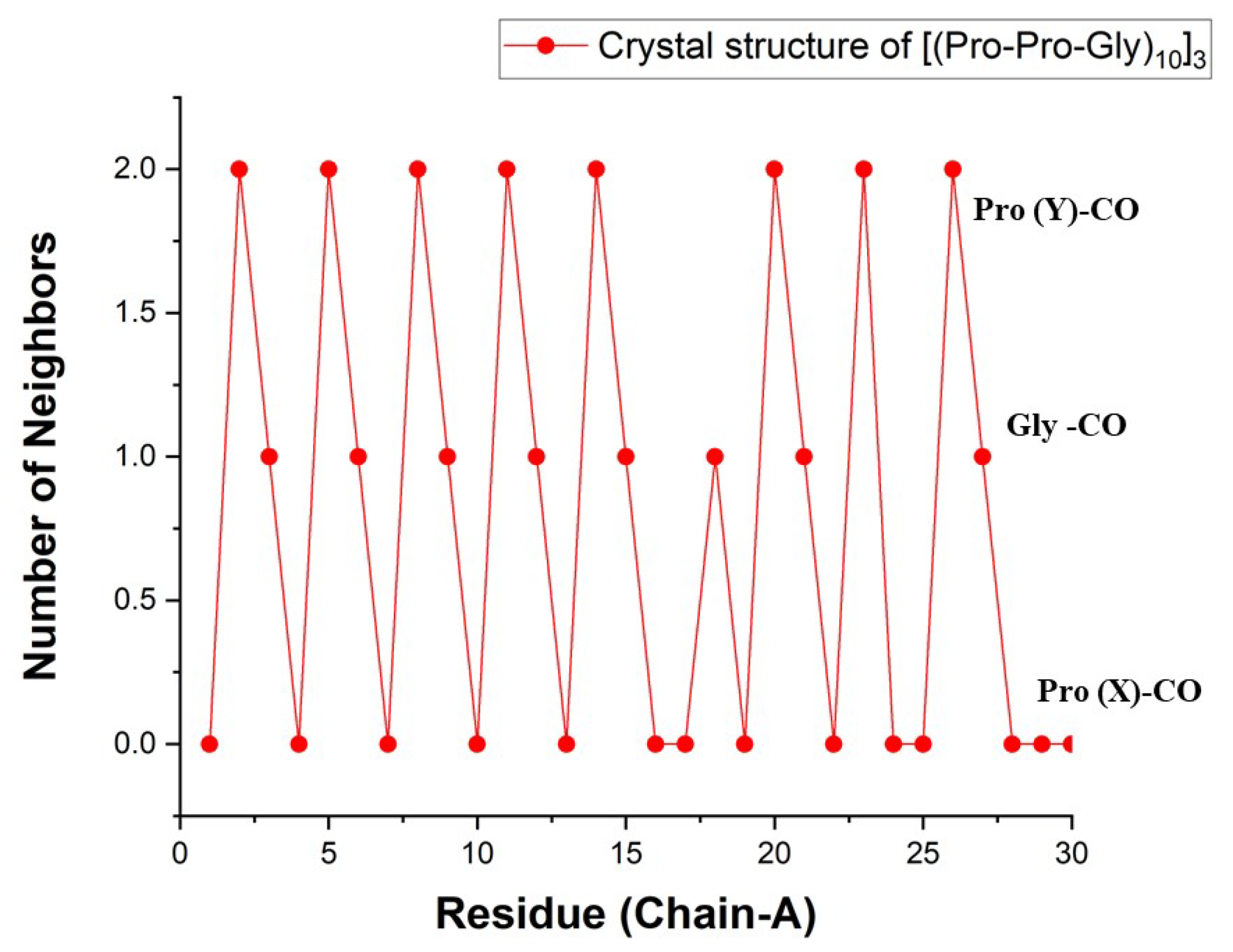

Figure 4 shows the bb-carbonyl solvation in the protein crystal. Pro(X)-CO cannot bind water because it already accepts a HB from Gly-NH in a neighboring chain. While the CO of both Gly and Pro(Y) are available for binding water, they are far from equivalent. Gly-CO accepts a single HB, and Pro(Y)-CO accepts two. To see this, we reproduce in

Figure 5 the number of water ligands as a function of residue number for one of the [(PPG)

]

X-ray structures (PDB file 1K6F). A few WMs are missing due to lattice defects, but otherwise a perfect 0-2-1 hydration pattern emerges [

16,

21]. This structure is also visible in other X-ray structures, such as [(PPG)

]

shown in Figure S3.

Figure 5.

Number of WMs observed in the bb-CO sites of the [(PPG)

]

crystal as a function of residue number. Data from the

chain in PDB file 1K6F [

16] (1.30 Å resolution).

Figure 5.

Number of WMs observed in the bb-CO sites of the [(PPG)

]

crystal as a function of residue number. Data from the

chain in PDB file 1K6F [

16] (1.30 Å resolution).

In the low temperature X-ray structures these and additional first-shell WMs form an intriguing helical pattern around the peptide [

21]. In the present study, we focused exclusively on the carbonyl-oxygen binding sites, asking whether there are remnants for the low-temperature order when the peptide is hydrated in room temperature liquid water?

