1. Introduction

The nucleus contains the genome and functions as the site of essential cellular processes such as DNA replication, transcription and RNA processing. During fertilization of various organisms, including animals, plants and fungi, two nuclei from each of the parents fuse to produce a nucleus of the offspring. This nuclear fusion process, or karyogamy, is essential for reproduction. The nuclear compartment is surrounded by the nuclear envelope, which consists of the inner and outer nuclear membranes. The nuclear membranes play various important roles, including nucleocytoplasmic transport of macromolecules through the nuclear pore complexes. However, nuclear membranes are barriers to nuclear fusion because they prevent the mixing of materials inside nuclei.

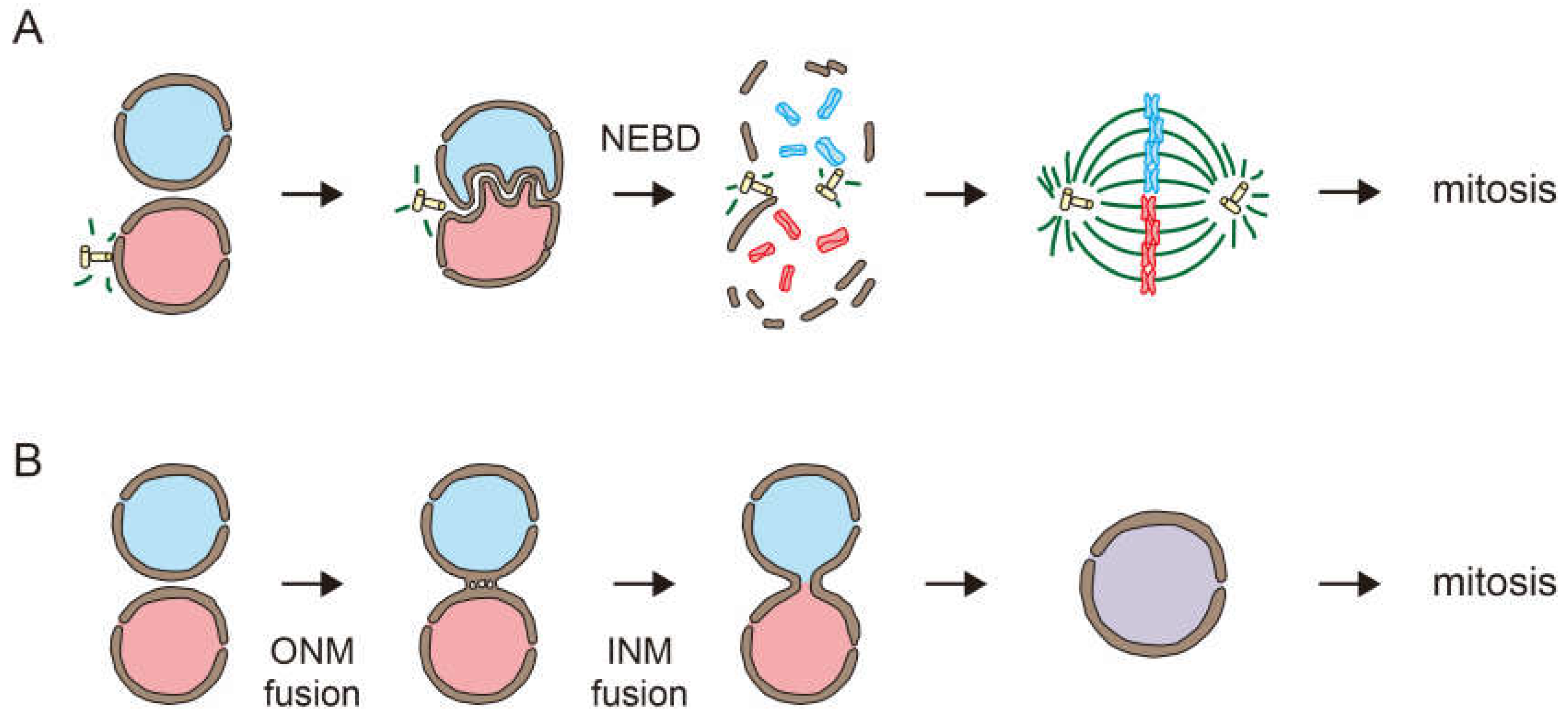

Nuclear fusion during fertilization is achieved by overcoming the barrier function of the nuclear membranes. In mammalian fertilization, the male and female pronuclei fuse during the first embryonic cell division. The nuclear envelope disassembles by nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD) when cells enter the mitotic phase. This allows the mixing of the male and female genomes (

Figure 1A) [

1]. On the other hand, in many organisms, including plants and fungi, nuclear membranes stay intact during nuclear fusion. Nuclear fusion is achieved by the fusion of the nuclear membranes of two nuclei (

Figure 1B) [

2,

3].

Recent genetic analyses of A. thaliana and live-cell imaging technology have identified proteins involved in nuclear fusion during plant reproduction. The identified proteins revealed surprising conservations of nuclear fusion mechanisms between yeast and plants. This review aims to provide an overview of the nuclear fusion machinery functioning in plant reproduction and its evolutionary conservations between fungi and land plants.

