Submitted:

21 September 2023

Posted:

25 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Burnout in Healthcare Professionals

1.2. Work Engagement in Healthcare Professionals

1.3. Person-Centered Approach and Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) in Burnout Research

1.4. Objectives of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Sociodemographic Variables Questionnaire (Q-SV)

2.4. Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI)

2.5. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9)

2.6. Job Satisfaction Scale (JSS [84])

2.7. Psychological Well-Being Scale for Adults (BIEPS-A [87])

2.8. Design

2.9. Procedure

2.10. Ethical Considerations

2.11. Data Analysis

2.12. Burnout Prevalence

2.13. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

2.14. Latent Profile Analysis

2.15. Multinomial Logistic Regression

3. Results

3.1. Burnout Prevalence

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

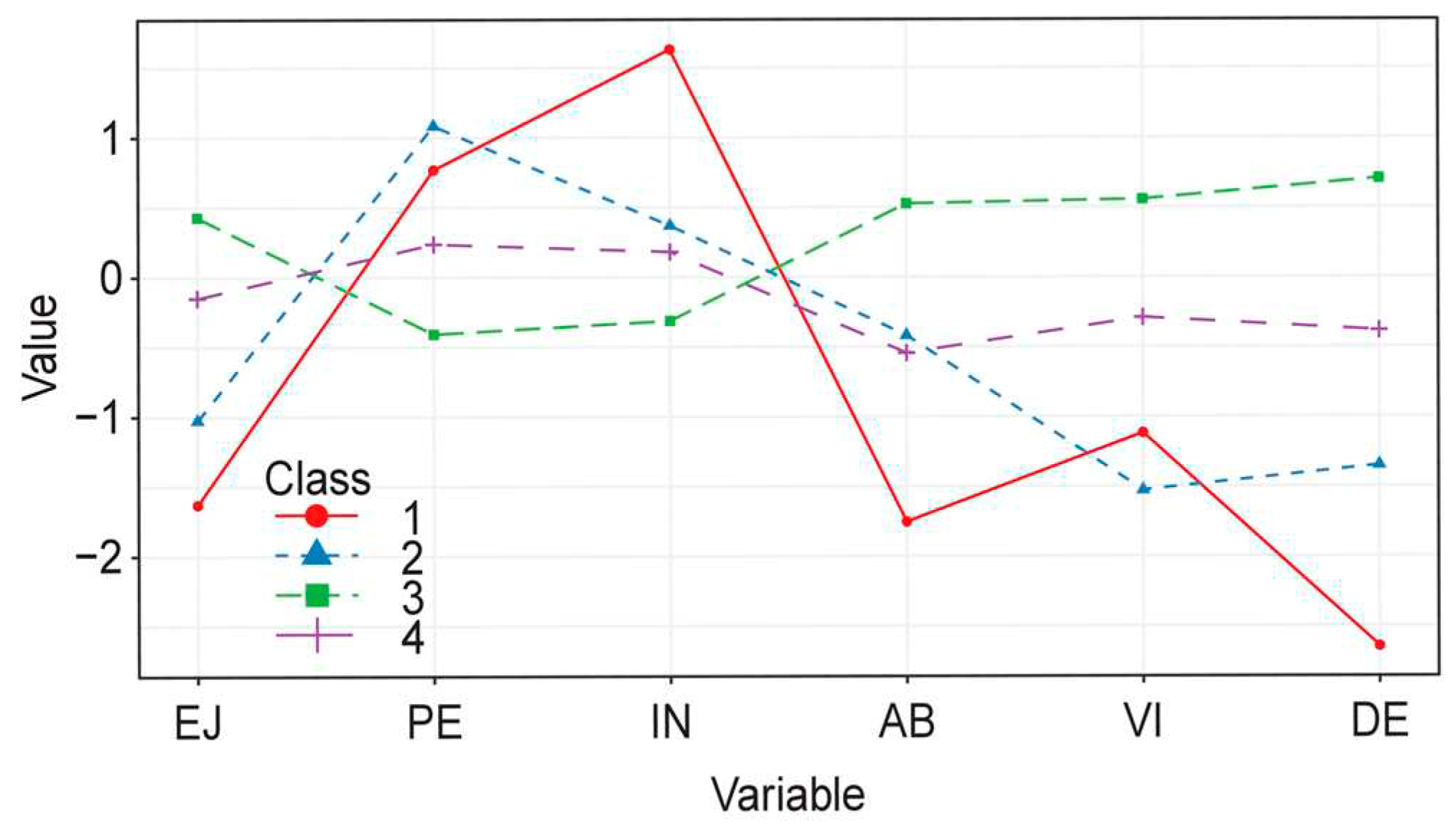

3.3. Latent Profile Analysis

3.4. Multinomial Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications of this Work

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Estrés y Procesos Cognitivos; Martínez Roca: Barcelona, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: Fort Worth, TX, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Monte, P.R. El Síndrome de Quemarse Por el Trabajo (Burnout). Una Enfermedad Laboral en la Sociedad del Bienestar; Pirámide: Madrid, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Monte, P.R. The influence of guilt on the relationship between burnout and depression. Eur. Psychol. 2012, 17, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Söderfeldt, M.; Söderfeldt, B.; Warg, L.E.; Ohlson, C.G. The factor structure of the Maslach burnout inventory in two Swedish human service organizations. Scand. J. Psychol. 1996, 37, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Hilal, M.M. Dimensionality of burnout: Testing for invariance across Jordanian and Emirati teachers. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 77, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Monte, P.R. Factorial validity of the Maslach burnout inventory (MBI-HSS) among Spanish professionals. Rev. Saude Publica 2005, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Y.; Bachelor, P.A.; Michael, W.B. The dimensionality of a modified form of the Maslach burnout inventory for university students in a teacher-training program. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1989, 49, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.J.; Michael, W.B.; Kim, S. Construct validity of the educators survey for a sample of middle school teachers. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1994, 54, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliath, T.J.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Gillespie, D.F.; Bluedorn, A.C. A test of the Maslach burnout inventory in three samples of healthcare professionals. Work Stress 2000, 14, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen burnout inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horn, J.E.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Enzmann, D. Teacher burnout and lack of reciprocity. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A.; Ezrachi, Y. On the discriminant validity of burnout, depression and anxiety: A re-examination of the burnout measure. Anxiety Stress Coping 2003, 16, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Vardakou, I.; Kantas, A. The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2003, 19, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Monte, P.R. SBI Spanish Burnout Inventory; TEA: Madrid, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, T.; Ho, R.; Tang, A.; Tam, W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 123, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoafo, E.; Hanbali, N.; Patel, A.; Singh, P. What are the significant factors associated with burnout in doctors? Occup. Med. (Lond) 2015, 65, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, A.E.; Hafstad, E.V.; Himmels, J.P.W.; Smedslund, G.; Flottorp, S.; Stensland, S.Ø.; Stroobants, S.; Van De Velde, S.; Vist, G.E. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.E.; Kim, H.C.; Yoo, S.Y.; Lee, K.U.; Lee, H.W.; Lee, S.H. Factors associated with burnout among healthcare workers during an outbreak of MERS. