Submitted:

30 September 2023

Posted:

02 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Constructs and site-directed mutagenesis

2.2. Cell cultures and transfections

2.3. Cells immunostaining

2.4. sAPPα secretion and total secreted Aβ Immunoprecipitation

2.5. Sandwich ELISA of secreted and intracellular Aβ

2.6. Western blotting

2.7. In vitro γ-secretase Assay

2.8. BACE1 fluorimetric Assay

2.9. a-secretase activity on intact cells

2.10. Neprilysin activity measurements.

2.11. In vitro cathepsin B activity assay

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

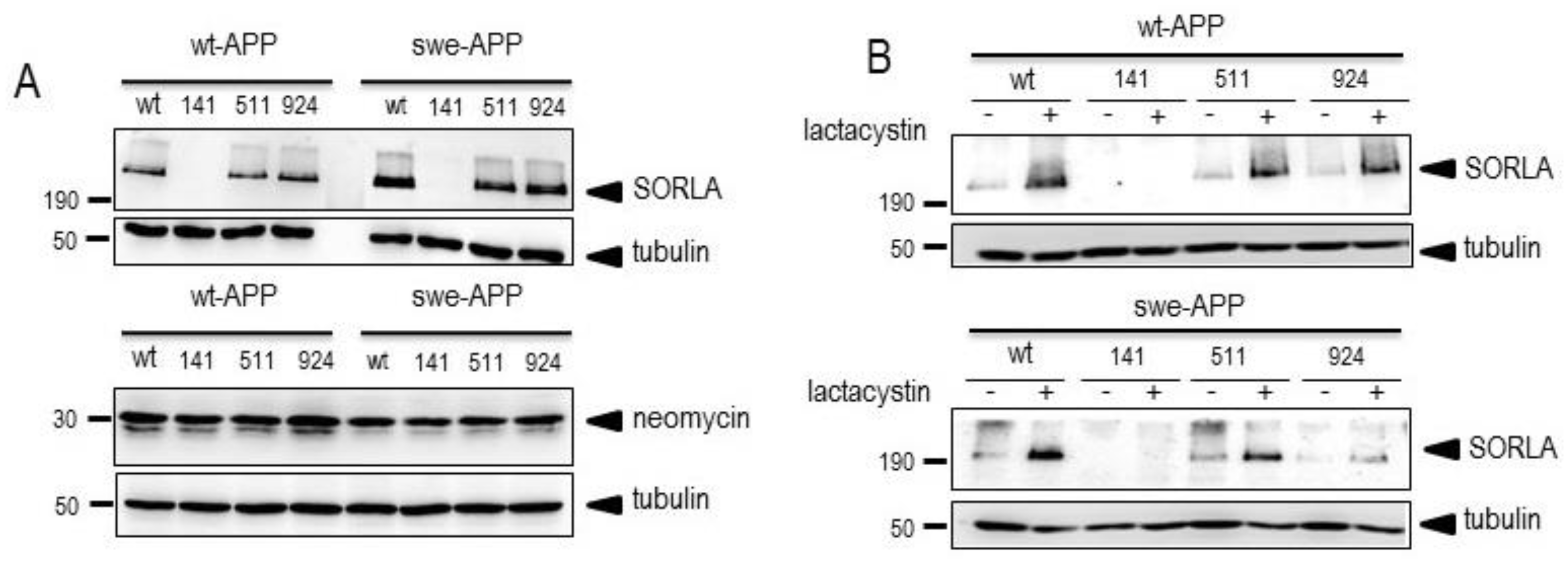

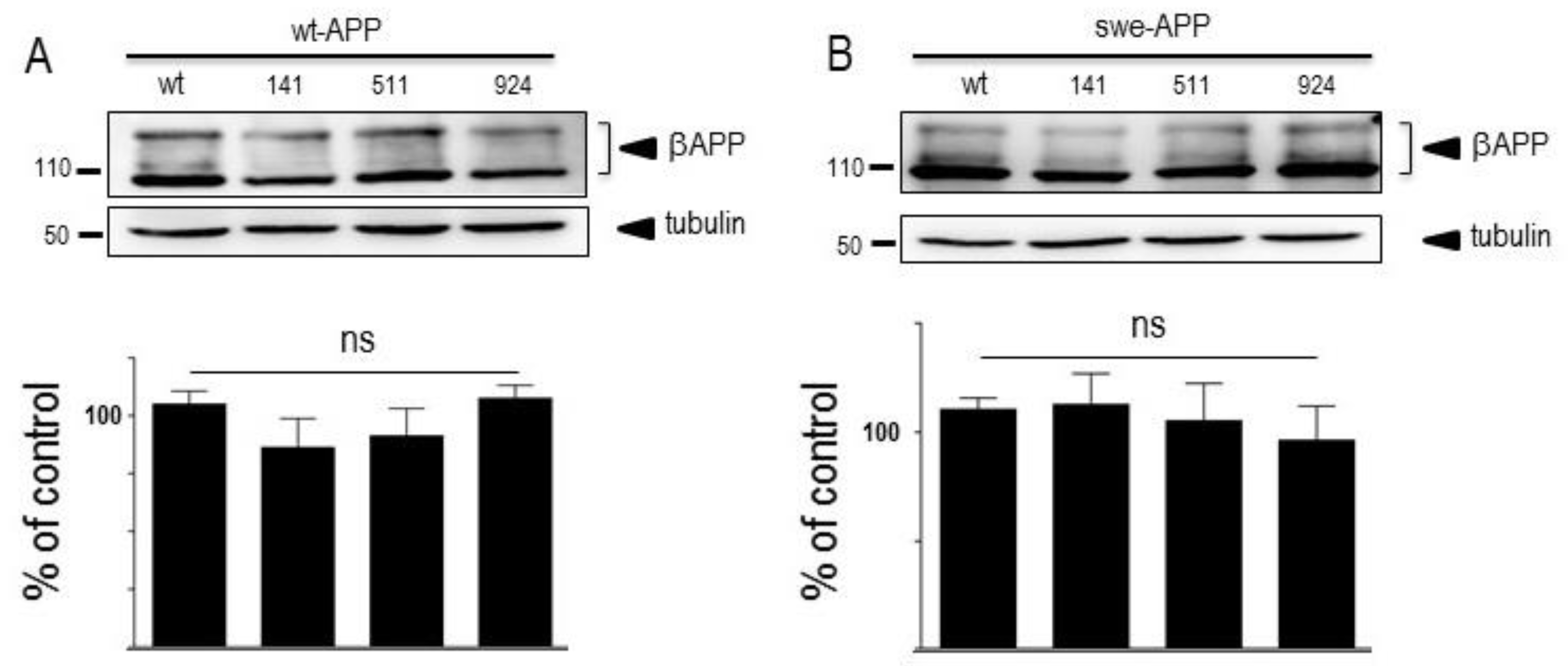

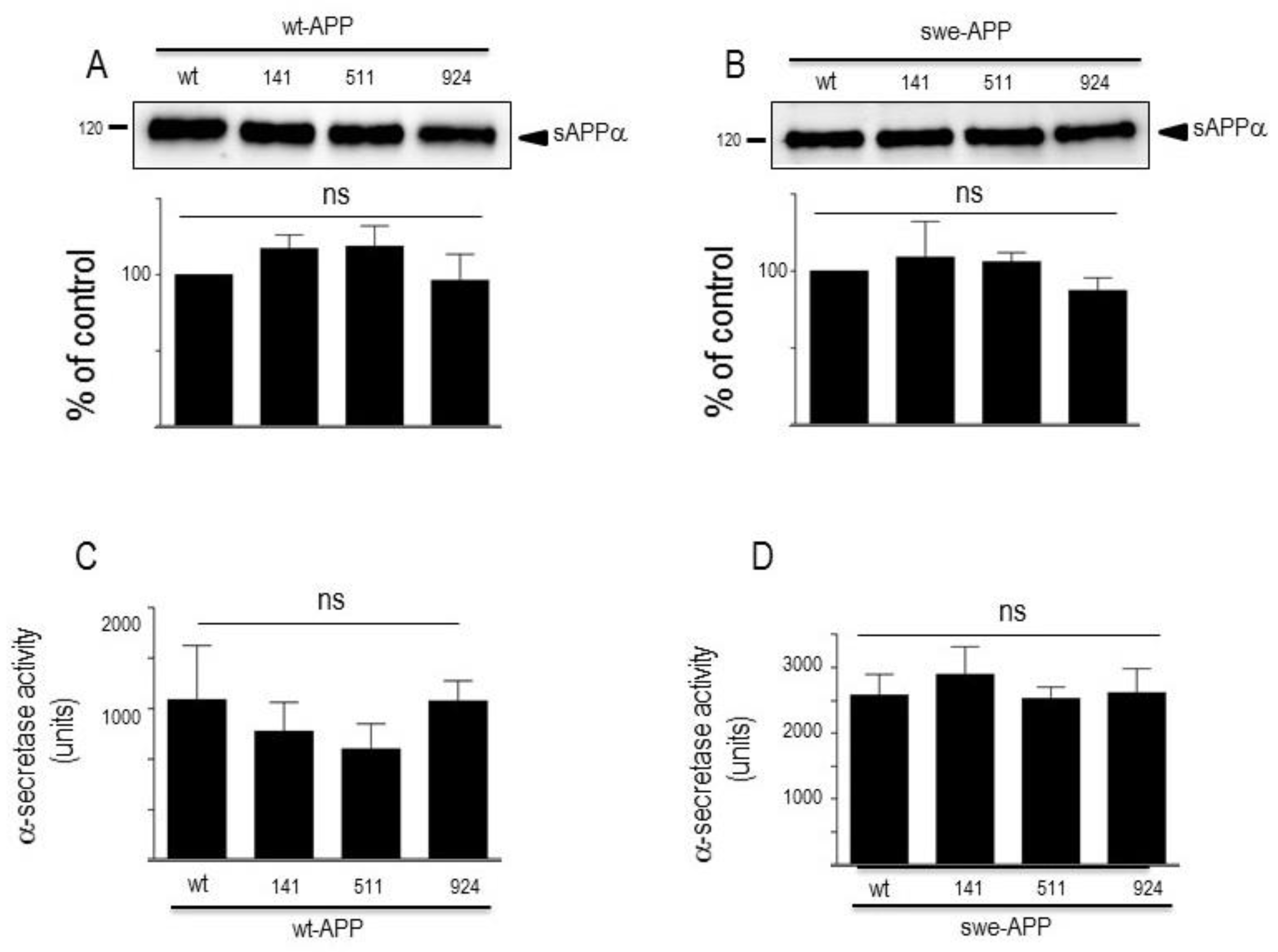

3.1. Influence of wild-type SorLA and its mutants on endogenous βAPP expression and on its non amyloidogenic proteolysis.