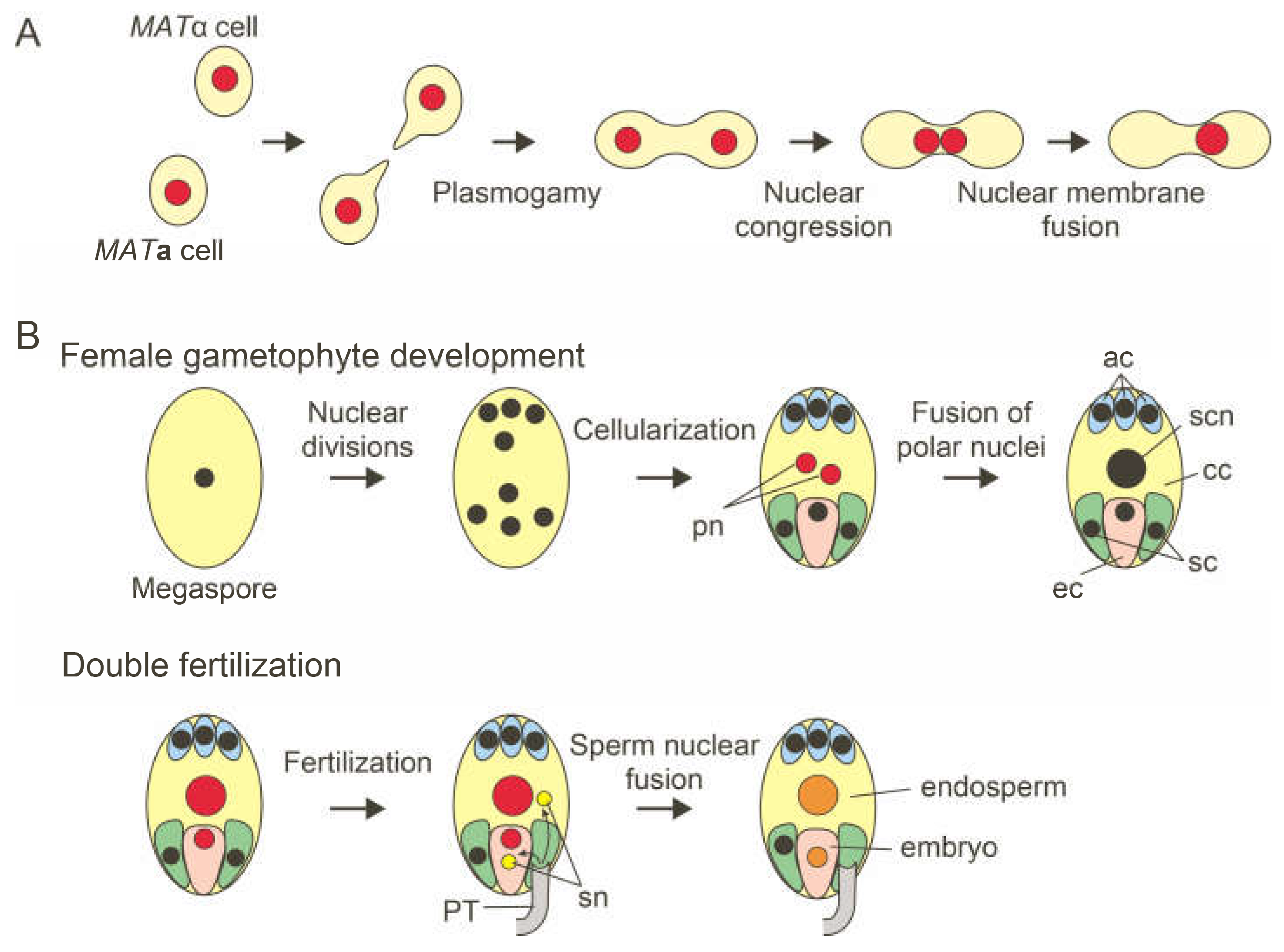

2. Nuclear Fusion in the Sexual Reproduction of Budding Yeast

The mechanism of nuclear fusion during sexual reproduction has been best characterized using budding yeast

Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast genetics have identified genes and proteins involved in nuclear fusion. In the sexual phase, haploid yeast cells of the opposite mating types (

MATa and

MATa) mate to produce diploid cells (

Figure 2A). Haploid cells respond to mating pheromones and exit the mitotic cell cycle [

4]. The two cells produce a mating-specific projection and come into contact. Then, two cells fuse to produce a zygote containing two haploid nuclei. The process of nuclear fusion, called karyogamy, is the final step of yeast mating [

2]. Karyogamy consists of two consecutive steps: nuclear congression and nuclear membrane fusion [

5]. Yeast mutants defective in karyogamy (Kar

-) have been isolated and characterized [

2]. Zygotes of the mutants defective in the nuclear congression have two haploid nuclei positioned far apart in the cells [

5]. Mutants defective in the nuclear membrane fusion produce zygotes in which two haploid nuclei are juxtaposed but do not fuse [

5,

6,

7]. Genetic and biochemical analyses of karyogamy mutants identified the components involved in the nuclear membrane fusion process [

8].