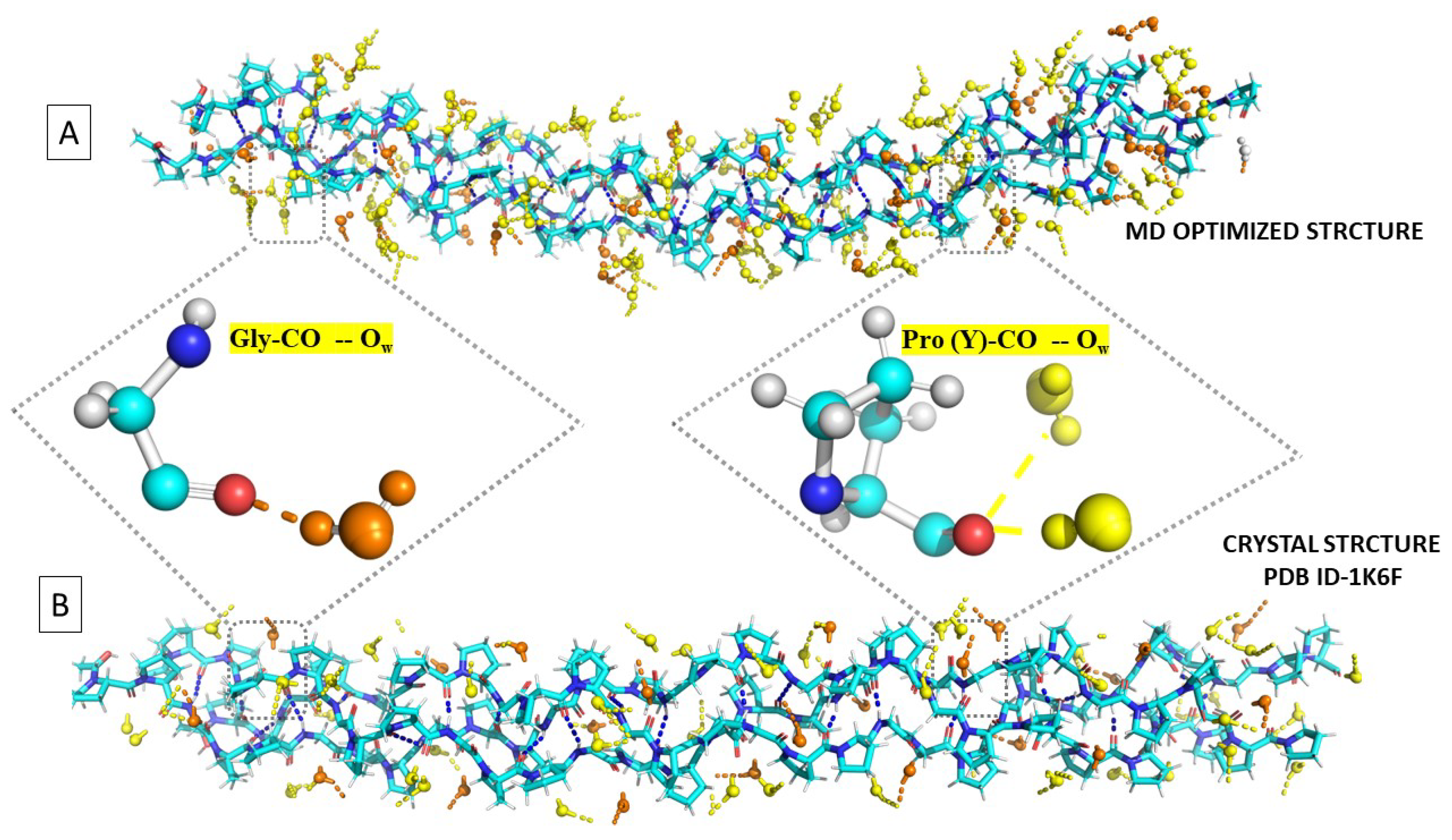

Figure 6 compares a snapshot from our MD simulation at 300 K with the X-ray structure. Both suggest approximately the same 0-2-1 hydration structures, as observed by the X-ray investigators. As this high degree of order seems incompatible with the liquid state, we now apply statistical methods to determine the most probable solution structure.

Figure 6.

Comparison of (A) a snapshot from an MD simulation with (B) the X-ray structure of the [(PPG)] peptide (PDB ID-1K6F).

Figure 6.

Comparison of (A) a snapshot from an MD simulation with (B) the X-ray structure of the [(PPG)] peptide (PDB ID-1K6F).

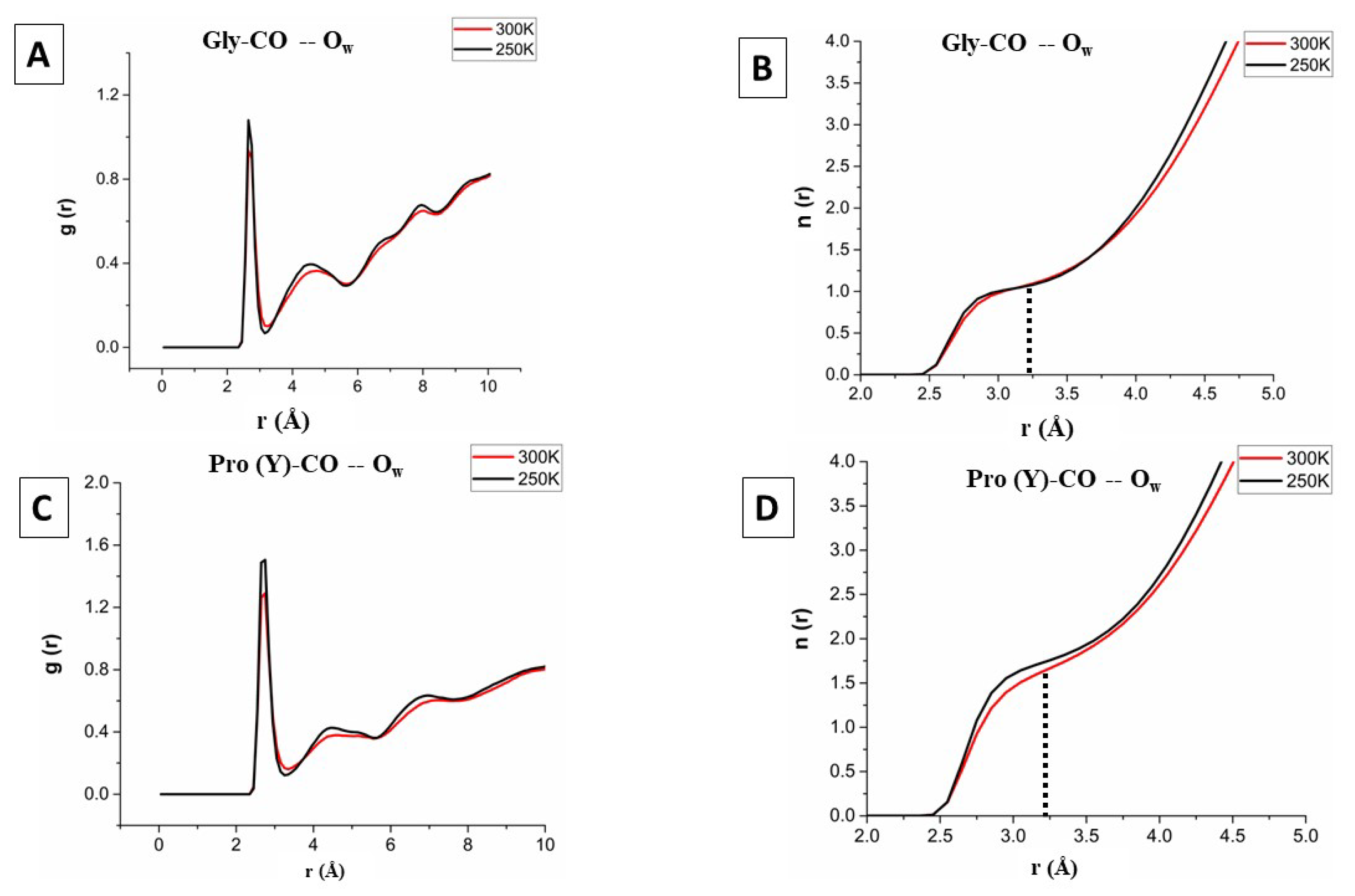

3.3.1. Inner Solvation Shell

The equilibrium water structure at the protein surface can be captured by the radial distribution function (RDF), denoted , which monitors the average number of water oxygen or hydrogen atoms within a spherical shell (between r and ) surrounding selected protein atoms. For the present study, we calculated the RDF of the water-oxygen atom () around the oxygen atom of the bb-carbonyl of each residue of the [(PPG)] peptide, at both 300 and 250 K. The Pro(X) residue did not show any peak for the first hydration layer ( Å), because its carbonyl-oxygen has already made a HB with the Gly-NH of the neighbouring chain, blocking water access. This leaves the Gly-CO and Pro(Y)-CO sites for investigation.

Figure 7A,C show the RDF of

around the glycine and proline(Y) carbonyl-oxygens, respectively. The positions of the first two peaks and two minima in all systems are listed in Table S3. The probability for observing an

atom in the inner hydration layer peaks at the first maximum, which is 2.65 Å in all cases (Gly/Pro(Y) at 250/300 K), extending up to the first minimum, at 3.25 Å This value agrees also with the first minimum of the oxygen-oxygen RDF obtained from bulk water simulations 3.225 Å, as well as with experiment (Figure S4) [

55].

The same from a simulation using the popular TIP3P water model is shown in Figure S5. Clearly, it exhibits weaker undulations, particularly in the second hydration layer, in comparison with the present TIP4P/2005 water model. The weaker undulations are in worse agreement with bulk water experiments, as demonstrated in Figure S4. Figure S6 shows a comparison with from a simulation using the CHARMM36m FF. It, again, exhibits weaker undulations in comparison with the AMBER14SB FF utilized herein. Thus, from the AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005 combination has the most structure, and this may be affecting the hydration numbers reported next.

The indefinite radial integral of

, denoted

, gives the average number of

neighbours up to distance

r. To obtain the hydration numbers for the inner hydration shell, we calculate

at

Å, as demonstrated in

Figure 7B,D. Alternately, the number of neighbors can be calculated from TCl script S1.