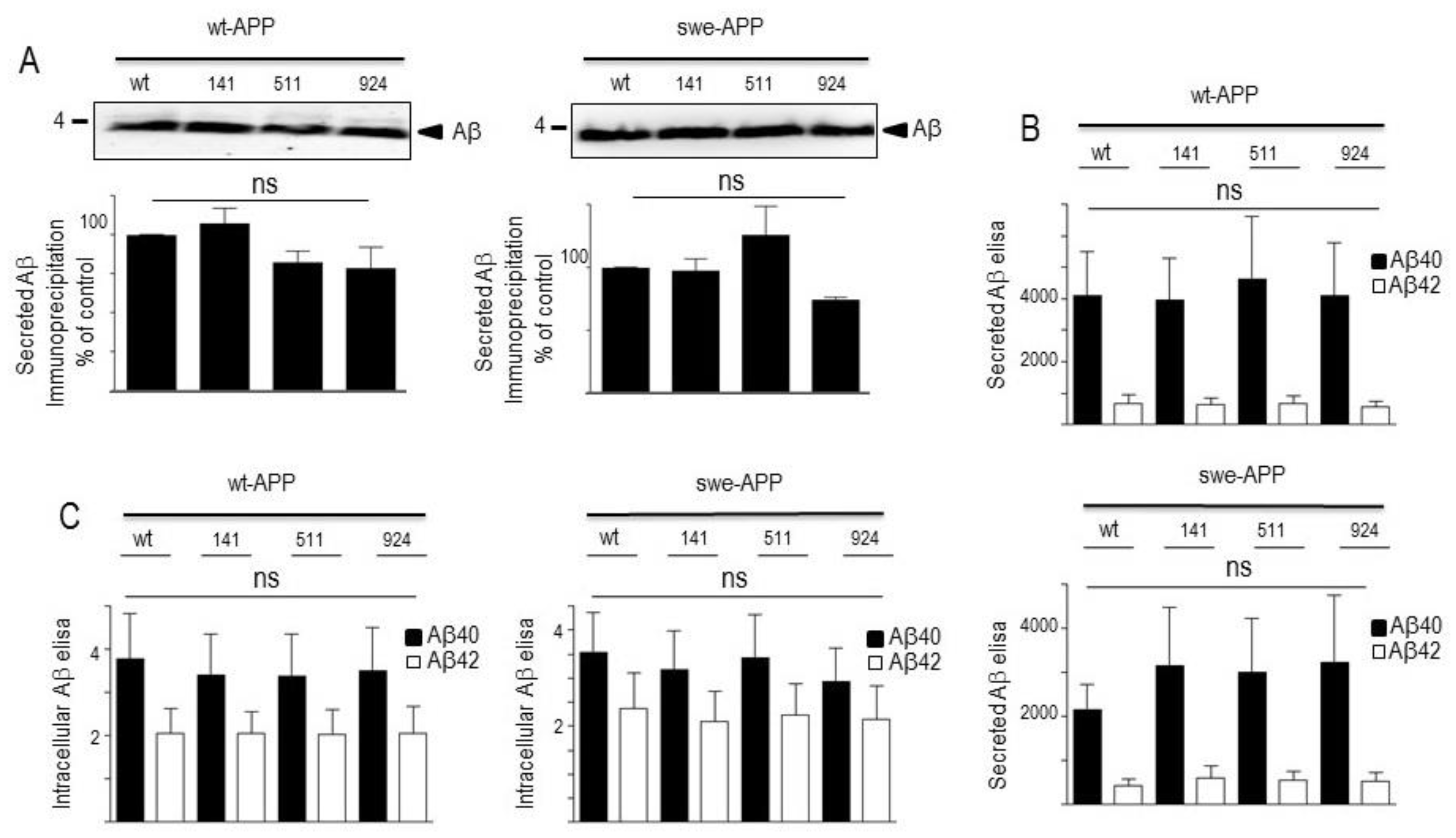

3.2. Influence of wild-type SorLA and its mutants on Aβ peptides and γ-secretase expression and activity.

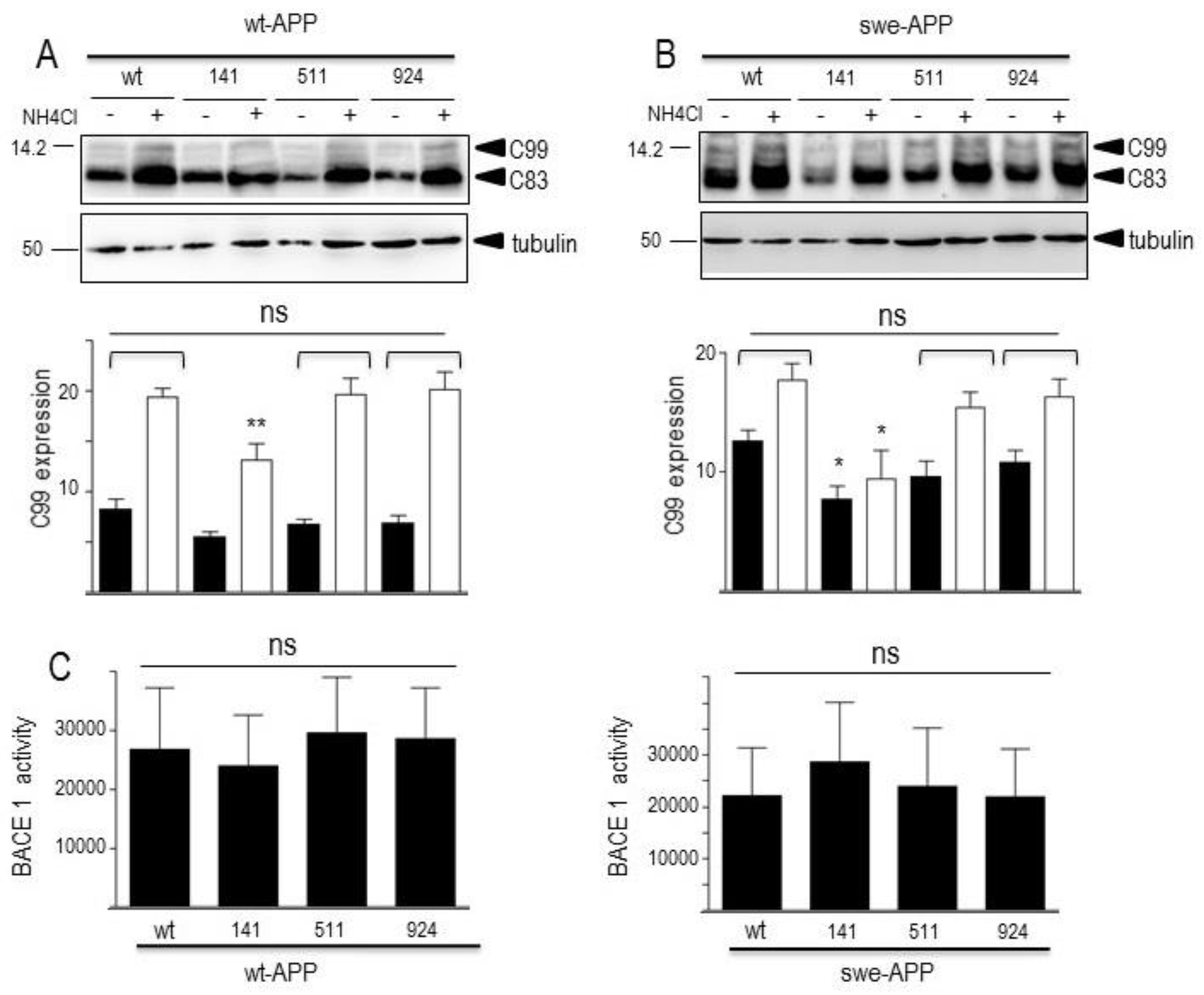

3.3. Influence of wild-type SorLA and its mutants on βAPP C-terminal fragments and β-secretase activity.

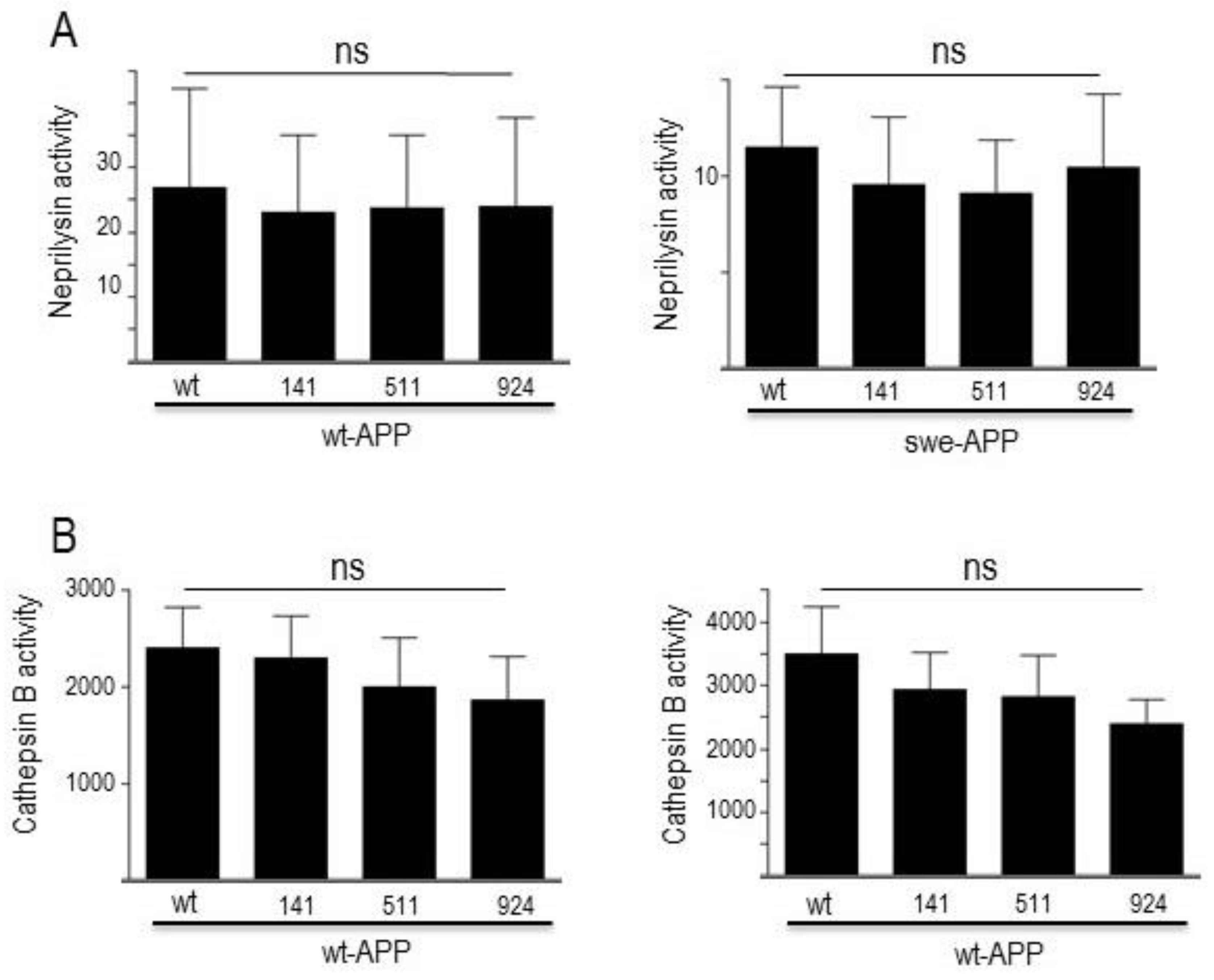

3.4. Influence of wild-type SorLA and its mutants on neprilysin and cathepsin B.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertram, L.; Tanzi, R.E. The genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Progress in molecular biology and translational science 2012, 107, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St George-Hyslop, P.H.; Petit, A. Molecular biology and genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Comptes rendus biologies 2005, 328, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacace, R.; Sleegers, K.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Molecular genetics of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease revisited. Alzheimer’s & dementia the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2016, 12, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlstrom, L.; Wiethoff, S.; Houlden, H. Genetics of neurodegenerative diseases: an overview. Handbook of clinical neurology 2017, 145, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, M.; Zhang, M.; Lu, Y. Genes associated with Alzheimer’s disease: an overview and current status. Clinical interventions in aging 2016, 11, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.C.; Amouyel, P. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: new evidences for an old hypothesis? Current opinion in genetics & development 2011, 21, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.C.; Ibrahim-Verbaas, C.A.; Harold, D.; Naj, A.C.; Sims, R.; Bellenguez, C.; DeStafano, A.L.; Bis, J.C.; Beecham, G.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 2013, 45, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogaeva, E.; Meng, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Gu, Y.; Kawarai, T.; Zou, F.; Katayama, T.; Baldwin, C.T.; Cheng, R.; Hasegawa, H.; et al. The neuronal sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, G.; Cheng, Z. An updated meta-analysis of the association between SORL1 variants and the risk for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2013, 37, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, C.; Cheng, R.; Rogaeva, E.; Lee, J.H.; Tokuhiro, S.; Zou, F.; Bettens, K.; Sleegers, K.; Tan, E.K.; Kimura, R.; et al. Meta-analysis of the association between variants in SORL1 and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2011, 68, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lei, H.; Zheng, M.