2.1. Nuclear Congression

In the nuclear congression process, two haploid nuclei became in close contact in a microtubule-dependent manner [

2]. The microtubule from the spindle pole bodies (SPBs), the sole microtubule organizing center of budding yeast embedded in the nuclear membrane, interconnects the two nuclei, which allows the nuclei to approach each other. Kinesin family motor proteins, Cik1 and Kar3, function in the nuclear movement [

9]. Mps3 is a member of the Sad1-UNC-84 homology (SUN) protein family localized in the half-bridge structure of the nuclear membrane adjacent to the core SPB [

10,

11]. Mps3 interacts with Mps2 to connect the SPB with the nuclear membrane [

12]. Mutants of these proteins are defective in nuclear fusion. Actin cables also function in the nuclear congression process. Kar9 mediates spindle positioning by connecting microtubules to actin cables [

13,

14].

2.2. Nuclear Membrane Fusion

In the second step, two haploid nuclei fuse to produce a diploid nucleus. In budding yeast, the nuclear membrane stays intact throughout the cell cycle. Nuclear fusion, therefore, must be achieved by the fusion of nuclear membranes, the outer and the inner membranes of the two haploid nuclei. BiP/Kar2, an Hsp70 molecular chaperone in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [

15], and its partner ER-resident J-domain-containing co-chaperones (J proteins), Jem1/Kar8 [

6] and Sec63 [

16] were found to facilitate nuclear fusion in karyogamy. Sec63 forms a complex in the ER membrane with Sec71/Kar7 and Sec72 [

17]. Electron microscopy examination showed that the Sec63 complex is required for the fusion of the outer nuclear membrane, whereas Jem1/Kar8 functions after the fusion of the outer nuclear membrane [

18]. These results suggest that BiP/Kar2 functions in the outer and inner nuclear fusion steps using different J proteins as partners.

Kar5 is a mating process-specific integral membrane protein that localizes adjacent to the SPB [

19]. Functional Kar5 orthologs have been identified in zebrafish, the malaria parasite, green alga, and land plants [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Kar5 is a member of a conserved protein family functioning in nuclear membrane fusion. Electron microscopy examination of the

kar5 mutant zygote suggested that Kar5 is required after outer nuclear membrane fusion and may function in coupling the inner and outer nuclear membranes [

24]. Kar5 recruits Prm3, which is required for outer nuclear membrane fusion adjacent to the SPB. SPB localization of Kar5 is dependent on Mps3 [

24]. Mps3 was identified as a Jem1-interacting protein, and the

mps3 mutant is defective in the nuclear membrane fusion [

11,

24]. These results suggest that Jem1 functions in nuclear membrane fusion by regulating the assembly of Mps3 and possibly Kar5 in the SPB as a partner for BiP.

3. Nuclear Fusion in Plant Reproduction

During the life cycle of flowering plants, nuclear fusion occurs three times. The first nuclear fusion event occurs during the female gametophyte development [

25,

26]. Most angiosperm species, including

Arabidopsis thaliana, have a

Polygonum-type female gametophyte consisting of one egg cell, two synergid cells, one central cell, and three antipodal cells. A single megaspore produced by meiosis undergoes three rounds of nuclear division cycles, producing an eight-nucleate cell. The subsequent nuclear migration and cellularization result in a seven-celled female gametophyte. The central cell contains two polar nuclei. In

A. thaliana and other species, the polar nuclei fuse during female gametogenesis to form the secondary nucleus (

Figure 2B) [

25,

26]. The other two nuclear fusion events occurred during double fertilization. Two sperm cells released from a pollen tube fertilized two female gametes, the egg and central cells, producing the embryo and surrounding endosperm [

27,

28].

3.1. Nuclear Migration

While the nuclear congression step in yeast karyogamy requires microtubules, actin cables play essential roles in the nuclear migration process in plant reproduction. Disruption of actin filaments in developing female gametophytes influenced nuclear migration and altered the final positions of the nuclei [

29,

30]. Sperm nuclei that have entered the female gametes moved toward each female nucleus by the dynamic movement of actin cables [

31]. In the

in vitro fertilized rice zygotes, continuous convergence of actin meshwork toward the egg cell nucleus mediates migration of the sperm nucleus [

32,

33]. Disruption of actin cables in either the egg or the central cell prevented sperm cell nucleus migration. In

A. thaliana, the involvement of Rho-GTPase of Plants 8 (ROP8) and class XI myosin in F-actin dynamics and sperm nuclear migration in the central cell was reported [

34]. Successful sperm nuclear fusion was observed in the female gametophyte of a null allele of

PORCINO that encodes a subunit of TUBULIN FOLDING COFACTOR C, suggesting that microtubules are dispensable for male gamete nuclear migration [

31].

