1. Introduction

Korean water deer (

Hydropotes inermis argyropus) is belonged to the family Cervidae and is the most dominant wild deer in Republic of Korea. However, it is classified as a vulnerable species according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list [

1]. Korean water deer (WD) are distinctive for their unique habitats and appearance, particularly the absence of antlers, which sets them apart from many other deer species. Instead of antlers, they possess long, prominent canine teeth, which are a notable feature. Aside from those features, with many years of our experience, the incidence of tick bites in the WD is significantly lower than that of the roe deer (

Capreolus pygargus), which are another representative species in Republic of Korea [

2].

Ticks have a role as a the most significant vector of various zoonotic protozoan, bacterial, and viral pathogens in public health [

3]. Recently, incidence of tick-borne diseases has been raised in worldwide mainly due to climate changes, land use modification, expansion of key hosts, and increased outdoor activities [

4,

5,

6]. The life cycle of ticks is largely dependent on wildlife, which acts as both hosts and reservoirs. In other words, wildlife plays a key role in the maintenance and transmission of tick-borne pathogens in human, companion animal, livestock, and other wildlife [

7,

8].

The most common way for the ticks to contact an appropriate host is waiting at the top of plants and grasping the hair or feathers of a passing host. During standby for a host, the ticks can detect an upcoming host by using their sensory system such as Haller’s organ which is located on the tarsi of the forelegs [

3]. After contacting a host, the tick moves to find a preferring feeding site. Conditions such as odor, body temperature, humidity, sunlight, and hair have been reported as movement stimuli for ticks [

3,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In host’s body system, the tissues which can provide those conditions for ticks are hair coat, epidermis, and adnexa of dermis in skin tissue.

Although host tropism is different from the tick species, the family Cervidae is known as one of the most important free-living hosts for adult ticks [

13]. As described previously, representative species belonging to Cervidae in Republic of Korea are RD and WD and it seems that the incidence of tick bites in the RD is significantly higher than that of the WD. To our knowledge, there were no reports for the comparative analysis focused on skin tissues and hair features between RD and WD. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the differences of skin tissues with hair coat between the two species and to evaluate their potential functions in tick bites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal specimens and hair sampling

Formalin-fixed skin tissues of two wild RDs and two wild WDs were provided from the Wildlife Research Lab in Kangwon National University. The tissues contained four locations: head; neck; back; and axilla. Randomly collected 10 guard hairs per each skin tissues were separated by using forceps from the remaining skin after saving the required amount for histopathological analysis.

2.2. Hair structure analysis

For cuticle analysis, we used the gelatin casting method as previously described [

15]. Briefly, 20% pig native gelatin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was prepared in boiling water. A thin film of gelatin was performed on a clean glass slide. The hairs were placed superficially on the gelatin film and left for overnight at room temperature. Subsequently, hairs were removed leaving the imprint of the scales on the gelatin cast. Images were acquired at ×400 using a BX53 light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Among the two subdivisions of guard hair, namely the hair shield and the hair shaft, we selected the hair shaft, which is closer to the epidermis. The classification system for cuticle and medulla was selected from previous study [

16].

2.3. Hair diamteter and length analysis

Separated hair shafts per each animal were placed on slide glass and fixed using clear tape without additional treatment for measuring the diameter and the length [

17]. The length of the hair was measured using a 150mm/6” digital caliper, and the diameter nearby epifermis was measured using a light microscope and CellSens standard 1.16 software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. Histopathological analysis

Four horizontal sections and four longitudinal sections were trimmed per animal skin parts. The formalin fixed tissues were dehydrated in graded ethanol, cleared in xylene using a HistoCore PEARL tissue processor (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Subsequently, the specimens were embedded in paraffin blocks and Formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissues were then sectioned at 4 μm and stained in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. After the slide preparation, histopathological analysis for comparison between the two species were performed including the distribution of adnexa and the thickness of epidermis and dermis, and distance between midline of hair follicles using NIH ImageJ software (ver. 1.54, Bethesda, MA, USA).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were calculated for all groups to assess the overall quality of the data, including normality. The statistical relationship of hair measurements and histopathological results between RD and WD were determined with a student’s t-test, followed by the Mann–Whitney U test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test to calculate the post-power of the findings using IBM SPSS Statistics (ver. 26, New York, NY, USA). Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative skin pathology of Roe deer and Korean water deer