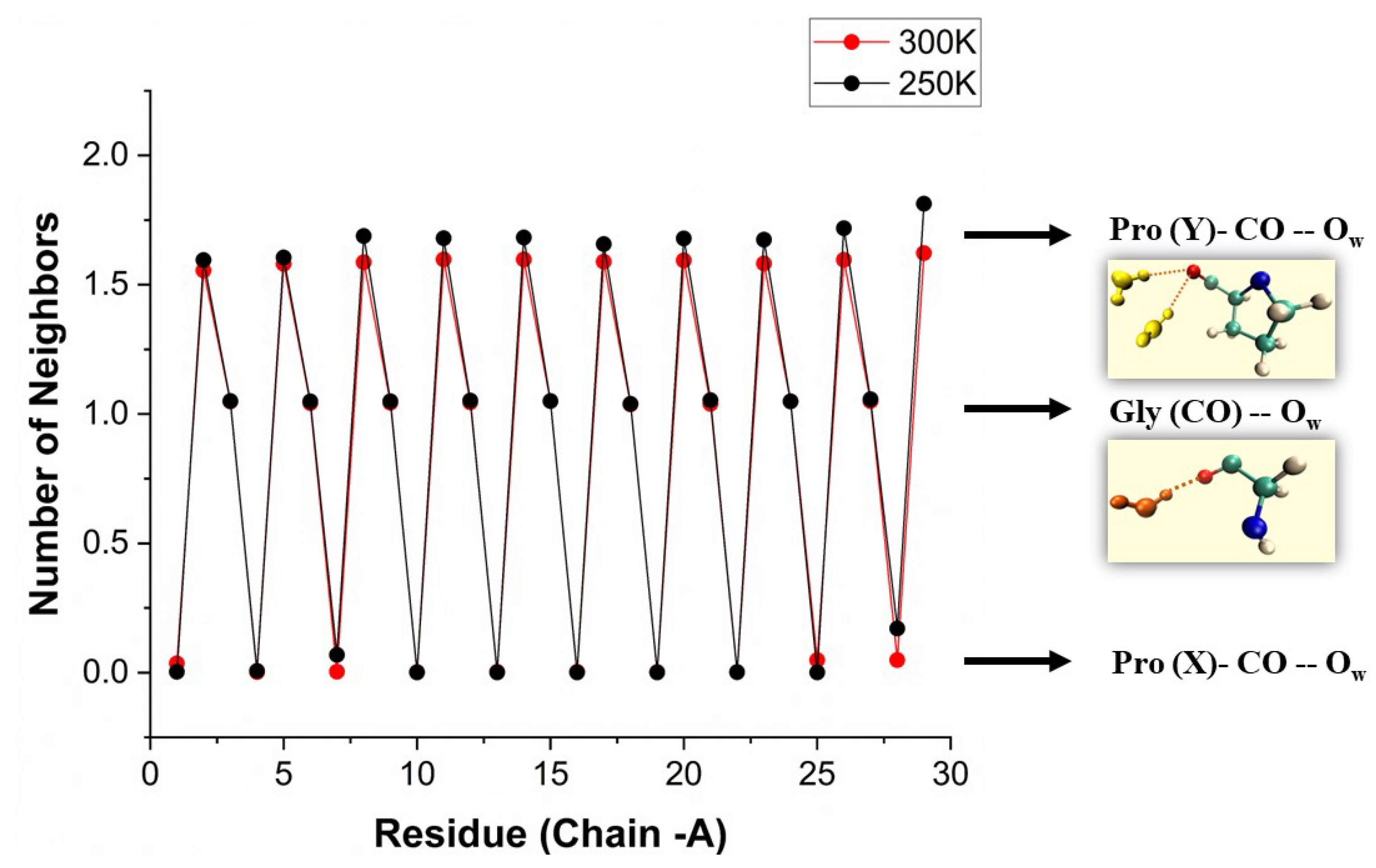

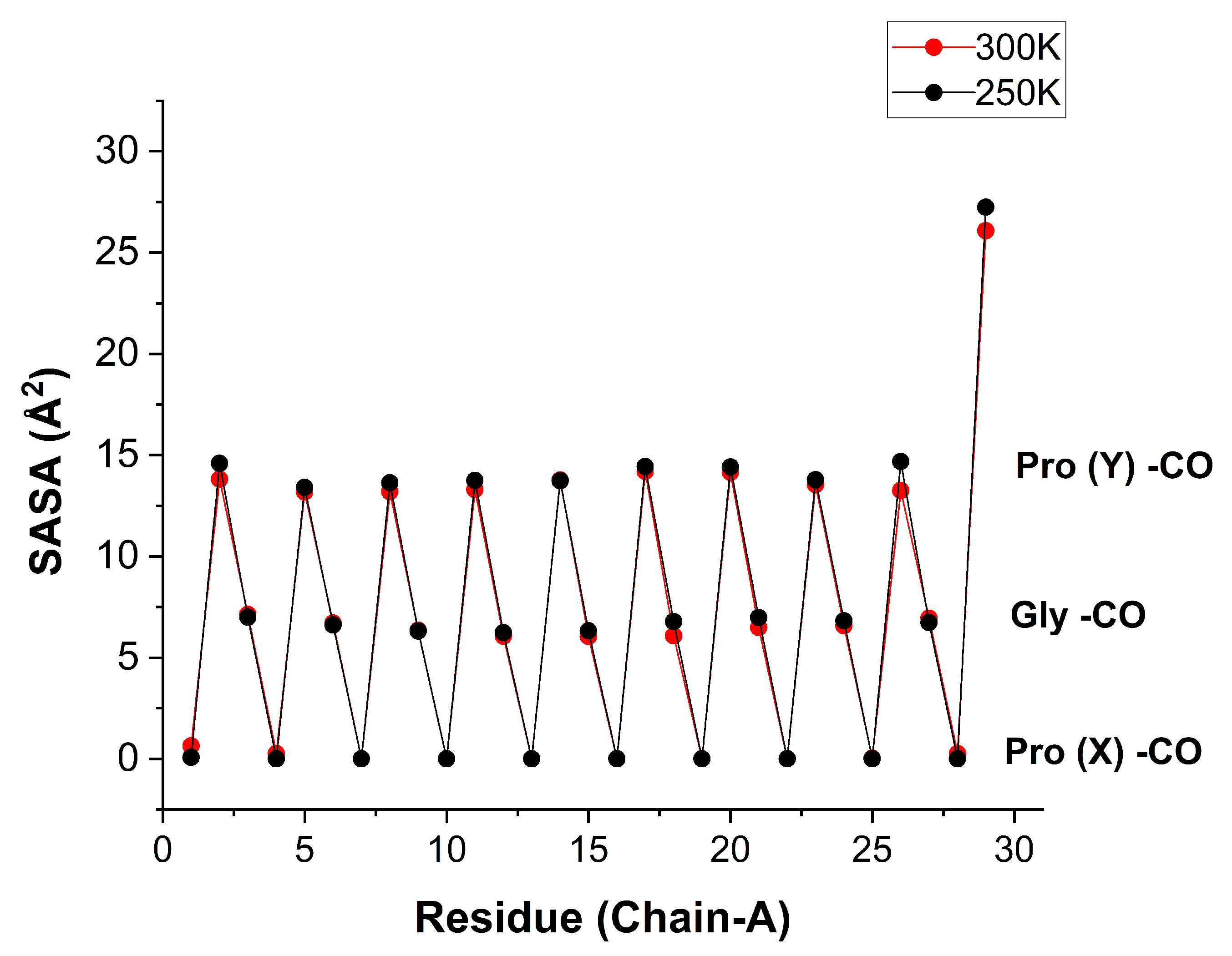

The results, for the bb-carbonyls of each residue in the

chain are plotted in

Figure 8 against the residue number. Similar results for all three chains are given in Figure S7, and against the residue number of Gly and Pro(Y) separately – in Figure S8.