3.2. Nuclear Membrane Fusion

More than 40 genes were identified through screening of

A. thaliana mutants defective in polar nuclei fusion. Since many identified genes encode proteins localized in mitochondria, plastids, the plasma membrane, and the extracellular region, the nuclear fusion defects in these mutants seem to be indirect effects [

35]. Mutants of the transcription factors such as AGL32 and AGL61 showed the polar nuclear fusion defect probably due to the defects in the central cell differentiation [

36,

37]. Recent analyses revealed conservation of nuclear fusion factors between budding yeast and

A. thaliana. These include molecular chaperones in the ER and conserved nuclear membrane proteins (

Table 1).

3.2.1. Molecular Chaperones in the ER

A. thaliana has orthologs of proteins involved in the nuclear membrane fusion during yeast karyogamy. Analyses of mutants of these orthologs showed striking conservations in mechanisms of nuclear membrane fusion between yeast and plant sexual reproduction. The

A. thaliana genome encodes three

BIP genes (

BIP1,

BIP2 and

BIP3).

BIP1 and

BIP2 encode proteins that are 99% identical to each other and are expressed ubiquitously [

38]. Female gametophytes harboring the

bip1 bip2 double mutations are defective in polar nuclei fusion [

39]. The BiP-deficient female gametophytes contain two unfused polar nuclei in close contact, indicating that the defect is in the membrane fusion step. The third

BIP gene,

BIP3, encodes a less well-conserved BiP paralog (80% identical to BiP1 and BiP2) and is expressed only under ER stress conditions in most tissues [

38]. BiP3 expression from the

BIP1 promoter fully complemented the polar nuclear fusion defect of the

bip1 bip2 mutant female gametophyte [

40,

41], indicating that BiP3 has functions that are comparable with those of BiP1 and BiP2.

A. thaliana has orthologs of ER-resident J proteins of yeast [

42], and soluble J proteins, ERdj3A, ERdj3B and P58

IPK, were shown to function in polar nuclear fusion as partners for BiP [

43]. Double mutant female gametophytes lacking P58

IPK and ERdj3A or ERdj3B were defective in the polar nuclear fusion. Electron microscopy examination showed that mutant ovules lacking P58

IPK and ERdj3A were defective in the fusion of the outer nuclear membrane. In contrast, in mutant ovules lacking P58

IPK and ERdj3B, the outer nuclear membrane appeared connected via the ER, but the inner nuclear membrane remained unfused. These results indicate that P58

IPK/ERdj3A and P58

IPK/ERdj3B function at distinct steps of the polar nuclear membrane fusion process as partners for BiP. BiP and ER-resident J proteins likely function in nuclear fusion by regulating the conformation or assembly of proteins required for nuclear membrane fusion. Candidates of such proteins are the nuclear membrane proteins discussed below. BiP and ER-resident J proteins also function in sperm nuclear fusion at fertilization. The central cell of

bip1 bip2 or

erdj3a p58ipk double mutant female gametophytes fertilized by wild-type pollen were defective in sperm nuclear fusion [

44]. By contrast, the central cell of the

erdj3a p58ipk double mutant female gametophytes was not defective in sperm nuclear fusion.

3.2.2. Nuclear Membrane Proteins

Recently, two types of nuclear membrane proteins, SUN proteins and GEX1, were shown to function in nuclear fusion in

A. thaliana [

23,

45]. SUN proteins are integral membrane proteins of the inner nuclear membrane containing a conserved SUN domain. SUN proteins interact with Klarsicht/ANC-1/Syne-1 Homology (KASH) proteins in the outer nuclear membrane through the SUN domain, forming linkers of the nucleoskeleton and the cytoskeleton (LINC) complexes [

46].

A. thaliana genome encodes five SUN protein genes. SUN1 and SUN2 are classical SUN proteins with the SUN domain at the C-terminus. SUN3, SUN4, and SUN5 are mid-SUN proteins with internal SUN domains. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant of SUN proteins (SUNDN) in

A. thaliana pollen was shown to cause the delocalization of the KASH protein, WIP1, from the envelope of the vegetative nucleus, causing defects in nuclear movement in the pollen tube [

47]. Expression of SUNDN in developing female gametophytes resulted in polar nuclear fusion, indicating the roles of SUN proteins in this process [

45]. Expression of a SUNDN variant that does not interact with KASH proteins did not cause the polar nuclear fusion defect, suggesting the involvement of SUN-KASH interaction during polar nuclear fusion. Female gametophytes expressing SUNDN contained unfused polar nuclei in close contact, indicating that the observed inhibition was at the membrane fusion step. Identification of KASH proteins functioning in this process awaits further analyses.