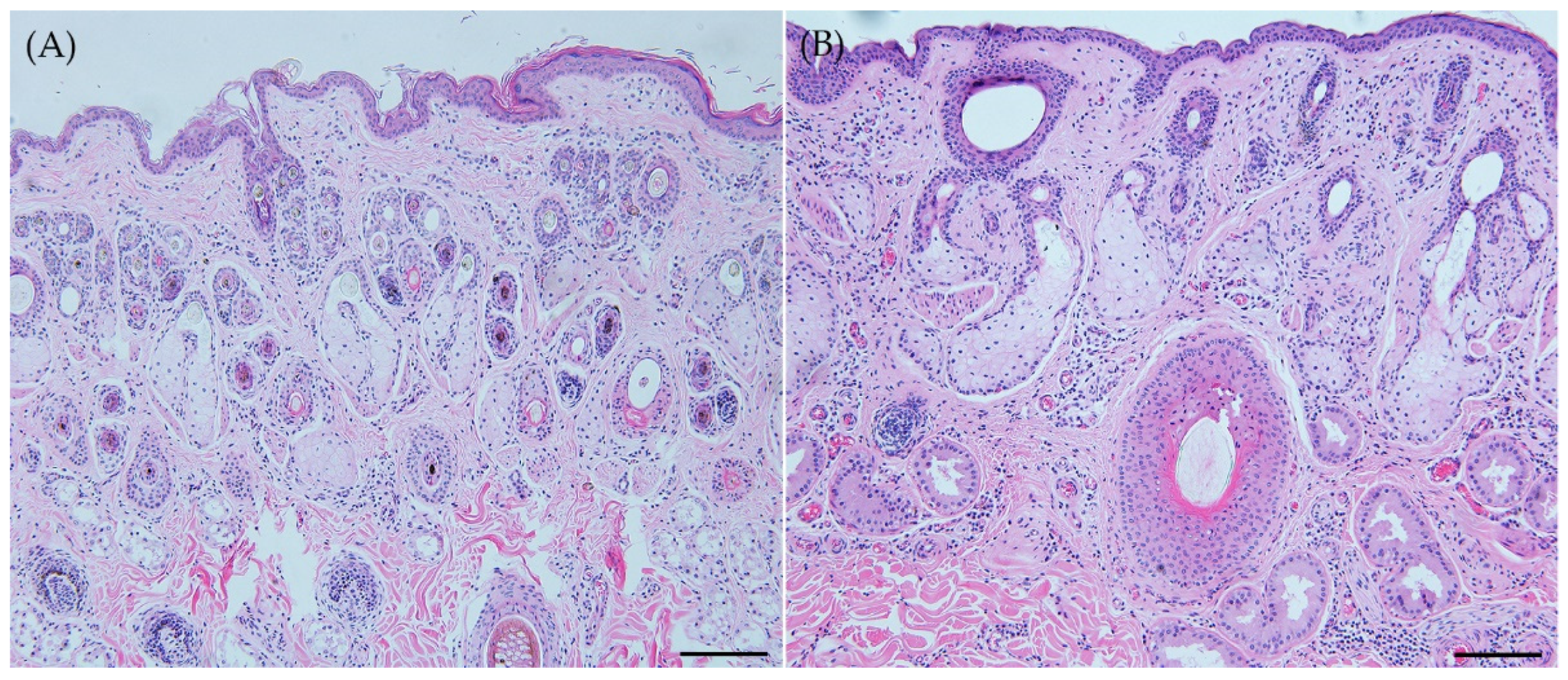

In a comparative pathological analysis, we examined the skin layers, blood vessels, as well as skin appendages including sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and hair follicles (

Figure 1). Noticeable differences were observed in terms of the size of skin appendages and the type of hair follicles, as well as the diameter of dermal blood vessels between the two species. Notably, the size of each skin appendages was observed to be larger in the WD. Regarding the types of hair follicles, RD exhibited a compound primary with secondary follicle pattern, characterized by numerous small follicles secondly located around the primary hair, while WD displayed a simpler primary follicle pattern. Although the distribution of blood vessels in the dermis appeared similar, WD exhibited significantly larger blood vessel diameters. No significant difference in epidermal thickness was observed.

