Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

30 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

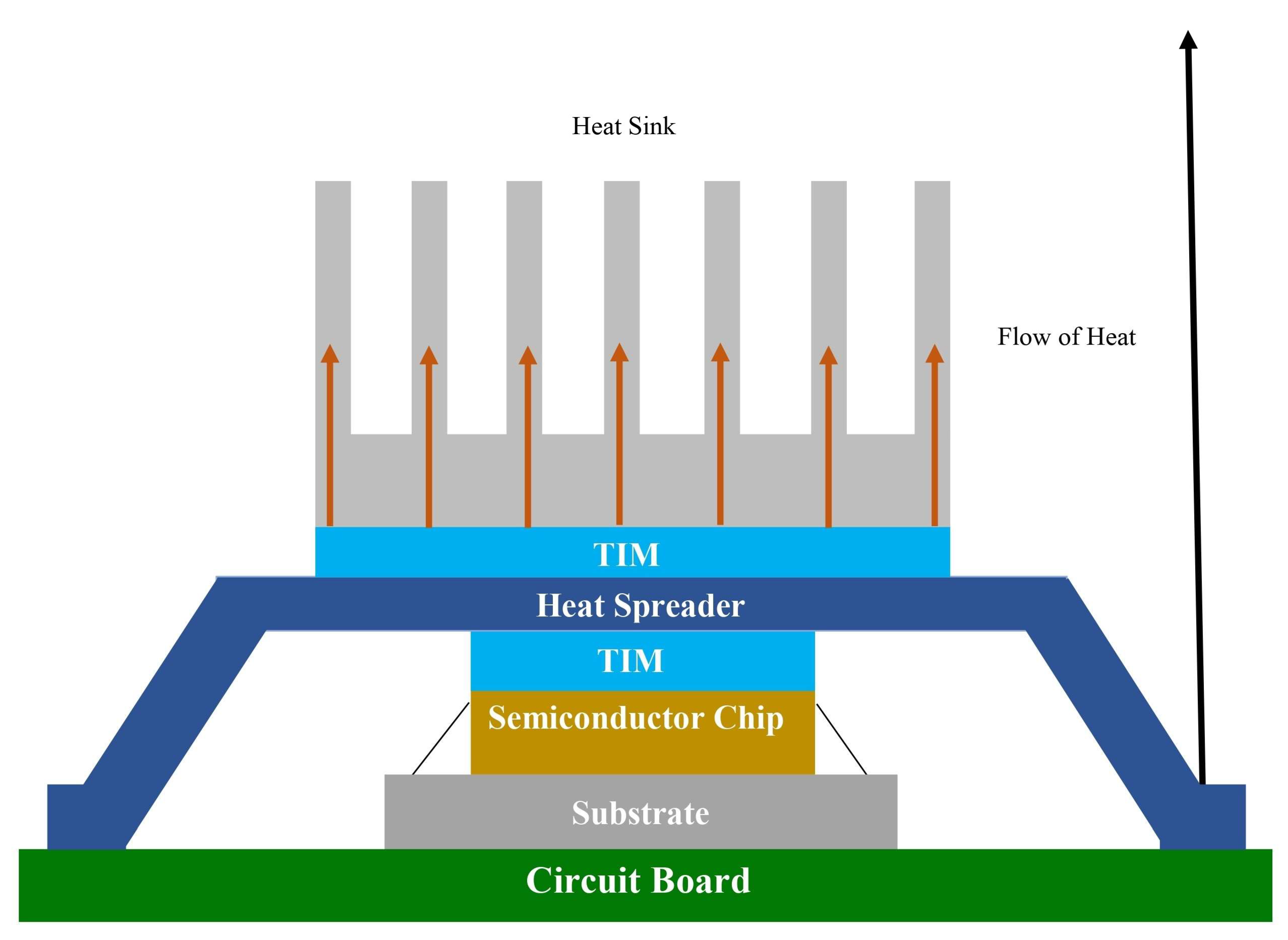

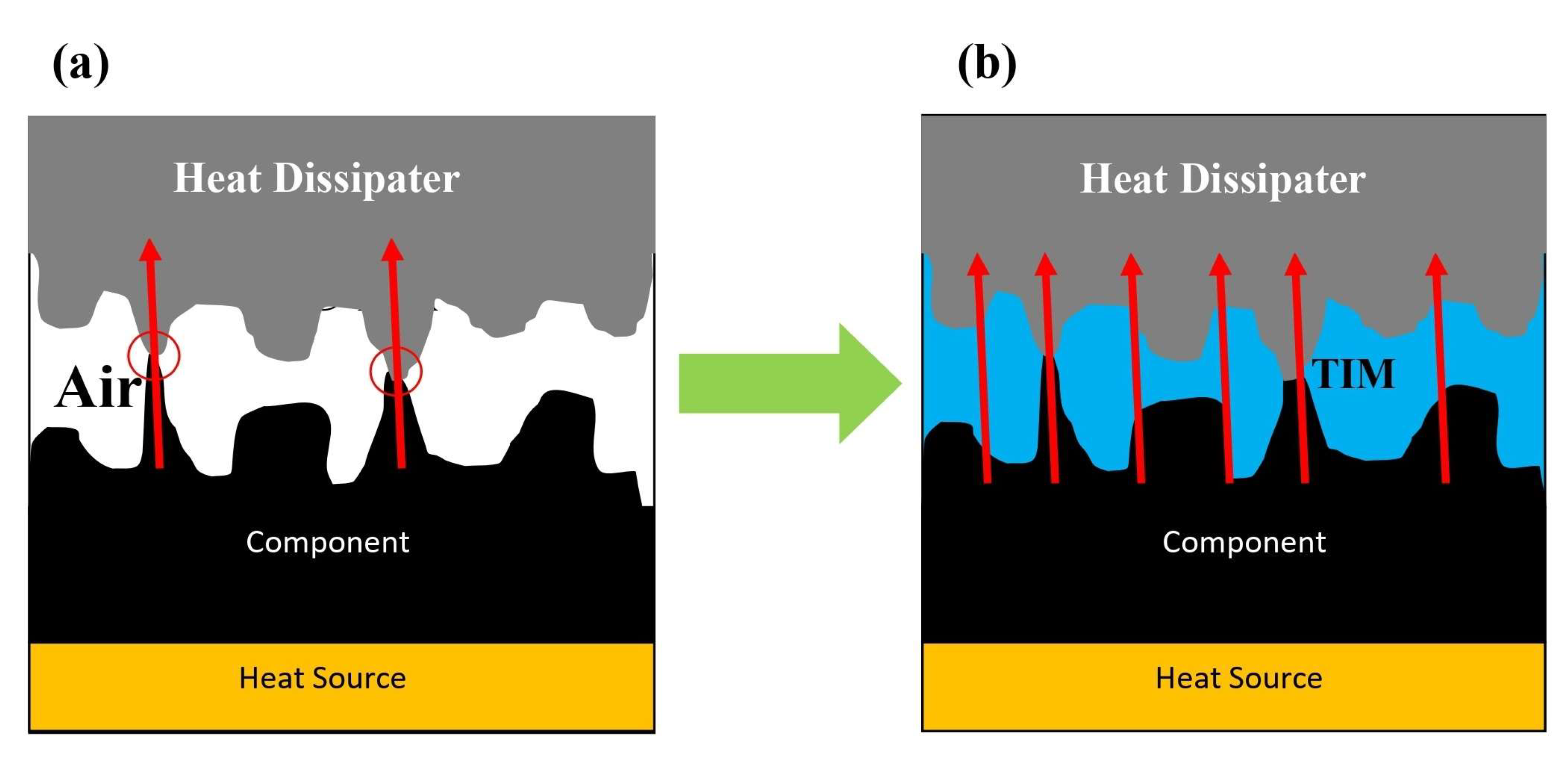

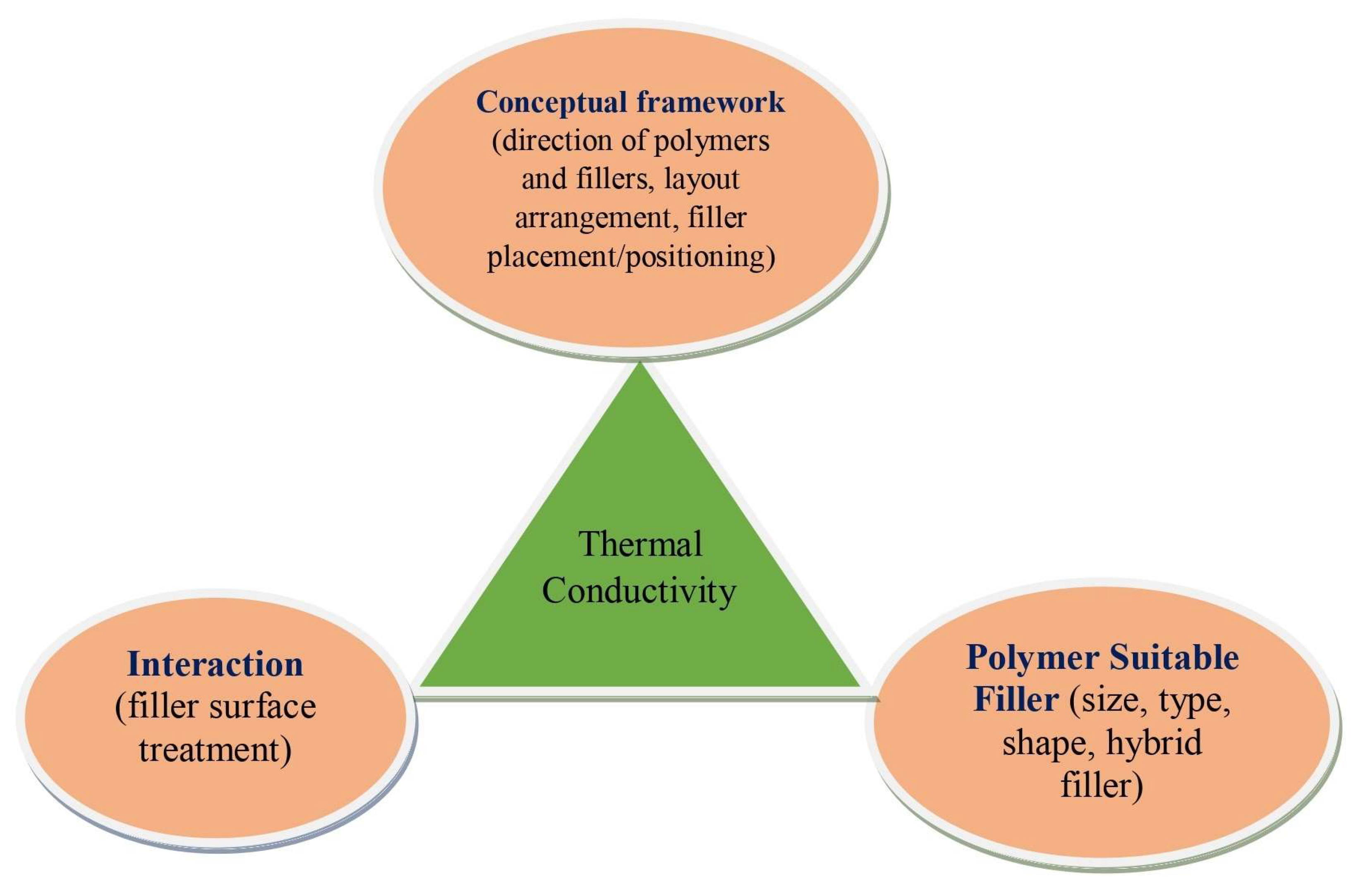

2. Background

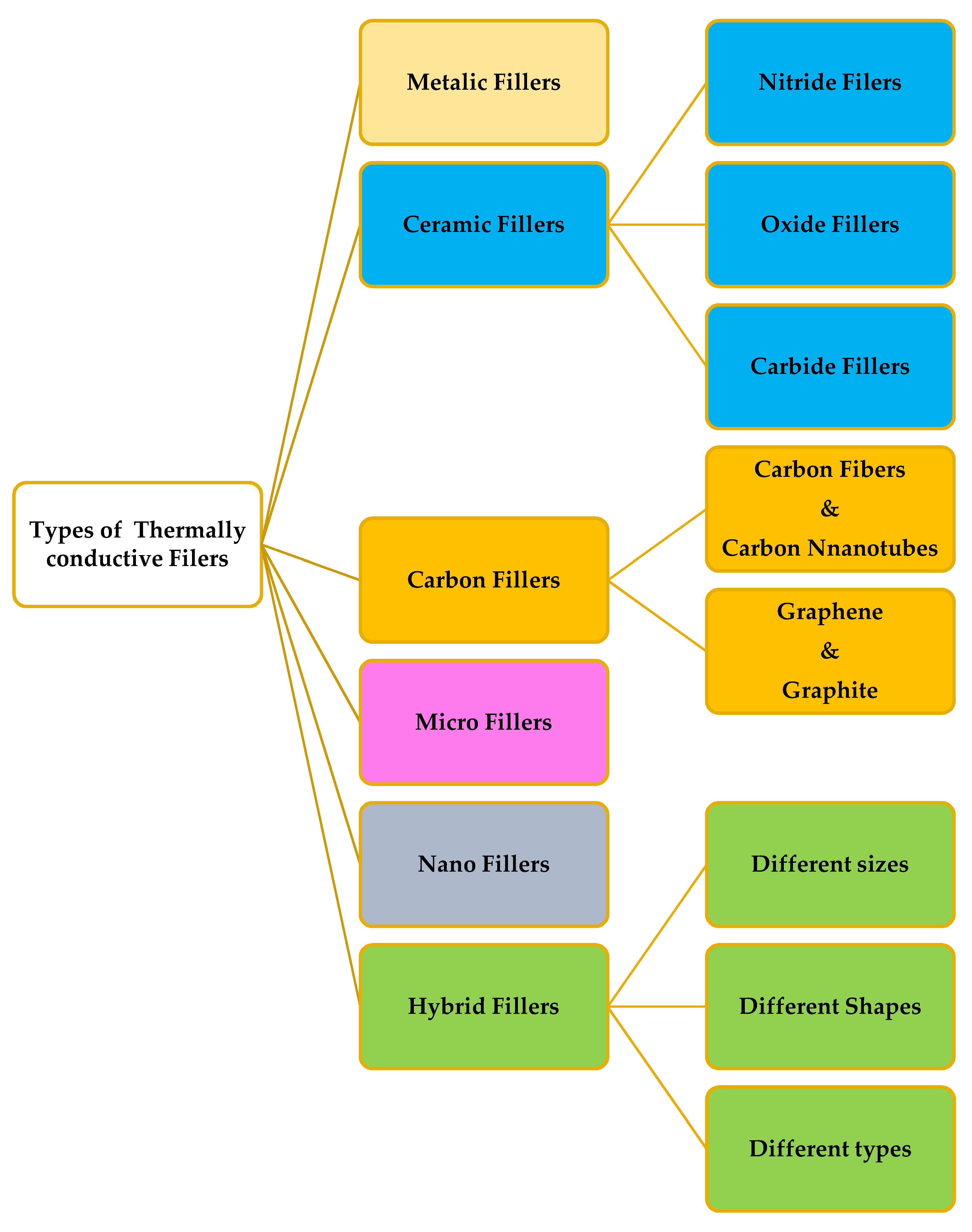

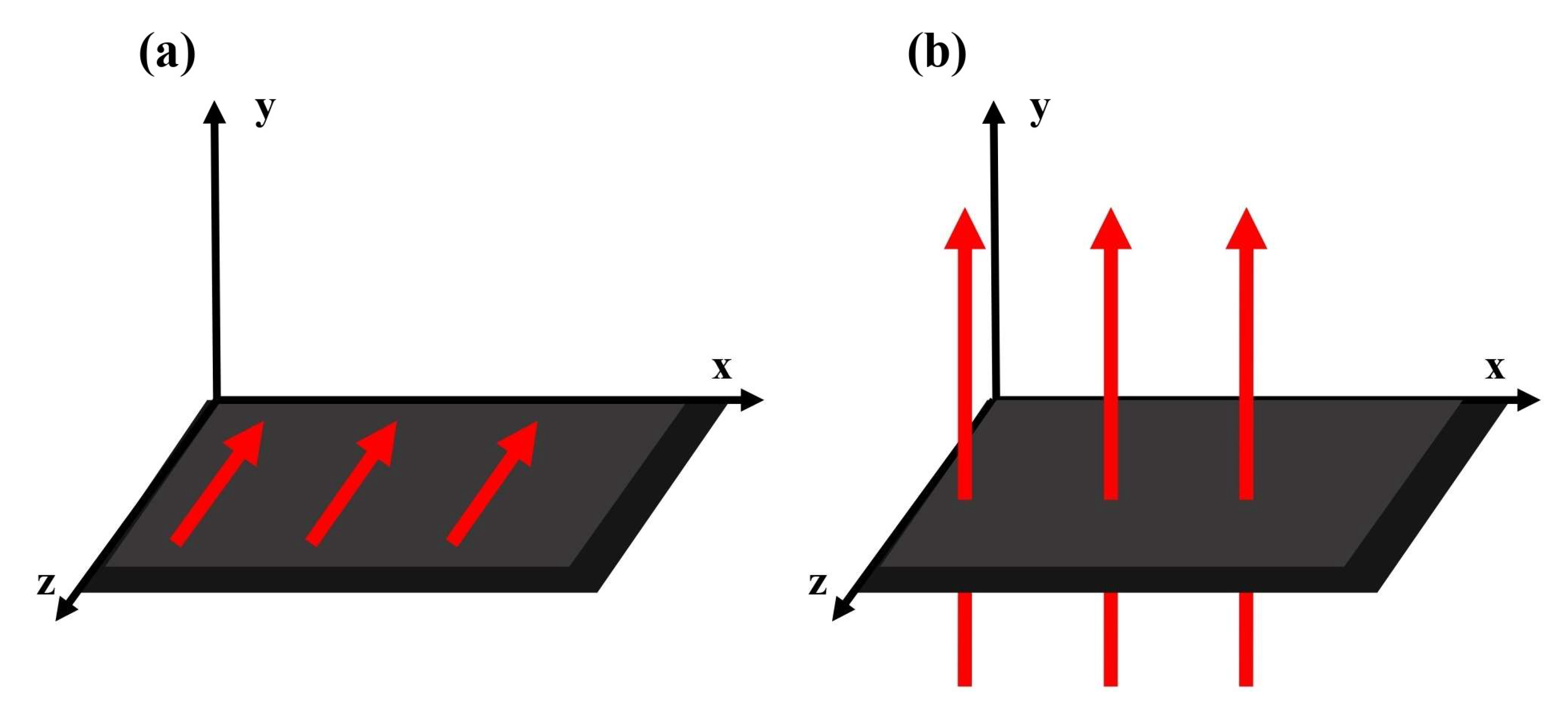

3. Through-Plane Thermal Conductivity (TPTC) of polymer composites with different fillers