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Hao, F. Meta-analysis of the Association between Alzheimer Disease and Variants in GAB2, PICALM, and SORL1. Molecular neurobiology 2016, 53, 6501–6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottier, C.; Hannequin, D.; Coutant, S.; Rovelet-Lecrux, A.; Wallon, D.; Rousseau, S.; Legallic, S.; Paquet, C.; Bombois, S.; Pariente, J.; et al. High frequency of potentially pathogenic SORL1 mutations in autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease. Mol Psychiatry 2012, mp201215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuccaro, M.L.; Carney, R.M.; Zhang, Y.; Bohm, C.; Kunkle, B.W.; Vardarajan, B.N.; Whitehead, P.L.; Cukier, H.N.; Mayeux, R.; St George-Hyslop, P.; et al. SORL1 mutations in early- and late-onset Alzheimer disease. Neurology. Genetics 2016, 2, e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, D.J. Normal and abnormal biology of the beta-amyloid precursor protein. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1994, 17, 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglayan, S.; Takagi-Niidome, S.; Liao, F.; Carlo, A.S.; Schmidt, V.; Burgert, T.; Kitago, Y.; Fuchtbauer, E.M.; Fuchtbauer, A.; Holtzman, D.M.; et al. Lysosomal Sorting of Amyloid-beta by the SORLA Receptor Is Impaired by a Familial Alzheimer’s Disease Mutation. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6, 223ra220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardarajan, B.N.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Cheng, R.; Bohm, C.; Ghani, M.; Reitz, C.; Reyes-Dumeyer, D.; Shen, Y.; Rogaeva, E.; et al. Coding mutations in SORL1 and Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2015, 77, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot-Sestier, M.V.; Sunyach, C.; Ferreira, S.T.; Marzolo, M.P.; Bauer, C.; Thevenet, A.; Checler, F. alpha-Secretase-derived fragment of cellular prion, N1, protects against monomeric and oligomeric amyloid beta (Abeta)-associated cell death. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 5021–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, I.; Becot, A.; Bourgeois, A.; Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Biferi, M.G.; Barkats, M.; Checler, F. Targeting gamma-secretase triggers the selective enrichment of oligomeric APP-CTFs in brain extracellular vesicles from Alzheimer cell and mouse models. Translational neurodegeneration 2019, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chami, L.; Buggia-Prevot, V.; Duplan, E.; Delprete, D.; Chami, M.; Peyron, J.F.; Checler, F. Nuclear factor-kappaB regulates betaAPP and beta- and gamma-secretases differently at physiological and supraphysiological Abeta concentrations. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 24573–24584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancolio, K.; Marambaud, P.; Dauch, P.; Checler, F. a-secretase-derived product of b-amyloid precursor protein is decreased by presenilin 1 mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 1997, 69, 2494–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, I.; Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Bauer, C.; Brigham, E.; Abraham, J.D.; Ranaldi, S.; Fraser, P.; St-George-Hyslop, P.; Le Thuc, O.; Espin, V.; et al. The beta-secretase-derived C-terminal fragment of betaAPP, C99, but not Abeta, is a key contributor to early intraneuronal lesions in triple-transgenic mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci 2012, 32, 16243–16255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afram, E.; Lauritzen, I.; Bourgeois, A.; El Manaa, W.; Duplan, E.; Chami, M.; Valverde, A.; Charlotte, B.; Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Checler, F. The eta-secretase-derived APP fragment etaCTF is localized in Golgi, endosomes and extracellular vesicles and contributes to Abeta production. Cell Mol Life Sci 2023, 80, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevalle, J.; Amoyel, A.; Robert, P.; Fournie-Zaluski, M.C.; Roques, B.; Checler, F. Aminopeptidase A contributes to the N-terminal truncation of amyloid beta-peptide. J Neurochem 2009, 109, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrau, D.; Dumanchin-Njock, C.; Ayral, E.; Vizzavona, J.; Farzan, M.; Boisbrun, M.; Fulcrand, P.; Hernandez, J.F.; Martinez, J.; Lefranc-Jullien, S.; et al. BACE1- and BACE2-expressing human cells: characterization of beta-amyloid precursor protein-derived catabolites, design of a novel fluorimetric assay, and identification of new in vitro inhibitors. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 25859–25866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisse, M.A.; Gandreuil, C.; Hernandez, J.F.; Martinez, J.; Checler, F.; Vincent, B. Design and characterization of a novel cellular prion-derived quenched fluorimetric substrate of alpha-secretase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 347, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Petit, A.; Kawarai, T.; Sunyach, C.; Alves da Costa, C.; Vincent, B.; Ring, S.; D’Adamio, L.; Shen, J.; Muller, U.; et al. Presenilin-dependent transcriptional control of the Abeta-degrading enzyme neprilysin by intracellular domains of betaAPP and APLP. Neuron 2005, 46, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.M.; Reiche, J.; Schmidt, V.; Gotthardt, M.; Spoelgen, R.; Behlke, J.; von Arnim, C.A.; Breiderhoff, T.; Jansen, P.; Wu, X.; et al. Neuronal sorting protein-related receptor sorLA/LR11 regulates processing of the amyloid precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 13461–13466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haass, C.; Lemere, C.A.; Capell, A.; Citron, M.; Seubert, P.; Schenk, D.; Lannfelt, L.; Selkoe, D. The Swedish mutation causes early-onset Alzheimer’s disease by b-secretase cleavage within the secretory pathway. Nature Medicine 1995, 1, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, C.A.; Sunyach, C.; Giaime, E.; West, A.; Corti, O.; Brice, A.; Safe, S.; Abou-Sleiman, P.M.; Wood, N.W.; Takahashi, H.; et al. Transcriptional repression of p53 by parkin and impairment by mutations associated with autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson’s disease. Nature cell biology 2009, 11, 1370–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenteany, G.; Schreiber, S.L. Lactacystin, proteasome function, and cell fate. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 8545–8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marambaud, P.; Ancolio, K.; Lopez-Perez, E.; Checler, F. Proteasome inhibitors prevent the degradation of familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin 1 and trigger increased Ab42 secretion by human cells. Mol. Medicine 1998, 4, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunys, J.; Kawarai, T.; Giaime, E.; Wilk, S.; Herrant, M.; Auberger, P.; St George-Hyslop, P.; Alves da Costa, C.; Checler, F. Study on the putative contribution of caspases and the proteasome to the degradation of Aph-1a and Pen-2. Neurodegener Dis 2007, 4, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checler, F. Processing of the b-amyloid precursor protein and its regulation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 1995, 65, 1431–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, J.A.; Turner, A.J. b-amyloid catabolism: roles for neprilysin (NEP) and other metallopeptidases. J. Neurochem. 2002, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miners, J.S.; Baig, S.; Palmer, J.; Palmer, L.E.; Kehoe, P.G.; Love, S. Abeta-degrading enzymes in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol 2008, 18, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirotani, K.; Tsubuki, S.; Iwata, N.; Takaki, Y.; Harigaya, W.; Maruyama, K.; Kiryu-Seo, S.; Kiyama, H.; Iwata, H.; Tomita, T.; et al. Neprilysin degrades both amyloid b peptides 1-40 and 1-42 most rapidly and efficiently among thiorphan- and phosphoramidon-sensitive endopeptidases. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 21895–21901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperstein, I.; Broersen, K.; Benilova, I.; Rozenski, J.; Jonckheere, W.; Debulpaep, M.; Vandersteen, A.; Segers-Nolten, I.; Van Der Werf, K.; Subramaniam, V.; et al. Neurotoxicity of Alzheimer’s disease Abeta peptides is induced by small changes in the Abeta42 to Abeta40 ratio. EMBO J 2010, 29, 3408–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, D.H.; Dobo, E.; Makifuchi, T.; Akiyama, H.; Kawakatsu, S.; Petit, A.; Checler, F.; Araki, W.; Takahashi, K.; Tabira, T. Apoptotic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease frequently show intracellular Abeta42 labeling. J Alzheimers Dis 2001, 3, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick, D.; Soreghan, B.; Kwon, M.; Kosmoski, J.; Knauer, M.; Henschen, A.; Yates, J.; Cotman, C.; Glabe, C. Assembly