The similarity of these liquid phase results and the crystal data in

Figure 5 (at about 100 K) is rather striking. In both cases the hydration numbers of Pro(X)-CO and Gly-CO are 0 and 1, whereas that of Pro(Y)-CO, which is 2 in the crystal state, is in the range 1.6-1.7 here. Additionally, the first two values are nearly temperature independent, while that of Pro(Y)-CO is enhanced by lowering the temperature. The larger temperature effect on Pro(Y)-CO vs Gly-CO hydration suggests that the Gly-CO⋯HOH HB is stronger than Pro(Y)-CO⋯HOH HB or, more accurately, stronger than the

second HB to Pro(Y)-CO. In a similar vein, Figure S9 shows that only the Pro(Y)-CO hydration at 300 K depends on the water model, becoming too small when TIP4P/2005 is replaced by TIP3P. The overall average, over all CO sites in the protein, is given in

Table 3.

That our hydration numbers for Pro(Y)-CO are indeed close to the crystal data can be appreciated in comparison with previously reported hydration numbers of

peptides having their Hyp-CO coordination number around 1.3 [

10,

21]. Recent MD simulations of a more complex tripeptide, having the

structure only at its two ends, reported an average of 1.26 waters bound to the Hyp-CO site [

33]. To our knowledge, no study has previously suggested a hydration number so close to 2 (the X-ray value). We interpret this as evidence for the high order of the

hydration layer, which is in line with the high order of the tripeptide itself, as deduced from our

analysis (above).

3.3.2. Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

How can one explain the remarkable regularity of water hydration at the CO sites? To further explore this, we present an analysis using the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA). It is obtained by rolling a sphere with the water radius, 1.4 Å, on the surface of the peptide [

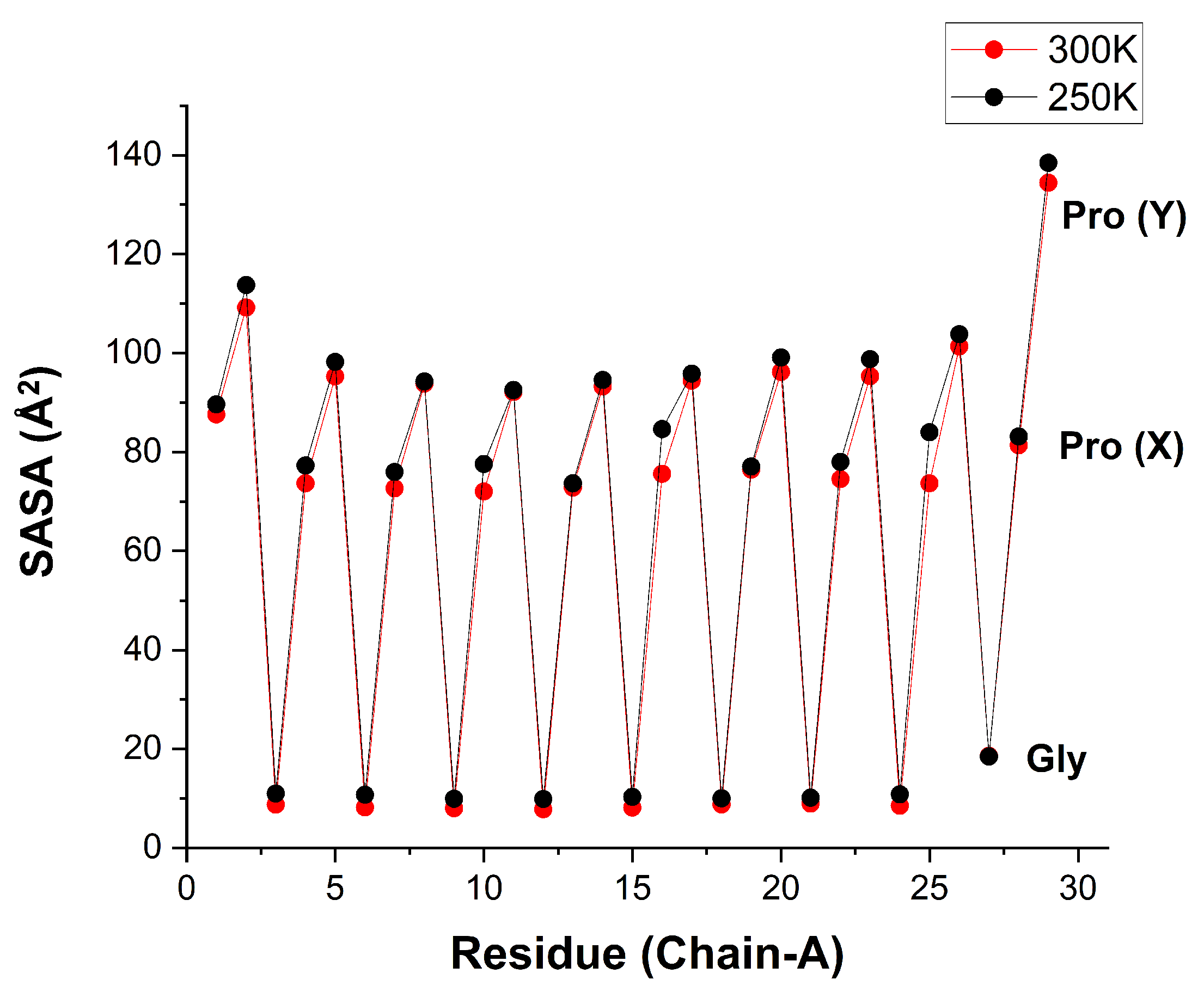

56]. The SASA measures the available space above the surface into which a WM could fit – a purely geometrical property. We calculated the SASA using the VMD “measure sasa” command, as embedded in Tcl script S2. The time averaged SASA values for each bb-O atom in the tripeptide are collected in Tables S4 (300 K) and S5 (250 K).