3.1. Thermal Conductivity with metallic fillers

3.2. Thermal Conductivity with ceramic fillers

- Oxide fillers

- Nitride fillers

- Carbide fillers

3.2.1. Oxide Fillers

3.2.2. Nitride Fillers

3.2.3. Carbide Fillers

3.3. Thermal Conductivity with Carbon fillers

3.3.1. Carbon Fibers (CFs) and Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

3.3.2. Graphene and Graphite

3.4. Thermal Conductivity with micro fillers

3.5. Thermal Conductivity with nano fillers

3.6. Thermal Conductivity with hybrid fillers

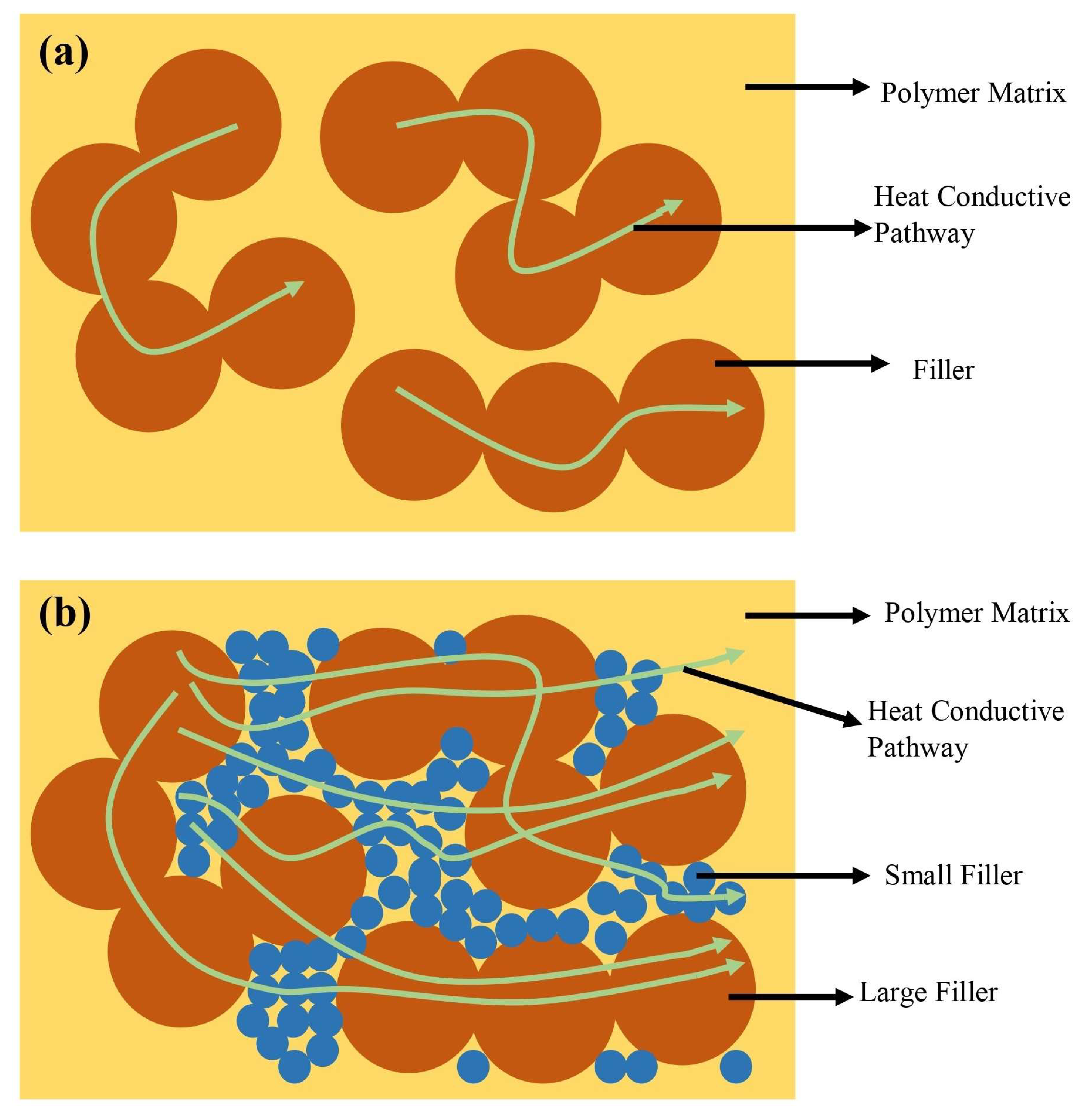

3.6.1. Mixture of fillers with different sizes

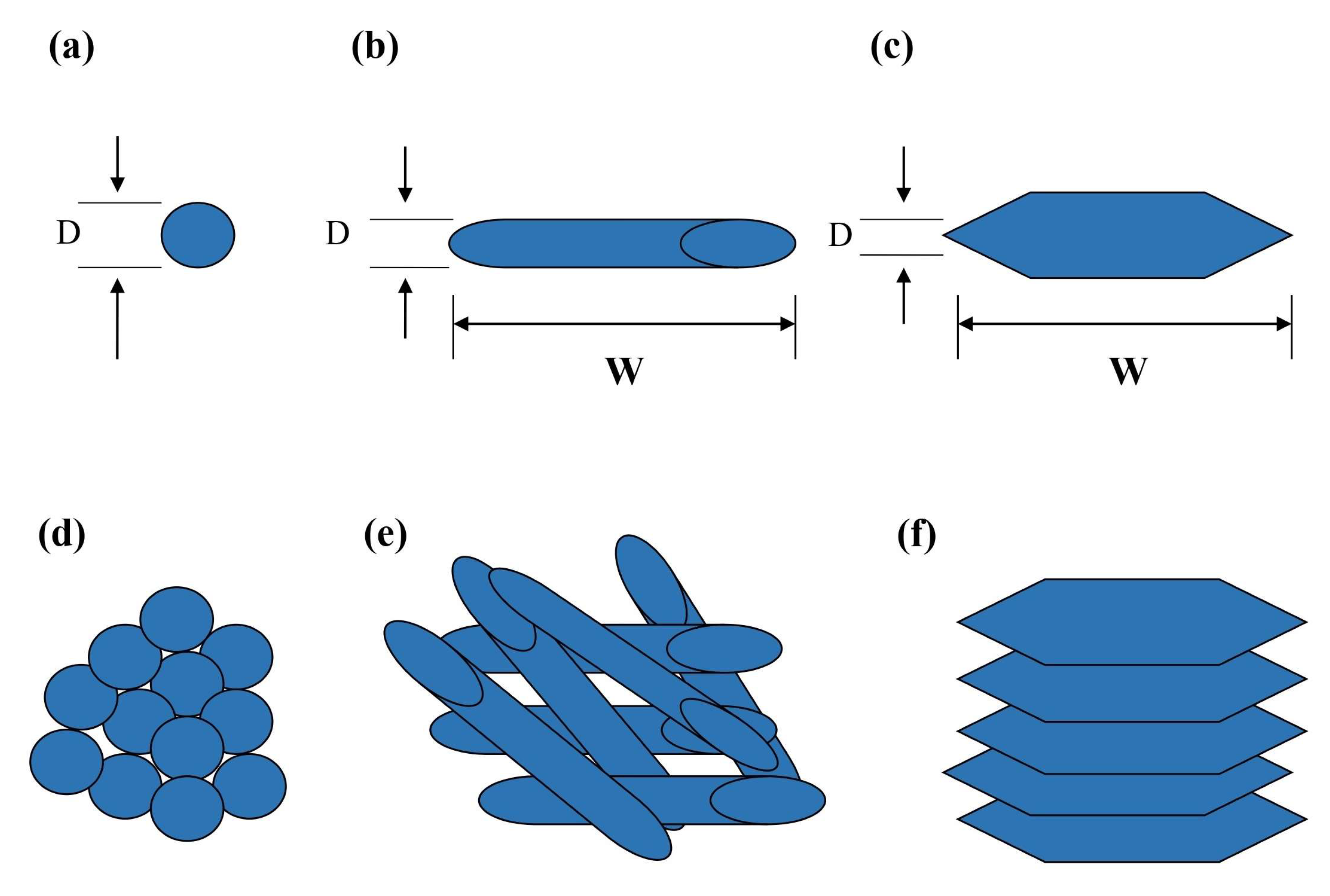

3.6.2. Mixture of fillers with different shapes

- (1)

- zero-dimensional (0D),

- (2)

- One-dimensional (1D),

- (3)

- Two-dimensional (2D).