and aggregation properties of synthetic Alzheimer’s A4/b amyloid peptide analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasugi, N.; Tomita, T.; Hayashi, I.; Tsuruoka, M.; Niimura, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Thinakaran, G.; Iwatsubo, T. The role of presenilin cofactors in the g-secretase complex. Nature 2003, 422, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haass, C. Take five-BACE and the g-secretase quartet conduct Alzheimer’s amyloid b-peptide generation. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Strooper, B. Aph-1, Pen-2, and nicastrin with presenilin generate an active g-secretase complex. Neuron 2003, 38, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Strooper, B.; Saftig, P.; Craessaerts, K.; Vanderstichele, H.; Guhde, G.; Annaert, W.; Von Figura, K.; Van Leuven, F. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature 1998, 391, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, M.S.; Xia, W.; Ostaszewski, B.L.; Diehl, T.S.; Kimberly, W.T.; Selkoe, D.J. Two transmembrane aspartates in presenilin-1 required for presenilin endoproteolysis and gamma-secretase activity. Nature 1999, 398, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Checler, F. The physiology of the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain AICD. J Neurochem 2012, 120 (Suppl. 1), 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, S.L.; Vassar, R. The Alzheimer’s disease Beta-secretase enzyme, BACE1. Mol Neurodegener 2007, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flammang, B.; Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Sevalle, J.; Debayle, D.; Dabert-Gay, A.S.; Thevenet, A.; Lauritzen, I.; Checler, F. Evidence that the amyloid-beta protein precursor intracellular domain, AICD, derives from beta-secretase-generated C-terminal fragment. J Alzheimers Dis 2012, 30, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodger, Z.V.; Rajendran, L.; Trutzel, A.; Kohli, B.M.; Nitsch, R.M.; Konietzko, U. Nuclear signaling by the APP intracellular domain occurs predominantly through the amyloidogenic processing pathway. J Cell Sci 2009, 122, 3703–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyaev, N.D.; Kellett, K.A.; Beckett, C.; Makova, N.Z.; Revett, T.J.; Nalivaeva, N.N.; Hooper, N.M.; Turner, A.J. The Transcriptionally Active Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) Intracellular Domain Is Preferentially Produced from the 695 Isoform of APP in a {beta}-Secretase-dependent Pathway. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 41443–41454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citron, M.; Oltersdorf, T.; Haass, C.; McConlogue, L.; Hung, A.Y.; Seubert, P.; Vigo-Pelfrey, C.; Lieberburg, I.; Selkoe, D.J. Mutation of the b-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer’s disease increases b-protein production. Nature 1992, 360, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, R.G.; Squazzo, S.L.; Koo, E.H. Enhanced release of amyloid b-protein from codon 670/671 “Swedish” mutant b-amyloid precursor protein occurs in both secretory and endocytic pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 9100–9107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vingtdeux, V.; Hamdane, M.; Loyens, A.; Gele, P.; Drobeck, H.; Begard, S.; Galas, M.C.; Delacourte, A.; Beauvillain, J.C.; Buee, L.; et al. Alkalizing drugs induce accumulation of amyloid precursor protein by-products in luminal vesicles of multivesicular bodies. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 18197–18205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritzen, I.; Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Bourgeois, A.; Pagnotta, S.; Biferi, M.G.; Barkats, M.; Lacor, P.; Klein, W.; Bauer, C.; Checler, F. Intraneuronal aggregation of the beta-CTF fragment of APP (C99) induces Abeta-independent lysosomal-autophagic pathology. Acta Neuropathol 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalivaeva, N.N.; Fisk, L.R.; Belyaev, N.D.; Turner, A.J. Amyloid-degrading enzymes as therapeutic targets in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2008, 5, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, L.B.; Rodgers, D.W. Neprilysin and amyloid beta peptide degradation. Curr Alzheimer Res 2008, 5, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, L.; Madsen, P.; Jacobsen, C.; Nielsen, M.S.; Gliemann, J.; Petersen, C.M. Activation and functional characterization of the mosaic receptor SorLA/LR11. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 22788–22796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenteany, G.; Standaert, R.; Lane, W.S.; Choi, S.; Corey, E.J.; Schreiber, S.L. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science 1995, 268, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checler, F.; Alves da Costa, C.; Ancolio, K.; Lopez-Perez, E.; Marambaud, P. Role of the Proteasome in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica Biophysica Acta 2000, 1502, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louwersheimer, E.; Ramirez, A.; Cruchaga, C.; Becker, T.; Kornhuber, J.; Peters, O.; Heilmann, S.; Wiltfang, J.; Jessen, F.; Visser, P.J. , et al. The influence of genetic variants in SORL1 gene on the manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2015, 36, 1605 e1613-1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| hSORL1 point mutation (nucleotide) |

Forward Primer | HSorLA point mutation (amino acid) |

|---|---|---|

| A422G | 5′-GTG-TCT-TAC-GAC-TGT-GGA-AAA-TCA-TTC-3′ | Y141C |

| G1531C | 5′-GGC-TCA-GTG-CGA-AAG-AAC-TTG-GCT-AGC-AA-3′ | G511R |

| A2771G | 5′-GAT-GTG-AAG-TGG-CCC-AGT-GGC-ATC-TCT-GTG-3′ | N924S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).