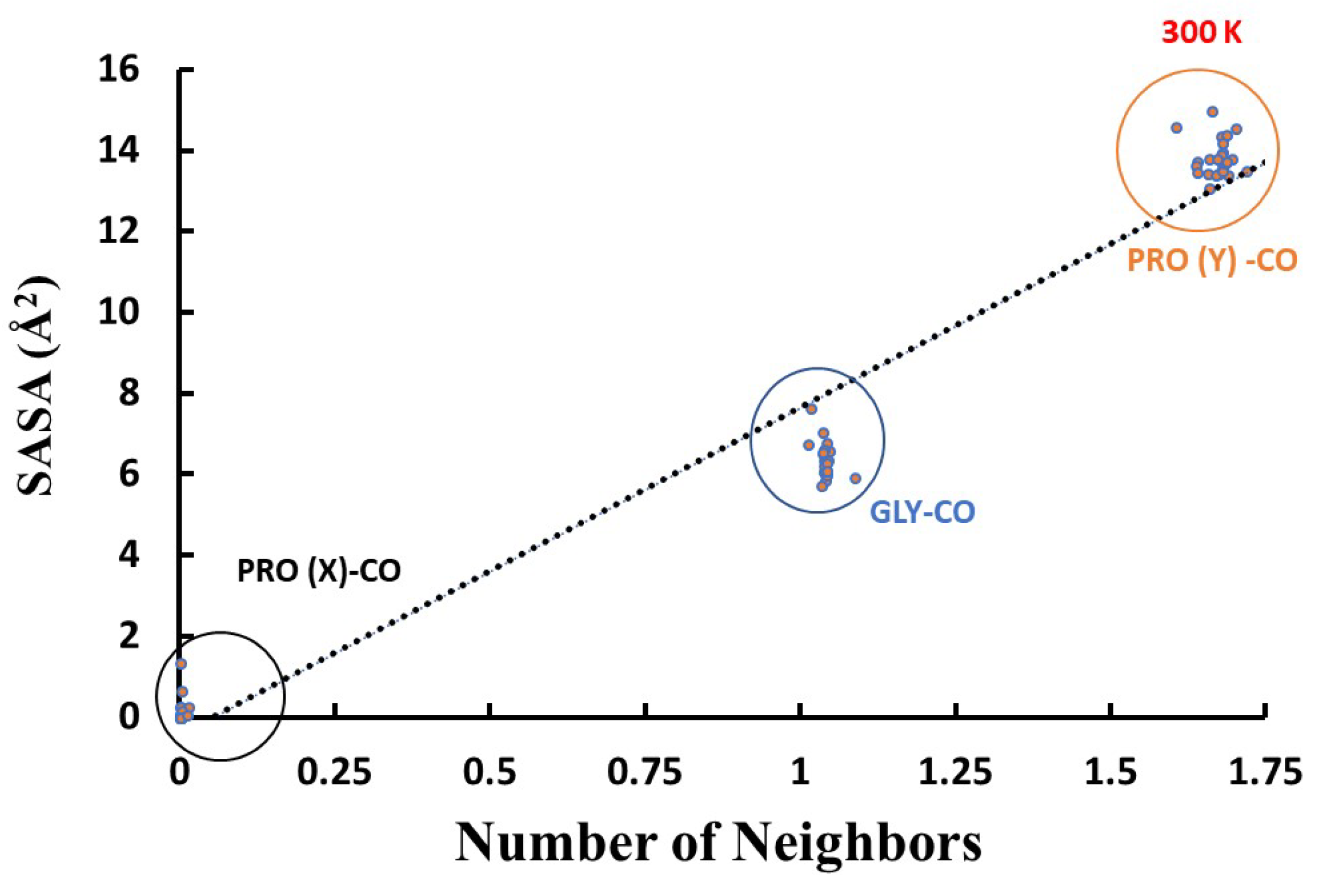

Figure 9 shows these values for each consecutive residue of a given peptide chain. The orderly saw-tooth structure testifies to an ordered peptide structure with a repetition unit of three. The SASA for the Pro(X)-CO oxygen atoms is zero, just like their coordination numbers, while the SASA for Pro(Y)-CO is slightly over twice that of Gly-CO, similar to the ratio of their coordination numbers. When the SASA values are further averaged over all like-residues, one obtains the results in

Table 4.

Figure 10 shows that the SASA of the carbonyl-oxygen atoms is highly correlated with the number of WMs around it (Pearson correlation,

= 0.9582 at 300 K). Thus, the primary explanation for the 0-2-1 solvation pattern is geometric, i.e. existence of available space for water entry. However, the deviation from linearity could indicate that additional factors are operative, producing the under-coordinated Pro(Y). For example, the water HB strengths: A double-donor configuration, OH⋯O⋯HO, is known to be less stable (weaker HB) than a donor-acceptor configuration, OH⋯OH⋯O, so that it is preferable for the second ligand to move to the second hydration-shell.

It is instructive to compare, for each residue, the SASA of the single carbonyl oxygen atom with that of the whole residue. For whole residues,

Figure 11 shows the same sawtooth regularity, but with completely different SASA values (

Table 5). Now the SASA of Pro(X) is no longer close to zero, but rather nearly as large as for Pro(Y). This follows because the SASA of whole Pro residue is contributed mainly from its side-chain ring. In contrast, the SASA of the whole Gly residue is just a trifle larger than the Gly-CO SASA, likely because most of this residue’s atoms are close to the lipid axis, and thus shielded from the solvent. The structural HB between Gly-CO and Pro(X) may direct some of its atoms to the peptide axis as well, and this may explain why the Pro(X) SASA is still somewhat smaller than Pro(Y).

3.3.3. Hydrogen-Bonded Second Hydration Shell

The first hydration shell around the oxygen atom of Res-CO (Res = Gly or Pro) was established in

Section 3.3.1 using a RDF, herein

, of water around the above-mentioned O atom. By convention, the first shell ends at the first minimum of

that occurs (as in bulk water) at

Å. The number of neighbors is then the integral of

up to

. There are now two ways to extend the analysis to a second hydration shell:

- (a)

Use the same

as above, and integrate its second peak namely, from

to the second minimum, which occurs around 5.61 Å (see

Figure 7). “Second neighbors” by this criterion will include WMs that are not HBed to the water in the first hydration shell (Res-CO⋯HOH).

- (b)

Restricting our interest to WMs that are directly HBed to first-shell waters requires that we consider another RDF, , that is centered on a first-shell WM of Res-CO. The integral of up to its first minimum, , is subsequently the number of HBed WMs in the second layer of Res-CO.

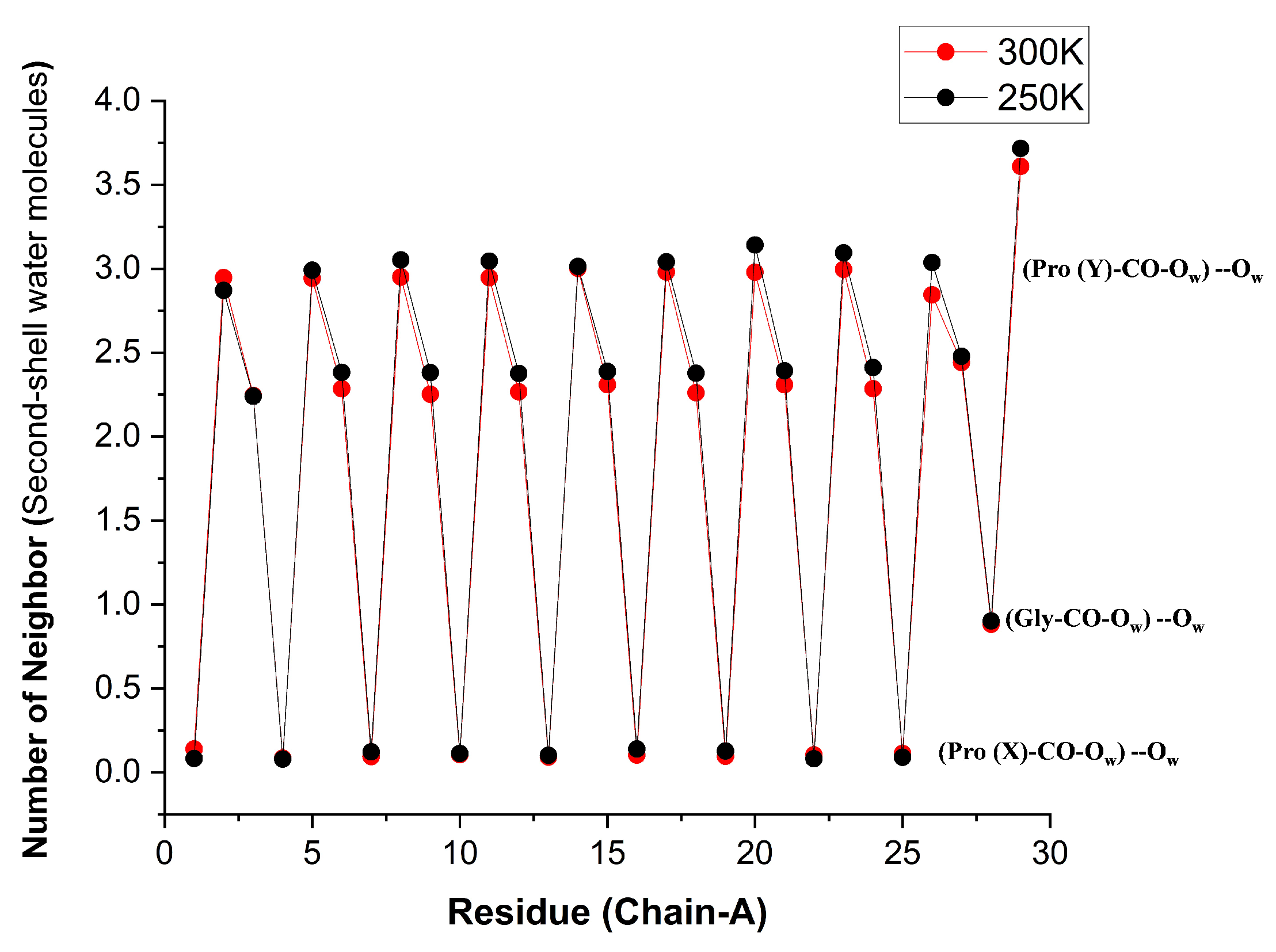

Using the second criterion, we obtain the (time averaged) results shown in

Figure 12. When these are further averaged over all like-residues in the peptide, the values of

Table 6 are obtained. Pro(X)-CO does not display any second-shell hydration characteristics because it has no first-shell hydration layer. Gly-CO has slightly over two second shell neighbors (i.e., Gly-CO⋯HOH has slightly over two first shell neighbors). It is possible (though we did not check this) that these are mostly two HB-donating WMs. Pro(Y)-CO has about 1.5 neighbors in the first shell. If each of these has about two neighbors in the second shell, a total of three 2nd shell neighbors is obtained. We also visualized that when a second WM HBs to Pro(Y)-CO, it often forms an HB “bridge" with the adjacent Gly-CO⋯HOH.