3.6.3. Mixture of different types of fillers

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Symbols

Abbreviations

References

- Vadivelu, M.A.; Kumar, C.R.; Joshi, G.M. Polymer composites for thermal management: a review. Compos. Interfaces 2016, 23, 847–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsissou, R.; Seghiri, R.; Benzekri, Z.; Hilali, M.; Rafik, M.; Elharfi, A. Polymer composite materials: A comprehensive review. Compos. Struct. 2021, 262, 113640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yu, D.; Kelkar, A.D.; Zhang, L. Electrospun nanofiber: Emerging reinforcing filler in polymer matrix composite materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 75, 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslahi, N.; Mahmoodi, A.; Mahmoudi, N.; Zandi, N.; Simchi, A. Processing and Properties of Nanofibrous Bacterial Cellulose-Containing Polymer Composites: A Review of Recent Advances for Biomedical Applications. Polym. Rev. 2019, 60, 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, D.G.; Kandasubramanian, B. Progress in the Development of Intrinsically Conducting Polymer Composites as Biosensors. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2019, 220, 1800561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasrado, D.; Ahankari, S.; Kar, K. Nanocellulose-based polymer composites for energy applications—a review. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2020, 137, 48959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Fatimah Athiyah, S.; Shazleen, S.S.; Rafiqah, S.A.; Harussani, M.M.; Kamarudin, S.H.; Razman, M.R.; Rahmah, M.; Zainudin, E.S.; et al. A Review on Mechanical Performance of Hybrid Natural Fiber Polymer Composites for Structural Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ruan, K.; Shi, X.; Yang, X.; Gu, J. Factors affecting thermal conductivities of the polymers and polymer composites: A review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 193, 108134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakooti, M.H.; Kazem, N.; Yan, J.; Pan, C.; Markvicka, E.J.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Majidi, C. Liquid Metal Supercooling for Low-Temperature Thermoelectric Wearables. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1906098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Guo, P.; Zhu, J. Thermal management of electronic devices using pin-fin based cascade microencapsulated PCM/expanded graphite composite. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 149, 119199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Thermal management and temperature uniformity enhancement of electronic devices by micro heat sinks: A review. Energy 2021, 216, 119223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xie, H.; Yu, W. A critical review of the preparation strategies of thermally conductive and electrically insulating polymeric materials and their applications in heat dissipation of electronic devices. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Li, S.; Ruan, X.; Bao, H. Comprehensive first-principles analysis of phonon thermal conductivity and electron-phonon coupling in different metals. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 144306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Feng, Y.; Feng, W. Three-dimensional interconnected networks for thermally conductive polymer composites: Design, preparation, properties, and mechanisms. Mater. Sci. Eng. R: Rep. 2020, 142, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Puthirath, A.B.; Adumbumkulath, A.; Tsafack, T.; Robatjazi, H.; Barnes, M.; Wang, Z.; Kommandur, S.; Susarla, S.; Sajadi, S.M.; et al. Fiber Reinforced Layered Dielectric Nanocomposite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1900056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Huang, C.; Wang, L.; Liang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Fei, W.; Li, Y. Recent Progress in Graphene/Polymer Nanocomposites. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2001105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmee, S.; Omar, G.; Othaman, S.S.C.; Masripan, N.A.; Hamid, H.A. Interface thermal resistance and thermal conductivity of polymer composites at different types, shapes, and sizes of fillers: A review. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 2629–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yan, T.; Kuai, Z.; Pan, W. Thermal conductivity enhancement on phase change materials for thermal energy storage: A review. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 25, 251–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zeng, X.-L.; Tan, L.-Y.; Yao, Y.-M.; Zhu, D.-L.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.-B.; Wong, C.-P. Three-dimensional interconnected graphene microsphere as fillers for enhancing thermal conductivity of polymer. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 368, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemath, M.; Rangappa, S.M.; Kushvaha, V.; Dhakal, H.N.; Siengchin, S. A comprehensive review on mechanical, electromagnetic radiation shielding, and thermal conductivity of fibers/inorganic fillers reinforced hybrid polymer composites. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 3940–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Gao, B.; Wang, M.; Yuan, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhao, J.; Feng, Y. Strategies for enhancing thermal conductivity of polymer-based thermal interface materials: a review. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 1064–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.O. Thermally conductive polymer composites for electronic packaging applications; University of Toronto: Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

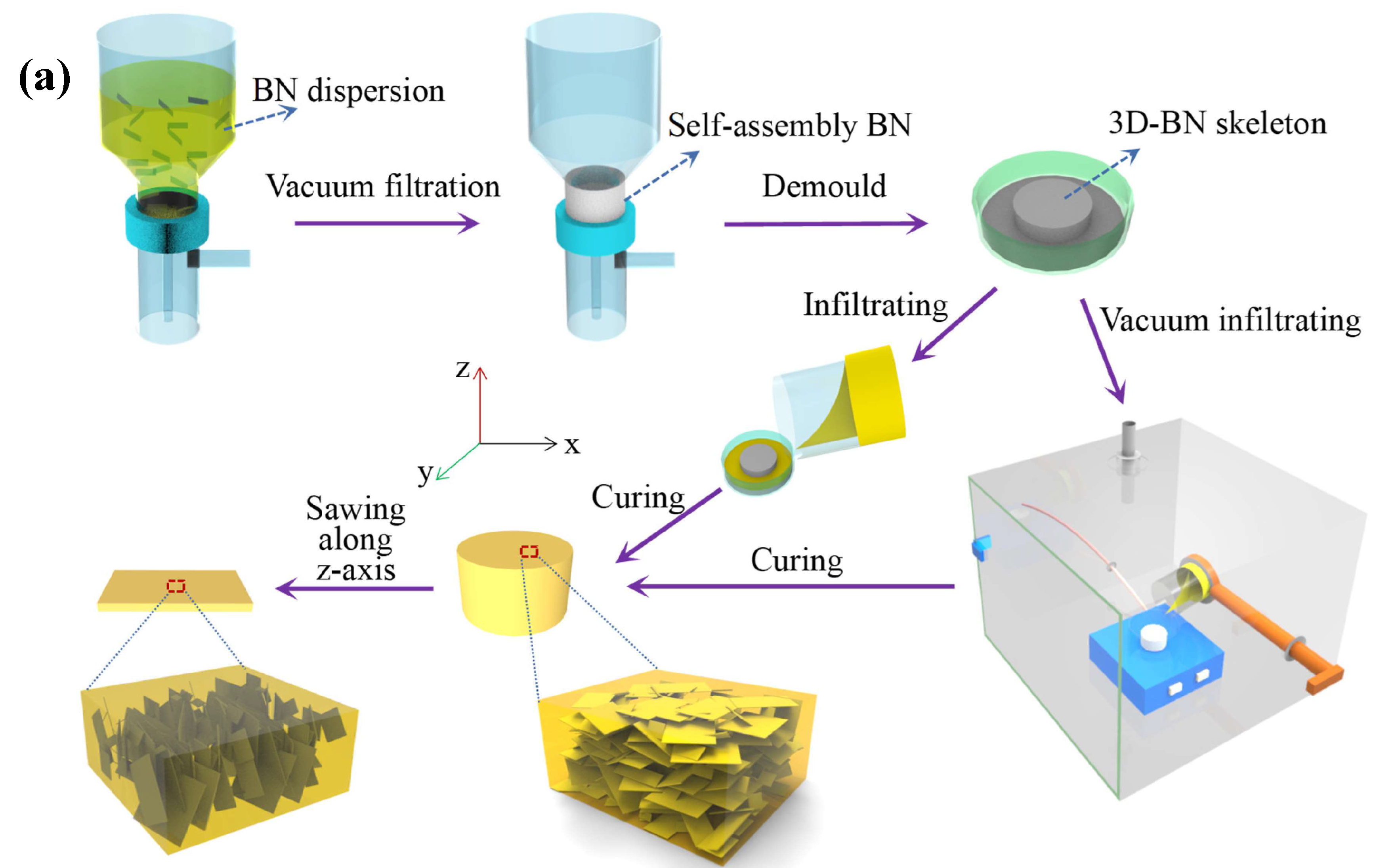

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Yang, G.; Li, M.; Wu, G. The Investigation of the Effect of Filler Sizes in 3D-BN Skeletons on Thermal Conductivity of Epoxy-Based Composites. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D. Performance of Thermal Interface Materials. Small 2022, 18, e2200693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.-W.; Park, M.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.I.; Yoon, H.G. Enhanced thermal conductivity of polymer composites filled with hybrid filler. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006, 37, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.; Lee, S.; Xu, C.; Jan, A.A.; Baik, S. Significantly enhanced phonon mean free path and thermal conductivity by percolation of silver nanoflowers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 2453–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigg, D. Thermally conductive polymer compositions. Polymer composites 1986, 7, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Bai, L.; Tian, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, F. Recent progress of thermal conductive ploymer composites: Al2O3 fillers, properties and applications. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 152, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, C. Thermal conductivity of polymers. Polymer 1977, 18, 984–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloukian, Y. and C. Ho, Thermophysical properties of selected aerospace materials. Part 2. Thermophysical properties of seven materials. 1977, THERMOPHYSICAL AND ELECTRONIC PROPERTIES INFORMATION ANALYSIS CENTER ….