A. thaliana gamete-expressed 1 (GEX1) is a functional ortholog of yeast Kar5. The

GEX1 gene was identified by screening genes expressed in sperm cells [

21]. GEX1 is a nuclear membrane protein in the egg and central cell. Time-lapse live-cell imaging using GFP-GEX1 showed that GEX1 expression was detectable first in the central cell shortly before the polar nuclei were in close contact and then in the egg cell. GEX1-deficient mature female gametophytes were found to contain two unfused polar nuclei in close proximity within the central cell. Electron microscopy showed that the outer membrane of the polar nuclei was connected via the endoplasmic reticulum, whereas the inner membrane remained unfused. The nuclear membrane fusion defect was similar to that observed in the yeast

kar5 mutant zygotes [

24]. Sperm nuclear fusion events were defective in the fertilized egg and central cell following the fertilization of

gex1 female gametophytes by

gex1 pollen. These results indicate that GEX1 is required for all three nuclear fusion events observed in

A. thaliana reproduction.

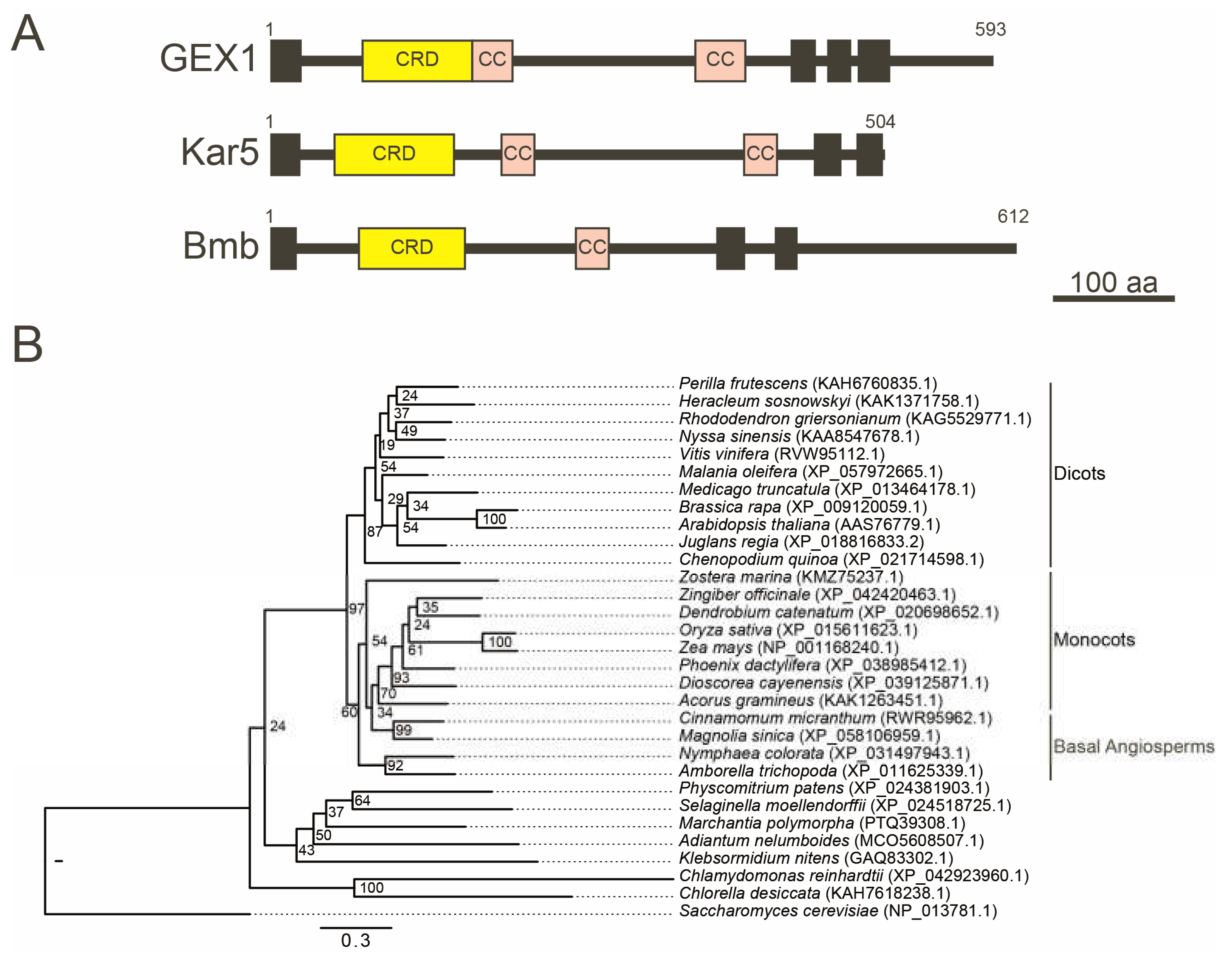

The GEX1/Kar5 family proteins have been identified as key factors for nuclear fusion. Zebrafish Brambleberry (Bmb) is a nuclear membrane protein essential for pronucleus fusion in the zygote and karyomere fusion during early embryogenesis [

20]. The GEX1 orthologs of

Chlamydomonas and

Plasmodium are nuclear membrane proteins required for sexual reproduction [

22]. Although Kar5, Bmb, and GEX1 differ widely in size and degree of sequence identity, they all contain a well-defined Cys-rich domain (CRD) within their N-terminal region, followed by coiled-coil domains (

Figure 3A). While GEX1 contains three transmembrane domains in the C-terminal region, Kar5 and Bmb contain two transmembrane domains. GEX1 orthologs have been identified in various land plants, including eudicots, monocots, basal angiosperms, lycophytes, and bryophytes (