3.4. Residence Time Distribution of Water Near Res-CO

The results presented thus far raise a perplexing question: How come Res-CO (and, particularly, Gly-CO) hydration is so uniform (varying so little with residue number or temperature)? One possibility is thermodynamic. According to Fullerton [

24] (see Introduction), water bridges in collagen are so strong that they “exhibit dynamic and thermodynamic properties of one-dimensional ice” [

33]. In particular, this should apply to the strong Res-CO⋯HOH HBs. Indeed, we find that the 0-1.7-1 hydration pattern of [(PPG)

]

in liquid water is similar to the 0-2-1 pattern in ice. However, to explain Fullerton’s NMR data, the “one-dimensional ice” theory should be valid at least up to the msec time-regime, while no MD simulation reported lifetimes longer than, say, 10 ps [

30,

32,

33].

The second possibility is kinetic: While water dissociation from the Res-CO site is fast, the recombination by an alternate WM is even faster, so that the binding site is rarely ever vacant. Here we set to investigate these possibilities.

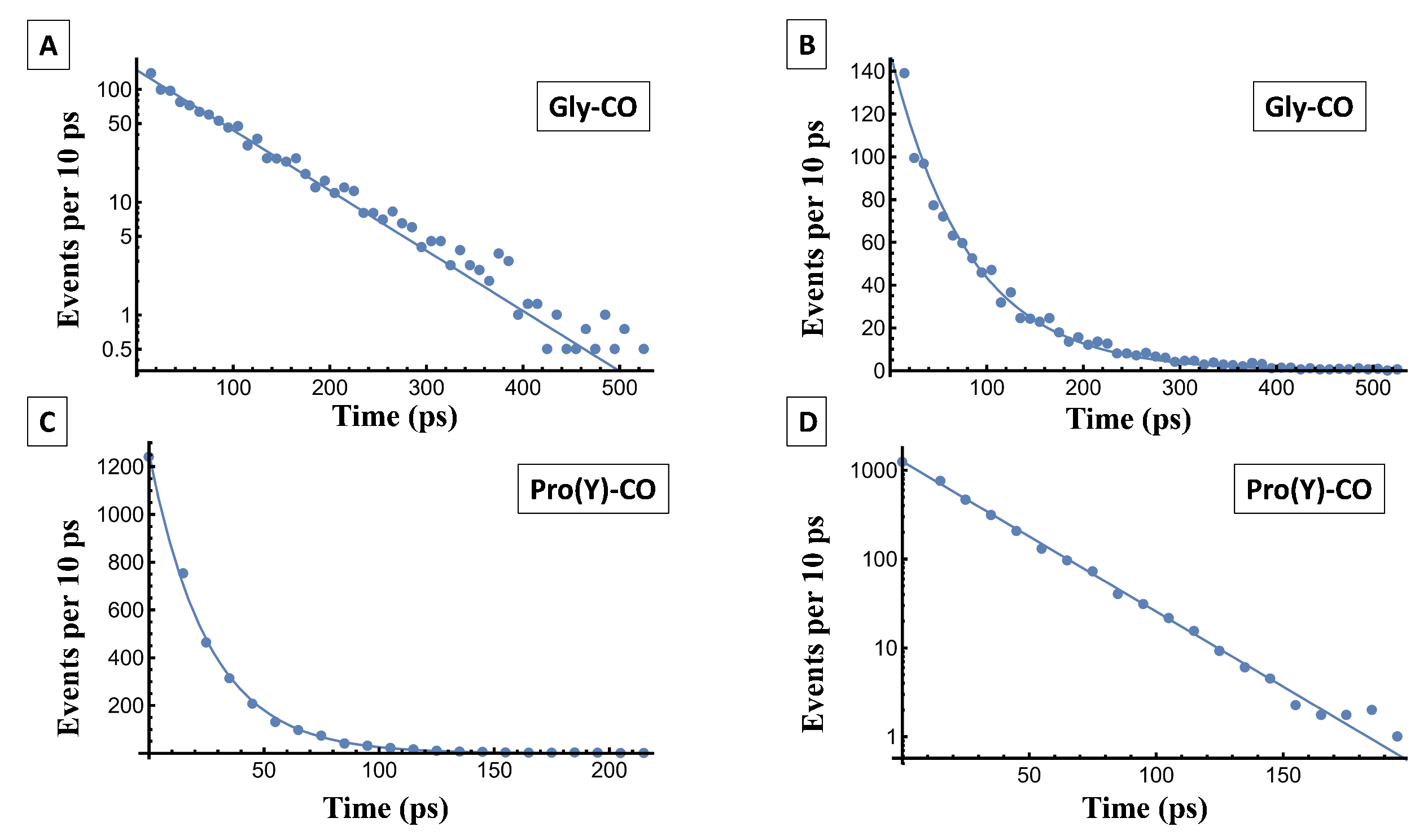

The residence time, , measures the time that elapsed between a WM arriving and leaving a binding site, such as Res-CO, where a water at the site is defined by the CO⋯O distance being less than a cutoff distance (3.5 Å). We do not measure the distance to the water H atoms, because these can interchange without the water oxygen, O, leaving its bound position (water libration). Moreover, if a water ligand leaves for a single time step, returning in the next step, the binding episode is not discontinued. Only moving outside the cutoff distance for more than a single time-step ends the sojourn. These are the underlying assumptions in the Tcl script S3, utilized herein.

The list of

values obtained this way spans a wide range of times. Averaging over the list gives the average residence time,

. Else, the

values are binned, the number of occurrences in each bin depicting a temporal correlation function,

, as shown in

Figure 13. Fitting it to an exponential function,

, is another way of obtaining

. [This follows because the exponential distribution obeys

].

The fitting parameters,

A and

, are listed in

Table 7. Overall, water at Gly-CO has longer residence times than at Pro(Y)-CO, which is in line with a stronger Gly-CO⋯HOH HB. In Pro(Y)-CO it is mostly the second water ligand that leaves, whose HB is weaker than the first one. For the same reason (see above), the coordination number of Gly-CO varies less with residue number or temperature as compared to Pro(Y)-CO.

We have noted that a WM departure from the Res-CO site was always accompanied by the binding of another WM, so essentially there is no free site in this scenario.

Returning to the question of “ice-like” HBs or not, this study agrees with previous MD studies, in which no ice-like HBs were identified. Even the strongest water-collagen HB, Gly-CO⋯HOH, exhibits a sub-100 ps lifetime (much faster than the NMR timescale [

57] ). On the other hand, this lifetime is notably longer than the average lifetime of 4 ps previously calculated [

33], or either the single-molecule or cooperative Debye relaxation times in bulk liquid water (ca. 1 ps and 8.3 ps at 300 K, respectively [

58]).

4. Conclusions

Collagen, with its peculiar triple-helix structure, is one of the major proteins in the ECM. It is imperative to achieve better understanding of the dynamic consequences of its structure, not only for coping with living organisms, but possibly also for seeking inspiration concerning the construction of man-tailored materials. Unfortunately, it is not possible to isolate even a few of the many collagen structures for laboratory study. Much of what we currently know, on the molecular level, is based on synthetic collagen biomimetic peptides. Such is the [(PPG) 90-residue peptide (30 in each chain), which is the prime model system for the current theoretical study.