- Kinoshita, M.; Terai, R.; Haidai, H. Thermal Conductivity of Glass Copper-Composite. J. Ceram. Assoc. Jpn. 1980, 88, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agari, Y.; Ueda, A.; Tanaka, M.; Nagai, S. Thermal conductivity of a polymer filled with particles in the wide range from low to super-high volume content. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1990, 40, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agari, Y.; Uno, T. Thermal conductivity of polymer filled with carbon materials: Effect of conductive particle chains on thermal conductivity. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1985, 30, 2225–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigg, D.M.; Bradbury, E.J. Conductive polymeric composites from short conductive fibers. In Conductive Polymers; Springer, 1981; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Ginzburg, V.V.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Huang, Y.; Du, L.; Chen, B. Thermal conductivity of polymer-based composites: Fundamentals and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 59, 41–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.D.; Kazem, N.; Powell-Palm, M.J.; Huang, X.; Sun, W.; Malen, J.A.; Majidi, C. High thermal conductivity in soft elastomers with elongated liquid metal inclusions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 2143–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.-C.; Jin, Y.-F.; Ren, J.-W.; Zhao, L.-H.; Yan, D.-X.; Li, Z.-M. Highly thermally conductive liquid metal-based composites with superior thermostability for thermal management. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 2904–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Yao, Y.; Gong, Z.; Wang, F.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.; Wong, C. Ice-Templated Assembly Strategy to Construct 3D Boron Nitride Nanosheet Networks in Polymer Composites for Thermal Conductivity Improvement. Small 2015, 11, 6205–6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Dong, J.; Yang, G.; Su, F.; Chang, B.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Y.-C.; Guo, Z. Ice template method assists in obtaining carbonized cellulose/boron nitride aerogel with 3D spatial network structure to enhance the thermal conductivity and flame retardancy of epoxy-based composites. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2021, 5, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