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranu, S.M.; Ilie, A.C.; Turcu, A.M.; Stefaniu, R.; Sandu, I.A.; Pislaru, A.I.; Alexa, I.D.; Sandu, C.A.; Rotaru, T.S.; Alexa-Stratulat, T. Factors associated with burnout in healthcare professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.C.; Shanafelt, T.D.; West, C.P.; Sinsky, C.A.; Trockel, M.T.; Nedelec, L.; Maldonado, Y.A.; Tutty, M.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Fassiotto, M. Burnout, depression, career satisfaction, and work-life integration by physician race/ethnicity. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2012762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hintsa, T.; Elovainio, M.; Jokela, M.; Ahola, K.; Virtanen, M.; Pirkola, S. Is there an independent association between burnout and increased allostatic load? Testing the contribution of psychological distress and depression. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 1576–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwhaibi, M.; Alhawassi, T.M.; Balkhi, B.; Al Aloola, N.; Almomen, A.A.; Alhossan, A.; Alyousif, S.; Almadi, B.; Essa, M.B.; Kamal, K.M. Burnout and depressive symptoms in healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Saeed, H.; Hussain, A.; Hashmi, A. Burnout and mental illness related stigma among healthcare professionals in Pakistan. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, P.; Shapiro, C.M. Disturbed sleep and burnout: Implications for long-term health. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 65, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, S.; Ugarten, U.; Shirom, A.; Kahana, L.; Lerman, Y.; Froom, P. Chronic burnout, somatic arousal and elevated salivary cortisol levels. J. Psychosom. Res. 1999, 46, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burston, A.S.; Tuckett, A.G. Moral distress in nursing: Contributing factors, outcomes and interventions. Nurs. Ethics 2013, 20, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, R.C.; Albrecht, G.; Hoogstraten, J.; Eijkman, M.A.J. Factorial validity of the Maslach burnout inventory—Dutch version (MBI-NL) among dentists. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Z.X.; Yeo, K.A.; Sharma, V.K.; Leung, G.K.; McIntyre, R.S.; Guerrero, A.; Lu, B.; Lam, C.C.S.F.; Tran, B.X.; Nguyen, L.H.; et al. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, D.J.; Van Vendeloo, S.N.; Brand, P.L.P.; Van Der Velpen, I.; De Jong, K.; Van Den Heijkant, F.; Van Der Heijden, F.; Prins, J.T. The relationship between burnout, personality traits, and medical specialty. A national study among Dutch residents. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Shirom, A.; Golembiewski, R.T. Conservation of resources theory. In Handbook of Organizational Behavior, Golembiewski, R.T., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, 2000; pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shirom, A.; Melamed, S. A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2006, 13, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S. Burnout is associated with a depressive cognitive style. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 100, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubale, B.W.; Friedman, L.E.; Chemali, Z.; Denninger, J.W.; Mehta, D.H.; Alem, A.; Fricchione, G.L.; Dossett, M.L.; Gelaye, B. Systematic review of burnout among healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsdottir, I.; Rushton, C.H.; Nelson, K.E.; Heinze, K.E.; Swoboda, S.M.; Hanson, G.C. Burnout and moral resilience in interdisciplinary healthcare professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushton, C.J.; Sharma, M. Designing sustainable systems for ethical practice. In Moral Resilience: Transforming Moral Suffering in Healthcare, Rushton, C., Ed.; University Press: Oxford, 2018; pp. 206–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, T.; Zhang, T.; Cai, W.; Song, X.; Chen, A.; Deng, G.; Ni, C. Social support and mental health among health care workers during coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: A moderated mediation model. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0233831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, Z.; Zeinoun, P. Self-compassion explains less burnout among healthcare professionals. Mindfulness (N Y) 2020, 11, 2542–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, M.; Agut, S.; Peiró, J.M. Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Llorens, S.; Peiro, J.M.; Grau, R. Desde el ‘burnout’ al ‘engagement’: Una nueva perspectiva? Rev. Psicol. Trab. las Organ. 