Single-chain proteins can partially fold to assume a nearly spherical (globular) shape, in which case

is the radius (in Å) of the globule. It increases rather slowly with the number of amino acid residues,

N, as [

59]

A similar power-law correlation has also been established with the proteins’ molecular weight [

60]. In contrast to globular proteins, an elongated protein will have a notably larger

. For example, setting

in Equation (

6) gives 13.1 Å, in comparison to

Å obtained here for [(PPG)

]

(see

Table 1). Thus, the (PPG)

tripeptide is clearly an elongated molecule rather than a spherical one.

This, however, does not capture its high symmetry. To establish it quantitatively, we have presented, in

Section 3.2, a simple model for a linear repetitive molecule. The

n-unit tropocollagen is depicted as a rigid linear array of equidistant (distance

l) points of equal mass (PPG triplets). This results in two analytical expressions for

as a function of

n, to be used for odd and even

n:

The distance,

l, between beads can be obtained from the difference in

for simulated peptides of different lengths (

Table 2). For example, from

for

and 9

Å (at 300 K). With this,

is given in

Figure 14 which, in contrast to the power-law in Equation (

6), is practically linear.

From Equation (

7) we find that for

and 10

and 25.42 Å, respectively, in excellent agreement with our simulated values (24.0 and 25.6 Å) in

Table 1. Thus, the depiction of the (PPG)

peptide as a linear array of PPG triplets is in good agreement with the simulations.

A central goal of the present work is to characterize the hydration pattern in a “simple” collagen tripeptide, [(PPG)

]

. The careful

analysis performed in

Section 3.2 suggests that the tripeptide resembles a cylinder on which the amino-acids are arranged. Because this cylinder is not appreciably bent, all Pro(X) residues are located in equivalent environments, and similarly for Pro(Y) and Gly. Given that the only water binding sites on this CMP are the bb-carbonyls, the expected outcome could be a regular hydration pattern.

Indeed, by monitoring the number of WMs bound to each Res-CO site, we have found a remarkably regular pattern. Pro(X)-CO does not bind any WM, Pro(Y)-CO binds around 1.6–1.7 WMs, and Gly-CO about one. This 0-1.7-1 pattern holds for all 90 residues of the triple-helix (excepting those at the very ends of the chains). This behavior is reminiscent of the 0-2-1 hydration pattern observed in X-ray structures at 100 K, even though our simulated system is in liquid water and at room temperature.

To better understand this behavior, we have monitored the SASA of each oxygen atom of the tripeptide. It exhibits a pattern similar to the bb-carbonyl water coordination, of ca. 0-6.5-15 Å

. Thus, near the Pro(X)-CO site there is simply not sufficient space to insert a WM. The ratio of the Pro(Y) to Gly oxygen-atom SASA values, about 2.3, shows that (as in the crystal state) there is sufficient space for two WMs near Pro(Y)-CO. The reason for the reduced coordination at the Y position must then be energetic: The second WM is bound less strongly in the Pro(Y)-CO site. This is also manifested by the enhanced fluctuations in the Pro(Y)-CO coordination number with residue index (e.g.,

Figure 8), as compared with Gly-CO. It follows that (at least) the first WM bound to each Res-CO site (excepting Pro(X)-CO) exhibits high spatial order.

Dynamically, there is a large difference between the peptide’s hydration in ice vs. liquid water. While the WMs seen in the X-ray structures likely exchange very slowly, in liquid water they do so on the 100 ps timescale, as evidenced from our residence time calculations. While this is slower than suggested from previous simulations in the literature (ca. by a factor 20) [

33], it is still orders of magnitude faster than in ice.

How can the bound WMs show such regularity in their coordination numbers in spite of their fast dynamics? We find that a bound WM leaving the site is immediately replaced by another. Thus WMs undergo an exchange, i.e. substitution, rather than a dissociation reaction. Consequently, there is always a WM at the site, resulting in highly ordered Res-CO hydration in spite of the high temperature.

In contrast to the strong HBs found between WMs and the bb-carbonyls, we have not discovered in the [(PPG)

]

peptides inter-helix water bridges, or ice-like water bridges, which are only detectable via x-ray [

24]. Thus, at least from the simple CMP studied here, we cannot claim that water wires contribute to the stability of collagen. Conversely, the rigidity of collagen contributes towards an exceptional ordering of its (mainly, first-shell) hydration water.

The ordering of the WM dipole moments around the collagen axis (with cylindrical symmetry) could generate a cylindrical electrostatic field in the water phase surrounding the triple helix. If this field is sufficiently strong, it could guide the diffusion of ions (and protons) parallel to its axis, constituting a one dimensional ion conductor.

Figure 1.

(A) The root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) for each carbon of the [(PPG))] peptide at 250 K (black) and 300 K (red). (B) Comparison of superimposed triple-helix structures at different temperatures: initial configuration in purple and final structure in red. [ AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 saved frames)].

Figure 1.

(A) The root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) for each carbon of the [(PPG))] peptide at 250 K (black) and 300 K (red). (B) Comparison of superimposed triple-helix structures at different temperatures: initial configuration in purple and final structure in red. [ AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 saved frames)].

Figure 2.

The first four smallest linear peptides in our model (two even and two odd), whose CMs are along the vertical line. The values of k and for each peptide chain are indicated in the figure. Each value of k appears twice: For even and odd n.

Figure 2.

The first four smallest linear peptides in our model (two even and two odd), whose CMs are along the vertical line. The values of k and for each peptide chain are indicated in the figure. Each value of k appears twice: For even and odd n.

Figure 3.

Ratio of radius of gyration to end-to-end distance as a function of the number of PPG triplets (circles), calculated from Equations (

3) (blue) and (

5) (brown). Lines represent interpolations. Simulated values for odd and even [(PPG)

]

peptides are depicted by squares and triangles, respectively. Open circles are ratios of simulated

to the X-ray

values.

Figure 3.

Ratio of radius of gyration to end-to-end distance as a function of the number of PPG triplets (circles), calculated from Equations (

3) (blue) and (

5) (brown). Lines represent interpolations. Simulated values for odd and even [(PPG)

]

peptides are depicted by squares and triangles, respectively. Open circles are ratios of simulated

to the X-ray

values.

Figure 4.

Schematic HBs of the [(PPG)] peptide. The three chains forming the triple helix are conventionally denoted as trailing (T), middle (M) and leading (L), with the T chain repeated on the right to show the interactions more clearly. Dashed blue arrows depict the structural Gly-NH···OC-Pro(X) HBs. The WMs shown resemble those found in the X-ray diffraction studies: The single orange WM binds to Gly-CO, while the two yellow ones − to Pro(Y)-CO.

Figure 4.

Schematic HBs of the [(PPG)] peptide. The three chains forming the triple helix are conventionally denoted as trailing (T), middle (M) and leading (L), with the T chain repeated on the right to show the interactions more clearly. Dashed blue arrows depict the structural Gly-NH···OC-Pro(X) HBs. The WMs shown resemble those found in the X-ray diffraction studies: The single orange WM binds to Gly-CO, while the two yellow ones − to Pro(Y)-CO.

Figure 7.

RDF profiles (A,C) and their indefinite integrals (B,D) for water surrounding the carbonyl oxygens of the Gly and Pro(Y) residues of [(PPG)] at 300 K (red) and 250 K (black). [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns simulation (10000 frames)].

Figure 7.

RDF profiles (A,C) and their indefinite integrals (B,D) for water surrounding the carbonyl oxygens of the Gly and Pro(Y) residues of [(PPG)] at 300 K (red) and 250 K (black). [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns simulation (10000 frames)].

Figure 8.

Number of water neighbors in the first solvation shell of the Res-CO sites on the -chain of the [(PPG)] peptide, obtained from integrating at two different temperatures, 250 K (black) and 300 K (red) [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns simulation (10000 frames)]. Results for all three chains appear in Figure S7.

Figure 8.