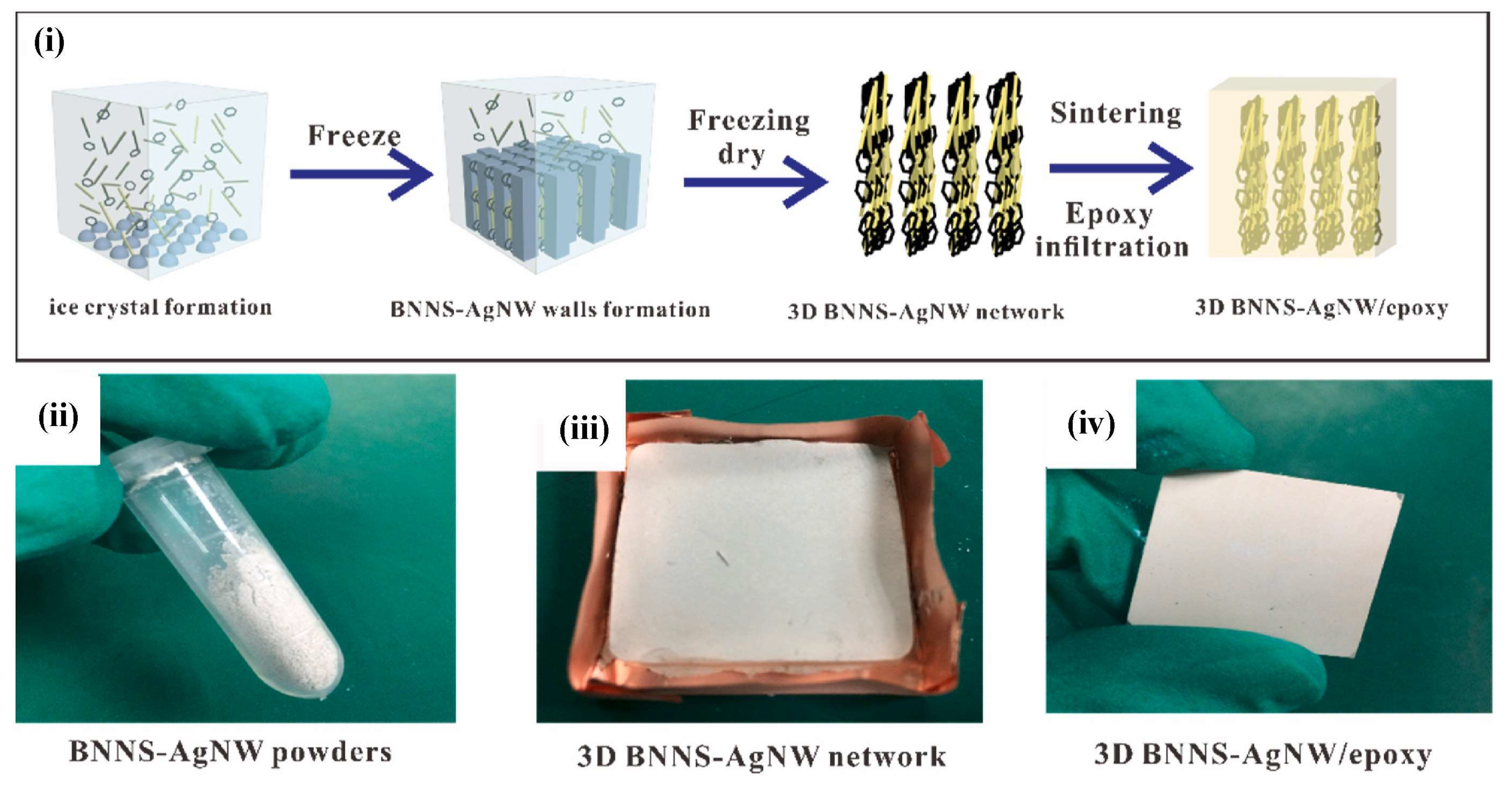

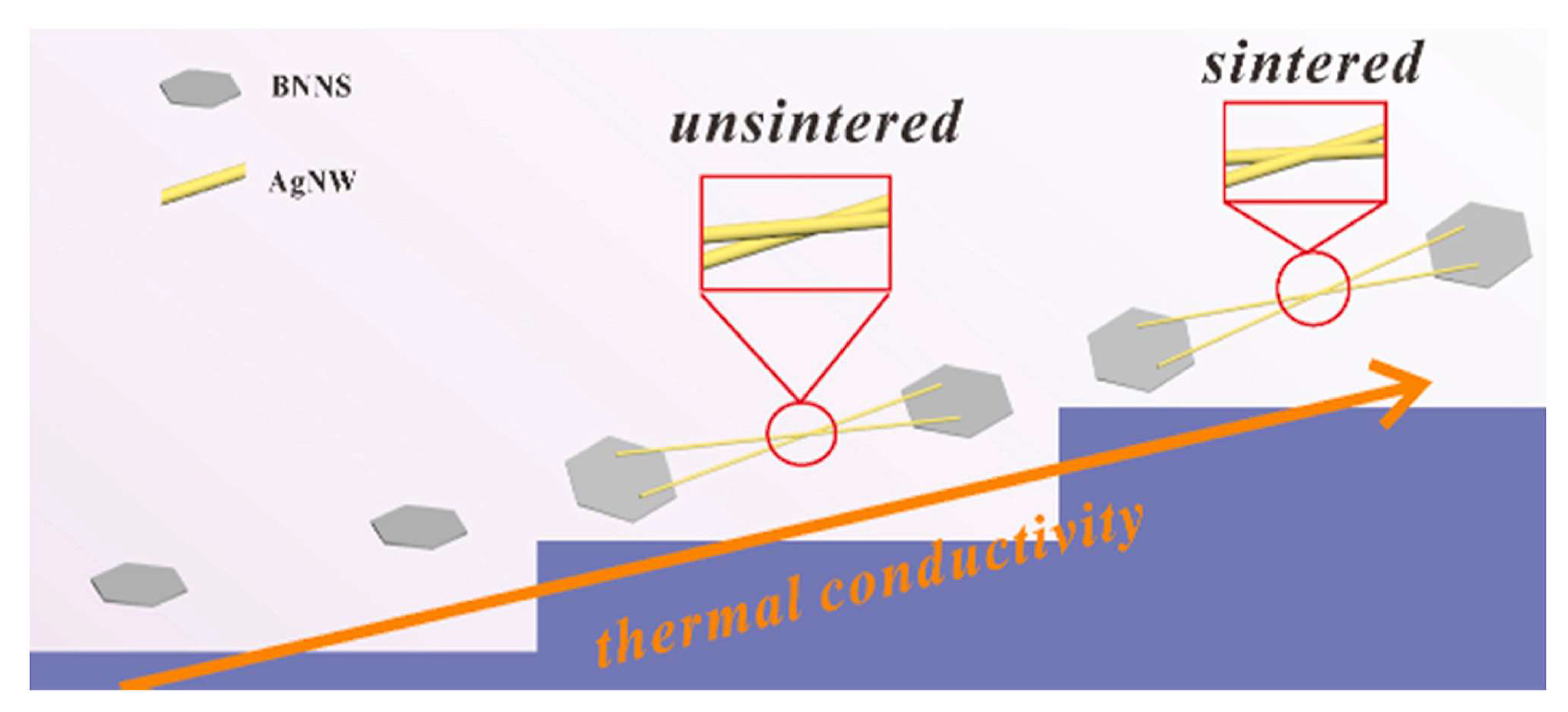

- Li, H.; Fu, C.; Chen, N.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; Du, G.; Ren, L.; Zeng, X.; Sun, R. Ice-templated assembly strategy to construct three-dimensional thermally conductive networks of BN nanosheets and silver nanowires in polymer composites. Compos. Commun. 2021, 25, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lim, J.S.K.; Yan, W.; Guo, F.; Liang, Y.N.; Chen, H.; Lambourne, A.; Hu, X.M. Salt Template Assisted BN Scaffold Fabrication toward Highly Thermally Conductive Epoxy Composites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 16987–16996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Gamage, G.A.; Ding, Z.; Chen, K.; Tian, F.; Qian, X.; Zhou, J.; Lee, H.; Zhou, J.; Shi, L.; et al. High ambipolar mobility in cubic boron arsenide. Science 2022, 377, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, Q.; Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, P.Y.; Cahill, D.G.; Lv, B. High thermal conductivity in cubic boron arsenide crystals. Science 2018, 361, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.R.J.; Alahyari, A.A.; Eastman, S.A.; Thibaud-Erkey, C.; Johnston, S.; Sobkowicz, M.J. Review of polymers for heat exchanger applications: Factors concerning thermal conductivity. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 113, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Kim, M.J.; Zhang, H. Tailoring interface structure and enhancing thermal conductivity of Cu/diamond composites by alloying boron to the Cu matrix. Mater. Charact. 2019, 152, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; et al. Epsilon-negative BaTiO3/Cu composites with high thermal conductivity and yet low electrical conductivity. Journal of Materiomics, 2020, 6, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shi, S.; Tang, B.; Chen, J.; Shan, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Sun, K.; Yang, K.; et al. Achieving highly thermal conductivity of polymer composites by adding hybrid silver–carbon fiber fillers. Compos. Commun. 2022, 31, 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