These comparative findings were consistent with the quantitative results obtained through area and diameter measurements (

Table 1). The areas of sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and blood vessels all exhibited statistical significance, with significant enlargement observed in WD (p ≤ 0.004). However, there were no significant differences between the two species in terms of epidermal thickness or the distance between the midline of primary hair follicles (

p=0.403, 0.996).

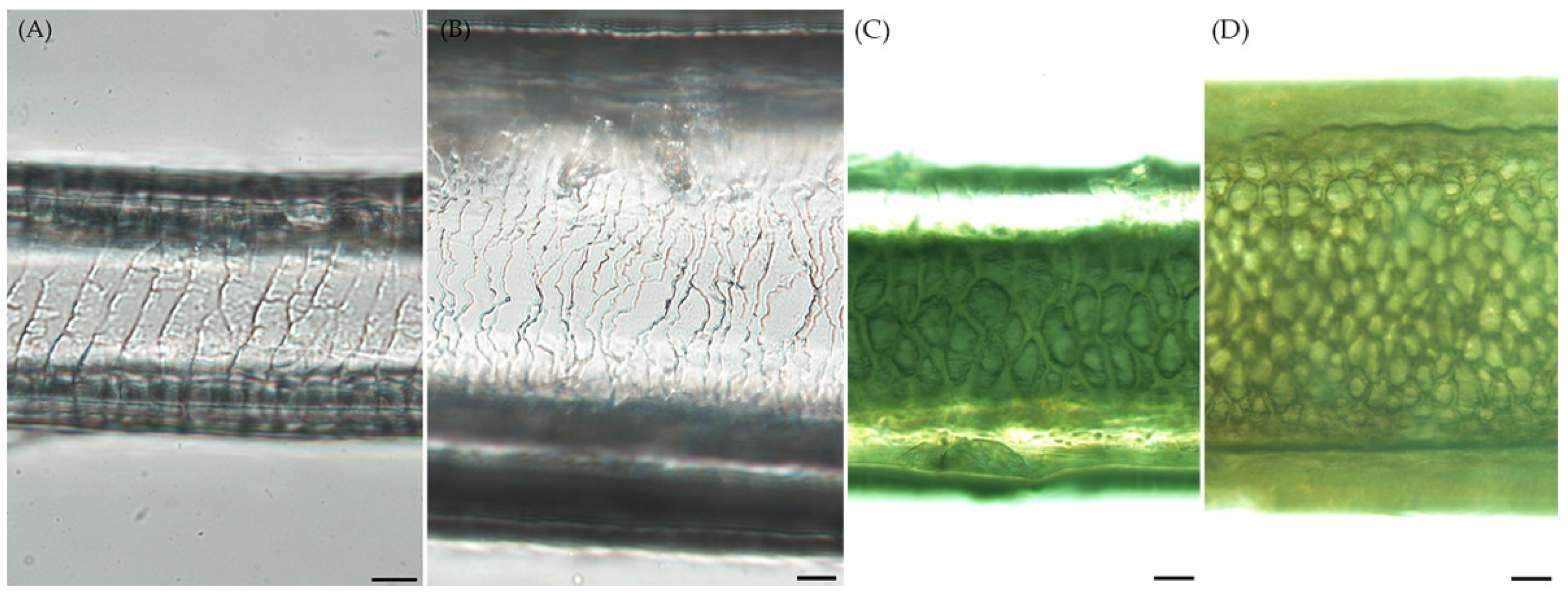

3.2. Hair cuticle and medulla features of Roe deer and Korean water deer

According to the hair cuticle classification system in animals, clear distinctions were observed in the hair cuticle between RD and WD. These distinctions encompassed scale position, structure of the scale margin, distance between scale margins, and scale pattern [

17]. RD exhibited a more regular pattern compared to WD, with the distance between scale margins consistently appearing uniform (

Figure 2A, B). The hair medulla classification system includes composition, structure, pattern, and form of the margins [

17]. In terms of the medulla structure, both species exhibited similar characteristics (

Figure 2C, D).