Number of water neighbors in the first solvation shell of the Res-CO sites on the -chain of the [(PPG)] peptide, obtained from integrating at two different temperatures, 250 K (black) and 300 K (red) [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns simulation (10000 frames)]. Results for all three chains appear in Figure S7.

Figure 9.

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (in Å) for the bb-carbonyl oxygen atoms of chain residues of the [(PPG)] peptide at 250 K (black) and 300 K (red). Data for all three chains are listed in Tables S4 and S5, and plotted in Figure S10. Separate plots for SASA values for Gly and Pro(Y), against the residue numbers are shown in Figure S11. A comparison of the results for the TIP3P vs. TIP4P/2005 water models is presented in Figure S12. [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Figure 9.

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (in Å) for the bb-carbonyl oxygen atoms of chain residues of the [(PPG)] peptide at 250 K (black) and 300 K (red). Data for all three chains are listed in Tables S4 and S5, and plotted in Figure S10. Separate plots for SASA values for Gly and Pro(Y), against the residue numbers are shown in Figure S11. A comparison of the results for the TIP3P vs. TIP4P/2005 water models is presented in Figure S12. [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Figure 10.

Correlation plot of the number of water neighbors with the oxygen carbonyl SASA values in our simulations of collagen triple-helix at 300 K [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Figure 10.

Correlation plot of the number of water neighbors with the oxygen carbonyl SASA values in our simulations of collagen triple-helix at 300 K [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Figure 11.

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (in Å) for each residue in the chain of the hydrated [(PPG)] peptide at 250 K (black) and 300 K (red) [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Figure 11.

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (in Å) for each residue in the chain of the hydrated [(PPG)] peptide at 250 K (black) and 300 K (red) [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Figure 12.

Time-averaged number of WMs that are HBed to the inner-shell water ligands of Res-CO for chain residues of the [(PPG)] peptide at two different temperatures. Obtained by integrating the RDF in VMD up to , where is defined by selection 1 = “atom and within of residue Res and name O”, selection 2 = “atom ”. [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, Water- 62306,100 ns (10000 frames)].

Figure 12.

Time-averaged number of WMs that are HBed to the inner-shell water ligands of Res-CO for chain residues of the [(PPG)] peptide at two different temperatures. Obtained by integrating the RDF in VMD up to , where is defined by selection 1 = “atom and within of residue Res and name O”, selection 2 = “atom ”. [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, Water- 62306,100 ns (10000 frames)].

Figure 13.

The time-dependent residence probability of WMs near the Res-CO oxygen atom, (

A) Gly-CO and (

C) Pro(Y)-CO. Circles represent the simulation data, while the solid line is a mono-exponential fit to it. (

B,

D) show these data on a semi-logarithmic scale, in which the straight lines reveal the underlying exponential decay. The parameters of the fit are listed in

Table 7.

Figure 13.

The time-dependent residence probability of WMs near the Res-CO oxygen atom, (

A) Gly-CO and (

C) Pro(Y)-CO. Circles represent the simulation data, while the solid line is a mono-exponential fit to it. (

B,

D) show these data on a semi-logarithmic scale, in which the straight lines reveal the underlying exponential decay. The parameters of the fit are listed in

Table 7.

Figure 14.

Radius of gyration calculated from Equation (

7). See

Section 3.2.

Figure 14.

Radius of gyration calculated from Equation (

7). See

Section 3.2.

Table 1.

Time averaged radius of gyration, (in Å), for five collagen mimetic peptides, , , 5, 7, 9, and 10, simulated in aqueous solution at two different temperatures (300 K and 250 K), and further averaged over the three chains. For and 10 comparison is made with X-ray data (at ca. 80 K) from PDB files 2CUO and 1K6F, respectively).

Table 1.

Time averaged radius of gyration, (in Å), for five collagen mimetic peptides, , , 5, 7, 9, and 10, simulated in aqueous solution at two different temperatures (300 K and 250 K), and further averaged over the three chains. For and 10 comparison is made with X-ray data (at ca. 80 K) from PDB files 2CUO and 1K6F, respectively).

| Temperature |

|

|

|

|

|

| 300 K |

11.95 |

14.49 |

18.9 |

24.0 |

25.6 |

| 250 K |

11.91 |

14.36 |

18.96 |

23.9 |

25.5 |

| 100 K (X-ray) |

|

|

|

23.51 |

25.37 |

Table 2.

Averaged end-to-end distances, (in Å), calculated from our MD trajectories for five collagen-like peptides, , in aqueous solution at 300 K, and the corresponding values of . values are from Table S2, further averaged over the three chains. In parentheses are the and 10 entries calculated using the X-ray values at ca. 100 K from PDB files 2CUO and 1K6F, respectively (in place of the simulated values).

Table 2.

Averaged end-to-end distances, (in Å), calculated from our MD trajectories for five collagen-like peptides, , in aqueous solution at 300 K, and the corresponding values of . values are from Table S2, further averaged over the three chains. In parentheses are the and 10 entries calculated using the X-ray values at ca. 100 K from PDB files 2CUO and 1K6F, respectively (in place of the simulated values).

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

32.78 |

38.84 |

54.40 |

72.56 (70.66) |

81.41 (80.03) |

|

0.3645 |

0.3731 |

0.347 |

0.3308 (0.3382) |

0.3145 (0.3186) |

Table 3.

Average coordination numbers in the first hydration shells of Gly-CO and Pro(Y)-CO at two different temperatures [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Table 3.

Average coordination numbers in the first hydration shells of Gly-CO and Pro(Y)-CO at two different temperatures [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

| Temperature |

Water/Gly-CO |

Water/Pro(Y)-CO |

| 300 K |

1.041 |

1.61 |

| 250 K |

1.056 |

1.70 |

Table 4.

Time and ensemble average of the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) for the oxygen atoms of the carbonyl groups of respective residues at two temperatures [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Table 4.

Time and ensemble average of the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) for the oxygen atoms of the carbonyl groups of respective residues at two temperatures [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

| Temperature |

Gly-CO (Å) |

Pro(Y)-CO (Å) |

| 300 K |

6.43 |

15.03 |

| 250 K |

6.56 |

15.85 |

Table 5.

Time and ensemble average of the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) for each residue in the chain of the hydrated [(PPG)] peptide at 250 and 300 K [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

Table 5.

Time and ensemble average of the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) for each residue in the chain of the hydrated [(PPG)] peptide at 250 and 300 K [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, 62306 WMs, 100 ns trajectory (10000 frames)].

| Temperature |

Gly (Å) |

Pro(X) (Å) |

Pro(Y) (Å) |

| 300 K |

8.45 |

74.71 |

96.09 |

| 250 K |

10.57 |

78.79 |

101.87 |

Table 6.

Average hydration numbers in the second shell of Res-CO, restricted to WMs that are HBed to the first coordination shell [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, Water- 62306, 100 ns (10000 frames)].

Table 6.

Average hydration numbers in the second shell of Res-CO, restricted to WMs that are HBed to the first coordination shell [AMBER14SB+TIP4P/2005, Water- 62306, 100 ns (10000 frames)].

| Temperature |

Water/Gly-CO |

Water/Pro(Y)-CO |

| 300 K |

2.26 |

2.93 |

| 250 K |

2.37 |

3.01 |

Table 7.

The fitting parameters of the residence time distribution for water to reside near the carbonyl residues. The simulation data is fitted using a mono-exponential function, , where A is the pre-exponential constant and is the time constant.

Table 7.

The fitting parameters of the residence time distribution for water to reside near the carbonyl residues. The simulation data is fitted using a mono-exponential function, , where A is the pre-exponential constant and is the time constant.

| System |

A |

(ps) |

|

| Gly-CO (300 K) |

129.23 |

81.72 |

0.98 |

| Gly-CO (250 K) |

5.88 |

129.17 |

0.69 |

| Pro(Y)-CO (300 K) |

1258.0 |

25.68 |

0.99 |

| Pro(Y)-CO (250 K) |

590.81 |

39.34 |

0.98 |