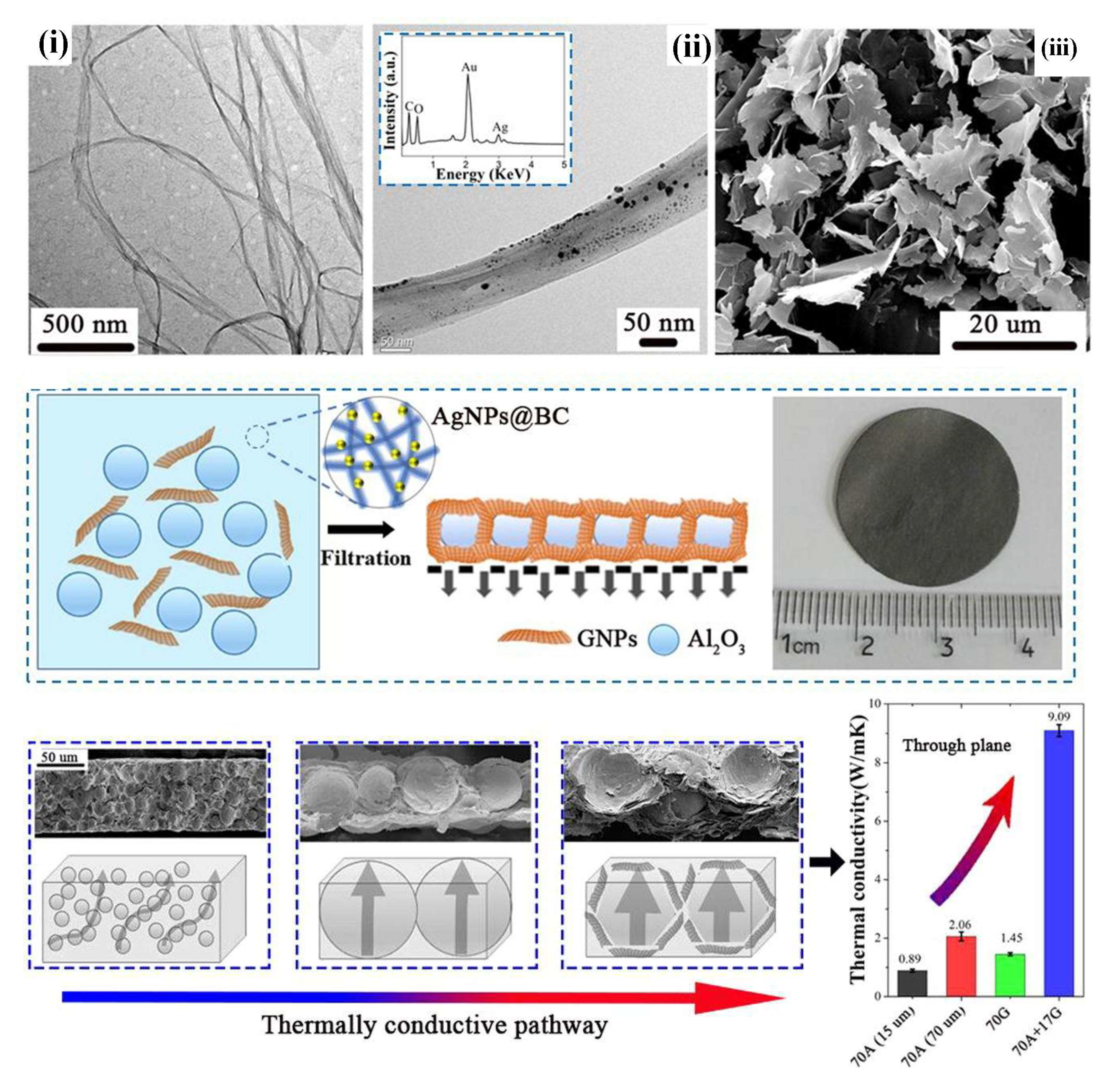

- Feng, C.-P.; Chen, L.-B.; Tian, G.-L.; Bai, L.; Bao, R.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Ke, K.; Yang, M.-B.; Yang, W. Robust polymer-based paper-like thermal interface materials with a through-plane thermal conductivity over 9 Wm−1K−1. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 392, 123784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.; Bok, G.; Park, S.-D.; Kim, Y. Thermally conductive hexagonal boron nitride/spherical aluminum oxide hybrid composites fabricated with epoxyorganosiloxane. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Song, B.; Ravichandran, N.K.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, X.; Lee, H.; Sun, H.; Li, S.; Gamage, G.A.G.U.; Tian, F.; et al. Ultrahigh thermal conductivity in isotope-enriched cubic boron nitride. Science 2020, 367, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J. Improved through-plane thermal conductivity of 3D structured composites via BN alignment and AlN surface modification. Compos. Commun. 2021, 28, 100935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Shen, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, D.; Zheng, Q.; Yang, J.; Jia, B.; Lau, A.K.T.; Kim, J. Highly Thermally Conductive Dielectric Nanocomposites with Synergistic Alignments of Graphene and Boron Nitride Nanosheets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1910826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y. Improvement in thermal conductivity of through-plane aligned boron nitride/silicone rubber composites. Mater. Des. 2019, 165, 107580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Bai, X.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Oriented BN/Silicone rubber composite thermal interface materials with high out-of-plane thermal conductivity and flexibility. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 152, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Bai, X.; Li, J.; Han, M.; Yao, Y.; Zeng, X.; Sun, R.; Zhang, P. Facile fabrication of large-area BN films for thermal management in flexible electronics. Compos. Commun. 2022, 36, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Wang, H.; He, J.; Guo, Y.; Qu, Q.; Tian, X. Fabrication of Thermal Conductivity Enhanced Polymer Composites by Constructing an Oriented Three-Dimensional Staggered Interconnected Network of Boron Nitride Platelets and Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 36342–36351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, L.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Hu, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q. Flexible and quasi-isotropically thermoconductive polyimide films by guided assembly of boron nitride nanoplate/boron nitride flakes for microelectronic application. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Xie, W.; Ge, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, W.; Xia, H.; Wang, B.; Jin, H.; Gao, N.; Shi, Z. Enhanced thermal conductivity of epoxy composites by constructing aluminum nitride honeycomb reinforcements. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 199, 108304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Sun, J.; Yao, Y.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.-B.; Wong, C.-P. A Combination of Boron Nitride Nanotubes and Cellulose Nanofibers for the Preparation of a Nanocomposite with High Thermal Conductivity. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 5167–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; et al. Anisotropic thermal conductive composite by the guided assembly of boron nitride nanosheets for flexible and stretchable electronics. Advanced Functional Materials, 2019, 29, 1902575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, P. Cellulose Nanofiber Supported 3D Interconnected BN Nanosheets for Epoxy Nanocomposites with Ultrahigh Thermal Management Capability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1604754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Du, G.; Gao, W.; Bai, H. An Anisotropically High Thermal Conductive Boron Nitride/Epoxy Composite Based on Nacre-Mimetic 3D Network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1900412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; et al. Highly thermoconductive, thermostable, and super-flexible film by engineering 1D rigid rod-like aramid nanofiber/2D boron nitride nanosheets. Advanced Materials, 2020, 32, 1906939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Liao, P.; Du, R.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, F.; Fu, Q. Preparation of a thermally conductive biodegradable cellulose nanofiber/hydroxylated boron nitride nanosheet film: the critical role of edge-hydroxylation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 11863–11873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, P. Preparation of Highly Thermally Conductive Polymer Composite at Low Filler Content via a Self-Assembly Process between Polystyrene Microspheres and Boron Nitride Nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 19934–19944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Sun, J.; Zeng, X.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.; Wong, C. Construction of 3D Skeleton for Polymer Composites Achieving a High Thermal Conductivity. Small 2018, 14, e1704044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Hu, R.; Chen, M.; Dong, J.; Xiao, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H. 3D boron nitride foam filled epoxy composites with significantly enhanced thermal conductivity by a facial and scalable approach. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 397, 125447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; et al. Quasi-Isotropically Thermal Conductive, Highly Transparent, Insulating and Super-Flexible Polymer Films Achieved by Cross Linked 2D Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets. Small, 2021, 17, 2101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; et al. Achieving significant thermal conductivity enhancement via an ice-templated and sintered BN-SiC skeleton. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2019, 12, 2892–2902. [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, O.; Richards, N. Heat-affected zone cracking in welded nickel superalloys. In Welding and Joining of Aerospace Materials; Elsevier, 2012; pp. 142–177. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, M.C.; Choi, W.-K.; Lee, S.G.; Park, P.J.; Kim, D.H.; Islam, A.; Kim, S.-R. High Thermal Conductivity Enhancement of Polymer Composites with Vertically Aligned Silicon Carbide Sheet Scaffolds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 23388–23398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Lv, L.; Lu, J.; Hou, H.; Yan, Q.; Alam, F.E.; Li, Y.; Zeng, X.; Yu, J.; Wei, Q.; et al. A Paper-Like Inorganic Thermal Interface Material Composed of Hierarchically Structured Graphene/Silicon Carbide Nanorods. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, Y. Vertically aligned silicon carbide nanowires/reduced graphene oxide networks for enhancing the thermal conductivity of silicone rubber composites. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 133, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Yang, G.; Abo-Dief, H.M.; Dong, J.; Su, F.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Bin Xu, B.; Murugadoss, V.; Naik, N.; et al. Vertically Aligned Silicon Carbide Nanowires/Boron Nitride Cellulose Aerogel Networks Enhanced Thermal Conductivity and Electromagnetic Absorbing of Epoxy Composites. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Liu, J.; Cao, M.; Li, M.; Cui, Y.; Li, B. Vertically oriented boron nitride/silicon carbide scaffold for thermal-conductive and electrical-insulating phase change composites. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 168, 107460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liao, X.; Guo, X.; Cheng, S.; Huang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.-A. Improving thermal conductivity of epoxy-based composites by diamond-graphene binary fillers. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 126, 109141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Dai, W.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Kong, X.; Xu, K.; Yang, R.; Gong, P.; et al. Ultrahigh thermal conductive polymer composites by the 3D printing induced vertical alignment of carbon fiber. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 10971–10983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, Y.; Matsumoto, N.; Isono, T.; Behnia, K. Phonon hydrodynamics and ultrahigh–room-temperature thermal conductivity in thin graphite. Science 2020, 367, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, V.-T.; Kwon, B.-S.; Sung, J.-W.; Choe, H.-S.; Oh, S.-W.; Lee, S.-M.; Kweon, J.-H.; Nam, Y.-W. Postprocessing method-induced mechanical properties of carbon fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composites. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2023, 36, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Dai, W.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Kong, X.; Xu, K.; Yang, R.; Gong, P.; et al. Correction: Ultrahigh thermal conductive polymer composites by the 3D printing induced vertical alignment of carbon fiber. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 11534–11534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Qian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Gong, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y. Thermal conductivity enhancement of carbon fiber/epoxy composites via constructing three-dimensionally aligned hybrid thermal conductive structures on fiber surfaces. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 231, 109800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Shang, T.; Ren, L.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xie, J.; Zhang, B.; Zeng, X.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.-B.; et al. Through-plane assembly of carbon fibers into 3D skeleton achieving enhanced thermal conductivity of a thermal interface material. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 380, 122550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ding, D.; Guo, X.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cai, W.; Zhang, X.-A. Improving through-plane thermal conductivity of PDMS-based composites using highly oriented carbon fibers bridged by Al2O3 particles. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 230, 109717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F.; Qin, M.; Zhang, F.; Yu, H.; Gao, L.; Lv, P.; Wei, W.; Feng, Y.; Feng, W. High cross-plane thermally conductive hierarchical composite using graphene-coated vertically aligned carbon nanotubes/graphite. Carbon 2019, 149, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ali, Z.; Wei, X.; Li, L.; Song, G.; Hou, X.; Do, H.; Greer, J.C.; Pan, Z.; Lin, C.-T.; et al. Stress induced carbon fiber orientation for enhanced thermal conductivity of epoxy composites. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2020, 208, 108599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Chen, Y.; Dai, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Lin, C.-T.; Nishimura, K.; Jiang, N.; Yu, J. Highly thermal conductive polymer composites via constructing micro-phragmites communis structured carbon fibers. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 375, 121921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xue, S.; Chen, F.; Fu, Q. An efficient thermal interface material with anisotropy orientation and high through-plane thermal conductivity. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 231, 109784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakooti, S.; et al. High thermo-mechanical stability in polybenzoxazine aerogels. In ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Balandin, A.A. Phononics of Graphene and Related Materials. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5170–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Yuan, Q.; Qiu, M.; Yu, J.; Jiang, N.; Lin, C.-T.; Dai, W. Rational design of graphene/polymer composites with excellent electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness and high thermal conductivity: a mini review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 117, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yan, Q.; Lv, L.; Tan, X.; Ying, J.; Yang, K.; Yu, J.; Du, S.; Wei, Q.; Xiang, R.; et al. Lightweight thermal interface materials based on hierarchically structured graphene paper with superior through-plane thermal conductivity. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 419, 129609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhao, H.; Niu, H.; Ren, Y.; Fang, H.; Fang, X.; Lv, R.; Maqbool, M.; Bai, S. Highly Thermally Conductive 3D Printed Graphene Filled Polymer Composites for Scalable Thermal Management Applications. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 6917–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, X.; Min, P.; Chang, X.; Shu, C.; Ding, Y.; Yu, Z.-Z. 3D Lamellar-Structured Graphene Aerogels for Thermal Interface Composites with High Through-Plane Thermal Conductivity and Fracture Toughness. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Liang, C.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Wong, C. Modulation of covalent bonded boron nitride/graphene and three-dimensional networks to achieve highly thermal conductivity for polymer-based thermal interfacial materials. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 156, 106890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Jiang, P.; Tanaka, T. A review of dielectric polymer composites with high thermal conductivity. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 2011, 27, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B.-H.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.-J. High thermal conductive polyvinyl alcohol composites with hexagonal boron nitride microplatelets as fillers. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 85, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Lee, S.; Kim, N.R.; Koo, H.; Yu, J.; Yang, C.-M. Eco-friendly and scalable strategy to design electrically insulating boron nitride/polymer composites with high through-plane thermal conductivity. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2023, 248, 110355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kim, J.U.; Kim, T.-I. Effective Assembly of Nano-Ceramic Materials for High and Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in a Polymer Composite. Polymers 2017, 9, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkataramanaiah, P.; Aradhya, R.; J, S.R. Investigations on the effect of hybrid carbon fillers on the thermal conductivity of glass epoxy composites. Polym. Compos. 2020, 42, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, I.L.; Truong, V.A. An investigation on effective thermal conductivity of hybrid-filler polymer composites under effects of random particle distribution, particle size and thermal contact resistance. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 144, 118605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, F.; Huang, L.; Dai, K.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Sun, Y.; Ren, D.; Wu, J.; et al. Micro-diamond assisted bidirectional tuning of thermal conductivity in multifunctional graphene nanoplatelets/nanofibrillated cellulose films. Carbon 2021, 189, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Liu, M.; Wu, J.; Xie, Q.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Shen, B.; Bian, X.; Song, W.-L. Promoting the thermal transport via understanding the intrinsic relation between thermal conductivity and interfacial contact probability in the polymeric composites with hybrid fillers. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2022, 232, 109613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelski-Hoell, C.; Bhagwat, S.; Altstädt, V. Thermal, fire, and mechanical properties of solvent-free processed BN/boehmite-filled prepregs. Polymer Engineering & Science, 2019, 59, 1840–1852. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, S.; Calventus, Y.; Román, F.; Hutchinson, J.M. Achieving High Thermal Conductivity in Epoxy Composites: Effect of Boron Nitride Particle Size and Matrix-Filler Interface. Polymers 2019, 11, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senturk, A.E.; Oktem, A.S.; Konukman, A.E.S. Investigation of interfacial thermal resistance of hybrid graphene/hexagonal boron nitride. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2019, 15, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, K.C.; Liem, H. Enhanced thermal conductivity of boron nitride epoxy-matrix composite through multi-modal particle size mixing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 106, 3587–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.-W.; et al. The properties of AlN-filled epoxy molding compounds by the effects of filler size distribution. Journal of materials science 2000, 35, 5907–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, J. Thermal conductivity of epoxy composites with a binary-particle system of aluminum oxide and aluminum nitride fillers. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2013, 51, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.A.; Alhamdo, M.H. Enhancing the thermal conductivity of hot-mix asphalt. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.N.; Khan, M.O.; Chan, E.; Naguib, H.E.; Dawson, F.; Adinkrah, V.; Lakatos-Hayward, L. Synergistic effects of hybrid fillers on the development of thermally conductive polyphenylene sulfide composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 127, 3293–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-P.; Yoon, S.-W.; Hwang, T.; Oh, J.-S.; Hong, S.-C.; Lee, Y.; Nam, J.-D. High thermal conductivity epoxy composites with bimodal distribution of aluminum nitride and boron nitride fillers. Thermochim. Acta 2012, 537, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zou, H.; Liang, M. A Concurrent Enhancement of Both In-Plane and Through-Plane Thermal Conductivity of Injection Molded Polycarbonate/Boron Nitride/Alumina Composites by Constructing a Dense Filler Packing Structure. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 2100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