3.3. Hair diameter and length of Roe deer and Korean water deer

Analysis of hair diameter and length was performed with 20 hair shafts per 4 body parts including head, neck, back, and axilla in both species (

Table 2). In each measured body parts, RD exhibited significantly thinner hair diameters compared to WD (

p < 0.001). Additionally, RD had relatively constant hair diameter than WD. When comparing all body parts together, WD hair was observed to be about 2.83 times thicker than RD hair (

p < 0.001). Regarding the head regions, RD had significantly shorter hair heights than WD (

p < 0.001) and in the back region, RD also showed significantly shorter hair heights than WD (

p = 0.020). However, in total, heights of both species were not significantly different (

p = 0.437).

4. Discussion

This study was conducted based on the hypothesis that the native WD, a native species in Korea, has fewer tick bites compared to the RD, which belongs to the same family Cervidae, and that this difference may be attributed to variations in skin tissues, including skin and hair. Throughout the course of this research, relevant studies were closely examined. However, there was a lack of comparative analysis of the skin, and research on animal fur was primarily focused on forensic and species identification studies [

15,

16,

17].

The skin is the largest organ in the body and plays a crucial role in forming the primary physical barrier that prevents the intrusion of external substances. The components of the skin, including the epidermis, dermis, and appendages, work together to maintain the homeostasis of the skin. Furthermore, they contribute to protecting the body from external parasites such as ticks. To explain why ticks bite the WD less frequently compared to other Cervidae, we investigated whether there were differences in the hair and skin between the WD and the RD.

First, we hypothesized that the sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and blood vessels in the skin of the WD might be more developed, leading to a lower frequency of tick bites. We conducted a comparative analysis between the two species to test this hypothesis. Notably, the results of our comparative pathological analysis showed that the sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and blood vessels in the WD were statistically significantly larger than those in the RD. Consequently, sweat and sebaceous glands in the skin may play a role in preventing the intrusion of external parasites like ticks.

We then compared the differences in the structure of the hair, focusing on the shape of the hair follicles and the characteristics of the hair's cuticle and medulla. In the case of the WD, the shape of the hair follicles was primarily a simple primary hair follicle, while in the RD, it exhibited a compound primary with secondary follicle pattern, indicating a notable difference. Additionally, the WD's hair, being predominantly composed of stiff primary hairs, contrasted with the softer and more pliable under hair in the RD. This characteristic of the RD's haircoat makes it more suitable for factors such as temperature regulation, humidity, and UV protection, creating a potentially favorable environment for ticks []. The cuticle plays a crucial role as a structure through which ticks must navigate to reach the host's epidermis. In the RD, the structure of the scale margin, distance between scale margins, and scale pattern appeared regular and consistent. In contrast, in WD, these features were irregular and not consistent. This may also suggest that the environment in RD's fur may pose difficulties for ticks to move through.

Finally, we compared the diameter and length of the fur. While there were no inter-species differences in hair length, the hair diameter in WD was significantly thicker across all body parts, including the head, neck, back, and axilla. Within the species, the thickness of fur varied by body part in WD, whereas RD showed consistent thickness. In a previous study involving Gyr cattle (Zebu) and crossbred (Holstein×Gyr), fur length and diameter were found to be significantly correlated with tick infestation [

18]. In our study, considering that there was no significant difference in hair length between the two species, we suggest that fur diameter may play a role in tick infestation in family Cervidae. This is because WD's hairs were approximately 2.8 times thicker those of RD's fur, potentially creating a more challenging environment for ticks to move through the hair coat.

We conducted a thorough comparative analysis of the skin tissues and fur characteristics between WD and RD based on our hypothesis that the lower tick bite frequency in water deer might be due to unique features of their skin tissues and fur. As a result, we demonstrated that WD have larger skin appendages compared to RD, irregular cuticle patterns, and significantly larger fur diameter. Since there is limited previous research on these criteria, further studies are needed to explore these unique features in WD. However, we suggest that these differences may be attributed to the additional distinctive characteristics to evade tick bites of WD.