2000, 16, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Burnout. In Encyclopedia of Mental Health, H, F., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 1998; pp. 202–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ginbeto, T.; Debie, A.; Geberu, D.M.; Alemayehu, D.; Dellie, E. Work engagement among health professionals in public health facilities of Bench-Sheko zone, southwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Romero-Martín, M.; Romero, A.; Coronado-Vázquez, V.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Work engagement and psychological distress of health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Soriano-Tarín, G.; Romero-Martín, M.; Allande-Cussó, R.; Cabanillas-Moruno, J.L.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Psychological distress among occupational health professionals during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Spain: Description and effect of work engagement and work environment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 765169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenaro, C.; Flores, N.; Orgaz, M.B.; Cruz, M. Vigour and dedication in nursing professionals: Towards a better understanding of work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomic, M.; Tomic, E. Existential fulfilment, workload and work engagement among nurses. J. Res. Nurs. 2011, 16, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullberg, M.T.; Olsson, H.M.; Alenfelt, G.; Ivarsson, A.B.; Nilsson, M. Ability to solve problems, professionalism, management, empathy, and working capacity in occupational therapy--the professional self description form. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 1994, 8, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.I.; Llorens, S.; Rodríguez, A.M. Empleados saludables y calidad de servicio en el sector sanitario. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernales-Turpo, D.; Quispe-Velasquez, R.; Flores-Ticona, D.; Saintila, J.; Ruiz Mamani, P.G.; Huancahuire-Vega, S.; Morales-García, M.; Morales-García, W.C. Burnout, professional self-efficacy, and life satisfaction as predictors of job performance in health care workers: The mediating role of work engagement. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 21501319221101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout contagion among intensive care nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 51, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, P.E.; De La Torre, F.T.J.; Alberde, C.R.M.; Artigas, L.B.; Moreno, P.J.; García, M.J.M. La participación en la gestión como elemento de satisfacción de los profesionales: Un análisis de la experiencia andaluza. Enferm. Glob. 2003, 2, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pilpel, D.; Naggan, L. Evaluation of primary health services: The provider perspective. J. Community Health 1988, 13, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martínez, I.M.; Pinto, A.M.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robotham, D. Stress among higher education students: Towards a research agenda. High. Educ. 2008, 56, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W.J.M.I.; Bakker, A.B. Exploring the relationship between a multidimensional and multifaceted burnout concept and self-rated performance. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 186–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodics, B.; Szabó, É. Student burnout in higher education: A demand-resource model approach. Trends Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.M.; Lanza, S.T. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis for the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences; Wiley: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, L.J.; Vandenberg, R.J. A person-centered approach to the study of commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2013, 23, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Morin, A.J.S. A person-centered approach to commitment research: Theory, research, and methodology. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 584–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burn. Res. 2016, 3, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portoghese, I.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C.; Galletta, M.; Porru, F.; D’Aloja, E.; Finco, G.; Campagna, M. Measuring burnout among university students: Factorial validity, invariance, and latent profiles of the Italian version of the Maslach burnout inventory student survey (MBI-SS). Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinter, K. Examining academic burnout: Profiles and coping patterns among Estonian middle school students. Educ. Stud. 2021, 47, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Klassen, R.M.; Wang, Y. Academic burnout and motivation of Chinese secondary students. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanity 2013, 3, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, S.M. Academic burnout profiles and motivation styles among Korean high school students. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2020, 62, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Salanova, M. Work engagement: On how to better catch a slippery concept. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Read, S. Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burn. Res. 2017, 7, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkowska-Smolak, T.; Piorunek, M.; Górecki, T.; Garbacik, Ż.; Drabik-Podgórna, V.; Kławsiuć-Zduńczyk, A. Academic burnout of polish students: A latent profile analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna, H.M.; García, B.R.; Olguín, J.; Vásquez, D. Spanish burnout inventory: A meta-analysis based approach. Contad. Adm. 2018, 63, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steppan, M.; Piontek, D.; Kraus, L. The effect of sample selection on the distinction between alcohol abuse and dependence. Int. J. Alcohol Drug Res. 2014, 3, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Toledano, F.; Rodríguez-Rey, R.; De La Rubia, J.M.; Luna, D. A sociodemographic variables questionnaire (Q-SV) for research on family caregivers of children with chronic disease. BMC Psychol. 2019, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Monte, P.R.; Olivares Faúndez, V.E. Psychometric properties of the “Spanish burnout inventory” in Chilean professionals working to physical disabled people. Span. J. Psychol. 2011, 14, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Monte, P.R.; Manzano-García, G. Psychometric properties of the Spanish burnout inventory among staff nurses. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C.I.; Llorens, S.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Dickinson, M.E. Validación de la escala UWES-9 en profesionales de la salud en México. Pensam. Psicol. 2016, 14, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.; Cook, J.; Wall, T. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. J. Occup. Psychol. 1979, 52, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Martínez, H.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, C.; Islas-García, E. Satisfacción laboral en enfermeras del hospital de oncologia Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI IMSS. Enferm. Univ. 2009, 6, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluarte, A. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de satisfacción laboral de warr, cook y wall, versión en español. Rev. Méd. Hered. 2014, 25, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casullo, M. Evaluación del Bienestar Psicológico en Iberoamérica; Paidós: Buenos Aires, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Figuerola-Escoto, R.P.; Luna, D.; Lezana-Fernández, M.A.; Meneses-González, F. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de bienestar psicológico para adultos (BIEPS-A) en población mexicana. CES Psicol. 2021, 14, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusurkar, R.A.; Mak-Van Der Vossen, M.; Kors, J.; Grijpma, J.W.; Van Der Burgt, S.M.E.; Koster, A.S.; De La Croix, A. ‘One size does not fit all’: The value of person-centred analysis in health professions education research. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2021, 10, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, N.; Candelario-Mosco, J.B.; Rosas-Medina, J.H.; Souza-Colín, E. Equivalencia psicométrica de las aplicaciones impresas y electrónicas de tres escalas psicosociales. Rev. Argent. Cienc. Comport. 2020, 12, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigold, A.; Weigold, I.K.; Russell, E.J. Examination of the equivalence of self-report survey-based paper-and-pencil and internet data collection methods. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología. Código Ético del Psicólogo; Trillas: Ciudad de México, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Available online: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code (accessed on 28 Agosto 2023).