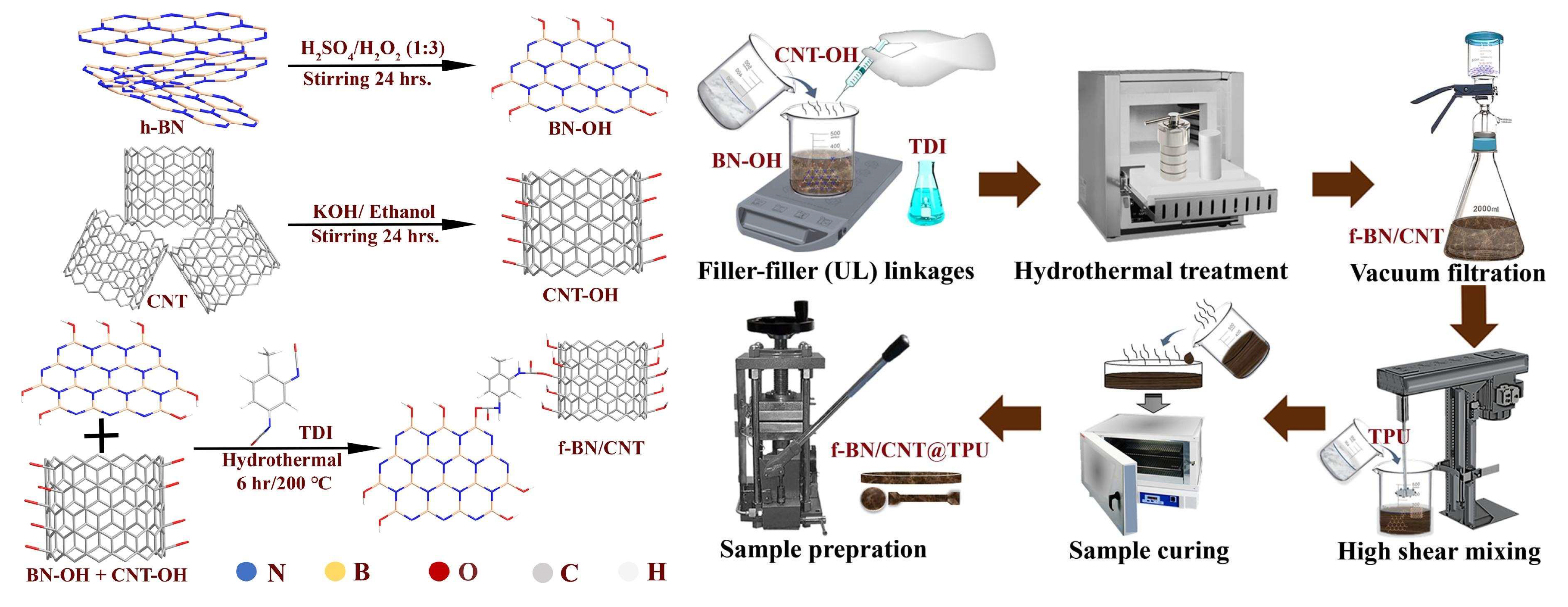

- Bashir, A.; Maqbool, M.; Lv, R.; Usman, A.; Aftab, W.; Niu, H.; Kang, L.; Bai, S.-L. Engineering of Interfacial Interactions Among BN And CNT Hybrid Towards Higher Heat Conduction Within TPU Composites. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 167, 107428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Kim, J. Enhanced through-plane thermal conductivity of paper-like cellulose film with treated hybrid fillers comprising boron nitride and aluminum nitride. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 200, 108424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Konstantinou, A.; Wang, Y.; Ronzello, J.; Davis, K.; Cao, Y. Design of an experimental study of high through-plane thermal conductivity hybrid epoxy composite insulation with superior dielectric strength. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, P.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wu, T.; You, C. Highly thermally conductive and electrical insulating epoxy-based composites containing oriented ternary carbon/graphene/MgO hybrid network. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 13115–13124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Guo, Y.; Tang, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, K.; Tian, X. Epoxy composite with significantly improved thermal conductivity by constructing a vertically aligned three-dimensional network of silicon carbide nanowires/ boron nitride nanosheets. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2020, 187, 107855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, C.; Yao, Q.; Chen, F.; Fu, Q. Enhanced thermal conductivity and wear resistance of polytetrafluoroethylene via incorporating hexagonal boron nitride and alumina particles. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 139, 51497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Matrix | Filler | Loading | Interaction | Technique | Thermal Conductivity(W m-1K-1) | YearRef |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-B | DiamondBoron | 67 vol%0.3 wt% | interfacial bonding due to covalent bond | metal matrix alloying method,gas pressure infiltration | 868 (K∥) | 2019 [45] |

| BaTiO3 | Cu | 22.3 vol% | Epsilon-negativepermittivity behavior | 17.7 at 150 °C | 2020 [46] | |

| epoxy | AgNPs, AgNWs,CFs | 3 wt% | 0.76 (K⊥) | 2022 [47] |

| Matrix | Filler | Loading | Interaction | Technique | Thermal Conductivity(Wm-1K−1) | YearRef |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | PDA-BNF@BNNPs | 40 wt.% | brick and plank strategy | 6.43 (K∥)11.85 (K⊥) | 2022 [57] | |

| epoxy | (AlN–H) | 47.26 vol% | freeze-casting methodinfiltration method | 9.48 (K∥)4.45 (K⊥) | 2020 [58] | |

| CNF | BNNT | 25 wt % | Hydrophobic- hydrophobic interaction | Vacuum assisted fiteration | 21.39 (K∥) | 2017 [59] |

| PDMS | BNNS | 16 wt % | Guided assembly | 11.05 (K∥) 1.15 (K⊥) |

2019 [60] | |

| Epoxy | 3D-BNNS | 9.6 vol % | Covalent bonding,H-bonding | Templated assembly | 3.13 | 2017 [61] |

| ANF | BNNS | 10 wt % | H-Bonding,Van der waals interaction, | Vacuum assisted filtration | 2.4 (K∥) 0.7 (K⊥) |

2019 [15] |

| Epoxy | BNNS | 15 vol % | Freezing assembly (bidirectional | 6.54 (K∥) 0.7 (K⊥) |

2019 [62] | |

| ANF | BNNS (functionalized) | 30 wt % | H-Bonding,Van der waals interaction | Vacuum assisted filtration | 46.7 (K∥) | 2020 [63] |

| CNF | BNNS (hydroxylated) | 60 wt % | H-bonding | Vacuum assisted filtration | 24.27 (K∥) | 2018 [64] |

| PS @PDDA | BNNS | 13.4 vol % | Electrostatic interaction | Mold pressing | 8.0 (K∥) | 2017 [65] |

| Epoxy | BNNS-rGO | 13.16 vol % | Van der waals interaction | Ice-templated assembly | 5.05 (K⊥) | 2018 [66] |

| Epoxy | 3D-BN | 59.43 vol % | Templated assembly | 6.11 (K⊥) | 2020 [67] | |

| PVA | h-BNNS | 0 to 60 wt% | vacuum filtration processself-assembly process | 14.21 (K∥) 7.29 (K⊥) |

2021 [68] | |

| BN-SiC | (PDMS) | 8.35 vol % | atomic-level coupling | ice-templated assembly and high-temperature sintering | 3.87 (K⊥) | 2022 [69] |

| Matrix | Filler | Loading | Interaction | Technique | Thermal Conductivity (Wm-1K−1) | YearRef |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| olefin block copolymer (OBC) | carbon fiber | 30 vol% | sharing force induce alignment | melting extrusion method | 15.06 (K⊥) | 2023 [87] |

| epoxy | graphene-diamond framework (GRDF) | 43 wt% | simple filtration method | 22.7 (K⊥) 21.8 (K∥) |

2022 [76] | |

| Polylactic acid (PLA) | graphene nanoplatelets (GNP) | 6 wt% | solution blendingcompression molding process | 0.87 (K∥) 0.58 (K⊥) |

2019 [88] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).