5. Conclusions

In this study, our main objective was to investigate the potential factors which made the Korean water deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) to have the lower prevalence of tick bites than the roe deer (Capreolus pygargus), both belonging to the Cervidae family. We hypothesized that unique characteristics in the skin tissue and hair shaft of Korean water deer might contribute to this difference. Through a comparative analysis, we found that Korean water deer exhibited larger skin appendages, irregular cuticle patterns, and significantly thicker fur compared to roe deer. These novel findings suggest that in addition to previously known unique traits, Korean water deer's distinct skin and fur characteristics may play a role in reducing tick infestations. However, further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms behind this phenomenon. Overall, our study sheds light on the intricate relationship between animal physiology and tick interactions in natural environments, contributing to our knowledge of wildlife biology and tick-borne disease prevention.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, S.K.; Lee, E.J. Internationally vulnerable Korean water deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) can act as an ecological filter by endozoochory. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y. Spatio-temporal distribution of ectoparasites in relation to habitat use characteristics of mammalian hosts in cultivated land and nearby habitats in Gangwon-do. PhD thesis, Kangwon National University, Gangwon-do. Dec 2022.

- Nicholson, W.L.; Sonenshine, D.E.; Noden, B.H.; Brown, R.N. Ticks (Ixodida). In Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 3rd ed.; Mullen, G.R., Durden, L.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 603–672.(Ixodida). In Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 3rd ed.; Mullen, G.R., Durden, L.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 603–672. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, N.H.; Ben Beard, C.; Ginsberg, H.S.; Tsao, J.I. Possible effects of climate change on ixodid ticks and the pathogens they transmit: Predictions and observations. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diuk-Wasser, M.A.; VanAcker, M.C.; Fernandez, M.P. Impact of land use changes and habitat fragmentation on the eco-epidemiology of tick-borne diseases. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 1546–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrame, A.; Laroche, M.; Degani, M.; Perandin, F.; Bisoffi, Z.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P. Tick-borne pathogens in removed ticks Veneto, northeastern Italy: A cross-sectional investigation. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 26, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, J.I.; Hamer, S.A.; Han, S.; Sidge, J.L.; Hickling, G.J. The contribution of wildlife hosts to the rise of ticks and tick-borne diseases in North America. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 1565–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orkun, Ö.; Çakmak, A. Molecular identification of tick-borne bacteria in wild animals and their ticks in Central Anatolia, Turkey. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 63, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oorebeek, M.; Sharrad, R.; Kleindorfer, S. What attracts larval Ixodes hirsti (Acari: Ixodidae) to their host? Parasitol. Res. 2009, 104, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.L.; Salgado, V.L. Ticks home in on body heat: a new understanding of Haller’s organ and repellent action. PLoS One 2019, 2019. 14, e0221659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’kelly, J.C.; Spiers, W.G. Observations on body temperature of the host and resistance to the tick Boophilus microplus (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1983, 20, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haarløv, N. Life cycle and distribution pattern of Lipoptena cervi (L.)(Dipt., Hippobosc.) on Danish deer. Oikos 1964, 15, 93–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiffner, C.; Loedige, C.; Alings, M.; Vor, T.; Ruehe, F. Attachment site selection of ticks on roe deer, Capreolus capreolus. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2011, 53, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Title of Site. Available online: URL (accessed on Day Month Year).

- Cornally, A; Lawton, C. A guide to the identification of Irish mammal hair. Dublin: National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs; 2016. (Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 92).

- De Marinis, A.M.; Asprea, A. Hair identification key of wild and domestic ungulates from southern Europe. Wildl. Biol. 2006, 12, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, E.J. A new technique for the rapid simultaneous examination of medullae and cuticular patterns of hairs. Microscope 1998, 46, 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Verissimo, C.J.; Nicolau, C.V.J.; Cardoso, V.L.; Pinheiro, M.G. Haircoat characteristics and tick infestation on gyr (zebu) and crossbred (holdstein x gyr) cattle. Arch. Zootec. 2002, 51, 389–392. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).