- World Medical Association. Declaración de helsinki de la amm – principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos. Available online: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/ (accessed on 28 Agosto 2023).

- Leys, C.; Klein, O.; Dominicy, Y.; Ley, C. Detecting multivariate outliers: Use a robust variant of the Mahalanobis distance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 74, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, D.; Svedin, C.G.; Hall, F.; Kazemi, E.; Dahlström, Ö. Psychometric properties of the adolescent resilience questionnaire (ARQ) in a sample of Swedish adolescents. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrucca, L.; Fop, M.; Murphy, T.B.; Raftery, A.E. mclust 5: Clustering, classification and density estimation using Gaussian finite mixture models. R J. 2016, 8, 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Yang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, S.; Li, W.; Ren, J.; Tian, X.; Wang, X. Use of latent profile analysis and k-means clustering to identify student anxiety profiles. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N. Estadística Para Psicólogos; Prentice Hall: México, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D.K. What is the proper way to apply the multiple comparison test? Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2018, 71, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyhältö, K.; Pietarinen, J.; Haverinen, K.; Tikkanen, L.; Soini, T. Teacher burnout profiles and proactive strategies. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 36, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.A.; Gabriel, A.S.; Calderwood, C.; Dahling, J.J.; Trougakos, J.P. Better together? Examining profiles of employee recovery experiences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1635–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Burnout and engagement: Contributions to a new vision. Burn. Res. 2017, 5, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varella, M.A.C.; Ferreira, J.H.B.P.; Pereira, K.J.; Bussab, V.S.R.; Valentova, J.V. Empathizing, systemizing, and career choice in Brazil: Sex differences and individual variation among areas of study. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 97, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J. Empathy in medicine: What it is, and how much we really need it. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Lamm, C. Empathy versus personal distress: Recent evidence from social neuroscience. In The Social Neuroscience of Empathy, Decety, J., Ickes, W., Eds.; MIT Press Scholarship Online: Cambridge, MA, 2009; pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Empathy and feelings of guilt experienced by nurses: A cross-sectional study of their role in burnout and compassion fatigue symptoms. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 35, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, P.; Denieffe, S.; Gooney, M. Running on empathy: Relationship of empathy to compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in cancer healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl) 2019, 28, e13124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamara, E.; Richardson, C. Using latent profile analysis to understand burnout in a sample of Greek teachers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, A.; Vander Elst, T.; Vandenbroeck, S.; Godderis, L. Burnout profiles among young researchers: A latent profile analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 839728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, A.K.; Bonotis, K.; Sokratous, M.; Siokas, V.; Dardiotis, E. Burnout evaluation and potential predictors in a Greek cohort of mental health nurses. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero-Jurado, M.; Gázquez-Linares, J.J.; Simón-Márquez, M. Analysis of burnout predictors in nursing: Risk and protective psychological factors. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2018, 11, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Wang, J.; Bi, D.; He, C.; Mao, H.; Liu, X.; Feng, L.; Luo, J.; Huang, F.; Nordin, R.; et al. Predictors of job burnout among Chinese nurses: A systematic review based on big data analysis. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velando-Soriano, A.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Ramírez-Baena, L.; De La Fuente, E.I.; Cañadas-De La Fuente, G.A. Impact of social support in preventing burnout syndrome in nurses: A systematic review. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 17, e12269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.J.; Tsou, M.T. Age, sex, and profession difference among health care workers with burnout and metabolic syndrome in Taiwan tertiary hospital-a cross-section study. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 854403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfuqaha, O.A.; Al-Olaimat, Y.; Abdelfattah, A.S.; Jarrar, R.J.; Almudallal, B.M.; Ajamieh, Z.I.A. Existential vacuum and external locus of control as predictors of burnout among nurses. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinamon, R.G.; Rich, Y. Gender differences in the importance of work and family roles: Implications for work–family conflict. Sex Roles 2002, 47, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Very low | Low | Medium | High | Critical |

| Frequency | 66 | 101 | 132 | 42 | 14 |

| Percentage | 18.6 | 28.5 | 37.2 | 11.8 | 3.9 |

| Variable | M (SD) | Range (Min–Max) |

Psychological exhaustion | Indolence | Absorption | Vigor | Dedication |

| Enthusiasm toward the job | 17.65 (2.65) | 6–20 | −0.26* | −0.21* | 0.29* | 0.36* | 0.47* |