Figure 3B) [

21,

48]. All land plant GEX1 orthologs contain the CRD in their N-terminal region, followed by two or three putative coiled-coil regions and three transmembrane domains [

23]. However, sequence identities are not high even between angiosperm GEX1 orthologs; the sequence identity between

Arabidopsis GEX1 and

Oryza sativa GEX1 ortholog is lower than 50%. Despite the relatively low sequence identities, the expression of GEX1 orthologs of

O. sativa, as well as of

Brassica rapa from the

Arabidopsis GEX1 promoter, rescued the polar nuclear fusion defect of the

gex1 mutant [

49]. In

B. rapa and rice, fusion starts during female gametogenesis but is not completed before fertilization [

50,

51]. The completion of polar nuclear fusion in the

gex1 female gametophytes expressing BrGEX1 or OsGEX1 supports that the variation in the times of nuclear fusion completion is not due to differences in the activities of GEX1 orthologs.

4. Roles of Nuclear Fusion in Seed Development

The

bip1 bip2 and

erdj3a p58ipk double mutant female gametophytes displayed aberrant endosperm proliferation after fertilization with wild-type pollen [

39,

43]. Live imaging analyses of endosperm development showed that the aberrant endosperm proliferation was not due to the polar nuclear fusion defect but the sperm nuclear fusion defect upon fertilization. The fertilized

bip1 bip2 and

erdj3a p58ipk double mutant female gametophytes contained an unfused sperm nucleus in the central cell. Triple nuclear fusion between the unfused sperm nucleus and polar nuclei was achieved during the first endosperm nuclear division. However, the fusion of the sperm nucleus with condensed chromatin resulted in aberrant endosperm nuclear divisions and delayed expression of paternal genes. Aberrant endosperm proliferation was also observed after fertilization of

gex1 female gametophytes with

gex1 pollen [

23].

In contrast, endosperm proliferated normally after fertilization of

erdj3b p58ipk double mutant female gametophytes with wild-type pollen [

43]. In the fertilized central cell of the

erdj3b p58ipk double mutant female gametophytes, the sperm nucleus fused with one of the unfused polar nuclei. The unfused polar nuclei fused during the first endosperm nuclear division by nuclear envelope breakdown [

44]. Normal seed development was also reported after the fertilization of

fiona mutant female gametophytes containing unfused polar nuclei with wild-type pollen [

52]. Normal endosperm development was observed in rice, wheat, and maize, producing female gametophytes with unfused polar nuclei [

53,

54,

55]. The fusion of polar nuclei can be omitted in the formation of triploid endosperm.

Sperm nuclear fusion at fertilization seems to be essential for embryo development. Sperm nuclear fusion was defective in the egg cell after fertilization of

gex1 female gametophytes with

gex1 pollen [

23]. Aberrant embryo development was observed in the resulting

gex1 mutant seeds [

23,

48]. Analyses of the

gex1 mutant seeds suggested that the first asymmetric cell division occurred after fertilization. However, embryo development is delayed and arrested between the two- and eight-celled embryo stages [

23]. This is in good contrast to that embryo development proceeded to the globular to the heart stages after fertilization of

erdj3a p58ipk double mutant female gametophytes with wild-type pollen, in which sperm nuclear fusion occurred in the egg cell [

43].