| Psychological exhaustion | 7.18 (4.02) | 0–16 | 1 | 0.26* | −0.16* | −0.45* | −0.36* |

| Indolence | 3.56 (3.34) | 0–21 | 1 | −0.21* | −0.23* | −0.28* | |

| Absorption | 12.28 (2.05) | 1–15 | 1 | 0.44* | 0.49* | ||

| Vigor | 11.33 (2.71) | 0–15 | 1 | 0.55* | |||

| Dedication | 13.53 (1.80) | 5–15 | 1 |

| Profiles | AIC | CAIC | BIC | SABIC | BLRT-p | Entropy |

| Indolence | 5353.50 | 5480.17 | 5454.18 | 5371.69 | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| Absorption | 5272.96 | 5433.74 | 5400.74 | 5296.05 | 0.01 | 0.90 |

| Vigor | 5236 | 5430.88 | 5390.88 | 5263.98 | 0.01 | 0.85 |

| Variables | M (SD) | f | η2 | p.h. | |||

| Burnout with high indolence | Burnout with low indolence | High engagement, low burn | In progress of burning | ||||

| EJ | 13.33 (2.80) | 14.84 (2.12) | 18.78 (1.87) | 17.22 (2.41) | 58.22*** | 0.37 | 1 and 2 ≠ 3 ≠ 4 |

| PE† | 10.27 (3.92) | 11.68 (3.01) | 5.57 (3.34) | 8.12 (3.72) | 43.26*** | 0.26 | 1 ≠ 3, 2 ≠ 3 ≠ 4 |

| IN | 9.05 (5.09) | 4.57 (3.22) | 2.52 (2.47) | 4.24 (3.29) | 18.04*** | 0.21 | 2 and 4 ≠ 1 ≠ 3 |

| AB | 8.77 (2.64) | 11.39 (1.68) | 13.35 (1.38) | 11.12 (1.62) | 64.82*** | 0.42 | 2 and 4 ≠ 1 ≠ 3 |

| VI | 8.33 (2.74) | 7.05 (2.40) | 12.79 (1.77) | 10.57 (1.69) | 94.31*** | 0.52 | 1 and 2 ≠ 3 ≠ 4 |

| DE | 8.77 (1.30) | 11.10 (0.72) | 14.79 (0.42) | 12.78 (0.75) | 558.74*** | 0.88 | 1 ≠ 2 ≠ 3 ≠ 4 |

| Variables | BwHIn | BwLIn | IPB | |||||||||

| B | SE | p | OR | b | SE | p | OR | b | SE | P | OR | |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.87 | 0.98 | −0.16 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.84 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.97 |

| Sex (female) | −0.19 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.82 | −0.18 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.82 | −0.17 | 0.33 | 0.60 | 0.84 |

| CS (married) | 0.04 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.26 | 2.19 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.88 | 1.05 |

| CS (other) | −0.50 | 1.41 | 0.71 | 0.60 | 2.01 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 7.47 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 2.35 |

| Pos (nurse) | −1.24 | 1.10 | 0.25 | 0.28 | −2.29 | 0.88 | < 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.98 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.37 |

| Shift (other) | 1.74 | 0.85 | 0.04 | 5.71 | −0.72 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.48 | −0.13 | 0.40 | 0.66 | 0.87 |

| Wl | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 1.04 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.99 |

| Senior | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.74 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.99 |

| 2GJ (yes) | 2.58 | 1.01 | 0.01 | 13.25 | −0.92 | 1.13 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 1.75 |

| 2PP (yes) | −1.45 | 1.29 | 0.26 | 0.23 | −0.42 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.84 | 1.09 |

| JSS | −0.08 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.91 | −0.11 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.89 | −0.05 | 0 | < 0.01 | 0.95 |

| BIEPS−A (high) | −0.75 | 0.61 | 0.22 | 0.46 | −1.64 | 0.50 | < 0.01 | 0.19 | −0.37 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.68 |

| PsPDx (yes) | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.30 | 2.16 | 0.14 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 1.15 | −0.19 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.82 |

| PresPsyD (yes) | −0.01 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 0.50 | 1.59 | −0.14 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).