5. Concluding Remarks

Eukaryotes evolved unique mechanisms to promote nuclear fusion efficiently during sexual reproduction. GEX1/Kar5 family proteins are nuclear membrane proteins expressed in the reproduction phase that are conserved between plants, animals and fungi. Proteins of this family are key factors for nuclear membrane fusion since their deficiency resulted in nuclear fusion defects. Acquisition of this protein family could be one of the critical steps for establishing sexual reproduction in eukaryotes. GEX1/Kar5 family proteins most likely function in nuclear membrane fusion with other proteins. Analyses using yeast and A. thaliana revealed the involvement of ubiquitously expressed proteins such as BiP, ER-resident J proteins and SUN proteins in nuclear fusion. The involvement of these proteins in the nuclear fusion of other organisms is yet to be analyzed. The other proteins may function in nuclear membrane fusion with these identified proteins. Future studies will reveal mechanisms of nuclear membrane fusion at the molecular level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K. and S.N.; data curation, N.K. and S.N.; writing the original draft, revision and edits, N.K. and S.N..; funding acquisition, S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (grant number 23K05814 to S.N.).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daisuke Maruyama for critically reading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Longo, F.J. Fertilization: A Comparative Ultrastructural Review. Biol. Reprod. 1973, 9, 149–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.D. Nuclear Fusion in the Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996, 12, 663–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, W.A. OBSERVATIONS ON THE FUSION OF NUCLEI IN PLANTS. J. Cell Biol. 1964, 23, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herskowitz, I. Life Cycle of the Budding Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 1988, 52, 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, L.J.; Beh, C.T.; Latterich, M.; Schekman, R.; Rose, M.D. Nuclear Congression and Membrane Fusion: Two Distinct Events in the Yeast Karyogamy Pathway. J. Cell Biol. 1994, 126, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.; Endo, T. The Yeast JEM1p Is a DnaJ-like Protein of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane Required for Nuclear Fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 12889–12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizzio, V.; Khalfan, W.; Huddler, D.; Beh, C.T.; Andersen, S.S.; Latterich, M.; Rose, M.D. Genetic Interactions between KAR7/SEC71, KAR8/JEM1, KAR5, and KAR2 during Nuclear Fusion in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloy, P.; Shen, S.; White, E.; McIntosh, J.R.; Rose, M.D. Nuclear Fusion during Yeast Mating Occurs by a Three-Step Pathway. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 179, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibeaux, R.; Knop, M. When Yeast Cells Meet, Karyogamy!: An Example of Nuclear Migration Slowly Resolved. Nucleus 2013, 4, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspersen, S.L.; Giddings, T.H., Jr; Winey, M. Mps3p Is a Novel Component of the Yeast Spindle Pole Body That Interacts with the Yeast Centrin Homologue Cdc31p. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 159, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.-I.; Terazawa, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Hirata, A.; Makio, T.; Endo, T. Nep98p Is a Component of the Yeast Spindle Pole Body and Essential for Nuclear Division and Fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 9938–9943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspersen, S.L.; Martin, A.E.; Glazko, G.; Giddings, T.H., Jr; Morgan, G.; Mushegian, A.; Winey, M. The Sad1-UNC-84 Homology Domain in Mps3 Interacts with Mps2 to Connect the Spindle Pole Body with the Nuclear Envelope. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E.; Kusch, J.; Barral, Y.; Huffaker, T.C. Spindle Orientation in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Depends on the Transport of Microtubule Ends along Polarized Actin Cables. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 161, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manatschal, C.; Farcas, A.-M.; Degen, M.S.; Bayer, M.; Kumar, A.; Landgraf, C.; Volkmer, R.; Barral, Y.; Steinmetz, M.O. Molecular Basis of Kar9-Bim1 Complex Function during Mating and Spindle Positioning. Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 3729–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.D.; Misra, L.M.; Vogel, J.P. KAR2, a Karyogamy Gene, Is the Yeast Homolog of the Mammalian BiP/GRP78 Gene. Cell 1989, 57, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.; Walter, P. ER Membrane Protein Complex Required for Nuclear Fusion. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 132, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, J.L.; Schekman, R. A Sec63p-BiP Complex from Yeast Is Required for Protein Translocation in a Reconstituted Proteoliposome. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 123, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.-I.; Hirata, A.; Endo, T. Nuclear Inner Membrane Fusion Facilitated by Yeast Jem1p Is Required for Spindle Pole Body Fusion but Not for the First Mitotic Nuclear Division during Yeast Mating. Genes Cells 2008, 13, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beh, C.T.; Brizzio, V.; Rose, M.D. KAR5 Encodes a Novel Pheromone-Inducible Protein Required for Homotypic Nuclear Fusion. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 139, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, E.W.; Zhang, H.; Marlow, F.L.; Kapp, L.; Lu, S.; Mullins, M.C. Dynamic Assembly of Brambleberry Mediates Nuclear Envelope Fusion during Early Development. Cell 2012, 150, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.L.; Holmes-Davis, R.; McCormick, S. Green Sperm. Identification of Male Gamete Promoters in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 2124–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, J.; Otto, T.D.; Pfander, C.; Schwach, F.; Brochet, M.; Bushell, E.; Goulding, D.; Sanders, M.; Lefebvre, P.A.; Pei, J.; et al. Comparative Genomics in Chlamydomonas and Plasmodium Identifies an Ancient Nuclear Envelope Protein Family Essential for Sexual Reproduction in Protists, Fungi, Plants, and Vertebrates. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1198–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, S.-I.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Suzuki, C.; Yabe, A.; Sato, Y.; Kurihara, D.; Sato, Y.; Susaki, D.; Higashiyama, T.; Maruyama, D. Arabidopsis GEX1 Is a Nuclear Membrane Protein of Gametes Required for Nuclear Fusion During Reproduction. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 548032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.V.; Rose, M.D. Kar5p Is Required for Multiple Functions in Both Inner and Outer Nuclear Envelope Fusion in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. G3 2014, 5, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drews, G.N.; Koltunow, A.M.G. The Female Gametophyte. Arabidopsis Book 2011, 9, e0155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegari, R.; Drews, G.N. Female Gametophyte Development. Plant Cell 2004, 16 Suppl, S133–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, T.; Sprunck, S.; Wessel, G.M. Fertilization Mechanisms in Flowering Plants. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R125–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, F.; Hamamura, Y.; Ingouff, M.; Higashiyama, T. Double Fertilization – Caught in the Act. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, T.; Berger, F. The Central Cell Nuclear Position at the Micropylar End Is Maintained by the Balance of F-Actin Dynamics, but Dispensable for Karyogamy in Arabidopsis. Plant Reprod. 2015, 28, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Pan, L.; Xie, F.; Dai, B.; Sun, M.; Peng, X. Plant Egg Cell Fate Determination Depends on Its Exact Position in Female Gametophyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, T.; Maruyama, D.; Shagirov, M.; Li, J.; Hamamura, Y.; Yelagandula, R.; Toyama, Y.; Berger, F. Dynamic F-Actin Movement Is Essential for Fertilization in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Elife 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi, Y.; Okamoto, T. Nuclear Migration during Karyogamy in Rice Zygotes Is Mediated by Continuous Convergence of Actin Meshwork toward the Egg Nucleus. J. Plant Res. 2017, 130, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, Y.; Hoshino, R.; Okamoto, T. Dynamics of Male and Female Chromatin during Karyogamy in Rice Zygotes. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatema, U.; Ali, M.F.; Hu, Z.; Clark, A.J.; Kawashima, T. Gamete Nuclear Migration in Animals and Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, D.; Ohtsu, M.; Higashiyama, T. Cell Fusion and Nuclear Fusion in Plants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 60, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzotti, C.; Mendes, M.A.; Caporali, E.; Schnittger, A.; Kater, M.M.; Battaglia, R.; Colombo, L. The MADS Box Genes SEEDSTICK and ARABIDOPSIS Bsister Play a Maternal Role in Fertilization and Seed Development. Plant J. 2012, 70, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemer, M.; Wolters-Arts, M.; Grossniklaus, U.; Angenent, G.C. The MADS Domain Protein DIANA Acts Together with AGAMOUS-LIKE80 to Specify the Central Cell in Arabidopsis Ovules. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2088–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.-J.; Kwon, C.S.; Oh, D.-H.; Moon, J.S.; Chung, W.-I. Expression of an Evolutionarily Distinct Novel BiP Gene during the Unfolded Protein Response in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Gene 2003, 311, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, D.; Endo, T.; Nishikawa, S.-I. BiP-Mediated Polar Nuclei Fusion Is Essential for the Regulation of Endosperm Nuclei Proliferation in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 1684–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, D.; Endo, T.; Nishikawa, S.-I. BiP3 Supports the Early Stages of Female Gametogenesis in the Absence of BiP1 and BiP2 in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e1035853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, D.; Sugiyama, T.; Endo, T.; Nishikawa, S.-I. Multiple BiP Genes of Arabidopsis Thaliana Are Required for Male Gametogenesis and Pollen Competitiveness. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Maruyama, D.; Endo, T.; Nishikawa, S.-I. Arabidopsis Thaliana Has a Set of J Proteins in the Endoplasmic Reticulum That Are Conserved from Yeast to Animals and Plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, D.; Yamamoto, M.; Endo, T.; Nishikawa, S.-I. Different Sets of ER-Resident J-Proteins Regulate Distinct Polar Nuclear-Membrane Fusion Events in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, D.; Higashiyama, T.; Endo, T.; Nishikawa, S.-I. Fertilization-Coupled Sperm Nuclear Fusion Is Required for Normal Endosperm Nuclear Proliferation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.; Wada, S.; Takahashi, A.; Urawa, H.; Kamei, Y.; Nishikawa, S.-I. Development of a Heat-Inducible Gene Expression System Using Female Gametophytes of Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 2564–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Graumann, K.; Meier, I. The Plant Nuclear Envelope as a Multifunctional Platform LINCed by SUN and KASH. Journal of Experimental Botany 2015, 66, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Groves, N.R.; Meier, I. SUN Anchors Pollen WIP–WIT Complexes at the Vegetative Nuclear Envelope and Is Necessary for Pollen Tube Targeting and Fertility. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 7299–7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alandete-Saez, M.; Ron, M.; Leiboff, S.; McCormick, S. Arabidopsis Thaliana GEX1 Has Dual Functions in Gametophyte Development and Early Embryogenesis. Plant J. 2011, 68, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, A.; Nishikawa, S.-I. Expression of GEX1 Orthologs of Brassica Rapa and Oryza Sativa Rescued the Nuclear Fusion Defect of the Arabidopsis GEX1 Mutant. Plants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, D.; Hong-yuan, Y. An Ultrastructural Study of Embryo Sac in Oryza Sativa L. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 1989, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Van Went, J.; Cresti, M. Pre-Fertilization Degeneration of Both Synergids in Brassica Campestris Ovules. Sex. Plant Reprod. 1988, 1, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kägi, C.; Baumann, N.; Nielsen, N.; Stierhof, Y.-D.; Gross-Hardt, R. The Gametic Central Cell of Arabidopsis Determines the Lifespan of Adjacent Accessory Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 22350–22355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, R.; Jensen, W.A. Ultrastructural Observations of the Mature Megagametophyte and the Fertilization in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum). Can. J. Bot. 1985, 63, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.J.; Rost, T.L. The Developmental Anatomy and Ultrastructure of Somatic Embryos from Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Scutellum Epithelial Cells. Bot. Gaz. 1989, 150, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, R.; Matthys-Rochon, E.; Dumas, C. The Kinetics of Cytological Events during Double Fertilization in Zea Mays L. Plant J. 1994, 5, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).